Abstract

Photovoltaic (PV) panel defect detection is essential for maintaining power generation efficiency and ensuring the safe operation of solar plants. Conventional detectors often suffer from low accuracy and limited adaptability to multi-scale defects. To address this issue, we propose YOLO-PV, an enhanced YOLO11n-based model incorporating three novel modules: the Enhanced Hybrid Multi-Scale Block (EHMSB), the Efficient Scale-Specific Attention Block (ESMSAB), and the ESMSAB-FPN for refined multi-scale feature fusion. YOLO-PV is evaluated on the PVEL-AD dataset and compared against representative detectors including YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, YOLOv8n, YOLO11n, Faster R-CNN, and RT-DETR. Experimental results demonstrate that YOLO-PV achieves a 6.7% increase in Precision, a 2.9% improvement in mAP@0.5, and a 4.4% improvement in mAP@0.5:0.95, while maintaining real-time performance. These results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed modules in enhancing detection accuracy for PV defect inspection, providing a reliable and efficient solution for smart PV maintenance.

1. Introduction

Driven by the global “dual-carbon” targets and the ongoing clean energy revolution, PV power generation has rapidly emerged in the field of renewable energy due to its advantages of environmental friendliness, resource abundance, and continuously decreasing cost, making it one of the most promising energy sources. As the core component of PV power generation systems, the quality of photovoltaic modules directly determines the power conversion efficiency and operational stability of the entire system. However, owing to complex manufacturing processes and long-term environmental exposure, PV cells are prone to various defects during production and operation, such as micro-cracks, broken grid lines, solder joint failures, hot-spot effects, and surface soiling [1,2]. These defects not only reduce the efficiency of PV modules but may also trigger thermal runaway, breakdown, or even fire hazards, thereby posing serious threats to the stability of the power grid.

Therefore, achieving efficient, accurate, and automated detection of photovoltaic cell defects is of great significance for ensuring the safety of PV power plants, improving power generation efficiency, and promoting industrial upgrading.

In the early stages, PV defect detection mainly relied on manual visual inspection and traditional image processing methods, such as edge detection, threshold segmentation, and morphological operations. However, manual inspection suffers from low efficiency and high subjectivity, often leading to missed detections due to operator fatigue or insufficient experience. Traditional image processing methods, on the other hand, depend on handcrafted features, which exhibit poor robustness and limited adaptability to environmental variations such as illumination, noise, and reflections. Consequently, deep learning–based defect detection methods have gradually become a research hotspot in recent years. In 2023, Mazen et al. [3] proposed a defect detection system for electroluminescence (EL) images based on deep convolutional neural networks. The system employed multi-layer convolutional networks to extract multi-scale features and integrated an attention mechanism to enhance the focus on local defect regions. The research team evaluated the model on a PV module dataset containing multiple defect categories, including cracks, broken grid lines, and hot spots. The system achieved an accuracy of 95.7% and a recall of 93.4%, demonstrating strong adaptability in handling complex textures and low-contrast defects.

Jha et al. [4] proposed a semi-supervised semantic segmentation framework to address the strong reliance of traditional deep learning methods on large amounts of annotated samples. By leveraging pseudo-labeling and consistency regularization strategies, the framework achieved a 9% improvement in IoU, a 6.8% increase in Precision, and a 7.3% gain in F1-score while requiring only 20% of the labeled data. This approach provides a novel solution for reducing annotation costs and enhancing model robustness, making it particularly suitable for industrial scenarios where manual labeling is expensive and labor-intensive.

As a representative class of one-stage object detectors, the YOLO family of models has been widely applied in PV defect detection owing to their advantages of high speed and accuracy. Zhang et al. [5] developed a lightweight NAS-based network with knowledge distillation to further optimize detection efficiency for photovoltaic EL images. Li et al. [6] proposed an improved version, GBH YOLOv5, to overcome the limitations of the original YOLOv5 model. The network integrates the GhostConv module to reduce redundant feature computation, employs the BottleneckCSP structure to enhance semantic information transmission, and incorporates a dedicated TinyTargetBranch in the detection head to improve the detection of small defects such as hidden cracks and fine fractures. On a constructed PV defect image dataset, GBH YOLOv5 achieved a remarkable increase in mAP from 65.1% to 92.9%—an improvement of 27.8%—while maintaining lightweight characteristics, thereby demonstrating the synergistic benefits of structural optimization and multi-scale perception. In terms of network architecture performance comparison, Ghahremani et al. [7] systematically evaluated YOLOv10 and YOLOv11 for photovoltaic defect detection using an electroluminescence image dataset covering multiple common defect categories such as micro-cracks, broken grid lines, and foreign object occlusion. YOLOv11 achieved the best overall performance, with mAP of 92.7%, Precision of 91.2%, Recall of 93.6%, and FPS of 87.1, outperforming other versions, particularly in occlusion and small-object dense scenarios.

Wang et al. [8] proposed an improved YOLOv5 model incorporating the CBAM attention mechanism. By optimizing convolutional structures and channel attention strategies, the model achieved an accuracy increase from 88.6% to 92.3% on the PVEL-AD dataset. Similarly, Zhang and Xiao [9] proposed an improved YOLOv5 algorithm for solar cell surface defect detection, optimizing the backbone and detection head structures and applying image augmentation strategies to enhance classification accuracy across multiple defect categories.

Although the aforementioned studies have made innovations in model lightweighting, multi-scale detection, small-object recognition, and data efficiency, several common issues still remain:

- Insufficient multi-receptive field modeling capability: Many existing methods remain relatively simple in terms of convolutional kernel scales and contextual integration, leading to inadequate feature representation for extremely small cracks and hidden defects.

- Limited cross-scale fusion mechanisms: Most approaches adopt conventional FPN or PAN architectures, failing to fully exploit the potential of integrating shallow and deep features.

- Perform structural pruning on Difficulty balancing lightweight design and accuracy: While introducing attention mechanisms or NAS-based networks can improve accuracy, they often increase computational complexity and inference latency, making them unsuitable for high real-time detection scenarios.

To address the aforementioned issues, this work builds upon YOLO11n and introduces customized improvements tailored for photovoltaic (PV) cell defect detection, proposing a multi-module fusion strategy that balances detection accuracy and real-time performance. The main contributions are as follows:

- To address the problem of insufficient feature representation caused by large scale variations, we propose the EHMSB multi-scale lightweight aggregation module. By introducing multiple receptive fields (3 × 3, 5 × 5, 7 × 7) through a channel-splitting strategy, EHMSB jointly models local details and global context while maintaining low computational cost, thereby significantly enhancing the representation ability for defects of different sizes.

- To overcome the mismatch between semantic abstraction and spatial resolution across feature layers, we design the ESMSAB cross-scale alignment and fusion module. By employing differentiated sampling paths for scale alignment and depthwise separable convolutions (DWConv) for efficient context interaction, ESMSAB preserves fine-grained spatial details from shallow layers while enriching semantic information from deeper layers, which effectively improves the localization accuracy of small defects.

- To resolve the limited feature interaction and poor robustness of traditional FPNs in complex backgrounds, we construct a dual-path adaptive fusion FPN. This structure preserves both shallow spatial details and deep semantic features during fusion and employs an adaptive mechanism to achieve complementary integration. As a result, the model achieves a better balance between detection accuracy and robustness, particularly in detecting small defects and defects within complex textures.

2. Methods

This work addresses the multi-scale nature, fine-texture characteristics, and deployment efficiency requirements of PV cell defect detection by proposing a PV cell defect detection method based on an improved YOLO11n model. Building upon the original backbone of YOLO11n, the new model integrates three key modules: the multi-scale lightweight aggregation module (EHMSB), the cross-scale alignment fusion module (ESMSAB), and the dual-path context-enhanced FPN structure (ESMSAB-FPN). These modules aim to improve detection accuracy and robustness without increasing the overall model complexity.

2.1. The Network Architecture of the YOLO11n Model

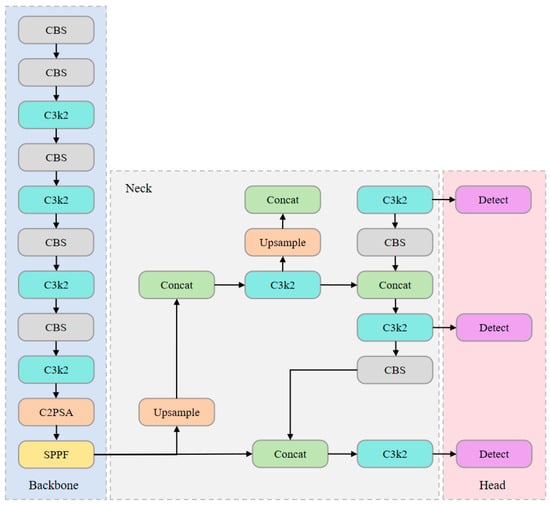

YOLO11n is the latest version of the YOLO series of lightweight object detection models. Its architecture reduces model size and computational complexity while maintaining detection accuracy. The model continues the YOLO series’ “end-to-end, single-stage” detection philosophy, incorporating multiple structural optimizations within the Backbone, Neck, and Head modules. The network architecture is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

YOLO11n model network structure diagram.

The Backbone employs multiple layers of CBS (Convolution + Batch Normalization + SiLU) modules and a lightweight C3K2 residual structure for feature extraction, enhancing the local receptive field and feature representation capability. To further improve the model’s perception of objects in complex scenarios, the SPPF structure is introduced to expand the receptive field, while the C2PSA module is integrated to implement an efficient attention mechanism, thereby enhancing inter-channel semantic modeling capability [10]. In the Neck, an improved FPN + PAN structure is adopted. Through multi-scale feature fusion and upsampling operations, high-resolution information is preserved, while depthwise separable convolutions are employed to reduce parameter overhead [11]. Finally, the Head is based on an anchor-free design, directly predicting object centers, sizes, and classes, combined with an improved CIoU loss function to optimize bounding box regression [12]. In summary, YOLO11n achieves an excellent balance between speed and accuracy, making it particularly suitable for edge computing and real-time detection scenarios.

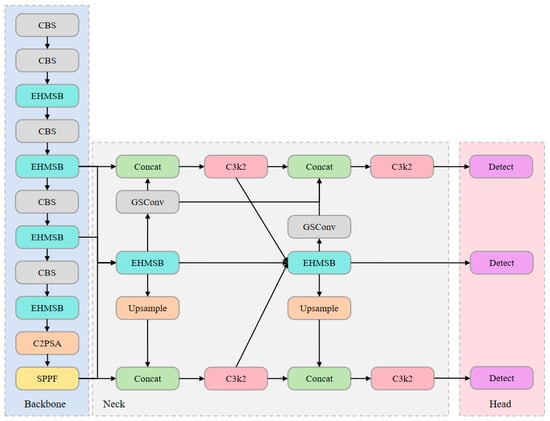

2.2. YOLO-PV

To further enhance YOLO11n’s representation capability and detection accuracy in lightweight object detection tasks, this work designs an improved model based on it. The overall architecture of the improved model is shown in Figure 2. While maintaining low computational cost, it significantly boosts detection performance, making it suitable for more complex object detection scenarios.

Figure 2.

YOLO-PV model network structure diagram.

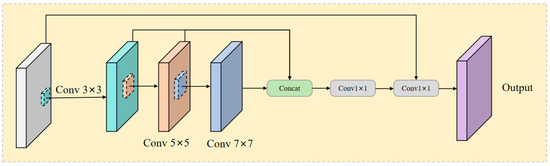

2.3. EHMSB

Defects in PV cells exhibit diverse spatial scales and morphological characteristics, which are often difficult to fully capture using a single convolutional kernel’s receptive field, thereby affecting detection accuracy [13]. To address this issue and extract features that capture both local details and global semantics, this work designs the EHMSB, as shown in Figure 3. The EHMSB module introduces a lightweight multi-scale feature aggregation structure that combines “channel splitting” with “layer-wise stacking” [14]. The module mainly consists of three sub-paths, which extract shallow, intermediate, and deep semantic features, respectively, and perform multi-scale fusion through channel-wise concatenation.

Figure 3.

The structure of the EHMSB module.

The design of the multi-path convolutional structure is as follows: The EHMSB module starts from the input feature map . The module first applies a 3 × 3 convolution to the input feature map to extract local edge information and texture features, forming the shallow-scale feature representation path.

Then, based on the shallow-scale path, a portion of the channels is fed into the mid-scale path of the EHMSB module, where a 5 × 5 depthwise separable convolution is stacked. This is designed to reduce the number of parameters and computational complexity while focusing on modeling the mid-scale receptive field.

Finally, in the large-scale path, the EHMSB module stacks a 7 × 7 grouped convolution to expand the receptive field and capture long-range contextual dependencies, while introducing a channel decoupling mechanism to reduce computational cost.

To integrate the multi-scale features generated by the three paths, the EHMSB module fuses the outputs of the shallow and medium-scale paths that are not subjected to further convolution with the output of the large-scale path through a channel concatenation operation, resulting in a combined feature map.

This operation merges semantic features with different receptive fields into a single tensor, forming a composite feature map with enriched spatial hierarchies.

To compress dimensions and enhance computational efficiency while avoiding information redundancy, EHMSB introduces a bottleneck structure composed of two sequential 1 × 1 convolutions. This structure performs linear dimensionality reduction and nonlinear activation, respectively, thereby progressively refining the feature representation:

To enhance feature consistency and maintain stable gradient propagation, EHMSB introduces a residual connection at the output end, where the input feature is added element-wise to the bottleneck output feature , producing the final module output.

This structure not only helps alleviate the gradient vanishing problem in deep networks but also accelerates convergence and improves stability while preserving the original feature information. Unlike standard residual modules, EHMSB integrates multi-scale representation capability outside the residual path, endowing it with both the stability of residual units and enhanced contextual modeling ability.

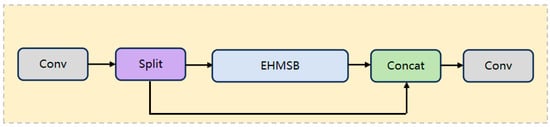

2.4. Light-EHMSB

To balance model performance and deployment efficiency, this paper further proposes a lightweight variant of the EHMSB module—Light-EHMSB, as shown in Figure 4—while retaining the multi-scale modeling advantages of the original design. The module is intended to preserve the essential multi-scale feature fusion mechanism without significantly increasing computational complexity, making it suitable for mobile devices or scenarios with higher requirements for inference speed.

Figure 4.

The structure of the Light-EHMSB module.

Light-EHMSB inherits the core idea of EHMSB in its overall structural design, namely constructing hybrid feature representations based on channel partitioning and multi-scale paths, but introduces structural simplifications in the information flow and convolution stacking strategy. Specifically, Light-EHMSB first applies a standard convolution to the input feature FFin to extract basic features and perform channel compression. The compressed feature map is then divided into two parts: one part is directly preserved as a shortcut connection, while the other part is fed into the EHMSB module for three-scale feature extraction and enhancement. The outputs of these two branches are concatenated along the channel dimension, followed by a 1 × 1 convolution to fuse features and restore the channel dimension, yielding the final output:

Compared with the standard EHMSB module, Light-EHMSB significantly reduces the depth of convolution stacking and path redundancy. By retaining the main channel’s direct shortcut path, it improves information flow efficiency while lowering both the number of parameters and FLOPs. In our experimental design, the original C3k2 module in the YOLO11n network was replaced with the Light-EHMSB module to achieve a significant enhancement in multi-scale feature representation while maintaining high inference speed and structural lightness. Experimental results demonstrate that this replacement strategy markedly improves the model’s adaptability to small targets and complex background scenarios without compromising detection accuracy, thereby validating the effectiveness and practical utility of the Light-EHMSB module.

2.5. ESMSAB

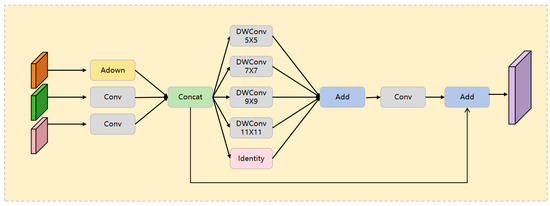

In small-object detection tasks, targets often exhibit varying sizes, complex structures, and blurred boundaries, issues that are especially pronounced in high-resolution photovoltaic cell images. Traditional feature fusion methods struggle to simultaneously preserve fine-grained information and expand contextual semantics in high-resolution images, limiting the accuracy and robustness of small-object recognition. To address this, this paper proposes an Enhanced Spatial Multi-Scale Attention Block (ESMSAB), as shown in Figure 5, designed to structurally optimize the feature fusion process and strengthen the representation of spatial context across multiple scales, thereby improving the detection accuracy of small targets [15].

Figure 5.

The structure of the ESMSAB module.

The core idea of the ESMSAB module lies in aligning and fusing heterogeneous-scale features through multi-branch paths. Upon entering the module, the input feature is first duplicated and fed into three separate branches. The left branch employs an Adown structure to perform spatial downsampling, whose primary function is to adjust the resolution of the input feature to match that of the other branches, ensuring dimensional compatibility for the subsequent concatenation operation while minimizing the loss of redundant information. In the design of the Adown path, the number of feature channels is kept maximal to prevent feature loss caused by incomplete information reconstruction during upsampling. Meanwhile, the two right branches use Conv to perform channel transformation and lightweight feature extraction, further reducing computational cost and enhancing semantic representation. The outputs of all three branches are then spatially aligned and fused at the Concat node.

To enhance the module’s ability to perceive targets of varying sizes, the features output from the Concat operation are fed into a multi-scale depthwise separable convolution branch network. Four depthwise convolution kernels with sizes of 5 × 5, 7 × 7, 9 × 9, and 11 × 11 are applied, and an identity mapping path (Identity) is added to construct cross-scale residual channels, preventing feature degradation.

The entire process can be formalized as follows: the input is first subjected to spatial alignment, generating :

Next, the aligned feature map is fed into the multi-scale convolution branches, where each branch employs depthwise separable convolutions composed of a depthwise convolution followed by a pointwise convolution to extract edge and contextual information at different receptive field scales. The outputs of the four branches are then combined via weighted fusion to produce the fused feature:

The weighted result is then passed through a 1 × 1 convolution for channel compression and nonlinear activation, producing the enhanced feature , which is subsequently fused with the initial input feature via a residual connection to form the final output:

In this expression, denotes the activation function, represents the weight matrix of the 1 × 1 convolution used for channel compression, and indicates the convolution operation.

In this module structure, the Identity path directly preserves the original input features by bypassing channel adjustment operations, thereby simplifying the module design, avoiding code redundancy, and enhancing feature consistency. The Adown path performs downsampling with the maximum number of channels and does not rely on upsampling-based reconstruction, effectively reducing the risk of information loss. The multi-scale branch structure significantly improves the module’s responsiveness to targets of varying sizes, demonstrating particular advantages in detecting blurred edges and densely packed small objects.

2.6. ESMSAB-FPN

In conventional Feature Pyramid Networks (FPNs), shallow features primarily emphasize spatial details, whereas deep features focus on semantic information. The insufficient interaction between these levels often results in missed detections of small objects and blurred boundaries. To effectively mitigate this limitation, this study proposes a novel FPN architecture that integrates dual Enhanced Spatial Multi-Scale Attention Block (ESMSAB) modules, thereby enabling more comprehensive fusion and complementarity between shallow details and deep semantic representations.

Specifically, in the process of multi-scale feature extraction, the proposed FPN introduces dual ESMSAB modules, which enhance the interaction of spatial and channel information through an adaptive attention mechanism. After being processed by the ESMSAB, shallow features preserve their spatial resolution and local details, while being fused with deep semantic features, ensuring that each scale contains both rich semantic information and complete spatial structures. An upsampling operation (Upsample) is employed to align the resolution of low-resolution features, whereas GSConv convolution is applied for channel integration and feature refinement, thereby preserving information integrity during the fusion process.

In the feature fusion stage, a Concat operation is adopted to concatenate features from different scales, achieving efficient multi-scale integration. Subsequently, consecutive C3k2 modules are utilized to further optimize feature representation, enhancing the model’s adaptability to object morphology and spatial distribution in complex scenarios. The multi-scale detection head is designed to ensure fine-grained prediction of objects at different scales, enabling collaborative detection of small, medium, and large targets. The overall architecture not only expands the receptive field and strengthens the capture of contextual information, but also ensures sufficient transmission of features across scales, leading to improved accuracy and robustness in object detection tasks.

In summary, by incorporating dual ESMSAB modules, the proposed FPN achieves deep interaction between shallow details and deep semantics. Combined with a multi-scale feature fusion strategy and a fine-grained detection head design, the network significantly enhances multi-scale detection capability while maintaining real-time performance, thereby providing an effective solution for small-object detection in complex scenarios.

3. Model Training and Result Analysis

3.1. Training Environment

To ensure the reproducibility and fairness of the experiments, as well as to provide an objective evaluation of the proposed improved algorithm under standardized conditions, all models were trained and inferred within the same physical hardware and computational environment. The detailed experimental settings and hardware configurations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Training Environment and Hyperparameters.

3.2. Datasets

The datasets used in this study include the PVEL-AD public dataset [16], which was jointly released by Hebei University of Technology and Beihang University. The PVEL-AD dataset is publicly available and has been widely used for photovoltaic cell defect detection research. It contains 12 types of PV cell defects with an image resolution of up to 1024 × 1024. Based on industrial inspection standards and defect distribution characteristics, seven representative defect categories were selected for this study, including crack, finger, black core, thick line, star crack, horizontal dislocation, and short circuit. A total of 4500 publicly available images were used for training and evaluation in the experiments.

To further validate the generalization ability of the model, we conducted additional experiments using the Steel Defect Dataset as a supplementary evaluation. This dataset contains defect images from different materials, and although it is primarily used for detecting steel defects, it helps assess the model’s adaptability to different defect types and background complexities. Through this, we aim to verify that the YOLO-PV model not only performs well in photovoltaic defect detection but also shows good performance in other industrial defect detection scenarios.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

In object detection tasks, the selection of evaluation metrics is crucial for comprehensively assessing model performance. In this study, precision (P), recall (R), and mean average precision (mAP) are primarily employed as the evaluation criteria.

P measures the accuracy of the predicted results and is calculated as follows:

Here, TP (True Positives) denotes the number of correctly detected instances, while FP (False Positives) denotes the number of instances incorrectly detected as targets. A higher precision indicates that the model can effectively reduce the false positive rate.

R reflects the model’s ability to detect true target instances and is calculated as follows:

Here, FN (False Negatives) denotes the true target instances that were not detected. A higher recall indicates that the model achieves more comprehensive coverage of the targets.

In multi-class detection tasks, the mean Average Precision (mAP) is further employed as an overall performance metric, which is defined as:

where denotes the total number of categories, and represents the average precision of the i-th category.

In the specific experiments, the commonly adopted evaluation metrics include mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95. The former refers to the mean Average Precision computed at an IoU threshold of 0.5, emphasizing the overlap accuracy between the predicted and ground-truth bounding boxes. The latter, in contrast, averages AP values across multiple IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05, thereby providing a stricter and more comprehensive assessment of localization accuracy and robustness. Consequently, mAP@0.5 is often employed for a quick comparison of the baseline detection capability of models, whereas mAP@0.5:0.95 is considered a more challenging and authoritative evaluation criterion [17].

3.4. Performance Evaluation and Result Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the detection performance of the proposed YOLO-PV model, a series of analyses were conducted from four aspects: training convergence, quantitative performance metrics, classification accuracy, and detection reliability.

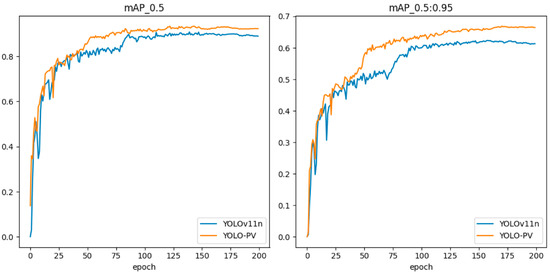

Figure 6 illustrates the training convergence curves of mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 for YOLO11n and YOLO-PV. As observed, YOLO-PV converges faster during the early training phase and exhibits smoother, more stable curves in the later epochs. It ultimately achieves higher accuracy on both metrics, demonstrating that the enhanced backbone and multi-scale fusion structure improve learning stability and optimization efficiency.

Figure 6.

Training convergence curves of mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 for YOLO11n and YOLO-PV.

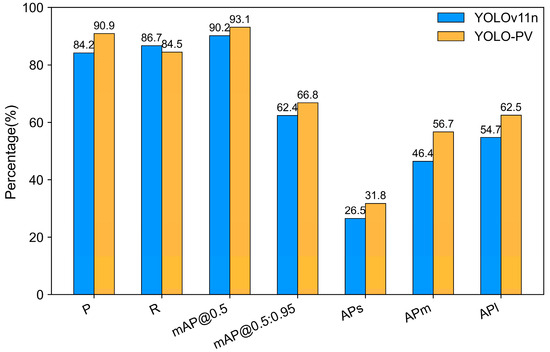

To quantitatively compare model performance, Figure 7 presents a bar chart of key evaluation metrics. YOLO-PV outperforms YOLO11n in Precision (P), Recall (R), mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95, with improvements of 6.7%, 2.2%, 2.9%, and 4.4%, respectively. Additionally, in multi-scale detection performance, YOLO-PV achieves AP_S = 31.8%, AP_M = 56.7%, and AP_L = 62.5%, indicating a stronger capability for identifying small and fine defects compared to the baseline model.

Figure 7.

Comparison of key performance metrics between YOLO11n and YOLO-PV.

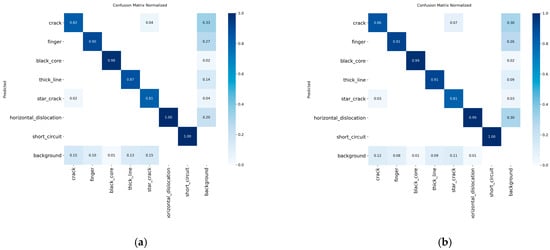

Figure 8 shows the confusion matrices for four representative defect types, including crack, finger, black core, and short circuit. The YOLO-PV model exhibits deeper diagonal regions and fewer off-diagonal errors, reflecting higher classification accuracy and localization precision. Particularly for samples with blurred boundaries or small defect areas, YOLO-PV maintains stable and consistent predictions, confirming its robustness against noise and complex textures.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix comparison between YOLO11n (a) and YOLO-PV (b) on the photovoltaic cell defect dataset.

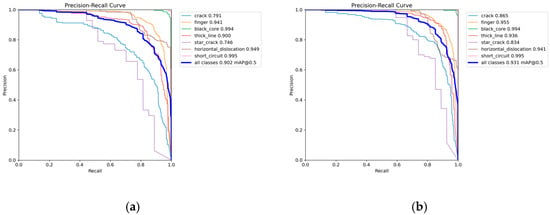

Furthermore, Figure 9 presents the Precision–Recall (PR) curves of YOLO11n and YOLO-PV. The YOLO-PV curve encloses a larger area and maintains higher precision even at high recall levels, suggesting a better balance between confidence and recall thresholds. Compared to YOLO11n, YOLO-PV demonstrates more stable detection behavior and reduced performance fluctuation, indicating improved reliability in practical detection scenarios.

Figure 9.

Precision–Recall Curves of YOLO11n (a) and YOLO-PV (b).

In summary, experimental results across multiple metrics confirm that YOLO-PV achieves faster convergence, higher detection accuracy, and stronger robustness in photovoltaic (PV) defect detection tasks, while its generalization capability is further evaluated on additional datasets in the following sections.

3.5. Comparative Experiments

To validate the superiority of the proposed YOLO-PV model over other state-of-the-art object detection frameworks, we conducted a series of comparative experiments. Representative detection algorithms were selected as benchmarks, and their performance was evaluated on the PVEL-AD dataset. The compared models include the two-stage detector Faster R-CNN [18], several mainstream one-stage detectors such as the lightweight YOLOv5n [19] and YOLOv6n [20], the next-generation real-time detector RT-DETR-L [21], the enhanced DEIM-D-FINE-L [15], and the recently proposed YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n, YOLO11n [22] and YOLOv12n [23].

As shown in Table 2, different detection algorithms exhibit clear differences in terms of accuracy and computational complexity. Faster R-CNN achieved a precision of 76.9% and recall of 70.3%, but its overall detection accuracy remained relatively low, with a parameter size as large as 136.87 M and extremely high floating-point operations, making it unsuitable for real-time applications. Lightweight models such as YOLOv5n and YOLOv6n required fewer parameters (2.53 M and 4.23 M, respectively) and had lower inference costs, but their detection accuracy was limited, with mAP@0.5 values of only 89.3% and 76.2%. RT-DETR-L demonstrated certain advantages in accuracy (mAP@0.5 of 87.2% and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 62.0%), yet its large model size (32.0 M parameters, 103.5 GFLOPs) hindered deployment in lightweight scenarios. DEIM-D-FINE-L achieved better performance–efficiency balance, with mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 90.0% and 61.9%, respectively, while maintaining moderate complexity (31.0 M parameters, 91.0 GFLOPs). The YOLOv9t and YOLOv10n models further improved efficiency and precision, achieving mAP@0.5 scores of 87.7% and 88.9%, and mAP@0.5:0.95 scores of 58.9% and 61.9%, with extremely low model sizes (1.97 M and 2.27 M) and FLOPs (7.6 and 6.5), supporting real-time detection speeds of 201 FPS and 300 FPS, respectively. YOLOv12n is an attention-centric version of the YOLO family that introduces lightweight transformer-based modules, including Area Attention and R-ELAN, to enhance feature extraction and detection stability. With 2.55 M parameters and 6.3 GFLOPs, it achieves a precision of 83.3%, recall of 86.2%, and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 60.9%, offering a good trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. YOLO11n struck a relatively good balance between accuracy and efficiency, achieving an mAP@0.5 of 90.2% and an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 62.4%, with a model complexity of only 6.3 GFLOPs.

Table 2.

Model parameter comparison.

In contrast, the proposed YOLO-PV model exhibited remarkable advantages across multiple evaluation metrics. While maintaining a lightweight architecture (2.52 M parameters and 7.5 GFLOPs), YOLO-PV achieved a precision of 90.9% and recall of 84.5%. Furthermore, its mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 reached 93.1% and 66.8%, respectively, both significantly higher than the compared models. These results demonstrate that YOLO-PV not only ensures efficient inference but also achieves superior detection accuracy, while its compact model size makes it suitable for deployment on hardware-constrained platforms, highlighting its practical application potential.

In addition to the overall mAP values, Table 3 presents the AP values for each defect category. A comparison reveals that YOLO-PV outperforms YOLO11n across all categories, particularly in small-scale defects and medium-scale defects.

Table 3.

Comparison of AP for Different Defect Categories between YOLO-PV and YOLO11n.

YOLO-PV shows significant improvements in AP values across various categories, with notable increases in Crack (from 79.1% to 86.5%), finger (from 94.1% to 95.5%), and star_crack (from 74.6% to 83.4%). These results indicate that YOLO-PV is more capable of detecting small and hard-to-detect defects, particularly in complex backgrounds and small object detection tasks.

To further evaluate the robustness of the YOLO-PV model in photovoltaic panel defect detection, we conducted an error rate experiment comparing YOLO11n and YOLO-PV. Table 4 presents a comparison of the two models in terms of detection error rate (Ecls), localization error rate (Eloc), total error rate (Eboth), and duplicate error rate (Edupe). The results indicate that YOLO-PV demonstrates significant improvements in all error rate metrics, particularly in Ecls and Eloc, with error rates decreasing by 0.32 and 1.3, respectively.

Table 4.

Multi-scale detection performance comparison of YOLO11n and YOLO-PV.

YOLO-PV’s improvement in Ecls and Eloc demonstrates its significant advantage in enhancing detection accuracy and reducing localization errors, especially in handling complex backgrounds and small defects.

In the proposed method, scale modeling and multi-scale feature interaction are among the key factors contributing to performance improvement. To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed model in detecting objects of different scales, we conducted a comparative analysis between the baseline model YOLO11n and the improved model in terms of detection accuracy on small, medium, and large objects. Table 5 summarizes the experimental results across different scales, where AP_S, AP_M, and AP_L represent the average precision for small, medium, and large objects, respectively.

Table 5.

Comparison of Multi-Scale Detection Performance (AP_S, AP_M, AP_L) between YOLO11n and YOLO-PV.

The detailed results are presented in Table 5 and the proposed YOLO-PV model consistently outperforms the baseline YOLO11n across different object scales. The improvement is particularly pronounced for small objects, where AP_S increases from 26.5% to 31.8%, representing a gain of 5.3 percentage points. This demonstrates that the proposed multi-scale modeling and feature interaction mechanism effectively alleviates the limitations of conventional models in detecting small defects, such as missed detections and inaccurate boundaries. For medium and large objects, YOLO-PV also achieves substantial improvements, with AP_M and AP_L increasing by 10.3 and 7.8 percentage points, respectively. These results indicate that the proposed method not only enhances fine-grained defect recognition but also improves robustness and accuracy in detecting large-scale structural defects. Overall, the findings validate the effectiveness and stability of the improved model in multi-scale scenarios, providing more reliable technical support for photovoltaic cell defect detection.

3.6. Ablation Study

To systematically evaluate the feasibility and necessity of each proposed component, an ablation study was conducted using YOLO11n as the baseline, with the results summarized in Table 6. Under identical experimental settings, different components were introduced incrementally and compared against the detection performance of the original model, thereby clearly revealing the individual contribution of each module to the overall performance. Furthermore, the combination of multiple modules was also examined to validate the synergistic effects of their integration on model performance.

Table 6.

Ablation Study of the YOLO-PV Model on the PVEL-AD Dataset.

On the PVEL-AD datasets, we evaluated each proposed improvement individually. The symbol “✔” in the table indicates the modifications introduced on top of the YOLO11n model. In addition to the three evaluation metrics (Precision, Recall, and mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95) presented in Section 3.3, we also considered the number of parameters (Param) and floating-point operations (FLOPs).

The experimental results show that replacing the C3K2 modules in the backbone of YOLO11n with the EHMSB module led to an increase of 1.5% in both mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95. Further, replacing the original feature pyramid network (FPN) in YOLO11n with the newly designed dual-ESMSAB-enhanced FPN resulted in improvements of 2.6% and 3.1% in mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95, respectively. Finally, integrating both the EHMSB and the new FPN into YOLO11n yielded further performance gains, with mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 increasing by 2.9% and 4.4%, respectively.

For YOLO-PV, we reported the results as mean ± standard deviation. Specifically, the mAP@0.5 achieved 93.1% ± 0.14, and mAP@0.5:0.95 reached 66.8% ± 0.15. These improvements of 2.9% and 4.4% over YOLO11n reflect the stability and reliability of the model’s performance across multiple runs. Additionally, YOLO-PV demonstrates excellent FPS performance (320 FPS), ensuring its suitability for real-time detection applications.

These results highlight that YOLO-PV significantly improves detection accuracy, especially in small object and complex background detection tasks, while maintaining real-time performance and a low computational burden, as evidenced by the consistent and reliable experimental data.

3.7. Detection Results and Visualization Analysis

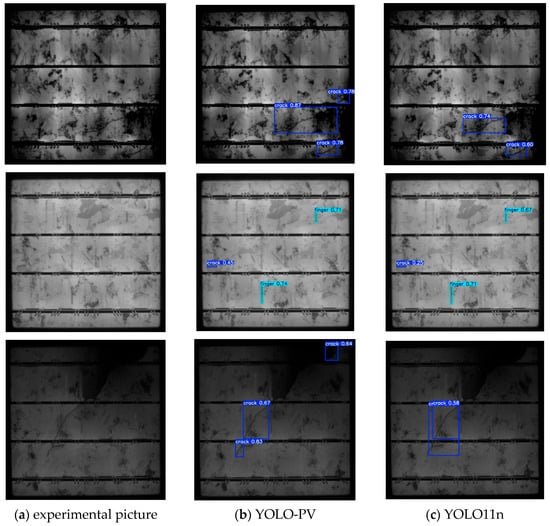

To intuitively demonstrate the performance of the proposed YOLO-PV model in photovoltaic (PV) cell defect detection, representative test samples were selected for visual comparison, as shown in Figure 10. The upper row presents the detection results of the improved YOLO-PV model, while the lower row displays those of the baseline YOLO11n. It can be observed that YOLOv11n suffers from missed detections and inaccurate localization in certain samples, particularly under challenging conditions such as blurred crack edges or strong background noise. In contrast, the YOLO-PV model achieves more precise localization of defect regions and exhibits higher robustness and stability in identifying subtle defects such as micro-cracks and finger-like cracks. These qualitative observations are consistent with the improvements in quantitative metrics (e.g., mAP and error rates), further validating the effectiveness and practicality of the proposed method.

Figure 10.

Visualized detection results of different defect types and models on the PVEL-AD dataset. Columns (a–c) represent the experimental image, YOLO-PV, and YOLO11n, respectively. Row 1 shows the detection of crack defects, Row 2 shows the detection of finger defects, and Row 3 shows additional examples of crack detection under varying visual conditions.

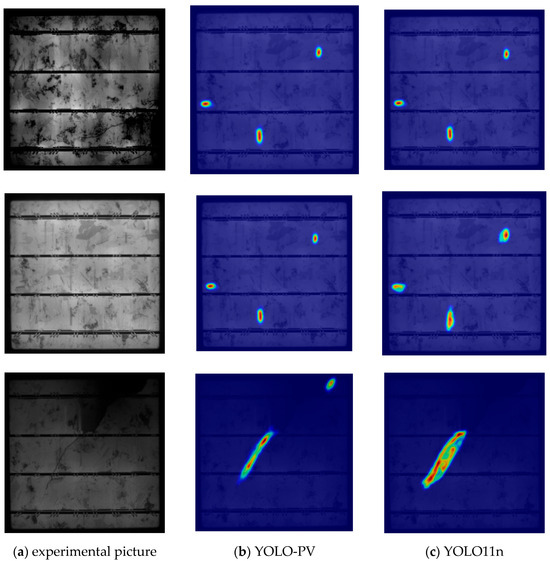

To further interpret the model’s decision-making process, Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) was employed to visualize the feature activation regions, as illustrated in Figure 11. The Grad-CAM heatmaps provide intuitive insight into where the model focuses when identifying defects. The YOLO-PV model demonstrates concentrated attention on the actual defect areas (e.g., crack lines and black-core boundaries), whereas YOLO11n exhibits more scattered responses with attention partially focused on irrelevant background regions. This indicates that the improved architecture enables the model to capture more discriminative and semantically relevant features, enhancing both feature representation and interpretability.

Figure 11.

Comparison of Grad-CAM visualization results between YOLO-PV and YOLO-11n on the PVEL-AD dataset. Columns (a–c) represent the experimental image, YOLO-PV, and YOLO11n, respectively. Each row shows the Grad-CAM activation maps corresponding to different photovoltaic defect samples, illustrating the model’s attention and interpretability performance.

Overall, the visual detection and Grad-CAM analyses confirm that YOLO-PV not only achieves higher quantitative accuracy but also provides better visual interpretability. The model effectively focuses on physically meaningful defect regions under complex illumination and noise conditions, offering a reliable foundation for automated PV module inspection.

3.8. Generalization of the Proposed Method Across Different Detection Frameworks

To further verify the universality and scalability of the proposed method, it was embedded into several representative object detection frameworks, including YOLOv5n, RT-DETR-L, and YOLOv10n, forming the corresponding improved versions YOLOv5n-PV, RT-DETR-L-PV, and YOLOv10n-PV. The experimental results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Performance comparison after applying the proposed method to different detection frameworks.

As shown, integrating the proposed method consistently enhanced the detection performance across all models, which demonstrates the effectiveness and generalization capability of the approach. Specifically, YOLOv5n-PV achieved an mAP@0.5 of 92.5% and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 64.7%, showing improvements of +3.2% and +4.0% compared to the original YOLOv5n, while also reducing the model parameters and computational cost (from 2.51 M/7.1 GFLOPs to 2.11M/5.5 GFLOPs). Similarly, RT-DETR-L-PV achieved mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 values of 89.5% and 63.7%, improving by +2.3% and +1.7%, respectively, with a moderate reduction in computational complexity (from 103.5 GFLOPs to 40.5 GFLOPs). In addition, YOLOv10n-PV reached mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 values of 92.9% and 63.8%, with increases of +4.0% and +1.9%, while maintaining lightweight complexity (2.07 M parameters, 6.5 GFLOPs).

These results indicate that the proposed method can be flexibly integrated into different mainstream object detection architectures, yielding significant improvements in both accuracy and efficiency. This confirms that the proposed method possesses strong portability, scalability, and generalization potential, making it a promising enhancement approach for future lightweight detection research.

3.9. Generalization Ability Validation: Experimental Results on Steel Defect Dataset

To verify the generalization capability and robustness of the proposed YOLO-PV model under different data distributions, additional experiments were conducted on the Steel Defect Dataset. This dataset differs significantly from the photovoltaic (PV) cell defect dataset in material texture, background complexity, and defect distribution, making it suitable for evaluating the model’s cross-domain stability and adaptability. The experiments include ablation studies, multi-scale detection tests, and error rate analysis.

In the ablation study, the effects of the enhanced backbone and the feature pyramid network (FPN) were examined individually and in combination. The results are summarized in Table 8. It can be observed that using either module alone improves performance to some extent, but the combination of both yields the best results, with mAP@0.5 reaching 82.1% and mAP@0.5:0.95 increasing to 49.7%. Meanwhile, the model remains lightweight (2.52 M parameters) and maintains real-time speed (320 FPS). These results confirm that the proposed modules complement each other and jointly enhance the model’s feature extraction and multi-scale representation capabilities.

Table 8.

Ablation Study of YOLO-PV on the Steel Defect Dataset.

Next, the multi-scale detection experiments were conducted to investigate the model’s performance at different object sizes. As shown in Table 9, YOLO-PV maintains stable detection performance across small, medium, and large targets. The improvement is most pronounced for small-scale defects (e.g., micro-cracks), where the AP_S reaches 56.9%, representing a 23.7% increase over the version without the multi-scale fusion strategy. This demonstrates the model’s effectiveness in handling size variations through high-resolution feature integration.

Table 9.

Multi-Scale Detection Accuracy of YOLO-PV versus YOLO11n on the Steel Defect Dataset.

Finally, to evaluate the model’s cross-domain generalization ability, an error rate experiment was conducted using a public steel defect dataset. This dataset differs from PV cell images in texture patterns, defect distribution, and background complexity, providing a strong test for the model’s robustness. As shown in Table 10, YOLO-PV achieves notably lower Ecls (0.01) and Eloc (8.50), indicating improved stability and precision even under domain shifts. These results demonstrate that the proposed improvements not only enhance PV defect detection but also provide good adaptability to other industrial defect scenarios.

Table 10.

Error Rate Comparison between YOLO-PV and YOLO11n on the Steel Defect Dataset.

In summary, YOLO-PV achieves outstanding performance across all experiments. The ablation study validates the rationality of the proposed modules, the multi-scale experiments highlight the model’s advantage in small-target detection, and the cross-dataset error rate analysis confirms its strong generalization and robustness. These findings demonstrate that YOLO-PV is not only effective for photovoltaic defect detection but also adaptable to broader industrial visual inspection tasks.

4. Conclusions

This study addresses the challenges in photovoltaic (PV) cell defect detection, including large scale variations, complex textures, and strong background interference, by proposing a lightweight detection model, YOLO-PV, based on an improved YOLO11n architecture. By integrating the Enhanced Hierarchical Multi-Scale Bottleneck (EHMSB), the Enhanced Spatial Multi-Scale Attention Block (ESMSAB), and the dual-path adaptive multi-scale fusion structure (ESMSAB-FPN), the proposed model effectively strengthens feature representation and multi-scale perception while maintaining a compact network design. Experimental results on the PVEL-AD public dataset demonstrate that YOLO-PV achieves improvements of 2.9% and 4.4% in mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95, respectively, compared to the baseline YOLO11n, without increasing model complexity or computational cost. This enables the model to accurately recognize challenging defects such as micro-cracks, black cores, and finger-like anomalies.

The ablation studies and visualization analyses further confirm the effectiveness and necessity of each proposed module. Specifically, the EHMSB enhances hierarchical multi-scale feature extraction, allowing the model to capture subtle local details while preserving semantic consistency. The ESMSAB improves spatial perception across different object scales, and the ESMSAB-FPN strengthens the fusion of high- and low-level features, ensuring robust performance under complex textured backgrounds. Confusion matrix and PR curve analyses indicate that YOLO-PV exhibits better class separability and reduced false detection rates, while Grad-CAM visualizations show that the model focuses more precisely on true defect regions. These findings verify that the designed modules not only enhance detection accuracy but also improve interpretability and robustness.

Furthermore, cross-domain validation using a public steel surface defect dataset demonstrates that YOLO-PV maintains high accuracy and low error rates even when applied to materials and defect types with different textures and feature distributions. This result confirms that the proposed feature extraction and fusion strategies have strong generalization capability, making YOLO-PV adaptable to broader industrial inspection scenarios.

Overall, YOLO-PV achieves a favorable balance between accuracy, robustness, and real-time performance, showing strong potential for practical engineering applications such as online inspection and intelligent maintenance in PV power plants. Future work will focus on further model lightweighting and efficient deployment, incorporating multimodal information to improve fine defect recognition, and exploring few-shot and weakly supervised learning methods to enhance generalization and adaptability in real-world industrial environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.C.; Methodology, H.L. and W.C.; Software, W.C.; Validation, W.C.; Investigation, W.C.; Data curation, H.L.; Writing—original draft, W.C.; Writing—review and editing, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ebied, M.A.; Munshi, A.; Alhuzali, S.A.; El-Sotouhy, M.M.; Shehta, A.I.; Elborlsy, M.S. Advanced deep learning modeling to enhance detection of defective photovoltaic cells in electroluminescence images. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Prado Santamaría, R.; Dhimish, M.; dos Reis Benatto, G.A.; Kari, T.; Poulsen, P.B.; Spataru, S.V. From Indoor to Daylight Electroluminescence Imaging for PV Module Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Review of Techniques, Challenges, and AI-Driven Advancements. Micromachines 2025, 16, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazen, F.M.A.; Seoud, R.A.A.; Shaker, Y.O. Deep learning for automatic defect detection in PV modules using electroluminescence images. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 57783–57795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Rawat, Y.; Vyas, S. Advancing automatic photovoltaic defect detection using semi-supervised semantic segmentation of electroluminescence images. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160, 111790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Wei, H.; Zhang, K. A lightweight network for photovoltaic cell defect detection in EL images based on NAS and knowledge distillation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.07455. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, T. GBH YOLOv5: Photovoltaic Panel Defect Detection with Ghost Conv and Tiny Target Prediction Head. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.00886. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahremani, A.; Adams, S.D.; Norton, M.; Khoo, S.Y.; Kouzani, A.Z. Detecting Defects in Solar Panels Using the YOLO v10 and v11 Algorithms. Electronics 2025, 14, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Han, J.; Lian, J.; Qi, Y. Photovoltaic defect detection based on improved YOLOv5 algorithm. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Xiao, S.P. Research on surface defect detection of solar cell with improved YOLOv5 algorithm. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 368–375. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Yang, J.; Luo, P. Efficient Attention Mechanisms for Lightweight Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–11 October 2023; pp. 4451–4463. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. Ghostnet: More features from cheap operations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 1580–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, R.; Wu, Y. IoU-Aware Object Detection for Real-Time Systems. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2022, 158, 140–147. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, X. Local multi-scale feature aggregation network for real-time image dehazing. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 141, 109599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, C.; Li, L.; Wang, R.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Z. Lightweight tunnel obstacle detection based on improved YOLOv5. Sensors 2024, 24, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Li, L.; Zang, J.; Xu, Q.; Xu, X.; Dong, Y.; Fu, K. A photovoltaic cell defect detection model capable of topological knowledge extraction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, B.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, H. PVEL-AD: A large-scale open-world dataset for photovoltaic cell anomaly detection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2022, 19, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.S.; Hsieh, C.C.; Liao, T.W.; Huang, C.-Y.; Kuo, C.-F.J. Deep learning-based automatic defect detection of photovoltaic modules in infrared, electroluminescence, and red–green–blue images. Energy Convers. Manage 2025, 332, 119783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobek, J.; Medina Inojosa, J.R.; Medina Inojosa, B.J.; Rassoulinejad-Mousavi, S.M.; Conte, G.M.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Erickson, B.J. Medyolo: A medical image object detection framework. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2024, 37, 3208–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. RT-DETR: Real-time DEtection TRansformer. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.08069. [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota, R.; Meng, Z.; Churuvija, M.; Du, X.; Ma, Z.; Karkee, M. Comprehensive performance evaluation of YOLO11, YOLOv10, YOLOv9 and YOLOv8 on detecting and counting fruitlet in complex orchard environments. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.12040. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.-Y.M. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).