Abstract

The usage of fossil fuel in the energy sector is the primary factor for global GHG emissions, so it is crucial to better utilize RE sources. One way to do that is to hybridize RE technologies to make up for their deficiencies while enabling a more synergistic power production. This study utilizes such an approach to hybridize the KZD-2 Geothermal Power Plant (GPP) with CST and biomass in the southwest region of Turkiye. The main motivation is to address the two main issues of GPPs—excess turbine capacities happening over the operating years and decreasing performance during hot summer months—while also increasing the flexibility of KZD-2. A topping cycle of CST–biomass is added utilizing a PTC field as the CST technology and olive residual biomass combustion as the biomass technology. The hybrid plant is simulated on TRNSYS, and the energetic data show that it is possible to generate more than 20 MWe of additional power during sunny and clear sky conditions while also increasing the Capacity Factor (CF) from 69% to 74–76%. Moreover, the financial results show that the resulting LCOAE is 81.19 USD/MWh, and the payback period is five or nine years for using the YEKDEM incentive or the spot market prices, respectively.

1. Introduction

Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions are the main contributor to climate change, which, if not held to certain limits, will be detrimental to life on earth [1]. The main contributor to GHG emissions is the combustion of fossil fuels in the energy sector, which accounts for up to 75% of the total GHG emissions [2,3]. Renewable Energy (RE) technologies can significantly reduce GHG emissions by offering low/no carbon energy sources [3]. However, while many RE technologies show great promise, each RE technology faces one or more technical, economical, and/or environmental barriers to further market growth. As a strength, Geothermal Power Plants (GPPs) are typically designed to deliver baseload (i.e., continuous) power and deliver reliable electricity 24/7. However, commercial GPP technologies also face several challenges. In particular, the enthalpy of the geothermal brine at the production wellhead tends to degrade over the life of the production well due to the geothermal resources being extracted more quickly than they can be naturally replenished [4]. As the brine enthalpy decreases, the generated steam’s enthalpy at the turbine inlet also decreases as manifested by lower temperatures, pressures, and, most importantly, lower mass flow rates. Hence, as GPPs age, they often increasingly have steam mass flow rates that are lower than their design point, which leads to excess turbine capacities [4]. A second challenge with GPPs, especially those using Dry Cooling Towers (DCTs) as opposed to Wet Cooling Towers (WCTs), is their output tends to decrease during times of high ambient temperature due to higher condenser temperatures [5]. Since hot ambient temperatures tend to occur during the summer, the output from GPPs tends to be minimal on hot summer days. In contrast, solar energy resources tend to peak during the summer but are not available at night. Like geothermal, Concentrated Solar Thermal (CST) is a thermal energy source that uses a power block to convert heat into electricity. As an energetic opportunity, the combustion of biomass resources from agricultural waste streams can provide a thermal energy source that is flexible (i.e., it can be ramped up and down) and dispatchable (i.e., it can be turned on and off) without the need for thermal or electrical energy storage. As a challenge, agricultural waste streams tend to experience large seasonal variations that coincide with harvesting [6]. In summary, CST, geothermal, and biomass are all renewable thermal energy sources that have different strengths and weaknesses and use a power block to convert heat into electricity. The aim of this work is to develop and assess novel strategies to synergistically hybridize geothermal with CST and biomass to increase the performance of GPPs [7]. In particular, in this paper, one such hybridization scenario is presented, which involves the Kizildere-2 (KZD-2) Geothermal Power Plant (GPP), owned and operated by Zorlu Energy and located in the Southwest of Turkiye, with the addition of CST and olive residual (OR) biomass to exploit the strengths and compensate for the weaknesses of each technology and improve the overall performance of the existing GPP.

The issues with GPPs can then be summarized below.

- Issue 1: Excess turbine capacities.

- Issue 2: Performance decreases during summer.

The CST technology used in this study is the Parabolic Trough Collectors (PTCs), whereas the biomass source used is the local OR. The reasoning behind these selections is given later in the literature review. OR is found mainly between October and February when olives are harvested [8,9]. OR can also add additional flexibility as the combustion rate can be varied when needed. Issue 1 can be addressed by supplying additional steam flow to the GPP turbines to utilize the excess turbine capacity. Issue 2 can be mitigated using CST as the solar resource peaks during summer. Moreover, geothermal can also make up for the deficiencies of CST and biomass, hence creating a synergistic hybridization. The addition of CST and biomass to the system will be performed through a topping cycle to the existing KZD-2 so that the topping cycle can operate at higher temperatures and pressures, compared to KZD-2, and thus, it is a better exergetic use of these resources [7]. More details will be shared on the topping cycle approach in the Section 2. The synergistic hybridization and the benefits stemming from each RE technology are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Issues of each RE technology and the strategies to overcome those with hybridization.

The KZD-2 GPP is used as the case study in this paper as this paper is funded through the EU Horizon 2020 project, GeoSmart (Grant Agreement No. 818576); and through this project, access to high-quality and detailed data and insights regarding the operation procedures from the KZD-2 GPP was possible. Moreover, as the location of KZD-2 GPP has good solar and agricultural biomass resources [10,11], it is possible to implement the underlying idea in KZD-2 as a case study. KZD-2 integrates triple flash and binary technologies in a single GPP [12]. At its design point, the flash part produces 60 MWe, and the binary part produces 20 MWe of power. However, due to Issue 1, the total power output is reduced to approximately 55 MWe [12]. Thus, this study assumes that in each flash turbine, there is around 31% of excess turbine capacity. Non-Condensible Gases (NCGs) adversely affect the turbines and pipes [13], and since the NCG percentage of the High-Pressure Turbine (HPT) is 16.7 wt.% [12] as opposed to that of the Intermediate Pressure Turbine (IPT) 0.40 wt.% [12], the IPT is chosen for hybridization, which then feeds the Low-Pressure Turbine (LPT). A fuller explanation is given in Section 2.

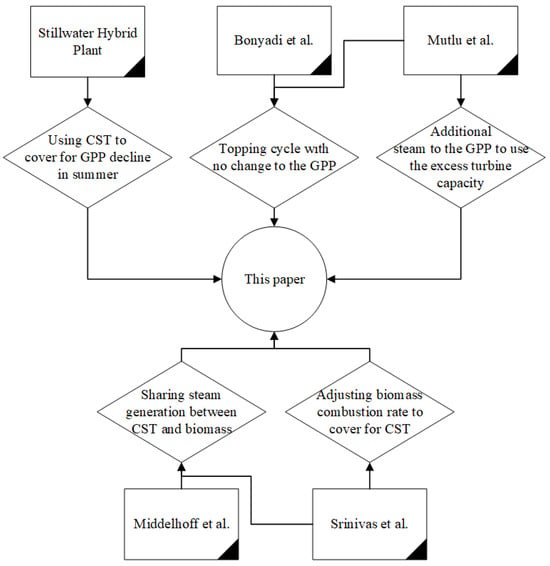

To the authors’ best knowledge, there is no previous study in the open literature on the triple hybridization of CST, geothermal, and biomass. The primary example of an actual hybrid solar and geothermal plant is the Stillwater plant in the US [14]. This hybrid plant uses solar resources to deal with Issue 2. Separately, Bonyadi et al. analyzed a PTC-powered topping cycle using a steam Rankine cycle coupled to an existing binary GPP and showed that this strategy enabled the hybridization of an existing binary GPP without requiring changes to the binary GPP power block [15]. The present work strongly builds on the work by Mutlu et al. that explored and assessed opportunities to hybridize geothermal with biomass [16]. In particular, the OR properties used in the present work are obtained from that paper. Moreover, Mutlu et al. showed that the OR-driven topping cycle can generate additional power and supply additional steam flow to a GPP bottoming cycle to utilize the excess turbine capacity. Srinivas et al. [17] and Middelhoff et al. [18] studied CST–biomass hybridization and showed a case where the CST and biomass parts generate steam concurrently, and those two steam flows run a shared steam turbine. A similar methodology is also used in this study. Srinivas et al. also showed that by varying the biomass combustion rate, it is possible to generate a variable steam generation that can be used when the solar resources are insufficient, which also adds additional flexibility and dispatchability to the system [17]. As a summary, the literature review and how they affected this paper can be found on Figure 1. In light of this literature review, a hybrid system is designed on the TRNSYS environment so that a hybrid CST–biomass topping cycle is utilized by using a PTC field as the CST technology and OR as the biomass resource. This topping cycle generates additional power using a steam Rankine cycle by generating steam from the PTC and OR simultaneously. Furthermore, the excess heat from this topping cycle and energy using biomass supplies additional steam flow to the IPT of KZD-2 GPP, serving as the bottoming cycle.

Figure 1.

The graphical summary of the literature review and how each item influenced this paper.

The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate how the hybridization of CST and biomass in an existing GPP can enhance its performance by providing additional power output and making up for its deficiencies. These deficiencies include the excess turbine capacities resulting from decreasing geothermal brine enthalpy with the operation years and the decrease in power output during hot summer months due to declining cooling tower efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper follows the following structure:

- Introduction

- −

- Problem definition is given.

- −

- Previous literature research is shared.

- Materials and Methods

- −

- The boundaries of the research due to the YEKDEM incentive are shared.

- −

- Integration of CST and biomass as a topping cycle is explained.

- −

- The detailed schematic of the hybrid plant is given.

- −

- The details of the share of steam generation between CST and biomass are shared.

- −

- The hybrid plant simulation model made in TRNSYS is explained.

- Results

- −

- The important parameters are given.

- −

- The energetic performances are shared.

- −

- The economic results are shared.

- Discussion

- −

- The results are discussed, and the shortcomings are shared.

- Conclusions

- −

- The main points from the paper are summarized.

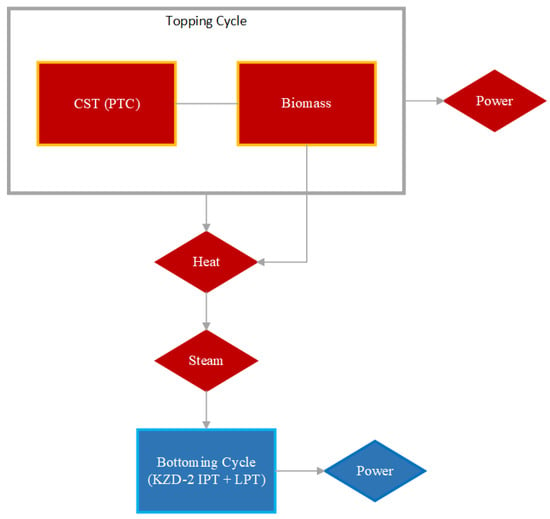

In 2005, Turkiye established YEKDEM as an incentive for domestic RE power plants [19]. YEKDEM is a power purchasing agreement that guarantees the purchase of power in US Dollars. This incentive is valid for all plants built before or in 2020 and lasts for ten years. Although the KZD-2 plant has completed its ten years under this incentive, this study also considers utilizing YEKDEM to obtain both perspectives of a power purchasing incentive and spot market prices. Plants benefiting from YEKDEM are allowed to add hybridizations with other RE sources up to 20% of the original power plant. Consequently, this study sizes the topping cycle to generate an additional 16 MWe (i.e., 20% addition 80 MW rated capacity). Moreover, by generating additional steam flow using the topping cycle, the excess turbine capacity of the IPT of KZD-2 will be utilized. Figure 2 shows the energy flow of the hybrid plant and the proposed integration. The red and blue colors represent the high and low operating temperatures for the topping and bottoming cycles, respectively.

Figure 2.

Energy flow diagram of the hybrid plant.

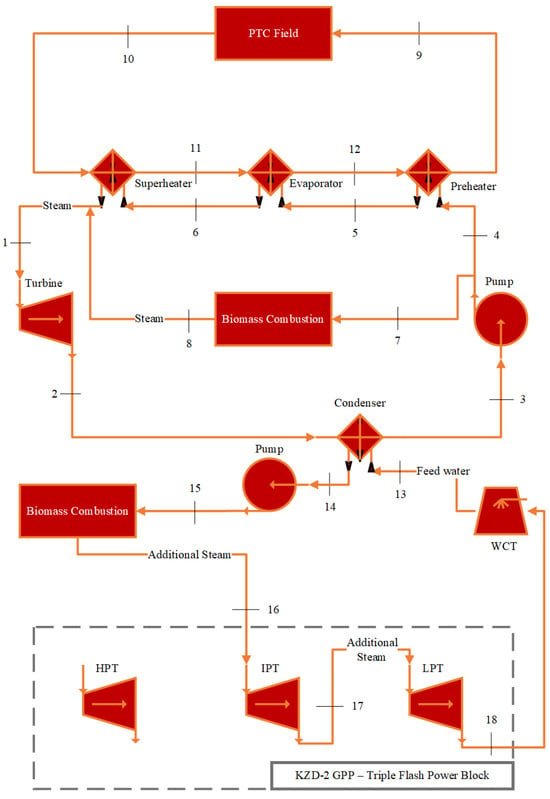

Figure 3 shows the detailed schematic of the hybrid plant. All elements above the dashed box are additional components added by this hybridization, with the exception of the WCT, which belongs to the KZD-2. The topping cycle powered by CST and biomass is shown in Figure 3, and the share of steam generation in the topping cycle is illustrated. The topping cycle pump adjusts the water flow rate to the CST or biomass parts. The condenser serves as the connection between the topping and bottoming cycles. The figure also shows that the exit of IPT feeds the LPT.

Figure 3.

Hybrid plant schematic.

The share of steam generation between CST and biomass is determined as follows. The CST field and biomass boiler are sized to generate sufficient steam to generate 10 MWe and 6 MWe power, respectively. However, to compensate for the variable solar resources, the biomass boiler is oversized by adding an additional 4 MWe. Specifically, OR is more abundant in the winter, and this additional 4 MWe will be utilized entirely in winter, but only 2 MWe will be used in summer. Lastly, during the night, the biomass will continue to operate to produce 10 MWe in winter and to produce 8 MWe in summer. This flexibility of biomass helps to strengthen its synergistic hybridization with CST.

TRNSYS Model

The hybrid model is built and simulated using TRNSYS software. TRNSYS is beneficial as it enables time based solutions crucial to CST plants. The PTCs used are Eurotrough ET-150 collectors with Therminol VP-1 as the Heat Transfer Fluid (HTF). The PTC field is designed based on the HTF being heated from 293 °C to 393 °C with an HTF mass flow rate that is sufficient to generate adequate steam at the design point [20]. The steam turbine in the topping cycle power block is designed using data from the literature with an inlet temperature and pressure of 370 °C and 1 MPa, respectively [20]. Moreover, the exit quality of the turbine is desired to be at least 99.9% [12]. The total power output design is 16 MWe, and the isentropic efficiency is chosen as 70%, as per the literature [21]. Hence, using Equations (1) and (2), the required steam mass flow rate for the total topping cycle is 25.56 kg/s. The steam mass flow rate for the CST part (10 MWe/16 MWe total) is 15.98 kg/s. On the other hand, the steam mass flow rate for biomass designed for 6 MWe + 4 MWe oversized capacity is again 15.98 kg/s.

The PTC field is sized based on the design steam mass flow rate of 15.98 kg/s. An H-type configuration is used for the field with 28 loops, each loop having four collectors, two in each row. To generate the steam at the turbine inlet conditions, this PTC field has an HTF mass flow rate at the design point of 202.75 kg/s. The actual HTF flow rate is adjusted based on the direct solar resources such that the HTF exits the PTC field at 393 °C by using a control signal with a coefficient based on the PTC area, the energy required to increase the enthalpy of the HTF, and the direct irradiance, using Equations (3) and (4), where the coefficient is found as 0.00025552.

The detailed specifications of the hybrid plant are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Properties of the hybrid plant.

3. Results

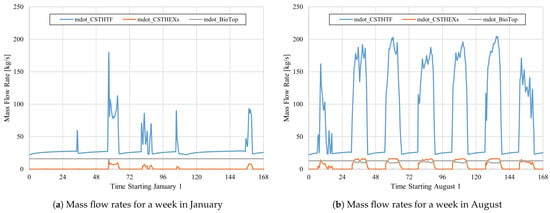

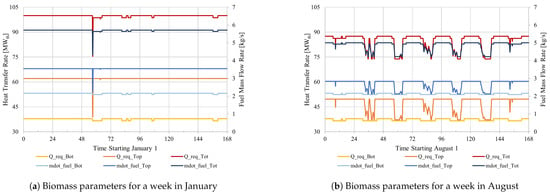

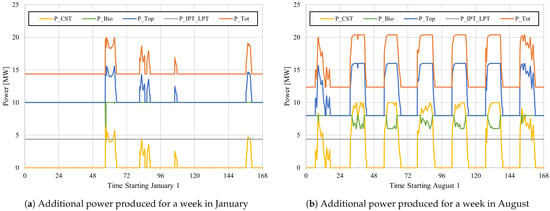

The simulation is run for the whole year, and two representative weeks are chosen to display the results for winter and summer to better capture the added value of this hybridization for two representative periods. The definitions of the parameters presented in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 can be found in Table 3 and Table 4. For Figure 5, the term refers to the mass flow rate through the topping cycle heat exchangers in the HTF side, i.e., states 9, 10, 11, and 12, refers to the mass flow through the topping cycle heat exchangers in the steam side, i.e., states 4, 5, and 6, and refers to the mass flow rate through the biomass combustor in the topping cycle, i.e., states 7, and 8.

Table 3.

The design point properties of the fluid streams.

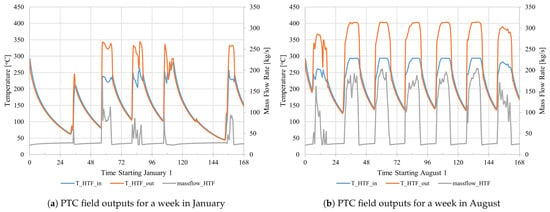

3.1. CST Field Results

Results for the CST field outputs as presented in Figure 4 for a week in the winter (a) and summer (b). Figure 4 shows the variation of HTF inlet and exit temperatures entering the PTC field. Also, Figure 4 shows the variation in the mass flow rate of the HTF. As explained above, the variation in the mass flow rate of the HTF with variation in the available solar resources is clearly shown. As solar resources are more limited in winter, the mass flow rates are lower. Still, the aim of raising the HTF temperature to 393 °C is possible even in the winter by reducing the HTF mass flow rate, which is important to maintain the system’s stability, especially because in the topping cycle, the steam generated by the CST will also be adjusted based on the mass flow rate of the PTC’s HTF. Figure 4 also demonstrates how, during the summer, the solar resources can compensate for the reduced OR resources and lower power block efficiencies as the PTC field increases the HTF enthalpy to adequate levels at the design temperature and mass flow rates.

Table 4.

The design point properties of the fluid streams.

Table 4.

The design point properties of the fluid streams.

| Item | Value | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCST | 10 | MWe | Additional power produced by CST alone. |

| PBio | 6-8-10 | MWe | Additional power produced by Biomass alone. Minimum—design—maximum operating points. |

| PTop | 16-18-20 | MWe | Additional power produced by the topping cycle. Minimum—design—maximum operating points. |

| PIPT,LPT | 4.37 | MWe | Additional power produced by using the excess turbine capacities of IPT and LPT. |

| PTot | 20.37-22.37-24.37 | MWe | Total additional power produced. Minimum—design—maximum operating points. |

| Qreq,Bot | 36.59 | MWth | Required heat input from the bottoming cycle biomass combustor. Minimum—design—maximum operating points. |

| Qreq,Top | 37.18-48.34-61.97 | MWth | Required heat input from the topping cycle biomass combustor. Minimum—design—maximum operating points. |

| Qreq,Tot | 73.77-84.93-98.56 | MWth | Required heat input from the biomass combustors. Minimum—design—maximum operating points. |

| fuel,Bot | 2.09 | kg/s | Required fuel combustion rate for the bottoming cycle biomass combustor. Minimum—design—maximum operating points. |

| fuel,Top | 2.12-2.76-3.54 | kg/s | Required fuel combustion rate for the topping cycle biomass combustor. Minimum—design—maximum operating points. |

| fuel,Tot | 4.21-4.85-5.63 | kg/s | Required fuel combustion rate for the biomass combustors. Minimum—design—maximum operating points. |

Figure 4.

The PTC field outputs from the TRNSYS model for the following: (a) A week in January; (b) A week in August.

3.2. Mass Flow Rate Results

Figure 5 presents the variation of mass flow rates for the CST HTF, steam mass flow generated by the PTCs, and the biomass in the topping cycle separately. Figure 5 is crucial to show the harmony between the CST HTF flow rate and the steam generated by the CST part. The steam flow rate is varied such that the generated steam is always at the specified turbine inlet temperatures of the topping cycle turbine. This helps ensure the lossless mixing of two steam streams by CST and biomass. Moreover, Figure 5 also shows an integral part of hybridization: how biomass makes up for CST when solar resources are not available. Figure 5b illustrates this more clearly by the decrease in biomass mass flow rate during the daytime. Outside these times, biomass was operating at the extra summer capacity. However, as solar resources become available, the need for biomass support decreases, and hence, the biomass-generated steam flow rate returns to its design point.

Figure 5.

The mass flow rates from the TRNSYS model for the following: (a) A week in January; (b) A week in August.

3.3. Biomass Results

Figure 6 show the heat and fuel consumption required from biomass both in the topping and bottoming cycles. Note that the overall level of fuel consumption rate in winter is higher than in summer as OR is found more during winter, and the levels are adjusted accordingly. In addition, in Figure 6b, the variations in biomass consumption can be seen more clearly. During the daytime, as solar resources are more available, biomass consumption is lower, and the flexibility of biomass is utilized.

Figure 6.

The biomass parameters from the TRNSYS model for the following: (a) A week in January; (b) A week in August.

3.4. Power Results

The plots in Figure 7 present the additional power generated by this hybridization relative to what is already produced by the KZD-2 GPP. In Figure 7a, on most days, the solar resources are not sufficient. Hence, the power output by the CST part is below the design points. However, some power was still extractable and vital to the overall power output. In winter, biomass mainly operates at its maximum extra capacity. On the other hand, in summer, CST power output is nearly at its design point, causing less load on biomass and higher overall power output. It is important to note that using the excess turbine capacity stays a priority and is utilized throughout the year, as the cost of using it is lower since the equipment is already primarily available and the YEKDEM incentive economically favors maximizing electricity production at all times, which is vital for RE plants still under the YEKDEM incentive.

Figure 7.

The additional power produced by this hybridization with data from the TRNSYS model for the following: (a) A week in January; (b) A week in August.

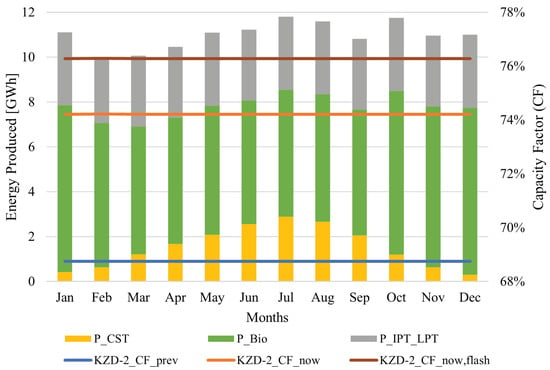

3.5. Annual Energy Yield Results

Figure 8 is the annual energy yield of the hybrid plant for each month. Figure 8 shows the increase in CST energy yield during summer months and, in contrast, the decrease in biomass energy yield during the same period. Moreover, the IPT excess turbine capacity utilization is shown to be constant. Figure 8 is essential in showing both resources’ seasonal variance of energy production. Moreover, Figure 8 also shows the Capacity Factor (CF) for the pre- and post-hybridization conditions for both the overall KZD-2 plant and only the flash part of KZD-2, as the binary part is not considered in hybridization. Figure 8 shows the CF increase with added hybridization, which will be discussed in the Section 4.

Figure 8.

The annual energy generated and the CF of this hybrid plant.

3.6. Economic Results

To assess the feasibility of this study, the Levelized Cost of Additional Energy (LCOAE) and the payback period are calculated. For LCOAE, Equation (5) [29] is used with the values in Table 5 and Table 6 adjusted to the year 2023 using the Chemical Engineering Plant Cost Index (CEPCI) [30]. The terms used in Equation (5) are CAPEXE: the total initial costs to build the hybrid part of the plant, OPEXE,t: the fixed and variable operation costs of the plant in year t, and Eann,t: the total energy yield from the hybridization in year t. The lifetime of both the CST and biomass components is taken as 25 years [20,28], as in the literature. Moreover, the discount rate is chosen as the global interest rate index at 8% (The case study involves the setting of Denizli, Turkiye. Turkiye is having an episode of very high inflation since 2017 that would disturb the calculations. As all the calculations have been made in Dollar terms, the price level changes in the local settings have been partially reflected in the calculations. Thus, the globally listed interest rate is assumed and used in this study for economic calculations) [31]. The results are presented in Table 7 and the resulting LCOAE is 81.19 USD/MWh.

Table 5.

Necessary plant parameters for LCOAE calculation.

Table 6.

Cost items in LCOAE calculation.

Table 7.

Plant final costs.

Another important parameter is the payback period. Two separate values are calculated for the payback period to display the difference between a support incentive like YEKDEM [19] and the spot market [35]. Equation 6 is used for both scenarios with values in Table 8, which also contains the YEKDEM prices. The results are presented in Table 9 and are discussed in the Section 4.

Table 8.

Parameters for payback period calculations.

Table 9.

Results of the payback period calculations.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study is to build a hybrid plant consisting of geothermal, CST, and biomass that addresses the issues of GPPs. The energetic results show that, Issues 1 and 2 are addressed positively by this hybridization strategy as follows. Issue 1, excess turbine capacity in GPPs stemming from decreasing geothermal brine enthalpy over the operating years, is addressed by using an additional steam flow obtained by utilizing heat from a CST–biomass hybrid topping cycle and resulting in an increase in the power output levels in the IPT and hence LPT. Moreover, Issue 2, the decreasing GPP performance during summer months, is addressed by increasing CST contributions during summer, when the solar resources peak. Furthermore, by adding biomass to the hybridization, the overall flexibility and dispatchability can be increased as it is possible to adjust the biomass combustion rate.

There are two assumptions regarding the hybrid plant that should be clarified. The first is the WCT of KZD-2 is assumed to be operating under its maximum capacity since the GPP is under performing. Thus, it is also assumed that the water utilized from the WCT to be supplied as steam to the IPT does not cause any water balance issues in the overall power plant. The second is that the intermediate components in the power cycle are omitted for this work. This includes the demisting or a similar purifying system before the turbine inlets to reduce the moisture and the associated issues in the turbine blades. Although this element can alter the power and efficiency values, the effect is assumed to be minimal, as the main concern of this work is the overall performance results of the hybrid power plant.

The energetic outputs show the synergistic combination of the three RE sources. OR shows an increase in utilization during winter (October to February), so its portion of power generation reaches 10 MWe levels day and night. During summer, however, as the OR becomes less available and solar becomes more available, the usage rate of OR decreases, and the power production from biomass becomes variable between 6 and 8 MWe. During the day, the biomass consumption rate decreases as desired when CST is utilized more. Also, the results show that, in summer conditions with sunny and clear skies, it is possible to generate additional power of more than 20 MWe while also utilizing the excess turbine capacity in the IPT. During these times, the biomass combustion rate varies between 4.2 to 5.8 kg/s, depending on the season and available solar resources. In addition, as the excess turbine capacity in the IPT is used, the CF also increases. Previously, the CF of KZD-2 was approximately 69%. while with the added benefits of this hybridization, the CF increases to approximately 74%, considering the KZD-2 as a whole, and to approximately 76%, considering only the flash part of KZD-2. This increase in CF is important to utilize the installed capacity in the KZD-2 plant that is not in use.

Economic analyses show that, with this hybridization, the LCOAE is 81.19 USD/MWh. For comparison, the YEKDEM incentive guarantees the purchase of energy from standalone GPPs at a rate of 105 USD/MWh and for standalone solar and biomass power plants at a rate of 133 USD/MWh [19]. Hence, the resulting LCOAE is promising for RE plants under the YEKDEM incentive. Moreover, this LCOAE is also a competitive value among other energy sources, such as residential and utility-scale PV and coal [36]. The payback period is considered for both YEKDEM and the spot market. With YEKDEM, the payback period is only five years, shorter than all standalone CST, geothermal, and biomass systems. On the other hand, with spot market prices, the payback period is nine years. This value is also significant and comparable to the payback period of the standalone systems, which vary between six to ten years [12,20,28]. Since the YEKDEM incentive is for ten years, utilizing YEKDEM for the first ten years and then the spot market is still economically viable and profitable. This also shows the importance of a supporting scheme for RE power plant investments.

5. Conclusions

This paper studied the hybridization of CST and biomass in an existing GPP. PTC technology and OR combustion are used for CST and biomass, respectively. The paper focused on a case study using Zorlu Enerji’s KZD-2 triple flash and binary GPP in Denizli, Turkiye. The GPP has had its power output decreased by around 31% due to brine enthalpy decreasing over the operating years, termed Issue 1 in this paper. Moreover, due to the low efficiency of WCT during summer months, the power output is lower in summer than in winter, termed as Issue 2. With this hybridization study, the effects of the intrinsic issues for GPPs, Issues 1 and 2, are mitigated using a topping cycle of hybrid CST and biomass that runs a steam Rankine cycle with shared steam generation. This share is adjusted so that each technology is utilized more during its peak availability. CST generates more steam during summer and during day hours, whereas biomass makes up for the intermittency of CST. This is even more so in winter and during night. In addition to producing additional power, the topping cycle also supplies the GPP with additional steam at the inlet conditions of IPT to utilize its excess turbine capacity as a result of Issue 1. With this hybridization, the results show that the excess turbine capacity of IPT and LPT can be utilized, and on top of this, more than 20 MWe of additional power can be produced in summer daytime. The LCOAE associated with this hybridization is 81.19 USD/MWh, with a payback period of five years for a plant under the YEKDEM incentive or nine years for a plant using the spot market prices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C. and D.B.; methodology, B.C., N.C. and S.R.; software, B.C.; validation, B.C.; formal analysis, B.C., D.B. and P.D.-G.; resources, D.B., U.H. and T.H.; data curation, B.C., U.H. and T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.C. and D.B.; writing—review and editing, D.B., N.C., P.D-G., U.H., T.H. and S.R.; visualization, B.C., D.B. and P.D.-G.; supervision, D.B. and P.D.-G.; project administration, D.B., P.D.-G. and S.R.; funding acquisition, D.B. and S.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is part of the project GeoSmart that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 818576.

Data Availability Statement

The data for the TRNSYS model built for the hybrid plant presented in the study are openly available at https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.13744496, accessed on 11 September 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Tuğrul Hazar and Ural Halaçoğlu were employed by the company Zorlu Enerji. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CEPCI | Chemical Engineering Plant Cost Index |

| CF | Capacity Factor |

| CST | Concentrated Solar Thermal |

| DCT | Dry Cooling Tower |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GPP | Geothermal Power Plant |

| HPT | High-Pressure Turbine |

| HTF | Heat Transfer Fluid |

| IPT | Intermediate Pressure Turbine |

| KZD-2 | Kizildere-2 |

| LCOAE | Levelized Cost of Additional Energy |

| LPT | Low-Pressure Turbine |

| NCG | Non-Condensible Gases |

| OR | Olive Residual |

| PTC | Parabolic Trough Collector |

| RE | Renewable Energy |

| WCT | Wet Cooling Tower |

References

- Effects —NASA Science. Available online: https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/effects/ (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Sector by Sector: Where Do Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Come from? Our World in Data. 2024. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/ghg-emissions-by-sector (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach—2023 Update. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Budisulistyo, D.; Wong, C.S.; Krumdieck, S. Lifetime design strategy for binary geothermal plants considering degradation of geothermal resource productivity. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 132, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Shen, J.; Duan, Y. Influences of climatic environment on the geothermal power generation potential. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 268, 115980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górecki, R.; Piętak, A.; Meus, M.; Kozłowski, M. Biomass energy potential—Green energy for the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olszytyn. J. Kones. Powertrain Transp. 2015, 20, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivarama Krishna, K.; Sathish Kumar, K. A review on hybrid renewable energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gözel, H. Zeytinde Hasat Zamanı ve Yöntemleri. Antepfıstığı Araştırma Dergisi 2014, 39, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Komili. Zeytin Nasıl Hasat Edilir? Hasat Yöntemleri Neler? l Komili Blog. Available online: https://www.komilizeytinyagi.com.tr/blog/zeytinyagi-rehberi/zeytin-nasil-hasat-edilir (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Solar Resource Maps of Turkey. Solar Resource Map © 2021 Solargis. Available online: https://solargis.com/resources/free-maps-and-gis-data?locality=turkey (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Saygılı, R. Türkiye Tarım Haritası. 2024. Available online: http://cografyaharita.com/turkiye-tarim-haritalari1.html (accessed on 23 May 2024).

- Serpen, U.; DiPippo, R. Turkey—A geothermal success story: A retrospective and prospective assessment. Geothermics 2022, 101, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokcen, G.; Yildirim, N. Effect of Non-Condensable Gases on geothermal power plant performance. Case study: Kizildere Geothermal Power Plant-Turkey. Int. J. Exergy 2008, 5, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimarzio, G.; Angelini, L.; Price, B.; Harris, S.; Chin, C. The Stillwater Triple Hybrid Power Plant: Integrating GeoThermal, Solar Photovoltaic and Solar Thermal Power Generation. In Proceedings of the World Geothermal Congress, Melbourne, Australia, 19–25 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bonyadi, N.; Johnson, E.; Baker, D. Technoeconomic and exergy analysis of a solar geothermal hybrid electric power plant using a novel combined cycle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 156, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, B.; Baker, D.; Kazanç, F. Development and Analysis of the Novel Hybridization of a Single-Flash Geothermal Power Plant with Biomass Driven sCO2-Steam Rankine Combined Cycle. Entropy 2021, 23, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivas, T.; Reddy, B.V. Hybrid solar-biomass power plant without energy storage. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2014, 2, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middelhoff, E.; Andrade Furtado, L.; Peterseim, J.H.; Madden, B.; Ximenes, F.; Florin, N. Hybrid concentrated solar biomass (HCSB) plant for electricity generation in Australia: Design and evaluation of techno-economic and environmental performance. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 240, 114244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YEKDEM. 2005. Available online: https://www.epdk.gov.tr/Detay/Icerik/3-0-0-122/yenilenebilir-enerji-kaynaklari-destekleme-mekanizmasi-yekdem (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC: World Bank; International Energy Agency (IEA); Mehos, M.; Price, H.; Cable, R.; Kearney, D.; Kelly, B.; Kolb, G.; Morse, F. Concentrating Solar Power Best Practices Study; Technical Report NREL/TP–5500-75763; 1665767, MainId:7049; OSTI: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.J.; Shapiro, H.N.; Boettner, D.D.; Bailey, M.B. Principles of Engineering Thermodynamics, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Luepfert, E.; Geyer, M.; Konsortium, E. Eurotrough Collector Qualification. Available online: https://elib.dlr.de/99768/1/EuroTrough_Ises2003_O523_final_.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Bergermann, S. Final Report: Extension, Test and Qualification of EUROTROUGH from 4 to 6 Segments at Plataforma Solar de Almería; Final Report ERK6-CT1999-00018; 2003; Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/docs/projects/files/ERK6/ERK6-CT-1999-00018/66682891-6_en.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Shagdar, E.; Lougou, B.G.; Sereeter, B.; Shuai, Y.; Mustafa, A.; Ganbold, E.; Han, D. Performance Analysis of the 50 MW Concentrating Solar Power Plant under Various Operation Conditions. Energies 2022, 15, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, V.E.; Kolb, G.J.; Mahoney, A.R.; Mancini, T.R.; Matthey, C.W.; Sloan, M.; Kearney, D. Test Results SEGS LS-2 Solar Collector; Technical Report SAND94-1884; Sandia National Lab.(SNL-NM): Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1994; Available online: http://large.stanford.edu/publications/coal/references/troughnet/solarfield/docs/segs_ls2_solar_collector.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Geyer, M.; Lüpfert, E.; Osuna, R.; Esteban, A.; Schiel, W.; Schweitzer, A.; Zarza, E.; Nava, P.; Langenkamp, J.; Mandelberg, E. EUROTROUGH—Parabolic Trough Collector Developed for Cost Efficient Solar Power Generation. In Proceedings of the 11th Int. Symposium on Concentrating Solar Power and Chemical Energy Technologies, Zurich, Switzerland, 4–6 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman Corporation Therminol VP-1 Heat Transfer Fluid; Eastman Corporation: Kingsport, TN, USA, 2022.

- Basu, P. Biomass Characteristics. In Biomass Gasification Design Handbook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, W.; Packey, D.; Holt, T. A Manual for the Economic Evaluation of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Technologies; Technical Report NREL/TP–462-5173, 35391; U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1995. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/biblio/35391 (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Maxwell, C. Cost Indices—Towering Skills. 2024. Available online: https://toweringskills.com/financial-analysis/cost-indices/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Macrotrends. World Inflation Rate. 1960–2024. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/WLD/world/inflation-rate-cpi (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Tranamil-Maripe, Y.; Cardemil, J.M.; Escobar, R.; Morata, D.; Sarmiento-Laurel, C. Assessing the Hybridization of an Existing Geothermal Plant by Coupling a CSP System for Increasing Power Generation. Energies 2022, 15, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedik, E. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences of Middle East Technical University. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkiye, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. In Biomass for Power Generation; Technical Report Volume 1; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2012; Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2012/RE_Technologies_Cost_Analysis-BIOMASS.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- EPİAŞ. GİP Ağırlıklı Ortalama Fiyat|EPİAŞ ŞEFFAFLIK PLATFORMU. Available online: https://seffaflik.epias.com.tr/electricity/electricity-markets/intraday-market-idm/idm-weighted-average-price (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Hemetsberger, W.; Schmela, M.; Cruz-Capellan, T. SolarPower Europe (2023): Global Market Outlook for Solar Power 2023–2027; Technical Report; 2023; Available online: https://www.solarpowereurope.org/insights/outlooks/global-market-outlook-for-solar-power-2023-2027/detail (accessed on 16 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).