Abstract

Through quantitative and qualitative analysis, this report conducts a thorough evaluation of the literature on the present progress in research on and the performance of net-zero-carbon cities (NZCCs). The quantitative analysis identifies ten major areas at this stage, and this analysis is followed by a systematic review of the dynamics and cutting-edge issues of research in the hot literature in this area. The systematic review reveals that the key points of NZCC transformation at this stage are research on zero-carbon buildings, urban paradigms, policies, economics, and renewable energy. Finally, based on the results of the previous analysis, to build the theoretical framework of NZCCs and combined with the sustainable development goals, future research directions are proposed, such as urban infrastructure transformation and low-carbon transportation, policy support and system reform, and digital transformation as well as coupling and balancing the relationships of various elements. In addition, cities need to develop evaluation indicators based on specific developments, and policy adaptability and flexibility are crucial for promoting cities’ efforts to achieve zero emissions. The current study provides targeted theoretical references and assistance for future policymakers and researchers, as well as advances and trends in the field of net zero carbon and associated research material from an urban viewpoint.

1. Introduction

Climate change is a global issue facing humanity that requires long-term and ongoing attention and research. In May 2023, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) released the Global Climate Status 2022 report, which stated that greenhouse gas concentrations are still gradually increasing, with heat-trapping greenhouse gases reaching record levels and the land, oceans, and atmosphere changing globally [1]. In 2021, the concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide reached record levels, as observed in the global composite (1984–2021), and the levels of all three greenhouse gases continued to rise in 2022. Meanwhile, according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the current global average surface temperature is approximately 1.2 °C higher than it was in 1880, well outside the normal range of fluctuations in the Earth’s average temperature over the previous 10,000 years [2]. In addition, the harm caused by global warming constitutes climate energy, and the potential economic losses are quite alarming. Thus, although earlier “carbon-neutral” actions have a broad social base, the global “carbon-neutral” vision is still highly uncertain because the energy low-carbon transition is a long-term, gradual, and complex process involving all aspects of the international political economy, and various types of pain and forms of backlash will be inevitable [3]. This uncertainty has caused many countries to fall into anxiety [4] and begin to expand their focus from the energy transition to a more integrated governance transition [5,6,7,8,9].

With the exploration of new governance approaches, the importance of cities in the governance process is gradually emerging. In terms of population, with the rapid growth of the urban population, energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions will increase, and as global urbanization continues, the proportion of urban dwellers is expected to rise from the current level of 54% to 68% by 2050, with new buildings, transportation facilities, and residential consumption resulting in higher energy consumption and carbon emissions. While generating more than 80% of the world’s GDP, they also consume 85% of the world’s total resources and energy consumption and emit greenhouse gases on the same scale, and cities are beginning to attract attention as an important area for addressing climate change. In addition, cities are the center of human activities, the largest consumers of energy products, and the main spatial source of carbon emissions, accounting for only 3% of Earth’s land area but generating more than 70% of carbon emissions. Cities are, therefore, central to the implementation of strategies to reduce carbon emissions and mitigate climate change, and to keep the global temperature rise to 1.5 °C or below, cities must achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century. In recent years, the impact of COVID-19 has caused major economic, health, and social setbacks around the world, and how to reconcile multiple issues and how to maximize the use of limited resources have become major challenges for countries. The need for and importance of urban transformation is gradually being recognized.

In practical ways, World Environment Day 2020 saw the official launch of the UN-backed Race to Zero global campaign, a leading coalition of net-zero initiatives for non-state actors, which was joined by 458 cities upon launch and has now expanded to 1136 cities worldwide. In January 2021, the World Economic Forum (WEF) Climate Action Platform released a study entitled “Net-Zero Carbon Cities (NZCC): An Integrated Approach” [10], which presented the first global framework for NZCCs and a comprehensive approach to achieving systemic efficiency gains. The study provides solutions to increase the resilience of cities to potential future climate and health crises [11]. From comprehensive planning to specific industries, the application of net-zero-carbon technology measures has the natural advantage of system integration, which can be achieved through comprehensive urban planning to optimize the combination of the spatial pattern, infrastructure, transportation system, and carbon sink space and bring into play the coupling effect of multi-dimensional carbon reduction, thus realizing the overall carbon reduction effect of the whole society. In this way, an increasing number of countries are taking active measures to build NZCCs [12]. Thus, how to encourage countries around the world to participate in the process of carbon emission reduction and how to achieve low carbon emissions in all aspects of production, life, and socio-economic development are common concerns among researchers today [13,14].

There are multiple differences between the focus and conclusions of earlier reviews and this study, with different emphases. First, in terms of the research direction, most existing articles focus on specific topics and countries, and reviews on the theory and practice of net-zero carbon under urban topics mainly focus on net-zero issues in the building sector [15,16,17,18], such as net-zero emissions and net-zero energy consumption in buildings [19,20,21] and accounting for carbon emissions during the whole cycle of building construction [22,23,24]. In addition to focusing on urban transportation [25,26,27] and industry [28,29,30], however, this study focuses on a comprehensive review of research across the full spectrum of NZCCs, adding policy and economic aspects to the topic because, to be used as a framework for climate action, NZCCs must be operationalized and measured as part of the ongoing activities of social, political, and economic systems, with buildings being only one piece of the urban transformation. Furthermore, the difficulty of harmonizing definitions in terms of the scope of net-zero-carbon research has been a key topic of discussion in the field, and the NZCC concept was first introduced in 2021 in the article “From Low- to Net-Zero Carbon Cities: The Next Global Agenda” by Karen C. In this article, the definition of an NZCC differs from the definition of a low-carbon city in that an NZCC is more transformative (over 80% reduction in fossil fuels) than a low-carbon city (over 20% reduction), calling for researchers to focus on transformative technologies and pathways for NZCCs. Thus far, however, the concept has not attracted sufficient attention from other researchers. Importantly, in terms of the definition of net-zero carbon, the term itself is only a concept and has meaning only when combined with specific evaluation indicators. Evaluation indicators also have certain application limitations. Therefore, the definition of the term should be accompanied by specific indicators within the scope of the study and should not be generalized.

In summary, this study aims to systematically and comprehensively summarize existing net-zero-carbon studies from an urban perspective and provide a reference basis for urban transformation. In terms of research methodology, carbon-neutral-related articles in the Web of Science (WoS) database from 2002 to 2022 were used as research objects in this paper. The collected literature was quantitatively analyzed by using the information visualization software CiteSpace 6.2.R4 and reviewed through a combination of quantitative and qualitative analysis. Additionally, a theoretical framework was built to finally propose future research topics based on four hot topics: the economy, paradigms, policy, and energy. The specific objectives of this study are as follows: 1. to quantitatively assess the NZCC-related literature from multiple perspectives to cluster existing research topics; 2. to analyze the dynamic evolutionary trend direction of the topics; 3. to conduct a literature review on the topic trend using qualitative analysis; and 4. to synthesize the results of the quantitative and qualitative analyses to construct a theoretical framework for this research topic and to propose future research topics to help researchers gain a comprehensive and up-to-date understanding of the field.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Processing

The literature data come from the WoS Core Collection-Citation Index, which includes the Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science (CPCI-S), the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED), and the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI). The first index was published in 2002, and neither of the two chemical indexes, i.e., Current Chemical Reactions Expanded (CCR-EXPANDED) and Index Chemicus (IC), yielded any relevant publications. As a result, the following search parameters were used for this paper: TS = “Net Zero Carbon” and timespan = 2002–2022. The search parameters and meticulous screening for extraneous publications resulted in 769 papers as of 31 December 2022. Regarding information, each chosen file includes the abstract, keywords, author, institution, and country, and the output file is renamed “download_*.txt”.

2.2. Research Methods

Visual analysis techniques are commonly employed in scientific research to assist researchers in swiftly extracting useful information from relevant literature and mapping knowledge networks. The major analysis software in this work is CiteSpace, an efficient and powerful scientometric visualization software developed by Dr. Chaomei Chen, a well-known information visualization expert [31,32]. Its original operation interface is illustrated in Figure 1. Scientometrics is a subfield of informatics that quantitatively examines scientific publications to understand the knowledge structure and developing trends in a research subject. The development state and trends of a subject area can be seen through its quantification and statistical analysis using literature-related information as input, thus boosting the scientific accuracy and precision of the subject study.

Figure 1.

Initial interface of the software CiteSpace.

Based on this software process, this paper integrates the research framework detailed in Figure 2, and it visualizes and analyzes the current state of knowledge in the field using knowledge mapping based on the scope of the research object, relevant departments, supporting measures, and key time points. Accordingly, it assesses the current state of knowledge in the field, explores global progress and hot issues, and identifies research trends.

Figure 2.

Analysis framework diagram.

3. Analysis of Developments in Research Fields

3.1. Countries and Regions Analysis

A preliminary understanding of NZCC was developed based on annual distribution statistics and a visual map of the thematic classification of publications. After using CiteSpace to filter out duplicate articles, we obtained a total of 769 papers on NZCC and the distribution of published articles per year (Figure 3). In terms of the publication trend of papers from 2002 to 2022, there are three phases: the first phase of the initial period of the study from 2002 to 2011 had a stable number of articles published; the second phase began in 2012, when the annual number of articles began to show an upward trend to 2018 to enter the third phase of the surge period; and the number of articles reached a peak of 163 in 2022.

Figure 3.

Publication trends on net-zero-carbon cities (2002–2022).

The change in the number of publications is an important measure of the development of a country’s research field. After visualizing the data through the software, it can be further visualized to analyze its influence and stage of publication. In CiteSpace, the keyword frequency (Count) indicates the size of keyword co-occurrence in the literature, and the higher the keyword frequency, the more important the node is in the field. Betweenness centrality is a measure of the importance of a node in the network, and when the value of betweenness centrality exceeds 0.1, the node is called a critical node. From the perspective of issuance volume, betweenness centrality is an important indicator to measure the comprehensive value and quality of its issuance volume. According to the data analysis, the countries are ranked in descending order of the number of articles issued, and combined with Table 1 and Figure 4, it can be seen that the country with the highest number of articles issued in the time frame of this paper is the United States (count: 212), followed by China (count: 163), England (count: 104) Canada (count: 79), Belgium (count: 68), Australia (count: 55), Italy (count: 55), and other countries. Among them, the United States (centrality: 0.25), China (centrality: 0.11), England (centrality: 0.14) and Spain (centrality: 0.16) have a higher level of influence and quality of articles, while Canada ranks fourth in the number of articles, but its centrality value is only 0.1 and its influence has to be improved.

Table 1.

Frequency of national article publication.

Figure 4.

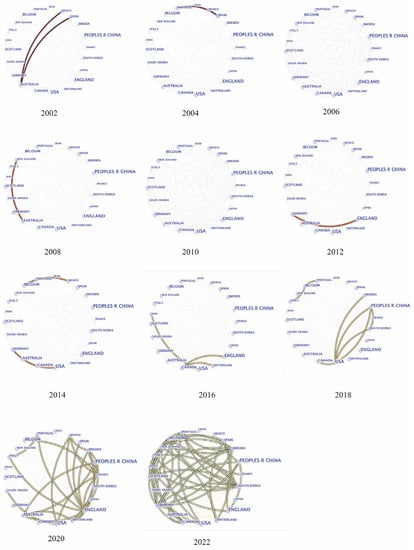

National research collaborations.

The software visualizes the impactfulness and cooperation relationship between its country and regional article issuance, which can reveal the development and change of cooperation in this research field. Figure 4 expresses the partnership between countries and the number of articles published in the last three years. The larger the country name is, the larger the number of articles published follows, and the size of the country name font size in the figure represents the frequency of articles published. The cooperation is expressed in terms of years and is repressed by the yellow linking line, and we can see from the graph, firstly, that the United States ranked first in terms of the number of articles issued, which not only has a high contribution rate of articles but also focuses on active cooperation between countries and is associated with most of them. Secondly, China, which is ranked second in terms of article volume, has a decreasing trend of inter-country cooperation, mainly showing intra-country cooperation, despite its high article volume. In order to further analyze the evolution of inter-country cooperation relationships, the relationship changes from red to yellow between 2002 and 2022 are shown in Figure 5 (with an interval of two years as a node), respectively. From the figure, it can be learned that before 2018, the countries were on a cooperation plateau, and the cooperation relationship was mainly concentrated between the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. From 2018 on, more countries began to cooperate in research, and research cooperation in this field increased significantly. However, the main cooperative relationships and centrality values are still concentrated between Belgium, Australia, and the U.S. Starting in 2021, the center of gravity of the main cooperatively active countries began to shift, evolving from a situation dominated by European and American countries to a diffusion type, with cooperative countries expanding to Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Singapore, Wales, etc.

Figure 5.

Change in national research partnerships 2002–2022.

3.2. Institutions and Author Analysis

A review of journals publishing research related to NZCC over time reveals a gradual expansion of journal categories and a recent interdisciplinary trend. While most of the early studies were published in journals in the environmental and atmospheric sciences, in recent years, journals in the energy and engineering fields have emerged and become dominant. In this case, as in Figure 6, the pink outer border indicates the potential intermediacy of the institution, with thicker borders indicating higher intermediacy of the node and greater academic impact of the institution. The lower left legend is divided by color to represent the change in publication year. Combining Table 2 with Figure 6, it can be seen that the volume of institutional publications is concentrated between 2020 and 2022, which is consistent with the total trend of publications in the above article. The top three according to the number are the University of Mons (52 articles), the City University of Hong Kong (50 articles), and the Utah System of Higher Education (23 articles).

Figure 6.

Institutional activity and frequency.

Table 2.

Top 10 most collaborative institutions.

The analysis of co-authors allowed the identification of collaborative cross-referencing relationships between researchers. In this paper, the authors were ranked according to the number of articles published from highest to lowest in the study years (Table 3), and the year in the table represent the first occurrence of a high period of cooperation by this author. the highest-producing author was Loakimidis, Christos S., whose 45 publications were published within the topic between 2002 and 2022. As well as analyzing the operational benefits of factors such as renewable energy generation, market prices, and electric vehicles, a model based on the Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) framework is provided to study the synergistic evaluation of EMS operations in buildings for each factor, culminating in a scenario-based simulation proposing a communication bi-directional energy management framework that can be used for smart buildings on university campuses.

Table 3.

Top 10 most collaborative authors in studies on net-zero-carbon cities.

3.3. Top-Cited Article Analysis

In this section, we analyzed the most cited articles in NZCC, and a total of 769 articles with valid information were screened. Given the large number of articles, Table 4 shows the highly cited papers with nodal significance obtained by combining the frequency of the words or phrases used in the cited literature and the citation frequency obtained from the cited literature. In addition, articles on urban transportation, infrastructure, and legislative management are also heavily cited, revealing that several of these topics have attracted considerable attention in reaching the goal of building NZCC and that the research focus has gradually shifted from the initial area of building energy to the overall city level. The specific research directions and progress details for each topic will be reviewed in the next section of the qualitative analysis of the literature.

Table 4.

List of the analysis of top cited articles.

3.4. Keywords Co-Occurrence Analysis

Keywords are used to identify the main ideas and main contents of articles, as well as to determine the frequency and presence of certain phrases in related literature, which helps to grasp the academic hotspots in the field. In this paper, we use each year as a time segment, and the threshold value is set to select the top 10 high-frequency nodes for each time segment. In the co-occurrence network, the larger the node is, the more frequently the node and the central node co-occur, i.e., the closer the relationship between them. By analyzing the literature from 2002 to 2022 (Figure 7), it can be seen that from 2002, the highest frequency according to the frequency mentioned is performance (frequency: 85), followed by city (frequency: 57), renewable energy (frequency: 45), and optimization (frequency: 45). In order to further identify trends and hotspots in the evolution of NZCC research, the “time zone” function of Cite Space was used to capture the time in this study, which was collected by dividing the year into segments, where each circle represents a keyword, the keyword is the year in which it first appeared in the analyzed dataset, and the line represents the association between the keywords. The keywords appear in chronological order on the corresponding timeline, and the larger the chronological wheel, the longer the appearance time. As can be seen from the figure, keywords such as performance, impact, and moderation began to appear on a large scale from 2002 to the present, and their influence is persistent. The year 2011 saw the first appearance of city and climate change under this topic, which is also the same trend as the highly cited literature in the previous section.

Figure 7.

Keywords timeline map.

With the help of CiteSpace, the keywords are clustered and analyzed (Figure 8). Each cluster is a keyword in the co-occurrence network, and each keyword represents a value, and the one with the largest value in the same cluster is the representative in that class. This means that the larger the size of the cluster (i.e., the larger the number of members contained in the cluster). Two metrics to look at when analyzing clusters are modularity (Q) and average silhouette (S). It is generally believed that a Q value in the interval (0,1), Q > 0.3 means that the delineated structure is significant; when the S value is above 0.5, the clustering structure is reasonable, and when it is more than 0.7, it is more convincing. In the resulting clusters, the average profile value of the weights S was 0.7731, and the modularity value Q was 0.5867, indicating that the clustering of keywords was successful and that they had a reasonable structure and a high confidence level. As shown in the figure, the keywords of the existing literature are divided into 10 clusters, in order from largest to smallest, as shown in the following.

Figure 8.

Co-occurred keyword cluster network.

- Cluster 0: “Net-zero building”. Keywords in the cluster are performance, design, consumption, and impact. This represents a focus on building performance and the economic benefits of sustainability.

- Cluster 1: “Climate Change Mitigation”. Keywords in the cluster are health, CO2 emissions, and mitigation, which represent the concern for the impact of climate change on cities, the environment, and human health.

- Cluster 2: “Carbon sequestration”. Keywords in the cluster are growth and columns, which represent the focus on soil carbon sequestration and construction materials to reduce human “carbon footprint”.

- Cluster 3: “Climate Change” Keywords in the cluster: policy, city, and consumption This cluster represents the focus on the impact of climate change on urban economies and the mechanisms of policy.

- Cluster 4: “Public transport”. Keywords in the cluster: balance, stability, gas, and behavior. This represents the focus on the topic of carbon input into the carbon mass balance and emission balance among various elements of the city.

- Cluster 5: “Smart Grid” Keywords in the cluster are boundary layer, radiation, and flows. This set represents the focus on the digital energy structure transformation and the development of a smart, low-carbon, safe, and efficient energy system.

- Cluster 6: “Model”. Keywords in the cluster: smart metering and energy storage system (ESS). This represents the focus on energy storage and releases devices and technological innovations in energy demand scenarios such as power systems and transportation.

- Cluster 7: “Insider Trading” Keywords in the cluster are time, costs, and firms. This represents a focus on the role of carbon markets as a policy instrument in their climate change policy portfolio and the development of the financialization of carbon trading markets.

- Cluster 8: “Amino acid”. Keywords in the cluster are absorption, thermal conductivity, and black carbon, which represent the new hotspot for research on new clean energy sources and environmentally friendly fuels as a balance between carbon emissions.

- Cluster 9: “Charging station”. Keywords in the cluster: systems and soil. This cluster represents a focus on energy-saving approaches and practices in urban public institutions and infrastructure.

4. Analysis of the Content of Research Trends

In this section, a full-text search of 769 articles based on clustering in the previous quantitative analysis is conducted, resulting in a summary of five research themes, including net-zero building, net-zero-carbon policies, urban infrastructure, energy and materials, and economic benefits, with further detailed literature reviews on each theme.

4.1. Net-Zero Buildings

4.1.1. Definition of Net-Zero-Carbon Buildings

Nearly 40% of global carbon emissions originate from building construction and operations. As the construction sector continues to grow, the global building stock is expected to double from its current level by 2050. Considering the long life cycle and carbon emissions of buildings, NZCCs are expected to mitigate the growing energy and environmental problems for the global fight against climate change [33]. Thus, emission reduction in the building sector has become crucial in recent years [34]. The NZCC concept has not been unified in terms of its definition since its development. However, in terms of their objectives, net-zero-carbon buildings are cheaper to operate, healthier, and more resilient than typical buildings and can bring considerable environmental, social, and economic benefits to cities and communities with rapid and cost-effective reductions in emissions and energy consumption.

How to define NZCCs and the elements and arithmetic models included in the concept are understood differently by researchers in different countries [35]. Net zero can refer to net-zero energy or net-zero carbon, but the exact definition depends on temporal and spatial definitions, and policymakers must define these boundaries when designing relevant policies. The main point of difference is the different key performance indicators (KPI) in the net-zero framework. Italian researchers defined NZCCs based on relevant national legislation [36], constructing a near-zero energy assessment model in which buildings must meet defined specific envelope characteristics and equipment performance. For example, facades must have high insulation, heating, and cooling performance, the global energy performance index must be lower than national standards, and systems that produce a specified share of energy from renewable sources must be installed to be certified as a net-zero-carbon building, with certain applicability restrictions. On the other hand, the United States and Singapore use energy delivered between buildings as an assessment indicator, while Norway and the United Kingdom use greenhouse gas emission data [37] as a criterion for defining a net-zero-carbon building. Regarding this issue, some researchers have shown that because of the lack of consistency between national net-zero definitions and international building life-cycle assessment standards, there is less transparency and credibility in achieving a net-zero greenhouse gas balance.

4.1.2. Net-Zero-Carbon Building Energy System

The current status of research on the planning and design of net-zero-carbon energy systems is as follows. First, the front-end of the energy system in terms of renewable energy treatment requires existing research to be divided into two categories: first, the use of renewable energy to provide air conditioning hot and cold water sources and domestic hot water [38], such as the use of solar water heating systems and air source heat pumps to provide domestic hot water and air-conditioning hot water as well as the use of ground source heat pumps as the hot and cold source of air conditioning equipment [39,40]. In addition, the use of temperature difference power generation is becoming one of the hot spots of new energy technologies that are now attracting attention [41,42,43], replacing traditional air conditioning systems with thermoelectric radiant ceilings (TE-RCs) and thermoelectric primary air handling units (TE-PAUs) to achieve more solar power generation. By evaluating the feasibility of applying the model’s annual energy balance, researchers learned that a solar photovoltaic-thermoelectric generator (SPV-TEG) has a 1.98% increase in energy production efficiency compared to a conventional photovoltaic (PV) system, generating an additional 514 kWh (or 23%) of renewable energy [44,45].

Second, in the end, part of the energy system, in addition to the initial research on the sharing model, the collaborative control model is becoming a new trend in research [46,47,48,49]. This model promotes the idea that additional renewable energy from a building can be efficiently shared with other buildings by improving the performance of grid-connected net-zero energy buildings (NZEBs) at the building complexity level. This renewable energy sharing eliminates simultaneous grid energy imports and exports in NZEBs, thus reducing unnecessary, high-priced grid energy imports and providing significant daily cost savings (i.e., 5–87.5%) compared to previous conventional models [50]. A neighborhood energy exchange model based on demand-side management (DSM) involving flexible demand-side control, renewable energy battery sharing, and forecast information exchange has also been proposed. The profit of each participant can be allocated by adjusting the compensation price in dynamic internal trading, using a dynamic internal trading model to analyze the cost savings of participants. The model also increases local self-sufficiency by 22.8% through power and information sharing [51].

4.1.3. Net-Zero-Carbon Building Assessment

In assessment models, a consensus has formed around the idea that the calculation methods published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have some application limitations when accounting for carbon emissions. Furthermore, energy statistics and emission inventories need to be based on local specificities, while attention should be paid to the scale of energy statistics when improving the accuracy of the data [52,53]. The main points of disagreement in the assessment models are divided into whether to use a life-cycle basis or an annual basis. First, some researchers argue that implicit carbon data for building materials and components are currently limited and that the possibility of data unavailability can exist in specific scenarios, which means that proxy products must be used in life-cycle assessments [54,55]. Even if partial data are obtained, the data have a high level of uncertainty. This impact will be repeated to a lesser extent throughout the life cycle of the building during repairs, maintenance, and any renovation program. The goal of construction must be to achieve zero life-cycle emissions from the building, not just operational emissions [56,57,58]. Therefore, in pursuing this goal, we need to look at key decisions in terms of their full life-cycle carbon impact. Second, it is also argued that the annual energy balance should be used as a key indicator evaluation unit [59,60,61,62,63] and constitute a multi-criteria NZEB renewable energy system (RES) design methodology in terms of grid stress and cost-effectiveness, which can compensate for the shortcomings of existing design models to achieve an efficient optimization of RES size under various uncertainties. Additionally, the overall performance of the methodology compared to traditional methods is improved by 44% compared to conventional methods.

Achieving the energy balance of an NVEB should also depend on the results that can be achieved under a combination of conditions such as design characteristics, occupant behavior, and weather conditions, which need to be integrated with local realities [64]. Hence, the assessment model has a certain range of applicability. For example, in a study on the assessment of building energy consumption in cold regions [65], it was noted that the renewable energy technologies involved in this climate zone are mainly applied to heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems. The frequency and type of application are also influenced by a variety of factors. Ultimately, relying on technology alone is not enough to achieve deep emission reductions in the building sector. Creating an enabling policy environment is an essential step. Most studies conclude by suggesting that energy policy is the main driver of the zero-energy building market and is a key enabler for achieving high efficiency in new construction projects [66,67].

4.1.4. Embodied Carbon

According to the World Green Building Council’s vision, by 2050, all new buildings, infrastructure, or refurbishment projects will achieve net-zero embodied carbon. Currently, there is a clear trend toward a reduction in lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions due to improved operational energy performance; however, it has been revealed that the relative and absolute contribution of so-called “specific” GHG emissions, i.e., emissions from the production and processing of building materials, is increasing [68,69,70,71,72]. In other words, the majority of building material production, transportation, construction, demolition, and waste disposal are high-energy-consumption and high-carbon-emission processes, and implicit carbon may be overlooked when considering the carbon footprint of buildings because it is hidden in the materials and production process rather than in the building’s use. As a result, lowering carbon emissions from the building materials business is critical to the whole construction industry’s low-carbon transition. There are three main perspectives to address this issue in existing research. The first is to reduce carbon emissions connected with material transportation [73,74,75,76]. Many nonprimary turnover materials have a poor recycling rate, such as formwork scaffolding in building construction, with waste rates ranging from 10% to 30%. Simultaneously, consideration should be given to the waste created during the conversion of previously acquired building materials into finished building goods, a process with a loss rate of 1% to 3%, both of which are typically transformed into construction trash on construction sites [77]. The use of in situ materials lowers the high costs of shipping raw materials and concrete components, as well as the carbon emissions generated during postprocessing. Second is the selection of low-carbon building materials, including low-carbon materials, carbon-neutral materials, and carbon-storage materials, to form a closed-loop process to increase the utilization and recycling rate of the material is considered by an increasing number of researchers as one of the most effective ways to reduce the implicit carbon emissions from building materials. Plants, which trap carbon as they develop and are eventually turned into building materials, account for the majority of current carbon storage materials. In addition, the use of recycled or recovered materials can help minimize the emissions associated with the production of new materials [78,79,80,81]. For example, it has been shown that changing from concrete and steel structures to wood structures with similar technical properties can reduce weight by 30% and carbon content by 50% [82]. Finally, for the entire building’s life cycle, parametric and modular design of the entire process is one of the approaches to increasing its efficacy [83,84]. This approach focuses on the multi-objective optimization of passive and active strategies, the creation of new workflows based on parametric design, and the assessment of specific and operational emissions throughout the design process by performing energy analyses and environmental impact analyses to assess building-specific and operational GHG emissions to minimize the implied GHG emissions of a zero-emission building. Additionally, using modular or prefabricated building techniques can optimize the use of materials to reduce waste that ends up in landfills, and designing buildings with a focus on durability can reduce the need for frequent replacements, increase adaptability to extend the life of the building, and promote better end-of-life management. In addition, the use of passive design strategies, such as better insulating and orienting buildings to take advantage of natural light and ventilation, can also reduce the need for energy-intensive mechanical systems with high carbon footprints. As a result, it is critical to examine the whole life cycle of a building, from material manufacturing and transportation through postoperation, with low carbon-reduction techniques. Simultaneously, market instruments should be utilized to direct low-carbon building material production, boosting synergistic carbon reduction and energy structure optimization in the building materials sector [85,86,87].

4.2. Net-Zero-Carbon Policy

Policy support is an important driver of project completion, on the one hand, by setting specific energy efficiency targets to guide future trends in cities and, on the other hand, by sending clear market and public interest signals to drive target setting and investment around energy projects. The literature suggests that the current problem is that the strength and form of policies can vary across regions, leading to differences in market incentives [88]. Additionally, the existing body of knowledge is insufficient to provide transformational policies commensurate with the sustainability challenge [89], i.e., there is a lack of rigorous analysis to inform urban climate policies and mitigation strategies. For intra-governmental systems, urgent and coordinated reform of policy systems is needed to expand the capacity for interdisciplinary research, adaptive governance, and organizational learning, as well as a deliberate co-evolutionary process based on adaptive governance and a feedback loop model (“envision, implement, evaluate”) to advance participatory action research and the effectiveness of government policies. For external structures, the lack of exploration of transformational lifestyle and behavioral change [90] requires clarification of the causes of short-term emission changes. Otherwise, current or future policies may not be consistent with emission commitments, causing problems such as stagnation in the development process.

The green policy transition aims to achieve a complete balance between environmental and economic activities and to accelerate the transition. Policymakers need to design and implement a policy mix that requires policy interventions at scale [91], resulting in broad benefits for the well-being of urban residents. It is also cross-sectoral and involves a range of stakeholders who must work together in a focused network that can create virtuous communication benefits through increased government-to-public cooperation, government-to-civil society organization exchanges, etc. [92,93].

Most scholars attribute the limitations of the current policy push to the lack of clear definitions of terms, which limits their use as quantitative targets to guide urban and energy planning decisions [94,95]. The terms eco-city, zero-carbon city, net-zero-carbon city, low-carbon city, and carbon-neutral city are often conflated in existing articles. Additionally, a multi-stakeholder process could be established, culminating in the creation of a certification body to clarify the system boundaries and emission boundaries of a given city for the development of a strategic process to monitor and manage carbon emissions at the city level.

4.3. Urban Form

4.3.1. Urban Green Space and Health

Urbanization-induced human activities are an important factor influencing climate change, and there is a need to look at ways to improve coping capacity not only from the environmental perspective but also from the perspective of the population to obtain synergistic benefits. The various risks to health posed by climate change, many of which act through long-term causal pathways, require action not only in health care but also in public health functions, including environmental and social determinants of health. It has been shown in the literature that from an externality change perspective, as urbanization accelerates, cities act as resource consumers and greenhouse gas emitters. If rapid urbanization focuses on short-term economic development rather than sustainability, this may impact humans directly and indirectly by undermining the environmental and social determinants of health, leading to development pathways that exacerbate global climate change, with widespread, largely negative impacts on global health and health equity [96,97], specifically health vulnerabilities, including heatwave and air pollution impacts, sea level rise and storms in coastal cities, and emerging infectious diseases, which influence some of the largest current global health burdens [98,99]. From an internal response perspective, it is most obvious that health can be simultaneously improved and greenhouse gas emissions reduced through policies related to transportation systems, urban planning, building codes, and household energy supply [100], and strategies to mitigate climate change in this way could avert thousands of deaths per year in the coming decades by shifting people to plant-based diets and increasing physical activity through active transportation modes [101]. Rapid action to develop a decarbonized economy and build resilience makes sense from health, human rights, environmental, and economic perspectives while improving housing conditions, clean water, noise reduction, reforestation, and more compact cities can also bring significant health synergies [102].

From an environmental perspective, considering how to reduce the urban heat island (UHI) effect in urban environments is a key point. In the current global warming scenario, temperature-related research is crucial, as air temperatures in urban areas are also rising due to global warming. One of the causes of UHIs is the conversion of naturally permeable surfaces into impermeable surfaces, which is often the cause of outdoor thermal discomfort in cities [103]. Existing urban modeling analyses have shown that urban parks are one of the best natural solutions to reduce UHIs in different seasons and are key to urban ecology and, more importantly, to climate mitigation and regulation in cities [104]. This is because as the damage caused by climate change escalates in the form of extreme weather, increasingly intense heat and stormy weather are becoming more frequent. Cities can keep their residents cool in the summer by planning and designing parks and green spaces and building adequate shade spaces, although the cooling effect of parks is diminished in windy weather [105,106]. Rain gardens, walls, cisterns, and other nature-based solutions can also be designed to capture rainwater, reduce flooding, and improve water quality. In this way, vegetated corridors, green parks, and water-absorbing low-lying areas can be integrated into the built environment to reduce the risk of flooding and high temperatures while improving biodiversity and carbon storage. Meanwhile, the effectiveness of green spaces in mitigating the UHI effect can be improved by optimizing the size and shape of parks when designing and planning urban parks [107,108,109]. It has been shown that urban thermal environments can be improved through orderly planning of green infrastructure and management of long-term performance, which can mitigate the heat island effect [110,111,112] and slow down the rate of urban sprawl, leading to some reduction in temperature [113,114,115].

Finally, the limitations of current research in this direction are the seasonal error of the model and the accessibility of the data. Although existing urban analysis models can realistically represent the seasonal cycle of surface fluxes, they are often subject to seasonal errors. Furthermore, regarding data, it is more difficult to obtain high-quality data in urban environments due to the limitations of measurement location and the representative spatial extent [116,117,118,119].

4.3.2. Public Transportation

Transportation is a key area for energy savings, emission reduction, and carbon reduction in cities. It is necessary to start from the travel structure, transportation demand, transportation means, and other aspects, use various related carbon reduction technologies, and adopt the means of optimizing the structure, adjusting demand, improving transportation means, and increasing green infrastructure to reduce the industry-wide carbon emissions of transportation until the balance of industry carbon emissions and carbon elimination is achieved [120]. With the current process of urban expansion and new city development continuing, urban clusters and metropolitan areas are being formed at an accelerated pace. Additionally, the trend of multi-modal travel combinations is becoming increasingly common as the spatial scope and radius of residents’ travel increase in conjunction with the development of concepts such as 15-min walking circles in compact cities [121].

How do we achieve a balance between energy consumption and production? In terms of research practice, the initial approach of reducing energy consumption by increasing the number of electric vehicles in cities [122] has evolved to today’s approach of identifying cost-effective decarbonization pathways at the city scale by developing energy system optimization models for decarbonizing electricity and transportation at the city scale. The current optimal decarbonization pathway in this direction consists of two successive phases: first, power sector decarbonization and, second, transportation. A supply-side-focused framework has been proposed. This framework needs to incorporate data on end-use equipment efficiency, building efficiency, urban land use regulation, seasonal 24-h profiles, and fluctuations. At the same time, the process of carbon reduction in the urban transportation sector requires two tools: technological innovation and financial innovation [123]. Technological innovations such as transportation mode innovation and transportation organization service models are used to improve travel efficiency and transportation organization efficiency. At the same time, the expansion of green capacity, research and development of carbon reduction technologies, and incentives for green behaviors also require financial empowerment to guide voluntary emission reduction.

4.3.3. Urban Transformation

Cities are a major source of economic growth, innovation, and opportunity for many of the planet’s future populations. If the scope of the net-zero-carbon simulation is placed in an urban context, the scale and level of opportunity will correspondingly increase exponentially. Researchers such as K. C. Seto in 2021 have shown that an NZCC transition is possible by analyzing practice data and policies in various cities [124]. Current perspectives on the transition in the literature fall into four main directions, starting with the conceptual transition, where some researchers suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent economic collapse could be seen as an opportunity for NZCCs [125,126], allowing city policymakers to reposition the economy and create a more walkable local city. A fresh perspective was taken to rediscover local parks and electric transportation opportunities, such as e-bikes, bike-sharing, and electric-assisted bikes.

The second is urban system transformation, where guiding cities to improve performance towards more sustainable urban infrastructure systems is a complex process that requires the support of multiple tools. Some scholars have suggested that carbon capture and storage technologies can be used for integration, collaboration, and awareness to optimize energy, water, and environmental systems [127]. However, others argue that at this stage, the prematurely decommissioned infrastructure that needs to be transformed and that is the most cost-effective will be the power and industrial sectors [128] rather than water and the environment.

The third is participation system transformation. Existing studies have demonstrated through statistical models the importance of urban professionals in developing actionable urban environmental policies and the positive impact that urban municipal energy managers and universities can have on urban climate action [129,130]. Researchers have proposed that staff could be hired or a department dedicated to environmental policy development could be created to improve their development of climate action plans for implementation. Finally, there is a holistic planning paradigm shift, where Miguel Amado et al. proposed an energy efficiency framework [131] that facilitates the integration of energy consumption, solar energy supply, and smart grids into the urban planning process by establishing smart cities and linking them to urban parameters. The framework is then applied to urban planning models to enhance urban sustainability.

4.4. Renewable Energy

In recent years, research on renewable energy from an urban perspective has mainly focused on the research scale and sources. First, at the system scale, to cope with climate change, countries around the world have proposed the concepts of “positive energy neighborhoods”, “net-zero energy zones”, and “sustainable neighborhoods”. Additionally, a series of green and low-carbon practices at the neighborhood scale have emerged, including the Positive Energy District (PED) in Lafleurier, France, the Potrero Power Plant Sustainable District (PPS) in San Francisco, and the new town of Tengah in Singapore. Most of these scholars believe that the PED concept is key to the transition of urban energy systems to carbon neutrality [132,133] and that potential social co-benefits (e.g., energy poverty reduction, community building, gentrification reduction) can be quantified by adopting the PED model, which can increase the ambition of projects and accelerate these solutions in existing regions to address the social problems mentioned above [134]. However, the limitations in the model’s current development lie in the viability and sustainability of the business model, which is more difficult to overcome than the existing technical limitations [135,136,137]. For example, the lack of capital financing, the high upfront investment, and the lack of information and awareness about costs and benefits require ongoing research at a later stage.

The second shift lies in the source of energy. After coal and oil, biomass as a renewable energy source contains a wide range of substances, among which agricultural residues and forest residues make up the largest share. Depending on the potential of different countries, different biomass resources are called renewable resources for fuel production. Biomass is of interest because it has net-zero CO2 emissions and is, therefore, very clean compared to other energy sources [138]. Scholars in Brazil have proposed that biomass production from non-food sources should be encouraged [139], and data analysis has verified that this energy source can yield an additional 7 million USD per month [140]. However, scholars in some countries, such as nations in Northern Europe and China, argue that electrified energy systems are more efficient. Nordic scholars have designed a more energy-efficient and cost-effective energy system in cities using heat pumps, solar heating, and electrolysis to achieve the lowest cost and CO2 emissions. In China, based on an analysis of the profitability of investments in PV power generation in 344 county-level cities, the results show that in 36.63% of the cities, power generation systems could be replaced by distributed SPV projects, further supporting the authors’ view that switching to electrified energy systems is a better long-term solution than biomass-based energy systems.

4.5. Economic Benefits

As the tipping point of the climate system approaches, considerable attention has been paid to the reform of the economic system [141,142,143,144]. In terms of the economic system, there are currently two main attitudes in the academic community. First, from a critical perspective, the existing economic system is considered more limited, with the state still pushing for more fossil fuel production and consumption and neglecting the financial economic system and its own role. This perspective argues that the way to shift different types of finance out of the carbon economy is through a transformational shift in production and governance, meaning that it needs to be based on a shift in power relations [145,146].

Some scholars are also open and positive, arguing that climate change and the internationally agreed-upon decarbonization of the global economy not only pose risks to the financial sector and the economy but also present opportunities in equal measure. First, while focusing on risks, mandate-driven central banks and financial regulators can improve the risk response of the financial system by understanding the dynamics and potential of green or sustainable financial markets to channel excess resources to sustainable projects. Additionally, financial markets can increase the scale and resilience of green finance by breaking out of niche markets [147], among other ways. Second, climate change can increase economic access while providing resilient support funding for the Green New Deal by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and improving the economic status of low-income households [148,149]. Third, carbon market trading liquidity can be improved by providing new scenarios for the application of blockchain technology by applying blockchain in a systemic framework as a transition tool. Researchers have proposed a novel blockchain-based peer-to-peer trading framework to trade energy and carbon allowances, a model that can directly incentivize the reshaping of consumption behavior to achieve a regional energy balance and carbon reduction [150,151]. Moreover, blockchain has the potential to promote the advantages of distributed and reduced transaction costs and can develop decentralized low-carbon incentives to address energy or carbon market efficiency [152,153,154]. In this way, a balanced relationship and sustainability between net-zero-carbon economic benefits and the energy transition can be ensured. On the other hand, the disadvantage of blockchain lies in its own energy consumption. Because its own system distributed technology architecture is very complex, all nodes need to synchronize information, which easily wastes power resources. Second, in terms of application, the necessary prerequisite for the application of blockchain is the establishment of a complete public infrastructure in the whole or at least part of the important scenarios of energy saving and carbon reduction [155,156], which often implies enormous construction costs in the early stage. Overall, the current problems faced are the lack of coordinated innovation management, multi-stakeholder innovation, and the construction of public infrastructure [157,158]. It is recommended that a holistic approach of blockchain be adopted in the whole life cycle of the entire systemic area of the energy economy to enhance the credibility of carbon data, which may help to interface and develop well with future digitalization, decentralization, and decarbonization areas.

5. Framework

5.1. Knowledge Framework

Based on the in-depth analysis of existing NZCC research, we see that there are various research dimensions and directions in this field, that new theories, challenges, materials, and methods are constantly being proposed as time and technology evolve, and that the disciplinary research hotspots are facing dynamic and complex changes, which, together with the research directions and contents, form the basis of NZCC research. At the same time, importantly, new concepts are constantly changing, from the initial “carbon-neutral cities”, “low-carbon cities”, eco-cities, and zero-carbon cities to the NZCCs of today, making it difficult for researchers to accurately distinguish between the terms used and confusing the semantics. Therefore, at this stage, it is necessary to summarize the hot trend of recent years, i.e., NZCCs, in a comprehensive manner. A comprehensive urban planning program and policy and institutional reform are needed to develop long-term and phased strategies to establish a holistic theoretical knowledge framework at the early stage of the development of this field to further advance the process of achieving the goal of NZCCs and to provide experience and references for future research.

This paper constructs a comprehensive theoretical knowledge framework for NZCCs based on four directions: the disciplinary scope, research focus, common citations, and potential topics of existing research (Figure 9). This knowledge framework clearly shows the evolution of collaborative networks, co-citation networks, and co-occurrence networks. It also depicts the research trends in the field, enabling the reader to obtain a quick overview of the research field of NZCCs. As seen from the framework, this paper performs collaborative, co-citation, and co-occurrence analyses to visualize the core elements of each analysis to aid and support the transition to an NZCC typology in an urban context.

Figure 9.

Knowledge framework of the net-zero-carbon cities.

5.2. Future Research Directions

This study constructs a comprehensive and visualized knowledge system of NZCCs, which is useful for theoretical studies of NZCCs. The results of our quantitative analysis visualize changes in NZCC theoretical research in time and space, which can help researchers gain a more comprehensive knowledge of NZCCs. The most meaningful results of this study are based on the summary of existing experiences after quantitative and qualitative analyses. The research trends are combined with the sustainable development goals (Figure 10). Thus, the proposed NZCC research directions provide insights for relevant researchers to identify future topics to promote the transformation of NZCCs in practice, with the core points of the topic listed below.

Figure 10.

Chart of existing trends and future directions.

- Focus on infrastructure low-carbon transformation, supporting service facility construction, top-level layout, and grassroots optimization for joint promotion.

- Focus on the digital development of smart cities in the context of the industrial structure and product structure special upgrades.

- Construct localized evaluation indicators in line with the development stage of each city, focusing on differentiation and flexibility.

- Pay attention to the driving force of policies for project realization, focus on relevant policy research, and clarify long-term and phased project goals.

- Improve the organizational system and promote system innovation and institutional mechanism reform. Pay attention to the problem of the disconnection of work between systems and the scope of application of systems, planning, and standards.

- Pay attention to the dynamic development relationship between urban systems. Promote the establishment of multi-disciplinary learning mechanisms and processing platforms.

- The study of the energy transition needs to consider technical and economic factors as well as the effectiveness and flexibility of transition coping mechanisms. Avoid the high carbon lock-in of fossil energy and the resulting risk of enormous capital sinking, idleness, and waste.

- Focus on the path of decarbonization at the city level, the proportion of each element, the inherent coupling and coordination relationship, and the balance of carbon emission relationships.

- Focus on the development of “green buildings” in addition to the simulation of scenarios such as the creation of ecological urban areas, low-carbon communities, and other research on spatial scale diversification development.

6. Conclusions

We reach some interesting and valuable conclusions in this work by using 769 documents acquired from the WOS database, conducting scientometric research on NZCCs, studying the literature, and referring to the results of the quantitative analysis. First, “environmental studies” is the most popular category in this research area, followed by “energy” and “construction and building technology”. The top three most productive countries in this study field are the United States, China, and England. The University of Cambridge in the UK, Princeton University in the US, and University College London in the UK are by far the most productive institutions. Furthermore, the most typical journals are Applied Energy, Energy and Buildings, and Energy. The most-cited article in the database is “Zero Energy Building: A Review of Definitions and Calculation Methodologies” by A.J. Marszal et al. (2011). Group 0, NZBs, is currently regarded as the hottest research trend, and its popularity has persisted since its debut in 2011. Furthermore, “policy”, “urban transformation”, and “renewable energy” have all become popular research topics in recent years. Utilizing the aforementioned analytical results, we explain the theoretical framework and recommend some priority problems for further research. Because cities play such an important role in the transition to a net-zero-carbon paradigm, national- and city-level managers tend to make recommendations and policies from a sectoral and functional standpoint, whereas practitioners typically make suggestions and conduct activities from an industry standpoint. As a result, the findings of this article are likely to give policymakers and participants essential inspiration for new paths and goals in this field, leading to more informed planning and decision making.

Finally, regarding the limitations of this paper, although the keyword “net-zero carbon cities” was used, the search results may not have included all possible results due to inconsistent definitions, and a comprehensive data cleaning process was not performed, which may have led to data duplication. While this issue may easily interfere with the analysis of microdata, our study focused primarily on microdata, reducing the impact of this limitation on the results obtained here. Second, the search conducted in this paper excluded literature analysis of reviews and conference proceedings. The WoS Core Collection database was selected, which may have missed some publications compared to the “All Databases” database.

Furthermore, future research will be based on the theme of city-level decarbonization by element share and intrinsic coupling coordination, as proposed in Section 5, combined with a theoretical framework to observe the best cost-effective decarbonization pathways at the city scale based on specific panel data to evaluate the current stage of decarbonization projects in designated cities and their effectiveness. Overall, we aspire to see cities as holistic systems capable of improving our future by modifying growth patterns to construct NZCCs.

Author Contributions

All the authors contributed extensively to the work presented in this paper. Conceptualization, Z.D.; methodology, writing—review and editing Z.D.; supervision, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pörtner, H.O.; Roberts, D.C.; Adams, H.; Adler, C.; Aldunce, P.; Ibrahim, Z.Z. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; p. 3056. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/figures/ (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- NASA. 2022 Fifth Warmest Year on Record, Warming Trend Continues. 2022. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-says-2022-fifth-warmest-year-on-record-warming-trend-continues (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, L.; Luo, Z.; Hou, K.; Du, X.; Lu, Y. Real-world carbon emissions evaluation for prefabricated component transportation by battery electric vehicles. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 8186–8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Genç, S.Y.; Kamran, H.W.; Dinca, G. Role of green technology innovation and renewable energy in carbon neutrality: A sustainable investigation from Turkey. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 294, 113004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulugetta, Y. Deliberating on low carbon development. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7546–7549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Ojala, M.; Salmela-Aro, K.; van den Broek, K.L.; Karasu, M. Climate anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental action: Correlates of negative emotional responses to climate change in 32 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, J.; Coutard, O. Urban energy transitions: Places, processes and politics of socio-technical change. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 1353–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, L.; Tian, X.; Hao, Y.; Wang, C. Urban energy transition in China: Insights from trends, socioeconomic drivers, and environmental impacts of Beijing. Energy Policy 2018, 117, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, M.; Marvin, S. Mediating low-carbon urban transitions? Forms of organization, knowledge and action. In Climate Change and Sustainable Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Net Zero Carbon Cities: An Integrated Approach. 2021. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/net-zero-carbon-cities-an-integrated-approach (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Hsu, A.; Logan, K.; Qadir, M.; Booysen, M.T.; Montero, A.M.; Tong, K.K. Opportunities and barriers to net-zero cities. One Earth 2022, 5, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswami, A.; Tong, K.; Canadell, J.G.; Jackson, R.B.; Stokes, E.; Dhakal, S.; Seto, K.C. Carbon analytics for net-zero emissions sustainable cities. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.; Sgouridis, S. Rigorous classification and carbon accounting principles for low and Zero Carbon Cities. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 5259–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, L.; Hua, J. Green construction for low-carbon cities: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1627–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, X.; Tatsuya, H.; Yuko, K.; Toshihiko, M. Achieving zero emission in China’s urban building sector: Opportunities and barriers. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 30, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirelli, D.; Besana, D. Moving toward Net Zero Carbon Buildings to Face Global Warming: A Narrative Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohene, E.; Chan, A.P.; Darko, A. Review of global research advances towards net-zero emissions buildings. Energy Build. 2022, 266, 112142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emodi, N.V.; Okereke, C.; Abam, F.I.; Diemuodeke, O.E.; Owebor, K.; Nnamani, U.A. Transport sector decarbonisation in the Global South: A systematic literature review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 43, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirinbakhsh, M.; Harvey, L.D. Net-zero energy buildings: The influence of definition on greenhouse gas emissions. Energy Build. 2021, 247, 111118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Too, J.; Ejohwomu, O.A.; Hui, F.K.; Duffield, C.; Bukoye, O.T.; Edwards, D.J. Framework for standardising carbon neutrality in building projects. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruparathna, R.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. Rethinking investment planning and optimizing net zero emission buildings. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2017, 19, 1711–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, L.; Meena, C.S.; Raj, B.P.; Agarwal, N.; Kumar, A. Net Zero Energy Consumption building in India: An overview and initiative toward sustainable future. Int. J. Green Energy 2022, 19, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Skye, H.M. Residential net-zero energy buildings: Review and perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 142, 110859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrany, H.; Chang, R.; Soebarto, V.; Zhang, Y.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A.; Zuo, J. A bibliometric review of net zero energy building research 1995–2022. Energy Build. 2022, 262, 111996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, T.O.; Hassan, A.M.; Arab, Y.; Hussein, H.; Khozaei, F.; Saeed, M.; Ahmed, B.; Zghaibeh, M.; Beitelmal, W.; Lee, H. The Compactness of Non-Compacted Urban Developments: A Critical Review on Sustainable Approaches to Automobility and Urban Sprawl. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Z.; Yiji, L.; Zahra, H.O.; Zhibin, Y. Review of heat pump integrated energy systems for future zero-emission vehicles. Energy 2023, 273, 27101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Science mapping: A systematic review of the literature. J. Data Inf. Sci. 2017, 2, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalo, M.; Christos, I.; Paulo, F. On the planning and analysis of Integrated Community Energy Systems: A review and survey of available tools. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4836–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, K.; Sovacool, M.I.; Jeremy, H. Industrializing theories: A thematic analysis of conceptual frameworks and typologies for industrial sociotechnical change in a low-carbon future. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 97, 102954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Jiang, K.; Chen, S.; Jiang, W.; Liu, J. Zero CO2 emissions for an ultra-large city by 2050: Case study for Beijing. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 36, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace: A Practical Guide for Mapping Scientific Literature; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Leydesdorff, L. Patterns of connections and movements in dual-map overlays: A new method of publication portfolio analysis. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2014, 65, 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Pei, Z.; Yongjun, S. A multi-criterion renewable energy system design optimization for net zero energy buildings under uncertainties. Energy 2016, 94, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clift, R. Climate change and energy policy: The importance of sustainability arguments. Energy 2007, 32, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, V.; Eike, M.; Markus, L. From Low-Energy to Net Zero-Energy Buildings: Status and Perspectives. J. Green Build. 2011, 6, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpino, C.; Mora, D.; Arcuri, N. Behavioral variables and occupancy patterns in the design and modeling of Nearly Zero Energy Buildings. Build. Simul. 2017, 10, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torcellini, P.; Pless, S.; Deru, M.; Crawley, D. Zero Energy Buildings: A Critical Look at the Definition (No. NREL/CP-550–39833). National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL). 2006. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/883663 (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Daniel, S.; Aoife, H.W.; Manan, S.; Sushanth, B.; Ben, J.; Manish, D.; Ryan, S.; Yann, G.; Arild, G. Comparative review of international approaches to net-zero buildings: Knowledge-sharing initiative to develop design strategies for greenhouse gas emissions reduction. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 71, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Z.; Paweł, O.; Jiří, J.K. Renewable energy systems for building heating, cooling and electricity production with thermal energy storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 165, 112560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niveditha, N. Optimal sizing of hybrid PV–Wind–Battery storage system for Net Zero Energy Buildings to reduce grid burden. Appl. Energy 2022, 324, 119713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Huang, G.; Sun, Y. A collaborative control optimization of grid-connected net zero energy buildings for performance improvements at building group level. Energy 2018, 164, 536–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Dai, X.; Liu, J. Building energy-consumption status worldwide and the state-of-the-art technologies for zero-energy buildings during the past decade. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhao, C.Y.; Tian, Y. Review on thermal energy storage with phase change materials (PCMs) in building applications. Appl. Energy 2012, 92, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Homoud, M.S. Performance characteristics and practical applications of common building thermal insulation materials. Build. Environ. 2005, 40, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Pu, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J. A study on thermoelectric technology application in net zero energy buildings. Energy 2016, 113, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Niu, X.; Li, Y.; Lan, J. Recent progress in thermal energy recovery from the decoupled photovoltaic/thermal system equipped with spectral splitters. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Jeon, J.H.; Kim, S.K.; Cho, C.; Park, J.H.; Kim, H.M.; Nam, K.Y. Cooperative control strategy of energy storage system and microsources for stabilizing the microgrid during islanded operation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2010, 25, 3037–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Han, Q.L.; Ning, B.; Ge, X.; Zhang, X.M. An overview of recent advances in fixed-time cooperative control of multiagent systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 2322–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenzer, M.; Ay, M.; Bergs, T.; Abel, D. Review on model predictive control: An engineering perspective. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 117, 1327–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.A.; Faisal, M.; Ker, P.J.; Begum, R.A.; Dong, Z.Y.; Zhang, C. Review of optimal methods and algorithms for sizing energy storage systems to achieve decarbonization in microgrid applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 110022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqian, Z.; Xin, J.; Gongsheng, H.; Alvin, C.K. Coordination of commercial prosumers with distributed demand-side flexibility in energy sharing and management system. Energy 2022, 248, 123634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Shan, Y.; Huang, Q.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Hubacek, K. Assessment to China’s Recent Emission Pattern Shifts. Earth’s Futur. 2021, 9, e2021EF002241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodagar, B.; Fieldson, R. Towards a low carbon construction practice. Constr. Inf. Q. 2008, 10, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Nordhaus, W. Estimates of the social cost of carbon: Concepts and results from the DICE-2013R model and alternative approaches. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2014, 1, 273–312. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/676035 (accessed on 27 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K.Y.G.; Statz, C.; Chong, W.K.O. Carbon emission modeling for green building: A comprehensive study of methodologies. In Proceedings of the ICSDC 2011: Integrating Sustainability Practices in the Construction Industry, Kansas City, MI, USA, 23–25 March 2011; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, T.; Prakash, R.; Shukla, K.K. Life cycle energy analysis of buildings: An overview. Energy Build. 2010, 42, 1592–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, L.F.; Rincón, L.; Vilariño, V.; Pérez, G.; Castell, A. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and life cycle energy analysis (LCEA) of buildings and the building sector: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 394–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, I.; Hestnes, A.G. Energy use in the life cycle of conventional and low-energy buildings: A review article. Energy Build. 2007, 39, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncaster, A.M.; Pomponi, F.; Symons, K.E.; Guthrie, P.M. Why method matters: Temporal, spatial and physical variations in LCA and their impact on choice of structural system. Energy Build. 2018, 173, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Masi, R.F.; Gigante, A.; Vanoli, G.P. Numerical analysis of phase change materials for optimizing the energy balance of a nearly zero energy building. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, D.B.; Hand, J.W.; Kummert, M.; Griffith, B.T. Contrasting the capabilities of building energy performance simulation programs. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesco, R.; Pekka, T.; Åsa, H.; Mona, G.E.I. Low-energy residential buildings in New Borg El Arab: Simulation and survey based energy assessment. Energy Build. 2015, 93, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, W.; Wei, F.; Lan, W.; Shilei, L. A comprehensive evaluation of zero energy buildings in cold regions: Actual performance and key technologies of cases from China, the US, and the European Union. Energy 2020, 215, 118992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Skye, H.M. Net-zero nation: HVAC and PV systems for residential net-zero energy buildings across the United States. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 177, 605–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayman, M.; Ala, H.; Kai, S. Fulfillment of net-zero energy building (NZEB) with four metrics in a single family house with different heating alternatives. Appl. Energy 2014, 114, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Max, T.; Benjamin, D. Decarbonizing power and transportation at the urban scale: An analysis of the Austin, Texas Community Climate Plan. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 43, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röck, M.; Saade, M.R.M.; Balouktsi, M.; Rasmussen, F.N.; Birgisdottir, H.; Frischknecht, R.; Passer, A. Embodied GHG emissions of buildings–The hidden challenge for effective climate change mitigation. Appl. Energy 2020, 258, 114107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]