Abstract

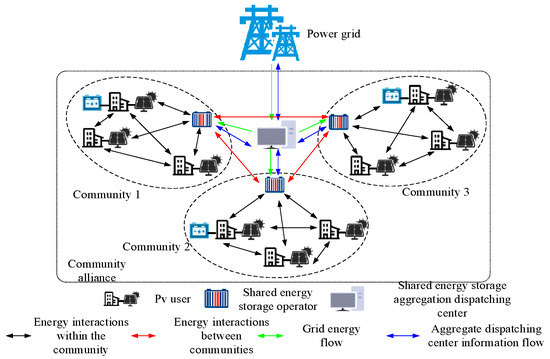

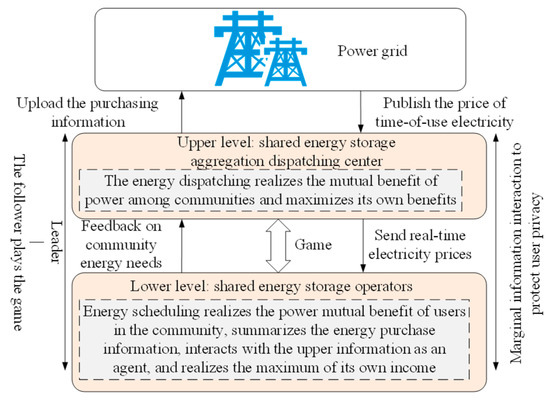

Energy storage (ES) units are vital for the reliable and economical operation of the power system with a high penetration of renewable distributed generators (DGs). Due to ES’s high investment costs and long payback period, energy management with shared ESs becomes a suitable choice for the demand side. This work investigates the sharing mechanism of ES units for low-voltage (LV) energy prosumer (EP) communities, in which energy interactions of multiple styles among the EPs are enabled, and the aggregated ES dispatch center (AESDC) is established as a special energy service provider to facilitate the scheduling and marketing mechanism. A shared ES operation framework considering multiple EP communities is established, in which both the energy scheduling and cost allocation methods are studied. Then a shared ES model and energy marketing scheme for multiple communities based on the leader–follower game is proposed. The Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) condition is used to transform the double-layer model into a single-layer model, and then the large M method and PSO-HS algorithm are used to solve it, which improves convergence features in both speed and performance. On this basis, a cost allocation strategy based on the Owen value method is proposed to resolve the issues of benefit distribution fairness and user privacy under current situations. A case study simulation is carried out, and the results show that, with the ES scheduling strategy shared by multiple renewable communities in the leader–follower game, the energy cost is reduced significantly, and all communities acquire benefits from shared ES operators and aggregated ES dispatch centers, which verifies the advantageous and economical features of the proposed framework and strategy. With the cost allocation strategy based on the Owen value method, the distribution results are rational and equitable both for the groups and individuals among the multiple EP communities. Comparing it with other algorithms, the presented PSO-HS algorithm demonstrates better features in computing speed and convergence. Therefore, the proposed mechanism can be implemented in multiple scenarios on the demand side.

1. Introduction

Multiple types of energy sources, including large amounts of renewable distributed generators (DGs) and energy storage (ES) units are intensively interacting in the new power system [1]. Among them, the integrated energy system (IES) on the demand side can provide flexible energy services by considering various features of the multiple energy sources (such as electric and thermal sources) and taking full advantage of their complementary properties [2]. A high penetration of renewable energies can pose a severe challenge to the power system, and their outputs may have to be cut due to their fluctuating and intermittent nature [3]. ES units can be used to smooth the fluctuations, but their implementations could be limited due to high investment and maintenance costs [4]. Therefore, flexible and diversified energy-sharing mechanisms like a “clouded ES system” [5] or “ES leasing” [6,7] have been proposed to improve the economic benefits of ESs through cost sharing and economies of scale [8,9] and promote “self-consumption” for local DGs [10].

A microgrid with an optimized ES sharing configuration is proposed to participate in demand response services [11]. The ES sharing framework must be built considering the complementarity of power generation and consumption behavior among different prosumers [12]. A real-time joint system of ES sharing and load management is developed to meet household needs and reduce energy costs [13]. Blockchain can be used to enhance trust in energy marketing within the community [14,15]. In [16,17], a two-stage credit-sharing model is proposed between the coordinator who manages the shared ES system (ESS) and the producers who purchase energy from the former. A shared hybrid ES framework, which consists of private ES units from energy suppliers and independent ES operators, is capable of providing ES services for the whole community [18].

Numerous energy prosumers (EPs) will be the major players in future energy markets, and game theory is an effective method to coordinate their interests [19]. At present, most of the game theory implementations for a shared ES system are based on the master-slave scheme [20,21,22], but they require participants to determine the identity of buyers/sellers in advance, which may limit the flexibility of participants. On the other hand, a multiple-agent cooperative game for a shared ES model is often difficult to achieve due to the conflict of interests among agents [23]. The multiple-timescale rolling optimization of the IES with a hybrid ES system is investigated, in which the uncertainty of price, renewable energies, and loads are considered [24]. An optimal scheduling model is proposed for an integrated energy microgrid system considering electric and thermal ES units [25,26]. A combined hybrid ESS containing electric, thermal, hydrogen, and natural gas storage devices can be scheduled by a hybrid ES operator (IHESO) to provide energy marketing services [27]. Algorithms like adaptive wavelet decomposition and fuzzy control theory are proposed for hybrid ES units [28]. In [29], the IES planning optimization model is proposed, considering the mixed storage differentiation characteristics.

For one single energy community, the effects of load scheduling or any other interaction with the power grid may not be evident. However, clustered communities can operate in coordination through sophisticated scheduling, thus greatly improving the potential of the whole “source–load–storage” system [30]. A double-layered energy optimization framework can coordinate the benefits for all participants and reduce operating costs for multiple communities [31]. Non-cooperative aggregate game theory is used in a double-layer energy management scheme in which day-ahead optimal scheduling and dynamic electricity prices are introduced for multiple-community systems [32,33]. For the demand side (or microgrids), an advanced stochastic optimization method based on deep reinforcement learning can provide the optimal redistribution of active power between subsystems by minimizing network losses [34]. Bilevel programming and reinforcement learning, for constructing and solving the internal local market of community microgrids, makes it possible to enable the interaction of the local control systems for microgrids with the community microgrid operator [35].

For these secondary energy markets, the normalization of energy interacting procedures and the fairness of energy marketing profits still need to be improved. Meanwhile, privacy protection for energy market participants also needs to be considered [36,37]. Therefore, it is essential to develop a new sharing mechanism to promote renewable utilization, enhance ES operation flexibility, and improve social welfare. In the meantime, how to evaluate the effects of the sharing business on the energy system is another key issue to be focused on. A suitable energy trading mechanism is needed for the sharing market, while protecting the privacy of individual users is also an important issue.

In this work, the shared ES-based energy scheduling and trading mechanism for multiple energy communities on the demand side are developed. First, in Section 2, a shared ES operation framework considering multi-new energy communities is proposed, and the operation strategies of each participant under this framework are analyzed. In Section 2.1, the ES model is introduced, and its physical form and mathematical model are analyzed. In Section 2.2 and Section 2.3, a shared ES model of multi-new energy communities based on a leader–follower game is proposed. Then, in Section 2.4, an ES-sharing cost allocation strategy based on the Owen value method is proposed. Finally, in Section 3, the advanced nature and fairness of the proposed framework and strategy are verified by simulation cases.

3. Case Study

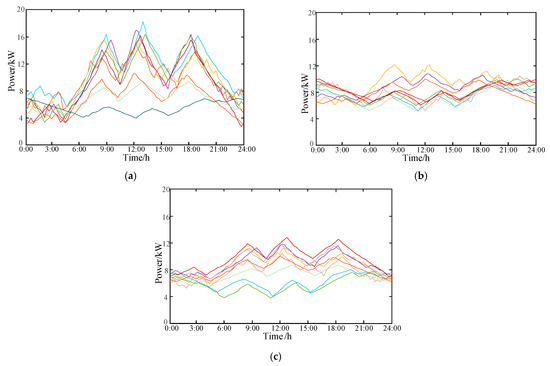

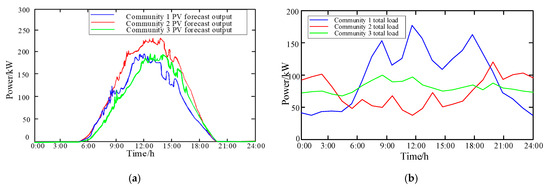

Three energy communities are selected for analysis, and the DG (such as PV) resources in each community are sufficient. We assume that the users are typical commercial users of domestic EPs, with the DG units rated at around 30 kw. Each community had nine users equipped with PV devices, and the load data of each user in the three communities are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Load profiles of Community 1, Community 2, and Community 3 (each has 9 users). (a) Community 1. (b) Community 2. (c) Community 3.

A time of 24 h is taken as a scheduling cycle, with each step length being 1 h. The PV output is predicted at each sampling point based on historical data for the current period.

where is the uncertain prediction of user n for the s + r period in period s; is the initial value of the uncertainty in period s; is the prediction increment of uncertainty in the period of s + t; r is the length of the prediction domain. In the intra-day stage, the influence of the prediction error is reduced by ES scheduling, so as to improve users’ trading income and relieve the operating pressure of the power grid.

Three typical days are selected, namely, a typical summer day (6 August), a typical transitional season day (2 October), and a typical winter day (31 December). Next, the transitional season typical day is taken as an example for discussion. The total predicted PV output of each community and the total initial load demand are shown in Figure 5, and the PV output of each user in a single community is the same. The ratio of shiftable load to non-shiftable load in each community is 0.5 to 0.2, so each community has the potential to achieve economic optimization through a load profile adjustment, and the capacity of the ES unit in each community is about 500 kWh. The upper limit of allowable trading power between the AESDC and the power grid at each step is 500 kW, the coefficient of power consumption loss is 0.2, and the lower and upper limits of real-time electricity price of the AESDC are and .

Figure 5.

Forecasted PV output and total load profiles of each community. (a) Forecasted PV output. (b) Total load.

On this basis, three scenarios are studied to verify the proposed strategy:

Scenario 1: Community users do not use shared ES equipment, no SESOs involved, and only configured PV equipment is used.

Scenario 2: There are no cooperation and energy interactions among communities, the SESOs within each community directly deal with the power grid for day-ahead scheduling, and cost sharing is only among community users at the lower layer.

Scenario 3: Communities cooperate as an alliance for ES sharing, using the leader–follower game for day-ahead scheduling and the Owen value method for the double-layer cost allocation strategy. Cost sharing is conducted on both the upper and the lower layers.

- (1)

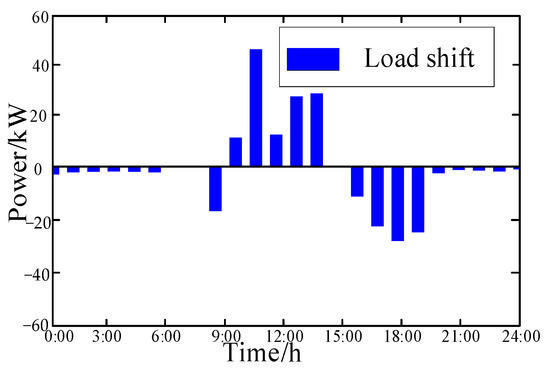

- Revenue analysis of the SESOS

Taking Community 1 as an example, the load shift in scenario 2 and scenario 3 is shown in Figure 6. The total load from 00–14:00 is larger than the original load demand, while the total load from 9:00–10:00 and 16:00–20:00 is smaller, which is due to load shifting to reduce energy consumption costs. We can also find that, to reduce the cost of electricity, a small amount of load shifting will be carried out at night, but the maximum amount of shift will be carried out at around 9:00–14:00 and 16:00–20:00, because they are the peak load time periods and the electricity price is also high. In order to reduce the energy consumption cost, this part of the load will be shifted as the first choice.

Figure 6.

Load shift in Community 1.

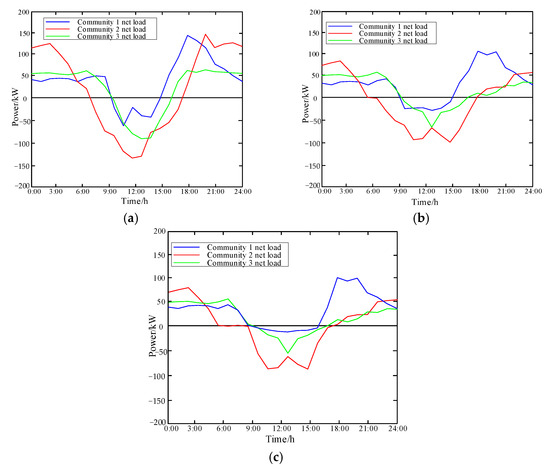

The net load profile of each community obtained in scenario 1 is shown in Figure 7a, and the net load of each community in scenario 2 is shown in Figure 7b. With the presented optimal scheduling strategy, the net load profile of each community in scenario 3 is shown in Figure 7c. The positive value in the figure indicates that there is an overall power shortage in the community, and the negative value indicates that there is a surplus of power generation in the community.

Figure 7.

The net load of each community in each scenario. (a) Scenario 1. (b) Scenario 2. (c) Scenario 3.

As seen from Figure 7a, when there are no Ess equipped, the PV output in each community only supplies its own load, and there is no SESO to guide users to respond to the demand. When PV generation exceeds the load demand, a large amount of it has to be discarded. As seen from Figure 7b, with the shared ES units, SESOs can guide users to actively participate in demand response, and users in various communities carry out load shifting to promote renewable consumption and obtain extra benefits. However, there are no energy Interactions among communities, and purchasing energy from the power grid is required, which increases total costs. In Figure 7c, it can be concluded that, under the ES sharing mechanism established in this paper, there are energy interactions among communities. Because the electricity price for inter-community interaction is lower than the TOU price of the grid, the energy consumption costs of each community are further reduced.

Since there is no SESO involved in scenario 1, its income is not analyzed. In other scenarios, the SESO income of the three communities is shown in Table 1. In scenario 2, the SESO earns profits mainly by adequate planning of its charging and discharging operation according to the energy consumption habits of each user and the TOU price of the grid. In scenario 3, with the scheduling of the AESDC at the upper layer, there exists a mutual benefit among the communities. When there is an energy surplus in one community, it can earn profits by selling it to SESOs in other communities. Through comparison, it can be seen that, under the trading mechanism based on the leader–follower game, the revenue of the SESO in Community 1 has increased by 26.69%, and that of Community 3’s SESO has increased by 13.69%. However, the income of the SESO in Community 2 has decreased, because the daytime load of Community 2 is low during the PV peak period. After participating in the community alliance, the surplus power needs to be preferentially sold to communities with a power shortage at a lower price than the PV on-grid price, which reduces the SESO’s income, but this result is in line with the group rationality of cost allocation. This will be explained in detail later.

Table 1.

Benefit analysis of the SESOs in each community.

- (2)

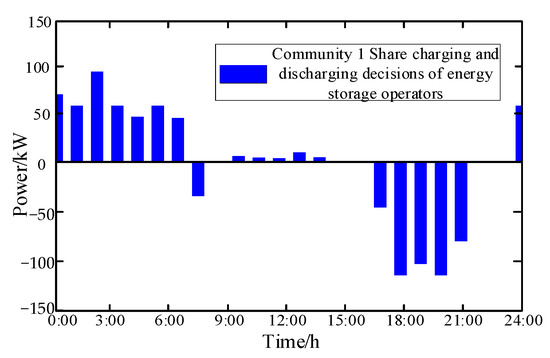

- Profit analysis of the AESDC at the upper layers

In scenario 3, the AESDC schedules the charging and discharging of the shared ES units in each community, issues the real-time electricity price of the alliance, and makes the power transaction plan with the grid at the same time. Taking the charge and discharge scheduling decision of the SESO in Community 1 as an example, the amount of power purchased and sold for each SESO is shown in Figure 8. The SESO stores energy between 10:00 and 15:00 when the PV generation is greater than load demands, and the SESO trades with each PV owner for energy storage. From 24:00 to 7:00, the SESO also instructs the ESs for charging, and the trading object at this time is the AESDC, because of the low electricity price during that period. Then the SESO instructs the ES to discharge when the PV output is low and the electricity price is at its peak (8:00–10:00, 17:00–21:00).

Figure 8.

Share ES charging and discharging instructions of the SESO in Community 1.

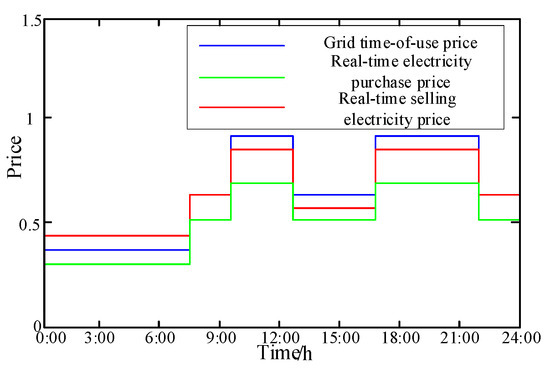

The real-time price of purchasing and selling electricity formulated by the AESDC is shown in Figure 9. The issued purchasing and selling price must be between the upper and lower limits of the benchmark electricity price, and the SESOs can reduce their energy consumption costs through energy transactions with the AESDC. The income of the AESDC in the whole dispatch cycle is CNY 98.46.

Figure 9.

AESDC purchasing and selling electricity price decision.

At peak load time, the TOU price of the grid is also at the peak. The AESDC reduces its own real-time electricity price to encourage the communities to purchase electricity. However, during the low electricity price period, the AESDC’s electricity price is higher than the TOU price in order to ensure its benefits. Since user loads are also in the low period at this time, the willingness of all communities to participate in the sharing mechanism will not be weakened. According to Figure 8, the real-time electricity price of the SESO is higher when discharging, while the real-time electricity price of the charging period is lower. It is also a reasonable measure from the AESDC’s perspective, because it can issue energy prices independently, and the pricing decision is more inclined to for its own profits. The AESDC is in the leading position in the leader–follower game, and the SESOs as followers will bear a certain loss of market efficiency when participating in the leader–follower game. However, the pricing of the AESDC also takes into account the influence of various SESOs in such a way that at noon when the PV power is abundant, the communities have more surplus power, and the demand for electricity purchased from the AESDC is greatly reduced, so the real-time electricity price is relatively low at this time, reflecting the original intention of the AESDC to guide the community SESOs for energy purchases.

- (3)

- Cost sharing results and analysis

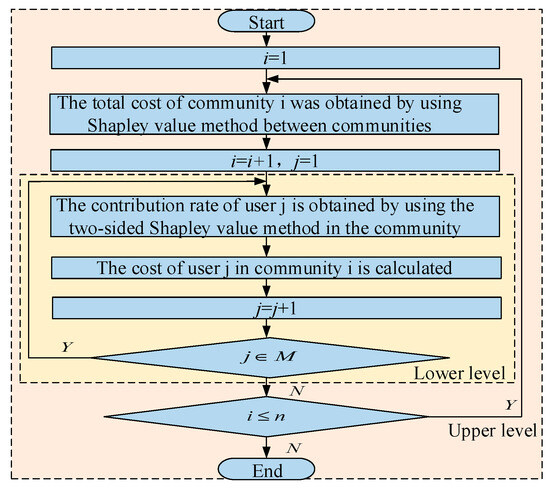

As there are multiple communities and users in this framework, the traditional Shapley value method will fall into a dimensional disaster and cannot achieve feasible solutions. Then the cost was allocated based on Owen’s value method. Table 2 shows the cost sharing results among communities.

Table 2.

Results of cost sharing among communities.

As seen from Table 2, according to the results of scenario 1 and scenario 2, the cost of each community in the shared ES mode is lower than that without the shared ES mechanism, due to ES’s flexibility in promoting renewable utilization and maintaining a power balance. According to the results of scenario 2 and scenario 3, the cost allocated to each community under the shared ES framework is better than that without cooperation. The cost allocation among communities is rational and is conducive to the stable operation of the ES sharing mechanism.

Taking Community 1 as an example and combining it with the results of scenario 2 and scenario 3 in Table 2, the cost redistribution scheme of community users at the lower layer is further analyzed. Table 3 shows the cost allocation results of the community users.

Table 3.

Cost sharing results for users within Community 1.

As seen from Table 3, although the PV output of each user is similar, the cost reduction degree of each user is different, which is because the load profile of each user is different, so the contribution to the community is different. Therefore, the cost allocation among users satisfies individual rationality and is also conducive to the practical application of the ES sharing mechanism.

- (4)

- Cost sharing analysis under scenarios of different typical days

An analysis is carried out under scenarios of typical days in the transition season, in summer and in winter. Table 4 and Table 5 show the cost sharing results among communities under the scenarios of typical days in summer and winter, respectively.

Table 4.

Cost sharing results among communities (typical day in summer).

Table 5.

Cost sharing results among communities (typical day in winter).

Under the scenarios of typical days in summer and winter, taking Community 1 as an example, the cost redistribution scheme of community users in the lower layer is further analyzed. Table 6 and Table 7 show the cost allocation results for users in the community during summer and winter.

Table 6.

Cost sharing results for users within Community 1 (a typical day in summer).

Table 7.

Cost sharing results for users within Community 1 (a typical day in winter).

Table 6 and Table 7 show that, under scenarios of typical days in winter and summer, the cost of each community with the shared ES mechanism is apparently lower than the cost of each community without ES sharing, and the cost allocated to each community is more reasonable and fairer than the cost without cooperating. The cost allocation among users is reasonable, and the cost for each user has been reduced. Therefore, it is concluded that the presented cost allocation method is practical in different scenarios.

- (5)

- Cost sharing analysis under different heuristic algorithms

Different heuristic algorithms are used to solve this optimization problem. Table 8 shows the cost sharing results of Community 1 under different algorithms.

Table 8.

The cost sharing results of Community 1 under different algorithms.

From Table 8, the presented PSO-HS algorithm results in the lowest costs in all scenarios. Moreover, the PSO-HS algorithm shows better performances in global convergence and robustness.

4. Conclusions

To enhance the operational stability of the power system with high renewable penetrations and further explore the economic benefits on the demand side, this paper proposes an ES-sharing mechanism with energy scheduling, trading, and cost allocation for multiple energy communities of EPs. The AESDC serves as the energy service provider of the multiple-community alliance and the SESOs serve as agents for communities of EPs who are responsible for the ES sharing mechanism. A double-layer optimal energy scheduling model based on leader–follower game is established, which is transformed into a single-layer model by using the KKT condition and then resolved by using the large M method and the PSO-HS algorithm. On this basis, the cost allocation model of alliance and community based on the Owen value method is established to solve the fairness of the benefit distribution and the privacy of users. Through case studies, the economy of the proposed ES sharing mechanism as well as the fairness and feasibility of the cost allocation strategy are verified. The features of the adaptation and robustness of the proposed strategy are verified by comparing the results under multiple scenarios of different seasons. The solution results of multiple algorithms show that the PSO-HS algorithm adopted in this paper is satisfactory in both computing speed and converging features.

In future works, the following will be focused on: (1) For the leader–follower game, the bidding game among various communities will be further considered. (2) For energy scheduling case studies in this paper, only the renewable output on sunny days is considered; in future works, fluctuations of the renewable DGs due to weather changes will be considered, which will bring more challenges to the scheduling strategies but will be more useful for justifying the functionality of the ES sharing mechanism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.B.; methodology, Y.G.; resources, W.L.; data curation, W.W. (Wenguo Wang) and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and W.W. (Wei Wang); writing—review and editing, Y.L.; supervision, U.B.; project administration, U.B.; funding acquisition, U.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Research Project of the Inner Mongolia Power (Group) Co., Ltd. (No. 2023-5-36).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the Inner Mongolia Power (Group) Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from the Science and Technology Research Project of the Inner Mongolia Power (Group) Co., Ltd. (No. 2023-5-36). The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Liang, Z.; Mu, L. Unified calculation of multi-energy flow for integrated energy system based on difference grid. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2022, 14, 066301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarne, Y.; Essadki, A.; Nasser, T.; El Bhiri, B. Experimental Analysis of Efficient Dual-Layer Energy Management and Power Control in an AC Microgrid System. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 30577–30592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, N.; Kang, C.; Kirschen, D.; Xia, Q. Cloud energy storage for residential and small commercial consumers: A business case study. Appl. Energy 2017, 188, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.K.; Rastegar, M. Distributed peer-to-peer transactive residential energy management with cloud energy storage. J. Energy Storag. 2023, 58, 106401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Du, E.; Fan, C.; Wu, Z.; Yao, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, N. A review and outlook on cloud energy storage: An aggregated and shared utilizing method of energy storage system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 185, 113606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Yang, L. Optimal bidding strategy and profit allocation method for shared energy storage-assisted VPP in joint energy and regulation markets. Appl. Energy 2023, 329, 120158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, C.; Low, S.H.; Wierman, A. An Energy Sharing Mechanism Considering Network Constraints and Market Power Limitation. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Esmaeilbeigi, R.; Charkhgard, H. The Utilization of Shared Energy Storage in Energy Systems: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 3163–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cha, W.; Zhou, S.; Wu, Y.; Huang, C. A Cooperative Game-Based Sizing and Configuration of Community-Shared Energy Storage. Energies 2022, 15, 8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steriotis, K.; Tsaousoglou, G. Real-time pricing in environments with shared ES systems. Energy Efficien. 2019, 12, 1085–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Cao, J.; Liu, M. Joint Optimization of Energy Storage Sharing and Demand Response in Microgrid Considering Multiple Uncertainties. Energies 2022, 15, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cao, X.; Zhang, S. Shared ES system for prosumers in a community: Investment decision, economic operation, and benefits allocation under a cost-effective way. J. Electr. Syst. 2022, 50, 104710. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Ouahada, K.; Rimer, S. Real Time ES Sharing with Load Scheduling: A Lyapunov-Based Approach. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 46626–46640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zheng, W.; Yu, Z.; Xu, Z. Optimizing Grid-Connected Multi-Microgrid Systems With Shared Energy Storage for Enhanced Local Energy Consumption. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 13663–13677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Yang, Y.; Cui, S.; Liu, X. A new ES sharing framework with regard to both storage capacity and power capacity. Appl. Energy 2022, 307, 118171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Su, X.; Qiu, Z.; Dong, Z.Y. Multi-timescale Energy Sharing with Grid-BESS Capacity Rental Considering Uncertainties. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 1326–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, S.; Qiu, J.; Tao, Y. Credit-Based Pricing and Planning Strategies for Hydrogen and Electricity ES Sharing. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yi, C.; Li, Z.; Xu, D. A Novel Shared ES Planning Method Considering the Correlation of Renewable Uncer-tainties on the Supply Side. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 2051–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Cai, C.; Xue, L.; Ma, Y.; Shen, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, L. Research on the optimization method of integrated energy system operation with multi-subject game. Energy 2022, 245, 123305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Guo, Q.; Huang, L.; Guo, H.; Lu, Y.; Tu, L. Microgrid source-network-load-storage master-slave game optimization method consid-ering the energy storage overcharge/overdischarge risk. Energy 2023, 282, 128897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, T.; Yan, H.; Wang, J.; Yan, Z.; Liu, W. Optimization Operation Strategy for Shared Energy Storage and Regional Integrated Energy Systems Based on Multi-Level Game. Energies 2024, 17, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Li, X.; Cheng, S. Energy Management Optimization of Microgrid Cluster Based on Multi-Agent-System and Hi-erarchical Stackelberg Game Theory. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 206183–206197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.T.; Fernandez-Blanco, R.; Kozdras, K.; Kaplan, J.; Lockyear, B.; Zyskowski, J.; Kirschen, D.S. Sharing Energy Storage Between Transmission and Distribution. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Zeng, B.; Zeng, M. Multi-timescale rolling optimization dispatch method for integrated energy system with hybrid ES system. Energy 2023, 283, 129006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Fu, Y.; Jia, Q.; Wen, X. Optimal dispatch of integrated energy microgrid considering hybrid structured elec-tric-thermal ES. Renew. Energy 2022, 199, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.V.S.M.; Vinay, K.S.S.; Chakraborty, P. Peer-to-Peer Sharing of Energy Storage Systems Under Net Metering and Time-of-Use Pricing. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 3118–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Zeng, J.; Lin, J.; Gao, C. Multi-stage distributionally robust optimization for hybrid ES in regional integrated energy system considering robustness and nonanticipativity. Energy 2023, 277, 127729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Da, C.; Zhou, W.; Wang, M. A control strategy for hybrid ES based on double-layer fuzzy controller integrated with second-ahead control thought. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2019, 11, 024104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, L.; Liu, C.; Song, F.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Che, B. Research on planning optimization of integrated energy system based on the differential features of hybrid ES system. J. Electr. Sci. 2022, 55, 105368. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Cheng, G.; Zhu, J. Collaborative Optimization to Enable Economical and Grid Friendly Energy Interactions for Residential Microgrid Clusters. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2023, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; He, X.; Tan, J.; Pan, Z.; Zheng, F. Stackelberg game-based optimal scheduling for multi-community integrated energy systems considering energy interaction and carbon trading. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 153, 109360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Chen, C. Hierarchical stochastic scheduling of multi-community integrated energy systems in uncertain environments via Stackelberg game. Appl. Energy 2022, 308, 118392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Han, R.; Wan, Y.; Qin, J.; Ran, L.; Ma, Q. Robust optimal energy management with dynamic price response: A non-cooperative multi-community aggregative game perspective. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 154, 109395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorov, D.; Panasetsky, D.; Tomin, N.; Karamov, D.; Zhukov, A.; Muftahov, I.; Dreglea, A.; Liu, F.; Li, Y. Toward Zero-Emission Hybrid AC/DC Power Systems with Renewable Energy Sources and Storages: A Case Study from Lake Baikal Region. Energies 2020, 13, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomin, N.; Shakirov, V.; Kozlov, A.; Sidorov, D.; Kurbatsky, V.; Rehtanz, C.; Lora, E.E. Design and optimal energy management of community microgrids with flexible renewable energy sources. Renew. Energy 2022, 183, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, H. Co-optimization method research and comprehensive benefits analysis of regional integrated energy system. Appl. Energy 2023, 340, 121034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Wang, J.; Shao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, W. Optimization of configurations and scheduling of shared hybrid electric-hydrogen energy storages supporting to multi-microgrid system. J. Energy Storage 2023, 74, 109420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.-P.; Keshtegar, B.; Seghier, M.E.A.B.; Zio, E.; Taylan, O. Hybrid and enhanced PSO: Novel first order reliability method-based hybrid intelligent approaches. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 393, 114730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Du, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, Z. Proportional Owen value for the coalition structure cooperative game under the incomplete information. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2019, 39, 2105–2115. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).