Abstract

This paper presents a high-efficiency bidirectional multidevice interleaved SEPIC–ZETA DC–DC converter for electric mobility applications. The proposed converter offers key advantages, including reduced current and voltage ripple at both the input and output ports, achieved through a port ripple frequency six times higher than the switching frequency. Additionally, the required magnetic and capacitor volume is significantly reduced due to an inductor ripple frequency twice the switching frequency, leading to minimized power losses, reduced stress on power components, and enhanced efficiency. The use of a multidevice structure facilitates more efficient inductor volume optimization and provides improved fault redundancy. The converter is particularly suited for electric vehicle energy management systems, enabling efficient energy management among the various subsystems. It operates in open-loop mode, and this manuscript details the steady-state operating principle under continuous conduction mode. Design guidelines for parameter selection, comprehensive mathematical derivations, and a comparative analysis with existing DC-DC converters are presented. To validate the proposed topology, a 5 kW laboratory prototype was developed and tested across a wide range of load conditions. The experimental results confirm the converter’s high performance, achieving a peak efficiency of 98.6% at rated power.

1. Introduction

The increasing global demand for sustainable energy has positioned renewable energy generation as a viable solution to address energy shortages. A key area of ongoing research involves the integration of renewable sources with energy storage systems and the power grid, aiming to ensure reliability and efficiency. Power electronics, particularly in DC-DC conversion [1], play a pivotal role in this integration and are seeing widespread adoption across high-performance, high-power-density applications such as aircraft systems [2].

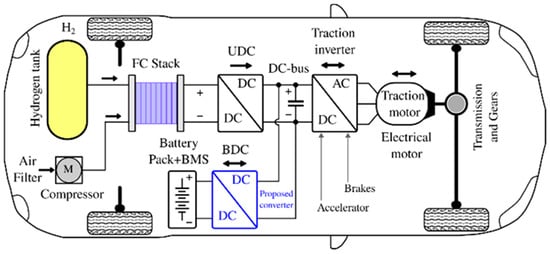

Electric vehicles (EVs), Hybrid Electric Vehicles (HEVs) and Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs) have been introduced as a sustainable alternative for transportation and as a means to reduce fossil fuel dependency. These technologies continue to evolve, demanding higher levels of technological maturity [3,4,5]. These systems require power converters capable of handling high power levels with high efficiency [6,7,8,9]. A modern EV propulsion system typically includes an electric machine, power converters, and an energy storage unit. Figure 1 illustrates a representative traction system architecture, in which a DC-DC converter manages the high-power charge and discharge cycles of the battery bank. The ability to support bidirectional power flow is a critical requirement for DC-DC converters in advanced automotive applications, enabling both regenerative braking and battery charging functionality.

Figure 1.

Simplified block diagram of the FCEV application.

DC-DC converters are becoming increasingly essential in EV systems. However, ensuring high-quality current draw from the battery remains a significant challenge across various operating modes, including traction, regenerative braking, and grid-connected charging modes. As discussed in the literature [10], isolated topologies based on the Dual Active Bridge (DAB) have attracted considerable attention. These converters allow for variation in the transformer turns ratio and support series-parallel configurations of the bridges, offering the flexibility required to achieve high voltage gain and efficient power transfer. Due to their galvanic isolation and scalability, isolated topologies have become the architecture of choice for advanced charging applications. However, this flexibility comes at the cost of added design complexity, particularly in the design and optimization of high-frequency magnetic components.

When galvanic isolation is not required, a common approach is to employ a large inductor on the battery-connected side to effectively reduce the ripple current. However, using a large inductor increases the converter’s size, weight and adversely affects its dynamic response. To address these drawbacks, several ripple cancellation techniques have been proposed in the literature [11], aiming to achieve zero ripple current at a specific duty cycle. One widely adopted method involves the use of interleaved converters, in which transistors operate with a defined phase shift [12]. In such topologies, while one inductor is charging, the interleaved counterpart is discharging, effectively canceling the ripple in the source current and yielding a nearly ripple-free waveform. Despite the effectiveness of this technique in ripple mitigation, the converter’s voltage gain presents certain limitations: (a) these include no achievable minimum gain threshold, (b) only a limited portion of the duty cycle range is usable, and (c) although the gain remains relatively constant across a broad duty cycle range, it exhibits a sharp increase near extreme duty cycles.

Several modified converter topologies based on the SEPIC architecture [13] have been proposed to enhance performance in applications such as EV chargers, renewable energy systems (e.g., photovoltaic and wind), LED lighting, power factor correction (PFC) rectifiers, and uninterruptible power supply (UPS) systems. These improvements typically involve one or two active switches and are characterized by reduced conduction losses, increased voltage gain, and higher overall efficiency. In [14], an interleaved SEPIC–Ćuk combination converter is analyzed, demonstrating the capability to generate dual balanced output voltages from a single DC input. The implementation employs four interleaved phases to effectively reduce input and output current ripple, enhance thermal management, and support higher power density. This interleaved architecture is particularly well-suited for applications involving the integration of low- and medium-power hybrid power supplies where space constraints are critical [15].

Interleaved converter topologies have gained significant attention for applications such as DC microgrids, particularly due to their capability to generate a bipolar DC bus while enhancing power quality and reducing losses, as demonstrated in [16]. The adoption of wide-bandgap (WBG) semiconductor devices, as discussed in [17], has further improved the efficiency, power density, and thermal performance of SEPIC converters. Moreover, high voltage gain is often required in these systems, as addressed in [18], where interleaving techniques are employed to reduce ripple current and minimize voltage and current stress on semiconductor devices. SEPIC-derived topologies, especially those featuring interleaving and tapped inductors, offer notable advantages in terms of efficiency, voltage gain, and scalability. However, magnetically coupled designs also introduce challenges, particularly related to leakage inductance, which increases voltage stress on switching devices. To mitigate this, dissipative snubber circuits are often employed, though at the expense of reduced overall efficiency.

Chapparya et al. [19] proposed an interleaved Boost–Zeta converter specifically designed for interfacing renewable energy sources with low-voltage bipolar DC microgrids. The topology demonstrated low current stress on the Zeta-side switch and exhibited excellent steady-state and dynamic performance, resulting in a simpler and more cost-effective solution compared to conventional multiport converter architectures. Nevertheless, the proposed design has certain drawbacks: it is unsuitable for high-voltage or high-power DC applications without modifications, lacks adaptability for systems requiring variable output voltages, and may operate in discontinuous conduction mode (DCM) when the duty cycle D < 0.5, potentially compromising efficiency and control stability. In [20], the analysis and simulation of an interleaved Zeta converter employing fuzzy logic control are presented, demonstrating improved settling time, enhanced output voltage regulation, and higher efficiency compared to conventional PI control methods.

Various interleaved and multistage converter topologies have been proposed in the literature. However, many of these lack bidirectional power flow capability and differ fundamentally from SEPIC and Zeta converters, which are fourth-order circuits. The SEPIC converter is derived from the Boost topology and provides a non-inverting output voltage, while the Zeta converter originates from the Buck–Boost topology and delivers a filtered output current with the same polarity as the input, functionally resembling a Buck converter.

To enhance battery integration across the wide operating range of EV inverters and commercial chargers, enabling unified power management under diverse load conditions, this paper proposes a Bidirectional Interleaved SEPIC-ZETA DC–DC Converter with phase-shifted PWM and parallel switching. The proposed topology is non-isolated, supports efficient bidirectional power flow, and is well-suited for applications involving wide input/output voltage variations, such as battery systems. Compared to conventional interleaved converter designs, the proposed converter offers several key advantages:

- (1)

- Higher voltage gain can be achieved at lower transistor duty cycles, which is particularly beneficial for sources with a wide voltage range.

- (2)

- Operates in an interleaved manner, enabling input current ripple cancelation and reducing current stress on individual switching devices through multi-phase current sharing.

- (3)

- Supports continuous conduction mode (CCM) operation, enhancing versatility under varying load conditions.

- (4)

- Is easily expandable to an n-arm configuration while maintaining a consistent output voltage setting.

- (5)

- Presents a comprehensive investigation of a bidirectional interleaved SEPIC-Zeta converter designed for high-performance applications and suitable for operation under varying voltage gain.

- (6)

- The performance of the converter is validated through experimental results under open-loop control conditions in CCM.

2. Description of the Proposed DC–DC Converter

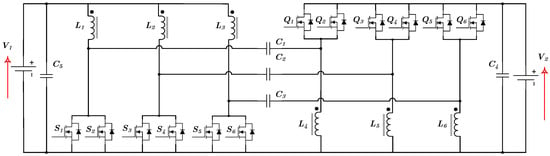

In Figure 2, the converter consists of six inductors (L1, L2, L3, L4, L5, and L6), twelve switches implemented with MOSFETs, and five capacitors. Capacitors C1, C2, and C3 are used to connect the arm containing switch S to the arm containing switch Q. Additionally, capacitors C4 and C5 are connected in parallel with the voltage sources V2 and V1, respectively. When power is transferred from the voltage port V1, typically associated with an energy storage system, to the DC bus (voltage port V2), the converter operates in step-up mode, delivering energy from V1 to regulate V2 at the required voltage. Conversely, in Buck mode, the converter charges the energy storage system. Moreover, it acts as the primary DC bus, supplying power to the load, such as a traction inverter or a high-power battery charger for electric vehicles (EVs).

Figure 2.

Proposed Three-Arms Bidirectional Interleaved SEPIC-ZETA DC–DC Converter with Interleaved PWM Technique for Parallel-Connected Switches.

The PWM modulation of the power switches is phase-shifted by 360°/6. In step-up mode, switches S1, S3, and S5 are modulated with a phase shift of 120° between each switch. For instance, if S1 is set as the reference, switches S3 and S5 are shifted by 120° and 240°, respectively. Similarly, switches S2, S4, and S6 are phase-shifted by 120° among themselves but with an additional offset of 180° relative to switches S1, S3, and S5. Consequently, if S2 begins operation with a 180° delay, switches S4 and S6 will have their angles shifted by 300° and 60°, respectively. In step-down mode, the modulation strategy remains consistent with that of step-up mode. However, the modulation signals applied to switches S1, S3, and S5 are transferred to switches Q1, Q3, and Q5, respectively. Similarly, the modulation signals assigned to switches S2, S4, and S6 are transferred to switches Q2, Q4, and Q6.

The proposed interleaved PWM technique for parallel-connected switches offers numerous advantages, including the reduction in both the volume and weight of passive components, such as capacitors, and magnetic components, such as inductors [21,22]. Furthermore, the frequency of current and voltage ripples in both ports (V1 and V2) is six times higher than the switching frequency, while the frequency of inductor ripple current is three times higher than the switching frequency. The frequency of ripple current in capacitors C1, C2, and C3 is also three times higher than the switching frequency. Additionally, the frequency of current and voltage ripples in C4 and C5 is six times higher than the switching frequency.

In each mode of operation, whether power flows from V1 to V2 or from V2 to V1, the operation of the proposed converter can be divided into three intervals, or regions, denoted as R1, R2, and R3. These regions are classified based on the combination of simultaneously conducting switches and the duty cycle range, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Operation regions for the proposed converter.

3. Operation and Steady-State Analysis of Power Flow Direction from V1 to V2 (SEPIC Mode)

This section provides a comprehensive analysis of the converter operation in Region R2, assuming CCM. It includes the theoretical waveforms of the main components, the derivation of equations for the DC voltage gain, and the mathematical expressions that describe the behavior of the inductors and capacitors.

3.1. Stage Analysis in Region R2

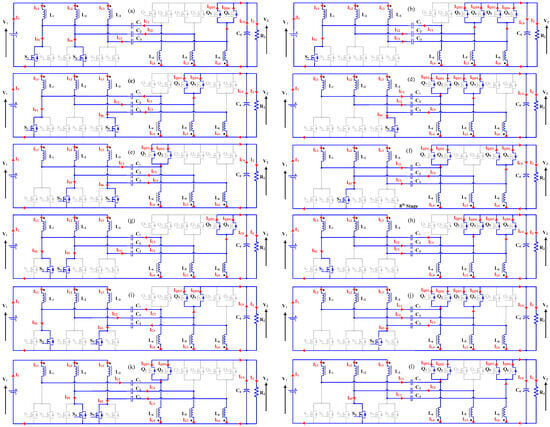

In this mode of operation, the converter consists of twelve operational stages. Due to the symmetry of these stages, a detailed analysis is conducted over half of a switching period.

1st Stage [t0 − t1]: At the initial moment t0, switches S1 and S4 are conducting, while all other switches remain off. During this stage, inductors L1, L2, L4, and L5 store energy, whereas L3 and L6 transfer energy. Capacitors C1 and C2 discharge, while C3 charges. The voltage across the inductors (L1, L2), as well as across the inductors (L4, L5), is represented as V1 and VC1, respectively. The voltage across L3 and L6 are expressed as V1 − (VC1 + V2) and −V2, respectively. The voltage across all switches, except S1 and S4, is given by VC1 + V2. The current i1(t) is equal to iL1(t) + iL2(t) + iL3(t), where iS1(t) and iS4(t) equals iL1(t) + iC1(t) and iL2(t) + iC2(t), respectively. The currents through body diodes of Q5 and Q6, iQD5(t) and iQD6(t) are expressed as (iL6(t) + iC3(t))/2. This stage concludes at t1, and the corresponding equivalent circuit is illustrated in Figure 3a. The duration of this operating stage, as well as the instantaneous currents of inductors L1, L2, and L3, switches S1 and S4, and the body diodes of switches Q5 and Q6, are defined by Equations (1)–(4), respectively.

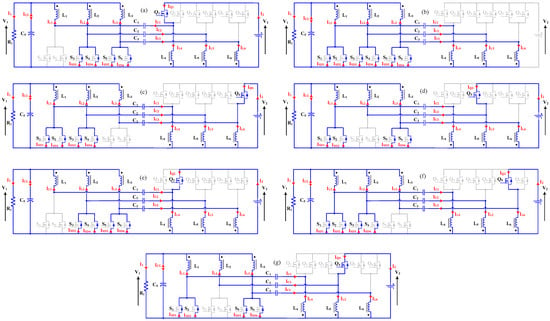

Figure 3.

Equivalent circuits of the proposed converter operating in the power flow direction from V1 to V2. (a) 1st Stage; (b) 2nd Stage; (c) 3rd Stage; (d) 4th Stage; (e) 5th Stage; (f) 6th Stage; (g) 7th Stage; (h) 8th Stage; (i) 9th Stage; (j) 10th Stage; (k) 11th Stage; (l) 12th Stage.

2nd Stage [t1 − t2]: At the initial moment t1, switch S1 remains on, and switch S4 is turned off, while all other switches remain off. During this stage, inductors L1 and L4 store energy, whereas inductors L2, L3, L5, and L6 transfer energy. Capacitor C1 discharges, while capacitors C2 and C3 charge. The voltage across L1 and L4 is equal to V1 and VC1, respectively. The voltage across the inductors (L2 and L3), as well as the inductors (L5 and L6) is equal toV1 − (VC1 + V2) and −V2, respectively. The voltage across all switches, except S1, is given by VC1 + V2. The current i1(t) is equal to iL1(t) + iL2(t) + iL3(t), where the current through switch S1, iS1(t), equals iL1(t) + iC1(t), and the currents through body diodes of Q3, Q4, Q5, and Q6, iQD3(t), iQD4(t), iQD5(t), and iQD6(t), are expressed as (iL6(t) + iC3(t))/2. This stage concludes at t2, and the corresponding equivalent circuit is illustrated in Figure 3b. The duration of this stage, along with the instantaneous currents of L1–L3, S1, and the body diodes of Q3–Q6, are defined by Equations (5)–(8), respectively.

3rd Stage [t2 − t3]: At the initial moment t2, switches S1 and S6 are conducting, while all other switches remain off. During this stage, inductors L1, L3, L4, and L6 store energy, whereas inductors L2 and L5 transfer energy. Capacitors C1 and C3 discharge, while capacitor C2 charges. The voltage across the inductors (L1 and L3), as well as across the inductors (L4 and L6), is defined as V1 and VC1, respectively. The voltage across L2 and L5 is described by as V1 − (VC1 + V2) and −V2, respectively. The voltage across all switches, except S1 and S6, is equal to VC1 + V2. The current i1(t) is equal to iL1(t) + iL2(t) + iL3(t), where the currents through switches S1 and S6, iS1(t) and iS6(t), are equal to iL1(t) + iC1(t) and iL3(t) + iC3(t), respectively. The currents through body diodes of Q3, Q4, iQD3(t) and iQD4(t), are expressed as (iL5(t) + iC2(t))/2. This stage concludes at t3, and the corresponding equivalent circuit is illustrated in Figure 3c. Stage duration and instantaneous currents of L1–L3, S1 and S6, and body diodes of Q3–Q4 are given by (9)–(12), respectively.

4th Stage [t3 − t4]: At the initial moment t3, switch S6 remains on, and switch S1 is turned off, while all other switches remain off. During this stage, inductors L3 and L6 store energy, whereas inductors L1, L2, L4, and L5 transfer energy. Capacitor C3 discharges, while capacitors C1 and C2 charge. The voltage across inductors L3 and L6 is equal to V1 and VC1, respectively. The voltage across the inductors (L1 and L2), as well as the inductors (L4 and L5), is equal to V1 − (VC1 + V2) and −V2, respectively. The current i1(t) is defined as the sum iL1(t) + iL2(t) + iL3(t), while the current through switch S6, iS6(t), is iL3(t) + iC3(t). The currents through the body diodes of Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4, denoted as iQD1(t), iQD2(t), iQD3(t), and iQD4(t), are expressed as (iL4(t) + iC1(t))/2 and (iL5(t) + iC2(t))/2, respectively. This stage concludes at t4, and the corresponding equivalent circuit is illustrated in Figure 3d. The duration of this stage, along with the instantaneous currents of L1–L3, S6, and the body diodes of Q1–Q4, is defined by Equations (13)–(16), respectively.

5th Stage [t4 − t5]: At the initial moment t4, switches S3 and S6 are conducting, while all other switches remain off. During this stage, the inductors L2, L3, L5, and L6 store energy, whereas the inductors L1 and L4 transfer energy. The capacitors C2 and C3 discharge, while the capacitor C1 charges. The voltage across the inductors (L2 and L3), as well as across the inductors (L5 and L6), is represented as V1 and VC1, respectively. The voltage across L1 and L4 is expressed as V1 − (VC1 + V2) and −V2, respectively. The current i1(t) is defined as iL1(t) + iL2(t) + iL3(t), where the currents through switches S3 and S6, iS3(t) and iS6(t), are given by iL2(t) + iC2(t) and iL3(t) + iC3(t), respectively. The currents through the body diodes of Q1 and Q2, denoted as iQD1(t) and iQD2(t), are expressed as (iL4(t) + iC1(t))/2. This stage concludes at t5, and the corresponding equivalent circuit is illustrated in Figure 3e. The duration of this operating stage, as well as the instantaneous currents of inductors L1–L3, switches S3 and S6, and the body diodes of switches Q1 and Q2, is defined by Equations (17)–(20), respectively.

6th Stage [t5 − t6]: At the initial moment t5, switch S3 remains on, while switch S6 is turned off and all other switches remain off. During this stage, inductors L2 and L5 store energy, whereas inductors L1, L3, L4, and L6 transfer energy. Capacitor C2 discharges, while capacitors C1 and C3 charge. The voltage across inductors L2 and L5 corresponds to V1 and VC1, respectively. The voltage across the inductors (L1 and L3), as well as the inductors (L4 and L6), corresponds to V1 − (VC1 + V2) and -V2, respectively. The voltage across all switches, except S3, is given by VC1 + V2. The current i1(t) is defined as the sum iL1(t) + iL2(t) + iL3(t), while the current through switch S3, iS3(t), is iL2(t) + iC2(t). The currents through the body diodes of Q1, Q2, Q5, and Q6, denoted as iQD1(t), iQD2(t), iQD5(t), and iQD6(t), are expressed as (iL4(t) + iC1(t))/2 and (iL6(t) + iC3(t))/2, respectively. This stage concludes at t6, and the corresponding equivalent circuit is illustrated in Figure 3f. The duration of this stage, along with the instantaneous currents of L1–L3, S3, and the body diodes of Q1, Q2, Q5, and Q6, is defined by Equations (21)–(24), respectively.

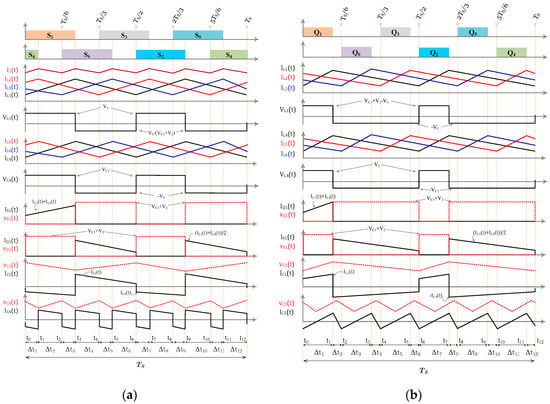

The 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th stages are identical to the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th stages, although they involve different switches from the “S” set engaged. The equivalent circuits for these stages are detailed in Table 2. Figure 4a presents the voltage and current waveforms for the main components in the power flow direction from V1 to V2. The theoretical analysis indicates that the current ripple frequency in the inductors (L1, L2, L3, L4, L5 and L6) and capacitors (C1, C2, and C3) is twice the switching frequency, while the ripple current at V1 and V2 is six times the switching frequency.

Table 2.

Circuits for power flow direction from V1 to V2.

3.2. DC Voltage Gain Expression for Power Flow from V1 to V2

The DC voltage gain in CCM for R2 is given by (25). A comprehensive understanding of this behavior is crucial for the accurate sizing of the proposed converter.

The time intervals 2Δt1 + Δt2 and Δt1 + 2Δt2 is given by (26) and (27).

By substituting (26) and (27) into (25), Equation (28) is obtained.

The voltage VC1 is calculated by integrating the average value of the current in inductor L4, as expressed by:

By solving Equation (29), VC1 is defined by Equation (30).

By substituting (30) into (28), the expression for the DC voltage gain in the power flow direction from V1 to V2 is derived, as presented in (31).

Figure 4.

Theoretical waveforms of voltage and current in CCM: (a) for power flow direction from V1 to V2; (b) for power flow direction from V2 to V1.

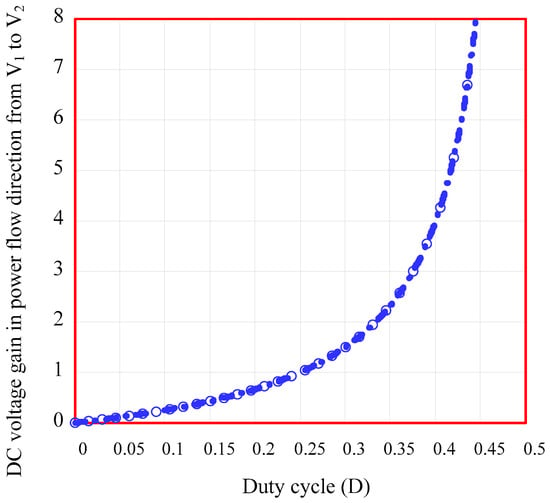

Using (31), Figure 5 presents the DC voltage gain of the proposed converter in the power flow direction from V1 to V2. The results clearly indicate that the proposed converter exhibits a step-down and step-up characteristic, wherein the gain increases exponentially with the duty cycle D. This behavior demonstrates the converter’s capability to efficiently step up or step down the input voltage, as required by the application. Moreover, the observed gain profile is consistent with the performance of converters studied in [14,17], underscoring the adaptability and efficacy of the proposed topology.

Figure 5.

DC voltage gain in power flow direction from V1 to V2.

3.3. Sizing of Passive Elements and Calculation of Component Stresses

In this section, the sizing of the inductors and capacitors is presented, including the calculations for the voltage and current stresses of the main components. During the time interval D⋅TS, the inductors experience a voltage V1, and their inductance is determined using (32).

By substituting Equation (31) into Equation (32), Equation (33) is derived, which determines the required values of the inductances

L1, L2, and L3 as functions of D, V2, fs, and ΔIL, ensuring the converter operates in CCM.

Equation (33) is used to determine the inductance values for L1, L2, and L3, as well as for L4, L5, and L6.

The average current through inductors L1, L2, and L3, as a function of the duty cycle (D) and the current I2, is given by (34).

The average current through the inductors L4, L5, and L6 is expressed in (35).

The average and RMS current values through the switches S are calculated using (36) and (37), respectively.

Equations (38) and (39) provide the calculations for the average and RMS currents through the body diode of the switches Q.

The maximum voltage across all switches is given by (40).

The RMS value of the current through C1, C2, and C3 is determined by analyzing the equivalent circuits shown in Figure 3. When the switches are on, the current through C1, C2, and C3 is given by . When the switches are off, the current through C1, C2, and C3 is given by . The RMS currents for C1, C2, and C3 are presented in Equation (41).

From Figure 3 and Figure 4a, it can be seen that capacitors C1, C2, and C3 discharge when the switches S are turned on, and charge when the switches are turned off. Therefore, the capacitance values of the capacitors are given by (42).

The maximum voltage values for C1, C2 and C3 are determined by Equation (43).

From Figure 4a, it can be seen that capacitor C4 discharges during interval Δt1 and charges during interval Δt2. Therefore, applying RMS value integral, Equation (44) is obtained, following which the capacitance of C4 is given by (45).

4. Operation and Steady-State Analysis of Power Flow Direction from V2 to V1 (Zeta Mode)

This section provides a detailed analysis of the power flow direction from V2 to V1 over half of a switching period in Region R1. It presents the theoretical waveforms for the main components, alongside the relevant equations for DC voltage gain, component stress, and the sizing of passive elements.

4.1. Stage Analysis in Region R1

1st Stage [t0 − t1]: The first stage starts at t0, when the switch Q1 is turned on, while all others switches remain off. During this stage, inductors L4 and L1 store energy, whereas inductors L5, L6, L2, and L3 transfer energy. Capacitor C1 charges, while capacitors C2 and C3 discharge. The voltage across L4 and L1 is equal to V2 and (VC1 + V2) − V1, respectively. The voltage across the inductors (L5 and L6), as well as the inductors (L2 and L3) is equal to −VC1 and −V1, respectively. The voltage across all switches, except Q1, is given by VC1 + V2. The current i2(t) is equal to iQ1(t), where the current through switch Q1, iQ1(t), equals iL4(t) + iC1(t), and the currents through body diodes of S3, S4, S5, and S6, iSD3(t), iSD4(t), iSD5(t), and iSD6(t), are expressed as (iL2(t) + iC2(t))/2. This stage concludes at t2, and the corresponding equivalent circuit is illustrated in Figure 6a. The duration of this stage, along with the instantaneous currents of inductors L4–L6, switch Q1, and the body diodes of S3, S4, S5, and S6, is defined by Equations (46)–(49), respectively.

Figure 6.

Equivalent circuits of the proposed converter operating in the power flow direction from V2 to V1. (a) 1st Stage; (b) 2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th, 10th, 12th Stage; (c) 3rd Stage; (d) 5th Stage; (e) 7th Stage; (f) 9th Stage; (g) 11th Stage.

2nd Stage [t1 − t2]: The second stage starts at t1, when all switches (Q1–Q6) remain turned off. During this stage, the inductors L1, L2, L3, L4, L5, and L6 transfer the previously stored energy toward the load and the capacitors. At the same time, capacitors C1, C2 and C3 discharge, providing additional energy to the load and contributing to the current through the inductors. The voltage across inductors L1, L2, and L3 is equal to −V1, and the voltage across inductors L4, L5, and L6 is equal to −VC1. The voltage across all switches is determined by VC1 + V2. The current i1(t) corresponds to the sum of iL1(t), iL2(t) and iL3(t), while the current i2(t) equals iL4(t) + iL5(t) + iL6(t). This stage ends at t2, and the corresponding equivalent circuit is shown in Figure 6b. Stage duration and instantaneous currents of L4–L6 and body diodes of S1–S6 are defined by (50)–(52), respectively.

3rd Stage [t2 − t3]: The third stage begins at t2, when the switch Q6 is turned on, while all other switches remain off. During this stage, inductors L6 and L3 store energy, whereas inductors L4, L5, L2, and L1 transfer energy. The capacitor C3 charges, while capacitors C1 and C3 discharge. The voltage across L6 and L3 is equal to V2 and (VC1 + V2) − V1, respectively. The voltage across the inductors (L5 and L4), as well as the inductors (L3 and L2) is equal to −VC1 and −V1, respectively. The voltage across all switches, except Q6, is given by VC1 + V2. The current i2(t) is equal to iQ6(t), where the current through switch Q6, iQ6(t), equals iL6(t) + iC3(t), and the currents through body diodes of S1, S2, S3, and S4, iSD1(t), iSD2(t), iSD3(t), and iSD4(t), are expressed as (iL1(t) + iC1(t))/2. This stage concludes at t4, and the corresponding equivalent circuit is presented in Figure 6c. Stage duration and instantaneous currents of L4–L6, Q6, and body diodes of S1-S4 are defined by Equations (53)–(56), respectively.

4th Stage [t3 − t4]: The fourth stage starts at t3 and is identical to the second stage. All switches remain off, while inductors L1–L6 transfer energy and capacitors C1–C3 discharge. The voltages across inductors and switches, as well as the current paths, follow the same behavior as in the second stage. This stage ends at t4, and the corresponding equivalent circuit is shown in Figure 6b. The duration of this stage and the instantaneous currents of L4–L6 and the body diodes of S1–S6 are given by Equations (57)–(59), respectively,

5th Stage [t3 − t4]: At the initial time t5, the switch Q3 is turned on, while all other switches remain off. During this stage, inductors L5 and L2 store energy, whereas inductors L6, L4, L3, and L1 transfer energy. The capacitor C2 charges, while capacitors C1 and C3 discharge. The voltage across L5 and L2 is equal to V2 and (VC1 + V2) − V1, respectively. The voltage across the inductors L6 and L4, as well as the inductors L3 and L1 is equal to −VC1 and −V1, respectively. The voltage across all switches, except Q3, is given by VC1 + V2. The current i2(t) is equal to iQ3(t), where the current through switch Q3, iQ3(t), equals iL5(t) + iC2(t), and the current through body diodes of S1, S2, S5, and S6, iSD1(t), iSD2(t), iSD5(t), and iSD6(t), is expressed as (iL1(t) + iC1(t))/2. This stage concludes at t6, and the corresponding equivalent circuit is presented in Figure 6d. The duration of this stage, as well as the instantaneous currents of inductors L4–L6 and the body diodes of S1, S2, S5, and S6, is characterized by Equations (60)–(62), respectively.

6th Stage [t5 − t6]: The sixth stage is identical to the second and fourth stages. All switches remain off, inductors L1–L6 transfer energy, and capacitors C1, C2 and C3 discharge. The equivalent circuit is shown in Figure 6b.

The 7th, 9th, and 11th stages are similar to the 1st, 3rd, and 5th stages, respectively, with the only difference being the involvement of different switches from the “Q” group. The 8th, 10th, and 12th stages are identical to the 2nd, 4th, and 6th stages. The corresponding equivalent circuits for these stages are provided in Table 3. Figure 4b illustrates the voltage and current waveforms of the main components during the power flow from V2 to V1. The theoretical analysis reveals that the ripple current frequency in the inductors (L1, L2, L3, L4, L5, and L6) and capacitors (C1, C2, and C3) is twice the switching frequency. In contrast, the ripple current at V1 and V2 occurs at six times the switching frequency.

Table 3.

Circuits for power flow direction from V2 to V1.

4.2. DC Voltage Gain Expression for Power Flow from V2 to V1

In CCM and for power flow from V2 to V1, the expression for the DC voltage gain can be derived by analyzing the average voltage across one of the inductors, as follows:

Substituting the time intervals Δt1 and Δt2 into Equation (66) yields Equation (67).

The voltage VC1 is determined by integrating the average current through inductor L4, as given by:

Solving Equation (68) yields the voltage VC1, as defined in Equation (69).

Substituting Equation (69) into Equation (67) yields the expression for the DC voltage gain in the power flow direction from V2 to V1, as given in Equation (70).

Using Equation (70), the DC voltage gain of the proposed converter in the power flow direction from V2 to V1 is analyzed. It exhibits the same DC voltage gain characteristics as in the power flow direction from V1 to V2, with the DC voltage gain increasing exponentially as the duty cycle (D) varies (see Figure 5). This behavior demonstrates the converter’s capability to effectively step up or step down the input voltage, accommodating diverse application requirements.

4.3. Component Stress Determination and Passive Elements Sizing

As the converter handles equal power in both power flow directions, the component stresses remain identical. The only difference lies in the duty cycle values between the power flow from V1 to V2 and the power flow from V2 to V1. Consequently, the duty cycle for the power flow from V1 to V2 is determined as a function of the duty cycle for the power flow from V2 to V1. It is important to note that the DC gains for the power flow from V1 to V2 and from V2 to V1 are determined by Equations (31) and (70). These gains can also be expressed as:

where represents the duty cycle value for power flow from V1 to V2, and denotes the duty cycle value for the power flow from V2 to V1. The DC gains in both directions are inversely proportional, expressed as . Substituting (71) and (72) into this relationship yields:

By manipulating Equation (73), the duty cycle in can be expressed as a function of the duty cycle in , as shown in Equation (74).

The output capacitance C5 in the power flow from V2 to V1 is directly related to the current ripple in the inductors L1, L2, and L3, as the capacitor functions to smooth out the voltage variations at the output. The output capacitance must be sized to provide the necessary charge to maintain the output voltage stability during the switching cycles. The effective current in the capacitor is determined by the integral of Equation (75), using Figure 4b and Figure 6.

Substituting the time intervals Δt1 and Δt2 into Equation (75) gives rise to Equation (76).

Upon solving the integral of Equation (77), Equation (78) is obtained, which defines the capacitance value C5.

5. Technical Comparison with Reference Converter Architectures

To assess the performance of the proposed converter, a comprehensive comparison with widely adopted and representative topologies from the literature [14,16,17,23,24,25] is presented in Table 4. This comparison considers operation under CCM, voltage gain, current stresses on the main switch at the low-voltage side, the nature of the current waveform, and the frequency characteristics of current and voltage ripples at both low- and high-voltage ports. While some of the referenced converters are originally unidirectional, their bidirectional counterparts are considered here to ensure a fair and consistent evaluation.

Table 4.

Comparison between the proposed architecture and selected literature topologies.

As summarized in Table 4, the converters presented in [14,17] exhibit similar voltage gain and current stress characteristics but do not support bidirectional operation. Specifically, the converter in [14] is limited to bipolar DC network applications and requires a larger number of passive components. Alharbi et al. [17] demonstrate that employing modern WBG devices (SiC/GaN) can improve efficiency. However, this architecture results in significant current stress on the switches when processing medium power levels.

The converter in [16] is tailored for bipolar DC microgrid applications and features asymmetric operation when the duty cycle deviates from 0.5, which limits its voltage gain and operational flexibility. In contrast, the proposed converter offers an extended voltage gain range while operating with lower duty cycles, thereby reducing conduction losses and enhancing efficiency. Conventional solutions such as those in [23,24] either exhibit fixed maximum/minimum gains, impose higher current stresses on the transistors, or rely on multiple conversion stages [25] with complex driving circuits. Across a wide operating range, the proposed converter demonstrates superior performance, including notably reduced current stress and high efficiency. Furthermore, the interleaving effect and phase–shift modulation enable the use of smaller inductance and capacitance values. The main design trade-off is the increased number of transistors and associated gate drivers required to enable interleaved operation.

An important performance aspect highlighted in Table 4 is the frequency of current and voltage ripples at both ports and across the inductors. Conventional converters such as [14,16,23] exhibit relatively low ripple frequencies, typically 2 × fs or 3 × fs, which necessitate larger filter components to achieve acceptable ripple attenuation. In contrast, the proposed converter achieves ripple frequencies of 6×fs both at the ports and across the inductors. This higher ripple frequency substantially relaxes the filtering requirements, enabling the use of smaller passive components and contributing to a more compact and lightweight design.

Finally, while many of the topologies considered for comparison produce highly discontinuous or pulsating currents on the high-voltage side, the proposed converter effectively mitigates this drawback. By employing inductors L4, L5, and L6, it ensures low output current ripple, thereby minimizing stress on the output filter capacitor and enhancing overall system reliability

6. Experimental Results and Efficiency Analysis

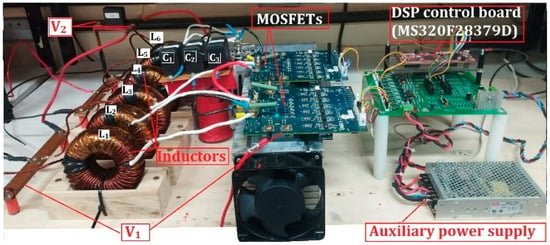

To validate the feasibility of the proposed 5 kW converter, a laboratory prototype was implemented, as shown in Figure 7. Table 5 summarizes the converter specifications and component parameters. The gating signals for the power switches are generated using a TMS320F28379D digital signal controller and applied to the MOSFET drivers. The experimental waveforms were acquired with a Tektronix DPO3014 oscilloscope. A video demonstrating the real-time operation and dynamic behavior of the prototype under laboratory conditions is available in the Supplementary Materials. This section investigates two operating modes: power flow from V1 to V2 and from V2 to V1.

Figure 7.

Prototype of the proposed converter and main components.

Table 5.

Experimental parameters and component specifications.

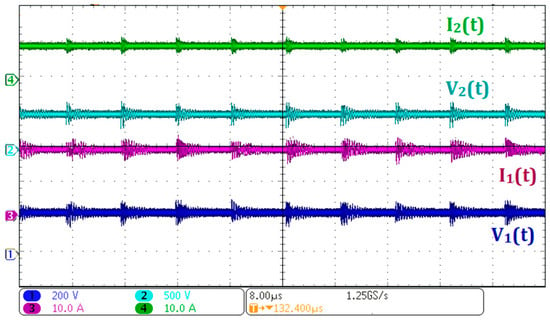

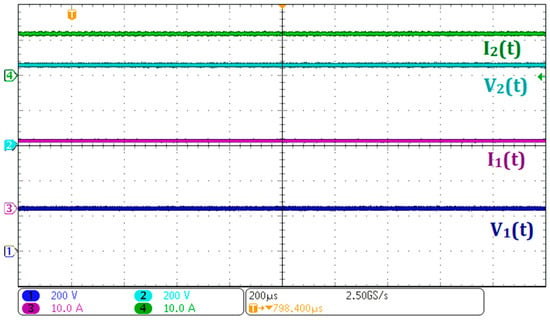

6.1. Experimental Results for Power Flow from V1 to V2

Figure 8 presents the current and voltage waveforms at the V1 and V2 terminals. It can be observed that the voltage at V1 (Ch1) is 220 V, while the voltage at V2 (Ch2) reaches 450 V. Additionally, the currents at V1 and V2 are shown in Ch3 and Ch4, respectively. These results are consistent with the power flow from V1 to V2 and validate Equation (31), which defines the voltage gain in this operating mode. Therefore, the experimental results are in close agreement with the theoretical predictions, confirming the accuracy of the proposed converter.

Figure 8.

Experimental waveforms for power flow from V1 to V2: (Ch1) voltage at V1; (Ch2) voltage at V2; (Ch3) current at V1 (I1); (Ch4) current at V2 (I2).

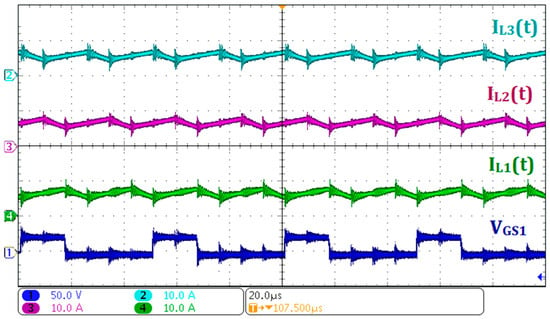

Figure 9 shows, in Ch1, the gating signal of S1, while Ch2, Ch3, and Ch4 display the currents IL3, IL2, and IL1, respectively. It is also observed that the ripple frequency of the inductor currents (L1, L2, and L3) is twice the switching frequency. As a result of the three-phase interleaved operation, the ripple frequency of both the current and voltage at V1 is six times the switching frequency. This feature enables the use of smaller filter capacitors and represents one of the advantages of the proposed converter compared to conventional interleaved converters.

Figure 9.

Experimental waveforms for power flow from V1 to V2: (Ch1) gating signal of S1; (Ch2) current IL3 of inductor L3; (Ch3) current IL2 of inductor L2; (Ch4) current IL1 of inductor L1.

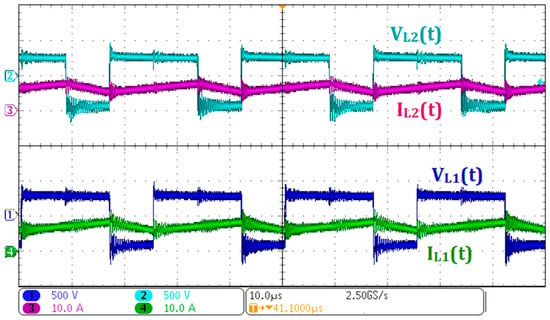

Figure 10 presents the voltage and current waveforms of inductors L1 and L2, where Ch1 and Ch4 correspond to the voltage across and current through inductor L1, respectively, while Ch2 and Ch3 display the voltage across and current through inductor L2. It can be observed that during the energy storage interval, the voltage across the inductors equals V1, while during the energy transfer interval, it equals V1 − (VC1 − V2). These results are in close agreement with the theoretical analysis previously presented, thereby validating the expected operational behavior of the proposed converter.

Figure 10.

Experimental waveforms for power flow from V1 to V2: (Ch1) voltage across L1 and (Ch4) current through L1; (Ch2) voltage across L2 and (Ch3) current through L2.

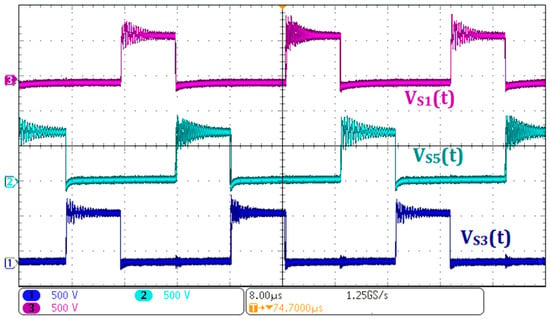

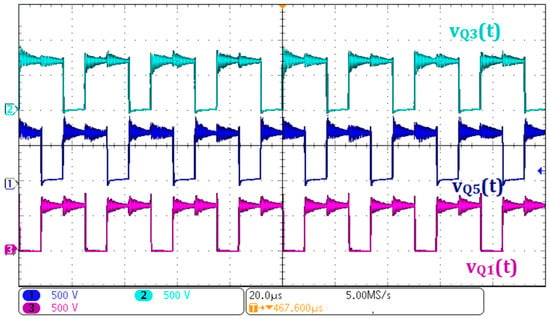

Figure 11 shows the voltage waveforms across switches S1, S3, and S5, corresponding to channels Ch3, Ch1, and Ch2, respectively. It can be observed that the peak voltages across these switches reach values close to those predicted by Equation (40).

Figure 11.

Experimental waveforms for power flow from V1 to V2: (Ch1) voltage across S3; (Ch2) voltage across S5; (Ch3) voltage across S1.

Figure 12 shows the voltages across the body diodes of switches Q1, Q3, and Q5, displayed in Ch1, Ch2, and Ch3, respectively. The voltages across the body diodes correspond closely to those measured across switches S, indicating similar voltage stress on these components.

Figure 12.

Experimental waveforms for power flow from V1 to V2: (Ch1) voltage across the body diode of Q1; (Ch2) voltage across the body diode of Q3; (Ch3) voltage across the body diode of Q5.

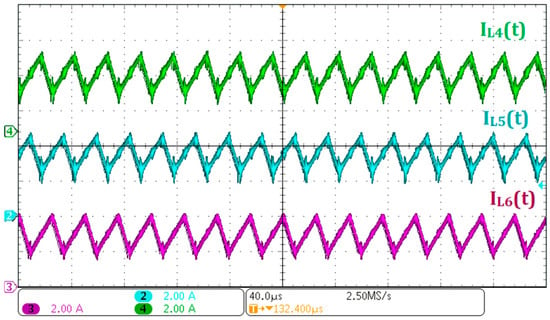

Figure 13 presents the current waveforms of inductors L5, L6, and L4, displayed in Ch2, Ch3, and Ch4, respectively. It is observed that the ripple frequency of the inductor currents (L4, L5, and L6) is twice the switching frequency, as also observed in L1, L2, and L3. Due to the three-phase interleaved operation, the ripple frequency of both the current and voltage at V2 reaches six times the switching frequency. This characteristic allows the use of a smaller filter capacitor C4, thereby contributing to a more compact and efficient converter design.

Figure 13.

Experimental waveforms for power flow from V1 to V2: (Ch2) current IL5 of inductor L5; (Ch3) current IL6 of inductor L6; (Ch4) current IL4 of inductor L4.

6.2. Experimental Results for Power Flow from V2 to V1

Figure 14 presents the current and voltage waveforms at the V2 and V1 terminals. Ch2 shows the voltage at V2, approximately 450 V, while Ch1 displays the voltage at V1, reaching 220 V. The currents at the V2 and V1 ports are shown in Ch4 and Ch3, respectively. These values align with the power flow direction from V2 to V1 and validate Equation (70), which defines the voltage gain in this operating mode. The experimental results closely match the theoretical predictions, confirming the accuracy of the proposed converter model.

Figure 14.

Experimental waveforms for power flow from V2 to V1: (Ch1) voltage at V1; (Ch2) voltage at V2; (Ch3) current at V1 (I1); (Ch4) current at V2 (I2).

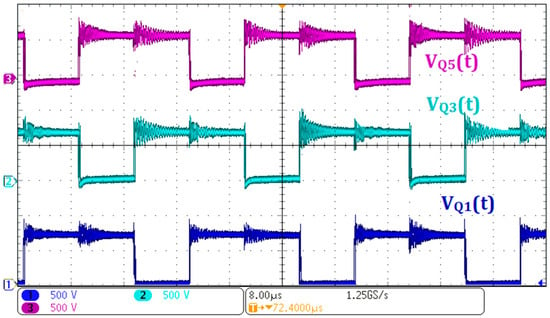

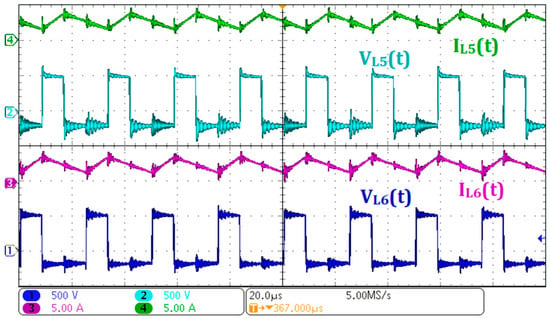

Figure 15 illustrates the voltage and current waveforms of inductors L5 and L6. The voltage across and current through inductor L6 are shown in Ch1 and Ch3, respectively, while Ch2 and Ch4 display the voltage across and current through inductor L5. During the energy storage interval, the voltage across the inductors is equal to V2; during the energy transfer interval, it corresponds to VC1 + V2 − V1. These observed behaviors closely match the theoretical analysis, confirming the expected operation of the converter. Figure 16 presents the voltages across switches Q1, Q3, and Q5, shown in Ch3, Ch2, and Ch1, respectively. The measured voltage across the switches closely matches the theoretical value predicted by (40).

Figure 15.

Experimental waveforms for power flow from V2 to V1: (Ch1) voltage across L6 and (Ch3) current through L6; (Ch2) voltage across L5 and (Ch4) current through L5.

Figure 16.

Experimental waveforms for power flow from V2 to V1: (Ch1) voltage across Q5; (Ch2) voltage across Q3; (Ch3) voltage across Q1.

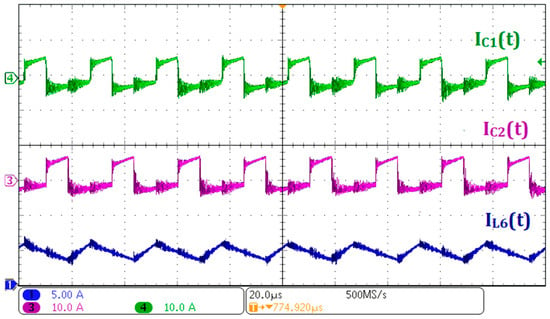

Figure 17 presents the current waveforms of inductor L6 and capacitors C1 and C2, shown in Ch2, Ch3, and Ch4, respectively. It is observed that the ripple frequency of both the inductor and the capacitors is twice the switching frequency. Owing to the three-arm interleaved operation, the ripple frequency of both the current and voltage at ports V2 and V1 increases to six times the switching frequency. This characteristic enables the use of smaller filter components, including capacitors and inductors, thereby contributing to a more compact and higher-efficiency converter design.

Figure 17.

Experimental waveforms for power flow from V2 to V1: (Ch1) current IL6 of inductor L6; (Ch3) current IC2 of capacitor C3; (Ch4) current IC1 of capacitor C1.

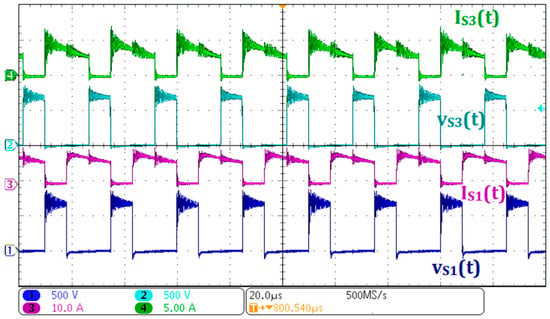

Figure 18 presents the experimental voltage and current waveforms of the body diodes of switches S1 and S3 during power flow from V2 to V1. The voltage across the body diodes of S1 and S3 is shown in Ch1 and Ch2, respectively, while the corresponding currents are displayed in Ch3 and Ch4. The observed waveforms confirm the correct operation of the body diodes during the commutation intervals, in accordance with the expected behavior of the converter in this mode. These results further validate the theoretical analysis and demonstrate the converter’s capability to handle bidirectional power flow with proper diode conduction.

Figure 18.

Experimental waveforms for power flow from V2 to V1: (Ch1) voltage across the body diode of S1; (Ch2) voltage across the body diode of S3; (Ch3) current through the body diode of S1; (Ch4) current through the body diode of S3.

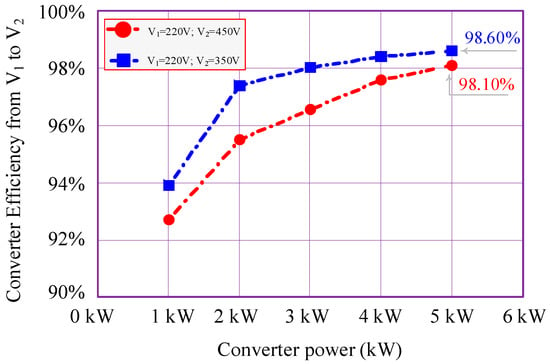

Figure 19 presents the experimental efficiency of the converter at two output voltage levels: V2 = 450 V (red curve) and V2 = 350 V (blue curve). In both cases, the input voltage is fixed at V1 = 220 V, and the converter operates with power flow from V1 to V2. The converter achieves high efficiency across the entire power range. For V2 = 350 V, the maximum efficiency reaches 98.60% at 5 kW, while for V2 = 450 V, the efficiency peaks at 98.10%. In both scenarios, the efficiency increases with output power, approaching its maximum value as power reaches 5 kW. These results demonstrate the converter’s ability to maintain high efficiency under varying voltage conditions and load levels.

Figure 19.

Efficiency of the proposed converter during power flow from V1 to V2.

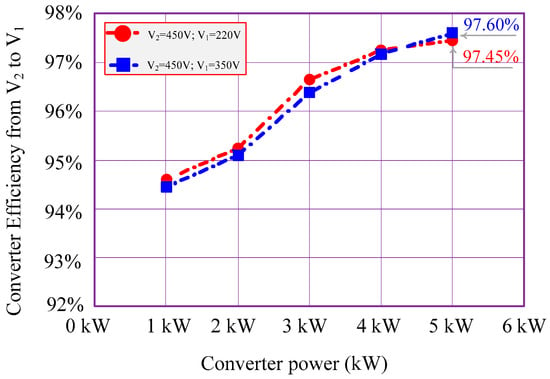

Figure 20 presents the experimental efficiency of the converter for different input voltage levels: V1 = 220 V (red curve) and V1 = 350 V (blue curve), with a fixed output voltage of V2 = 450 V, operating in the power flow direction from V2 to V1. The converter maintains high efficiency across the entire power range. At 5 kW, the maximum efficiency reaches 97.60% for V1 = 350 V and 97.45% for V1 = 220 V. For both voltage levels, efficiency increases with output power and stabilizes near its maximum at higher power levels. However, in this power flow direction, efficiency shows a slight reduction compared to the power flow from V1 to V2, as observed in the previous case. These results confirm the converter’s ability to deliver high efficiency under bidirectional power flow conditions.

Figure 20.

Efficiency of the proposed converter during power flow from V2 to V1.

7. Conclusions

This paper presents a high-efficiency bidirectional interleaved SEPIC–ZETA DC–DC converter with a phase-shifted PWM technique and multidevice structure using parallel-connected switches, specifically designed for advanced electric vehicle applications. The proposed topology successfully addresses key challenges in modern bidirectional power conversion, offering significant advantages such as extended voltage gain, reduced current and voltage ripple, and minimized component stress. The three-phase interleaving architecture enables compact and lightweight converter implementation with smaller passive components.

A comprehensive theoretical analysis is provided, covering the steady-state operation in both power flow directions, supported by detailed mathematical modeling and passive element sizing. Experimental validation was performed using a 5 kW prototype, demonstrating excellent performance with a peak efficiency of 98.6% in step-up mode and 97.6% in step-down mode. The results confirm the converter’s ability to efficiently manage energy transfer in bidirectional applications, with high power density and superior ripple mitigation.

Future work will focus on developing a closed-loop control strategy, evaluating dynamic performance, and extending the proposed architecture to multi-arm configurations for higher power and voltage applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en18246423/s1. A video showing the proposed converter operating under experimental conditions is provided with this paper.

Author Contributions

R.S.d.S., M.B.E.K., R.M., B.B.E.K., D.d.A.H., P.P.P. and F.L.M.A. contributed to the writing and revision of this paper, with tasks and responsibilities shared among the co-authors. The experimental implementation was carried out by R.S.d.S. under the supervision of M.B.E.K. and R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by FUNCAP—Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico and ECITECE—Secretaria da Ciência, Tecnologia e Educação Superior (Research and Innovation Network on Renewable Energy—Rede VERDES, grant no. 07548003/2023). The contribution of Menaouar Berrehil El Kattel was supported by the Federal University of Ceará.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Federal University of Ceará (UFC) and FUNCAP—Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—for their institutional support. The authors also acknowledge the Energy Processing and Control Group (GPEC) for providing laboratory facilities, equipment, and technical assistance during the experimental activities.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Benameur Berrehil El Kattel was employed by the company Top Gloves Latex Industries. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Bose, B.K. Global Energy Scenario and Impact of Power Electronics in 21st Century. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2013, 60, 2638–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, D.; Duan, J.; Gu, R. Research on High-Performance Multiphase DC–DC Converter Applied to Distributed Electric Propulsion Aircraft. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 3545–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad Upputuri, R.; Subudhi, B. A Two-Stage Bidirectional DC–DC Converter with a Wide Output Voltage Range for DC Fast Charging Stations in E-Mobility Applications. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Mishra, A.K.; Gupta, K.K.; Siwakoti, Y.P. High Voltage Gain Bidirectional DC-DC Converters for Supercapacitor Assisted Electric Vehicles: A Review. CPSS Trans. Power Electron. Appl. 2022, 7, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, B.; Qu, J.; Feng, S.-P.; Chu, P.K. Optimization and cutting-edge design of fuel-cell hybrid electric vehicles. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 18392–18423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, K.D.N.; Kattel, M.B.E.; Praça, P.P.; Junior, D.S.O.; Antunes, F.L.M.; Barreto, L.H.S.C. 13 kW High-Efficiency Six-Arm High-Gain Transformerless Floating Interleaved Bidirectional Buck–Boost DC–DC Converter for EV Applications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 183901–183917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igor Carvalho Lobato, G.; Berrehil El Kattel, M.; Marcelo Antunes, F.L.; Silva, S.M.; de Jesus Cardoso Filho, B. A novel topology of a non-isolated bidirectional multiphase single inductor DC–DC converter. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2025, 53, 2467–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.; Kattel, M.B.E.; Oliveira, S.V.G. Multiphase Interleaved Bidirectional DC/DC Converter With Coupled Inductor for Electrified-Vehicle Applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 2533–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-E.; Huang, W.-C. Dual-Input Interleaved Bidirectional DC–DC Converter for Light Electric Vehicles. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 5037–5051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Giménez, J.; Lázaro, A.; Mayor, Á.; López-López, J.; Barrado, A. New Bidirectional Isolated Three-Phase DC–DC Converter with Parallel-to-Serial Configuration for Energy Applications. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2025, 6, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.A.; Alcaide, A.M.; Dahidah, M.; Ethni, S.; Pickert, V.; Leon, J.I. Rotating Phase Shedding for Interleaved DC–DC Converter-Based EVs Fast DC Chargers. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 1901–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Current ripple bounds in interleaved DC-DC power converters. In Proceedings of the 1995 International Conference on Power Electronics and Drive Systems, PEDS 95, Singapore, 21–24 February 1995; Volume 2, pp. 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnimaya, V.V.; George, S.; Paul, P.J. A Comprehensive study on Traditional and Derived SEPIC Topologies. In Proceedings of the 2022 Third International Conference on Intelligent Computing Instrumentation and Control Technologies (ICICICT), Kannur, India, 11–12 August 2022; pp. 1471–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, E.D.; Litrán, S.P.; Prieto, M.B.F. Combination of interleaved single-input multiple-output DC-DC converters. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 8, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alargt, F.S.; Ashur, A.S.; Kharaz, A.H. Multiphase Interleaved SEPIC Converter Using ADM Control loop Suitable for Hybrid Energy Source Integration. In Proceedings of the 2022 Second International Conference on Sustainable Mobility Applications, Renewables and Technology (SMART), Cassino, Italy, 23–25 November 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, P.; Agarwal, V. Novel Boost-SEPIC Type Interleaved DC–DC Converter for Mitigation of Voltage Imbalance in a Low-Voltage Bipolar DC Microgrid. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 6494–6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, S.S.; Alharbi, S.S.; Matin, M. An Improved Interleaved DC-DC SEPIC Converter Based on SiC-Cascade Power Devices for Renewable Energy Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Electro/Information Technology (EIT), Rochester, MI, USA, 3–5 May 2018; pp. 0487–0492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, N.; Salehi, S.; Hosseini, S.H. An interleaved structure of sepic converter with lower current ripple. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th Annual Power Electronics, Drives Systems and Technologies Conference (PEDSTC), Tehran, Iran, 13–15 February 2018; pp. 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapparya, V.; Dey, A.; Singh, S.P. A Novel Non-Isolated Boost-Zeta Interleaved DC-DC Converter for Low Voltage Bipolar DC Micro-Grid Application. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 6182–6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siva Alagesan, J.; Gnanavadivel, J.; Senthil Kumar, N.; Krishna Veni, K.S. Design and Simulation of Fuzzybased DC-DC Interleaved Zeta Converter for Photovoltaic Applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), Tirunelveli, India, 11–12 May 2018; pp. 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, O.; Barrero, R.; Van Mierlo, J.; Lataire, P.; Omar, N.; Coosemans, T. An Advanced Power Electronics Interface for Electric Vehicles Applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 5508–5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Ba, Z.; Liu, X. Parameter optimization method for multi-devices parallel of SiC MOSFET. In Proceedings of the CSAA/IET International Conference on Aircraft Utility Systems (AUS 2024), Xi’an, China, 16–19 August 2024; pp. 1982–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrehil El Kattel, M.; Carvalho Lobato, G.I.; Maia, T.A.C.; de Jesus Cardoso Filho, B. 99%—Efficient, interleaved bidirectional DC-DC converter with new interleaved PWM method of parallel-connected Mosfets. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2022, 50, 2439–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, S.; Fantino, R.A.; Gomez, R.A.; Zhao, Y.; Balda, J.C. High Power Density Interleaved ZCS 80-kW Boost Converter for Automotive Applications. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Dong, G.; Mishima, T.; Lai, C.-M. Over 98% Efficiency SiC-MOSFET Based Four-Phase Interleaved Bidirectional DC–DC Converter Featuring Wide-Range Voltage Ratio. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 8436–8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).