Treatment Outcomes for Isolated Maxillary Complex Fractures with Maxillomandibular Screws

Abstract

:Material and Methods

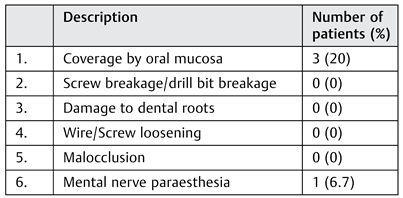

Results

|

Discussion

|

References

- Karlis, V.; Glickman, R. An alternative to arch-bar maxillomandibular fixation. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997, 99, 1758–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Pont, G. On the employment of juxtaosseous metallic hooks in intermaxillary fixation in jaw fractures. Riv Ital Stomatol 1965, 20, 791. [Google Scholar]

- Otten, J.E. Modified methods for intermaxillary immobilization. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z 1981, 36, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ito, M.; Handa, Y.; Okutomi, T.; et al. Application of von Otten intermaxillary immobilization for infant condylar fracture. J Jpn Stomatol Soc 1988, 37, 773. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, G.; Berardo, N. A simplified technique of maxillomandibular fixation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1989, 47, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.C. The intermaxillary screw: a dedicated bicortical bone screw for temporary intermaxillary fixation. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999, 37, 115–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thota, L.G.; Mitchell, D.A. Cortical bone screws for maxillomandibular fixation in orthognathic surgery. Br J Orthod 1999, 26, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coburn, D.G.; Kennedy, D.W.; Hodder, S.C. Complications with intermaxillary fixation screws in the management of fractured mandibles. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002, 40, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Bergh, B.; de Mol van Otterloo, J.J.; van der Ploeg, T.; Tuinzing, D.B.; Forouzanfar, T. IMF-screws or arch bars as conservative treatment for mandibular condyle fractures: quality of life aspects. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2015, 43, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Bergh, B.; Blankestijn, J.; van der Ploeg, T.; Tuinzing, D.B.; Forouzanfar, T. Conservative treatment of a mandibular condyle fracture: Comparing intermaxillary fixation with screws or arch bar. A randomised clinical trial. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2015, 43, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, A.A.; Reddy, U.K.; Warad, N.M.; Badal, S.; Jamadar, A.A.; Qurishi, N. Intermaxillary fixation screws versus Erich arch bars in mandibular fractures: a comparative study and review of literature. Ann Maxillofac Surg 2016, 6, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, A.M.; David, L.R.; DeFranzo, A.J.; Marks, M.W.; Molnar, J.A.; Argenta, L.C. Use of specialized bone screws for intermaxillary fixation. Ann Plast Surg 2000, 44, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the author. The Author(s) 2017.

Share and Cite

Gorka, R.; Gohil, A.J.; Gupta, A.K.; Koshy, S. Treatment Outcomes for Isolated Maxillary Complex Fractures with Maxillomandibular Screws. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2017, 10, 278-280. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1601864

Gorka R, Gohil AJ, Gupta AK, Koshy S. Treatment Outcomes for Isolated Maxillary Complex Fractures with Maxillomandibular Screws. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2017; 10(4):278-280. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1601864

Chicago/Turabian StyleGorka, Rahul, Amish Jayantilal Gohil, Ashish Kumar Gupta, and Santosh Koshy. 2017. "Treatment Outcomes for Isolated Maxillary Complex Fractures with Maxillomandibular Screws" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 10, no. 4: 278-280. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1601864

APA StyleGorka, R., Gohil, A. J., Gupta, A. K., & Koshy, S. (2017). Treatment Outcomes for Isolated Maxillary Complex Fractures with Maxillomandibular Screws. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 10(4), 278-280. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1601864