Open Innovation for Green Transition in Energy Sector: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- R1. How can open innovation be used in the economy and by individual entities to achieve the goals of the green transition (increasing the use of renewable resources, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, modernizing conventional energy)?

- R2. How can specific stakeholder groups (including individual investors, institutional investors, corporations, and civic organizations) be motivated to participate in open innovation processes supporting green transition? And what financial instruments and mechanisms can support open innovation in the energy transition?

- R3. What are the real effects of using open innovation on a macroeconomic, social, and individual scale?

- gathering existing knowledge and experience on the methodology of using open innovation in the green transition;

- holistic identification of ways to activate and motivate stakeholders to engage in the creation of open innovation in the energy sector;

- development of a comprehensive list of benefits of using open innovation in the green transition to promote this form of innovation.

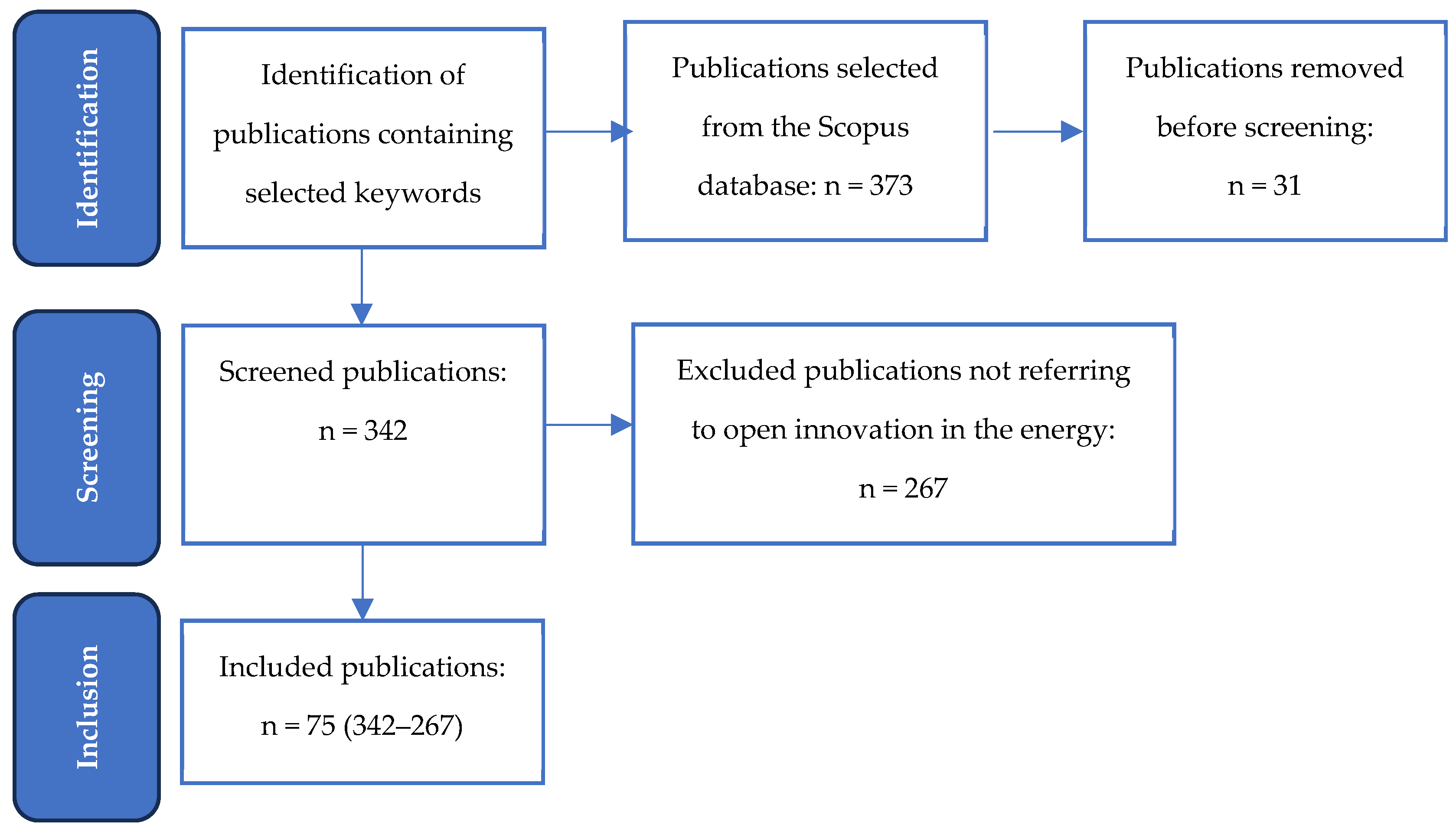

2. Materials and Methods

- those concerning sectors other than energy,

- those not directly related to the main line of reasoning, in which open innovation was only a side issue.

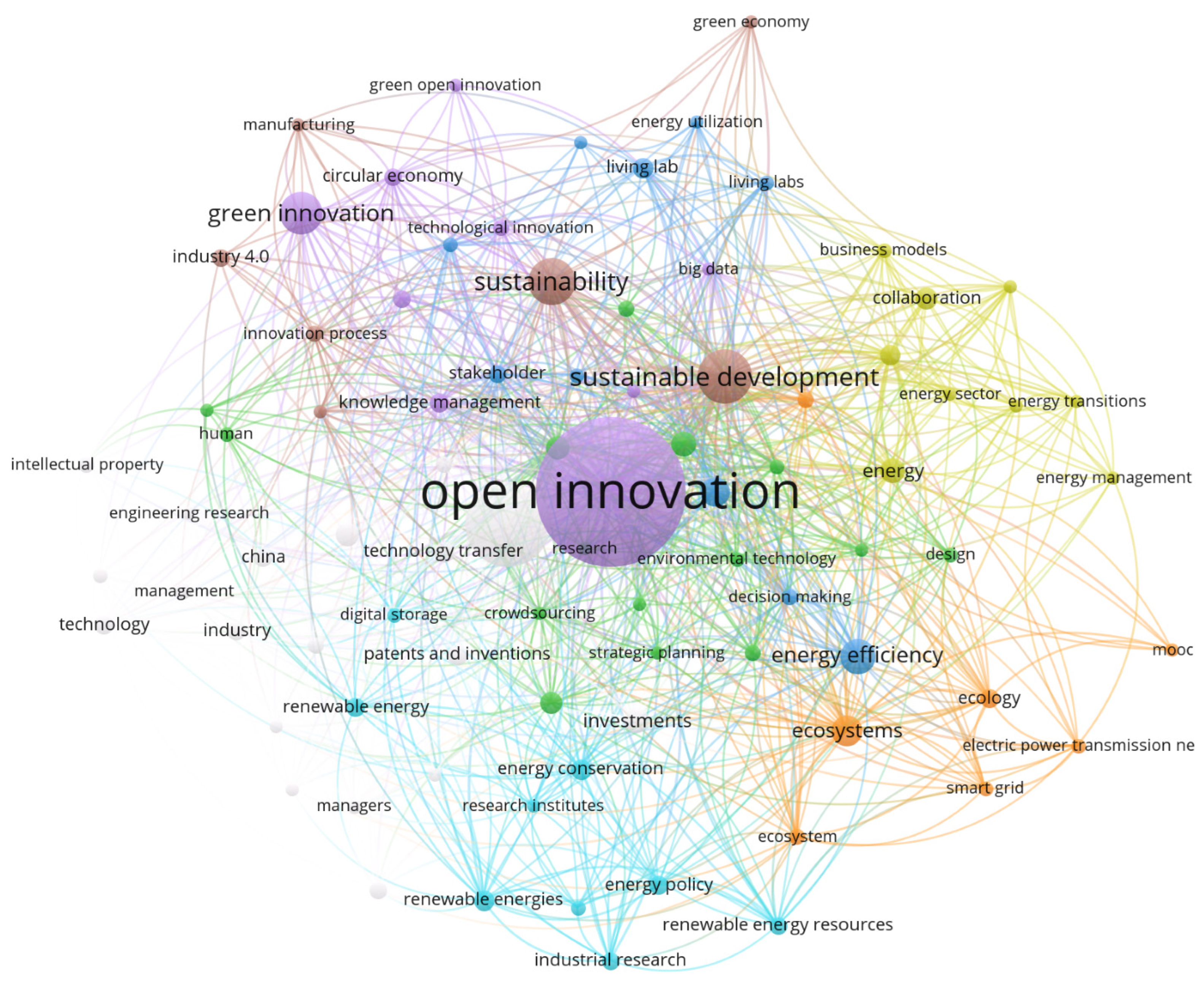

- keyword links aimed at detailing research topics in the field of open green innovation in energy;

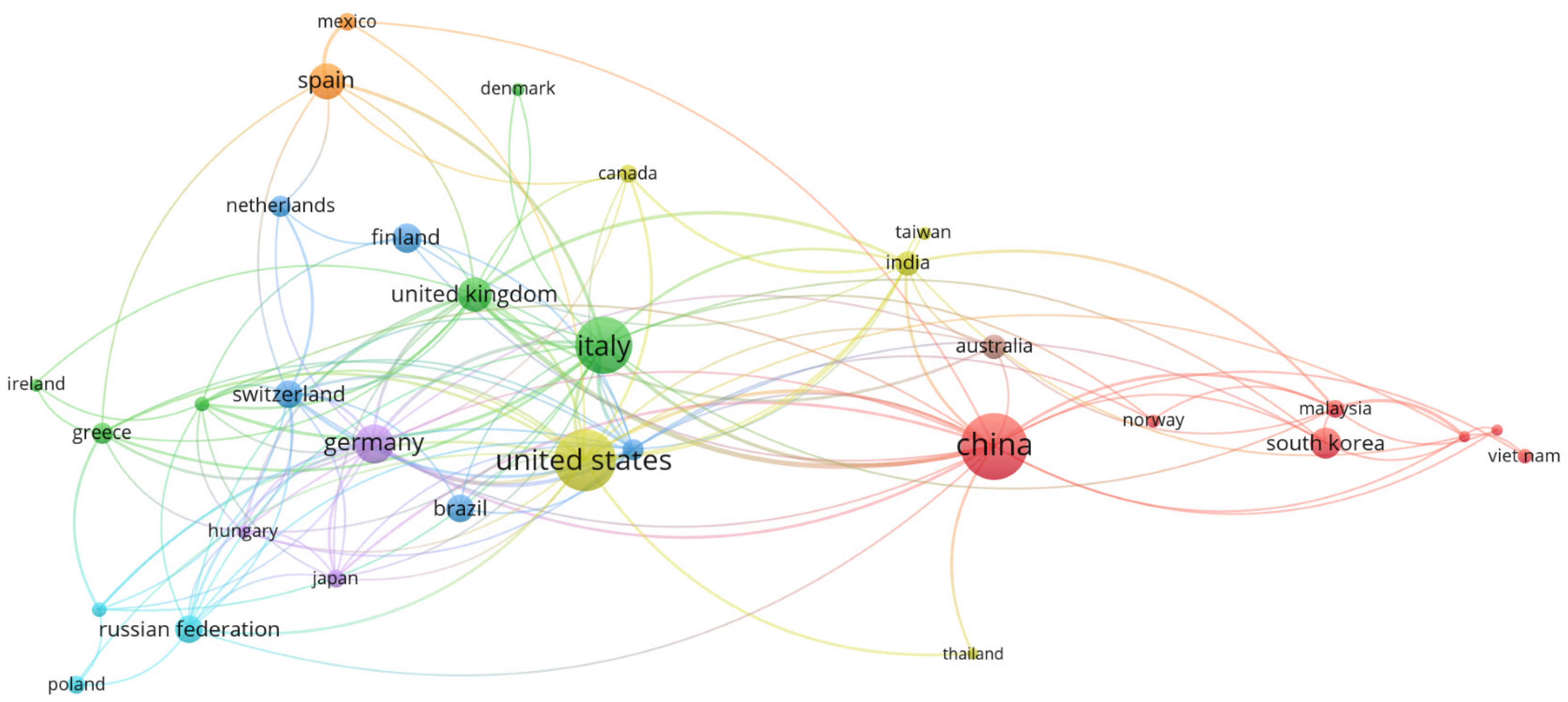

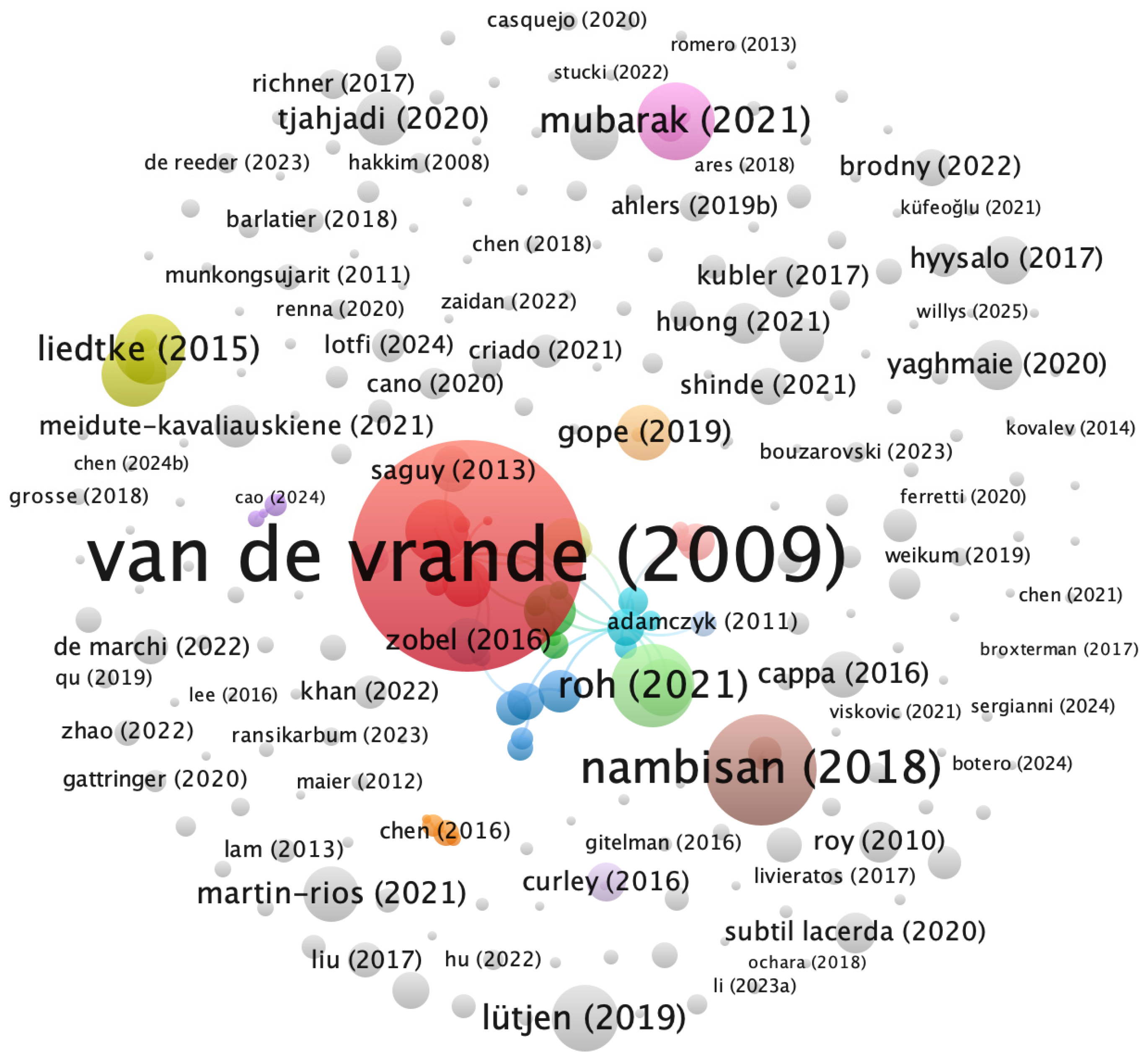

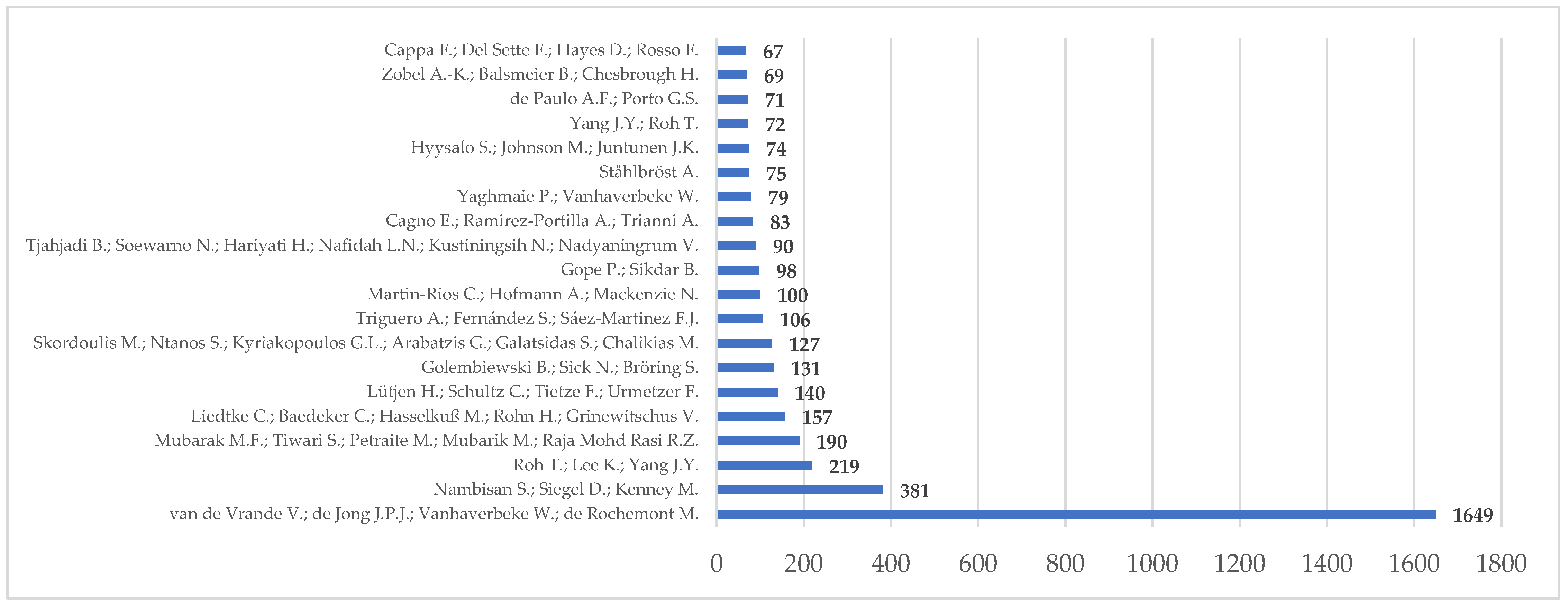

- number of citations, allowing the identification of topics that are most popular among scientists and researchers;

- country of origin of the publication, allowing the identification of geographical regions where research on open innovation is particularly intensive.

- the circumstances of the use of open innovation in the green transition;

- tools and methods encouraging stakeholders to cooperate for the green transition;

- the effects of using open innovation in the green transition.

3. Results

3.1. Bibliometric Analysis

- open innovation in SMEs: trends, motives, and management challenges [39],

- the impact of Industry 4.0 technologies and open innovation on the effectiveness of green transition [40],

- the role of government support and assistance in the use of intellectual property rights in the development of green open innovation [41].

3.2. The Use of Open Innovation in the Energy Transition from a Macro, Meso, and Microeconomic Research Perspective

- for enterprises: case studies of individual programs for the implementation of open innovation [55,56] and stimulants for open innovation [57]; econometric analyses of the determinants of innovation for groups of energy companies [58]; identification of the role of social enterprises in creating open innovation in the field of renewable energy [59] (Willys et al., 2025); assessment of open innovation in the small- and medium-sized enterprise sector [60,61];

- for prosumers: identification of the role of prosumers in the development of open innovation in the solar energy sector [62].

3.3. Methods of Motivating Stakeholders to Engage in Open Innovation for Green Transition

- internal resources and competencies related to the individual characteristics of particular stakeholders;

- distinguishing features of partnerships relating to the nature of relationships and cooperation networks;

- external legal and regulatory conditions shaped at the government and local government levels;

- external technical and organizational solutions supporting the creation of open innovation.

3.4. The Effects of Using Open Innovation in the Green Transition

4. Discussion

- internal resources and competencies (knowledge management, internal programs, open leadership, trust, complementarity of resources);

- partnership differentiators (modern business models, involvement of partnership intermediaries, strengthening relationships with suppliers and customers, involvement of prosumers, cooperation with universities and research institutions);

- external legal and regulatory conditions (intellectual property rights protection, pro-innovation and pro-environmental education systems; creation of a legal framework for cooperation between science and business);

- external technical and organizational solutions (online platforms, social media, Living Labs, external sources of knowledge).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kulkarni, S.S.; Wang, L.; Venetsanos, D. Managing technology transfer challenges in the renewable energy sector within the European union. Wind 2022, 2, 150–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laimon, M.; Yusaf, T.; Mai, T.; Goh, S.; Alrefae, W. A systems thinking approach to address sustainability challenges to the energy sector. Int. J. Thermofluids 2022, 15, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, T.E.T.; Soares, S.R. Systematic literature review on the application of life cycle sustainability assessment in the energy sector. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 1583–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigauri, I.; Vasilev, V. Corporate social responsibility in the energy sector: Towards sustainability. In Energy Transition: Economic 1615, Social and Environmental Dimensions; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Stecuła, K.; Wolniak, R.; Grebski, W.W. AI-Driven urban energy solutions—From individuals to society: A review. Energies 2023, 16, 7988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, A.; Nawrocki, T.L. Comparative analysis of the cost of equity of hard coal mining enterprises–an international perspective. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. Miner. Resour. Manag. 2015, 31, 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Trzaska, R.; Sulich, A.; Organa, M.; Niemczyk, J.; Jasiński, B. Digitalization business strategies in energy sector: Solving problems with uncertainty under industry 4.0 conditions. Energies 2021, 14, 7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xia, S.; Huang, P.; Qian, J. Energy transition: Connotations, mechanisms and effects. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 52, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamnatou, C.; Cristofari, C.; Chemisana, D. Renewable energy sources as a catalyst for energy transition: Technological innovations and an example of the energy transition in France. Renew. Energy 2024, 221, 119600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żywiołek, J.; Wolniak, R.; Grebski, W.W.; Tiwari, S.; Matuszewski, M.; Koliński, A. Unlocking renewable energy potential: Overcoming knowledge sharing hurdles in rural EU regions on example of poland, sweden and france. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdzik, B.; Wolniak, R.; Nagaj, R.; Grebski, W.W.; Romanyshyn, T. Barriers to renewable energy source (RES) installations as determinants of energy consumption in EU countries. Energies 2023, 16, 7364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcerzak, A.P.; Uddin, G.S.; Dutta, A.; Pietrzak, M.B.; Igliński, B. Energy mix management: A new look at the utilization of renewable sources from the perspective of the global energy transition. Equilibrium. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2024, 19, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcerzak, A.P.; Uddin, G.S.; Igliński, B.; Pietrzak, M.B. Global energy transition: From the main determinants to economic challenges. Equilibrium. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2023, 18, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Feng, G.F.; Chang, C.P. Is green finance capable of promoting renewable energy technology? Empirical investigation for 64 economies worldwide. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 483–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heal, G. Economic aspects of the energy transition. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2022, 83, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierpińska, M. Determinants of mining companies’ capital structure. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. Miner. Resour. Manag. 2021, 37, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, P. Characteristics of the capital gaining sources and financing the activity of coal mine enterprises. Part 2: Sources of the foreign capital. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. Miner. Resour. Manag. 2007, 23, 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Oryani, B.; Koo, Y.; Rezania, S.; Shafiee, A. Barriers to renewable energy technologies penetration: Perspective in Iran. Renew. Energy 2021, 174, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathoni, H.S.; Setyowati, A.B.; Prest, J. Is community renewable energy always just? Examining energy injustices and inequalities in rural Indonesia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdonek, I.; Tokarski, S.; Mularczyk, A.; Turek, M. Evaluation of the program subsidizing prosumer photovoltaic sources in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Grift, E.; Cuppen, E. Beyond the public in controversies: A systematic review on social opposition and renewable energy actors. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91, 102749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L.; Chun, J.; Gant, A.; Hodgkins, C.; Cohen, J.; Lohmar, S. Sources of opposition to renewable energy projects in the United States. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonek-Kowalska, I. Motives for the Use of Photovoltaic Installations in Poland against the Background of the Share of Solar Energy in the Structure of Energy Resources in the Developing Economies of Central and Eastern Europe. Resources 2023, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonek-Kowalska, I.; Grebski, W. Autarky and the Promotion of Photovoltaics for Sustainable Energy Development: Prosumer Attitudes and Choices. Energies 2024, 17, 3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Ore Areche, F.; Saenz Arenas, E.R.; Cosio Borda, R.F.; Javier-Vidalón, J.L.; Silvera-Arcos, S.; Ober, J.; Kochmańska, A. Natural disasters and energy innovation: Unveiling the linkage from an environmental sustainability perspective. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1256219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, S. Green growth and energy transition: An assessment of selected emerging economies. In Energy-Growth Nexus in an Era of Globalization; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 323–352. [Google Scholar]

- Nihal, A.; Areche, F.O.; Ober, J. Synergistic evaluation of energy security and environmental sustainability in BRICS geo-political entities: An integrated index framework. Equilibrium. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2024, 19, 793–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onifade, S.T.; Alola, A.A. Energy transition and environmental quality prospects in leading emerging economies: The role of environmental--related technological innovation. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 1766–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdoush, M.R.; Al Aziz, R.; Karmaker, C.L.; Debnath, B.; Limon, M.H.; Bari, A.M. Unraveling the challenges of waste-to-energy transition in emerging economies: Implications for sustainability. Innov. Green Dev. 2024, 3, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.T.; Wen, J.; Chang, C.P. Going green with artificial intelligence: The path of technological change towards the renewable energy transition. Oeconomia Copernic. 2023, 14, 1059–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Adebayo, T.S.; Irfan, M.; Abbas, S. Environmental quality and energy transition prospects for G-7 economies: The prominence of environment-related ICT innovations, financial and human development. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hainsch, K.; Löffler, K.; Burandt, T.; Auer, H.; Del Granado, P.C.; Pisciella, P.; Zwickl-Bernhard, S. Energy transition scenarios: What policies, societal attitudes, and technology developments will realize the EU Green Deal? Energy 2022, 239, 122067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Hess, D.J.; Cantoni, R. Energy transitions from the cradle to the grave: A meta-theoretical framework integrating responsible innovation, social practices, and energy justice. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 75, 102027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Ahn, H.J.; Lee, D.S.; Park, K.B.; Zhao, X. Inter-rationality; Modeling of bounded rationality in open innovation dynamics. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 184, 122015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Jeong, E.; Kim, S.; Ahn, H.; Kim, K.; Hahm, S.D.; Park, K. Collective intelligence: The creative way from knowledge to open innovation. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2021, 26, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Zhao, X.; Del Gaudio, G.; Della Corte, V.; Sadoi, Y. Leveraging business model innovation through the dynamics of open innovation: A multi-country investigation in the restaurant industry. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2025, 28, 1342–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Yun, J.J.; Díaz, M.M.; Duque, C.M. Open innovation through customer satisfaction: A logit model to explain customer recommendations in the hotel sector. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Van de Vrande, V.; De Jong, J.P.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; De Rochemont, M. Open innovation in SMEs: Trends, motives and management challenges. Technovation 2009, 29, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, M.F.; Tiwari, S.; Petraite, M.; Mubarik, M.; Raja Mohd Rasi, R.Z. How Industry 4.0 technologies and open innovation can improve green innovation performance? Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 1007–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Lee, K.; Yang, J.Y. How do intellectual property rights and government support drive a firm’s green innovation? The mediating role of open innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, V.N. Relationship between GDP, FDI, renewable energy, and open innovation in Germany: New insights from ARDL method. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 25, 100592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska-Styczeń, A.; Bublyk, M.; Lytvyn, V. Green innovative economy remodeling based on economic complexity. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobov, D.; Rybin, M. Openness to external innovation in major oil and gas companies. Reg. Sect. Econ. Stud. 2021, 21, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- De Paulo, A.F.; Porto, G.S. Solar energy technologies and open innovation: A study based on bibliometric and social network analysis. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanela, C.; da Silva Albino, J.; Silva Dos Santos, M.I.A. Open innovation and protection of intellectual property rights in Brazilians wind farms. In Proceedings of the 26th International Association for Management of Technology Conference 2020, IAMOT 2017, Vienna, Austria, 14–18 May 2017; pp. 1766–1780. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakopoulos, G.L. The Role of Open Innovation in Governmental Sustainability. In Proceedings of the Euro-Asian Symposium on Economic Theory, EASET 2022, Ekaterinburg, Russia, 29–30 June 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall-Orsoletta, A.; Romero, F.; Ferreira, P. Open and collaborative innovation for the energy transition: An exploratory study. Technol. Soc. 2022, 69, 101995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, A.; Palacios, M.; Grijalvo, M. Open organizational structures: A new framework for the energy industry. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5175–5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajo, R.; Cabeza, L.F. Renewable energy research and technologies through responsible research and innovation looking glass: Reflexions, theoretical approaches and contemporary discourses. Appl. Energy 2018, 211, 792–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiyavuth, R. How open innovation models might help the Thai energy sector to address the climate change challenge? A conceptual framework on an approach to measure the impact of adoption of open innovation. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing, KMIS 2012, Barcelona, Spain, 4–7 October 2012; pp. 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Chiaroni, D.; Chiesa, V.; Frattini, F.; Terruzzi, R. Implementing open innovation: A case study in the renewable energy industry. Int. J. Technol. Intell. Plan. 2015, 10, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golov, R.; Smirnov, V.; Narezhnaya, T.; Ovsyannikova, A.; Zhutaeva, E.; Sizova, E.; Makeeva, T. Adaptation of industrial and energy enterprises to the implementation of the concept of open innovation. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Science Conference on Business Technologies for Sustainable Urban Development, SPbWOSCE 2018, St. Petersburg, Russia, 10–12 December 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banet, C. Chapter 10 The treatment of intellectual property rights in open innovation models: New business models for the energy transition. In Intellectual Property and Sustainable Markets; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R.; Marquini, R.; Fernandez, M.; Grabowsky, P.; Lemos, R.; Pinto, G.; Jorge, C.T.A., Jr.; Cruz, I. Applying the Scale Up and Stakeholder Methodologies to Design an Innovation Hub for the O&G and Energy Ecosystem in Brazil. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Association for the Management of Technology Conference, IAMOT 2024, Porto, Portugal, 8–11 July 2024; pp. 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippolis, S.; Ruggieri, A.; Leopizzi, R. Open Innovation for sustainable transition: The case of Enel “Open Power”. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 4202–4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S.; Crowley, F.; Doran, J.; O’Connor, M. Exploratory and exploitative linkages and innovative activity in the offshore renewable energy sector. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2024, 30, 140–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Roh, T.; Boroumand, R.H. Resource recombination perspective on open eco-innovation: Open innovation type, strategic orientation, and green innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 6207–6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willys, N.; Li, W.; Larbi-Siaw, O.; Brou, E.F. Mapping the social value creation of renewable energy enterprises in a social open innovation milieu. Kybernetes 2025, 54, 2494–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xie, X.; Zhou, M.; Yan, L. How to drive green innovation of manufacturing SMEs under open innovation networks—The role of innovation platforms’ relational governance. Manag. Decis. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumanti, A.A.; Rizaldi, A.S.; Amelia, M. Green Innovation toward Knowledge Sharing and Open Innovation in Indonesian SMIs. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management 2024, IEEM 2024, Bangkok, Thailand, 15–18 December 2024; pp. 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusio, T.; Zlatanovic, D.; Rosiek, J.; Radin, M. Prosumerism: Transforming External Stakeholders into Internal Ones in the Innovation Process. In The Palgrave Handbook of Consumerism Issues in the Apparel Industry; Kaufmann, H.R., Panni, M.F.A.K., Vrontis, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulnaga, M.; Sala, M.; Trombadore, A. Open Innovation Strategies, Green Policies, and Action Plans for Sustainable Cities—Challenges, Opportunities, and Approaches. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions, SSPCR 2019, Bolzano, Italy, 9–13 December 2019; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel, A.-K.; Balsmeier, B.; Chesbrough, H. Does patenting help or hinder open innovation? Evidence from new entrants in the solar industry. Ind. Corp. Change 2016, 25, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marostica, S.; Suzuki, R.; De Bem Machado, A.; Dandolini, G.A.; De Souza, J.A. Blockchain x Green Open Innovation Evidence and Trends for Sustainability. In Blockchain as a Technology for Environmental Sustainability; José Sousa, M., Chekole Workneh, T., Holtskog, H., Eds.; CRS Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi, O.; Alam, M.N.; Hago, I.E.; Azizan, N.A.; Hashim, F.; Hossain, M.S. Green innovation behaviour: Impact of industry 4.0 and open innovation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordoulis, M.; Ntanos, S.; Kyriakopoulos, G.L.; Arabatzis, G.; Galatsidas, S.; Chalikias, M. Environmental innovation, open innovation dynamics and competitive advantage of medium and large-sized firms. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattinson, S.; Damij, N.; El Maalouf, N.; Bazi, S.; Elsahn, Z.; Hilliard, R.; Cunningham, J.A. Building green innovation networks for people, planet, and profit: A multi-level, multi-value approach. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 115, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Chin, T.; Huang, J.; Perano, M.; Temperini, V. Knowledge-driven networking and ambidextrous innovation equilibrium in power systems transition. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 1414–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, V.; Molina-Morales, F.X.; Martínez-Cháfer, L. Environmental innovation and cooperation: A configurational approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 182, 121835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskanius, P.; Pohjola, I. Leveraging communities of practice in university-industry collaboration: A case study on Arctic research. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2016, 10, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, S. Patent Protection Policy and Firms’ Green Technology Innovation: Mediating Roles of Open Innovation and Human Capital. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnert, A.-K.; Arlinghaus, J. Open source as an enabler for circularity: A systematic literature review. Procedia CIRP 2023, 120, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, P.; Secundo, G.; Garzoni, A. Digital Open Innovation for Sustainability: Evidence from Italian Big Energy Corporations. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 8430–8443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabagar, M.; Kuah, Y.; Uzaini, M.M. Accelerating Decarbonisation through Enterprise Level Orchestration. In Proceedings of the 2023 Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference 2023, ADIP 2023, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2–5 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakarelou, I.; Kotsifakos, D.; Douligeris, C. Leveraging Students Engagement through the Incorporation of Serious Games. In Proceedings of the 15th IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON 2024, Kos Island, Greece, 8–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niankara, I. Youths interests in the biosphere and sensitivity to nuclear power technology in the UAE: With discussions on open innovation and technological convergence in energy and water sectors. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, D.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y. How to Evaluate College Students’ Green Innovation Ability—A Method Combining BWM and Modified Fuzzy TOPSIS. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergianni, L.; De Chiara, A.; Mauro, S. Open Innovation as Fuel for the Circular Economy: An Analysis of the Italian Context. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 12, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toroslu, A.; Herrmann, A.M.; Chappin, M.M.H.; Schemmann, B.; Castaldi, C. Open innovation in nascent ventures: Does openness influence the speed of reaching critical milestones? Technovation 2023, 124, 102732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeeva, Y.; Kalinina, M.; Sargu, L.; Kulachinskaya, A.; Ilyashenko, S. Energy Sector Enterprises in Digitalization Program: Its Implication for Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanni, M.; Kim, Y.J. How open are African inventors? Open green technologies and patenting activities in Africa. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2024, 16, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Ansari, K.M. Open innovation ecosystems: Toward low-cost wind energy startups. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2020, 14, 853–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchella, A.; Sanguineti, F.; Contino, F. Collaborations between MNEs and entrepreneurial ventures. A study on Open Innovability in the energy sector. Int. Bus. Rev. 2024, 33, 102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, P.; Polasko, K.; Molina, A. Open innovation laboratory in electrical energy education based on the knowledge economy. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Educ. 2021, 58, 667–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, H.T.; Xie, X. Fostering green innovation performance through open innovation strategies: Do green subsidies work? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 18641–18671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, M.; Locatelli, G.; Lisi, S. Open innovation in the power & energy sector: Bringing together government policies, companies’ interests, and academic essence. Energy Policy 2017, 104, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subtil Lacerda, J.; van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. Effectiveness of an ‘open innovation’ approach in renewable energy: Empirical evidence from a survey on solar and wind power. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 118, 109505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattringer, R.; Wiener, M. Key factors in the start-up phase of collaborative foresight. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 153, 119931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csedő, Z.; Zavarkó, M.; Magyari, J. Implications of open eco-innovation for sustainable development: Evidence from the European renewable energy sector. Sustain. Futures 2023, 6, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabasta, A.; Petrovic, A.; Ktena, A.; Kunicina, N.; Arsic, N.; Ajanovic, A. Development of KALCEA Novel Collaborative Platform for Sustainable Development of Western Balkan Countries. In Learning in the Age of Digital and Green Transition; ICL 2022; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 913–920; Volume 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlatier, P.-J.; Josserand, E. Delivering open innovation promises through social media. J. Bus. Strategy 2018, 39, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, F.B.; Da Gama, K.S.; De Moura, H.P. Sponsor’s perspectives on open innovation projects: Results of a qualitative study. In Proceedings of the 16th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, CISTI 2021, Chaves, Portugal, 23–26 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudnik, O.; Vasiljeva, M.; Kuznetsov, N.; Podzorova, M.; Nikolaeva, I.; Vatutina, L.; Khomenko, E.; Ivleva, M. Trends, impacts, and prospects for implementing artificial intelligence technologies in the energy industry: The implication of open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Pourbabak, H.; Su, W. Electricity market reform. In The Energy Internet: An Open Energy Platform to Transform Legacy Power Systems into Open Innovation and Global Economic Engines; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Qing, L.; Ock, Y.-S.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Y. The Effect of Customer Involvement on Green Innovation and the Intermediary Role of Boundary Spanning Capability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Roh, T. Open for green innovation: From the perspective of green process and green consumer innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Barth, V. Open innovation in urban energy systems. Energy Effic. 2012, 5, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indradewa, R.; Tjakraatmadja, J.H.; Dhewanto, W. Open innovation between energy companies in developed and developing countries: Resource-based and knowledge-based perspectives. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2017, 12, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Jeppesen, J.; Bandsholm, J.; Asmussen, J.; Balachandran, R.; Vestergaard, S.; Andersen, T.H.; Sørensen, T.K.; Bjørn-Thygesen, F. Navigating the “paradox of openness” in energy and transport innovation: Insights from eight corporate clean technology research and development case studies. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, L.; Mastelic, J.; Nyffeler, N.; Latrille, S.; Seulliet, É. Living lab as a support to trust for co-creation of value: Application to the consumer energy market. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2019, 1, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huong, P.T.; Cherian, J.; Hien, N.T.; Sial, M.S.; Samad, S.; Tuan, B.A. Environmental management, green innovation, and social–open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotti, F.; Troise, C.; Ferraris, A.; Hirwani Wan Hussain, W. Bridging Innovation Management and Circular Economy: An Empirical Assessment of Green Innovation and Open Innovation. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2025, 34, 466–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P. Do specific platforms affect the relationship between digital technology application and green transformation? Evidence from different platforms in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 69, 106070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, Y.S. SMEs’ external technology R & D cooperation network diversity and their greenhouse gas emission reduction and energy saving: A moderated mediation analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakkim, R.P.; Heidrick, T.R. Open innovation in the energy sector. In Proceedings of the 2008 Portland International Center for Management of Engineering and Technology, Technology Management for a Sustainable Economy, PICMET ’08, Cape Town, South Africa, 27–31 July 2008; pp. 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, O. Global trends in collaborative infrastructure development to foster economically, environmentally & socially sustainable built environment in regional economies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Efficient Building Design: Material and HVAC Equipment Technologies, Beirut, Lebanon, 4–5 October 2018; pp. 11–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, M.-T. Green innovation dynamics: The mediating role of green intellectual capital and open innovation of SMEs in Vietnam. J. Int. Bus. Entrep. Dev. 2023, 15, 430–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisławski, K. Characteristics of Open Innovation among Polish SMEs in the Context of Sustainable Innovative Development Focused on the Rational Use of Resources. Energies 2022, 15, 6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, J.A.; Londoño-Pineda, A. Scientific literature analysis on sustainability with the implication of open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 6, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, S.; Vogel, C. Optimizing energy systems with open innovation. In Proceedings of the ETG-Kongress 2021: Von Komponenten bis zum Gesamtsystem fur die Energiewende—ETG Congress 2021: From Components to the Overall System for the Energy Turnaround, Virtual, 18–19 May 2021; pp. 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzarovski, S.; Damigos, D.; Kmetty, Z.; Simcock, N.; Robinson, C.; Jayyousi, M.; Crowther, A. Energy justice intermediaries: Living Labs in the low-carbon transformation. Local Environ. 2023, 28, 1534–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Zhao, X.; Jeong, E.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.; Hahm, S.D. The signal of post catch-up in open innovation dynamics. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2023, 28, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Zhao, X.; Ma, L.; Liu, Z.; Yang, B. Open innovation dynamics and evolution in the mobile payment industry–comparative analysis among Daegu, Cardiff, and Nanjing. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 862–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods of Motivating Stakeholders Based on: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Resources and Competencies | Distinguishing Features of Partnerships | External Legal and Regulatory Conditions | External Technical and Organizational Solutions |

| A mentoring program led by a leading company that stimulates partnerships between start-ups and corporations, research institutions, while respecting intellectual property rights [55]. | The beneficial impact of cooperation between energy companies and universities (not private consultants) [70] and the creation of so-called communities of practice with them [71]. | Regulation of intellectual property rights in line with the expectations of partners creating open innovations [72]. | Creation of online platforms to support open green innovation [60,73,74]. |

| An internal project focused on implementing a zero-emission economy within an energy company, promoting the concept of open innovation [75]. | Cooperation with suppliers and access to scientific journals foster research and development (R&D) and process innovation, while cooperation with customers fosters product innovation [57]. | Education focused on minimizing the energy footprint, green economy, and open innovation (e.g., using educational computer games or raising awareness of the biosphere and zero-emission energy technologies) [76,77,78]. | Creating Living Labs, i.e., public-private-civil partnerships for user-driven open innovation in the renewable energy sector [79]. |

| Creating a collaborative atmosphere, using relational management, and a positive perception of risk promote OI in the SME sector [60]. | Entering into external partnerships in research and development for OI may slow down product innovation, while joining industry organizations has a positive impact on OI in the renewable energy sector [80]. | Creating government incentive systems for the implementation of Industry 4.0 solutions in the energy sector and strengthening open innovation in this sector [40]. | Supporting digitization and access to open data systems in the energy sector [81]. |

| Open leadership based on extensive communication, cooperation, and power sharing [74]. | The openness of cooperation networks, their consolidation, and the inclusion of research institutions are desirable features of open innovation for decarbonization in Africa [82]. | Creation and use of international sources of financing for energy transition in developing countries (while maintaining protection for lenders, government control in the initial phase of development, and purchase guarantees for producers) [83]. | Promoting the benefits of open innovation, especially in the small- and medium-sized enterprise sector [84]. |

| A strategic approach to corporate social responsibility supported by open leadership fosters an organizational culture conducive to open innovation [56]. | The use of so-called external transformative stakeholders—prosumers—to engage in the process of creating innovations for the energy sector [62]. | The creation of a legal and regulatory framework for effective cooperation between the science sector, including universities and business [85]. | Use of external sources of knowledge with diverse but beneficial effects on open innovation (market sources, institutional sources, specialist sources) [86,87]. The usefulness of these sources in creating open innovation has been observed in wind and solar energy [88]. |

| Creating an open and inspiring learning environment and fostering enthusiasm for cross-sector exchange [89]. | Building relationships based on future complementarities between partners, increasing confidence in achieving desired economic outcomes [90]. | Building strategic partnerships with industry and research centers, creating knowledge and innovation centers, and developing open innovation platforms with virtual learning environments [91]. | |

| Diversification of partners’ resources and competencies—a factor more important than shared goals [89]. | Use of partnership intermediaries to integrate and manage [89]. | The use of social media to exchange knowledge and ideas while maintaining a lean organizational structure and integrating IO management into existing organizational structures [92]. | |

| Identifying the attitudes of innovation sponsors in the energy sector to facilitate cooperation: an organizational attitude focused on the relationship between the team and the sponsor; a task-oriented attitude focused on goals and results [93]. | The use of innovative business models in partnerships for AI-based OI [94]. | Effective energy demand management using the energy Internet [95]. | |

| Increasing customer engagement, including prosumers, in the open innovation process [72,96,97]. | Use of open innovation workshops and idea competitions to improve energy efficiency and grassroots proposals for change in the energy sector [98]. | ||

| Using various models of supporting OI: focusing on intangible factors such as knowledge management and using material resources [99]. | |||

| Using the dynamics of open innovation and gradually opening up previously closed innovations [100]. | |||

| Using trust as an element supporting value co-creation in OI [101]. | |||

| Prioritizing green efficiency by managers [97]. | |||

| Tangible | Intangible |

|---|---|

| Due to their use in environmental management, they can have a positive impact on a company’s financial results [102]. | Increase in the number of partnerships and improvement of the regulatory framework for research, development, and innovation [55]. |

| Enable the acquisition of the necessary resources to implement Clean Energy practices [103]. | A shift in strategic orientation towards a more open approach [58]. |

| Strengthen the link between the application of digital technologies and green innovation through the use of business technology innovation platforms and industry–university-research collaboration platforms [104]. | Increase the competitiveness and effectiveness of businesses in implementing AI technologies [94]. |

| Enable the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and trigger energy savings in small- and medium-sized enterprises [105]. | Support the technological development of enterprises [106], especially in exploratory links [57]. |

| Increase the efficiency of regions through international cooperation between cities [107]. | In combination with human capital, they can improve the intensity of green innovation creation [61,108]. |

| Support the transition of urban energy systems from the bottom up [98]. | Enable companies to engage in sustainable development more quickly and effectively [109,110]. |

| Optimize the use of energy networks and energy consumption [111]. | They are more useful in the development of climate change mitigation technologies than in climate change adaptation technologies [82]. |

| Reduce the costs of wind energy projects in energy-poor countries [83]. | Create social value and have a positive impact on entrepreneurial bricolage [59]. |

| Using Living Labs, they can reduce energy poverty in emerging economies [112]. | They can remove barriers to innovation such as lack of information, technological capabilities, and financial resources in circular economy-oriented enterprises [79]. |

| They act as key catalysts, strengthening the impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth [42]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jonek-Kowalska, I.; Rupacz, S.; Michalak, A. Open Innovation for Green Transition in Energy Sector: A Literature Review. Energies 2025, 18, 6451. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246451

Jonek-Kowalska I, Rupacz S, Michalak A. Open Innovation for Green Transition in Energy Sector: A Literature Review. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6451. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246451

Chicago/Turabian StyleJonek-Kowalska, Izabela, Sara Rupacz, and Aneta Michalak. 2025. "Open Innovation for Green Transition in Energy Sector: A Literature Review" Energies 18, no. 24: 6451. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246451

APA StyleJonek-Kowalska, I., Rupacz, S., & Michalak, A. (2025). Open Innovation for Green Transition in Energy Sector: A Literature Review. Energies, 18(24), 6451. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246451