Multi-Objective Cross-Entropy Approach for Distribution System Reliability Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- A multi-objective CE approach for reference parameters optimization considering systemic and load point indices at the same process;

- (ii)

- A mathematical deduction of an analytical solution for the multi-objective CE optimization problem, taking into account the standard hypotheses utilized in distribution system reliability assessments.

2. Brief Background on Importance Sampling

3. Multi-Objective CE Approach Using Analytical Formula

3.1. Single-Objective Optimization Function

3.2. Multi-Objective Objective Function

| Algorithm 1 Multi-objective CE algorithm |

|

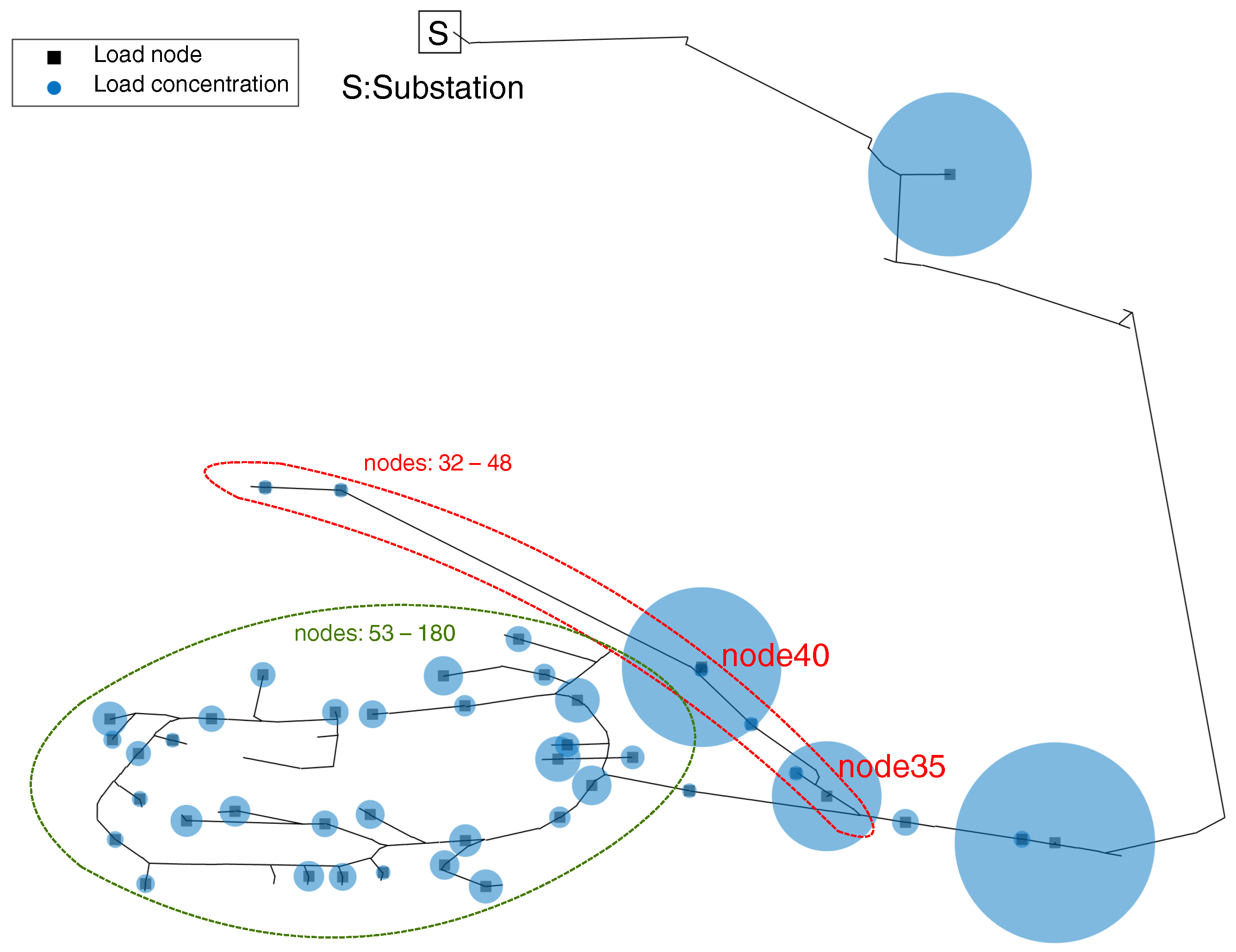

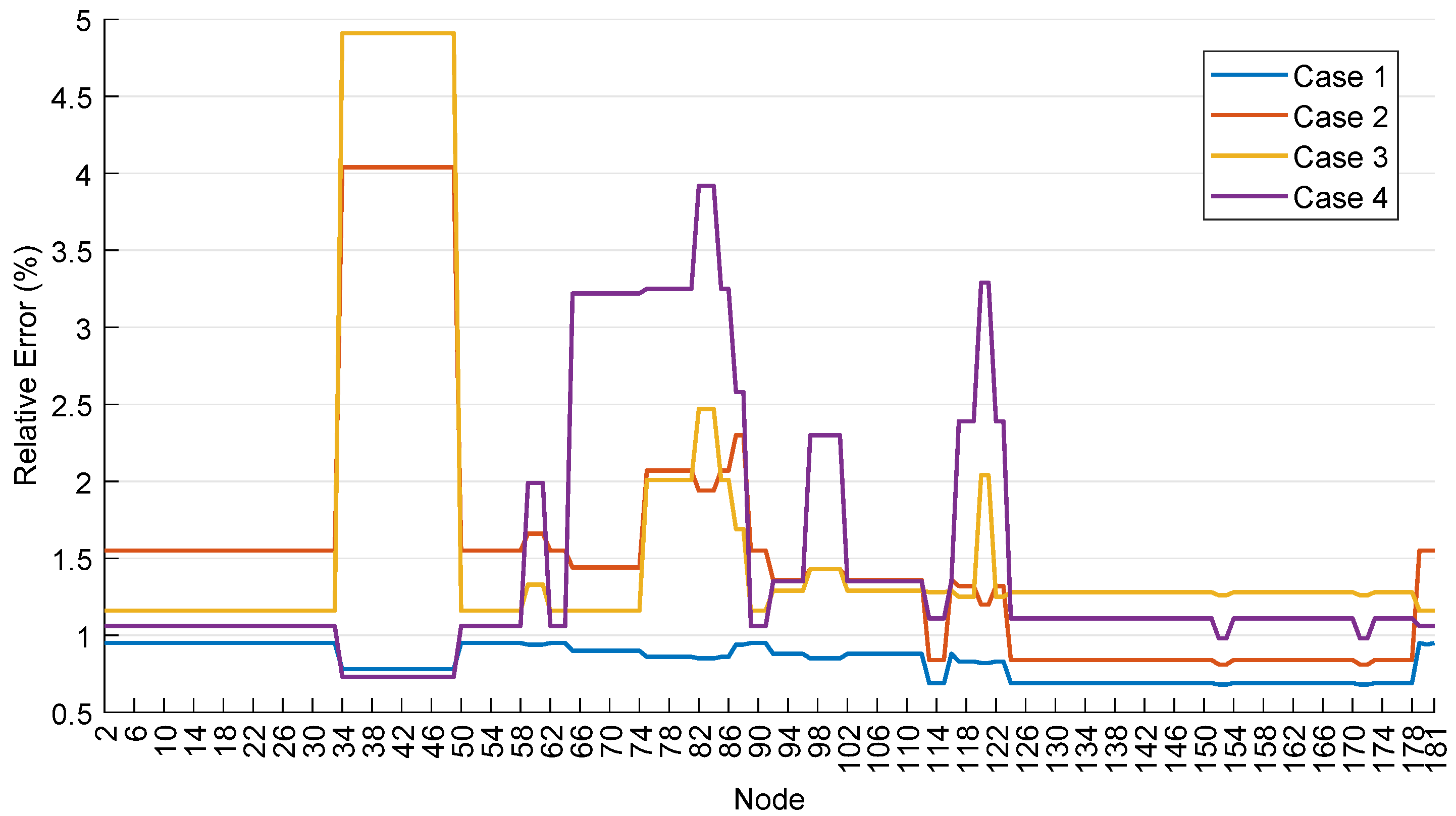

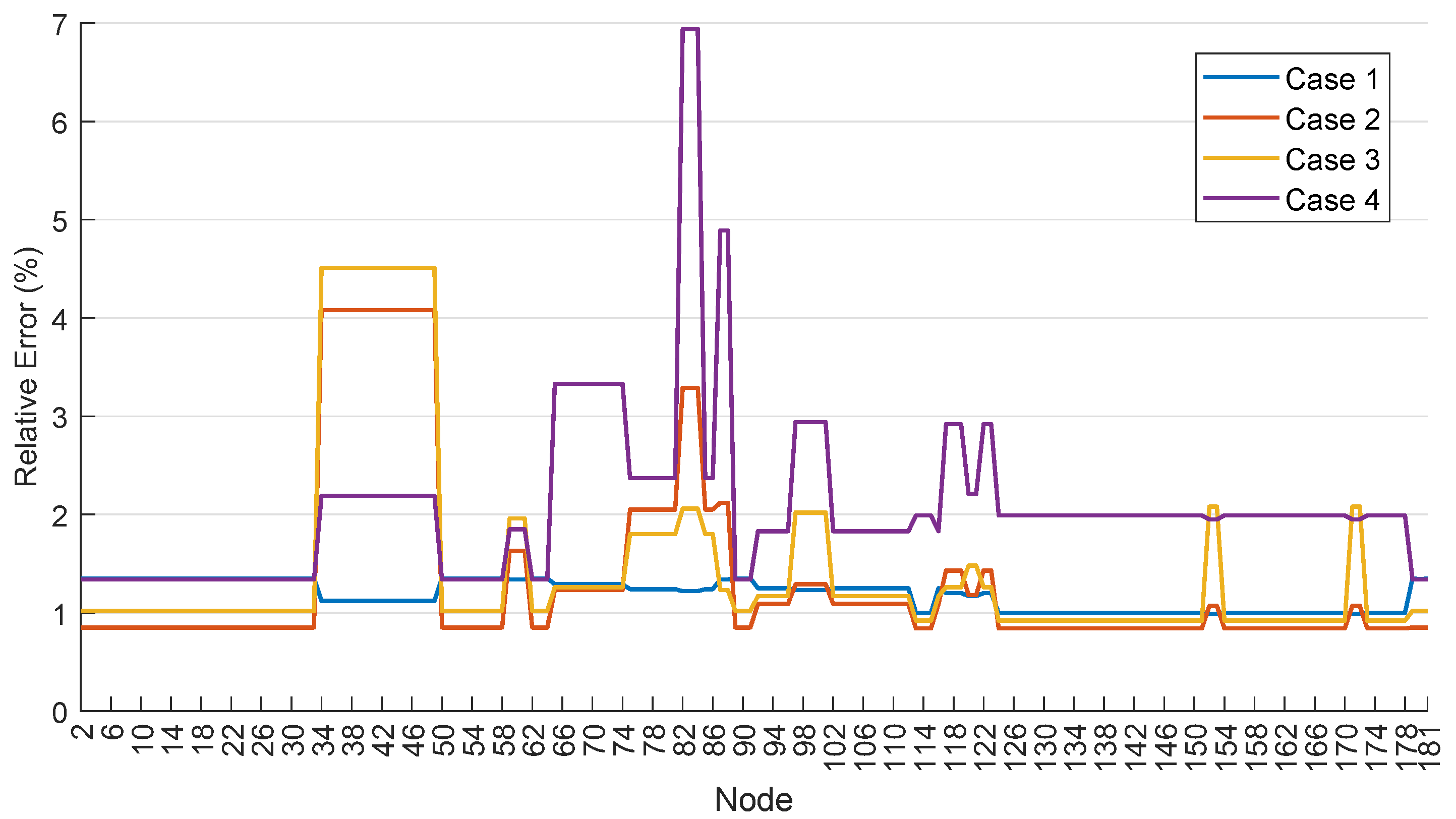

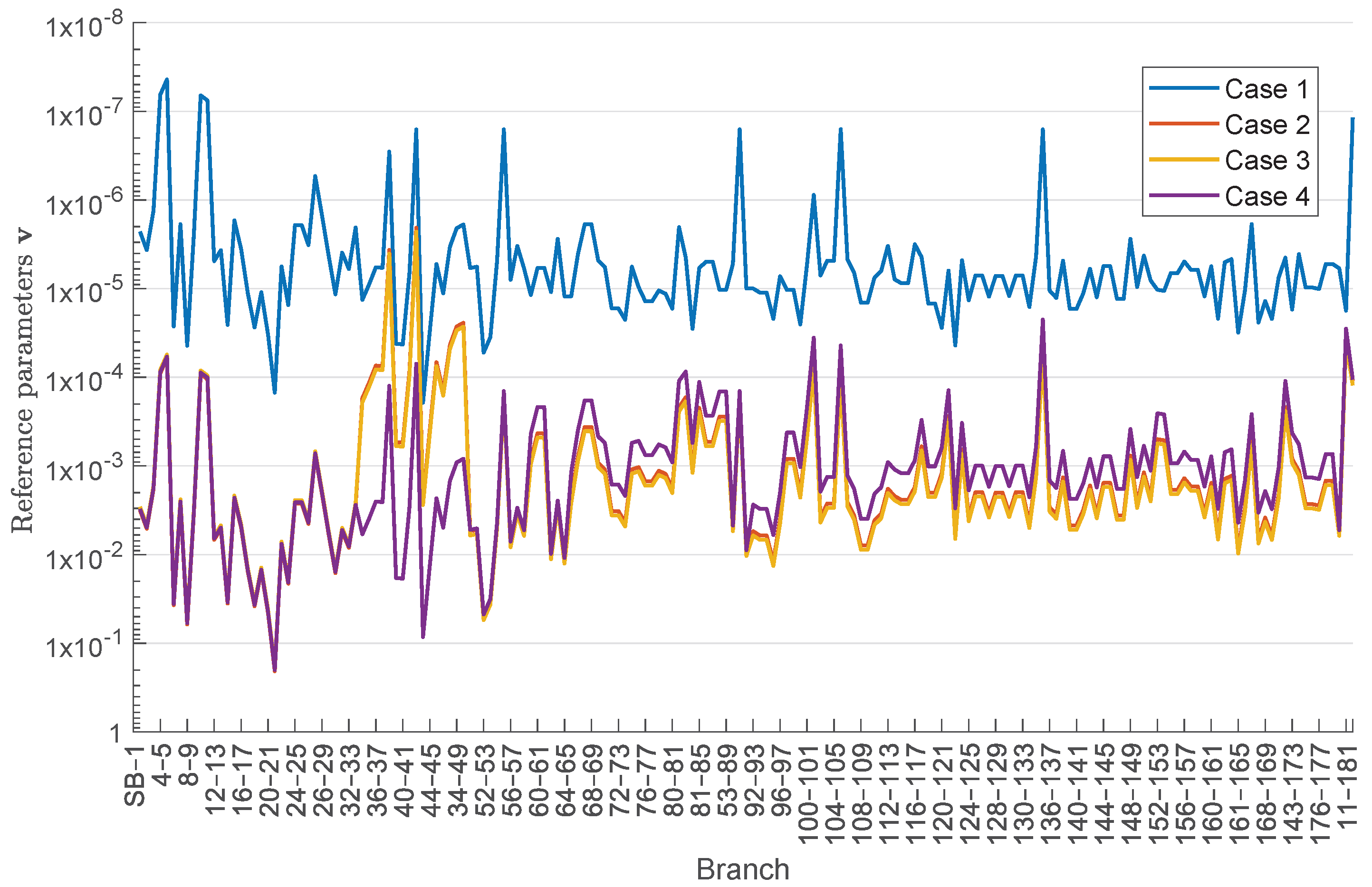

4. Simulation and Result Analysis

- Case 1: application of the crude sequential Monte Carlo simulation;

- Case 2: application of the single-objective CE optimization for the SAIFI index followed by a sequential Monte Carlo simulation;

- Case 3: application of the multi-objective CE optimization approach for the SAIFI and SAIDI indices with equal weights followed by a sequential Monte Carlo simulation;

- Case 4: multi-objective CE optimization for SAIFI and failure rate in node 40 () with equal weights followed by a sequential Monte Carlo simulation.

5. Discussion and Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rubinstein, R.Y.; Kroese, D.P. The Cross-Entropy Method: A Unified Approach to Combinatorial Optimization, Monte-Carlo Simulation and Machine Learning (Information Science and Statistics); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein, R.Y.; Kroese, D.P. Simulation and the Monte Carlo Method, 3rd ed.; Wiley Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leite da Silva, A.M.; Fernandez, R.A.G.; Singh, C. Generating Capacity Reliability Evaluation Based on Monte Carlo Simulation and Cross-Entropy Methods. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2010, 25, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Fernandez, R.A.; Leite da Silva, A.M. Reliability Assessment of Time-Dependent Systems via Sequential Cross-Entropy Monte Carlo Simulation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2011, 26, 2381–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández, R.A.; Leite da Silva, A.M.; Resende, L.C.; Schilling, M.T. Composite Systems Reliability Evaluation Based on Monte Carlo Simulation and Cross-Entropy Methods. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 4598–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.M.; González-Fernández, R.A.; Leite da Silva, A.M.; da Rosa, M.A.; Miranda, V. Simplified Cross-Entropy Based Approach for Generating Capacity Reliability Assessment. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 1609–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite da Silva, A.M.; Costa Castro, J.F.; González-Fernández, R.A. Spinning Reserve Assessment Under Transmission Constraints Based on Cross-Entropy Method. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Li, W.; Yu, J. Composite Power System Reliability Evaluation Based on Enhanced Sequential Cross-Entropy Monte Carlo Simulation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 3891–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urgun, D.; Singh, C.; Vittal, V. Importance Sampling Using Multilabel Radial Basis Classification for Composite Power System Reliability Evaluation. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 14, 2791–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urgun, D.; Singh, C. Composite Power System Reliability Evaluation Using Importance Sampling and Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 20th International Conference on Intelligent System Application to Power Systems (ISAP), New Delhi, India, 10–14 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro Vieira, P.C.; Da Rosa, M.A.; Leite Da Silva, A.M. Long-Term Operating Reserve Assessment of Power Systems with Variable Renewable Generation via Cross-Entropy Method. In Proceedings of the 2022 17th International Conference on Probabilistic Methods Applied to Power Systems (PMAPS), Manchester, UK, 12–15 June 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, B.A.S.; Leite da Silva, A.M.; Milhorance, A.; Assis, F.A. Composite reliability assessment of systems with grid-edge renewable resources via quasi-sequential Monte Carlo and cross-entropy techniques. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.; Disfani, V.R.; Kleissl, J. Reliability Evaluation for Microgrids Using Cross-Entropy Monte Carlo Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Probabilistic Methods Applied to Power Systems (PMAPS), Boise, ID, USA, 24–28 June 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinton, R.; Allan, R.N. Reliability Evaluation of Power Systems; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.E. Electric Power Distribution Reliability; Power Engineering (Willis); CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Amarasinghe, P.; Abeygunawardane, S.; Singh, C. Reliability evaluation of solar integrated power distribution systems using an Evolutionary Swarm Algorithm. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 149, 110464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, Y.P.; Fernandez, E. A novel approach for techno-economic reliability oriented planning and assessment of droop-control technique for DG allocation in islanded power distribution systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 234, 110601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Saw, B.K.; Bohre, A.K. Optimal Distribution Network Reconfiguration to Improve the System Performances using PSO with Multiple-Objectives. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Smart Power System and Sustainable Energy (CISPSSE), Keonjhar, India, 29–31 July 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattabiraman, S.; Sampath, K.; Kannan, M.; Girish, G.R.; Narayanan, K. Reliability Improvement in Radial Distribution System through Reconfiguration. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies-Asia (ISGT Asia), Chengdu, China, 21–24 May 2019; pp. 1963–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, S.; Balachander, K.; Mohamed Mansoor, V. A hybrid technique for impact of hybrid renewable energy systems on reliability of distribution power system. Energy 2024, 306, 132383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, T.P.; Raizer, A. Multi-objective optimization of reliability and cost efficiency in lightning protection for overhead distribution systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 248, 111904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.; Rastegar, M. Optimal planning of fault interrupter and load break switches in power distribution systems: A linear power flow-constrained multi-objective optimization. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 264, 111457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yan, X.; Jia, J.; Shao, C.; Han, L.; Cai, W. Bi-level planning of rotary power flow controllers and energy storage systems for economy and carrying capacity improvement in the distribution network. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 171, 110917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Assis, L.S.; Epifanio, G.P.; Usberti, F.L.; González, J.F.V.; Cavellucci, C. Evolutionary algorithms for switch allocation in power distribution networks with distributed generation. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 249, 112013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, J.; Aldrich, C. The cross-entropy method in multi-objective optimisation: An assessment. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2011, 211, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botev, Z.I.; Kroese, D.P.; Rubinstein, R.Y.; L’Ecuyer, P. Chapter 3-The Cross-Entropy Method for Optimization. In Handbook of Statistics; Rao, C., Govindaraju, V., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 31, pp. 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato, F.S.; Steffen, V.S., Jr. Multi-Objective Optimization Problems: Concepts and Self-Adaptive Parameters with Mathematical and Engineering Applications; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baracy, Y.L.; Venturini, L.F.; Branco, N.O.; Issicaba, D.; Grilo, A.P. Recloser placement optimization using the cross-entropy method and reassessment of Monte Carlo sampled states. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 189, 106653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cases | SAIFI (occ/yr) | SAIDI (h/yr) | ENS (kWh/yr) | Number of Sampled Years | Number of Failures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.5839 | 7.7919 | 14,777 | 9835 | 33,310 |

| 2 | 1.5939 | 7.6146 | 14,607 | 12 | 22,525 |

| 3 | 1.5664 | 7.5935 | 15,038 | 9 | 16,553 |

| 4 | 1.5696 | 7.6717 | 14,564 | 7 | 11,291 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Venturini, L.F.; Buss, B.S.; Pequeno dos Santos, E.; Carvalho, L.M.; Issicaba, D. Multi-Objective Cross-Entropy Approach for Distribution System Reliability Evaluation. Energies 2025, 18, 6421. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246421

Venturini LF, Buss BS, Pequeno dos Santos E, Carvalho LM, Issicaba D. Multi-Objective Cross-Entropy Approach for Distribution System Reliability Evaluation. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6421. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246421

Chicago/Turabian StyleVenturini, Lucas Fritzen, Beatriz Silveira Buss, Erika Pequeno dos Santos, Leonel Magalhães Carvalho, and Diego Issicaba. 2025. "Multi-Objective Cross-Entropy Approach for Distribution System Reliability Evaluation" Energies 18, no. 24: 6421. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246421

APA StyleVenturini, L. F., Buss, B. S., Pequeno dos Santos, E., Carvalho, L. M., & Issicaba, D. (2025). Multi-Objective Cross-Entropy Approach for Distribution System Reliability Evaluation. Energies, 18(24), 6421. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246421