Abstract

This paper presents a numerical study of fuel cycle performance and time–space characteristics of a research-scale high temperature gas-cooled reactor (HTGR) using high-fidelity Monte Carlo simulations with continuous-energy and double-heterogeneity modeling. Three core geometries (V1, V2, V3) and three fuel enrichment levels (5%, 8%, 12%) were analyzed with axial batch refueling strategies. Results show a strong dependence of fuel utilization on geometry and enrichment. The V2 configuration achieves the best performance, with sub-cycle lengths up to 550 days and fuel utilization over 91% at 12% enrichment. V1 and V3 yield shorter cycles but maintain stable power and temperature profiles. In all cases, fuel temperature remained below 1200 K, ensuring a wide safety margin. The similarity of power distributions for different enrichments indicates that a single core design can accommodate various fuel types without compromising safety. These findings support the selection of V2 as a reference configuration for a future HTGR research reactor.

1. Introduction

Within the framework of a national initiative led by the National Centre for Nuclear Research (NCBJ) in Świerk-Otwock, conceptual design activities were launched to develop a low-power high-temperature gas-cooled research reactor (HTGR) with a thermal output of approximately 30 MW. This project is part of a broader international effort focused on the development of advanced Generation IV reactor technologies. These systems are aimed at enhancing intrinsic and passive safety, improving fuel utilization efficiency, and broadening the scope of nuclear energy applications beyond electricity generation.

HTGR technology offers a number of significant advantages, including inherent and passive safety features, high thermal stability, and coolant outlet temperatures in the range of 700–950 °C. Such characteristics enable a wide range of potential applications—from hydrogen production and high-temperature process heat supply to seawater desalination and other industrial processes.

In the present study, the prismatic block-type core design was adopted, drawing inspiration from the well-documented Fort St. Vrain (FSV) reactor concept [1]. This design approach allows for flexible core configuration, well-controlled power and temperature distributions, and the integration of different fuel zoning and burnable poison strategies, which are essential for both achieving high fuel utilization and maintaining nuclear safety margins.

Recent trends in prismatic HTGR core design for moderate power units (i.e., below 200 MW), particularly those intended for cogeneration and polygeneration applications, show a clear tendency toward elongated core geometries (H >> R). This represents a significant departure from the geometric proportions of the historical FSV reactor. However, despite changes in overall core geometry, the basic structure of the fuel block—including its dimensions, fuel element lattice, and coolant channel arrangement—has been largely preserved in most contemporary prismatic HTGR design concepts. This continuity reflects the maturity and proven performance of the original fuel block design, which remains a robust and reliable technological foundation for further reactor development.

Three geometric configurations of the prismatic core were investigated to identify layouts that offer a favorable balance between power density, reactivity control, fuel depletion behavior, and safety characteristics. These core configurations served as a basis for detailed neutronic analyses employing high-fidelity Monte Carlo models, explicitly accounting for the double material–spatial heterogeneity characteristic of HTGR fuel elements.

2. Background and Design Objectives

The design of an HTGR research reactor is guided by well-defined mission objectives that determine the reactor’s operational role and research functions. A key component of the design process is the numerical analysis of different geometric and material configurations of the core, including strategies for partial fuel reloading. Such investigations must consider multiple constraints, ranging from nuclear safety requirements to technological feasibility, fuel cycle efficiency, and economic performance.

2.1. Safety Requirements

The primary safety criteria considered in this study are:

- Maintaining the maximum fuel temperature during a loss-of-coolant accident(LOCA) below 1600 °C, ensuring the integrity of TRISO fuel particles;

- Maintaining the maximum reactor pressure vessel temperature during LOCA below 500 °C, ensuring the mechanical integrity of the vessel.

Meeting these requirements is essential for the safe and robust operation of HTGR systems and places direct constraints on the feasible range of core design strategies.

In addition to these fundamental safety limits, several secondary objectives were defined to ensure long-term stable operation and support the reactor’s experimental mission:

- Axial power shaping to increase power density in the upper region of the core and decrease it in the lower region;

- Radial power flattening to reduce local thermal peaks and improve safety margins;

- Enhancement of fuel utilization.

2.2. Fuel Utilization and Economic Considerations

Fuel utilization in a nuclear reactor can be characterized by several complementary measures:

- (a)

- Burnup (BU)—the total energy released from fission per initial mass of heavy metal (MWd/kgHM);

- (b)

- FIMA (Fissions per Initial Metal Atom)—the ratio of the total number of fissions to the initial number of heavy metal atoms;

- (c)

- FIFA (Fuel Utilization Factor)—the ratio of the total number of fissions to the initial number of fissile atoms.

Among these, FIFA is the most representative metric of the actual utilization of the fissile content, as it indicates what fraction of the original fissile inventory has been converted into energy. Due to the conversion of fertile material into fissile isotopes (e.g., breeding of 239Pu from 238U) and subsequent fission of the bred fuel, the FIFA value may exceed 100%, reflecting the additional contribution from in situ produced fissile material.

Mathematical Formulation

- (1)

- Burnup (BU)Burnup is defined as:

- —total energy released by fission up to time [MWd];

- —initial heavy metal mass [kg].

- (2)

- FIMA—Fissions per Initial Metal Atom

- —total number of fissions up to time ;

- —initial number of heavy metal atoms.

- (3)

- FIFA—Fuel Utilization Factor

- is the initial number of fissile atoms (e.g., 235U, 239Pu, etc.).If the initial fissile fraction is , then

This means that for enriched uranium fuel, FIFA is directly related to FIMA through the enrichment level. If significant breeding occurs (e.g., 238U → 239Pu), FIFA can exceed 1.0, reflecting that more fissile atoms were fissioned than initially present.

Improving fuel utilization is a critical aspect of HTGR design, driven by both economic and environmental considerations. From the economic perspective, higher fuel utilization reduces uranium procurement and fuel fabrication costs, as well as the costs of spent fuel management. Numerical fuel cycle studies indicate that high enrichments combined with low TRISO packing fractions yield the best fuel utilization performance.

However, high fuel utilization typically requires high burnup levels (MWd/kg), which may pose licensing and regulatory challenges. Therefore, adopting moderate burnup levels can offer a practical balance between performance and regulatory feasibility. The optimal strategy should be determined through detailed numerical fuel cycle analyses.

If obtaining regulatory approval for higher burnup levels requires additional experimental evidence, a research reactor provides an ideal platform for such demonstration activities. Moreover, current international trends in HTGR development show a tendency to increase fuel enrichment up to the maximum levels allowed by non-proliferation agreements, further motivating research in this area. In the U.S. AGR (Advanced Gas Reactor) fuel development program, UCO-TRISO fuel has been irradiated up to approximately 18–20% FIMA under conditions representative of reactor operation [2]. Project documentation from X-energy similarly assumes an average TRISO fuel burnup of ~165 GWd/MTU (≈16–17% FIMA) for the Xe-100 reactor design [3].

2.3. Safety Considerations

Because the coolant flows from top to bottom through the core, increasing power density in the upper part of the core has a beneficial effect on temperature distribution during LOCA, inherently supporting the safety requirements. Moreover, strong axial power shaping towards the top offers two additional benefits:

- Higher neutron fluence in the upper region, which enables dedicated irradiation positions for experimental purposes;

- Achieving local power densities at levels of commercial HTGRs, which supports the demonstration mission of the research reactor.

3. Methodology

A continuous-energy Monte Carlo approach was applied to simulate neutron transport and fuel depletion with high physical fidelity. During the simulated fuel cycle, criticality was maintained through adaptive control rod insertion, ensuring that the computed neutron flux and power distributions accurately represent the reactor’s actual operating conditions.

3.1. Monte Carlo Burnup Code System—MCB

The Monte Carlo Continuous Energy Burnup Code (MCB) is a general-purpose computational tool designed to calculate the time evolution of nuclide densities during irradiation or decay processes. The code performs eigenvalue calculations for critical and subcritical systems as well as fixed-source neutron transport calculations to obtain reaction rates and energy deposition needed for burnup analysis.

MCB internally integrates the well-known MCNP code (currently version 5 [4]) for neutron transport calculations with an advanced Transmutation Trajectory Analysis (TTA) module [5], which generates and solves transmutation chains online. The publicly available version, MCB1C has been distributed through the OECD NEA Data Bank (Package ID: NEA-1643) since 2002.

The MCB code has been applied in several advanced reactor studies, including the EU projects [6,7], which focused on neutronics and fuel cycle analysis of helium-cooled reactor systems. In recent years, MCB has undergone continuous development aimed at improving the modelling of modern reactors, particularly double-heterogeneous structures characteristic of HTRs.

The main features of MCB that are used in HTGR fuel cycle analysis are:

- Thermal-hydraulic coupling for prismatic HTRs:Direct coupling with the POKE code [8] and FLUENT [9] allows the simulation of temperature feedback and realistic thermal-hydraulic conditions.

- Heating and decay heat:Heating rates are determined during neutron transport simulation using KERMA factors from standard nuclear data libraries. Additionally, decay heat is computed based on ORIGEN data, enabling afterheat analysis.

- Material processing and shuffling:MCB allows material relocation during burnup, enabling simulation of fuel shuffling, control rod operation, or material movement within the core. The current version allows the user to define models with a larger number of universe levels and to assess statistical fluctuation effects in Monte Carlo reactor simulations.

3.2. Thermal-Hydraulic Coupling with POKE

Thermal-hydraulic effects are introduced into Monte Carlo calculations by coupling MCB with the POKE code. POKE was originally developed at General Atomics for modeling the Fort St. Vrain reactor and later adapted for GT-MHR analysis. The code computes fuel and coolant temperature distributions and coolant mass flow rates under steady-state conditions.

POKE solves the one-dimensional mass, momentum, and energy conservation equations for each coolant channel iteratively. The coolant mass flow rate is determined from the pressure drop balance between inlet and outlet plena.

An initial temperature profile at beginning of life (BOL) can be set by the user or derived from previous thermal-hydraulic simulations. Once invoked, POKE calculates the updated thermal-hydraulic parameters and temperature profiles, which are then passed back to MCB. These temperatures are used to adjust the temperature-dependent cross sections, enabling a new power distribution iteration and a more realistic isotopic evolution during subsequent burnup steps.

3.3. Boundary Conditions for Neutronic Calculations

Neutronic characteristics of a reactor with a strongly moderated neutron spectrum are highly sensitive to the chosen reactivity compensation scheme, since neutron absorbers can substantially perturb the spatial neutron flux distribution. Accurate calculation of neutronic parameters—such as power distribution, burnup, and reactivity coefficients—therefore requires a computational model capable of representing the time-dependent configuration of neutron absorbers used for reactivity control. The influence of absorbers on local power distributions is particularly significant in graphite-moderated HTGRs.

Based on the experience and recommendations from the GEMINI+ project [10], the following reactivity control methods and corresponding modelling constraints have been adopted to minimize undesirable perturbations of the neutron field in the HTGR research reactor core:

- Control-rod placement and Reserve Shutdown Control (RSC):

- The main control rods are located in the reflector, thereby minimizing their direct impact on the neutron flux distribution during normal operation.

- The Reserve Shutdown Control (RSC) system is installed inside the active core but is designed so as not to influence normal operation and not to disturb the neutron field under routine conditions.

- Control-rod grouping and operational strategy:

- Eighteen total control rods are divided into three sections:Section 1: Six startup rods (located in the fourth ring, nearest to the active core). The core is configured so that these rods remain withdrawn during most of the reactor’s operating cycle.Section 2 and Section 3: Compensating groups that are operated sequentially, the first section is fully inserted before the second is engaged.This operational strategy minimizes the time that compensating rods spend inside the active region, thereby limiting flux perturbations.

- Burnable poisons (BPRs) are used primarily to:

- Maintain core reactivity within the operational margin at the beginning of cycle (BOL).

- Flatten the radial power distribution among fuel columns.

The radial and axial BPR distribution is therefore a key design parameter.

3.3.1. Power and Burnup Flattening Objectives

Radial power flattening is the most important design goal for fuel and absorber layout, as it simplifies core cooling, reduces thermal stress, and improves fuel utilization. Axial burnup flattening is also desirable but may be influenced by control-rod effects. It can be achieved more easily through partial axial fuel shuffling during reload, which tends to homogenize end-of-cycle burnup. Burnable poisons can also be used to shape the power profile, mitigating local power and temperature peaks, and thereby reducing the probability of fission product release during off-normal events.

3.3.2. Strategy for Burnable Poison Distribution

The radial distribution of burnable poison is achieved by decreasing the number of BPR pins with increased radial distance from the core center, while keeping the poison content per pin constant.

3.3.3. Reactivity Target and Shutdown Margin

The total amount of burnable poison is chosen such that at BOL the reactor is critical with startup rods fully withdrawn and compensating rods inserted. Full insertion of all control rods at any point in the cycle must result in a negative reactivity margin of at least 5000 pcm, ensuring sufficient shutdown capability.

3.3.4. Axial Profiling and Optimization

In the first design step, a homogeneous axial poison distribution is assumed to establish a stable reference configuration. In subsequent optimization steps, axial poison profiling will be investigated to maximize cycle length and improve burnup uniformity.

3.3.5. Implications of Absorber Modelling

The neutronic model must account for time-dependent absorber configurations (moving control rods and depletion of burnable poisons), updating spatial cross sections at each burnup step. The chosen absorber layout and operational strategy are designed to minimize perturbations of the neutron field during normal operation, but the model must still include key reactivity states (e.g., BOL criticality, control rod insertion cases, worst-case shutdown conditions).

4. Core Configuration and Calculation Setup

4.1. Configuration Background

The design and modelling of the HTGR research reactor core were based on the technical recommendations of the GEMINI+ project and selected geometrical specifications provided by JAEA. These documents offer detailed guidance regarding fuel block geometry, reflector layout, and TRISO particle structure (particularly coating layer thicknesses). However, several essential design parameters—such as enrichment zoning, fuel shuffling strategy, absorber layout and reactivity control system—were defined and optimized in the course of this study to ensure appropriate operational flexibility, safety margins, and good fuel utilization.

The Fort St. Vrain (FSV) fuel block geometry was adopted as the baseline design due to its proven operational performance, extensive validation record, and widespread use in contemporary prismatic HTGR concepts (e.g., GT-MHR, GEMINI+). This design choice ensures high technological readiness, validated thermal-hydraulic behaviour, and a well-characterized neutronic response.

4.2. Core Structure

The core structure is defined by the number of prismatic fuel block columns arranged in a hexagonal lattice and the number of axial layers (fuel block tiers).

Two basic variants were considered:

- V1/V2: Core consisting of 31 fuel columns, corresponding to the GEMINI _A geometry, chosen primarily for economic and compactness considerations, minimizing reactor vessel diameter.

- V3: Core consisting of 19 fuel columns, offering a smaller active volume and reduced initial fissile inventory.

The active core is surrounded by graphite reflector blocks—top, bottom, and lateral—which provide neutron reflection and thermal inertia, improving both neutronic performance and passive safety characteristics. Control rods are placed in dedicated reflector channels to minimize their direct perturbation of the neutron flux distribution during normal operation.

The numerical core models were developed based on GEMINI+ and JAEA specifications and include:

- Geometric parameters:Reactor vessel and core dimensions, vessel–core gap, prismatic fuel block geometry (with and without CR channels), graphite reflector geometry (top, bottom, lateral), fuel compact geometry, coolant channels, control rod channels, TRISO structure.

- Material parameters:Material compositions and densities for structural steel, helium coolant, graphite, TRISO fuel, and uranium enrichment levels.

- Operating parameters:Thermal power, coolant conditions, boundary temperatures.

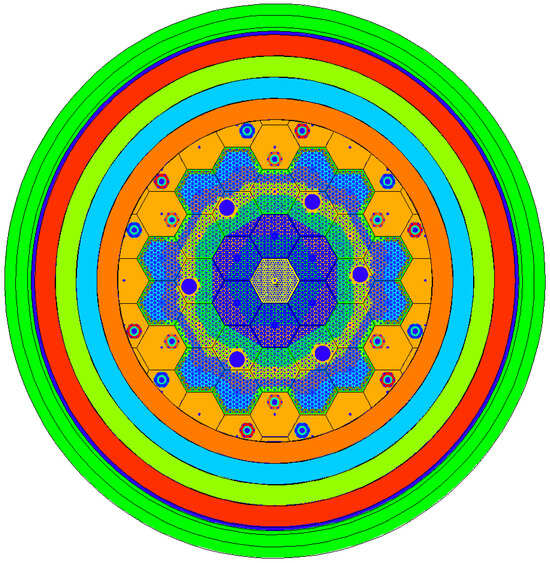

To reduce computational complexity while preserving neutronic fidelity, the reflector geometry was simplified by replacing individual graphite blocks with concentric rings of equivalent mass. This simplification does not affect the calculated neutron flux distributions or reactivity coefficients. Burnup zones were defined independently of the block structure, allowing for finer control of depletion effects without increasing geometric complexity. The general cross section of the reactor with a bigger core diameter (version V1 and V2) divided into burnup zones (marked with different colors) is shown in Figure 1. In the core of the third version—V3—the reflector expands for the entire 3-th ring and all CRs are located in blocks of 4-th ring.

Figure 1.

Cross section of the HTGR research reactor core model of configurations V1 and V2. Areas of the fuel blocks marked with different colors indicate different fuel burnup zones.

4.3. Fuel Block Structure

The fuel block geometry follows the standard prismatic HTGR design based on the historical FSV reactor.

Key features include:

- Hexagonal fuel block with coolant channels, fuel pin channels, and optional control rod channels.

- Graphite matrix providing structural stability and high-temperature capability.

- Central channels used either for burnable poison rods (BPR) or control rod guide tubes depending on block location.

- Geometry compatible with standard block handling and refueling operations.

This fuel block configuration has a long operational history and was successfully cooled without significant overheating or fission product release, as confirmed during post-operation dismantling of the FSV reactor. The same geometry has been adopted in modern HTGR concepts developed by General Atomics, Framatome/AREVA, and European GEMINI+ and PUMA projects, with only minor modifications (e.g., control rod channel diameter).

Burnable poison pins (BPR) are integrated directly into the fuel blocks to flatten the power distribution and support reactivity control throughout the cycle. Table 1 shows the main core fuel block design assumptions used in the present analysis.

Table 1.

Parameters of the fuel blocks in the HTGR reactor.

4.4. Fuel Pin Parameters

The TRISO fuel pin design is defined by three key interdependent parameters. The nominal values adopted in this study are:

- TRISO kernel diameter: 500 µm;

- TRISO packing fraction in compact: up to 30%;

- Uranium enrichment in 235U: 5%, 8%, and 12%.

These values were selected to allow parametric studies of fuel utilization and cycle length while maintaining compatibility with existing TRISO manufacturing capabilities and non-proliferation limits.

Different combinations of enrichment and packing fraction were investigated to evaluate their impact on:

- Fuel utilization (FIFA and FIMA factors);

- Burnup distribution;

- Swing of reactivity over the cycle;

- Achievable cycle length.

4.5. TRISO Packing Fraction

For each enrichment level, an appropriate TRISO packing fraction is selected. Together, these parameters determine the mass of 235U loaded into the fuel-bearing volume of a given batch. After several reloads—combined with shuffling of the fuel remaining in the core—the system gradually approaches a fuel-equilibrium state, in which each subsequent batch restores the fissile inventory to a similar level. This inventory, through the reactivity it provides, ultimately governs the achievable operating time between reloads (the sub-cycle length). The target interval between reloads is assumed to be approximately one and a half years of effective full-power operation (at 100% availability), which translates to a real calendar interval of roughly two years. To meet this requirement at the low enrichments and with smaller core volumes, it becomes necessary to employ the maximum allowable packing fractions (e.g., a 30% limit) and to reduce the number of batches. Nevertheless, in the smallest core volumes—geometries V1 and V3—the available reactivity remains insufficient to allow any reduction in packing fraction. Conversely, for the largest core geometry, increasing enrichment requires lowering the packing fraction in order to achieve the desired cycle length. It should be noted that, from a neutronic standpoint, reducing the packing fraction increases core reactivity for a fixed mass of fissile material and core volume, which in turn improves fuel utilization and supports cycle optimization.

4.6. Enrichment Zoning Strategy

For the partial refueling strategy, homogeneous enrichment is assumed for each reload batch. In the initial core, fresh fuel is loaded uniformly but with reduced packing fraction in zones that will later serve as receiving zones for partially burned fuel after refueling. This approach allows the initial power distribution to approximate the equilibrium power distribution, which would normally only be reached after several reload cycles. Such zoning helps:

- Reduce initial reactivity excess;

- Flatten power distribution;

- Minimize local peaking factors;

- Extend cycle length without additional absorber use.

4.7. Reactivity Control System

The control system is designed to ensure:

- BOL criticality with startup rods fully withdrawn and compensating rods inserted;

- Minimum shutdown margin of 5000 pcm when all rods are fully inserted;

- Minimized local perturbation of the flux field during normal operation.

4.7.1. The Reactivity Control System Consists of Two Main Elements

- Control rods (CR) located in the reflector divided into three sections of 6 rods each:Section 1: six startup rods (nearest to active core), normally withdrawn during power operation;

- Reserve Shutdown Control (RSC) systems located inside the active core (in 6 fuel blocks), function exclusively as an emergency shutdown mechanism, does not affect normal operation and does not distort neutron flux distribution.

4.7.2. Burnable Poison Rods (BPR) Are Additionally Employed to:

- Maintain reactivity within operational margins at BOL;

- Flatten the radial power distribution and reduce reactivity swing;

- Limit the use of control rods during normal operation.

4.8. Fuel Shuffling and Reloading Strategy

A two- or three-batch axial refueling scheme is applied for a core with six axial layers:

- Fresh fuel is loaded in the top layers;

- Partially burned fuel is shifted downward;

- Spent fuel from the bottom layer is discharged.

This axial shuffling strategy contributes to:

- Flattening the axial burnup distribution;

- Reducing reactivity swings between cycles;

- Achieving higher fuel utilization;

- Supporting longer cycle length without increasing enrichment.

This scheme is compatible with standard HTGR refueling technology and allows flexibility in operational planning.

5. Results of Calculations

5.1. Fuel Cycle Analysis of HTGR Core in V1 Geometry for Three Base Enrichments

The V1 core configuration is characterized by a relatively low active height of 232 cm and an axial division into four fuel block layers. Due to the small active volume and limited axial segmentation, a two-batch axial fuel shuffling scheme was identified as the most practical refueling strategy.

A theoretical four-batch refueling scheme was also considered but would require significantly shorter sub-cycle lengths, approximately half of those for the two-batch scheme, which is operationally less attractive, particularly at lower enrichments (e.g., 5%). Preliminary depletion calculations confirmed that the sub-cycle duration becomes too short at low enrichment, reducing operational flexibility.

In equilibrium cycle studies, the initial core composition was selected to produce a spatial power distribution close to the target equilibrium shape, thereby minimizing initial transients. The objective is to obtain an axial power profile with increased power density in the upper layers, which supports passive safety and mimics the behavior of high-temperature reactors under loss-of-coolant conditions.

For the V1 geometry, due to its limited height and shallow achievable burnup, this desired power profile could not be obtained with homogeneous enrichment and packing. Instead, the flux and power distributions exhibited a tendency to peak in the central layers of the core.

To mitigate this effect, a two-zone TRISO packing scheme was introduced:

- Higher packing fraction in the upper layer;

- Lower packing fraction in the lower layer.

After each reload, the blocks are shifted two layers downward.

The adopted packing configurations were:

- 25–30% for 5% enrichment;

- 20–30% for 8% and 12% enrichment.

Equilibrium cycles were calculated for three cases:

- 5% enrichment, 30%/25% packing—case V1_En5%_Pf30%;

- 8% enrichment, 30%/20% packing—case V1_En8%_Pf30%;

- 12% enrichment, 30%/20% packing—case V1_En12%_Pf30%.

The equilibrium sub-cycle lengths obtained for analyzed cases of geometry V1 are shown in Table 2 below, while fuel utilization is shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

The equilibrium cycles obtained in HTGR with geometry V1.

Table 3.

The fuel utilization in HTGR with geometry V1.

5.2. Observations and Trends in Geometry V1

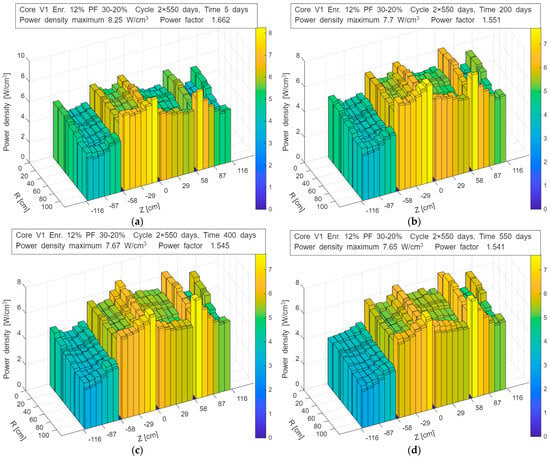

For each case, the time evolution of the power density distribution and the cumulative fission fraction (FIMA) was analyzed. Figure 2 presents the time–space power distributions for the case with 12% enrichment, illustrating the evolution of the axial and radial power shape during each sub-cycle.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the power density distribution in the V1_En12%_Pf30% configuration during operation—up to 550 days: (a) 5 days; (b) 200 days; (c) 400 days; (d) 550 days.

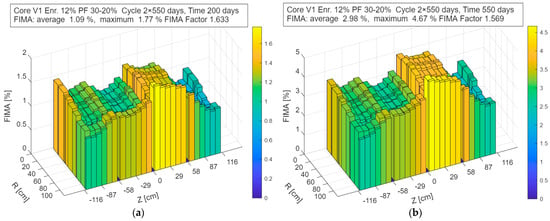

Figure 3 shows the corresponding evolution of the cumulative FIMA after 50 and 150 days of operation. The FIMA values shown in the figures correspond to a single sub-cycle. To obtain the final FIMA for the discharged fuel, these values must be integrated over the entire cycle, i.e., multiplied by the number of refueling steps applied in the fuel management strategy.

Figure 3.

Cumulative fission fraction (FIMA) distribution in the V1_En12%_Pf30% configuration after time of: (a) 200 days; (b) 550 days.

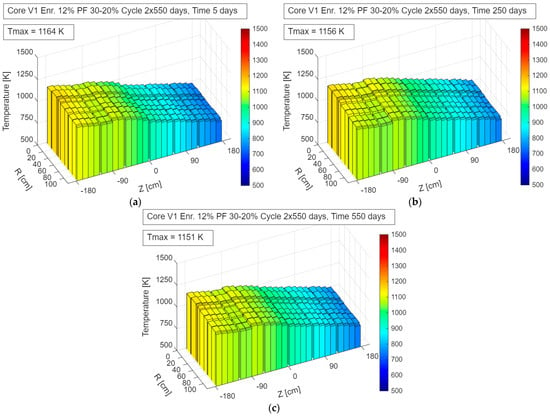

Figure 4 shows the fuel temperature distribution at the beginning, middle and end of the cycle for 12% enrichment case in V1 geometry calculated using CFD Fluent models. The core in the V1 geometry has a relatively small active volume, which necessitates the use of maximum TRISO packing fraction to achieve sufficient excess reactivity. At an enrichment level of 5%, the reactivity reserve is depleted rather quickly, which leads to the need for refueling after only 120 days of operation when using the two-batch refueling strategy. A three-batch strategy would reduce the sub-cycle length to below 100 days, which is operationally impractical.

Figure 4.

Fuel temperature distribution in the V1_En12%_Pf30% configuration during operation—up to 550 days: (a) 5 days; (b) 250 days; (c) 550 days.

For higher enrichments, it is possible to achieve reasonably long sub-cycle durations—approximately 350 days for 8% enrichment and 550 days for 12% enrichment. The best fuel utilization parameters are obtained for the highest considered enrichment level, 12%, although the resulting efficiency remains below 50%, which is not particularly high.

The time–space power distribution is generally well flattened in the radial direction, with the exception of the outer layer, where the power density increases due to the effect of neutron reflection from the graphite reflector. The axial power distribution exhibits local power peaking near the top and bottom boundaries of the core. Axial shuffling of partially burned fuel from the top to the bottom does not significantly reduce the power density in the lower regions, which results from the relatively low achievable burnup in this compact core.

The FIMA distribution shows a relatively uniform integrated burnup per batch, despite moderate local deviations from the average value. This indicates that the adopted refueling scheme provides satisfactory fuel utilization homogeneity.

The fuel temperature distribution exhibits very favorable characteristics:

- Good radial flattening;

- Maximum fuel temperature below 1200 K, i.e., approximately 700 K below the TRISO coating integrity threshold;

- A desirable feature of the distribution is that lower temperatures occur in regions with higher power density, while the highest temperatures are observed in the lower part of the core, corresponding to the region of maximum power density. This behavior provides a comfortable thermal safety margin under normal operating conditions.

5.3. Fuel Cycle Analysis of HTGR Core in V2 Geometry for Three Base Enrichments

The V2 core configuration represents the largest active core volume among the studied geometries. The active core height is 360 cm, and it consists of 31 fuel block columns arranged in a prismatic lattice. Axially, the core is divided into six fuel block layers, each 60 cm high. Several axial fuel shuffling strategies are theoretically possible: two-, three-, or six-batch refueling. From the standpoint of fuel utilization efficiency, refueling with a larger number of batches is preferred, since it allows for a more uniform burnup distribution and better exploitation of the fissile material. On the other hand, increasing the number of sub-cycles inevitably reduces the time interval between refueling operations, which can be a limiting factor in the case of a low-power research reactor. Very short sub-cycle durations decrease reactor availability, which worsens its economic performance and may offset the benefits gained from improved fuel utilization. Considering these trade-offs, a three-batch refueling strategy was identified as the most balanced and optimal choice for this configuration. Thanks to the sufficiently large active volume of the V2 core, it is also possible to vary the TRISO packing fraction as a function of enrichment, thereby improving the flexibility of fuel management and enabling more meaningful comparison between different enrichment levels.

Following a series of preliminary depletion calculations, the packing fraction and sub-cycle lengths were selected in such a way as to achieve similar refueling intervals for different enrichments, which facilitates direct comparison of fuel utilization efficiency as a function of enrichment. However, a limitation arises for the lowest enrichment level (5%), where even with the maximum packing fraction of 30%, the achievable sub-cycle length remains significantly shorter than for higher enrichments.

The adopted packing configurations were:

- 30% for 5% and 8% enrichments;

- 12% for 12% enrichment.

Equilibrium cycles were calculated for three cases:

- 5% enrichment, 30% packing—case V2_En5%_Pf30%;

- 8% enrichment, 30% packing—case V2_En8%_Pf30%;

- 12% enrichment, 12% packing—case V2_En12%_Pf12%.

The equilibrium sub-cycle lengths obtained for analyzed cases of geometry V2 are shown in Table 4 below, while fuel utilization is shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

The equilibrium cycles obtained in HTGR with geometry V2.

Table 5.

The fuel utilization in HTGR with geometry V2.

5.4. Observations and Trends in Geometry V2

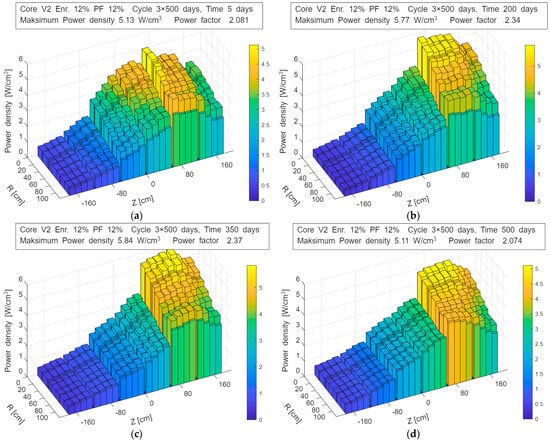

As in previous geometry for each case of enrichment, the time evolution of the power density distribution and the cumulative fission fraction (FIMA) was analyzed. Figure 5 presents the time–space power distributions for the case with 12% enrichment, illustrating the evolution of the axial and radial power shape during each sub-cycle.

Figure 5.

Evolution of the power density distribution in the V2_En12%_Pf12% configuration during operation—up to 550 days: (a) 5 days; (b) 200 days; (c) 350 days; (d) 550 days.

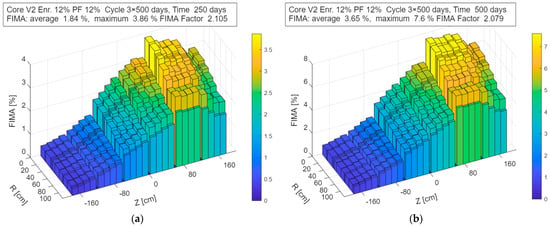

Figure 6 shows the corresponding evolution of the cumulative FIMA after 250 and 500 days of operation. The FIMA values shown in the figures correspond to a single sub-cycle. To obtain the final FIMA for the discharged fuel, these values must be integrated over the entire cycle, i.e., multiplied by the number of refueling steps applied in the fuel management strategy.

Figure 6.

Cumulative fission fraction (FIMA) distribution in the V2_En12%_Pf12% configuration after time of: (a) 250 days; (b) 500 days.

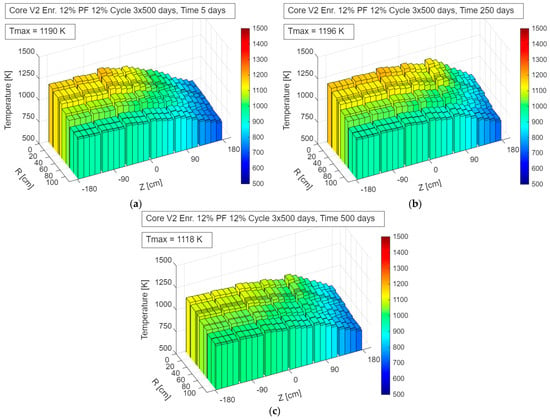

Figure 7 shows the fuel temperature distribution at the beginning, middle and end of the cycle for 12% enrichment case in V2 geometry calculated using CFD Fluent (Ansys 2023 R1) models. The V2 core geometry has the largest active volume among the analyzed configurations, which provides greater flexibility in fuel composition and core zoning. As the enrichment increases, the TRISO packing fraction can be reduced, which has a beneficial impact on core characteristics, including a longer sub-cycle length between refueling operations.

Figure 7.

Fuel temperature distribution in the V2_En12%_Pf12% configuration during operation—up to 500 days: (a) 5 days; (b) 250 days; (c) 500 days.

For the lowest enrichment level of 5%, the use of the maximum TRISO packing fraction (30%) allows a sub-cycle length of approximately 300 days to be achieved. For higher enrichments, in order to reach the target sub-cycle duration of 500 days, the packing fraction must be progressively reduced, as summarized in Table 4.

The best fuel utilization parameters are obtained for the highest considered enrichment (12%), for which the FIMA-to-enrichment ratio exceeds 90%, indicating very efficient fuel use. At 8% enrichment, the fuel utilization efficiency is approximately 10% lower, which still represents a very good performance, particularly for a low-power research reactor.

The time–space power distributions exhibit good radial flattening, except in the outer layer, where a reduction in power density is observed. This effect is caused by the insertion of compensating control rods in the reflector region. Owing to the larger reactivity margins and longer cycle duration associated with the three-batch refueling scheme, the influence of control rod insertion is more pronounced at the beginning of the cycle, gradually diminishing over time as the compensating rods are withdrawn to maintain criticality.

The axial power distribution shows a desirable increase in power density in the upper layers, which results from the top-to-bottom axial shuffling strategy. The FIMA distribution indicates reasonably uniform integrated burnup per batch, despite moderate local deviations from the average, confirming the effectiveness of the adopted fuel management scheme.

The fuel temperature distribution in this geometry also exhibits a very favorable behavior:

- Radially flattened temperature profile;

- Maximum fuel temperature slightly below 1200 K, i.e., approximately 700 K below the TRISO coating integrity limit.

Compared to the V1 geometry, the V2 configuration shows a moderate decrease in both power density and fuel temperature with increasing radius. This effect results from the distribution of burnable poison rods (BPR) and is considered beneficial for this case, as it reduces local thermal loads near the reactor vessel, mitigating potential structural degradation effects over long-term operation.

5.5. Fuel Cycle Analysis of HTGR Core in V3 Geometry for Three Base Enrichments

The V3 core configuration is characterized by a smaller number of fuel block columns—19 compared to 31 in configurations V1 and V2—which results in a significantly smaller active core volume. Despite the reduced radial size, the axial height of the core is 360 cm, with an axial division into six fuel block layers, identical to the V2 geometry.

Given this configuration, the feasible refueling strategies are limited to two- or three-batch axial shuffling schemes. A series of preliminary depletion calculations showed that, especially for the lowest enrichment level of 5%, the time between refueling operations becomes relatively short, which can limit operational flexibility.

For all enrichment levels considered (5%, 8%, and 12%), the maximum TRISO packing fraction of 30% was applied in order to maximize the available reactivity margin and extend the sub-cycle length as much as possible within the constraints of the compact core.

Equilibrium cycles were calculated for three cases:

- 5% enrichment, 30% packing—case V3_En5%_Pf30%;

- 8% enrichment, 30% packing—case V3_En8%_Pf30%;

- 12% enrichment, 30% packing—case V3_En12%_Pf30%.

The equilibrium sub-cycle lengths obtained for analyzed cases of geometry V3 are shown in Table 6 below, while fuel utilization is shown in Table 7.

Table 6.

The equilibrium cycles obtained in HTGR with geometry V3.

Table 7.

The fuel utilization in HTGR with geometry V3.

5.6. Observations and Trends in Geometry V3

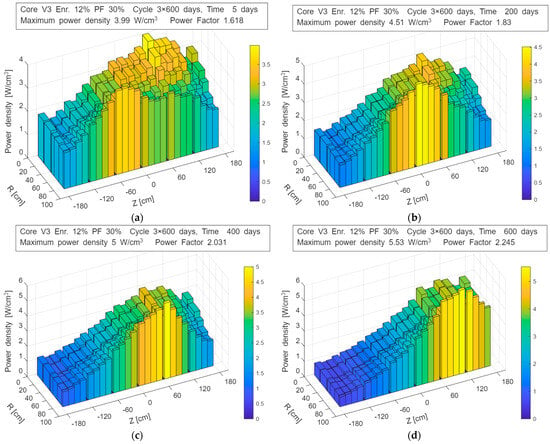

For each case, the time evolution of the power density distribution and the cumulative fission fraction (FIMA) was analyzed. Figure 8 presents the time–space power distributions for the case with 12% enrichment, illustrating the evolution of the axial and radial power shape during each sub-cycle.

Figure 8.

Evolution of the power density distribution in the V3_En12%_Pf30% configuration during operation—up to 600 days: (a) 5 days; (b) 200 days; (c) 400 days; (d) 600 days.

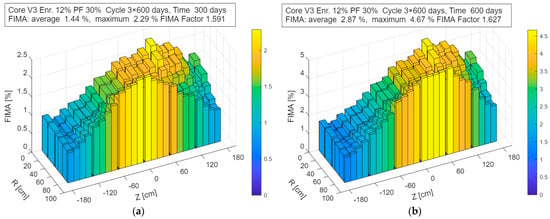

Figure 9 shows the corresponding evolution of the cumulative FIMA after 300 and 600 days of operation. The FIMA values shown in the figures correspond to a single sub-cycle. To obtain the final FIMA for the discharged fuel, these values must be integrated over the entire cycle, i.e., multiplied by the number of refueling steps applied in the fuel management strategy.

Figure 9.

Cumulative fission fraction (FIMA) distribution in the V3_En12%_Pf30% configuration after time of: (a) 300 days; (b) 600 days.

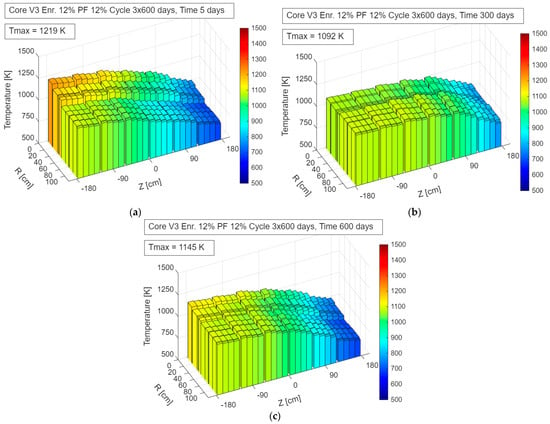

Figure 10 shows the fuel temperature distribution at the beginning, middle and end of the cycle for 12% enrichment case in V3 geometry calculated using CFD Fluent models. The V3 core geometry has a smaller active volume, comparable to the V1 configuration, but resulting from a reduced number of fuel block columns combined with an increased core height. As a consequence, this configuration exhibits features that combine the characteristics of both V1 and V2 geometries. The small radial size necessitates the use of high TRISO packing fractions to ensure sufficient reactivity throughout the cycle.

Figure 10.

Fuel temperature distribution in the V3_En12%_Pf12% configuration during operation—up to 600 days: (a) 5 days; (b) 300 days; (c) 600 days.

Despite this, for the lowest enrichment of 5%, the reactivity margin is depleted rapidly, requiring refueling after only about 120 days of operation, but when applying a three-batch refueling strategy. For higher enrichment levels, it becomes possible to achieve reasonably long sub-cycle durations, approximately 400 days for 8% enrichment and 600 days for 12% enrichment.

The best fuel utilization parameters are obtained for the highest enrichment level of 12%, where the FIMA-to-enrichment ratio exceeds 70%. Although this is a good result, it is not as high as in the V2 geometry, reflecting the limitations imposed by the smaller core volume.

The power density, FIMA, and fuel temperature distributions exhibit hybrid behavior, intermediate between those observed for the V1 and V2 configurations. Specifically:

- The results are improved compared to V1;

- Less favorable than in V2;

- But still show well-behaved and stable spatial–temporal profiles with acceptable ranges of variation.

Overall, the V3 configuration represents a compact core option that retains satisfactory neutronic and thermal characteristics, though at the cost of reduced fuel utilization efficiency compared to the larger V2 core.

6. Discussion

In order to enable direct cross-comparison between considered configurations Table 8 summarizes the key outputs of core performance metrics, which can help readers quickly identify trade-offs between compactness (V1/V3) and efficiency (V2).

Table 8.

Summary of core performance metrics.

Nuclear fuel is utilized most efficiently in the V2 core configuration, which combines the largest active core volume with a favorable balance between neutron economy and thermal–hydraulic behavior. As expected, fuel utilization improves with increasing enrichment, primarily due to the extended irradiation time and higher achievable burnup.

An important observation is that, for different enrichment levels within the same geometric configuration (V1, V2, or V3), the spatial power and temperature distributions remain qualitatively very similar. This means that a single core design can accommodate different enrichments without compromising reactor safety margins, provided that reactivity control and refueling strategies are properly adjusted.

For the highest enrichment level (12%), the V2 configuration achieves a fuel utilization efficiency exceeding 91%, making it the most promising option from both a neutronic and economic perspective. The V1 and V3 configurations yield lower values due to their smaller active volumes and shorter sub-cycle durations.

Another clear advantage of the V2 geometry is the stability of both power and temperature distributions throughout the fuel cycle. This stability translates into predictable operational behavior, reduced thermal gradients, and increased safety margins, which are particularly valuable in a research reactor setting, where flexible experimental operation may be required.

Fuel Licensing Challenges for High-Burnup TRISO Fuel

The choice of the optimal enrichment level and fuel management strategy will ultimately depend on the allowable discharge burnup for TRISO fuel. Achieving high fuel utilization efficiency requires the ability to operate the fuel at burnup levels close to 100 MWd/kgHM, which is technically feasible but may impose additional licensing and qualification requirements.

Early high-temperature gas-cooled reactors—such as the British DRAGON, the German AVR and THTR-300, the American Peach Bottom-1 and Fort St. Vrain (FSV)—used highly enriched uranium (HEU) fuel, typically up to 93% 235U. The motivation was to support the thorium fuel cycle by converting 232Th → 233U, with 235U acting as the fissile driver. Because early HTRs suffered from limited availability—owing to frequent outages, operational problems, and several abnormal events—the discharged fuel often exhibited significantly lower burnup than theoretically achievable. Nevertheless, decades of accumulated operational and post-irradiation data enabled continuous refinement of coated-particle fuel fabrication, leading to major improvements in TRISO quality.

Following global non-proliferation policy shifts, HEU-based HTR concepts were abandoned. Contemporary TRISO-fueled reactor designs use HALEU (High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium) in the range of 5–20% 235U [11,12], fully aligned with current regulatory expectations.

After termination of the German HTR program, additional irradiation testing was performed under the HFR-EU1bis campaign [13] using German-manufactured LEU-TRISO fuel. Pebbles irradiated at up to 1250 °C exhibited very low fission-product release at burnup levels of ~10–11% FIMA. Subsequent KüFA accident-simulation tests at JRC-ITU subjected these irradiated pebbles to 1600 °C and later 1700 °C, representing bounding temperatures for LOFC (Loss of Forced Cooling) scenarios [14]. No coated-particle failures were observed. However, fractional fission-product releases (R/B ratios) at 1250 °C, originally on the order of 10−6–10−5, increased by approximately two orders of magnitude when the temperature was elevated to 1700 °C, showing a clearly diffusion-controlled, monotonic rise over ~600 h. Releases were measurable for both gaseous isotopes (e.g., 85Kr) and volatile metallic species (e.g., 106Ru, 110mAg, 134Cs, 137Cs). These results highlight the complexity of fission-product retention in TRISO fuel: maintaining coating integrity does not guarantee negligible release, particularly for silver.

For TRISO intended for higher burnup, mitigation of hot-spot formation becomes essential, as localized overheating accelerates diffusion-driven releases and could degrade long-term retention over extended irradiation.

Modern licensing of TRISO fuel for ~100 MWd/kgHM requires demonstrating that particle integrity and fission-product retention remain reliable throughout the operating envelope of advanced HTGRs. Regulatory frameworks developed by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) rely on mechanistic fuel-qualification criteria, as formalized in NUREG-2246 [15]. This approach requires an integrated program of irradiation testing, accident testing, and PIE (Post-Irradiation Examination), from which a validated fuel performance envelope is derived (temperatures, fluence, burnup).

A primary licensing challenge is coating-layer durability at elevated burnups, where kernel swelling, internal fission-gas pressure, and SiC corrosion intensify. Acceptable failure fractions must be supported by data from the AGR-1, AGR-2, AGR-5/6/7 campaigns [2] and benchmarked against historical programs such as HFR-EU1bis [14]. Another major issue is fission-product retention, especially for Ag, Cs, and other metallic isotopes whose diffusion increases with burnup.

Reactor-level design plays a direct role in satisfying licensing expectations. HTGRs exhibit strong negative temperature coefficients and naturally flat radial power distributions, which minimize peak fuel temperatures and coating stresses. Furthermore, axial power-density shaping, achieved through top-to-bottom fuel shuffling, positions high-power fuel zones in cooler axial regions of the core. This reduces operational temperature peaks and mitigates the maximum temperature increase during LOFC-type events, strengthening safety margins for high-burnup operations.

7. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive numerical analysis of the fuel cycle performance and time–space characteristics of a research-scale high temperature gas-cooled reactor (HTGR) for three different core geometries (V1, V2, and V3) and three levels of fuel enrichment (5%, 8%, and 12%). High-fidelity Monte Carlo simulations with continuous energy treatment and detailed double-heterogeneity modeling were used to evaluate neutronic behavior, fuel utilization efficiency, and thermal safety margins throughout the fuel cycle.

The results demonstrate that:

- Fuel utilization strongly depends on both enrichment and core geometry.

- The V2 configuration, with its larger active volume and favorable geometry, provides the longest sub-cycle durations (up to 550 days) and the highest fuel utilization efficiency, exceeding 91% for 12% enrichment.

- The V1 and V3 configurations, while compact, exhibit shorter cycle lengths and lower fuel utilization, though still with acceptable neutronic and thermal performance for a research reactor.

- Power and temperature distributions remain stable and well flattened for different enrichments within the same geometry, allowing for flexible adaptation of fuel enrichment levels without compromising safety margins.

- The maximum fuel temperature remained well below 1200 K in all analyzed cases, providing a large thermal safety margin with respect to the TRISO fuel coating failure limit.

The choice of the optimal enrichment level and fuel management strategy will ultimately depend on licensing limits on allowable burnup. Achieving high fuel utilization requires discharge burnup levels close to 100 MWd/kgHM, which may be within reach of modern TRISO fuel technology.

From a design and operational perspective, the V2 configuration emerges as the most promising option, offering the best balance between fuel efficiency, operational flexibility, and safety margins, while the V1 and V3 configurations may be advantageous in applications requiring compactness or lower power levels.

These results provide a technical basis for selecting the reference core design for a future Polish HTGR research reactor and for further optimization of fuel cycle strategy, power shaping, and safety assessment.

The presented design studies for a small-power HTR core indicate that favorable power-density distributions can be achieved by combining higher fuel enrichment with a reduced TRISO packing fraction. This approach increases the fuel utilization and lowers the maximum fuel temperature both during nominal full-power operation and throughout LOCA-type accident transients, thereby reducing the risk of significant fission-product release. Since small modular HTRs are expected to operate in cogeneration modes—supplying electricity, heat, and potentially also cooling—thus introducing additional risks associated with coupling nuclear and chemical process systems, minimizing the nuclear-side risk margin is particularly desirable.

Funding

The work was supported by the Polish National Research and Development Center (NCBR) project ‘New reactor concepts and safety analyses for the Polish nuclear energy program’, POWR.03.02.00-00-I005/17 (years 2018–2023). I gratefully acknowledge Polish high-performance computing infrastructure PLGrid (HPC Center: ACK Cyfronet AGH) for providing computer facilities and support within computational grant no. PLG/2024/017230.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Davison, W.R.; Gillette, G.M.; Nirschl, R.J.; Zane, G. Three Dimensional Depletion Analysis for the “as Built” FSV Initial Core (General Atomic Project 1900); General Atomic Company: San Diego, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Demkowicz, P.A. DOE Advanced Gas Reactor Fuel Development and Qualification Program Overview; INL/MIS-24-79248; Idaho National Laboratory: Idaho Falls, ID, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Price, L.L.; Kalinina, E.; Farnum, C.O. Economic Impacts of Irradiated High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium Fuel Management; SAND2024-01681; Sandia National Laboratories: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2024. Available online: https://sai.inl.gov/content/uploads/29/2024/11/econ_impacts_irradiated_haleu_fuel_mgmt_final.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- X-5 Monte Carlo Team. MCNP—A General Monte Carlo N-Particle Transport Code, Version 5; LA-UR-03-1987; Los Alamos National Laboratory: Los Alamos, NM, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cetnar, J.; Stanisz, P.; Oettingen, M. Linear chain method for numerical modelling of burnup systems. Energies 2021, 14, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijper, J.C.; Somers, J.; Van Den Durpel, L.; Chauvet, V.; Cerullo, N.; Cetnar, J.; Abram, T.; Bakker, K.; Bomboni, E.; Bernnat, W.; et al. Plutonium and Minor Actinide Management in Thermal High-Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactors Publishable Final Activity Report; Project of the EURATOM 6th Framework Programme Contract Number: FP6-036457; NRG: Petten, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetnar, J. Advancements in reactor physics modelling methodology of Monte Carlo Burnup Code MCB dedicated to higher simulation fidelity of HTR cores. In Proceedings of the HTR 2014, Weihai, China, 27–31 October 2014. Paper HTR2014-51291. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, W.; Malek, G.; Lund, K. POKE a Gas-Cooled Reactor Flow and Thermal Analysis Code GA-10226 Gulf General Atomic Incorporated; Gulf General Atomic Incorporated: San Diego, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- ANSYS Inc. ANSYS Fluent User’s Guide; Release 2023 R1; ANSYS Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- The Gemini Initiative. Available online: https://gemini-initiative.com/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- U.S. NRC. High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU). Available online: https://www.nrc.gov/materials/new-fuels/haleu (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Hebden, K. TRISO-X Begins Construction on Commercial-Scale Advanced Nuclear Fuel Facility. The Chemical Engineer, 2022. Available online: https://www.thechemicalengineer.com/news/triso-x-begins-construction-on-commercial-scale-advanced-nuclear-fuel-facility/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Futterer, M.A.; Berg, G.; Marmier, A.; Toscano, E.; Freis, D.; Bakker, K.; de Groot, S. Results of AVR Fuel Pebble Irradiation at Increased Temperature and Burn-Up in the HFR Petten. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2008, 238, 2877–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freis, D.; Bottomley, P.D.W.; Kellerbauer, A.I.; Rondinella, V.V.; Van Uffelen, P. Accident Testing of High-Temperature Reactor Fuel Elements from the HFR-EU1bis Irradiation. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2011, 241, 2813–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzewiecki, T.; Schmidt, J.; VanWert, C.; Clifford, P.; Hoellman, J. NUREG-2246: Fuel Qualification for Advanced Reactors; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Rockville, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).