Abstract

Are environmental regulations the primary driver of rising electricity prices? Evidence from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) suggests a more nuanced reality. This paper examines the impact of RGGI on wholesale and retail electricity prices using a difference-in-differences framework. We analyze three key policy events—the 2005 announcement, the 2009 implementation, and the 2014 adjustment of the emissions cap—drawing on detailed panel data from power plants in both RGGI and non-RGGI states. Our results indicate that wholesale electricity prices in RGGI states did not increase following the 2005 announcement relative to non-RGGI states. By contrast, retail electricity prices rose by about 11% in the short run, coinciding with electricity market restructuring, though this retail price gap declined over time. Over the subsequent decade, RGGI states achieved substantial reductions in CO2 emissions alongside a transition to cleaner generation technologies. Importantly, the industry’s response to environmental regulation did not immediately affect electricity prices. However, as the emissions cap tightened, price effects became more pronounced: following the 2014 adjustment that reduced the cap to roughly 50% of its 2008 level, wholesale prices increased by 0.68 to 5.57 cents/kWh. These findings suggest that while the short-run effects of environmental regulation on electricity prices are limited, more stringent caps over time can lead to measurable price impacts.

1. Introduction

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) stands as a key example of how environmental regulations can reshape the energy landscape. While RGGI has been instrumental in reducing CO2 emissions, its complex effects warrant a deeper empirical investigation. This paper contributes a comprehensive difference-in-differences (DiD) analysis to reveal the intricate reality of the program’s impact, particularly on electricity prices.

Since the inception of RGGI almost two decades ago, the program has experienced several critical upgrades. To provide a comprehensive and granular understanding of its full impact, we study three key RGGI-related events separately: (1) the announcement of RGGI in late 2005, (2) the implementation of RGGI in 2008/09, and (3) the significant lowering of the emission cap in 2014. We examine each event’s impact on wholesale and retail electricity prices and the energy mix.

This study evaluates the effect of the RGGI program on electricity prices by comparing states that joined RGGI to neighboring states that did not participate in RGGI before and after the event. We use plant daily level data to study the wholesale market, concentrating on the year around each event date and focusing on RGGI while aiming to keep other policies constant. We employ two models: one with a fixed effect and another with a dynamic panel model using lagged dependent variables, separately. The results of both models enable us to use the bracketing property mentioned by [1] to deal with the biased estimation issue when a specification contains fixed effects and lagged dependent variables.

Starting with the wholesale market, the announcement of the RGGI in 2005 did not significantly affect wholesale electricity prices. However, the program’s implementation in 2008/09 led to a modest price increase of at most 5.76 $/MWh (0.5 cents/kWh). In contrast, the adjustment to the emissions cap in 2014 resulted in a more substantial price increase, ranging from $6.81 to $55.66 per MWh (0.68 to 5.57 cents/kWh).

We also examine the retail electricity market and retail electricity prices. Following the orders and regulations of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in the 1990s, several states began deregulating and restructuring their electricity markets. This deregulation influenced the power sector, where profitability is shaped by factors such as electricity prices, which the RGGI directly impacts. Therefore, our analysis needs to isolate the effect of RGGI on retail electricity prices while accounting for the broader restructuring and deregulation of these markets. To address this, the study focuses on deregulated states during each key event.

Our findings indicate that the announcement of RGGI significantly affected retail electricity prices, resulting in an increase of 1.0 to 2.1 cents/kWh, or roughly 11% to 20% of the sample’s average retail price. States participating in RGGI faced a carbon cost, which likely contributed to this initial price hike, especially following market deregulation. The transition to cleaner electricity generation sources also likely played a role in temporarily driving up retail prices. In contrast, the implementation of RGGI in 2008–2009 had no significant effect on retail prices, while the adjustment to the emissions cap in 2014 led to a 0.3 to 0.8 cent/kWh increase, representing an approximate 3% to 7% rise in retail prices.

Finally, this study offers a constructive view of RGGI’s broader impact, showing that while the immediate price response varied, the program is driving long-term shifts towards efficiency and sustainable growth. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows, with Section 2 presenting a brief literature review, and Section 3 offering background information on the RGGI and electricity markets. Section 4 describes the wholesale market’s data, methodology, and analysis. Next, Section 5 focuses on the retail market, and Section 6 discusses energy substitution. Concluding remarks are offered in Section 7.

2. Literature Review

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) is a program used to reduce CO2 emissions through tradable permits. The existing literature has extensively examined RGGI’s multidimensional consequences, including its impact on greenhouse gas emissions ([2,3,4,5,6], among others), electricity influx ([7]), health benefits ([8]), and the transition to clean energy ([9,10,11,12], among others). Critically, while some early studies projected that RGGI would increase electricity prices ([9,13]), no study has thoroughly evaluated its impact on prices ex-post. Our paper directly contributes to this gap by providing a comprehensive analysis of how three distinct RGGI events impacted both wholesale and retail electricity prices. Specifically, we aim to understand how the announcement of the new policy (2005), its inception (2008/09), and the subsequent tightening of the policy by reducing the aggregate CO2 cap (2014) affected prices in both the short-run and the long-run.

Studies on electricity market deregulation have yielded mixed and often contradictory results regarding its impact on rates. On one hand, research consistently indicates that deregulation and the restructuring of the generation sector are associated with modest reductions in generation costs and increased productive efficiency ([14,15,16]). On the other hand, the theoretical impact on retail prices is ambiguous because these efficiency gains may be offset by increased market power (markups) by generating firms. In fact, much of the recent empirical evidence finds that this exercise of market power often dominates the cost savings, leading to price increases for consumers ([17]). Furthermore, the removal of price controls has introduced higher price variation and volatility in wholesale markets ([18]). Given this complex, high-volatility pricing environment, our analysis addresses the challenge by explicitly isolating the effect of RGGI on retail prices. We carefully account for the underlying market structure, explicitly focusing on deregulated states during each key policy event.

3. The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) and Electricity Market

3.1. The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

RGGI is a mandatory, market-based program designed to mitigate carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the power sector via a cap-and-trade mechanism. Fossil-fuel power plants with a capacity exceeding 25 megawatts are required to secure allowances equivalent to their emissions over a designated three-year period. Discussions among governors from nine states commenced in 2003, culminating in an agreement signed by seven states on 20 December 2005. The inaugural auction was conducted on 25 September 2008, and the emissions cap came into effect on 1 January 2009. RGGI was established to address the critical issue of climate change by implementing a mandatory and cost-effective framework to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the power sector, in the absence of a comprehensive federal climate policy in the United States. It represents the first mandatory, market-based program in the country aimed at decreasing CO2 emissions in this sector. RGGI operates through a cooperative initiative among participating states, employing a cap-and-trade system to achieve its environmental objectives.

The cap-and-trade system of RGGI consists of two principal components: the Cap and the Trade. The Cap denotes the regional limitation on the total CO2 emissions permitted from regulated power plants within the participating states. This Cap is defined by the total number of CO2 allowances issued and is designed to become more stringent over time according to a predetermined schedule, thereby ensuring a reduction in total emissions. Initially, the Cap exceeded actual emissions, which limited incentives for companies to undertake pollution reduction efforts. This situation necessitated a significant adjustment in 2014, when the Cap was reduced by 45% from 2013 levels to more accurately reflect and drive emission reductions [19]. The Cap is scheduled to decline by 2.5% annually until 2020.

The second foundational component of RGGI is the Trade aspect. To emit one short ton of CO2, a regulated fossil-fuel power plant must possess one CO2 allowance. The finite nature of these allowances, governed by the Cap, gives rise to a market for trading. Entities that successfully reduce their emissions can sell their surplus allowances to those facing higher costs to achieve reductions, thereby creating a flexible and economically efficient compliance framework. Regulated entities must submit enough allowances to cover their emissions during a three-year “control period”, supplemented by partial annual surrender requirements. Furthermore, the system incorporates market stability mechanisms, including a Cost Containment Reserve (CCR), which releases additional allowances if prices surpass a predetermined threshold, and an Emissions Containment Reserve (ECR), which withholds allowances if market prices fall below acceptable levels.

3.2. Electricity Market

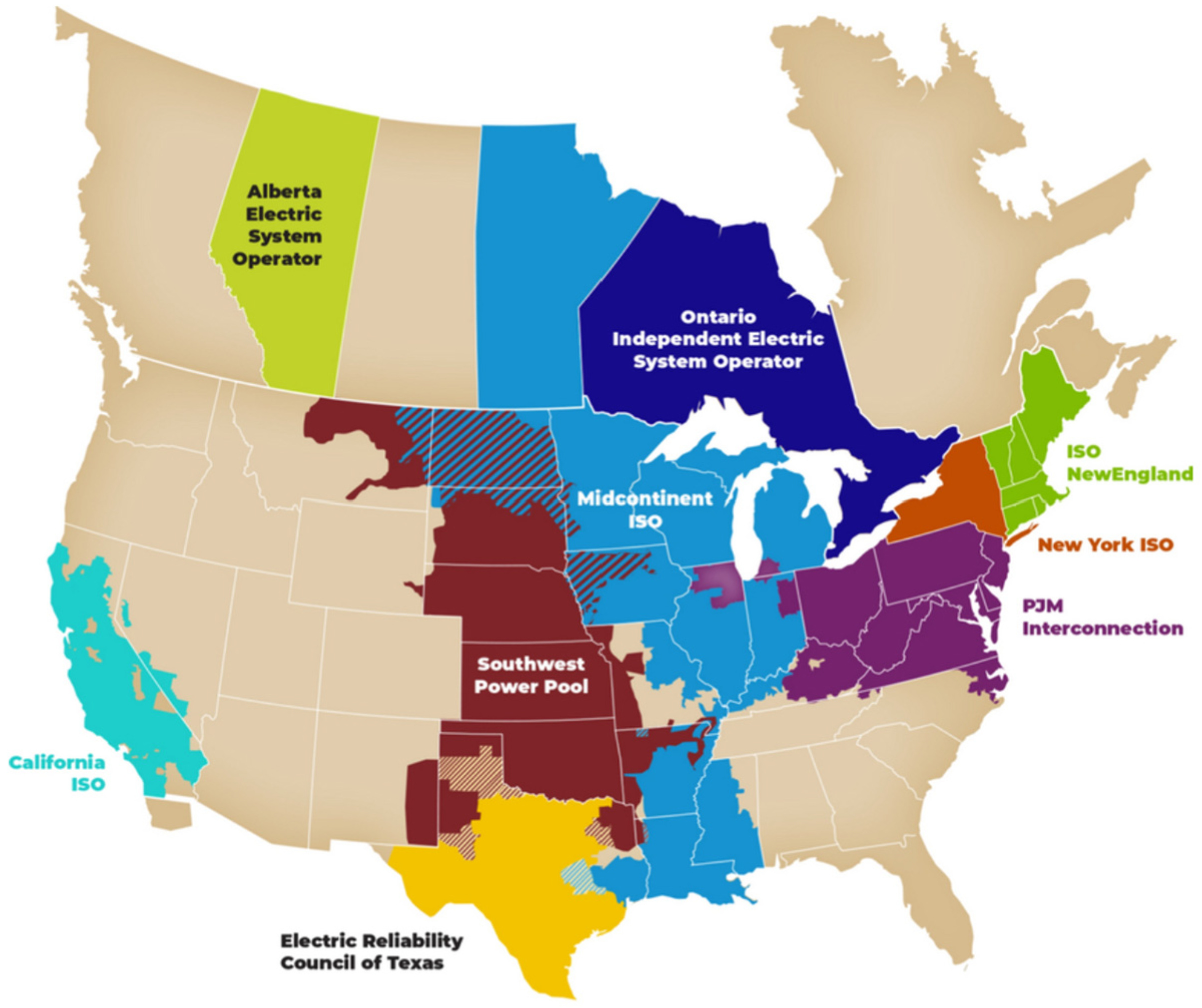

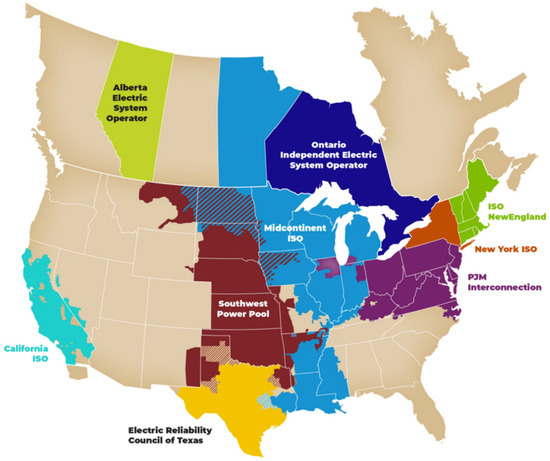

The electricity market consists of four main parts: generation, transmission, distribution, and retail. Deregulation, which began in the 1990s with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Order No. 636, separated the competitive functions of generation and retail from the natural monopolies of transmission and distribution [20]. In this deregulated environment, Independent System Operators (ISOs) and Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs) manage transmission and ensure reliability. Today, nine such organizations operate in North America, serving two-thirds of U.S. electricity consumers (Figure 1). Wholesale markets correspond to power generation, and retail markets represent the electricity purchased by end-users ([21]). Retail prices are typically higher than wholesale prices because they include fees, surcharges, and delivery costs. The relationship between these prices varies by state and local policy. Recent work has expanded the conversation to include emerging technologies and carbon market integration, with particular attention to their influence on grid dynamics and pricing structures (e.g., [22]).

Figure 1.

Map of ISOs and RTOs in North America. Source: US Energy Information Administration.

Empirical studies looking at the impact of restructuring on electricity rates yield mixed findings. Ref. [23] assess the deregulated market in Illinois and conclude that restructuring brings lower rates than adjoining states, including Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Missouri, and Wisconsin, where rates are regulated. However, while studying the restructuring in Delaware, Ref. [24] finds the opposite results–following the restructuring and removing the price cap in 2006, the retail rates increased dramatically. Delaware’s rates continue to grow because of changing fuel prices, state renewable energy policies, smart meter installation, and distribution reliability enhancement policies. The finding aligns [20], which suggests that following the electricity market restructuring, exogenous factors such as natural gas price fluctuations and generation technology advances likely caused the changes to the electricity rate.

4. The Effect of RGGI on Wholesale Prices

Environmental economics suggests that environmental policies addressing negative production externalities increase output prices. Thus, the expectation was that introducing RGGI would raise electricity prices ([25]), imposing an implicit carbon tax via cap-and-trade. However, is this what we observed? To test this, we assess the effect of RGGI on electricity prices during three distinct periods: the first is the effect of the RGGI announcement in 2005 on wholesale and retail prices; the second extends the analysis to the RGGI implementation in 2008/09; and finally, we study the adjustment of the emission cap in 2014. The outcome variable of interest is the wholesale electricity price, determined within a competitive unregulated market.

4.1. Methodology and the Identification Strategy

Our identification strategy builds upon the idea that power plants in the RGGI states respond to the event (i.e., announcement, implementation, and cap adjustment under the RGGI program). Technically, we are interested in the price difference between power plants in RGGI and non-RGGI states before and after the event in focus. Rather than a simplistic approach of pooling states and years and comparing average prices, we delve deeper into accounting for cross-sectional price variation across power plants, states, and time. Cross-sectional price variation is the systematic difference in wholesale electricity prices across power plants and states that are unrelated to the RGGI events of interest. Such differences may arise from local demand conditions, transmission constraints, or generation costs, which create persistent price gaps across units and regions. If left unaddressed, these variations could bias the estimated treatment effect. In contrast, time variation refers to temporal shocks that affect all plants simultaneously, such as seasonal demand cycles, fuel price fluctuations, or system-wide regulatory changes. We account for these variations by introducing plant fixed effects, which control for all time-invariant characteristics of each power plant (e.g., location, technology, baseline cost structure) and time-fixed effects, which capture shocks common to all plants at a given point in time (e.g., seasonal demand cycles, fuel price fluctuations). We also use state clustered standard errors to ensure a thorough and robust analysis.

Formally, we employ a difference-in-differences (DiD) method to estimate the price effects. This quasi-experimental approach compares changes in outcomes over time between a treatment group and a comparable control group, effectively differencing out unobserved factors that remain constant across groups and periods. Relying on the key assumption of parallel trends, DiD offers a clear and robust framework for isolating the impact of the intervention—in this case, capturing the price difference between power plants in RGGI and non-RGGI states before and after the event.

Let i index the power plant, s state, and t index time (day). The dependent variable, Pist, represents the wholesale price of electricity, and Dst is an indicator that takes the value of one if a power plant is located in an RGGI state in year t. The covariates Xst represent a vector of state characteristics, including population, real GDP, and natural gas prices. γi denotes plant-fixed effect, λt represents time-fixed effect, and ϵist is the error term. Standard errors are state-clustered to account for the relationship between plants within the same state. This notation leads to the following regression framework:

The parameter of interest, β1, captures the DiD impact of the event on wholesale electricity prices. A more flexible specification could allow each state to have its own time trend, while still maintaining some structure by accounting for state-specific trends. In our analysis, we will demonstrate how the results change when using this more flexible approach. As a general principle, DiD estimation with state-specific trends tends to be robust and reliable only when pre-treatment data show a clear trend that can be extended into the post-treatment period. To ensure a stable trend, we control for the state-specific monthly trend in the result tables. We also test state-specific quarterly and daily trends. Our results remain consistent across these different trend frequencies.

Equation (1) assumes the unobserved plant-specific characteristics are time-invariant. However, we use a long panel with variation over time; the time-invariant assumption may not be valid. To this end, an important confounding variable omitted here is the price of previous periods Pis(t−1), suggesting the need to include a lagged dependent variable. However, the OLS estimate is biased if the specification contains both a lagged dependent variable and state-fixed effects because the first-difference step naturally leads to a correlation between the differenced-error term and differenced-lagged dependent variable ([26]) (A typical estimator for the dynamic panel data is based on [27], relying on the assumption that the second lag of the dependent variable is independent of the error term. This assumption is too strong to satisfy in this context.). We can avoid this last concern through the bracketing property mentioned by [1]. This property solves the problem identified by [26]. Instead of considering lagged dependent variables and fixed effects simultaneously, it is applicable to run two separate regressions: one with plant fixed effects (Equation (1)) and the other with lagged dependent variables (Equation (2)).

The lagged dependent variable specification in Equation (2) replaces the plant-fixed effect (γi) with the lagged dependent variable (Pis(t−1)) while keeping all other variables the same. According to the bracketing property, the estimated DiD effect β1 from Equation (1) and Equation (2) forms the lower and upper bounds, introducing a bracket around the actual effect. When the treatment effect β1 is positive, Equation (1) comprises the upper bound, and the estimate of Equation (2) sets the lower bound. However, when the treatment effect is negative (i.e., β1 < 0), this order gets reversed, and Equation (2) estimates the upper bound. Accordingly, we estimate the lower and upper bounds for each outcome variable of interest, knowing that the difference-in-differences effect is within the range estimated by the two alternative specifications, thus developing a bracket around the actual effect.

The DiD approach assumes that the data should exhibit similar trends for the treatment and control groups before the event. To test this hypothesis, we aggregate the data at the state-month level to test for trends. Using the aggregated data, we replace the DiD indicator Dst with the interactions between the treatment indicator and the month indicators (Ds,t−τb, …, Ds,t+τa), omitting the pre-event treatment-month interaction of period t − 1, as detailed in Equation (3).

Let τb ∈ [2, …, m] and τa ∈ [0, …, q] and assume Ds,t−τb equals one if RGGI state and the event started τb months after the month t − τb, and 0 for all comparison states in all periods and all RGGI states in any month other than τb months before the event. Similarly, assume that Ds,t+τa equals one if RGGI state and the event started τa months before the month t + τa, and 0 otherwise.

where the sums on Ds,t−τb allow for (m − 1) pre-event periods, i.e., (−m, …, −2), while the sums on Ds,t+τa allow for (q + 1) post-event periods, including the event month, i.e., (0, …, q).

The estimated coefficients for each interaction term (δ−m, …, δ−2, δ0, δ1, …, δq) represent the difference in wholesale prices between the RGGI and non-RGGI states for that specific month relative to the pre-event month (t − 1). If the parallel trend assumption is valid, we should see point estimates close to zero in the pre-event period (t − m to t − 2). Furthermore, if any RGGI event impacts the wholesale electricity price, we expect the point estimates in and after the event year (t + 0 to t + q) to differ significantly from zero.

4.2. Data and Sample

We focus on three alternative periods to model the three events studied. The first is the RGGI announcement on 20 December 2005. To isolate the impact of the announcement of RGGI on electricity prices, we focus on a single electricity wholesale market, PJM, as it allows us to construct treatment and control groups. Within the PJM, New Jersey and Delaware announced the RGGI participation in 2005, followed by Maryland in 2007. We excluded Maryland from the treatment group while studying the RGGI announcement, as Maryland announced only in 2007. Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia are chosen as controls because they are neighboring non-RGGI states, sharing similar energy market structures and demographic conditions with New Jersey and Delaware. Power plants in these five states constitute our baseline sample.

The PJM provides hourly wholesale prices (LMP), along with the energy price, transmission, congestion, and losses, whose sum equals the LMP, starting from 1 June 2007. Prior to this date, only the LMP is reported. Since our focus is on the announcement year, when only the LMP is available, we concentrate on the state-level average LMP wholesale price. PJM reports both day-ahead and real-time wholesale prices. Market participants use the day-ahead prices to buy and sell electricity a day in advance to mitigate volatility, while the real-time prices reflect spot market transactions, where supply meets demand—this is the focus of our analysis. Real-time prices tend to be more volatile than day-ahead prices. To minimize noise, we aggregate the 15 min real-time price data into 24 h blocks. The analysis period spans from 1 June 2005 to 30 June 2006, including the announcement date of 20 December 2005 (We replace the missing observation with the average of two prices before and after that hour to adjust for daylight saving.). The sample selection criteria give rise to a panel of 642 power plants located in five states for one year.

The second event is the RGGI implementation. To study the impact of RGGI implementation on wholesale electricity prices, we stay with power plants in the PJM states. Specifically, we choose New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland as treatment states, while Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia are the control states. The period is from 1 June 2008 to 30 June 2009, including the first day the contract was implemented (1 January 2009). Similarly to the first event, we aggregate wholesale price data daily. The sample selection criteria give rise to a panel of 840 power plants located in six states for one year.

Finally, the third event is the lowering of the emission cap on wholesale electricity prices at the end of 2013. In particular, we choose Delaware and Maryland as treatment states, while Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia are the control states. New Jersey is excluded from the treatment group because it dropped out of RGGI in 2012. The period is from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014, including the first auction day under the revised cap (1 January 2014). The sample selection criteria give rise to a panel of 965 power plants located in five states for one year, and we aggregate the wholesale electricity price to a daily level.

We collect data for each event from a well-defined sample, comprising the six months preceding and the six months following the event in focus. We conducted a meticulous screening to ensure that we only included states that did not implement any other policy changes besides the specific event under investigation. This rigorous approach allowed us to concentrate our DiD analysis on states that remained stable in their regulatory environment during the selected time frame, apart from the changes resulting from the event of interest. To support our analysis, we use the Database of State Incentives for Renewables & Efficiency (DSIRE) as our main resource to identify any additional policies introduced during the period (One can access the database at the following URL: https://www.dsireusa.org, (accessed on 4 January 2025)).

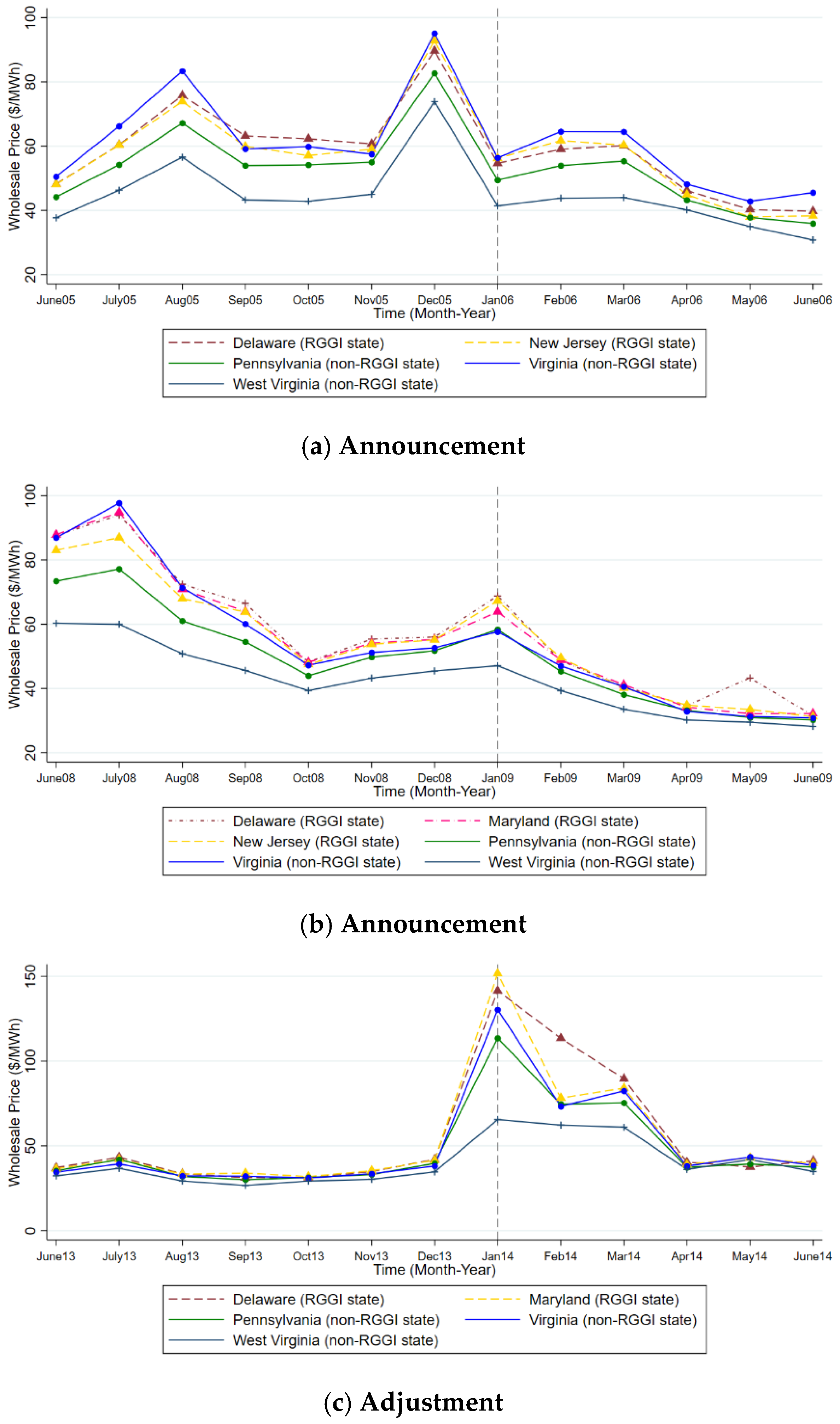

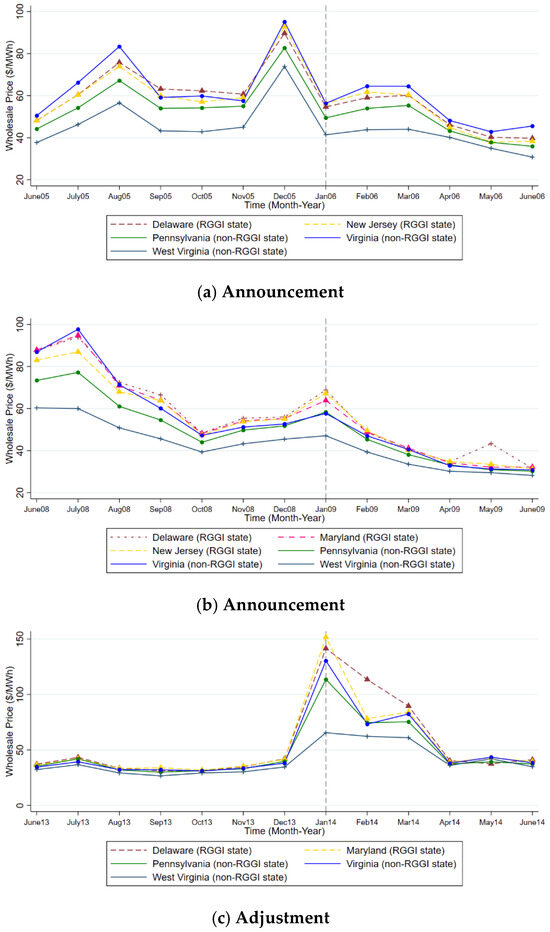

We show the wholesale electricity prices in Figure 2. We display monthly wholesale electricity prices for the six months preceding and following each event. These price movements are in sync throughout the period investigated.

Figure 2.

Trend of Wholesale Prices. Source: US Energy Information Administration and PJM. Note: This figure shows wholesale electricity prices for the six months preceding and following each event. All prices are adjusted to 2007 dollars. The dashed line denotes the time of the event studied.

4.3. Results

We show the results of the three events–the announcement, initiation of RGGI, and change in cap–in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3, respectively, wherein each of the tables, a column represents a separate regression, with the dependent variable the wholesale electricity price. Column (1) compares the average wholesale prices between power plants in RGGI and non-RGGI states before and after the event, introducing no fixed effects and thus providing a baseline estimate (DD hereafter). We include both plant-fixed effects and date-fixed effects (Equation (1)), we present the regression results in Columns (2) (FE1 hereafter). Column (3) adds the state specific time trends (FE2 hereafter). Finally, the result of a dynamic panel, i.e., Equation (2), is presented in Column (4), where we account for the first, second, and seventh lagged dependent variables (LD hereafter). To this end, the first, second, and seventh lags of prices are essential predictors of current electricity prices ([28]). We control for natural gas prices in all specifications because natural gas prices affect electricity prices ([29,30]). In addition, we include the state population and real GDP in all specifications. The parallel trend tests specified in Equation (3) are shown in Figure 3.

Table 1.

Effect of RGGI Announcement on Wholesale Prices.

Table 2.

Effect of RGGI Implementation on Wholesale Prices.

Table 3.

Effect of RGGI Adjustment on Wholesale Prices.

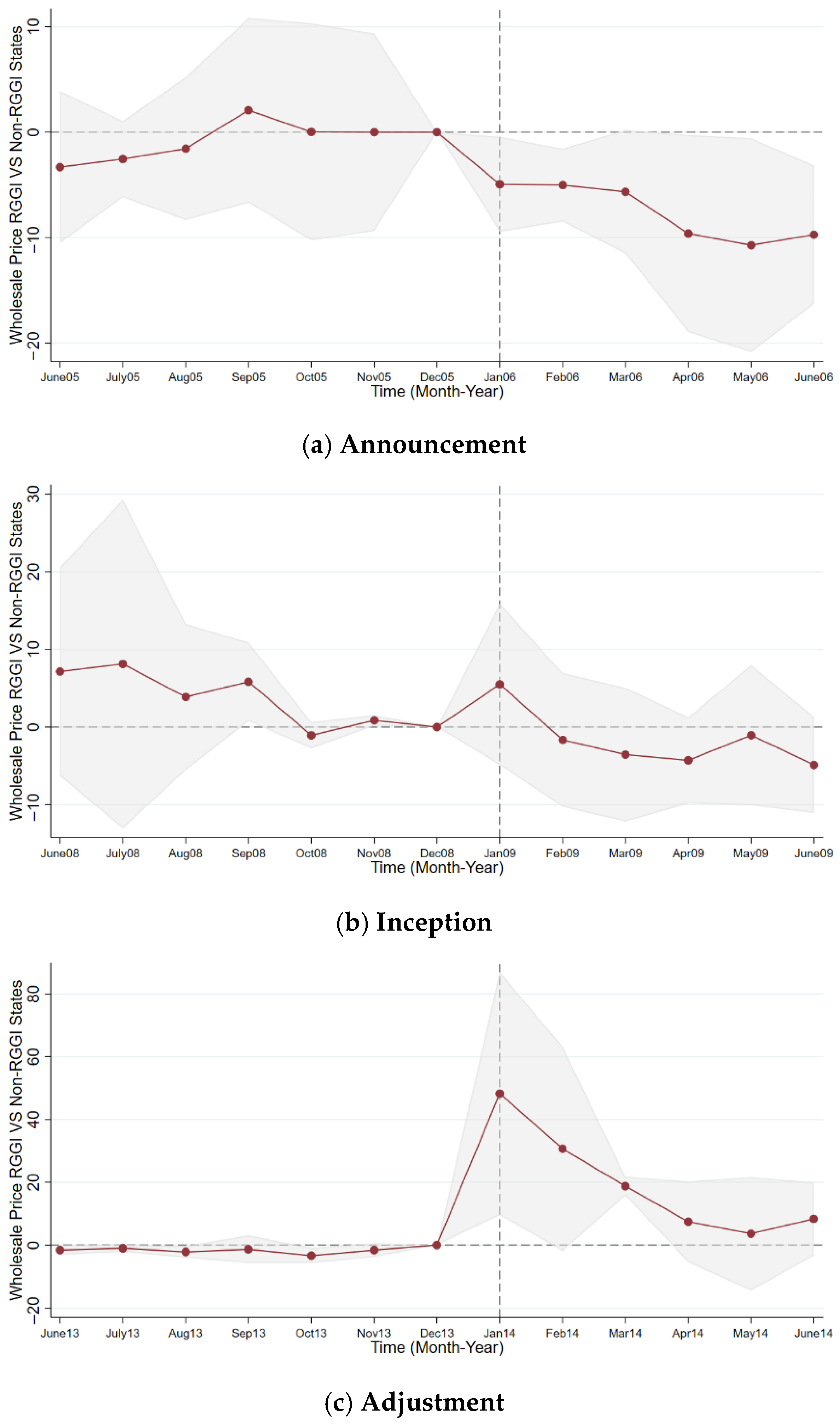

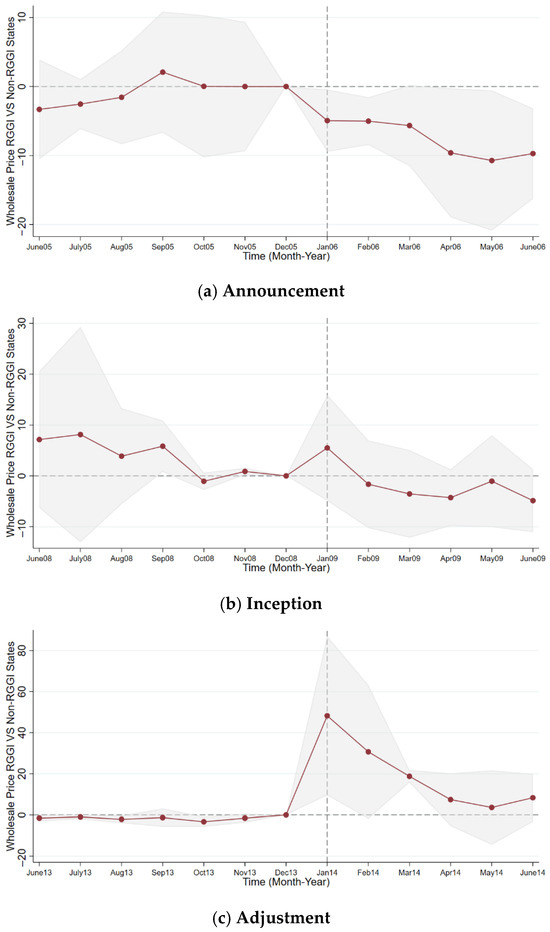

Figure 3.

Impact of RGGI Events on Wholesale Prices. Source: US Energy Information Administration. Note: Each dot represents the estimated price difference between RGGI and non-RGGI states for a given month, relative to the pre-event month. The shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval for this estimated difference. The dashed line marks the time of the event studied.

We begin by presenting the price effect of the RGGI announcement in Table 1. The results suggest that wholesale prices in the RGGI states decreased following the announcement, though the reduction is not statistically significant. Comparing different specifications shows that FE1 improves DD by increasing R2 from 0.08 to 0.81. The estimated effects remain consistent in sign with the inclusion of state-specific time trends. The dynamic panel specification (LD), which accounts for price autocorrelation, provides an upper bound for the true impact. Using the bracketing property, the FE1 and LD estimates define a range that likely encompasses the actual effect of the announcement on wholesale electricity prices. The RGGI announcement yields a change (decline) in electricity prices of −2.7 to −0.9 $/MWh (−0.03 to −0.01 cents/kWh), respectively. Both estimates are not statistically significant, suggesting that the announcement may have had no effect or a slight downward impact on wholesale prices. Figure 3a shows the results of the parallel trend in response to the RGGI announcement (specified in Equation (3)). There was a stable pre-trend and the wholesale prices in the RGGI states were slightly lower than in non-RGGI states after the event.

Next, Table 2 examines the impact of RGGI implementation in 2008/09 on wholesale prices. The results indicate that wholesale prices in the RGGI states decreased following implementation according to the FE1 specification. However, the estimated effects become significantly positive when state-specific time trends are included (FE2). Using the bracketing property, we estimate the actual effect of implementation to be between 5.76 and −0.66 $/MWh (0.57 and −0.01 cents/kWh), which implies that the implementation of RGGI may have had no impact or a small positive impact on wholesale electricity prices. This finding aligns with the results of the parallel trend analysis in Figure 3b. It shows a pre-existing downward trend, with wholesale prices in RGGI states experiencing a spike in the first month following implementation. After that, prices in RGGI states became like those in non-RGGI states.

Finally, we present the results related to lowering the emission cap in 2014. Based on the model selection criteria, the findings in Table 3 indicate that reducing the emission cap led to an increase in wholesale electricity prices, ranging from 6.8 to 55.66 $/MWh (0.68 to 5.57 cents/kWh). Figure 3c shows the results of the parallel trend in response to the RGGI adjustment (Equation (3)). There was a stable pre-trend, and the wholesale prices in the RGGI states were significantly higher than in non-RGGI states after the event.

The initial transition to renewable technologies such as wind and solar does not yield higher electricity prices. However, in 2014, policymakers substantially limited the annual allowance of CO2 emissions, and the cap-and-trade market led to higher electricity prices (Table 4). A story supporting the statistical results is that utility companies initially decommissioned the more polluting and inefficient plants, replacing the missing capacity with wind and solar. To this end, at that time the average coal plant in the United States was 42 years old, with the oldest and least efficient ones dating back to the 1940s and early 1950s (The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/a-dilemma-with-aging-coal-plants-retire-them-or-restore-them/2014/06/13/8914780a-f00a-11e3-914c-1fbd0614e2d4_story.html, (accessed on 28 November 2022)). However, once the CO2 allowance was further restricted, utilities were forced to transition away from the more efficient yet polluting plants, thus yielding higher, not lower, wholesale electricity prices. In addition to the above explanation, we suspect that the pass-through of costs to end consumers is sticky; thus, we did not observe a change in electricity prices when the aggregate pollution quota was set too high, and natural gas price uncertainty likely clouded the effect of regulation. However, when policymakers made the aggregate quota significantly lower, more extensive changes with more stringent pollution quotas led to price changes and the pass-through of costs to the end consumer, which occurred when natural gas price volatility was much lower. Thus, the effect of regulation on electricity prices was primarily observed in 2014, but not earlier.

Table 4.

Change in Wholesale Electricity Prices Because of the Events.

5. The Effect of RGGI on Retail Prices

Next, we study the impact of the three events (announcement, implementation, and cap adjustment) on retail electricity prices, investigating how much of the cost of the environmental program passes through to end users.

5.1. Data and the Identification Strategy

A critical challenge to analyze the effect of the RGGI announcement on retail prices is that many RGGI states restructured their electricity markets shortly before or during the RGGI announcement period. Restructuring and the introduction of RGGI are intertwined. Thus, before describing the results, we discuss the data and sample. Through the sample construction, we disentangle the price impacts of the RGGI announcement from the restructuring of the electricity markets.

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) tracks the retail electricity price back to the 1990s by state and end-user type. Unlike short-term wholesale prices, retail prices remain fixed over longer periods. Hence, we use annual state retail prices and investigate a more extended period, 2001 to 2017 (All prices are inflation-adjusted to the 2007 dollar.).

Each state determines retail prices independently of others, even when states belong to the same transmission market. All northeastern states are comparable in terms of the RGGI announcement effect. Therefore, unlike the wholesale electricity market study, where we compare power plants within one transmission region (e.g., PJM), we can now extend the sample to a more extended area. We focus on a subset of states from the 21 deregulated states by the year of each event (CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT, DE, MD, NJ, NY, PA, OH, IL, WV, DC, VA, IN, KY, MI, NC, and TN).

We start at 13 deregulated states from 2001 to 2007 to study the RGGI announcement in 2005. All these states deregulated their electricity market by 2000. We compare the retail prices between two groups of states:

- States that joined RGGI

- -

- In 2005: CT, DE, ME, NH, NJ, and NY

- -

- In 2007: MA, MD, and RI

- States that did not join RGGI: IL, MI, OH, and PA

Next, when studying the implementation of RGGI, we add DC to the sample of deregulated states and study the impact of RGGI implementation using data from 2006 to 2012. Among these 14 deregulated states, 9 are participants in RGGI and started implementing RGGI in 2009 (DC deregulated its electricity market in 2001. The only regulated RGGI state, VT, is excluded from the study of retail prices.).

Finally, to study the cap adjustment, we add VA to the sample (VA deregulated its electricity market in 2007.). We focus on the period 2010 to 2017. Here, we also drop NJ from the model because it left RGGI in 2011 and may cause biased estimation. Therefore, we study 8 RGGI states among 14 deregulated states for the cap adjustment in 2014.

5.2. Methodology

We employ the same DiD method to estimate the impact of RGGI events on retail prices. In particular, we compare the difference in retail prices between deregulated RGGI and non-RGGI states before and after each event in the following specification:

where s indexes state and t indexes year. The dependent variable Pst is the price of retail electricity, and Dst is the DiD indicator that takes the value of one for the RGGI states s in year t after the event. Dst equals zero for all comparison states in all periods and for RGGI states that have not yet started the event in year t.

The covariates Xst represent a vector of state characteristics, including population, real GDP, and natural gas prices. One contemporaneous event that could potentially confound the impact estimate is the state Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS), which was implemented at the same time as the RGGI (States implemented RPS in the following years: CT 2000; ME 2000; MA 2000; NJ 2001; IL 2001; MD 2004; RI 2004; PA 2005 (December 2004); DE 2005; NH 2007; NY 2008 (November 2007); OH 2008; MI 2008; DC 2005; VA 2020.). The RPS mandates increased production of energy from renewable sources such as wind, solar, biomass, and geothermal, which may affect power prices. Therefore, we introduce an RPS indicator to the analysis RPSst and explicitly control for the potential effects of the RPS using a state-time indicator, which equals one from the year a state implemented its RPS onward. γs denotes state-fixed effect.

That is, there is one indicator for each state. These fixed effects control for all time-invariant (fixed) state characteristics. λt represents year-fixed effect. That is, there is one indicator for each year. A more flexible specification could allow each state to have its own time trend by accounting for state-specific trends (γs ∗ t). In our analysis, we will demonstrate how the results change when using this more flexible approach. ϵst is the error term. We cluster standard errors by state to account for auto-correlation.

β1 is the coefficient of interest that measures the impact of the RGGI on participating states. It captures the average change in retail prices in the post-event period compared to the baseline period for RGGI states, after accounting for the same change in comparison states. The trend of comparison states serves as a counterfactual to estimate what the trend in the treatment states would have been in the absence of RGGI.

As noted above, the DiD approach assumes that the data should exhibit similar trends for the treatment and control groups before each event. Using the same methods as above to test this hypothesis, we replace the DiD indicator Dst with the interactions between the treatment indicator and the month indicators, omitting the pre-event month interaction of the period t – 1.

Now, the estimated coefficients for each interaction term (δ−m, …, δ−2, δ0, δ1, …, δq) represent the difference in retail prices between RGGI and non-RGGI states for that specific month relative to the pre-event month (t – 1). If the parallel trend assumption is valid, we should see point estimates close to zero in the pre-event period (t – m to t – 2). Furthermore, if any RGGI event impacts the retail electricity price, we expect the point estimates in and after the event year (t + 0 to t + q) to differ significantly from zero.

5.3. Results

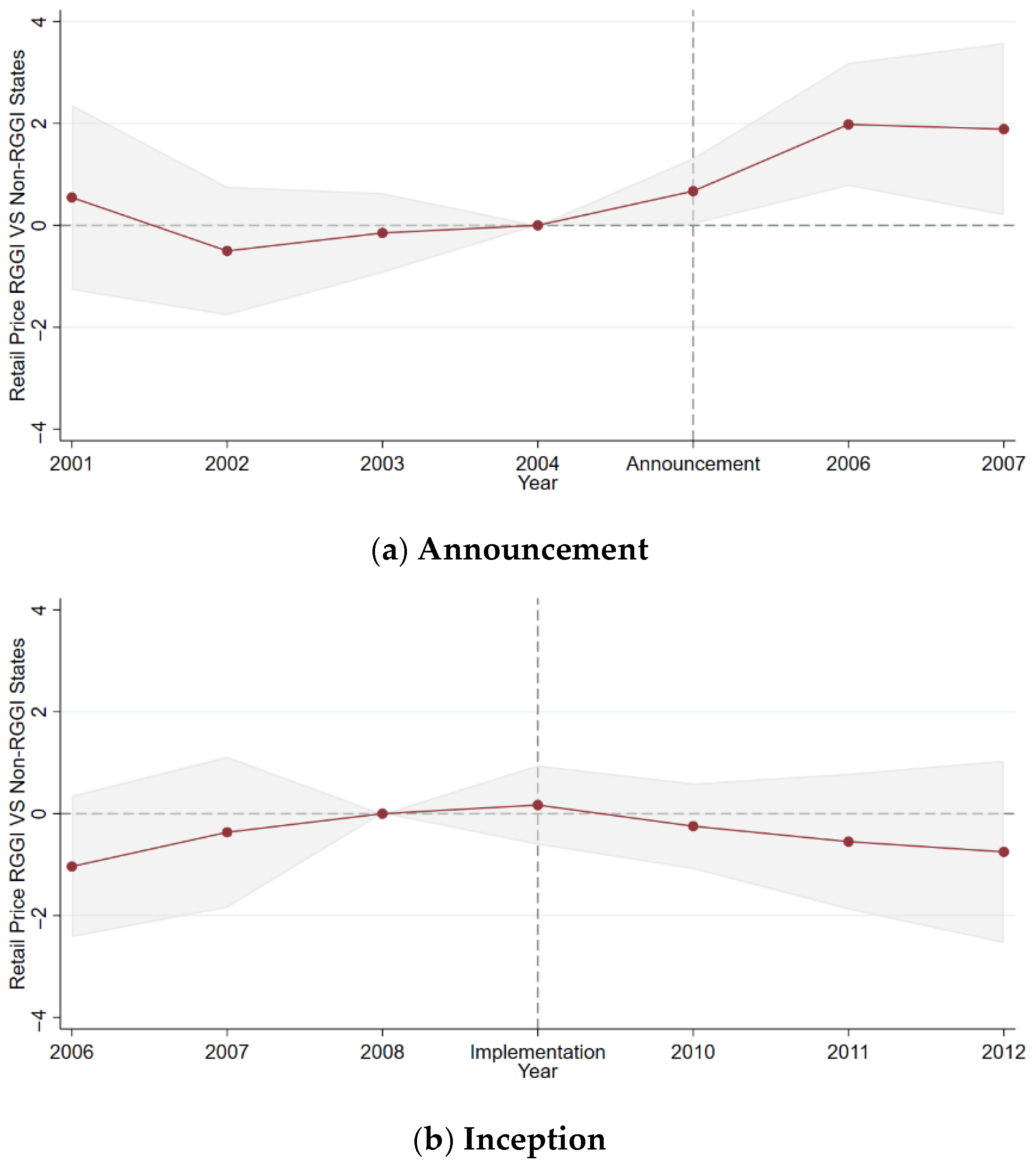

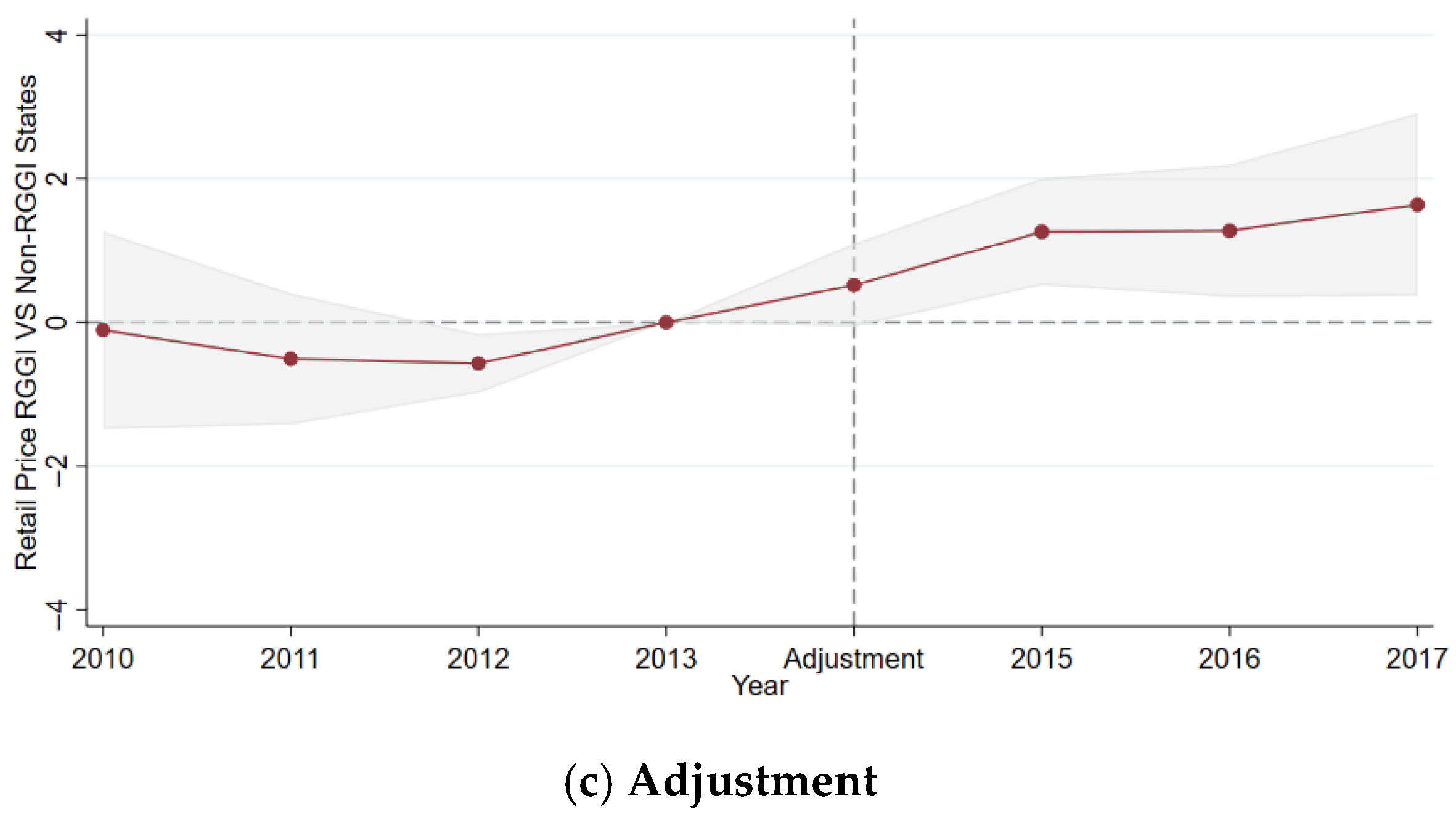

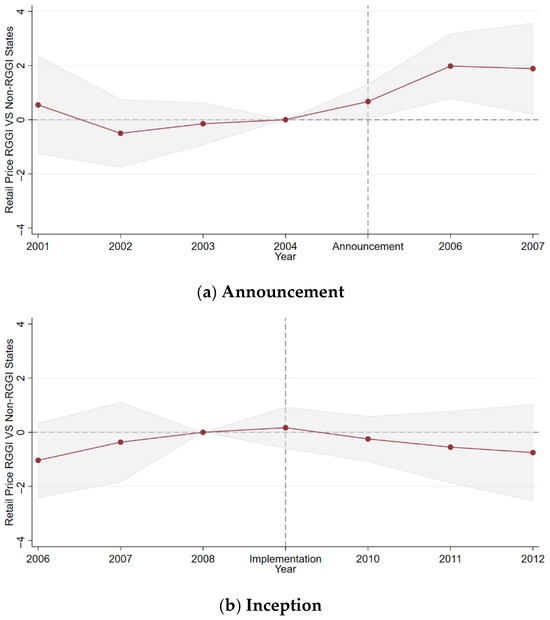

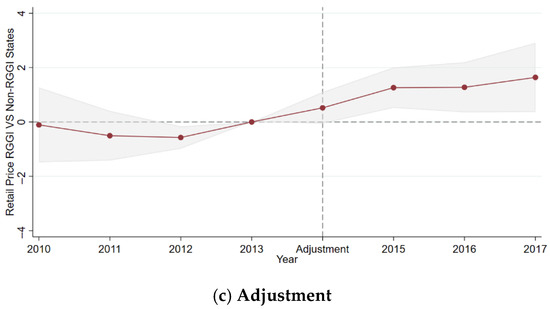

Figure 4 depicts the dynamic treatment effect of three RGGI events as specified in Equation (3) while focusing on retail prices. Each dot represents the point estimate of the difference between the RGGI states and non-RGGI states for that specific year relative to the pre-event year (t – 1), assuming all else is equal. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. The DiD estimates specified in Equation (4) are presented in Table 5.

Figure 4.

Impact of RGGI Events on Retail Prices. Source: US Energy Information Administration. Note: Each dot represents the point estimate of the price difference between RGGI and non-RGGI states for that year relative to the pre-event year. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval for the estimated difference. Dash lines indicate the years of three RGGI events: the 2005 RGGI announcement, the 2009 implementation, and the 2014 cap adjustment.

Table 5.

Change in Retail Electricity Prices Because of the Events.

Figure 4a shows that from 2001 to 2004, retail prices in both RGGI and non-RGGI states followed similar trends. However, after the announcement of RGGI in 2005, the price gap between the two groups widened. Table 5 shows that after the announcement, retail prices in the RGGI states increased by approximately 1.1 to 2.1 cents/kWh more than in non-RGGI states. The price change is statistically significant. Relative to the average retail price before the event of 10.17 cents/kWh in both groups during 2001–2004, this represents an increase of 11% to 21%. However, these differences declined afterward, and the difference between RGGI and non-RGGI states decreased over time.

The divergence in wholesale and retail prices after the 2005 RGGI announcement may reflects differences in pricing mechanisms. Wholesale prices, driven by market fundamentals, remained stable, while retail prices rose as utilities anticipated future compliance costs and adjusted rates through regulatory processes.

Figure 4b shows a slight upward trend in retail prices in both RGGI and non-RGGI states before the implementation of RGGI in 2009. This trend may reflect lingering effects from the initial announcement. However, after RGGI’s implementation, retail prices in RGGI states decreased relative to those in non-RGGI states, although the observed price change is not statistically significant. These findings are further supported by Table 5, which suggests that, following implementation, retail prices in RGGI states decreased by approximately 0.27 to 1.22 cents/kWh more than in non-RGGI states.

Finally, Figure 4c shows the impact of the RGGI cap adjustment. From 2010 to 2013, retail prices in both RGGI and non-RGGI states followed similar trends. However, since 2014, retail prices in RGGI states have increased relative to those in non-RGGI states by approximately 0.3 to 0.8 cents/kWh. This suggests that when the emission cap is binding, RGGI states may face higher pollution costs, leading to higher retail prices. Relative to the sample average retail price of 11.1 cents/kWh during the pre-event period (2009–2013), this represents an increase of 3% to 7%.

6. Energy Substitution

We examine the mechanisms that might explain the observed changes in wholesale and retail electricity prices in response to the RGGI events. One potential explanation is energy substitution. The shift from fossil fuels to clean energy could lower marginal energy costs and reduce wholesale electricity prices, as the marginal cost of generating the last kilowatt-hour through renewable energy is nearly zero ([31,32]). However, retail prices might increase due to the increased penetration of clean energy and the associated need for infrastructure upgrades ([33,34]).

Since the mid-2000s, many states have seen increased investment in infrastructure and renewable technologies, leading to a shift in the feedstock of power generation as part of the broader transition to cleaner energy sources. According to FERC, while national electricity generation overall increased by just 0.2% in 2006, renewable energy generation grew by more than 10%. Wind power capacity, for instance, expanded by 27% in 2006, reaching 11,603 MW—an investment of approximately $4 billion. During the same period, coal-based electricity generation began to decline ([3]).

We compare the energy generation feedstock in the RGGI and non-RGGI states before and after each of the three key events. Our analysis focuses on fossil fuels (coal and petroleum) and cleaner technologies, as defined from the RGGI perspective, which includes natural gas, renewable energy, and nuclear power.

6.1. Data

State-level annual net electricity generation data by energy resource is sourced from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Net generation refers to the total electricity produced, minus the energy inputs used in its generation. We calculate the ratio of electricity generated from fossil fuels and clean energy for each state and year.

6.2. Results

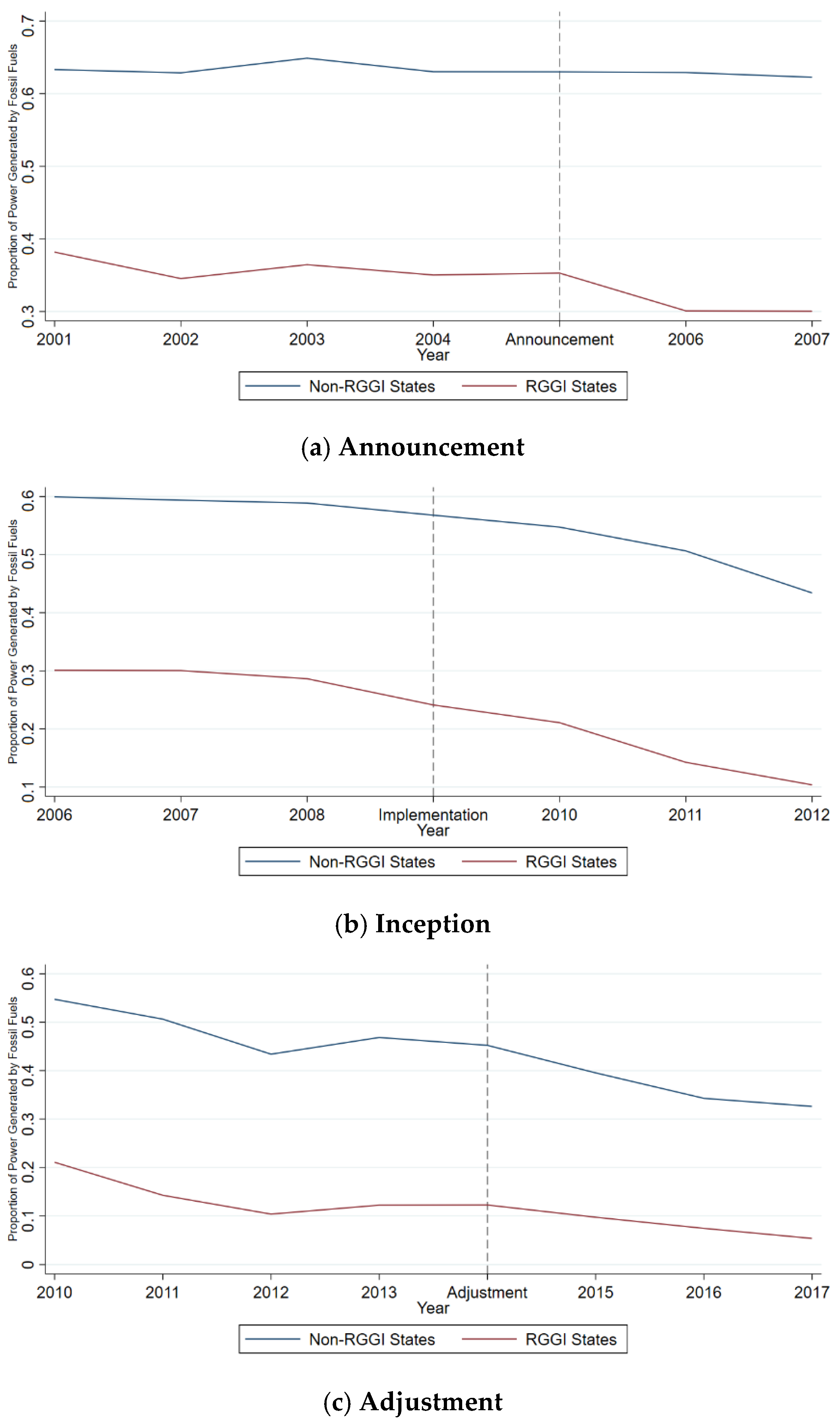

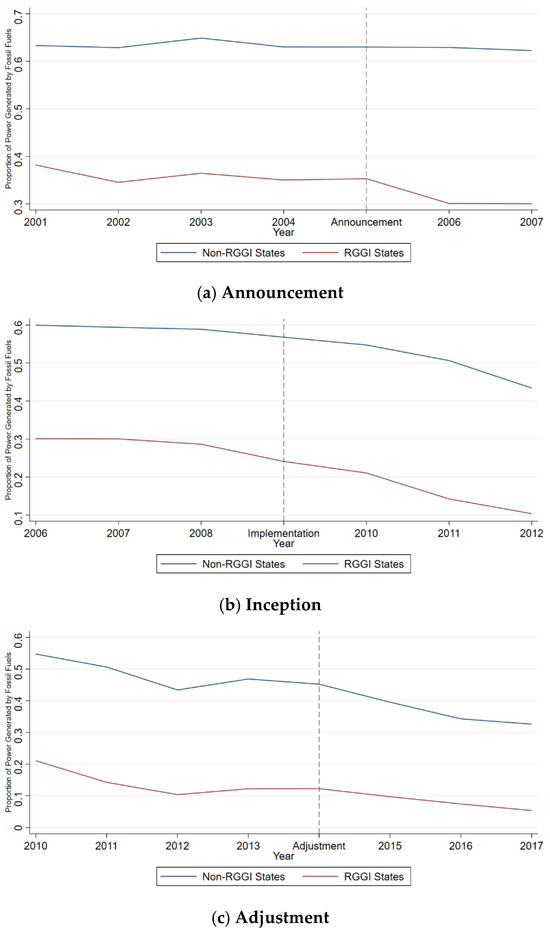

We begin by analyzing the use of coal and petroleum in electricity generation. Figure 5a shows the average share of electricity generated from fossil fuels in RGGI and non-RGGI states from 2001 to 2007. Before 2005, the trends in both groups were parallel. However, since the announcement of RGGI in 2005, the share of fossil fuel-generated electricity in RGGI states has decreased significantly, indicating the impact of the RGGI announcement in reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

Figure 5.

Impact of RGGI Events on Power Ratio by Fossil. Source: US Energy Information Administration. Note: The dashed line represents the percentage of electricity generated by fossil fuels (coal and petroleum) in non-RGGI states while the solid line shows the corresponding ratio for RGGI states.

Figure 5b compares the share of fossil fuels in electricity generation between RGGI and non-RGGI states from 2006 to 2012. While both groups show a downward trend, the gap between them remains consistent, suggesting that the decline in fossil fuel reliance was part of a broader national trend, rather than being driven by the RGGI implementation.

By the mid-2010s, after years of transitioning to clean energy, fossil fuel reliance in the power sector of RGGI states had decreased to around 10%. The adjustment to the emissions cap in 2014 further reduced the share of fossil fuels (see Figure 5c), reinforcing the shift toward cleaner electricity generation technologies. Interestingly, energy substitution in non-RGGI states accelerated in the mid-2010s, largely driven by a shift to natural gas. This change led to a more significant reduction in coal use compared to RGGI states. However, since non-RGGI states started with a higher fossil fuel share (55% in 2010), the percentage change in feedstock ratio remains more pronounced in RGGI states.

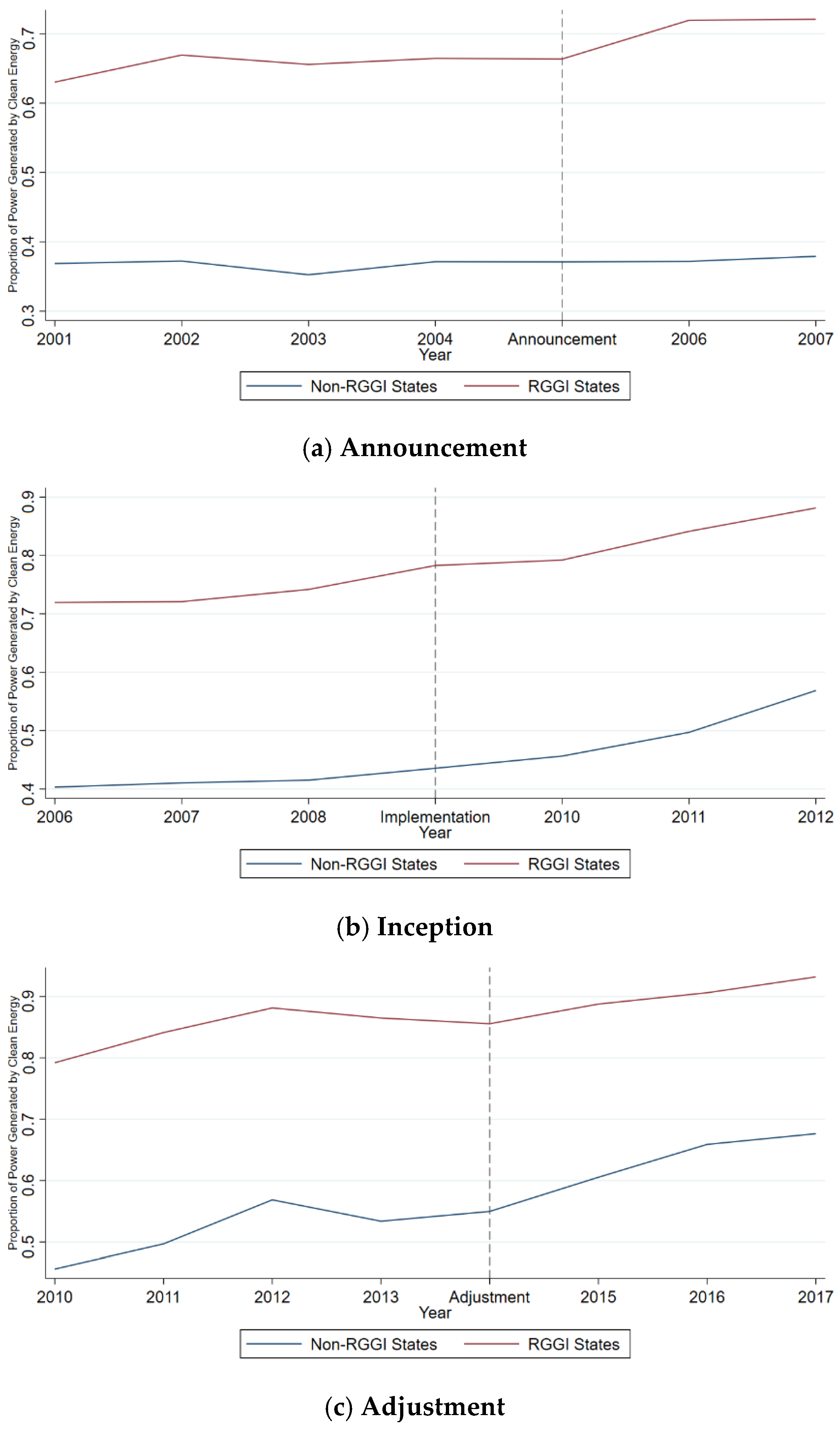

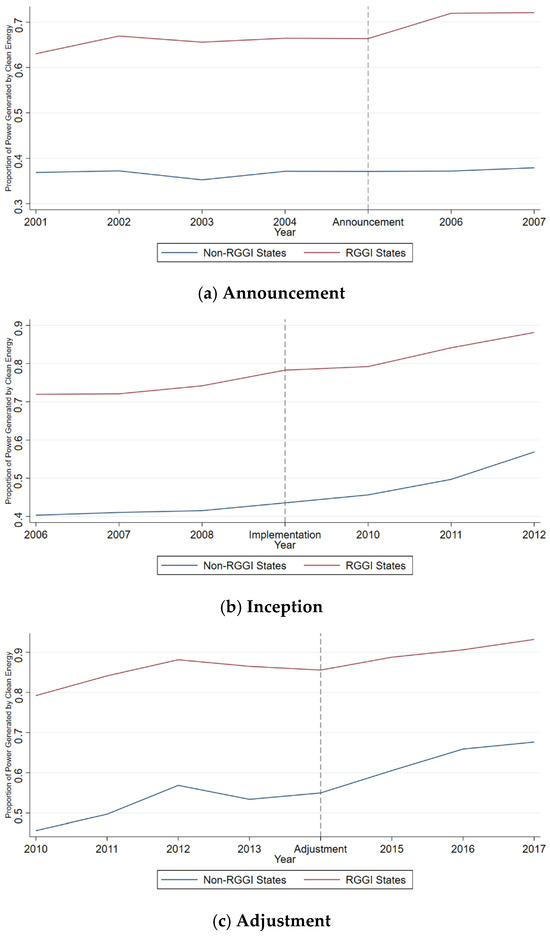

We now compare the share of electricity generated from clean energy in RGGI and non-RGGI states in response to three RGGI events. Figure 6 shows that since the 2005 announcement of RGGI, the proportion of clean energy in RGGI states has increased significantly compared to non-RGGI states. However, the implementation of RGGI in 2009 did not notably affect the energy composition in these states.

Figure 6.

Impact of RGGI Events on Power Ratio by Clean Energy. Source: US Energy Information Administration. Note: The dashed line represents the percentage of electricity generated from clean energy sources (natural gas, renewables, and nuclear) in non-RGGI states, while the solid line shows the corresponding ratio for RGGI states.

In the mid-2010s, the ratio of clean energy in non-RGGI states grew more rapidly than in RGGI states for two possible reasons: (1) Non-RGGI states like Pennsylvania and West Virginia made substantial investments in natural gas, which is considered clean energy from the RGGI perspective. (2) The share of clean energy in RGGI states had already reached as high as 89% by the mid-2010s, and due to diminishing returns in clean energy production, further increases in clean energy share became more costly.

Markets and retail prices in 2013–14 responded differently than in 2008–09. We suspect that this time, the magnitude of the change in the CO2 allowance and the volatility of natural gas prices affected electricity prices differently. Specifically, in 2008–2009, the average CO2 allowance price was $2.48, which, relative to the average wholesale electricity price of $62.68/MWh during the same period, accounted for just 3% of the electricity price. In contrast, natural gas prices were highly volatile, with an average Henry Hub price of $6.40 per million BTU and a standard deviation of 3.48. The uncertainty driven by this volatility in natural gas prices dominated the markets and influenced their response more than the CO2 allowance price.

However, during 2013–2014, when the allowance price reached $4.78, it accounted for 14% of the average wholesale electricity price ($34.74/MWh) during the same period. With natural gas prices dropping to an average of $4.05 per million BTU and a significantly lower standard deviation of 0.45, utilities and markets responded more aggressively to RGGI. In other words, the volatility of natural gas prices had previously masked the impact of environmental regulation in the 2000s, but as natural gas prices stabilized, the influence of price volatility diminished. At the same time, the tightening of the allowance cap became more impactful.

Despite this, the share of clean energy generation in RGGI states has continued to rise since 2014, indicating that the emissions cap has likely incentivized further adoption of clean energy. The transition to cleaner energy sources began in the mid-2000s, characterized by increased clean energy penetration and a decline in fossil fuel use.

7. Concluding Remarks

Our analysis of wholesale and retail electricity markets from 2004 to 2017 reveals distinct responses to the RGGI announcement in 2005 and its subsequent 2014 adjustment. The paper shows that introducing RGGI signaled a shift towards stricter environmental regulations, leading to a transition from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states. This transition was marked by a significant decline in coal and oil consumption in electricity generation, reaching less than 10% by 2017 from over 60% in the early 2000s.

The RGGI solidified the commitment of state governments to reduce CO2 emissions and promote a cleaner economy. While retail prices initially increased to support investments in alternative energy technologies, they eventually stabilized. However, the 2014 RGGI adjustment, which tightened the emissions cap, led to a further rise in wholesale electricity prices due to the need to retire more efficient but still polluting plants. The outcome of our analysis suggests a more complex relation between environmental regulation and electricity prices and the importance of understanding the nuances introduced by alternative market structures on the final price.

Our findings highlight the complex interplay between market forces, environmental regulations, and energy transition. The RGGI played a crucial role in driving the shift towards cleaner energy sources, but it also had economic implications regarding electricity prices. The introduction of RGGI initially incentivized the retirement of inefficient plants, but deeper decarbonization required the replacement of even efficient but polluting technologies. This substitution contributed to the increase in electricity prices, particularly in 2014, when regulators significantly reduced the RGGI cap. Understanding these dynamics is essential for policymakers and stakeholders as they transition to a more sustainable energy future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.S. and G.H.; Methodology, Z.S.; Validation, G.H.; Formal analysis, Z.S.; Investigation, G.H.; Data curation, Z.S.; Writing—original draft, Z.S.; Writing—review and editing, G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science Foundation Chemical Catalysis Program of the Chemistry Division, grant number CHE-1665146 and Collaborative Research: CAS: Electrochemical Approaches to Sustainable Dinitrogen Fixation, grant number Award 1955014. The research was also partially funded by the Multi-State Hatch NC1034.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alan S. Goldman and Frank A. Felder for their infinitely valuable insights and suggestions. The authors also thank Patrick L. Holland, David R. Just, James M Mayer, Alexander J. M. Miller, Farhed Shah, and Yusuke Kuwayama for their valuable comments. The authors thank the National Science Foundation Chemical Catalysis Program of the Chemistry Division for funding this collaborative project through Grant CHE-1665146 and Collaborative Research: CAS: Electrochemical Approaches to Sustainable Dinitrogen Fixation Award 1955014. The authors also thank USDA/NIFA multi-state hatch NC1034 for partial financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.-S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Does a regional greenhouse gas policy make sense? a case study of carbon leakage and emissions spillover. Energy Econ. 2009, 31, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FERC. Markets Report; Technical Report; Federal Energy Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2006.

- Murray, B.C.; Maniloff, P.T. Why have greenhouse emissions in rggi states declined? an econometric attribution to economic, energy market, and policy factors. Energy Econ. 2015, 51, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J. The impact of climate policy on fossil fuel consumption: Evidence from the regional greenhouse gas initiative (rggi). Energy Econ. 2021, 100, 105333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, L. How regional policies reduce carbon emissions in electricity markets: Fuel switching or emission leakage. Energy Econ. 2021, 97, 105209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Melstrom, R.T. Evidence of increased electricity influx following the regional greenhouse gas initiative. Energy Econ. 2018, 76, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manion, M.; Zarakas, C.; Wnuck, S.; Haskell, J.; Belova, A.; Cooley, D.; Mayo, L. Analysis of the public health impacts of the regional greenhouse gas initiative, 2009–2014. Abt Assoc. 2017, 11, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Burtraw, D.; Kahn, D.; Palmer, K. CO2 allowance allocation in the regional greenhouse gas initiative and the effect on electricity investors. Electr. J. 2006, 19, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fell, H.; Maniloff, P. Leakage in regional environmental policy: The case of the regional greenhouse gas initiative. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 87, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhou, Y. Carbon prices and fuel switching: A quasi-experiment in electricity markets. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2019, 74, 53–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-K.; Kim, T. Estimating impact of regional greenhouse gas initiative on coal to gas switching using synthetic control methods. Energy Econ. 2016, 59, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, B.R. How did rggi do it: Political economy and emissions auctions. Ecol. LQ 2013, 40, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio, K.R.; Rose, N.L.; Wolfram, C.D. Do Markets Reduce Costs? Assessing the Impact of Regulatory Restructuring on U.S. Electric Generation Efficiency. Am. Econ. Rev. 2007, 97, 1250–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.W.; Wolfram, C. Deregulation, Consolidation, and Efficiency: Evidence from U.S. Nuclear Power. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2012, 4, 194–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicala, S. When Does Regulation Distort Costs? Lessons from Fuel Procurement in U.S. Electricity Generation. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 411–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, A.; Mercadal, I. Deregulation, Market Power, and Prices: Evidence from the Electricity Sector; CEEPR WP 2022-008; MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Knittel, C.R.; Roberts, M.R. An Empirical Examination of Deregulated Electricity Prices (October 30, 2001). POWER Working Paper No. PWP-087. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=294382 (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Ramseur, J.L. The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative: Lessons Learned and Issues for Policy Makers; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Borenstein, S.; Bushnell, J. The us electricity industry after 20 years of restructuring. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2015, 7, 437–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, J.B.; Mansur, E.T.; Saravia, C. Vertical arrangements, market structure, and competition: An analysis of restructured us electricity markets. Am. Econ. Rev. 2008, 98, 237–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Shao, Z.; Jian, L. Grid Integration of Electric Vehicles within Electricity and Carbon Markets: A Comprehensive Overview. eTransportation 2025, 25, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.L.; Loomis, D. An assessment of the impact of deregulation on the relative price of electricity in Illinois. Electr. J. 2008, 21, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-M. The us electricity market twenty years after restructuring: A review experience in the state of delaware. Util. Policy 2019, 57, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, J.E. Carbon pricing in the northeast: Looking through a legal lens. Natl. Tax J. 2017, 70, 855–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, S. Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1981, 49, 1417–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, J.; Espinola, R.; Nogales, F.J.; Conejo, A.J. Arima models to predict next-day electricity prices. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2003, 18, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asche, F.; Osmundsen, P.; Sandsmark, M. The UK market for natural gas, oil and electricity: Are the prices decoupled? Energy J. 2006, 27, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhi, A.; Bahrami, S.; Ranjbar, A.M. An autonomous demand response program for electricity and natural gas networks in smart energy hubs. Energy 2015, 89, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillig, M.; Jung, M.; Karl, J. The impact of renewables on electricity prices in Germany–an estimation based on historic spot prices in the years 2011–2013. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, G.R. Are renewable energy technologies cost competitive for electricity generation? Renew. Energy 2021, 180, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, D.S.; Fowlie, M.; McCormick, G. Location, location, location: The variable value of renewable energy and demand-side efficiency resources. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2018, 5, 39–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobos, P.H.; Erickson, J.D.; Drennen, T.E. Technological learning and renewable energy costs: Implications for us renewable energy policy. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1645–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).