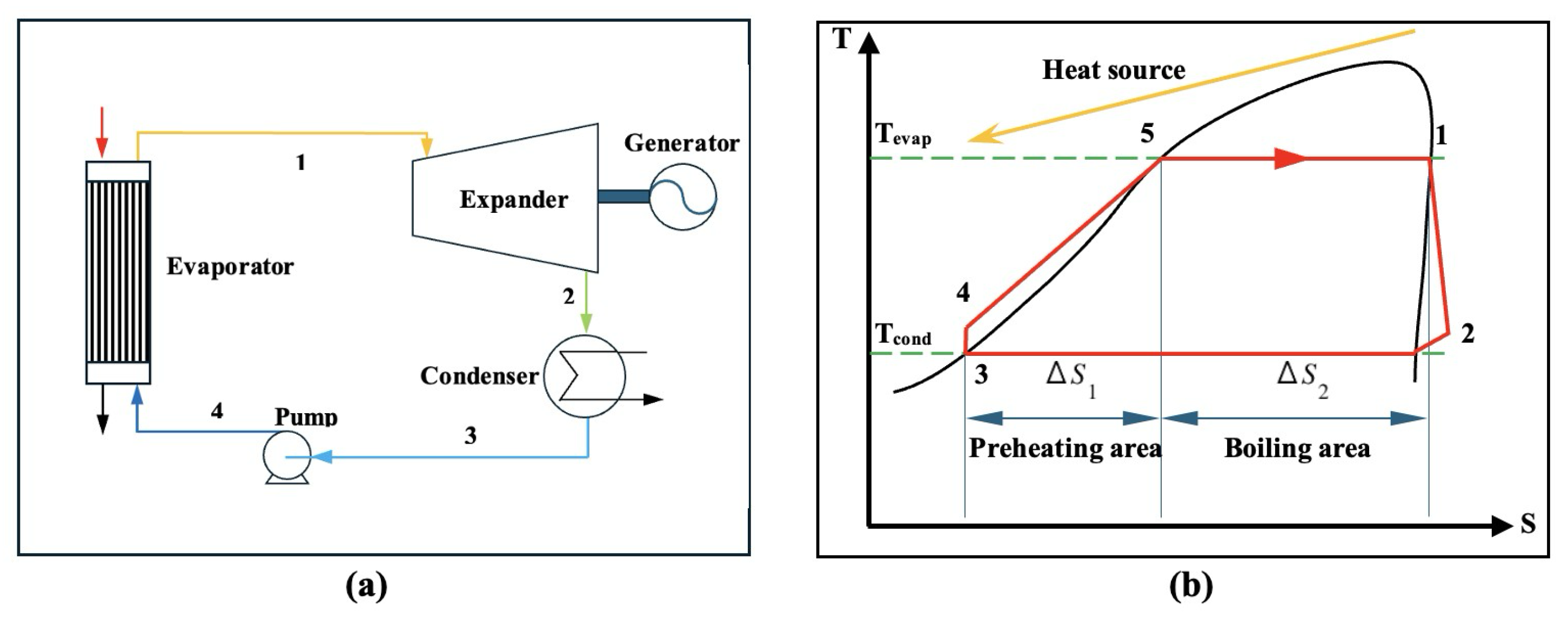

This section presents the economic modeling results and analyzes how key design choices affect the performance of a standard ORC compared to an integrated ORC–ejector refrigeration system. The conventional ORC, used as the baseline, operates with a vapor generator at 90 °C and releases unwanted heat at 30 °C, with an exergy input of 148.781 kW and a shaft work output of 79.717 kW.

5.1. Discussion Based on Energy and Exergy

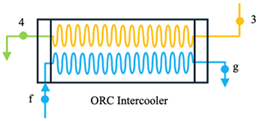

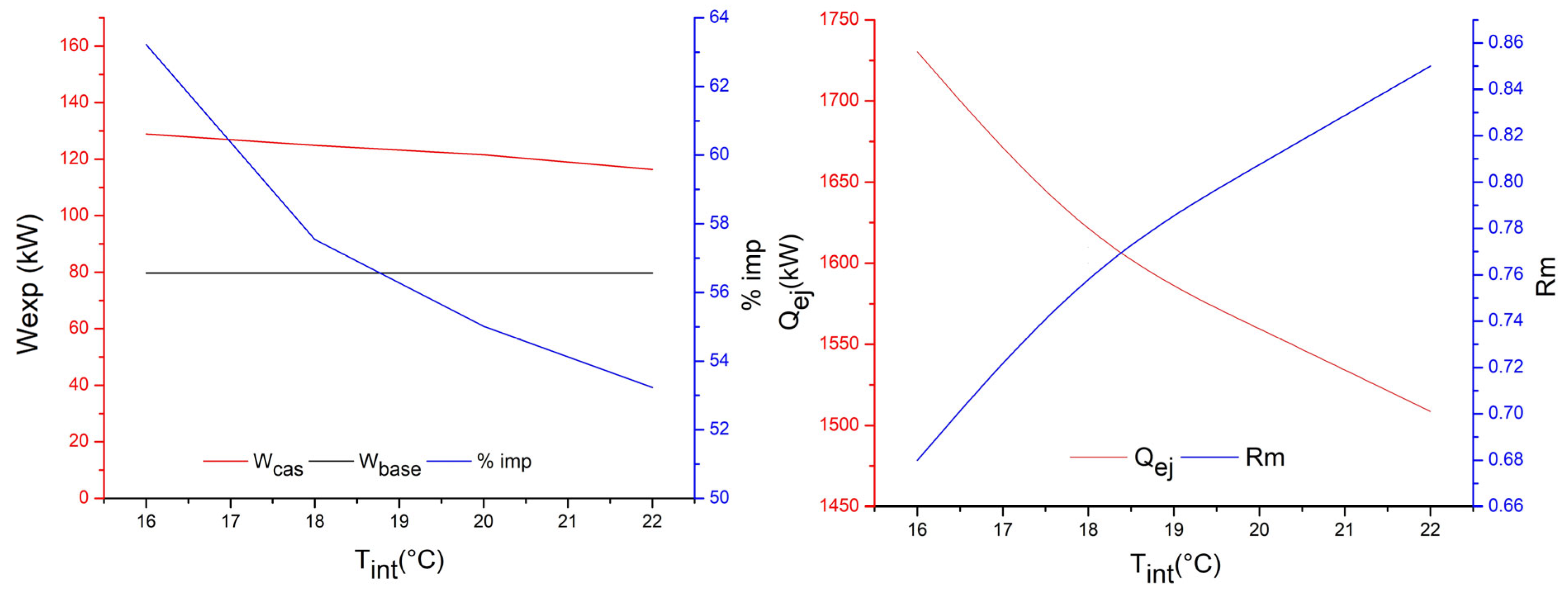

In the ORC–ejector system, the intercooler temperature has a significant impact on the temperature lift across the expander and the exergy supplied to the cycle. Increasing the intercooler temperature from 16 °C to 22 °C decreases the exergy input from 366.852 kW to 312.551 kW (

Table 8). This is the result of a decrease in the temperature difference between the hot and cold streams, which mitigates the heat transfer driving force and increases system irreversibilities. This behavior is consistent with the exergy-destruction patterns reported by Chen et al. [

32] for ORCs under variable heat sink conditions. Higher intercooler temperatures also increase entropy generation during pre-expansion heating, consistent with the second law of thermodynamics characteristics described by Tsatsaronis & Winhold [

26] and supported by recent ORC + ECC studies [

2,

32].

The effect of the intercooler temperature on the mechanical output is consistent with previous findings. As shown in

Table 8, increasing the intercooler temperature reduces the shaft power output from 128.926 kW at 16 °C to 116.345 kW at 22 °C. This result is consistent with the exergy changes predicted by Equation (15), where useful work (W

exp) is associated with the exergy difference between pre- and post-expansion states. Lower intercooler temperatures increase the pre-expansion specific exergy, thereby improving the conversion of thermal energy into mechanical shaft power. These findings agree with the thermodynamic behavior observed in multi-level waste heat ORC plants, where the expander work output is highly sensitive to the pre-expansion exergy defined by the thermal boundary conditions [

33].

These findings confirm that lowering the intercooler temperature reduces thermal irreversibilities, which results in increased exergy being delivered to the expander. This can enhance overall cycle performance. This mechanism accounts for the significant improvement in the ORC + ECC compared to the conventional ORC, especially at relatively low intercooler temperatures. This trend is in good agreement with previous work on ejector-assisted ORC configurations in which a lower condensation pressure can really enhance both thermodynamic and exergoeconomic performance [

12,

21,

34,

35].

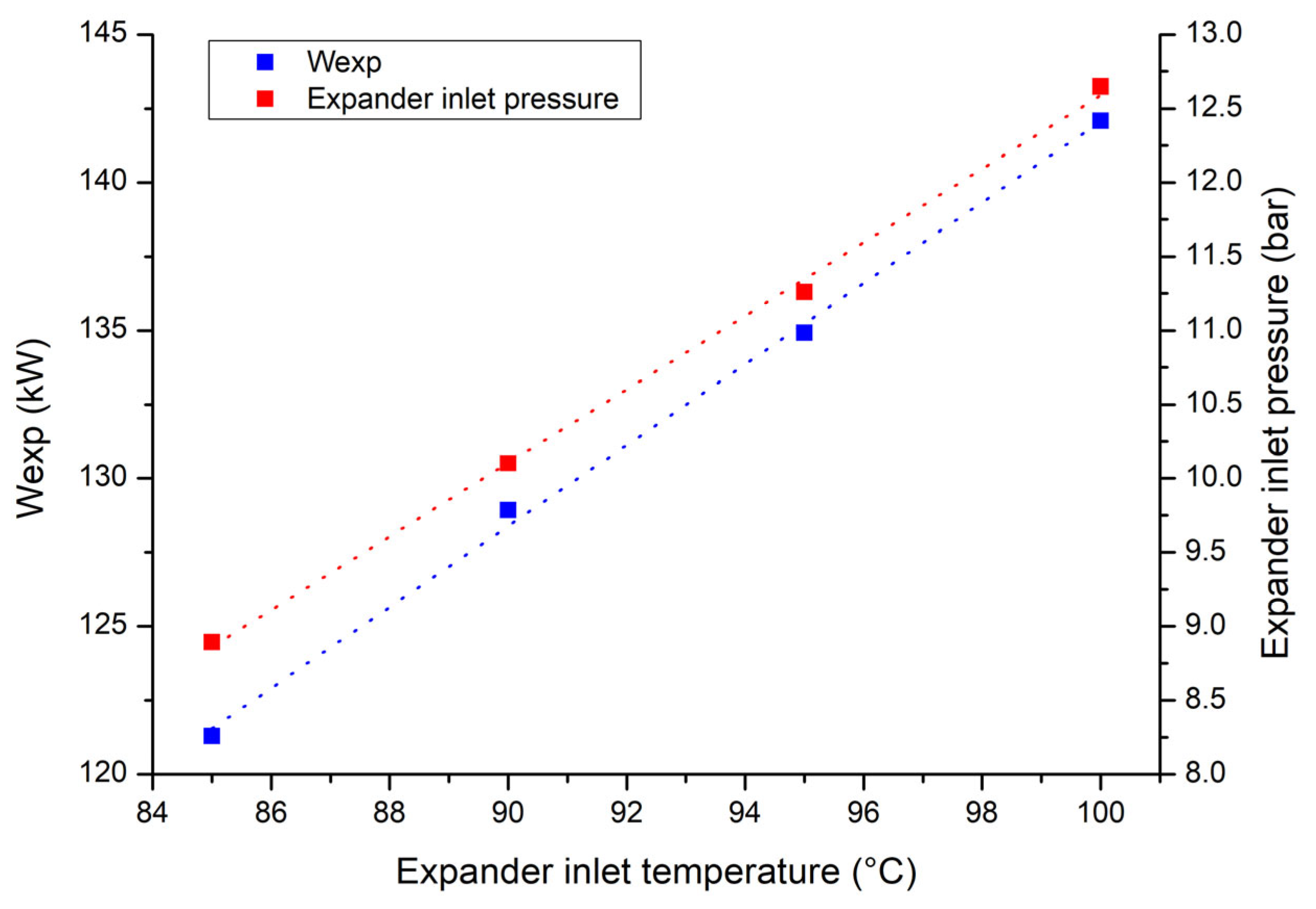

The present work also investigates the impact of the vapor generator temperature on the thermodynamic performance of the ORC + ECC. The exergy input and mechanical output are examined, and the results are shown in

Table 9. It can be seen that increasing the generator temperature from 85 °C to 100 °C increases the exergy supplied to the cycle from 329.5 kW to 439.8 kW. This is the result of a larger temperature difference between the heat source and working fluid during the heating process. Higher generator temperatures also reduce entropy generation in the vapor generator and, hence, can improve the exergy quality of the working fluid.

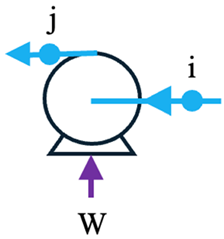

An increase in the exergy input has high potential to yield a higher shaft power output. As shown in

Table 9, the expander shaft work rises from 121.2 kW at 85 °C to 142.0 kW at 100 °C. According to Equation (15), the useful work output is proportional to the exergy difference across the expander (due to a larger expansion pressure ratio). Therefore, a higher generator temperature has high potential for thermal-to-mechanical power conversion, decreasing the irreversibilities associated with the expansion process.

The overall trend indicates that the working temperature of the vapor generator is a key parameter in the performance of both the conventional ORC and the ORC + ECC. Higher generator temperatures increase the available exergy and move the system closer to its optimal thermodynamic path in which the expander efficiency and overall cycle efficiency are improved. This interpretation agrees with classical exergetic analyses of thermal systems [

21,

26] and is supported by ORC + ECC investigations that show a reduction in the exergy destruction and higher shaft work at higher heat source temperatures. The improvement mechanism is also consistent with the experimentally validated ejector-assisted ORC behavior proposed by Chen et al. [

2].

A comparison of the effects of varying the intercooler temperature and generator temperature shows that the exergy input and shaft power output respond differently. Increasing the intercooler temperature from 16 °C to 22 °C reduces the exergy input from 366.8 kW to 312.5 kW and decreases the shaft work output from 128.9 kW to 116.3 kW. This behavior agrees with heat transfer and second-law principles: a higher cold-side temperature lowers the thermal potential difference and reduces the available exergy.

Increasing the generator temperature from 85 °C to 100 °C raises the exergy input from 329.5 kW to 439.8 kW and increases the shaft work output to 142.0 kW. This improvement results from a vapor-greater hot-side thermal potential difference, which boosts the evaporating pressure, heat exchange effectiveness, and conversion of thermal energy into mechanical work. These findings are in good agreement with thermodynamic analyses of ORC systems operating under high source temperatures by Dai et al. (2009) [

7] and Zhang et al. (2019) [

36].

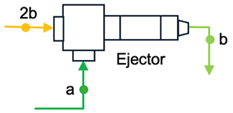

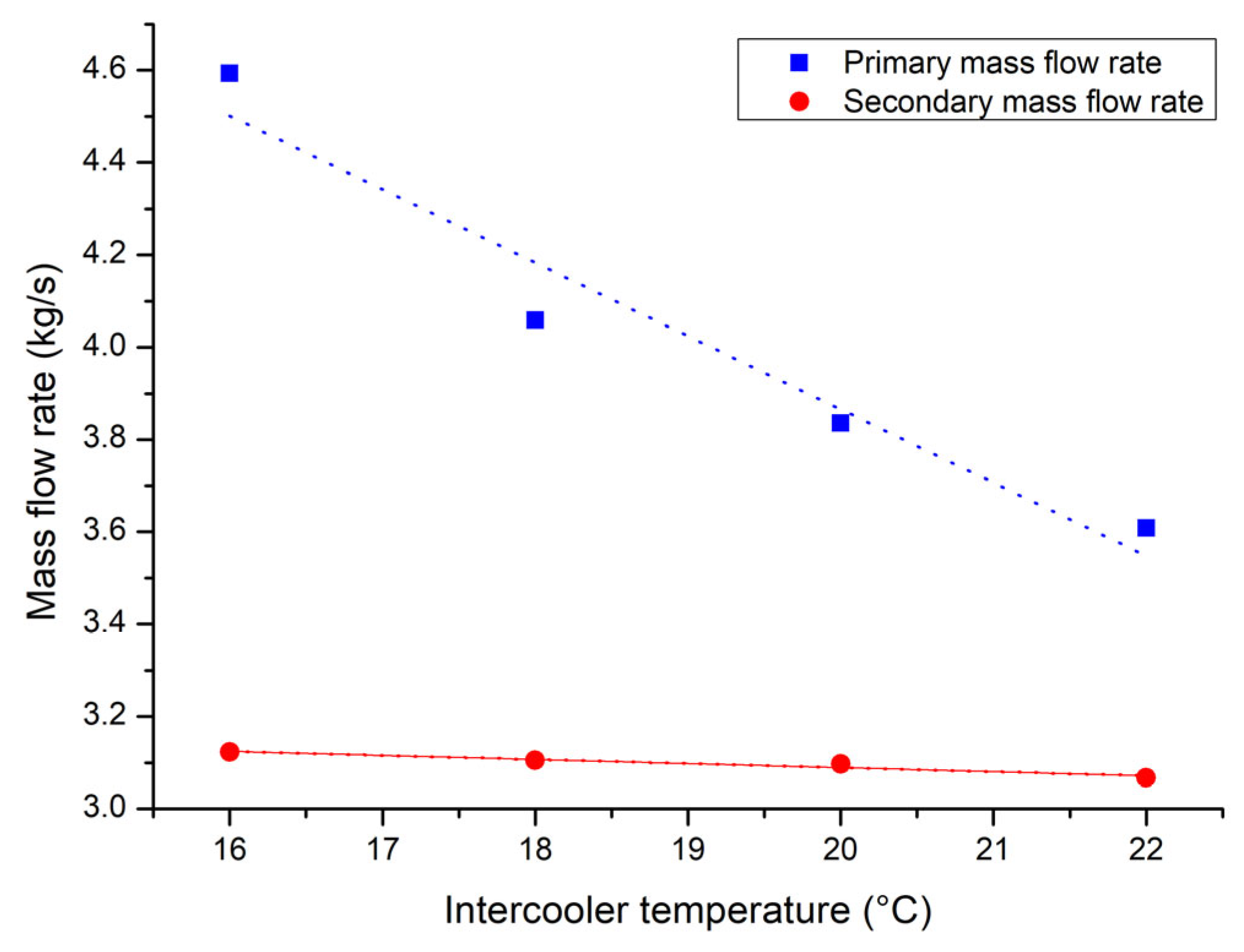

Figure 5 shows the primary and secondary mass flow rates against the intercooler temperature and indicates that increasing the intercooler temperature from 16 °C to 22 °C reduces the primary mass flow from 4.6 kg/s to 3.6 kg/s, while the secondary mass flow decreases slightly. The primary flow rate decreases because higher intercooler temperatures lower the working fluid density and suction pressure, which results in a lower mass entrainment capability. The slight decrease in the secondary mass flow rate is due to less sensitivity to the cold-side temperature in this operating range, consistent with characteristics reported in ejector-based ORC studies by Chen et al. [

2] and recent preheated-ejector ORC studies by Hu et al. [

37].

In an ejector cooling cycle, the intercooler temperature directly relates to the thermodynamic state of the primary (motive) and secondary (suction) streams. As the intercooler temperature increases, a higher secondary flow rate can be produced at a fixed primary mass flow rate (or a higher ability to produce cooling capacity). In other words, a lower primary mass flow rate is required for achieving an identical cooling capacity. This results in a higher entrainment performance when operating at higher intercooler temperatures. A lower primary mass flow rate means that the heat input to the system is decreased accordingly, which may provide better thermal performance of the whole system. However, the power generation results shown in

Figure 6 do not hold true. This behavior is consistent with modern ejector flow dynamics reported in recent ORC + ECC studies [

5,

13,

38].

Figure 6 shows that as the intercooler inlet temperature increases, the expander work output produced by the ORC + ECC decreases from 128.93 kW at 16 °C to 118.50 kW at 22 °C, even though the mass flow rate of the ECC is reduced (decreasing heat input). The reason for this is that at a lower intercooler temperature, the expansion pressure ratio across the expander is larger, which can yield higher shaft power. Under the same operating conditions (same heat source/heat sink), the baseline ORC remains nearly constant at around 80 kW due to the condenser operating at an ambient temperature, unlike in the case of the ORC + ECC. As a result, the improvement potential of the ORC + ECC over the baseline drops from approximately 62% to just above 50%. This confirms that lower intercooler temperatures significantly enhance the energy conversion efficiency of the integrated system.

As the intercooler temperature increases, the ECC requires a lower heat load from approximately 1720 kW to 1510 kW because of a reduction in the thermal driving potential between the hot and cold streams. Conversely, the entrainment ratio increases from 0.67 to 0.85 with higher intercooler temperatures, which indicates better mixing and momentum transfer processes inside the ejector when the intercooler temperature is increased. These trends are consistent with the experimentally validated ejector performance characteristics reported in Chen et al. [

2].

These findings highlight a clear thermodynamic trade-off:

Lower intercooler temperatures: higher expander work and greater exergy efficiency but require a higher heat load at the ejector.

Higher intercooler temperatures: lower heat demand and a higher entrainment ratio but reduced mechanical output.

Similar temperature-dependent thermodynamic behavior has been documented in ejector-assisted ORC systems, where the interaction between the ejector suction temperature and primary/secondary flow dynamics governs exergy performance [

2,

32].

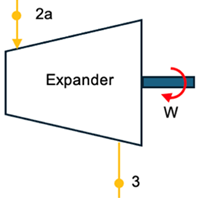

Figure 7 also shows that increasing the expander inlet temperature from 85 °C to 100 °C raises the mechanical power output from approximately 121 kW to 142 kW, while the inlet pressure rises from about 8.25 bar to 12.4 bar. This combined increase in pressure and temperature improves the specific exergy of the working fluid entering the expander, resulting in greater expansion work. This outcome is consistent with the published work in [

7,

39], in which higher upstream temperatures enhance the thermodynamic driving potential and reduce internal irreversibilities.

Furthermore, higher inlet temperatures increase inlet specific exergy, which can improve the energy conversion of thermal energy into mechanical power output. This in good agreement with previous work [

2,

21].

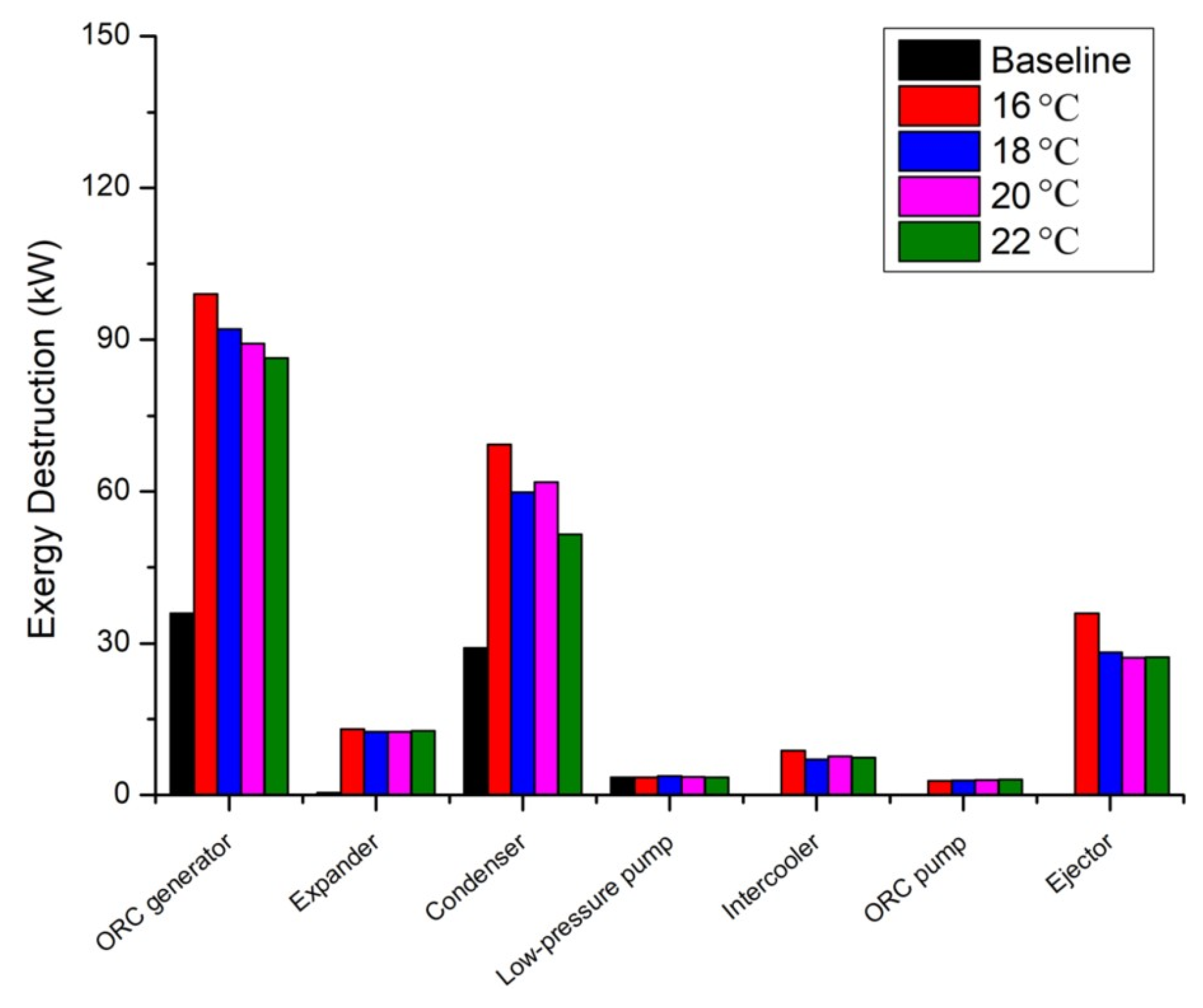

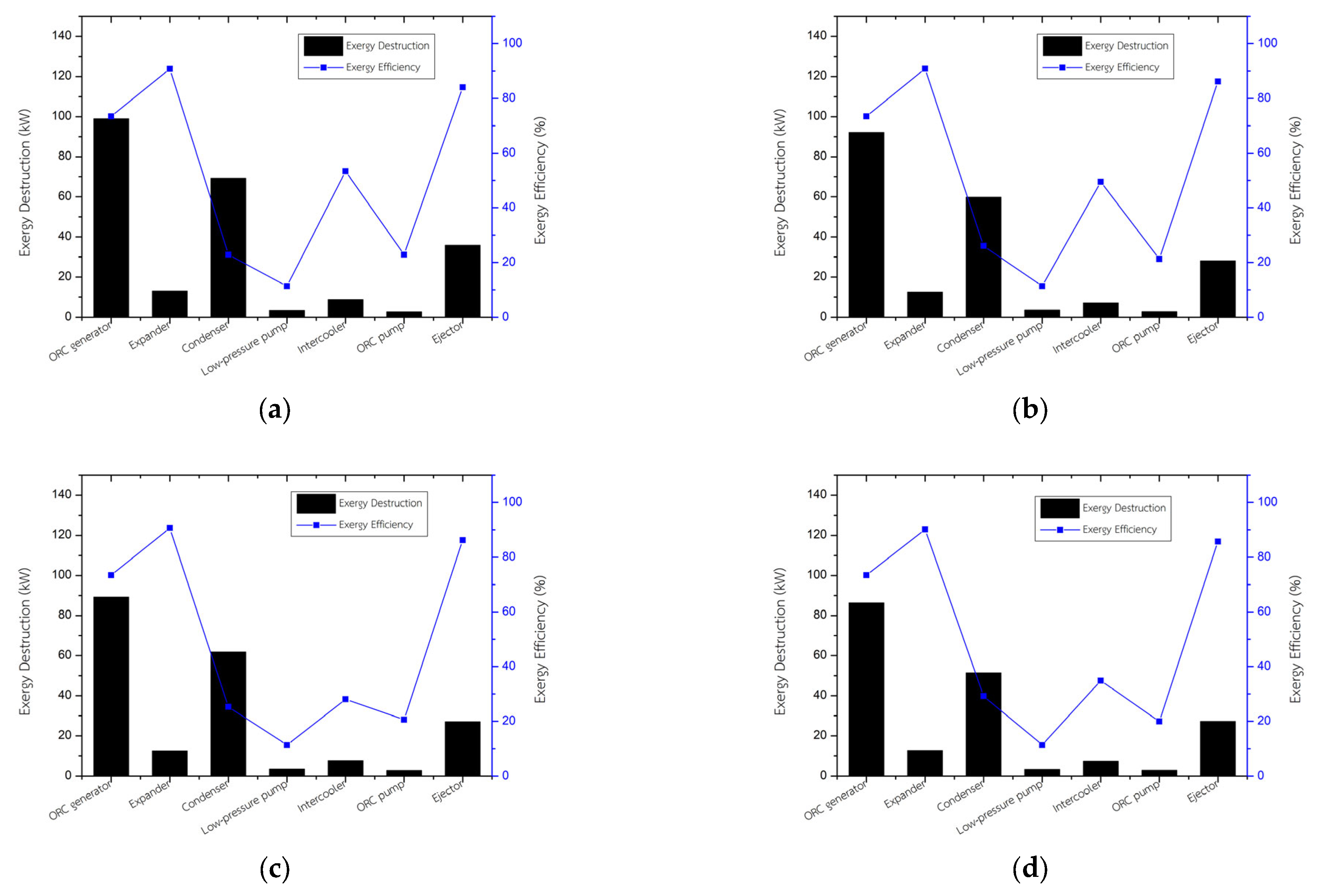

This study proposes a comparison of the exergy destruction of two ORC configurations: a conventional ORC and the ORC + ECC. Four intercooler outlet temperatures (16 °C, 18 °C, 20 °C, and 22 °C) are examined to assess how the change in the intercooler temperature affects the exergy destruction in key system components.

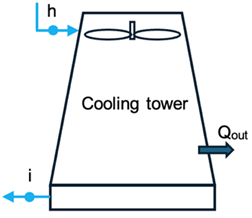

Figure 8 presents the variation in exergy destruction across key ORC–ejector system components at intercooler inlet temperatures ranging from 16 °C to 22 °C. In the comparison, the vapor generator of both systems is the major source of thermodynamic irreversibility (highest exergy destruction). The exergy destruction rises from 35.97 kW to 96.2 kW at 16 °C, then decreases to 88.1 kW at 22 °C. This pattern highlights the generator’s sensitivity to the temperature difference during heat addition, as higher thermal driving forces increase entropy generation [

8,

39]. The condenser follows a similar trend, increasing from 29.12 kW to 67.4 kW at 16 °C, then decreasing to 54.1 kW at 22 °C. The pump, intercooler, and ORC pump each contribute less than 9 kW under all conditions. Ejector-side irreversibilities peak at 32.8 kW at 16 °C and stabilize near 27.5 kW at higher temperatures, consistent with ejector behavior under varying primary and secondary flow conditions [

2,

36]. Expander exergy destruction shows the greatest improvement over the baseline system. At 16 °C, expanders in the ejector-assisted ORC deliver 128.5 kW of useful work, decreasing to 120.2 kW at 22 °C. This result supports the principle that lower intercooler temperatures increase the pre-expansion specific exergy and reduce expansion losses [

7].

Overall, although the ejector cooling side introduces some additional irreversibilities, its integration consistently reduces exergy destruction in major components compared to the baseline ORC. Its capacity to limit irreversibility at higher intercooler temperatures demonstrates improved adaptability and cycle stability, which are important advantages for low-grade waste heat applications.

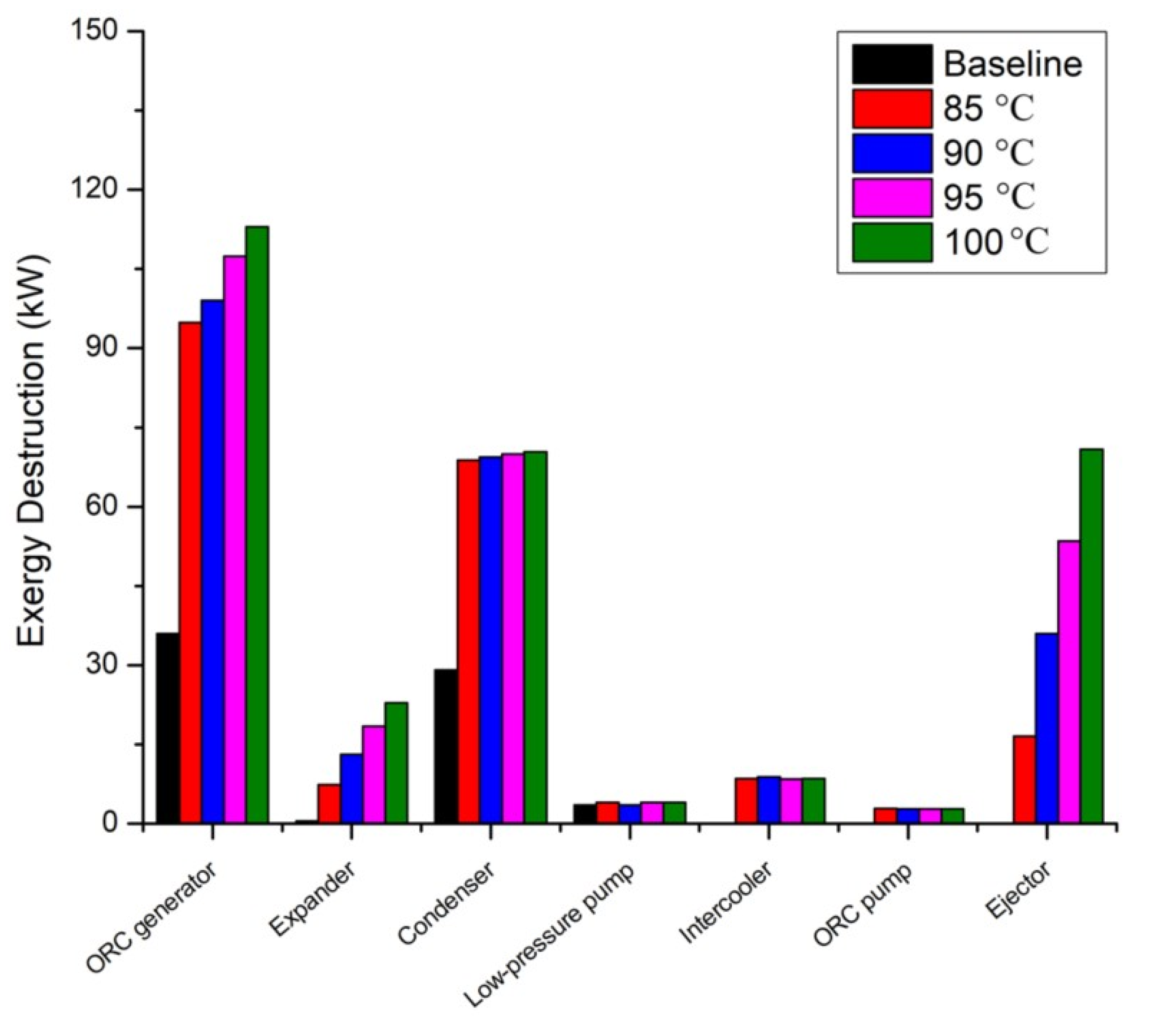

Figure 9 shows the distribution of exergy destruction among the main components of the ORC–ejector system at generator temperatures of between 85 °C and 100 °C. As the heat source temperature rises, the ORC generator experiences the largest increase in irreversibility, from 94.2 kW at 85 °C to 112.4 kW at 100 °C, which is much higher than the baseline of 35.9 kW. This trend aligns with second-law principles: a greater temperature difference between the external heat source and the working fluid increases entropy generation during vaporization, resulting in higher exergy destruction in the boiler [

21,

30]. Expander exergy destruction also increases significantly, from 9.7 kW to 25.1 kW, as the generator temperature rises. This higher expander irreversibility results from the greater exergy supplied to the expander at elevated heat source temperatures. Although more exergy is available, some is inevitably lost due to internal irreversibility resulting from higher flow velocities, an increased specific volume, and greater deviation from isentropic expansion [

8]. Condenser exergy destruction remains relatively stable at 67–69 kW, nearly double the baseline value of 29.1 kW. These higher condensation losses result from the increased condenser load at elevated generator temperatures, which cause larger temperature differences during heat release. The pump, intercooler, and ORC pump together contribute less than 10 kW, showing that mechanical work losses are minor compared to thermal components. Ejector-side exergy destruction increases moderately, from 19.8 kW at 85 °C to 34.7 kW at 100 °C. This is due to greater momentum exchange and mixing losses caused by higher primary flow pressure and velocity at elevated generator temperatures [

2].

Despite higher exergy destruction in several components, the system offers a clear benefit: the expander work output rises significantly, from 120.3 kW to 145.6 kW, compared to 83.2 kW in the baseline ORC. This shows that higher generator temperatures improve thermomechanical power recovery, even as the exergy destruction increases. Overall, the results confirm that higher heat source temperatures enhance useful exergy and second-law efficiency, despite increased component-level losses.

To provide a clear comparison,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 are simultaneously interpreted based on the dominant sources of exergy destruction. In all cases, the ORC generator and condenser remain the major source of exergy destruction because of a large temperature difference during heat addition and release. When the ECC is integrated into the ORC, there is a decrease in the condensation temperature, which shifts part of the exergy destruction away from the expander toward the condenser and cooling tower. This is the result of operating with a lower expander backpressure and the working characteristics of the ejector cooling loop. Lowering the expander’s backpressure via an intercooler is key to reducing the exergy destruction at the expander. Hence, the ORC + ECC can achieve better expander performance and greater useful exergy output. In contrast, the baseline ORC maintains a higher expander irreversibility fraction due to the higher condensation pressure. These trends are consistent with the second law of thermodynamic behavior reported in recent ORC studies [

11,

38,

40]. Therefore,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 together clarify how condenser-side cooling and the intercooler temperature shape system-wide irreversibilities (indicating exergy destruction). This allows us to demonstrate the better thermodynamic quality in the ORC–ejector even when the system is operated under tropical conditions (similar ambient temperature to the conventional ORC).

Figure 10 presents the exergy destruction and exergy efficiency of each component of the ORC + ECC under intercooler temperatures of 16–22 °C. A decrease in the intercooler temperature can significantly mitigate exergy destruction, especially in the heat exchanger components (vapor generator and condenser), which agrees with second law of thermodynamics principles [

21,

30].

At 16 °C, the highest exergy destruction (about 110 kW) is found at the vapor generator. The exergy destruction decreases when the intercooler temperature increases. The reason for this is a smaller temperature difference between the working fluid and the heat source. The condenser is the second-largest source of exergy destruction, decreasing from approximately 70 kW at 16 °C to 50 kW at 22 °C. This is due to the phase transition during the condensation process. At the ejector, the exergy destruction remains moderate (25–35 kW), with an exergy efficiency of around 80%. This indicates that the ejector maintains strong entrainment performance regardless of the intercooler temperature, consistent with previous findings [

2,

9]. The expander achieves the highest exergy efficiency among all components, typically above 90%, with destruction of 8–12 kW. Such results indicate that the mechanical expansion process generates less destruction than thermal processes. Lower intercooler temperatures can increase the specific exergy at the expander inlet, thereby improving the conversion to shaft power. All liquid pumps exhibit relatively low exergy destruction (less than 10 kW), with exergy efficiencies ranging from 40% to 70%. Slight variations in the intercooler temperature have a slight impact on the changes in the working fluid density and pumping power, as noted in previous ORC optimization studies [

8,

36]. This has a slight impact on exergy destruction when varying the intercooler temperature.

Overall,

Figure 10 confirms that lower intercooler temperatures can improve component exergy efficiencies and reduce system irreversibilities (lower total exergy destruction), especially in the generator and condenser. This is consistent with the earlier conclusion that the intercooler temperature is a key design variable affecting both thermal performance and second-law efficiency in the ORC + ECC.

Figure 11 illustrates the exergy destruction and component efficiencies of the ORC + ECC as the generator temperature increases from 85 °C to 100 °C. It can clearly be seen that higher generator temperatures reduce the exergy destruction in components associated with heat addition and expansion, thereby strengthening thermodynamic performance. This behavior is consistent with fundamental exergy theory and previous analyses of high-temperature ORC configurations [

2,

36].

The vapor generator has the highest exergy destruction among all components, increasing from 105 kW at 85 °C to about 115 kW at 100 °C. This rise is due to a larger temperature difference between the heat source and the working fluid during the heating process. Although the entropy generation in the generator is increased, the higher inlet temperature significantly increases the specific exergy of the vapor entering the expander. This effect enables a greater yield of useful mechanical work. The condenser has the second-highest exergy destruction (around 65–70 kW under the investigated temperatures, with exergy efficiencies of between 20% and 30%). A slight change in the exergy destruction of the condenser indicates that the changes in the generator temperature have a slight effect on the condensation irreversibilities. This means the exergy destruction in the condenser primarily depends on the temperature difference during heat release rather than upstream heat addition. The expander performs the highest thermodynamic performance, as it shows the lowest exergy destruction, with efficiencies of up to 90% at all generator temperatures. Exergy destruction increases from about 10 kW at 85 °C to nearly 23 kW at 100 °C due to higher specific exergy at the expander inlet. This can increase the useful mechanical work; however, entropy generation during the expansion process through the expander is also increased. Despite this, high efficiency shows the potential of converting exergy input into useful mechanical work. The ejector shows a moderate increase in exergy destruction, from about 20 kW at 85 °C to over 60 kW at 100 °C, while maintaining efficiency near 80%. This is due to increased entrainment and higher motive flow velocity at higher generator temperatures, as also reported in recent ORC–ejector studies [

9,

36]. Although higher generator temperatures are the cause of more mixing irreversibilities being produced in the ejector, the performance is acceptable because the increased motive flow exergy supports efficient momentum transfer between streams.

Overall, the component-level analysis in

Figure 11 shows that increasing the generator temperature enhances the available exergy, improves expander performance, and increases cycle efficiency, despite higher destruction in thermal components. This confirms that the generator temperature is a key thermodynamic factor controlling power recovery and second-law efficiency in the ORC + ECC.

The ORC + ECC can perform lower total exergy destruction than the conventional ORC, as presented in

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. The key to this is thermodynamic improvement by means of the ejector cooling cycle. The ejector can produce lower suction, which results in a cooling effect produced at the intercooler. Furthermore, pressure recovery via the presence of a shock wave (known as the pressure lift effect) is a significant process in which the system can release unwanted heat at a relatively high condenser pressure. This results in decreased entropy generation during phase change and reduces exergy destruction in both the condenser and the expander. A lower expander discharge pressure via the intercooler can lead to a higher expansion pressure ratio across the expander, which results in higher useful exergy (mechanical shaft power) and less exergy destruction within the expander.

5.2. Discussion Based on Economics and Exergoeconomics

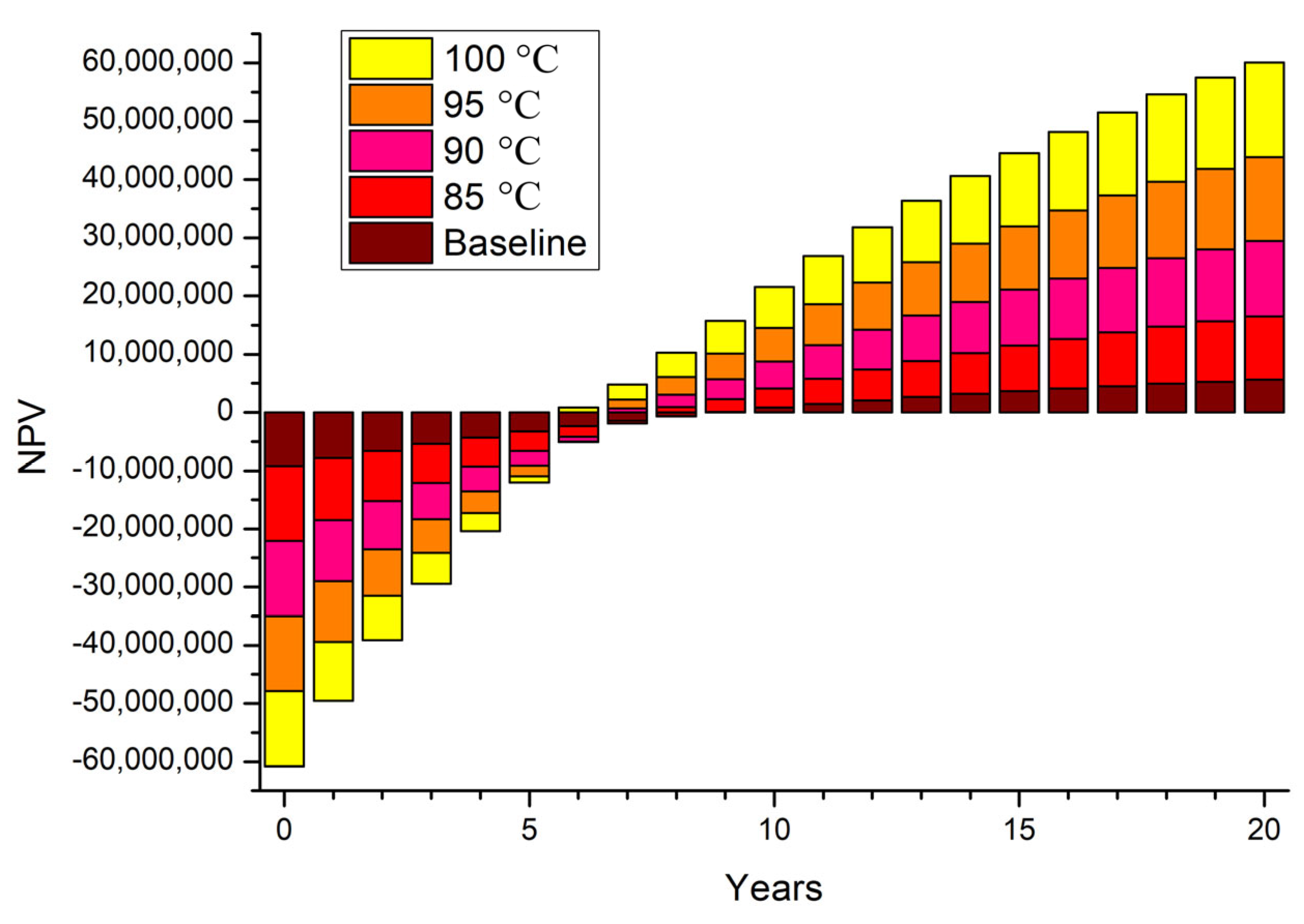

Figure 12 illustrates the long-term techno-economic performance of the ORC–ejector system by means of evaluating the net present value (NPV) over a 20-year period for intercooler temperatures of 16 °C, 18 °C, 20 °C, and 22 °C. All scenarios start with a negative NPV at year zero due to high initial capital costs, consistent with typical ORC investment behavior reported in the literature [

1,

34]. As the operation continues, annual revenues from power generation accumulate, and the NPV becomes positive, marking the start of economic recovery. Lower intercooler temperatures significantly improve profitability. The 16 °C case achieves the shortest payback period (about 6 years), followed by 18 °C (about 7 years) and 20–22 °C (about 8 years). Superior economic performance at lower intercooler temperatures aligns with thermodynamic trends: a reduced intercooler temperature increases the temperature gradient at the condenser, strengthens heat transfer, and improves the expander shaft power [

8,

17]. This increase in the mechanical output directly leads to higher annual electricity sales and faster capital recovery.

By year 20, the 16 °C configuration achieves the highest NPV, followed by 18 °C, 20 °C, and 22 °C. All ORC–ejector configurations outperform the baseline ORC without ejector integration, which has a delayed payback period of about 10 years. Similar improvements in economic feasibility have been reported in hybrid ORC + ECC and waste heat recovery systems [

6,

7,

28].

These results confirm that the intercooler temperature is a key factor affecting both thermodynamic and economic performance. Lowering the inlet temperature improves cycle exergy efficiency, reduces irreversibility at the condenser–ejector interface, and significantly increases long-term profitability, consistent with exergy–economic coupling principles in ORC systems [

21]. Optimal intercooler temperature selection is therefore critical for commercial viability in low-grade heat recovery ORC projects.

Figure 13 shows the economic performance of the ORC and ORC–ejector systems at generator temperatures of 85 °C, 90 °C, 95 °C, and 100 °C over a 20-year project. As with typical ORC investments, all scenarios start with negative NPVs due to initial capital costs [

1,

34]. As electricity sales increase, annual cash flows become positive, which in turn raises the NPV.

Higher generator temperatures significantly improve long-term profitability. The shortest payback period occurs at 100 °C (approximately 6 years), followed by 95 °C (approximately 7 years) and 90 °C (approximately 7–8 years). The slowest recovery is at 85 °C and in the baseline ORC, both reaching the break-even point at around year 8. This trend reflects the thermodynamic behavior discussed earlier: higher generator temperatures increase the pre-expansion specific exergy, enhance the expander work output, and improve the thermal-to-mechanical conversion efficiency [

7,

17]. The resulting increase in electricity production leads to stronger annual revenues and faster capital recovery. By year 20, the highest NPV is achieved at 100 °C, followed by 95 °C, 90 °C, 85 °C, and the non-ejector baseline. The growing gap between the 100 °C and baseline systems over time demonstrates the compounding financial benefits of higher generator temperatures. Similar improvements from high-temperature heat addition in ORC and ORC + ECC systems have been reported in recent thermo-economic studies on high-temperature preheating or geothermal-driven ejector cycles [

6,

28,

36].

Overall, the results confirm that the generator temperature is a key factor in the economic feasibility of ORC–ejector systems. Higher generator temperatures provide greater exergy input, increased mechanical output, and improved annual profit margins, which align with exergoeconomic principles linking component irreversibilities to system-wide cost performance [

21,

39]. Therefore, adopting higher generator temperatures significantly enhances both the economic sustainability and long-term investment viability of ORC-based power generation systems.

To clarify the economic and technical benefits of the ejector-assisted ORC, we conducted a detailed analysis linking cost trends to system thermodynamics. The observed improvements in the NPV and reduced payback periods in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 result from the ejector subsystem’s thermodynamic advantages. By lowering the condenser pressure and increasing the expander pressure ratio, the ejector enhances the shaft work output, which boosts annual electricity revenue and accelerates capital recovery. These results align with previous studies identifying the condenser backpressure as a key factor in ORC profitability [

1,

17]. Moreover, at lower intercooler temperatures, the ejector subsystem extracts more secondary flow, reduces heat release losses, and improves heat source utilization in the generator and pre-expansion stages. This increases thermal efficiency and net electricity generation. Similar economic gains from ejector-based cooling have been reported in hybrid ORC + ECC systems [

6,

9]. Consequently, the ORC + ECC consistently achieves higher annual cash inflow and a shorter payback period than the standalone ORC. From an investment perspective, the NPV analysis demonstrates that ORC systems are economically sensitive to thermodynamic improvements. The lowest intercooler temperature (16 °C) yields the highest cumulative NPV by maximizing power output and minimizing internal irreversibilities. This pattern matches findings in the literature, where greater exergy availability leads to improved cost-effectiveness [

34,

39]. Conversely, higher intercooler temperatures reduce the temperature lift and exergy input, weakening revenue and extending payback periods.

Overall, the economic advantage of the integrated ORC + ECC system stems from a combination of the following: (i) a higher net power output from reduced condenser pressure, (ii) improved heat source utilization and less destruction at low intercooler temperatures, and (iii) increased annual revenue from electricity generation. Together, these factors confirm that ejector-assisted operation is both more profitable and technically superior to the conventional ORC.

The long-term economic performance of the ORC + ECC shows a clear dependence on the generator temperature, which directly governs the second-law behavior of the cycle. As the generator temperature increases from 85 °C to 100 °C, the exergy supplied to the expander increases, while the internal irreversibilities decrease, yielding a higher useful work output. This thermodynamic enhancement translates into higher annual electricity revenue and a faster capital recovery.

At 100 °C, the system achieves the highest NPV with a payback period of approximately six years, followed by 95 °C (year 7), 90 °C (years 7–8), and 85 °C, which approaches the baseline system in both return magnitude and recovery time. These results indicate that an insufficient heat source temperature of 85 °C limits the exergy available to the expander, reducing economic benefits despite the presence of the ejector subsystem.

From a second-law perspective, higher generator temperatures enhance the exergy efficiency of heat addition, reduce the relative exergy destruction in both the boiler and the expander, and increase the specific shaft work delivered to the expander. These results are consistent with observations from recent ORC + ECC studies, where improved exergy quality at the heat source boundary was shown to be a key determinant of cost-effective electricity generation. Likewise, the beneficial trend aligns with Yang et al. [

40], who demonstrated that higher expander pressure ratios driven by higher inlet temperatures directly strengthen the thermodynamic driving force and improve overall cost-effectiveness.

The exergoeconomic interpretation further clarifies this relationship: higher generator temperatures reduce the unit exergy cost of power cw by lowering avoidable exergy destruction in the expander, while the ejector subsystem suppresses condenser-side irreversibilities, thereby reducing cost contributions from the cooling tower and condenser. As the generator temperature increases, the exergoeconomic factor fk for high-impact components shifts in a favorable direction, indicating that a greater share of useful work is obtained per unit of capital-related cost. These combined second-law and exergoeconomic mechanisms provide strong evidence that the generator temperature is a dominant driver of long-term profitability for ORC + ECC under tropical operating conditions.

Consequently, higher generator temperatures strengthen both thermodynamic and cost-based performance, resulting in a significantly higher NPV over 20 years compared to the baseline ORC.

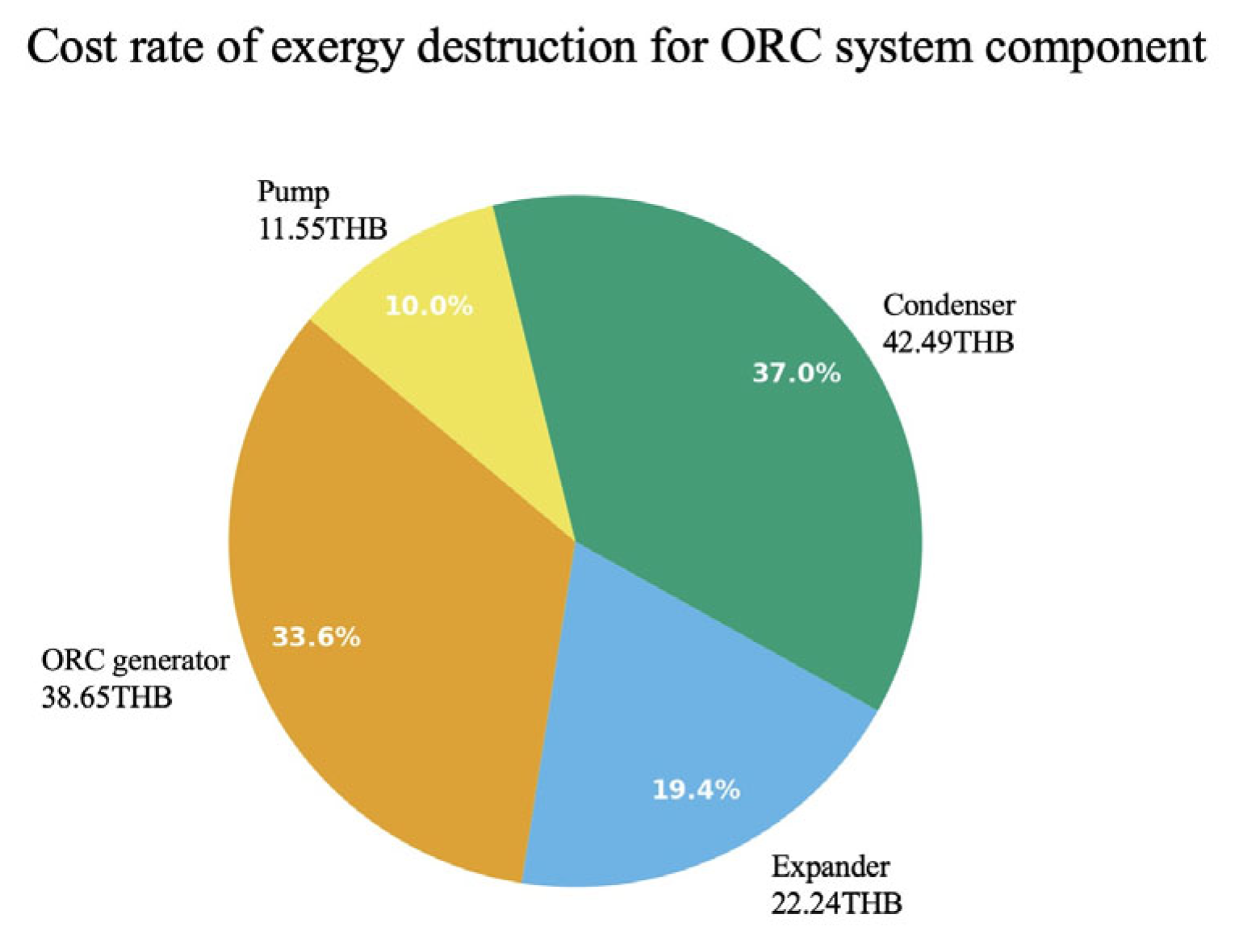

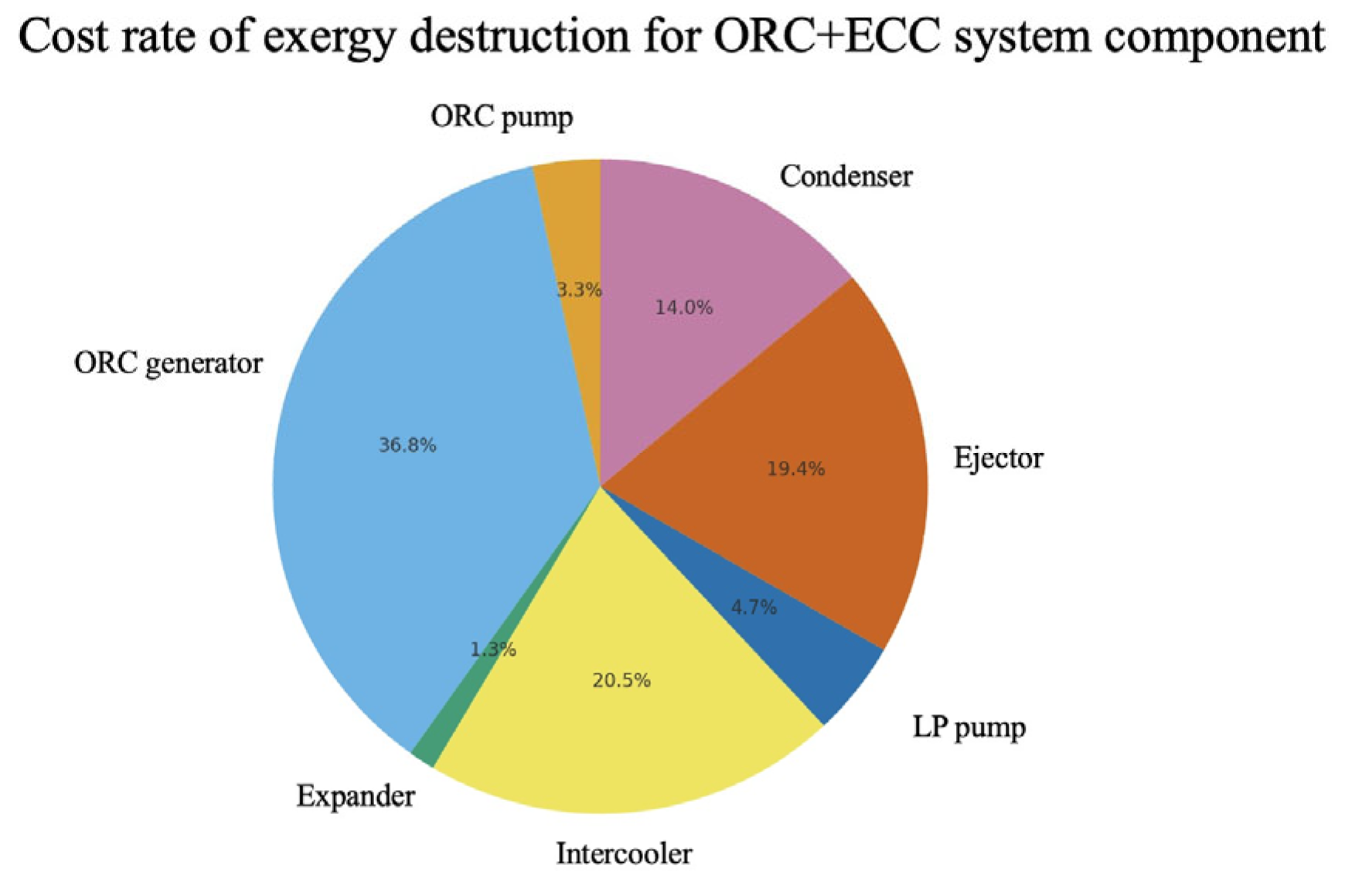

From the calculated costs, the exergy-destruction cost of each component can also be determined under the chosen reference parameter values.

Figure 14 and

Table 10 show that the generator has the highest exergy-destruction cost, followed by the condenser [

41].

The high exergy-destruction costs of the generator and condenser are mainly due to their significant exergy-destruction rates. In contrast, the pump’s cost is primarily driven by high fuel expenses rather than exergy destruction.

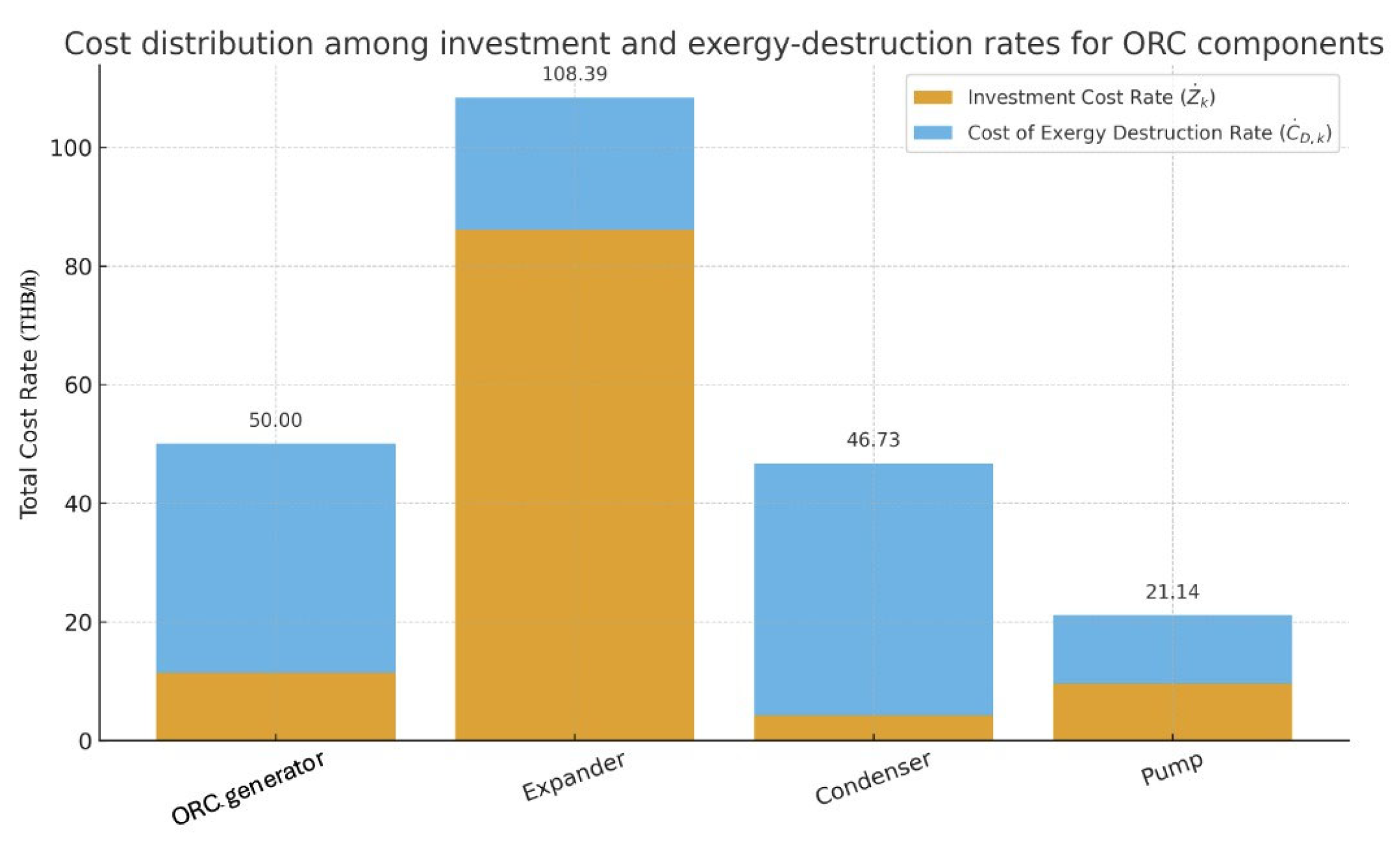

Before implementing any design or investment changes, we analyze the components with consideration given to the cost distribution, exergoeconomic significance, and how efficiency improvements affect the total investment cost.

Figure 15 illustrates the distribution between investment costs and exergy destruction.

From an exergoeconomic perspective, the expander should be prioritized because it has the highest combined investment and exergy-destruction costs. The exergoeconomic factor assesses the relationship between the exergy efficiency and investment cost for these components.

Table 11 presents the values for each component.

When analyzing the system components by considering both the investment cost rate and the exergy-destruction cost rate, the expander was found to have the highest total cost compared to the other components of the system. This outcome is primarily attributed to its significantly higher investment cost, as shown in

Table 12.

Following the expander, the generator and condenser exhibited the next highest combined investment and exergy-destruction costs, with total costs of 50.00 and 46.73 THB/hr, respectively. In contrast to the expander, both components exhibit a high exergy-destruction cost rate (), with the generator at 77.3% and the condenser at 90.9%, representing a higher proportion than the investment cost rate ().

For the pump, non-exergy-related costs and the total costs of components are divided rather equally, indicating that the current investment costs of these components are reasonable. In contrast, generators and condensers are estimated to have low exergoeconomic factors (fk), indicating that cost savings from the exergy-destruction cost rate () in these components should be considered to reduce exergy losses and improve overall system efficiency.

Meanwhile, for pumps, improving component efficiency is more economically feasible, even if it results in an increased equipment investment cost.

The exergy costs for each stream in the ORC + ECC system is depicted in

Figure 16 which shows how the unit cost and cost flow are distributed by the exergy rate. Streams 2, b, and h have the highest costs, identifying the condenser and cooling tower as key points in the cost distribution due to their large heat transfer requirements. Streams with a high unit cost but low exergy, such as Streams 6 and g, illustrate the secondary role of sub-flows from the intercooler and ejector in the overall cost structure. Streams 3 (c = 0) and 5 (c = 0.003) have very low unit costs, as exergy transfer here does not add significant cost. However, these streams are still necessary to maintain the balance equations in the SPECO method.

Unit costs (c) across streams vary significantly, from 0.0 to 2.03 THB/kWh. This aligns with Tsatsaronis and Winhold (1985) [

26], who found that systems with multiple heat transfer circuits, such as the ORC + ECC, naturally produce cost imbalances in streams related to heat dissipation. Recent exergoeconomic studies [

31] also confirm that heat exchangers are central to economic optimization due to their capital costs and influence on system performance.

Therefore, the condenser and cooling tower emerge as the highest-cost sources in ORC + ECC systems. They should be prioritized for design improvements, such as enhancing heat exchange efficiency, reducing exergy destruction, and developing advanced cooling water management strategies, to reduce the overall system cost [

12,

42,

43].

The ORC + ECC demonstrates significant exergoeconomic potential in both the investment cost rate () and the exergy-destruction cost rate ().

For a standard ORC (shown in

Table 11), the expander has the highest total cost at 108.4 THB/hr, primarily due to investment rather than exergy destruction. This aligns with Rosen and Dincer (2003) [

41], who noted that the expander often dominates ORC system costs because of its high price and ongoing maintenance. The condenser (46.7 THB/hr) and generator (50 THB/hr) also contribute significantly, but their costs are mainly driven by exergy destruction [

1,

12,

27].

For the ORC + ECC system (shown in

Table 13 and

Figure 17), the cost structure shifts, with the cooling tower (approximately 139.6 THB/hr) and condenser (approximately 132.5 THB/hr) incurring the highest total costs, mainly from exergy destruction. This is especially notable in circuits requiring significant heat exchange with cooling water. The generator (approximately 117.5 THB/hr) also shows substantial economic losses due to exergy destruction, supporting Tsatsaronis and Winhold (1985) [

26], who identified heat exchangers as a common source of exergy cost in energy systems [

12,

42,

44].

Incorporating an ejector cooling cycle (ECC) can enhance waste energy utilization and operational flexibility. However, it also increases exergy-destruction costs in heat transfer equipment, especially condensers and cooling towers. Future ORC + ECC system designs should focus on improving the thermal and exergy efficiency of heat exchangers and implementing advanced cooling water management to reduce overall system costs [

10,

18,

26,

41].

5.4. LCOE Sensitivity Analysis

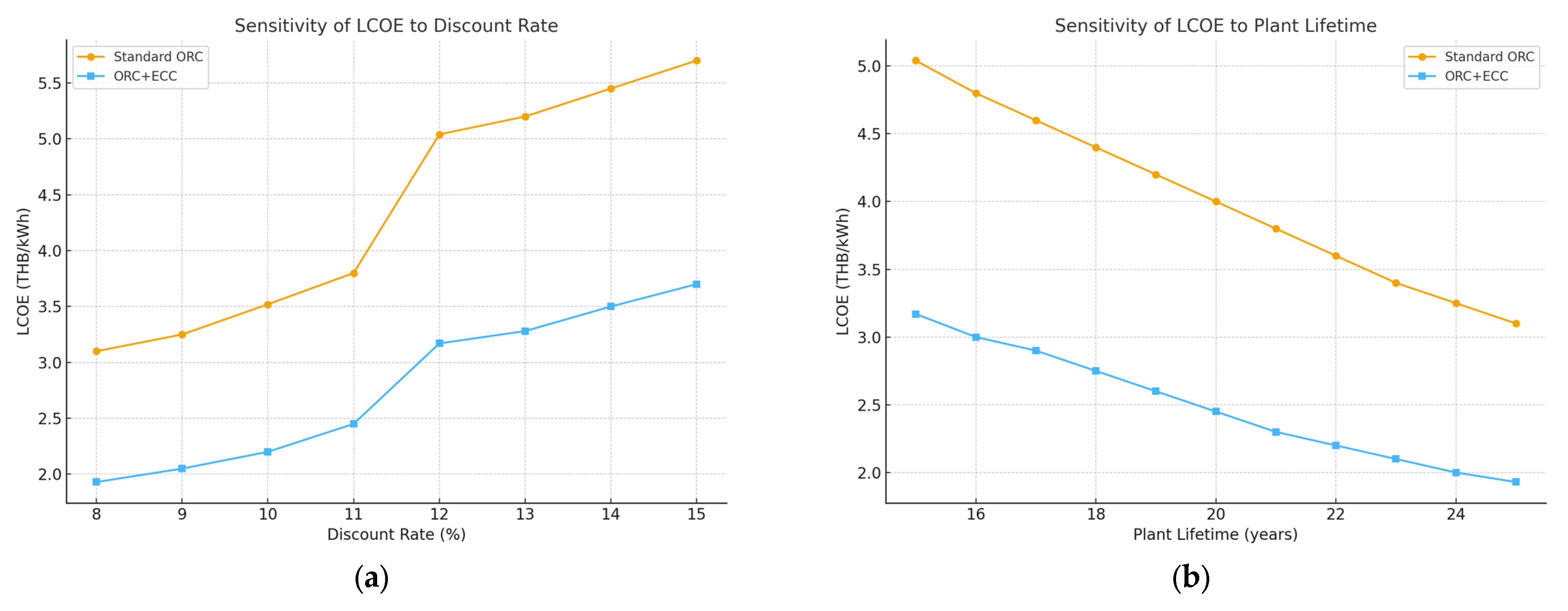

The sensitivity analysis of the LCOE in relation to discount rates and plant lifetimes are shown in

Figure 18. They revealed similar trends for both the standard ORC and ORC + ECC systems. As discount rates increased from 8 to 15 percent, the LCOE rose for both systems, highlighting the impact of financial costs. The ORC + ECC system consistently maintained a 35 to 40 percent lower LCOE than the standard ORC, with this advantage growing at higher discount rates. This demonstrates that the ORC + ECC provides greater economic flexibility in challenging financial environments.

For plant lifetimes of between 15 and 25 years, the LCOE for both systems declined as the investment costs were spread over longer periods. The ORC + ECC system showed a greater reduction, reaching an LCOE of below 2.0 THB/kWh under favorable conditions, compared to approximately 3.1 THB/kWh for the standard ORC. This demonstrates that the ORC + ECC offers both improved thermodynamic integration and long-term economic sustainability.

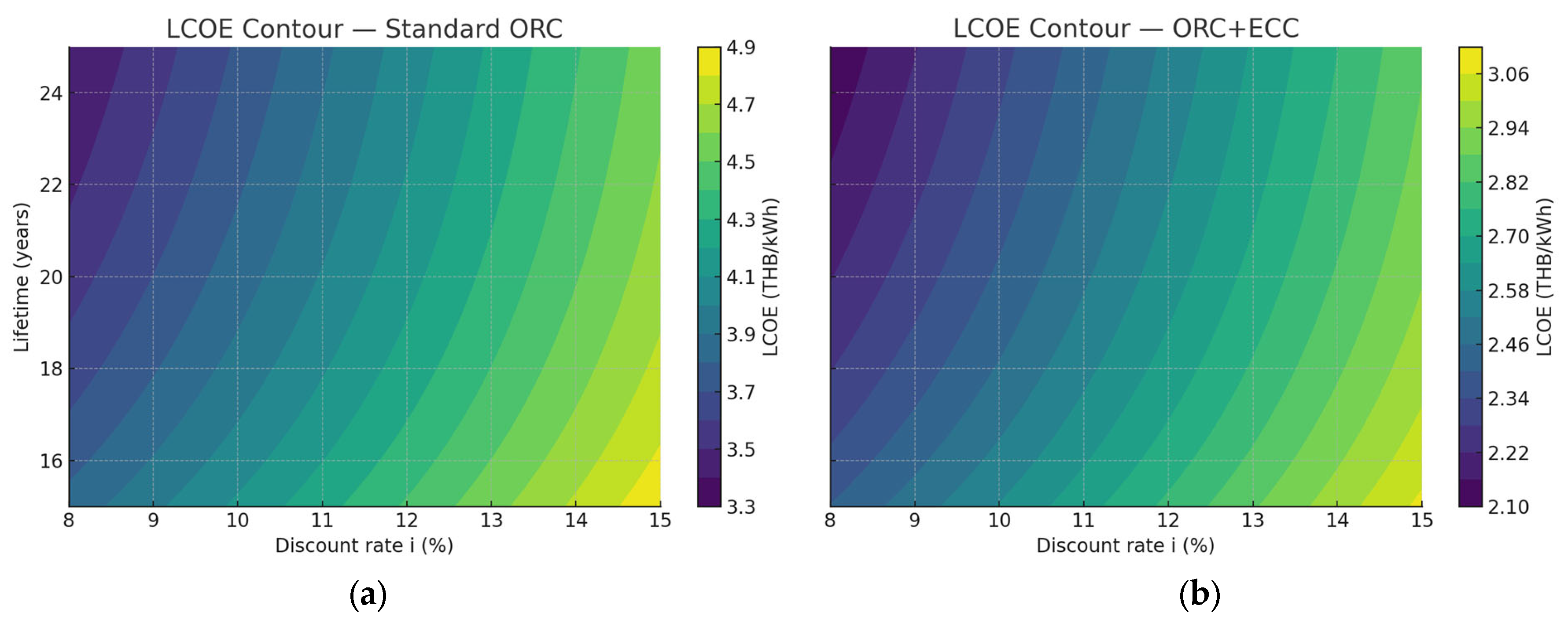

These sensitivity analyses are also presented by the contour plot as shown in

Figure 19. The contour plots confirm that the ORC + ECC consistently outperforms the standard ORC across all financial scenarios, especially at higher discount rates and for longer lifetimes. This underscores the strong potential of the ORC + ECC for waste heat power generation, particularly in hot and humid climates where cooling is a significant challenge [

12,

18,

26,

41,

42,

44].

The levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) shown in

Figure 20 is a key metric for assessing the economic feasibility of the proposed ORC + ECC. With a total investment of THB 12.90 million, a 20-year lifespan, and a 15% discount rate, the system’s annualized cost is approximately 2.84 million THB/year, excluding fuel costs. This increases to 3.06 million THB/year when accounting for the opportunity cost of waste heat.

Given the system’s net power generation capacity of 133.253 kW and operation at 8000 h per year, the total electricity generation amounts to 1,066,024 kWh annually. The calculated LCOE is 2.66 THB/kWh (excluding waste heat costs) and 2.87 THB/kWh (including waste heat costs), which is competitive compared to standard ORC systems reported in the literature, typically ranging from 0.08 to 0.12 USD/kWh (≈2.9 to 4.3 THB/kWh) under similar scales and operating conditions [

23].

Sensitivity analysis over 10- to 15-year project lifetimes at a 15% discount rate shows that both the standard ORC and ORC + ECC systems have a lower LCOE as the project life increases due to capital costs being spread over more years. The ORC + ECC system consistently achieves a lower LCOE than the standard ORC, regardless of whether the opportunity cost of waste heat is included. This highlights the economic advantage of the ORC + ECC in financially constrained scenarios and emphasizes the need for designs that optimize heat transfer and minimize exergy losses [

12,

26,

41,

42,

44].

The results indicate that, when waste heat is treated as a free energy source, the ORC + ECC can produce electricity at a cost lower than the average industrial electricity tariff in Thailand (≈3.3 THB/kWh). Even when the opportunity cost of waste heat is considered, the system remains competitive with the grid price, reflecting the strong economic potential of waste heat recovery technologies, particularly in tropical climates [

12,

41].

Furthermore, sensitivity to net power was observed: when the net power decreases from 160 kW to 133 kW, the LCOE increases from approximately 2.2 THB/kWh to 2.7 THB/kWh. This underscores the importance of optimizing exergy efficiency and minimizing irreversibilities in key components such as the generator and expander. Exergoeconomic studies have shown that these components are primary sources of exergy-destruction costs; thus, enhancing their thermodynamic performance directly increases the economic viability of the system [

27,

42,

44].