Abstract

Europe, including Poland, is undergoing an energy transition. The use of renewable energy sources (RES) in the national energy sector is increasing significantly, and previously unused areas are increasingly developed for photovoltaic power plants. A specific type of housing common in Eastern European countries opens an additional opportunity for photovoltaic installations without occupying usable ground area. This article aims to analyze the potential for utilizing balconies and loggias in large-panel buildings, which are characteristic of major cities in Poland. Approximately 30% of the population resides in such housing. This presents significant potential for direct use of renewable energy by apartment residents. The article also explores the legal framework for such installations, both as individual investments by apartment owners and as collective initiatives managed by building administrators. The authors analyzed the potential performance of photovoltaic installations under varying azimuths and tilt angles, considering solar irradiation potential. The analyses also encompassed different photovoltaic module technologies, covering a spectrum of photovoltaic technologies, from commonly used monocrystalline panels to advanced transparent BIPV (Building-Integrated Photovoltaics) solutions. Furthermore, the study quantified the energy potential of such installations and compared the results with existing photovoltaic capacities and electricity demand in Poland.

1. Introduction

The energy transition in cities presents substantial technical, administrative, and social challenges [1]. However, it is essential to achieve decarbonization by reducing energy demand and increasing the share of renewable energy sources. For most geographic regions, the easiest renewable energy solution to implement is the utilization of solar radiation [2]. Various tools are used to assess the potential for deploying active and passive solar installations in urban spaces, most commonly geographic information system (GIS)-based methods. Numerous studies in the literature address this topic. For example, the authors of [3] proposed a GIS-based approach combined with machine learning to estimate sun-exposed surfaces in urban areas and analyzed the accuracy of different machine learning methods for this application. Similarly, Ref. [4] presented a method combining deep learning with an integrated GIS approach for precise assessment of building façade solar energy potential at the city scale, with particular focus on shading from surrounding structures.

An alternative approach to evaluating solar gains was presented in [5], where a novel methodology using drone imagery was proposed to assess and estimate the solar potential of urban rooftops. According to the authors, this method provides higher accuracy due to the high-resolution images. The authors of [6] suggest that future solar cadastres should improve calculations of building solar potential, considering façades, inter-building reflections, and material properties.

Photovoltaic (PV) installations are the dominant form of urban renewable energy systems. In [7], a comprehensive review of the field, termed “urban photovoltaics”, was presented. Some studies address unconventional solar applications. For instance, Ref. [8] proposed the use of quantum dot solar cells (QDSC) for urban revitalization while complying with building regulations. These cells are flexible, available in a wide range of colors, and transparent, offering significant integration potential with existing buildings. The most common approach, PV installation on flat urban rooftops, is described in [9], where the authors evaluated the energy efficiency and financial viability of on-grid urban PV microfarms for Central and Eastern European countries.

Other solutions focus on building façades, such as shading devices or blinds. For example, Ref. [10] presented analyses of three office buildings integrating active solar systems—both PV and thermal—into façades. The analyses considered energy production, shading, solar exposure, and visual comfort for occupants, providing a holistic approach to environmental design. Shading canopies for high-rise urban buildings were also examined in [11] using GIS-based analysis. The development of BIPV façade systems from optical, thermal, and electrical perspectives was reviewed in [12], identifying research gaps, optimization strategies, and future directions. Shading from neighboring buildings must also be considered in urban PV design. The authors of [13] quantified the impact of shading on incident solar radiation and system losses, comparing it with inter-row shading in open-space PV installations. A more detailed, multi-level design approach was presented in [14], analyzing BIPV systems at the building, electrical system, module, and solar cell levels, and addressed both technical and social barriers to widespread adoption.

Fewer studies focus on multi-family residential buildings equipped with solar installations. According to [15], in Brazil, despite high potential, multi-family buildings play a secondary role in increasing solar installation deployment. The authors emphasize the need to highlight financial and business benefits for residents rather than repeatedly emphasizing environmental or climate concerns. Among existing approaches, Ref. [16] analyzed a double-skin façade integrated with a solar system for a multi-family building, assessing the depth of the façade cavity and differences between standard glazing, PV, and thermal installations. The study demonstrated potential benefits for thermal comfort, reducing heating and cooling needs. Similarly, Ref. [17] explored achieving net-zero energy consumption in multi-family buildings through PV alone, particularly on rooftops. Another study, Ref. [18], proposed a model for investment and operational decision-making within renewable energy communities, enabling multiple participants to invest in energy generation and storage systems. The results indicate significant potential for development, enabled by the possibility of adding new community members, which is particularly significant for multi-family housing.

The development of photovoltaics in cities is progressing very dynamically—not only in Poland but throughout Europe. Currently, the potential of rooftop surfaces on multi-family residential buildings is being assessed and quantified [19]. One example is the study of photovoltaic potential in the city of Barcelona, Spain, where the theoretical energy potential is estimated at 64.84 million kWh per year [20]. In countries such as France, Germany, and Italy, the potential installed capacity for rooftop systems on multi-family buildings exceeds 100 GW in each of these countries [21]. Data from 2023 show that in the European Union (EU-27), the total capacity of rooftop PV installations reached approximately 137 GW, illustrating the vast scale of rooftop utilization in the residential sector [22]. Therefore, the article should be considered not only on a micro scale—for a specific neighborhood within a city—but also in terms of its significant impact on a macro scale, affecting the overall power system. This topic aligns with the current strategies of the European Union, particularly with the European Green Deal—a strategy aimed at achieving climate neutrality by 2050. It encompasses a wide range of actions, from environmental protection and the circular economy to energy transformation. One of the key pillars of this transformation is the development of renewable energy sources, with a particular focus on photovoltaics.

In summary, the literature review indicates that multi-family residential buildings will be an important focus for urban PV development in the coming years. The objective of this study is to analyze the potential of balcony photovoltaics, particularly for large-panel buildings (known in Poland as ‘wielka płyta’), which are common in residential developments (Figure 1). Subsequent sections will detail the characteristics of large-panel housing, types of balconies, potential PV solutions, projected energy yields, and legal and social aspects of installations managed either by individual apartment owners or by housing cooperatives and associations.

Figure 1.

Selected Large-Panel Residential Estates in Wrocław (based on Google Earth Pro 7.3).

2. Large-Panel Buildings—Characteristics

In Poland and many other Central and Eastern European countries, large-panel buildings have been constructed since the 1950s [23]. A significant housing shortage forced authorities to adopt a fast and inexpensive construction method, resulting in the development of extensive housing estates primarily for the working class. The peak of large-panel technology occurred during the 1970s and 1980s. By the 1990s, this construction method faced strong criticism due to low quality and repetitive, monotonous architecture [24]. The fall of communism also contributed to changes in the construction sector, leading to the closure of factories producing components for large-panel buildings. Although a small number of such buildings continued to be constructed into the early 21st century [25].

The estimated lifespan of large-panel blocks at the time of construction was 50–70 years. However, modernization efforts have significantly extended their service life, potentially up to 100–120 years, ensuring that they will remain a visible part of the landscape in Poland and other Eastern European countries for decades to come [26].

According to analyses by the Central Statistical Office of Poland in 2023, there are approximately 60,000 large-panel blocks in Poland, comprising 4 million apartments housing around 10–13 million people. With a total population of 36.5 million, approximately 30% of the population lives in this type of housing [27].

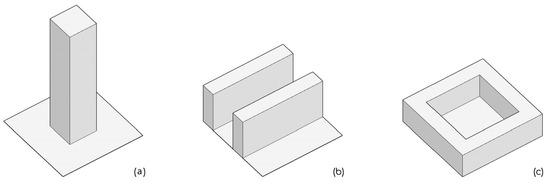

On Figure 2 are the three main urban development layouts; pavilion, street, and patio. The selection of the three study areas was based on these fundamental urban development layouts [28], thereby ensuring a holistic coverage of the possible geometries typically encountered in urban contexts.

Figure 2.

Predominant Shapes of Large-Panel Buildings as the three main urban development lay-outs—(a) pavilion, (b) street, and (c) patio.

It is worth noting that the vast majority of large-panel blocks are currently undergoing modernization processes, primarily thermal retrofitting. To date, only about 30% of the blocks have been modernized, indicating that a significant amount of work remains [29]. This also presents an opportunity not only for building insulation or upgrading plumbing systems but also for installing renewable energy sources, including photovoltaic systems. This trend has been observed in Poland since around 2017, with PV systems in large-panel buildings mainly installed on rooftops, while balcony or loggia rail surfaces have rarely been utilized [30].

Large-panel construction is notable not only for its large scale but also for the inclusion of balconies and loggias, which were intended to enhance the standard of living. During the period of large-panel construction, population movements were significant, as people left villages for work in larger cities [31]. Balconies were designed to serve as a small private outdoor space, allowing residents to spend time outside without leaving their apartments. They became ideal for relaxation, drinking coffee, reading, or growing plants. Additionally, balconies provided practical benefits such as increased natural light and ventilation, as larger windows improved interior illumination and offered a sense of connection with nature and the surrounding environment. They were also useful for practical purposes, such as drying clothes or storing seasonal items (e.g., bicycles, potatoes, onions) [32].

People migrating from villages to cities wanted at least a semblance of a garden or open space, which is why nearly every apartment in large-panel blocks was equipped with a balcony. The proportion of such apartments can be verified through construction plans and market data on secondary housing sales in large-panel buildings [33]. Analyses show that three out of four apartments in these buildings have a balcony, representing approximately 75% of all units in large-panel housing. This marked a significant change compared to earlier multi-family housing, such as tenement houses, which rarely included balconies (about 30%). Interestingly, the trend of including balconies in multi-family housing has now become a standard, with over 80% of new buildings equipped with them. Data analysis for the largest cities in Poland is presented in Table 1 [34].

Table 1.

Percentage of large-panel apartments equipped with balconies in major Polish cities [33,34].

It is important to distinguish between two basic construction approaches: equipping buildings with either balconies or loggias (Figure 3). A balcony is characterized by a structure projecting beyond the building’s outline. It is attached to the façade and supported by brackets or reinforced concrete slabs. As a result, it is open on three sides and usually enclosed only by a railing. The drawbacks of this solution include higher construction costs and greater exposure to weather conditions during use (e.g., wind, rain, snow) [35].

Figure 3.

An example of the basic geometries of balcony (left) and the loggia (right).

The second variant is the loggia, also known as a “recessed balcony”. A loggia is located within the building structure and does not extend beyond the façade. It is enclosed on three sides, with side walls and an overhead slab, and open only on one side (typically secured with a railing). This design is more functional, easier to enclose, and provides protection against rain, wind, and sunlight. Additionally, due to its recessed placement within the building structure, it offers a greater sense of privacy than a balcony [36].

Due to the predominant use of prefabricated elements in the construction of large-panel blocks, many buildings are highly repetitive [37]. This also applies to the dimensions of balconies and loggias. Such standardization was intended to facilitate the design and assembly of entire housing estates [38]. Examples of the most popular systems in Poland include W-70, OWT-67, and WUF-T, which typically feature rectangular balconies measuring 1.2 × 3 m. In blocks with—larger apartments, long balconies serving two rooms were often used, with dimensions of 1.2 × 5 m. Examples of such designs can be found in Warsaw’s Ursynów district and Gdańsk’s Zaspa district [39].

In general, balcony dimensions most commonly range from 1.0 to 1.5 m in depth (distance from the wall) and 2.5 to 3.5 m in length (along the façade) in typical two-room apartments. Some designs included extended balconies spanning two rooms, measuring 5–6 m, known as “through balconies”. The usable floor area of balconies typically ranges from 3–6 m2, less frequently up to 8–9 m2 in larger apartments [39].

The original railing height in PRL-era (Polish People’s Republic) projects was 90–100 cm, whereas current regulations require a minimum of 110 cm, which has been a key driver for balcony and loggia modernization. In the case of loggias, for example, in the Wk-70 and OWT-67 systems, typical dimensions were 1.4–1.6 m in depth and 3–4 m in length. The WUF-T system often included longer loggias, such as 1.5 × 4.5 m. Length (along the façade) depended on the apartment layout: in smaller units, it was usually 2.8–3.2 m, while in larger units it could extend across two rooms, reaching 4–5 m. Standard usable floor area for loggias was 4–7 m2, although some buildings feature loggias as large as 8–9 m2 (e.g., Ursynów in Warsaw or LSM in Lublin, with large loggias spanning two rooms) [39].

3. Solutions Applied in Balcony Photovoltaics

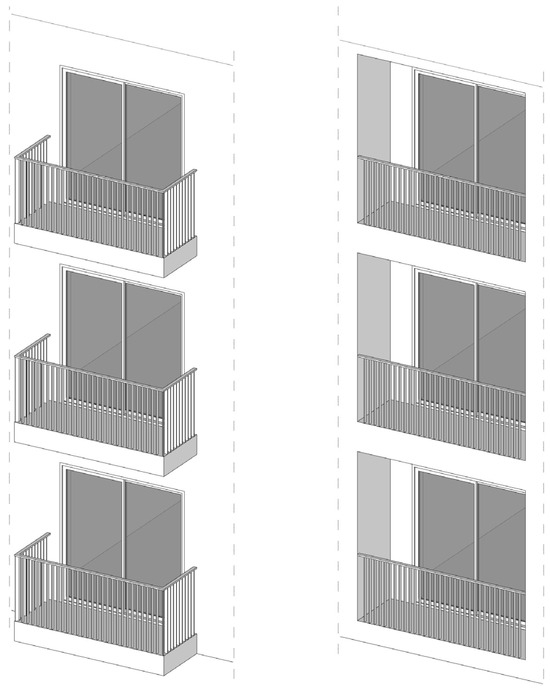

The use of balconies (primarily balcony railings) enables the implementation of solutions that differ in several aspects, including efficiency, cost, aesthetics, and functionality. Figure 4 presents a set of examples of balconies in large-panel buildings in Wrocław.

Figure 4.

Compilation of balconies in prefabricated large-panel buildings in Wrocław, Poland.

In the following section, the most important parameters concerning selected forms of mounting such PV installations will be presented.

3.1. Conventional Silicon Modules Mounted on the Balcony Railing

A commonly used solution is the installation of photovoltaic modules on supporting structures dedicated to balcony railings. This solution allows the use of an existing railing without the need to invest in a new railing integrated with PV modules. The entry threshold in this case is lower than in more advanced solutions, which translates into its popularity among a wide group of investors.

An advantage of this solution is the possibility of using various generations of PV cells. The most common are modules equipped with monocrystalline silicon cells—either traditional ones or those dedicated to balcony applications, characterized by low weight. In the case of lightweight modules, the mounting method is simplified. Instead of metal mounting structures, ordinary cable ties can be used, which further reduces investment costs. An additional advantage of this form of installation is the ability to detach the modules from the railing at any time, e.g., for system modernization on the balcony or relocating the installation. In the case of plug-in systems (plugged directly into a socket), it is also possible to move the entire installation, which proves useful when changing rental apartments or during holidays, enabling the use of electricity anywhere with access to sunlight. This is also a strong argument when applying to the property manager for permission to install a balcony PV system, as it avoids permanent interference with the building’s structure.

Choosing an appropriate (specialized) mounting structure allows the use of PV modules larger than the outline defined by the railing edges. Thanks to this additional active surface, higher system power can be achieved. This is a significant aspect, as balcony installations, due to their limited surface area, are characterized by relatively low capacities—usually a few hundred watts. Suitable mounting solutions may also influence the tilt angle of PV modules relative to the ground, which translates into higher efficiency (to a degree dependent on the geographical latitude where the installation is located). Both the installation of modules larger than the railing’s surface and the modification of their tilt angle are not possible in the case of railings integrated with PV modules, as their power output depends strictly on the shape and dimensions of the railing itself.

Given the limited surface area of balcony railings, it becomes crucial to use solutions with the highest possible efficiency in converting solar radiation into electricity. The application of traditional PV modules based on silicon cells ensures high durability and efficiency. They belong to the most proven and advanced photovoltaic technologies, featuring the latest and most effective solutions in both PV cell and module design. The efficiency of currently available solutions in this segment typically ranges from 20–24%. Adding to this their high reliability (confirmed by years of testing), long product warranties, and wide market availability, it is difficult to find a better alternative for PV installations mounted on balcony railings.

3.2. Silicon Modules (Monofacial and Bifacial) Integrated with the Railing (BIPV)

PV modules that simultaneously function as balcony railings represent a modern direction in BIPV (Building Integrated Photovoltaics) technology. In addition to generating electricity, they also serve as structural elements and enhance aesthetics. Despite limitations related to available mounting methods (compared to modules attached to existing railings), they constitute an attractive solution for many architects and designers.

Modules with bifacial silicon cells are often used because they enable the conversion of solar radiation reaching both their front and rear surfaces. Radiation reflected from surfaces inside the balcony increases the energy yield and allows for higher power output without enlarging the railing’s area. Depending on the PV cells used and operating conditions, it is theoretically possible to achieve energy yields higher by several to a dozen percent compared to monofacial modules. In practice, this depends on the installation’s geographical location, tilt angle, reflection coefficient (albedo), and the distance of building partitions forming the balcony interior.

Using bifacial modules on balconies can realistically improve efficiency by a few percent. However, it is not an optimal solution when mounting PV modules on existing railings due to uneven shading of the rear side by the railing itself. Even integrated bifacial systems can suffer reduced efficiency if shaded by furniture, plants, or bicycles often placed on balconies. Close proximity to the railing can also prevent uniform access of reflected radiation to all bifacial cells. Another challenge lies in the varied structure of balcony interiors (walls, windows, doors) [40]. Optimal conditions are achieved when interior surfaces are uniform and have high albedo, which can be improved, for example, by using suitable paints.

Privacy concerns may also arise, since traditional balcony covers negatively affect system performance. This solution is mainly found in new buildings and, occasionally, in renovated ones. In such projects, railings are designed from the start to integrate PV cells, eliminating additional supporting structures and creating a visually consistent architectural effect for the entire building.

3.3. Transparent/Semi-Transparent Modules

Currently, in the field of PV cells used in balcony installations, a wide variety of solutions are encountered, drawing on nearly all known generations of photovoltaic technology. Silicon cells remain the most popular, but despite their many advantages, they are not always the core of such installations. This is mainly due to aesthetic and architectural reasons. For instance, a designer’s vision may require balconies to feature a uniform, more or less transparent material. Transparent PV cells fit this purpose well.

On the market, there are solutions based on thin-film cells (e.g., cadmium telluride (CdTe), amorphous silicon (a-Si), copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS)), as well as dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSC), organic cells, quantum dots, or perovskites. These solutions are mostly known from windows and other glazed surfaces as so-called “solar glass.” In the case of balconies, they may be used as railing elements, or, in the case of loggias, as full enclosures.

Generally, the more transparent the PV cell, the fewer photons it absorbs. For this reason, they cannot match traditional silicon cells in performance, as they transmit a large portion of sunlight. Depending on the cell technology used and the level of transparency, efficiency typically remains within a few percent, rarely exceeding 10% [41,42]. Semi-transparent modules based on crystalline silicon can also be found on the market. In their case, light passes through gaps between PV cells spaced apart at fixed distances, or through micro-perforations in the PV cell structure. This, however, also results in lower efficiency compared to modules with densely packed silicon cells.

Although transparent or semi-transparent PV cells possess high aesthetic value and therefore fit well into the BIPV concept, from the perspective of the energy transition they are not the best solution, due to their low efficiency and durability, which usually falls short compared to monocrystalline silicon PV cells. Figure 5 shows on left an example of a transparent balcony railing in a hotel in Italy, based on amorphous silicon (a-Si). According to the manufacturer, its nominal power output is 34 W/m2, on the right, a project implemented in Łódź, Poland.

Figure 5.

BIPV railing made of amorphous silicon cells (a-Si), reproduced with permission of Onyx Solar [43] and other balcony solution, reproduced with permission of FIBRAIN Energy [44].

In the case of loggias, it is possible to achieve a larger PV generator surface, as the entire balcony space can be enclosed instead of mounting modules on the railing. This solution appears to be the most compatible with transparent PV cells. A surface two to three times larger than the railing itself allows for significantly higher energy yields while minimally reducing the amount of light entering the interior (depending on the chosen technology and level of transparency). It is important that the transmitted light is primarily in the visible spectrum, while photons with wavelengths not detectable by the human eye should be absorbed and converted by the PV cell into electricity as efficiently as possible.

At the same time, the loggia enclosed with transparent photovoltaic glazing enhances several aspects, including protection against weathering and air pollution, improved thermal and acoustic insulation, and greater functional usability of the available exterior surfaces.

A key consideration when selecting the appropriate PV technology for a balcony is whether priority should be given to aesthetics or efficiency. When considering the role of multi-family housing in the energy transition, it is clear that the system’s efficiency should be prioritized to maximize financial and energy benefits. Aesthetics, being highly subjective, should also be considered, especially assuming the widespread future use of balcony PV systems. Nevertheless, the several-fold differences in efficiency between solutions necessitate that investors are aware of the real benefits that the chosen technology will provide.

4. Legal and Social Development of Balcony Photovoltaics

Balcony photovoltaics is developing increasingly dynamically, making it reasonable to define the direction it will take. Two scenarios seem realistic, which will result from different forms of ownership and, in practice, will direct this branch of the energy transition along different paths. The entity responsible for the implementation and maintenance of the investment will be either the apartment owner or the property manager (e.g., a housing cooperative or condominium association). By comparing the differences (legal, technical, operational) that exist between them, it will be possible to understand the advantages and disadvantages of both development paths.

4.1. Connection to the Electrical Grid

An apartment owner, deciding to install a balcony PV system, will each time need to ensure its safe connection to the apartment’s electrical installation. Typically, this connection is made via the apartment’s distribution board or (in certain cases) through a plug socket in the nearest room (plug-in systems). The first option provides for the creation of a dedicated electrical circuit with independent protections. The second is usually used for the smallest installations (up to several hundred watts). Regardless of the chosen form, the critical aspects become the scale of such connections and the likelihood of installation errors. In the case of an investment carried out by a property manager, the installation will be significantly larger and will result from the number of balcony railings selected for PV module installation. Connection to the electrical installation will be made via the building’s main distribution board and, as a rule, will be performed by a professional PV installation company. This solution generally maximizes the safety and correctness of the installation compared to many individual balcony systems, where the correctness of the connection is not always thoroughly verified.

4.2. Energy Utilization

Households in Poland are typically able to use around 20–30% of the annual electricity yield from a PV system. The rest of the energy is fed into the grid and settled with the utility company according to the applicable tariff. The value of self-consumption can be significantly increased by using various forms of energy storage. Research [45] shows that skillful use of electrochemical storage (usually a lithium-ion battery) and thermal storage (usually a domestic hot water tank) allows achieving self-consumption levels of up to 80%. The first solution can basically be used by all PV system owners, while the second option only makes sense for apartments without a domestic hot water connection. Regardless of using energy storage, the apartment owner can influence the level of self-consumption, provided they can use household appliances (e.g., oven, washing machine, dishwasher, induction hob, vacuum cleaner) when the sun is shining. In the case of a property manager, energy use is limited to supplying so-called common areas, which include, among others, basement and stairwell lighting, elevator power, and monitoring. In this case, energy demand is independent of the property manager and depends on the needs and preferences of the building’s residents. Therefore, increasing self-consumption is more difficult, and often practically impossible.

4.3. Billing Tariff

Achieving 100% self-consumption is usually economically unjustified, which means that energy surpluses (mainly during the summer) are fed into the electrical grid. According to currently applicable regulations in Poland, owners of PV systems with an installed capacity of up to 50 kW can use the net-billing tariff. The net-billing tariff means that energy is sold at rates that fluctuate in response to market variations. In this system, the value of the electricity produced and fed into the grid is settled based on current market prices, allowing consumers to benefit from high price periods but also exposing them to increased price volatility. For this reason, energy storage systems are being increasingly implemented, as they make it possible to shift the sale of electricity to hours when market prices are at their peak. Despite the fact that the selling prices are the same for both the apartment owner and the property manager, the benefits from selling electricity differ significantly. The apartment owner (after meeting the requirements) can formally become a renewable energy prosumer, while the property manager can become a collective renewable energy prosumer. A collective prosumer, if they decide to install PV, and then “place it on the building” and connect it “behind the metering and settlement system of the common parts of a multi-apartment building with a predominant residential function, with a capacity no greater than the connection capacity of the entire building”, will, unlike the apartment owner, be able to use the entire profit from electricity sales. The condition is that the money is used to cover “obligations arising from electricity purchases or to reduce fees related to apartments in the building (…) or other buildings with a predominant residential function whose common parts are managed by this renewable energy prosumer” [46]. In short, this means the possibility of using the profit from electricity sales for common needs or building maintenance. Costs that can be covered include “administration, repair fund, heating, or waste disposal” [47]. In the case of an apartment owner, after 12 months, they can recover only 20% (in exceptional cases 30%) of the profit from electricity sales, which remains in their account after settling the electricity purchase cost. This means that even if a surplus is accumulated, most of the collected funds are lost after one year.

A certain form of cooperation is also possible within the framework of collective prosumer functioning. An investment in which the property manager, apartment owners, and other entities operating within the building participate can establish a percentage (up to four decimal places) ownership of the PV system, and based on this, proportionally reduce energy bills for all participants and distribute potential profits. The PV system is then connected to the building’s main distribution board, and supplying the common areas constitutes only part of the consumption. This solution is not very popular, despite the fact that in this option, the property manager together with the apartment owners could jointly reduce their electricity bills. The reasons can be attributed to formal-legal difficulties, low social awareness, and a lack of willingness to cooperate. Reaching an agreement may be easier in condominium associations than in housing cooperatives.

It is worth adding that according to current EU regulations [48], the owner of a PV system with a capacity not exceeding 0.8 kW (not included in the type A energy production module) is not obliged to report it to the energy utility. In practice, however, this issue is rather unclear, and other grounds (depending on the country and the local operator’s procedures) may require reporting. Generally, this is not a beneficial solution, because without reporting, the PV system owner cannot use a bidirectional meter and settle surpluses fed into the grid. This may also be important from the point of view of arrangements with the property manager. Reporting always requires written confirmation that the installation was carried out by qualified technical personnel with appropriate certifications.

4.4. Safety

An apartment owner’s investment in a balcony PV system may raise safety concerns. It is easy to imagine that with many individual connections, errors could arise that pose a threat not only to the apartment itself but also to the entire building. Even during the decision-making process, it is important to properly assess the feasibility of the installation by verifying the condition of the railing, the possibility of making a cable passage to the interior of the apartment, and the choice of connection method to the electrical grid. Next, when selecting installation components (PV modules, microinverter, mounting structure, cables, electrical protections), specialized knowledge is required to ensure the equipment configuration is correct and guarantees proper operation for years.

The mounting of the supporting structure must ensure safe positioning of the PV modules. In this case, particular attention should be paid to the risk of module falls from a great height, both during installation and as a result of improper mounting and strong wind gusts. Models of PV modules available on the market, in addition to their increasing power each year, also have increasing mass, which in the case of the largest units exceeds 30 kg. A popular solution, such as connecting the PV system via a plug-in socket, should also be preceded by verification of the apartment’s electrical installation. This is particularly important in the case of prefabricated large-panel blocks, where electrical installations in apartments often have not been modernized for decades. They are usually made with aluminum wires in a TN-C system, where the PEN conductor simultaneously serves as a protective (PE) and neutral (N) conductor. This limits protective capabilities and may cause inconsistencies with the microinverter manufacturer’s guidelines. It may also raise questions about the condition and quality of such electrical circuits and the safety of operating connected PV systems. In such cases, it is always advisable to consider a separate circuit for the PV system with dedicated protections.

A large number of PV systems connected individually in many apartments may, in some cases, affect the power parameters of the entire building. Especially when considering the diversity of microinverters (many manufacturers and even more models), which investors will use. Feeding surpluses into the grid at the same time may cause local voltage increases and generate disturbances, e.g., in the form of higher harmonics (especially in the case of cheaper models). Attention should also be paid to the issue of equipotential bonding, i.e., equalizing the potential of metal elements in the PV system, such as the mounting structure, PV module frames, or even the railing itself. If the development direction of balcony photovoltaics moves towards individual installations, it is advisable that they are always carried out by professionals or at least consulted with them.

To eliminate problems related to the electrical grid, the EN 50549 [49] standard was developed. It defines the technical requirements for connecting renewable energy installations, including photovoltaic systems, to low- and medium-voltage networks. Its main objective is to ensure that photovoltaic installations do not degrade the quality of power in the grid. The standard specifies permissible values for power factor, harmonics, flicker, and voltage asymmetry. Photovoltaic systems must include protection mechanisms against overloading, short circuits, excessive voltage, and frequency deviations. Automatic disconnection is required if the grid parameters exceed permissible limits. The EN 50549 standard forms the technical foundation for the development of photovoltaics in Europe. It ensures that PV systems can be connected safely, efficiently, and in compliance with network operator requirements. Implementing its provisions harmonizes technical requirements across European Union member states, facilitates the integration of renewable energy sources, enhances grid stability, and supports the achievement of the European Green Deal objectives [49].

An investment carried out by a property manager will, by default, constitute a single PV system. Both the decision-making process and subsequent stages are more formalized than in the case of an individual resident’s investment. On the one hand, this may prolong implementation, but on the other hand, strict adherence to regulations and rules reduces the risk of hazards. It is worth conducting a building audit and verifying possible solutions before selecting a contractor, which will depend, among other things, on electricity demand, the condition and quality of railings, the orientation of balconies, and shading. If the investment is deemed justified and approved at a member meeting (in accordance with the statute), the search for a general contractor begins. The selected contractor (usually through a tender process) is responsible for compliance of the investment with regulations and technical knowledge. They are obliged to maintain all safety and occupational health standards. The PV system is created based on a project, which should be based on reliable calculations and characterize the entire process in detail. An undoubted advantage of a single, large installation for the entire building is the possibility of using a single inverter and a complete set of protections. Within the investment, one cable passage to the building and one installation connection are made. This undoubtedly reduces the risk of errors and failures and also limits the impact on the electrical grid. Among factors increasing risk, one can distinguish the occurrence of much higher voltages in solar circuits (up to 1 kV), which in the event of cable insulation damage can pose a greater risk than in residential installations, where DC voltage usually reaches several dozen volts.

The operational lifespan of a PV system can reach several decades, so appropriate maintenance and regular inspections are crucial. Here, too, the large scale of individual residential installations may cause safety issues, e.g., due to unskillful, makeshift repairs or lack of regular inspections. In the case of a PV system owned by a property manager, compliance with inspection and service standards is usually simpler and more reliable.

4.5. Power, Cost, and Subsidies

Initial costs and potential profits differ significantly depending on the size of the PV system and its form. A small residential installation will obviously be cheaper than a large investment for the entire building. However, if one looks at the investment outlay per unit of installed power rather than total cost, it can be noticed that a large investment is more profitable. This is influenced by the scale of the investment. As is common in such cases, the unit cost decreases with the increase in the size of the PV system. The main factors determining this include lower costs for bulk purchases (PV modules, mounting structures), lower installation costs, and fewer components compared to performing each system individually. Residential installations each require the use of a microinverter, dedicated protections, an individual cable passage, and connection. In a building-wide installation, all these elements occur only once. Additionally, in the case of an installation carried out by a property manager, there is the possibility of obtaining grants from national or regional programs. In many cases, this solution significantly reduces the payback period of the investment. Residential installations, however, do not qualify for support programs, as they usually do not reach the minimum installed power. Even the most popular PV micro-installation subsidy program in Poland, “Mój Prąd”, excludes most balcony installations due to the minimum power of 2 kW.

As the installed capacity of a PV system increases, so does the scope of formal-legal requirements that must be met. According to applicable Polish regulations, installations with an installed capacity above 6.5 kW require notification to the fire department and individual approval from a fire safety expert. These are requirements that, in principle, do not cause complications and are treated as a standard procedure. In the case of a residential installation, the most difficult formal procedure concerns another requirement—obtaining installation permission from the property manager. The balcony railing, as an external part of the building, is considered one of the common parts, and the apartment owner does not have ownership rights over it. Therefore, they cannot independently decide to install a balcony system. In practice, this requirement for permission becomes the biggest problem in the entire investment process. In the vast majority of cases, property managers refuse such permission, citing safety concerns as the primary reason. The authors note that the problem often lies in the lack of appropriate procedures that the property manager could implement before issuing a decision. Proper verification of the investment planned by the resident (including safety aspects) would allow for precise identification of concerns and problems seen by the property manager. This could reduce refusals and accelerate the energy transition process in multi-family residential areas.

4.6. Aesthetics

In the longer term, balcony photovoltaics may lead to a noticeable change in the appearance of large housing estates. When individual residential installations predominate, maintaining a uniform and cohesive building aesthetic will be practically impossible. Different sizes and colors of PV modules and varied mounting methods may reduce the visual appeal and aesthetic value of the building and the entire estate. This is one reason why property managers refuse to grant permission for the installation of PV modules on railings. A compromise can be found in lightweight structures that can be easily dismantled. However, the PV modules used in these cases usually differ in efficiency from solutions typically used in commercial PV installations. Their advantages include mobility and the possibility of relocating the installation, e.g., taking it on vacation or moving to another apartment. Figure 6 shows the photovoltaic installation belonging to the Housing Community.

Figure 6.

Photovoltaic installation belonging to the Housing Community “Śląska 12”, reproduced with permission of Mazowiecka Agencja Energetyczna [50].

Considering the many factors that may influence the direction of balcony PV system development, it should be noted that there is no single solution that can be considered the best. The table (Table 2) below summarizes the issues that most clearly differentiate small residential investments from large PV installations for the entire building.

Table 2.

Comparison of differences between an apartment owner and a property manager in the context of balcony PV installations.

5. Energy Potential of Balcony PV Installations in Large-Panel Buildings in Poland

In the multi-family housing stock in Poland, there are millions of balconies. Naturally, not all of them will be suitable for the installation of a PV system. The greatest factor influencing the decision will be the investment’s profitability. The shorter the payback period, the greater the interest in installing a balcony system. Key criteria include the location and construction (shape, dimensions) of the railing. The greatest potential will be for balconies facing south and located on higher floors. Those located on the lower floors are more often shaded by trees or other buildings, especially during the winter months. A large angle at which modules are mounted on the railing is not the most favorable position in terms of maximizing yields. Even for a south-facing direction, losses (due to a non-optimal mounting angle) can reach up to 30% compared to the most optimal range for Poland, which is 30–40°. These losses increase further if there is a deviation from the southern orientation. Nevertheless, such comparisons are not meaningful if one considers that in many cases there is no alternative.

5.1. Installed Power Potential

The approximate potential of balcony photovoltaics for large-panel housing estates was estimated based on the following assumptions. The railing area of a standard balcony was assumed to be 3 m2. Considering that the number of balconies in the considered housing is estimated at ≈3 million, this gives an active area of ≈9 million m2. Due to non-optimal mounting direction (>90° deviation from south), shading from trees, neighboring buildings (Figure 1), overhangs, and a range of technical factors preventing the use of part of the railings (Figure 4), the authors propose using 30% of the estimated active area for calculations, which results in ≈2.7 million m2. The adopted numerical values are based on the data presented in Section 2.

The installable power naturally depends on the efficiency of the PV modules available on the market. Three technologies, most commonly found in balcony photovoltaics, were analyzed:

- Single-sided (monofacial) modules with monocrystalline silicon cells;

- Double-sided (bifacial) modules with monocrystalline silicon cells;

- Modules with transparent cells—made using various technologies.

As a reference point, the rated power of a PV module per m2 of balcony surface was adopted. For the first two technologies, the power was taken from the technical documentation of widely known PV module manufacturers, established under STC (Standard Test Conditions). It was assumed that the power of a bifacial module would be 10% higher due to the operation of the rear side. It was assumed that the operating conditions for the rear side of the bifacial module would be optimal, allowing it to operate with higher efficiency. At the same time, it should be noted that such conditions may not always occur under real-world conditions. The benefits and limitations of bifacial modules depend on a number of factors, which are described in Section 3.2. The third technology is much more niche and consists of many variants. For this reason, the assumed power (according to STC) exceeds the capabilities of most currently available transparent modules, assuming that the most efficient solutions will be used in the discussed installations.

Full balcony enclosure was omitted because, in the case of large-panel blocks, it would likely meet with strong social resistance. Residents would not be willing to separate the balcony space from the external surroundings. The following Equation (1) was used to calculate the potential installed power.

where

—potential installed capacity, W;

—rated PV module power per m2, W/m2;

—railing area, m2.

In the table below (Table 3), the potential installed capacity of balcony photovoltaics in large-panel buildings is presented. Based on the data presented, it is also possible to calculate any object using Formula (1). In this case, the available surface area should be measured and entered in place of Arai. On this basis, one can create custom scenarios for the potential use of different photovoltaic cell technologies, for example, for the potential of fully enclosing loggias with transparent PV. Below, an analysis is presented for the most common cases.

Table 3.

Overview of the potential installed capacity of balcony photovoltaics in Poland—in large-panel buildings.

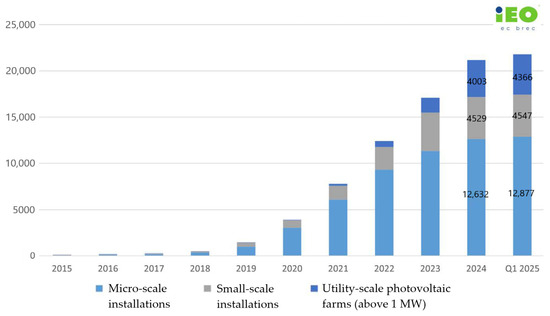

Conservative estimates indicate that the achievable increase in installed capacity amounts to several hundred megawatts. A comparison with the installed capacity of photovoltaics in Poland helps to illustrate the scale of the benefits. The chart below (Figure 7) shows the growth of installed capacity in Poland from 2015 to the first quarter of 2025.

Figure 7.

Growth of installed capacity (MW) in photovoltaics in Poland, ”reproduced with permission of EC BREC Instytut Energetyki Odnawialnej Sp. z o.o [51].

The latest data indicate that the installed capacity of photovoltaics in Poland amounts to 21.79 GW [45]. Assuming the potential of balcony photovoltaics on large-panel buildings at around 0.6 GW, the increase in capacity could be approximately 3% (2.75%). In the micro-installation segment (capacity up to 50 kW), the current capacity is 12.88 GW, which could grow by around 5% (4.66%).

5.2. Potential Annual Electricity Yield

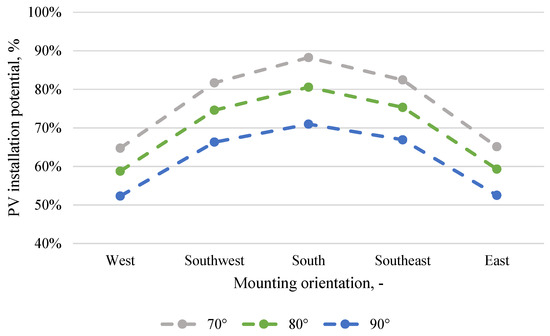

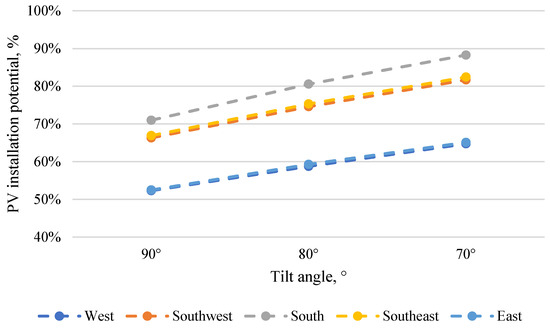

Determining the exact yield from a balcony PV installation requires an individual approach and conducting an audit. To estimate the approximate achievable amount of energy, the authors considered the orientation and tilt angle of the modules. Five orientations and three tilt angles were taken into account. The scenarios were selected based on the most commonly encountered solutions in real-world conditions. The table below (Table 4) and the chart (Figure 8) present the averaged calculation results obtained using PV yield simulation tools: PVGIS, PVSol, and Global Solar Atlas. Based on standardized models developed with these tools, the arithmetic mean of the results was calculated. The percentage values indicate the potential of a given location compared to the statistically most optimal positioning in Poland, i.e., facing south at a 35° tilt.

Table 4.

Potential of a balcony PV installation compared to the most favorable location in Poland—depending on orientation and tilt angle.

Figure 8.

Potential of a balcony PV installation compared to the most favorable location in Poland—depending on orientation and tilt angle.

The results show a significant disparity in potential, depending on the installation method. The first parameter, i.e., orientation—determined by the location of the balcony—is fixed and cannot be influenced by the investor. The second parameter—the tilt angle—can be adjusted (within certain limits), as it depends on the mounting structure used. Even a slight tilt of the modules allows for a significant improvement in energy yield. For example, the difference in potential for a south-facing installation between a module mounted at a 70° angle (88.3%) and one at 90° (71%) is almost 25% (24.37%). This is a substantial difference, considering that the investment cost in both cases is very similar. It should be noted that if PV modules are installed at too small a tilt angle (with the lower edge offset from the balustrade), they may cause shading of modules mounted on lower balconies, thereby acting as a canopy structure. Therefore, the vertical spacing between balustrades must be considered already at the design stage. The chart below (Figure 9) illustrates the increase in potential depending on the change in tilt angle for different orientations.

Figure 9.

Change in the potential of a balcony PV installation with decreasing tilt angle.

Of course, the decision to install at an angle other than 90° in most cases excludes the use of BIPV solutions on balcony railing areas. However, it allows the installation of conventional silicon-cell modules. This enables achieving high efficiency, which is the foundation for an effective and efficient energy transition.

Taking the above dependencies into account, the authors estimated the theoretical annual electricity yield, assuming an installed capacity of 0.6 GW and proportionally distributing it across 5 directions—0.12 GW for each orientation. The following Equation (2) was used to calculate the potential annual energy yield from balcony installations.

where

—annual energy yield, Wh/year;

—potential installed capacity, W;

—average annual specific yield, Wh/W/year;

—mounting-dependent factor, %.

The table below (Table 5) presents the amount of energy potentially obtainable depending on the orientation and tilt angle.

Table 5.

Theoretical annual electricity yield from balcony PV installations in Poland—in large-panel buildings (GWh/year).

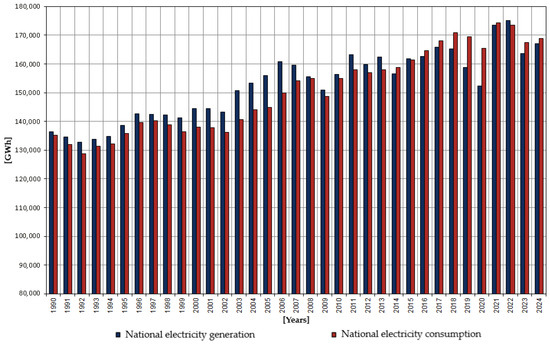

Considering the assumptions made, the potential amount of energy that can be obtained ranges between 390 and 480 GWh. According to data published by the Polish Power Grid (PSE) [52], in 2024 the electricity demand in Poland amounted to 168,956 GWh. Therefore, the share of balcony photovoltaics on large-panel buildings would range between 0.23% and 0.28% of the annual national electricity demand. The chart below (Figure 10) shows how electricity production and consumption in Poland have changed over the past decades.

Figure 10.

Electricity generation and consumption in Poland from 1990 to 2024. Source: Report PSE 2024, reproduced with permission of Polish Power Grids [52].

A steady increase in electricity demand can be observed, resulting from numerous factors, including economic development—also in sectors related to electromobility and electric heating—as well as digitalization and the rising living standards of citizens. This makes it all the more important to seek solutions capable of meeting growing needs while simultaneously supporting the objectives of the energy transition.

6. Conclusions

Investments in balcony photovoltaic systems represent a solution that has been successfully implemented in many countries worldwide. In Germany, the number of such installations has already exceeded 1.1 million, with a total installed capacity surpassing 1 GW. The vast majority of these systems have been deployed within the past three years. In 2023, 221.1 MW of new capacity was installed, followed by 437.2 MW in 2024, and an additional 446.7 MW between January and September 2025. This demonstrates a remarkable growth compared to earlier years, when newly installed capacity amounted to only 6.6 MW in 2021 and 47.4 MW in 2022. The data were obtained from the German Market Data Register [53]. The factors contributing to this rapid development include increasingly favorable regulatory conditions, among them the simplification of administrative procedures introduced in 2024 under the “Solarpaket 1” legislative framework.

The conducted analysis demonstrated the existing potential for the installation of photovoltaic systems by utilizing the unused surface of balcony railings in prefabricated large-panel buildings. Out of approximately 3 million balconies in such buildings, 30% were considered for the analysis, with the remainder excluded due to unfavorable orientation, shading, or technical limitations (Figure 4). The potential capacity that can be installed depends on the efficiency of the PV modules used. Conservative estimates indicate around 0.6 GW, which constitutes 2.75% of the total installed photovoltaic capacity in Poland (as of Q1 2025) and 4.66% when considering only micro-installations. Although their contribution to the national electricity generation would be a fraction of a percent (0.23–0.28%), balcony installations can help reduce electricity drawn from the grid, covering part of the energy needs of prefabricated large-panel buildings. The most significant factor affecting energy yield that the investor can influence is the tilt angle of the PV modules. For a south-facing installation, changing the angle from 90° to 70° can increase output by 24.37%.

However, it is not possible to develop a single, universal PV installation model for all blocks. This article presents a pathway for identifying optimal technologies and installation methods for photovoltaic systems, taking into account the orientation and tilt angle of the modules, which allows for maximizing energy yield under local conditions. Balcony railings across different housing estates vary in terms of location, local shading, and the shape and design of the railing itself (Figure 1). Therefore, it is reasonable that further research on balcony photovoltaics in prefabricated large-panel buildings should focus on developing strategies individually and independently for each housing estate in Poland. This would allow for a detailed assessment of potential benefits and provide a basis for making an informed decision regarding whether to reject or implement the investment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., M.N. and M.M.; methodology, J.P.; formal analysis, M.N.; investigation, J.P. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P., M.N. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, C.V.; visualization, C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by internal research funds from the Department of Thermodynamics and Renewable Energy Sources of Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Poland, No. 8211 104160 (MPK 9090750000).

Data Availability Statement

The data used for the research described in the article comes from cited public sources and the authors’ own calculations presented in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vassiliades, C.; Minterides, C.; Astara, O.-E.; Barone, G.; Vardopoulos, I. Socio-Economic Barriers to Adopting Energy-Saving Bioclimatic Strategies in a Mediterranean Sustainable Real Estate Setting: A Quantitative Analysis of Resident Perspectives. Energies 2023, 16, 7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalidi, A.; Alqroum, M.; Al Tmimi, A.; Khawaja, M.K. Sunflower Inspired Urban City Pattern to Improve Solar Energy Utilization in Low Solar Radiation Countries. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 48, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Yan, Z.; Ni, P.; Lei, F.; Qin, G. Promoting Solar Energy Utilization: Prediction, Analysis and Evaluation of Solar Radiation on Building Surfaces at City Scale. Energy Build. 2024, 319, 114561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Chen, S.; Ren, H.; Xu, C.; Li, G.; Li, T.; Sun, Y. A Novel Deep Learning and GIS Integrated Method for Accurate City-Scale Assessment of Building Facade Solar Energy Potential. Appl. Energy 2025, 387, 125600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh Bina, S.; Fujii, H.; Toriya, H. Innovative Methodology for Unlocking Solar Energy Potential in Japanese Urban Areas: Drone-Based DSM and Roof Shape Analysis in Akita City. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 345, 120391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorio, M.; Manni, M.; Köker, N.I.; Bertolin, C.; Thebault, M.; Lobaccaro, G. Interactive Platforms for Solar Energy Planning in Smart Cities: A State-of-the-Art Review of Solar Cadasters. Sol. Energy 2025, 287, 113227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.; Waibel, C.; Leow, S.W.; Schlueter, A. Solar Energy in the City: Data-Driven Review on Urban Photovoltaics. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 211, 115326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, L.; Wang, R.; Dong, Y.; Hou, J. Feasibility and Challenges of Quantum Dot Solar Cells in Urban Renewal Photovoltaic Buildings; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Volume 298, ISBN 1024206009. [Google Scholar]

- Onyszkiewicz, J.; Muszyńska-Łanowy, M.; Michalski, M. Energy Efficiency and Financial Viability of Urban On-Grid PV Microfarms in the Energy Transition of Central and Eastern European Countries. Energy Build. 2025, 345, 116139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliades, C.; Michael, A.; Savvides, A.; Kalogirou, S. Improvement of Passive Behaviour of Existing Buildings through the Integration of Active Solar Energy Systems. Energy 2018, 163, 1178–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhu, R.; Yan, J.; Lu, L.; Wong, M.S.; Luo, W.; Chen, M.; Zhang, F.; You, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Planning the Installation of Building-Integrated Photovoltaic Shading Devices: A GIS-Based Spatiotemporal Analysis and Optimization Approach. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 119084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, D.; Fan, C.; Hu, M.; Li, Y.; Guan, J. Building-Integrated Photovoltaics through Multi-Physics Synergies: A Critical Review of Optical, Thermal, and Electrical Models in Facade Applications. Renew. Energy 2025, 251, 123332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, J.; Peled, A.; Aronescu, A. Shadow Analysis of Photovoltaic Systems Deployed Near Obscuring Walls. Energies 2025, 18, 4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, F.; Guimarães, A.S.; Palmero-Marrero, A.I. Building Integrated Photovoltaics: A Multi-Level Design Review for Optimized Implementation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 220, 115837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frate, C.A.; de Oliveira Santos, L.; de Carvalho, P.C.M. Photovoltaic Systems for Multi-Unit Buildings: Agents’ Rationalities for Supporting Distributed Generation Diffusion in Brazil. Energy Policy 2024, 193, 114267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, G.; Vassiliades, C.; Elia, C.; Savvides, A.; Kalogirou, S. Design Optimization of a Solar System Integrated Double-Skin Façade for a Clustered Housing Unit. Renew. Energy 2023, 215, 119023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aste, N.; Del Pero, C.; Leonforte, F.; Ounis, S.; Abdelrahim, A.M.G. The Role of Photovoltaic Technology in Achieving Net Zero Energy Target in Residential Buildings. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 55, 101543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.; Perinhas, S.; Viveiros, C.; Barata, F. Increasing Economic Benefits in Renewable Energy Communities with Solar PV and Battery Storage Technologies: Insights from New Member Integration. Energies 2025, 18, 4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhraian, E.; Alier, M.; Valls Dalmau, F.; Nameni, A.; Casañ Guerrero, M.J. The Urban Rooftop Photovoltaic Potential Determination. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodneshin, M.; Alcojor, A.M.; Masseck, T. Spatial Strategies for the Renewable Energy Transition: Integrating Solar Photovoltaics into Barcelona’s Urban Morphology. Solar 2025, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoulaki, G.; Taylor, N.; Szabo, S.; Kenny, R.; Chatzipanagi, A.; Jäger-Waldau, A. Communication on the Potential of Applied PV in the European Union: Rooftops, Reservoirs, Roads (R3). EPJ Photovolt. 2024, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Maximising Solar Energy in Buildings: Fostering Deployment and Skills. Available online: https://build-up.ec.europa.eu/en/resources-and-tools/articles/maximising-solar-energy-buildings-fostering-deployment-and-skills?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Czubiński, A. Historia Powszechna XX Wieku; Wydawnictwo Poznańskie: Poznań, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marples, D. Historia ZSRR, od Rewolucji do Rozpadu; Ossolineum: Wrocław, Poland, 2006; ISBN 978-83-04-04779-9. [Google Scholar]

- Haggett, P. Encyclopedia of World Geography; Marshall Cavendish: Singapore, 2001; ISBN 0-7614-7289-4. [Google Scholar]

- KB Construction Service. Available online: https://www.kb.pl/aktualnosci/prawo-i-przepisy/skarbowka-a-social-media/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Statistical Information Centre. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/infrastruktura-komunalna-nieruchomosci/nieruchomosci-budynki-infrastruktura-komunalna/gospodarka-mieszkaniowa-i-infrastruktura-komunalna-w-2023-roku,13,18.html (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- March, L.; Martin, L. Urban Space and Structures; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1972; ISBN 0-521-08414-8. [Google Scholar]

- Property News Construction Service. Available online: https://www.propertynews.pl/mieszkania/wielka-plyta-zostaje-i-jest-na-nia-sposob,183204.html?mp=promo (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Gamdzyk, T. Osiedla Prefabrykowane w Warszawie. W: Berlin. Modernizacja Osiedli Mieszkaniowych z Wielkiej Płyty. Warszawa; Oddział Warszawski Stowarzyszenia Architektów Polskich: Warszawa, Poland, 1999; ISBN 83-901976-5-0. [Google Scholar]

- Construction Service M5. Available online: https://www.inspekcjadomu.pl/porady/technologia-wielkiej-plyty-ile-wytrzyma-mieszkanie-z-wielkiej-plyty (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Kłopotowski, M. Nowy Typoszereg Mieszkań OW-T. Mater. Bud. 2017, 1, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtualne Media Information Service. Available online: https://www.wirtualnemedia.pl/nowe-mieszkanie-deweloper-chce-wiecej-pieniedzy-za-balkon,7172650479093889a (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- OtoDom Information Service. Available online: https://www.otodom.pl/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Bielobradek, A.; Piliszek, E. Systemy Budownictwa Mieszkaniowego i Ogólnego: W-70, Szczeciński, SBO, SBM-75, WUF-T, OWT-67, WWP; Arkady: Warszawa, Poland, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wrocław Spatial Information System. Available online: https://www.geoportal.wroclaw.pl/ (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Savvides, A.; Michael, A.; Vassiliades, C.; Parpa, D.; Triantafyllidou, E.; Englezou, M. An Examination of the Design for a Prefabricated Housing Unit in Cyprus in Terms of Energy, Daylighting and Cost. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csoknyai, T.; Hrabovszky-Horváth, S.; Georgiev, Z.; Jovanovic-Popovic, M.; Stankovic, B.; Villatoro, O.; Szendrő, G. Building Stock Characteristics and Energy Performance of Residential Buildings in Eastern-European Countries. Energy Build. 2016, 132, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janusz, R.; Janus, K. Buildings Constructed in the System OWT- 67 in Urban Layout of Residential Settlement “Maki” in Lublin. Bud. I Archit. 2014, 13, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S.; Brito, M. Bifacial PV Integrated on Building Balconies. In Proceedings of the 32nd European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition (EUPVSEC), Munich, Germany, 20–24 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.A.F.; Hasan, W.Z.W.; Shafie, S.; Hamidon, M.N.; Pandey, S.S. A Review of Transparent Solar Photovoltaic Technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrou, E.; Goia, F.; Reith, A. Current Performance and Future Development Paths of Transparent PV Glazing in a Multi-Domain Perspective. Energy Build. 2023, 292, 113140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyx Solar. Available online: https://www.onyxsolar.com/torre-bassano-hotel (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- FIBRAIN Energy, Photovoltaics on Balconies in Lodz. Available online: https://energy.fibrain.com/portfo-868lio/photovoltaics-on-balconies-in-lodz/# (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Khawaja, A.; Olczak, P. Analysis of the Possibility of Increasing the Self-Consumption Rate in a Household PV Micro-Installation Due to the Storage of Electricity and Heat. Polityka Energetyczna-Energy Policy J. 2024, 27, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 20 February 2015 on Renewable Energy Sources (Journal of Laws 2015, Item 478, as Amended), Article 4c(11) and Article 4c(16), Hereinafter Referred to as the “Renewable Energy Sources Act”. Available online: https://climate-laws.org/document/act-on-renewable-energy-sources-res-act-dz-u-2015-poz-478_5b4d (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ministry of Climate and Environment. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/prosument-lokatorski (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Commission Regulation (European Union) 2016/631 of 14 April 2016. Available online: https://www.eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/631/oj/eng (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- EN 50549-1:2019; Requirements for Generating Plants to be Connected in Parallel with Distribution Networks. European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Mazowiecka Agencja Energetyczna. Available online: https://www.mae.com.pl/aktualnosci/1118-szczytno-jako-880model-nowoczesnej-modernizacji-budynkow-wizyta-studyjna-w-ramach-projektu-ceesen-bender (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Rynek Fotowoltaiki w Polsce; Report, XIII Ed.; EC BREC Instytut Energetyki Odnawialnej Sp. z o.o.: Warsaw, Poland, 2025.

- Polish Power Grids. Available online: https://www.pse.pl/dane-systemowe/funkcjonowanie-kse/raporty-roczne-z-funkcjonowania-kse-za-rok/raporty-za-rok-2024#r6_4 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- MaStR Report. Statistik zur Stromerzeugungsleistung Ausgewählter Erneuerbarer Energieträger-September 2025; Bundesnetzagentur: Bonn, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).