Abstract

This paper addresses the long-standing question of understanding the origin and evolution of low-frequency unsteadiness interactions associated with shock waves impinging on a turbulent boundary layer in transonic flow (Mach: to ). To that end, high-speed experiments in a blowdown open-channel wind tunnel have been performed across a convergent–divergent nozzle for different expansion ratios (PR = 1.44, 1.6, and 1.81). Quantitative evaluation of the underlying spectral energy content has been obtained by processing time-resolved pressure transducer data and Schlieren images using the following spectral analysis methods: Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT), as well as coherence and time-lag evaluations. The images demonstrated the presence of increased normal shock-wave impact for PR = 1.44, whereas the latter were linked with increased oblique -foot impact. Hence, significant disparities associated with the overall stability, location, and amplitude of the shock waves, as well as quantitative assertions related to spectral energy segregation, have been inferred. A subsequent detailed spectral analysis revealed the presence of multiple discrete frequency peaks (magnitude and frequency of the peaks increasing with PR), with the lower peaks linked with large-scale shock-wave interactions and higher peaks associated with shear-layer instabilities and turbulence. Wavelet transform using the Morlet function illustrates the presence of varying intermittency, modulation in the temporal and frequency scales for different spectral events, and a pseudo-periodic spectral energy pulsation alternating between two frequency-specific events. Spectral analysis of the pixel densities related to different regions, called spatial FFT, highlights the increased influence of the feedback mechanism and coupled turbulence interactions for higher PR. Collation of the subsequent coherence analysis with the previous results underscores that lower PR is linked with shock-separation dynamics being tightly coupled, whereas at higher PR values, global instabilities, vortex shedding, and high-frequency shear-layer effects govern the overall interactions, redistributing the spectral energy across a wider spectral range. Complementing these experiments, time-resolved numerical simulations based on a transient 3D RANS framework were performed. The simulations successfully reproduced the main features of the shock motion, including the downstream migration of the mean position, the reduction in oscillation amplitude with increasing PR, and the division of the spectra into distinct frequency regions. This confirms that the adopted 3D RANS approach provides a suitable predictive framework for capturing the essential unsteady dynamics of shock–boundary layer interactions across both temporal and spatial scales. This novel combination of synchronized Schlieren imaging with pressure transducer data, followed by application of advanced spectral analysis techniques, FFT, CWT, spatial FFT, coherence analysis, and numerical evaluations, linked image-derived propagation and coherence results directly to wall pressure dynamics, providing critical insights into how PR variation governs the spectral energy content and shock-wave oscillation behavior for nozzles. Thus, for low PR flows dominated by normal shock structure, global instability of the separation zone governs the overall oscillations, whereas higher PR, linked with dominant -foot structure, demonstrates increased feedback from the shear-layer oscillations, separation region breathing, as well as global instabilities. It is envisaged that epistemic understanding related to the spectral dynamics of low-frequency oscillations at different PR values derived from this study could be useful for future nozzle design modifications aimed at achieving optimal nozzle performance. The study could further assist the implementation of appropriate flow control strategies to alleviate these instabilities and improve thrust performance.

1. Introduction

Air and water are essential substances for human life, widely utilized in technology as carriers of energy—whether potential, kinetic, or thermal—for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. While we have a proper understanding of many physical phenomena involving air and water, there is still much to explore. Transonic flows corresponding to high-speed aerospace applications frequently encounter shock waves, whether oblique or normal [1]. One of the most fundamental fluid mechanics phenomena in the aerospace domain, known since 1939 [2], and studied globally for more than 60 years, has been the complex interaction between these shock waves and the underlying boundary layer fluctuations [3,4,5,6]. These interactions, also called the Shock-wave Boundary Layer Interactions (SBLIs), have been established to occur across a wide range of internal and external flow applications [3], including transonic airfoils, supersonic inlets, control surfaces of high-speed aircraft, missile base flows, reaction control jets, over-expanded nozzles, and space launchers [6,7]. The presence of these non-linear interactions [8] leads to several adverse aerodynamic, thermal, and structural impacts clearly emphasized in Refs. [3,4,7,8], warranting the need to critically consider this phenomenon during the design and optimization phase. Owing to the ongoing progress in diagnosis and computational tools [4,9], amelioration of the potentially far-reaching consequences of SBLIs like fluid-flow fluctuations [9], aero-thermal loads [3], as well as buffeting at high angles [10,11] and implementation of flow control techniques [11] have been intensely studied within the academic and industrial sectors.

Interactions associated with SBLIs have been widely studied across various canonical geometries involving shock impingement, ramp flow, transonic flow over a bump, fins, as well as internal flow geometries, including inlets and nozzle flows [4,9]. These investigations primarily followed two methodologies: analysis of mean and unsteady measurements of flow parameters such as static pressure, heat transfer, shear stress, and non-intrusive measurements like Schlieren images, Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV), and many more, unfolding significantly varying flow-field structures across laminar, transition, and turbulent flows [9]. Apart from the incoming flow’s turbulence characteristics, unsteadiness related to SBLIs is further associated with the global instability of these interactions, which further varies between Free Shock Separation (FSS) and a Restricted Shock Separation (RSS) flow. Despite the diverse nature of these canonical flow features, investigations have revealed some common flow attributes associated with SBLIs [6,7,12]. The adverse pressure gradient imposed by the presence of shock waves leads to boundary layer thickening and subsequent separation of the flow. The interaction between shock waves and this boundary layer leads to several unsteady flow characteristics involving a wide range of temporal and spatial interactions. One of the most notable interactions is the origin and propagation of low-frequency unsteadiness appearing as streamwise oscillations of the separation shock [6]. These oscillations involve unsteadiness of the shock wave placed upstream of the recirculation zone, with the shock-wave oscillating at frequencies two to three orders of magnitude lower than the incoming turbulent-boundary-layer fluctuations and the recirculating zone [12,13,14].

The relevance of understanding these unsteady separation flow dynamics in relation to SBLIs for internal flows, including over-expanded nozzles, was emphasized by NASA in their 1996 research announcement [3]. The presence of SBLIs leads to the generation of oscillating -foot shock waves [15,16] over a length called the intermittent region (). The asymmetric structure of this low-frequency oscillating complex flow structure, along with the unsteadiness associated with the boundary layer, mixing layer, and the recirculation zone, leads to the generation of lateral forces, reduction in the output thrust, and degenerated structural integrity. Considering the impact of controlling this flow phenomenon on generating “quieter, shorter, lighter” nozzles [3] for future high-speed applications, a lot of research has been carried out to understand the flow physics related to these low-frequency oscillations [6,8,12,17], especially after the 2001 publication of a review article by Dolling in Ref. [3]. This reinvigorated interest was further supported by the synergistic growth of flow diagnosis tools and computational resources. Much of the earlier investigations made use of the experimental techniques to understand the driving mechanism [13,18,19]. The last decade witnessed the usage of high-fidelity numerical tools like DNS (Direct Numerical Simulations [6,20]) and LESs (Large Eddy Simulations [21]) to explore the phenomenology and obtain further visual insights that were previously not possible with experimental techniques. Notwithstanding these developments, there is a paucity of globally accepted physics governing the driving mechanism behind these large-scale, low-frequency shock pulsations. An analytical study by Plotkin in 1975 [22] inferred these oscillations to be analogous to a random-walk process driven by high-frequency upstream turbulent-boundary-layer fluctuations. Experimental studies carried out by Ganapathisubramani et al. in Ref. [13] indicated the increased influence of upstream low-frequency superstructures on the interaction unsteadiness, which was later contradicted by Piponniau et al. in Ref. [23]. A study carried out by Pirozzoli et al. credited the high-frequency low-scale unsteady interactions to the incoming acoustic feedback mechanism [20].

Despite the plethora of studies indicating the influence of upstream boundary layer momentum on the shock interactions, a number of studies emphasize the increased influence of the downstream driving mechanism. Large Eddy Simulations (LESs) by Touber et al. [24] illustrated that global instability associated with the separation bubble led to contraction and expansion of this separation bubble (“separation-bubble breathing”), which drives these unsteadiness interactions. Piponniau et al. [23] proposed a shear-layer recharge mechanism to be the source of streamwise oscillations. This model proposed the entrainment of separation region flow towards the high velocity shear layer, followed by a recharge feedback mechanism of the separation bubble mass through the reattachment point. This feedback mechanism leads to the large-scale shear-layer “flapping” and separation bubble scaling phenomena. The DNS study of Priebe et al. in 2012 [25] attributed this large-scale shear-layer flapping to near-wall fluctuations that seed the shear layer with appropriate flow structures, leading to unsteadiness of the shear-layer structure. Wu and Martin 2008 [26] presented a unique philosophy entailing an unsteadiness mechanism and proposed that both upstream and downstream flow fluctuations influence the large-scale shock-wave motion unsteadiness, with the former affecting the smaller-scale unsteadiness, whereas separation region pulsation determines the large-scale motions. These conclusions were further corroborated by Piponniau et al. [23] and Priebe et al. [25]. Wu and Martin further established the dependence of shock interaction unsteadiness on the underlying Mach number (), Reynolds number (), and shock incidence angle [27,28,29]. Clemens and Narayanaswamy in Ref. [7] concluded that both the upstream and downstream mechanisms influence the overall unsteadiness, with the former being dominant in the case of strongly separated flows, whereas a combination of the two mechanisms is observed for weak separation flows. Numerical investigations carried out by Touber and Sandham in 2011 [30] utilized Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations to study these interactions for a shock-reflection configuration and concluded that the large-scale oscillations are associated with the intrinsic properties of the coupled systems, with the upstream and downstream forcing mechanisms not being the only sources of fluctuations. A 2017 LES study segregated the unsteadiness associated with the shock system, separation bubble, and shear-layer interactions into two modes: a medium-frequency mode driven by shear-layer vortices and a low-frequency mode with separation-bubble breathing as the dominant forcing function [31]. Experimental observations compiled by Shanguang et al. [32] concluded that the instability associated with the separation bubble is the greatest source of large-scale shock-wave movement. As an addendum to justifying the relevance of downstream conditions, a Lagrangian framework was developed by Ligrani et al. [14] to post-process time-resolved shadowgraph images for analyzing the coherence of normal shock waves, using pixel-density calculations within different SBLI zones. The detailed coherence, spectral power, and time-lag calculations reinstated the prominent impact of the separation bubble and shear-layer flapping on the unsteadiness interactions. Although a detailed spectral analysis of DNS data presented by Bernardini et al. concluded the increased impact of separation-layer breathing on shock-wave unsteadiness, their results also indicated the influence of many other factors embedded within the shock-wave dynamics [6]. In fact, a doctoral study by Nguyen [33] concluded that apart from the aforementioned local flow features, shock motion related to FSS could be strongly linked to the shape of the exit section. In view of these assertions, it can be stated unequivocally that there is a lack of globally accepted understanding pertaining to large-scale shock-wave oscillations, and hence, requires further scrutiny.

With the increasing demand for high-speed applications [34], there is a need to critically examine the physics related to this phenomenon for nozzle geometry, while ensuing effects related to variation in flow parameters, humidity, as well as nozzle geometry. This internal flow problem is associated with exacerbated flow complexities due to multiple reflected shock-wave generation, separation in multiple regions, mixing layers, recirculation, and their interactions [16,35]. Notably, flow through an over-expanded transonic De Laval nozzle at elevated back pressure involves a supersonic-to-subsonic flow transition through shock-wave generation, increased flow separation together with shock-wave oscillations. These shock waves in the divergent section interact with the turbulent boundary layer, leading to complex asymmetric shock-wave oscillations. Several attempts have been made in the past to enhance understanding related to low-frequency oscillations (LFOs) within the context of high-speed flow through nozzles. Under the auspices of NASA Glenn Research Center, a 2009–2010 study by Johnson et al. made use of experimental campaigns to contemplate the complex multiple-shock-wave structure dynamics [35] and sources of instability related to LFO [36]. These studies recognized that separation strength, shear-layer instability, and asymmetric shock-wave structure had a prominent impact on the shock motion. Inferences drawn from a later LES numerical study by Olson and Lele [37] were found to be in concordance with Johnson et al.’s experimental observations [36]. A numerical study by Martelli et al. [38] reasoned that the self-sustaining shock-wave oscillations were related to the pressure differential between the downstream re-compression region and the nozzle exit (ambient).

In view of the above, the principal point of contention in this field is the ubiquitous lack of consensus related to the source of these shock-wave oscillations across all canonical problems, especially nozzle flows. Moreover, the research gap associated with fundamental understanding related to shock-wave oscillations within open flow separation interactions [7] linked with over-expanded nozzles further warranted the need for this research. Increased understanding related to these low-frequency shock-wave oscillations within nozzle configurations, while deliberating its dependence on the overall flow conditions and geometry, could pave the way for future technological advancements in nozzle design optimization. Insights associated with the underlying spectral energy distribution and transfer mechanisms of low-frequency oscillations at different pressure ratios would be helpful in implementing design modifications to the current state-of-the-art by making use of adaptive nozzle design or flow control strategies, aimed at curtailing the peak instabilities. Although significant progress has been made through experimental campaigns and high-fidelity simulations such as DNS and LES, these approaches are often constrained by technical limitations, high computational costs, or difficulties in accessing certain flow regions. As a result, there remains a clear need for modeling frameworks that can systematically explore parametric variations and what-if scenarios that are either impractical or prohibitively expensive to examine experimentally. In this regard, simplified but validated numerical approaches, particularly unsteady Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (URANS) formulations, offer a pragmatic compromise. While not as detailed as DNS or LES, URANS-based models have shown the potential to reproduce essential flow features of SBLIs, including low-frequency unsteadiness. When benchmarked against experimental datasets, these models can provide valuable insights into the relative influence of upstream turbulence, coherent flow structures, and downstream separation bubble dynamics. In nozzle applications, this capability is particularly relevant, as the complex interaction of multiple shocks, recirculation zones, and asymmetric flow separation makes experimental isolation of individual mechanisms difficult. In view of the same, the experimental observations will be collated with results obtained using a numerically efficient URANS framework and capture low-frequency oscillations in over-expanded nozzle flows. While representing only an initial step towards more comprehensive modeling, the approach covered in this paper demonstrates that simplified models, when carefully validated, can complement experimental diagnostics and provide predictive understanding necessary for aerodynamic optimization and potential flow-control strategies in high-speed propulsion systems. Comprehensions on the physical principles inferred through this experimentally and numerically obtained spectral energy distribution and coherence estimates would also be helpful for advancement in other fluid dynamic systems, such as multiphase or chemical reactive flows. Furthermore, the ensuing unique combination of advanced spectral analysis, coherence, and time-lag estimations backed up by numerical evaluations, provides a critical step forward in spectral energy analysis of shock-wave oscillations. The integration of this causal framework with machine learning techniques like the one implemented by Hu et al. [39] and Kumar et al. in [40] provides a concrete and cutting-edge methodological exemplar for potential future research directions arising from the present work.

To that end, the current research aims to process, analyze, and evaluate the dynamic shock-wave oscillations within an asymmetric convergent–divergent nozzle operating at transonic speeds and enhance understanding related to the linked low-frequency unsteadiness. The research objectives are listed hereafter:

- Setting up an experimental setup to investigate shock-wave–boundary layer interactions and low-frequency shock-wave oscillations, allowing for systematic variation of parameters such as pressure ratio, humidity, nozzle expansion rate, and channel geometry.

- Establishing a synchronized experimental evaluation of a time-resolved large dataset of plan-view high-speed Schlieren images and pressure transducer readings, followed by preliminary numerical evaluations.

- Formulating a new analysis framework for such complex problems involving the collation of advanced spectral analysis using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), wavelet transform [6] and coherence estimation [14] to comprehend the unsteady parameters linked with LFO within the context of FSS [12,15,16] of nozzle flow dynamics.

- Integrating high-fidelity computational techniques like URANS with spectral techniques and experimental evaluations to further enhance physical insights related to the coupled SBLIs.

- It was envisaged that the appropriate correlation of these results, carried out at different pressure ratios, would increase understanding related to spectral energy evolution and distribution, thereby helping create novel designs or flow-control strategies to improve thrust performance.

The current paper makes use of the following sections to analyze the flow physics of SBLIs. Section 2 provides details about the experimental and numerical set-up, including the deliberated flow conditions, implemented measurement systems, and the procedure(s) thereof. Section 3 corresponds to the results and discussion section, making use of time-resolved Schlieren images and pressure data to understand the governing flow physics. This section culminates in providing a brief overview of the numerical simulations carried out to capture the flow unsteadiness and underlying flow structure. The terminal section, that is, Section 4, presents some key conclusions drawn out from these experimental and numerical investigations.

Despite numerous studies on shock-wave oscillations in over-expanded nozzle flows, a clear consensus on the underlying physical mechanisms governing their low-frequency unsteadiness is still lacking. The present study addresses this research gap by employing a combination of experimental investigations and a validated numerical technique framework carried out at different PRs to systematically investigate the spectral energy distribution, coherence, and causal interactions governing low-frequency shock-wave oscillations in nozzle configurations. By integrating advanced spectral and time-lag analyses with experimental observations, this work aims to elucidate the energy transfer mechanisms governing these oscillations. The inferences will not only advance the fundamental understanding of shock-induced flow separation dynamics but also provide a foundation for future adaptive nozzle designs and flow control strategies, targeting stability enhancement in high-speed propulsion systems.

2. Methodology

2.1. Experimental Setup and Procedure

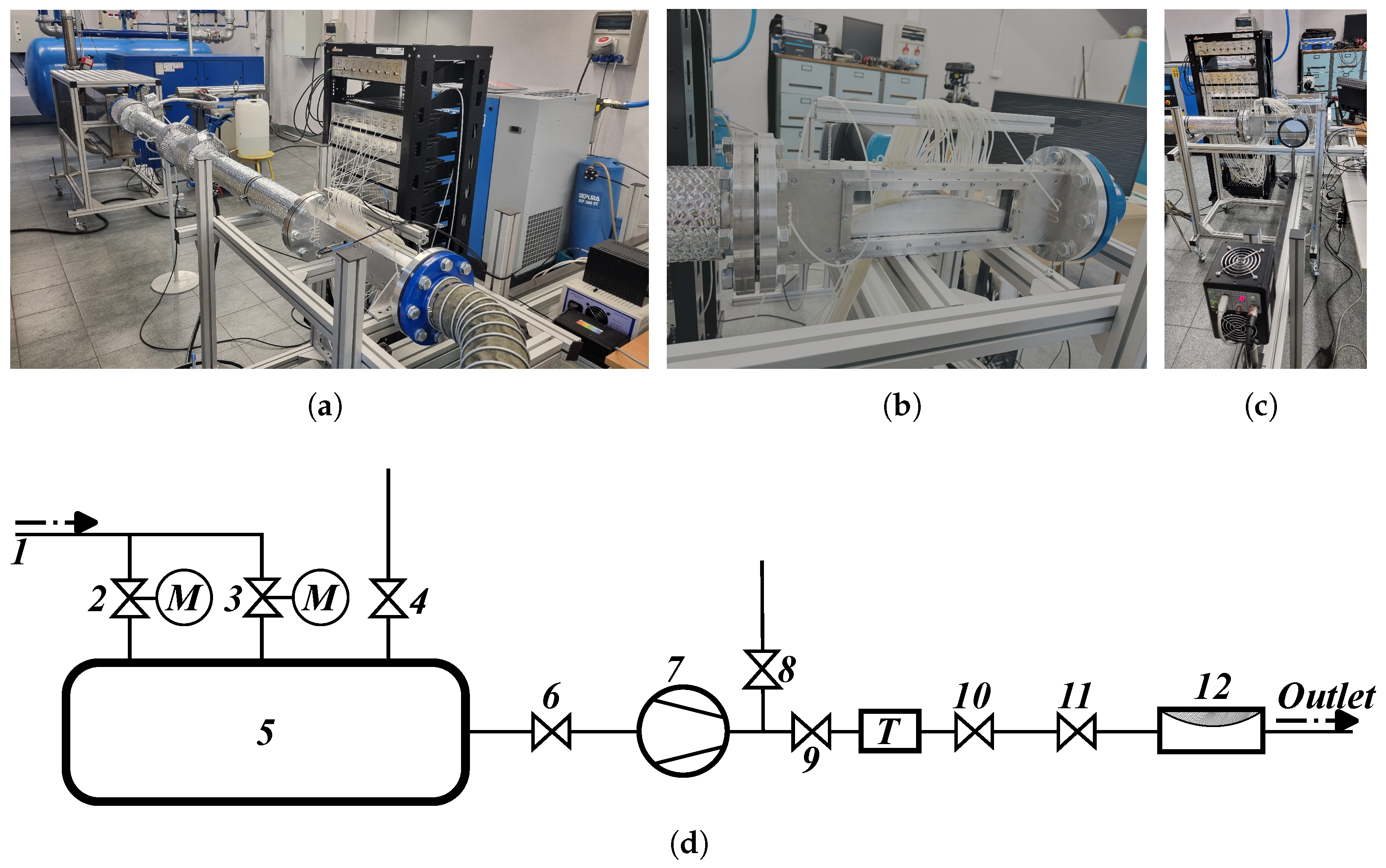

The laboratory located on the air test rig of the Department of Power Engineering and Turbomachinery of the Silesian University of Technology (SUT) was used to perform the experimental tests presented in this paper. This lab has been extensively engaged in carrying out state-of-the-art experimental investigations on nozzle flows [41,42] for many years. Tests in the current research were performed using the air vacuum experimental setup installed at SUT for analysis of high-speed aerodynamic flows (Figure 1). A schematic of the utilized experimental setup is presented in Figure 1d, whereas the components indicated in the schematic are described in Table 1. The blowdown experimental setup makes use of a Roots blower to maintain the required pressure in the gas chamber placed downstream of the inlet pipe, regulated by control valves to maintain the required PR. To make sure that stabilization and repeatability of inlet conditions are maintained across the experiments, a temperature–pressure-stabilized inlet chamber is installed upstream of the test section. The presented method of regulation ensures convenient, precise, and repeatable setting of the PR at which the stand operates. Apart from this, the setup makes use of triple measurement of the mass flow parameters using hot-wire anemometers upstream, downstream, and within the test section, to ensure a uniform and accurate determination of the flow characteristics related to the tested geometry. This also helps in detecting potential external leaks during the experiments.

Figure 1.

(a) Air vacuum experimental setup overview; (b) Test section consisting of the tested De Laval nozzle; (c) Schlieren visualization setup; (d) Schematic of the air vacuum system installed at SUT.

Table 1.

Components of the air vacuum system at SUT.

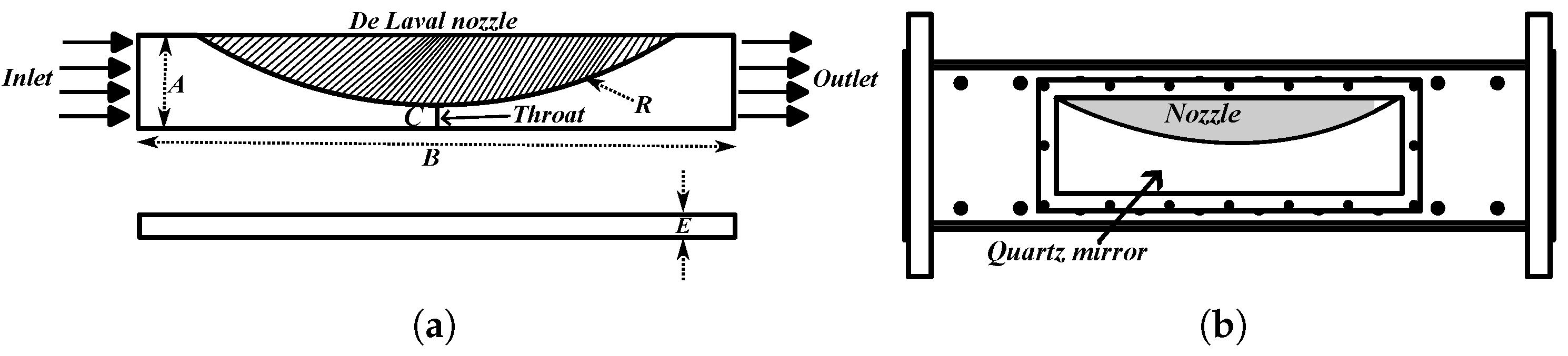

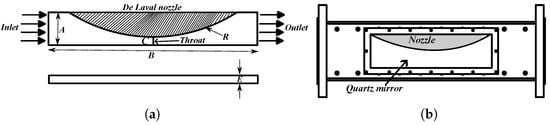

The test section size constrained by the maximum possible flow-rate (up to 0.2 kg/s) is fitted with a convergent–divergent De Laval planar nozzle to carry out the required flow measurements. Geometry related to the tested nozzle geometry and the fluid domain is notated in the top and front views presented in Figure 2a. This nozzle is a circular nozzle placed midway between the test sections. Dimensions related to the nozzle and domain geometry indicated in Figure 2a are provided in Table 2.

Figure 2.

(a) Nozzle profile and fluid domain specifications; (b) Test section.

Table 2.

Tested nozzle dimensions.

In order to support clear flow-field visualization across the visible and UV wavelength frequencies, the test section is fitted with a quartz shield (Figure 2b).

The experimental procedure was initiated by opening the motor-controlled valves (2, 3) to suck the ambient air through the inlet pipes (1), which were stored within the pressure chamber (5) meant for stabilizing the flow. The cut-off valve (4) meant to direct flow towards another test section was closed for the current experiments. Air from the pressure chamber was further directed towards the Roots blower (7) through the cut-off valve (6). The roots chamber further pumped the air towards the test section. Through the usage of a bypass duct and control valves (8–9), flow rate was regulated across the test section, leading to varied nozzle PR values across the nozzle. Beyond this, a temperature chamber (T) was used to maintain the desired temperature and humidity using a control valve (10). This air was further directed towards the test section (12) using the control valve (11). For testing, the bypass valve directed towards the test section was opened. This flow was maintained till fluctuations related to inlet flow parameters like pressure and temperature obtained a stable value. After the flow settled, a one-second window was selected to acquire the final data used for processing.

2.2. Experimental Measurement System

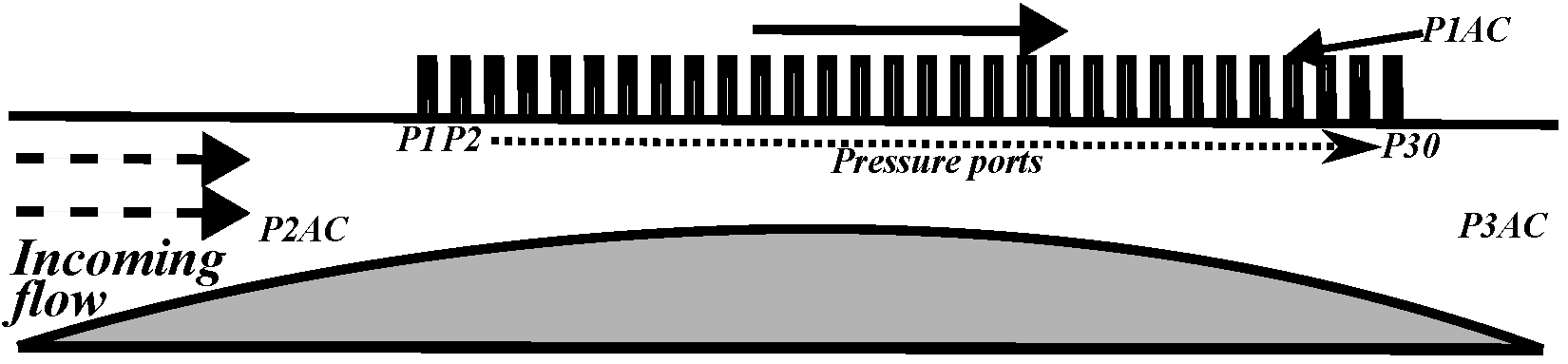

Two sets of measurement systems were installed while carrying out the experiments. The first system was used to measure the parameters related to the inlet conditions in order to ensure safe and repeatable operation of the stand. The second measurement system carried out measurements related to the nozzle flow. Data acquisition across the two systems was achieved using National Instruments’ NI/PXI-6255 module, which was connected to a measuring cluster. This cluster consisted of impulse tubes and screened cables connected to appropriate sensors and transducers to carry out the measurement of various flow parameters. Pressure measurement pertaining to the nozzle flow was accomplished using a series of pressure transducers (P1–P30) placed on the wall, as shown in Figure 3. The measurement system also consisted of three analog high-frequency pressure transducers (>10 kHz), synchronized with the Schlieren setup to capture in-sync instantaneous pressure and image data. The first high-frequency transducer, notated as P1AC, was placed close to the throat, P2AC was placed within the converging section, whereas P3AC was placed within the diverging section near the nozzle outlet (depicted in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pressure transducer ports for pressure measurement.

Considering the concurrence of shock-wave motion detection through Schlieren imagery and fast-response pressure measurements, as emphasized by Combs et al. in Ref. [43]), the current study implemented the basic knife-edge Schlieren technique to detect the density gradients associated with shock-wave oscillations [44]. The Schlieren setup presented in Figure 1c utilizes a pair of high focal length (200 cm) lenses (for increased sensitivity), a high-intensity–homogeneous LED spot illuminator, and a high-speed PHANTOM camera capable of recording videos at frame rates up to 100 thousand frames per second. The setup during the current study captured the frames at 6000 frames per second. The synchronized camera–illuminator system made use of a High Dynamic Range technique to appropriately measure changes in density, as well as light intensity variations within the flow.

The Schlieren technique relies on the deflection of point source light ( and ) across the knife edge. This deflection is dependent on the change in refractive index (n), which is further a function of density variation [44], as shown in Equation (1).

Here, L is the length along the optical axis, is the refractive index of the surrounding medium, and x, y are the axes along which a value is measured. The aforementioned light deflections ( and ) appear as varying gray-scale intensities across the Schlieren frame. Schlieren images for individual PR cases were obtained at 6000 frames per second, with each test spanning a duration of 1000 ms.

Data obtained from the Schlieren setup and actuators (described above) were managed using an in-house LabVIEW program. Subsequent to this preliminary data acquisition and manipulation stage, further processing of the data was carried out in MATLAB® Version 24.2 [45] to obtain the required shock-wave position and frequency spectrum plots.

2.3. Flow Conditions

As mentioned above, experimental studies were carried out for three different PRs. Specifications related to the three cases are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Investigated flow conditions.

Here, and are the total pressure and total temperature, whereas and are the test section outlet values, respectively. Ambient relative humidity was measured at ≈28% during these experiments. The variable PR was accomplished by varying the mass flow rate within the chamber, leading to higher PRs for increased mass flow rates. In order to represent a particular PR plot, results pertaining to the three PR cases will be represented as PR1.44, PR1.6, and PR1.81, respectively. Surface smoothness was achieved through appropriate surface machining and grinding, leading to minimal roughness, warranting minimal influence of roughness on the overall flow interactions. Further details regarding the measurement uncertainties associated with pressure and humidity measurements are provided in [41].

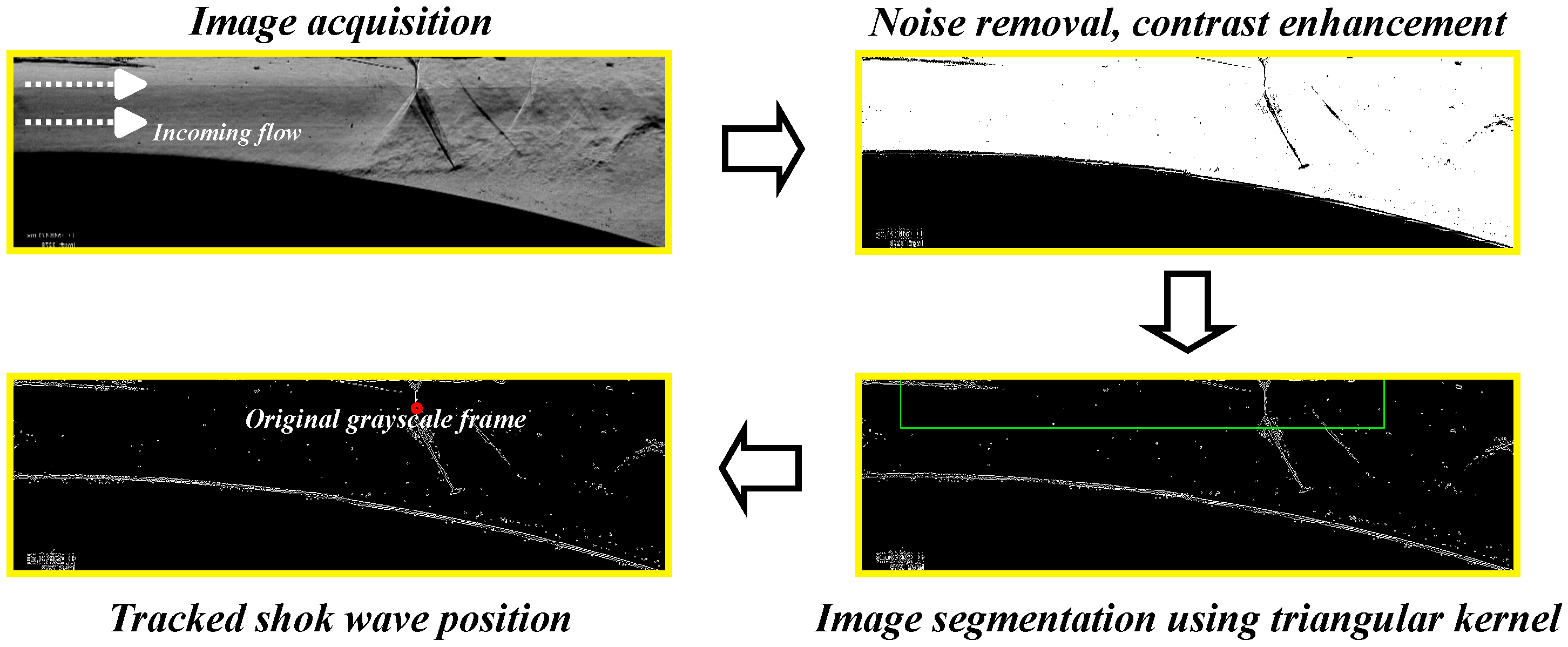

2.4. Digital Image Processing of Schlieren Frames

The Schlieren setup recorded a one-second plan-view video for the three cases. This video was sampled at 6000 frames/s (sampling rate: ) and processed using an in-house MATLAB® script to extract the location of the shock-wave front (which is also called the inviscid shock-wave component or Mach disk). Since the location of this primary shock wave determines the location of the entire shock-wave structure [46], it was assumed that understanding the unsteadiness related to its position would capture the low-frequency oscillations related to SBLIs, as elaborated earlier in Ref. [47].

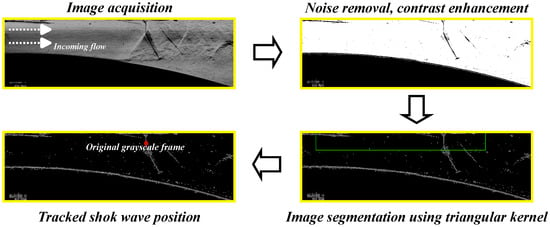

The overall process of carrying out this detection is described in Figure 4, implemented using the image processing toolbox in MATLAB version 2024b. This process is initiated by converting the video into digitized frames captured at an interval of μs, in the form of time-resolved RGB matrices. These RGB images are converted into grayscale images. Shock waves are defined by thin lines of steep pressure or density gradients. The presence of these steep gradients is displayed as a sequence of bright and dark regions [17] in Schlieren images, leading to the formation of unequivocal pixel gradient lines within the frames. The implemented code aimed to detect these lines through the usage of an appropriate edge detection technique. However, before applying the required image segmentation, the frames were pre-processed to remove noise and carry out image contrast enhancement. This stage involved convolution of the images with high-frequency filters, leading to enhancement of edges, followed by contrast enhancement to make the shock-wave edges more prominent. The images were further moderately smoothed using a Gaussian filter (standard deviation, ) technique to suppress fine noise pixels within these images. Through these steps, shock-wave edges in the frames were enhanced, leading to an efficient shock-wave detection code.

Figure 4.

Flow-chart to carry out digital image processing of Schlieren images to detect shock-wave position. Green box in the bottom-right image is a small pre-determined sliding rectangular kernel, wherein the segmentation was carried out to detect the position of shock waves.

In order to detect the location of these shock-wave edges, image segmentation using the Canny algorithm [48] was carried out. This has been utilized previously in numerous shock tracking investigations [47,49], due to their robustness and effectiveness in capturing abrupt changes in pixel intensity. In order to neglect the outlier edges detected within the segmented image, a sliding window-based shock detection method is utilized, wherein a small sliding rectangular kernel is applied across a predefined portion of the image to identify regions with maximum summed pixel values. The portion corresponding to the maximum summed pixel values is labeled as the location of the Mach disk. In order to avoid spurious edge detection, the kernel was moved only within the rectangular portion specified in Figure 4. This method is robust to noise, adaptable, and effective even if the shock-wave edges are not sharp. The shock-wave position obtained using the implemented technique was further processed to obtain the mean position of the shock wave with respect to the throat, which was further non-dimensionalized using the throat height. The mean shock-wave position was further used to normalize the time-resolved shock-wave position about the mean position. This normalized shock-wave position data and digitized time-resolved Schlieren images were further processed using spectral analysis tools described henceforth, to discern the underlying spectrum and correlation dynamics pertaining to different interaction regions. A brief uncertainty analysis on image-based shock-wave position data emphasized an uncertainty of less than , establishing the accuracy of the employed technique to capture the shock-wave position.

2.5. Spectral Analysis of Pressure Data and Shock-Position Data

FFT has been a preferred methodology to carry out unsteadiness analysis across several disciplines since 1965 [50], including spectral segregation with respect to SBLIs [7,14]. This method involves deciphering the magnitudes of dominant overtones within the flow unsteadiness by parlaying the time-resolved signal into discrete frequency amplitudes. To that end, this paper made use of FFT to evaluate the square root power spectra of the individual waves embedded in the signal as a function of frequency in the form of frequency spectrum and power-spectral density (PSD) plots. In the first stage, time-resolved pressure data were converted into the respective frequency spectrum plots. Further details regarding the adopted methodology can be gleaned from Ref. [17]. This process has been repeated for the three PR cases to provide an overview of how the dominant tones shift and vary with different PR values.

In a later section, FFT was implemented on shock-wave position data for the three PR cases to derive the pertinent PSD distribution plots. This was followed by a smoothing operation to identify the associated prominent frequency peaks. The averaging was carried out by using a variable moving average scheme across the spectrum, as listed in Table 4. The symbol represents the Nyquist frequency, which is Hz, and is the frequency resolution, which is 1 Hz.

Table 4.

Smoothening operation for PSD data obtained using shock-wave position data.

2.6. Spectral Analysis Using Wavelet Transform of Pressure Data

The spectral content from FFT analysis of a signal is a time-averaged overview of the underlying frequency spectrum [6]. Due to the underlying time-averaging of the localized features, FFT leads to the loss of critical temporal information about the underlying flow features localized in time. Its output could be considered to present an accurate picture of the associated frequency spectrum, if the flow is stationary or ergodically periodic, measured over a long time. However, flow related to SBLIs is complex and characterized by multi-scale, non-stationary fluctuations, and thus warrants the need to carry out spectral analysis that provides frequency segregation of the flow signature, as well as temporal evolution of these components. One such method being used across several applications [51], including SBLIs [6,32], is the Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT). Due to its temporal resolution feature, CWT provides the ability to capture intermittency, as well as time-stamped modulation of the complex flow-field signal, providing a microscopic overview of the features involved.

The wavelet transform of a time-varying signal g(t) is given by:

where , , and are the mother function, wavelet scale, and time-translation parameters, respectively. The mother function is scaled and time-translated along the signal to enable visualization of the amplitude of different frequency components and also present the time evolution of these features. Further information regarding the process and elements involved can be gleaned by the readers from Ref. [52]. In a nutshell, the process involves convolving the narrow temporal window data with mother function variants generated by scaling in frequency and shifting in the time domain, and hence extracting the associated time-evolving frequency spectra. Out of the plethora of wavelets, the current paper makes use of the complex Morlet function, which is a time-limited modulation of a sinusoidal function with a Gaussian envelope [32], described in Equation (3).

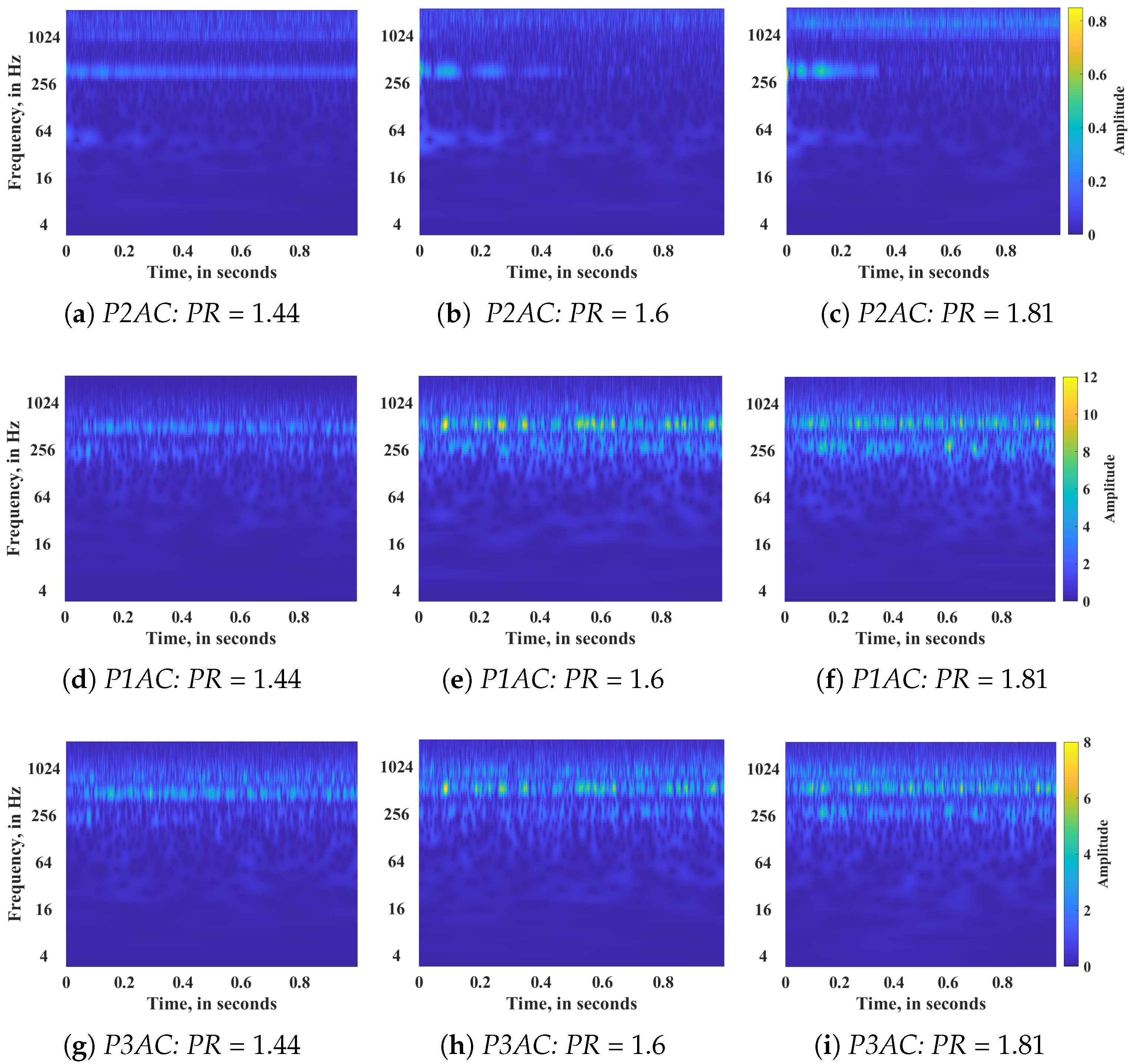

where is the non-dimensional frequency. The Morlet transform has been attributed to produce arbitrarily high resolution in frequency, as well as the temporal domain, compared to other mother functions [6,51]. This mathematical tool was used to derive the time-evolving spectral plot of pressure data. The output from such a transformation is presented later as excerpts of the scalogram contour distribution plots in Section 3.5, wherein individual scalogram plots were derived by calculating the modulus of the Morlet transform, . Comparison of the individual scalogram plots will provide insights into the time evolution and spectral variation of underlying flow interactions located at different regions within the flow.

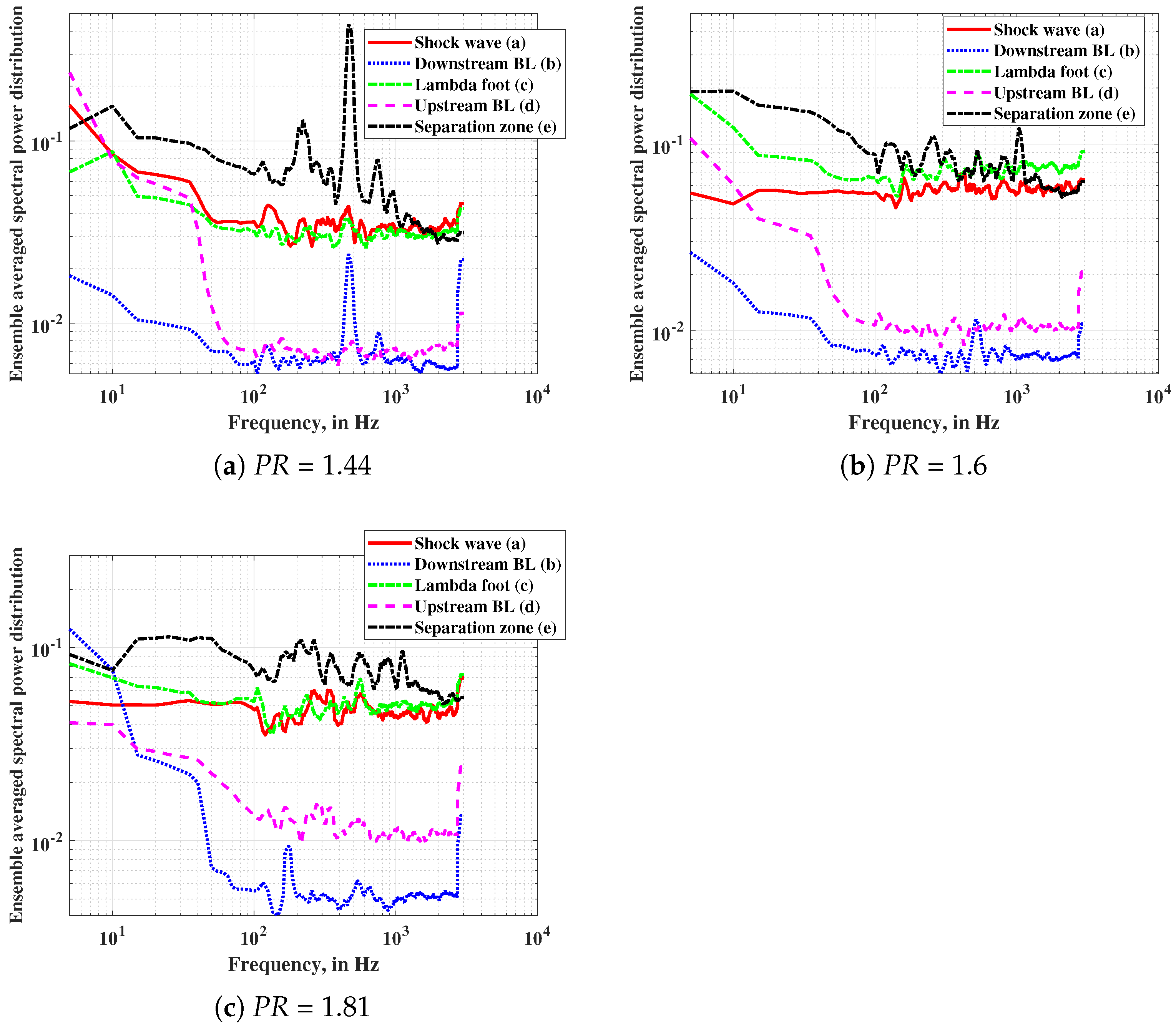

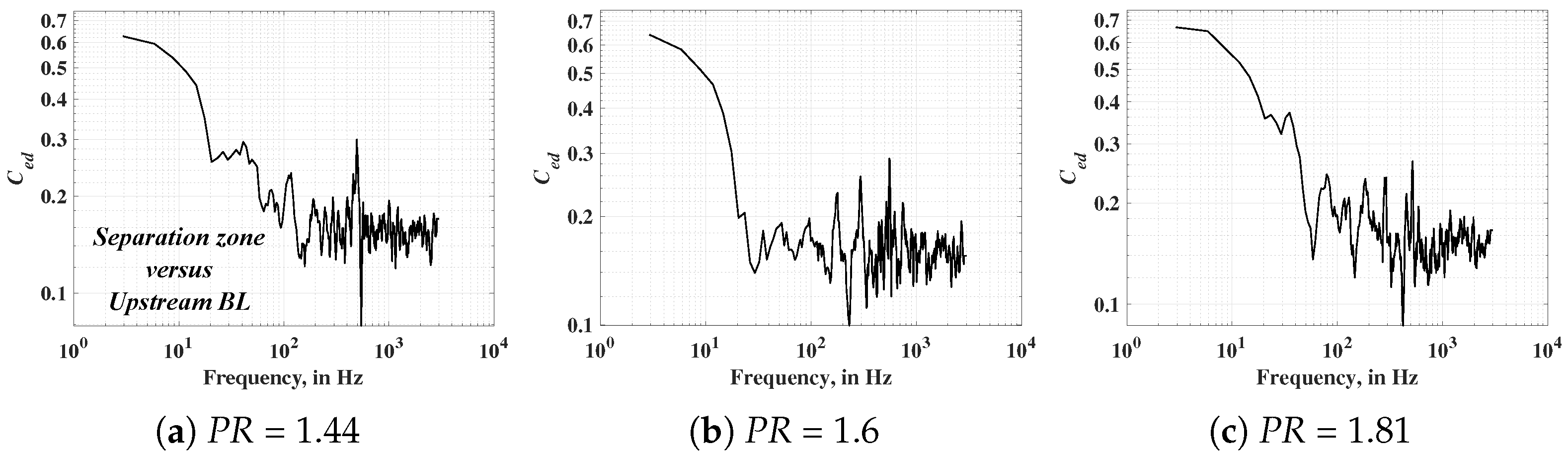

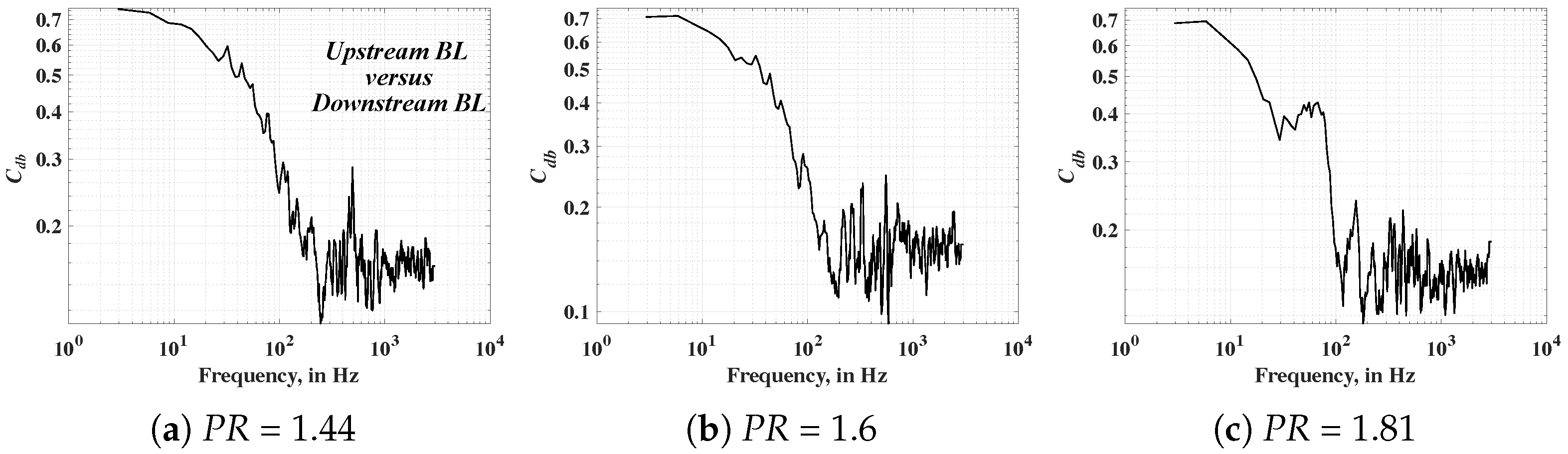

2.7. Spectral Analysis of Interaction Regions: Spatial FFT

Spectral analysis of the pressure data and shock-wave position data described heretofore provided an overview of unsteadiness associated with the global shock system. However, given the non-homogeneous characteristic of SBLIs, spectral analysis of pixel densities associated with the different regions, namely, separation region, upstream boundary layer, downstream boundary layer (beyond the reflection shock), separation shock, and Mach disk, would be imperative to capture the energy distribution between different interaction regions. Thus, time-sequence Schlieren images were extracted and processed to evaluate PSD pertaining to different regions for the three PR cases. This analysis, carried out using MATLAB version 2024b, implemented the Welch’s method [53] to carry out the spectral evaluations.

This process involved the selection of a particular image, followed by the selection of pixel points within the region being analyzed. The time-resolved grayscale values at these selected points are filtered using a low-pass fifth-order Butterworth filter with a cut-off frequency of 1 Hz less than to remove high-frequency noise, as well as the DC component within the pixel signals. This pixel-specific time-stamped filtered signal is further transformed into PSD using the windowed FFT method [53]. This windowed FFT made use of 1200 samples per segment, followed by the usage of a Hamming window to avoid spectral leakage. This windowed FFT leads to a reduction of random noise components while providing a smoother PSD plot at the expense of relatively lower-frequency resolution (5 Hz). The individual FFT plots are averaged for the different sets of FFT plots at every frequency. Analogous to PSD data pertaining to shock-position data discussed in Section 2.5, the averaged FFT data in this analysis was also smoothed using a variable moving average scheme elaborated in Table 5. This process of deliberating FFT plots associated with different spatial regions within the flow has been coined as ‘spatial FFT’.

Table 5.

Smoothening operation for PSD obtained using time-resolved pixel data at different region-specific pixel locations.

This process was repeated for five different pixel locations placed in close proximity to each other for a specific region. The output of averaged PSD plots from these pixel locations was ensemble-averaged to determine the overall PSD plot corresponding to different regions of the interaction. In the study, five pixels were selected on an image for a specific region. The time-resolved pixel intensities on these points were further divided into 9 segments, leading to the evaluation of 9 individual spectra for each pixel. Thus, a total of 45 individual spectra were calculated for a specific region. These 45 sets of PSD data were ensemble-averaged to determine the final PSD plot. This method leads to improved signal-to-noise ratio, especially in the regions of maximum density gradients like shock-wave structure, separation bubble, etc.

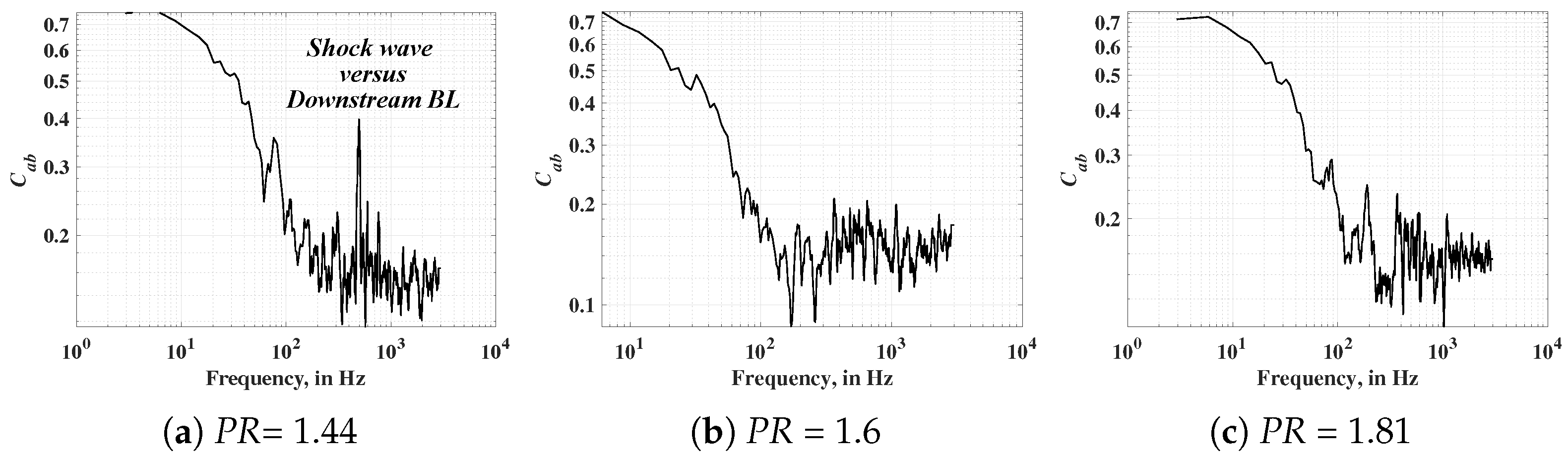

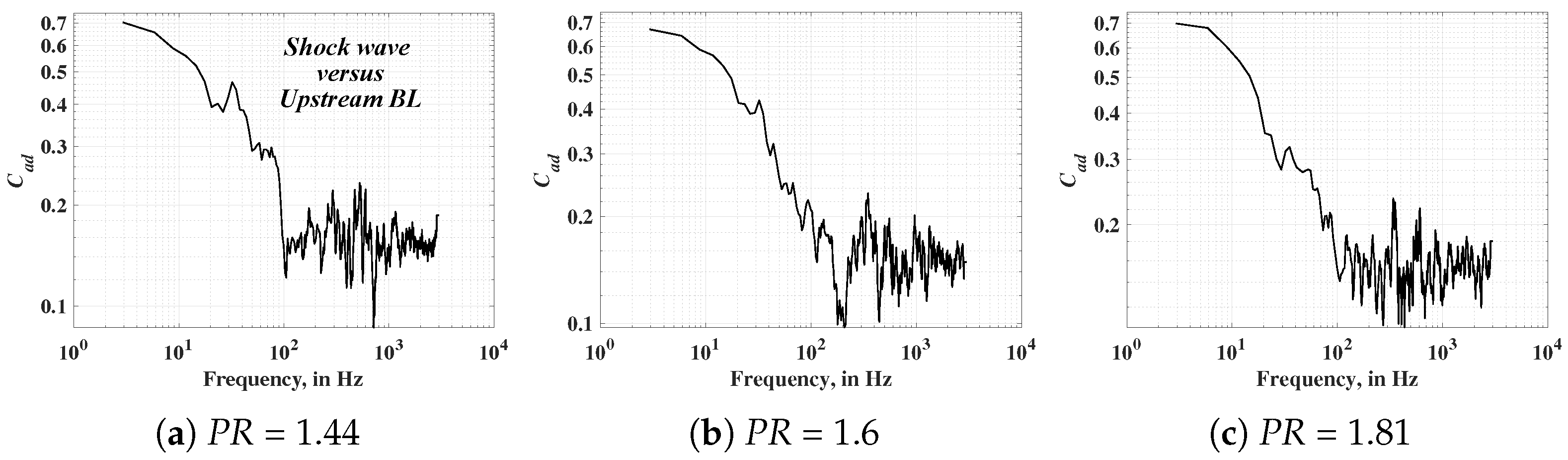

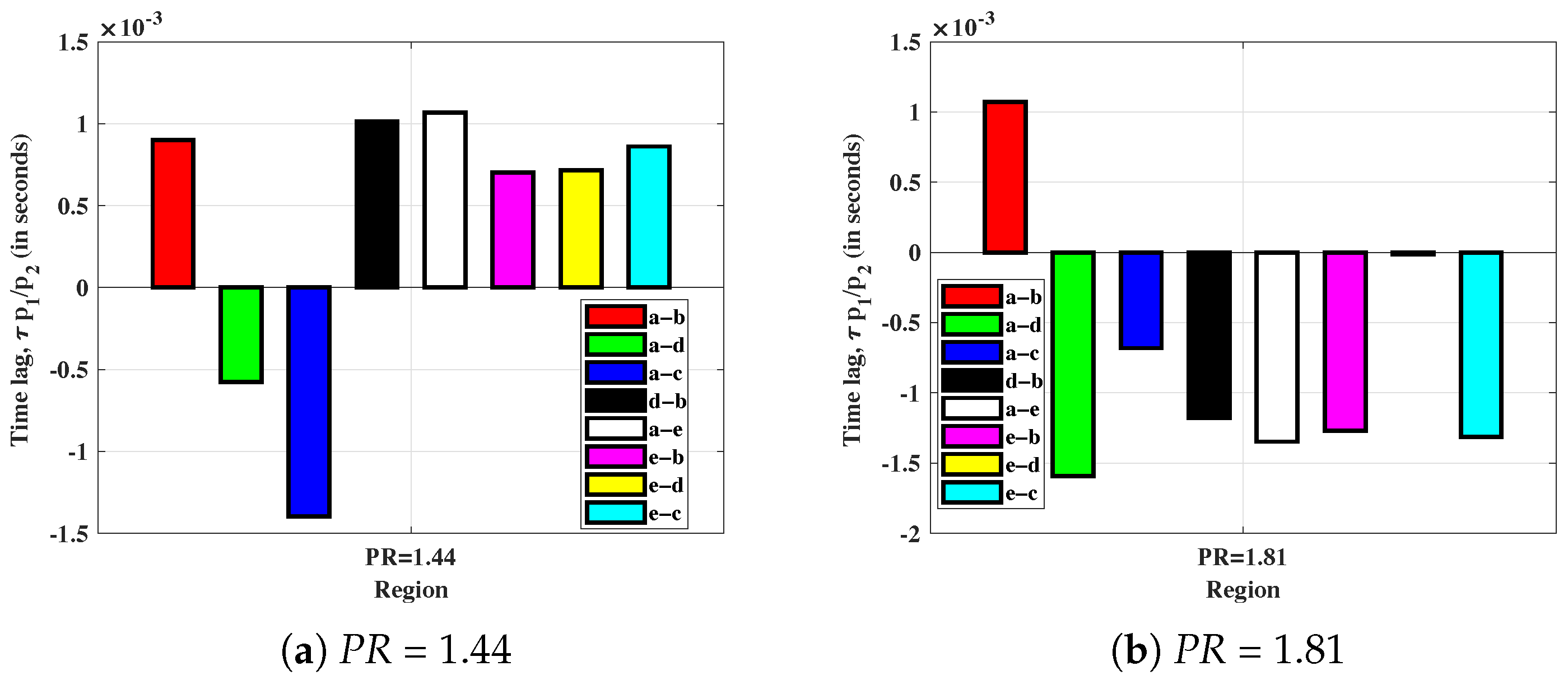

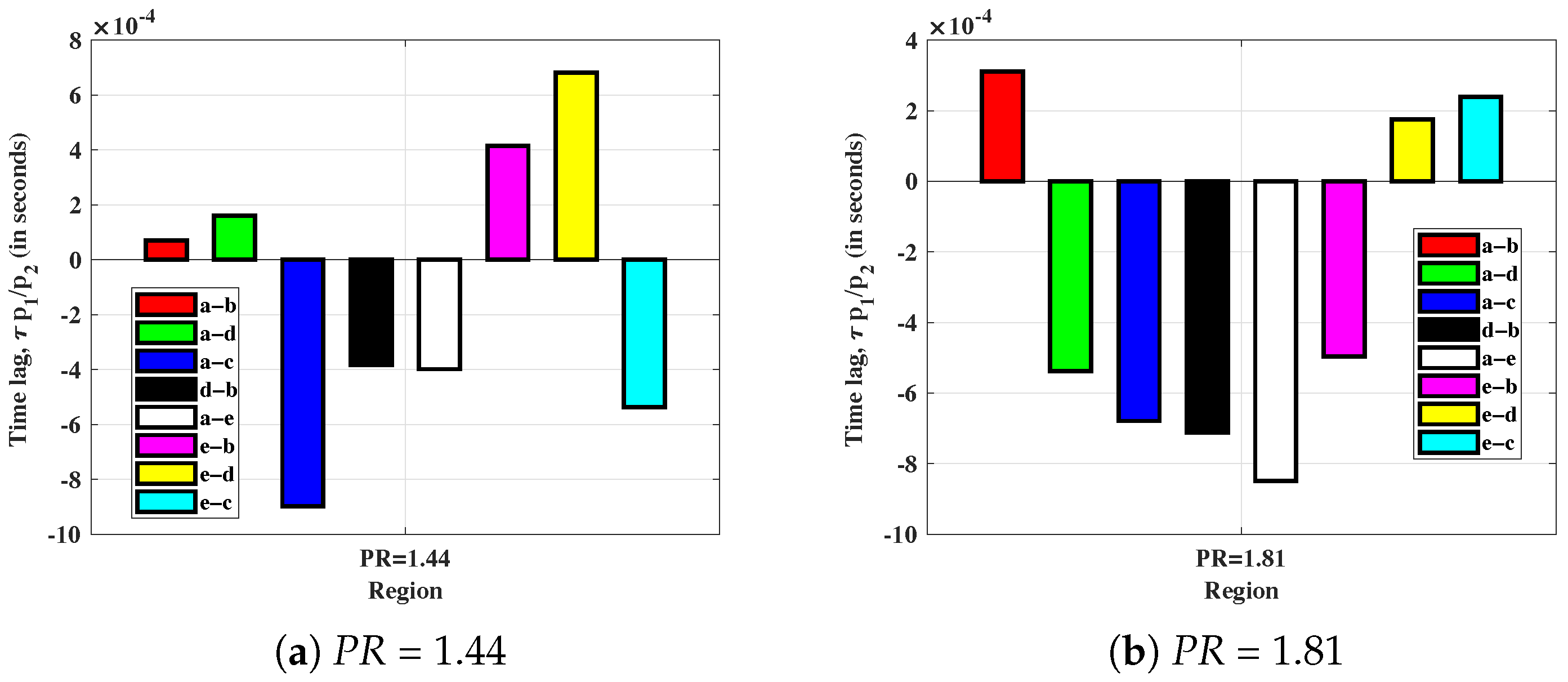

2.8. Coherence and Time-Lag Analysis of Pixel Intensities Corresponding to Different Regions

Coherence is a measure of correlation between two distinct signals as a function of frequency, and magnitude-squared coherence is a measure of this coherence. For instance, magnitude-squared coherence () values between time-sequence pixel intensities pertaining to regions and will be computed by Equations (4)–(6).

In these equations, is the cross power spectral density, and are the power spectral densities of the two signals, whereas is the square of magnitude spectrum at different frequencies within the frequency domain. The output of these equations is a set of values at different frequencies. A higher value of is indicative of increased correlation between the two signals at a specific frequency.

Another measure of correlation between two signals is termed the time lag (). A positive is indicative of value occurring before . It is calculated as follows:

where is the phase lag between the two signals at a specific frequency. This phase lag was calculated using the real and imaginary components of at different frequencies.

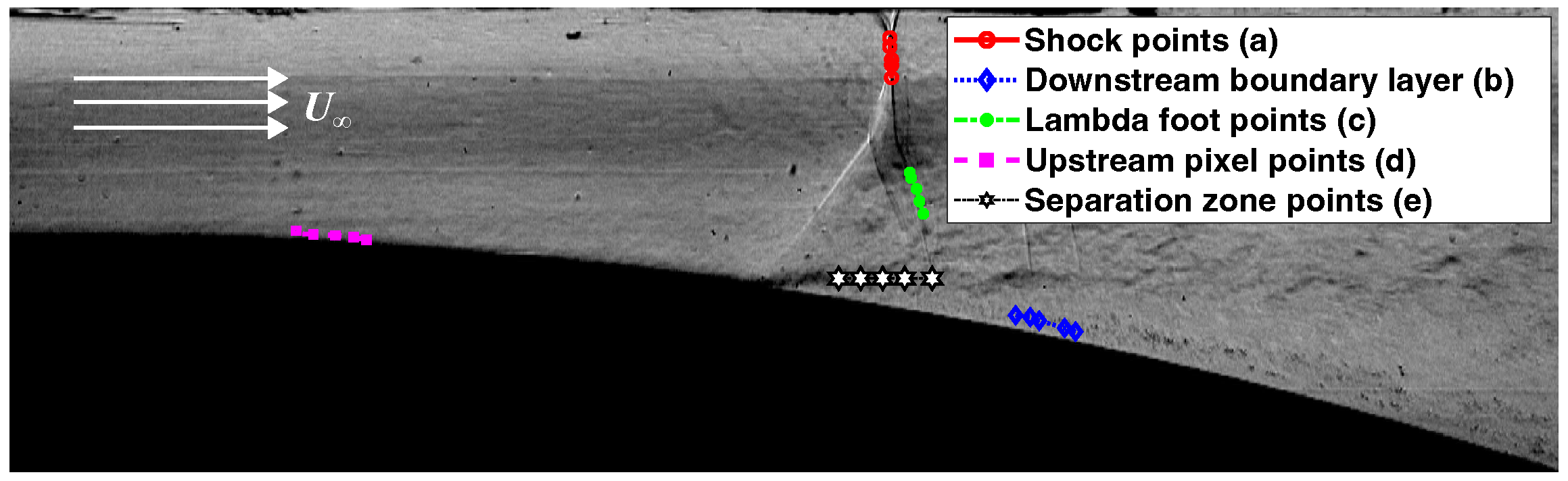

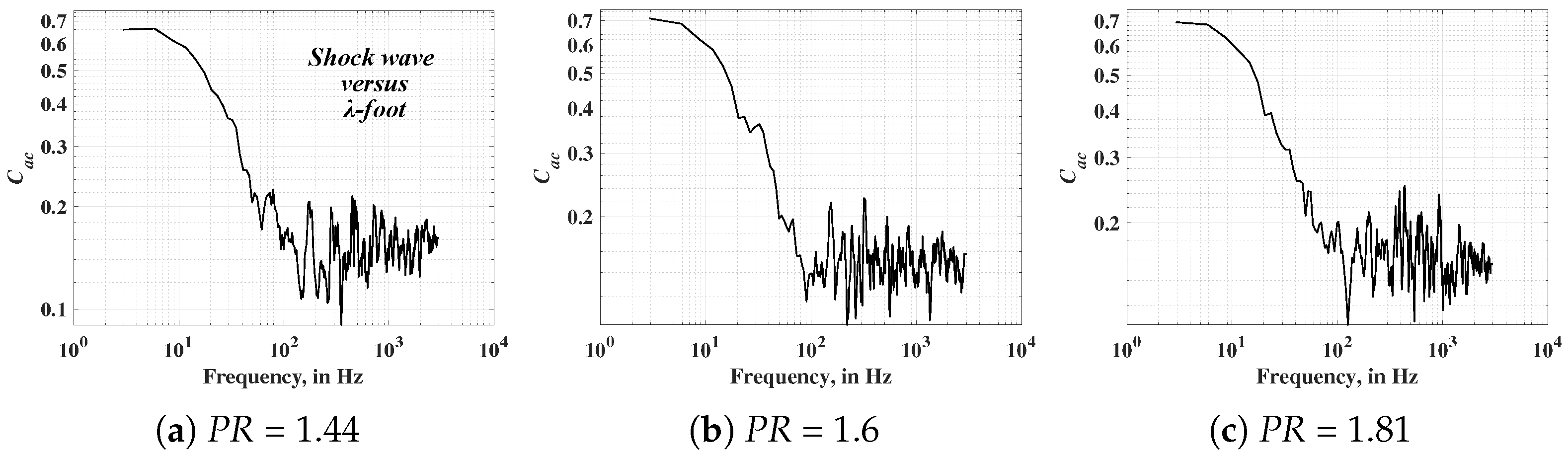

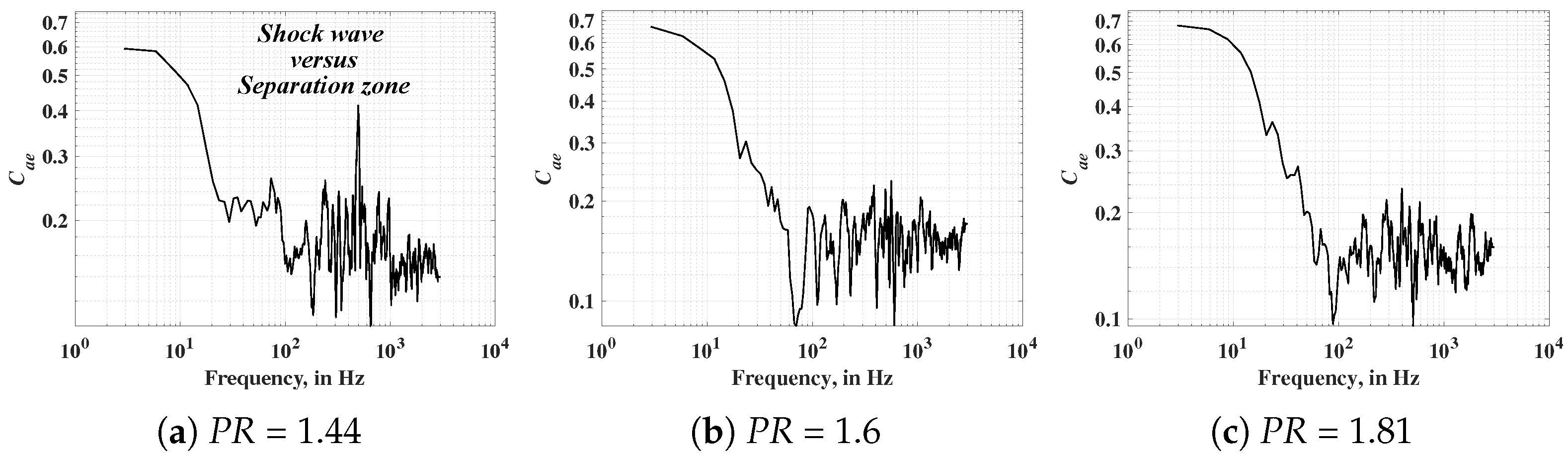

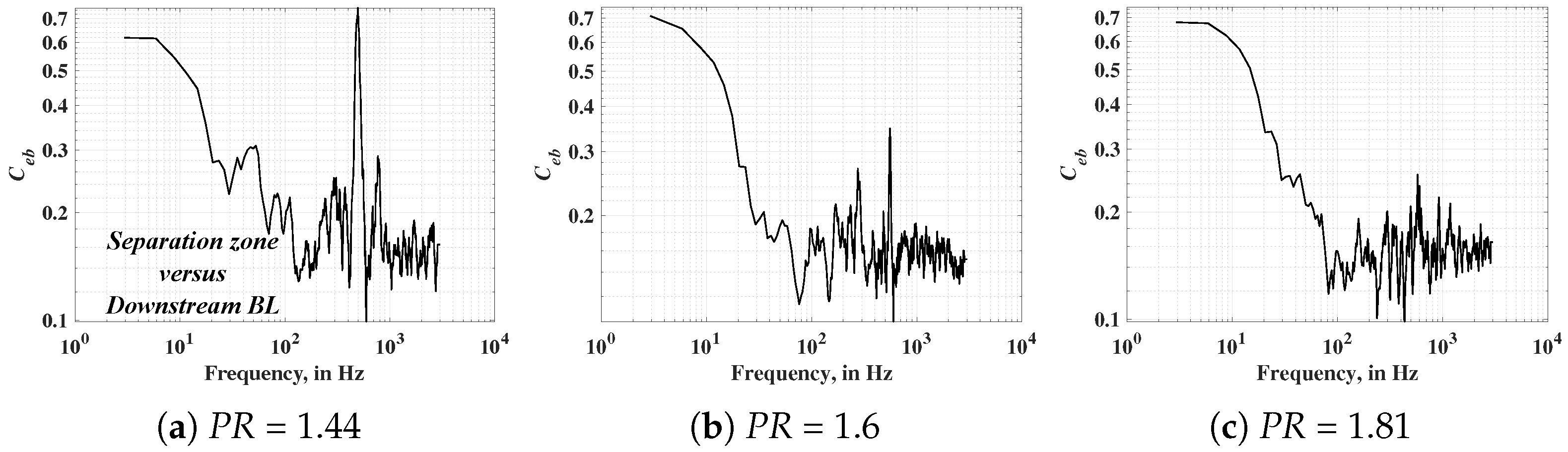

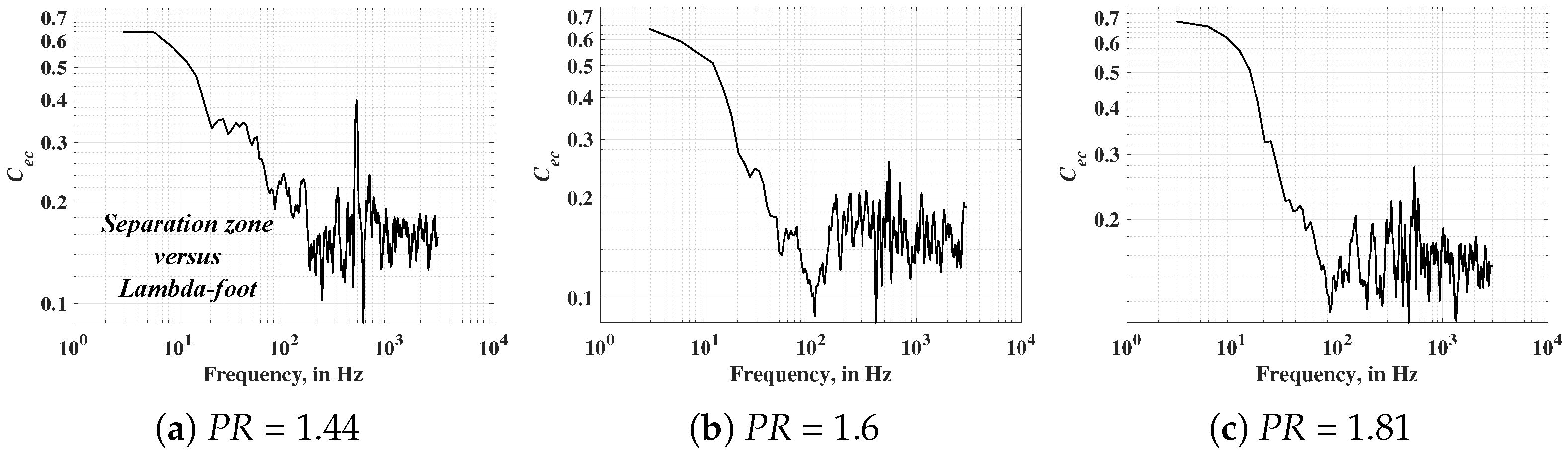

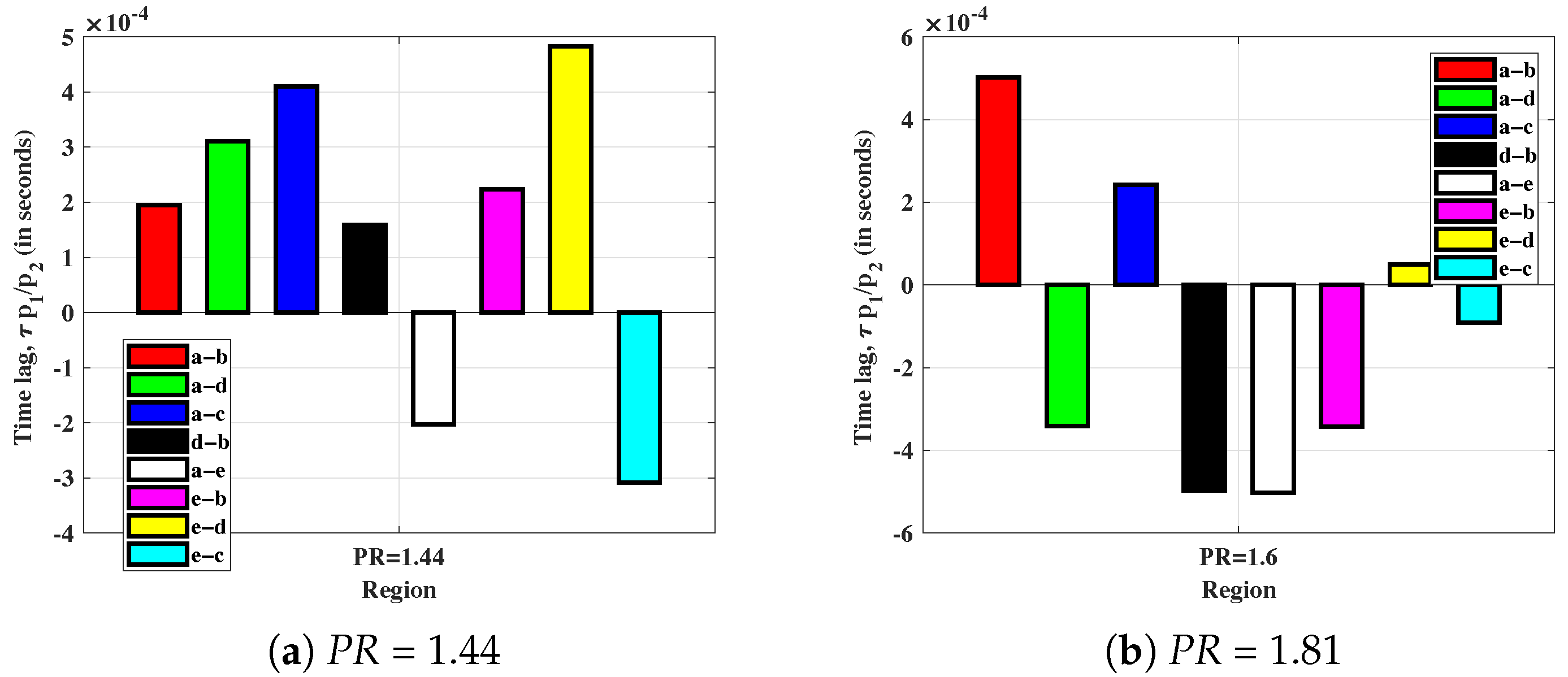

In the current numerical setup, these quantities have been evaluated by comparing time-resolved pixel intensities corresponding to inviscid normal-shock-wave location, downstream boundary-layer (downstream BL) pixels, downstream -foot pixels, upstream boundary-layer pixel (upstream BL) values, and separation-region pixel values. The identifiers corresponding to different regions are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Different interaction zones being explicitly analyzed for spectral distribution and correlation analysis.

Coherence and time lags pertaining to comparison between different regions were identified using the variables (Equation (4)), and (Equation (7)), respectively, with and being identifiers for the regions being compared, as shown in Figure 5. For instance, coherence and time lag between the shock-wave-region pixel (denoted by alphabet a) and downstream-boundary-layer pixel (denoted by alphabet b) values will be denoted as and , respectively. The complete process of estimating coherence and time-lag values, implemented through in-built MATLAB functions, is as follows: five pixel values from the respective regions indicated in Figure 5 were selected, time-sequence pixel intensities for the five pairs of signals were filtered using a fifth-order Butterworth filter, and saved as vectors. Magnitude-squared coherence and time-lag values were evaluated for every pair of pixels from the two regions. These five pairs of values were subsequently ensemble-averaged and smoothed to find the final set of coherence and time-lag values.

2.9. Numerical Methodology and Simulation Setup

To complement the experimental investigations of low-frequency oscillations, spectral signatures, and coherence of shock–boundary-layer interactions, a set of transient numerical simulations was carried out. While the experimental campaign provides direct access to time-resolved pressure signals, Schlieren imagery, and their spectral decomposition across frequency and spatial domains, numerical modeling offers a controlled framework for interrogating the underlying flow physics under identical operating conditions. In particular, the numerical simulations serve two objectives: first, to assess whether a computationally efficient RANS-based formulation can capture the large-scale unsteadiness observed experimentally; and second, to provide additional insight into flow-field quantities, thereby strengthening the interpretation of spectral analysis, wavelet decomposition, and coherence evaluations. Within this context, ANSYS Fluent 2024 [54] was employed to solve the three-dimensional, compressible Navier–Stokes equations within the Reynolds-Averaged (RANS) approach [55] for the nozzle configuration under consideration, with the modeling details summarized as follows.

The governing equations of continuity, momentum, and energy were spatially discretized using the finite volume method and solved using the pressure-based coupled algorithm, which simultaneously resolves pressure and velocity fields. To ensure stable pressure–velocity coupling on collocated grids, the Rhie–Chow momentum interpolation method [56] was employed, which constructs face velocities using a momentum-based correction to avoid checkerboarding artifacts and enhance numerical stability. Air was modeled as an ideal gas, with density computed from the equation of state, establishing a coupling between pressure and temperature. Convective terms in the density, momentum, and energy equations were discretized using the second-order upwind scheme, while the turbulence transport equations for turbulent kinetic energy (k) and specific dissipation rate () were discretized using the QUICK (Quadratic Upstream Interpolation for Convective Kinematics) scheme [57]. QUICK offers third-order spatial accuracy on structured meshes by blending central differencing and upwind biasing, improving gradient resolution while limiting numerical diffusion. Turbulence was modeled using the shear stress transport (SST) variant of the k– model [58], with the turbulence equations solved in a segregated fashion, independently from the coupled system of flow equations. Temporal discretization employed a bounded second-order implicit formulation to enhance accuracy and maintain stability in unsteady simulations. Molecular viscosity was held constant throughout the calculation.

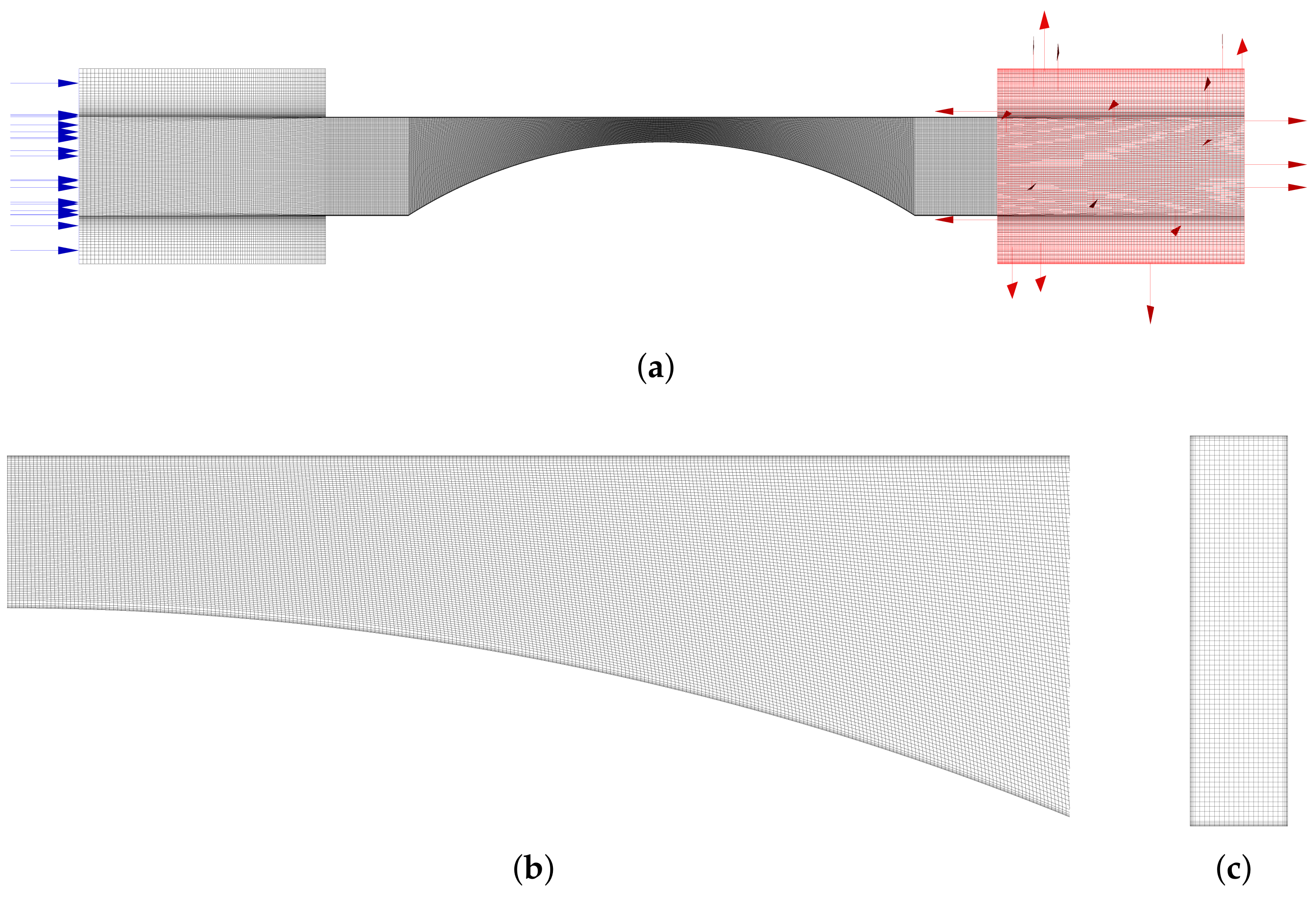

A structured, multi-block mesh was generated using ANSYS Mesher to discretize the computational domain. The mesh is divided into three distinct zones: an inlet section, a central channel region, and an outlet section, as shown in Figure 6a. The entire mesh consists exclusively of hexahedral cells to maintain high numerical accuracy and low numerical diffusion, particularly important for resolving flow gradients in compressible regimes. The mesh is static (non-adaptive) and remains unchanged throughout the simulation. The central channel block, which encompasses the separation point and the Mach disk formation region, was refined to provide higher spatial resolution where flow features are most sensitive. A close-up of this section can be seen in Figure 6b. This refinement is symmetrically applied both upstream and downstream of the neck—the narrowest section of the geometry—to accurately resolve shock interactions, expansion waves, and flow instabilities. The structured topology supports the use of high-order spatial discretization schemes, further enhancing solution fidelity in critical areas. In the wall-normal direction, a structured boundary layer mesh is implemented along the entire channel region; its cross-section is shown in Figure 6c. The boundary layer consists of five hexahedral layers confined within a 1 mm wall-normal distance, and the first cell height adjacent to the wall is 75 μm. Although the boundary layer mesh was designed to provide some near-wall resolution, the preliminary mesh configuration results in a non-dimensional wall distance of approximately in the channel region. This coarser mesh was used in the early stages of the study to explore qualitative flow behavior and identify dominant flow features. For near-wall turbulence treatment, wall function based on correlation was employed, which allows for reasonable modeling accuracy even when the first cell lies in the buffer layer or lower log-layer. Despite the relatively coarse resolution near the wall, the simulations yielded promising results, capturing key flow structures and oscillatory phenomena consistent with expected characteristics, thereby validating the mesh for initial investigative purposes.

Figure 6.

(a) Overview of the structured multi-block mesh discretizing the computational domain, including the inlet (left), central channel region (middle), and outlet extension (right). Velocity vectors are shown at the inlet (blue arrows) and outlet (red arrows) boundaries to indicate flow direction. (b) Close-up view of the refined mesh in the central channel region near the narrowest section (neck), highlighting the hexahedral cell distribution optimized for resolving shock and flow features. (c) Cross-sectional view of the structured boundary layer mesh along the channel wall, showing the five hexahedral layers with the first cell height of 75 μm, designed for near-wall turbulence resolution.

A circular pressure inlet boundary condition was applied at the upstream end of the computational domain. The inlet, with a diameter of 0.15 m, is located 0.2 m upstream from the channel entrance and forms the base of a cylindrical extension that connects to the main channel. This upstream extension was introduced to allow the inflow to develop properly and to prevent the artificial influence of the boundary condition on the flow inside the channel. At the downstream end of the channel, a similar cylindrical extension is attached, serving as the outlet region. All surfaces of this outlet cylinder—except the one where the channel exits—are defined as pressure outlet boundaries. This configuration minimizes backflow or reflection effects at the outlet, ensuring that the downstream boundary does not adversely influence the internal flow within the channel. The static pressure and temperature values prescribed at the inlet boundary were carefully set to replicate the conditions experimentally measured at the entrance of the channel for the three pressure ratios investigated. This approach ensures that both the thermodynamic and flow conditions entering the domain closely resemble those observed in the physical experiments, thereby improving the fidelity and relevance of the numerical results. Similarly, the outlet boundary conditions, including static pressure and temperature, were assigned to match the corresponding experimental measurements, minimizing artificial reflections and ensuring a physically consistent flow development through the domain.

3. Results and Discussion

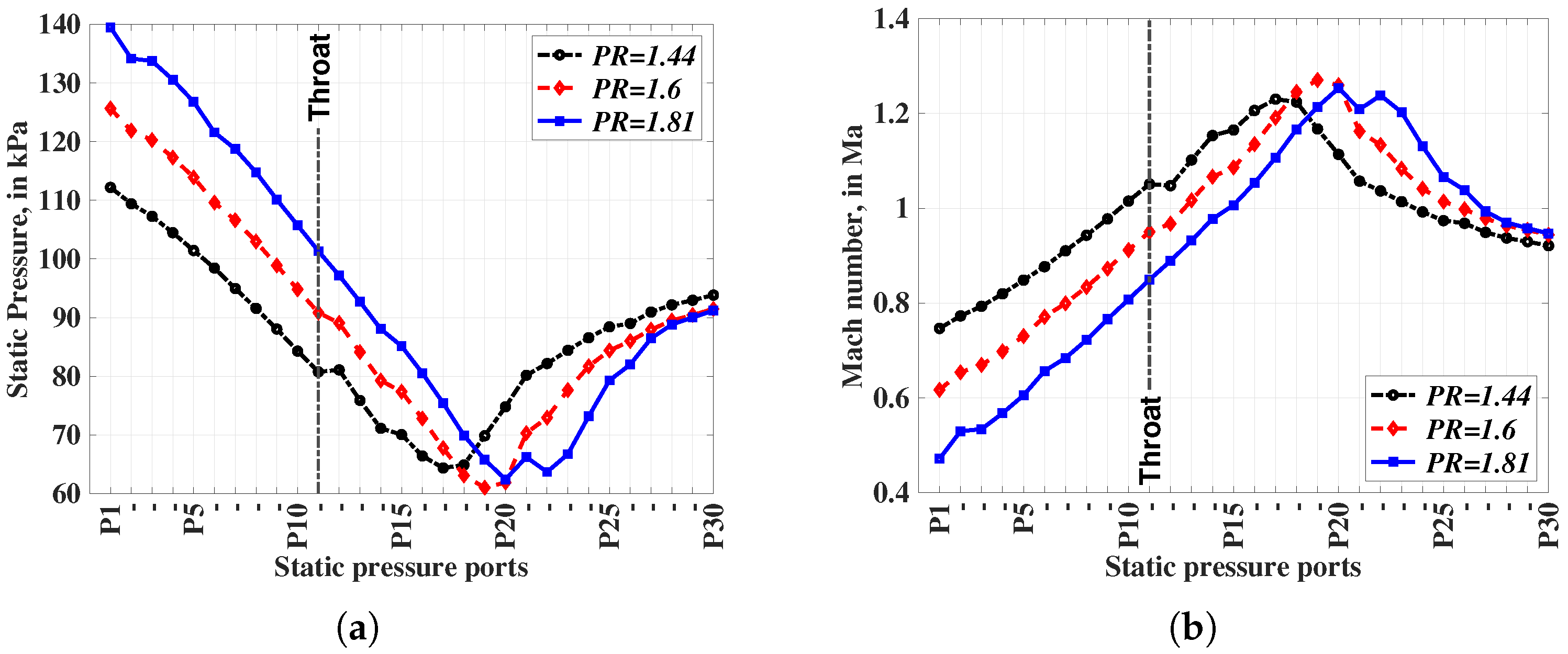

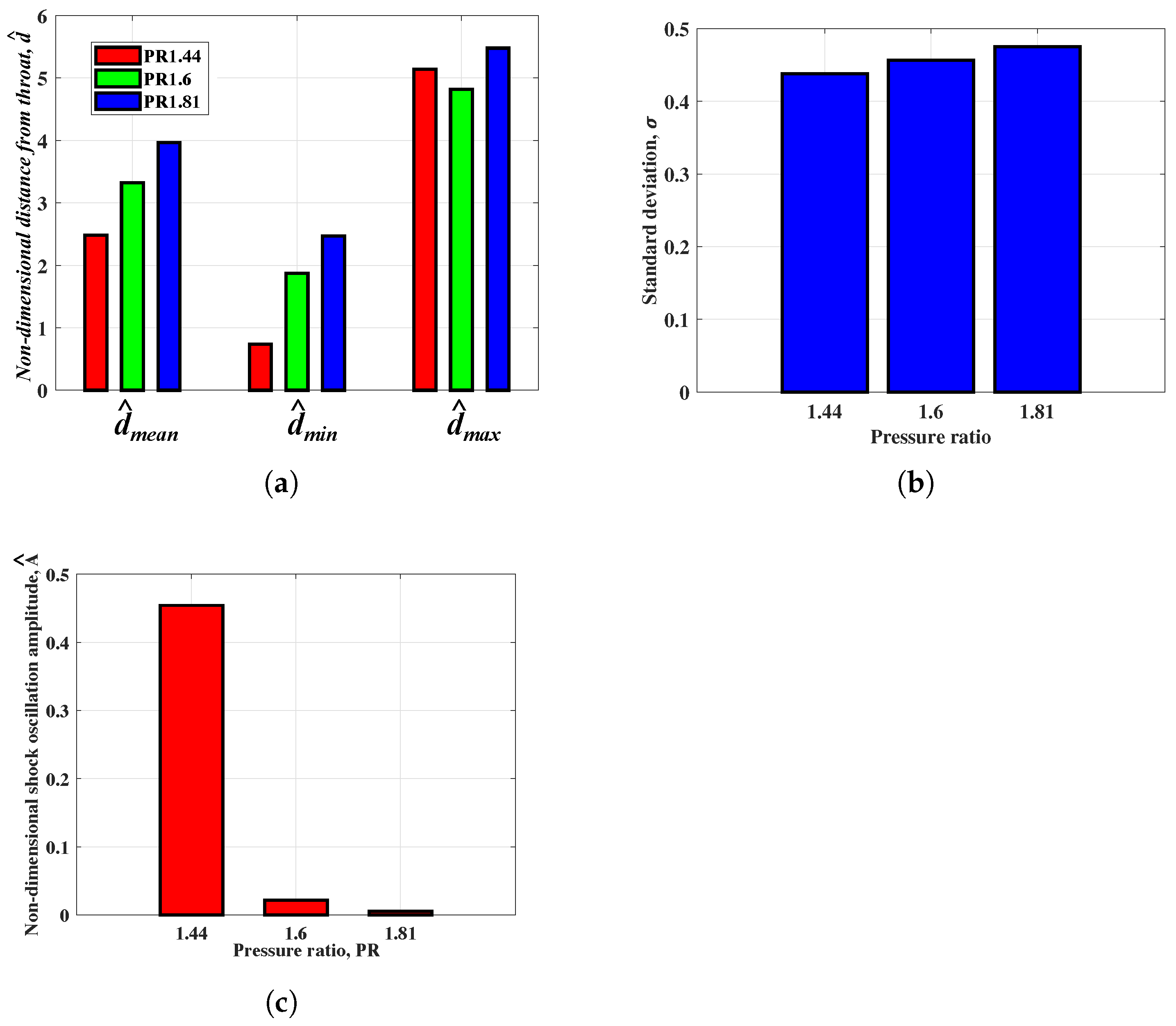

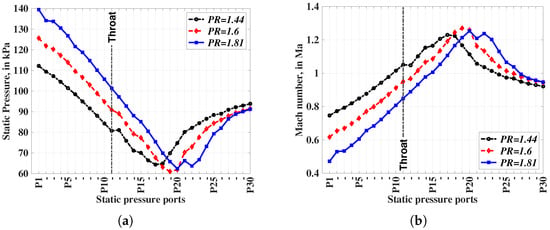

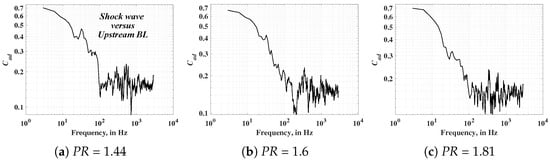

3.1. Analysis of Pressure and Mach Number Variation Within the Nozzle

Plots in Figure 7a illustrate the variation of static pressure (P) along the nozzle length for the three PR cases. The three plots demonstrate the presence of a “classic” trend associated with nozzle flow comprising expansion, sudden shock compression, and recovery [35]. The expansion occurs within the converging section, as well as some distance beyond the throat. However, due to the presence of overexpansion, shock waves are generated within the diverging section for all the cases, leading to a sudden increase in the P value between ports P17 and P22. It can also be seen that as PR increases, pressure measured at port P1 increases. This leads to P being higher for increased PR within the entire converging section. It can also be seen that the generation of shock-wave compression for the higher PR occurs at a later distance from the throat. This leads to the generation of a steeper pressure gradient for higher PR, which would further indicate the presence of increased flow separation for higher PR, leading to increased impact of flow separation on the shock-wave structure. The plot pertaining to PR1.81 demonstrates the presence of two spikes in p values, leading to the presence of two humps. This is characteristic of a -foot shock structure [59]. Due to the increased separation shock intensity for higher PR, the flow downstream of the first shock remains supersonic, leading to the development of expansion fans and compression shocks. Due to this, the pressure recovery is delayed significantly for higher PR. However, beyond these bumps, the value of P starts recovering. The convergence of p values at for all three cases, despite differences in the downstream compression shock position and the delayed onset of pressure recovery for higher PR, further indicates that a higher PR results in a stronger adverse pressure gradient, leading to increased flow separation intensity. This increased flow separation instability feeds the complex SBLI dynamics.

Figure 7.

Averaged streamwise variation of flow parameters for varying PR: (a) Static pressure variation, (b) Mach number variation.

Plots in Figure 7b present the Ma variation along the nozzle for three cases. These values were calculated by applying isentropic relations to the aforementioned p values. The value of Ma associated with the three cases increases within the converging section and up to a finite distance downstream of the throat, beyond which it starts to reduce due to the formation of shock waves, and ultimately converges to similar values at port P30. Ma reduction is steeper and occurs at a lower Ma for lower PR values, as they are dominated by inviscid normal shock-wave phenomena resulting in a steeper flow deceleration. It is also noticeable that the higher PR amounts to higher Ma values within the nozzle, followed by a slower deceleration beyond the shock wave. The higher amounts to increased bulk momentum of the incoming flow, which has a significant impact on the origin of SBLIs, and hence the underlying unsteady interactions. The presence of two bumps for PR1.81 is again indicative of an increased impact of the separation shock, leading to the formation of oblique shocks, and hence the gradual shock-induced deceleration.

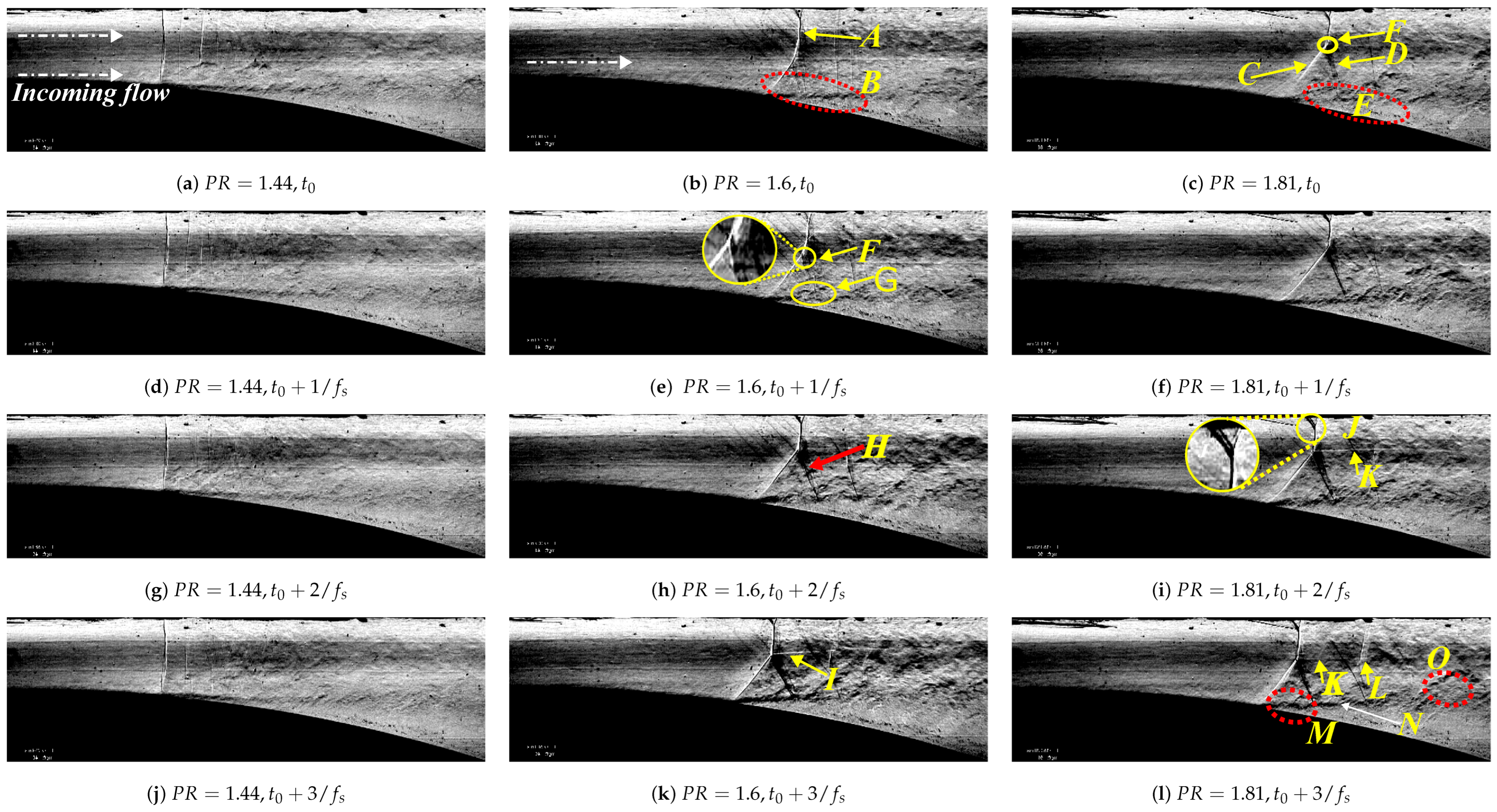

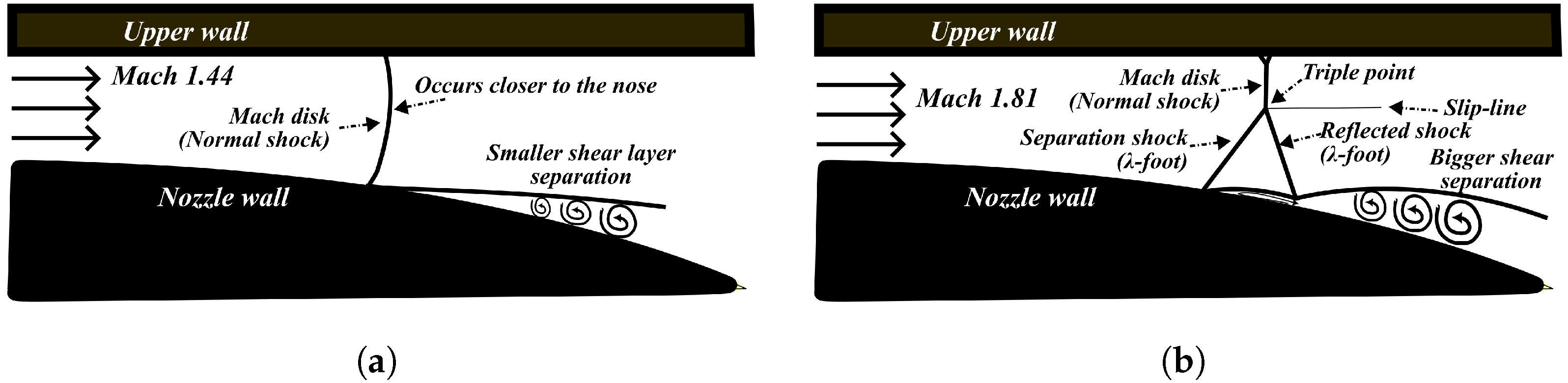

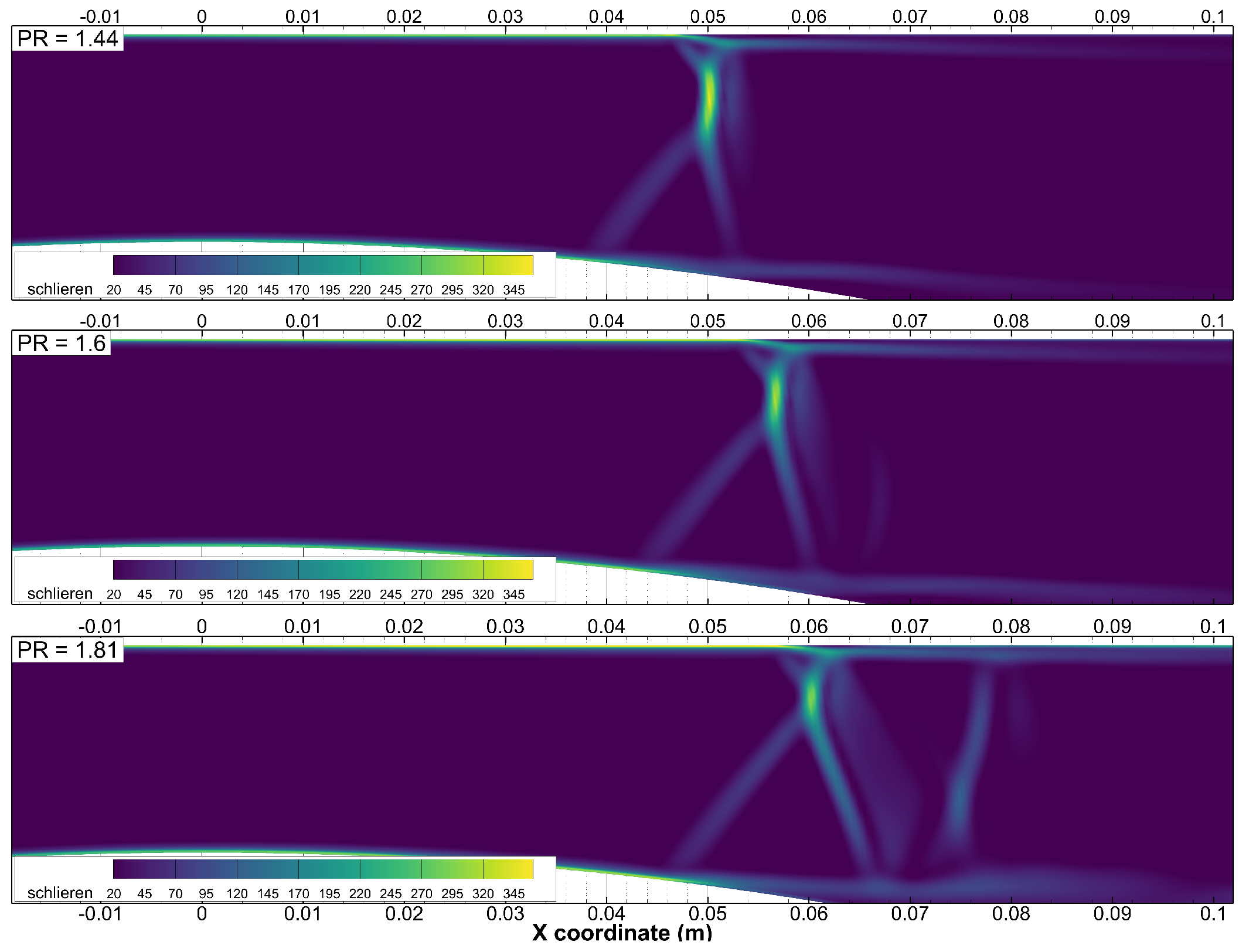

3.2. Schlieren Image-Based Flow Structure Analysis of Nozzle Flow for Different Pressure Ratios

In order to shed more light on the large-scale oscillations of shock waves, this section presents a preliminary analysis of the comparison of the flow structure corresponding to the three wind tunnel conditions. This is achieved by comparing the time-sequence Schlieren images at four successive time samples ( to , where is the sampling rate of the images). The subfigures in Figure 8 illustrate the presence of varying SBLI dynamics leading to discrete Mach disk lengths, the -foot structure, and the accompanying flow separation region and coherent vortical structures linked thereto, which is on par with the physics elaborated in [46,59,60]. It was also noted that this complex shock-wave structure presented streamwise oscillations within the divergent section. The aim of this research was to carry out spectral characterization of these different events and enhance fundamental understanding related to these low-frequency shock-wave oscillations. As noted in the figures, shock-wave structures consist of an inviscid normal shock (also called the Mach disk) near the top surface (indicated as A in Figure 8b), a prominent -foot shock structure (indicated as B) comprising a leading separation shock (bright white line: C, Figure 8c) and a reflection wave (downstream dark line: D) linked with the lower region followed by shear-layer separation region (E). The two shock waves (C and D) merge with the Mach disk at the triple point (F). The varying intensities of these shock-wave structures lead to varying flow separation dynamics downstream.

Figure 8.

Time-sequence Schlieren images for different cases (a,d,g,j) PR; (b,e,h,k) PR; (c,f,i,l) PR. Dotted red ellipses are regions of interest.

The time-sequence images for PR1.44, that is, Figure 8a,d,g,j, indicate that the lower ratio leads to SBLIs being dominated by the inviscid Mach disk structure occurring closer to the throat. This led to increased and earlier pressure increment beyond the shock wave for PR1.44, as indicated earlier in Figure 7a. Owing to the thinner boundary layer at this portion, as well as the weaker shock wave, the effect pertaining to the shock-wave impinging on the boundary layer is minimal, and hence the -foot structure is visibly small-scale. It was also contemplated from the time-sequence images that this normal shock wave was more stable. Thus, the weaker shock wave at this PR leads to a more stable shock wave [12]. Due to the presence of this normal shock wave, downstream flow is dominated by subsonic flow aerodynamics and forms a fully separated shear-layer downstream. Due to the relatively lower velocity gradient between the shear layer and the post-shock core flow, density variations leading to Kelvin–Helmhotz (KH) instabilities are less intense, resulting in minimal density fluctuations downstream of the shock. The flow downstream is mainly dominated by non-linearities associated with shear-layer eddies. Notwithstanding these attributes, this case still presented streamwise oscillations of the shock-wave structure.

As PR increases to , this flow interaction becomes more complex, and the time-resolved images illustrate the presence of incipient separation [61], leading to the formation of FSS, wherein the flow downstream of the shock wave close to the surfaces lacks flow reattachment [15], and a prominent -foot structure originates. Due to the increased energy of higher PR flow, the shock wave originates at a later distance (Figure 8b) downstream of the throat, wherein the attached boundary layer is thicker. These observations are similar to the ones observed by Papamoschou [35]. Higher PR leads to increased momentum of the incoming flow, which results in a fuller profile, leading to a more downstream position of the SBLIs [7]. Furthermore, higher PR leads to the development of a stronger shock wave, resulting in an increased adverse pressure gradient that interacts with the underlying boundary layer to create a separation bubble upstream of the Mach disk that ultimately results in the formation of an oblique separation shock. The flow downstream of this oblique wave interacts with the shear layer. Due to the heightened velocity differences between these two regions, KH instability fluctuations are more intense in this case (Figure 8e: F). Figure 8e further indicates the origin of an additional stronger shock wave from the triple point, downstream of the separation shock, called the reflection shock (G). Its intensity increases as flow develops with time (compare Figure 8e: G and Figure 8h: H). This leads to increased KH interactions at the foot of the -foot structure. Moreover, Figure 8k shows the presence of a white line originating from the triple point, called the slip line (I), which is a result of slow-moving flow downstream of the normal shock interacting with the faster flow downstream of the reflection shock leading to increased flow intermixing, and hence the intense density variations appear as line originating at the triple point. Distance between the first separation shock and the trailing reflection shock is called the separation length scale [7] and is notated as . Notably, the shear-layer separation is exacerbated for this case, leading to increased density fluctuations downstream. Moreover, flapping of the shear layer was more appreciable at this PR.

As PR increased to PR1.81, -shock-wave intensity increased and occurred at a later distance from the throat. Due to the overall shock-wave intensity increment, flow separation downstream of the Mach disk is exacerbated, leading to increased interactions and the -foot structure becoming more intense. In fact, Figure 8c,f,i,l illustrate the presence of a small -structure even at the upper portion of the whole structure (See J in Figure 8i). Fluctuations pertaining to were observed to be more significant at this PR, which would indicate increased oscillations within the separation region, as well as global instability associated with vortex shedding. This subsequently leads to a more intense reflection shock for this case. Thus, increased PR led to increased interactions between the different regions related to SBLIs, which would indicate the increased influence of high-frequency KH instabilities associated with mixing between the core supersonic flow and shear layer, as well as the eddies associated with slip line formation (See K in Figure 8i,l). The increased flow interactions are corroborated by the presence of increased density fluctuations downstream of the separation shock for PR1.81. The increased influence of turbulent eddies on the overall flow pattern would indicate the presence of increased impact of high-frequency turbulent eddies on the frequency spectrum, which will be further emphasized using spectral analysis in a later section. Similarly to PR1.44, this case also exhibited the presence of low-frequency large-scale oscillations of the shock-wave structure with respect to the separation-shock foot. In a nutshell, the higher the PR, the more prominent the impact of separation and reflection shocks will be, leading to a more prominent shock-wave structure. An illustration depicting the evolution of flow structure as PR increases within the studied nozzle is provided in the schematics presented in Figure 9. The lower PR (Figure 9a) flow was dominated by normal shock component occurring at an earlier position within the nozzle, whereas the higher PR flow is dominated by a more complex -foot shock structure emanating at a latter distance, leading to increased flow inter-mixing, and hence a more complex downstream flow structure, including reflected shocks, slip lines, increased shear-layer separation and KH vortices.

Figure 9.

Schematic to illustrate the evolution of shock-wave structure as PR increases; (a) Flow structure at lower PR; (b) Flow structure at higher PR.

Thus, we can say that increasing the PR led to increased interactions between the different components, leading to a significant impact on the overall structure of these SBLIs. Moreover, these heightened complex interactions between the shock wave and underlying boundary layer led to the formation of shock trains (L in Figure 8l), a bigger separation region (M in Figure 8l), increased flapping of the shear layer (N), as well as increased vortices downstream of the shock wave, as indicated by the O region in Figure 8l. Large-scale low-frequency oscillations associated with nozzle flows were established for all the cases. In order to provide critical insights into these quasi-periodic oscillations and reconcile the causes of this unsteadiness, a detailed spectral analysis was carried out, which is illustrated in the following sections.

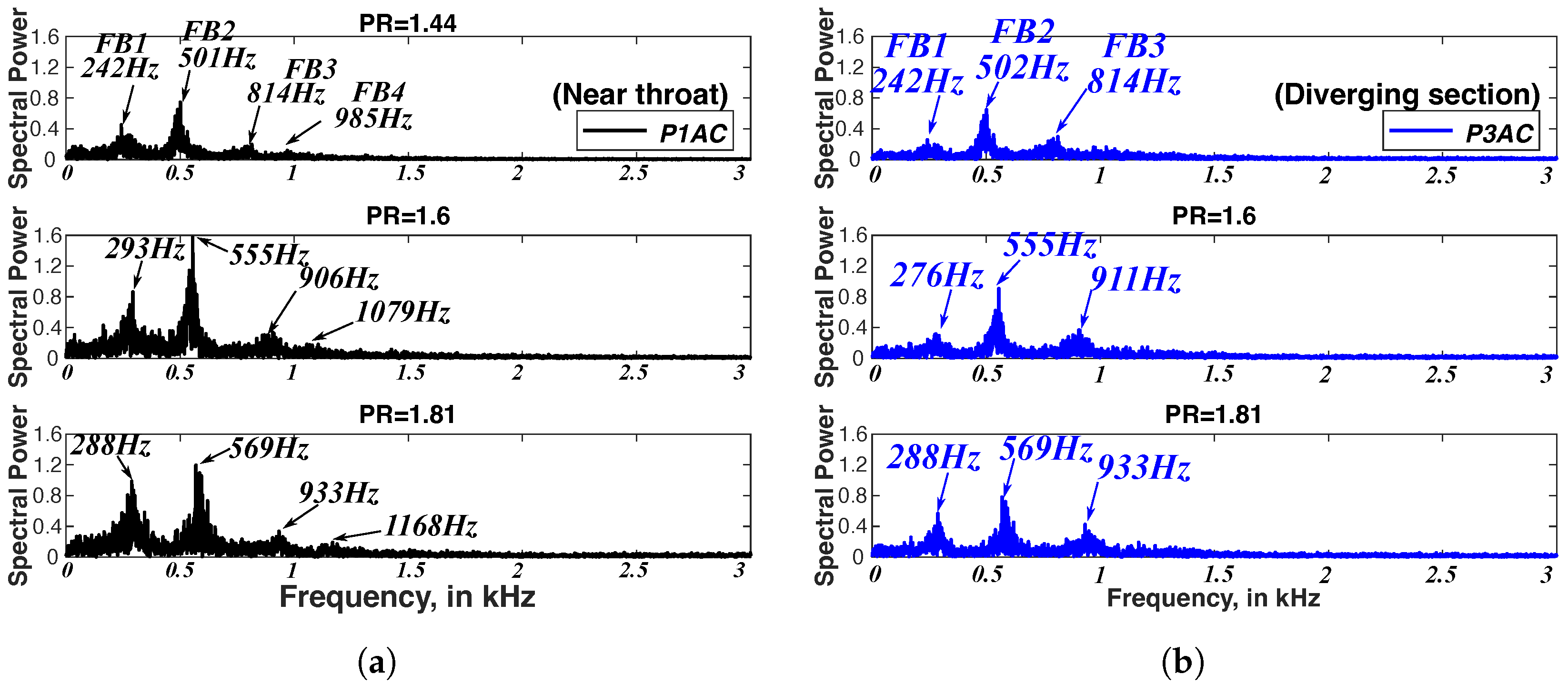

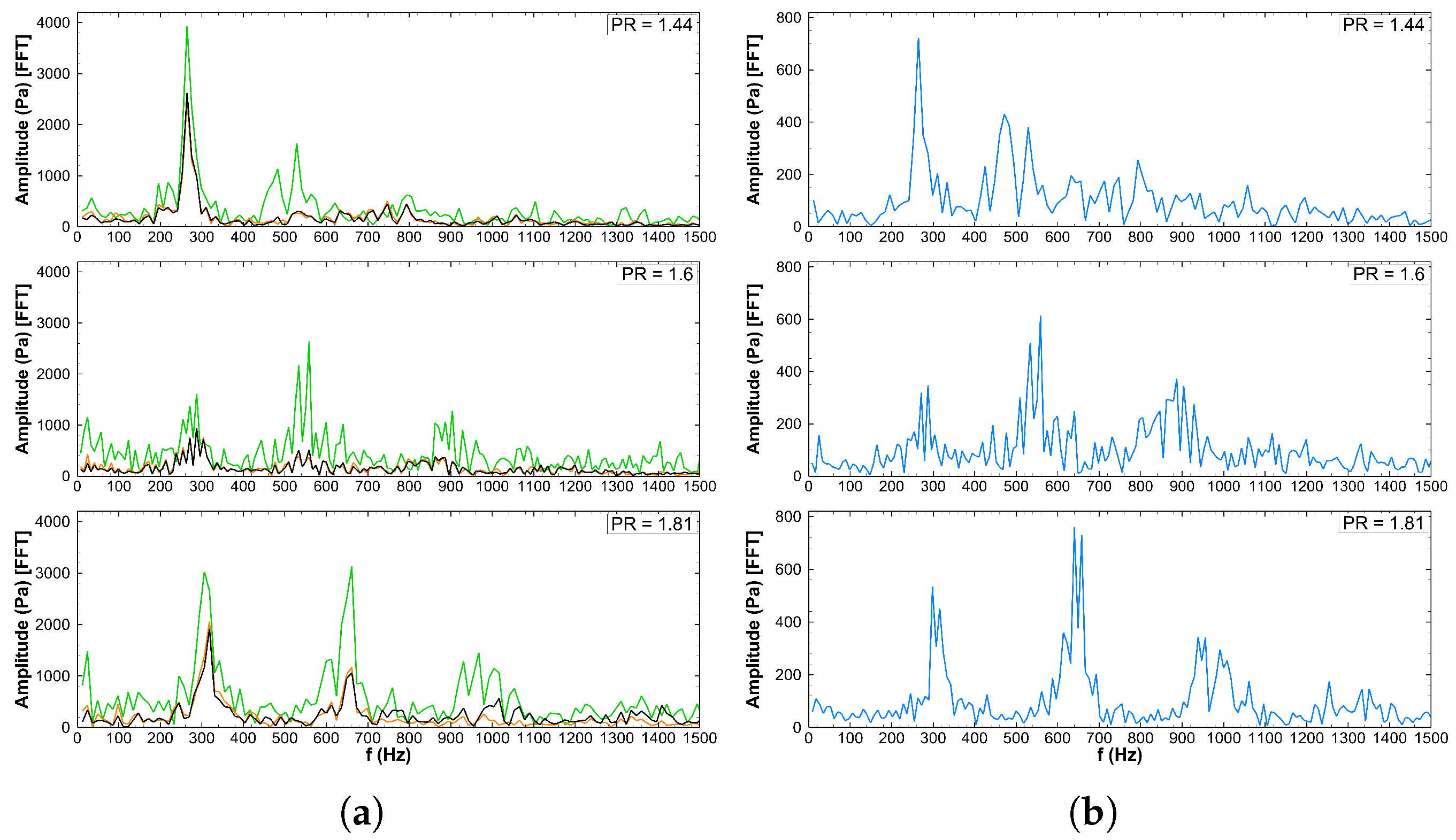

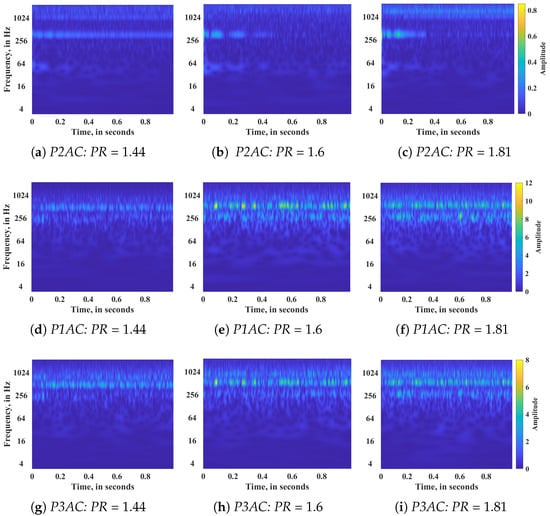

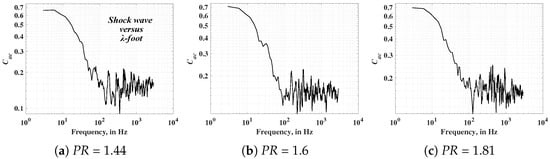

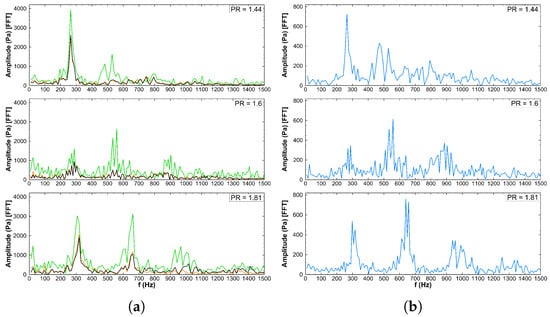

3.3. Spectral Analysis of Pressure Data Obtained Using High-Frequency Transducers

Critical understanding regarding the aforementioned unsteadiness was initiated by comparing the FFT plots of time-sequence pressure data obtained using the high-frequency transducers P1AC (Figure 10a) and P3AC (Figure 10b), with the former being closer to the throat, and the latter being further downstream of the throat (See Figure 3) and placed on the upper wall. An experimental study carried out by Bourgoing et al. [62] demonstrated the presence of similar frequency peaks across the upper and lower ends of an asymmetric wave. Moreover, it is well established that reflected shock waves generate an upward deflection of flow [6], which is the reason why shear layer and prominent -foot reflections on the lower surface will be measured by transducers placed on the opposite wall. Thus, deductions drawn from the spectral analysis of transducers placed on the upper wall will also be qualitatively similar to the lower surface flow. Through a succinct analysis of the underlying frequency components, FFT analysis leads to enhanced understanding related to oscillations that contribute significantly to the global energy spectra of unsteadiness interactions contained within the time-domain signals of pressure transducer data. Considering the number of samples being 6000 and a sampling rate () of 6000 per second, the resolution in the frequency domain was 1 Hz. As per the Nyquist criterion, the maximum frequency discernible through this sampling was , that is, 3 kHz. Considering the placement of transducers on the top-surface, the spectral plots obtained using the transducer data would be dependent on the fluctuations due to Mach disk gradient, shock-wave location, as well as reflected fluctuation from the lower surface interactions.

Figure 10.

Spectral power distribution for pressure data fluctuations at different pressure ratios at different locations (a) P1AC (b) P3AC.

For the three PR cases, Figure 10a shows that P1AC detects the presence of three distinct peaks associated with pressure oscillations and a fourth small pulsating peak between 985 and 1068 Hz. A 2020 experiment on the compression corner by Shanguang et al. demonstrated the presence of similar three peaks residing between 100 to 1000 Hz, which provides further context to the validity of these results. The first frequency peak lies between 242 and 293 Hz, the second between 501 and 569 Hz, and the third between 814 and 933 Hz. These ranges will be termed as frequency band −1 (FB1), frequency band −2 (FB2), and frequency band −3 (FB3), respectively. The most dominant frequency, which resides within the range of 500–600 Hz, is in concordance with the 0.4 kHz–2 kHz range, as estimated by Brusniak & Dolling, 1994 [63]. It is also evident that the corresponding frequency and power of these peaks increase significantly between PR1.44 and PR1.6. However, as the PR changes from 1.6 to 1.81, this frequency increment is markedly lower. In fact, the peak frequency value for FB1 reduces from PR1.6 to PR1.81. It was noted earlier that the flow associated with PR1.44 is dominated by the inviscid normal shock-wave structure, whereas the latter two were associated with increased separation shock impact leading to increased impact of the oblique shocks on the overall flow structure. Normal shock leads to exacerbated adverse pressure gradient conditions, amounting to a heightened scale of the associated vortices, which amounts to lower-frequency oscillations. The flow corresponding to -foot interactions is associated with smaller-scale oscillations, leading to higher-frequency turbulence flow eddies. Owing to the diverse nature of the underlying flow physics, frequency differences between the former two cases are significantly steep. On the other hand, the flow structure related to PR1.6 and PR1.81 is similar, leading to mitigated differences between their respective peak frequency values. The subtle increment in frequency value between PR1.6 and PR1.81 for FB2 and FB3 is attributed to increased bulk momentum, leading to increased incoming turbulence, and hence a higher frequency [26]. Peaks pertaining to FB4 are presented only for PIAC. This would indicate the presence of a localized driving mechanism related to FB4 oscillations. The close proximity of shock waves to P1AC could lead to acoustic reflection, small-scale vortices, or small-scale flapping of the shear layer, which are associated with high-frequency oscillations. Considering the dependence of these phenomena on the incoming flow momentum, higher PR amounts to a significantly increased frequency value of peaks associated with FB4.

It is also noticeable that the overall magnitude of FB2, FB3, and FB4 increases between PR1.44 and PR1.6, whereas it reduces from PR1.6 to PR1.81. This could be associated with the relative placement of the transducer with respect to the shock-wave interaction. As mentioned earlier, the complex interaction region moves downstream as PR increases. The transition from PR1.4 to PR1.6 leads to a shock wave moving closer to the P1AC, leading to increased magnitudes of the detected FB2, FB3, and FB4 peak oscillations. On the other hand, between PR1.6 and PR1.81, the interaction regions move further downstream. The reduced magnitude indicates that the transducer moves upstream at some of the time-stamps, leading to a reduction of the averaged magnitude of these pulsations. The magnitude related to FB1 increases between PR1.44 and PR1.6, whereas it remains similar in magnitude between PR1.6 and PR1.81. This indicates the presence of a low-frequency large-scale phenomenon within the flow, for which the amplitude varies significantly between the first two, whereas it remains the same between the last two cases. This indicates that this modulation is related to large-scale instabilities within the separated shear layer that lead to flapping of the shear layers [64], which could be related to the shedding of vortices and separation-layer breathing. At higher PR, this global instability increases, leading to an elevated scale of separation-layer oscillations, and hence the lowered-frequency value of the associated FB1 peak. Thus, transducer data placed closer to the throat, wherein the effect of shock-wave unsteadiness would be the maximum, illustrates the presence of three primary peaks, which will be further corroborated using shock-wave position data FFT. The plots also demonstrate that as the effect of -foot increases, small-scale oscillations associated with broadband frequency pulsations become more prominent, and are showcased as increased high-frequency spectrum magnitudes. Therefore, higher PR values imply a greater impact of flow separation, which results in a broader and more attenuated oscillation spectrum.

Spectral plots pertaining to port P3AC in Figure 10b display unique characteristics pertaining to pressure wave oscillations. The pressure waves recorded at this location will be influenced by large-scale streamwise oscillations of shock waves, small-scale high-frequency turbulent oscillations related to flow separation, shear layer, as well as acoustic disturbances. Frequencies pertaining to the first three peaks occur at the same frequency value compared to those existing at P1AC. This is indicative of increased correlation of the associated oscillations across the two locations. It is also noteworthy that the magnitude of FB1 and FB2 peaks is lower at P3AC compared to P1AC. Thus, downstream of the shock, increased mixing due to separation-induced SBLIs leads to attenuated power of these two modes of oscillations, which is indicative of their association with the overall interaction dynamics. It is also noteworthy that the amplitude of FB1 increases as PR increases, which provides further credence to this modulation being associated with the separation-induced vortex shedding phenomena (to be clarified using wavelet analysis in a later section). The amplitude of FB3 is higher at this location. Thus, the effect of high-frequency oscillations is higher at this location, which would indicate the dependence of these oscillations on the shear-layer oscillations, including flapping, which becomes more intense and thicker as the flow moves downstream of the interaction region [64]. Thus, the impact of high-frequency overtones attributed to mixing-layer flow eddies present at this location increases, leading to increased frequency and amplitude scales. These observations emphasize the relation of low-frequency peaks with large-scale oscillations of the interactions, whereas the higher-frequency peaks were related to the turbulence characteristics linked with incoming turbulence or the shear-layer separation dynamics. Notably, these revelations are similar to those observed by Pirozolli et al. in [65], wherein similar assertions were drawn for flow across an impinging shock configuration.

The FFT plots demonstrate the presence of multiple spectral peaks ranging between 240 to 990 Hz, with a lower power value within the diverging section. The lower two peaks are indicated to be related to the overall shock structure interaction and their oscillations, whereas the third and fourth peaks are indicative of their relation with the shear-layer instabilities. The plots also demonstrate the presence of increased correlation between the pressure data at the throat and diverging section, which is indicative of dependence of the downstream fluctuations on the throat location. To gain further insights into these unsteadiness events, detailed spectral analysis of shock-wave position data, as well as interaction regions, has been carried out in the succeeding sections.

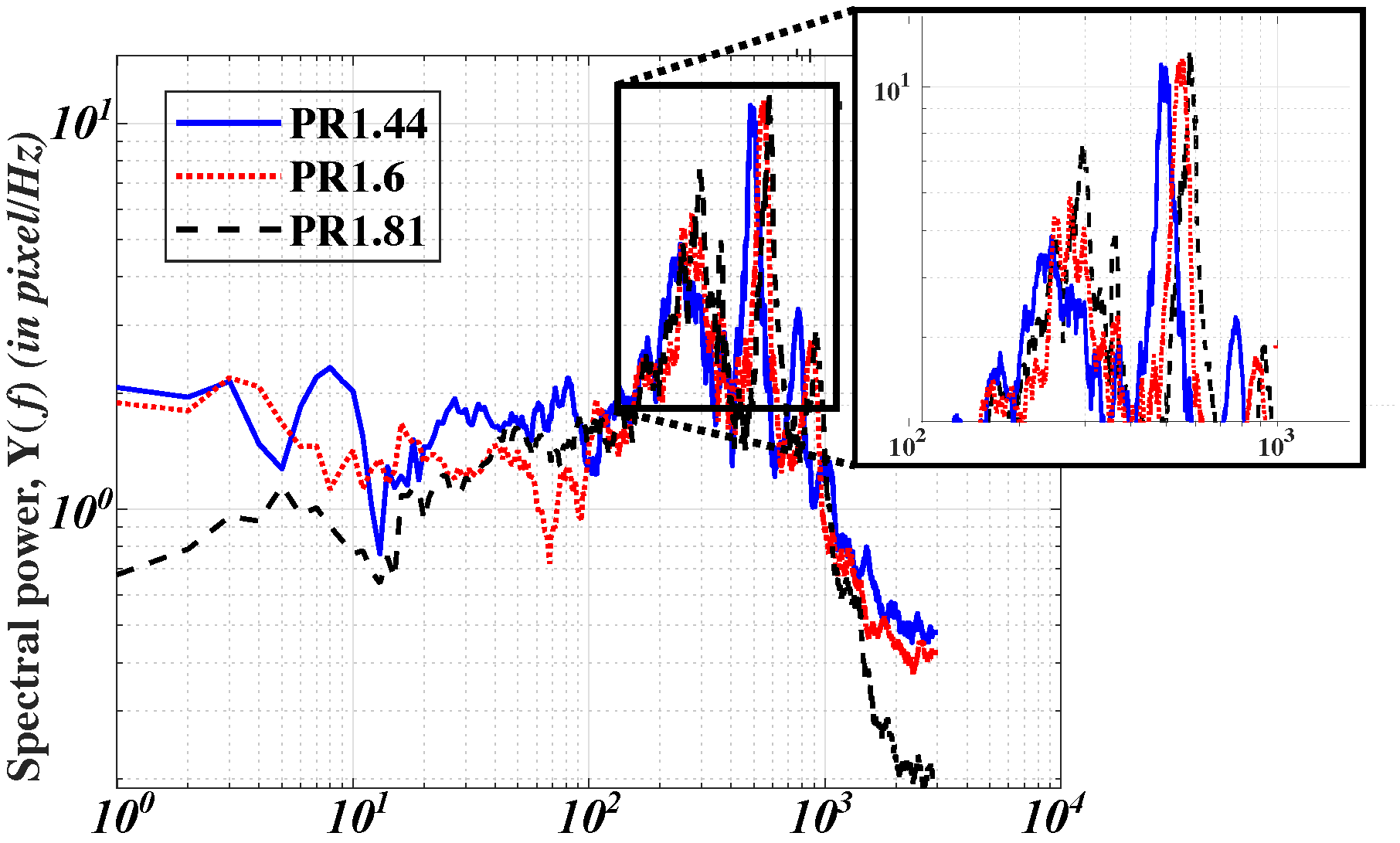

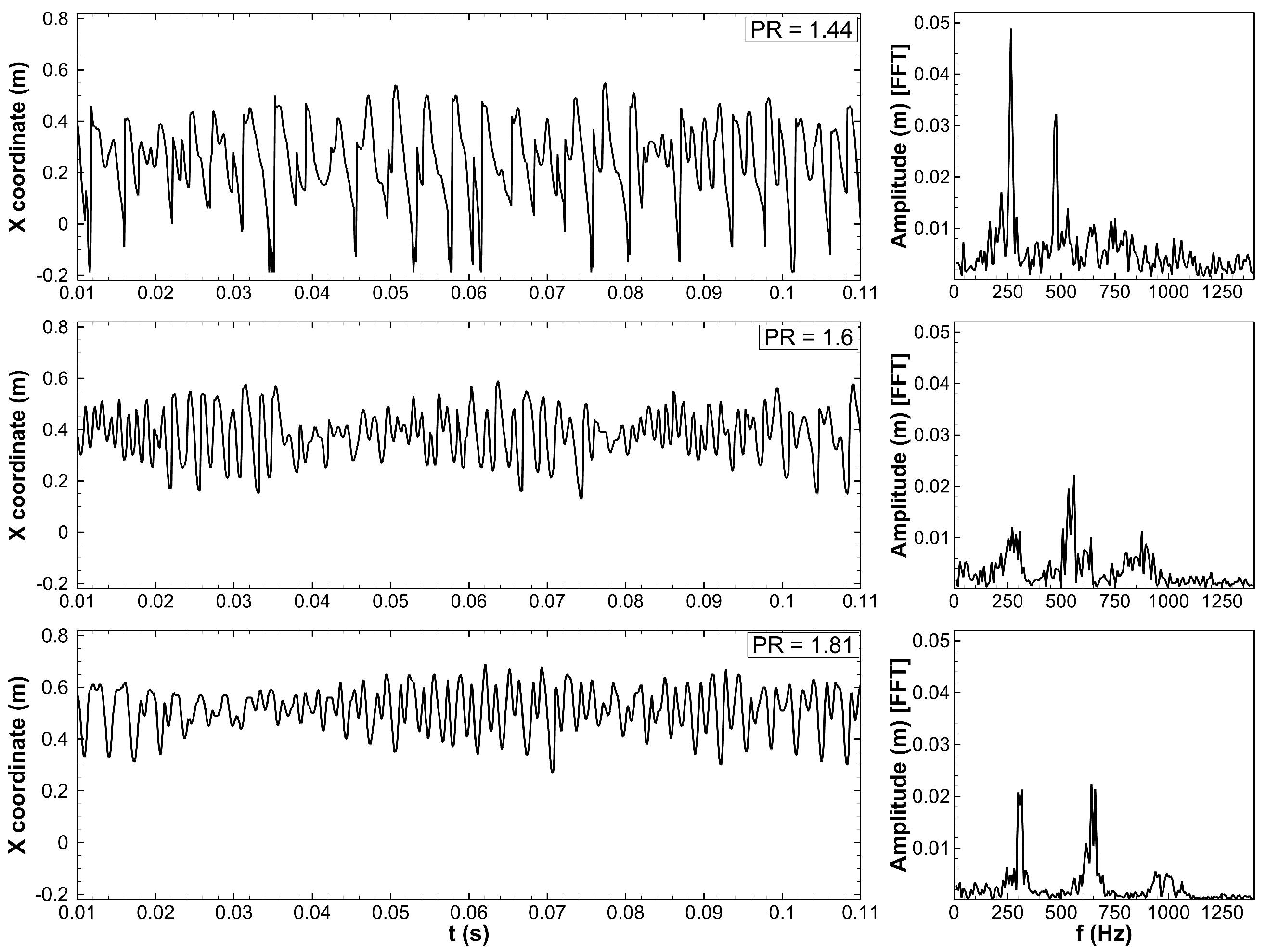

3.4. Spectral and Statistical Analysis of Shock-Wave Position Data Derived Using Lagrangian Approach

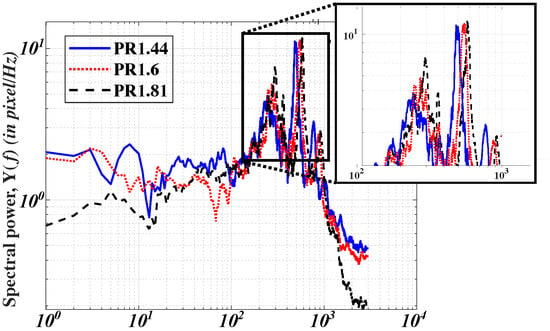

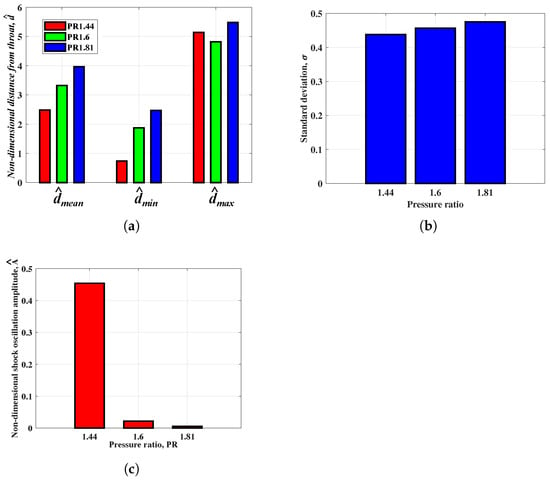

Spectrum plots obtained using pressure data are constrained by the fact that it does not represent the complete flow-field, leading only to an external overview of the underlying unsteadiness [3]. In order to increase the validity of these plots and also increase understanding related to shock-wave dynamics, Figure 11 plots the spectral power density () of the frequency spectrum derived by carrying out an FFT of the non-dimensionalized shock-wave position with respect to the mean position of the shock wave. Data pertaining to the shock-wave position was obtained using the image processing technique described earlier in Section 2.4. The acquired FFT plot was further smoothed using the variable moving average technique described earlier in Section 2.5. However, moving average parameters were adjusted to improve clarity of the plots pertaining to this data and are described in Table 6.

Figure 11.

Spectral power density for the quasi-periodic shock-wave position about the mean shock-wave position obtained using Fast Fourier Transform.

Table 6.

Smoothening operation for PSD obtained for time-resolved shock-wave position data.

It can be seen that most of the spectral power pertaining to oscillations associated with shock-wave position data resides within 173 Hz to 1000 Hz, with powers reducing above and below these frequencies. Analogous to the FFT plot pertaining to pressure fluctuations described above, these plots also display the presence of three prominent frequency peaks for the three cases, with frequency values lying within the same range as that mentioned earlier. The first band (FB1) lies within 242 Hz to 297 Hz, the second (FB2) within 485–580 Hz, and the third one (FB3) within 767–920 Hz (See Table 7). Moreover, similar to pressure FFT plots, the frequency value of these peaks is commensurate with the PR value, with a higher PR leading to a higher-frequency value. This increment is higher at ≈14% within PR1.44 to PR1.6, which reduces to an increment of 6.1% between PR1.6 and PR1.81. It can be ascertained that the frequency range estimated by the pressure data, as well as shock-wave position data, is very close to each other, which provides validity to the presence of these three primary oscillations dominating the entire flow field. Furthermore, this provides credibility to the accuracy of the employed Schlieren images to capture the overall flow unsteadiness.

Table 7.

Peak frequencies pertaining to dominant oscillations for the three PR cases.

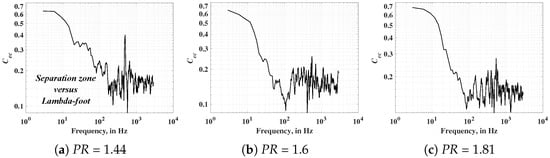

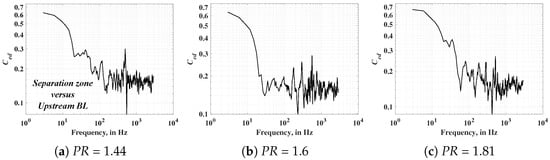

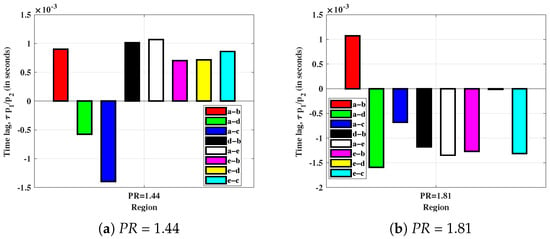

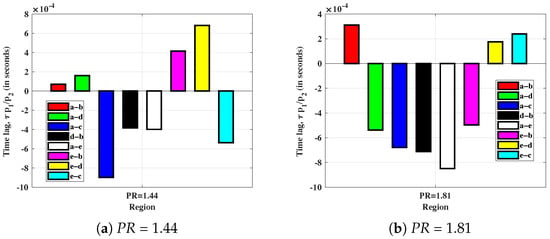

Given the increased impact of flow-field parameters, including upstream and downstream conditions, on shock-wave position, spectral plots pertaining to shock-wave position data indicate the presence of many more low-amplitude frequency peaks, which were not visible within the pressure data FFT. The FFT plot pertaining to PR1.44 illustrates the presence of an additional peak at 8 Hz and several small peaks below 100 Hz, which are not visible in the other two cases. The predominant normal shock interaction leading to mitigated flow separation for PR 1.44 increases the influence of upstream flow turbulence [7] on the shock-wave position. Considering the emphasized role of upstream high-frequency flow in driving low-frequency oscillations [24], the detected low-frequency peaks could be attributed to the upstream-boundary-layer unsteadiness that results in a subtle ‘breathing effect’, causing small shifts in the shock location that are too subtle to be detected by the transducers. This will be further corroborated using the statistical analysis of amplitude related to these oscillations in a later analysis, as well as coherence and spatial FFT analysis. Notably, the power of oscillations below the range of FB1 is significantly lower for higher PR cases, further indicating the increased impact of high-frequency turbulent eddies and high-frequency shear-layer unsteadiness on the overall shock-wave flow oscillations.