Abstract

With increasing concerns regarding environmental sustainability, energy transition has emerged as a vital subtopic in transition studies. Such socio-technical transition requires social learning, which, however, is poorly conceptualized and explained in transition research. This paper overviews transition research on social learning. It attempts to portray how social learning has been studied in the context of energy transition and how research could be advanced. Due to the underdevelopment of the field, this paper employs a narrative review method. The review indicates two clusters of studies, which portray both direct and indirect links concerning the phenomena. The overview reveals that social learning is a force in energy transition and may occur at different levels of analysis, i.e., micro, meso, and macro, as well as different orders of learning. The author proposes to develop the academic research on the topic through quantitative and mixed-methods research as well as contributions and insights from disciplines other than sociology and political science. Some relevant topics for further inquiry can be clustered around: orders of social learning and their antecedents in energy transition; boundary-spanning roles in social learning in the context of energy transition; social learning triggered by stories about energy transition; and other theoretical underpinnings of energy transition research on social learning.

1. Introduction

The energy sector plays a vital role in contemporary societies, since it contributes to their socioeconomic development and well-being. With increasing concerns regarding environmental sustainability, policies directed at the energy sector have moved toward more efficient technologies and clean energy resources that call for energy transition [1,2,3]. For European Union countries, the European Commission indicated the goals for the energy transition up to 2030 and 2050 in the regulations of 2019 [4]. They laid the regulatory foundations for the so-called socio-technical transition of the energy sector in the member states, as energy transition should be understood [5,6,7]. It is a transition “that requires the co-evolution of social, economic, political, and technical factors” [8] as well as social learning [9]. Social learning, that is, an interactive and dynamic process of knowledge creation and acquisition among various societal actors through social interactions [10], is especially emphasized in research on the socio-technical transition process that leads to enhanced system sustainability [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Yet, in the view of Scholz and Mehner, “it remains weakly conceptualized and elaborated in transition research” [3] (p. 323). Moreover, Mierlo and Beers claim that “well-established research fields related to learning are broadly ignored or loosely applied” in transition studies [15] (p. 255). Nevertheless, social learning is an essential factor in the socio-technical transition process since it induces indispensable changes in actors’ norms, values, goals, and operational procedures. These changes govern the decision-making processes and actions necessary to turn ideas into daily practice [11,13].

In the context of the energy sector, the topic of social learning appears to be even less developed. This paper intends to demonstrate this research gap. It critically reviews the available research on social learning for energy transition, and attempts to portray how social learning has been studied in the context of energy transition and how research could be advanced in order to expand the domain of transition studies. The specific questions that the review answers are as follows: (1) Is social learning defined in a reviewed study, and, if so, how? What is the role of social learning? (2) In what context are social learning and energy transition studied in the reviewed research? (3) Does the reviewed study show links between social learning and energy transition, and if so, what are they? and (4) Which questions in the study remain unanswered with regard to social learning in the context of energy transition?

Due to the scant research on the issue that is currently available, this paper applies a narrative review method, which allows the advancement of conclusions from a limited number of various types of studies, including empirical and conceptual work. Such a review should not only summarize works but also develop “original thinking that builds on an integration of the literature reviewed” [16] (p. 186) and is feasible for a single researcher. It ought to propose conclusions on how to further expand the field. Thus, the current review also attempts to address the question of how the links between social learning and energy transition can be approached in future research. It may advance transition studies with regard to energy transition and social learning.

In the next section, the paper first briefly portrays the frames for the studied phenomenon delineated by the domain of transition research. Furthermore, it explains the methodological approach for the selection of studies for the review. It briefly sums up each work and groups them into two clusters. It also attempts to address the aforementioned specific questions and advances conclusions concerning what we know about social learning for energy transition, what we still do not know in that respect, and how the field can be developed in the future. The review expands the existent knowledge of transition studies.

2. Transition Studies

We have been able to observe the rapid growth of transition studies over recent years [17]. The domain is concerned with transitions, i.e., wide-ranging, fundamental, structural changes of various socio-technical systems, such as the energy, transportation, food, and health systems. Hence, the topic of energy transition is discussed in transition studies. The field is interdisciplinary and has been developed by researchers from the fields of sociology, political science, economics, psychology, management, engineering, geography, and philosophy. It tackles the issues of “governance, power and politics, civil society, culture and social movements” [17] (p. 5) in regard to system transitions. The domain has adopted many theoretical backgrounds designed for transition studies, i.e., the multi-level-perspective framework, strategic niche management, transition management and technological innovation systems [18], yet many authors have developed unique theoretical approaches by combining perspectives from different disciplines [17]. Qualitative methods, especially the case study method, have been mainly used to address research questions in transition studies.

Zolfagharian et al. [17] indicate that transition studies have recently been enriched by focusing on other factors influencing transition processes which, although critical, have been overlooked in prior research. Social learning appears to be such a factor [15]. Mierlo and Beers [15] notice that transition studies quite often mention the term social learning, which is not surprising, since social learning shares many similarities with transition studies, namely: the multi-stakeholder approach, the focus on structural change, and the diverse time horizons. Despite this, transition scholars have seldom adopted theories of social learning, differentiated between outcomes and processes of social learning, or investigated certain negative effects, such as learning to resist change. The following review of energy transition studies on social learning leads to similar conclusions.

3. Method

This review provides a narrative, critical synthesis of various types of research around the topic of social learning in the context of energy transition. It attempts to portray how social learning has been studied in the energy transition setting and how research could be advanced. There are four specific questions that the review intends to answer: (1) Is social learning defined in a reviewed study, and if so, how? What is the role of social learning? (2) In what context are social learning and energy transition studied in the reviewed research? (3) Does the reviewed study show links between social learning and energy transition, and if so, what are they? (4) Which questions in the study remain unanswered with regard to social learning in the context of energy transition?

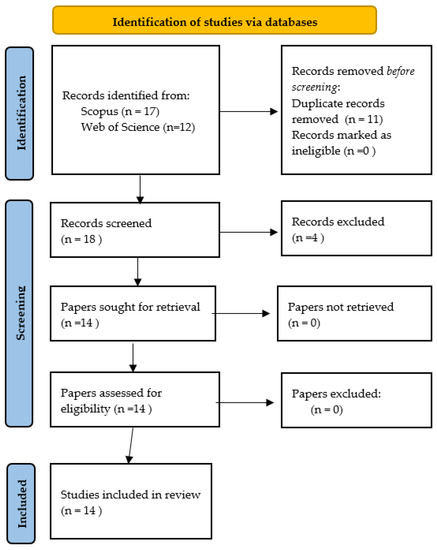

Despite its narrative character, the review protocol was guided by the PRISMA 2020 checklist [19]—see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Two databases were used as search engines, namely Scopus and the Web of Science, since both allow a search strategy based on simultaneous searching for published, peer-reviewed studies according to a set of keywords in the paper’s title, keywords, and abstract. The following keywords were applied: “social learning” AND “energy transition”. The aim behind this search strategy was to find studies that place sufficient emphasis on the links between social learning and energy transition. Thus, any research that did not mention both pairs of words in either the title, abstract or paper keywords was excluded from the analysis as irrelevant in terms of the aim of the paper. Moreover, both databases were searched as they include top-tier journals with a strong impact on various fields of science. Additionally, these databases index and provide references to papers across the sciences collected in other academic search engines, e.g., Whiley, ScienceDirect, or SpringerLink.

In the search strategy, studies were excluded if they were not published as peer-reviewed papers or in a language other than English (as it limits their international readership). The search strategy was not limited to any specific field due to the interdisciplinary nature of transition studies, nor to a time period.

The search provided only 17 unique records after duplicates from both databases had been removed. In the initial screening of the results, four records were eliminated (one paper was written in German, one record was a working paper, one paper provides references to social learning in the main text only, and another was a book chapter). As a result, 14 papers were retrieved and analyzed for eligibility, and subsequently included in the review (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Journals where studies were published.

4. Results

This section discusses the overall characteristics of the reviewed papers and how they approached social learning in the context of energy transition. It also indicates directions for the development of scholarship.

4.1. Basic Characteristics of Studies

The reviewed papers were published from 2017–2021, whereas in 2021, there were five studies released, four in 2017, two in 2020 and 2018, and one in 2019. The authors mainly used the journal Energy Research & Social Science for the dissemination of their research (see Table 1).

After reading the entire text of each paper, nine out of fourteen were classified as studies that directly tackle social learning in the context of energy transition, and the remaining five as those where the topic is not treated as a primary thread (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Studies on social learning in the context of energy transition.

The authors approached the topic through mainly qualitative studies; one research paper was a mixed-methods study, three papers were conceptual and one was a theoretical review. In terms of the methods used for data collection, three papers reported data from interviews, three from case studies (two from a single case study and one from multiple case studies), and in two papers, the authors presented the results of action research and two network analyses; moreover, other studies used observation and experiments. Two papers analyzed and compared data from more than one country [21,30].

All the studies conducted refer to various disciplines within social science; however, two of them are the most influential, i.e., sociology and political science. The authors locate their studies in different areas, e.g., public management studies [20,28], landscape studies [10], innovation studies [21,22,25], or adult education research [23]. Transition studies are represented in most of the papers [22,24,27,29,30].

The theoretical background is not always revealed in the research, yet transition theory, especially socio-technical transition and the multi-level perspective [22,25,30], has substantiated most studies [22,24,27,29,30] and appears as a cutting-edge theory in energy transition studies. This is not surprising because transition theory focuses “on determining social movements and social innovations [and its] effectiveness is measured by legitimacy and social learning” [9] (p. 776).

The context of the study varied significantly and referred to the macro (e.g., the socio-cultural, technological, economic or political factors [20,30]), meso (e.g., the socio-technical regimes [27], and micro-contexts (e.g., niches [22,24]), practices and interlinked actors [10,21,22,26]).

4.2. Social Learning: Concept and Role in the Study

First and foremost, it needs to be stressed that the confined number of studies defines social learning [14,20,21,24] and one paper refers to its single order—transformative learning [25]. The authors of three papers [14,20,21] refer to a definition of social learning proposed by Reed et al. [32], who perceive it as learning through social interaction that requires reflection and leads to changes in understanding, attitudes, beliefs, and values. Yet studies that do not define social learning portray it as learning in social interactions as well [10,14]. Such learning has an impact on the wider social context and involves sharing ideas, knowledge, and experiences among individuals. Proka et al. [24] also highlight knowledge exchange in their definition of social learning.

In addition, Pellicer et al. describe social learning as learning in a social action process and indicate its two orders (i.e., instrumental—learning how to do something, and transformative learning—“changes in mental frames and assumptions”) [25] (p. 102). Likewise, other studies distinguish distinct kinds (or levels, loops, or orders) of social learning. Mah et al. [20] analyze three orders of learning, i.e., instrumental learning (acquiring new knowledge or skills), communicative learning (understanding and reinterpreting knowledge through deliberative processes), and transformative learning (reflecting on the underlying assumptions that lead to a change in perceived values). In their study, they proved that deliberative participation processes supported all three orders of learning and identified factors that enabled progress to higher orders of learning (see Table 2).

Transformative learning (here the second order of learning) is separately investigated in research by Pellicer et al. [25], who emphasize its reflective character. Their study shows that both micropolitical and macropolitical factors influenced the emergence of first- and second-order learning, which then modeled three different sustainability strategies proposed by the grassroots initiatives studied. References to first and second-order learning can also be found in a study by Sillak et al. [28]. In view of this research, first-order learning allows an understanding of how a goal can be achieved, while second-order learning is more reflective and leads to a determination of which goals are worth achieving. The authors formulate an assessment framework for co-creation in strategic planning for energy transitions that involves social learning as an activity in the co-creation process.

Transformative learning, according to Reed et al., is associated with double-loop learning that assumes “reflecting on the assumptions which underlie our actions” [32] (p. 4). In their conceptual study, Milchram et al. [14] proposed a dynamic framework for institutional change that is instrumental in energy transition, which includes double- and triple-loop (changes in the existing exogenous variables) learning. In their framework, controversies concerning values can be expressed in social interaction and stimulate double- and triple-loop social learning, both of which may be decisive in transition processes driven by institutional change.

With regard to the role of social learning, the reviewed research demonstrates that social learning is a key element in change or transition processes [9,14,21,24,25,26,28,29,30] as well as being vital from a participatory perspective [10,14,20]. It can also be identified as one of the orientations in adult learning, which is particularly needed in energy transition [23].

4.3. Social Learning and Energy Transition—Direct and Indirect Links

As a starting point, one remark ought to be made. The research regarding social learning for energy transition is mainly based on rather scant qualitative studies and a few conceptual studies; as such, implying antecedent variables and outcomes of social learning is inappropriate. An absence of quantitative studies is noticeable. Nevertheless, the reviewed research allows for an understanding of how the authors relate both phenomena.

4.3.1. Direct Links

The cluster of studies on the direct links between social learning and energy transition includes nine works, namely six empirical papers, two conceptual papers, and one theoretical paper.

Mah et al. [20] link social learning and energy transition through citizens’ participation in deliberative processes. The study suggests that all the orders of learning observed in deliberative processes can create forces for energy transition.

Boyle et al. [10] and Proka et al. [24] connect social learning with energy transition through action research. Social learning can be stimulated by action research, leading to more sustainable and just transition [10] or strategizing incumbent regimes [24]. Regarding the latter, a study by Proka et al. [24] did not confirm the links.

Matschoss et al. [21] hold that energy transition can be achieved through change initiatives concerning practices and related values and studied whether more extensive social learning in community living labs is conducive to engagement in the change process. In another study, Matschoss and Repo [22] identified patchworks of niches directed toward energy transition in Finland and claim that social learning can be developed through interconnections and experimentation therein.

Pellicer et al. [25] studied grassroots initiatives and assumed that energy transition requires various sustainability strategies, which, in turn, are shaped by first- and second-order learning driven by micropolitical (concerning a niche) and macropolitical factors (concerning landscape and niche-regime interactions).

Skjolsvold et al. [26] analyzed how “smart” energy feedback technologies can be helpful in the quest for energy transition in households. They identified four processes, which they labeled re-arrangements (concerning knowledge, materials, social relations and routines), triggered by feedback technology. These processes involve learning which can support transformative actions.

Picci et al. [23], in their conceptual work, analyze training civil servants from the adult learning perspective and analyze different orientations in adult education. They posit that a social learning environment presents synergistic links with constructivist research through a design approach that can enhance energy transition through capacity building. Another conceptual study by Milchram et al. [14] links social learning and energy transition through the Institutional Analysis and Development framework extended with feedback loops of social learning. They contend that value controversies can initiate social learning processes that may eventually bring about structural change.

Finally, Edomah et al. [9] focus on the theoretical underpinnings of changes in energy supply infrastructure, which can be perceived as a component of energy transition. The relationship between social learning and energy transition can be determined from the socio-technical transition perspective, which sees social learning as an effectiveness factor in social movements and social innovations.

4.3.2. Indirect Links

This cluster encompasses four empirical works and one conceptual paper.

Groves et al. [27] analyze how the credibility of energy system visions was achieved and posit that social learning is part of the process of the development of visions for demonstrators. Social learning concerns local values, a factor frequently missing in systemic visions, and critical reflections about key assumptions underlying dominant system-level visions.

The idea of energy transition as a non-uniform process influenced by geography and history as well as operating at many levels is underlined in a study by Darby [29], who portrayed ‘learning stories’ in the everyday energy transition of households in Scotland.

Social learning as a way of using knowledge from existing cases on energy transition to inform future cases is suggested by Akizu et al. [30]. After comparing different paths of energy transition in the South and the North, they recommend a democratized, universal energy model.

The last empirical study in this cluster, conducted by Asayama and Ishii [31], is based on discourse analysis and relates to news media storylines concerning carbon capture and storage. They hold that energy transition in part of a chosen technology can be influenced by news media stories. Therefore, they posit that media should enhance social learning about a given project.

The only conceptual study in this cluster, by Sillak et al. [28], proposes a framework to assess co-creation in strategic planning for energy transition. Social learning is included in this framework as one of the activities that foster transformative power in co-creation.

4.4. Possible Directions for the Development of Inquiry

This review allows the researcher to form an initial conclusion, namely, that energy transition research on social learning shares a similar methodological concern with the sustainability transition subfield and transition studies in general, which indicates directions for the development of this scholarship. In all these fields of study, qualitative research designs dominate over quantitative and mixed-method approaches [7,17]. The studies “struggle to connect with disciplines leaning more on quantitative methods (…) and to generate generic insights beyond single cases” [7] (p. 172). Hence, quantitative and mixed-methods research may offer promising prospects for energy transition research on social learning, e.g., a quantitative analysis of social networks and social learning directed toward energy transition or how the diversity of various stakeholders of energy systems facilitates different orders of learning. Nevertheless, by the very nature of energy transition and social learning, quantitative approaches may not fit all types of posited research questions.

Second, although the scholarship is interdisciplinary, to date it has been dominated by two disciplines, sociology and political science. Contributions and insights from other disciplines, such as psychology or management, could also be beneficial. Examples may include the psychological study of the social learning of pro-environmental behaviors and their role in energy transition, green servant leaders as role models in energy transition, the organizational approach to studying superficial social learning in niches, the role of unlearning in social learning, or the occurrence of social learning to resist changes, etc.

Third, the overview of the research enabled the identification of potential avenues for future research inspired by each included study (Table 2, in the column “potential future studies”) that can be clustered around a few streams:

- Comparative cross-country or cross-sectoral energy transition research on social learning;

- Orders of social learning:

- and their antecedents in energy transition;

- in niches, regimes, and landscapes;

- in social movements for energy transition;

- in social innovations for energy transition;

- in the domestication of new technologies for energy transition;

- Boundary-spanning roles of various actors in social learning in the context of energy transition;

- Social learning triggered by stories about energy transition.

- Other theoretical underpinnings of energy transition research on social learning, e.g., the study of how social interactions affect the behavior of energy users inspired by Bandura’s social learning theory [33], or research on the conditions facilitating social unlearning in energy transition projects underpinned by organizational learning theory.

4.5. Summary of Narrative Review

To recap, based on the studies reviewed, social learning is a crucial force in energy transition that requires the structural change of energy systems, and social learning can promote it. It may occur at different levels of analysis, i.e., micro, meso and macro, and is embedded in social interactions, which may expose controversies concerning values. Social learning facilitates critical reflections about key underlying visions of energy systems. It can support sustainable and just energy transition as it shapes sustainability strategies. Such learning may enable transformative actions triggered by feedback technology. In addition, social learning environments enhance energy transition through capacity building. Energy users may learn from others, while policymakers learn from existing cases about energy transition. Moreover, media can be involved in social learning to promote energy transition. Finally, social learning fosters the effectiveness of social movements and social initiatives engaged in the transition process.

To date, social learning has been observed in participation processes, action research, change initiatives, and patchworks of niches. It is part of everyday transition. In addition, it is recommended as a transmission mechanism among various social actors concerning knowledge about energy transition strategies, visions, and values. However, future studies should further develop energy transition research on social learning since, in the view of the author, without a deep understanding of the role and antecedents of social learning in different contexts, turning transition ideas into daily practice may be complicated. The current research has insufficiently differentiated between the processes and outcomes of social learning, its conducive and hampering factors, the durability of changes, or learning to resist changes. Moreover, an imbalance between qualitative and quantitative research is visible. As suggested in another review study on transition research: “Extending the methodological toolbox beyond primarily qualitative process theories might lead to a better understanding of possible intervention strategies—and as such, greater policy impact” [17] (p. 12).

5. Conclusions

The field of transition studies is growing and energy transitions appear to be its main focal point [7]. Nonetheless, energy transition research on social learning is still sparse, as this overview has demonstrated, and further elaboration of previous research is necessary.

Concerning contributions, the review elaborates upon energy transition studies by showing how links between social learning and energy transition have been analyzed by scholars, which relationships have been identified in prior studies, which theoretical backgrounds have substantiated the studies, and what is still lacking in energy transition research on social learning. This approach allowed suggestions to be made pertaining to how the field can be advanced, i.e., through methodological and theoretical diversity, contributions and insights from more disciplines and research on some possible areas requiring more thorough investigation, as indicated above. More efforts have to be made to better understand social learning in energy transition. The review aims to inspire future empirical research, in which crossovers between transition studies and learning traditions are necessary.

The review informs practice and policymakers with respect to the critical role of social learning for energy transition, yet it also claims that the research field is underdeveloped. Concerning practical and political implications, the review indicates that diversity of stakeholders, through divergent perspectives and value controversies, can be conducive to social learning for energy transition and lead to higher orders of learning. However, political and contextual factors may constrain social learning in deliberative processes and should be addressed by appropriate policies. Furthermore, policymakers ought to enhance interactions and dialogue among diverse stakeholders, support their access to multiple information sources about energy transition, and involve various actors in discussions about visions of energy systems. Policymakers may enable the functioning of social movements and initiatives engaged in the transition because these grassroots forces create the conditions for social learning. Both practitioners and politicians should look for actors who can potentially play the role of boundary spanners in energy transition. Moreover, media should also be involved in social learning to promote the necessary changes.

Nevertheless, this review is also limited by the predefined search strategy, which excluded certain search engines, and consequently publications, from the analysis. A narrative review method chosen to analyze selected papers is also, by its very nature, subjective. The values and attitudes of the author could have affected the evaluation. Furthermore, narrative reviews are criticized for lacking synthesis and rigor [34], yet the author addressed this issue by applying the PRISMA checklist to the literature analysis. Nonetheless, the review should be subject to further advancements by other scholars.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Pokharel, T.; Rijal, H. Energy Transition toward Cleaner Energy Resources in Nepal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, L.; Sauri, D. Socio-technical transitions in water scarcity contexts: Public acceptance of greywater reuse technologies in the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 55, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, G.; Methner, N. A social learning and transition perspective on a climate change project in South Africa. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 34, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clean Energy for all Europeans 2019. European Commission: Luxemburg, 2019. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/pl/publication-detail/-/publication/b4e46873-7528-11e9-9f05-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Pregger, T.; Naegler, T.; Weimer-Jehle, W.; Prehofer, S.; Hauser, W. Moving towards socio-technical scenarios of the German energy transition—Lessons learned from integrated energy scenario building. Clim. Chang. 2020, 162, 1743–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, J.S.; Nyborg, S.; Hansen, M.; Schwanitz, V.J.; Wierling, A.; Zeiss, J.; Delvaux, S.; Saenz, V.; Polo-Alvarez, L.; Candelise, C.; et al. Collective Action and Social Innovation in the Energy Sector: A Mobilization Model Perspective. Energies 2020, 13, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hansmeier, H.; Schiller, K.; Rogge, K.S. Towards methodological diversity in sustainability transitions research? Comparing recent developments (2016–2019) with the past (before 2016). Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 38, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S. The paradox of the energy revolution in China: A socio-technical transition perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 137, 110469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edomah, N.; Foulds, C.; Jones, A. Influences on energy supply infrastructure: A comparison of different theoretical perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boyle, E.; Gallachóir, B.Ó.; Mullally, G. Participatory network mapping of an emergent social network for a regional transition to a low-carbon and just society on the Dingle Peninsula. Local Environ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovardas, T. Social Sustainability as Social Learning: Insights from Multi-Stakeholder Environmental Governance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Virkamäki, V.; Kivimaa, P.; Hildén, M.; Wadud, Z. Socio-technical transition governance and public opinion: The case of passenger transport in Finland. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 46, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, J.; Brown, R. Governance experimentation and factors of success in socio-technical transitions in the urban water sector. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2012, 79, 1340–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milchram, C.; Märker, C.; Schlör, H.; Künneke, R.; Van De Kaa, G. Understanding the role of values in institutional change: The case of the energy transition. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2019, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Mierlo, B.; Beers, P.J. Understanding and governing learning in sustainability transitions: A review. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 34, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D. What makes for a good review article in organizational psychology? Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 2, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zolfagharian, M.; Walrave, B.; Raven, R.; Romme, A.G.L. Studying transitions: Past, present, and future. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, J. Transition Studies: Basic Ideas and Analytical Approaches. In Handbook on Sustainability Transition and Sustainable Peace; Brauch, H., Oswald, S.Ú., Grin, J., Scheffran, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mah, D.N.; Siu, A.; Li, K.; Sone, Y.; Lam, V.W.Y. Evaluating deliberative participation from a social learning perspective: A case study of the 2012 National Energy Deliberative Polling in post-Fukushima Japan. Environ. Policy. Gov. 2021, 31, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschoss, K.; Fahy, F.; Rau, H.; Backhaus, J.; Goggins, G.; Grealis, E.; Heiskanen, E.; Kajoskoski, T.; Laakso, S.; Apajalahti, E.-L.; et al. Challenging practices: Experiences from community and individual living lab approaches. Sustain. Sci. Pr. Policy 2021, 17, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschoss, K.; Repo, P. Forward-looking network analysis of ongoing sustainability transitions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 161, 120288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchi, P.; Qudes, D.; Stremke, S. Linking research through design and adult learning programs for urban agendas: A perspective essay. Riv. Res. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 18, 198–213. [Google Scholar]

- Proka, A.; Loorbach, D.; Hisschemöller, M. Leading from the Niche: Insights from a Strategic Dialogue of Renewable Energy Cooperatives in The Netherlands. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pellicer-Sifres, V.; Belda-Miquel, S.; Cuesta-Fernandez, I.; Boni, A. Learning, transformative action, and grassroots innovation: Insights from the Spanish energy cooperative Som Energia. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 42, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjølsvold, T.M.; Jørgensen, S.; Ryghaug, M. Users, design and the role of feedback technologies in the Norwegian energy transition: An empirical study and some radical challenges. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, C.; Henwood, K.; Pidgeon, N.; Cherry, C.; Roberts, E.; Shirani, F.; Thomas, G. The future is flexible? Exploring expert visions of energy system decarbonisation. Futures 2021, 130, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillak, S.; Borch, K.; Sperling, K. Assessing co-creation in strategic planning for urban energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 74, 101952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, S. Coal fires, steel houses and the man in the moon: Local experiences of energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akizu, O.; Urkidi, L.; Bueno, G.; Lago, R.; Barcena, I.; Mantxo, M.; Basurko, I.; Lopez-Guede, J.M. Tracing the emerging energy transitions in the Global North and the Global South. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 18045–18063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asayama, S.; Ishii, A. Selling stories of techno-optimism? The role of narratives on discursive construction of carbon capture and storage in the Japanese media. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C.; et al. What is social learning? Response to Pahl-Wostl. 2006. “The importance of social learning in restoring the multifunctionality of rivers and floodplains”. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, r1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; General Learning Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.A. Improving the peer review of narrative literature reviews. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2016, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).