Abstract

We report a case of a toothbrush head lodged into the nasal cavity, which required an external rhinoplasty for retrieval. A review of the literature on management strategies in case of nasal foreign bodies is presented.

Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs) are commonly encountered in emergency departments. Although more frequently seen in the pediatric setting, they can also affect adults, especially those with mental retardation or psychiatric illness. [1] Children’s interests in exploring their bodies make them more prone to lodging foreign bodies in their nasal cavities. In addition, they may also insert foreign bodies to relieve preexisting nasal mucosal irritation or epistaxis. [1] As benign as an NFB may seem, it harbors the potential for morbidity and even mortality if the object is dislodged into the airway.

Foreign bodies are either animate or inanimate. [2] The most commonly identified inanimate foreign bodies include rubber erasers, paper wads, pebbles, beads, marbles, beans, safety pins, washers, nuts, sponges, and chalk. Others are plasticine, pieces of wood, a door handle, metal hooks and eyes, pieces of cloth, bullets, thimbles, shrapnel, umbrella springs, iron bolts, corks, and coins. [2]

A loose foreign object in the postnasal space can accidentally be aspirated or pushed back in an attempt at removal and may result in acute respiratory obstruction. Foreign bodies in the nose have been implicated as carriers of the causative organisms of diphtheria and other infectious diseases. [3] It therefore appears that foreign bodies in the nose can create a real problem and should not be taken lightly.

Here we present a rare case of a 42-year-old woman with a toothbrush lodged into her nose, which required surgical removal. A review of management strategies in the management of NFBs is presented.

Case Report

A 42-year-old woman reported to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery with a toothbrush head lost in her nose. On careful elicitation of related events, we discovered that she had reportedly placed the tooth-brush into her nose to relieve herself of the irritable itching she was experiencing in her nose. She suffered from allergic rhinitis since childhood and frequently experienced nasal itching especially in the early morning hours. In this instance, she slipped on a wet floor and the resultant fall caused the tooth brush to snap into two pieces leaving the brush head inside the nose. The accident caused profuse nasal bleeding, which was controlled by the patient with finger pressure using a handkerchief. A computed tomographic (CT) evaluation was undertaken at a radiodiagnosis center (Figure 1) on the recommendation of a primary health care facility she had visited initially. An attempt was made at the primary health center to retrieve the brush head with a curved hemostat, which proved unsuccessful and led to a further episode of epistaxis. She was then referred to our center. She was brought to our department 3 hours after the accident. Visual inspection of the nasal cavity revealed right-sided vestibulitis with clotted blood in the right nasal cavity. The toothbrush head could not be seen on visual inspection with a nasal speculum and headlamp. Visual inspection of the pharynx was unremarkable. The patient did not complain of right nasal obstruction. The patient confirmed that she had not swallowed any portion of the object. The CT showed the presence of the toothbrush head in the superior right nasal cavity at the junction between the lateral and medial nasal walls. The brush head had caused a deviation of the nasal septum to the left (Figure 2). The patient was prepared for nasal endoscopy. The right nasal cavity was sprayed with a local anesthetic aerosol agent (lidocaine USP 15%, ICPA Health Products Ltd., Mumbai, India) and phenylephrine 0.25% applied on a cotton pellet. After 5 minutes, an endoscope was introduced into the right nasal cavity and showed a large wound in the upper part of the nasal cavity with clotted blood on the surface. No object could be identified in the nasal cavity. The patient was prepared for surgery under regional anesthesia. The patient was placed in a supine position with the head elevated ~20 degrees. The forehead, nose, and face were prepared with an antiseptic solution (2% cetavlon followed by alcohol). The nasal cavities were packed loosely with 1-cm ribbon gauze soaked in 4% lignocaine for 15 minutes. Anesthesia of the external nose was achieved using bilateral infraorbital nerve blocks (lignocaine 2% with 1:200,000 adrenaline, Xicaine, ICPA Health Products Ltd., Mumbai, India) with additional infiltrations at the base of the columella, the dorsum of the nose, the infratrochlear nerve, and the external nasal nerves, and about 0.5 mL of the solution was injected into the membranous septum. An open rhinoplasty approach with a transcolumellar extension was used. A marginal incision along the caudal border of the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages was made and carried medially and inferiorly along the cephalic border of the medial crus up to its lower part and then extended with a right angle turn to the caudal margin of the medial crus. A combination of sharp and blunt dissection was used to expose the entire nasal skeleton up to the nasal bones. The object was found to be lodged between the upper-right lateral cartilage and the nasal septum, with its bristles embedded into the right-upper lateral cartilage and the nasal septum (Figure 3). Dissection of the object from between the upper lateral cartilage and the nasal septum was performed after incising the upper-right lateral cartilage submucosally from the nasal cartilage and then proceeding with the exposure of the nasal septal cartilage. The object was delivered in one piece (Figure 4). Hemostasis was achieved with the use of electrocautery where indicated. Closure of the wound was achieved with polyglycolic acid 910 for the nasal mucosa and the nasal cartilages. Skin closure was achieved with prolene sutures. Bilateral nasal packs were placed. No intraoperative or postoperative complications were witnessed, and the patient was discharged on the third postoperative day.

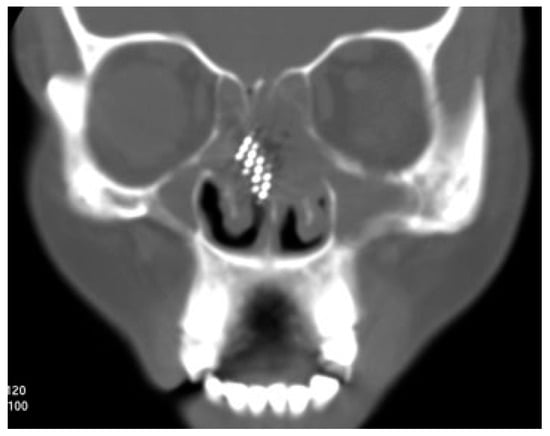

Figure 1.

Coronal computed tomography image showing position of the foreign body.

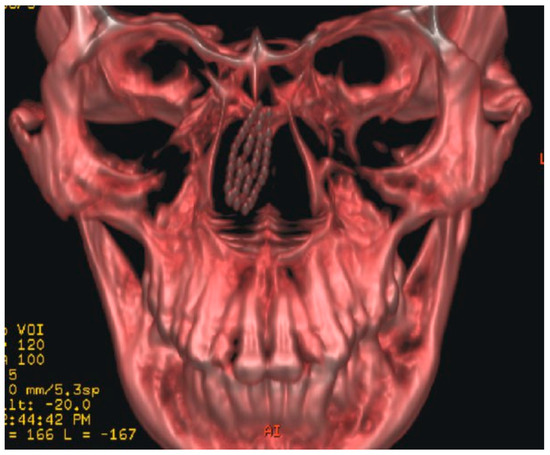

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of computed tomography images showing position of the foreign body.

Figure 3.

Toothbrush head located between the right-upper lateral cartilage and the nasal septum.

Figure 4.

Toothbrush head retrieved from the nasal cavity.

Discussion

NFBs are either inanimate objects or, less commonly, animate. NFBs can be found in any portion of the nasal cavity, although they are typically discovered around the floor of the nose just below the inferior turbinate. Another common location is immediately anterior to the middle turbinate. [4] Any article small enough to be admitted into the anterior nasal orifice has, at one time or the other, been removed from the nose. [2,4] Foreign bodies that are impacted or those that have been present for some time and have become encrusted or those that have been impacted with force frequently challenge removal. [2]

A toothbrush is one of the most familiar commodities of everyday use, and few people would ever think about the risk of using it. However, such an accident seldom becomes fatal. A toothbrush causing nasal injury is very rare.

Toothbrushes are commodities used worldwide, regardless of age, gender, and ethnicity, and our case provides a warning that a toothbrush may cause a serious injury, especially when involving children. In our case, the patient accepted the fact that this was not the first time she was using the toothbrush head for the purpose reported. She had started using the toothbrush head owing to its soft nature in comparison to other available household objects. However, physical abuse should be always considered in such cases, although in our case there was no evidence for this on the basis of history and physical examination.

The advantage of an open rhinoplasty approach is that the surgeon can observe the whole framework of the external nose with efficient bimanual surgical dissection while providing a cosmetically acceptable result. [5,6] Although this approach provides good surgical exposure, thorough surgical exploration is often required as was the case in our patient.

The foreign body was intranasal but submucosal, between the nasal mucosa and the nasal septal cartilage rather than in the nasal lumen proper (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). This could be the most likely reason for failure of the previous attempt to retrieve the object with a hemostat. An open rhinoplasty was the most suitable approach for this case.

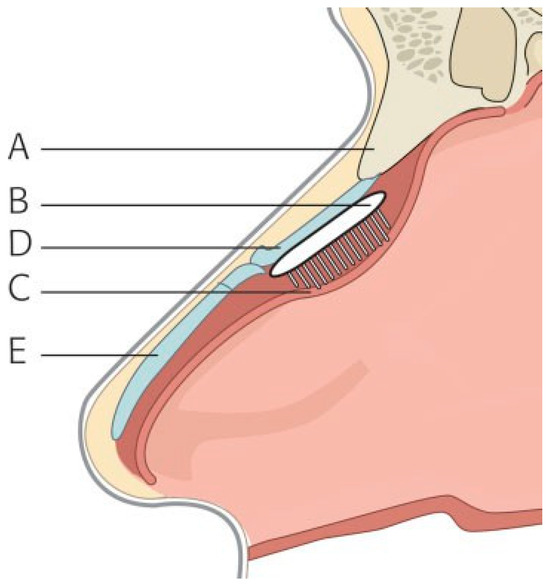

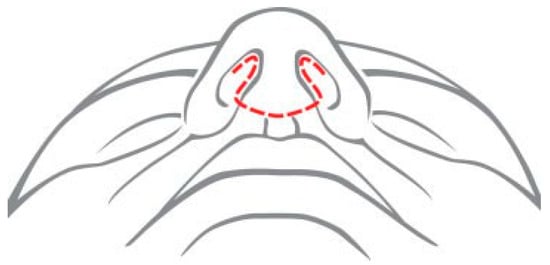

Figure 5.

Submucosal position of the foreign body in sagittal section. A, nasal bones; B, foreign body; C, nasal mucosa; D, upper lateral cartilage; E, lower lateral cartilage.

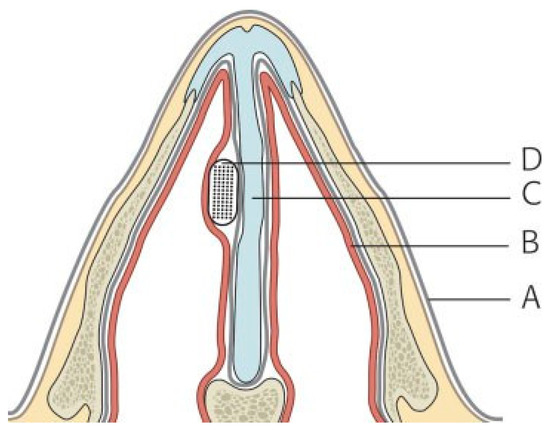

Figure 6.

Submucosal position of the foreign body in axial section. A, skin; B, nasal mucosa; C, nasal septum; D, foreign body.

Figure 7.

Illustration of the external rhinoplasty incision used.

Review of Management of NFBs

For most isolated NFBs, no diagnostic testing is indicated. With the exception of metallic or calcified objects, most NFBs are radiolucent. [1] When an alternate diagnosis (i.e., tumor, sinusitis) is being considered, imaging (i.e., CT scan) may be helpful. [1] On the other hand, if concern for an ingested or aspirated foreign body exists, radiography of the chest/abdomen should be performed.

Repeated attempts at NFB removal are likely to be successively more difficult, and the object may become more deeply lodged. Therefore, careful planning is important to maximize the likelihood of removal on the first attempt. Having the necessary instruments at the bedside is essential, as is the clinician’s knowledge of several techniques. In addition, emergency airway supplies should be readily available in the event that manipulation of the foreign body results in aspiration. Pharmacological vasoconstriction of the nasal mucosa can facilitate both examination and removal of an NFB. [1]

Most inanimate foreign bodies, if visualized well, can be removed easily through the anterior nares with the use of cupped forceps, hemostats, curved hooks, old metallic eustachian tube catheters, and suction. [2] This can be done either with no anesthetic or after spraying with a local topically acting anesthetic solution such as 4% lignocaine (lidocaine). Removal of a rounded object may be an arduous task because of difficulty in grasping foreign bodies of this shape. A curved hook is best suited for this job. [7] The hook is first passed behind the object, the tip rotated to rest just behind it, and then the foreign body is gradually drawn forward and out through the nose. [2,7] A nasal endoscope can aid in visualization of the foreign body when present in the posterior nasal cavity. Additionally, several suction methods have been described that aid in the removal of round foreign bodies. [8]

Plastic objects and vegetable matter may be difficult to extract because of their tendency to break into small pieces. The foreign body may be displaced backward and may even reach the nasopharynx with a risk of inhalation. [2,9] In a crying child, the foreign body while being removed from the nose can fall into the mouth with calamitous effects. Marked epistaxis may occur or a docile child may become terrified and require a general anesthetic, which might otherwise have been avoided. [10]

In cases in which removal of a foreign body is particularly difficult, several alternative procedures have been described. If the patient can cooperate, they can be instructed to take a deep breath through the mouth and then forcibly exhale through the nose. The attending doctor should occlude the uninvolved nostril during this procedure. [2,10] If the patient is not able to cooperate with this maneuver, forced mouth-to-mouth ventilation can be administered to the patient by the doctor, again occluding the uninvolved side. [2] Both the success rate and the incidence of complications associated with the above-mentioned procedures are not well reported in the literature. An additional method described by some authors is the use either of a Foley catheter or a Fogarty biliary catheter for removal of NFBs. [2,11,12] After ensuring that the balloon is intact, the catheter is passed into the nose beyond the foreign body. The balloon is then inflated with 0.5 mL of water. The catheter is withdrawn back through the nose, pulling the foreign body in front of the balloon. In rare cases, the only successful method of removing a NFB is to push the object posteriorly into the pharynx. [2,13] In these cases, a general anesthetic is required and endotracheal intubation performed to protect the airway. Additionally, epistaxis, which frequently accompanies the removal of NFBs, must be appropriately dealt with.

External rhinoplasty has been used to retrieve NFBs in cases where the object was lodged on the dorsum of the nose, underneath the skin in the subcutaneous tissues. Objects retrieved were glass particles and metallic foreign bodies. [5,6] This approach has been shown to be an effective and safe method for removal of foreign bodies in the external nose. It provides a good surgical field with better cosmetic outcomes than a conventional incision made directly over the foreign body. To our knowledge, this is the first report on the use of this approach to retrieve an intra-NFB.

Three-dimensional (3-D) stereotactic navigation systems have significantly increased patient safety and reduced surgical morbidity in the surgery of the nose and the paranasal sinuses. [14] This method is based upon a 3-D volume model of the patient’s skull generated by imaging procedures such as CT and magnetic resonance. Body points can be marked in the 3-D model by intraoperative correlation of model and patient using a volume digitizer. Real-time positioning of surgical instruments without visual control can be achieved. Currently, used radiological and intraoperative protocols have demonstrated a clinical accuracy of 1 to 2 mm. [14] This technique can be extremely helpful in cases like the one presented here and in cases where the NFB is close to vital structures.

Different techniques are employed for removal of animate foreign bodies. In the case of screw worms, larvae, and maggots, a weak solution of 25% chloroform or turpentine oil is instilled into the nasal spaces to kill the larvae. [2] This may have to be repeated two or three times a week for about 6 weeks until all larvae are killed. After each treatment, removal can be accomplished by blowing the nose if the patient is awake and by suction, irrigation, forceps, or curettage if the patient is asleep. [2] With Ascaris lumbricoides, manual or forceps extraction is utilized, thus avoiding the need for killing these worms before removal. The roundworms that become lodged in the nose, however, present only a part of the heavy intestinal infestation that has to be eradicated to prevent further nasal lodgment. Oral levamisole or mebendazole may be used for this. [2]

After successful removal of an NFB, careful examination of the involved nasal cavity as well as the other body orifices must be undertaken to exclude the presence of other unrecognized foreign bodies. Particular attention must be paid to the examination of the ear and sinuses on the involved side, as acute otitis media or sinusitis are commonly seen if the foreign body has been present for any length of time. Additionally, epistaxis, which frequently accompanies the removal of NFBs, must be appropriately dealt with.

Several important complications have been associated with the presence of an NFB. These include formation and development of rhinoliths, erosion into a contiguous structure, and producing infections in surrounding structures. Apart from acute sinusitis or otitis media, other infections reported include periorbital cellulitis, meningitis, acute epiglottitis, diphtheria, and tetanus. [2]

References

- Baluyot, S.T. Foreign bodies in the nasal cavity. In Otolaryngology; Paparella, M.M., Shumrick, D.A., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, 1980; 2009–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kalan, A.; Tariq, M. Foreign bodies in the nasal cavities: A comprehensive review of the aetiology, diagnostic pointers, and therapeutic measures. Postgrad Med J 2000, 76, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, A.H.; Balmain, A.R. Foreign bodies and nasal carriers of diphtheria. Lancet 1929. ii:977. [Google Scholar]

- DeWeese, D.D.; Saunders, A.H. Acute and chronic diseases of the nose. In Textbook of Otolaryngology; DeWeese, D.D., Saunders, A.H., Eds.; C.V. Mosby: St. Louis, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, C.H.; Jang, Y.J.; Kim, J.S.; Song, H.M. Removal of a metallic foreign body embedded in the external nose via open rhinoplasty approach. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008, 37, 1148–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Chaudhary, N. External rhinoplasty for dorsal swellings. Ind J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007, 59, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- McMaster, W.C. Removal of foreign body from the nose. JAMA 1970, 213, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.S. New device for foreign body removal. Laryngoscope 1984, 94, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walby, A.P. Foreign bodies in the ear or nose. In Scott-Brown’s Otolaryngology, 6th ed.; Kerr, A.G., Ed.; Butter-worth-Heinemann: Oxford, 1997; 6/14/1–6/14/6. [Google Scholar]

- Messervy, M. Forced expiration in the treatment of nasal foreign bodies. Practitioner 1973, 210, 242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.R. Fogarty catheter removal of nasal foreign bodies. Ann Emerg Med 1980, 9, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, L.N.; Chamberlain, J.W. Removal of foreign bodies from esophagus and nose with the use of a Foley catheter. Surgery 1972, 71, 918–921. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harner, S.G. Foreign bodies in the ear, nose, and throat. Postgrad Med 1975, 57, 82–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freysinger, W.; Gunkel, A.R.; Thumfart, W.F. Image-guided endoscopic ENT surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1997, 254, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2011 by the author. The Author(s) 2011.