Abstract

Study Design: Case series. Objective: To describe the assessment and surgical approach to dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) for patients with nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO) in the presence of orbital wall hardware. Methods: The pre-operative assessment, management and outcomes of two patients with secondary acquired NLDO following medial orbital wall fracture repair treated by nasal endoscopic DCR. Results: Anatomical and functional success was achieved in both cases at 6 weeks post operatively without disruption of the orbital plate. There was persistent success at 1 and 3 years’ post-operatively. Conclusions: Endoscopic DCR is a good option for the treatment of NLDO in patients with previous medial orbital wall fracture repair where the location of the plate may complicate the external approach.

Introduction

Naso-orbito-ethmoid (NOE) fractures can result in nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO). Early causes of post traumatic NLDO include soft tissue oedema, canalicular injury and bony impingement from facial fracture. Later causes include scarring, obstruction by primary fixation hardware and bony remodelling [,,].

Surgical management of NLDO following orbital wall trauma can be complicated by the presence of orbital implants, scarring, nasal adhesions and canalicular injury.

The external and nasal endoscopic approaches to dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) have comparable outcomes and can generally be used interchangeably. However, the presence of implants may complicate either approach depending on their location. There is a paucity of literature on DCR surgery for traumatic NLDO in the presence of orbital implants and no reports of the utilisation of the endoscopic approach to avoid encountering orbital plates in the region of the surgical field [,,,]. We report two cases of endoscopic DCR for traumatic acquired NLDO after medial orbital wall plating and explore the pre-operative patient and radiological assessment, surgical technique, and outcomes. Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series. Written informed consent for patient information and images to be published was provided by the patients.

Case 1

A 37 year old man presented with continuous left epiphora and sticky discharge around the medial canthus following surgery for a Le Fort type two fracture. The surgery, which required four titanium plates including a large orbital floor and medial orbital wall plate to the left orbit, occurred eight years earlier following a ski slope collision. On examination the patient had a left-sided one mm relative enophthalmos, mild lower lid retraction and a complete obstruction of the left nasolacrimal drainage system.

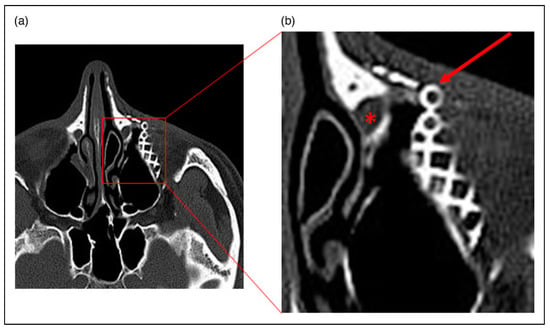

A preoperative CT scan demonstrated a titanium medial orbital wall and floor plates. The medial plate was located 8–10 mm medial to the lacrimal sac/nasolacrimal duct (NLD) and did not appear to violate the NLD (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

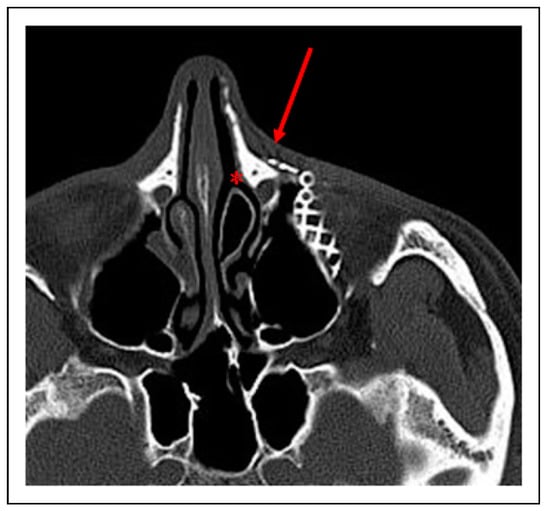

Figure 1.

Axial CT image of case 1 (a) showing the orbital floor plate (arrow) and the position of the nasolacrimal duct (*). (b) is an enlargement of the area indicated.

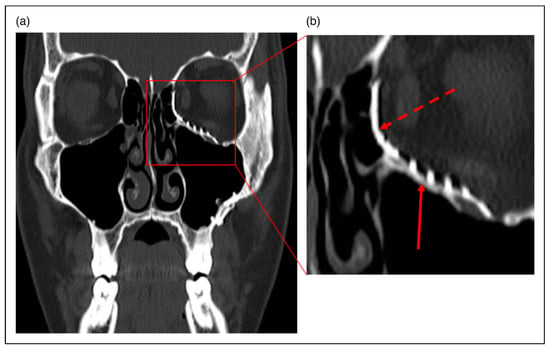

Figure 2.

Coronal CT image of case 1 (a) showing medial wall plate (dashed arrow) and inferior wall plate (solid arrow). (b) is an enlargement of the area indicated.

The patient underwent endoscopic endonasal DCR. The medial orbital metal plate was seen during the intraoperative removal of bone around the sac. The anterior flap was replaced over the metal plate and the procedure was otherwise uneventful. On review six weeks post-operatively the epiphora had resolved and nasal endoscopy demonstrated a patent ostium. The patient remains symptom free three years post-operatively.

Case 2

A 60 year old man presented with daily left eye watering and stickiness that had commenced immediately following reconstructive surgery with metal plates for baseball bat trauma to the left cheek, nose and orbit four years prior. Syringing of the nasolacrimal system found almost complete obstruction of the left nasolacrimal duct. A view of the middle turbinate was achieved on nasal endoscopy with no evidence of any bony obstructions.

A preoperative CT scan demonstrated extensive internal fixation of facial fractures with plate and screw fixation of the nasal bones and the left maxilla, including the inferior orbital rim (Figure 3). The metalwork did not breach the NLD although there was dilatation of the left nasolacrimal sac consistent with obstruction (Figure 4). Prior CT imaging from the time of the injury showed extensive involvement of the left nasolacrimal duct in the fractures, which were comminuted in nature (Figure 5).

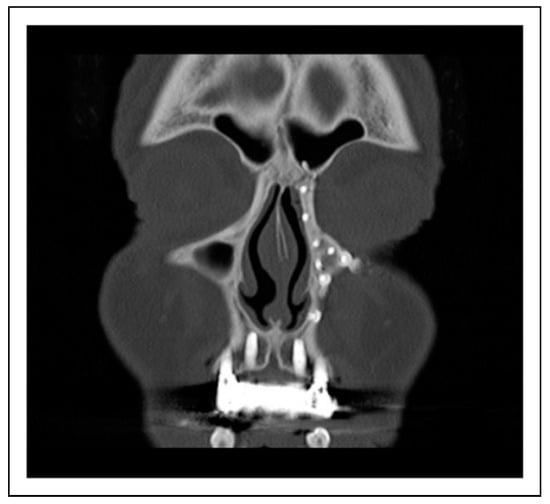

Figure 3.

Coronal CT Image of Case 2 showing extensive nasal and maxillary bone fixation hardware.

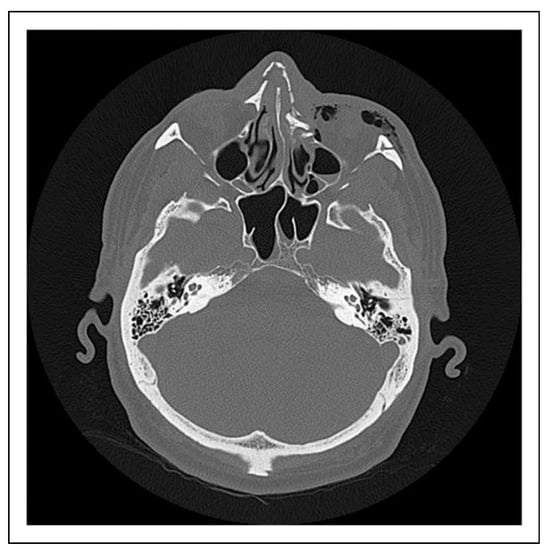

Figure 4.

Axial CT image of Case 2 showing dilatation of the left nasolacrimal sac (arrow) compared to the right with overlying nasal bone fixation hardware.

Figure 5.

Axial CT image of Case 2 taken at time of original injury showing multiple comminuted facial bone fractures, with involvement of the left nasolacrimal duct.

The patient underwent endonasal endoscopic DCR. The procedure was uneventful. At review six weeks postoperatively the epiphora had resolved and nasal endoscopy demonstrated a patent ostium. The patient remains symptom free one year post-operatively.

Discussion

Up to 47% of individuals suffering NOE develop epiphora, with up to 29% subsequently undergoing DCR for persistent NLDO []. Early, resolving epiphora may be caused by soft tissue inflammation, haematoma, or reactive hypersecretion due to pain. Chronic NLDO may be caused by the trauma or the reconstructive surgery [].

Development of lacrimal outflow obstruction following NOE trauma has been associated with certain radiographic fracture patterns, namely presence of nasomaxillary buttress displacement, avulsion of the lacrimal crest, bone fragments in the lacrimal sac fossa or in the nasolacrimal duct and greater than 50% compression of the nasolacrimal canal []. Early intervention for NOE fracture can reduce the risk of long term epiphora, perhaps by relocating or removing displaced bone and bone fragments that are compressing or distorting the NLD [,]. Reconstructive surgery can cause NLDO through several mechanisms: (1) the NLD or lacrimal sac can be directly traumatised during surgery (2) The NLD can be compressed or distorted by orbital plates and (3) maxillofacial screws can penetrate the NLD or lacrimal sac [].

Careful clinical and radiological preoperative assessment is vital for identifying the presence of traumatic NLDO and planning treatment. Patients with NLDO generally present with watering and discharge, with regurgitation occurring on applied pressure over the lacrimal sac []. Traumatic telecanthus has been identified as the most common associated ocular finding of traumatic NLDO []. CT imaging can guide surgical management, identify the presence of bony fractures compressing the nasolacrimal system and the position of any maxillofacial hardware. Plain CT is limited by its inability to accurately identify any nasolacrimal system soft tissue damage or specific point of obstruction related to trauma []. Dacryocystography (DCG) is useful in evaluating whether the lacrimal drainage system has been compromised by the trauma, but is unable to provide information regarding surrounding structures which may also be implicated. CT-DCG combines the benefits of both imaging techniques, and can therefore provide detailed anatomical information for surgical planning, which may be of great benefit in the context of trauma where anatomy may vary significantly from the norm []. Intraoperative navigation guidance with 3D CT-DCG shows promise for improved safety and precision in complex cases of secondary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction, allowing surgeons to observe in real time the position of hardware in relation to the nasolacrimal system, and new positions if moved intraoperatively [].

There is no consensus on the optimal timing of DCR for traumatic NLDO, although given that the majority of posttraumatic NLDO is caused by transient and reversible surrounding soft tissue oedema very early intervention is probably not indicated []. The timing does not impact upon outcomes, with similar results reported from intervention within 48 hours to that over two years post trauma [,,]. This is in contrast to the repair of NOE fracture, where delay is associated with higher rates of NLDO [,,].

Both external and endoscopic DCR approaches have been used with high success rates in the context of traumatic NLDO, but the choice must be tailored to the individual []. External DCR offers the opportunity to remove or revise orbital plates, and therefore may be the preferred option where maxillofacial hardware is thought to be responsible for the obstruction. It may also be easier to identify bony landmarks from the external approach if the anatomy has been seriously disturbed. The endoscopic approach avoids an incision through skin and orbicularis and will therefore avoid surgical plates that are positioned relatively anteriorly that may be encountered from the external approach, (Figure 6) as well as avoiding further skin and muscle trauma in an area that may already be scarred.

Figure 6.

Axial CT image of case 2 showing location of skin incision in external DCR (arrow) vs access achieved via endoscopic DCR (*).

However, this approach may be more greatly impacted by the loss or distortion by the trauma or reconstructive surgery of intranasal bony landmarks [].

The use of canalicular intubation and/or antimetabolite application is reported variably in the literature and although some authors advocate for these modifications routinely in all post-traumatic cases of NLDO [], in our cases successful surgical outcomes were achieved without this.

Although limited in number, our cases demonstrate that endoscopic endonasal DCR may be a preferable approach for the primary treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction in the presence of maxillofacial hardware from medial wall reconstructive surgery. Caution should however be taken in careful pre-operative assessment including analysis of imaging, to identify the location of any orbital hardware and this or other likely causative mechanism, so that surgical technique can be adjusted accordingly.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Shim, W.S.; Cho, M.J.; Kim, J.; Jung, H.J. Epiphora after nasolacrimal duct fracture in patients with midfacial trauma: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltim.) 2019, 98, e18120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, F.; Karaca, E.E.; Konuk, O. Surgical management of traumatic nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2016, 26, 517–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.M.; Kalin-Hajdu, E.; Idowu, O.O.; Vagefi, M.R.; Kersten, R.C. Nasolacrimal obstruction following the placement of maxillofacial hardware. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Reconstr. 2020, 13, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chon, B.H.; Zhang, R.; Bardenstein, D.S.; Coffey, M.; Collins, A.C. Bloody epiphora (hemolacria) years after repair of orbital floor fracture. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017, 33, e118–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriello, J.A.; Fiore, P.M.; Kotch, M. Dacryocystitis. Late complication of orbital floor fracture repair with implant. Ophthalmology. 1987, 94, 248–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohn, R.; Romano, P.E.; Puklin, J.E. Lacrimal obstruction after migration of orbital floor implant. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976, 82, 934–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruss, J.S.; Hurwitz, J.J.; Nik, N.A.; Kassel, E.E. The pattern and incidence of nasolacrimal injury in naso-orbital-ethmoid fractures: The role of delayed assessment and dacryocystorhinostomy. Br J Plast Surg. 1985, 38, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becelli, R.; Renzi, G.; Mannino, G.; Cerulli, G.; Iannetti, G. Posttraumatic obstruction of lacrimal pathways: A retrospective analysis of 58 consecutive naso-orbitoethmoid fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2004, 15, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, R.K.; Hartman, M.J.; Lucarelli, M.J.; Leverson, G.; Afifi, A.M.; Gentry, L.R. Nasolacrimal system fractures: A description of radiologic findings and associated outcomes. Ann Plast Surg. 2015, 75, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, B.; Dhobekar, M. Traumatic nasolacrimal duct obstruction: Clinical profile, management, and outcome. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2013, 23, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raslan, O.A.; Ozturk, A.; Pham, N.; Chang, J.; Strong, E.B.; Bobinski, M. A comprehensive review of cross-sectional imaging of the nasolacrimal drainage apparatus: What radiologists need to know. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019, 213, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitag, S.K.; Woog, J.J.; Kousoubris, P.D.; Curtin, H.D. Helical computed tomographic dacryocystography with threedimensional reconstruction: A new view of the lacrimal drainage system. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002, 18, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.J.; Singh, S.; Naik, M.N.; Kaliki, S.; Dave, T.V. Interactive navigation-guided ophthalmic plastic surgery: The utility of 3D CT-DCG-guided dacryolocalization in secondary acquired lacrimal duct obstructions. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017, 11, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoshani, Y.; Samet, N.; Ardekian, L.; Taicher, S. Nasolacrimal duct injury after Le Fort I osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994, 52, 406–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drnovsek-Olup, B.; Beltram, M. Trauma of the lacrimal drainage system: Retrospective study of 32 patients. Croat Med J. 2004, 45, 292–294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.J.; Gupta, H.; Honavar, S.G.; Naik, M.N. Acquired nasolacrimal duct obstructions secondary to naso-orbitoethmoidal fractures: Patterns and outcomes. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012, 28, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, J.K.; Yun, P.Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, J.H. Dacryolith after a Le Fort I fracture: Case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020, 49, 1199–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uraloğlu, M.; Erkin Unlü, R.; Ortak, T.; Sensöz, O. Delayed assessment of the nasolacrimal system at naso-orbito-ethmoid fractures and a modified technique of dacryocystorhinostomy. J Craniofac Surg. 2006, 17, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keren, S.; Abergel, A.; Manor, A.; et al. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: Reasons for failure. Eye. 2020, 34, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawaheer, L.; MacEwen, C.J.; Anijeet, D. Endonasal versus external dacryocystorhinostomy for nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017, 2, CD007097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2024 by the author. The Author(s) 2024.