Abstract

This paper investigates the suitability of the community cooperatives (CC) model for the implementation of renewable energy communities (REC), as prescribed by art. 22 of EU Directive 2018/2001, and temporarily transposed into the Italian law by art. 42-bis of the Law Decree n. 162/2019. The hypothesis explored analyses the potential synergies between RECs and CC, based on their similarities. In particular, the article takes into consideration: the actors involved in both the RECs and the CCs; the geographical scope in which they develop, and the purposes that these two legal forms intended to achieve. Through a literature review and the analysis of EU, national and regional legislations, the paper aims at (1) clarifying the main features of RECs and the CCs in Italy; (2) exploring the main differences between CCs and the other legal forms of cooperative (e.g., mutual cooperative, cooperative benefit, etc.) and assessing the extent to which CCs are more suitable to implement renewable energy communities. As a result of the literature and regulatory review, several similarities between CCs and RECs can be detected, particularly, in reference to the strategic valorization of the cooperation between citizens and the local public entities. These similarities allow the authors to provisionally conclude that, in Italy, CCs may be adopted as a tool to implement RECs.

1. Introduction

The relevance of the engagement of citizens as a crucial requirement for the energy transition to be effectively implemented has been recently recognized by the European Commission that posed specific attention to the topic within the Clean Energy for all the Europeans Package. In the Clean Energy Package, approved in 2019, the EU has in fact underlined the importance of initiatives, such as energy communities and joint self-consumptions, that actively involve citizens and provided a regulatory framework for these initiatives to be formally recognized by the EU countries’ national legal system. In particular, energy communities are considered as a feasible solution to help to increase public acceptance on renewable energy projects and to attract investments and two directives, out of the eight that compose the Clean Energy Package, contain regulatory provisions aimed at ruling energy communities: the Directive on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources (2018/2001) and the Directive on common rules for the internal market for electricity (2019/944). These directives promote the establishment of two different types of energy community, respectively, the REC (renewable energy community) and the CEC (citizen energy community) [1,2,3,4]. Both the RECs and CECs are a legal entity based on open and voluntary participation, effectively controlled by shareholders or members, and whose purpose is to realize environmental, economic and social benefits rather that financial profits. Moreover, both type of energy communities may contribute to the improvement of environmental performance and reduction of polluting emissions; the management of the infrastructure, of the national electric grid costs, of the negative externalities; the reduction of the consumption of fossil fuel; the improvement of the quality and reliability of energy supply; and the reduction of energy poverty for some groups of the population.

The shareholders and members could be natural persons, small–medium enterprises, as well as local authorities, including municipalities.

RECs and CECs can produce, sell, store and consume energy and, in order to facilitate their activity, the EU Member States are required to remove all barriers for energy communities to access the market as well as to avoid any discrimination. The two major differences between the REC and CEC are that, in the first one, the community produces, sells and consumes only energy from renewable sources whereas, in the second one, it could be any type of energy. The second difference concerns the importance of the physical territory; in fact, for REC, the Directive demands that shareholders or members live near the place where the energy is produced and, on the contrary, for the CEC there is no such requirement [5].

In addition, both the Directives do not set a specific legal form that the two types of cooperatives must have. In light of the circumstance that each Member State is free to adopt a different discipline to establish which legal form the energy communities may adopt, the article aims to investigate the feasibility of implementing RECs through the adoption of community cooperative (CC) form. CC is a specific type of cooperative that has been emerging in the Italian socio-legal context and which, more than other forms of legally recognized grassroots initiatives, is characterized by a very strong connection with the territory where the activities are located. The connection with the territory is detectable both in terms of requirements for the cooperative to be established and in terms of the main objective, that is, to produce local social and economic benefits [6]. Through the strengthening of local communities, CCs might also generate positive externalities for the entire community, including non-members, thanks to the improvement of social innovation processes that might trigger the involvement of citizens and stakeholders in the decision-making process, thus supporting local development trajectories [7].

Italy represents a unique case study for addressing this aim for two main reasons. Firstly, because of the Italian long lasting tradition in energy communities development (a heritage of the historic hydroelectric cooperatives established at the beginning of the XIX century in the North East of the country) [8] and because of the increasing flourishing of social initiatives based on cooperation among citizens [9,10]. Secondly, because CC is a specific legal form that to date is only in the Italian legal system, and it would be challenging to find correspondences in other EU countries, a task that would have required a dedicated research comparative law that is far beyond the scope of the present publication.

Within these constraints, it is then worth clarifying that the article is not intended to give a comprehensive overview about the different options that might be adopted for implementing RECs, but to provide a specific insight of how RECs could be implemented within the Italian social and legal context through the adoption of the CC legal form.

More in details, the article aims to answer to the following questions:

- -

- What is a CC according to the legal point of view in Italy?

- -

- Which are the main differences between the other legal forms of cooperative (such as, e.g., mutual cooperative, non-mutual cooperatives, cooperative benefit, consortium, public-private partnership and cooperative agreement, non-profit organizations) and a CC?

- -

- Why could CCs be a useful tool to implement RECs?

- -

- To what extent could the involvement of locals affect the development of such initiatives?

To address these topics, the authors have carried out a twofold desk research aimed at describing the Italian regulatory framework related to energy communities exploitation and at identifying the raising, the main features and the social innovative potential of the CC form.

In order to address these questions, the authors carried out an analysis of the regulatory provisions relevant for RECs and CCs implementation with attention paid to highlight the commonalities that might feed synergies between the two juridical entities. Italian laws concerning CCs [11] and the Italian temporary transposition law of the EU Directive 2018/2001 have primarily been considered. As for the latter, the authors have analyzed both the European and Italian laws, whereas both the national and regional laws were investigated to properly define what a CC is. Furthermore, the action of the Regulatory Authority for Energy, Networks and Environment (ARERA), an Italian independent authority, whose task is to promote the development of competitive markets in the electricity and natural gas chains, was considered, mainly through the tariff regulation, access to networks, market functioning and consumers protection [12].

This review has been complemented by the description of the main features of CCs as they have been emerging in practice, that is to say that a specific effort has been made to go beyond the legal provisions and to pay attention to the practical experiences of CCs in Italy and to their potential in terms of social innovation processes. As CCs are still a marginal phenomenon in the densely populated landscape of the cooperative movement, they are not yet adequately represented in the academic literature. Therefore, to address the spontaneous establishment of the model in Italy, the paper considered mainly grey literature (e.g., working papers, government documents, reports of non-governmental organizations and academic centers) concerning CC initiative and the development of RECs in Italy. In particular, the result of this inquiry has been used to strengthen the implementation of CCs in Italy in Section 4 as well as the synergies between RECs and CCs in Section 5.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, an overview of the transposition process of EU Directive 2018/2001 in three EU countries (Germany, France and Spain) is provided in order to provide a term of comparison for the Italian transposition process described in details in Section 3. In Section 4, the focus moves to the discipline of CC according to the Italian legal system with attention paid to their actual (although still residual) establishment in the Italian cooperative landscape. Then, in Section 5 the main results of the previous analysis are reported to address the similarities and the potential synergies between RECs and CCs. In the conclusions, Section 6, provisional answers to the research questions are provided and a few remarks about potential research development are proposed.

2. An Overview of the Legislative Discipline on Renewable Energy Communities in Europe: The Cases of France, Germany and Spain

In order to give a term of comparison regarding the level of development of the renewable energy communities in Italy, in this section a brief analysis of the current state of development of REC in Germany, France and Spain is provided (The three countries have been selected as a benchmark given their similarity with Italy in terms of dimension and socio-economic structure).

In Germany, the active participation of citizens within the energy field has a strong tradition, as it dates back to the 20th century [13]. In particular, thanks to the adoption of the Renewable Energy Sources Act (Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz—EEG) on 1 April 2000, there has been a re-emergence of the organizational form of the cooperatives in the energy sector, and its peak was reached in 2011 [14]. In addition to the EEG, the energy market liberalization and the decision to abandon nuclear electricity production have contributed to the development of energy self-production initiatives. In particular, this type of production resulted in the opening of the market to a wider range of subjects, stimulation of the competition, as well as in the birth of bottom-up projects [15]. The EEG, which is a series of laws, was originally adopted to encourage the generation of renewable energies through the adoption of the fed-in-tariff. Since the year 2000, it has been revised several times, and the last version came into force on 1 January 2021. However, it was in 2017 that an amendment of the EEG established the gradual phase-out of the fed-in-tariff, and at the same time, it introduced the so called “citizens energy companies” (Bürgerenergiegesellschaften). The “citizens energy companies”, as ruled by the 2017 EEG version, have some common features with the renewable energy communities introduced by the Directive 2018/2001, but do not respect all the requirement posed by the EU Directive itself. The aim of the “citizens energy companies” is to overcome small-sized plants that are not cost-efficient enough, by enforcing the connection among different plants through the distribution of economic incentives [16]. Moreover, Germans are favorable towards such kind of collective initiatives as they tend to consider the participation to renewable energy projects a “civic engagement” [17]; trust has been noted to be one of the most important element for the success of projects involving renewable energies production and distribution [18]. The legislative framework concerning REC has been partially modified by the Federal law n. 574/2021, approved by the Bundesrat and published on 30th August 2021, which has transposed the Directive 2018/2001.

The second most populated country in EU, France, in 2015 adopted the Energy Transition Law for Green Growth (LTECV), that for the first time introduced specific measures, the so-called “participatory bonuses”, to promote the development and participation of local citizens in renewable energy projects. This law had the merit of making it easier to create citizens’ energy production projects that could be financed by both the local citizens and municipalities. Afterwards, RECs are explicitly mentioned by article 40 of the Law n. 2019-1147 about the energy and climate, which has transposed the EU Directive 2018/2001. In particular, the law amended the Code of the Energy by introducing the REC as disciplined by the EU legislator. Indeed, they are described as autonomous legal entities characterized by: the open and voluntary participation; the effective control by the shareholders that have to live nearby the renewable energy plant; the shareholders could be natural persons as well as municipalities, small-medium enterprises and local authorities; the final goal of the community is to produce environmental, social and economic benefits rather than just financial profits. The RECs can produce, stock and sell energy as well as exchange within the community the energy produced by the units owned by the community itself. In addition, the law established that the community has to have free access to the energy market without any discrimination. In 2021, with the decree n. 236/2021, 3rd March 2021 the French legislator has added to REC discipline two requirements imposed by the EU legislation: for private companies that participate to REC, the involvement in the community cannot be their principal commercial or professional activity; the community members must preserve their quality of end-consumers and especially their rights and obligations. When analyzing the energy sector in France, it is also important to consider that, unlike Germany, the French electricity mix is characterized by the production of nuclear energy which, combined with the hydroelectricity, turns out to have a very low carbon intensity.

Within the described context, the role of REC in France has been defined as “important for its local contribution to social and economic solidarity” [19]. Moreover, RECs are not merely seen as a mean to save/earn money, but also as a way to engage people in energy transition. On this regard, it is essential that citizens consider RECs as an aid to reduce energy poverty and that they understand how such projects could enhance their chance to participate within the decision making processes relating to the energy sector [20].

In 2020 in France, have been registered 256 RECs mainly located in Occitanie, Auvergne-Rhone-Alpes, Britany and Pays de La Loire and the majority of them produce solar energy trough the installation of rooftop photovoltaic. Among these RECs, about 143 are already active, whereas 81 are currently under construction. Overall, RECs produce approximately 512.5 MW and 1047.9 GWh of the electricity that is supplied per year in France. Presently, RECs involve 21,350 citizens who have invested 34 million euros [21].

The third country analyzed is Spain. Concerning the development of RECs in Spain, it is possible to identify two periods of growing of such initiatives. The first one goes from 1997 until 2012, and the second, which is still going on, starts from 2012 [22]. The year 1997 is considered to be significant because it is the beginning of the liberalization process of the electricity sector in Spain; this openness is mainly due to the Spanish participation in the EU Communities. The second turning point is the year 2012 because of the overlap of the economic crisis and the surge in the installation of capacity of gas combined cycle (GCC), which resulted in an oversupply of the energy system. Within this context, it has to be considered that Spain’s electricity sector is characterized by a lack of transparency [23] that allowed the “Asociación Española de la Industria Eléctrica” (the association of the five traditional power utilities) [24] to carry out a defamatory campaign against the producers of renewable energies that were accused to be responsible for the high prices of electricity [22]. As a consequence, the Government, applied taxes on the renewable energy sector, limiting its development through the Royal Decree 900/2015. The situation changed with the issue of the Royal Decree-Law 15/2018 (RD-L15/2018) and the Royal Decree-Law 244/2019 (RD 244/2019), which eliminated the taxes on renewable energies and introduced a legal framework for collective forms of self-consumption. In particular, the RD 244/2019 considers “neighbor communities” the collective self-consumers who live within a maximum of 500 m from an installation that has a limitation of 100 kW of installed capacity [25]. Moreover, the RD 244/2019 introduced easier administrative procedures to receive compensation for the energy surplus fed into the public grid, and it allows the installation of storage elements and enables sharing the energy surplus with nearby consumers [26]. Thereafter, the Spanish government approved the Royal Decree-Law 23/2020, which amended the Electricity Sector Law providing a copy and paste definition of the RECs from the EU Directive 2018/2001. Nevertheless, the legal framework does not specify any further details to effectively support the development of energy communities [27].

3. The Regulatory and Legal Context of RECs in Italy

After the adoption of the EU Directive 2018/2001, academics and policy makers are investigating which are the best legal forms to implement and develop RECs. Under EU legislation, RECs are defined as “a legal entity: (a) which, in accordance with the applicable national law, is based on open and voluntary participation, is autonomous, and is effectively controlled by shareholders or members that are located in the proximity of the renewable energy projects that are owned and developed by that legal entity; (b) the shareholders or members of which are natural persons, small-medium enterprises or local authorities, including municipalities; (c) the primary purpose of which is to provide environmental, economic or social community benefits for its shareholders or members or for the local areas where it operates, rather than financial profits” [28]. The Italian Government has not adopted the Ministry decree aimed at implementing the Directive 2018/2001 yet [29]. In the meantime, the parliament has adopted a provisional discipline, the Law Decree. n. 162 at article 42-bis, [30] to regulate RECs [31]. This law allows the creation of small-scale collective self-production and consumption plants of renewable energy below 200 kW. The plant is used by customers linked to the same low voltage distribution sub-grid. This specific requirement makes it necessary for the members of the community to live nearby where the energy in produced; such importance given to the territoriality is particularly significant in terms of the involvement of the civil society within the realization and management of the community itself.

The same law defines the methods and conditions for activating collective self-production and consumption from renewable sources and to create RECs [4]. In addition, the law delegated the Italian authority responsible for the regulation of energy (ARERA) to adopt the technical measures necessary to ensure the application of the law itself. In particular, ARERA, has established that the REC is the holder of the plant, whereas the energy supplier is the producer of the energy [32]. In this context, the holder has the full availability of the plant and delegates the producer to be the “referent”. The “referent”, who acts as coordinator, is the one who interfaces with the GSE (Italian society responsible for the management of energy services) for the communications and the necessary formalities to benefit from economic incentives. On the other hand, the producer is the subject responsible for the exercise of the electricity plant, and he is not part of the community.

The consumers are the shareholders of the community, and they can be both public and private subjects, local and regional authorities—including municipalities —small–medium enterprises, collective and individual subject [33]; in addition, the members must not have as their principal commercial or industrial activity the participation to the community [34].

Concerning the role of participants, one of the most important aspect is that consumers remain end-consumers with all the guarantees and rights related to this status, such as, for example, the chance to choose their energy supplier as well as the possibility to leave the REC anytime. Besides, considering the actual legal framework of renewable energy communities [35], ARERA emphasizes that the above-mentioned art. 42-bis allows the implementation of a “virtual regulatory model”. This model is an alternative to the “physical regulatory model”, which is characterized by just one exchange point with the electricity grid so that the energy produced stays in the building and the community uses its own (private) grid to exchange electricity [36]. The “virtual regulatory model”, on the other side, allows each end-user to be connected to the public electricity grid, remaining free to decide to choose his energy supplier, to leave the smart system and the community at any time and to exercise his rights as a consumer [37]. In addition, the “virtual regulatory model” enables to realize new self-consumption systems without having to build new grids because, within this model, you can use the public grid [38].

Moreover, the “virtual regulatory model” would guarantee the following features:

- -

- To continue to apply the existing regulation ensuring to all concerned subjects the respect of all the rights currently protected;

- -

- The restitution from the GSE of the amounts related to the self-consumed or collective consumption energy;

- -

- To supply the economic incentive from GSE, as defined by the Ministry of Economic Development.

In this regard, the “virtual regulatory model” enables us to extend the benefits deriving from the use of locally produced energy without requiring the implementation of other technical solutions. Furthermore, the “virtual regulatory model” allows participants to change their energy supply choices without having to request new authorizations to their previous energy supplier or to realize new grid connection. In fact, the described “virtual model” is flexible, sustainable over time and easily adaptable to any future needs [39].

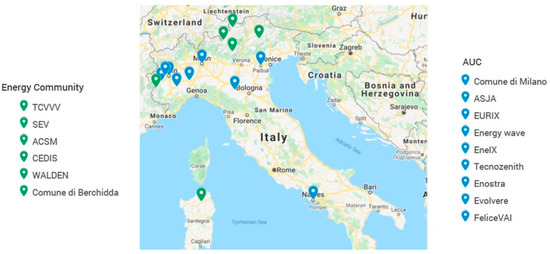

Presently, only few Italian regions (Figure 1) (five out of twenty) have adopted a specific discipline on the subject; the following regions enacted a dedicated regional law: Piemonte, Puglia, Liguria, Calabria and Campania.

Figure 1.

The pilot projects with which RSE is collaborating: Energy communities in green and collective self-consumption in blue—Gli schemi di Autoconsumo Collettivo e le Comunità dell’Energia [36].

The report of Legambiente lists 12 energy communities located in Italy, illustrating the development path (some of them are not yet in activity, but the project is completed) of each one and providing their main features and characteristics. The twelve projects are equally shared on the national territory between the north, the south and the islands, and they are located on ten different regions. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that these energy communities do not meet all the requirements of neither by the Directive 2018/2001 nor by the national law. These communities, which are multiutilities, are mostly based on the cooperation between public and private subjects who own the plant and are responsible for the production and distribution of the energy.

4. The Regulatory and Legal Context of CCs in Italy

A cooperative, which might be defined as an “autonomous association of people aspiring to achieve their objectives through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise” [40], is considered to be better than profit-maximizing firms for several reasons [41] including, for example:

- -

- In coping with economic crises;

- -

- In promoting local business and economic activities;

- -

- In encouraging social inclusion;

- -

- In guaranteeing members’ democratic participation through an inclusive governance model [42].

Concerning the economic activities of the cooperatives, it has been calculated that in 2016, the total turnover of European cooperatives (around 176,500 cooperative enterprises) was 1.004 billion euros with more than 4.7 million employees [43]. These numbers show the importance of a clear and exhaustive legal framework governing this type of legal entity. In fact, even if within the EU almost all countries have specific rules applicable to cooperatives, there are substantial differences among national laws. In this regard, if, on one side, the markets have an increasingly global dimension—causing the principles governing the corporate sector to become the more and more uniform, on the other side, the legal framework of cooperatives is not yet homogeneous enough [44].

Within the Italian national legal framework, cooperatives are defined by the article 2511 of the Civil code in broad terms, but the specific legislation governing the several types of existing cooperatives is contained within the so called “Codice del Terzo Settore” [45]. The several types of cooperatives differ from each other, mainly, based on the activities pursued, the societal and organizational models and the number of members.

The relevance that the cooperative model should have in the society is also highlighted in the Italian Constitution by the articles 45 and 118. According to article 45, the Italian Republic recognizes the social and economic function of cooperatives as well as the importance of their mutual nature. The article 118 states the importance of the cooperative model through the introduction of the so-called “horizontal subsidiarity” principle [46], which envisages that “Government, Regions, Provinces and Cities encourage the autonomous individual or associated citizens’ initiative for the development of activities of general interest”. As widely argued by several academics [47], the so-called “horizontal subsidiarity” principle was introduced in the Constitution with the idea that the exercise of power would have been better administrated when not publicly governed or, if public, placed as near as possible to the community and the individuals.

Therefore, the principle has gradually assumed a partially different meaning and, nowadays, it is mainly referring to the multilevel governance system that characterizes more and more the allocation of the power of central government [48].

The CC is based on a form of cooperation that arises from common actions and that creates social and economic value through the production and management of community goods within a participatory and inclusive way. In this sense, Mulgan et al. define this social phenomenon as “innovative activities and services that are motivated by the goal of satisfying a social need and are mainly developed and disseminated through organizations whose primary goals are social” [49,50], whereas Polman et al. have suggested a direct link between the role of social innovation and the role of civil society, stating that “social innovation refers to the reconfiguration of social practices in response to societal challenges, with the aim of improving the well-being of society, through the commitment of the actors who are part of civil society” [51].

This form of cooperative, by adopting organizational and structural models that reflect the specific needs of the territory in which it is located, triggers a transformative social innovation process. This process starts regenerating community resources, with the objective to improve living conditions and respond to the needs of local citizens (e.g., fighting depopulation, offering new job opportunities, guaranteeing essential services) [52]. In this regard, de Haan stresses how citizens’ initiatives might represent a solution, especially in the inner areas, as they can contribute to the creation of new services or to the maintenance of those services that would otherwise disappear [53].

In particular, concerning CCs in Italy, they have not been specifically regulated yet and only few regions, instead, have adopted an ad hoc regional law.

Giving the absence of a specific national legal discipline, the CCs were born on the basis of different assumptions between the north and the south of Italy. In the first case, the birth and development of CCs is connected to the citizens’ engagement within bottom-up initiatives; whereas in the second case, the public sector has played an important role. In addition another dichotomy related to the geographical area has been observed: in the center-north of Italy CCs arise in isolated and remoted areas; on the contrary, in the south of the country, the CCs are more likely to be established near the coast and in locations more populated and easily accessible by public transport [54].

Overall, CCs regional laws have emphasized the importance of:

- -

- The promotion of the locals’ skills;

- -

- The encouragement of the citizens’ participation to the productive processes and management of commons and public services, as well as the collective purchasing of services of general interest;

- -

- The satisfaction of the local community needs, especially through the development of eco-friendly activities;

- -

- The reinforcement of socio-economic context with particular attention to the disadvantaged area such as city suburbs and internal areas at risk of depopulation.

In general, one may notice that regional laws are quite similar to each other with few differences and they provide quite general and not very specific rules.

Another aspect linked to the absence of a national law about CCs is that when trying to define CCs, the term “community” creates confusion because it is commonly used to indicate several different concepts [55]. For example, in the UK, a “community finance society” is a society whose activities are aimed to raise found and finance projects or enterprises for the benefit of the local community [56], whereas in Wales, “co-communities” are mainly responsible for providing services for the care of the person, such as kindergarten, urban recovery activities, sport activities, and centers for the community.

For this reason, to clearly define the meaning of CC, it is important to identify a specific definition of what “community” means when related, as it is the aim of the article, to energy collective self-production and consumption. In this regard, to narrow the range of possible meaning of the term “community”, a useful restriction is to consider only the “physical” community, where “physical” refers to the people living in a specific territory where the community takes place. In this context, the adjective “physical” refers to the “physical” communities and it is used to distinguished them from the “virtual” ones, which are based on internet contacts rather than on person-to-person interactions.

A further feature that the authors have decided to consider to define CCs, is represented by the final goal that this particular type of cooperatives pursue. Indeed, CCs have to provide goods and/or services of general interest for the entire community. In other words, the goods and services are useful for anyone living in the considered territory and not exclusively for a specific group or people (i.e., a professional group); in addition, the goods/services are considered of general interest also for those who do not currently use them [57]. The goods and services that have these characteristics could be defined as “community goods”, thus between a community and the “community goods” there is a specific interrelationship. The production of goods and services of general interest has also been defined as “co-production”, meaning an “organized participation of citizens in the production of their own welfare services” [58].

Furthermore, CCs might be identified as multi-stakeholders [59] cooperative in light of the widening of the subjects involved (from entrepreneurships to citizens—considered by their own and not exclusively through the local administrative and politic bodies) and the interests taken into account.

In summary, a suitable definition for CCs could be the one adopted by Sforzi and Bonzaga, according to whom a CC is an “enterprise in which citizens, through the sharing of resources and purposes—first social and then economic—jointly realize their needs and personal ambitions, by grafting a cultural and political changing process that helps to overcome the State-market bipolar model which, so far, has not been able to guarantee nor the growth nor the survival of an increasing number of communities” [60].

Despite the growing importance of this legal form of cooperative, there is a lack of a precise legal status thar undoubtedly represents a difficulty for the full development of this kind of cooperative. At the same time, the absence of a precise framework may represent an advantage in same cases. In fact, if on one side the absence of a specific legal definition may reduce the development and dissemination of this type of cooperative, on the other side it avoids that too strict definitions exclude some local activities, which do not respect all requirements (i.e., because they are too young and not organized enough to respect all the legal requirements), but operates for the same social and environmental purposes and have almost all the features of those defined as CCs [61].

Summarizing, the main weakness regarding CCs are:

- -

- The absence of a clear national legal framework with the consequence that each region has its own discipline;

- -

- The absence of a national register of CCs, which might contribute to their development and in the achievement of their goals;

- -

- A wide variety of performed activities that makes it difficult to frame and define the characteristics of a CC;

- -

- A remarkable heterogeneity in the way each community is created and governed [61].

Some examples of CCs created in Italy are the “Cooperativa di Comunità Melpignano” in Puglia, the cooperative “La Volpe e il Mirtillo”, in Piemonte and the “Cooperativa di Comunità Valle dei cavalieri di Succiso” [62] in Emilia Romagna. The first one has realized several projects among which: the plant of photovoltaic panels on the roof of member’s houses; the installation of a drinking water cooler to reduce the waste of plastic; the enhancement and promotion of a public park; the creation of a project to help elder people, mums with children and teenagers in their ordinary daily life problems. The second abovementioned cooperative carries out agricultural activities to preserve and revitalize the local products; in addition, the cooperative aims at foster the ancients crafts and the passion among youngers for the mountain. Finally, the third cooperative, to revitalize an ancient village almost abandoned, has promoted several activities, including the opening of agritourism and a restaurant, guided tours in the National Park Appennino, the purchase of a bus to deliver medicines to elders and the creation of a photovoltaic plant.

In conclusion, the Italian legal framework of CCs appears partial and heterogeneous given the absence of a national law ruling this phenomenon. Therefore, it is clear the need to adopt a new corporate model to empower the role of both citizens and local communities over the supply and purchasing of public services and goods of general interest. Moreover, it stands out both the regional and national legislators’ awareness that locals’ participation is likely able to ensure more success to the initiatives aiming at the growth of local economy and the increase of social and environmental benefits.

5. RECs and CCs: Commonalities, Differences and Potential Synergies

In order to clarify why CCs are particularly suitable to implement RECs, this paragraph firstly highlights the common features between these two types of legal form and the differences. Secondly, in light of the similarities pointed out, it describes why and how the legal form of CCs could be used to implement RECs. In particular, the main common features are:

- (a)

- The stakeholders active participation in the creation and functioning of both the CCs and RECs. The active participation leads to a collective governance decision making process where decisions are taken after participants have discussed possible options and have chosen in a democratic way [63]. Indeed, the stakeholders active participation within cooperative management, according to academics, is a key element that has several positive effects [64] as the democratic governance and the direct access to information, could reduce (sometimes even remove) informative asymmetries on the services/goods provided by the cooperative [65]. This concept has been defined “collective governance” and it permits to both the natural and legal person, as well as public and private entities, to participate and to have an active role within the decision making process. Moreover, the “collective governance” principle enables the application of generated benefits “from the exclusive interest of the cooperative’s members to the general interest of the community” [61]. This concept is linked to the enforcement of collective actions, meaning “the choice by all or most individuals of the course of action that, when chosen by all or most individuals, leads to the collectively best (expected) outcome” [66]. A collective action is an organizational model/system that could be applied to both the RECs and CCs, in order to strengthen citizens’ role as an active part of regulatory process, thus producing a positive environmental, economic and social impact.

- (b)

- CCs and RECs do not have as their main goal the production of financial profit, but to create social, economic and environmental positive externalities and benefits. In particular, CCs—contrary toother forms of cooperative—apply the “enlarged mutuality” principle, which consists in the application of the benefices and positive results produced by cooperative’s activities to the entire geographical community. In fact, within CCs, all locals—and not only the members of the cooperative—should be able to take advantage of the goods and services offered by the cooperative itself [67]. The CC, by enhancing human capital, is based on organizational and management models that foster the participation of all members. Furthermore, according to the fifth cooperative principle set by the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA), all cooperatives should educate and train their members and all staff, so that everyone is able to contribute efficiently to the development of its own cooperative. Therefore, human capital does not represent a cost, but it is an active element, which has in it a priceless heritage of experiences and skills, that characterize the very essence of CCs. Citizens who participate in the community are characterized by: (1) the awareness in the enhancement of a common good, such as their own territory, (2) the awareness of being part of a shared initiative with a common objective and a common strategy and (3) the mutual trust and cohesion [68].

- (c)

- The access to CCs and to RECs is open and everyone should be able to participate without any discrimination. About the participation of locals in the decision making process, it has been evoked the “open door” policy [69], which means that whoever may be interested to goods and/or services provided by the cooperative, should be able to become a member of the cooperative without any discrimination. This thorough openness is an evidence of how CCs have to be accessible to all members of the community. In this sense, when talking about “community”, reference is made to all people living in a given area rather than to a specific professional or social group, which, on the contrary, is a major aspect that characterizes the other kinds of cooperatives (i.e., mutual cooperatives, consumers cooperatives, etc.).

- (d)

- The physical territory where the activities take place is one of the main elements of the discipline that rules CCs, which unlike other types of cooperatives, are defined as a local-based corporate model and in which the area where the activities take place and stakeholders live, is limited to a well-defined geographical area. The connection with territory is an important competitiveness factor and a value-added to the meaning of community. In fact, according to Barkley et al., “cooperatives are viewed as potentially important vehicles for community development since they can solve local problems by mobilizing local resources into a critical mass, and by virtue of being locally owned and controlled; cooperatives can keep profits and responsibility in the hands of local citizens” [70].

The proximity between the territory where activities take place (where the energy is produced) plays an important role also in the constitution of RECs. In fact, according to the Italian transitory regulation (art. 42-bis D. L. 162/2019), all members have to be connected to the same medium voltage/low voltage transformer booth that, by definition, insists on a specific territory. Moreover, the geographical proximity enables to avoid energy dispersion in long distance transmission—at least presently, nor the CCs nor the RECs have a definitive national legal framework. Even if the commonalities between CCs and RECs are significant, they also have some differences, such as:

- (a)

- At the present time, there is no European legislation for CCs, and in Italy they are not uniformly regulated because only some regions have adopted a specific law; on the contrary, RECs are regulated by the EU Directive 2018/2001, which will be transposed into a national law. CCs may be implemented to produce and offer several goods or services, such as: urban cleaning, waste collection and recycle, care of the common green areas, kindergarten, assistance to the elderly, purchase and selling of high quality products at a lower price thanks to a direct connection with the producers (especially for foods). On the other hand, RECs are exclusively created to produce, sell and use renewable energy.

- (b)

- CCs are a particular form of cooperative, which means that by definition they have a specific legal form. Differently, in the case of RECs, both the European and Italian legislator have provided the possibility to adopt different legal form, such as social cooperative, small-medium enterprises, associations, foundations. This aspect shows that RECs do not constitute in themselves a proper legal model and that they have been introduced by the EU legislator to provide a means through which EU countries could reach and improve environmental and energetic goals. For this reason, to implement a REC it is necessary to adopt a legal form that could properly assure the respect of the requirements posed by EU Directive, as well as to respect the technicalities posed by the national law.

On the contrary the other legal forms that ARERA has indicated as eligible to implement RECs, i.e.: cooperative, association, non-profit organization, consortium, public–private partnership, do not require nor such a significant importance of the territoriality, nor the same active involvement of the members of the community [12].

In this sense, according to the authors, the legal form of CCs would meet all the requirements posed by the EU and national regulations for the RECs and, at the same time, it could enhance the social capital and the human resources of the reference community [71].

6. Conclusions

In this paper, the authors explored the similarities and possible synergies between CCs and RECs in Italy. Through this, the authors carried out a careful analysis of the regulatory provisions referred to RECs implementation at EU and national level and of the national and regional laws on CCs in Italy, complemented by a review of the grey literature on CCs. However, given the current marginality of this juridical form in the cooperative landscape that has not yet attracted adequate attention in the academic field, the inquiry carried out can be considered a primary source of information on the topic. This analysis allowed the authors to highlight that a few features can be considered as common to both CCs and RECs and namely: (1) the pre-eminence of the territorial scope, intended as a very strong relationship between the physical territory where the activities of the cooperatives take place and the area where the involved stakeholders live; (2) the democratic and participatory organizational model through the application of an inclusive decision-making process and the establishment of a collective perspective; (3) the possibility that everyone—living in the interested territory—should have to join the community without any discrimination; (4) the final goal is to produce positive social, economic and environmental externalities, rather than just financial results (the realization of profits); and (5) the role of social innovation and civil society in activating a transformative social innovation process.

On the other hand, some differences could be noted, and the most significant is that RECs are exclusively used to produce renewable energy, whereas CCs are suitable to many other different scopes. Moreover, it has been argued that the lack of a specific regulatory and legal framework is one of the major problems concerning the definition and implementation of CCs.

Getting back to the research questions, Section 1, we can confirm on the basis of the results of the analysis:

- -

- A CC is an “autonomous association of people aspiring to achieve their objectives through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise”;

- -

- CCs could be a useful tool to implement RECs because of their similarities and, in particular, because of the importance that both models give to the involvement of citizens and their personal participation within the decision-making process as well as the strong connection between the physical territory and the activities carried out;

- -

- The human capital and the cooperation among citizens appear to be the key points in the development of both the CCs and RECs.

In addition, it is worth to notice that the exploitation of the characteristics of each territory, with its own social, cultural, physical and environmental peculiarities, as well as the engagement of locals, could enforce the implementation and dissemination of RECs. For this reason CCs compared to the other legal forms of cooperative appear to be an attractive solution. Indeed, the condition imposed by the EU Directive 2018/2001 about the need for the consumers of the RECs to be linked to the same low voltage distribution sub-grid, makes especially noteworthy the role of the locals in both the birth and functioning of the community itself.

If the analysis has the undoubtable merit to have raised a novel and unexplored field of potential interaction among different citizens based initiatives, as well it has the undoubtable limit of relying on just desk research and literature review. A limit that is made even stronger by the object itself (i.e., a social innovative experience) that would require additional field research effort. In this light, the intention of the authors is to proceed in investigating how to better define and implement CCs with the ambition of defining possible strategies for their implementation and assessing the extent to which they can actually affect the energy transition trajectories. At this aim qualitative insights should be made through the involvement of the subjects (public administrations, energy companies, citizens, policy makers, non-profit organizations, researchers and academics) that are actively involved in different ways in the development of both CCs and RECs. Interviews, focus groups and participatory methods to find a consensus on proper definitions of the factors and dynamics at stake could help to understand how these subjects perceive: the cooperative/community functioning; which are the strengths and the weaknesses of the two legal forms; in which way and how policy makers intend to promote the implementation of bottom-up initiatives based on the active involvement of stakeholders (through technical regulations, laws, economic incentives, collective action initiatives, creation of public events of endorsement and questionnaires).

Author Contributions

A.G. conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, writing of Section 1, Section 2, Section 3, Section 4, Section 5 and Section 6; M.G. formal analysis, resources, investigation, methodology, visualization; A.S. methodology, supervision, review—editing; D.P. supervision, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under Grant Agreement No 890362—eCREW: establishing Community Renewable Energy Webs.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this study wish to acknowledge Anna Maria Porporato and Edoardo Ferrero for their suggestions and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- European Commission. Energy: Energy Communities. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/topics/markets-and-consumers/energy-communities_en (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Energy & Strategy Group. Le Prospettive di Sviluppo delle Energy Community in Italia, in Smart Grid Report, 2014, MIP/Politecnico di Milano. Available online: http://bit.ly/1I6Jd0X (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Butera, F. Dalla Caverna alla Casa Ecologica: Storia del Comfort e dell’Energia; Edizioni Ambiente: Milano, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- GECO. Le Comunità Energetiche in Italia: Una Guida per Orientare i Cittadini nel Nuovo Mercato dell’Energia; Progetto Europeo GECO: Roma, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.; Frieden, D.; D’Herbemont, S. Energy Community Definitions—Explanatory Note; COMPILE: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperative di Comunità. Opportunità di Sviluppo per il Bene Comune”, Legacoop. Available online: https://www.legacoop.coop/cooperativedicomunita (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Articles 33–35 of the Regulation (EU) N. 1303/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013. Off. J. Eur. Union 2013, 347, 33–35.

- Candelise, C.; Ruggieri, G. Status and Evolution of the Community Energy Sector in Italy. Energies 2020, 13, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magnani, N.; Osti, G. Does civil society matter? Challenges and strategies of grassroots initiatives in Italy’s energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, P.A.; Spinicci, F. La Cooperazione di Utenza nei Servizi Pubblici: Un’indagine Comparata, Le Cooperative di Utenza in Italia e in Europea, 2011, EURICSE. Available online: https://www.euricse.eu (accessed on 6 February 2021).

- Incerti, C.; De Maria, P.Z. Draft Law n. 288 Presented to the Deputies Chamber of the Italian Republic; XVIII Legislature; Camera dei Deputati: Rome, Italy, 23 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ARERA. Available online: https://www.arera.it/it/index.htm (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Oteman, M.; Wiering, M.; Helderman, J.-K. The institutional space of community initiatives for renewable energy: A comparative case study of the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yildiz, Ö.; Rommel, J.; Debor, S.; Holstenkamp, L.; Mey, F.; Müller, J.R.; Radtke, J.; Rognli, J. Renewable energy cooperatives as gatekeepers or facilitators? Recent developments in Germany and a multidisciplinary research agenda. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, T.; Schmid, B.; Seidl, I.; Klagge, B. How municipalities support energy cooperatives: Survey results from Germany and Switzerland. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2020, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde, S.; Rossetto, N. The Future of Renewable Energy Communities in the EU: An Investigation at the Time of the Clean Energy Package, Florence School of Regulation; European University Institute: Fiesole, Italy, August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Spasova, D.; Braungardt, S. Building a Common Support Framework in Differing Realities—Conditions for Renewable Energy Communities in Germany and Bulgaria. Energies 2021, 14, 4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeiro, S.; Dias, M.F. Renewable energy community and the European energy market: Main motivations. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebi, C.; Vernay, A.-L. Community renewable energy in France: The state of development and the way forward. Energy Policy 2020, 147, 111874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, A. Energy justice at the end of the wire: Enacting community energy and equity in Wales. Energy Policy 2017, 107, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energie Partagée, Rapport D’activité 2020. Available online: https://energie-partagee.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Energie-Partagee-Rapport-dactivite-2020.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Capellán-Pérez, I.; Campos-Celador, Á.; Terés-Zubiaga, J. Renewable Energy Cooperatives as an instrument towards the energy transition in Spain. Energy Policy 2018, 123, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, T. The Political Economy of Interrupted Energy Transitions: The Case of Spain, Working Paper. In Proceedings of the IST Conference, Manchester, UK, 11–14 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heras-Saizarbitoriaa, I.; Sáezb, L.; Allura, E.; Morandeira, J. The emergence of renewable energy cooperatives in Spain: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I.; Pontes Luz, G.; Marín-Gonzalez, E.; Gahrs, S.; Hall, L. Holstenkamp, L. Regulatory challenges and opportunities for collective renewable energy prosumers in the EU. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111212. [Google Scholar]

- Frieden, D.; Tuerk, A.; Neumann, C.; d’Herbemont, S.; Roberts, J. Joanneum Research, REScoop.eu. In Collective Self-Consumption and Energy Communities: Trends and Challenges in the Transposition of the EU Framework; Working paper; COMPILE: Ljubljana, Slovenia, December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Toporek, M.; Provost, L. Guidance for National Transposition of New EU Directives Relating to Renewable Energy Prosumers, PROSEU—Prosumers for the Energy Union: Mainstreaming Active Participation of Citizens in the Energy Transition; Deliverable n. 3.5; PROSEU: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, L 328, 82. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32018L2001 (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Chamber of Deputies. Governance Europea e Nazionale su Energia e Clima. Research Department. 2020. Available online: https://www.camera.it (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Article 42-bis of the Law Decree. n. 162/2019 Converted with Law February 28, 2020. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/02/29/20A01353/sg (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Bevilacqua, C. Le Comunità Energetiche tra Governance e Sviluppo Locale. Amministrazione in Cammino. 2020. Available online: www.amministrazioneincammino.luiss.it (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Deliberazione, 4 August 2020, 318/2020/R/EEL, ARERA. Available online: https://www.arera.it (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Energy Center Lab del Politecnico di Torino. Le Comunità Elettriche per una Centralità Attiva del Cittadino nel Nuovo Mercato Dell’energia Elettrica. 2020. Available online: https://www.energycenter.polito.it (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Regolazione delle Partite Economiche Relative All’energia Elettrica Condivisa da un Gruppo di Autoconsumatori di Energia Elettrica Rinnovabile che Agiscono Collettivamente in Edifici o Condomini Oppure Condivisa in Una Comunità Energetica di Energia Rinnovabile. 318/2020/R/EEL, 4 August 2020 ARERA, p. 3. Available online: https://www.arera.it (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Gruppo Professione Energia. Comunità dell’Energia: Approfondimenti per il Recepimento Nazionale e Analisi Comparata delle Leggi Regionali sulla Promozione delle Comunità dell’Energia. 2019. Available online: http://www.enusyst.eu (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- RSE, Gli Schemi di Autoconsumo Collettivo e le Comunità dell’Energia, Dossier 17/2020. Available online: https://dossierse.it (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Memoria, 12 March 2019, 94/2019/I/COM, ARERA. Available online: https://www.arera.it (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Senato della Repubblica Italiana, Ufficio Valutazione Impatto, Green Energy. Il Sostegno alle Attività Produttive Mediante Generazione, Accumulo e Autoconsumo di Energia Elettrica Consultazione Pubblica della 10th Commissione Permanente sull’Affare Assegnato n. 59, January 2019. Available online: https://www.senato.it (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Orientamenti per la Regolazione delle Partite Economiche Relative all’Energia Oggetto di Autoconsumo Collettivo o di Condivisione nell’Ambito di Comunità di Energia Rinnovabile, 112/2020/R/EEL, 1 April 2020, ARERA. Available online: https://www.arera.it (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Karakas, C. Cooperatives: Characteristics, Activities, Status, Challenges, European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS), PE 635.541. 2019. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Fici, A. Recognition and legal Forms of Social Enterprise in Europe: A Critical Analysis from a Comparative Law Perspective, in Euricse Working Papers, 2015, n. 82|15. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2705354 (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Mazzarol, T.; Simmons, R.; Limnios, E.M.; Reboud, S.; Clark, D. A conceptual framework for research into co-operative enterprise. In Research Handbook on Sustainable Co-Operative Enterprise; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 22–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cooperative Europe. The Power of Cooperation: Cooperatives Europe Key Figures 2015. Available online: https://coopseurope.coop (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Fici, A. Cooperative Identity and the Law, in Euricse Working Paper, N. 23/2012. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2005014 (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. Legislative Decree 3 July 2017 n.117. 2017. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/08/02/17G00128/sg (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Cassese, S. L’Aquila e le Mosche. Principio di Sussidiarietà e Diritti Amministrativi nell’Area Europea, in Foro It., 1995, V, p. 373. I. Massa Pinto, Il Principio di Sussidiarietà; Profili Storici e Costituzionali: Napoli, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- D’Atena, Sussidiarietà Orizzontale e Affidamento “in House”. 2008. Available online: www.forumcostituzionale.it (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Renna, V.M. L’allocazione delle Funzioni Normative e Amministrative, in G. Rossi (a Cura di), Diritto dell’Ambiente, p. 135 e ss., p. 145; M. Petrachi, Declinazioni del Principio di Sussidiarietà in Materia di Ambiente, 14 December 2016. Available online: https://www.federalismi.it (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Polman, N.; Slee, B.; Kluvánková, T.; Dijkshoorn, M.; Nijnik, M.; Gezik, V.; Soma, K. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas. 2017. Available online: www.simra-h2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/D2.1-Classification-of-SI-for-MRAs-in-the-target-region.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Mulgan, G. The Process of Social Innovation; Spring: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Commissione Europea. New Trends in Social Innovation. 2017. Available online: Ec.europa.eu/research/sam/pdf/es-pt_academia/new_trends_in_social_innovation_mgc.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Gazzetta ufficiale dell’Unione Europea. Parere del Comitato europeo delle regioni—Strategia dell’UE per rivitalizzare le comunità rurali, C37/16, 2021. Off. J. Eur. Union 2020, 37, 16. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, E.; Meier, S.; Haartsen, T.; Strijker, D. Defining ‘success’ of local citizens’ initiatives in maintaining public services in rural areas: A professional’s perspective. Sociol. Rural. 2017, 58, 12173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bandini, F.; Medei, R.; Travaglini, C. Territorio e persone come risorse: Le cooperative di comunità, in Rivista impresa sociale, n. 5/09-2015. Impresa Soc. 2015, 5, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bristow, G.; Cowell, R.; Munday, M. Windfalls for whom? The evolving notion of ‘community’ in community benefit provisions from wind farms. Geoforum 2012, 43, 1108–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- For Example the Exeter Local Food Ldt., is a Community Finance Society That Has a Grocery Store in the Neighborhood. Available online: http://www.realfoodexeter.co.uk/what-is-the-real-food-store (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Mori, P.A. Comunità e Cooperazione: L’evoluzione delle Cooperative verso Nuovi Modelli di Partecipazione Democratica dei Cittadini alla Gestione dei Servizi Pubblici; Working Paper n. 63/14; Euricse: Trento, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pestoff, V.; Osborne, S.P.; Brandsen, T. Paterns of co-production in public services: Some concluding thoughts. Public Manag. Rev. 2006, 8, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellens, L.; Jegers, M. Effective Governance in Nonprofit Organizations: A Literature Based Multiple Stakeholder Approach. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sforzi, J.; Bonzaga, C. Imprese di comunità e riconoscimento giuridico: È davvero necessaria una nuova legge? Riv. Impresa Soc. 2019, 13, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, T.; de Vries, G. Social innovation and the energy transition. Sustain. Svizzera 2018, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooperativa di Comunità Valle dei Cavalieri, Cooperativa Valle dei Cavalieri: Cooperativa di Comunità nel Parco Nazionale dell’Appennino Tosco Emiliano. Available online: https://valledeicavalieri.it/wp/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Sacchetti, S. Saggio/Perché le imprese sociali devono avere una governance inclusiva. Riv. Impresa Soc. 2018, 2018, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; Mehmood, A.; MacCallum, D.; Leubolt, B. Social Innovation as a Trigger for Transformations, 2017. The Role of Research, DG Research and Innovation; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, P.A. Cooperazione di comunità e la partecipazione dei cittadini alla gestione dei servizi pubblici. Riv. Impresa Soc. 2015, 5, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Padovan, D.; Arrobbio, O.; Sciullo, A.; Gilcrease, W.; Gregg, J.S.; Henfrey, T.; Wierling, A.; Schwanitz, V.J. Collective Action Initiatives. Some Theoretical Perspectives and a Working Definition; COMETS: Torino, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Depetri, S.; Turri, S. Dalla funzione sociale alla cooperativa di comunità: Un caso studio per discutere sul flebile confine. Riv. Impresa Soc. 2015, 5, 544. [Google Scholar]

- Gonella, D. Le Cooperative di Comunità. Cooperativeonline.it. 2020. Available online: hcooperative-online.it/la-cooperativa-di-comunità (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Recommendation on the Promotion of Cooperatives, n. 193/2002, Which Has Adopted the Statement on the Cooperative Identity Adopted by the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) in 1995; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zeuli, K.; Freshwater, D.; Markley, D.; Barkley, D. Cooperatives in Rural Community Development: A New Framework for Analysis. J. Community Dev. Soc. 2004, 35, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricarico, L. Caso studio/Energia come community asset e orizzonte di sviluppo per le imprese di comunità. Riv. Impresa Soc. 2015, 5, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).