Self-induced masticatory trauma is an unfortunate complication of a variety of neurologic disorders, including epileptic seizures, cerebral palsy, mental retardation, psychiatric disease, and brain trauma, in addition to other described etiologies (

Figure 1). While single or occasional occurrences of tongue biting are relatively benign, recurrent self-injury can pose major issues and predispose a patient to chronic, severe complications.[

1] To prevent the difficulties associated with ongoing trauma to the tongue, steps must be taken to protect individuals from chronic self-injurious behavior.

Case Example

A 19-year-old otherwise healthy male was brought to our institution after being involved in a motor vehicle accident sustaining intraparenchymal hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, diffuse axonal injury, left zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) fracture, and left anterior table frontal sinus fracture. A multidisciplinary approach to his care included serial neurologic exams with initial intracranial pressure monitoring catheter which was removed shortly thereafter after normal pressures. Neurosurgical recommendations included refraining from sedation to allow serial neurologic exams. The Craniomaxillofacial Trauma Service was consulted for management of his facial fractures. The patient’s left ZMC complex fracture was repaired with open reduction and internal fixation via an intraoral approach. Within the first postoperative day, the patient was found to engage in persistent tonguebiting not amenableto bite-block placement due to his recent fracture repair, along with poor response to verbal commands secondary to his neurologic status.

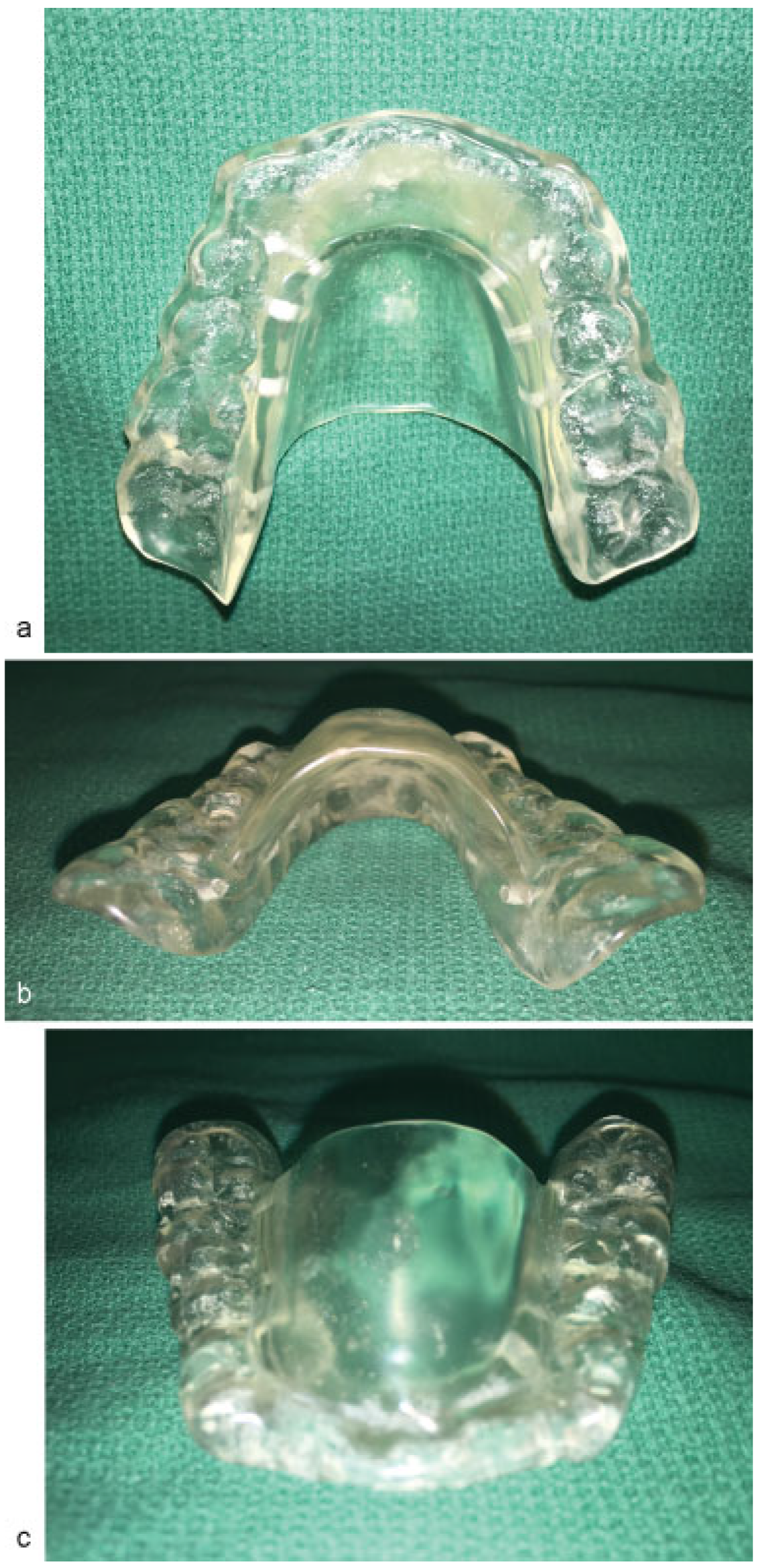

With the full-thickness nature of his self-induced masticatory trauma to the tongue, lingual repair along with protection was required. Maxillary and mandibular dental impressions were obtained utilizing polyvinylsiloxane impression material (Reprosil; Dentsply Sirona, York, PA) for the fabrication of an oral appliance to prevent further masticatory trauma to the tongue (

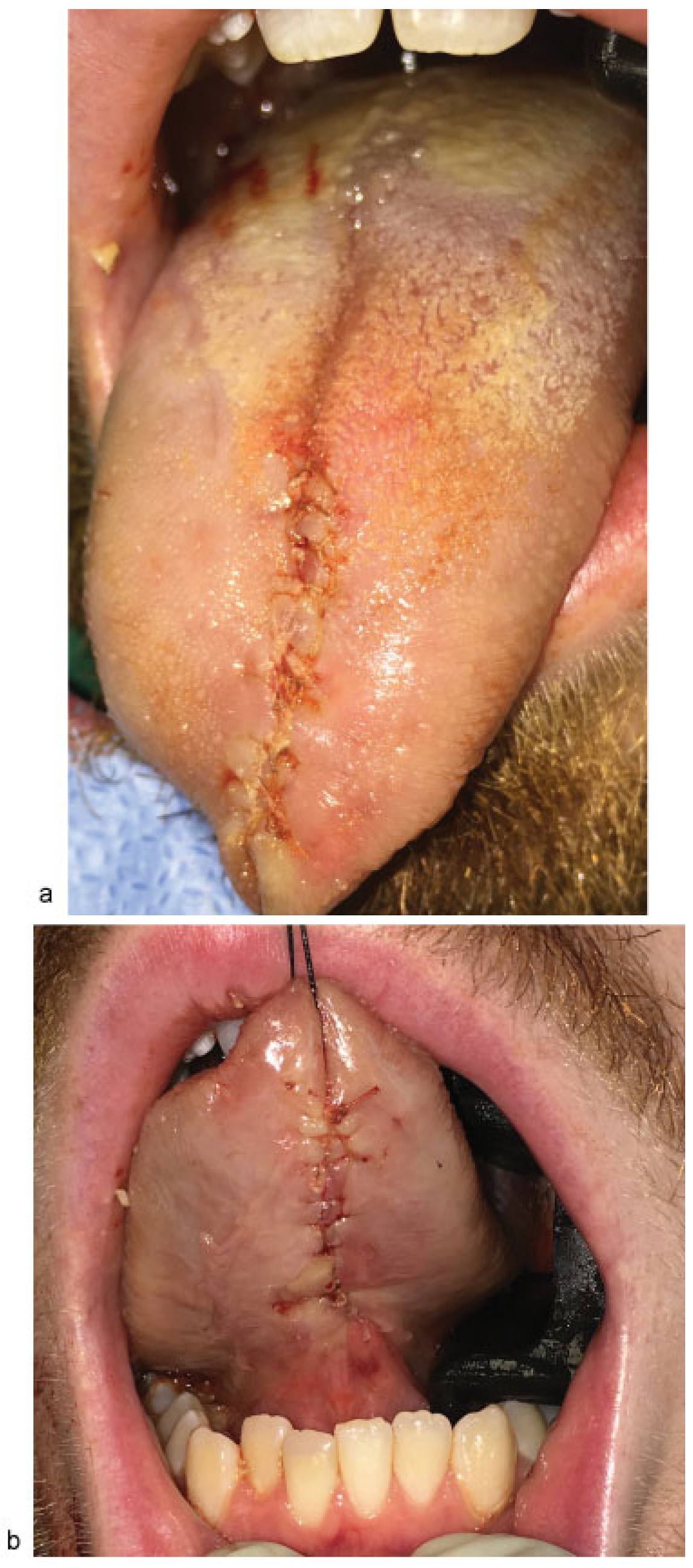

Figure 2a–c). The dental impressions were used to create stone models of the dentition, which were then mounted on a dental articulator to exactly recreate the patient’s occlusal relationship. The oral appliance was fabricated with Dentsply Orthodontic Resin (Dentsply Sirona) with an omega-shaped flange, allowing the tongue to lay passively within the oral cavity, but negated the need for immobilization of the jaws. The orthotic was fabricated to adapt exactly to the mandibular dentition, and the interface with the maxillary dentition was adjusted on the acrylic resin to allow for uniform masticatory force distribution and occlusal relationship. Fabrication of the appliance was performed within 36 hours at a local commercial dental laboratory. During this interval, the patient’s mandible was immobilized to prevent further masticatory lingual trauma. The patient was then taken again to the operative room for repair of his lingual trauma, which was noted to be a full-thickness injury, with 10-cm aggregate involvement of the ventral and dorsal surfaces of the tongue (

Figure 3). Repair involved placement of interrupted and running 3–0 Vicryl sutures to establish the normal shape and contour of the tongue (

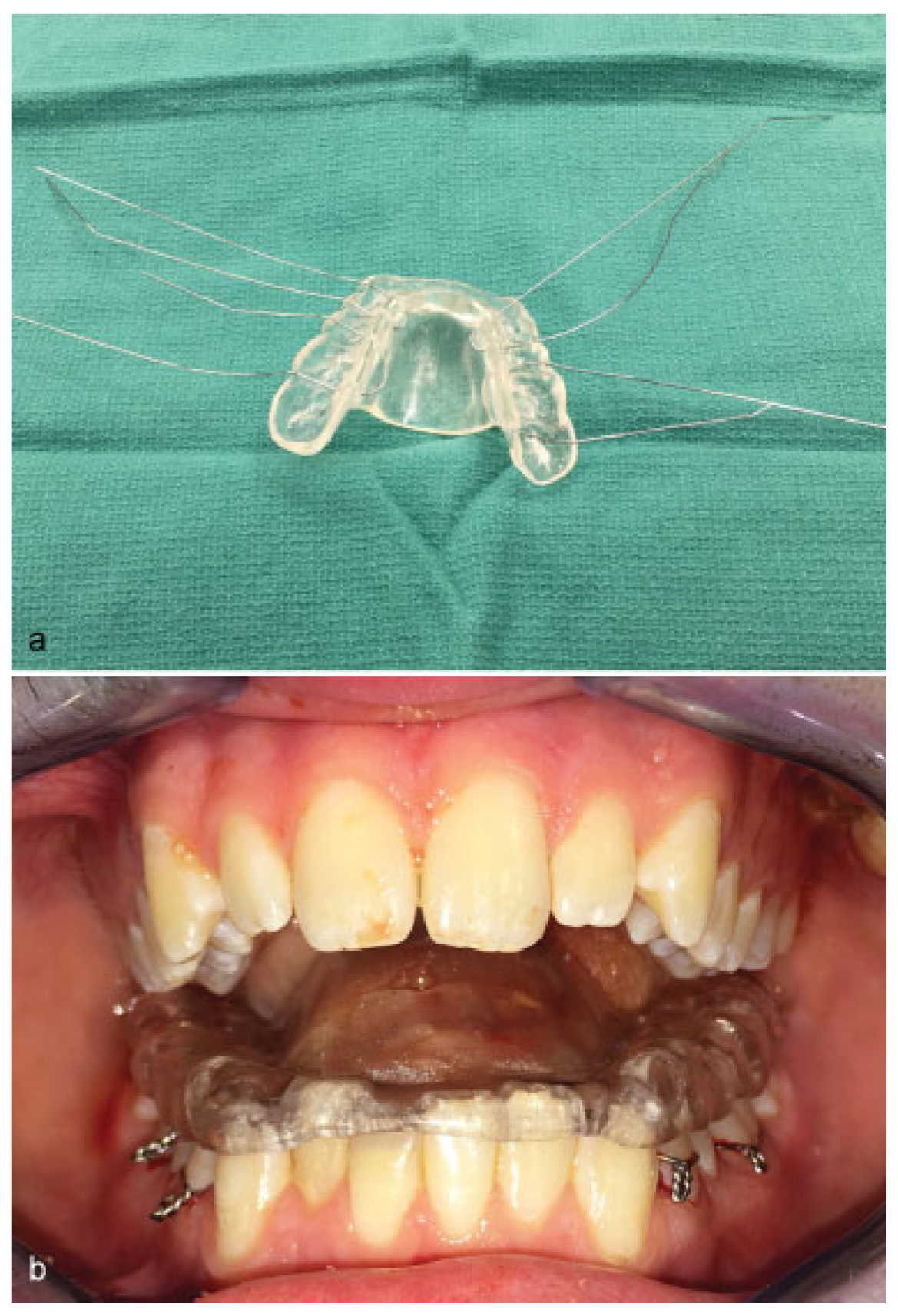

Figure 4a, b). The previously fabricated orthotic was adapted to the mandibular dentition and secured with interrupted 24-gauge stainless steel surgical wires, which had been preloaded on the back table in the operating room to facilitate ease of placement, and passage of the surgical wires through the dental embrasures of multiple mandibular teeth (

Figure 5a, b). The omega-shaped flange did not prevent closure of the mouth, but mechanically prevented tongue protrusion and masticatory trauma. The patient’s neurologic status improved in the postoperative course and the orthotic was then removed on postoperative day 7 with evidence of healed lingual repair.

Discussion

Self-induced trauma to the tongue, and other oral structures, is most classically associated with epileptic seizures, but has also been reported in patients with Lesch-Nyan syndrome, cerebral palsy, congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis, mental retardation, psychiatric disease, meningitis, and brain trauma.[

4,

5,

6,

7] Furthermore, self-injury is sometimes a premeditated action, functioning as an attention-seeking method to either manipulate or a means to seek help.[

2,

6,

8,

9] Accordingly, a distinction can be made between organic causes, in which the individual acts unconsciously, and functional injury that manifests from deliberate provocation.[

2]

Chronic tongue biting causes soft-tissue, vascular, and lymphatic injuries that lead to edema and predispose the tongue to further injury.[

1] As a result, patients can suffer from loss of tissue and superinfection.[

6,

10] Severe trauma resulting in lingual artery hematoma can lead to traumatic macroglossia and airway compromise.[

11,

12,

13,

14]

A review of the current literature illustrates several important concepts in the management of oral lesions. Patients suspected of or at risk for traumatic injury to the tongue should undergo repeat examinations. Both surfaces of the tongue should be assessed for evidence of lacerations, hematoma, and swelling; the oral cavity for pieces of teeth, tissue, and foreign bodies; and thejaw for range of motion.[

11,

15,

16] This inspection allows a provider to determine both the degree of injury and the potential need for airway management. Severe macroglossia from hematoma can make laryngoscopy nearly impossible, potentially necessitating blind intubation or tracheostomy. Steroids and the aggressive use of muscle relaxants to help reduce airway obstruction have been described in the literature with mixed results.[

12,

13,

17] Thus, it is vital to secure an airway as soon as possible before massive swelling occurs.[

11,

14,

17]

Once an airway is secured, attention can turn to the injuries themselves. To prevent infection, wounds should be debrided and irrigated with normal saline to remove necrotic material and foreign bodies.[

16,

18] Although some texts suggest the use of antibiotics, the usefulness of prophylactic treatment in oral lacerations is inconclusive.[

16,

18,

19] Whether to use antibiotics, therefore, can be based on the presence of heavy contamination, delayed wound debridement, and/or immunocompromise.[

18]

Due to the rich vascular supply of the oropharynx, tongue and oral mucosal wounds tend to heal quickly and do not always necessitate closure. Lacerations that are smaller than 2 cmand do not present with difficulty in obtaining hemostasis may not need suturing if they are in good approximation.[

19] Larger injuries, deep lacerations, or penetrating wounds should be closed. Deep wounds should be closed in layers with chromic gut suture in the muscle to prevent hematoma, and 4–0 Vicryl in the superficial layers.[

16] For penetrating wounds, both the dorsal and ventral aspects should be closed. Loss of tissue from the lateral aspect or tip of the tongue will usually resolve due to tongue hypertrophy. In a patient with coagulopathy, it may be advisable to suture small lacerations due to delayed healing.[

19]

To prevent the complications associated with ongoing trauma to the tongue, steps must be taken to protect individuals from chronic self-injurious behavior. A variety of treatment modalities have been described in the literature, and can be broadly organized into four categories: psychological treatment, pharmacologic treatment, intra-oral devices, and surgery.[

2,

8]

For cases of functional self-injury, psychological treatment should be considered in the initial phase of treatment. Psychological evaluation can determine the cause of a patient’s selfinjury and help the development of a therapeutic approach.[

2] Approaches include positive and negative reinforcement of behavior, overcorrection, and distraction techniques.[

7] Although behavioral therapy may have limited effectiveness in isolation, particularly in cases where the patients are unable to stop their habits, some cases have responded favorably to therapy.[

2] Moreover, behavioral therapy is noninvasive and lacks the risks associated with medication and surgery.[

9]

Pharmacological treatments forbiting-relatedinjuryinclude tricyclic antidepressants, neurotransmitter agonists/antagonists, anticonvulsants, and botulinum toxin injections. Some theories on self-mutilation posit that self-injurious behavior arises from dysregulation of the opiatergic, dopaminergic, and/or serotonergic systems.[

17,

20] Accordingly, drugs to compensate for potential neurotransmitter deficits have been trialed in patients, such as dopamine receptor antagonist (haloperidol and fluphenazine), serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluoxetine and trazodone), and the anticonvulsant (carbamazepine).[

8,

9,

20] However, none of these approaches have yielded success at a generalizable scale, and their use often has an excessively sedative effect on patients.[

2]

On the other hand, the use of botulinum toxin A (BTX-A) has shown promising results as a safe and effective treatment for self-induced trauma.[

20] Although not fully understood, BTX-A is thought to function through several mechanisms to cause muscular relaxation. It cleaves SNARE proteins at the terminal membrane of α-motor neurons, preventing acetylcholine from binding to receptors at the neuromuscular junction, and may decrease the release of substance P from dorsal root ganglia, resulting in decreased muscle strength and less frequent action.[

21] Randomized control studies by Lee et al and Guarda-Nardini et al suggested that injection of BTX-A directly into the masseter muscle is an effective and safe treatment to treat involuntary bruxism.[

21,

22,

23,

24] Case reports have shown similar effectiveness in patients with bruxism secondary to brain injury from motor vehicle accidents and neurological disorders.[

2,

21,

25] However, further study is needed to elucidate the mechanism and safety of BTX-A injections.[

2,

20,

21]

To directly prevent injury, intraoral devices can be used, including mouth guards, splints, lip bumpers, and combinations thereof. These prosthetics serve to suppress biting behavior and act as physical barriers against injury, providing better protection and control according to some clinicians.[

2,

3] While potentially obviating the need for invasive procedures and surgery, they carry with them the potential adverse effects of infection if not properly maintained and cleaned.[

2] Mouth guards are the most commonly used intraoral device. Stock mouth guards are durable, easy to use, and inexpensive, but loose and limited in their potential for modification.[

26] As such, custom-made mouth protectors such as acrylic splints are considered more effective owing to their customizability, stability, and retention.[

3,

26] Splints can be affixed in the mouth using bands, wire loops, or cement, creating a barrier to removal. Any dental prosthetic used shouldbe able tomaintain separation between the teeth and oral tissue without causing further damage to the mouth or interfering with the function of the jaw. Furthermore, they should be able to be cleaned and tolerate normal intraoral forces.[

2] Impressions should be taken to customize the device for each individual’s anatomy and the degree of affixation can be determined based on the cooperability of the patient. Generally, the oral appliances that are secured within the oral cavity, and particularly devices such as the type described in this article, are best utilized in the comatose or semicomatose patient population due to the potential for the appliance to stimulate a gag-reflex or agitation secondary to the inability to fully move the tongue. Removable devices allow for better hygiene, but necessitate a patient’s collaboration with therapy.[

1,

3,

20] Proper use of these devices can allow healing of lacerations or ulcerated lesions within a matter of weeks and prevent long-term injury.[

1,

3,

10,

20,

26,

27,

28] Adequate follow-up is necessary to monitor healing and assess for new lesions, particularly in young patients whose dentition is changing.[

2]

In severe and refractory cases, surgery can be utilized to prevent chronic injury. The extraction of all dentition is an extreme, but effective, method to prevent mutilation. As an alternative, some surgeons have created open bites in patients to prevent contact and preserve tissue, but this treatment subjects the patients to an orthognathic surgical procedure which may result in additional complications in osseous healing due to chronic nutritional deficits or the repetitive muscular function commonly seen in neurologically impaired patients.[

2,

20,

26]

Although there is no standardized consensus for the treatment of tongue biting patients, it is reasonable to employ an intraoral prosthetic to allow for lesion healing and prevent future trauma. Alone or in combination with psychological therapy for functional causes and/or pharmacological treatment, these devices can significantly improve the quality of life of patients suffering from self-induced tongue injury. As compared with other forms of appliances mentioned in the literature, we feel the device described in our article alleviates the issues associated with a unilateral or bilateral posterior mouth prop appliances and helps maintain a functional occlusal relationship, which prevents potential dentoalveolar migration or alterations in the occlusal plane associated with potential long-term use, and still allows for easy access to the oral cavity for hygiene and maintenance of the dentition.[

20,

26,

27,

28]