Abstract

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emission, caused by heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere, is a major driver of global warming. The World Economic Forum highlights rising emissions, ecosystem degradation, and climate-related disasters as long-term threats to global stability. The accurate modeling and prediction of GHG emissions are crucial for evidence-based climate governance. This study investigates Türkiye’s GHG emissions by comparing two advanced time-series models: a deep learning-based Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network and the Multi Deep Assessment Model (MDAM), which incorporates Caputo fractional derivatives. Data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat) and the Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation (TEIAŞ) were used covering the period between 1993 and 2022. These datasets include information on GHG emissions, fossil-based generation, renewable energy, and electricity demand. Both models were trained to predict 2030 emissions and assess the contributing factors. Results show that MDAM achieved superior accuracy compared to LSTM. Both models projected 2030 emissions above Türkiye’s 695 Mt target, with 721.87 Mt (MDAM) and 709.49 Mt (LSTM), highlighting the need for stronger policy action. A no-COVID scenario yielded higher forecasts, confirming the pandemic’s suppressive effect. Impact factor analysis revealed that domestic electricity demand and fossil-based generation are the strongest drivers, while renewables mitigate emission.

Keywords:

fractional calculus; LSTM; MDAM; ARIMA; greenhouse gas emissions; modeling; time series prediction 1. Introduction

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, caused by the release of gases that trap heat in the atmosphere, are one of the main environmental problems directly affecting global warming. Gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and fluorinated gases contribute to the greenhouse effect by entering the atmosphere naturally or through human activities, leading to imbalances in the climate system [1,2]. According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2025, the rise in GHG emissions, extreme weather events, and ecosystem degradation are among the most serious and long-term environmental threats [3]. To reduce the damage caused by GHG emissions, governments around the world are developing policies to lower emissions, aiming to minimize the effects of climate change, ensure economic stability, and provide a livable future. One of the key agreements in this context is the Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015 during COP21 (21st Conference of the Parties) and entered into force in 2016. The primary objective of the agreement is to limit global warming to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, ideally to 1.5 °C [4].

Türkiye ratified the agreement in 2021 and initially submitted an Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) to reduce emissions by 21% by 2030 [5]. Due to increasing energy demand, industrialization, and urbanization, this target was later revised. In 2023, Türkiye updated its commitment by setting a 41% reduction target and announcing 2038 as the national peak year for emissions [6]. The updated plan includes strategies for key sectors such as energy, industry, transportation, agriculture, and waste, aiming for net zero emissions by 2053. Achieving these goals increasingly requires reliable prediction tools to monitor progress, predict trends, and guide long-term planning. Therefore, the accurate modeling of emission trends has become a fundamental part of climate governance and evidence-based policy making.

Several studies have addressed GHG emissions both in Türkiye and globally. The report Türkiye’s Decarbonization Roadmap: Net Zero by 2050 by Şahin and colleagues discusses the necessary steps for Türkiye to achieve its net-zero emission targets under the Paris Agreement [7]. The report compares different emission scenarios and evaluates key strategies such as phasing out fossil fuels, transitioning to renewable energy, and improving energy efficiency. A study by Ayaz used machine learning techniques to analyze Türkiye’s CO2 emissions data from 1865 to 2023 and predict emissions through 2040 [8]. Among the models tested, the Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model achieved the highest prediction accuracy with an R2 score of 94.3%, followed by the LSTM model with 90.4%. The results predict per capita carbon emissions to reach 5.077 tCO2 by 2040.

Doganlar and colleagues analyzed the long-term impact of economic growth, financial development, and energy consumption on CO2 emissions in Türkiye. Using annual time-series data from 1965 to 2018, the study employed advanced econometric methods such as the RALS-EG (Residual Augmented Least Squares—Engle & Granger) cointegration test and Bootstrap causality analysis. The results indicate a unidirectional causal relationship from financial development to both economic growth and energy consumption, suggesting that financial expansion may increase environmental pressure. The study underscores the need for Türkiye to prioritize investments in renewable energy to enhance environmental quality [9].

Yurtkuran conducted a study to examine the effects of agriculture, renewable energy production, and globalization on CO2 emissions in Türkiye. Using data from 1970 to 2017, the Gregory–Hansen cointegration test and the Bootstrap ARDL model were applied. Additionally, long-term relationships among variables were analyzed using Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) and Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares (DOLS) estimators. The study employed the KOF Index of political, social, and economic globalization as independent variables to explore the environmental effects of globalization. The findings emphasize that to enhance environmental sustainability, Türkiye should improve the effectiveness of its renewable energy policies, adopt carbon-reducing practices in agriculture, and implement environmentally friendly regulations to guide economic growth [10].

The study conducted by Karaaslan and Camkaya analyzes the short- and long-term relationships between economic growth, healthcare expenditures, renewable and non-renewable energy consumption, and CO2 emissions in Türkiye. Using annual data from 1980 to 2016, the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) method and the Toda–Yamamoto causality test were applied. The main findings of the study indicate that, in the long term, economic growth (GDP) and non-renewable energy consumption (NREC) were found to increase CO2 emissions, whereas healthcare expenditures (HE) and renewable energy consumption (REC) contributed to reducing emissions. However, in the short term, only GDP and REC showed a positive relationship with CO2 emissions. The results of the Toda–Yamamoto causality test indicated a unidirectional causality running from GDP, HE, REC, and NREC to CO2 emissions. Furthermore, the study confirmed a direct long-term relationship between economic growth and CO2 emissions, underlining the necessity for Türkiye to strengthen its environmental sustainability policies. The study emphasizes the necessity of balancing economic growth and energy consumption for environmental sustainability. It recommends increasing investments in renewable energy and promoting energy efficiency policies in the healthcare sector. To reduce carbon emissions, Türkiye must reduce its dependence on fossil fuels and transition toward sustainable energy sources. This research serves as a significant resource for evaluating the environmental impacts of energy consumption, healthcare expenditures, and economic growth in Türkiye [11].

A study by Aykac Ozen aims to understand the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on GHG emissions. The research focuses on changes in natural gas consumption for heating and road transportation in the province of Samsun. By comparing the years 2019–2020 (pre-pandemic) and 2020–2021 (during the pandemic), the study analyzes how GHG emissions changed. The findings indicate a significant decrease in energy consumption, resulting in a 17.3 Gg reduction in total GHG emissions. Specifically, reduced natural gas use for heating prevented 8.16 Gg CO2-equivalent emissions, while reduced road transportation led to a 9.14 Gg CO2-equivalent decrease. The study demonstrates that changes in energy-intensive sectors such as heating and transportation can significantly reduce emissions even in the short term [12].

Deng and colleagues developed a machine learning-based approach to estimate fossil fuel-related CO2 emissions in G20 countries following the COVID-19 pandemic. Their results suggest that by 2030, fossil fuel-based CO2 emissions will be 10.1% to 17.7% lower than pre-pandemic projections [13].

A 2021 study by Xie and colleagues proposed a novel model for predicting carbon emissions that outperforms traditional methods. The model, named the Conformable Caputo Fractional Gray Bernoulli Model (CCFNGBM(1,1)), incorporates fractional derivatives and demonstrates high accuracy in prediction CO2 emissions based on energy consumption. The model’s parameters were optimized using the Gray Wolf Optimizer (GWO) algorithm, and China’s emissions were predicted through 2023. This new model achieved lower error rates than conventional prediction techniques such as ARIMA, Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and the traditional Gray Model (GM). According to the findings, fractional calculus-based approaches can offer powerful tools for time-series prediction. This study provides valuable insights for policymakers seeking to better model carbon emissions and support energy policies with scientific evidence [14].

Today, the LSTM model is widely used in various fields such as time-series predicting, natural language processing (NLP), speech recognition, and biomedical data analysis [15,16,17]. Examples from the literature include its application in prediction economic indicators such as GDP, inflation, and exchange rates [18,19,20]; in machine translation, text summarization, and sentiment analysis [21,22,23]; in the analysis of EEG and ECG data for the detection of neurological disorders [24,25]; and in the prediction of greenhouse gas emissions and analyzing climate change [10,26,27,28].

Fractional calculus, which allows the definition of derivatives and integrals of non-integer order, has recently gained widespread attention across various disciplines of science and engineering including chemistry, biology, biomedical devices, nanotechnology, finance, and economics [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Fractional calculus is an effective method for modeling and prediction, as its memory property enables the presentation of long-term dependencies and historical effects within complex systems. In our previous works, we developed several fractional calculus-based mathematical models and compared their performance with both traditional modeling techniques [35,36,37,38] and the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model [20,40,41]. In our previous studies, the fractional calculus (FC) approach was employed to address various modeling and prediction problems in different scientific and engineering domains. In the early works, fractional differentiation was used to model datasets such as children’s physical growth parameters and telecommunication sector indicators—including mobile and fixed broadband subscriptions, revenue ratios, and investment dynamics—through FC-based models. These models achieved lower error rates compared with classical linear and polynomial approaches [35,36,37,38].

Subsequently, the Deep Assessment Methodology (DAM) was developed in conjunction with fractional calculus to model complex datasets such as countries’ gross domestic product per capita, COVID-19 cases, and air transportation data, achieving highly accurate and long-memory predictions [39,40,41]. The original DAM model was designed as a single-input structure; later, it was extended into a multi-input deep assessment model (M-DAM). This extended version demonstrated strong performance when applied to complex systems such as macroeconomic indicators and air transportation data, and its results were benchmarked against both fractional calculus-based models and the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model [20].

Collectively, these studies reveal that fractional-order modeling provides a powerful and flexible mathematical foundation for analyzing nonlinear and long-memory processes, while also establishing the theoretical and methodological basis of the multi-input, fractional, and deep-assessment-based framework (MDAM) proposed in this study for greenhouse gas emission forecasting.

The current study investigates Türkiye’s GHG emissions by comparing two advanced time-series models: a deep learning-based Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network and the Multi Deep Assessment Model (MDAM), which incorporates Caputo fractional derivatives. Data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat) and the Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation (TEIAŞ) were used covering the period between 1993 and 2022. These datasets include information on GHG emissions, fossil-based generation, renewable energy, and electricity demand. Both models were trained to predict 2030 emissions and assess the influence of contributing factors.

In the next section, a problem formulation will be given for the modeling, prediction and impact factor analysis. The third section will include the results and figures of modeling, prediction, and impact factor analysis implementations. The fourth section presents a discussion of the results. The fifth and final section provides the conclusion, general evaluation, and future studies.

2. Materials and Methods

The selection of methods in this study was guided by the dual objective of comparing an advanced deep learning framework with a fractional calculus-based deterministic model, both capable of handling temporal dependencies and long-memory dynamics observed in GHG emission data.

The LSTM network was chosen for its proven capability to capture temporal dependencies and nonlinear patterns in sequential time series. Its internal gating mechanism allows it to retain information across long sequences, making it particularly effective for modeling emission trends influenced by historical energy demand and generation patterns.

The MDAM, on the other hand, represents an innovative fractional calculus-based approach that extends conventional differential operators into fractional orders, enabling it to express long-memory behavior and accumulation effects in complex systems. Unlike neural networks, MDAM provides a mathematically interpretable structure that connects past and current system states through fractional derivative coefficients.

To benchmark the performance of both advanced models, a traditional ARIMA (Auto Regressive Integrated Moving Average) model was also implemented. ARIMA was not intended to serve as a competing predictive model but rather as a reference baseline, included due to its well-established role in time-series forecasting. It was used to calculate and compare standard evaluation metrics such as MAPE, RMSE, and R2, allowing a transparent assessment of performance improvements achieved by the proposed LSTM and MDAM models.

Modeling, predicting, and impact analysis were conducted using the MDAM and LSTM methods. The operational mechanisms of the models are presented below.

2.1. M-DAM

2.1.1. MDAM Modeling

Based on the Single-Function Input Modeling approach, the Multi-Function Input Modeling System [20] incorporates additional factors that are considered to potentially contribute to the target variable. The -th factor to be modeled is expressed as shown in Equation (1).

Here, represents the factor being modeled, and refers to the weighted sum of a certain number of the function’s past values, with weights given by the coefficients , as shown in Equation (2).

In this case, Equation (1) is reformulated as Equation (3) below.

During this process, the fractional derivative order is denoted by . To solve the fractional differential equation in Equation (3), the Laplace transform is applied to convert the equation into an algebraic form. The properties of the Laplace transform for the Caputo derivative are utilized in solving the equation [20]. is the Laplace transform of .

Here taking the inverse Laplace transform of Equation (5) yields

is obtained. The modeling of any given factor is carried out using Equation (6), where the unknown coefficients are estimated using the least squares method [20]. The most critical aspect is that the fractional order varies between 0 and 1, and the goal is to determine the optimal value of that minimizes the modeling error. In this way, the coefficients and the fractional order that yield the lowest error rate are obtained.

It is better to give an example of how to obtain .

Then

This leads to having a system of linear algebraic equations (SLAE). Taking Equations (7)–(11) into account, a total of equations are derived. By identifying the values of and that minimize the error, the modeling process is completed [20].

The continuous function is obtained with the optimal fractional order within the interval (0, 1) to achieve minimum modeling error. Initially, the fractional order is set to 0, and it is incremented by 0.01 in each iteration to determine the optimal value. Once the optimal fractional order is determined, the unknown coefficients of the model are calculated. The error rate is calculated with the modeling of data and real data . Subsequently, the error value is computed, analyzed, and compared with previously obtained results. If the new error is smaller than the previous one, the corresponding fractional order is recorded. Ultimately, the optimal fractional order corresponding to the best model fit is identified, and the associated coefficients specified in Equation (6) are calculated.

In this study, the GHG emissions, fossil-based generation, renewable energy, and electricity demand data of Türkiye were used, covering the years between 1993 and 2022 [39]. The dataset is shown in Table A1. The model was trained to predict 2030 emissions and assess the influence of contributing factors.

Here,

(years): [1993, 1994, …, 2022].

(points): [1, 2, …, 30].

: [1, 2, 3, 4].

(value of ): [].

GHG emission, fossil-based generation, renewable energy, and electricity demand.

GHG emission.

: It shows the actual data of each factor in each year. For example, is the GHG emission of Türkiye in 2012, when , and 1.

: It stands for the number for each year. For example, for 1993, for 1995, and for 2022.

2.1.2. MDAM Impact Factor Analysis Model

For the impact factor analysis, the coefficients sought in Equation (12) are the values of . In this equation, the coefficients and were obtained from Equations (7)–(11). The unknowns are the values from Equation (6).

Here, the expression is defined as follows:

Here, our objective is to estimate the coefficients using the least squares method. Each factor is represented by , and its corresponding lag (past value) is denoted by . In this way, the influence coefficients of the factors affecting the variable to be modeled can be determined.

From the expression between Equations (12)–(15), a total of sets of equations are obtained, allowing the determination of the impact coefficient values [20]. Each input variable in MDAM is explicitly associated with fractional coefficients (), which mathematically represent the variable’s historical contribution within the fractional dynamic system. Specifically, the model generates a series of fractional weights over time, reflecting the long-memory and cumulative influence of each variable. The average of these coefficients was used to quantify the long-term impact of each variable, as shown in Equations (16) and (17).

: Weighted average impact factor

: Impact weight coefficient of the r-th function corresponding to its k-th lag

: Number of lagged (past) values considered

For instance, when , the data for the years 2019, 2020, and 2021 are used to perform the impact analysis for 2022.

: Represents the r-th function or factor.

2.1.3. MDAM Prediction Model

Any modeled factor (m = 1, 2, …, r) can be expressed for a desired time point and its historical values as follows:

Here, .

Equation (17) is rewritten as shown in Equation (18). From Equations (16) and (17), a total of equations are obtained. These equations are transformed by continuing the previously applied procedure, and the values of are determined using matrix solutions. To predict the future value of any desired factor, the first equation of the system defined in Equation (18) can be used [20].

From Equations (19)–(21), a total of equations are obtained; one of the equations is as shown in Equation (22). Subsequently, these equations are transformed into the matrix equation, and a matrix solution is applied to compute the coefficients [41]. Once these coefficients are obtained, any desired factor for the forthcoming period can be predicted using the first equation of the system (22). In other words, by substituting the relevant variable into the function, the value of the next step can be estimated.

2.2. LSTM

One of the deep learning-based models, LSTM, stands out for its ability to learn long-term dependencies in time-series data. This section discusses the fundamental structure and functioning of the LSTM architecture.

A study by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber introduced the LSTM architecture to overcome the limitations of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) in learning long-term dependencies. It was shown that conventional RNNs fail to address the problems of vanishing and exploding gradients during backpropagation, and LSTM was proposed as a novel approach based on gating mechanisms to solve these issues.

In the methodology used in the study, LSTM cells were developed to capture long-term dependencies in time-series data. LSTM includes memory cells and three main gating mechanisms (input gate, forget gate, and output gate), allowing information to be retained over extended periods and updated when necessary. These gate mechanisms control the flow of gradients, preventing the vanishing gradient problem and facilitating learning over long sequences.

Unlike traditional RNNs, LSTM can preserve dependencies across long time intervals. Experiments on synthetic datasets have demonstrated that LSTM learns more successfully and efficiently than other recurrent architectures. LSTM has been shown to be applicable in various fields, including speech processing, handwriting recognition, and time-series predicting. In particular, it exhibits significantly improved learning performance compared to classical RNN methods, which are highly sensitive to the vanishing gradient problem [42].

2.2.1. The Working Principles of LSTM Networks

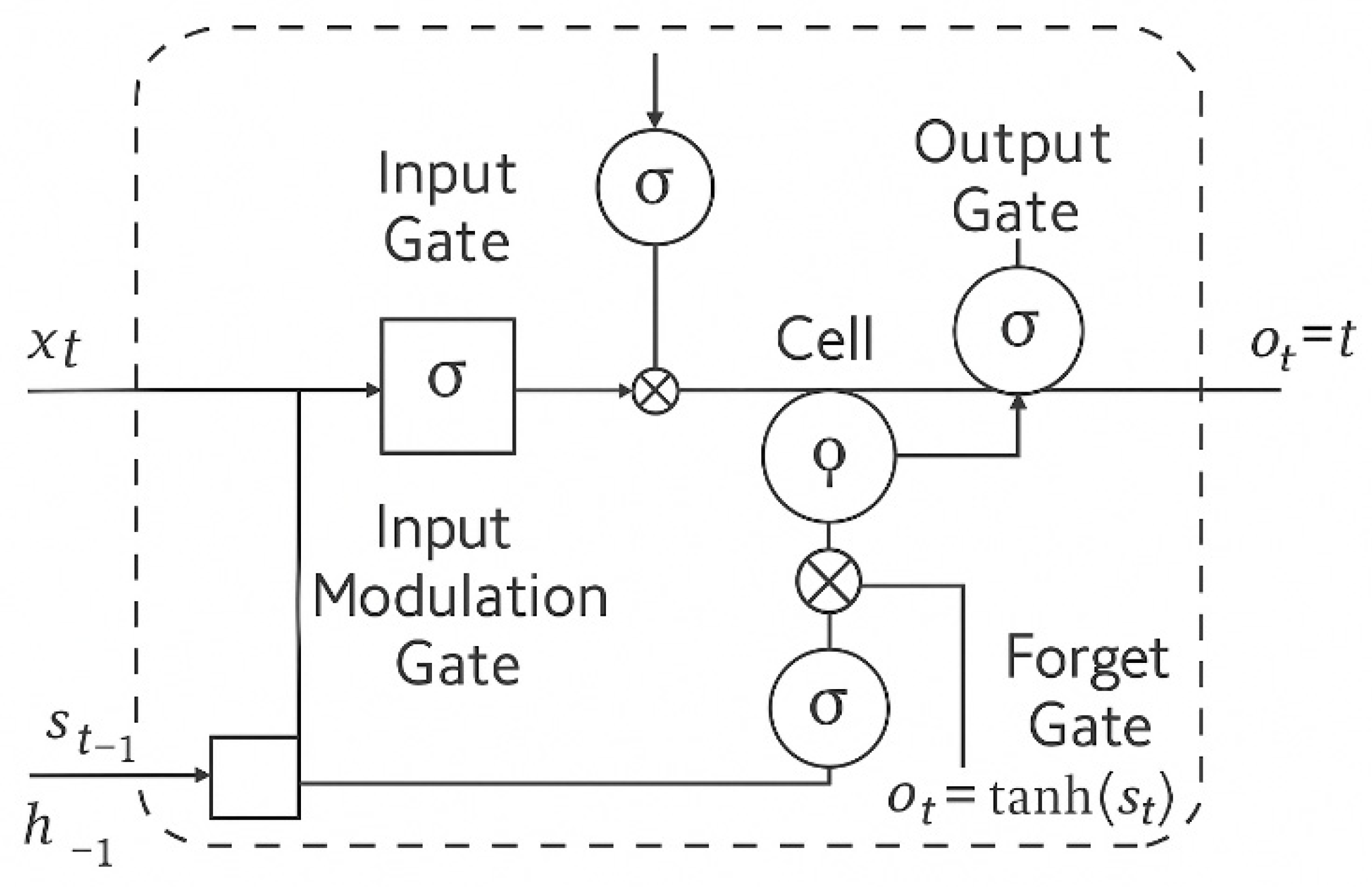

The fundamental distinction of LSTM lies in its ability to control the flow of information through gating mechanisms. An LSTM cell consists of the following core components in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the LSTM model.

At each time step, an LSTM cell receives two main inputs: the current input vector and the hidden state from the previous time step. These two pieces of information are combined and serve as the basis for the computations in all the gates (forget, input, and output) within the cell. The core components that enable the LSTM to preserve context over time operate on this dual input. When the gate output is close to 1, the information is retained; when it is close to 0, the information is disregarded [42].

The forget gate determines which parts of the long-term memory in the cell should be discarded. It operates using a sigmoid activation function, producing values between 0 and 1 that act as multipliers on the previous cell state. If the output is close to 1, the information is retained; if it is close to 0, the information is forgotten allowing the LSTM to effectively eliminate irrelevant data from memory [42].

The input gate controls the extent to which new information is incorporated into the cell. It consists of two components: the first determines which parts of the incoming information are important, and the second defines the content of the candidate cell state based on the input. These two components are multiplied element-wise to form the new information that will be added to the cell state [42].

The cell state represents the memory of the LSTM and serves as the core structure for storing long-term information. It is updated through the sum of two main components: the first is the portion controlled by the forget gate, which determines how much of the previous cell state is retained; the second is the portion managed by the input gate, which determines how much of the new information is added. Through this interaction, the LSTM is able to preserve previous knowledge while simultaneously integrating new information [42]

The output gate determines the current output of the cell. First, the output gate value oto_tot is calculated using a sigmoid activation function. Then, the cell state is transformed using the tanh activation function and multiplied by oto_tot. This process allows for short-term inference while also passing information to the next LSTM cell—producing an output and simultaneously updating the network’s memory [42].

2.2.2. Impact Factor Analysis and Prediction with LSTM

The LSTM architecture not only learns patterns in time-dependent data but can also implicitly capture the effects of multiple integrated variables on the target variable. To more clearly reveal the direction and magnitude of these effects, a linear regression-based factor analysis is conducted after the model training process. Within this analysis, the impact of each independent variable included in the model on the dependent variable is examined individually, and these effects are evaluated as either positive or negative based on the sign and magnitude of their corresponding coefficients.

The independent variables provided as inputs to the LSTM model are directly used as factors. Since these factors may exist on different scales, they are first normalized and then incorporated into a multiple linear regression model. The regression coefficients are calculated, and based on their signs and magnitudes, each factor’s effect on the dependent variable is interpreted as either positive or negative [42].

3. Results

This study investigates advanced methods for modeling and predicting GHG emissions. A deep learning-based time-series model LSTM is compared with the Multi Deep Assessment Model (MDAM), which is based on Caputo fractional derivatives. While LSTM is highly effective in capturing long-term patterns in time-series data, MDAM has the advantage of modeling long-term dependencies more accurately by extending differential and integral operators to fractional orders [14,28].

The analysis was conducted using data from the TurkStat on GHG emissions from 1993 to 2022, and additional data from TEIAŞ including electricity generated from fossil fuels, electricity generated from renewable sources, and total domestic electricity demand [39]. Both models were trained using this data, and 2030 GHG emission predictions were produced, along with coefficient estimates showing the influence of other factors on emissions. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emission trends was also analyzed. The codes for LSTM and M-DAM modeling, prediction, and impact-factor analysis, implemented in MATLAB R2023b and Python 3.10 (PyCharm 2023.3 IDE), are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

3.1. Modeling and Prediction Results with MDAM and LSTM

In this study, Türkiye’s GHG data from 1993 to 2022 were modeled using both MDAM and LSTM approaches, and forward-looking emission projections were generated. In the model, GHG emissions were used as the dependent variable, while energy demand, renewable energy production, and fossil fuel-based electricity generation were employed as independent variables.

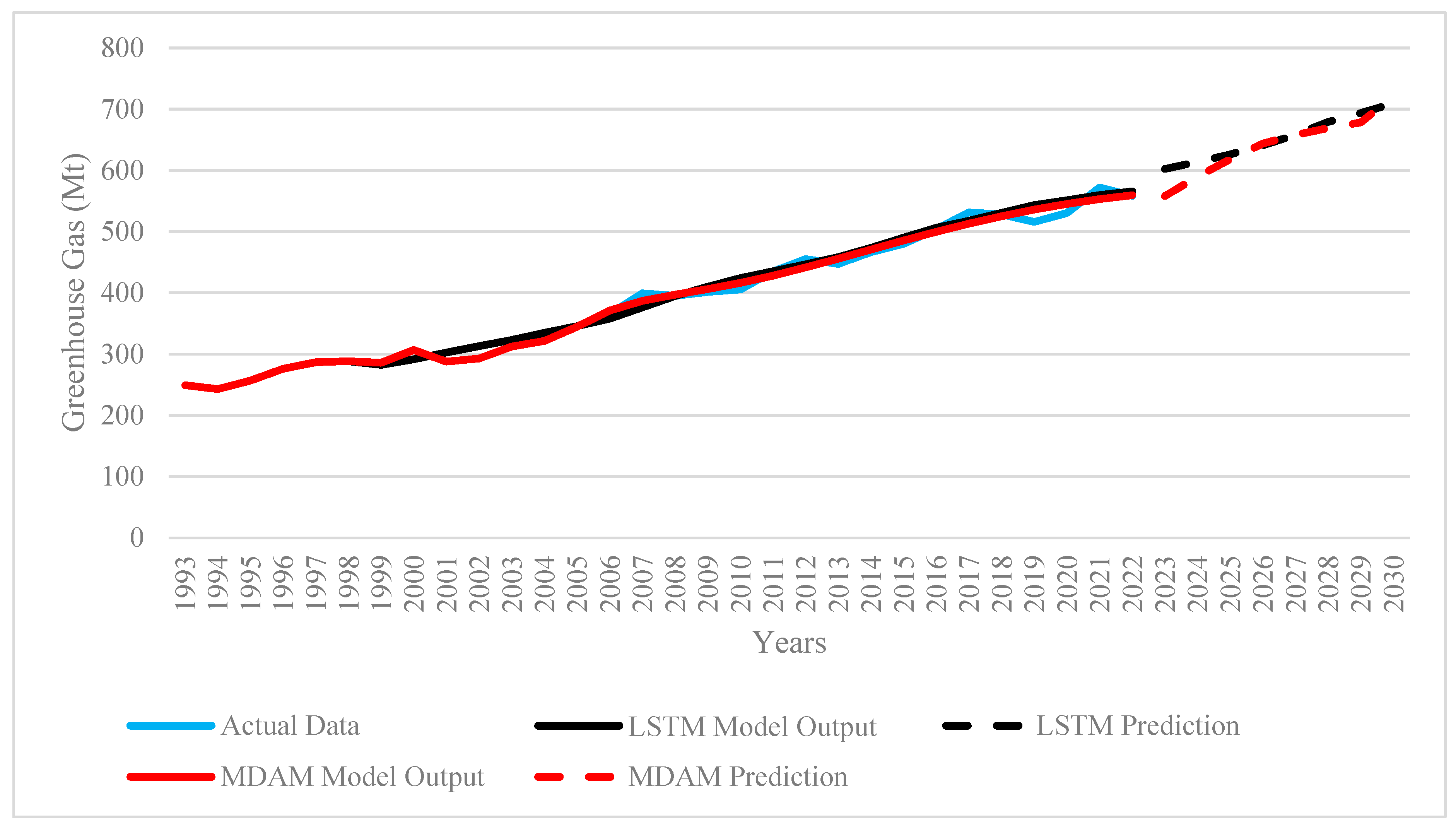

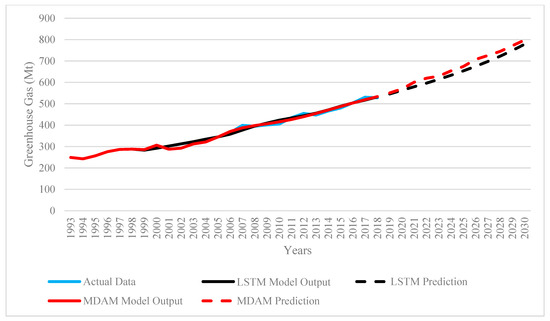

During the modeling process with MDAM, the memory length (l), which represents the influence of past data, was set to 10. This value, along with all other parameters, was optimized based on the lowest error rate relative to the dataset size. The optimal fractional order (ν) determined within the fractional calculus-based MDAM approach was 0.89, suggesting that emissions are strongly influenced by past trends and exhibit a high degree of memory effect. The predicted GHG emission level for 2030 using this model was found to be 721.869 kt CO2 equivalent. When compared to Türkiye’s Paris Agreement commitment to reduce emissions to 695 Mt by 2030, this projection indicates the need to reinforce and sustain current climate policies (Figure 2). The findings point to the necessity of more decisive and structural policy actions to reduce GHG emissions.

Figure 2.

GHG emissions modeling and prediction results of the MDAM and LSTM.

The LSTM model was trained with a timestep value of 5, which yielded the lowest error rate and is commonly used in time-series analysis. The Exponential Linear Unit (ELU) was selected as the activation function, and the learning rate was set to 0.001. Similarly to the MDAM setup, these parameters were optimized based on the dataset size and the lowest observed error. This error rate indicates that while the LSTM model operates with reasonable accuracy, it offers lower precision compared to the MDAM model. On the other hand, the emission prediction produced by the LSTM model for 2030 was 709.49 Mt. This value exceeds Türkiye’s target of reducing emissions to 695 Mt under the Paris Agreement. Therefore, this analysis also underscores the importance of reinforcing Türkiye’s current climate policies to achieve the 2030 targets (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the results and Türkiye’s 2030 target commitment.

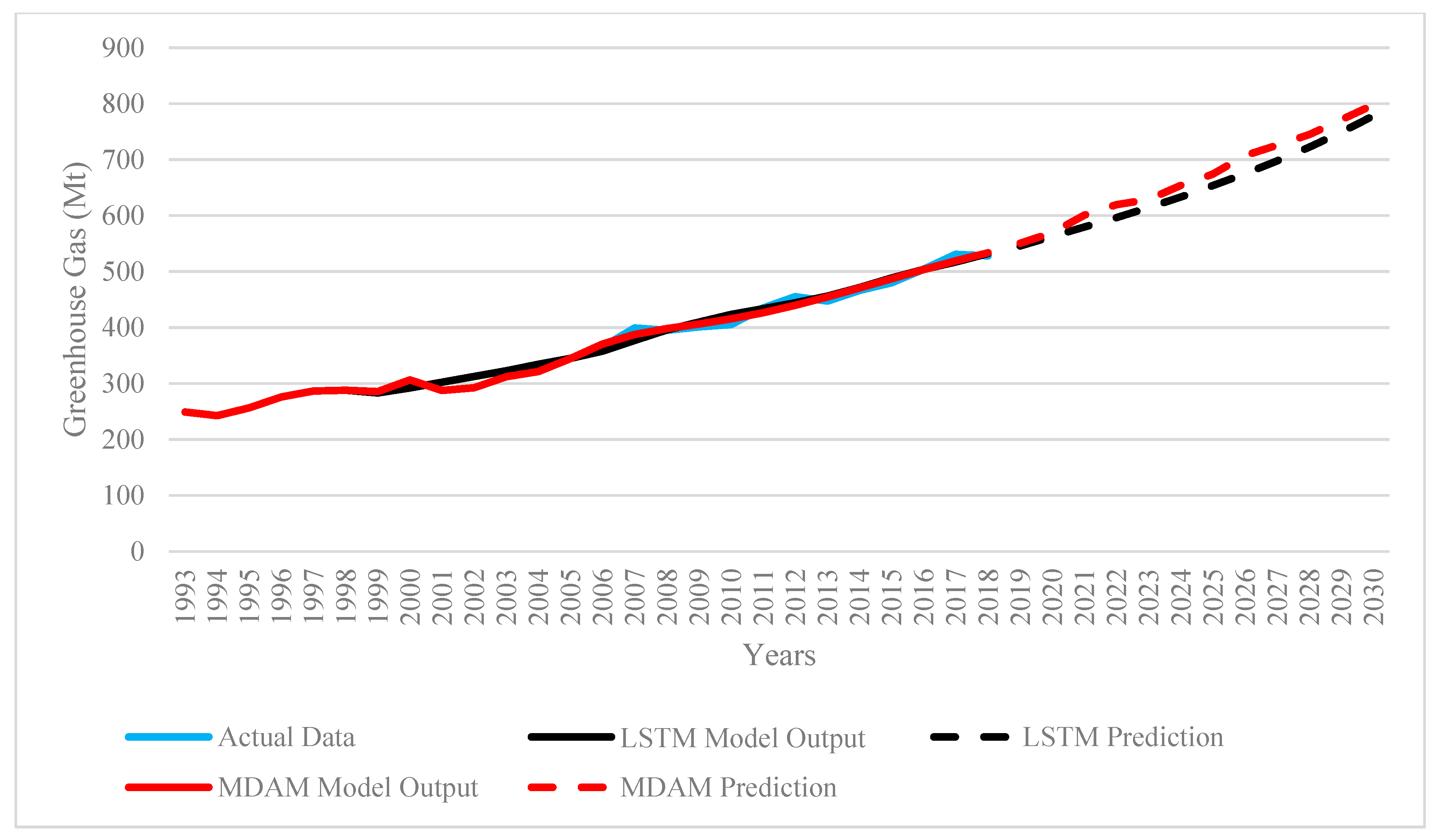

Additionally, when the models were trained using data from the 1993–2018 period to exclude the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2030 emission predictions increased to 798.14 Mt with MDAM and 778.28 Mt with LSTM (Figure 3). This finding indicates that the economic and industrial slowdown during the pandemic temporarily suppressed emissions, suggesting that the COVID-19 period can be interpreted as a natural experiment [12,13].

Figure 3.

GHG emissions modeling and prediction results of the MDAM and LSTM excluding COVID impact.

In addition to the MDAM and LSTM, and ARIMA model was implemented solely as a reference baseline to provide a comparative statistical benchmark. Unlike LSTM and MDAM, ARIMA was not employed for forward prediction, but rather to evaluate the relative performance of the proposed models. The models’ accuracy was evaluated using standard performance metrics such as Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and the coefficient of determination (R2).

MDAM achieved the lowest MAPE of 1.64%, an RMSE of 10.08, and an R2 of 0.9828, indicating excellent model accuracy and stability in reflecting long-memory dynamics. The LSTM model followed with a MAPE of 2.69%, RMSE of 13.06, and R2 of 0.9794, confirming its strong performance in capturing nonlinear temporal dependencies.

The ARIMA baseline, despite not being optimized for predictive use, recorded a MAPE of 2.78%, RMSE of 12.66, and R2 of 0.9835, validating its consistency as a bench-mark model while demonstrating that both advanced approaches, particularly MDAM, achieved superior accuracy. These results collectively confirm the advantage of integrating fractional dynamics and deep learning architectures for the precise modeling of Türkiye’s GHG emissions.

Additionally, a new model was constructed using data up to 2016 for the MDAM approach, which had achieved a lower error rate. This model was then used to generate forward predictions for the years 2017 and 2018—years known to be free from suppressive effects such as those caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on these results, the average error rate was calculated as 2.1% MAPE, further demonstrating the reliability of the model’s future predictions.

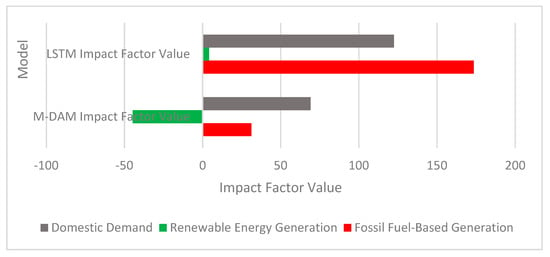

3.2. Impact Factor Analysis

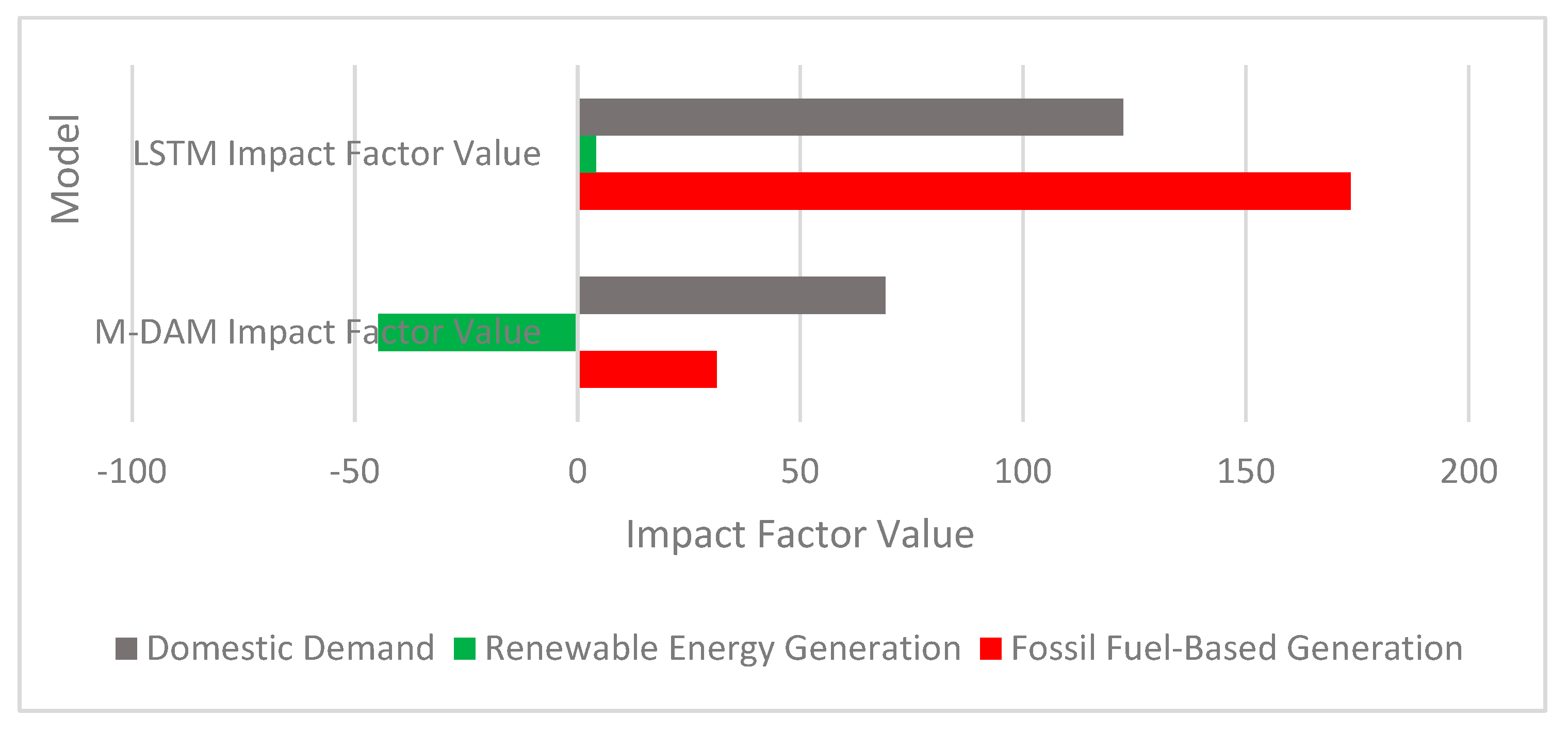

To gain a deeper understanding of the determinants of GHG emissions, an impact factor analysis was conducted to assess the influence of three key variables on GHG levels (Table 2).

Table 2.

Impact factor results for GHG emissions of the MDAM and LSTM.

According to the results obtained from the MDAM model, domestic demand (electricity consumption) has the highest positive impact on GHG emissions, with a coefficient of 69.0755. This indicates that increasing energy demand directly drives emissions upward. Fossil fuel-based electricity generation also contributes positively to emissions, with an impact value of 31.2377, confirming the direct influence of fossil-based energy production on Türkiye’s carbon output. On the other hand, renewable energy production has a negative impact on GHG emissions, with a coefficient of –44.68, meaning that increasing the share of renewables plays a role in reducing emissions.

These findings emphasize the importance of energy transition strategies and highlight that demand-side management, energy efficiency, and a shift to renewable sources are critical for achieving emission reduction targets.

In the analysis conducted using the LSTM model, domestic demand (electricity consumption) and fossil fuel-based energy generation emerged as the two primary determinants of emissions. The weight of the domestic demand factor was calculated as 122.49, while that of fossil fuel-based generation was 173.51. These results indicate not only the overall increase in energy demand, but more importantly, that reliance on fossil fuel-based generation to meet this demand significantly drives up emissions.

In contrast, the impact of renewable energy generation was measured at just 4.21, which is considerably lower compared to the other two factors. This finding suggests that while increasing the share of renewables in the energy mix has the potential to reduce emissions, its current effect remains limited. In other words, for Türkiye to make a meaningful impact on emission reduction, it must significantly reduce fossil fuel-based generation and manage energy demand more efficiently. Additionally, the production volume and system share of renewable energy must be substantially increased to enhance its effectiveness.

For the LSTM model (Figure 4), the impact of independent variables (fossil-based electricity generation, renewable electricity generation, and total electricity demand) on GHG emissions was quantified through a linear regression-based factor analysis conducted after model training. The regression coefficients, obtained using normalized variables, were evaluated according to their signs and magnitudes to identify positive or negative influences on emissions. This approach follows model-agnostic interpretability techniques widely discussed in the literature.

Figure 4.

Impact factor plot for GHG emissions of the MDAM and LSTM.

For the MDAM model, the impact factors were computed directly from fractional coefficients () derived within the Caputo fractional derivative formulation. The theoretical and empirical basis for this approach is supported by Önal Tuğrul et al. (2024), which applies the same Caputo-based structure to a different data domain [20]. While advanced feature-importance methods such as SHAP were considered, they were not applied in this study due to the deterministic mathematical nature of the MDAM framework and the limited dimensionality of the dataset.

4. Discussion

This study investigates advanced methods for modeling and predicting GHG emissions. A deep learning-based time-series model, LSTM, is compared with the MDAM, which is based on Caputo fractional derivatives. While LSTM is highly effective in capturing long-term patterns in time-series data, MDAM has the advantage of modeling long-term dependencies more accurately by extending differential and integral operators to fractional orders [14,28]. The analysis was conducted using data from the TurkStat on GHG emissions from 1993 to 2022, and additional data from TEIAŞ including electricity generated from fossil fuels, electricity generated from renewable sources, and total domestic electricity demand. Both models were trained using this data, and 2030 GHG emission predictions were produced, along with coefficient estimates showing the influence of other factors on emissions. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emission trends was also analyzed.

The models were optimized for best performance and compared using the MAPE, RMSE, and R2 metrics. According to the results, the MDAM model achieved superior accuracy, with a MAPE of 1.64%, RMSE of 10.08, and R2 of 0.9828, while the LSTM model produced a MAPE of 2.69%, RMSE of 13.06, and R2 of 0.9794. For the year 2030, the LSTM model predicted 709.49 Mt CO2e, whereas the MDAM model predicted 721.86 Mt CO2e. Since Türkiye’s 2030 target under the Paris Agreement 695 Mt CO2e, the results suggest that current policies must be maintained and strengthened to meet the goal [6].

One of the key findings of the study is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emissions. To observe this effect, both models were re-trained using data only up to 2018 to simulate a scenario in which the pandemic never occurred. The LSTM model predicted 778.28 Mt CO2e for 2030 under this scenario, while the MDAM model predicted 798.14 Mt CO2e. These estimates are significantly higher than the actual post-pandemic predictions, indicating that reductions in industrial and transport activity during the pandemic led to lower emissions. The findings demonstrate that structural changes in energy use, transportation, and industry can significantly reduce emissions when maintained over time.

Moreover, this research highlights the strength of the MDAM model as a prediction tool. It achieved a better MAPE value than LSTM, a deep learning algorithm known for its high performance in time-series data. This study demonstrates the value of integrating fractional calculus with machine learning for environmental prediction and emphasizes the urgency of investing in renewable energy and low-carbon technologies to achieve Türkiye’s climate goals.

Considering Türkiye’s plans to peak emissions by 2038 and reach net zero by 2053, the implementation of strong and consistent policies is essential. These should include accelerating investments in renewable energy to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, promoting low-carbon technologies in industry and transportation, enhancing carbon capture and storage (CCS) capacity, and strengthening national and international climate action collaborations [1,7]. With the right policies and investments, Türkiye can transition to a low-carbon economy, contribute to global climate goals, and ensure long-term economic and environmental sustainability.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a comprehensive comparison of advanced modeling techniques for modeling, impact factor analysis, and prediction of Türkiye’s GHG emissions. The analysis evaluated the fractional calculus-based MDAM and the deep learning-based LSTM network, while the ARIMAX model was employed as a statistical benchmark to assess the robustness of the proposed approaches.

The modeling results showed that both the MDAM and LSTM models achieved high levels of accuracy. However, the MDAM model demonstrated superior performance in representing long-term trends and capturing long-memory dynamics, achieving lower error rates and greater stability. The LSTM model successfully modeled nonlinear relationships and temporal dependencies but performed slightly below MDAM in terms of overall accuracy. When compared with the ARIMA model, both advanced approaches were found to capture the complex and persistent structures within the time series more effectively.

A no-COVID scenario yielded higher forecasts, confirming the pandemic’s suppressive effect. Impact factor analysis revealed that domestic electricity demand and fossil-based generation are the strongest drivers, while renewables mitigate emission.

Overall, the prediction results highlight that both MDAM and LSTM models are reliable tools for emission prediction, with MDAM offering higher interpretability and long-memory precision. Integrating fractional calculus with data-driven modeling provides significant advantages in terms of accuracy and explainability for environmental forecasting. To achieve Türkiye’s 2038 emission peak and 2053 net-zero targets, decisive and sustained policy actions are required—particularly in expanding renewable energy, accelerating low-carbon industrial transformation, and enhancing carbon capture and storage (CCS) capacity.

In future studies, we plan to further develop and apply the MDAM model, while also expanding the dataset to a global scale. This extended analysis will incorporate GDP indicators and consider the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis, aiming to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between economic growth and environmental sustainability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en18215828/s1, MATLAB R2023b and Python 3.10 (PyCharm 2023.3 IDE) codes for LSTM and M-DAM modeling, prediction, and impact factor methods are shared in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

The contribution of each author is listed as follows. N.Ö.Ö.T. plays an important role in supervision, methodology, editing, and validation. G.G.B. was the key person in investigation, writing, conceptualization, data curation, visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Garantiplast Geri Donusum Sanayi ve Ticaret Anonim Sirketi.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in Appendix A of the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Ertuğrul Karaçuha for his valuable contributions, sharing his knowledge and expertise throughout this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDAM | Multi Deep Assessment Methodology |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Dataset from TurkStat and TEIAŞ for Türkiye (1993–2022) [39].

Table A1.

Dataset from TurkStat and TEIAŞ for Türkiye (1993–2022) [39].

| Year | GHG (Mt) | Fossil (MW) | Renewables (MW) | Electricity Demand (MW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 249.1 | 10,638.4 | 9699.2 | 3943.1 |

| 1994 | 242.8 | 10,977.7 | 9882.1 | 4539.1 |

| 1995 | 256.5 | 11,074 | 9880.3 | 4388.8 |

| 1996 | 275.9 | 11,297.1 | 9952.3 | 4777.3 |

| 1997 | 286.7 | 11,771.8 | 10,120.1 | 5050.2 |

| 1998 | 288.1 | 13,021.3 | 10,332.7 | 5523.2 |

| 1999 | 285.6 | 15,555.9 | 10,563.4 | 5738.0 |

| 2000 | 306.4 | 16,052.5 | 11,211.6 | 6224.0 |

| 2001 | 287.6 | 16,623.1 | 11,709.3 | 6472.6 |

| 2002 | 292.5 | 19,568.5 | 12,277.3 | 5672.7 |

| 2003 | 312.1 | 22,974.4 | 12,612.6 | 5332.2 |

| 2004 | 321.7 | 24,144.7 | 12,679.3 | 5632.6 |

| 2005 | 344.8 | 25,902.3 | 12,941.2 | 6487.1 |

| 2006 | 365.2 | 27,420.2 | 13,144.6 | 6756.7 |

| 2007 | 399 | 27,271.6 | 13,564.1 | 8218.4 |

| 2008 | 394.9 | 27,595 | 14,222.2 | 8656.1 |

| 2009 | 401.3 | 29,339.1 | 15,422.1 | 8193.6 |

| 2010 | 405.3 | 32,278.5 | 17,245.6 | 8161.6 |

| 2011 | 434.8 | 33,931.1 | 18,980.0 | 11,837.4 |

| 2012 | 455.2 | 35,027.2 | 22,032.2 | 11,789.5 |

| 2013 | 447.3 | 38,648 | 25,359.5 | 11,177.0 |

| 2014 | 466.4 | 41,801.8 | 27,718.0 | 12,513.9 |

| 2015 | 480.1 | 41,903 | 31,243.7 | 11,883.8 |

| 2016 | 504.1 | 44,411.6 | 34,085.8 | 12,471.0 |

| 2017 | 531.1 | 46,926.3 | 38,273.7 | 13,020.0 |

| 2018 | 528.1 | 46,908.6 | 41,642.2 | 14,299.7 |

| 2019 | 515.6 | 47,663 | 43,604.0 | 14,761.8 |

| 2020 | 530.2 | 47,793.7 | 48,096.9 | 14,039.0 |

| 2021 | 572 | 48,228.3 | 51,591.4 | 15,183.1 |

| 2022 | 558.3 | 49,724.8 | 54,084.4 | 15,461.8 |

References

- Çevre, Şehircilik ve İklim Değişikliği Bakanlığı. İklim Değişikliğine Uyum Stratejisi ve Eylem Planı (2024–2030). 2024. Available online: https://iklim.gov.tr/db/turkce/icerikler/files/Iklim%20Degisikligine%20Uyum%20Stratejisi%20ve%20Eylem%20Plan%C4%B1.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- World Economic Forum. Global Risks Report 2025; World Economic Forum: Davos, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-risks-report-2025 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Birleşmiş Milletler. Paris Anlaşması. İklim Değişikliği Başkanlığı. 2015. Available online: https://iklim.gov.tr/paris-anlasmasi-i-34 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Republic of Türkiye. Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC). UNFCCC. 2022. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/The_INDC_of_TURKEY_v.15.19.30.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Republic of Türkiye. Updated First Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). UNFCCC. 2023. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2023-04/T%C3%9CRK%C4%B0YE_UPDATED%201st%20NDC_EN.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Şahin, Ü.; Tör, O.B.; Kat, B.; Teimourzadeh, S.; Demirkol, K.; Künar, A.; Voyvoda, E.; Yeldan, E. Türkiye’nin Karbonsuzlaşma Yol Haritası: 2050’de Net Sıfır; İstanbul Politikalar Merkezi, Sabancı Üniversitesi: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2022; Available online: https://ipc.sabanciuniv.edu/Content/Images/CKeditorImages/20211026-23103436.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Ayaz, İ. Forecasting CO2 emissions with machine learning methods: Türkiye example and future trends. Mal. Turgut Özal Univ. J. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2024, 5, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğanlar, M.; Mike, F.; Kızılkaya, O.; Karlılar, S. Testing the long-run effects of economic growth, financial development and energy consumption on CO2 emissions in Türkiye: New evidence from RALS cointegration test. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 32554–32563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtkuran, S. The effect of agriculture, renewable energy production, and globalization on CO2 emissions in Türkiye: A bootstrap ARDL approach. Renew. Energy 2021, 171, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaaslan, A.; Çamkaya, S. The relationship between CO2 emissions, economic growth, health expenditure, and renewable and non-renewable energy consumption: Empirical evidence from Türkiye. Renew. Energy 2022, 190, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykaç Özen, H. COVID-19 salgını dönemindeki kısıtlamaların sera gazı salınımına etkisi. Niğde Ömer Halisdemir Üniversitesi Mühendislik Bilim. Derg. 2022, 11, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Deng, X.; Chen, H.; Qin, Z. Estimating fossil CO2 emissions from COVID-19 post-pandemic recovery in G20: A machine learning approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 140875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wu, W.-Z.; Liu, C.; Zhang, T.; Dong, Z. Forecasting fuel combustion-related CO2 emissions by a novel continuous fractional nonlinear grey Bernoulli model with grey wolf optimizer. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 38128–38144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Choudhary, V.; Saxena, D.; Singh, A.K. Lstm and nlp based forecasting model for stock market analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 First International Conference on Advances in Computing and Future Communication Technologies (ICACFCT), Meerut, India, 16–17 December 2021; pp. 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, A.; Jaitly, N.; Mohamed, A.R. Hybrid speech recognition with deep bidirectional LSTM. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Workshop on Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding, Olomouc, Czech Republic, 8–12 December 2013; pp. 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Lamurias, A.; Sousa, D.; Clarke, L.A.; Couto, F.M. BO-LSTM: Classifying relations via long short-term memory networks along biomedical ontologies. BMC Bioinform. 2019, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Feng, C.; Xu, N.; Peng, S.; Liu, C. Early warning of exchange rate risk based on structural shocks in international oil prices using the LSTM neural network model. Energy Econ. 2023, 126, 106921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almosova, A.; Andresen, N. Nonlinear inflation forecasting with recurrent neural networks. J. Forecast. 2023, 42, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önal Tuğrul, N.Ö.; Karaçuha, K.; Ergün, E.; Tabatadze, V.; Karaçuha, E. A novel modeling and prediction approach using Caputo derivative: An economical review via multi-deep assessment methodology. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 23512–23543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, G.; Sharma, A.; Sahotra, A.; Kapoor, R. English–Hindi Neural Machine Translation—LSTM Seq2Seq and ConvS2S. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), Chennai, India, 28–30 July 2020; pp. 871–875. [Google Scholar]

- Behera, R.K.; Jena, M.; Rath, S.K.; Misra, S. Co-LSTM: Convolutional LSTM model for sentiment analysis in social big data. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Huang, H.; Ruan, T. Abstractive text summarization using LSTM-CNN based deep learning. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 857–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Jiang, A.; Liu, X.; Shang, J.; Zhang, L. LSTM-based EEG classification in motor imagery tasks. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2018, 26, 2086–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, Ö. A novel wavelet sequence based on deep bidirectional LSTM network model for ECG signal classification. Comput. Biol. Med. 2018, 96, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Wan, S.; Wang, F.; Dou, W.; Xu, X.; Shancang, L.; Ma, R.; Qi, L. A long short-term memory-based model for greenhouse climate prediction. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, M.; Gurrieri, A.R.; Morelli, G.; Magazzino, C. Nature and climate change effects on economic growth: An LSTM experiment on renewable energy resources. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 41127–41134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, K. Kesirli Kalkülüs ve Derin Değerlendirme Yaklaşımı ile Havacılık Verilerinin Modellenmesi, Etki Faktörlerinin Analizi ve Öngörü Çalışması. Ph.D. Thesis, İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi, Istanbul, Türkiye, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Magin, R.L. Fractional calculus in bioengineering, part 1. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2004, 32, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scalas, E.; Gorenflo, R.; Mainardi, F. Fractional calculus and continuous-time finance. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2000, 284, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baleanu, D.; Güvenç, Z.B.; Machado, J.A.T. New Trends in Nanotechnology and Fractional Calculus Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moreles, M.A.; Lainez, R. Mathematical modelling of fractional order circuit elements and bioimpedance applications. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2017, 46, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierociuk, D.; Dzieliński, A.; Sarwas, G.; Petras, I.; Podlubny, I.; Skovranek, T. Modelling heat transfer in heterogeneous media using fractional calculus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2013, 371, 20120146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, P.; Jain, S.; Goyal, K.; Marculescu, R. Implantable pacemakers control and optimization via fractional calculus approaches: A cyber-physical systems perspective. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/ACM Third International Conference on Cyber-Physical Systems, Beijing, China, 17–19 April 2012; pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Önal, N.Ö.; Karacuha, K.; Karacuha, E. A Comparison of Fractional and Polynomial Models: Modelling on Number of Subscribers in the Turkish Mobile Telecommunications Market. Int. J. Appl. Phys. Math. 2019, 10, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergün, E.; İbişoğlu, E.; Önal Tuğrul, N.Ö.; Karaçuha, K.; Helvacı, M.; Karaçuha, E. Modeling internet access at home by fractional calculus and a correlation analysis with human development index. TWMS J. Appl. Eng. Math. 2024, 14, 446–459. [Google Scholar]

- Karacuha, K.; Sağlamol, S.A.; Ergün, E.; Tuğrul, N.Ö.Ö.; Şimşek, K.; Karacuha, E. Mathematical Modeling of European Countries’ Telecommunication Investments. El-Cezeri 2022, 9, 1028–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Tuğrul, N.Ö.Ö.; Başer, C.; Ergün, E.; Karaçuha, K.; Tabatadze, V.; Eker, S.; Karacuha, E.; Şimşek, K. Modeling of mobile and fixed broadband subscriptions of countries with fractional calculus. Transp. Telecommun. 2022, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation (TEİAŞ). Türkiye National Greenhouse Gas Inventory [Official Report]; Turkish Electricity Transmission Corporation (TEİAŞ): Çankaya, Türkiye, 2024. Available online: https://www.teias.gov.tr/turkiye-elektrik-uretim-iletim-istatistikleri (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Karaçuha, E.; Önal, N.Ö.; Ergün, E.; Tabatadze, V.; Alkaş, H.; Karaçuha, K.; Tontus, H.; Nu, N.V.N. Modeling and prediction of the COVID-19 cases with deep assessment methodology and fractional Calculus. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 164012–164034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaçuha, E.; Tabatadze, V.; Karaçuha, K.; Önal, N.Ö.; Ergün, E. Deep assessment methodology using fractional calculus on mathematical modeling and prediction of gross domestic product per capita of countries. Mathematics 2020, 8, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).