Abstract

Insufficient environment protection may have serious ecological consequences, resulting in a number of problems in the modern world, many of which are a direct result of human behavior. Therefore, one needs to limit negative ecological effects by consciously shaping environment-related behaviors. The present paper analyzes the declared attitudes of individuals when it comes to taking into consideration pro-environmental factors, including energy, consumption, and waste. We have also studied the social awareness of the socially responsible investment idea, as well as pro-ecological individual behaviors related to private finance. Our survey study, conducted on a representative sample of 1030 Polish respondents, shows that participants’ individual features have little impact on pro-ecological decisions, and that declared pro-ecological attitudes are not reflected in actual behaviors. Polish consumers are still not active enough in making decisions concerning pro-ecological actions, first of all, in terms of energy and waste. As a result of the conducted research, we suggest increasing all activities in the field of environmental policy that could increase the participation of society in facilitating sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The evolution of both social relations and ecological relations between humans and nature is a well-known phenomenon [1]. Given their significance and complexity, environmental issues have been a subject of study since the 1960s [2]. As many ecological problems stem from human actions, influencing those actions may become the solution. Hence, the pro-environmental behavior (PEB) concept was created. It aims at influencing human behavior in a conscious way. Such influencing would allow for limiting, as much as possible, the negative effects of human actions on the environment [3]. Many different theoretical models have been created which analyze the correlation between influencing human behavior and the actual human impact on the environment. They include the Norm Activation Model (NAM) [4], the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [5], the Model of Responsible Environmental Behavior [6], Schwartz’s theory of basic human values [7], the Value–Belief–Norm theory (VBN) [8], and the model of pro-environmental behavior [9]. The heterogeneous nature of pro-environmental behavior (PEB) makes it a very complex issue, and dependent on a number of internal and external factors. Research studies also point to various types of goals determining the level of engagement and the methods used by those involved in pro-ecological actions. Moreover, PEB may be analyzed by taking into consideration the type and range of impact (direct or indirect; global or local) [10]. The existing analyses of factors influencing PEB stress the importance of personal and social factors [11]. Different behaviors are attributed to men and women [12,13,14]; broader analyses point out the correlation between age and place of residence and the decisions of individuals concerning ecology and finance [15]. However, those decisions depend not only on individual features, but, also, on the features of an entire family or household [16]. Often, a decision-making process may be attributed to a household as a whole, rather than to its individual members. Let us note that the existing literature does not offer clear data concerning the range and impact force of the various factors influencing PEB. The different results are related to a number of differences observed, concerning geography, culture, economic growth, income, the specificity of each professional group, gender, knowledge levels, education, or age [17,18,19]. One of the basic correlations which has become the subject of numerous studies is the impact of environment education (EE) on pro-environmental behavior. Once again, research results seem inconclusive. Part of the studies show the positive impact of EE on PEB. According to those analyses, the development of EE results in an increase in PEB in society [20,21]. It is particularly clear when it comes to behaviors/areas concerning resource management, such as recycling [22] and energy- and water-saving behaviors [23]. Moreover, a study by D. De Silva and R. Pownall shows that well-educated respondents are more likely to spend more or bear greater costs if additional ecological benefits are involved. However, the impact of income levels on such behaviors also needs to be taken into consideration [24]. Other studies, on the other hand, have pointed out a number of doubts and limitations concerning the correlation between EE and PEB. In light of those facts, it is no longer obvious that the development of EE resulting in increasing environmental knowledge has an actual impact on shaping intended ecological behaviors [9,25,26]. Nevertheless, education remains an important tool for enhancing environment awareness, which also translates into the subjective feeling of being ecological.

As we have stated before, insufficient environment protection has a number of ecological consequences, and remains a serious problem in the modern world. Therefore, environment protection turns out to be crucial in many aspects, including the financial one. Both international and Polish financial markets seem interested in investments related to ensuring environmental protection [27,28]. Considering its potential, the financial market may be used to a much greater extent than before to ensure environmental protection through the so-called Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) [29,30]. SRI stresses the importance of aligning investment goals with the principles of socially responsible growth, aiming at ESG: Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance [28].

In certain conditions, environment education may considerably affect environmental attitudes and behaviors of individuals, which translates into their financial decisions [31]. The financial market investing in compliance with ecological aspects may simply be qualified as an “ecological financial market”. Within this market, a growing number of offers may be observed, aiming at investors [32]. Taking into consideration the ecological evolution in socioeconomic life, it is also important to analyze private finance (finance concerning individuals), which plays a crucial role in the functioning of the modern society. However, the impact of environmental care needs on individual preferences, concerning investment, may be considered quite limited [33]. Moreover, even those applying socially responsible investment schemes pay much more attention to factors nonrelated to responsible, ethical, or ecological policies [28,34]. Pro-ecological decisions in private finances may concern different types of behaviors, such as consuming goods and services [35], consuming water [36] and electricity [37], tourism, and travel [38], but, also, volunteer work [39]. Although some of those behaviors are subject to legal regulations, individuals may still make choices according to their preferences and take into consideration a number of factors [40,41,42].

Hence, we may assume that the financial market may be further put to use in order to enhance the ecological economic transformation. It certainly presents a great challenge for the economy, individuals, the state, and science.

Another important aspect resulting from pro-ecological behaviors is environmental maturity stages. Ormazabal et al. [43] described environmental maturity stages for companies, concentrating on the various approaches to this topic presented in the literature. Inoue et al. [44] point to the fact that one can measure maturity level based on the length of time since a given facility adopted International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 14001 standard. Liu [45] stresses the correlation between economic development and environmental protection, showing that the greatest environmental damage may be observed in medium-income countries. The association between environmental concern and country-level affluence was also observed by Summers and Van Heuvelen [46].

However, do Paço et al. [47] point out considerable differences between individuals within each country when it comes to ecology-related behaviors [48]. Hence, the present paper discusses different ecological behaviors of Poles, which could provide an overall image of the Polish ecological market. Our analysis, concentrating on pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors, is not a comparative one. Rather than comparing pro-environmental behaviors and attitudes in Poland to those observed in other countries, we study the correlation between those behaviors and the individual features of each respondent [49].

Due to the specificity of economic and social conditions in Poland, the problem of including pro-ecological questions in the financial decisions of individuals is still quite an undeveloped topic in this country. As a result, research is also scarce. Some studies [14,50,51,52] partially cover this complex topic. Considering this research gap, and that fact that there is no consensus as to the list, range, and scale of factors influencing the pro-ecological financial behaviors of individuals, we decided to conduct a study on the subject. Hence, the aim of the paper is to present financial behaviors related to environment protection in Poland. The objectives include determining the impact of pro-environmental factors on consumer decisions, analyzing SRI awareness levels, and verifying the possible correlations between the level of awareness and the participants’ individual features, as well as describing pro-ecological behaviors of Poles connected with private finance. We will attempt to verify the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Level of education affects pro-ecological behaviors of individuals in the financial market.

Hypothesis 2(H2).

Men and women present similar pro-ecological behaviors.

Hypothesis 3(H3).

There is a correlation between declared and actual ecological behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

The survey was conducted by a professional opinion polling entity, in July and August of 2020. The omnibus survey was conducted using CATI (Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing) methods on a representative sample of 1030 people, including variables such as gender, age, education, and place of residence. We conducted probabilistic sampling in the form of random stratified selection, which assumed dividing the entire general population into smaller subgroups known as strata. Random samples were selected from each stratum. During the research, due to the assumed sample of 1030 fully conducted interviews, additional records from the strata were added to achieve the assumed sample size.

The survey included 10 closed-ended questions, 4 of which included additional open options. Given the type of data collected and the fact that the survey included dichotomous and nominal-scale variables, the survey questionnaire has not been validated. It stemmed from the fact that the aim of the analysis was to characterize the role of attitudes and behaviors related to environment protection in the financial decisions of consumers, rather than to elaborate a proper evaluation scale for describing pro-ecological behaviors related to financial decisions. The present study, which is a continuation of a long-term research process conducted by the authors, was able to establish the level of ecological awareness of the respondents and their level of commitment when it comes to pro-ecological issues. We then analyzed whether those attitudes actually translated into pro-ecological investment decisions.

For statistical analyses, nonparametric tests and a Pearson’s contingency coefficient (C) were used. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the respondents.

Table 1.

General presentation of survey participants.

We concentrated on the analysis of selected questions concerning pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in the financial decisions of individuals (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Survey questions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Self-Evaluation of an Individual’s Pro-Ecological Attitudes

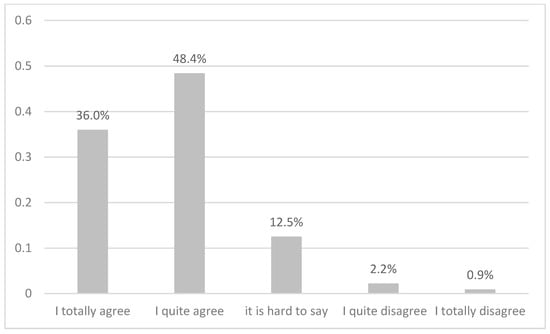

The first part of our study concerned the participants’ declarations as to the impact of pro-environmental factors on their everyday decisions. Our respondents were quite unanimous in declaring that ecology guided their life choices. The answers to question Q1 are presented in Figure 1. Let us note that this question concerned declared behaviors rather than actual ones.

Figure 1.

Survey responses to “Do you consider your everyday decisions to be guided by environment protection factors?” question. Source: own elaboration.

We then evaluated the correlation between the self-declared pro-environmental attitudes (Q1) and the basic features of our respondents (AGE, GEN, RES, T_EDU, L_EDU, C_FIN), and their evaluation of the financial situation of their household. Among the different participant characteristics, only education level turned out to be statistically relevant (Pearson chi-square p-value = 0.022; C = 0.166) (Table 3). For those who declared that their everyday life decisions were influenced by pro-environmental factors (answering “I definitely agree” or “I quite agree” to Q1), the “level of education” variable value was most often secondary (41.8%, 34.5%) or basic vocational (27.8%, 29.7%). The weakest correlation concerned those with primary (0.8%, 1.0%) and lower secondary education (14.6%, 13.5%).

Table 3.

Contingency coefficients (Pearson’s coefficient) for using environmental criteria in everyday life, awareness of SRI, and pro-ecological decisions vs. individual characteristics of respondents.

We also established a level of correlation between one’s declared pro-environmental attitudes (Q1) and one’s actual pro-environmental actions and behaviors, including ecological investment (Q3–Q7). Our study has not confirmed any statistically significant correlation between an individual’s pro-ecological self-evaluation and their actual actions, i.e., taking into consideration the company’s pro-ecological actions and socially responsible policies, the level of investment risk, the company’s ethical actions, or the fact that a company provides reliable information about its situation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Contingency coefficients (Pearson’s coefficient) for using environmental criteria in everyday life, awareness of SRI, and pro-ecological decisions vs. SRI decisive criteria.

There was also no statistically significant correlation between the level of pro-ecological self-evaluation (Q1) and the tendency to buy an ecological financial product allowing one to obtain less profit than other financial products (Q8), or between the level of pro-ecological self-evaluation and the making of pro-ecological decisions concerning private finance (including making investments on the ecological financial market) (Q2).

We were also trying to establish whether those who considered themselves pro-ecological in making everyday decisions (Q1) were aware of, or familiar with, the idea of socially responsible investment (Q9). Similar to other questions, no statistical correlation was found in this case.

3.2. Self-Evaluation Considering the Level of Awareness of Socially Responsible Investments (SRI)

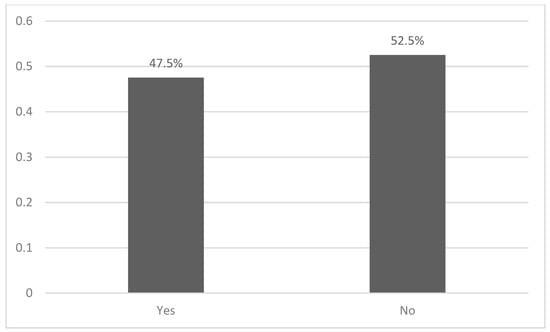

Our study analyzed whether the respondents were aware of the idea of SRI and verified the possible correlations between the level of awareness and the participants’ individual features. Figure 2 presents survey responses to question Q9.

Figure 2.

Survey responses to “Have you heard of Socially Responsible Investment?” question. Source: own elaboration.

There turned out to be a statistically significant correlation between SRI awareness and the respondents’ formal education type (Pearson chi-square p-value = 0.003; C = 0.092) and age (Pearson chi-square p-value = 0.002; C = 0.133). Other variables, such as gender (GEN), place of residence (RES), formal education level (L_EDU), and the individual assessment of one’s household’s financial situation (C_FIN) turned out to be irrelevant. As for the type of formal education, a disproportion in SRI awareness levels could be found between participants who had completed economic studies (55%) and those who had completed other types of studies (45%). As far as age is concerned, SRI was a familiar concept mostly to age groups 25–34 (23%) and 35–44 (22%). Among those unfamiliar with the SRI concept, 21% represented age group 55–64, while 19% belonged to the 65+ age group (Table 3).

Our study also aimed at examining the correlation between SRI awareness (Q9) and real actions involving SRI-oriented investment (including the ecological aspect). The analysis showed no statistically significant correlation between SRI awareness and taking into consideration a company’s pro-ecological actions and socially responsible policies, a company’s ethical actions, or the fact that a company provides reliable information about its situation (Q3–Q4; Q6–Q7), while making financial decisions. However, there was a statistically relevant correlation between SRI awareness and the level of investment risk taken into consideration in making investment decisions (Q5) (Pearson chi-square p-value = 0.047; C = 0.096). In this case, respondents declaring SRI awareness were also more likely to pay attention to investment risks (43%) than those unfamiliar with SRI (37%); they were also less likely to answer “it is hard to say” to the investment risk question (26% compared to 35% among those unaware of SRI) (Table 4).

There was also a correlation between SRI awareness (Q9) and making decisions concerning the purchase of pro-ecological financial products (Q8), even if they provided smaller revenues compared to other financial products (Pearson chi-square p-value < 0.001; C = 0.158). In this case, SRI-aware respondents were more likely to answer “I totally agree” (23% vs. 16% in SRI-unaware respondents) or “I quite agree” (46% vs. 38%) to question Q8. There was also a smaller percentage of undecided respondents in the SRI-aware group (25%) than among those unfamiliar with SRI (33%).

Investigating SRI awareness was also aimed at establishing the possible correlation between this factor and making pro-ecological decisions concerning private finance (Q2). In this case, the correlation turned out to be statistically significant (Pearson chi-square p-value < 0.001; C = 0.166), as SRI-aware respondents were much more inclined to make pro-ecological decisions compared to participants unfamiliar with SRI (44% vs. 30%) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Contingency coefficients (Pearson’s coefficient) for using environmental criteria in everyday life, awareness of SRI, and pro-ecological decisions vs. buying ecological products.

3.3. Pro-Ecological Decisions Concerning Private Finance: Decision Criteria

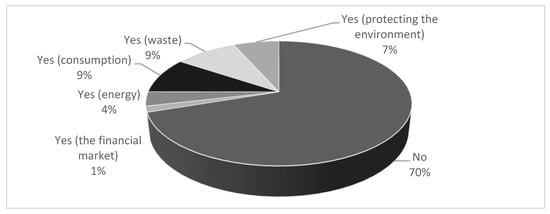

The survey provided statistical data concerning pro-ecological behaviors of Poles connected with private finance, presented in Figure 3 (Q2). Unfortunately, most Poles do not make pro-ecological decisions. Only 30% had made any pro-ecological decision concerning their private finance.

Figure 3.

Survey responses to “Have you ever made a decision concerning pro-ecological actions which was connected to your private finance?” question. Source: own elaboration.

The response distribution shows that pro-ecological decisions (Q2) were made by less than a half of survey participants. Ecologically motivated decisions concerned mostly consumption, waste, and environment protection institutions, with fewer answers pointing to energy and finance sectors. There was also a statistical correlation between pro-ecological decisions and the self-evaluation of one’s household’s financial situation (Pearson chi-square p-value < 0.001; C = 0.137). Respondents judging that their financial situation was good or really good were also more likely to make pro-ecological decisions than others (cf., respectively, 11% vs. 7% and 48% vs. 42%). Other individual features, such as gender, education type and level, or place of residence, turned out to be irrelevant.

Apart from evaluating the relations between making pro-ecological decisions and individual features of the respondents, we have also examined the possible correlation between making pro-ecological decisions (Q2) and SRI decisive criteria. We verified whether survey participants’ decisions were influenced by factors other than benefits and costs, such as ecological actions, socially responsible behaviors, and ethical behaviors of a company, as well as reliable information provided by a company concerning its situation (Q3-Q7). In this case, the only relevant correlation concerned the socially responsible behaviors of companies respondents were willing to invest in (Pearson chi-square p-value < 0.046; C = 0. 178) (Table 4). Among those making pro-ecological investments, more participants paid attention to the socially responsible behavior of the targeted companies (34% vs. 26% in the other group). Respondents making pro-ecological choices were also less likely to answer “it is hard to say” to the question concerning SRI (22 vs. 28% in the other group).

We have also verified whether there was a correlation between pro-ecological decisions concerning private finance and purchasing ecology-supporting financial products (Q8), even if the potential revenues were smaller than in the case of other financial products. There was, indeed, a statistically significant correlation between these two factors (Pearson chi-square p-value < 0.001; C = 0.232) (Table 5). In this case, all respondents declaring to make pro-ecological decisions concerning personal finance tended to choose the “I totally agree” answer to Q8 much more often (in relation to finance, consumption, waste, energy, and pro-environment institutions), cf. 19.3–37.5% vs. 14.5% in other groups. In this group, there was also a smaller percentage of undecided respondents (13.2–29.5% vs. 33.9% in other groups).

4. Conclusions

The analysis presented in this paper provides a list of factors influencing declared and actual pro-environmental behaviors in Poland. Poles consider themselves as individuals guided by pro-environmental concerns while making everyday decisions. They are also familiar with the idea of SRI. However, in reality, they engage in almost no pro-ecological actions (mainly including energy, consumption, and waste) concerning private finance, which refutes our hypothesis H3. The results of our study differ considerably from those obtained in other countries. The differences most probably stem from the fact that the Polish ecological market is still in its primary maturity stage. While Poles already realize the importance of environment protection, they do not individually engage in pro-environmental actions concerning their private finance. Poland is no longer a low-income country; however, the reminiscences of the poverty era before 1989, the difficult post-communist transformation, and the 2007 crisis still play an important role in making financial decisions.

Similar to other research studies conducted in other countries, our analysis has also been inconclusive as to the possible correlation between education and pro-ecological actions. Hence, our hypothesis H1 could not be confirmed, as the impact of education on pro-ecological behaviors seems to be quite limited. It may result from the fact that ecology problems are still somewhat neglected in the education process, which is another proof of the immature nature of the pro-ecological market in Poland. The behaviors of Polish consumers still do not allow for defining them as active consumers in making decisions about pro-ecological activities, primarily in the fields of energy and waste.

Based on the study, we were able to confirm our hypothesis H2, as men and women present similar behaviors concerning pro-ecological behaviors while making financial decisions, regardless of their gender. These gender-neutral results, which differed from the results of other studies concerning the behaviors of men and women in the financial market, may have a simple explanation. Pro-environmental knowledge, behaviors and decisions are, like no others, determined by family factors rather than by the individual features of each family member. It also explains why we found no significant correlation between individual behaviors and the different respondent features we took into consideration. It is the family as a whole, rather than its individual members, who do or do not present pro-ecological behaviors. We may also assume that ecology-related attitudes and knowledge are mainly a family feature; it is rare for each of the family members to present totally different attitudes and behaviors concerning the environment. Since family characteristics of people are relatively stable, changes related to pro-ecological behaviors in Poland are still not progressing at a satisfying rate.

The conclusions listed above, concerning our hypotheses, have been formulated in a cautious way and require further research. More studies are also needed when it comes to another, more general, conclusion, which stems not only from the hypotheses presented in this paper, but, also, from our long-term studies. This conclusion states that the specificity of pro-ecological behaviors of Poles is related to the specificity of the socioeconomic growth of Poland, i.e., the premature stage of its ecological market.

The analysis conducted within this study was aimed at completing the research gap concerning the factors influencing pro-ecological financial decisions in Poland. This problem is connected to both the Pro-Environmental Behavior (PEB) concept and the idea of Socially Responsible Investment (SRI). We may assume that, with the continuing economic growth of the country, which also results in an increasing degradation of the natural environment, more and more public attention will be drawn to pro-ecological questions in Poland. At present, however, contrary to the situation in Western European countries and in North America, the Polish pre-ecological market is still quite undeveloped. This is why our study was mostly based on experience provided by other countries.

The ecological financial market in Poland does not develop at a satisfactory rate when it comes to ecological awareness and socially responsible investment. While this market is still quite immature, Poland is slowly evolving towards becoming a more ecology-concerned country, both on state and local authority levels and on a household level [53]. It is clear that, regardless of how we define its “environmental maturity stage”, Poland still remains at an early stage of implementing pro-ecological behaviors in individuals, companies and state authorities. As a result of the conducted research, we suggest increasing all activities in the field of environmental policy that could increase the participation of society in facilitating sustainable development.

5. Limitations

The analysis was conducted on a representative sample of inhabitants of Poland. Hence, the results and conclusions are limited to Polish society and may not be generalized. However, the results of this study allow for completing a research gap and may be considered as a starting point for further research. Although, in our opinion, the research can be generalized to countries with a similar, low level of ecological maturity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.W., L.D., D.D., M.B., J.P., A.Ż.-K. and D.K.; methodology D.W., M.B. and D.K.; software, D.W. and M.B.; validation, D.W., L.D., D.D., M.B., J.P., A.Ż.-K. and D.K.; formal analysis, D.W., L.D., D.D., M.B., J.P., A.Ż.-K. and D.K.; investigation, D.W., L.D., D.D., M.B., J.P., A.Ż.-K. and D.K.; resources, D.W., L.D., D.D., J.P., and D.K.; data curation, D.W., M.B. and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.W., L.D., D.D., M.B., J.P., A.Ż.-K. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, D.W., L.D., D.D., J.P., A.Ż.-K. and D.K.; visualization, D.W. and M.B.; supervision, D.W., L.D., D.D. and D.K.; project administration, D.W. J.P. and D.K.; funding acquisition, D.W., L.D., J.P. and D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, grant number FUTURE/06/2020 and The APC was funded by Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly avail-able due to privacy considerations.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bliss, S.; Egler, M. Ecological Economics Beyond Markets. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 178, 106806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougle, L.M.; Greenspan, I.; Handy, F. Generation green: Understanding the motivations and mechanisms influencing young adults’ environmental volunteering. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2011, 16, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckman, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and Synthesis of Research on Responsible Environmental Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behaviour? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Karakas, F.; Sarigöllü, E. Exploring pro-environmental behaviors of consumers: An analysis of contextual factors, attitude, and behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hira, T.K.; Loibl, C. Gender Differences in Investment Behavior. In Handbook of Consumer Finance Research; Xiao, J.J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G. Some Determinants of the Socially Responsible Investment Decision: A Cross-Country Study. J. Behav. Finance 2007, 8, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, D.; Pieńkowska-Kamieniecka, S. Gender differences in financial behaviours. Eng. Econ. 2018, 29, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J. Investment with a Conscience: Examining the Impact of Pro-Social Attitudes and Perceived Financial Performance on Socially Responsible Investment Behavior. J. Bus. Ethic 2007, 83, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, B.; Korunka, C.; Hoonakker, P.; Raymo, J.M. Work and Family Characteristics as Predictors of Early Retirement in Married Men and Women. Res. Aging 2010, 32, 467–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Biswas, K.; Moyeen, A. Determinants of Pro-environmental Behaviours—A Cross Country Study of Would-be Managers. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2020, 14, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balundė, A.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. The Relationship Between People’s Environmental Considerations and Pro-environmental Behavior in Lithuania. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N. The effect of gender on students’ sustainability consciousness: A nationwide Swedish study. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 48, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yang, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Does education level affect individuals’ environmentally conscious behavior? Evidence from Mainland China. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2020, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, N.M. Environmental Education and Behavioral Change: An Identity-Based Environmental Education Model. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2015, 10, 695–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, S.J.; Thomas, J.M. Analyzing demand for disposal and recycling services: A systems approach. East. Econ. J. East. Econ. Assoc. 2006, 32, 221–240. [Google Scholar]

- Mundaca, L.; Neij, L.; Worrell, E.; McNeil, M.A. Evaluating Energy Efficiency Policies with Energy-Economy Models. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 305–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, D.G.; Pownall, R.A.J. Going green: Does it depend on education, gender or income? Appl. Econ. 2013, 46, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A. Does education increase pro-environmental behavior? Evidence from Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 116, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, D.A.; Ward, M.B. Energy efficiency and financial literacy. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 90, 181–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, J.E.; Tan, D.T. Does it Really Hurt to be Responsible? J. Bus. Ethic 2013, 122, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duuren, E.; Plantinga, A.; Scholtens, B. ESG Integration and the Investment Management Process: Fundamental Investing Reinvented. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 138, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.; Smeets, P. Social identification and investment decisions. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2015, 117, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa, D.; Dziawgo, L.; Buszko, M. Preferences of individual investors from different generations in Poland in terms of socially responsible investments. In Eurasian Economic Perspectives, Proceedings of the 26th and 27th Eurasia Business and Economics Society Conferences, Prague, Czech Republic, 24–26 October 2018; Bilgin, M.H., Danis, H., Demir, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Zerbib, O.D. The effect of pro-environmental preferences on bond prices: Evidence from green bonds. J. Bank. Finance 2019, 98, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziawgo, L. Greening financial market. Copernic. J. Finance Account. 2014, 3, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Sansone, D.; van Soest, A.; Torricelli, C. Household preferences for socially responsible investments. J. Bank. Finance 2019, 105, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, T.C.; Junkus, J.C. Socially Responsible Investing: An Investor Perspective. J. Bus. Ethic 2012, 112, 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziawgo, D. Households financial behavior: Selected aspects at the time of turbulence. In Business Challenges in the Changing Economic Landscape; Bilgin, M.H., Danis, H., Demir, E., Can, U., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Nauges, C. Greening Household Behaviour and Water. OECD Environ. Work. Pap. 2014, 73, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, N.; Brandt, N. Determinants of households’ investment in energy efficiency and renewables: Evidence from the OECD survey on household environmental behaviour and attitudes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 044015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, M.; Jereb, B.; Obrecht, M. Factors influencing the purchasing decisions of low emission cars: A study of Slovenia. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2014, 30, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooch, M. A sense of place: Ecological identity as a driver for catchment volunteering. Aust. J. Volunt. 2003, 8, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yorkovsky, Y.; Zysberg, L. Personal, Social, Environmental: Future Orientation and Attitudes Mediate the Associations between Locus of Control and Pro-environmental Behavior. Athens J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 8, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Value: The Role of Customer Awareness. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 1045–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasewark, W.R.; Riley, M.E. It’s a Matter of Principle: The Role of Personal Values in Investment Decisions. J. Bus. Ethic 2009, 93, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, M.; Sarriegi, J.M.; Viles, E. Environmental management maturity model for industrial companies. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2017, 28, 632–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, E.; Arimura, T.H.; Nakano, M. A new insight into environmental innovation: Does the maturity of environmental management systems matter? Ecol. Econ. 2013, 94, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Interactions between industrial development and environmental protection dimensions of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Evidence from 40 countries with different income levels. Environ. Socio Econ. Stud. 2020, 8, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, N.; VanHeuvelen, T. Heterogeneity in the Relationship between Country-Level Affluence and Environmental Concern. Soc. Forces 2017, 96, 329–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paço, A.D.; Alves, H.; Shiel, C.; Filho, W.L. A multi-country level analysis of the environmental attitudes and behaviours among young consumers. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2013, 56, 1532–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidescu, A.A.; Apostu, S.-A.; Paul, A. Exploring Citizens’ Actions in Mitigating Climate Change and Moving toward Urban Circular Economy. A Multilevel Approach. Energies 2020, 13, 4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côrtes, P.L.; Fernandes, M.E.D.S.T.; Pamplona, J.M.V.; Dias, A.G. Environmental Behavior: A Comparative Study between Brazilian and Portuguese Students. Ambient. Soc. 2016, 19, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrzałek, W. The Importance of Ecological Awareness in Consumer Behavior. Res. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2017, 501, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabawa, J.; Kozyra, C. Eco-Banking in Relation to Financial Performance of the Sector—The Evidence from Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdys, D. Green bonds as a source of financing pro-environmental actions in Poland. J. Financ. Financ. Law 2020, 1, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Poland country Briefing—The European Environment—State and Outlook 2015. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/soer/2015/countries/poland (accessed on 5 November 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).