Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between stock returns and income inequality in South Africa, a country marked by persistently high levels of income disparities and a sophisticated and structurally unique financial market. Despite the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) being one of the most developed and liquid markets in Africa, stock ownership remains limited to a small segment of the population, often reinforcing pre-existing income inequalities. This study determines the relationship between stock returns and income distribution using the ARDL bound test methodology. Using time series data from 1975 to 2024, the study examines the extent to which stock market returns influence income distribution. The findings of the study suggest a positive relationship between stock returns and income distribution. This relationship suggests that higher stock market development disproportionately benefits capital holders. The long-term relationship seems to have limited feedback from inequality to stock returns. The findings aim to inform policies on inclusive financial participation and broad-based wealth generation to address South Africa’s structural inequalities.

1. Introduction

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 10 focuses on reducing inequalities both within and between countries, acknowledging that disparities in income, opportunity, and access hinder inclusive and sustainable development (United Nations, 2015; Magwedere & Marozva, 2025). Several targets were developed to support the developmental goals including reducing inequalities for a sustainable future. Inequality not only impedes poverty reduction efforts but also undermines social cohesion and individual well-being. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these challenges, contributing to the most pronounced increase in between-country inequality in the past three decades (Amponsah et al., 2023). Addressing such disparities requires a coordinated policy response, including equitable resource allocation, targeted investments in human capital, robust social protection frameworks, anti-discrimination measures, and enhanced support for marginalized communities.

The exclusion of marginalized populations from participating on the stock market reflects structural socioeconomic barriers that hinder access to wealth-building opportunities. Van Rooij et al. (2011) argued that low levels of financial literacy significantly reduce the likelihood of investing in stocks. Empirical evidence shows that barriers such as limited financial literacy, low-income levels, and lack of access to brokerage or digital trading platforms significantly reduce participation rates among low-income and minority groups (Osuma, 2025). Furthermore, structural issues including discriminatory lending practices, informational asymmetries, and urban–rural financial access gaps restrict the ability of marginalized populations to invest in equity markets. This systematic exclusion contributes to persistent income and wealth disparities, potentially undermining the role of financial markets in promoting inclusive economic growth. Moreover, reducing global inequality necessitates stronger international cooperation to reform trade and financial systems in ways that promote fairness, fair access, resilience, and shared prosperity.

The nexus between financial markets and income inequality has gained renewed attention in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. Although stock markets are conventionally regarded as mechanisms for efficient capital allocation and drivers of economic growth, their expansion does not necessarily translate into broad-based welfare gains, which include fair income distribution. In many economies, a persistent participation gap excludes lower-income households from equity market exposure, thereby restricting their access to capital gains and dividend income (Otinga et al., 2024). Evidence from policy institutions further indicates that widening income inequality is closely linked to rising household leverage, the growth of non-bank financial assets, and valuation dynamics that reinforce feedback loops between asset markets and systemic risk. Income concentration to a few large investors can lead to asset bubbles.

Linking stock returns to income inequality is complex and multifaceted. On the one hand, higher stock returns may increase wealth for those who own financial assets, thereby amplifying income and wealth inequality, particularly in economies where stock ownership is concentrated among upper-income groups (Markiewicz & Raciborski, 2022). On the other hand, well-functioning equity markets can enhance investment, job creation, and productivity, potentially contributing to broader economic inclusion. However, the net effect of stock market performance on inequality may depend on factors such as financial inclusion, financial literacy, tax policy, corporate governance, labour market structures, among others (Demirgüç-Kunt & Levine, 2009; Greenwood & Scharfstein, 2013). Hence the relationship between financial markets and income distribution has ripple effects in the real sector, as they influence asset markets, credit markets, and volatility in financial markets. Thus, studying the empirical relationship between this dynamic relationships is essential.

This study contributes to the literature by examining the impact of stock market returns on income inequality. By employing dynamic econometric techniques, the analysis aims to clarify whether stock returns exacerbate or alleviate income inequality. Subject to the main objective of the study, which is to determine the effect of stock market returns on income inequality, the research question of this study therefore is as follows: Do stock returns have a short-run and a long-run impact on income inequality in South Africa? There is a lack of empirical findings that investigate how market dynamics influence socioeconomic disparities.

2. Literature Review

Shifts in the equity premium or asset accumulation can be affected by shifts in income inequality, a finding suggested by Markiewicz and Raciborski (2022). This section discusses the theoretical frameworks and empirical review that guided this study.

2.1. Theoretical Review

2.1.1. Capital Income Theory

Capital income theory has its foundational ideas in classical and neoclassical economics. It analyzes how income is generated from capital ownership, and how capital returns contribute to income distribution and inequality (Piketty, 2014). Fisher argued that the value of capital is the present value of the future income streams (Fisher, 1906). Karl Marx postulated that the structural root of inequality stems from capital ownership (Marx et al., 2024). That is returns to capital such as dividends, interest, rents, and capital gains are unevenly distributed and drive structural income inequality. Developing arguments from capital theory, Piketty (2014) argued that when the return on capital (r) exceeds the rate of economic growth (g), wealth concentrates among capital owners, exacerbating inequality. Stock market returns contribute to capital income through dividends, capital gains, and share buybacks, all of which disproportionately accrue to top income earners. Capital income theory therefore clarifies how capital ownership patterns drive disparities. This theory is further supported by the life-cycle hypothesis where individuals plan their consumption and savings behaviour over their lifetime with the aim of maintaining a stable standard of living.

2.1.2. Asset-Based Inequality Theory

The increase in between and within countries’ income and wealth inequality across emerging and developing economies (EDEs) has prompted renewed interest in structural explanations of inequality. Asset-based inequality theory (ABIT) is one of the most compelling theories which argue that disparities in access to and accumulation of wealth-generating assets, particularly financial instruments such as equities, are at the heart of long-run inequality. While ABIT has been well-developed in the context of advanced economies, its application to EDEs remains comparatively under-theorized. Inequality in emerging and developing economies (EDEs) is structural with concentrated asset ownership (Piketty, 2014; Mian et al., 2020).

2.1.3. Portfolio Choice and Financial Literacy Theory

The Portfolio Choice and Financial Literacy Theory provide an essential framework for understanding disparities in stock market participation and the subsequent distributional effects of financial asset returns (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014). As stock markets are a key driver of wealth, this theory offers insight into how knowledge gaps and cognitive barriers contribute to rising income and wealth inequality. At its core, the theory posits that individuals make portfolio allocation decisions based on their financial literacy, risk preferences, and access to financial markets (Campbell, 2006; Van Rooij et al., 2011). Those with greater financial knowledge and sophistication are more likely to invest in high-yield assets such as equities. Since stock returns typically outperform other assets over time, this unequal participation results in disproportionate capital gains accruing to wealthier, better-informed households, exacerbating income inequality (Markiewicz & Raciborski, 2022). The theory explains differential investment behaviour by linking cognitive ability and education to tangible economic outcomes like wealth accumulation. Therefore, financial literacy determines effective portfolio optimization, which in turn explains how knowledge gaps constrain rational choices.

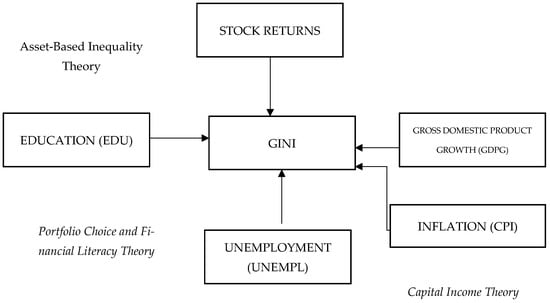

However, while the theory is intuitively appealing and empirically supported in several studies, it is not without limitations. The theory underplays systemic barriers such as exclusionary financial systems where structural inequality and informality are the main barriers to participation in the financial markets (Magwedere & Marozva, 2025). Despite the weaknesses, the theory is essential in providing a nuanced approach on the relationship between stock returns and inequality. The conceptual framework is presented in in Figure 1 showing the relationship between the key variables of the study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework. Source: Authors.

2.2. Empirical Literature Review

The effect of the stock market on socioeconomic outcomes is argued to be shaped by several factors across the regions of developing and developing countries. Lakner et al. (2022) argued that reducing the Gini index for each country by a percentage point per annum has a higher impact on poverty reduction than increasing economic growth by a percentage point above the forecasted rate. In emerging and developing economies, low financial inclusion and thin equity markets are a result of the accumulation of private assets by the elite. This has a potential of marking stock markets as a potential vector of inequality. Fagereng et al. (2020) show that returns on wealth are systematically higher for the rich, who are better positioned to invest in high-yield, risky assets like stocks. The rise in capital income with declining aggregate demand with excess savings and rising asset prices amplify inequality by shifting income away from labour (Mian et al., 2020).

Greenwald et al. (2021) demonstrate how rising firm markups and profit shares translate into stock market gains that bypass most workers, reinforcing the capital–labour income divide. Positive stock returns tend to substantially and persistently raise the income shares of top income earners. Using state-level data for the United States, Bahmani-Oskooee et al. (2022) acknowledge the existence of an asymmetric relationship between stock returns and income inequality. In the same study, they concluded that positive stock returns have un-equalizing effects on income inequality and negative returns have equalizing effects. Financial integration is argued to have an effect on income inequality as it opens the financial market to global investors in economies that rely on foreign financing compounded with free trade obstacles that influence income inequality (Baek & Shi, 2016). The effect of the stock market on socioeconomic dynamics affects the sustainability of economic growth as higher income inequalities feed into the vulnerabilities of the financial sector (Dang et al., 2024).

Furthermore, rising financialization amplifies the share on income from dividends, interest, and capital gains. In many economies, rising stock market returns have coincided with widening income disparities, raising questions about the distributive effects of financial development (Berg et al., 2018). The extent to which different population segments can participate in and benefit from stock market investments influences the relationship between market returns and income inequality (Blau et al., 2021).

Despite the growing body of literature on inequality and finance, empirical investigations directly linking stock returns to income inequality remain limited, particularly in emerging and developing economies. Most studies focus on the impact of financial development or liberalization more broadly, often overlooking the dynamic and distributional consequences of equity markets (Jauch & Watzka, 2016; Denk & Cournède, 2015). Furthermore, the role of financial asset concentration, capital gains, and stock-driven wealth effects in shaping inequality outcomes remains underexplored. It is not well documented if an increase in income inequality is associated with a decline in equity premiums; hence, an empirical investigation of this relationship needs to be conducted.

3. Materials and Methods

The study used a time series study for South Africa from 1975 to 2024. The period of the study was solely determined by the data availability for the variable considered in this study. Data on the GINI index was obtained from the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID). The World Bank Development Indicators was used to extract the data that was used for the analysis. The stock returns were calculated as a percentage change in the JSE All-Share Index. Table 1 summarizes the variable description, data sources, and the expected relationship with the dependent variable.

Table 1.

Definition of variables and data sources.

Autoregressive Distributed Lags (ARDLs)

The ARDL framework facilitates the joint estimation of short- and long-run dynamics and offers distinct advantages over traditional cointegration methods, as it can incorporate variables integrated in the order I(0) and I(1) but not I(2) (Engle & Granger, 1987; Johansen & Juselius, 1990; Pesaran & Shin, 1999; Pesaran et al., 2001). Its suitability for small samples and its capacity to mitigate potential endogeneity are particularly relevant given the possibility of common shocks affecting both inequality and the stock market, further supporting its use. To ensure the absence of I(2) processes, Augmented Dickey–Fuller and Phillips–Perron tests were conducted, as higher-order integration would invalidate the bounds F-test (Pesaran et al., 2001; Magwedere & Marozva, 2023). Lag lengths were selected using the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The model specifies inequality as a function of stock returns and a vector of control variables, as explained in Table 1, with long-run relationships estimated through the general ARDL (p, q, q, q) form. In addition, the single-equation nature of the ARDL approach simplifies estimation and interpretation while yielding consistent long-run parameters and addressing autocorrelation and endogeneity concerns (Pesaran & Shin, 1999; Pesaran et al., 2001; Narayan, 2005).

All the other equations for the vector of dependent variables were formulated as in Equations (1) and (2).

Although ARDL was the appropriate method for this study because the variables are integrated at level and first difference, it assumes unidirectional causality from explanatory variables to the dependent variable, which this study noted as a weakness as the direction of causality could not be established using this methodology.

4. Results

This section discusses the results of the study. The descriptive statistics of the study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

The maximum of stock returns is 0.85 with a minimum of −0.42. On average, stock returns is 0.11. The data values for the stock returns are well spread from the mean. Inequality has a maximum and a minimum of 72.5 and 68.89, respectively, showing a higher level of inequality in South Africa, as measured by the GINI index. The spread from the mean as measured by the standard deviation is 2.48 for inequality, showing that the data is very close to the mean. This is also explained by persistently high inequality levels in South Africa.

4.1. Correlation Matrix

Table 3 shows the correlation matrix.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

The pre-diagnostic statistics also included the correlation matrix, which are reported in Table 2. Correlation was performed to confirm the association between the variables and to exclude variables that have high correlation as they can cause multicollinearity problems.

4.2. Unit Root Tests

While the ARDL cointegration approach does not strictly require prior unit root testing, verifying that none of the series are integrated in order two I(2) is essential, as their presence would invalidate the model (Martins et al., 2021; Magwedere & Marozva, 2023). Accordingly, unit root tests are conducted to establish the integration properties of the variables under consideration. Thus, the stationarity properties of the series were assessed using the Augmented Dickey–Fuller and Phillips–Perron unit root tests; the results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Unit root test results.

As reported in Table 3, the variables are integrated in order zero or one, thereby confirming the appropriateness of the ARDL methodology for analyzing the relationship between stock returns and inequality.

The bound testing procedure was used to examine the relationship between the variables and Table 4 displays the results. The F-Statistic where GINI, STOCK RETURN, GDPG, EDU, UNEMPL, and CPI are dependent variables was higher than the first order integration (higher bound) at 5%; hence, it was concluded that there was cointegration. Akaike information criteria (AIC) and the individually determined lag length were employed to determine the optimal lag length. The optimal lag lengths for all six models were ARDL (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1).

Table 4 reports the results of the cointegration tests.

The results in Table 5 provide evidence of a stable long-run equilibrium relationship between inequality (GINI) and the explanatory variables. Even when the other explanatory variables are used as dependent variables, the results in Table 5 confirm cointegration. Given the confirmation of cointegration reported in Table 5, both the long-run and short-run dynamics are subsequently estimated, and the results are reported in Table 6.

Table 5.

Bounds tests bounds F-test for cointegration.

Table 6.

Cointegration and error correction model results.

The results of the ARDL cointegration tests are reported in Table 6. The results in Table 6 also included models 3–6, although not reported in text earlier due to space consideration the results are presented in Table 6.

As was previously highlighted in the Materials and Methods Section, the specified models seek to examine the relationships between stock returns (proxied by the difference between the JSE ALL Share Index) to calculate stock returns (STOCK RETURN), income inequality (GINI), economic growth (GDPG), education (EDU), unemployment (UNEMPL), and inflation (CPI). The results reported in Table 5 are the simultaneous estimation of the short- and long-run effects as estimated by the ARDL framework. The relationship between inequality and stock returns is significant and positive. Higher stock returns disproportionately benefit capital holders, supporting the capital income theory prediction that stock market gains exacerbate inequality. Capital income theory (Atkinson & Bourguignon, 2000; Piketty, 2014) emphasizes the role of returns on capital (r) relative to economic growth (g) in determining income inequality. When the rate of return on capital exceeds the rate of economic growth (r > g), wealth tends to concentrate among asset holders, leading to persistent inequality. The heterogeneity of agents and their capacity to hold financial assets (capital owners) owns the economy’s financial wealth. Furthermore, asset-based inequality theory (ABIT) augments the capital income theory by arguing that capital gains accrue to asset owners, potentially widening inequality (Piketty, 2014). Hence the positive relationship between income inequality and stock returns is theoretically supported by the theories discussed in Section 2.

The results from the other models STOCK RETURN appears insignificant or less consistent when GDPG, EDU, or CPI are the dependent variables. In model 2, when stock returns is the dependent variable, the coefficient on GINI is 0.143 (not significant), indicating limited direct feedback from inequality to stock returns in the long run. This empirical finding is consistent with the empirical findings of (Dang et al., 2024) where stock returns drive inequality, but inequality does not always directly drive stock returns. The ARDL methodology was the most appropriate methodology to use as inequality and financial markets are not independent: inequality can influence aggregate demand, investment, and risk-taking behaviour, which in turn affects stock market performance. Equally, volatile stock returns may worsen inequality by creating instability in household wealth. Studying both helps to understand feedback loops between inequality and financial stability. This is confirmed by the error correction term, which is negative and significant, showing that there are feedback loops between income inequality and stock returns.

The error correction term (ECT) captures the speed of adjustment toward long-run equilibrium. For all the models, the error correction term is negative and significant, confirming that after short run disequilibrium, the models return to long-run equilibrium (Magwedere & Marozva, 2023). This validates the ARDL approach for capturing long- and short-run dynamics. Thus, there is an existence of a stable long-run relationship between income inequality and stock returns. This implies that deviations from equilibrium are gradually corrected over time, with approximately 6% of disequilibrium adjusted each period for inequality and stock returns. This suggests that while inequality and stock returns may diverge in the short run due to shocks, they tend to converge towards a long-run equilibrium path.

For the macroeconomic variables considered in this study as control variables, it shows that macroeconomic variables matter. Unemployment and inflation significantly interact with inequality, highlighting that stock market effects are not isolated from broader economic conditions. The results show that unemployment increases income inequality, as exclusion from labour markets raises income disparities, a finding that concurs with Magwedere and Marozva (2025). Furthermore, this finding is theoretically supported by limiting access to capital. If inflation erodes the purchasing power of poorer households, it worsens inequality.

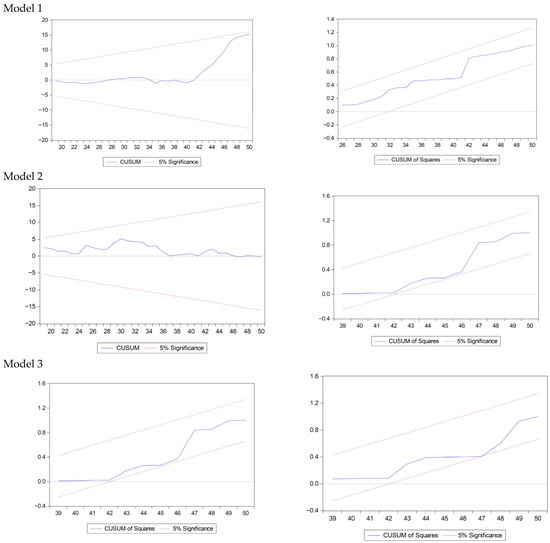

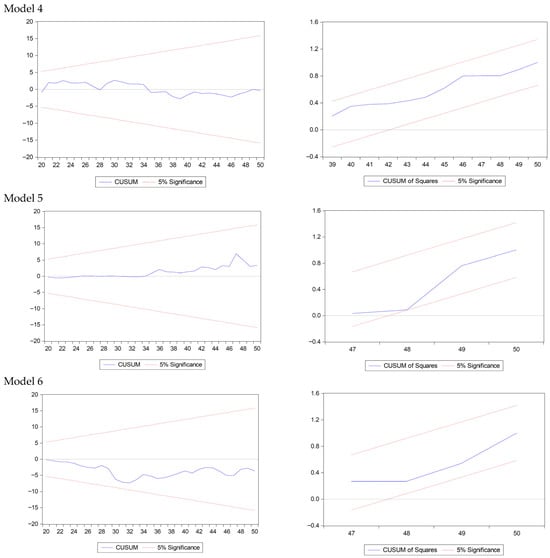

4.3. Cumulative Sum (Cusum) Results

For all the variables, the models were stable as they fall within the confidence bands of 5% significance as shown in Figure 2. Thus, all the parameters of the models are stable within the estimated period. There are no structural breaks that could be detected from the estimated co-efficient; therefore, the ARDL models are stable.

Figure 2.

Cusum and Cusum sum of squares. Source: Authors’ own calculations using E-views.

5. Conclusions

The dominant theme of this article is the effect of stock returns on inequality in the distribution of income. There is a gap in the literature on linking the concept of income inequality and the financial market despite the potential of income distribution on creating wealth concentration and credit bubbles, which may lead to financial crises. The study contributes to academic debates on the drivers of inequality. The aim of the study was to link stock returns and income inequality. Understanding this relationship is critical to explaining how financial markets contribute to widening or narrowing inequality. The findings of the study suggested a significant and positive relationship between income inequality and stock returns. A unit increase in stock return increases income inequality by 1.988 units.

This study recommends further studies that encompass the behavioural variables, if the data is available, on the relationship between stock returns and income inequality. This will assist with broadening the literature available on risk-taking channels in highly unequal societies, which might result in high market swings. Further studies on the asymmetric nature of stock returns are recommended to analyze the effects of negative/positive returns on income distribution. The limitations of the study were mainly due to the data frequency. Data on inequality as proxied by the GINI is available annually while stock returns data is available daily/quarterly. To reduce the measurement errors that could have emanated from data interpolation, the regressions were run using the annual frequency of the stock returns. Furthermore, findings from South Africa may not be generalized to other markets due to unique or structural historical inequality drivers, market structure, and policy environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.M. and G.M.; methodology, M.R.M. and G.M.; software, G.M.; validation, M.R.M. and G.M.; formal analysis, M.R.M. and G.M.; data curation, M.R.M. and G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.M.; writing—review and editing, M.R.M. and G.M.; visualization, M.R.M. and G.M.; supervision, G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the University of South Africa.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study is publicly available data obtained from.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amponsah, M., Agbola, F. W., & Mahmood, A. (2023). The relationship between poverty, income inequality and inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Modelling, 126, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A. B., & Bourguignon, F. (2000). Introduction: Income distribution and economics. In Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 1, pp. 1–58). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, I., & Shi, Q. (2016). Impact of economic globalization on income inequality: Developed economies vs. emerging economies. Global Economy Journal, 16(1), 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M., Hasanzade, M., & Bahmani, S. (2022). Stock returns and income inequality: Asymmetric evidence from state level data in the US. Global Finance Journal, 52, 100715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A., Ostry, J. D., Tsangarides, C. G., & Yakhshilikov, Y. (2018). Redistribution, inequality, and growth: New evidence. Journal of Economic Growth, 23, 259–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, B. M., Griffith, T. G., & Whitby, R. J. (2021). Income inequality and the volatility of stock prices. Applied Economics, 53(38), 4404–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. Y. (2006). Household finance. The Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1553–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D. Q., Wu, W., & Korkos, I. (2024). Stock market and inequality distributions—Evidence from the BRICS and G7 countries. International Review of Economics & Finance, 92, 1172–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2009). Finance and inequality: Theory and evidence. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 1(1), 287–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denk, O., & Cournède, B. (2015). Finance and income inequality in OECD countries. In OECD economics department working papers (No. 1224). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. F., & Granger, C. W. (1987). Co-integration and error correction: Representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 55, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagereng, A., Guiso, L., Malacrino, D., & Pistaferri, L. (2020). Heterogeneity and persistence in returns to wealth. Econometrica, 88(1), 115–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, I. (1906). The nature of capital and income. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, D. L., Leombroni, M., Lustig, H., & Van Nieuwerburgh, S. (2021). Financial and total wealth inequality with declining interest rates (No. w28613). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, R., & Scharfstein, D. (2013). The growth of finance. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(2), 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauch, S., & Watzka, S. (2016). Financial development and income inequality: A panel data approach. Empirical Economics, 51, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S., & Juselius, K. (1990). Maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration with applications to the demand for money. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 52(2), 169–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakner, C., Mahler, D. G., Negre, M., & Prydz, E. B. (2022). How much does reducing inequality matter for global poverty? The Journal of Economic Inequality, 20(3), 559–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magwedere, M. R., & Marozva, G. (2023). Household debt, inequality, and financial stability nexus. International Journal of Monetary Economics and Finance, 16(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magwedere, M. R., & Marozva, G. (2025). Inequality in low-and middle-income countries: Does fiscal policy matter? The Economics and Finance Letters, 12(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz, A., & Raciborski, R. (2022). Income inequality and stock market returns. Review of Economic Dynamics, 43, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, T., Barreto, A. C., Souza, F. M., & Souza, A. M. (2021). Fossil fuels consumption and carbon dioxide emissions in G7 countries: Empirical evidence from ARDL bounds testing approach. Environmental Pollution, 291, 118093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K., Reitter, P., & North, P. (2024). Capital: Critique of political economy (Vol. 1). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, A. R., Straub, L., & Sufi, A. (2020). The saving glut of the rich (No. w26941). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Narayan, P. K. (2005). The saving and investment nexus for China: Evidence from cointegration tests. Applied Economics, 37(17), 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuma, G. (2025). The impact of financial inclusion on poverty reduction and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: A comparative study of digital financial services. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 11, 101263. [Google Scholar]

- Otinga, N. K., Obi, P., & Mugo-Waweru, F. (2024). Stock market participation puzzle: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2396531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (1999). An autoregressive distributed lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. In Econometrics and economic theory in the 20th Century. The Ragnar. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century: A multidimensional approach to the history of capital and social classes. British Journal of Sociology, 65(4), 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. (2015). The 17 goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. (2011). Financial literacy and stock market participation. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(2), 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.