Abstract

Excision of lesions in the periparotid area can leave a sizable concavity of the preauricular area with skeletonization of the mandible. To achieve the bulk necessary to fill this defect, we propose using a composite graft. Acellular human dermal allograft provides the thickness of the graft, and the temporoparietal fascia flap provides blood supply to the dermal graft. Our hypothesis is that vascularization of the graft will promote greater ingrowth of native tissue and prevent breakdown and absorption of the graft. Four representative patients are described.

Facial soft tissue defects can be bothersome and embarrassing to patients after surgical or traumatic injury. Parotidectomy is undertaken for many different types of benign or malignant lesions. Typical superficial parotidectomy does not leave a large defect, but deep lobe parotidectomy, total parotidectomy, and any excision of a large tumor can decrease fullness of the periparotid area. The primary concerns are of course to assure full extirpation of the neoplasm and preserve function of the facial nerve, but cosmetic reconstruction should not be neglected when the defect is severe. In addition, other neoplasms of the infratemporal fossa require an approach through the lateral face, which can leave a noticeable cosmetic deficit. Traumatic injury to the face may also leave a concave area in the preauricular area, which only leads the eye toward any scars from the injury.

A variety of methods of reconstruction in this area of the face have been described in the literature. These include dermal fat grafts [1], temporalis muscle graft, temporoparietal fascia flap [2], and sternocleidomastoid muscle flaps [3,4]. Each of these options has some drawbacks, in either bulk provided for filling the defect initially or concerns for resorption of mass over time.

A series of case reports is described using an alternative method of filling the described periparotid defect, using a combination of acellular human dermal autograft (AlloDerm, LifeCell, NJ; Synthes, Paoli, PA; SureDerm, Hans Biomed, Seoul, Korea) with a temporoparietal fascia flap.

Methods

Four patients are presented who underwent reconstruction of periparotid soft tissue defect through placement of a combined acellular dermal allograft-temporoparietal fascia flap. Informed consent for the procedure was obtained, including discussion of possible disease transmission risks. The graft used is an acellular dermal matrix derived from donated human skin tissue to strictly regulated tissue banks. Processing occurs to remove the epidermis and all cells from the dermal layer, leaving the infrastructure of the dermis intact. This matrix includes intact collagen, elastin, proteoglycans, and hyaluronans. The tissue is then freeze-dried to preserve its structure until rehydration at the time of surgical implantation. Over time, the patient’s own cells and tissue will grow into the established matrix.

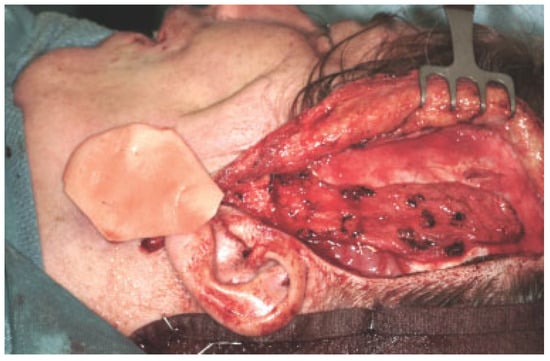

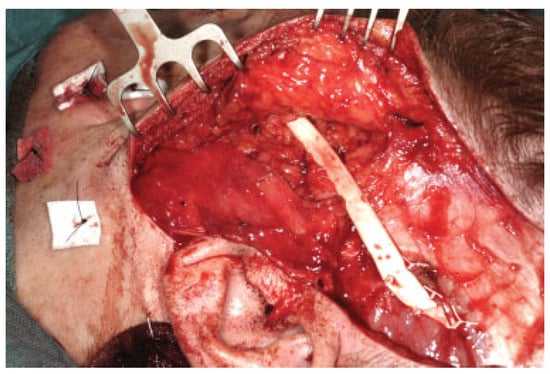

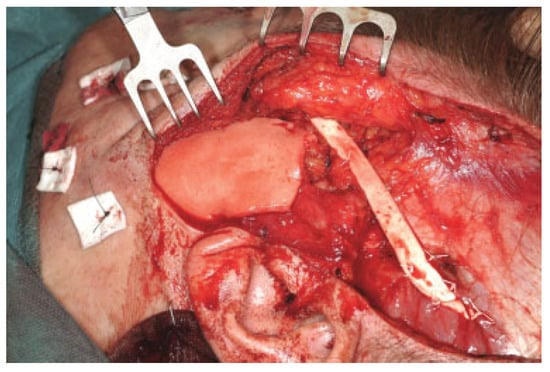

The surgical techniques used in our four patients began with evaluation of the area to be augmented. Figure 1 demonstrates the area of deep augmentation with a precontoured acellular dermis sheet over the preauricular and perimandibular region. A standard parotidectomy incision was performed with elevation of the flap anteriorly to provide access to the depression from prior surgery. After raising this flap, the incision was continued posterosuperiorly into a T- shaped incision in the temporal region. This allowed for immediate subcutaneous dissection using cautery overlying the temporoparietal fascia. A flap measuring ~10 cm in length by 4 to 6 cm in width was then carefully harvested off the loose areolar plane overlying the superficial layer of the deep temporal fascia and the temporalis muscle (Figure 2). Care was taken to harvest the flap with the previously identified (by Doppler probe and by visualization) posterior branch of the superficial temporal artery. Attention was then turned to the cheek defect. Approximately two to four layers (depending on the size and contour of the defect) of acellular dermal allograft graft were laid in the wound and secured in place with resorbable suture. The temporoparietal fascia flap was then rotated into place over the acellular dermal allograft and likewise secured in place (Figure 3). Following this, another two to four layers of the dermal allograft were place over the fascial flap and this was secured in place (Figure 4). A suction drain was placed over the area and skin was then closed in layers. The scalp was closed in two layers. Typical antibiotic coverage was used while the drain was in place.

Figure 1.

Proposed placement of the deeper layer(s) of the acellular dermis.

Figure 2.

Elevation of the temporoparietal fascia flap.

Figure 3.

The temporoparietal fascia flap is transposed inferiorly over the previous positioned deep layer(s) of acellular dermis. An expanded polytetrafluoroethylene implant is also used as a facial sling in this patient (Case 2, Figure 6).

Figure 4.

The final layers of acellular dermis are place over the temporoparietal fascia flap and under the skin flap.

Of the four patients treated, one was reconstructed from a typical facial concavity 6 years after total parotidectomy for malignancy metastatic to this gland. The second was a case of a posttraumatic injury from childhood, reconstructed in our patient as an adult. The third case was a young woman who had undergone removal of a malignant infratemporal fossa lesion as a young child with a significant defect that was worsened by growth disturbance. The fourth case was a young girl also with a malignant tumor of the infratemporal fossa after extirpation with the resulting defect treated while still a child.

Case Reports

Case 1

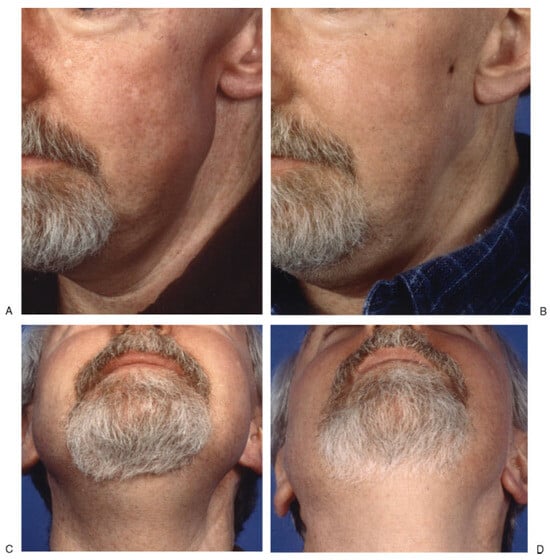

Patient 1 was a 53-year-old man 6 years status postexcision of a squamous skin malignancy metastatic to the left parotid gland presented with a large left-sided defect of the preauricular, cheek, and retromandibular area. The patient was very self-conscious about this defect and felt it affected his daily life in regards to his self-perception of his appearance (Figure 5A–D). He underwent reconstructive surgery with four layers of dermal allograft both deep and superficial to the temporoparietal fascia flap (TPFF). His postoperative course was uncomplicated and he was very pleased with the results at 1 year. We describe moderate improvement with good filling of the infra-auricular depression but ideally would have preferred more bulk laterally (creating more symmetry on frontal view).

Figure 5.

Case 1: A 53-year-old man 6 years after total parotidectomy. Oblique and submental views pre- (A and C) and postsurgery (B and D).

Case 2

Patient 2 was a 33-year-old woman presented who was 28 years status posttraumatic dog-bite injury to the face with a significant soft tissue defect in the left cheek and retromandibular area as well as a facial paralysis on the left from facial nerve injury. She was very emotionally burdened by the scarring and facial paralysis and sought a more functional reconstruction than was available when her face was repaired as a toddler (Figure 6A–D). She underwent reconstructive surgery in with two layers of dermal allograft deep to and one layer superficial to the temporoparietal fascia flap to provide bulk to the depression in the area of the mandibular angle. Concomitantly she had several procedures for static facial suspension including an upper eyelid gold weight, functional left endoscopic brow-lift, midface lift, and an expanded polytetrafluoroethylene implant. She has since undergone two additional procedures to place a gold weight in the upper eyelid and septorhinoplasty.

Figure 6.

Case 2: A 33-year-old woman after avulsive dog bite injury as 5-year-old child. Note the vertical preauricular 8-cm scar. She also has complete facial paralysis. Oblique and submental views pre- (A and C) and postsurgery (B and D).

Results

In our experience, there was limited or no morbidity at the donor site. The very mild thinning of the scalp in this area was unnoticeable, and the skin closure was performed entirely within the hair-bearing scalp. Care was taken to cut parallel to the hair follicles and to ensure that dissection of the flap did not remove follicles from the subcutaneous tissue. In addition, in each of the cases moderate to excellent improvement was noted with use of this combination flap and graft. In all patients, the skeletonization of the mandible was corrected, and most gained enough bulk in their periparotid region to achieve increased symmetry. Most noticeably, on profile the dark shadow drawing attention to the preauricular scar was removed by filling in this soft tissue defect. Unfortunately, one patient had subsequent infra-auricular drainage, which resulted in exploration of the wound. The superficial two layers of the dermal allograft had become infected and were removed. The temporoparietal fascia flap was still intact and viable, however, with some loss of bulk.

Discussion

We describe a combined application of two known techniques for soft tissue reconstruction of the periparotid region. Reports in the literature since 1996 describe the use of acellular dermal allograft for facial soft tissue augmentation [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Descriptions in the literature exist of the use of dermal allografts or the temporoparietal fascia flap in this specific region in an attempt to address Frey’s syndrome [13,14,15,16], but give little attention to the soft tissue defect associated with parotidectomy. Only one of our cases was at risk for Frey’s syndrome, and this was not evident in him 6 years after parotidectomy.

We used an acellular, cadaveric dermal graft that had been processed to remove any infectious or immunogenic material. What remained was the dermal framework of collagen, vascular channels, elastin, and other proteins of the dermal matrix in a freeze-dried form. When reconstituted, this graft was implanted into the wound and the patient’s own cells grew into the framework to provide soft tissue replacement. One concern our technique addresses is the possibility for breakdown of the graft if cellular ingrowth does not progress fast enough (i.e., if the acellular dermal graft is too big).

Other flaps or grafts previously discussed have specific drawbacks to prevent their frequent use. Dermal fat grafts require a separate operative site, often in the abdomen. Sternocleidomastoid muscle flaps must be carefully harvested to avoid injury to surrounding structures such as the spinal accessory nerve as well as to preserve enough of the variable blood supply to keep the flap viable. The temporoparietal fascial flap is inadequate in size on its own to fill the defect we describe.

Vascularization of the acellular dermal graft would theoretically lesson resorption by allowing for cellular ingrowth from multiple locations. A key candidate for this purpose is the temporoparietal fascial flap. This flap has been described as ultra-thin, durable, vascular, and provides very little donor site morbidity [2,17]. Used as a pedicled flap, we postulate the TPFF will aid in longer retention of volume of a dermal allograft in a periparotid defect.

The use of dermal allografts is now quite established in soft tissue augmentation and repair [18,19] and has been shown to be a workhorse in filling defects in soft tissue bulk [10,11,20]. However, resorption has been demonstrated to be unpredictable and certainly even more likely when layered. More studies would be necessary to demonstrate just how much of the embedded material actually contributes to the final form, with follow-up examination of the grafted tissues with biopsy or magnetic resonance imaging. The technique we describe serves to add another source of viable, vascularized tissue in contact with the dermal allograft. Use of the wellestablished temporoparietal fascia flap gives the dermal allograft the opportunity to integrate into the flap as well as the deep and superficial tissues in the wound bed. This flap has little donor site morbidity especially when used as a pedicled flap in the preauricular location. None of our patients suffered any morbidity in the supra-auricular and temporal scalp. Scars from harvesting this flap are invisible within the hair, and alopecia is prevented by good surgical technique. Combined application potentially allows for filling a much larger defect than either technique alone while preserving vascularity and therefore improving maintenance of thickness of the dermal allograft implant. We did demonstrate that vascularization of the graft does not prevent seroma and infection if typical surgical care is not maintained. In our one wound infection, the flap and some of the dermal allograft remained viable, but two layers of the dermal allograft had to be removed due to infection. These were easily removed at the time of surgery because they had not become integrated into the tissues. This is felt to be from seroma formation with secondary infection, likely from removing the drain too early. However, in the other three described cases, the bulk provided by this large combined material flap has led to a cosmetic outcome, which is much improved over the preexisting defect.

In conclusion, this case series suggests some promise for this technique and warrants further investigation in this difficult subset of reconstruction patients.

References

- Thompson, N. Transplantation of dermis. In Reconstructive Plastic Surgery, 2nd ed.; Converse, J.M., Ed.; WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 1977; pp. 240–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cheney, M.L.; Varvares, M.A.; Nadol, J.B., Jr. The temporoparietal fascial flap in head and neck reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1993, 119, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugis, S.P.; Young, J.E.; Archibald, S.D. Sternocleidomastoid flap following parotidectomy. Head Neck 1990, 12, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kierner, A.C.; Zelenka, I.; Gstoettner, W. The sternocleidomastoid flap—Its indications and limitations. Laryngoscope 2001, 111, 2201–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achauer, B.M.; VanderKam, V.M.; Celikoz, B.; Jacobson, D.G. Augmentation of facial soft-tissue defects with Alloderm dermal graft. Ann Plast Surg 1998, 41, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beran, S.J. The potential role of autologous, injectable, dermal collagen (Autologen) and acellular dermal homograft (AlloDerm) in facial soft tissue augmentation. Aesthet Surg J 1997, 17, 420–422. [Google Scholar]

- Costantino, P.D.; Govindaraj, S.; Hiltzik, D.H.; Buchbinder, D.; Urken, M.L. Acellular dermis for facial soft tissue augmentation: Preliminary report. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2001, 3, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, F.R.; Schwartz, B.M.; Silverstein, P.; et al. Use of a nonimmunogenic acellular dermal allograft for soft tissue augmentation: A preliminary report. Aesthet Surg J 1996, 16, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, S.; Rohrer, T.; Grande, D. Use of dermal grafts in reconstructing deep nasal defects and shaping the ala nasi. Dermatol Surg 2001, 27, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sclafani, A.P.; Romo, T., III; Jacono, A.A.; McCormick, S.A.; Cocker, R.; Parker, A. Evaluation of acellular dermal graft (AlloDerm) sheet for soft tissue augmentation: A 1-year follow-up of clinical observations and histological findings. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2001, 3, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sclafani, A.P.; Romo, T., III; Jacono, A.A.; McCormick, S.; Cocker, R.; Parker, A. Evaluation of acellular dermal graft in sheet (AlloDerm) and injectable (micronized AlloDerm) forms for soft tissue augmentation. Clinical observations and histological analysis. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2000, 2, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Terino, E.O. Alloderm acellular dermal graft: Applications in aesthetic soft-tissue augmentation. Clin Plast Surg 2001, 28, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clayman, M.A.; Clayman, L.Z. Use of AlloDerm as a barrier to treat chronic Frey’s syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001, 124, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, U.K.; Saadat, D.; Doherty, C.M.; Rice, D.H. Use of AlloDerm implant to prevent Frey syndrome after parotidectomy. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2003, 5, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindaraj, S.; Cohen, M.; Genden, E.M.; Costantino, P.D.; Urken, M.L. The use of acellular dermis in the prevention of Frey’s syndrome. Laryngoscope 2001, 111 Pt 1, 1993–1998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rubinstein, R.Y.; Rosen, A.; Leeman, D. Frey syndrome: Treatment with temporoparietal fascia flap interposition. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999, 125, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pollice, P.A.; Frodel, J.L., Jr. Secondary reconstruction of upper midface and orbit after total maxillectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998, 124, 802–808. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fisher, E.; Frodel, J.L. Facial suspension with acellular human dermal allograft. Arch Facial Plast Surg 1999, 1, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frodel, J.L. Primary facial rehabilitation in facial paralysis after extirpative surgery. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2000, 2, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwade, N.; et al. Implants, Soft Tissue, AlloDerm. Available online: http://www.emedicine.com/ent/topic377.htm (accessed on 2007).

© 2012 by the author. The Author(s) 2012.