Abstract

This study addresses the load frequency control (LFC) within a multiarea power system characterized by diverse generation sources across three distinct power system areas. area 1 comprises thermal, geothermal, and electric vehicle (EV) generation with superconducting magnetic energy storage (SMES) support; area 2 encompasses thermal and EV generation; and area 3 includes hydro, gas, and EV generation. The objective is to minimize the area control error (ACE) under various scenarios, including parameter variations and random load changes, using different control strategies: proportional-integral-derivative (PID), two-degree-of-freedom PID (PID-2DF), fractional-order PID (FOPID), fractional-order integral (FOPID-FOI), and fractional-order integral and derivative (FOPID-FOID) controllers. The result analysis under various conditions (normal, random, and parameter variations) evidences the superior performance of the FOPID-FOID control scheme over the others in terms of time-domain specifications like oscillations and settling time. The FOPID-FOID control scheme provides advantages like adaptability/flexibility to system parameter changes and better response time for the current power system. This research is novel because it shows that the FOPID-FOID is an excellent control scheme that can integrate these diverse/renewable sources with modern systems.

1. Introduction

Load frequency control (LFC) is an important part of a power system to maintain the balance between supply and load demand by keeping continuous track of generation and demand.

1.1. Research Background

Load frequency control (LFC) maintains the supply and demand in power systems to ensure stable system frequency and reliable delivery. LFC plays a vital role in compensating for deviations in load/generation. The world is demanding more clean energy; therefore, renewable energy sources (RESs) have become more important to incorporate into power systems. RESs, i.e., solar and wind, lead to inconsistency and uncertainties due to their intermittent nature. Integrating RES in multiarea power systems consisting of conventional sources (thermal, hydro), electric vehicles, and energy storage leads to challenges for the task of LFC. Therefore, these modern challenges require more advanced control schemes that can manage the frequency and power exchange of interconnected power systems. To handle these issues, control techniques have changed from PID controllers to more sophisticated methods, including fractional-order controllers.

1.2. Literature Review

Since electric energy cannot be stored, LFC adjusts both the supply and demand in order to provide reliable power to consumers [1,2]. LFC works as a control scheme that keeps the system frequency within specified limits by regulating the generator’s output in response to load changes to restore balance. LFC’s main aim is to minimize (reduce) frequency deviations by instantly adjusting the generator output as per load requirements [3]. Additionally, LFC is used to keep tie-line power in limits by regulating the power flow between areas to keep a power system in balance. To achieve this, LFC requires a controller. In the literature, several control schemes have been reported. Some of the most well-liked schemes are conventional (PID), robust, modern, and intelligent ones [4]. As a whole, it can be concluded that LFC is essential for maintaining the stability of a power system. Furthermore, to guarantee the reliable supply of electricity, nowadays, the integration of renewable energy sources (RESs) is in demand, which makes LFC’s role more crucial due to the changes in dynamic loads and generation uncertainties [5]. Since the controller is like the brain of the LFC scheme, it must be used efficiently (utilizing a control algorithm) to regulate the generator response [6]. The PID control scheme is a widely used scheme in LFC because of its simplicity and effectiveness and provides generator outputs to maintain system frequency within limits [7]. It also faces challenges in the implementation of control strategies in modern systems. Authors [8] suggested PID tuning using metaheuristic optimization algorithms and demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed approach. A study [9] investigated the use of fractional-order PID controllers for robust load frequency control in multiarea power systems. It conducted a theoretical analysis, with simulation results highlighting the advantages of fractional-order control in enhancing system stability and performance. In [10], an adaptive LFC scheme for power systems with high RES integration using PID neural networks was proposed. The results evidenced that the proposed control scheme is effective in minimizing the deviations in frequency. In [11], the impact of communication delays/dropout was reported with PID controllers. Furthermore, in [12], a PID-fuzzy logic controller in deregulated LFC was proposed to achieve improved time-domain specifications. Though PID is a good control scheme, it suffers from lagging behavior in nonlinear systems and large settling times; therefore, researchers are looking for alternate control schemes like the PID-2DF controller, which outperforms PID and provides more reliable/accurate control, as given in [13]. It is seen that PID-2DF can dampen system frequency effectively. In [14], an optimal tuning for multiarea PID-2DF is presented so that the system can be settled more accurately. A robust fractional-order PID-2DF is proposed in [15]. It is seen that fractional-order techniques can improve robustness than PID controllers. Authors of [10], also proposed a PID-2DF neural controller for the RES-LFC scheme in [16], and it was found that this control scheme can control a system with high stability and reliability. LFC using communication delays employing PID-2DF controllers is reported in [17]. It shows that PID-2DF compensate communication constraints, and maintain stability. A PID-2DF controller in decentralized LFC scheme in deregulated scenario is reported in [18], to enables and ensure robust frequency regulation. Later, fractional calculus opened a new window in controller’s design. The FOPID (Fractional-order PID) controller proposals improved flexibility and accuracy over PID by using fractional-orders integral-derivative. A two-area interconnected system with various RESs + hydrogen energy storage using FOPID controller is given in [19]. The optimal parameters have been obtained using gradient-based optimizer (IGBO) techniques in order to provide the frequency stabilization. A multiarea–multisource power system utilizing improved gravitational search algorithm binary particle swarm optimization (IGSA-BPSO) optimized FOPID is given in [20], which reported the robustness dynamics of the used control scheme for various load scenarios. A cascaded fractional controller having a 3DOF-FOPID and FOPI is presented in [21]. The controller performance was checked for LFC utilizing doubly fed induction generators. In [22], a [FOPID/(1 + PI)] controller utilizing the equilibrium optimizer (EO) algorithm was reported for the LFC of interconnected microgrids. Ref. [23] reported a fractional-order multistage controller for interconnected microgrids to determine exploitation and exploration competencies. In [24], a 3DOF-FOPID utilizing mountain gazelle optimization (MGO) was applied in low-inertia microgrids to enhance stability under fluctuating conditions. In the literature, other variants of the FOPID control scheme are also available in order to improve the performance of the FO system. Ref. [25] reported a FOPID controller for an automatic generation control (AGC) scheme utilizing the big bang-big crunch algorithm. It is seen that this approach can provide resilience against load variations and random fluctuations. A 1 + PD/FOPID controller utilizing the moth flame optimization (MRFO) technique was given in [26]. It achieved better performance and reduces frequency deviations with shorter settling times as compared to the PID, FOPID, and PD/FOPID control schemes. An adaptive model predictive FOPID controller was investigated in [27], which makes the power system more stable against load variations. A FOPID control scheme utilizing various optimization algorithms was reported in [28]; the scheme was employed in renewable energy systems to optimize frequency regulation and system stability. Ref. [29] reported the application of FOPID controllers in hybrid (thermal, hydro, and EV) systems including RESs and showed better performance against perturbations. Ref. [30] reported an LFC scheme incorporating a microgrid, and EVs were used in order to check the performance of the PID-2DF controller.

The optimization algorithm plays an important role in obtaining the parameters of a control scheme. In the literature, many algorithms have been reported. In Ref. [31] algorithms like firefly (FA), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and gravitational search (GSA) have been used to obtain the parameters in order to improve the LFC. In [32], PSO- and GA-based H-infinity LFC schemes are reported. Similarly, in [33], various optimization techniques to address LFC issues in deregulated hybrid systems were reported. A new technique known as JAYA was utilized in adaptive LFC for thermal, PV, and wind systems [34]. An LFC scheme for a two-area multisource system utilizing a GA-PSO control structure was presented in [35]. Ref. [36] investigated a hybrid PSO and gravitational search (GSA) model to improve the LFC scheme in hybrid power systems, which consisted of electric vehicles, achieving an improvement in convergence speed, leading to better stability. An LFC scheme utilizing GA to improve the response and stability of a deregulated power system integrating electric vehicles was given in [37]. An LFC scheme consisting of JAYA optimization for interconnected RES with EVs to provide less complexity, increased robustness, and better frequency under diverse conditions was given in [38]. A big bang-big crunch (BBBC)-based adaptive LFC scheme to improve frequency regulation in multiarea power systems with EVs was reported in [39]. The results show that the designed control scheme performed better in settling the deviations quickly.

A variety of optimization methods and advanced control schemes have been studied recently, with the aim of enhancing the efficiency of power systems integrating RESs. These studies have achieved considerable improvements in system efficiency and stability under various operational scenarios. The use of innovative control methods for energy management in hybrid energy systems was reported in [40]. The global transition to renewable energy sources has been further pushed by international climate agreements and carbon emission reduction programs. The COP26 summit was essential in establishing challenging goals for the clean energy transition in order to encourage sustainable energy practices around the world. These commitments are essential for driving development in renewable energy technologies and incorporating them into modern power systems [41,42,43].

1.3. State-of-the-Art Research

Previous studies have demonstrated that because of their simplicity and ease of use, PID controllers are suitable for load frequency control (LFC) tasks in conventional power systems. However, nonlinearities, parameter variations, load fluctuations, intermittency, and variability are the common limitations of these controllers. To overcome these limitations, PID-2DF controllers have been employed for LFC, allowing independent tuning for set point tracking and disturbance rejection, which enhances system performance under dynamic scenarios. However, the performance of these controllers is not effective in scenarios with substantial communication delays and complex system dynamics. Since fractional calculus enables more flexible tuning, controllers like fractional-order PID (FOPID) offer improved adaptation to nonlinear behaviors and parameter uncertainty.

Further developments in fractional-order controllers like FOPID-FOI and FOPID-FOID offer enhanced robustness, superior oscillation suppression, and faster settling times. The current study addresses gaps in the existing research, particularly the integration of superconducting magnetic energy storage (SMES) and thyristor-controlled phase shifters (TCPSs) in LFC schemes. This study also distinguishes itself by employing the JAYA optimization algorithm, which provides better computational efficiency and robustness compared to conventional techniques. The comparative analysis under various conditions, including step load changes, parameter variations, and random load, offers important insights into the best LFC strategies for hybrid power systems with renewable energy integration.

1.4. Motivation, Novelty (Innovation), and Contributions of the Current Study

The decision regarding which controller to use for a specific LFC scheme is never easy. Selecting the appropriate controller becomes more challenging when RESs are integrated with a conventional power system. As a result, one must select the controller that offers the best performance. PID control has long been the best scheme that provides a simple and effective solution. However, as systems became complex, nonlinear, and dynamic, other techniques, such as PID with two degrees of freedom (PID-2DF), FOPID, and its variations, have drawn attention.

This study distinguishes itself by exploring the application of PID, PID-2DF, and FOPID and variants of FOPID control schemes in a multiarea power system configuration that includes diverse energy sources:

- area 1: Thermal, geothermal (GTP), and EVs.

- area 2: Thermal and EVs.

- area 3: Hydro, gas, and EVs.

Tie lines are used to connect each area. The novelty lies in integrating thyristor-controlled phase shifters (TCPSs) and superconducting magnetic energy storage (SMES), which have not been frequently considered together in LFC studies. To determine the best control parameters, this study used the JAYA algorithm focusing on step load changes, parameter variations, and random load disturbances.

The novelties include the following:

- A comparative analysis of different control schemes (PID, PID-2DF, FOPID, FOPID-FOI, FOPID-FOID) under various scenarios, including high RES integration and diverse generation sources, demonstrates the advantages of advanced control strategies in complex power systems.

- The use of JAYA optimization for tuning shows better computational efficiency and robustness compared to conventional methods.

- System oscillation (overshoot/undershoot) is evaluated and settling time is reduced, providing insights into the most effective control method for dynamic system conditions.

1.5. Paper Structure

- Section 2: Modeling of the power system and control schemes.

- Section 3: Different controller structures.

- Section 4: Optimization algorithm used for tuning controller parameters.

- Section 5: Simulation results and discussion.

- Section 6: Conclusions and future research directions.

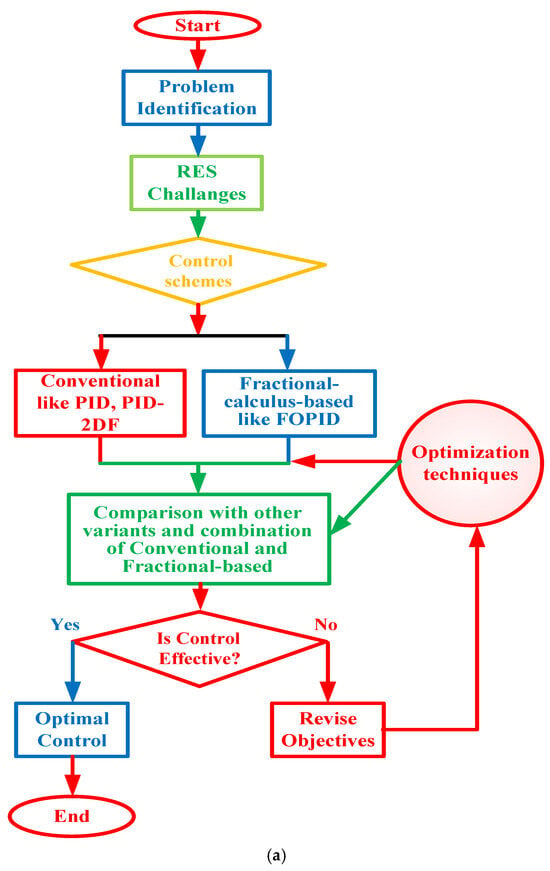

The diagram shown in Figure 1a depicts the research structure carried out in this study. A comparative study of all the references in terms of optimization techniques, applications, limitations, and highlights of the work reported is given in Table 1.

Figure 1.

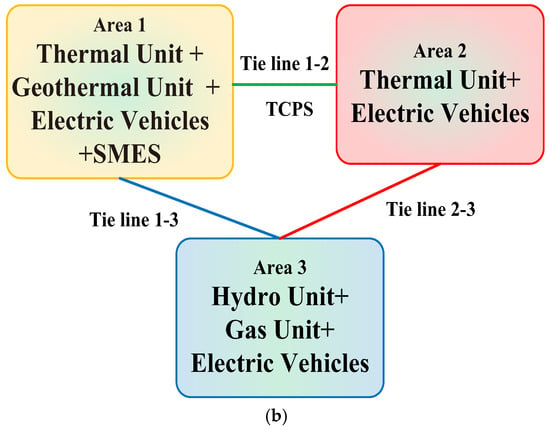

(a) Research flowchart. (b) An overall diagram of the three areas of power studied.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of control strategies for power systems: optimization techniques, applications, limitations, and highlights of this work.

2. Modeling of Power System Elements

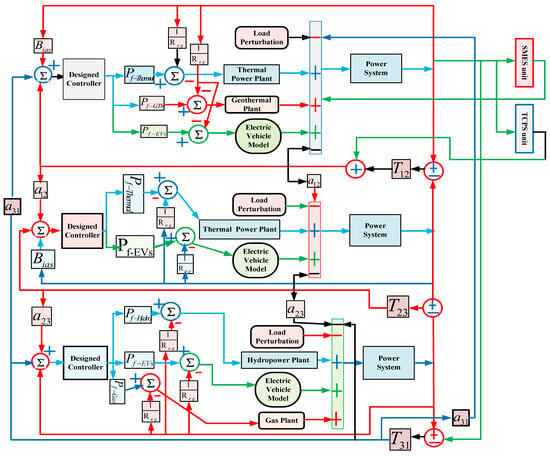

Figure 1b shows a general schematic of the interconnected electrical power system utilizing tie lines. The description of the figure is as follows: thermal, EV, and geo and SMES (area 1); thermal and EV (area 2); and hydro, gas, and EV generation (area 3). Tie lines (1–2) have TCPS support. To keep the balance between load and generation among all three areas, different control schemes were designed and compared in this study.

Below are the main points used in this study:

- -

- Experimental (Simulation) Design

- System configuration:

- area 1: Thermal, geothermal, and electric vehicle (EV) generation with superconducting magnetic energy storage (SMES).

- area 2: Thermal and EV generation.

- area 3: Hydro, gas, and EV generation.

- -

- Simulation Platform: MATLAB/Simulink, R2023b.

- -

- Testing Cases:

- Normal conditions with step load changes.

- Parameter variations, i.e., change in system parameters.

- Random load disturbances.

- -

- Performance metrics included settling time, overshoot, undershoot, frequency deviations, area control error (ACE), and tie-line power deviations.

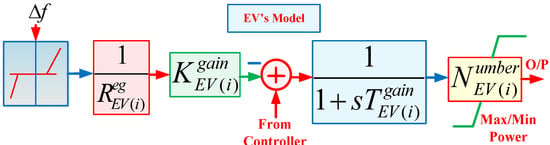

2.1. EV Modeling

Electric vehicles (EVs) play a crucial role in load frequency control (LFC) by acting as both dynamic loads and distributed storage resources. EVs can respond to frequency deviations by modulating their charging and discharging rates, thereby providing a rapid and flexible means of balancing supply and demand fluctuations in the power grid. This capability enhances the stability and reliability of power systems, especially those integrating variable renewable energy sources. A precise dynamic model of an electric vehicle (EV) is shown in Figure 2, and its comprehensive electrical equivalent circuit is shown in [36,37,38,39].

Figure 2.

Modeling of EV LFC studies.

Figure 2 shows an EV that comprises a battery charger, a primary, and LFC in order to transfer power between the battery and power system. A dead band (+/−10 Mhz) is incorporated to prevent the undesirable cut-off of EVs from the grid.

The droop coefficient (Rev) = 2.4 Hz/pu MW. The values of Kgev (EV gain) and Tgev (time constant of the battery) are given in Appendix A. The max./min. power of the EV is determined as

where represents the number of electric vehicles. In this study, 500 EVs were considered in area 1, 1000 in area 2, and 1500 in area 3. The charging and discharging capacity of an EV was considered within ±5 kW.

2.2. Modeling of Various Generating Systems

The block diagram was generated of the simulated test system comprising various power generation sources (thermal, geothermal, and EV (area 1), thermal and EV (area 2), hydro, gas, EV (area 3) and load demand modules, along with the models of SMES and TCPS. In this section, a brief over of the above-mentioned models is given.

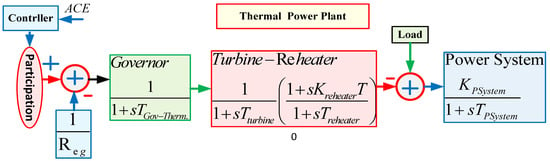

2.2.1. Thermal Power Model

Thermal power systems have been in service for energy generation for a very long time and, still, they are suitable. In fact, they are providing the maximum share in power production. Figure 3 shows the transfer function model of a reheat thermal power system, where Kreheater is the reheat system gain, and Reg represents droop control. TGov-Therm., Tturbine, and Treheater are the time constants of the governor, turbine, and reheat system, respectively.

Figure 3.

The transfer function of reheat thermal plant model.

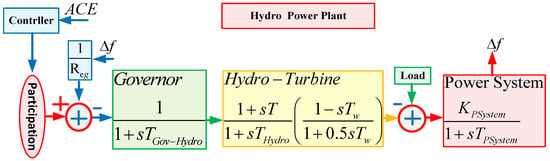

2.2.2. Hydro Power Model

After thermal, hydropower systems are the second most important for generating electricity. The transfer function model of a hydropower system is given in Figure 4, where THydro is the transient droop time constant, T is the reset time constant, TGov-Hydro is the governor time constant, and Tw represents water starting time.

Figure 4.

The transfer function of the hydropower plant model.

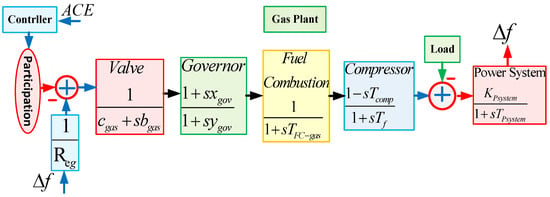

2.2.3. Gas Power Model

Figure 5 represents a gas power generator, where cgas represents valve position, bgas is the valve positioner constant, xgov/ygov represents the speed governor lead-lag time constant, and TFC-gas, Tcomp, and Tf represent compressor discharge volume, combustion reaction time delay, and fuel time constant, respectively.

Figure 5.

The transfer function of the G=gas plant model.

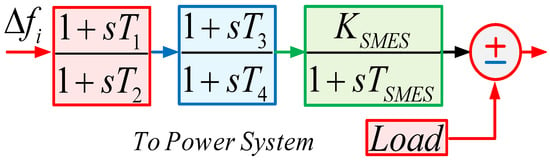

2.2.4. Super Magnetic Energy Storage Device (SMES) Model

SMES is used to inject/receive the power to/from the power system in order to minimize deviations. Figure 6 shows that the SMES model consists of lead time constants (T1–T4), KSMES (gain), and TSMES (time constant).

Figure 6.

The transfer function of the SMES model.

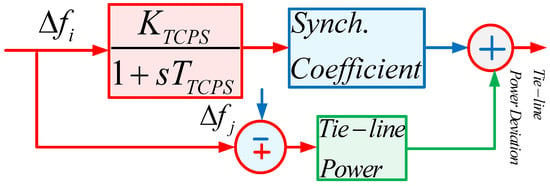

2.2.5. Thyristor-Controlled Phase Shifter (TCPS) Model

A TCPS is used to dampen the power fluctuations and increase the power transfer capabilities of the line utilizing changing the phase angle. Figure 7 presents a model of TCPS, placed near area 1 and connected to the ΔPtie12 tie line in series, where TTCPS is the time constant of the TCPS.

Figure 7.

The transfer function of the TCPS model.

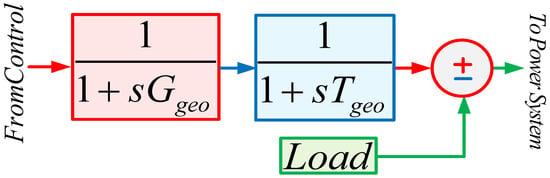

2.2.6. Geothermal Plant (GTP) Model

The GTP model is given in Figure 8. The geothermal plant is used to produce electricity and falls in the RES category. The power produced is almost similar to that of the thermal stations, but it does not have a boiler. Here, Tgeo-t is the governor, and Ts-geo is the turbine time constant of the GTP.

Figure 8.

The transfer function of the GTP model.

The overall diagram of the interconnected test system is given in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Block diagram of the tested interconnected three-area power system.

3. The Control Scheme

The controller is known as the brain of an LFC scheme. Many control schemes have been tried in LFC schemes so far, i.e., from conventional to modern ones. Each control scheme has its own merits and limitations. In this study, PID, PID-2DF, FOPID, FOPID-FOI, and FOPID-FOID controllers were constructed and tested for the system given in this article.

In this section, different control schemes, their mathematical models, and the algorithm used to obtain their parameters are studied. Let us start with the basic one, i.e., the PID control scheme.

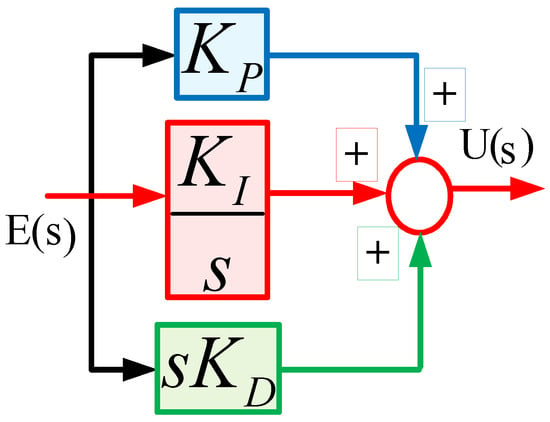

PID control scheme: PID is the conventional and very popular control scheme, with the structure given in (1) and (2) and represented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Structure of PID control scheme.

The Laplace form of (1) is given in (2).

where KP, KI, and KD are PID parameters, E(t) is the error signal, U(t) is the response of the controller, and GPID is the transfer function of the PID controller.

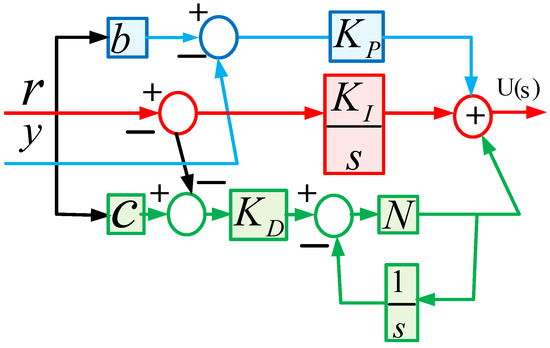

PID-2DF control scheme: PID-2DF (two degrees of freedom, as shown in Figure 11) controllers offer advantages over traditional PID controllers by allowing the independent tuning of set point tracking and disturbance rejection, leading to improved control performance. They provide better transient response, reduce overshoot, and enhance system stability, making them ideal for applications requiring precise and adaptable control. A well-known form of the PID-2DF controller is given as

where KP, KI, and KD are PID-2DF parameters, b is a weighting factor for KP, r is the reference input, y is the measured variable, c is the weighting factor for the derivative term, U(s) is Laplacian response of the controller, and N is the derivative filter coefficient.

Figure 11.

Structure of PID-2DF control scheme.

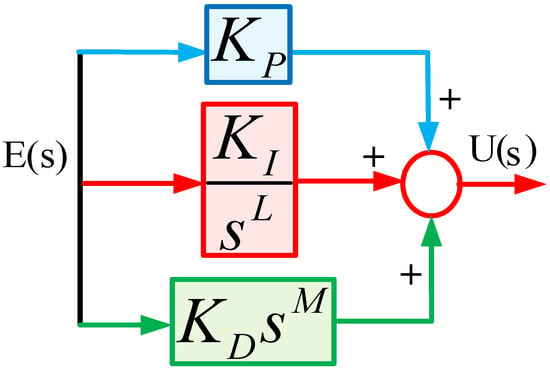

FOPID control scheme: The implementation of the FO transfer function was proposed by Oustaloup, which is reported in [25,26,27,28,29,30]. The FOPID controller shown in Figure 12 can be represented as given in (4).

where D = . The FOPID controller can also be represented as (5).

where are FOPID gains, and and are the fractional integrator and differentiator.

Figure 12.

Structure of FOPID scheme.

The authors used the other variants of the FOPID control structure in order to determine the best control scheme for the tested system.

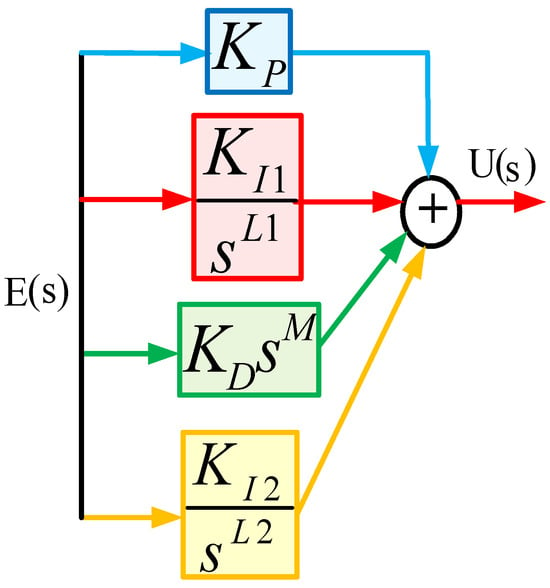

FOPID-FOI control scheme: FOPID-FOI controllers, shown in Figure 13, offer improved stability and better handling of nonlinearities due to the additional fractional-order integral component that provides small steady-state errors and smoother control.

where KP, KI1, KD, KI2 = FOPID-FOI parameters; SL1, SL2 = fractional terms of the integra; SM = fractional term of the derivative.

Figure 13.

Structure of FOPID-FOI scheme.

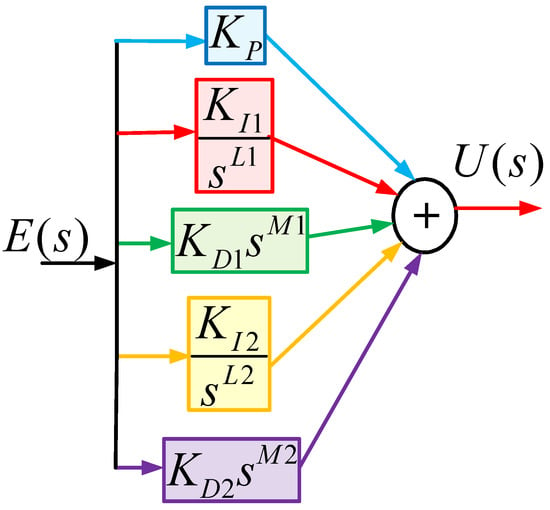

FOPID-FOID control scheme: FOPID-FOID controllers, shown in Figure 14, offer improved stability and better handling of nonlinearities, as well as enhanced robustness over FOPID and FOPID-FOI control schemes. It has an additional fractional-order integral-derivative component in order to provide small steady-state errors, better control, and improved overall stability.

where, KP, KI1, KD1, KI2, KD2 = FOPID-FOID parameters; SL1, SL2 = fractional terms of the integral; SM1, SM2 = fractional term of the derivative.

Figure 14.

Structure of FOPID-FOID scheme.

4. The Optimization Algorithm

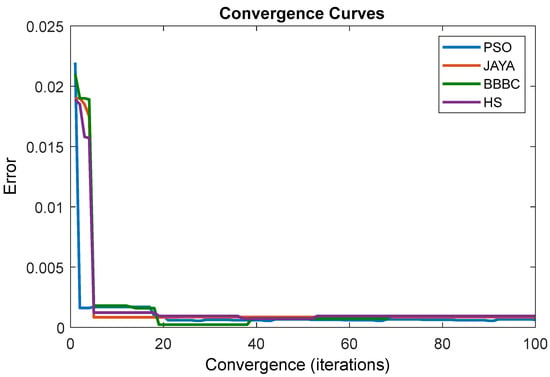

A controller is as only as good as its parameters. In the literature, several optimization algorithms have been used in order to design the parameters of the control scheme. Some of the popular algorithms are big bang-big crunch (BBBC), particle swarm optimization (PSO), harmony search (HS), and JAYA. In this work, the authors obtained the parameters using all the given algorithms; however, the parameters obtained using JAYA were used due to its fast convergence. The comparative convergence curve is shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

The comparative convergence curve.

JAYA Algorithm

The JAYA algorithm is a simple method for optimizing controller settings in load frequency control (LFC) systems. It performs better than traditional methods like genetic algorithms (GA) and particle swarm optimization (PSO), making it suitable for real-time applications. It is characterized by ease of implementation and convergence assurance, and works well for multiarea power system. It is more computationally efficient and has faster convergence than GA and PSO, as well as low computational complexity. Regarding the quality of the solution, JAYA has global optimization capability.

The features of JAYA are as given below:

- Feature 1: JAYA is a simple and straightforward algorithm to implement that does not require parameters like crossover/mutation rates.

- Feature 2: It modifies its approach using exploration to obtain an understanding, and it uses exploitation in order to maximize the finest solutions (exploration—exploitation).

- Feature 3: It converges quickly in order to perform efficiently.

The steps for designing a controller using JAYA are as follows:

Step 1: JAYA is used to minimize the objective function given below in order to obtain the parameters of the designed controllers.

where k = areas, ACE = area control error, ∆f = deviation in frequency, Bi = bias factor, and ∆Ptie = tie-line deviations.

Step 2: This step involves the initialization of the population of the solution parameters (gains) for each control scheme, i.e., PID, PID-2DF, FOPID, FOPID-FOI, and FOPID-FOID (initialization).

Step 3: In this step, the objective function given in step 1 is calculated for each parameter to check the fitness of the solution (evaluation).

Step 4: This step involves the update of the parameters based on best or worst solutions (update).

where

Step 5: This step involves comparing the current and new solutions, and, if new solutions have better fitness, the current ones are replaced with new ones (selection).

Step 6: This step involves determining the optimal parameters or stopping the algorithm if the threshold is achieved. In that event, repeat steps 1–4 again in order to obtain the optimal parameters (termination).

5. Results and Discussion

The overall system was modeled in the SIMULINK/MATLAB ver. R2018a environment to investigate the performance of the designed control schemes. As mentioned, area 1 consisted of thermal, geothermal, and EV generation systems. area 2 consisted of EV and thermal generation systems, and area 3 had gas, EV, and hydro systems. Apart from this, an SMES device was also incorporated in area 1 and a TCPS system was inserted between areas 1 and 2. The following cases were considered in order to check the controller’s performance.

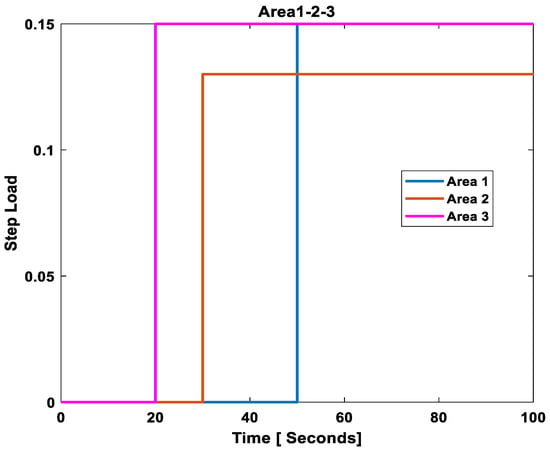

Case 1: Case 1 deals with normal system parameters and a step load of 0.15 pu, 0.13 pu, and 0.15 pu in area 1, area 2, and area 3, respectively.

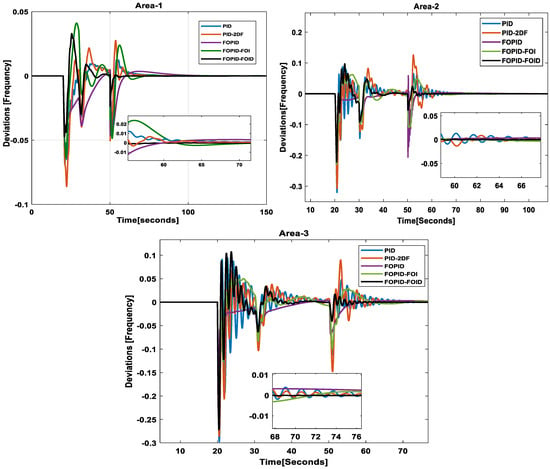

Frequency Deviation: The step load in all three areas is presented in Figure 16. From the comparative analysis of the frequency deviation results (Figure 17) for various controllers, it is evident that the FOPID-FOID controller exhibits superior performance, particularly in terms of settling time. While the traditional PID controllers and their variant PID-2DF demonstrate competent control over frequency deviations, their settling times are relatively longer. The FOPID and FOPID-FOI controllers offer improvements by incorporating fractional calculus, leading to enhanced adaptability and precision. However, the FOPID-FOID controller achieves the most significant reduction in settling time.

Figure 16.

Step load in all areas.

Figure 17.

Frequency deviations in all areas.

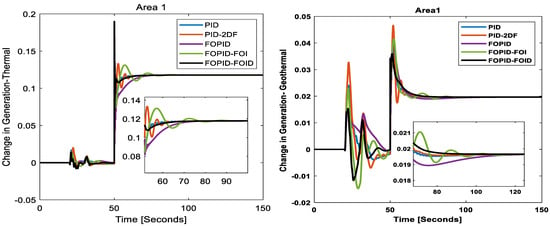

Change in generation/(area 1): In evaluating the change in generation using the applied control schemes, as shown in Figure 18, it becomes clear that the FOPID-FOID controller delivers superior performance. PID controllers, while effective in managing generation changes, often struggle with overshoot and longer stabilization periods. It can be seen that the generators in area 1 respond to load perturbation and change their generation as per the requirements. The thermal generators provide 0.1179 pu, the geothermal plant provides 0.1964 pu, and the EVs change their generation and settling to 0.125 pu in order to keep a balance between generation and demand of 0.15 pu in area 1.

Figure 18.

Change in generation in area 1.

The PID-2DF controller offers some improvement, leading to better control and quicker response. The FOPID and FOPID-FOI controllers enhance control accuracy and response times. However, the FOPID-FOID controller excels and significantly refines the control process. This control scheme results in more precise and quicker adjustments in generation, minimizing overshoot and achieving desired power output levels more rapidly and with greater stability than the other control methods.

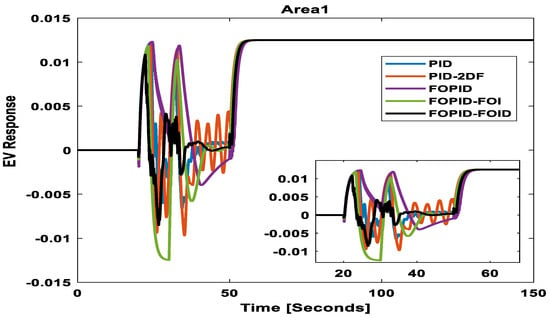

In the assessment of the change in the electric vehicle (EV) response (Figure 19), the FOPID-FOID controller stands out for its superior performance. PID controllers, while competent in managing EV response changes, exhibit longer response times. The PID-2DF controller leads to better response times. The FOPID and FOPID-FOI controllers deliver more precise control and faster response times, outperforming their integer-order counterparts. Nevertheless, the FOPID-FOID controller surpasses all others in significantly reducing response time and minimizing overshoot in the EV response.

Figure 19.

EV response in area 1.

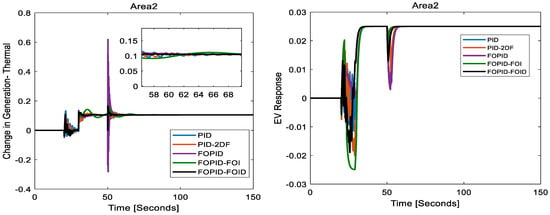

Change in generation/(area 2): The change in generation for thermal and electric vehicle (EV) generation in area 2, using various control schemes, is given in Figure 20. The FOPID-FOID controller demonstrates superior performance. PID controllers, although effective in managing generation changes, deliver it with a prolonged stabilization time. The PID-2DF controller provides some improvement over PID. The FOPID and FOPID-FOI controllers offer more accurate control and faster response times, ensuring rapid and stable adjustments to generation changes. The results show that the thermal plant in area 2 regulates its generation and settles to 0.105 pu, whereas the EVs settle to 0.025 pu in order to take care of the load demand of 0.13 pu in area 2.

Figure 20.

Change in generation and EV response in area 2.

Change in generation/(area 3): We analyzed the control performance for changes in generation, thermal, electric vehicle (EV), and gas generation in area 3. The results given in Figure 21 clearly indicate that the FOPID-FOID controller delivers the most effective performance. It is also seen that the hydropower plant in area 3 regulates its generation and settles to 0.08036 pu, the gas plant settles to 0.03214 pu, whereas the EVs settle to 0.0375 pu in order to meet the load demand of 0.15 pu in area 3. PID controllers, though capable, often face difficulties with overshoot and settling times in multisource, multiarea systems. The PID-2DF controller enhances performance by introducing an additional degree of freedom. But, controllers utilizing fractional calculus, such as FOPID and FOPID-FOI, provide improved precision and faster response times.

Figure 21.

Change in generation (hydro, gas) and EV response in area 3.

However, the FOPID-FOID controller stands out and offers significant advantages in handling the dynamic changes in thermal, EV, and gas generation in area 3. This advanced controller significantly reduces response times and minimizes overshoot, achieving rapid and stable generation adjustments.

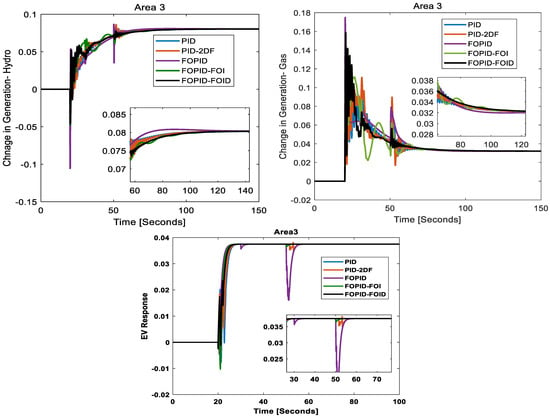

Area control error (ACE): When analyzing the area control error (ACE) across all three areas using the different control schemes—PID, PID-2DF, FOPID, FOPID-FOI, and FOPID-FOID—it is evident that the FOPID-FOID controller produces the best performance. The results shown in Figure 22 evidence that FOPID-FOID performs better than the other used control approaches. This advanced control strategy effectively minimizes the ACE in all three areas by reducing response time and overshooting, ensuring more stable and accurate control.

Figure 22.

Area control error in all areas.

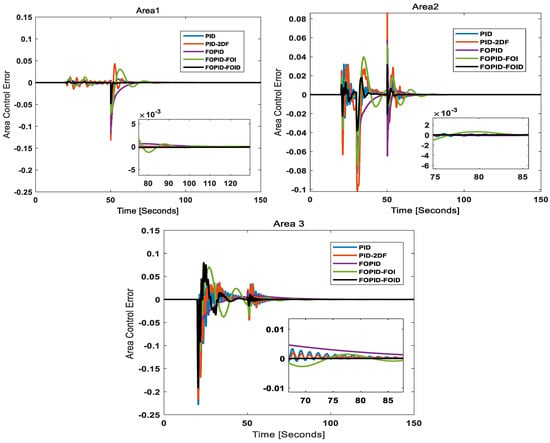

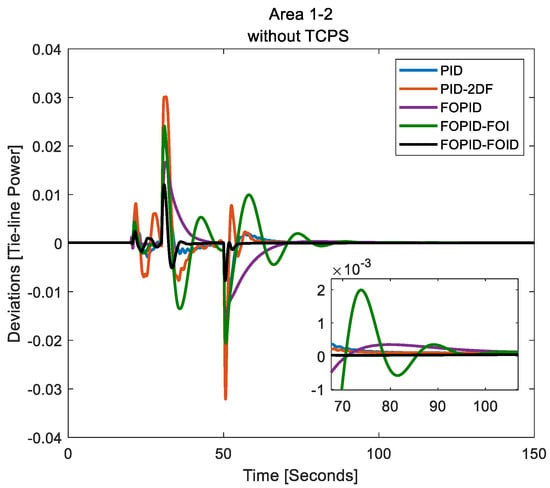

Tie-line power: The results of the tie-line power deviations in all areas are given in Figure 23. Tie-line power faces deviations with the occurrence of load perturbations, and it is seen that among all the control approaches, the FOPID-FOID scheme works better and reduces tie-line power oscillations and minimizes overshoot, more rapidly than other schemes. Areas 1–2 also have a TCPS to overcome the deviations’ oscillations and slower settling times.

Figure 23.

Tie-line power deviations (all areas) and TCPS response (areas 1–2).

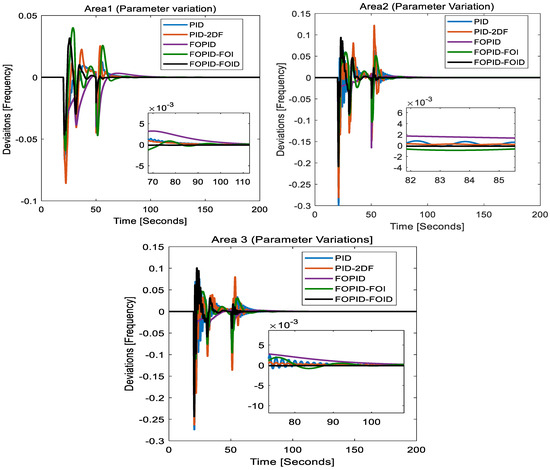

Case 2: Case 2 deals with changes in system parameters and a step load of 0.2 pu, 0.15 pu, and 0.15 pu in area 1, area 2, and area 3, respectively.

The performance of the designed control schemes was checked for parameter variation in order to verify whether controllers can handle the parameter uncertainty or not. In all areas, the power system gain and time constant were modified as given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters changes in all areas.

Though the results for this case were obtained for generation, ACE, and tie-line power, only the frequency deviation results are given here, as shown in Figure 24. Upon analysis, it was found that though all control schemes are able to handle this parameter variation, they exhibit oscillations in magnitude (generally increasing the magnitude of undershoot and overshoot) and have a longer settling time; however, the FOPID-ID control scheme still performs better the all others and provides the results with the shortest settling time with no or very little change in oscillations. It manages parameter variations more effectively, resulting in fewer oscillations and faster settling times.

Figure 24.

Frequency deviations in all areas.

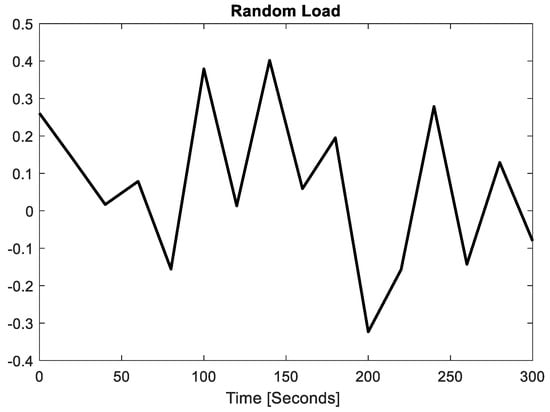

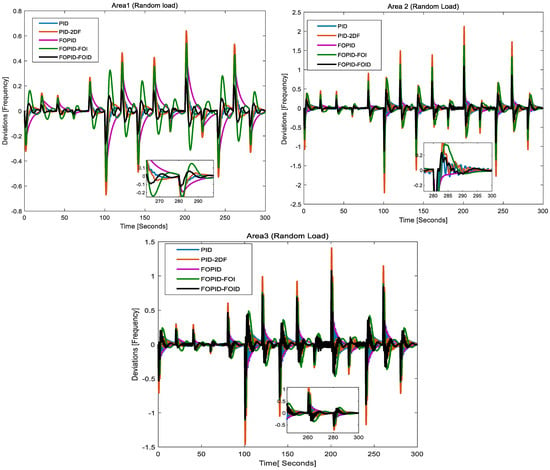

Case 3: Case 3 deals with normal system parameters and a random load in area 1, area 2, and area 3.

The performance of the designed control schemes was checked for random load disturbance applied in all areas in order to verify the behavior of the designed controller behavior if a sudden load of random nature occurs. The nature of the load is given in Figure 25. The frequency deviations in all areas for this load perturbation are given in Figure 26. The analysis reveals that the FOPID-FOID control scheme is superior in handling the random load disturbance and exhibits smaller oscillations. It consistently maintains more stable and accurate frequency control under random load changes, outperforming all other control methods. PID controllers, although effective, show increased deviations and longer settling times. These controllers struggle to stabilize quickly under random load disturbances, leading to less-consistent frequency control.

Figure 25.

Random load profile.

Figure 26.

Frequency deviations in all areas.

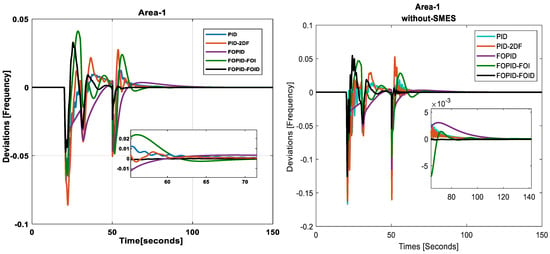

Case 4: Case 4 deals with normal system parameters and a step load in area 1, area 2, and area 3 (without SMES or TCPS).

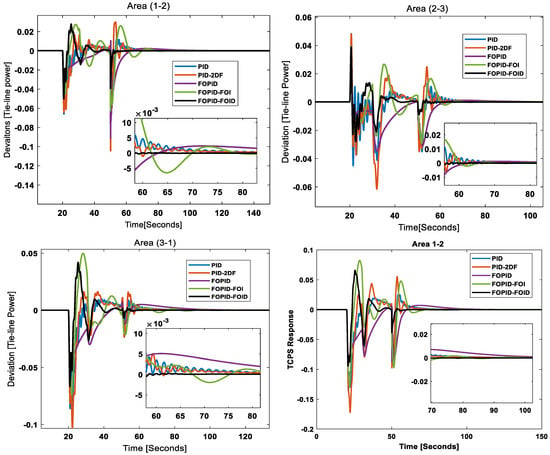

Frequency deviation (with and without SMES): The frequency deviation in area 1 typically shows larger and more persistent oscillations due to the lack of rapid energy exchange capability. The presence of SMES reduces the settling time considerably. The fast response tune of SMES allows it to quickly counteract deviations by injecting or absorbing power almost instantaneously. As a result, the system returns to its nominal frequency much faster compared to scenarios without SMES, as given in Figure 27.

Figure 27.

Frequency deviation (without SMES).

Tie-line power deviations (with and without TCPS): The thyristor-controlled phase shifter (TCPS) can lead to significant improvements in tie-line power deviation in area 1 which demonstrates smaller oscillations and reduced settling time when TCPS is integrated. The tie-line power deviation in area 1 typically shows larger and more persistent oscillations. This is because conventional control methods cannot rapidly adjust the phase angle of the power flow, leading to less-efficient power exchange between areas. TCPS effectively mitigates these oscillations, as given in Figure 28. As a result, the system achieves the desired tie-line power level much faster and with smaller oscillations compared to scenarios without TCPSs. Table 3. Shows the Optimal coefficients for various controllers.

Figure 28.

Tie-line power deviations (without TCPS).

Table 3.

Optimal coefficients for various controllers.

Table 4 shows the performance analysis of PID, PID-2DF, and fractional controllers for multiarea LFC. The analysis in Table 5 and Table 6 shows that fractional-order controllers (especially FOPID-FOID) exhibit better stability and reduced frequency deviations across different areas and provide better adaptability to system dynamics.

Table 4.

Performance analysis of PID, PID-2DF, and fractional controllers for multiarea LFC.

Table 5.

Statistical parameters of frequency deviation (all areas).

Table 6.

Statistical parameters of tie-line power deviation (all areas).

The findings are provided in Table 7.

Table 7.

Percentage improvement in settling time, overshoot, and undershoot.

Settling time improvements: The FOPID-FOID controller demonstrates the best improvement in settling time for area 1 (23.81%) and area 2 (40.00%).

Overshoot reductions: The FOPID controller in area 3 shows the highest improvement in overshoot (96.3%).

Undershoot improvements: The FOPID-FOID controller improves undershoot in area 1 by 30.5% compared to the PID controller.

The result and discussion can be summarized in the following manner:

- (a)

- Main Findings of this Study

This study revealed that the FOPID-FOID controller outperforms other control techniques when it comes to controlling frequency deviations and generation changes in the studied multisource hybrid power system. The key findings include the following:

- The FOPID-FOID controller considerably reduces settling time and overshoot compared to the PID, PID-2DF, FOPID, and FOPID-FOI controllers.

- The integration of energy storage devices like SMES and TCPS enhances system performance, reduces deviations, and increases response times.

- All controllers effectively handle parameter variations, but the FOPID-FOID consistently exhibits superior performance, especially for settling time.

- (b)

- Comparison with Other Studies

When compared to previous research, this study reveals that advanced control techniques perform better in multiarea power systems. Although many studies emphasize the efficiency of PID controllers, this study shows that fractional-order controllers, specifically the FOPID-FOID, offer greater adaptability and precision. Additionally, the inclusion of SMES and TCPS has not been frequently examined in earlier research; thus, this study focused on their relevance too.

- (c)

- Implication and Explanation of Findings

The results show that employing advanced/sophisticated control techniques can greatly improve power system performance. The FOPID-FOID controller may offer a strong foundation for control design in complex and dynamic environments. This study also shows the importance of the SMES and TCPS in reducing oscillations and enhancing settling times, which are critical for reliable power delivery following varying demands.

- (d)

- Strengths and Limitations

Strengths:

- We comprehensively evaluated several control strategies for various operational scenarios like parameter variations and random load disturbances.

- We integrated advanced control schemes like FOPID-FOID with energy storage (SMES) and phase control technologies (TCPS).

- The detailed simulation results support the claims regarding performance improvements.

Limitations:

- This study mainly relied on simulations, which may not fully model the uncertainties in real-world applications.

- The result’s applicability to various power system operating conditions may be limited by different power systems’ operational conditions.

- Future research could focus on experimental validation to enhance the reliability of the proposed control strategies.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study contributes significantly to the understanding of control strategies for load management in energy systems, particularly through the application of various controllers, including PID, FOPID, PID-2DF, FOPID-FOI, and FOPID-FOID. The theoretical contributions of this research include a detailed comparative analysis of these controllers across different load types—thermal, electric vehicle (EV), geothermal, hydropower, and gas—highlighting the unique advantages of fractional-order control techniques in enhancing system performance. The results provided in the various figures demonstrate that the FOPID-FOID controller consistently outperforms traditional control strategies, achieving shorter settling times and minimizing oscillations in all three areas studied. In area 1, the FOPID-FOID controller shows remarkable effectiveness in suppressing oscillations and responding to load changes under varying conditions. In area 2, it facilitates quicker stabilization of thermal and EV load management, while in area 3, it adeptly manages the complexities of hydropower and gas generation, reinforcing its applicability to real-world scenarios where rapid response and precision are critical. Form the analysis of Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7, it is seen that the FOPID-FOID controller provides significant reductions in oscillations and settling times in order to improve system dynamics. Therefore, this control scheme is suitable for LFC schemes of multiarea hybrid power system. Despite these strengths, this study has limitations, primarily its reliance on simulation data, which may not fully capture the dynamics of actual power systems. Additionally, the specific configurations and parameters used may limit the generalizability of the findings.

7. Future Research

Future research should focus on the experimental validation of these control strategies in real-world/practical applications. In order to further improve control schemes, FOPID-FOID may be used with machine learning and predictive analytics. In energy management systems, FOPID-FOID is a promising control scheme. These findings not only advance the theoretical knowledge but also pave the way for practical applications that can successfully meet the changing demands of modern power systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.N., K.V. and G.S.P.; Methodology, K.N., K.V., G.S.P., K.S. and M.B.; Software, K.N., K.V., G.S.P., K.S. and S.S.; Validation, G.S.P., K.S., S.S. and M.B.; Formal analysis, S.S., M.B. and R.K.; Investigation, S.S., M.B. and R.K.; Resources, K.N., K.V., G.S.P., K.S. and S.S.; Data curation, K.N., K.V., G.S.P. and K.S.; Writing—original draft, K.N. and K.V.; Writing—review & editing, R.K.; Visualization, R.K.; Supervision, M.B. and R.K.; Project administration, M.B. and R.K.; Funding acquisition, R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations and Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | Nomenclature | ||

| LFC | Load frequency control | Δf | Change in frequency (Hz) |

| AGC | Automatic generation control | Change in power of EV | |

| Ptie | Tie-line power | KP | Proportional gain |

| EVs | Electric vehicles, | KI | Integral gain |

| f/Reg | Frequency/regulation (Hz/pu MW) | KD | Derivative gain |

| i | Subscript for areas | L | Fractional-order of the integral operator |

| Pg/Pd | Generated/demanded power | M | Fractional-order of the derivative operator |

| BBBC | Big bang-big crunch | ΔPtie | Tie-line power deviation (MW) |

| ICA | Imperialistic competition | Ts | Settling time (seconds) |

| FOPID | Fractional-order proportional-integral-derivative | ||

| FOID | Fractional-order integral derivative | ||

| PID | Proportional integral derivative | ||

| SMES | Superconducting magnetic energy storage | ||

| TCPS | Thyristor-controlled phase shifter | ||

| JAYA | JAYA optimization algorithm | ||

| ACE | Area control error | ||

| RES | Renewable energy source | ||

| BESS | Battery energy storage system | ||

| TID | Tilt integral derivative | ||

| GA | Genetic algorithm | ||

| PSO | Particle swarm optimization | ||

| ITAE | Integral time absolute error | ||

| ISE | Integral square error | ||

| MSE | Mean square error | ||

Appendix A

Thermal Power System: = 0.08 s, = 5 s, = 120.

= 10 s, = 0.3 s, = 20 s, = 2.4.

Geo Thermal Power Plant: = 0.5 s, = 0.1 s.

SMES: = 0.2333 s, = 0.16 s, = 0.7087 s, = 0.2481 s, = 0.205, = 0.03 s.

TCPS: = 2, = 0.02 s.

Hydro Power System: = 0.513 s, = −1 s, = 48.7 s, T = 5 s,

Gas Power System: = 0.2 s, = 1 s, = 0.6 s, = 1 s, = 0.049 s, = −0.01 s, = 0.239 s.

Electric Vehicle: = 1, = 1, = 500, 1000, 1500.

References

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, P. Load Frequency Control of Multi-area Interconnected Power System with Renewable Energy. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Sustainable Power and Energy Conference (iSPEC), Nanjing, China, 23–25 December 2021; pp. 1814–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadi, M.; Shobole, A.; Elmasry, W.; Kucuk, I. Load frequency control in smart grids: A review of recent developments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189 Pt A, 114013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, M.; Shankar, R. A literature survey on load frequency control considering renewable energy integration in power system: Recent trends and future prospects. J. Energy Storage 2022, 45, 103717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ShangGuan, X.-C.; He, Y.; Zhang, C.-K.; Jin, L.; Jiang, L.; Wu, M.; Spencer, J.W. Switching system-based load frequency control for multi-area power system resilient to denial-of-service attacks. Control Eng. Pract. 2021, 107, 104678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroposki, B. Integrating high levels of variable renewable energy into electric power systems. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean. Energy 2017, 5, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasolomampionona, D.D.; Połecki, M.; Zagrajek, K.; Wróblewski, W.; Januszewski, M. A comprehensive review of load frequency control technologies. Energies 2024, 17, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, A.K.; Singh, D.; Khan, H.; Kumar, P. Application of PID Controller Tuning Method for Load Frequency Control in Multi Area Power System at Different Load Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Integrated Circuits, Communication, and Computing Systems (ICIC3S), Una, India, 8–9 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.B.; Dada, E.G.; Abidemi, A.; Oyewola, D.O.; Khammas, B.M. Metaheuristic algorithms for PID controller parameters tuning: Review, approaches and open problems. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, A.; Yousri, D.; Rezk, H.; Thanikanti, S.B.; Hasanien, H.M. A Robust Fractional-Order PID Controller Based Load Frequency Control Using Modified Hunger Games Search Optimizer. Energies 2022, 15, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, F.; Ayaz, M.; Baig, D.-E.-Z.; Rizvi, S.M.H. Intelligent Control Algorithms for Enhanced Frequency Stability in Single and Interconnected Power Systems. Electronics 2024, 13, 4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, P.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z. Load frequency regulation of multi-area power systems with communication delay via cascaded improved ADRC. Energy Rep. 2023, 8–9, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, M. Optimal design of fuzzy-PID controller for automatic generation control of multi-source interconnected power system. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 18859–18880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.K.; Kar, M.K.; Singh, A.K. Design of a 2-DOF-PID controller using an improved sine–cosine algorithm for load frequency control of a three-area system with nonlinearities. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2022, 71, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.K.; Singh, A.K.; Mahanty, R.N. Load frequency control with moth-flame optimizer algorithm tuned 2-DOF-PID controller of the interconnected unequal three area power system with and without non-linearity. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2023, 14, 1912–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondhi, S.; Hote, Y.V. Fractional order PID controller for load frequency control. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 85, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Chattterjee, K.; Vishwakarma, C.B. Two degree of freedom internal model control-PID design for LFC of power systems via logarithmic approximations. ISA Trans. 2018, 72, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, R.K.; Panda, S.; Rout, U.K. DE optimized parallel 2-DOF PID controller for load frequency control of power system with governor dead-band nonlinearity. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2013, 49, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariki, M.; Shankar, R. Optimal CC-2DOF(PI)-PDF controller for LFC of restructured multi-area power system with IES-based modified HVDC tie-line and electric vehicles. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2022, 32, 101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y. Fractional-Order Load Frequency Control of an Interconnected Power System with a Hydrogen Energy-Storage Unit. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Gupta, D.K.; Ghatak, S.R.; Appasani, B.; Bizon, N.; Thounthong, P. A Novel Hybrid GSA-BPSO Driven PID Controller for Load Frequency Control of Multi-Source Deregulated Power System. Mathmematics 2022, 10, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Zeng, Y.; Qian, J.; Yang, F.; Li, Y. CPSOGSA Optimization Algorithm Driven Cascaded 3DOF-FOPID-FOPI Controller for Load Frequency Control of DFIG-Containing Interconnected Power System. Energies 2023, 16, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Nayak, P.C.; Prusty, R.C.; Panda, S. Design of fractional order multistage controller for frequency control improvement of a multi-microgrid system using equilibrium optimizer. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Des. 2024, 7, 1357–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, D.; Jagatheesan, K.; Shah, P.; Sekhar, R. Fractional order PIλDμ controller for microgrid power system using cohort intelligence optimization. Results Control Optim. 2023, 11, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santra, S.; De, M. Mountain gazelle optimization based 3DOF-FOPID-virtual inertia controller for frequency control of low inertia microgrid. IET Energy Syst. Integr. 2023, 5, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Tyagi, B.; Kumar, V. Deregulated Multiarea AGC Scheme Using BBBC-FOPID Controller. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2017, 42, 2641–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sousy, F.F.M.; Alqahtani, M.H.; Aljumah, A.S.; Aly, M.; Almutairi, S.Z.; Mohamed, E.A. Design Optimization of Improved Fractional-Order Cascaded Frequency Controllers for Electric Vehicles and Electrical Power Grids Utilizing Renewable Energy Sources. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, A.; Allam, D.; Attia, H.A. Supporting load frequency control process by using adaptive model reference virtual inertia controller when connecting renewable energy plants. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 117, 109295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, A.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Das, D.C.; Ustun, T.S.; Iqbal, A. A review on fractional order (FO) controllers’ optimization for load frequency stabilization in power networks. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 4009–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, D.; Panda, S. Fractional order based controller for frequency control of hybrid power system. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Sustainable Energy Technologies and Systems (ICSETS), Bhubaneswar, India, 26 February–1 March 2019; pp. 087–092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayeghi, H.; Rahnama, A.; Mohajery, R.; Bizon, N.; Mazare, A.G.; Ionescu, L.M. Multi-Area Microgrid Load-Frequency Control Using Combined Fractional and Integer Order Master–Slave Controller Considering Electric Vehicle Aggregator Effects. Electronics 2022, 11, 3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.K.; Jha, A.V.; Appasani, B.; Srinivasulu, A.; Bizon, N.; Thounthong, P. Load Frequency Control Using Hybrid Intelligent Optimization Technique for Multi-Source Power Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.P.; Mohanty, S.R.; Kishor, N.; Ray, P.K. Robust H-infinity load frequency control in hybrid distributed generation system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2013, 46, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappachen, A.; Fathima, A.P. Critical research areas on load frequency control issues in a deregulated power system: A state-of-the-art-of-review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.I.A.E.; Diab, A.A.Z.; Hassan, A.A. Adaptive Load Frequency Control Based on Dynamic Jaya Optimization Algorithm of Power System with Renewable Energy Integration. In Proceedings of the 2019 21st International Middle East Power Systems Conference (MEPCON), Cairo, Egypt, 17–19 December 2019; pp. 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, A. Load Frequency Control of Two Area and Multi Source Power System Using Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2019 11th International Conference on Electrical and Electronics Engineering (ELECO), Bursa, Turkey, 28–30 November 2019; pp. 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, R.K.; Panda, S.; Padhan, S. A novel hybrid gravitational search and pattern search algorithm for load frequency control of nonlinear power system. Appl. Soft Comput. 2015, 29, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Prasad, L.B. Optimal load frequency control of multi-area multi-source deregulated power system with electric vehicles using teaching learning-based optimization: A comparative efficacy analysis. Electr. Eng. 2024, 106, 1865–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamraju, A.; Nandiraju, S. Coordinated control of conventional power sources and PHEVs using jaya algorithm optimized PID controller for frequency control of a renewable penetrated power system. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2019, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Datta, P.; Sharma, K.; Mehrotra, R.; Singh, J. Controlling Load Frequency in a Hybrid Power System Including Electrical Vehicles. In Modern Electronics Devices and Communication Systems; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Agrawal, R., Kishore Singh, C., Goyal, A., Singh, D.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023; Volume 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveenkumar, S.; Agyekum, E.B.; Ampah, J.D.; Afrane, S.; Velkin, V.I.; Mehmood, U.; Awosusi, A.A. Techno-economic optimization of PV system for hydrogen production and electric vehicle charging stations under five different climatic conditions in India. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 38087–38105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.; Agyekum, E.B.; Kumar, A.V.; Velkin, I. Performance evaluation with low-cost aluminum reflectors and phase change material integrated to solar PV modules using natural air convection: An experimental investigation. Energy 2023, 266, 126415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, K.P.; Ashfaq, H.; Kumar, R.; Singh, R. Designing a Bidirectional Power Flow Control Mechanism for Integrated EVs in PV-Based Grid Systems Supporting Onboard AC Charging. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkarna, M.; Ashfaq, H.; Singh, R.; Kumar, R. A new analytical method for optimal sizing and sitting of Type-IV DG in an unbalanced distribution system considering power loss minimization. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2022, 17, 2579–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).