Abstract

Precise electricity price forecasts are gaining importance as the economy evolves. For years, researchers have attempted to generate such forecasts using artificial intelligence techniques. Recently, there has been a surge in the application of deep learning methods. This paper aims to identify the latest developments in this field, present the most significant solutions, and highlight existing research gaps. Numerous articles published since 2023 that employ deep learning neural networks for electricity price forecasting are analyzed. In addition to describing individual novel models, the paper provides a summary of error metrics for selected forecasting systems, indicating the markets covered by each study. One of the key conclusions drawn from this review is the limitation in the length of test sets, which in some cases were restricted to only a few days. The review also underscores the rationale for employing hybrid approaches that combine different deep neural network architectures and often incorporate data preprocessing.

1. Introduction

Electricity is undoubtedly a fundamental determinant of the quality of life in modern societies. A key factor influencing both prices and the stability of energy systems is the ability to precisely predict future market situations. Forecasting using artificial intelligence (AI) methods, especially artificial neural networks (ANNs), has been studied for many years. Attempts have long been made to create increasingly advanced and complex systems, characterized by increasingly accurate forecasts.

The pace of change has accelerated noticeably with the advent of ever-faster computers and graphics cards, allowing the modeling of increasingly complex structures, in particular deeply learned ANNs. In recent years, forecasting models combining many elements have become dominant, allowing for increasingly precise forecasts, unfortunately at the cost of the aforementioned increase in complexity. It should be noted that many solutions are complementary in nature; for example, forecasts of electricity production from renewable sources can be used in a model predicting market prices. The paper reviews the latest scientific achievements in the field of broadly understood forecasting prices in the electricity market using deep learning techniques. Due to the complementarity of forecasts and therefore the possibility of creating cascade models, the study was not limited to a narrow area of forecasts, but the topic was treated as broadly as possible.

In recent years, transformers have become more and more widely used. Their beginning is generally considered to be the year 2017 and the publication of the paper “Attention Is All You Need” [1]. Their architecture is based on the attention mechanism and they were originally used primarily in natural language processing (NLP). The origins of the attention mechanism itself date back to 2014 and the publication “Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate” [2]. Transformers, unlike traditional sequential models such as LSTM, operate based on dynamic inductive reasoning. Their attention mechanism enables them to capture latent and complex influencing factors that are not explicitly present in the observed sequence, providing a potential advantage in modeling nonlinear and long-range dependencies in time series data [3]. The development of transformers coincided with the growing popularity of fast graphics cards equipped with efficient graphics processing units (GPUs) capable of parallel data processing [4]. Through the utilization of parallel computation for data processing, transformers—as opposed to typical recurrent networks such as Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM)—perfectly align with the data-processing capabilities of modern GPUs. However, due to the much greater increase in model complexity, in particular the number of parameters, and thus the memory requirements and the number of calculations, the hardware demands and training time may be significantly longer than in the case of recurrent models [5]. Other limitations of this architecture should also be noted, particularly with respect to long-term series forecasting. Acceleration techniques for transformers—such as reducing the computational complexity of the self-attention mechanism—may lead to a loss of critical dependencies when dealing with datasets containing many highly correlated features, ultimately reducing forecasting accuracy [6]. Moreover, research shows that increasing the input window does not improve transformer performance in time series forecasting and may even worsen it. The findings suggest that transformers tend to overfit noise rather than capture long-term temporal patterns when given longer sequences [7].

1.1. Research Gap and Contributions

The dynamic development of forecasting models used in the electricity market requires continuous efforts to identify emerging trends. In most research studies, for obvious reasons, the authors focus on a detailed presentation of their model, without conducting a deeper (or any) analysis of its applicability to other, similar research areas.

Another issue worth exploring in more detail concerns model testing. Although the literature on the subject contains numerous papers on novel models, the testing process often raises doubts. Authors often fail to consider whether the test set is sufficiently large and covers a sufficient time period for the research to be considered reliable. In [8], the authors showed that, given a large amount of data, different error measures tend to indicate the same models as the best, so the choice of a specific error measure has limited significance. In [9] the authors argued that, to reliably demonstrate the competitiveness of the proposed approaches, they should be benchmarked on sufficiently large datasets and compared against appropriate and simple baseline models, such as the naïve and seasonal naïve.

This is particularly important in the electricity market, which is characterized by a high degree of cyclicality (seasonality) [10], often with an element of internal asymmetry [11]. The strong multi-level seasonality inherent in electricity prices necessitates its inclusion in forecasting models [12]. Frequently observed annual cycles require particularly large test sets. This issue warrants special attention, and it also highlights a potential direction for further research into the applicability of the presented models across different markets. An important research gap identified in the recent literature concerns the limited discussion of test set length and its implications for the reliability of forecasting results. Although the structure of electricity prices clearly suggests that sufficiently long evaluation periods are necessary to capture multi-scale seasonal patterns and structural shifts, contemporary studies rarely examine or justify the adequacy of their chosen test horizons. Using overly short test sets may lead to overoptimistic assessments of model performance, as they might fail to include rare events, seasonal extremes, or structural changes in the market. Consequently, conclusions drawn from such limited evaluations could be misleading, reducing the practical reliability and generalizability of the forecasting models.

A broad literature review of forecasting models in the electricity market, encompassing price prediction, allows for a broader perspective on development trends in the energy sector and AI and can serve as inspiration for future research. Such a review helps researchers, based on a synthetic summary, identify the right direction for developing their forecasting models.

1.2. Paper Organization

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology employed for literature selection. Section 3 examines electricity price forecasting using deep learning neural networks. It presents error metrics for individual studies, specifying the country or geographic area covered. The selected key papers are then discussed, highlighting trends in forecasting model development. In selected cases, limitations of the studies and possible directions for future research are identified. Section 4 outlines the principal findings, critically examines the limitations identified in the literature, and highlights the study’s main contributions and research implications.

2. Literature Review Methodology

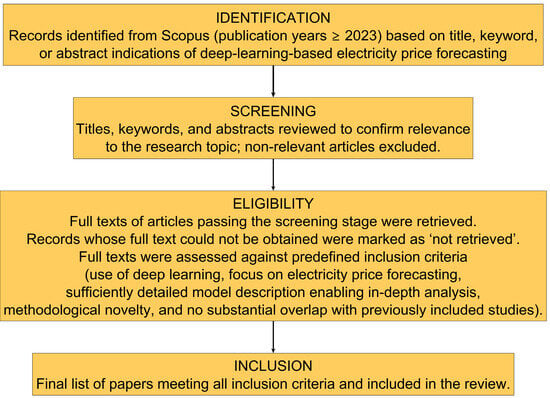

The literature review included selected publications from 2023 to 2025 on electricity price forecasting using deep learning. References to earlier literature were made only in justified cases. The review covers publications available until the end of September 2025. One paper has already been released with an official publication date of 2026. The papers identified by the Scopus database were subjected to a selection process. Figure 1 illustrates the subsequent stages of selecting papers included in the review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram presenting the identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion of studies considered in this review.

The papers were subjected to detailed analysis without any automation, particularly without the use of AI tools. A small number of publications whose models were highly consistent with previously reported studies were not included in this paper. This does not imply that these articles fail to meet academic standards; rather, the issues they address have already been extensively covered by other sources. Section 3 presents the error metrics provided by the authors of the analyzed papers. In one case, kWh was converted to MWh. Only the error metrics defined in Section 3.1 were included in the comparison. In selected cases, MSE values were converted to RMSE to express them in the same units as electricity prices, enabling a broader comparison of values across multiple studies. Since the error metrics cover different markets and time frames—often significantly different in length—they cannot be directly compared. However, they provide a valuable resource for readers (especially researchers) who wish to compare their deep learning models with previously conducted studies. The remainder of Section 3 describes the publications included in the review, with particular emphasis on aspects that are novel or significantly different from previously known approaches. The descriptions are also critical, indicating areas where further research is still needed or possible.

3. Results

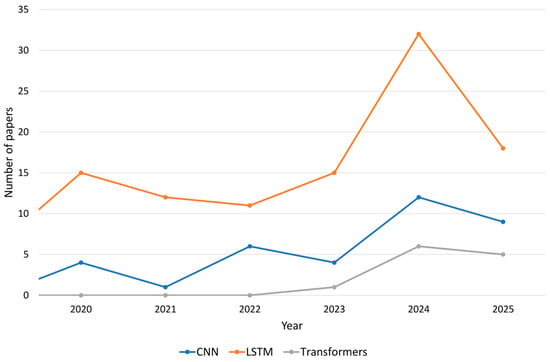

Recent years have seen a significant increase in the use of deep learning for forecasting electricity markets. These models are increasingly replacing “traditional” ANNs, now often referred to as shallow neural networks [13]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), LSTMs, and their hybrids (e.g., CNN-LSTMs) have become particularly popular. Despite some fluctuations, a clear upward trend is evident across all categories.

Figure 2 shows the number of papers indexed in the Scopus database whose titles or keywords indicate a focus on electricity price forecasting using deep neural networks. The results were divided into three subcategories: LSTMs, CNNs, and transformers. An increase in the number of papers across all categories has been observed in recent years. The observed decline in the number of publications across all categories in 2025 is most likely due to incomplete data.

Figure 2.

Number of publications in the Scopus database in the area of electricity price and demand forecasting in which selected deep learning models were used.

To obtain the number of publications involving studies using LSTM, the following query was used: (((TITLE(“long short-term memory”) OR TITLE(“LSTM”) OR KEY(“long short-term memory”) OR KEY(“LSTM”)) AND (TITLE(“electricity”) OR KEY(“electricity”)) AND (TITLE(“price”) OR TITLE(“pricing”) OR KEY(“price”) OR KEY(“pricing”)) AND (TITLE(“forecast”) OR TITLE(“prediction”) OR TITLE(“estimation”) OR KEY(“forecast”) OR KEY(“prediction”) OR KEY(“estimation”)) AND NOT ((TITLE(“demand”) OR KEY(“demand”)) AND NOT (TITLE(“price”) OR TITLE(“pricing”) OR KEY(“price”) OR KEY(“pricing”))) AND NOT TITLE(“load”)))”. The same approach was applied to the other two subcategories.

3.1. Error Metrics

Table 1 provides an overview of the key error metrics employed in the studies reviewed in this paper. It should be noted that in certain cases, particularly in probabilistic forecasting, the use of error metrics may not be feasible. In [14], the Continuous Ranked Probability Score was used to evaluate the performance of models (including LSTM). This metric allows for the evaluation of the entire distribution forecast. Given the clear predominance of point forecasts in this paper, the main emphasis was placed on commonly used error metrics.

Table 1.

Selected error metrics.

Table 2 presents a summary of error metric values reported in selected studies employing deep learning techniques. The test datasets—depending on the study—covered different time periods. Consequently, the reported values cannot be directly compared across studies. Nevertheless, they provide researchers with a general point of reference, indicating the extent to which their models can be considered competitive relative to existing approaches.

Table 2.

Summary of error metrics reported in selected studies on electricity price forecasting using DNNs.

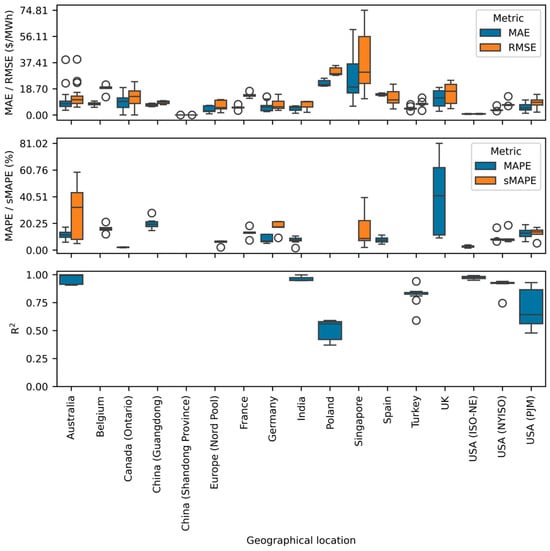

Differences in error metrics arise from multiple factors. Higher values are often observed in markets with high volatility or strong cross-border connections [51]. Figure 3 presents a boxplot of the energy markets included in Table 2. It illustrates several of the most commonly used error metrics: MAE, RMSE, MAPE, sMAPE, and the coefficient of determination (R2). To improve data comparability, the first two metrics are expressed in $/MWh. If the authors of the analyzed publications used a different currency, the conversion to US dollars was based on the exchange rates published by the International Monetary Fund on 20 November 2025.

Figure 3.

Boxplots of forecast error measures by electricity market.

Forecast quality varies significantly across markets. It should be noted, however, that this variation may partly result from the models applied in each market. For ISO-NE in the USA, forecast errors are noticeably lower than for PJM. A significant divergence in forecast quality was noted in the Singapore market. Nord Pool was characterized by relatively low error metric values and a narrow spread. Among the European Union markets covered in the study, the least accurate forecasts were observed in the Polish market. In the case of China, significant differences in error metric values were observed depending on the analyzed market.

3.2. Deep Learning Architectures in Electricity Market Forecasts

Currently, many relatively simple deep learning models are successfully applied to forecast electricity prices. In [23], LSTM and CNN were employed to forecast spot electricity prices in the Spanish market. The previously mentioned networks demonstrated the ability to forecast both upward and downward movements in energy prices [52]. Even for less complex architectures, performance can be optimized through the use of a filtering strategy. Ref. [53] reported that forecast accuracy improved by up to 4%. The research was conducted across five electricity markets: Nord Pool, PJM, and the day-ahead markets in Belgium, France, and Germany. Among the models tested, one of the simplest DNNs was used, containing four layers. The tree Parzen estimator was employed for hyperparameter selection. Unfortunately, the study did not include more complex architectures, whose use could serve as a basis for further research in this area.

A novel algorithm combining the Day Similarity Algorithm (DSA) with an Embedded Feature Selection (EFS) method based on Extreme Gradient Boosting, hyperparameter tuning via the Adaptive Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (ATPE), and a Deeply Learned Multi-Layer Perceptron (DLMLP) was presented in [46]. The authors conducted comparative tests on several models built with the aforementioned algorithms, including DSA-EFS-ATPE-DLMLP, DSA-EFS-DLMLP, DSA-ATPE-DLMLP, DSA-DLMLP, and DLMLP. The forecasts generated by the first of these models achieved the lowest error metric values.

In [47], the DLMLP was employed with a parallel linear layer. The authors introduced three versions of the linear block. Despite its simplicity, the model proved to be relatively effective. The version called MLP-NLinear was more accurate than the comparative LSTM network and, for data from one of the three tested power plants, outperformed all models tested in the study, including the transformer. The authors used a test set of a reasonable length—one year—which positively contributes to the reliability of the results obtained.

The predictive capabilities of LSTM were also confirmed in [54], where it outperformed other (not deeply trained) models in medium-term forecasting. Several variants of the network with one, two, or three hidden layers were tested. The considerable variation in error rates depending on the length of the test period is noteworthy. This highlights the importance of verifying forecasting models using sufficiently long test sets.

In [55], an LSTM was employed for intraday forecasting. The network contained two hidden layers, and hyperparameter tuning was carried out using Random Search (RS) and Bayesian optimization methods. The basic LSTM architecture presented proved more accurate than CNN and significantly outperformed models not based on deep learning.

In [49], the CNN-LSTM architecture using smoothed data was employed to analyze prices in the Indian electricity market. The Exponential Smoothing-CNN-LSTM model achieved a noticeably higher R2 and lower error rates compared to the baseline LSTM and CNN-LSTM models. For testing purposes, 14,016 samples representing prices at 15 min intervals were utilized. This corresponds to 146 days of market quotations.

Analyzing the data in Table 2 and the content of the papers included in this review, it should be noted that the most complex ANNs do not always achieve the best results. In [56], among the thirty machine learning models tested, only one LSTM network ranked among the top ten with the lowest error metrics. Even the shallow MLP network performed significantly better. Furthermore, given the similar precision of the forecasts, the choice of the best model depends largely on the error metric applied. For example, in [25] relatively simple GRU networks achieved a higher R2 (0.983) than a much more complex CNN-LSTM architecture (R2 = 0.955). GRU combined with the multi-head (MH) self-attention mechanism (called ATTnet) was employed in [57] and demonstrated noticeably lower error metrics than comparative models. This is not an isolated case and such examples could be multiplied.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) based GRU and LSTM models were employed in [48] to predict prices on the Indian Energy Exchange. PSO is regarded as an effective global optimization algorithm, significantly simpler in operation than evolutionary algorithms, primarily because it avoids genetic operations [58]. Moreover, PSO can prevent falling convergence into the best local solution during model training [48]. The model combining day-ahead with similar day and PSO-based GRU achieved the lowest MAPE. The authors used data from May 1 to August 30, 2018, splitting it into training and validation sets in a 70:30 ratio. A 15 min data interval resulted in 11,712 samples. Therefore, the models were tested on approximately 3514 samples (or a similar value, depending on rounding), representing about 37 days. Although the number of samples is quite high due to the four hourly readings mentioned above, the research covered only a small portion of the year. This is not a criticism of the research; however, it suggests that further analyses would be advisable in this market, using the proposed model to assess its performance under different conditions (e.g., other months of the year).

GRU and LSTM networks were also successfully employed to model regulation capacity prices using data from the Independent System Operator New England (ISO-NE) in [59]. The error metrics varied by season, with the lowest values in summer (GRU) and the highest in winter. For three seasons (spring, summer, and fall), the MAPE for GRU was lower than that for LSTM. In winter, this relationship was reversed. This suggests that, depending on the market situation, different models may prove effective for modeling electricity prices. This underscores the importance of selecting the appropriate type of network for a given problem. The fact that a network is more complex and has potentially higher predictive capabilities does not necessarily translate into better results. Nevertheless, there is a clear tendency toward the dominance of hybrid models that are appropriately designed and adapted to a given market. The aforementioned term “hybridity” is rather imprecise. Originally, most models combining components from more than one type of network were described as hybrid solutions. Even CNN-LSTM networks with typical architecture were referred to as such [60], as were CNN-GRU networks in [31]. Currently, the term “hybridity” increasingly refers to the use of innovative or less typical elements within a given architecture.

Hybrid models based on deep neural networks can be categorized according to the level of component integration, as presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Categories of hybrid models.

Many models are, in practice, multi-level hybrids that simultaneously combine different neural architectures with data-level hybridization strategies and optimization algorithms, as exemplified by Wavelet Packet Decomposition (WPD)-TCN-LSTM, Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD)-TCN-LSTM, Fourier-TCN-LSTM, Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (CEEMDAN)-TCN-LSTM, RS-CNN-BiLSTM-Autoregressive (AR).

In [25], the authors proposed a three-stage model in which feature selection was applied between data preprocessing and the actual prediction performed by a DNN, using a method that combines the Marine Predators Algorithm (MPA) with Random Forest (RF). As indicated, identifying the most influential features resulted in an 84% increase in model accuracy.

The hybrid approach presented in [61] was based on an initial decomposition of the time series and the subsequent application of the Extreme Learning Machine (ELM), LSTM, and RF. Compared to the LSTM model, this hybrid approach achieved lower forecasting errors. The Australian and Singaporean markets were studied. The test set in both cases comprised 288 samples. The accuracy depended on the number of prediction steps, ranging from 1 to 3. The MAPE reduction relative to the LSTM model varied between 25% and 35%.

In 2024, a study conducted in [62] presented results obtained using a deep learning-based model known as Deepforkit. The model was developed to predict day-ahead prices in the European market, which experienced unique dynamics due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the global energy crisis. The authors did not disclose the details of its architecture.

An example of the effective application of the CNN-LSTM architecture for electricity price forecasting is provided in [63]. Numerous network variants were tested, utilizing diverse input data, including actual power generation, holidays, meteorological data, rolling and cyclical features, and system price. The model with the full set of explanatory variables achieved the highest operational precision. The study compared two approaches: (i) a fixed split into training and test sets, and (ii) successively expanding the training set and iteratively using only the next day as test data. Approach (ii) yielded a higher R2 value (0.787 vs. 0.750).

In [38], a hybrid model employing the CNN-BiLSTM-AR architecture was introduced. A significant reduction in error metrics was observed compared to the comparative models: CNN-LSTM, CNN-BiLSTM, and CNN-LSTM-AR. Relative to the commonly used CNN-LSTM, the MAE decreased by more than 7.88% and the RMSE by more than 8.41%. The authors did not explicitly specify the size of the test set but indicated that data from 2021 was used. Given that the paper was published in March 2023, it can be assumed that the study relied on data from 2021 or, at most, a two-year period. As indicated, the test set constituted 20% of the dataset, which, in the second variant, corresponds to approximately five months of data. This raises the question of how the model would perform in the remaining months. Annual cycles are often observed in electricity markets; therefore, it seems advisable to evaluate the model performance over a longer timeframe in future research. Nevertheless, the proposed model appears promising and undoubtedly represents a valuable contribution to the field and a solid foundation for further studies.

The hybrid CNN-LSTM model in [32] was extended by incorporating a parallel AR unit. As the authors aptly note, in electricity markets, price fluctuations are continuous and irregular, which significantly reduces the predictive accuracy of ANN models. The proposed approach including the AR unit was combined with hyperparameter optimization using RS, Genetic Algorithm and PSO. The performance of the introduced hybrid model was evaluated in two markets: the UK and Germany. The lowest error metrics were achieved by the model optimized using PSO.

In [28], a Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN)-LSTM hybrid network was integrated with wavelet packet decomposition. The authors used data spanning from January 2015 to January 2019. The test set comprised 5% of the dataset, which corresponds to less than 2.5 months. Therefore, it would also be worthwhile to assess the model’s performance on a larger test set. Compared to the TCN-LSTM model, the proposed approach led to a significant reduction in forecast errors: MAE by nearly 59%, RMSE by more than 56%, and MAPE by more than 17%.

TCN combined with Network Base Expansion Analysis for Interpretable Time Series Forecasting (N-BEATS), operating on data decomposed into trend, seasonal, and residual components using the STL method (introduced in 1990 in [64]) was applied in [24] to forecast prices in the Spanish market. The model demonstrated a significant improvement in forecasting accuracy compared to other tested DL models. The authors used data from 2015 to 2018. Ten percent of the dataset—corresponding to approximately 4.8 months—was allocated for model verification.

In [65], a hybrid model comprising parallel LSTM and Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (SARIMA) units was introduced. After decomposing the original time series into sub-frequency components using the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), the D1 and D2 series (i.e., higher-frequency components) were processed with SARIMA, while D3 and A3 were fed into the LSTM model. Four weekly intervals—one for each season (February, May, August, and October)—were used for testing on the PJM market.

The combination of Maximum overlap Discrete Wavelet Transform (MoDWT) with a hybrid CNN-Random Vector Functional Link (RVFL) model was introduced in [39]. The authors calculated error metrics separately for each season (summer, autumn, winter, and spring) as well as for the entire year 2022. For the latter, the R2 value was exceptionally high, reaching 0.999. For the remaining periods, it was also high and amounted to a minimum of 0.998. The proposed model exhibited higher forecasting accuracy than the tested MoDWT-LSTM model, as well as most models using VMD and the Error-Compensated Random Forest presented in [40]. In the study, 26 wavelets of different types were tested, including: Daubechies, Symlet, Fejer-Korovkin, discrete approximation of Meyer wavelet, and Coiflet. The number of tested wavelets indicates the high robustness of the research; however, it may be worthwhile to test other wavelet families (e.g., biorthogonal) in future studies. Their effectiveness in financial time series analysis has been repeatedly demonstrated and documented in the literature [66,67] (which, of course, does not imply that their application would necessarily improve the performance of the proposed hybrid model).

Multi-scale decomposition based on wavelet and empirical mode decomposition was integrated with a modified deep Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GCNN) for price and demand forecasting [42]. Price forecasting models were evaluated in the New South Wales market (a region of the Australian Energy Market Operator) and the Singapore electricity market. The study demonstrated not only the effectiveness of the GCNN but also the strong dependence of the final results on the chosen architecture. Analysis of the data in Table 2 reveals substantial differences in MAPE values. The basic LSTM model produced errors of 51.946% and 27.93% for the New South Wales and Singaporean markets, respectively, whereas the best-performing model achieved errors of 4.937% and 2.009%.

A Spatial-Temporal Graph Neural Network (STGNN) was applied in [68] to perform out-of-sample predictions on a two-year test set. To ensure that the forecasting model was trained and evaluated on the most recent and relevant data, the authors implemented a sliding time window approach. Each window was divided into three distinct segments: training, validation, and test. The lengths of these segments were fixed across all windows. Specifically, the training and validation sets spanned 166 weeks and 42 weeks, respectively, while the test set covered one week. After each forecasting iteration, the window was shifted forward by one week, ensuring that the entire out-of-sample period was covered without overlap in the testing outputs. The authors presented several versions of the model based on area grouping.

In the hybrid model called the Heteroscedastic TCN (HeTCN), introduced in [36], a TCN served as the encoder, while a simple Deep Neural Network (DNN)—composed of dense layers—functioned as the decoder. The output of the forecasted standard deviation, along with a maximum likelihood estimation-based loss function, was used as the optimization objective during model training. The forecast encompassed, as in [53], five markets: Nord Pool, PJM, and the European Power Exchange (EPEX) Spot Market in Belgium, France, and Germany. In all cases, the test set included hourly data spanning nearly two years, which enhances the reliability of the reported results.

Numerous hybrid models were evaluated in [44]. The proposed innovative CNN- Stacked Sparse Denoising Auto-Encoder (SSDAE) hybrid model was enriched with the Improved Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (ICEEMDAN) method. The ICEEMDAN approach was employed to decompose the original input feature matrices into components, facilitating the extraction of meaningful informational features. “Conventional” deep learning networks, i.e., CNN, LSTM, and GRU, were used as comparative models, along with several hybrid approaches, including CNN-LSTM, CNN-GRU, CNN-SSDAE, WT-CNN-SSDAE, SSA-CNN-SSDAE, and EEMD-CNN-SSDAE. Comparative analysis revealed a clear advantage of the ICEEMDAN-CNN-SSDAE method proposed by the authors. Tests covered four periods: spring, summer, autumn, and winter. However, these represented only three-day intervals rather than full seasons. A five-year dataset was used for training networks. This training set undoubtedly allows the model to capture cyclical dependencies even with a one-year period. Unfortunately, the test set does not allow for a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance. The tests conducted show that the proposed approach is highly promising. Further research on this model would be worthwhile, particularly given its unprecedented advantages over other hybrid approaches widely regarded as highly accurate in predictive analysis. In addition to expanding the test set, it would be advisable to evaluate the performance of the proposed model in other markets, with potential parameter optimization (a typical step when adapting a model to different market conditions).

The ICEEMDAN approach was also used in [69]. The authors created a combination model of electricity price bi-forecasting based on a Multiobjective Golden Eagle Optimizer (MOGEO). Two variants were presented: MOGEO-DBN (which employed a unidirectional network and an unsupervised learning algorithm based on a restricted Boltzmann machine) and MODEO-BiLSTM. The authors compared the prediction results for both other forecasting models (including deep learning models—GRU and BiLSTM) and for various data preprocessing methods. The study used data with a half-hourly interval. Of the 1488 samples, 298 were allocated to the test set, representing only approximately 6.2 days of data.

A new hybrid model was introduced in [37]. It relies on data decomposition using CEEMDAN and VMD, and on Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN), introduced in 2024. Additionally, the model was augmented with two parallel data processing branches preceding KAN. One branch employed BiGRU and a self-attention mechanism, and the other incorporated the residual network module containing two parallel convolutional paths and a channel attention module. The authors’ meticulous attention to detail, particularly during the model testing phase, is noteworthy. The study encompassed five electricity markets: Nord Pool, PJM, as well as markets in Belgium, France, and Germany. The test set comprised two years of data for the first two markets and one year for remaining three.

An attention-based LSTM with VMD and hyperparameter optimization using the Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) algorithm was applied in [70] to forecast prices in markets considering renewable energy. Data from the Singapore market were analyzed, and predictions were made only for the days between December 29 and 31. It would be advisable to extend this time horizon in future studies, as this would enhance the reliability of the results. An alternative approach involving an attention mechanism in a BiLSTM network was introduced in [27]. Data decomposition was performed using Ensemble EMD—a noise-assisted variant of EMD introduced in [71]. A Bayesian optimization algorithm based on an RF regressor was employed for hyperparameter tuning.

Another complex hybrid forecasting model was introduced in [43]. In the first step, a detection–isolation mechanism based on the Local Outlier Factor was implemented. Next, the signal was decomposed using VMD. Finally, non-crossing quantile regression was performed using a Skip Connection Recurrent Neural Network (SCRNN) architecture built upon BiGRU units. By combining a symmetric approach and skip-connection architecture, the method improved forecasting accuracy and reduced uncertainty in the quantized price prediction ranges.

The hybrid model described in [35], which employs CNN, also incorporates the attention mechanism, specifically MH self-attention. The authors’ approach to feature selection is noteworthy: it is based on an ANN, and through iterative model building, features with low impact can be identified and removed. The limited data volume raises some concerns. The authors used data from four months, each representing a different season. The models were trained on data from the first three weeks of each month, while the fourth week was used for testing. The presented research appears highly promising and certainly deserves to be continued. In the next stage, it would be reasonable to evaluate the model’s performance on data spanning several years. It would also be valuable to assess how the model performs when trained on data from a given season in one year and tested on data from the corresponding season in the following year. This consideration is important because, in practical business applications, the question arises as to which data the model should be trained on at the beginning of a new season—data from a different season (which seems problematic) or data from the same season in a previous year.

Ref. [45] presents the Recurrent Deep Random Vector Functional Link Network (RDRVFLN), an extension of the shallow neural network by incorporating deep learning elements. Its performance was evaluated on data from PJM and New South Wales (Australia). The dataset covered the period from January to December 2020 for PJM and from January to December 2019 for New South Wales. Forecasts for four months—February, April, July, and October—were used to calculate error metrics and compare model performance. The best results were achieved with the model augmented by Successive Variational Mode Decomposition (SVMD).

An interesting and promising approach to medium- and long-term forecasts (one week and two months, respectively) is introduced in [72]. The authors propose a model that employs a recurrent neural network to decompose the input time series into trend, periodic, and residual components. Another recurrent network is then used to forecast electricity prices. A significant departure from the typical decomposition-based approach is that the model optimizes a joint objective function for both time-series decomposition and forecasting. The paper also indicates that the proposed approach offers considerable flexibility in selecting a forecasting model. For example, in addition to LSTM and GRU, a sequence-to-sequence architecture can be used; in the presented example, three such models were applied—one for each component.

Cascade models have also been discussed in the literature. In [73], electricity price forecasting was preceded by the prediction of several key determinants, which the authors identified as aggregated solar and wind generation, demand forecasts, and derivative market prices. Wind generation was predicted using a DL-MLP model, while solar generation was predicted with a CNN, as described in [74]. The final electricity price forecasting model was built upon a DL-MLP architecture.

Hybrid models based on transformers are becoming more common. It is worth noting that, while they are computationally complex, they can leverage GPU parallelism to a relatively high degree. In an era of increasingly faster graphics cards, this foreshadows the growing popularity of transformers in the coming years. In recent years, both transformers and hybrid models combining transformers with various combinations of DNN layers have emerged. In [75], the authors applied transformers to forecast the Spot Market Electricity Price for one year in Växjö (Sweden), obtaining results significantly better than the benchmark model, i.e., Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA). No comparisons with other ANNs were provided. The model’s precision was significantly improved (an increase in R2 for the entire year from 0.5639 to 0.8409) by integrating transformers with the Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process. In [13], transformers were used in combination with CNN-GRU.

The Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT)—a hybrid transformer model consisting of LSTM units, Gated Residual Networks (GRNs), and a MH attention mechanism—introduced in [76], was employed in [77] to develop a model for forecasting extreme electricity prices. The authors compared the results with those obtained using baseline models such as the Autoencoder-LSTM and the Patch Time Series Transformer (PatchTST). One of the proposed approaches demonstrated significantly lower error metrics, with RMSE reduced from 49 and 42 to approximately 38, respectively.

There is a growing adoption of attention mechanisms in diverse areas of predictive analytics. In [31] the authors used the classic soft attention mechanism in the CNN-GRU hybrid model. Although the paper does not provide a direct comparison of the results of the same models using the attention mechanism and without it, the content of the paper suggests that the models incorporating the attention mechanism were characterized by higher forecasting accuracy.

In [50] the authors demonstrated that a transformer encoder–decoder with self-attention has the potential to produce significantly more accurate predictions than most other deep learning models. Comparative models included numerous network architectures based on (Bi)GRU, (Bi)LSTM, and a CNN-LSTM model. The advantage of the presented model was evident: R2 reached 0.94, whereas the best comparative model achieved 0.85 (Table 2). The research was based on a relatively large dataset divided into two parts: (i) from 1 January 2017 to 12 March 2020, and (ii) from 1 July 2021 to 31 December 2021. In total, the data comprised 32,423 hourly samples, i.e., over 1350 days. Ten percent of the data was allocated to the test set. The research included forecasts covering the COVID-19 pandemic and the “normal” period. Given the size of the dataset and the number of comparative models, the results should be considered highly reliable.

An interesting approach related to transfer learning was introduced in [78]. The authors highlighted the possibility of applying models (inter alia DNN) pre-trained on markets other than the target one by using a fine-tuning mechanism. This is a very promising approach, especially nowadays, when numerous factors—such as the war—cause significant changes in the functioning of many markets. In such circumstances, the use of historical data for model training may prove insufficient. The possibility of employing pre-trained models from other markets provides much broader opportunities for developing forecasting models.

Another issue concerns the test sets used to verify the accuracy of the models. In some cases, they were relatively short. For example, in [34], these were three weekly subsets. This raises some concerns about the model’s performance in other time frames. The authors have undoubtedly proposed a very interesting forecasting model with great potential, but it seems advisable to examine both the model’s performance over longer time frames and its transferability and adaptability to other electricity markets in further research. An example of paper covering a much longer time series is [29]. The authors used data from 2016 to 2024. A test set was created from 15% of this data. It covered approximately 16 months. Therefore, it was possible to capture cyclical dependencies with a period of one year. The authors suggested that this may be related to increased variability of input variables. Further research to explain the reason for this state of affairs has not been conducted (which is not a criticism, as it is likely due to space limitations in the article). It seems worthwhile to investigate the causes of the significantly lower quality of forecasts for the summer period (RMSE equals to 200.64 PLN/MWh vs. 94.39 PLN/MWh in spring).

3.3. Input Variables

Table 4 presents a summary of the input variables used in the forecasting models. Given that lagged electricity prices are commonly included in nearly all models, they were excluded from the overview.

Table 4.

Overview of input variable types (excluding lagged and real-time electricity prices) employed in forecasting models across the studies reviewed.

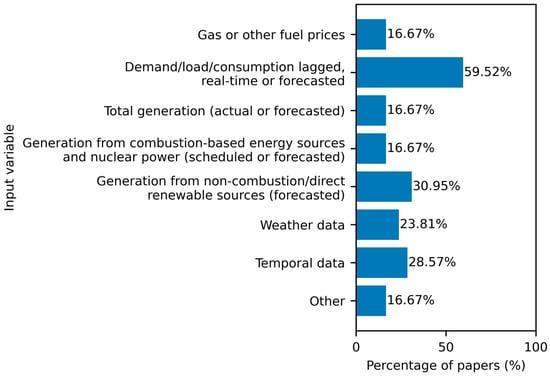

Figure 4 provides an overview of the percentage share of studies employing each input variable. In recent years, the use of increasingly complex feature sets has become more common. Lagged, real-time, or forecasted demand/load is by far the most commonly used input variable, appearing in over 60% of the reviewed studies. Weather data and temporal data appear with moderate frequency, which is somewhat surprising given the central role of weather in shaping electricity demand and the common use of temporal features as indirect representations of weather-driven effects.

Figure 4.

Percentage usage of model input variables across reviewed papers.

4. Discussion

Many papers demonstrate relatively short test sets used to evaluate the proposed model. The limited test horizon may not fully capture seasonal variations in electricity prices. Future research should consider a longer or seasonally representative test period to improve the robustness of performance evaluation. It is important to note that the length should depend on the nature of the market. In the case of the energy market, one year should be regarded as the minimum period to reliably assess model performance.

Many factors influence the choice of test set length. These include the seasonality/cyclicality of a given market and its stability. Market behavior varies, especially in times of dynamic changes caused by various factors, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent war in Ukraine. Therefore, it is reasonable to ask how well the presented models will adapt to changes in market behavior driven by these factors. Further research in this area would be advisable. It should be emphasized that choosing a test interval that is too long also carries certain risks. A model trained on data too distant from its initial use may perform with reduced precision, failing to account for market changes. Periodic retraining (either through fine tuning or from scratch) would be advisable. The frequency of these activities also cannot be clearly defined and should be a function of many factors. Even the use of a large dataset does not guarantee that it represents a sufficient variety of forecasting scenarios [79].

Deep learning enables the use of increasingly complex feature sets. It can be expected that, in the future, models will employ even more sophisticated explanatory variables. A practical challenge relates also to the availability and quality of input variables. Some relevant data are not publicly accessible because they are controlled by market participants (often competitors) [80]. Complex feature sets, particularly those incorporating detailed meteorological data, may be difficult to obtain with sufficient spatial and temporal resolution. Moreover, weather forecasts are inherently local, whereas market-clearing prices typically represent much larger geographical areas. As a result, the weather conditions observed or forecast for a specific location may not be representative of the entire region influencing price formation, potentially introducing additional noise or bias into the modeling process. Many studies have emphasized the importance of carefully selecting these features to exclude those whose contribution to model performance is negligible. Methods designed for this purpose are likely to become an important area of future research.

Electricity price forecasting models are not only theoretical constructs but must be applicable in real-world decision-making contexts. To ensure practical relevance, forecasting systems should also account for market-specific characteristics, and regulatory frameworks. Recent studies highlight the growing role of AI and digital transformation in enhancing the resilience and adaptability of energy markets. For instance, ref. [81] demonstrated how advanced machine learning techniques can be employed to predict economic resilience indices in the Chinese energy sector, leveraging large-scale economic and operational data. Their findings underscore that integrating AI-driven optimization with domain-specific knowledge enables more accurate and robust predictions, which can support strategic planning and operational efficiency in dynamic electricity markets. Incorporating such approaches into price forecasting frameworks can bridge the gap between theoretical modeling and practical implementation, improving decision-making under uncertainty.

Although deep learning models achieve remarkable performance, their opaque, black-box nature often undermines trust in their decision-making processes [82]. In critical fields the need for domain experts and end-users to understand the reasoning behind model decisions remains essential, which continues to constrain the widespread adoption of deep learning models [83]. Interpretability and explainability aim to provide clarity and insight into a model’s inner workings, enabling users to understand both the mechanisms and the reasons behind the outcomes it generates [7]. The field of explainable AI (XAI) offers a range of techniques to improve model transparency. Popular methods such as Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP), Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME), and Class Activation Mapping (CAM) can often be applied to interpret complex models across diverse domains [84]. Future research should focus on advancing this area so that knowledge derived from increasingly complex forecasting models can have broader practical applications.

In practical electricity price forecasting systems, different deep learning architectures such as CNN, LSTM, and GRU are rarely applied in isolation. Instead, they are often integrated within a unified modeling framework to exploit their complementary strengths. CNN-based components can be used for automatic extraction of short-term patterns and local structures in the input data, while recurrent architectures such as LSTM or GRU capture temporal dependencies and longer-term dynamics. These models may be trained in parallel on the same dataset and combined using ensemble strategies (e.g., averaging, stacking, or weighted voting), or incorporated into hybrid architectures where convolutional layers often feed into recurrent layers.

Such integration offers improved robustness and predictive performance but also introduces several challenges. The computational cost increases substantially when multiple models are trained simultaneously, and careful coordination of hyperparameters is required to avoid overfitting. Additionally, selecting the optimal combination of models for operational deployment necessitates systematic benchmarking and sensitivity analysis.

The trend toward creating hybrid models, observed in recent years, appears to represent the right direction for the development of ANNs. Using multiple techniques in a single forecasting model allows for the leveraging of each technique’s advantages. This trend is reflected in the increasing use of transformers in research. We are witnessing the development of increasingly sophisticated models. This trend will likely continue (although perhaps at a varying pace). In most applications, complex forecasting models appear to outperform both “standard” ANNs and “traditional” models in terms of forecasting accuracy.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used for the research described in the article.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the use of ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, 2025) during the preparation of this manuscript for the purposes of linguistic improvement. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication. No AI model was used to substantively analyze the papers referenced in this review or to prepare the summaries and conclusions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| AR | Autoregressive |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| AT | Attention based |

| Bi | Bidirectional |

| CAM | Class Activation Mapping |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CORR | Correlation |

| DLMLP | Deeply Learnt Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| ECRF | Error-Compensated Random Forest |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| EMD | Empirical Mode Decomposition |

| EPEX | European Power Exchange |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Units |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| GWO | Grey Wolf Optimization |

| ICEEMDAN | Improved Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise |

| ISO-NE | Independent System Operator New England |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MH | Multi-Head |

| MI | Mutual Information |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MoDWT | Maximum overlap Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| MPA | Marine Predators Algorithm |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| N-BEATS | Network Base Expansion Analysis for Interpretable Time Series Forecasting |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| PatchTST | Patch Time Series Transformer |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| RS | Random Search |

| RVFL | Random Vector Functional Link |

| SA | Seasonal Attention-based |

| SARIMA | Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| SSA | Singular Spectrum Analysis |

| SSDAE | Stacked Sparse Denoising Auto-Encoder |

| STGNN | Spatial-Temporal Graph Neural Network |

| SVMD | Successive Variational Mode Decomposition |

| TCN | Temporal Convolutional Network |

| VMD | Variational Mode Decomposition |

| WD | Wavelet Decomposition |

| WPD | Wavelet Packet Decomposition |

| WT | Wavelet Transform |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2023, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yuan, Y. Stock Price Forecast: Comparison of LSTM, HMM, and Transformer. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Academic Conference on Blockchain, Information Technology and Smart Finance (ICBIS 2023), Hangzhou, China, 17–19 February 2023; pp. 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Comparative analysis and prospect of RNN and Transformer. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 75, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashru, P.D. Comparative Analysis of CNN, RNN, LSTM, and Transformer Architectures in Deep Learning. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 2023, 29, 5439–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Zuo, X.; Li, R.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Huang, B. A systematic review for transformer-based long-term series forecasting. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Lee, D.; Yoon, S. A comprehensive survey of deep learning for time series forecasting: Architectural diversity and open challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsandreas, D.; Spiliotis, E.; Petropoulos, F.; Assimakopoulos, V. On the selection of forecasting accuracy measures. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2022, 73, 937–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewamalage, H.; Ackermann, K.; Bergmeir, C. Forecast evaluation for data scientists: Common pitfalls and best practices. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2023, 37, 788–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, V.; Gama, J. Prediction intervals for electric load forecast: Evaluation for different profiles. In Proceedings of the 2015 18th International Conference on Intelligent System Application to Power Systems (ISAP), Porto, Portugal, 11–16 September 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, T. A new approach to modeling cycles with summer and winter demand peaks as input variables for deep neural networks. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Ramentol, E.; Schirra, F.; Michaeli, H. Short- and long-term forecasting of electricity prices using embedding of calendar information in neural networks. J. Commod. Mark. 2022, 28, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedram, O.; Soares, A.; Moura, P. A Review of Methodologies for Photovoltaic Energy Generation Forecasting in the Building Sector. Energies 2025, 18, 5007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agakishiev, I.; Härdle, W.K.; Kopa, M.; Kozmik, K.; Petukhina, A. Multivariate probabilistic forecasting of electricity prices with trading applications. Energy Econ. 2025, 141, 108008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.; Matsuura, K. Advantages of the mean absolute error (MAE) over the root mean square error (RMSE) in assessing average model performance. Clim. Res. 2005, 30, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, M.Z.; Alavi, A.H. Error Metrics and Performance Fitness Indicators for Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Engineering and Sciences. Archit. Struct. Constr. 2023, 3, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, T.O. Root-mean-square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): When to use them or not. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 5481–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Collopy, F. Error measures for generalizing about forecasting methods: Empirical comparisons. Int. J. Forecast. 1992, 8, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buturac, G. Measurement of Economic Forecast Accuracy: A Systematic Overview of the Empirical Literature. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koponen, P.; Ikäheimo, J.; Koskela, J.; Brester, C.; Niska, H. Assessing and Comparing Short Term Load Forecasting Performance. Energies 2020, 13, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, Y. Assessing Forecast Accuracy Measures. Preprint 2004, 2010, 2004-10. [Google Scholar]

- Kva Lseth, T.O. Note on the R2 measure of goodness of fit for nonlinear models. Bull. Psychon. Soc. 1983, 21, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failing, J.M.; Segarra-Tamarit, J.; Cardo-Miota, J.; Beltran, H. Deep learning-based prediction models for spot electricity market prices in the Spanish market. Math. Comput. Simul. 2026, 240, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Song, C.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y. Electricity price forecast based on the STL-TCN-NBEATS model. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, A.; Rami, A. Enhanced electricity price forecasting in smart grids using an optimized hybrid convolutional Multi-Layer Perceptron deep network with Marine Predators Algorithm for feature selection. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2025, 20, 2456058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.A.; Ullah, M.H.; Tabassum, R.; Kabir, M.F. Enhanced Transformer-BiLSTM Deep Learning Framework for Day-Ahead Energy Price Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025; 1–15, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, W.; Wang, F.-K.; Amogne, Z.E. Electricity Load and Price Forecasting Using a Hybrid Method Based Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory with Attention Mechanism Model. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023, 2023, 3815063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Q.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Zeng, D.; Liu, D. Forecasting electricity prices in the spot market utilizing wavelet packet decomposition integrated with a hybrid deep neural network. Global Energy Interconnect. 2025, 8, 874–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowiński, R.; Komorowska, A. Forecasting electricity prices in the Polish Day-Ahead Market using machine learning models. Polityka Energetyczna Energy Policy J. 2025, 28, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozlak, Ç.B.; Yaşar, C.F. An optimized deep learning approach for forecasting day-ahead electricity prices. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 229, 110129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitsos, V.; Vontzos, G.; Bargiotas, D.; Daskalopulu, A.; Tsoukalas, L.H. Data-Driven Techniques for Short-Term Electricity Price Forecasting through Novel Deep Learning Approaches with Attention Mechanisms. Energies 2024, 17, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, H.; Abdellatif, A.; Ahmad, S.; Zohurul Islam, M.; Muyeen, S.M.; Abdul Mannan, M.; Kamwa, I. Day-Ahead electricity price forecasting using a CNN-BiLSTM model in conjunction with autoregressive modeling and hyperparameter optimization. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 161, 110206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Inekwe, J.; Smirnov, V.; Wait, A.; Wang, C. Seasonality in deep learning forecasts of electricity imbalance prices. Energy Econ. 2024, 137, 107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, B.; Pineau, P.-O.; Charlin, L. Price forecasting in the Ontario electricity market via TriConvGRU hybrid model: Univariate vs. multivariate frameworks. Appl. Energy 2024, 359, 122649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourdaryaei, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Mubarak, H.; Abdellatif, A.; Karimi, M.; Gryazina, E.; Terzija, V. A new framework for electricity price forecasting via multi-head self-attention and CNN-based techniques in the competitive electricity market. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 235, 121207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Feng Wang, Y. A robust electricity price forecasting framework based on heteroscedastic temporal Convolutional Network. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 161, 110177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Bi, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Luo, Z.; Shen, X. A BiGRUSA-ResSE-KAN Hybrid Deep Learning Model for Day-Ahead Electricity Price Prediction. Symmetry 2025, 17, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, A.; Mubarak, H.; Ahmad, S.; Mekhilef, S.; Abdellatef, H.; Mokhlis, H.; Kanesan, J. Electricity Price Forecasting One Day Ahead by Employing Hybrid Deep Learning Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE IAS Global Conference on Renewable Energy and Hydrogen Technologies (GlobConHT), Male, Maldives, 11–12 March 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Deo, R.C.; Casillas-Pérez, D.; Sharma, E.; Salcedo-Sanz, S.; Barua, P.D.; Rajendra Acharya, U. Half-hourly electricity price prediction with a hybrid convolution neural network-random vector functional link deep learning approach. Appl. Energy 2024, 374, 123920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Deo, R.C.; Casillas-Pérez, D.; Salcedo-Sanz, S. Two-step deep learning framework with error compensation technique for short-term, half-hourly electricity price forecasting. Appl. Energy 2024, 353, 122059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Nguyen-Huy, T.; Deo, R.C.; Casillas-Pérez, D.; Masrur Ahmed, A.A.; Salcedo-Sanz, S. Novel deep hybrid model for electricity price prediction based on dual decomposition. Appl. Energy 2025, 395, 126197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, K.; Ahmad, A. Mining latent patterns with multi-scale decomposition for electricity demand and price forecasting using modified deep graph convolutional neural networks. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 39, 101436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, B.; Du, C.; Yang, C.; Gui, W. Outlier-adaptive-based non-crossing quantiles method for day-ahead electricity price forecasting. Appl. Energy 2025, 382, 125328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.Q.; Shen, Y.X.; Yu, X.Y.; Lu, X. Day-ahead electricity price forecasting employing a novel hybrid frame of deep learning methods: A case study in NSW, Australia. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 220, 109300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisoi, R.; Dash, P.K.; Perla, S. Improved decomposition strategy based recurrent ensemble deep random vector functional link network for forecasting short-term electricity price. e-Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2025, 12, 101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Shi, J.; Wang, B.; An, N.; Li, L.; Hou, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Li, H.; et al. A hybrid framework for day-ahead electricity spot-price forecasting: A case study in China. Appl. Energy 2024, 373, 123863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Chen, S.; Yu, H.; Duan, L.; He, Y.; Chu, Y. Simplicity in dynamic and competitive electricity markets: A case study on enhanced linear models versus complex deep-learning models for day-ahead electricity price forecasting. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundu, V.; Simon, S.P. Forecasting of price signals using deep recurrent models. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2024, 15, 5378–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shejul, K.; Harikrishnan, R.; Gupta, H. The improved integrated Exponential Smoothing based CNN-LSTM algorithm to forecast the day ahead electricity price. MethodsX 2024, 13, 102923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Karan, M.B.; Telatar, E. Electricity price estimation using deep learning approaches: An empirical study on Turkish markets in normal and Covid-19 periods. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 224, 120026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Becker, D.M. Day-ahead electricity price prediction applying hybrid models of LSTM-based deep learning methods and feature selection algorithms under consideration of market coupling. Energy 2021, 237, 121543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failing, J.M.; Cardo-Miota, J.; Pérez, E.; Beltran, H.; Segarra-Tamarit, J. Deep learning approaches for predicting the upward and downward energy prices in the Spanish automatic Frequency Restoration Reserve market. Energy 2025, 320, 135245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerasa, A.; Zani, A. Enhancing electricity price forecasting accuracy: A novel filtering strategy for improved out-of-sample predictions. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, A.; Di Persio, L.; Ehrhardt, M. Electricity Price Forecasting via Statistical and Deep Learning Approaches: The German Case. AppliedMath 2023, 3, 316–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, D.K.; Nielsen, P.; Thibbotuwawa, A. Intraday Electricity Price Forecasting via LSTM and Trading Strategy for the Power Market: A Case Study of the West Denmark DK1 Grid Region. Energies 2024, 17, 2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsatoglou, A.; Georgopoulos, G.; Papadopoulos, P.; Antonopoulos, H. An ensemble approach for enhanced Day-Ahead price forecasting in electricity markets. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 256, 124971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Schell, K.R. ATTnet: An explainable gated recurrent unit neural network for high frequency electricity price forecasting. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 158, 109975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ren, J. Application of KNN Algorithm Based on Particle Swarm Optimization in Fire Image Segmentation. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2019, 14, 1707–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Azab, H.-A.I.; Swief, R.A.; El-Amary, N.H.; Temraz, H.K. Machine and deep learning approaches for forecasting electricity price and energy load assessment on real datasets. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, I.; Hassani, K.; Malakouti, S.M.; Suratgar, A.A. Predicting electrical energy consumption for finland using CNN-LSTM hybrid model. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Shao, Y. Advanced Optimal System for Electricity Price Forecasting Based on Hybrid Techniques. Energies 2024, 17, 4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyon, K.; Ritvanen, J. Deep learning-based electricity price forecasting: Findings on price predictability and European electricity markets. Energy 2024, 308, 132877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mae, M.; Yamane, T.; Ajisaka, M.; Nakata, T.; Matsuhashi, R. Enhanced Day-Ahead Electricity Price Forecasting Using a Convolutional Neural Network–Long Short-Term Memory Ensemble Learning Approach with Multimodal Data Integration. Energies 2024, 17, 2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, R.B.; Cleveland, W.S.; McRae, J.E.; Terpenning, I. STL: A Seasonal-Trend Decomposition Procedure Based on Loess. J. Off. Stat. 1990, 6, 3–73. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Du, Y.; Wang, P.; Tian, X.; Xu, Z.; Yang, F.; Chen, L.; Wan, J. A hybrid forecasting method considering the long-term dependence of day-ahead electricity price series. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 235, 110841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Rashed-Al-Mahfuz, M.; Ahmad, S.; Molla, M.K.I. Multiband Prediction Model for Financial Time Series with Multivariate Empirical Mode Decomposition. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2012, 2012, 593018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaev, A.K.; Gorlova, O.S.; Ponkratov, V.V.; Sedova, M.L.; Shmigol, N.S.; Vasyunina, M.L. A Comparative Analysis of the Choice of Mother Wavelet Functions Affecting the Accuracy of Forecasts of Daily Balances in the Treasury Single Account. Economies 2022, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J. Forecasting day-ahead electricity prices with spatial dependence. Int. J. Forecast. 2024, 40, 1255–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L. A novel multivariate electrical price bi-forecasting system based on deep learning, a multi-input multi-output structure and an operator combination mechanism. Appl. Energy 2024, 366, 123233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, X.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, Z.; Jin, T. VMD-ATT-LSTM electricity price prediction based on grey wolf optimization algorithm in electricity markets considering renewable energy. Renew. Energy 2024, 236, 121408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, N.E. Ensemble empirical mode decomposition: A noise-assisted data analysis method. Adv. Adapt. Data Anal. 2009, 1, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Wang, P.; Xu, R.; Han, R.; Chen, E.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X. A novel mid- and long-term time-series forecasting framework for electricity price based on hierarchical recurrent neural networks. J. Frankl. Inst. 2025, 362, 107590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenguer, E.; Segarra-Tamarit, J.; Pérez, E.; Vidal-Albalate, R. Short-term electricity price forecasting through demand and renewable generation prediction. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 229, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenguer, E.; Segarra-Tamarit, J.; Redondo, J.; Pérez, E. Neural Network Model for Aggregated Photovoltaic Generation Forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Conference of the IMACS TC1 Committee, Nancy, France, 16–19 May 2022; pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hua, H.; Chen, X.; Shao, J.; Zheng, J.; Wang, B.; Gan, L.; Yu, K. Spot Market Electricity Price Forecast via the Combination of Transformer and Ornstein-Uhlenbeck Process. In Proceedings of the 2025 21st International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Lisbon, Portugal, 27–29 May 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Arik, S.O.; Loeff, N.; Pfister, T. Temporal Fusion Transformers for Interpretable Multi-horizon Time Series Forecasting. Int. J. Forecast. 2021, 37, 1748–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Castillo, I.; Gunnell, L.; Jiang, S. A New Modeling Framework for Real-Time Extreme Electricity Price Forecasting. IFAC-Pap. 2024, 58, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, S.; Ugurlu, U.; Oksuz, I. Transfer learning for electricity price forecasting. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2023, 34, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashman, L.J. Out-of-sample tests of forecasting accuracy: An analysis and review. Int. J. Forecast. 2000, 16, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourdaryaei, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Karimi, M.; Mokhlis, H.; Illias, H.A.; Kaboli, S.H.A.; Ahmad, S. Recent Development in Electricity Price Forecasting Based on Computational Intelligence Techniques in Deregulated Power Market. Energies 2021, 14, 6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Liang, Z.; Ruan, P. Evaluation on the impact of digital transformation on the economic resilience of the energy industry in the context of artificial intelligence. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Yang, G. Interpretability research of deep learning: A literature survey. Inf. Fusion 2025, 115, 102721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapetrou, P.; Lee, Z. Interpretable and Explainable Time Series Mining. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 11th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), San Diego, CA, USA, 6–10 October 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, E.; Arslan, N.N.; Özdemir, D. Unlocking the black box: An in-depth review on interpretability, explainability, and reliability in deep learning. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 859–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).