Abstract

Drying via solar energy is an environmentally friendly and inexpensive process. For controlled and bulk level drying, a greenhouse solar dryer is the most suitable controlled level solar dryer. The efficiency of a solar greenhouse dryer can be increased by using thermal storage. The agricultural products dried in greenhouses are reported to be of a higher quality than those dried in the sun because they are shielded from dust, rain, insects, birds, and animals. The heat storage-based greenhouse was found to be superior for drying of all types of crops in comparison to a normal greenhouse dryer, as it provides constant heat throughout the drying process. Hence, this can be used in rural areas by farmers and small-scale industrialists, and with minor modifications, it can be used anywhere in the world. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the development of solar greenhouse dryers for drying various agricultural products, including their design, thermal modelling methods, cost, energy, and environmental implications. Furthermore, the choice and application of solar photovoltaic panels and thermal energy storage units in the solar greenhouse dryers are examined in detail, with a view to achieving continuous and grid-independent drying. The energy requirements of various greenhouse dryer configurations/shapes are compared. Thermodynamic and thermal modelling research that reported on the performance prediction of solar greenhouse dryers, and drying kinetics studies on various agricultural products, has been compiled in this study.

1. Introduction

Globally, in 2018–2019, fruit production was estimated to be 392 million tons, and vegetable production was estimated to be 486 million tons. Due to post-crop or post-harvest handling, nearly 30–40% agricultural produce is damaged or spoiled [1]. Among developing countries, India is the second-largest producer of vegetables and fruits; however, 35% of the crop is nevertheless lost post-harvest. The factors responsible for these losses include improper handling, poor production methods, and inadequate storage facilities. This results in the approximate annual financial loss of 104 million US dollars [2]. Spoilage mainly occurs due to microorganisms, as a high percentage of water is present in fruits and vegetables.

To keep the agricultural product preserved, the removal of moisture content is essential. The most economical process of food preservation involves drying foodstuffs in the sun, a method which has been practiced for 5000 years. The dehydration of agricultural products takes place due to heat treatment, either via a natural or artificial process. The heat can be generated via a natural method, such as solar radiation, or via an artificial method, such as the generation of electricity by burning fossil fuels. The entire world faces the issue of an energy crisis due to the limited availability of fossil fuels and the rapid increase in the consumption of oil and natural gas. Electricity is either unavailable to many farmers or too expensive. Moreover, the supply of electricity is exceptionally erratic; therefore, dependence on its supply is an unreliable prospect for many farmers. To run the farm machinery on fossil fuels, on a large scale, is not financially prudent and it can significantly impede the management of the farm [3].

One of the most important and all-encompassing phenomena is global warming, as it affects flora and fauna across the globe. The diverse ways in which humans are broadly affected by global warming include rises in air temperature, rises in sea level, and changes in climate. These disturbances occur due to the high melting rates of snow/ice, the distinct differences in geographical distribution norms, and the extinction of animals and plants. The environmental system is degrading due to the ill effects of greenhouse gases [4].

The weather pattern is therefore affected. There is an uneven distribution of rain, and some parts of the world are left dry and arid. Renewable energy sources are the ultimate solution to deal with these unavoidable problems. The sun is the ultimate source of renewable energy, and it is the best renewable energy source to capitalize upon. Solar concentrators, solar collectors, and solar dryers utilize solar radiations for drying applications; farmers and small stakeholders find these to be the most flexible options for obtaining energy [5].

1.1. Solar Drying

Since ancient times, the solar drying method has been used by mankind to dry fruits, seeds, plants, wood, meat, fish, and other agricultural and animal products. The sun provides a free and renewable energy source for drying purposes. Several scientific research methods have been applied in order to improve solar dryers for the preservation of forest and agricultural products. Solar radiation is used to evaporate the moisture that is present in the product during the natural sun drying process; nevertheless, there is seasonal variation with regard to the intensity of sunshine, which can cause uneven drying, thus resulting in the under-drying and over-drying of products [6]. Solar energy is used to heat the air, and this heated air is able to flow over the product, thereby removing the moisture and carrying away the vapor released from the product. The equipment that harnesses the solar energy to heat the air and dry the food products has acquired the term, “Solar Dryer”. The solar dryer mitigates the limitations of natural sun drying by improving the quality of the dried product. During the solar drying process, solar energy is used as the only energy source, or it is augmented by adding hybrid energy sources. Natural or forced convection airflow can be generated by the solar dryer [7].

During the drying process, the product may be subjected to preheated air as a result of convection, or the product may be directly exposed to heat due to solar radiation. The vaporization of moisture occurs as a result of the heat being absorbed by the agricultural product. Moisture is vaporized from the moist surface of the product when the heat is absorbed. This vaporization increases the temperature of the agricultural product, which results in the enhancement of the agricultural product’s vapor pressure in comparison with the surrounding air. The ability of moisture to diffuse into the crop’s surface from the interior depends on the size of the product, the moisture content, and the nature of the product. Solar drying usually occurs when agricultural products are available in abundance. Solar drying technologies provide an opportunity to sell dried products during off-season periods. Moreover, the products can be sold at higher prices during harvesting seasons because of its superior quality.

There are various types of solar drying technologies, with each having their own merits and demerits. The use of the solar dryer depends upon the metrological conditions of the crop. The rate of drying inside the solar dryer is always higher in comparison with the drying rate in the sun. Additionally, the crops that are dried inside the solar dryer contain a higher amount of Vitamin A and Vitamin C. The solar dryer also minimizes crop losses that are caused by rain and dirt. The solar dryer is mainly categorized into three modes that are based on drying (i.e., open, direct, and indirect drying) [8].

1.1.1. Open Sun Drying

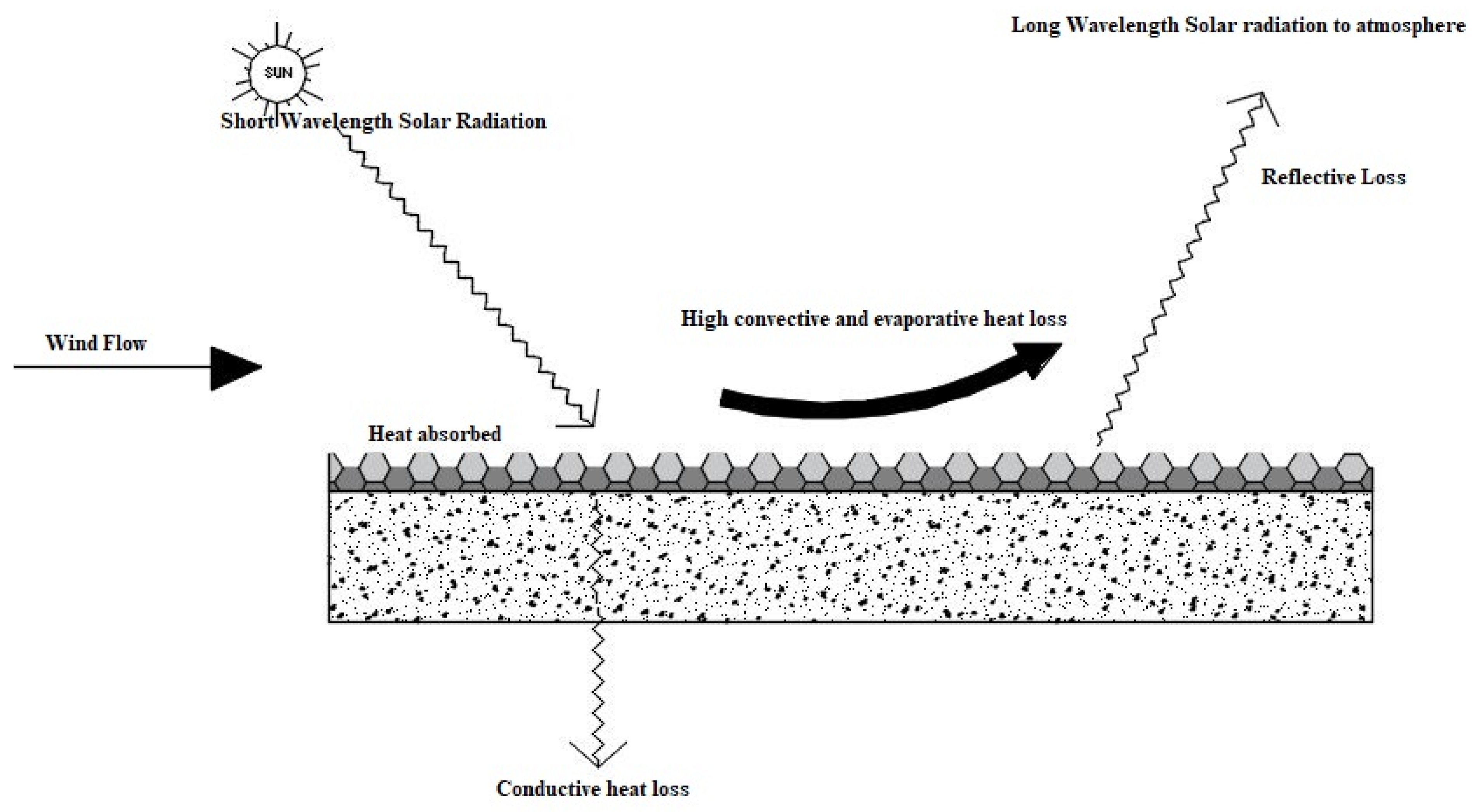

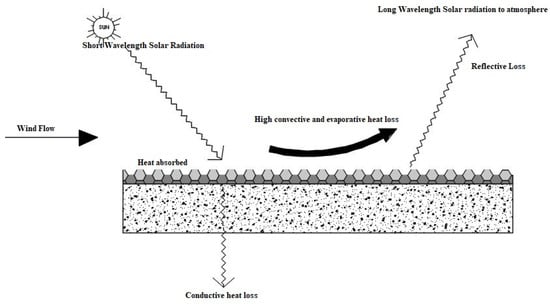

With open sun drying, the short wavelength of solar radiation descends on the rough surface of the agricultural crop. The surface absorbs part of the short wavelength radiation, depending on the color of the exposed crop, and the remaining part is diffused. There is an increase in the temperature of the crop due to the absorption of solar radiation as it converts solar radiation into thermal energy; this results in the loss of long-wavelength radiation from the surface of the agricultural product to the ambient surroundings through moist air.

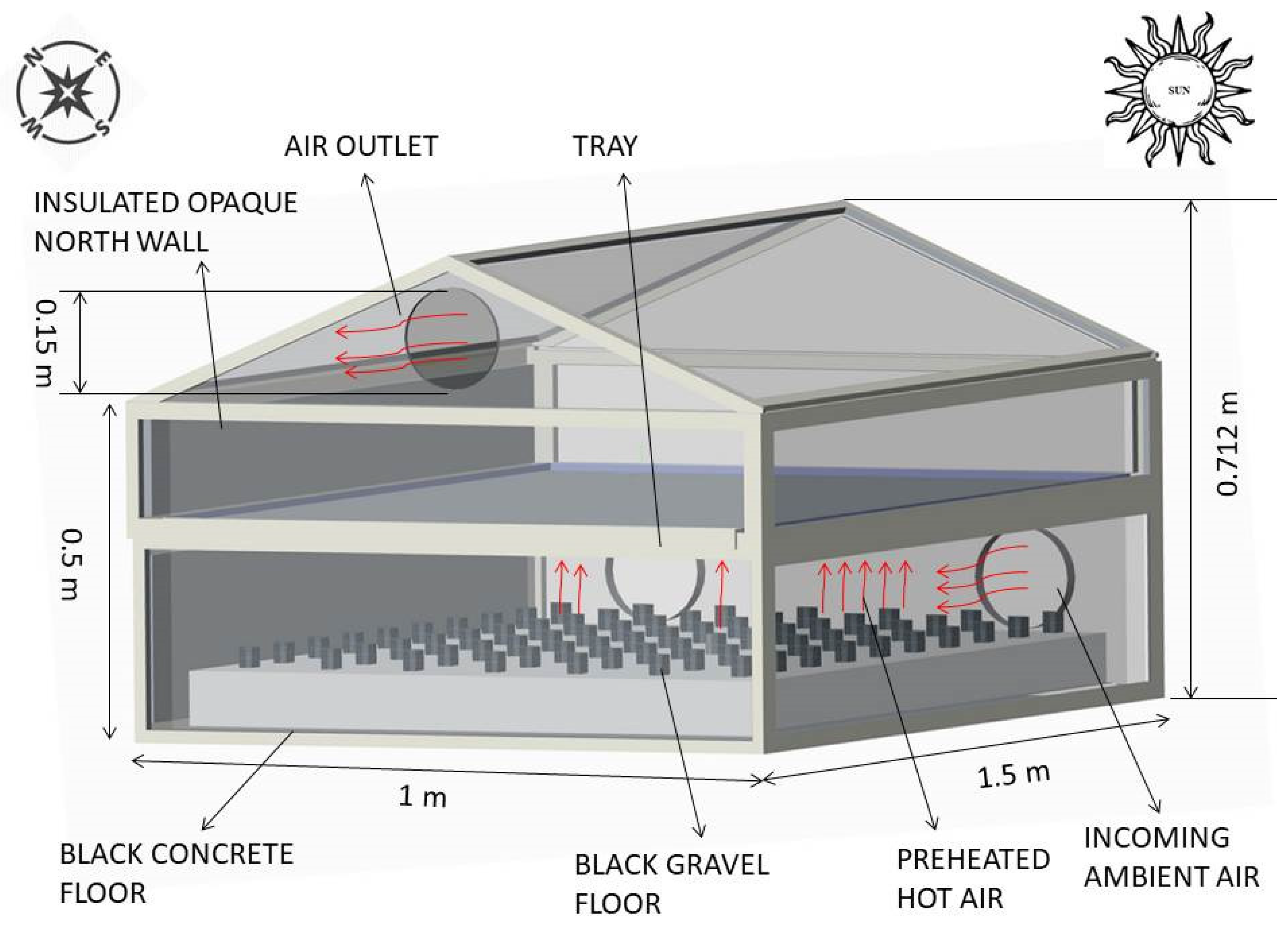

Wind blowing over the surface of the crop also adds to the convective heat loss. The crop is dried as the evaporation of moisture takes place in the form of evaporative losses. Figure 1 illustrates the open-air drying process.

Figure 1.

Open sun drying [9].

Open sun drying is the cheapest and simplest method of drying; however, many drawbacks are associated with this method. The prominent economic concern regarding this method is that open sun drying fails to maintain a standardized international quality, therefore, products obtained from this method remain out of the global market [10]. With the realization that the quality of the product obtained from open sun drying is deficient, a technically improved solar energy utilization method emerged; this is called solar or control drying [11].

1.1.2. Direct Solar Drying

Solar radiation incidents on the transparent glass cover are easily transmitted into the cabinet of the dryer. Most of the radiation is transmitted into the cabinet of the dryer, and the remaining part of the radiation is reflected back. The crop surface reflects part of the radiation, and the remaining part is absorbed by the crop surface, which thus increases the temperature of the crop. The heated crop starts emitting long-wavelength radiation, but the long wavelength radiation cannot escape into the atmosphere due to the presence of the glass walls and cover; thus, the presence of both the incidental and reflected radiation within the chamber further increases the temperature to be higher than that of the crop [12]. Figure 2 illustrates a direct solar drying system.

Figure 2.

Direct solar drying [9].

1.1.3. Indirect Solar Drying

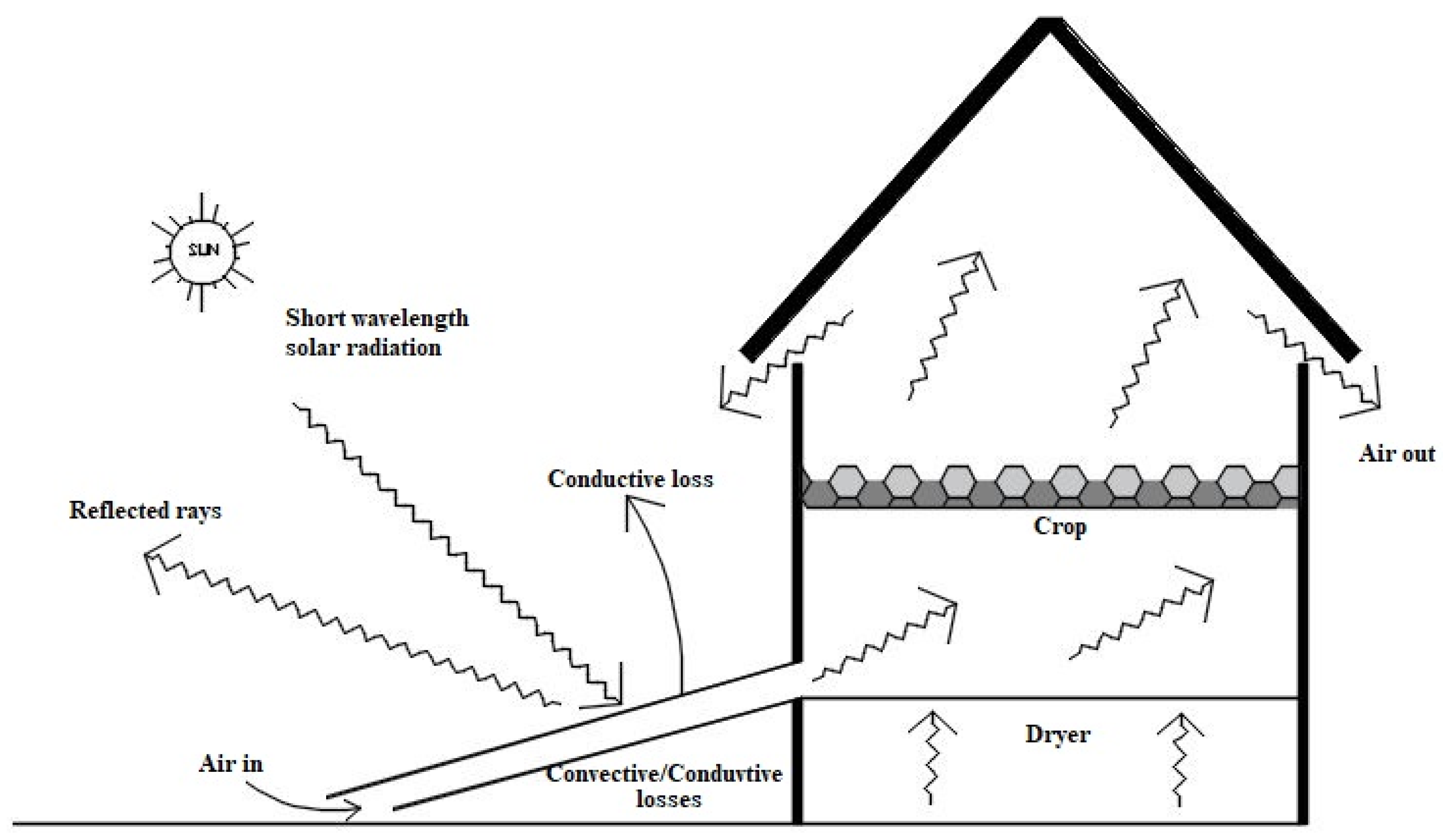

The indirect solar drying process occurs when the crops in drying chamber are not exposing to solar radiation. In the indirect solar dryer, a solar heater is used to dry the air, which is then passed through the drying chamber, either via natural or forced convection. The black painted absorption surface of the simple solar air heater absorbs the solar radiation and transmits it in the form of thermal energy (heat) to a working fluid [13]. Figure 3 represents an indirect solar drying system. The dryer’s chamber is connected to an absorber panel. The temperature of the air that is present inside the drying chamber is increased due to the decrease in solar radiation on the flat plate collector; this heated air passes through the drying chamber via natural circulation or forced circulation. The airflow rate can be controlled (increased) by using a drying chamber with a chimney or by providing a wind operated ventilator situated on the upper portion of the chamber. To further regulate the temperature of the unit, a fueled heat source is also installed, along with an indirect solar dryer [14].

Figure 3.

Indirect solar drying [9].

An assessment of the energy required for drying the agricultural products can be conducted using the initial and final moisture content for individual crops.

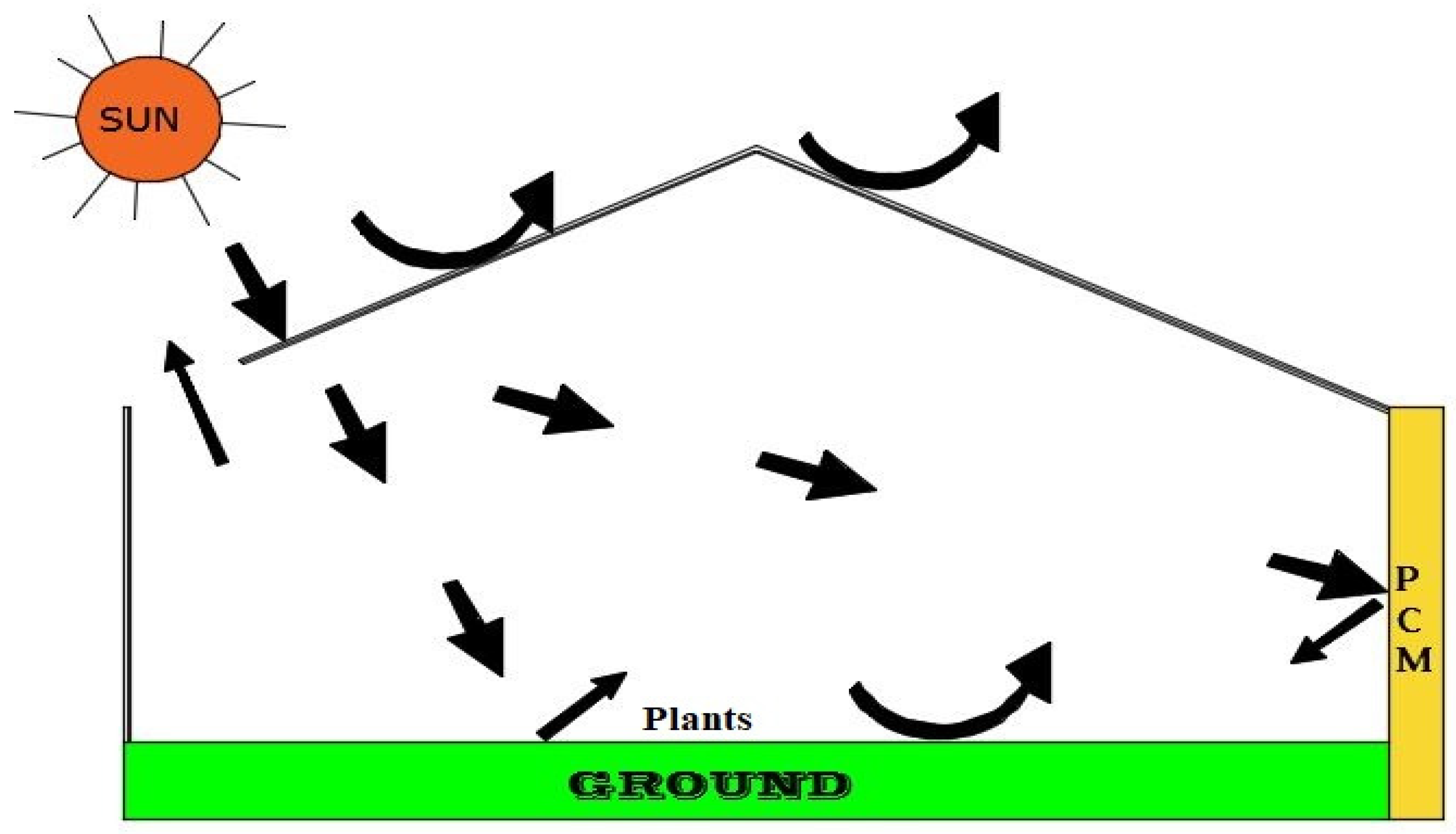

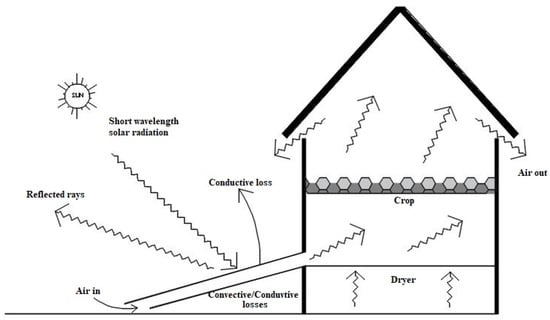

2. Greenhouse Dryer for Different Products

Using a greenhouse dryer is one way in which to conduct direct solar drying. The greenhouse effect is the underlying principle upon which the greenhouse drying system is based [15]. With regard to the greenhouse effect, the solar radiation received by the earth is trapped, thus increasing the overall temperature within the atmosphere. The atmosphere consists of gaseous matter and suspended particles, and it allows most of the incoming solar radiation to enter. The moment this radiation strikes the earth, part of it is immediately absorbed. Some of the energy is reflected back into the atmosphere, in the form of infrared rays, by the earth’s surface [16]. Carbon dioxide (CO2), water vapor, methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) are the gases present in the atmosphere which absorb these infrared rays. The infrared rays that strike atmospheric particles are partially absorbed and partially redirected toward the earth; these rays are also absorbed. The greenhouse effect is the composite effect resulting from the earth’s atmosphere absorbing infrared rays; this effect causes an increase in atmospheric temperature [17]. This natural phenomenon, where in heat is trapped by the earth’s atmosphere, maintains a certain temperature range on earth in order to support life [18]. Figure 4 represents a greenhouse drying system.

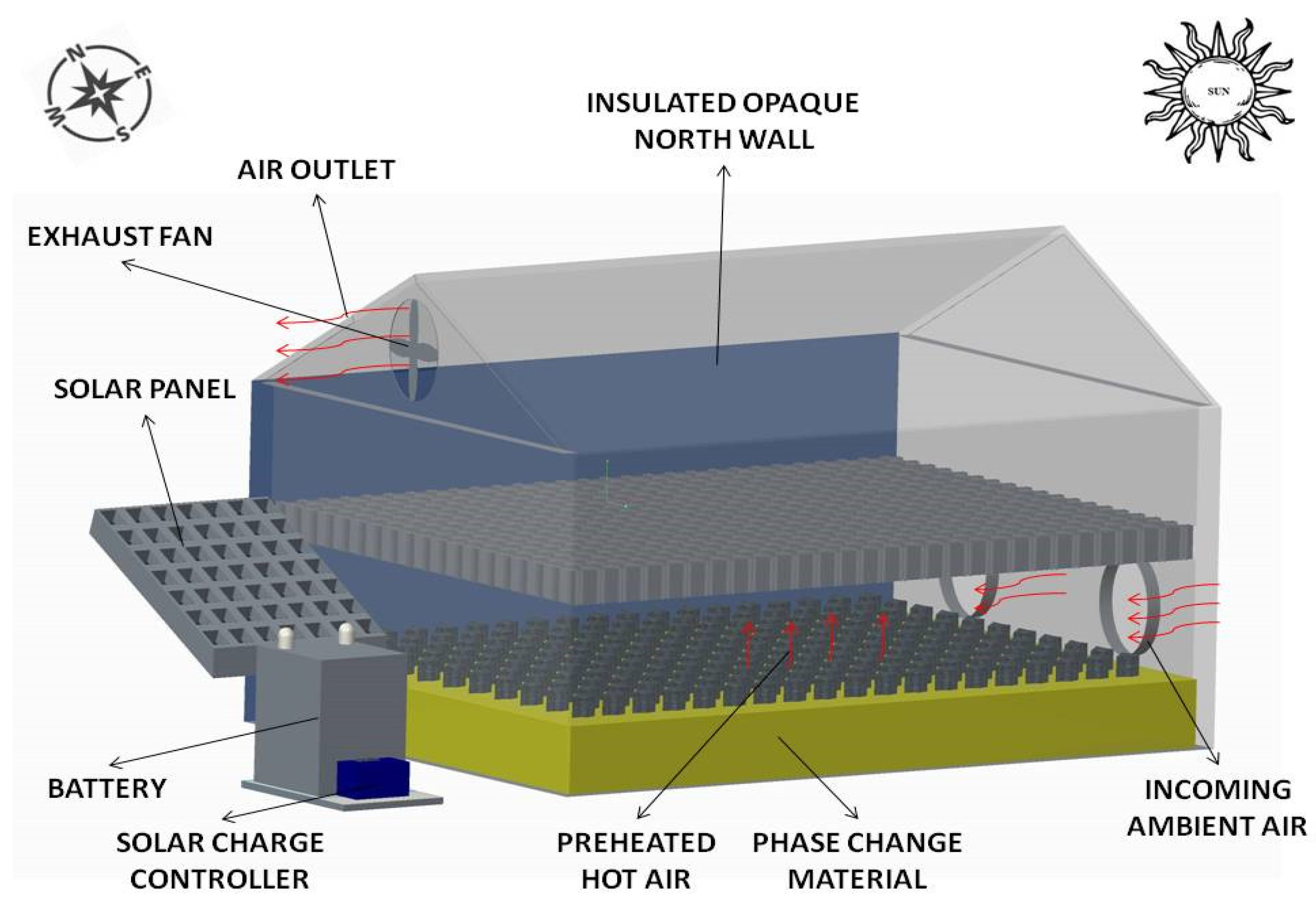

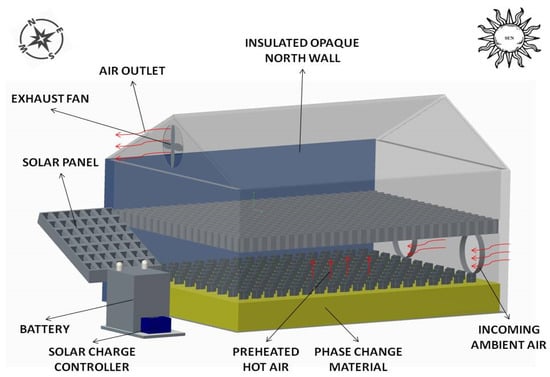

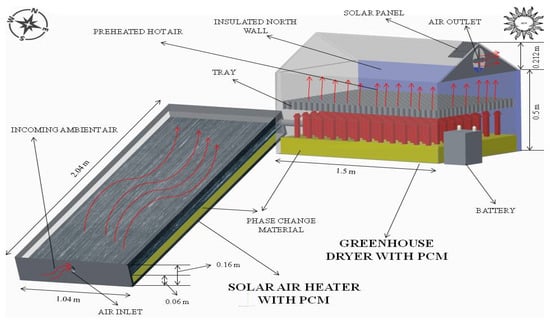

Figure 4.

Greenhouse dryer with a PCM on the north wall [19].

The solar radiation consisting of short infrared wavelengths easily enters the transparent roof and walls of the dryer. It is partially absorbed by the object inside the dryer, which increases the temperature of the product. The heated object emits longer wavelengths, which is relative to its feeble intensity, and it is incapable of penetrating the transparent glass walls and rooves of the greenhouse [20]. The heat energy remains entrapped within the enclosure of the transparent glasshouse. This phenomenon, where in the temperature increases, is known as the greenhouse drying system, which is utilized for drying applications. It regulates the controlled environment; hence, it is also known as a controlled environment greenhouse [21].

2.1. Importance of Greenhouse Drying

The open sun drying technique is the most widely practiced method for the preservation of agricultural products in developing countries. This method does not provide satisfactory results under unfavorable weather conditions, and it can lead to the degradation of the quality and reliability of the product [22]. These losses mainly occur due to the dust and dirt, as well as bacteria and insects. Alternative methods can avoid these losses by drying the agricultural products in a cheaper and more economical way. Using the greenhouse dryer could be the best alternative method to avoid the disadvantages of open sun drying [23].

In the GHD, crops are kept inside the trays in the enclosed structure, and the moisture removal process takes place either via a natural or forced convection mode. The mode of heat transfer depends on the removal of exhaust air from the dryer. The main advantages of using a GHD are:

- (i)

- The fabrication cost is low.

- (ii)

- The structure of a GHD can be used throughout the year, which helps to increase the production of a dried crop.

- (iii)

- Using a GHD improves the use of solar energy in terms of efficiency.

2.2. Greenhouse Dryersfor Different Products

2.2.1. Red Chili

Khawale and Khawale (2016) conducted an experiment by using a solar dryer (double pass) when drying red chili. The results show that the average value of solar radiation is 566 W/m2 and the air flow rate is 0.071 kg/s. The product moisture content was reduced from 80% to 9.1% by using a double pass indirect dryer. This process took 24 h, not including the evening hours. When the red chili was dried in the open sun, the process took 58 h. In this work, the collector efficiency and system drying efficiency were found to be 38% and 59.6%, respectively. The evaporative capacity of the system was observed to be in the range of 0.14–23 kg/h [24].

Dhanore et al. (2014) evaluated the solar tunnel dryer’s performance. This process was used for drying a sample of 5 kg of red chili. The moisture content was reduced to 5% from 75% during this process. The chamber and the ambient temperature were 51.68 °C and 39.1 °C, respectively. The solar radiation ranged between 250 W/m2 and 850 W/m2, and the air velocity was maintained at 0.5 m/s [25].

Fudholi et al. (2013) evaluated a red chili product being dried in both open sun and solar drying conditions. The drying performance of the product was observed during this process. The experimental results showed that the product dried in 30 h and the moisture content reduced from 80% to 10%. In open drying conditions, the product took 65 h to dry. In solar drying conditions, the time taken for the product to dry reduced by 49%. The average evaporation capacity and the average solar intensity were maintained at 0.97 kg/h and 420 W/m2, respectively. The Specific Moisture Extraction Rate (SMER) was observed to be 0.19 kg/kWh [26].

In Thailand, Kaewkiew et al. (2012) evaluated the drying of red chilis in a large-scale greenhouse solar dryer. The sheets in the dryer were made of polycarbonate and they were parabolically shaped. The concrete floor area was 8 m × 20 m, and nine D.C fans were installed for ventilation purposes. The moisture content of the red chilis was 74%, and they were dried in open dryer for three days. The solar radiation intensity during the drying process was observed as ranging between 390 W/m2 and 820 W/m2. The color of the red chili was better maintained in the greenhouse dryer compared with the open sun dryer. The payback period of the large greenhouse dryer was found to be two years; this period must contend with numerous technical and economical parameters [27].

Banout et al. (2011) investigated the open, cabinet, and solar dryers (double pass) in terms of their performance when drying red chili. Regarding open sun drying, the process took 93 h; the process took 73 h in the cabinet dryer; and the process took 32 h in the double pass solar dryer. The chilis used had 10% moisture content. When compared with open sun and cabinet solar dryers, the solar dryer (double pass) has a higher ASTA (American Spice Trade Association) color value and low Vitamin C deterioration was observed. The construction cost of this dryer was greater compared with the cabinet dryer, but the drying rate per kg was less [28].

Mohanraj et al. (2009) evaluated the forced solar dryer design. The capacity of the dryer was 50 Kg, and it had graves for the heat storage of red chili. For 24 h, the red chili was dried, and the moisture content was reduced from 72.8 to 9.1%. The maximum solar intensity was observed to be 950 W/m2, and the average temperature in the dryer was 50.4 °C. The efficiency of the dryer was found to be 21%. The specific moisture extraction rate was recorded at 0.87 Kg/kWh. The humidity was higher at the exit of the dryer, and it gradually decreased as the drying time increased, and at the final stage of the process, it became constant [29].

Hossain et al. (2013) examined are designed solar tunnel dryer, with a capacity of 80 kg, in order to dry fresh red chili. The drying time for the improved solar dryer was 20 h. It reduced the moisture content of the chili from 2.84 kg/kg to 0.04 kg/kg. Compared with the unimproved dryer, it took 32 h to reduce the moisture content from 0.41 kg/kg to 0.08 kg/kg. Green chili took 35 h to reduce the moisture content from 0.70 to 0.1 kg/kg using the traditional drying method; however, it took 22 h to reduce the moisture content from 7.5 kg/kg to 0.05 kg/kg using the improved dryer. Moreover, the quantity and pungency of the product can be improved, and the drying time can be reduced with blanching. The solar dryer’s temperature was constant, and it recorded more than just the atmospheric temperature, which was 21.63 °C. Blanching the red chili improved the color value [30].

2.2.2. Turmeric

Karthikeyan and Murugavelh (2018) worked on a mixed mode solar tunnel (forced convection). In order to harness the solar intensity effectively, inclination is the key factor. The moisture content was reduced from 0.779 kg/kg to 0.07 kg/kg of water/dry matter. The process of drying the product took 12 h compared with open sun drying, which took 43 h. The dryer’s exegetic efficiency was found to be 48.11%, and energy utilization varies between 9.94% and 32.97%. Mathematical models were used in this experiment to observe the behavior of the turmeric [31].

Borah et al. (2015) designed and studied the performance of solar turmeric dryer. Inside the dryer, the temperature was found to be between 38 and 50 °C, and the ambient temperature was recorded and found to be between 24 and 27 °C. Both solid and sliced turmeric was used for the experiment, and the final moisture content was found to be between 6.37% and 15.49% for the solid turmeric, and 78.65% for the sliced turmeric after 12 h. The average effective moisture diffusivity was recorded to be 1.455 × 10−10 m2/s for the solid turmeric and 1.852 × 10−10 m−2/s for the sliced turmeric. In each batch of turmeric powder, the curcumin content varied. During the heat processing of the turmeric, the curcumin content was found to be between 27 and 53%, and there was a maximum loss in pressure cooking for 10 min. The sliced turmeric drying rate was faster than the drying rate for the whole turmeric. For both the sliced turmeric and whole turmeric, the rates of drying were found to be similar, at 62%. Sliced turmeric requires a 25.5 h drying process. During the open sun drying process, the sliced turmeric is affected by white patches of fungal growth. When using a solar collective dryer, no fungal growth was observed, and a Page model was found to be effective for the analysis [32].

Gunasekar et al. (2020) investigated the performance of solar drying for drying turmeric. Biochemical constituents in turmeric, such as oleoresin, the total protein content of boiled turmeric, volatile oil, and curcuma, may vary. The quality of the turmeric may result in varying levels of moisture due to these biochemical constituents. Due to the boiling and drying processes of turmeric, the curcumin content was found to be intensified. During the open sun drying process, the drying time was 96 h, and it was 63 h during the solar drying process. The solar dryer temperature ranged between 28 and 88 °C. The moisture content of turmeric was reduced from 79.04 to 7.14% over 12 days during the open sun drying process. The curcuma content varies non-linearly with respect to moisture content. Initially the moisture content in turmeric was found to be 2.89 g per 100 g at 78.04%, and it varied between 2.88 g and 4.55 g per 100 g sample during the open sun drying process. A small variation in volatile oil content was shown during the open sun drying process. The volatile oil content before the drying process was found to be 5.9 mL/100 g of sample, after the drying process it was found to be 5.26 mL/100 g for the sun-dried sample, and it was 5.21 mL/100 g for the solar dried sample. The oleoresin content after the drying process was found to be 8.97 g/100 g of sample for the open sun drying process and it was 9.21 g/100 g of sample for the solar drying process. The boiled turmeric initially had aoleores in content of 1.24 g/100 g of sample, and it also decreased linearly by 1.15 g/100 g of sample during the solar drying process, and by 1.77 g/100 g of sample during the sun drying process. By drying the product in a solar dryer, more proteins were obtained from the sun, and this is beneficial both biologically and theoretically [33].

Lakshmi et al. (2018) investigated the mixed mode solar dryer’s (forced convective type) performance. This process is used for sliced turmeric samples that are integrated with the heat storage. In this process, 35 kg paraffin wax was used as the thermal storage during the liquid stage. The moisture level was reduced from 73.4 to 8.5% over 18.5 h in a mixed forced solar dryer, and in open sun drying conditions, it took 46.4 h. A moisture level of 12% was found after using the solar dryer, and when it was equipped with a solar air heater, the efficiency was calculated to be 25.6%. The mixed mode solar dryer saved time by 60%. The total flavonoids content for the solar dryer operating in a mixed mode was found to be 7.58 mg/g of sample, and it was found to be 1098 g and 8.08 g for fresh turmeric and solar dried turmeric, respectively. A high medical agriculture value was found after using the mixed mode solar dryer [34].

2.2.3. Copra

Yahya et. al., (2018) evaluated the solar air dryer’s (double pass) performance using a finned absorber for drying copra. During this drying process, the moisture level was reduced from 52.68 to 10.73% over 23 h, and in open sun drying conditions, it took 67 h. The air flow rate and the average rate of drying was maintained at 0.084 kg/s and 0.054 kg/h, respectively. For open drying and solar air drying, the average rate of drying was 0.191 kg/h. The efficiency of the system was found to be 39.47%, and the improved potential rate was 87.98 J. In Indonesia, open sun drying and smoke-drying processes are used for drying coconut; this has disadvantages such as debris, rain, and insect infestation [35].

Ayyappan et al. (2010) studied the copra drying process in a solar tunnel dryer. Under full load conditions, the natural conventional solar dryer took 57 h for the moisture content to reduce from 52.8 to 8%, and under half load conditions, it took 52 h. Compared with the open sun drying process (53%), good quality copra was obtained in the solar tunnel dryer (54.66%). The average efficiency was found to be 21%, and the solar intensity was found to be 860 W/m2 [36].

Mohanraj et al. (2008) worked on a forced convective solar dryer, which involved designing, manufacturing, and testing it. Regarding its different levels, the moisture level was reduced from 51.8 to 7.8% on the bottom level, and it was reduced to 9.7% on the top level. The thermal efficiency of this system was found to be 24%. The kiln drying process was the alternative method to the open sun drying method for drying copra. In India, via direct contact with smoke, copra is dried, and the possibility for smoke deposition emerges. Copra with a high quality of 78% was achieved by using this dryer, and a thermal efficiency of 25% was achieved; the copra was left undamaged [37].

2.2.4. Grapes

The numerical model for the greenhouse solar drying of grapes was studied by Hamdi et al. (2018). The moisture level was reduced from 5.4 to 0.23 (g water/g dry matter) within 128 h. The temperature in the solar dryer was 55.98 °C compared with the ambient temperature that was found to be between 24.55 °C and 35.72 °C. The simulation of the mathematical model was conducted using TRNSYS software [38].

Ramos et al. (2015) developed a mathematical model based on the explicit finite difference. It was integrated with the heat and mass transfer model. The model incorporated the effective moisture diffusivity parameter, which caused changes in terms of shrinkage and the reliance on thermal properties in water [39]. The simulation model predicted accurate times. The hemi cylindrical solar dryer’s temperature was maintained between 55 and 80 °C. On the first day, the moisture content was reduced from 84% to 69%, and on the seventh day, it was further reduced to 16.5%. The pre-treatment process reduced the moisture content in less time [40].

Fadhel et al. (2005) revealed that greenhouse drying has zero running costs. The time taken to dry grapes in a solar greenhouse dryer, and via open sun drying, took 78, 120, and 205 h, respectively [41].

Yladiz et al. (2001) studied the regression model and estimated the coefficient and effect of an electric fan on air temperature. The moisture content in grapes was reduced to 0.15 kg water/kg of dry matter from 2.5–3.2 kg water/kg of dry matter. During the first 34 h of drying time, an air velocity of 1.0 m/s was recorded, and after 35 h, the air velocity was 1.5 m/s. The coefficient of regression and the R2 was 0.98 and 4.10 × 10−3, respectively [42].

2.2.5. Peanuts

Ester Y. Akoto et al. (2017) developed a solar dryer in order to improve peanut quality. The reduction in moisture content was 5.42% and 31.8% from 25.84% after single layer drying, and it was reduced to 4.24% after four layers drying, respectively [43].

The development of the dryer not only accelerated the drying of peanuts, thus enabling an evaluation of the quality of peanuts. Noomhorn et al. (1994) discovered that at 10 rpm, at a 75 °C temperature, and at a feed rate of 9 kg/min, the optimal quality was obtained. At higher temperatures, peanuts have poor quality index uniformity and a greater drying time because of the pressure of the sand. The drying time was reduced by reducing the feed rate and changing the rpm of the drum [44].

Bunn et al. (1972) studied an empirical equation related to high moisture content. It was tested in a drying environment, and it was also compared with frequently used drying methods [45].

2.2.6. Fish

Abdul Majid et al. (2015) experimented on 10 kg batch size solar dryer, studying silver cyprinid fish over 12 h. The moisture content was reduced to 18% from 72%, whereas in the open sun it took 20 h. The efficiency of the system and the collections were 12% and 9.4%, respectively. The bottom, middle, and top tray of the dryer maintained constant rate i.e., 0.145, 0.145, and 0.147 respectively [46].

Bassanio et al. (2011) designed the solar tunnel dryer to accommodate 50–110 kg. Half of the tunnel’s base was used for drying and air heating for 30 h; the moisture content was reduced to 15.6% from 66.6%, and the efficiency of the dryer was 29.8%. The fish quality was enhanced in terms of flavor, food value, brightness, color, and taste [47].

Bhor et al. (2010) evaluated the solar tunnel dryer and found that the drying rate was higher compared with open sun drying. The temperature was maintained at 53.8 °C and the moisture content of the fish without salt was reduced to 19.04% over 33 h and 20% over 36 h for the upper and lower trays, respectively. In the case of sun drying, the moisture content reduced to 19.68% over 40 h. The salted fish’s moisture content was reduced to 19.5% over 36 h and 19.6% over 38 h for the upper and lower trays, respectively [48].

3. Classification of the Greenhouse Drying System

There are three types of greenhouse dryers which are classified on the basis of air circulating within the drying chamber [49]:

3.1 Natural convection solar greenhouse dryer;

3.2 Forced convection solar greenhouse dryer;

3.3 Hybrid solar greenhouse dryer.

3.1. Natural Convection Solar Greenhouse Dryer

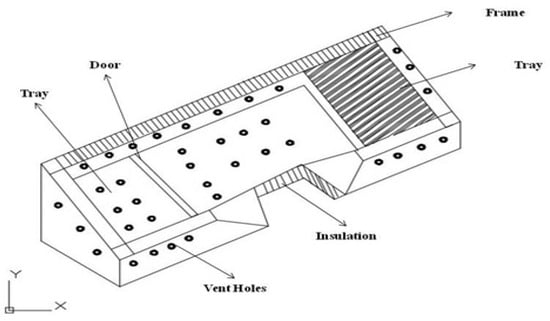

With this type of dryer, the incidental radiation is transmitted through the canopy of the system, which results in the heating of the crops. The temperature of the crop increases because solar radiation is absorbed. The principle of the thermosiphon effect works in the natural convection solar greenhouse dryer [50]. Ventilation is provided at the top of the dryer which enables humid air to be released from the dryer. The buoyant forces are responsible for the circulation of heated air through the crop when using this type of system. The movement of air within the drying chamber is called the passive mode and a dryer operating under such a convection mode of operation is termed as a natural convection solar greenhouse dryer [51]. Figure 5 shows the pictorial view of a natural convection solar greenhouse dryer.

Figure 5.

Pictorial view of a natural convection solar greenhouse dryer [52].

Natural circulation greenhouse dryers are used for drying agricultural products at the farm level because of the non-availability and erratic power supply in remote rural areas. It consists of an inclined collector coupled with a drying chamber, which contains trays to hold the agricultural products. The air circulation within the drying chamber takes place due to the differences in density; this occurs as a result of the buoyant forces [15].

However, due to high air resistance, airflow is not possible through the thin layer using natural convection; therefore, to increase the airflow, ventilators or chimneys are installed. Rodents and rain do not damage the dried products in the natural convection solar dryers during the drying process. Moreover, the drying time is minimized when compared with the open sun-drying process.

Natural circulation greenhouse dryers are modified forms of regular greenhouses. For a controlled airflow, vents of appropriate sizes and positions are incorporated into the dryer. The earliest types of passive solar greenhouse dryers are characterized by a large transparent cover of polyethene with an inclined glass roof to help allow direct solar radiation to cover the product [53]. The problems that arise from using natural convection greenhouse dryer include the holding capacity of the dryer, which results in low productivity; there is a risk of the air circulation failing, thus causing the drying products to spoil; and the exposure to solar radiation may result in vitamin loss and decolorization. Ahmad and Prakash (2019) designed and built a greenhouse dryer that uses natural convection. The bed of the drying chamber was covered with sensible heat storage materials. Four distinct types of bed were chosen for the comparative heat transfer assessments of the proposed setup: a gravel bed, ground bed, concrete bed, and a black painted gravel bed. The black painted gravel bed provided conditions that produced the highest heat gain, which was 53%, whereas the corresponding values for the concrete bed, gravel bed, and ground bed were 33%, 49%, and 29%, respectively. As a result, a black-painted gravel bed is strongly advised for optimal heat storage [54]. From studying the literature, we may conclude that only forced ventilation systems containing a blower or a fan helps in the proper removal of moist air.

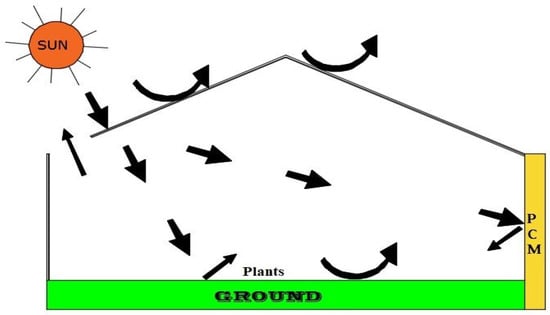

3.2. Forced Convection Greenhouse Dryer

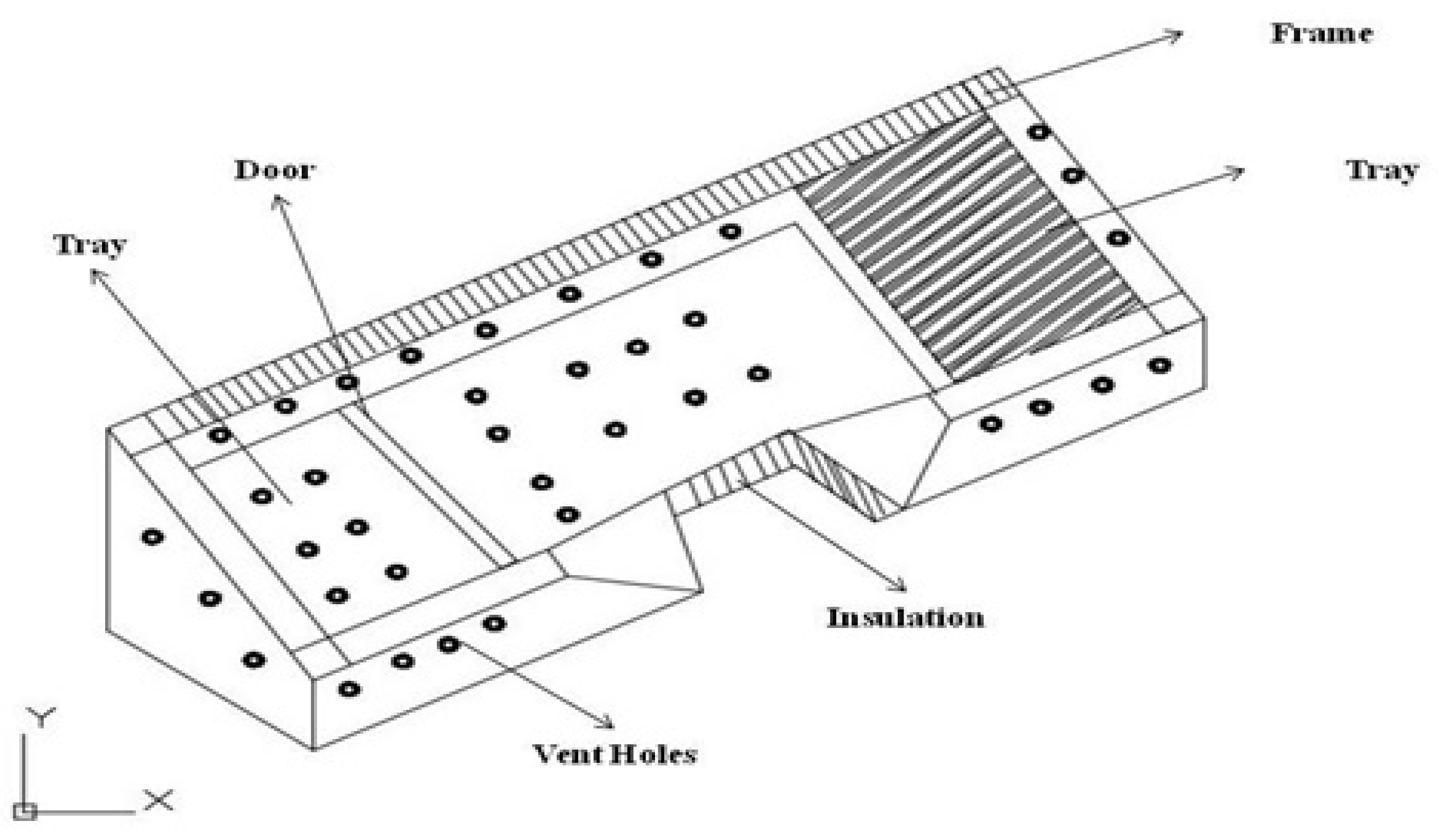

In order to regulate the temperature and moisture evaporation, an optimum airflow is required for the greenhouse dryer throughout the drying process; this is achieved by observing the changes in the weather conditions [55]. An exhaust fan is installed on the west wall to eliminate the humid air [56]. The GHD airflow is regulated by the use of a blower or fan; this is called a forced convection solar greenhouse dryer [51]. Figure 6 shows the pictorial view of a forced convection solar greenhouse dryer.

Figure 6.

Forced convection solar greenhouse dryer.

Movement of the hot air from the drying chamber occurs as a result of the fans in the forced convection greenhouse dryers. For high moisture content products, such as tomatoes, papaya, grapes, chilis, kiwis, bitter-gourds, cabbages, brinjal, and cauliflower, forced convection greenhouse dryers are the most suitable [51].

The five basic components of a forced convection greenhouse drying system are: a drying chamber; a tray to contain the product that needs drying; an inlet hole; an outlet hole adjusted with a fan or blower for air circulation; and for a continuous steady power supply, a battery charging system is required. The heated air passing over the wet product facilitates moisture evaporation due to the convective heat transfer mode [57]. The difference in moisture concentration between the crop surface and dry air causes drying [58].

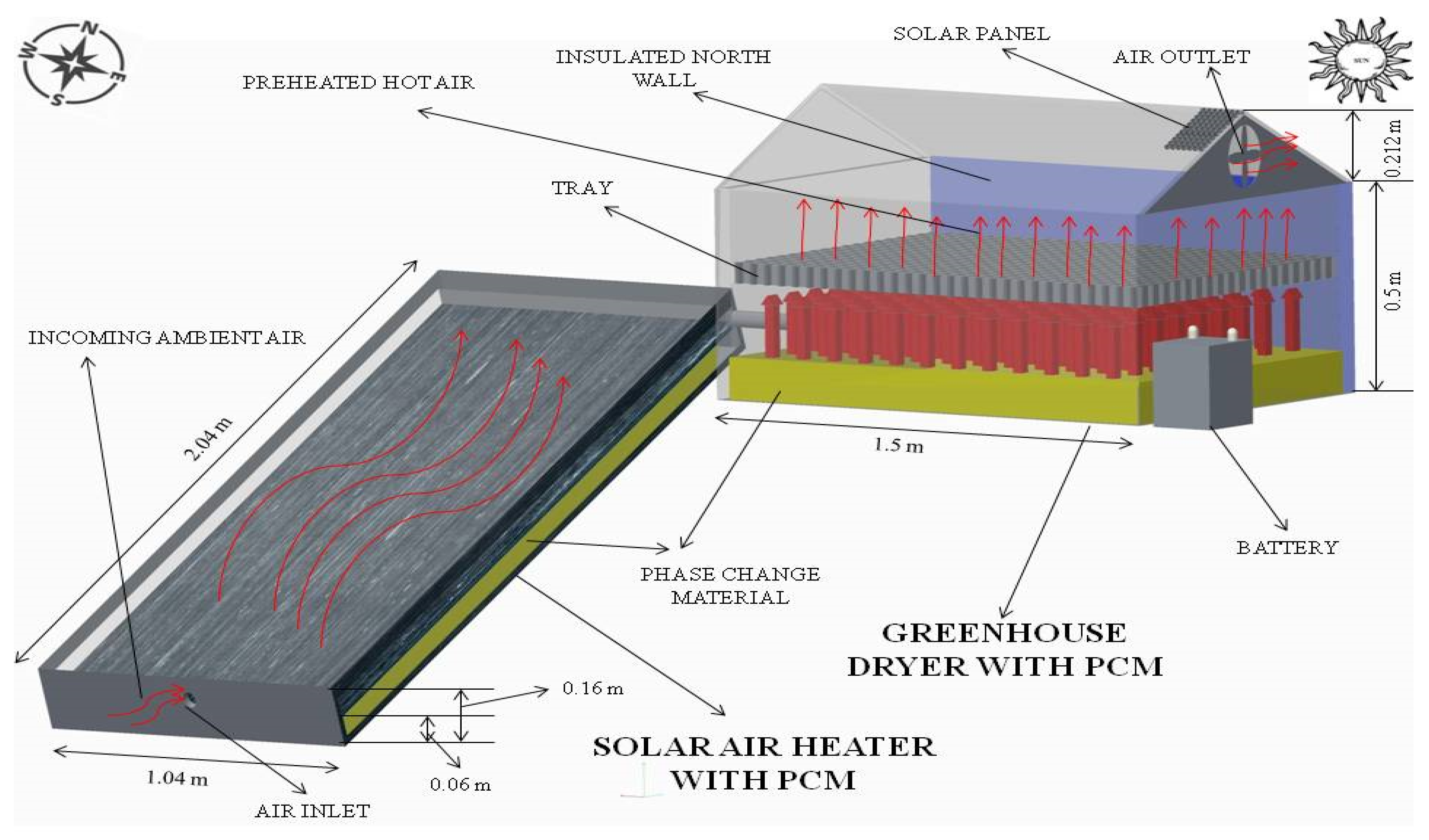

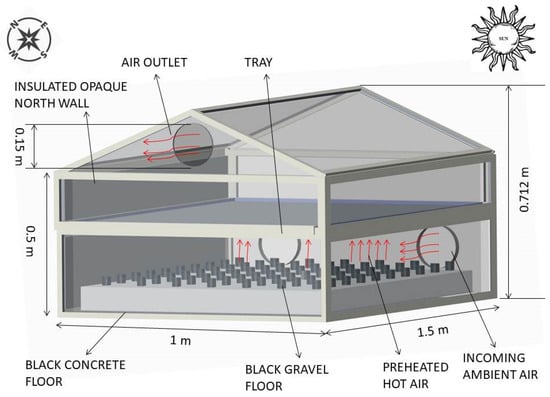

3.3. Solar Hybrid Greenhouse Dryer

The solar drying system is mainly divided into three modes of operation; direct mode, indirect mode, and hybrid mode. Regarding the hybrid solar dryer, the combination of two sources of energy is supplied for drying purposes. The combination of two sources can be wholly renewable or non-renewable [59]. The types of hybrid solar dryers are: (i) hybrid solar dryer assisted by geothermal energy; (ii) hybrid solar dryer assisted by biomass energy; (iii) hybrid solar dryer assisted by ocean/wind energy; (iv) hybrid solar dryer assisted by renewable energy; and (v) hybrid solar dryer assisted by solar air heater. In a hybrid greenhouse dryer, the dryer is assisted by other energy supplies [60]. Moreover, the hybrid dryer should have the ability to work in both an active and passive mode depending on what is required. Figure 7 represents the hybrid greenhouse dryer.

Figure 7.

Hybrid greenhouse dryer.

4. Performance of Greenhouse Dryer in No Load Condition

The thermal performance indicator has been estimated for the heat storage-based greenhouse dryer operating in the passive, active, and hybrid modes.

4.1. Overall Heat Transfer Coefficient

The overall heat transfer coefficient (OHTC) measures the one dimensional steady-state heat transfer rate of the system [61]. It can be calculated using Equation (1):

Here, is the heat transfer coefficient, is thickness, is thermal conductivity, is the heat transfer coefficient for the canopy, and represents the overall heat transfer coefficient. The relationship with was also developed by Connellan, as per Equation (2):

It has been further calculated as follows:

The quantitative characteristic of a convective heat transfer between the surface (wall) and a fluid (air) is termed as the heat transfer coefficient. It can be calculated as shown in Equation (3):

where is the ground to room heat transfer coefficient and is the heat transfer coefficient at room temperature.

The available moisture content in the crop is determined by the evaporative loss. It can be evaluated as shown in Equation (4):

where is neglected in accordance with the no-load condition [50].

The ground to room air heat transfer coefficient is evaluated as shown in Equation (5):

The greenhouse room air heat transfer coefficient is calculated as per Equation (6):

where, is the ground temperature, is the room temperature, is the Stefan Boltzman Constant, is emissivity, is relative humidity, and is vapor pressure.

The thermal conductivity equation is shown in Equation (7):

The canopy heat transfer coefficient is evaluated as shown in Equation (8):

Vapor pressure at temperature T is evaluated as shown in Equation (9):

The mean temperature can be calculated as shown in Equation (10):

4.2. Dimensionless Number of the Experiments

To study heat transfer, dimensionless numbers are important tools. These tools are also used in the analysis of the convective heat transfer coefficient [49].

The grashof a number (Gr) is the ratio between the buoyancy force and viscous forces. The Gr number explains the effect of the hydrostatic lift force and the viscous force of air in the setup that is operating under passive mode conditions. It can be evaluated as per Equation (11).

where is the characteristic dimension parameter, is acceleration due to gravity, is the coefficient of thermal expansion, ΔT is the difference between the surface and the fluid temperature, and is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid.

The Raleigh number (Ra) is the product of the Grasoff number and the Prandtl number. It can be evaluated as per Equation (12).

where is the specific heat, is the density of the fluid, is thermal diffusivity, and is the dynamic viscosity of fluid. The Nusselt number (Nu) is defined as the progress of the heat transfer at the canopy of the proposed experimental setup to the air boundary. Moreover, it is the ratio between convective heat transfer and heat transfer through conduction in a fluid. It can be evaluated as per Equation (13).

where is the heat transfer coefficient and is thermal conductivity.

The ratio between the momentum diffusivity and the thermal diffusivity characterizes the relationship between heat transfer and the air motion; this is called the Prandtl number (Pr).

It can be evaluated as per Equation (14).

where can be evaluated as per Equation (15).

When using the active mode or forced convection mode, the dimensionless parameter (i.e., the Reynold number) is calculated, whereas the Nusselt number and Prandtl number can also be calculated in the same manner as the passive mode [49]. The Reynold number can be analyzed as per Equation (16).

where is the flow speed.

4.3. Coefficient of Diffusivity

The instantaneous thermal loss factor () provides the drying time and it enhances the rate of moisture removal [34].

Indirect loss and direct loss are the types of losses that are accounted for with the instantaneous thermal loss factor. Equation (17) describes indirect loss, and Equation (17) describes direct loss [62].

The coefficient of diffusion is calculated using Equation (20):

where can be calculated by adapting Equation (21):

where is the area of the tray, is the solar intensity, is the greenhouse room temperature, is the density of room, is the partial pressure difference, is the area of the vent, is a component found in no-load conditions, is the coefficient of diffusivity, is the instantaneous thermal loss at the vent, and is the instantaneous thermal loss that occurs at the canopy.

4.4. Heat Loss Factor

Due to the low density, the excess amount of air in the greenhouse dryer moves in the direction of the ventilator; this is called the heat loss factor [63]. This is evaluated in accordance with Equation (22):

The heat loss due to the exhaust fan in the forced convection mode of the heat storage-based greenhouse dryer can be calculated as per Equation (23)

where is the number of air exchanges per hour and is the volume inside of the greenhouse dryer.

4.5. Heat Utilization Factor

The heat utilization factor is the ratio between the difference between the ground temperature and the room temperature, and the difference between the ground temperature and the ambient temperature, during the drying process [64]. This parameter is calculated in accordance with Equation (24):

4.6. Air Exchange per Hour

Numerous air exchanges/h (N) happen by the exhaust fan in the proposed greenhouse dryer. These exchanges predominantly rely on the limitations of the exhaust fan, particularly its rpm and the number of fans utilized in the ventilator. It tends to be determined in accordance with Equation (25) [64].

4.7. Electrical Efficiency and Solar Photovoltaic System (SPV) Efficiency

The PV module efficiency is determined as per Equation (26)

The solar photovoltaic system comprises a sunlight-based module, a battery, a sun-powered charge regulator, and a DC exhaust fan. The solar photovoltaic system’s (SPV) effectiveness can be determined as per Equation (27).

where is the voltage of the open circuit, is the cross-section area of the ventilator, is the volume inside of the greenhouse dryer, is the short current, is the global solar radiation, is the area of the solar cell, is the load voltage, and is the load current.

5. Performance of the Greenhouse Dryer under Load Conditions

The thermal performance indicator has been estimated for the heat storage-based greenhouse dryer operating in active, passive, and hybrid modes.

5.1. Ratio of Moisture ()

The moisture content (Mini) for crops and the basis for wetness (w.b.) were calculated as per Equation (28):

where is the initial weight of the crops, whereas is the weight of the crops on an hourly basis. The computation of the final and initial moisture contents help calculate the total removal of water content () from the crops [5]. It can be evaluated as per Equation (29):

where is the initial moisture content with regard to the basis of wetness, and is the final moisture content with regard to the basis of wetness.

The instantaneous moisture content with regard to the basis of dryness can be calculated at a specific time (), as per Equation (30) [65]:

The moisture ratio () can be calculated as per Equation (31) [66]:

where is the equilibrium moisture content and is very high compared with ; thus, the abovementioned equation can be expressed in accordance with Equation (32):

The drying rate of the crop can be determined as per Equation (33):

where is the level of moisture evaporated per kg, is the amount of dried mass per kg, and is the time required for drying.

5.2. Drying System Efficiency ()

Drying system efficiency was achieved with the help of an equation based on exhaust fan energy consumption. This is shown in Equation (34) [5]:

6. Thermal Modelling of Greenhouse Dryers

6.1. Necessity of Thermal Models

This experiment is costly and time-consuming; thus, thermal modelling is the best option for enhancing the dryer’s operational parameters. Software helps to make the analysis more exact, quicker, and simpler.

Thermal modelling is an economic model and it can be used for designing greenhouse dryers. It can also be used to achieve the maximum efficiency. During the design stage, thermal model simulation results are useful for investigating certain parameters. The greenhouse dryer performance depends upon the assessment of the heat transfer coefficients. The moisture content of agricultural produce is significant for the computation of the dryer’s performance and the drying rate. The moisture content ratio is shown as a function of time from the experimental data, and the data is fitted with theoretical models that are available in the literature using statistical parameters. The constants and correlation coefficients in the empirical models have no physical significance. The moisture content plot determines data fitting and constant estimation. Additionally, the mean absolute error, the root mean square error, and the reduced chi-square are computed in order to identify the best-suited model. The thin layer drying models are developed from Newton’s rule of cooling (Newton, Page, and Modified Page model), Fick’s second law of diffusion (Henderson and Pabis model), and the others are empirical models (Thompson and Wang model; Singh model). Table 1 lists the equations for several frequently used thin-layer drying models.

Table 1.

Thermal Models [67].

6.2. Thermal Modelling of Solar Greenhouse Drying Systems

Thermal modelling solar greenhouse drying systems is necessary to optimize the various heating designs and operation parameters. The fan system, earth–air heat exchanger, greenhouse room air temperature, ground air collector, greenhouse floor, canopy cover, insulation on north wall, the storage capacity inside the greenhouse dryer are the components of a greenhouse dryer [2,66].

6.2.1. Thermal Modelling of Natural Convection Solar Greenhouse Dryer

Tiwari et al. (2004) worked on the drying process of jaggery, and they evaluated the mathematical modelling used for calculating the convective mass transfer coefficient when roof-type natural convection solar greenhouse dryers are used. Jaggery temperatures, the mass evaporated, the relative humidity, and the greenhouse room air temperature was measured in order to calculate the mass transfer coefficient for convection. The convective mass transfer coefficient was largest first, and it gradually decreased as drying continued. In this experiment, the convective mass transfer coefficient ranged between 1.28 W/m2 K and 1.41 W/m2 K [68].

Kumar and Tiwari (2006) created a thermal model for calculating the hourly estimates of the jaggery temperature, the greenhouse air temperature, and moisture evaporation in a span roof-type greenhouse drying system for drying jaggery under natural convection conditions. The experimental and anticipated values were determined to be effective. For greenhouse air and jaggery temperatures, the coefficient of correlation was 0.9–0.99, and the mass was 0.96–1. The mass of the jaggery and the thin layer that helped to establish the thermal model was suggested to construct the greenhouse dryer [69].

Jain and Tiwari (2004) developed a mathematical model to investigate the thermal behavior of peas and cabbage during the drying process, as well as to forecast the room temperature, moisture evaporation, and crop temperature. The greenhouse and ambient characteristics were calculated using MATLAB software and they were experimentally tested. Using experimental measurements, the anticipated values were found to be effective. For the crop and dryer air temperatures, the coefficient of correlation ranged between 0.79 and 0.99. The crop mass when drying had a coefficient of correlation between 0.98 and 0.99 [51].

Sacilik et al. (2006) analyzed mathematical modelling for sun tunnel drying systems for thin layers of tomato (organic). This technology lowered the initial expenditure during thedryer manufacturing while improving the product [70].

Janjai et al. (2011) used thermal models to forecast greenhouse dryer performance for dry chilis, bananas, and coffee. For the purpose of performance evaluation, many characteristics such as relative humidity, air temperature, and moisture content were taken into account. To develop the mathematical models, certain assumptions were made: the air flow in the dryer was unidirectional, there was no stratification, the drying calculation was based on the thin layer drying model, and the specific heat used for the cover, product, and air were all constant. It was discovered that there was a reasonable degree of consistency between the theoretical and experimental moisture contents of coffee, bananas, and chili during the drying process [71].

Turhan (2006) used thermal modelling to assess the heat uptake and thermal efficiency of natural convection greenhouse dryers under both no-load and load conditions. The dryer was also tested without a chimney and with a chimney to see how the chimney affected the air flow. Due to the increased air velocity, the dryer assisted by a chimney provided an enhanced mass flow rate [72].

These dryers were proven to be very useful in wet, high, and relatively humid climates.

6.2.2. Thermal Modeling of a Forced Convection Solar Greenhouse Dryer

Thermal modelling was used by Tiwari et al. (2004) to determine the convective mass transfer coefficient for drying jaggery in a greenhouse dryer under forced convection conditions. The room temperature, jaggery temperature, the mass evaporated, and the relative humidity were used to compute the convective mass transfer coefficient; this varied between 1.5 and 1.7 W/m2 K. This value is greater than the value obtained from the natural convection mode [71].

Kumar and Tiwari (2006) used thermal modelling to optimize the operating parameters of a greenhouse drying system for drying jaggery under forced convection conditions. The coefficient of correlation was found to be between 0.97 and 0.97, and the square root of the percentage variation was found to be between 6.78 and 12.72 percent, thus indicating that the predicted and experimental findings were in accordance with one another. The flow rate of air had a substantial impact on drying jiggery [69].

Condori and Saravia (1998) created a model to better recognize the evaporation rate in single and double chamber forced convection greenhouse drying systems. Regarding the modelling, the drying kinetics of the product, as well as the dryer design characteristics, was considered. The dryer performance curve and the generalized curve were also introduced. The generalized drying curve serves as a reference for operational parameters, time variable factors, and solar energy, whereas the dryer performance curve depicts the production efficiency. Based on the simulation findings, it was determined that only a few system functions can improve the drying potential, in addition to the production rate, which would subsequently increase [58].

To estimate the performance of the tunnel-type greenhouse dyer, Condori and Saravia (2003) created an analytical model. The greenhouse was used as a solar collector in this investigation. The incidental solar radiation and greenhouse outlet temperature were found to have a linear relationship. Using the dryer’s characteristic functions, the dryer’s performance was assessed [73].

Jain (2005) suggested a transient analytical model. The packed bed thermal storage was installed against the dryer’s north wall. The north wall achieved a temperature of 86 °C during peak solar radiation hours. Thermal energy storage has a considerable impact during cloudy hours, and it may be particularly effective in reducing temperature fluctuations during the drying process. The presented model is beneficial for predicting greenhouse dryer performance [74].

Prakash and Kumar (2013) conducted a full thermal analysis of the improved active greenhouse dryer in no-load mode. To prevent direct solar energy loss, a black PVC sheet was laid on the greenhouse floor, and a mirror was installed on the north wall. The dryer was placed on the barren concrete floor on the first day in order to grasp the effectiveness of the system, and it was placed on the black PVC sheet on the second day in order to understand the effectiveness of the system. The goal was to ascertain how successful the modified dryer was with regard to drying crops with a higher moisture content. All of the adjustments were determined to be appropriate for agricultural products with greater moisture contents [50].

Thermodynamic modelling and the experimental validation of a PV-ventilated solar greenhouse dryer for peeled longan, banana, tomatoes, and macadamia nuts, were presented [75]. To explain heat and mass transfer during drying, partial differential equations were created and solved numerically using the finite method. This model provides the best greenhouse dryer design data. To investigate the effectiveness of a battery-operated walk-intype of solar tunnel dryer for drying surgical cotton produced in Udaipur (India), Panwar et al. (2013) used thermal modelling. The dryer had a capacity of 600 kg, and it could reduce the moisture content from 40 to 5% in a single day [76].

Thermal modelling was used by Barnwal and Tiwari (2008) to investigate the convective heat transfer coefficient for drying of grapes in a PV/T hybrid greenhouse dryer [77].

7. Environomical Analyses of Greenhouse Dryer

Due to the rise in fuel costs, the cost of the materials, and the higher energy impact of the energy system, the need for energy analysis becomes very important for any energy system; therefore, for the proposed drying system, it was important to conduct an environomical analysis [78].

7.1. Embodied Energy

Embodied energy is defined as the total energy required for producing any product or service [79].

7.2. Energy Payback Time (EPBT)

The energy payback period is the required time to recover the embodied energy of the product. It is determined in accordance with Equation (35) [80]:

where is embodied energy and is the annual energy output.

Therefore, the energy payback time relies on embodied energy and the annual energy output.

7.3. CO2 Emission

The average CO2 emissions for electricity generated by coal, as suggested by Prakash and Kumar, are approximately equivalent to 0.98 kg of CO2/kWh [81]. The lifetime of the north wall that insulated the greenhouse dryer was found to be 35 years [82]. The CO2 emissions per year can thus be calculated as per Equation (36):

where is the lifetime of the proposed system.

7.4. Cost Analysis

The payback period of the dryer is calculated as:

where Dc is the dryer cost, di is the rate of interest, and f is the rate of inflation.

7.5. Carbon Mitigation and Earned Carbon Credit

To measure climate change potential, measures to mitigate carbon dioxide emissions should be undertaken. This can conveniently be compared with other power production systems because the unit of measurement for the mitigation of net CO2 emissions is per kilowatt hour. Defining carbon credit is a key component of national and international emission trading schemes that have been implemented in order to mitigate global warming. Minimizing the effects of greenhouse emissions on a commercial scale occurs when the total annual emissions are capped; this provides an opportunity to compensate for any shortfall that may occur when the assigned mitigation level is not reached. Given the current prices, the exchange of carbon credit can be bought and sold in international markets or between businesses. Carbon credit may be utilized in financial carbon reduction schemes [83]. The daily thermal output, daily thermal input, and annual thermal output energy can be calculated using Equations (38)–(40):

where is the moisture evaporated, is the latent heat of evaporation, Nd is the total number of sunny days in a year (i.e., 300 days), Ean is the annual thermal output energy, Ac is the area of the solar collector, and Nh is the number of sunny hours per day.

Coal-based power was calculated to be 0.98 kg of CO2/kWh as a result of the mean CO2 equivalent intensity; therefore, the amount of CO2 that is mitigated by the system would be calculated as per Equations (41) and (42).

where Em is embodied energy in kWh and n denotes the lifespan of the dryer, which is 35 years. The earned carbon credit was calculated as per Equation (43)

Here, the cost of carbon credit is denoted by D which varies betweenUSD5–20/ton of CO2 that is mitigated.

8. Analysis on the Recent Trends of Greenhouse Dryers

The proper drying techniques are profitable for reducing the post-harvest losses of agricultural products [84]. The use of solar energy has been used for drying purposes since ancient times. GHD is one of the techniques used for the preservation of agricultural products that will be consumed in the future [85]. Experiments conducted by earlier investigators demonstrate that drying is an energy-intensive operation. The complex processes comprising heat and mass transfer are involved in drying the drying medium and the product [86]. In order to meet the increasing demand for food preservation, research has continuously been conducted on greenhouse drying methods in order to develop cheap, simple, and efficient solar dryers which are independent of seasonal vagaries [87]. Many studies, from all over the world, have consistently focused on drying applications and the design of solar dryers.

The recent developments in greenhouse dryers are predominantly based on reducing the length of the drying period, improving the efficiency of the dryer, and productively utilizing solar energy. There have been many innovative techniques applied to greenhouse dryers, such as the use of Phase Change Materials (PCMs), integration with solar air dryers, closed loop operations (automated), and so on. In this paper, greenhouse dryer development analysis is evaluated based on the dryers’ performances, the impact on the environment, and economic parameters.

The drying rate, specific moisture extraction, thermal and overall efficiency, coefficient of performance (COP), rate of energy extraction, payback period, and so on, are the main parameters that help to determine the greenhouse dryer performance analysis. Performance analysis parameters help to evaluate how new modifications installed on the dryer work.

8.1. Studies Conducted on Natural Convection Greenhouse Dryers

The batch type industrial dryer was developed by Mathionlakis et al. (1998) for drying vegetables and fruits. CFD FLUENT software helps to replicate the air movement within the drying room. The considered boundary conditions include the fixed mass inflow boundary condition, the no resistance boundary condition and the wall shear stress condition on the bounding domain. Differences between the dryers in several trays were noticed. In some regions of the chamber, non-uniformity was traced. The recorded data available from drying tests and the CFD illustrated a good correlation between the drying rate and the air velocity [88].

Bartzanas et al. (2004) has used FLUENT v.5.3.18 software to conduct the CFD simulation. The simulation was conducted in order to recognize the effects of the vent arrangement on air ventilation inside the tunnel type greenhouse dryer. A commercial CFD code was used for several investigations, such as the impact of configuring a tunnel greenhouse dryer, the ventilation, temperature, and crop airflow patterns. Validating the mathematical model against empirical data was also ascertained. A three-dimensional sonic anemometer was used to determine the airflow patterns, and a tracer gas technique was applied to drive the greenhouse ventilation rate. To study the outcome of four different configurations of the natural ventilation system, the CFD model was used. The ventilation configuration influences the air temperature distributions and the ventilation rate of the greenhouse dryer. It was noted that the computed ventilation rates and the different configurations varied between 10 and 58 air changes/h for an outside wind, with a wind speed of 3 m/s. The wind direction is perpendicular to the openings. The mean air temperature in the middle of the solar tunnel varied from 28.2–29.88 °C when the outside air temperature was recorded at 28 °C [89].

A mathematical model was developed by Jain and Tiwari (2004b) to study the thermal behavior for drying peas and cabbage. Predictions for the greenhouse room air temperature, the crop temperature, and the moisture evaporation rate were made. For computation, MATLAB software was conveniently used for the different greenhouse and ambient parameters. The model was empirically validated. There was a satisfactory agreement between the predicted values and experimental findings. The coefficient of correlation between the crop and the greenhouse room air temperature ranged between 0.77 and 0.97. During drying, the coefficient of correlation for the crop mass ranged between 0.98 and 0.99 [51].

Tiwari et al. (2004) evaluated the convective mass transfer coefficient for drying jaggery inside a roof-type even span greenhouse dryer operating under natural convection conditions. During the experiment, a variety of parameters were measured, such as relative humidity, greenhouse room air temperature, mass evaporated during the drying process, and the temperature of the jaggery. The data collected was utilized in order to evaluate the convective mass transfer coefficient favorably. There was an initial increase in the convective mass transfer coefficient rate, which gradually decreased as the drying process continued. It was experimentally established that the convective mass transfer coefficient varied from 1.29–1.41 W/m2·K under natural convection drying conditions [68].

Sacilik et al. (2006) presented a mathematical model demonstrating the effects of the solar tunnel drying system that was exposed to ecological conditions in Ankara, Turkey, when drying a thin layer of a tomato. The organic tomatoes were dried using open sun drying and with a solar tunnel drying system. The duration of time required for the drying process to obtain a predetermined final moisture content of 11.5% from an initial moisture content of 93.35% (w.b.) using a solar tunnel drying system and open sun drying was four days and five days, respectively. Mathematically calculating the diffusion model reduces the root mean square error because of the higher coefficient of determination; thus, it is opined that this model will reduce the monetary value of drying by obtaining a better quality of dried products [70].

Kumar and Tiwari (2006) developed a thermal mode that was capable of predicting and recording the greenhouse air temperature, moisture evaporation rate, and jaggery temperature hourly when using the greenhouse drying system for the complete drying process of jaggery under natural convection conditions. The investigated analysis and the predicted values were in close agreement. The coefficient of correlation for greenhouse air and the jaggery temperature ranged between 0.90 and 0.98 and the jaggery mass during drying ranged between 0.96 and 1.00. The thermal model was proposed as being very conducive when designing the greenhouse dryer, and for investigating a thin layer of the known mass of jiggery [54].

Turhan (2006) proposed two new heavy-duty greenhouse dryers that operated under natural convection conditions. These dryers were examined under both load and no-load conditions. The comparative analyses were conducted after drying the same amount of pepper in a dryer and under the same climatic conditions. The pepper placed in the dryer was found to be of superior quality after drying. In comparison with open sun drying, the proposed dryer was found to be two and a half times (250%) more efficient [72].

The effects of airflow have also been analyzed by examining the dryers with and without a chimney. The results of the experiments revealed that the greenhouse dryers increase the inside air temperature by 5 to 9 °C compared with the ambient temperature. The chimney of the dryer facilitates a better airflow by enhancing the air velocity. It was also concluded that to avoid spoilage and to maintain the nutritional value of the product; these dryers must be successfully employed to dry various agricultural products such as fruits and vegetables. These dryers, in particular, are better utilized in wet areas or in climatic zones with high density [87].

Janjai et al. (2011) predicted the performance of a greenhouse dryer that dried bananas, chilis, and coffee by developing a thermal model. Parameters such as temperature, relative humidity, and moisture content were analysed. A comparative analysis of a solar greenhouse dryer was conducted under open sun drying conditions. The same quantity of bananas was taken and exposed for an equal time of five days. The moisture content differed between 68 and 20% (w.b.) in the greenhouse dryer, whereas it differed between 68 and 29% (w.b.) under natural sun drying conditions.

Similarly, the moisture loss regarding chilis was reduced from 75 to 15% (w.b.) in the greenhouse dryer within three days. In contrast, using an identical quantity and time duration, the moisture content of the chilis when exposed to open sun drying conditions was only reduced from 75 to 42%.

The moisture content with respect to coffee was reduced from 52 to 13% (w.b.) within two days, whereas under natural solar drying conditions, to reach the final moisture content value, it took four days; thus a realistic agreement was found between the theoretical and experimental moisture contents of chilis, bananas, and coffee [71].

Prakash and Kumar (2014) presented the ANFIS (Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System) model for the drying of jaggery in the greenhouse dryer under natural convective conditions. The aim of the experiment was to forecast the jaggery temperature, the greenhouse air temperature, and the moisture evaporation for the jaggery, which was placed inside the greenhouse dryer, which operated under natural convection conditions. For drying jaggery, a roof-type even spans greenhouse dryer was selected, with a floor area of 1.20 × 0.78 m2. MATLAB software develops the ANFIS model, which was used to forecast the thermal performance of the greenhouse dryer based on the solar intensity and the ambient temperature. The developed model was experimentally validated, and it was found that there was good agreement between the experimental and analytical results for the drying of jiggery [90].

Prakash and Kumar (2016) recorded the thermal performance for a modified greenhouse dryer, subjecting it to natural convection and no-load conditions from January 2013 to May 2013. The concept of the opaque north wall was applied with three different floor conditions consisting of a barren floor, a black painted floor, and a black PVC sheet covered floor. The experiment was conducted in order to record the thermal performance of the dryer. Based on empirical data, different thermal performances, such as dimensionless numbers (Nusselt, Grashof, Prandtl, and Rayleigh numbers), the coefficient of diffusion, the heat transfer coefficient, and heat loss, were analyzed. The floor covered with a black PVC sheet was found to be the most useful for crop drying in the experimental study conducted by Prakash and Kumar. It provides a relatively higher room air temperature and lower room humidity [81].

Amjad et al. (2015) experimented on the flow simulation to predict the air distribution in the drying chamber (batch type dryer) for drying potato slices with a thickness of 4 mm using ANSYS-FLUENT CFD. A proposal including a diagonal airflow inlet channel that aligns with the length of the drying chamber was put forward for this dryer. The coefficient of correlation was recorded to be 87.09% for the airflow distribution of this experiment [91].

Chauhan and Kumar (2016) analyzed the performance of a greenhouse dryer with an insulated north wall under natural convection conditions in June 201.Two separate experiments were conducted, one with a solar collector and another without a solar collector. A thermal analysis that took the coefficient of diffusivity, coefficient of performance, heat utilization factor, and convective heat transfer coefficient into consideration was evaluated. The difference between the highest convective heat transfer coefficients of the two cases was 29.09 W/m2C. The inside room air temperature of the dryer for days 1, 2, and 3 were recorded as 4.11 %, 5.08%, and 11.61%, respectively. The inside room temperature of a dryer with a solar collector is comparatively higher than a dryer without a solar collector [64].

Chauhan and Kumar (2017) analyzed the performance of greenhouse dryer with an insulated north wall under natural convection and no-load conditions during October 2014. For two different cases (i.e., case I and case II), specific experiments were conducted. Case I described a greenhouse dryer with an insulated north wall that was assisted by a solar air heating collector on the ground’s surface. In contrast, Case II described a greenhouse dryer with an insulated north wall, without solar air heating collector, on the ground’s surface. A performance analysis of the newly developed system based on the convective heat transfer coefficient, heat loss factor, coefficient of diffusivity, heat utilization factor, and coefficient of performance was conducted. The maximum relative value of the coefficient of performance and the heat utilization factor was recorded as being 0.9 and 0.68 for case I, and 0.86 and 0.61 for case II. For three days (i.e., Day 1, Day 2, and Day 3), the inside room temperature was recorded as being higher in comparison to ambient air at rates of 46%, 42%, and 32%, respectively. The developed system was thus recommended for fruit/vegetable drying based on results which validated the modification [49].

8.2. Studies Conducted on Forced Convection Greenhouse Dryers

Condori and Saravia (1998) modified a simple model to study the evaporation rate of two different types of forced convection greenhouse drying systems (i.e., one with a double chamber and the other with single chamber). The mathematical modelling for two kinds of dryers was taken into account for the dryer design parameters and the product drying kinetics. The two concepts introduced in this article were the dryer performance curve and the generalized drying curve. The generalized drying curve served as a reference for the time–variable parameter, as well as for the received energy from the sun parameter, and the operative parameters. The dryer performance curve delineated production efficiency. The drying potentials, product water content, and metrological variables were calculated using two non-dimensional variables. After the simulation and calculations, the author decided that incorporating some developments into the system could favorably improve the drying potential, which, in turn, could further enhance the production rate. With identical drying areas, regarding the double chamber system, the productivity increased by 87%, compared with the single-chambered system. To further reduce the drying cost, some essential changes were made to the double chamber drying system in order to make it more simple and less expensive [58].

An analytical model was developed by Condori and Saravia (2003) to study the performance of the tunnel type greenhouse dryer. The greenhouse was assumed to be a solar collector. A linear function was obtained between the incidental solar radiation and the greenhouse output temperature. The dryer’s characteristic functions determined dryer performance. It was observed that almost constant production occurred daily. As compared with the single-chamber dryer, an improvement of 160% in production was seen in the simulation test on red sweet pepper, whereas in the case of the double chamber dryer, the improvement was only 40% [73].

Tiwari et al. (2004) measured the convective mass transfer coefficient for drying jaggery under forced convection conditions in the roof type even span greenhouse dryer. Dissimilar parameters were calculated at the time of the experiment, such as greenhouse room air temperature, the temperature of jaggery, relative humidity, and mass evaporated. The range of the convective mass transfer was found to be between 1.3 W/m2·K and 1.46 W/m2·K. The data certified that the convective mass transfer coefficient for the forced convection mode was higher than the natural convection mode [68].

Jain and Tiwari (2004) examined thermal modelling in order to study behavioral patterns when drying cabbage and peas that were subjected to forced convection conditions; these conditions were based on ambient temperature and solar intensity for the prediction of the rate of evaporation, crop temperature, and greenhouse air temperature. The experimental value and predicted values were found to be in good agreement in terms of percentage deviation and root square error. The range for the coefficient of correlation and root mean square error was recorded as 0.92–0.99 and 3.88 to 8.43, respectively [92].

Jain (2005) proposed a transient analytical model to study the effect of the packed bed thermal storage inside the even span greenhouse dryer. The packed bed thermal storage was used to replace the north wall of the dryer. The performance evaluation of a crop was undertaken by using onion for the case study. The dimensions of the greenhouse drying system were 6 m in length, 4 m in breadth, and 0.25 m in height. For similar climatic conditions, all the experiments were performed in May, in New Delhi, India. The focus of this experiment was to study the effect of the mass flow rate of air, the dimensions of the greenhouse dryer, and the temperature of the crop. Initially, it was found that the rate at which the removal of moisture occurred, in addition to the drying rate, was rather high, but after 4 h, the rate at which the removal of moisture occurred, and the drying rate of the crop diminished considerably. The temperature of the north wall of the dryer reached 84 °C when operating during peak solar radiation hours. During the 24 h study it was observed that when 2280 kg of onion was allowed to lose moisture and be dried at an effective height of 0.25 m, the mass flow rate was recorded as being 0.278 kg/s. The initial moisture content was recorded as 6.14, and it was reduced by up to 0.21 kg water/kg of dry matter. The thermal energy storage had a significant effect, even in off-peak sunshine hours, and it proved to be useful for the reduction in temperature fluctuations. The proposed model was found to be very useful in the performance analysis conducted by the author [74].

Kumar and Tiwari (2006) performed thermal modelling of a greenhouse drying system for drying jaggery under forced convection conditions. In this experiment, the roof type even spans greenhouse dryer, with a 1.20 × 0.78 m2 floor area, was used to dry 2 kg of jaggery that was specifically prepared with dimensions of 0.03 × 0.03 × 0.03 m3. For four consecutive days in March, the experiments were performed in the IIT Delhi, and data were recorded on an hourly basis. The effects arising from changes in the air, relative humidity, air temperature, and changes in the mass of the jaggery was observed on an hourly basis. The experimental and theoretical results show a perfect agreement that is reflected through the records wherein the coefficient of correlation ranges between 0.96 and 0.98. Moreover, the percentage of the square root of deviation ranged between 6.75 and 12.63%. During experimentation, it was observed that the number of air changes per hour had a remarkable effect on greenhouse air temperature and drying jaggery. With the increase in the number of air changes per hour, there was a decrease in greenhouse air temperature [69].

Janjai et al. (2009) developed the PV- ventilated solar greenhouse dryer to conduct a performance analysis of the process wherein peeled longan and bananas are dried. A parabolic roof, covered with polycarbonate plates that have a concrete floor, constituted the structure of the dryer. A 50 W photovoltaic module runs three fans to ventilate the air from the dryer. To study the performance of the greenhouse dryer, five experiments were conducted separately to dry both bananas and peeled longan. The temperature range varied when drying peeled longan, from 30 to 58 °C, and when drying bananas, the temperature varied between 30 and 60 °C. The drying time for drying peeled longan and bananas using open sun drying was six days and five days, respectively. Moreover, under similar ambient conditions in a greenhouse dryer, it takes three days and four days, respectively. The experimental data obtained were used to develop a partial differential equation in order to describe the moisture and heat transfer at the time of drying the banana and peeled longan. It was further solved numerically using a finite difference method. These models may be utilized for providing optimal design data for greenhouse dryers [75].

Krawezyk and Badyda (2011) have developed a mathematical model for sewage drying that involves applying fluent computational fluid dynamics software in a forced convection GHD. The unsteady condition of the sludge inside the solar dryer was created in order to help the flow and thermal processes depending upon its thermodynamic characteristics and drying conditions (solar radiation, change over time, the humidity of ventilated air and temperature) [93].

Janjai (2012) developed a thermal model wherein a forced convection greenhouse dryer has a parabolic roof structure to dry tomatoes. Thermal modelling was conducted in order to investigate the performance of the dryer. The drying capacity of the greenhouse dryer was approximately 1000 kg. Hot air was supplied to the dryer continuously during the rainy season by attaching a 100 kW LPG gas burner onto the dryer. The dryer had to be utilized in order to dry the three batches of osmotically dehydrated tomatoes. When compared with open sun drying, this experiment illustrated that the drying time was reduced by 2–3 days and the drying air temperature of the dryer ranged between 35 and 65 °C [94].

Prakash and Kumar (2013) presented ANFIS (an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system) model to predict the relative humidity and the greenhouse air temperature in the modified greenhouse dryer operating under forced convection conditions. The experimental results validated the predicted values. A reliable correlation between the predicted and experimental data was found. The total magnitude of error was only 0.026 for the prediction of the greenhouse dryer’s room air temperature [95].