Abstract

A smart grid is an intelligent power grid. In recent years, the smart grid environment and its applications are incorporated into a variety of areas. The smart grid environment, however, can expose much more information than the old environments. In the environment, smart devices can be media in the exposure of various and specific pieces of information as well as energy consumption. This poses a huge risk in that it, combined with other pieces of information, may expose much more information. The current smart grid environment raises a need to develop anonymous signature and authentication techniques to prevent privacy breaches. Trying to meet this need, the principal investigator conducted research for three years. This paper discusses both the research trends investigated by him and the limitations of the development research and future research in need. Smart grid security requires the development of encrypted anonymous authentication that is applicable to power plant security, including nuclear power plants as well as expandable test beds.

Keywords:

security; power plant; cryptography; anonymous signature; authentication; smart grid; micro grid 1. Introduction

In recent years, the Korean government has been preparing mid-term and long-term cultivation plans, whose core lies in new energy business in the trade market of demand-side resources to purchase and sell saved electricity [1]. The core axis is comprised of micro grids and smart grids capable of managing the small-scale power systems of various distributed energy resources to generate and use electricity directly from new renewable energy along with an Energy Storage System (ESS) and Energy Management System (EMS) [2,3].

Following this keynote, the Korean government has expectations for the profit and job creation of a new business convergence model in a smart grid based on ESS and EMS including electric vehicles [4]. A smart grid is a technology to incorporate information and communication technologies into the power grid, collect information about the amount of electricity used and the conditions of power lines, and enable the efficient use of power. The smart grid area consists of five major elements including Smart Power Grid (intelligent power grid with information technologies incorporated in it), Smart Place (residential environment for two-way communication between power suppliers and consumers), Smart Electricity Service (TOC and power trade service at an integrated management center), Smart Transportation (charging technologies and infrastructure for electric vehicles), and Smart Renewable (upscale power quality and stable connections of new renewable energy) [5,6,7]. A smart grid system has recently served many places from smart homes to smart factories, smart farms, power plants, and smart cities in a convergence form [8]. Smart grids and the multiple systems linked to them adopt the group signature technique, which is an electronic signature technique to allow a signer to prove his or her membership of the group without revealing his or her identity [9,10]. The verifier can judge whether a signature is given by a member of the group or not but has no means to figure out his or her identity.

In other words, a smart grid environment can expose much more information than the old environments. Various and specific information can especially be exposed via smart devices in addition to energy consumption. This poses a huge risk in that the combination of information can lead to the exposure of much more information.

There are many survey papers in the smart grid field [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. These papers all offer explanations about a smart grid and its functions, but they are distinguished from one another according to their main sub-domains. Refs. [11,14] mainly cover the general characteristics and overall summary of the smart grid field. Ref. [11] is especially differentiated for its coverage of policies in various nations. In [12,16], the authors classify technologies needed in a smart grid, provide explanations about each of them, and propose their respective major challenges and future directions. In [21], the authors focus on Internet of Things (IoT) technologies to explain their relations with a smart grid and discuss the IoT structures used in a smart grid, applications, services, challenges, and future research. Refs. [19,20] explain applications using Big Data in a smart grid with a focus on the literature addressing the massive amounts of data (Big Data) generated from a smart grid, discussing major challenges in the Big Data management of a smart grid. Ref. [19] deals with the communication of a smart grid, offering explanations about the communication network structures and applications of smart grids. The study also identifies the overlapping issue to be conquered between power and communication systems, explains the current state of the communication system designs, and makes recommendations about various traffic functions. Refs. [13,15,17,22,23] provide information with a focus on the cybersecurity of a smart grid environment, cover the important issues and scenarios of cybersecurity and propose directionality to solve the issues. Refs. [17,22,23], in particular, emphasize blockchain technologies, reviewing papers on the utilization of blockchain technologies and proposing directions for future research on their utilization. In this paper, the survey focuses on anonymous signature and authentication techniques to prevent privacy breaches, addressing security among the many challenges of a smart grid.

The current smart grid environment raises a need to develop anonymous signature and authentication techniques to prevent privacy breaches. Trying to meet the need, the principal investigator conducted research for three years. This paper discusses both the research trends investigated by him and the limitations of the development research and future research in need.

Concerning the proposed limited connectivity, its main objective is to avoid providing the information that does not need to be disclosed to malicious users. Its merit is not only protecting personal information by minimizing unnecessary disclosure but also making it possible to provide useful services to the users in a stable and reliable manner without any concerns of malicious users.

2. Related Research

A group signature is a kind of digital signature for users to verify that they are members of a certain group [24]. This technique does not reveal a user’s ID and allows the verifier to judge whether a signature was entered by a verified member without identifying a user. In this technique, an “opener” has special authority to identify users with group signatures and trace users that commit inappropriate acts in an anonymous service.

Various applied research has been conducted to apply a group signature [25,26,27]. Linkability grants a linker, who has no authority to identify certain users, the authority to check whether many different group signatures are created by the same single user. Linkability, however, has the weakness of users not being able to trust a linker that is not a third party that is completely trusted, such as an opener. A user has, for instance, uploaded two posts, A and B, on an anonymous bulletin board and wants to delete A. He or she can delete it only after a linker checks that the two postings (A and B) were written by the same person. Since a linker is not a third party that the service provider of a user can fully trust, he or she can check different articles created by the same signature. The goal of this function is to prevent malicious abuse. This raises a need for a system that offers proper linkability to minimize the privacy breach of users [28].

Privacy breach issues are part of the major issues occurring in a service that requires user authentication. A privacy protection system was introduced to ensure that users maintain their anonymity by revealing only encrypted information or some of the user information to a system administrator. Such a system offers a variety of security levels and means, which can be sometimes insufficient [29]. Homomorphic encryption [30] is thus used usually as a next-generation security technique to enable the processing and usage of well-known anonymous signatures [31] or data in encrypted conditions [32].

In an anonymous signature, for instance, Party 1 signs on a message created by Party 2 without any knowledge of its content. Party 3 can receive the message, and the user behind it can have his or her identity protected, as Party 2’s signature is not authenticated on the message. In homomorphic encryption, certain mathematical or calculation methods are added to a message or text to write a coded message so that only the authenticator with the right decoding key can decipher encrypted messages.

A smart meter applies the homomorphic encryption method on average to encode requirements and send them to the central control system. Certain encryption functions are used for a system to decode content with a proper decoding key. Such a system was developed as an electronic voting system to conceal voter information in the application hierarchy, but it did not take into account the possibilities of information leakage in the lower hierarchy (link or network hierarchy) of the protocol stack. The same IP addresses are used repeatedly in the system, which can be used as a means for hackers to access the communication ID or analyze traffic [33].

This function can, however, lead to privacy breach issues. When there is a huge amount of data generated, this function poses a possibility that a third party with malicious intention might look into the daily lives of clients with the data containing more information. Some nations reported a finding that the use of a smart meter exposed clients’ security/privacy to greater risks [34].

There is a tradeoff between efficient and effective smart metering and the guarantee of personal information protection at a proper level, and it is the focus of controversy. A solution, the purpose of which is to protect privacy with the terms of [35], should guarantee clients a proper level of anonymity and temporary unlinkability (that is, the deactivation of power consumption readings). Such a solution may, however, face an issue over whether linkability can be realized or should be fully realized even when clients pay a bill. The same question can be raised for the unobservable state in which others are not allowed to observe a client’s power consumption. It is possible to keep the records of total power consumption at the power plant level, but data should still be transmitted to the main system so that a smart meter system can be fully activated [29,35,36].

2.1. Smart Grid and Security

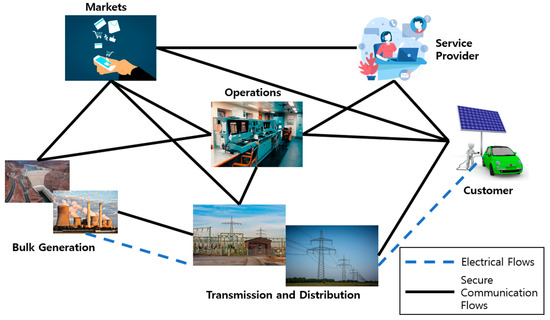

A smart grid is part of a computer and power infrastructure network to monitor and manage energy consumption. An energy producer runs a management center that receives usage information from a smart meter that reports on each client’s power consumption. A smart meter is directly connected to home appliances and smart devices, offering various additional functions including the control of connected devices [37]. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) explains that the following domains interact with each other in a smart grid [38]. Figure 1 shows the interactive domain on smart grid [38].

Figure 1.

Interactive Domain on Smart Grid.

A smart grid requires the development and application of massive computer and communication infrastructure to enable perception, orders, and control for a variety of certain situations. A smart grid consists of major applications that make up information, communication, and control systems. A system in such a complicated structure has a lot of security vulnerabilities. Security is an important matter in a smart grid environment that has many different issues to solve. Many kinds of research are in progress to identify and solve such vulnerabilities.

Gunduz and Muhammed Zekeriya et al. offered explanations about the key elements of a smart grid and surveyed the attack types according to the objective and network hierarchies of cybersecurity [39].

H. Khurana et al. categorized the security vulnerabilities and challenges of a smart grid into trust, communication and device security, privacy, and security management for explanations [40]. Fadi Aloul et al. gave explanations about the components of a smart grid with a special focus on network components divided into home area networks and wide area networks before adding more explanations about network vulnerabilities and attack types and proposing solutions for security challenges [41].

Anibal Sanjab et al. provided explanations about security threats related to the vulnerability of a smart grid and challenges to be solved and proposed solutions [42].

Anthony R. Metke and Randy L. Ekl explained the cases of security vulnerability and the development of demanded smart grid security and proposed a couple of solutions including Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) standards and trust anchor security [43].

Mo, Yilin et al. defined a smart grid as a new security issue that required a new approach to the cybersecurity field and called it cyber-physical security, which maintains that the old security approaches are not proper for very complicated environments such as a smart grid and offers examples to show whether the combination of cyber- and system-theoretic approaches can provide a higher level of security [44].

2.2. Privacy Infringement in Smart Grid

A smart grid is an essential technology whose application should take into consideration environmental benefits as well as diverse economic issues, which is why many countries around the globe have conducted a good number of technological investigations to promote the spread of a smart grid for the last several years [45]. There should be an array of technologies, including sensors, information and communication, to introduce a smart grid. A smart grid is an intelligent next-generation power grid that keeps evolving in new ways. Many countries around the globe have conducted a lot of technological research for the distribution of a smart grid for many years. Above all, the top priority that should be taken into consideration in the distribution of a smart grid is the protection of personal information. This is different from a common security viewpoint and should be understood in the viewpoint of preparing the basic ability to protect privacy on the part of users rather than service providers.

A smart grid environment can expose much more information than the old environments. There is a risk that various and specific information can especially be exposed via smart devices in addition to energy consumption. The combination of such information increases the possibility of exposing more private life information that is more accurate. A major issue of personal information protection in relation to the distribution of smart grid technologies is that behavioral inferences can be made from energy usage data based on the collection and analysis of more detailed personal identification data about individuals’ energy consumption and the nature and frequency of production following the introduction of the latest electric meters and the installation of related devices and technologies. A smart meter electronically collects and transmits data instead of a manual measuring instrument to be read and collected, thus raising a methodological surveillance issue. The ability to figure out the patterns of certain home appliances or consumers depends on the frequency of information collection by a measuring instrument and the nature of data collected by a measuring instrument. It makes it easy to infer information about activities happening at one’s residence or other places, thus causing a serious privacy breach.

The following scenarios of breaches can happen to the protection of personal information in a smart grid: First, information breaches can happen involving information about the use of certain medical and electronic devices that show the time of operation and personal patterns (in advanced nations, hospitals use a smart grid system for auxiliary purposes to deal with power interruptions following an accident), as well as detailed usage information about home appliances and devices used at certain locations including the fragmented data of the power consumption of each home appliance at certain measurement locations; and secondly, new energy consumption data such as the charging of electric vehicles can be traced for its physical location. Breachers can also make inferences about activities in a house or building based on the electronic signatures and time patterns of devices. Such signatures and patterns can be used as grounds to figure out the owner’s activities. It is thus necessary to restrict the scope of collecting energy usage data by a third party to the information needed to fulfill the purposes granted by consumers such as the provision of a service or product.

2.3. Anonymous Authentication Method and Anonymous Signature Method

Anonymous authentication is a cryptological technology that offers an authentication requester anonymity and allows him or her to demonstrate he or she is a legitimate entity. When a simple false name is used for anonymity, the user’s marks can be traced as they are, which is why a false name is not generally regarded as an anonymous authentication technology. Many kinds of research on anonymous authentication introduced group signatures [46] and anonymous credentials [47]. The group signature technique is an electronic signature technique that allows a signer to demonstrate he or she is a member of the group without revealing himself or herself. The verifier can judge whether a signature belongs to a member of the group but cannot figure out his or her identity. This technique offers an opener to a third-party agency (e.g., the police and Korea Internet & Security Agency) that can be trusted. An opener has the authority to figure out the identity of a signer and trace the identity of a user that has committed an inappropriate action such as an illegal act in an anonymous service. Since it offers traceable anonymity, the technique is known as the most practical one applicable to real world applications such as web application services.

A group signature technique is characterized by soundness and completeness (correctness), unforgeable, anonymity, unlinkability, and exculpability [47]. Table 1 shows group signature property and definition [48].

Table 1.

Group Signature property and definition.

The group signature technique, in general, provides anonymity, traceability, and unlinkability. There is a group manager to set parameters based on the members, an opener to have the authority to trace certain group signatures, a signer, and a verifier. The signers within the same group have different respective secret keys (group signature keys), and the verifier can verify whether a signature is right or wrong with a group open key. Group signature values contain encrypted information to distinguish signers, and only the opener can trace the identities of group signers with an open key to reveal actual signers based on such values.

2.4. Present Condition of Smart Grid Security Technology in the Republic of Korea

As markets have long developed around unit products in the Republic of Korea (ROK), overall security technologies in the nation are vulnerable. There should be a holistic security model to promote the proper utilization of the competencies accumulated through the development of unit technologies. A smart grid is comprised of many different devices including Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) and networks, thus having hackers’ diverse invasion routes distributed in it. It is difficult for a smart grid to prevent all attacks in advance, which raises a need to examine damage cases and many elements involving such attacks and prepare countermeasures for the types of high damage risk first.

According to the “Calculation Cases of Security Damage Costs in a Smart Grid based on AMI Attack Scenarios” released by the Korea Institute of Information Security and Cryptology, there are two million smart meters distributed around the nation, and 10% of them suffered damage due to an attack. In five different assumptions, including the one involving the replacement of all the smart meters that were damaged, the costs of one loss case amounted to 37.19 billion won in total, which is such a considerable cost.

When many different devices are linked together, a discovery of their security vulnerability will cause enormous economic damage cases. An entire city can be paralyzed just with a simple system hacking event, not to mention the leakage of personal information. The trend of recent cyberattacks leads to a prediction that cyberattacks will pose bigger threats in the future and even develop into national security issues.

How are the concerned industries dealing with security issues in the Korean-type smart grids? Encryption was not applied to the introduction of smart grid technologies at their early stage, which has rendered their security highly vulnerable. Trying to solve these security issues, the concerned industries apply an encryption module chip certified through the Korea Cryptographic Module Validation Program (KCMVP) to AMI modems. Encryption modules are a collective term for hardware, software, and firmware to perform encryption functions including codes, generation of random numbers, hashes, electronic signatures, prime number determination, and certification. They can block access from a third party through the encryption of devices, thus being used to solve security issues in a smart grid.

In ROK, there are several organizations devoted to the development and application of encryption modules including the Korea Electric Power Corporation (Naju City, Republic of Korea), Korea Minting and Security Printing Corporation (Daejeon City, Republic of Korea), and Keypair. The Korea Electric Power Corporation developed an encryption module KEPCOCF V1.0 in November 2017 and joined the KCMVP. In the latter part of 2018, it started to introduce the KCMVP encryption modules of other organizations along with KEPCOCF V1.0 to its AMI, which is the intelligent metering infrastructure capable of remote two-way communication. The number of AMI units was predicted to reach four million by November 2018. On 31 October 2018, the Korea Minting and Security Printing Corporation developed an in-house encryption module KShell42 Crypto V1.0, joined KCMVP, and made a plan for its active utilization in IoT and smart metering in which information security was essential through an encryption algorithm service. Following these public enterprises, a security specialist start-up Keypair also joined KCMVP on the same day as the Korea Minting and Security Printing Corporation. Keypair has developed universal KSE100B and advanced KSE300B, which are security modules with built-in KCMVP encryption modules. The Korea Minting and Security Printing Corporation and Keypair are participating in AMI module tenders by the Korea Electric Power Corporation with their respective encryption modules. Three organizations, which are the Korea Electric Power Corporation, Korea Minting and Security Printing Corporation, and Keypair with their encryption module certification, are competing against each other to be selected by AMI manufacturers in their AMI modem business.

As competition gets increasingly fiercer in the encryption module market, one might wonder how much encryption models can solve the security issues of a smart grid.

An official of the Korea Electric Power Corporation argued that the application of an encryption module chip with the KCMVP certification should keep security at the highest level, but the academic circles are saying differently.

First, its encryption module KEPCOCF V1.0 has no random number generators and security memory to save keys unlike the secure element-based encryption modules of the Korea Minting and Security Printing Corporation and Keypair, which raises a big possibility that its security might still be vulnerable. Its encryption model receives encrypted entropy inputs, which are initial values to generate random numbers, from the outside and uses its random number generator to general random numbers. In this structure, private and public keys for electronic signature purposes generated in the corporation’s PKI are encrypted and saved in memory. According to the corporation, if a hacker has no access to secret keys, he or she will receive no information even by hacking the memory. As far as it is concerned, its encryption module structure guarantees security stability. The academic circles, however, refute this by pointing out that the corporation will still need random numbers to encrypt entropy inputs themselves that will generate random numbers through encryption. The question is how it will generate random numbers. They also point out that the encryption of private and public keys for electronic signature purposes will still lack safety as the secret keys to be decoded are saved in the flash memory in a clear text.

Secondly, the corporation has not held mock hacking rounds to find the limitations of its encryption module, which points to the lack of its effort to react to the hacking technologies that are gradually upgraded. When asked about the reason behind no simulations to find vulnerabilities, the corporation answered that its module was also verified for vulnerability by getting the KCMVP certification. After the corporation completed its PKI in 2019 for future simulations, the National Intelligence Service recommended checking the management of its AMI encryption key security and diagnosing them for vulnerabilities. The KCMVP certification does not ensure that an encryption module is free from all future security issues. Hacking technologies develop as much as security technologies or further. It is critical to perform hacking simulations and test vulnerabilities consistently, and the concerned departments and industries should work together for these.

The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy has released plans to support the smart grid industry, but the overall road map of the smart grid industry is weak to support the industry in security issues more specifically, which poses another obstacle to the resolution of security issues. The stability of the smart grid industry can be secured by making plans in advance to cope with a sudden security crisis in the future. The first task is to discard the lackadaisical attitude that encryption modules will make security issues go away easily [49].

2.5. Security Threats in Smart Grid

There are three types of security threat factors in a smart grid: the first one is a control system threat, which happens following a sophisticated attack on an AMI/Smart Meter. If a smart meter has no proper security functions in place, hackers can attack its RAM directly and find an easy route to eliminate or control the meter. Even if a smart meter has security functions to some extent, hackers can extract information from it with a separate device. If a hacker connects to a smart meter program, he or she can spread malicious codes including attack worms or other malware to devices attached to the meter. A Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack can follow to paralyze the entire system by requesting a simultaneous connection to the target computer via a zombie PC infected with malicious codes. That is, hackers can attack the entire smart grid system via the connected network once they secure an attack base. This can cause personal damage narrowly and even lead to a national disaster involving a massive blackout more broadly [50,51,52,53]. Table 2 shows security threats in smart grid.

Table 2.

Security threats in Smart Grid.

There have been massive blackout events and resulting national damage cases due to cyber-breach events in the power sector. In June 1999, the database of the control system was run by the state of Washington in the United States of America (USA) [54,55,56,57]. It went down after a cyber hacking accident, and it led to the explosion of Olympic Gasoline pipelines and massive damage. In 2007, Brazil suffered a massive blackout and damage of approximately seven million dollars due to hacking.

In July 2009, ROK witnessed more than 110,000 PCs infected with malicious codes due to DDoS attacks. These massive cyber attacks caused an economic loss of fifty billion won [58,59].

American economist Scott Berg developed a four-stage model to explain phenomena in a prolonged blackout event when the power grid is paralyzed by simultaneous cyberattacks: Stage 1 falls on Blackout Day 1 and sees people suffering inconvenience; Stage 2 falls on Blackout Day 3 with people panic buying daily necessities (products run out in stores) and find it impossible to operate all kinds of devices; Stage 3 falls on Black Day 10 and witnesses the start of massive population migration and casualties; and Stage 4 falls on Blackout Month 3 and sees people rioting and causing damage at a disaster level. When a blackout lasted for 25 h in New York in 1977, approximately 1700 stores were plundered, 4000 people were arrested, and property damage of 150 million dollars was caused. These cases clearly show that cyberattacks can lead to national disasters and cause very serious damage. If a smart grid becomes a major power grid in the future, the risk of cyber-breach events will be highly likely to accompany one such as a tag.

The second one is a network threat. As a smart grid is linked to an Internet network, hackers can target parts and control systems with vulnerable Internet security to attack. A variety of IoT devices used in a smart grid including meters are vulnerable to security issues as security is a lower priority than development and economy. These devices can be controlled remotely, being connected to the Internet. These characteristics create a set of conditions for hackers to invade a meter via a wireless network device in the meter. As mentioned earlier, they can attack the entire smart grid system after the control system.

Large-scale cyberattacks via Internet connections has already occured. In 2016, Mirai Botnet (the aggregation of many computers that received remote control attacks from the outside, being connected to the Internet) suffered DDoS attacks as a hacker invaded IoT devices vulnerable to security issues such as CCTVs and IP cameras. He made public a malicious code online to avoid tracking, and attacks happened in a relay. These attacks even rendered Internet connection impossible on the eastern coast of the USA.

A single malicious code had a strong striking power because many devices were distributed and connected in various ways on the Internet. A smart grid is a power grid in which various devices are connected to one another in complex ways via the Internet. If each device lacks security measures, an entire smart grid will suffer huge damage due to the complex connection of devices.

The third one is a consumer security threat. The energy usage information of each household is saved in a smart grid, which can expose consumers’ personal information. People have shown no big concerns with their energy consumption data as metermen should personally visit a household or building and obtain data from an electricity meter physically to secure energy consumption data, which only covers a limited period of one month. AMI, however, provides real-time energy consumption information, showing the living patterns of individual consumers. The collection and usage of personal information according to energy consumption are essential to the management of a smart grid, but such personal information can be used for purposes other than power supply, which may cause a privacy breach issue.

In the United States, the Cybersecurity Task Force in charge of privacy protection issues in a smart grid carried out a Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) and raised a lot of concerns and issues regarding the leakage of personal information. Privacy breach issues, however, are yet to be fully known. The agencies that collect information related to a smart grid have no procedures and policies in place to prevent privacy breaches.

There should be measures to promote the right utilization of personal information so that smart grid participants can be deterred from deviating from the original collection purposes such as excessive information gathering and improper use of information. A smart grid should have policies, standards, procedures, and technical elements in place to deal with privacy breach issues.

Roughly, three measures are being considered (DDoS). First, controlling the attacker’s access with a DNS security service. Second, the utilization of a cloud service. Since it is rather unrealistic to have a high level of security level and maintain it in a small and limited smart grid, it would be more beneficial to provide such a smart grid with a cloud service platform. In this way, the local network can have a higher level of security offered by the cloud service as well as an advantage of relatively easier maintenance. Third, a Big Data-based preemptive detection and blocking, with which malicious access will be detected rapidly and blocked based on the accumulated Big Data.

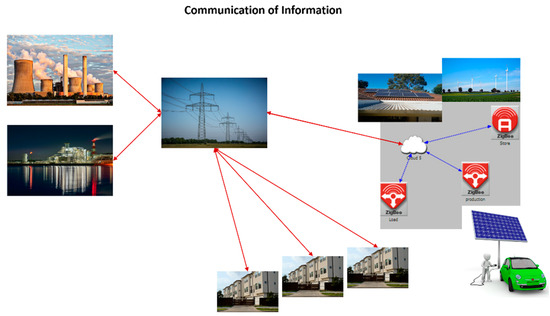

Meanwhile, a smart grid is a convergence technology to promote the real-time two-way communication of power information between the power supplier and consumers and maximize energy efficiency based on such information by incorporating ICT (Information and Communication Technology) in the old power grid. Countries around the world agree on the intellectualization of a power grid as a response to climate changes on Earth and make diverse efforts to build a smart grid [60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. Figure 2 shows communication of information in smart grid.

Figure 2.

Communication of Information in Smart Grid.

Particularly in ROK, a smart grid construction project is being pushed forward to prioritize the commercialization of the business models from the test bed project on Jeju Island, which was completed recently, to certain areas and spread them around the nation [63,66,67,68,69].

In addition, an interoperability test center is also being established to help large-scale network infrastructure secure interoperability among devices in a smart grid in advance. One of the important issues that emerge along with the efforts to build a smart grid is the security of a smart grid. As ICTs are incorporated into the power grid as the foundation of national business, the old security threats of ICTs are inherited into the power grid, which can cause national damage at a disaster level. As many devices are scattered around the nation in a smart grid, invaders can access them easily online and offline and attack them to cause hindrance to the devices and servers [70,71,72]. They can also forge, doctor, and leak important data on the communication network, causing huge damage personally and socially. A communication security service encompassing authentication, data integrity and confidentiality, non-repudiation, and network access control is required to deal with unauthorized access and security threats to communication data in a smart grid. Research is in progress on various authentication and key management technologies that will meet the communication security requirements of a smart grid. Researchers are investigating PKI-based security solutions by taking into account the smart grid environment comprised of many devices and entrepreneurs and conducting active research on efficient authentication and key management technologies and frameworks for smart grid devices with lower hardware performance [73,74,75,76].

2.6. Countermeasures for Smart Grid Security Threats

Wenye Wang et al. classified countermeasures for smart grid security attacks by dividing them into network countermeasures for DoS attacks that actively induce network traffic dynamics and cryptographic countermeasures for attacks targeting integrity and confidentiality [13]. On the other hand, in [15], a cyber security response system consisting of three phases, pre-attack, under-attack, and post-attack, was proposed. First, in the pre-attack phase, there are response systems corresponding to network security, cryptography for data security, and device security. In the under-attack phase, it is largely classified into two tasks: attack detection and attack mitigation. Finally, in the post-attack phase, first, the attack-related entities are identified, and then security policy is updated to protect them from similar attacks in the future. There is also a forensic analysis technique used in the post-attack phase.

In [77], smart grid attacks are classified into smart meter, physical layer, data injection and replay, and network-based attacks, and countermeasures are described in detail for each attack. On the other hand, in [78], attacks are classified into metering infrastructure, decryption, denial of service, control and monitoring attacks, and countermeasures from the perspective of infrastructure, decryption, and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) are presented.

Roberto Vigo et al. describe countermeasures against security breaches according to attack classification under the assumption that an attack is detected. The authors classified the attacks as confidentiality, integrity, availability, and non-repudiation [79]. Similarly, in [8], attacks in the smart grid environment are classified into six categories: (1) Confidentiality and privacy, (2) Integrity, (3) Authenticity, (4) Non-repudiation, (5) Availability, and (6) Authorization, and some popular countermeasures are introduced with them.

Shama Naz Islam et al. proposed key generation/management mechanisms, anomaly detection, resilience techniques against smart grid cyber attacks, and spread spectrum techniques as countermeasures to mitigate physical layer attacks [80]. Table 3 shows a summary of the research papers in countermeasures for smart grid security threats.

Table 3.

Summary of the research papers in countermeasures for smart grid security threats.

2.7. Challenges and Solutions for Smart Grid Security Threats

Various research papers classify and explain various security threats according to the attack method, attack time, and attack target. According to each classification, challenges and solutions for smart grid security are presented.

El Marbet, Z. et al. explains that the smart grid environment can cause accidental breaches and vulnerabilities during the protocol conversion process between communication because different devices communicate through various network protocols. To solve this problem, it is proposed that cyber attacks on the smart grid can be effectively mitigated by combining several security mechanisms rather than simple or specific security technologies [15].

Muhammed Zekeriya Hunduz and Resul Da classified attack types for cyber security objectives and presented solutions. Five conditions, which are essential for the security framework for the smart grid are presented [39]: (1) Authentication and access control for communication must be strictly applied throughout the smart grid, (2) Attack detection and response must be applied everywhere in the smart grid, (3) Attack detection and response must be applied everywhere in the smart grid, (4) All nodes must have lightweight cryptographic functions by default, and (5) It is essential to implement a cyber security test bed platform for vulnerability investigation of power infrastructure.

Another paper mentions the need for specific new security solutions for smart grid networks and describes the many challenges facing security solution development. The authors propose 14 solutions to the challenges [41].

Anthony R. Metke et al. show examples of security vulnerabilities exposed in North America and describe organizations that address cyber security challenges. Authors suggested more effective solutions for smart grid security, including technical elements of PKI standards, smart grid PKI tools, device attestation, trust anchor security, and certificate attributes which would be PKI-based technologies [43].

In [81], a detection approach to counter cyber attacks on the smart grid was surveyed. Due to the variability, complicity, and intelligence of network attacks, a single specific solution is not enough, and solutions that consider physical and cyber security at the same time are present.

On the other hand, ref. [82] focused on AMI security among the components of the smart grid. The challenges of AMI security and Key Management System (KMS) for the purpose of AMI security are categorized and explained. It also presents future research issues, challenges, and directions for AMI. Table 4 shows summary of the research papers in challenges and solutions for smart grid security threats.

Table 4.

Summary of the research papers in challenges and solutions for smart grid security threats.

3. Proposed Idea

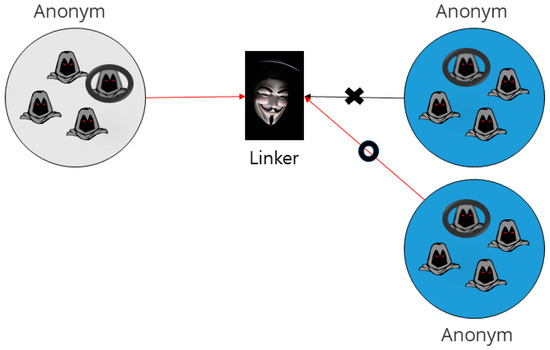

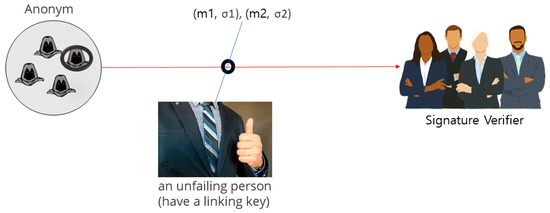

This principal investigator has researched linkability to promote the flexible utilization of the group signature technique in application. Linkability refers to the ability of the linker to judge whether a signer is responsible for two groups of signatures. Unlike the opener who is a third-party agency that can be trusted by service users in the old group signature techniques offering linkability, the linker is a service provider or an agency designated by a service provider, which means that service users can be exposed to additional risks of privacy breaches. In this study, the investigator defined “limited linkability” as a new feature that allowed only the linker designated by the signer to check linkability only for the messages designated by the signer and designed a group signature technique to provide limited linkability. Using the proposed group signature technique, the investigator developed an anonymous authentication technique to minimize privacy exposure and utilized the technique found in various research. Figure 3 shows group signature technique providing linkability

Figure 3.

Group signature technique providing linkability.

The development of a “group signature technique providing linkability controllable by users,” which allows users to select and offer only the information they want, offers a source technology to minimize privacy exposure and enables high quality anonymous service in next-generation business areas including IoT, medical healthcare systems, and intelligent vehicle systems as well as smart grids.

3.1. Group Signature Method Based on Connectivity

Many kinds of research have been conducted on linkability to apply group signatures to more diverse applications. Linkability is the ability of the linker to judge whether a single signer is responsible for two groups of signatures. Here, the linker can figure out whether two different signatures values are from the same signer or not, but he or she cannot figure out the identity of the signer. In the smart grid environment, service providers can increase their service quality by analyzing Big Data, including the real-time power usage patterns of service users, and processing it as meaningful information. In other words, they can not only reinforce privacy protection by offering anonymity through group signatures, but also provide flexible service by connecting themselves to the data of the same anonymous user via linkability. Hwang Jeong-yeon et al. [24] introduced a group signature technique to provide local linkability.

In their research, the linker has linking keys generated by the group manager and is usually a service provider. The linker also has the authority to check whether all the signature values are connected or not. Figure 4 shows group signature method.

Figure 4.

The group signature method.

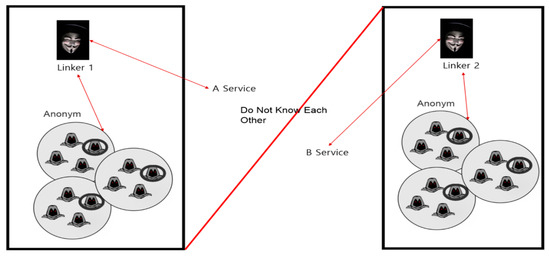

In this paper, the group signature scheme that provides limited connectivity is a technique that a user’s signature is presented by the user-designated arbitrary linker while guaranteeing anonymity, not by the centralized institutions. It has a basic structure of User—Linker Authorization and require one arbitrary linker. Even though the number of linkers does not limit the service availability, a multiple number of linkers means that the advantage of designating a single linker could be lost, becoming not much different from the security provided by the group signature schemes that offers existing connectivity. For this reason, ideally the same number of linkers are required as the number of services being provided.

3.2. Group Signature Technique to Provide Limited Linkability

The old group signature techniques providing linkability have the linker instead of the opener who is a third-party agency that service users can trust. The linker is a service provider or an agency designated by a service provider, thus exposing service users to further risks of privacy breaches. Figure 5 shows group signature method based on connectivity.

Figure 5.

The group signature method based on connectivity.

Regarding the limited connectivity proposed in this paper, it has been designed based on the reliability of a linker. Its object is to reduce the amount of unnecessary personal information the existing centralized linkers have and if the reliability of the distributed linkers is lost, the system will not perform normally. For this, roughly three approaches have been prepared. First, connecting with a credible (reliable) linker. Although there are no restrictions for the linkers in the proposed signature scheme, it is not a bad idea to secure minimum level of reliability by qualifying those linkers who meet minimum standards or limitations.

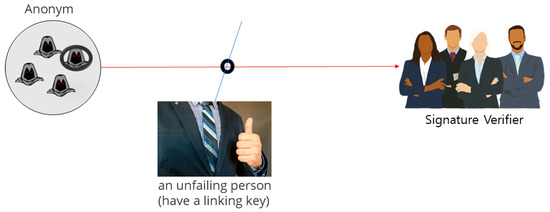

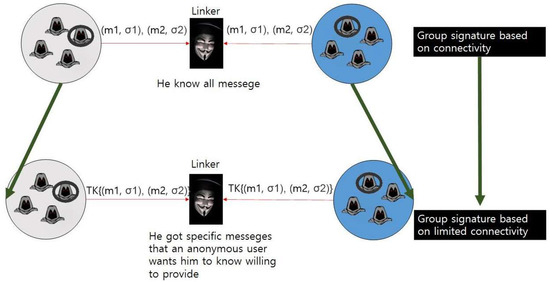

Second, letting multiple linkers to check their individual opponent’s reliability. Assuming that there is a micro-network consisted of many nodes, all the nodes can perform as a linker and supposing that half of them are legitimate users, the same test signatures are requested to more than three linkers to confirm the majority and for the ones who made a minor opinion, an additional separate qualification process can be carried out. Third, applying PoW. For example, a calculation that requires a certain period of time to solve is transported to the network along with a signature after being encrypted with the open secret key in the network. Then each node decrypts the data with the open public key. In this way, the data encrypted with the secret key can be verified by multiple nodes and the modified/falsified data will be ignored. Figure 6 shows group signature-based other scenario.

Figure 6.

The group signature-based other scenario.

For instance, an anonymous user A uses the power consumption analysis service and IoT system. In this case, a service provider can link information about the power consumption and IoT of A that signs with the same group signature key. That is, the service provider has no idea of A’s identity but can additionally figure out whether the same person uses the two services or not, which poses a potential privacy breach element that the user does not want. Unlike previous studies on the old group signature techniques in which the linker designated by the system serves as a system administrator to test the linkability of the entire signature values, the proposed research will develop a group signature technique that allows the linker designated by a signer to test the linkability of the signatures that the signer wants and secure a source technology to prevent the exposure of information more than necessary. In the case above, the anonymous user A can send his or her power consumption values to the linker for linkability testing with the same group signature key and make information about IoT eligible for linkability testing before sending it to the linker. This scheme minimizes the risk of unnecessary personal information exposure and protects users from privacy breaches. Figure 7 shows group signature based on limited connectivity.

Figure 7.

The group signature based on limited connectivity.

In this study, the investigator defined “limited linkability” as a new feature for the linker designated by a signer to check the linkability of only the messages designated by the signer, designed a group signature scheme to provide limited linkability, and developed an anonymous authentication technique to minimize privacy exposure with the proposed group signature scheme.

4. Conclusions

In the smart grid and power plant environments, the breach threats of user privacy must be solved first as sensitive data including the trade specification data and location information of a user can be offered to a service provider and attacker and used for malicious purposes. The group signature technique is widely used as a cryptological primitive anonymous authentication, which verifies a user is a legitimate one without revealing his or her identity, and can serve as a means of responding to privacy breaches in the smart grid and power plant environments.

In the future work, it would be possible to show the efficiency of the limited connectivity proposed in this paper by comparing the amount of information exposed to malicious users in each communication after dividing the two test groups: one with the existing connectivity and the other with limited connectivity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-M.J., H.W., J.C., S.-H.J. and J.-H.H.; data curation, S.-M.J., H.W., J.C., S.-H.J. and J.-H.H.; formal analysis, S.-M.J., H.W., J.C., S.-H.J. and J.-H.H.; funding acquisition, S.-H.J. and J.-H.H.; methodology, S.-M.J., H.W., J.C., S.-H.J. and J.-H.H.; resources, S.-M.J., H.W., J.C., S.-H.J. and J.-H.H.; software, S.-M.J., H.W., J.C., S.-H.J. and J.-H.H.; supervision, S.-H.J. and J.-H.H.; validation, S.-M.J.; visualization, S.-M.J. and J.C.; writing—original draft, S.-M.J., H.W., J.C., S.-H.J. and J.-H.H.; writing—review and editing, S.-M.J., H.W., J.C., S.-H.J. and J.-H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the MSIT (Ministry of Science and ICT), Korea, under the Grand Information Technology Research Center support program (IITP-2022-2020-0-01489) supervised by the IITP (Institute for Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation). Furthermore, this work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No.2017R1C1B5077157).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ESS | Energy Storage System |

| EMS | Energy Management System |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| PKI | Public Key Infrastructure |

| ROK | Republic of Korea |

| AMI | Advanced Metering Infrastructure |

| KCMVP | Korea Cryptographic Module Validation Program |

| DDoS | Distributed Denial of Service |

| USA | United States of America |

| PIA | Privacy Impact Assessment |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| KMS | Key Management System |

References

- Brown, M.A.; Zhou, S. Smart-grid policies: An international review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. Wiley 2013, 2, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinho, K.; Hong-Il, P. Policy directions for the smart grid in Korea. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2010, 9, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.-T.; Yoon, M.; Jung, J.; Huh, H.-J. Microgrid System Comprising Energy Management System of Energy Storage System (ESS)-Connected Photovoltaic Power System; United States Patent Application Publication: Germantown, MD, USA, 2022; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jae-Chul, K.; Sung-Min, C.; Hee-Sang, S. Advanced power distribution system configuration for smart grid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2013, 4, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Jun-Ho, H. Smart Grid Test Bed Using OPNET and Power Line Communication; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–425. [Google Scholar]

- Ussama, A.; Muhammad Arshad Shehzad Hassan, U.F.; Asif Kabir, M.Z.K.; Sabahat, S.H.; Bukhari, Z.A.J.; Judit Oláh, J.P. Smart Grid, Demand Response and Optimization: A Critical Review of Computational Methods. Energies 2022, 15, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nejabatkhah, F.; Li, Y.W.; Liang, H.; Reza Ahrabi, R. Cyber-security of smart microgrids: A survey. Energies 2020, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komninos, N.; Philippou, E.; Pitsillides, A. Survey in smart grid and smart home security: Issues, challenges and countermeasures. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2014, 16, 1933–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Shen, J.; Vijayakumar, P.; Cho, Y.; Chang, V. A practical group blind signature scheme for privacy protection in smart grid. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2020, 136, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Choo, K.K.R.; He, D. Blockchain-based anonymous authentication with key management for smart grid edge computing infrastructure. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 16, 1984–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuballa, M.L.; Michael, L.A. A review of the development of Smart Grid technologiesm. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 59, 710–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Misra, S.; Xue, G.; Yang, D. Smart grid-The new and improved power grid: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2011, 14, 944–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhuo, L. Cyber security in the smart grid: Survey and challenges. Comput. Netw. 2013, 57, 1344–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Ghadir, R. Survey on smart grid. In Proceedings of the IEEE SoutheastCon 2010 (SoutheastCon), Concord, NC, USA, 18–21 March 2010; pp. 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- El Mrabet, Z.; Kaabouch, N.; El Ghazi, H.; El Ghazi, H. Cyber-security in smart grid: Survey and challenges. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 67, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colak, I.; Sagiroglu, S.; Fulli, G.; Yesilbudak, M.; Covrig, C.F. A survey on the critical issues in smart grid technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, M.B.; Zhao, J.; Niyato, D.; Lam, K.Y.; Zhang, X.; Ghias, A.M.; Koh, L.H.; Yang, L. Blockchain for future smart grid: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 18–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafi, N.S.; Ahmed, K.; Gregory, M.A.; Datta, M. A survey of smart grid architectures, applications, benefits and standardization. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2016, 76, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daki, H.; El Hannani, A.; Aqqal, A.; Haidine, A.; Dahbi, A. Big Data management in smart grid: Concepts, requirements and implementation. J. Big Data 2017, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tu, C.; He, X.; Shuai, Z.; Jiang, F. Big data issues in smart grid–A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasempour, A. Internet of things in smart grid: Architecture, applications, services, key technologies, and challenges. Inventions 2019, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Musleh, A.S.; Yao, G.; Muyeen, S.M. Blockchain applications in smart grid–review and frameworks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 86746–86757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, P.; Zamir, T.; Liang, H. Blockchain for cybersecurity in smart grid: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaum, D.; Van Heyst, E. Group signatures. In Advances in Cryptology-EUROCRYPT; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; pp. 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Domingo-Ferrer, J.; González-Nicolás, U. Balanced trustworthiness, safety, and privacy in vehicle-to-vehicle communications. IEEE Trans Veh. Technol. 2010, 59, 559–573. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Chung, B.H.; Cho, H.S.; Nyang, D. Short group signatures with controllable linkability. In Proceedings of the 2011 Workshop on Lightweight Security & Privacy: Devices, Protocols, and Applications, Istanbul, Turkey, 14–15 March 2011; pp. 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Chung, B.H.; Cho, H.S.; Nyang, D. Group signatures with controllable linkability for dynamic membership. Inf. Sci. 2013, 222, 761–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungwook, E.; Jun-Ho, H. Group signature with restrictive linkability: Minimizing privacy exposure in ubiquitous environment. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungwook, E.; Jun-Ho, H. The Opening Capability for Security against Privacy Infringements in the Smart Grid Environment. Mathematics 2018, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Marmol, F.; Sorge, C.; Ugus, O.; Perez, G. Do not snoop my habits: Preserving privacy in the smart grid. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2012, 50, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, J.; Chim, T.; Yiu, S.; Li, V. Credential-based privacy-preserving power request scheme for smart grid network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference, Kathmandu, Nepal, 5–9 December 2011; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zeadally, S.; Pathan, A.; Alcaraz, C.; Badra, M. Towards privacy protection in smart grid. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2013, 73, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badra, M.; Zeadally, S. Design and Performance Analysis of a Virtual Ring Architecture for Smart Grid Privacy. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secure. 2014, 9, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenkamp, R.; Huitema, G.B.; de Moor-van Vugt, A.J. The neglected consumer: The case of the smart meter rollout in the Netherlands. Renew. Energy Law Policy Rev. 2011, 2, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ptzmann, A.; Hansen, M. A Terminology for Talking about Privacy by Data Minimization: Anonymity, Unlinkability, Undetectability, Unobservability, Pseudonymity, and Identity Management. Available online: http://dud.inf.tu-dresden.de/Anon_Terminology.shtml (accessed on 9 September 2018).

- Tudor, V.; Almgren, M.; Papatriantafilou, M. Analysis of the impact of data granularity on privacy for the smart grid. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM Workshop on Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society, Berlin, Germany, 4–8 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, P.; McLaughlin, S. Security and privacy challenges in the smart grid. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2009, 7, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, G.W.; Wollman, D.A.; FitzPatrick, G.; Prochaska, D.; Holmberg, D.; Su, D.H.; Hefner, A.R., Jr.; Golmie, N.T.; Brewer, T.L.; Bello, M.; et al. NIST Framework and Roadmap for Smart Grid Interoperability Standards; Release 1.0; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2010. Available online: https://tsapps.nist.gov/publication/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=904712 (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Gunduz, M.Z.; Das, R. Cyber-security on smart grid: Threats and potential solutions. Comput. Netw. 2020, 169, 107094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, H.; Hadley, M.; Lu, N.; Frincke, D.A. Smart-grid security issues. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2010, 8, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloul, F.; Al-Ali, A.R.; Al-Dalky, R.; Al-Mardini, M.; El-Hajj, W. Smart grid security: Threats, vulnerabilities and solutions. Int. J. Smart Grid Clean Energy 2012, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanjab, A.; Saad, W.; Guvenc, I.; Sarwat, A.; Biswas, S. Smart grid security: Threats, challenges, and solutions. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.06992. [Google Scholar]

- Metke, A.R.; Randy, L.E. Smart grid security technology. In Proceedings of the 2010 Innovative Smart Grid Technologies (ISGT), Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 19–21 January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Y.; Kim, T.H.J.; Brancik, K.; Dickinson, D.; Lee, H.; Perrig, A.; Sinopoli, B. Cyber-physical security of a smart grid infrastructure. Proc. IEEE 2011, 100, 195–209. [Google Scholar]

- Fadaeenejad, M.; Saberian, A.M.; Fadaee, M.; Radzi, M.A.M.; Hizam, H.; AbKadir, M.Z.A. The present and future of smart power grid in developing countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaum, D. Security without identification: Transaction systems to make big brother obsolete. Commun. ACM 1985, 28, 1030–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaum, D.; van Eugène, H. Group signatures. In Workshop on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-G.; Han, S.W.; Lee, S.J.; Jeong, B.H.; Yang, D.H.; Gwon, T.G. The Technology and Trend of Anonymous Authentication. Electron. Telecommun. Trends 2008, 23, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Renewable Energy Followers. Available online: https://renewableenergyfollowers.org/2807 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Lee, C.H. Information Protection System and Countermeasures for Korean Smart Grid. Internet Inf. Secur. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.M.; Kim, N.G.; Kim, Y.G. Smart Grid Security Technology Trend Analysis and Response Plan. J. Korean Inst. Commun. Sci. 2014, 31, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2nd Master Plan for Intelligent Power Grid. Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy. 2018. Available online: http://www.motie.go.kr/motie/in/ay/policynotify/announce/bbs/bbsView.do?bbs_seq_n=64958&bbs_cd_n=6 (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Kim, H.J.; Park, C.G.; Seo, G.T. A study on the Legal and institutional improvement for building and utilizing a secure smart grid. Korea Energy Econ. Inst. 2012, 1–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hyo-Jung, J.; Tae-Sung, K. A Case Study of the Impact of a Cybersecurity Breach on a Smart Grid Based on an AMI Attack Scenario. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Secur. Cryptol. 2016, 26, 809–820. [Google Scholar]

- Yong-Hee, J. Smart Grid Security Characteristics and Issues Analysis based on the Internet of Things (IOT). J. Korea Inst. Inf. Secur. Cryptol. 2014, 24, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nocutnews. Available online: https://www.nocutnews.co.kr/news/5057909 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Nocutnews. Available online: https://www.nocutnews.co.kr/news/5057648 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Dailysecu. Available online: https://www.dailysecu.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=47444 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Energy Newspaper. Available online: http://www.energy-news.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=61283 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Cctvnews. Available online: http://www.cctvnews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=114171 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- ZDNet Korea. Available online: http://www.zdnet.co.kr/view/?no=20181114204759 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Ajunews. Available online: https://www.ajunews.com/view/20181108142904553 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Jaeduck, C. Security Trends in Authentication and Key Management for Smart Grid Devices. J. Korea Inst. Electron. Eng. 2013, 40, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Quan, Y.; Sharif, H.; Tipper, D. A Survey on Smart Grid Communication Infrastructures: Motivations, Requirements and Challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2013, 15, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gungor, V.C.; Sahin, D.; Kocak, T.; Ergut, S.; Buccella, C.; Cecati, C.; Hancke, G.P. A Survey on Smart Grid Potential Applications and Communication Requirements. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2013, 9, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- NISTIR 7628 Revision 1, Guidelines for Smart Grid Cybersecurity: Vol. 1, Smart Grid Cybersecurity Strategy, Architecture, and High-Level Requirements. September 2014. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/nistir/7628/rev-1/final (accessed on 7 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Metke, A.R.; Ekl, R.L. Security Technology for Smart Grid Networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2010, 1, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, T. Adapting PKI for the Smart Grid. Proc. IEEE Smart Grid Comm. 2011, 1, 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Fouda, M.M.; Fadlullah, Z.M.; Kato, N.; Lu, R.; Shen, X.S. A Lightweight Message Authentication Scheme for Smart Grid Communications. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2011, 2, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Kwon, E.Y.; Kim, M.; Cheon, J.H.; Ju, S.H.; Lim, Y.H.; Choi, M.S. A Secure Smart-Metering Protocol Over Power-Line Communication. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2011, 26, 2370–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qinghua, L.; Guohong, C. Multicast Authentication in the Smart Grid With One-Time Signature. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2011, 2, 686–696. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, N.; Sam, K.; Xiaoyu, D.; Elisa, B. Authentication and Key Management for Advanced Metering Infrastructures Utilizing Physically Unclonable Functions. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Third International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm), Tainan, Taiwan, 5–8 November 2012; pp. 324–329. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.; Rose, Q.H.; Das Sajal, K.; Hamid, S.; Yi, Q. An Efficient Security Protocol for Advanced Metering Infrastructure in Smart Grid. IEEE Netw. 2013, 27, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Nian, L.; Jinshan, C.; Lin, Z.; Jianhua, Z.; Yanling, H. A Key Management Scheme for Secure Communications of Advanced Metering Infrastructure in Smart Grid. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2013, 60, 4746–4756. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.D.; Seo, J.T. Separate Networks and an Authentication Framework in AMI for Secure Smart Grid. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Secur. Cryptol. 2012, 22, 525–536. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Ohba, Y.; Kanda, M.; Famolari, D.; Das, S.K. A key management Framework for AMI Networks in Smart Grid. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2012, 50, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, Z.A.; Amouid, A.R. An Analysis of Smart Grid Attacks and Countermeasures. J. Commun. 2013, 8, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.; Sargolzaei, A.; Santana, H.; Huerta, C. Smart grid cyber security: An overview of threats and countermeasures. J. Energy Power Eng. 2015, 9, 632–647. [Google Scholar]

- Vigo, R.; Yüksel, E.; Ramli, C.D.P.K. Smart grid security a smart meter-centric perspective. In Proceedings of the 2012 20th Telecommunications Forum (TELFOR), Belgrade, Serbia, 20–22 November 2012; pp. 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.N.; Zubair, B.; Sherali, Z. Physical layer security for the smart grid: Vulnerabilities, threats, and countermeasures. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 6522–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Sun, H.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.L. A survey on security communication and control for smart grids under malicious cyber attacks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 49, 1554–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, A.; Mauro, C. Key management systems for smart grid advanced metering infrastructure: A survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2831–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).