Abstract

Care for patients with cleft lip and palate is best managed by a craniofacial team consisting of a variety of specialists, including surgeons, who are generally plastic surgeons or otolaryngologists trained in the United States. The goal of this study was to compare the surgical approaches and management algorithms of cleft lip, cleft palate, and nasal reconstruction between plastic surgeons and otolaryngologists. We performed a retrospective analysis of the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Pediatric database between 2012 and 2014 to identify patients undergoing primary repair of cleft lip, cleft palate, and associated rhinoplasty. Two cohorts based on primary specialty, plastic surgeons and otolaryngologists, were compared in relation to patient characteristics, 30-day postoperative outcomes, procedure type, and intraoperative variables. Plastic surgeons performed the majority of surgical repairs, with 85.5% (n = 1,472) of cleft lip, 79.3% (n = 2,179) of cleft palate, and 87.9% (n = 465) of rhinoplasty procedures. There was no difference in the age of primary cleft lip repair or rhinoplasty. However, plastic surgeons performed primary cleft palate repair earlier than otolaryngologists (p = 0.03). Procedure type varied between the specialties. In rhinoplasty, otolaryngologists were more likely to use septal or ear cartilage, whereas plastic surgeons preferred rib cartilage. Results were similar, with no statistically significant difference in terms of mortality, reoperation, readmission, or complications. Significant variation exists in the treatment of cleft lip and palate based on specialty service with regard to procedure timing and type. However, short-term rates of mortality, wound occurrence, reoperation, readmission, and surgical or medical complications remain similar.

Cleft lip and palate are common congenital craniofacial anomalies, affecting ~approximately 14.5 per 10,000 live births per year, and occurring either sporadically or in association with certain genetic syndromes.[,] Surgical management is initially targeted at repairing the cleft lip followed by the palate with varied approaches depending on unilateral versus bilateral and complete versus incomplete pathologies.[] Subsequent procedures later in the child’s development address maxillary, alveolar, and nasal deformities.[]

Care is best managed by a dedicated team with a diverse array of specialists providing longitudinal care from the time of diagnosis until adulthood. As per the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association (ACPA) guidelines, this craniofacial team should consist of nurses, social workers, psychologists, dentists, pediatricians, speech pathologists, and surgeons.[] While the ACPA does not recommend a specific surgical specialty in the treatment of cleft lip and palate, surgeons are generally plastic surgery, otolaryngology, or oral and maxillofacial trained.[,,]

Multiple treatment protocols exist, but optimal technique and timing are subject to ongoing debate. The goal of this study was to compare the surgical approaches and management patterns of cleft lip and palate between plastic surgeons and otolaryngologists using the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in Pediatric (ACS-NSQIP Pediatric) database.

Methods

Data Source

We obtained the Participant Use Data Files for 2012–2014 from the ACS-NSQIP Pediatric. This database is composed of data regarding preoperative comorbidities, intraoperative variables, and 30-day postoperative morbidity outcomes in surgeries performed on patients younger than 18 years from participating institutions. The purpose is to benchmark and improve the quality of surgical care. The details for data collection methods are available elsewhere.[] In short, surgical clinical reviewers at participating institutions collect data through a systematic sampling method that selects cases in 8-day cycles from different days of the week throughout the year. This study was approved by our institutional review board and conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient information was de-identified in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).

We performed a retrospective analysis of the database to obtain data on all cases with primary cleft lip repair, primary cleft palate repair, or rhinoplasty for cleft patients between 2012 and 2014. Patients were identified by ICD9 codes and procedure types were specified by the American Medical Association Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Primary cleft lip repair was defined by CPT codes 40700 through 40702. Primary cleft palate repair was defined as 42200 and 42205. Cleft rhinoplasty was defined as CPT codes 30460 and 30462. Given the lack of representation of oral and maxillofacial surgeons in the NSQIP Pediatric database, this specialty was not included in the analysis. Patients were subdivided into two cohorts based on primary specialty: plastic surgery and otolaryngology.

Information regarding variables and their definitions can be found at the program’s Web site (http://www.pediatric. acsnsqip.org/). Demographic data were compared between the two cohorts as were intraoperative variables. Composite variables were created to assist with analysis of outcomes. Surgical complications were defined as wound complication or infection, occurrence of bleeding/transfusion, and graft/ implant failure. Medical complications encompassed respiratory, genitourinary, and central nervous system endpoints in addition to sepsis and cardiac arrest.

Respiratory history included ventilator use, pneumonia, asthma, cystic fibrosis, history of chronic lung disease, oxygen supplementation, tracheostomy, and structural pulmonary abnormality. Gastrointestinal history included esophageal/gastric/intestinal disease or liver/biliary/pancreatic disease. Cardiac history included history of cardiac disease or previous cardiac surgery. Neurologic history included coma, cerebrovascular accident, tumor, impaired cognitive status, seizure, cerebral palsy, neuromuscular disorder, or structural central nervous system abnormality. Immune history included organ transplant, bone marrow transplant, steroid use, or immune disorder. Nutritional history included history of weight loss, diabetes, or nutritional support. Hematologic history included bleeding disorder or hematologic disorder.

Statistical analysis was performed on descriptive variables as well as outcomes. Univariate analysis compared the two cohorts with perioperative risk factors and patient comorbidities. Chi-square and t-tests were used to perform univariate analysis on categorical and continuous variables, respectively. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

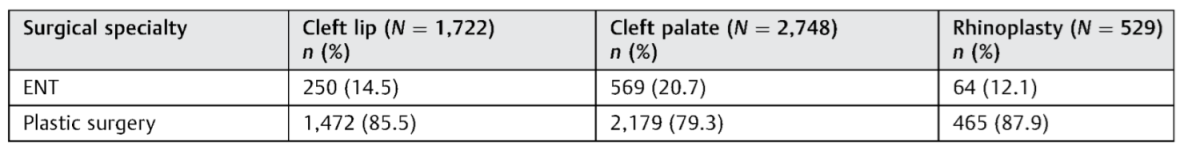

A total of 4,999 cases were identified for analysis, including 1,722 cleft lip repairs, 2,748 cleft palate repairs, and 529 cleft rhinoplasties. Plastic surgeons performed the majority of surgical repairs, including 85.5% (n = 1,472) of cleft lip, 79.3% (n = 2,179) of cleft palate, and 87.9% (n = 465) of rhinoplasty procedures (►Table 1).

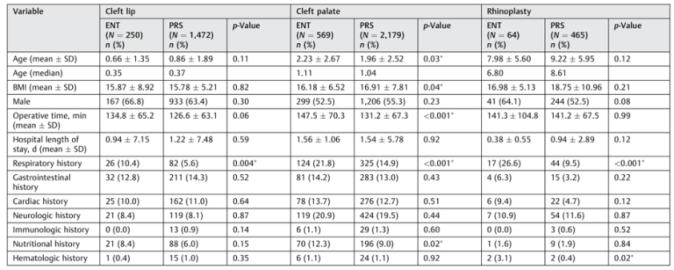

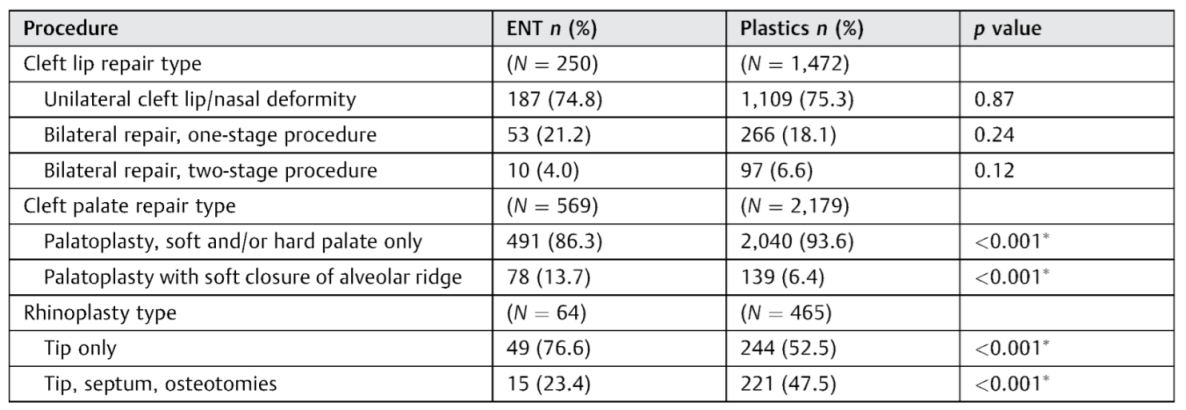

There was no statistically significant difference in age at the time of rhinoplasty (►Table 2). Primary repair of cleft lip occurred at similar ages between plastic surgeons and otolaryngologists across cleft lip (0.86 and 0.66 years, respectively) and rhinoplasty procedures (9.22 and 7.98 years, respectively) with no statistically significant difference. However, primary cleft palate repair was performed on average earlier under plastic surgery care (1.96 vs. 2.23 years, respectively, p = 0.03). The distribution of cleft lip repair type did not vary significantly (►Table 3). However, in cleft palate repair, plastic surgeons demonstrated preference for palatoplasty of the soft and/or hard palate only, whereas otolaryngologists demonstrated preference for palatoplasty with soft closure of the alveolar ridge (p < 0.001). Otolaryngologists demonstrated preference for tip-only rhinoplasty, whereas plastic surgeons performed a larger number of tip rhinoplasties with septum and osteotomy repair in comparison (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Distribution by surgical specialty.

Table 1.

Distribution by surgical specialty.

|

Table 2.

Demographic and perioperative characteristics.

Table 2.

Demographic and perioperative characteristics.

|

Table 3.

Procedure type by surgical specialty.

Table 3.

Procedure type by surgical specialty.

|

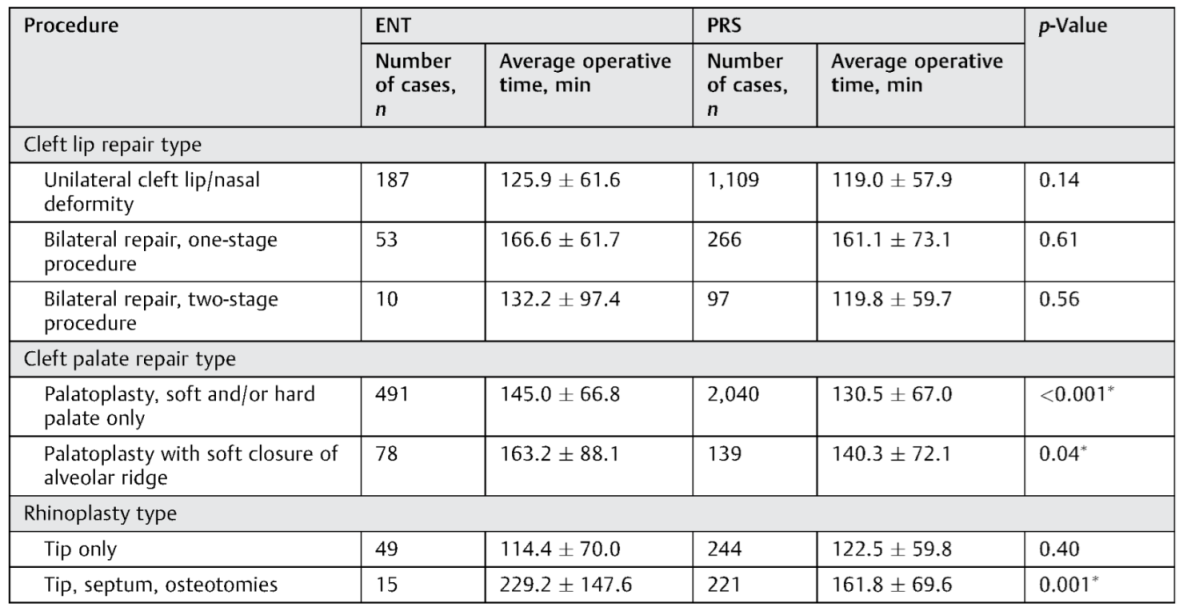

Operative time was on average longer with otolaryngologists for cleft palate repair (p < 0.001) than with cleft lip repair or rhinoplasty procedures. When differentiating the operative time by procedure type (►Table 4), statistical significance was reached only on palatoplasty with soft and/or hard palate repair (p < 0.001*), palatoplasty with soft closure of alveolar ridge (p = 0.040), and tip rhino-plasty with septum repair and osteotomies (p = 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in terms of average length of stay in the hospital across any procedure type.

Preoperative morbidities are also demonstrated in ►Table 2. History of respiratory problems in cleft lip repair was significantly more common in the otolaryngology cohort (p = 0.004). Histories of respiratory (p < 0.001) and nutritional problems (p = 0.02) were also more common in the otolaryngology cohort for patients undergoing cleft palate repair. Under rhinoplasty procedures, patients operated on by otolaryngologists were more likely to have either respiratory (p < 0.001) or hematologic (p = 0.02).

Table 4.

Operative time by procedure type.

Table 4.

Operative time by procedure type.

|

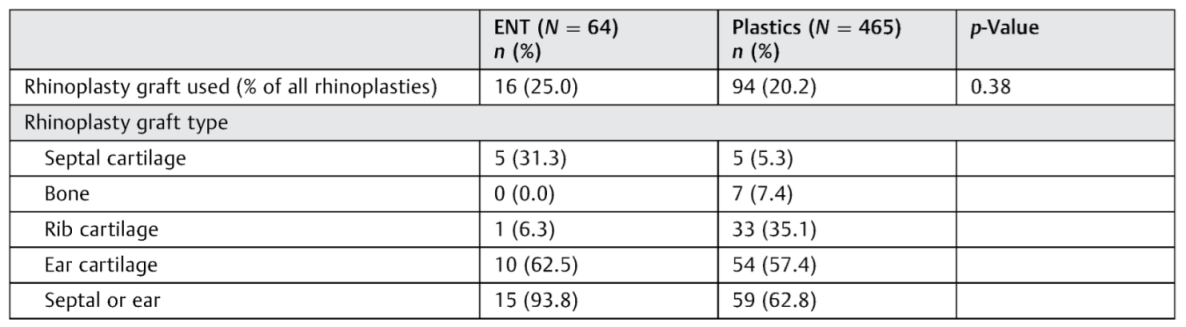

Table 5.

Rhinoplasty grafts.

Table 5.

Rhinoplasty grafts.

|

Note: Combinations of graft type are possible; therefore, total may surpass 100%.

Both specialties used grafts during rhinoplasty at similar rates (►Table 5). However, otolaryngologists were more likely to use septal or ear cartilage, whereas plastic surgeons preferred rib cartilage. Results were similar, with no statistically significant difference in terms of mortality, unexpected reoperation, readmission, medical complications, or surgical complications (►Table 6).

Discussion

Cleft lip and palate place burdens on both patients and the health care system, leading to reduced quality of life, prolonged treatment processes, and increased costs.[] Adequate treatment is essential to restore and maintain proper function of sinuses for respiration, velopharyngeal function for speech and sound, oropharyngeal musculature for swallowing, and facial bones and musculature for social interactions.[]

Early assessment is imperative in the management planning and facilitates effective treatment.[] Surgical repair of cleft lips is generally undertaken at ~approximately 3 months of age. Cleft palate is optimally treated at close to 12 months of age. ACPA guidelines suggest cleft lip repair within the first 12 months of life, and cleft palate repair within the first 18 months of life and preferably earlier when possible.[] Timing is critical, as performing palate closure very early carries airway and maxillary growth implications,[] whereas later closures may lead to inhibited speech development.[]

In terms of patient’s age, primary cleft lip repair occurred within the recommended time frame in both otolaryngology and plastic surgery cohorts at averages of 0.66 years (7.9 months) and 0.86 years (10.3 months), respectively, and medians of 0.35 years (4.2 months) and 0.37 years (4.4 months), respectively. These age differences in primary cleft lip repair did not achieve statistical significance. Primary cleft palate repairs did reach statistical significance and were performed at averages of 2.23 and 1.96 years in the otolaryngology and plastic surgery cohorts, respectively, and medians of 1.11 and 1.04 years, respectively. Many patients underwent repairs later in life, which may be due to access issues leading to delayed presentation to the health care system, socioeconomic factors,[] patient or family preferences, or comorbidities.

Optimal timing for nasal deformities is less well established. Although final rhinoplasty and nasal septal correction have traditionally been recommended after completion of nasal growth, earlier intervention may be indicated for reasons of airway problems or nasal tip deformity.[] Al- though nasal surgery with repositioning of the lower lateral cartilage is common at the time of initial lip repair, definitive rhinoplasty procedures are generally performed in adolescence after maturation of the facial skeleton, and it is usually one of the final operations in the treatment process.[] Both specialties performed the operation at similar ages, with otolaryngologists and plastic surgeons performing rhinoplasty at an average of 7.98 and 9.22 years, respectively, and medians of 6.80 and 8.61 years, respectively. These differences did not reach statistical significance.

The otolaryngology cohort demonstrated a greater proportion of patients with comorbidities across all procedure types. In cleft lip repair, statistical significance was reached with respiratory comorbidities. With cleft palate repair, the otolaryngology cohort had a greater proportion of respiratory and nutritional comorbidities. Finally, in rhinoplasty procedures, respiratory and hematologic comorbidities were more common under otolaryngologists. Respiratory comorbidities were common with otolaryngologists in all three procedure types, which may be reflective of patients already being under otolaryngology care due to preexisting respiratory illnesses. Although patients treated by otolaryngologists had greater proportions of comorbidities, there was no statistically significant difference in average length of hospital stay. This variation in comorbidity rates may contribute to observed differences between the cohorts, including delayed timing of palatoplasty and prolonged operative time.

Historically, plastic surgeons have more frequently performed surgical procedures on cleft patients. Our data are consistent with this notion, with plastic surgeons performing between 79 and 88% of cleft lip, cleft palate, and rhinoplasty procedures. Specific procedure types demonstrated significant variation between the cohorts in procedures performed and operative time. The distribution of cleft lip repairs was similar. However, otolaryngologists demonstrated preference for tip-only rhinoplasty procedures, whereas plastic surgeons were more likely to include septum repair and osteotomies. Septoplasty and bone osteotomies are commonly used in these operations to optimize results.[] Both groups used grafts in rhinoplasty at similar rates. However, otolaryngologists more commonly used ear cartilage and septal cartilage, while plastic surgeons more often used rib cartilage. Almost all of the grafts used by otolaryngologists were of septum or ear in origin (93.8%), compared with 62.8% in the plastic surgery cohort. This likely reflects differences in training backgrounds, as otolaryngologists specialize primarily in the head and neck region, thus influencing their preferred graft types, whereas plastic surgeons operate in multiple regions of the body. However, given the nature of our data and variations in training, a definitive conclusion regarding the demonstrated preference cannot be drawn.

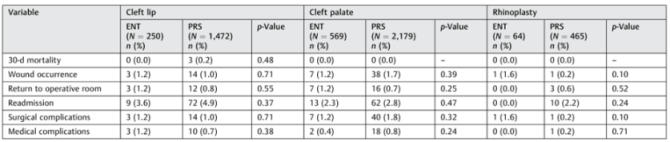

Table 6.

Postoperative outcomes.

Table 6.

Postoperative outcomes.

|

Notes: Surgical complications were defined as wound complication or infection, occurrence of bleeding/transfusion, and graft/implant failure. Medical complications encompassed respiratory, genitourinary, and central nervous system endpoints in addition to sepsis and cardiac arrest.

There was a small but statistically significant difference in operative times for palatoplasty, where plastic surgeons performed the procedure on average quicker than otolaryngologists. A larger difference was noted in tip rhinoplasty with septum repair and osteotomies, where plastic surgeons spent an average of 162 minutes compared with 229 minutes for otolaryngologists. Given that plastic surgeons perform the majority of cleft surgical treatments, it is not unreasonable to expect a higher case load to contribute to increased efficiency in the operating room. The prior literature has examined outcomes of cleft repair between various surgical specialties, adding fuel to the heated debate over which specialty is most suited to care for children with this condition.[,,,] Outcomes are highly variable in the literature[] and there is a lack of surgical review articles compiling complication rates. A recent study by Paine et al reported a 4.2% complication rate in cleft lip repair,[] while a prior study by Nguyen et al demonstrated less than 3% in cleft palate repair.[] Our results demonstrate lower rates of complications, which are artificially lowered due to the limited 30-day follow-up period. Between the two cohorts in our study, results were similar with no statistically significant difference in terms of mortality, wound complications, unexpected reoperation, readmission, medical complications, or surgical complications, despite heterogeneous management approaches between otolaryngologists and plastic surgeons.

This analysis is not without limitations. Primary and secondary procedures were differentiated by CPT code, which is subject to error. Coding via CPT is a subjective task subject to error due to variations in coding between health care providers.[] Other surgical specialties involved in cleft patient care, including dental and oral and maxillofacial surgeries, are not included in the NSQIP database, and therefore we were unable to include their contributions to cleft care in this analysis. The NSQIP database tracks outcome data for up to 30 days postoperatively, thus limiting our ability to analyze long-term outcomes. Additionally, information regarding hospital teaching status is not included in the database; therefore, we were unable to assess hospital-level effects, which may introduce a bias due to variations in case mix at institutions. The pediatric NSQIP database is nascent and growing, with 50 participating institutions in 2012, 56 in 2013, and 64 in 2014,[] which is still an underrepresentation of institutions performing cleft care in the United States. Additionally, as the data gathered by NSQIP is multicentric and dependent on the input of a variety of health care institutions, the results may not be generalizable in all settings.

Conclusion

Plastic surgeons perform the majority of cleft surgical care across cleft lip, cleft palate, and rhinoplasty procedure types. In palatoplasty and tip rhinoplasty with septum repair and osteotomies, plastic surgeons perform procedures, on average, quicker than otolaryngologists. Significant variation exists in the treatment of cleft lip and palate between plastic surgery and otolaryngology with respect to surgical treatment timing, and procedure type, which may reflect differences in training. However, short-term metrics remain similar in cleft lip, cleft palate, and rhinoplasty procedures across mortality, wound occurrence complications, unexpected return to the operating room, unexpected readmission, surgical complications, and medical complications.

Disclosure

American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospitals participating in the ACS NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.

References

- Shi, M.; Wehby, G.L.; Murray, J.C. Review on genetic variants and maternal smoking in the etiology of oral clefts and other birth defects. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 2008, 84, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai CT, Cassell CH, Meyer RE; et al. National Birth Defects Prevention Network. Birth defects data from population-based birth defects surveillance programs in the United States, 2007 to 2011: highlighting orofacial clefts. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2014, 100, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shkoukani, M.A.; Chen, M.; Vong, A. Cleft lip a comprehensive review. Front Pediatr 2013, 1, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberge, L.C. Unilateral cleft lip and palate: simultaneous early repair of the nose, anterior palate and lip. Can J Plast Surg 2007, 15, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss RP; The American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association (ACPA) Team Standards Committee. Cleft palate and craniofacial teams in the United States and Canada: a national survey of team organization and standards of care. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1998, 35, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahai, F.R.; Williams, J.K.; Burstein, F.D.; Martin, J.; Thomas, J. The management of cleft lip and palate: pathways for treatment and longitudinal assessment. Semin Plast Surg 2005, 19, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boutray M, Beziat JL, Yachouh J, Bigorre M, Gleizal A, Captier G. Median cleft of the upper lip: a new classification to guide treatment decisions. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2016, 44, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiradfar, M.; Bakhshaee, M. Staged new technique to repair wide cleft lip and palate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010, 143 (Suppl 2), 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Surgeons. User Guide for the 2014 ACS NSQIP Pediatric. 2015. Available online: https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality pro- grams/nsqip/peds_acs_nsqip_puf_userguide_2014.ashx (accessed on 25 August 2016).

- Wehby, G.L.; Cassell, C.H. The impact of orofacial clefts on quality of life and healthcare use and costs. Oral Dis 2010, 16, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association. Parameters for evaluation and treatment of patients with cleft lip/palate or other craniofacial anomalies. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1993, 30 (Suppl), S1–S16. [Google Scholar]

- Shetye, P.R. Facial growth of adults with unoperated clefts. Clin Plast Surg 2004, 31, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmander-Agerskov, A. Speech outcome after cleft palate surgery with the Göteborg regimen including delayed hard palate closure. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1998, 32, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlastos, I.M.; Koudoumnakis, E.; Houlakis, M.; Nasika, M.; Griva, M.; Stylogianni, E. Cleft lip and palate treatment of 530 children over a decade in a single centre. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2009, 73, 993–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyuron, B. MOC-PS(SM) CME article: late cleft lip nasal deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008, 121 (Suppl 4), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, H. Unpalatable results force cleft surgeons to rethink. BMJ 1998, 316, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, A.G. Report on cleft lip and palate surgery. Surgeon’s specialty is less important than training and experience. BMJ 1998, 316, 1462. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davies, G. Report on cleft lip and palate surgery. Reaction from health professionals has been muted. BMJ 1998, 316, 1462–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.; Sandy, J. Report on cleft lip and palate surgery. Disagreement between specialties was not impetus for study. BMJ 1998, 316, 1462. [Google Scholar]

- van Aalst JA, Kolappa KK, Sadove M. MOC-PSSM CME article: nonsyndromic cleft palate. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008, 121 (Suppl), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine KM, Tahiri Y, Wes AM; et al. An assessment of 30-day complications in primary cleft lip repair: a review of the 2012 ACS NSQIP Pediatric. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2016, 53, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; Davies, S.M.; Bhattacharya, J.; Khosla, R.K.; Curtin, C.M. Cleft palate surgery: an evaluation of length of stay, complications, and costs by hospital type. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2014, 51, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, M.S.; Sharp, L.; Lipsky, M.S. Accuracy of CPT evaluation and management coding by family physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract 2001, 14, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American College of Surgeons. ACS NSQIP Pediatric Participant Use Data File. 2016. Available online: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/pediatric/pro- gram-specifics/quality-support-tools/puf (accessed on 10 October 2016).

© 2017 by the author. The Author(s) 2017.