Abstract

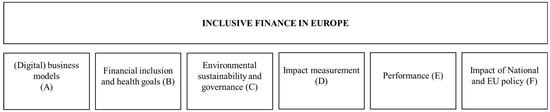

This study examines how inclusive finance organisations are adapting to the European Union (EU)’s digital–green twin transition and how regulatory design can reinforce this alignment. Drawing on qualitative insights from 26 institutions—including microfinance organisations, small and medium-sized enterprise finance providers and socially oriented fintechs—across the EU and neighbouring countries, the analysis identifies how digitalisation, financial inclusion and environmental sustainability are being integrated into organisational strategies. The findings show that hybrid models, built on partnerships between nationally rooted microfinance institutions and cross-border fintech platforms, enable scalable, high-tech, high-touch ecosystems that align closely with sustainability objectives. The study argues that a coordinated EU-wide regulatory sandbox would advance inclusive, green financial innovation and build resilience across the inclusive finance ecosystem.

1. Introduction

Millions of people across Europe remain underbanked and, despite improvements, persistent gaps in digital and financial literacy leave them vulnerable in an increasingly digitised economy (Botsari et al., 2024; European Banking Authority, 2025; European Commission, 2023c; Eurostat, 2024). Around 18% of EU citizens exhibit low levels of financial literacy (European Commission, 2023c) and more than 4% of adults are financially excluded (World Savings and Retail Banking Institute & European Savings and Retail Banking Group, 2022). After regulatory obstacles and payment delays, accessing finance is the third most significant challenge for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), with over 25% reporting persistent difficulties in this area (European Commission, 2025a).

Since the 2008 financial crisis, fintech has expanded access to finance for underserved populations by reducing asymmetric information, lowering transaction costs and confronting other market imperfections that prevent low-income individuals from accessing formal financial services, thereby limiting their means of escaping poverty (Demir et al., 2020; Gomber et al., 2017). Fintech has also advanced innovative forms of financial engagement, such as blockchain-based social crowdfunding, which can mobilise community-driven capital for social enterprises and amplify inclusive finance (Nguyen et al., 2021). While fintech in inclusive finance involves risks (Colangelo, 2024; Ferrari, 2022; Grassi, 2024; Lee & Shin, 2018; Philippon, 2020; Saeed & Omlin, 2023), the EU’s twin transition introduces regulatory opportunities for digital innovators to close inclusion gaps.

The EU’s twin transition is a strategic initiative aimed at achieving simultaneous digital and green transformation (European Commission, 2020a). The initiative is in line with broader international frameworks, including the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Puschmann & Khmarskyi, 2024) and OECD guidance on inclusive, green and digital transformation (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, n.d.). Yet, despite this momentum, researchers continue to treat digital and green innovation separately. As a result, a gap remains in the literature regarding how inclusive finance organisations integrate these transformations in practice (Fersi et al., 2023; García-Pérez et al., 2018; Le et al., 2020; López-Penabad et al., 2024; Moro-Visconti, 2021; Preziuso et al., 2023).

This article addresses this gap and examines how inclusive finance organisations are adapting to align with the EU’s twin transition, and how regulatory design can support this process. The analysis is guided by the following central question: How are inclusive finance organisations navigating the twin transition, and what regulatory mechanisms could enhance their capacity to innovate inclusively?

Regulatory sandboxes offer a controlled environment for testing financial innovation with supervisory oversight (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023b; Zetzsche et al., 2018). However, their effectiveness depends on integration within broader innovation ecosystems and consistency with existing regulatory tools (Buckley et al., 2020). Fragmented national approaches, regulatory lag and uneven transitions across member states act as ‘disenablers’ of fintech (Ahern, 2021), underscoring the need for a coordinated EU-level response. This paper proposes an inclusive regulatory sandbox, coordinated by the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs), to support experimentation among underserved groups and strengthen resilience across the inclusive finance ecosystem.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 contains a review of the literature on digitalisation, sustainability and inclusive finance. Section 3 outlines the methodology and data sources. In Section 4, the findings and the resulting organisational typology are presented, followed by a longitudinal update. Ecosystem design and policy implications are discussed in Section 5. Section 6 concludes with recommendations for practice and future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The EU’s Twin Transition Framework

The EU’s twin transition framework builds on a set of digital and sustainability policies designed to simultaneously advance the green and digital transformations. These frameworks shape the strategic and operational environment of inclusive finance organisations, influencing how they adopt digital tools, manage data, and integrate environmental objectives into their business models.

Most regulatory instruments for responsible digitalisation in the EU are anchored in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR; European Union, 2016), which stipulates fundamental safeguards for the protection of personal data and trust. The GDPR establishes the baseline for digital compliance for actors in the inclusive finance sector, particularly those that rely on digital onboarding, alternative data and automated decision-making. It also serves as the foundation for other frameworks such as the European Data Strategy (European Commission, 2023a), the Blockchain and Web3 Strategy (European Commission, 2023b), the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act (European Union, 2024b) and the AI Continent Action Plan (European Commission, 2025c), which collectively aim to ensure the ethical and secure use of data in increasingly automated financial ecosystems. These frameworks directly influence how inclusive finance organisations deploy digital tools while maintaining client protection and algorithmic accountability. Together, the various frameworks support the EU’s Digital Finance Package (DFP), a strategy that includes legislation to tackle the risks associated with cryptocurrencies and cybersecurity (European Commission, 2020b).

In terms of sustainability, key frameworks include the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (European Union, 2019), the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD; European Union, 2022) and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D; European Union, 2024a). Together, these seek to align corporate practices with the objectives of the European Green Deal, namely a sustainable, climate-neutral economy by 2050 (European Commission, n.d.). The Simplification Omnibus Package narrows the scope of the CSRD and CS3D, reducing the number of companies required to comply (European Commission, 2025b).

This shift risks excluding many actors involved in inclusive finance from key sustainability frameworks unless they voluntarily opt in. As an alternative pathway, the European Commission (2025d) has proposed the Voluntary Sustainability Reporting Standard for SMEs. This simplified framework enables non-listed MSMEs to make environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosures when requested by larger companies or financial institutions subject to CSRD requirements. This voluntary mechanism allows inclusive finance organisations to remain connected to sustainability-oriented value chains without the administrative burden of full CSRD compliance.

Climate-related financial policies are also gaining momentum, particularly given the introduction by the European Central Bank (European Central Bank, 2025) of a ‘climate factor’ in its collateral framework. This is intended to mitigate transition risks and enhance the resilience of monetary policy implementation. Because inclusive finance organisations often rely on partnerships with regulated financial institutions, these monetary policy adjustments indirectly influence their funding conditions, risk assessments and strategic priorities.

2.2. Research on the Digital–Green Twin Transition

Several studies have highlighted that, despite the promise of the twin transition, its implementation has been fragmented and often contradictory. Existing research reveals tensions between digitalisation and environmental sustainability, and divergent interpretations of how these transformations unfold within particular organisational and policy contexts. These debates are directly relevant for inclusive finance organisations, which must navigate opportunities and trade-offs in their engagement with the EU’s twin transition. For instance, Müller et al. (2024) reveal that in most cases digital and green transitions are pursued in parallel, rather than synergistically, leading to unseen contradictions and misaligned policies. This is particularly true for innovations in AI, which depend on energy-intensive cloud computing systems (Crawford, 2024). In an empirical study of the EU’s twin transition, Bianchini et al. (2023) highlight how certain digital technologies, in particular big data and computing infrastructure, can exacerbate negative environmental externalities. Taken together, these findings emphasise the need for robust green innovation ecosystems to limit unintended sustainability trade-offs.

Several studies have demonstrated the social benefits of the twin transition. Revoltella (2020) argues that the strategy offers the EU a unique opportunity to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic by fostering inclusive and sustainable growth. The strategic alignment of digitalisation and green transformation is key to boosting competitiveness, job creation and social cohesion. These potential benefits are why inclusive finance organisations are increasingly expected to engage with the twin transition, even as its implementation remains uneven.

In China, research has highlighted the environmental benefits of digital inclusive finance (DIF) arising from its role in promoting green innovation. Ma (2023) identifies two key mechanisms for this effect: the easing of financing constraints and strengthening of internal governance. Using data from Chinese enterprises, the study finds that DIF improves the quantity and quality of green technology innovation, particularly when digital platforms employ big data and AI to enhance corporate control systems. As Du et al. (2024) show, DIF significantly supports green innovation among underserved Chinese SMEs by lowering financing barriers. With DIF, digital tools, such as big data and mobile platforms, are deployed to reduce costs and expand access to capital, even for businesses with limited collateral or operating in remote locations. The impact intensifies with digital maturation, as advanced SMEs better engage with platforms, share data and manage risk. Although based on the Chinese context, these studies highlight the mechanisms through which digitalisation can drive green innovation.

Kovacic et al. (2024) raise concerns about how the twin transition is legitimised, which is often through techno-utopian narratives that mask contradictions between economic growth and sustainability. Their interpretative analysis of EU policy documents and recovery plans reveals the use of digital imaginaries—defined here as policy narratives that portray digital technologies as inherently synergetic with sustainability—to reframe real tensions as synergies, even when the implementation is inconsistent. Similarly, Ferrari (2022) argues that the EU’s industry-driven fintech policy often fabricates consumer interest to justify ‘platformisation’, understood as the consolidation of market power by digital platforms that mediate financial services and reshape access conditions for smaller providers. There is thus a clear need for those in the inclusive finance ecosystem to engage critically with the twin transition, not only as a strategic opportunity, but as a contested policy area where digital and green objectives may conflict. Recognising these imaginaries and power dynamics is essential for understanding how inclusive finance organisations interpret and operationalise the transition in practice.

2.3. Fintech for Social and Environmental Sustainability

Regulatory developments have strengthened fintech’s role in advancing financial inclusion. The EU’s open-banking (OB) initiative, introduced through its second Payment Services Directive in 2018, enhanced user control over financial data and increased competition (European Union, 2015; Preziuso et al., 2023). Open finance (OF) builds on this foundation by extending data-sharing frameworks beyond payments to include pensions, mortgages, insurance and investments. When designed with inclusivity in mind, OF can enhance risk profiling and facilitate more tailored services by accounting for country-specific factors and fostering cross-sectoral collaboration. As it evolves to encompass broader open data frameworks, including non-financial domains, OF has the potential to unlock significant socioeconomic benefits (Arner et al., 2022; Awrey & Macey, 2023; Colangelo & Khandelwal, 2025; Fernandez Vidal, 2024; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023a; Remolina, 2024). However, these opportunities coexist with structural ESG risks that influence how inclusive finance organisations operationalise the twin transition.

Environmental sustainability risks. Green and climate finance have become critical to sustainable development, particularly by facilitating ecological and renewable energy transitions (Joshipura et al., 2025). Green fintech, an emerging subset of fintech, strategically integrates digital financial technologies, such as distributed ledger technology, AI, crowdfunding and smart contracts, into the EU’s sustainable finance framework, facilitating carbon credit trading, clean energy finance and ESG performance assessment (Macchiavello & Siri, 2022). The European Central Bank (2024) highlights the rapid growth of fintechs across the EU, particularly in financial centres where institutional support schemes, regulatory clarity and equity financing ecosystems have catalysed innovation and the expansion of the sector. This strategic clustering has accelerated the development of green fintech platforms, positioning them as pivotal tools in advancing the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs), particularly those related to the environment, including clean energy (SDG 7), climate action (SDG 13) and biodiversity (SDGs 14 and 15; Puschmann & Khmarskyi, 2024). However, research reveals that inconsistencies in rating methodologies across assessment bodies undermine the reliability of the ESG scores assigned to green fintech companies, eroding stakeholder confidence and complicating the relationship with the EU’s sustainability goals (Ding et al., 2024; Jin et al., 2024). Moreover, green fintech innovations often rely on energy-intensive infrastructure, such as cloud systems and blockchain, creating tensions with their sustainability mission (Crawford, 2024; De Vries, 2021).

Social inclusion risks. Fintech design often prioritises mainstream users, inadvertently widening the exclusion gap (Lee & Shin, 2018; Sant’Anna & Figueiredo, 2024). This is especially problematic in the context of platformisation, as dominant digital finance platforms consolidate market power and marginalise smaller actors and underserved populations (Ferrari, 2022). Supporting financial and digital literacies remains essential for equitable participation in and sustainable use of financial services, particularly by those in vulnerable groups, who are frequently overlooked, even in developed economies (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018; Fernández-Olit et al., 2020; Grohmann et al., 2018; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2013; UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2018). Inclusive finance organisations must tailor their strategies to the needs of these groups, and employ tools like personalised education, intuitive user experiences, and dedicated support teams (Koefer et al., 2024).

Recent data from the Global Findex Database 2025 (World Bank, 2025) and the European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless (2024) confirm persistent gaps, especially among low-income and homeless populations. The persistence of these divides is a reminder of the need to understand how inclusive finance organisations can adapt their digital strategies to avoid reinforcing exclusion. The COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing digital transformation have exacerbated these divides. During crises, women, older adults, migrants and rural populations are disproportionately impacted due to limited digital access, low literacy and weak consumer protections (Tay et al., 2022). Such structural biases can be reinforced by automated decision-making via machine learning and deep learning (Philippon, 2020). The opacity of ‘black box’ AI systems has prompted interest in explainable AI that would improve transparency in domains such as credit scoring (Dazeley et al., 2021; Saeed & Omlin, 2023). These algorithmic risks underscore the importance of examining how inclusive finance organisations balance innovation with fairness, transparency and accountability.

Governance risks. As fintech expands into broader financial and extra-financial domains, users, particularly those with limited digital literacy or access, are increasingly exposed to complex decision-making processes and heightened privacy and security risks. Regulation-driven data-sharing regimes may empower consumers by giving them control over their financial data. However, they also introduce trade-offs that, without adequate safeguards, may disproportionately affect vulnerable populations (Colangelo, 2024). As Grassi (2024) shows in the context of data-driven insurance, customers’ willingness to share personal data varies significantly depending on the type of data and the perceived reward, especially when the incentive is financial. There is a concern that OF models built on such selective data-sharing behaviours may inadvertently reinforce exclusion and bias in the interpretation of analytics and models. These dynamics illustrate why inclusive finance organisations must navigate data-governance regimes carefully to avoid reproducing structural inequalities.

The European Commission has addressed these risks by introducing a suite of regulatory frameworks for sustainable digitalisation. The AI Act establishes a risk-based approach to AI governance, mandating transparency, human oversight and fairness in high-risk applications, such as financial services. The complementary AI Continent Action Plan aims to position Europe as a global leader in trustworthy AI through investment in large-scale computing infrastructure, AI factories and support to SMEs through the InvestAI facility. Likewise, the Blockchain and Web3 Strategy promotes energy-efficient and interoperable distributed ledger technologies, including the European Blockchain Services Infrastructure, which supports cross-border financial innovation aligned with the EU’s values.

The European Data Strategy, anchored by the Data Act, Governance Act, and the recently published Data Union Strategy (European Commission, 2025f), ensures fair access to data while safeguarding rights. Finally, the DFP provides a comprehensive roadmap for modernising financial services, regulating crypto-assets and enhancing digital resilience. It supports innovation while safeguarding consumer rights and financial stability, particularly for underserved populations more susceptible to digital exclusion. Collectively, these initiatives reflect the EU’s commitment to embedding ethical, inclusive and sustainable principles into the digital transformation of finance. Collectively, these frameworks illustrate the regulatory complexity that inclusive finance organisations must navigate in attempting to align digitalisation with sustainability.

Overall, these ESG risks call attention to the need for empirical research on how inclusive finance organisations interpret and operationalise sustainability commitments in a context of technological and methodological uncertainty.

2.4. Microfinance Institutions’ Initiatives Between Digitalisation and Environmental Sustainability

Microfinance institutions (MFIs) operate at the intersection of digitalisation, financial inclusion and environmental sustainability. The literature shows that their transition pathways are shaped by persistent inclusion gaps, pressures to align mission-driven models with sustainability objectives and uneven organisational capacities. While MFIs continue to prioritise outreach to vulnerable populations, they increasingly adopt digital tools to enhance efficiency and expand access and are progressively integrating environmental considerations into their business models. Yet existing studies highlight fragmented approaches and unresolved tensions and indicate that MFIs face distinct challenges in reconciling their social mission, technological innovation and environmental sustainability within the broader twin-transition agenda.

There have been ongoing concerns regarding MFIs’ ‘mission drift’ (Mia et al., 2023)—a phenomenon defined by Cull et al. (2007) as the tendency of microlending banks to shift from their original objective of serving the poorest of the poor toward optimising commercial success. As a result, many MFIs continue to balance social impact and financial sustainability in their provision of financial services to low-income and marginalised populations (Hermes & Hudon, 2018; Mersland et al., 2019). Persistent financial vulnerability, especially among underbanked populations and SMEs in Southern and Eastern Europe (Botsari et al., 2024; World Savings and Retail Banking Institute & European Savings and Retail Banking Group, 2022), is a critical issue, and inclusive finance is a matter of strategic importance. Bollaert et al. (2021) show that inclusive finance bridges social development and economic growth by expanding credit access, stimulating household spending and encouraging the growth of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). The EU’s economy depends heavily on MSMEs, which number 26 million, comprise 99.8% of Europe’s non-financial enterprises and employ 89 million people (Botsari et al., 2024). Yet, financial constraints persist, limiting their capacity to innovate and achieve scale (Chiappini et al., 2022). MFIs must balance outreach with operational sustainability while adapting to increasingly digital financial ecosystems.

MicroFintech, which merges the technological agility of fintech with the social ethos of microfinance, presents a compelling framework for inclusive innovation (Moro-Visconti, 2021). Recent systematic evidence confirms the centrality of fintech in advancing financial inclusion (Dao et al., 2025). Fersi et al. (2023) establish that, despite posing challenges to operational efficiency, digitalisation substantially improves social performance. Innovation is thus more closely aligned with the social objectives of MFIs than strategies focused exclusively on cost reduction. Other scholars have argued that MFIs can harness digitalisation to improve outreach and operational efficiency, especially when supported by robust infrastructure and human-centric design (Khanchel et al., 2025; Siwale & Godfroid, 2022). Large MFIs with deposit-taking capabilities appear best positioned to leverage these innovations for financial sustainability while expanding access and reducing costs (Dorfleitner et al., 2019, 2022). Evidence from digital microfinance platforms reinforces this dynamic. Interest-free P2P lending on Kiva illustrates how trust-based mechanisms and social underwriting can channel capital to vulnerable borrowers, including women and immigrants, thereby expanding access to finance for underserved groups (Dorfleitner et al., 2021).

In the context of OB, hybrid models formed through strategic collaborations among MFIs, fintechs and banks can scale inclusive financial services across borders, provided that they receive targeted regulatory support (Preziuso et al., 2023). However, the literature offers limited insight into how MFIs strategically prioritise digitalisation initiatives, or how their size, governance structures and partnerships shape their capacity to adopt inclusive digital models.

Inclusive finance organisations are also increasingly embedding environmental sustainability into their business models. Forcella and Hudon (2016) identify institutional size, environmentally conscious investors and access to larger loans as key drivers of MFIs’ environmental performance. Allet and Hudon (2015) show that environmental engagement does not compromise financial performance, while García-Pérez et al. (2018) highlight persistent challenges in harmonising financial, environmental and governance priorities, suggesting that integration remains a complex undertaking. Le et al. (2020) caution that financial inclusion, if not carefully managed, may inadvertently increase carbon emissions, and embedding environmental safeguards into inclusive finance strategies is thus critical. López-Penabad et al. (2024) argue that the long-term viability of MFIs hinges on their ability to embrace both social innovation and environmental responsibility.

The literature does not, as yet, explain how MFIs reconcile social missions, digital transformation and environmental sustainability in practice, nor how they interpret the twin transition as a strategic framework. There is thus a clear need for an analytical framework that reveals how inclusive finance organisations interpret and operationalise the twin transition as an integrated approach to digitalisation and environmental sustainability.

3. Methodology

This study adopts a mixed qualitative methodology, combining a literature review, stakeholder engagement through e-mail interviews (designed and conducted between 2020 and 2021), thematic analysis of the interview data, and a follow-up document analysis (carried out between 2021 and 2025). This design is well-suited to research that seeks to understand how organisations interpret and operationalise complex constructs such as digitalisation, inclusion and environmental sustainability. Comparable qualitative approaches have been used in studies examining how MFIs respond to the pressures of digitalisation (e.g., Siwale & Godfroid, 2022).

3.1. Sampling Strategy and Data Collection

The selection of organisations followed clear inclusion criteria designed to capture the engagement of Europe’s inclusive finance sector with the EU’s twin transition. For inclusion in the sample, organisations had to (1) operate within the EU or its immediate neighbouring ecosystem, (2) be active in inclusive finance, and (3) engage in digitalisation and/or sustainability initiatives. The initial sample was drawn from the European Microfinance Network and expanded through expert recommendations to include fintechs with explicit social or environmental missions. This process resulted in a pool of 50 organisations representing diverse business models, geographic contexts and regulatory environments.

The final sample consists of 26 organisations (Table 1). It includes community-focused MFIs, MSME finance providers, social and green-oriented fintech start-ups and OB platforms, reflecting the diversity of Europe’s inclusive finance landscape and illustrating the different ways organisations adapt to digitalisation, sustainability and policy changes. Non-participation was primarily due to organisations having limited staff availability or organisational restructuring. Potential self-selection bias is acknowledged, and the analysis focuses on thematic patterns rather than statistical generalisation.

Table 1.

Organisations Interviewed.

Data were collected through qualitative e-mail-based interviews. This allowed geographically dispersed organisations to participate asynchronously and allowed respondents to reflect on their answers and consult internal documents before replying; research shows that asynchronous written interviews can enhance reflexivity and generate rich qualitative data by giving participants time to structure their responses (Dahlin, 2021) and supporting access to underlying perceptions, reasoning and interpretive processes (Outhwaite, 1975). Informed consent was obtained from all participants to ensure ethical and confidential engagement.

Each participant received a six-part questionnaire comprising 21 open-ended questions covering (digital) business models, financial inclusion and financial health, environmental sustainability and governance, impact measurement, performance, and the role of national and EU policies. The questionnaire (Table 2) was informed by the literature available at the time of research design (2020). Participants were encouraged to elaborate on strategic priorities, operational mechanisms and policy interpretations, resulting in reflective, detailed responses.

Table 2.

Literature Review for the Interview Questionnaire.

A comprehensive update of the literature was conducted in 2025 to inform the interpretation of the longitudinal findings (2021–2025) and ensure that the analysis reflects the most recent developments in digitalisation and sustainability.

3.2. Data Analysis

The analysis began with a comparative review of questionnaire responses, with particular attention to those related to the (digital) business model. Based on this initial step, key organisational distinctions were identified that informed the development of a three-part typology comprising traditional MFIs, fintech platforms and hybrid models. These emerging distinctions were cross-checked against publicly available organisational information to ensure robustness.

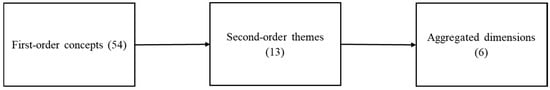

Thematic analysis was conducted to extract insights from the responses (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Clarke & Braun, 2013). This approach is well-suited for identifying emergent patterns in understudied areas, providing a systematic way to interpret meanings across various organisational narratives. A conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) was used to generate initial inductive codes directly from the data. This ensured that early interpretations were grounded in participants’ own language rather than predefined theoretical categories. The analysis was refined and focused through a process of selective coding (Patton, 2002), guided by the six thematic dimensions embedded in the questionnaire (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selective Coding Approach.

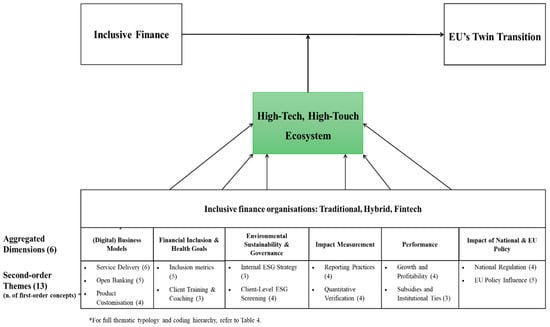

Building on the Gioia methodology (Gioia et al., 2013), the initial codes were reviewed, merged and restructured to identify 54 first-order concepts. These concepts were then grouped into 13 s-order themes, which aligned with the six predefined aggregate dimensions of the study. This process involved repeated movement back and forth between data excerpts, codes and emerging categories to test alternative interpretations and avoid forcing the data to fit preconceived labels. The resulting data structure (Figure 2) and conceptual model (Figure 3) make the analytical pathway explicit by showing how raw material was transformed into higher-order insights into how different institutional types interpret and operationalise the twin transition.

Figure 2.

Data Structure.

Figure 3.

Research Outcomes.

Several complementary strategies were pursued to ensure rigour. First, coding reliability was supported by maintaining a detailed codebook and analytic memos. Second, theme validation drew on triangulation with publicly available organisational information, where relevant. Third, reflexivity was maintained by explicitly acknowledging the researcher’s interpretive role, revisiting earlier coding rounds in light of new insights, and interrogating potential bias in the framing of digitalisation and sustainability. The study adopted a journalistic narrative approach to maintain analytical depth while preserving each respondent’s voice (Magnani & Gioia, 2023). This approach involved paraphrasing participant insights to retain the clarity and essence of their responses while protecting confidentiality. Collectively, these procedures strengthen the credibility and transparency of the analysis and ground the thematic findings presented in Section 4.

Finally, to support a 2021–2025 longitudinal analysis of the findings, the thematic insights generated from the 2020–2021 interviews served as a baseline for the second analytical phase in 2025. The latter phase involved a structured comparison between the interview-derived themes and publicly disclosed organisational information for the period 2021–2025. The longitudinal update was informed by a systematic review of organisational websites and targeted internet searches, complemented by annual reports, impact statements, regulatory filings and official communications. These sources are not cited individually to preserve the anonymity of participating organisations; they were instead used to identify aggregate patterns across the sample. The comparison was organised around three macro-level themes—performance, digitalisation and sustainability—derived from the study’s conceptual framing of the twin transition. This two-stage design facilitated the systematic assessment of continuity and change over time across the three organisational typologies.

4. Findings

The findings draw on a two-stage methodological design: first, a thematic analysis of interviews conducted between 2020 and 2021 (Section 4.1), and second, a 2025 longitudinal comparison using publicly disclosed organisational data covering the period 2021–2025 (Section 4.2).

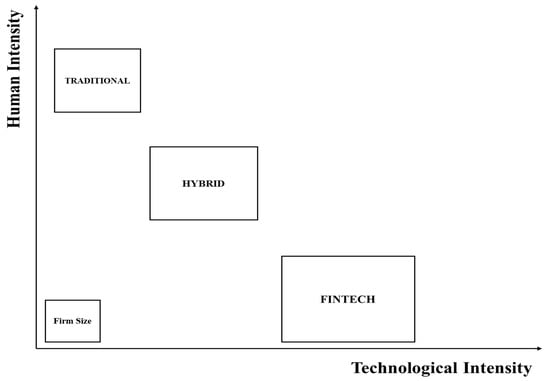

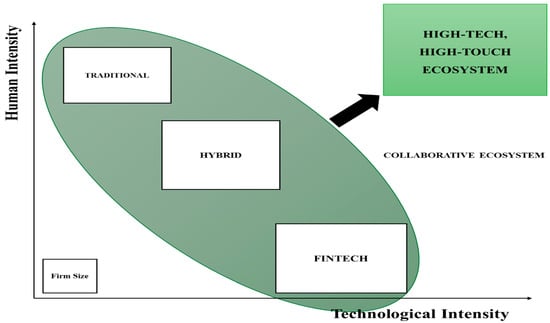

Figure 4 presents a conceptual chart that categorises the three inclusive finance typologies along a continuum of technological and human intensity. This initial typology was validated by cross-checking interview insights with publicly available organisational information, including websites, annual reports and impact disclosures, to ensure consistency across data sources.

Figure 4.

Technological and Human Intensity of Inclusive European Finance Organisations (2020–2021).

Table 3 highlights the composition of the three typologies, classifying the organisations by their corresponding numbers in Table 2.

Table 3.

Composition of the Three Typologies.

4.1. Thematic Analysis of 2021 Interviews by Organisational Typology

Table 4 contains a summary of the thematic analysis of the 2020–2021 interviewees. It describes how each of the organisation typologies has performed within the six investigated key dimensions: (Digital) business models, financial inclusion and health goals, environmental sustainability and governance approach, impact measurement, performance and national and EU policy developments.

Table 4.

Results of the Thematic Analysis (first-order concepts are in italics).

Thematic analysis highlights that Europe’s inclusive finance landscape shows varied responses to the dual pressures of digitalisation and sustainability transitions, evident in the distinct operational profiles of the traditional, hybrid and fintech organisations that participated in this study.

Across Europe, traditional inclusive finance organisations operate primarily with a relational, mission-centric approach. These institutions prioritise human engagement, favouring personal coaching and mentorship over digital tools. Their service models are often limited by regulatory requirements and low digital literacy among their clients, which hinders the feasibility of fully online lending. For example, an MFI from Romania (5) highlights how national know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML) protocols require physical interaction for contract signing. This necessity prevents completely remote onboarding, even when digital channels are available. Other organisations do not offer online loans due to the low digital skills among the population, which requires the essential support of loan officers.

Despite these limitations, traditional MFIs maintain strong social mandates. They often target vulnerable individuals, excluded entrepreneurs and rural communities, taking proactive steps to avoid over-indebtedness and adapting loan structures to suit clients’ irregular income profiles. However, environmental and governance integration, as well as impact measurement, remain underdeveloped within this typology. Many traditional MFIs perceive these activities as outside their scope, citing resource constraints, informal client profiles or misalignment with their core mission. One organisation (12) explained their rationale:

We provide a low amount of money through loans, so we cannot have an impact on the environmental policies of our clients. Furthermore, our clients run paperless businesses (no financial statements, etc.). We should rely on their statements. It would not be a robust solution for measuring our impact. Our indirect inclusion goal could be the formation of formal businesses due to our financial support.

Impact measurement, when available, often relies on qualitative assessments that are typically not systematically validated. Verifying impact is costly and difficult, especially for short-term, low-value loans to informal businesses. Financially, these MFIs tend to demonstrate stable growth trajectories, frequently supported by public subsidies, EU-backed instruments or partnerships with commercial banks. Policy engagement primarily focuses on national issues. A few institutions (e.g., 17) criticise complex microcredit regulation, arguing that it stifles innovation and hinders their path to profitability. Conversely, others (e.g., 7) oppose regulatory gaps that permit exploitative lending practices, underscoring the need for a national policy framework that distinguishes between microfinance providers aiming to create impact and those focused solely on profit.

Engagement with EU-level policy is often indirect. For instance, a Moldovan institution (26) observed that EU digitalisation initiatives, particularly those related to e-signature and compliance simplification, have a noticeable impact on local regulations and business efficiency. Some organisations advocate for customised KYC/AML frameworks that consider low-risk, financially excluded borrowers who may be unable to provide regular income documentation according to standard protocols.

Across Europe, hybrid inclusive finance is increasingly positioned at the intersection of relational depth and digital responsiveness. These organisations often combine high-touch coaching with easy-to-use digital channels, creating onboarding processes that accommodate varying levels of client digital literacy. Some institutions (11, 21) offer multichannel access via mobile apps, automated teller machines (ATMs), phone interviews and in-person sessions, allowing entrepreneurs to engage however suits them.

Digitalisation is not treated as a single entity in this typology. Some providers (e.g., 4) operate extensive national networks that combine thousands of bank branches, online portals and partnerships with civil society organisations to reach underserved clients with varying levels of digital literacy. Instead of forcing complete automation, these organisations selectively automate administrative processes, such as contracting and KYC/AML documentation, while preserving guided acquisition and counselling phases for users who are digitally excluded.

Other hybrid actors (e.g., 3) integrate customised coaching services into their financial offerings. These range from white papers and e-learning modules to personal mentoring and classroom-based training. This layered approach reflects a commitment to tailoring business development support based on individual client profiles, timelines and comfort with technology.

Their inclusion mandate is broad, encompassing entrepreneurs from rural and agricultural backgrounds (18) as well as women- and youth-led businesses (20). However, client-level ESG screening remains minimal, similar to traditional organisations. Some stakeholders (e.g., 8) argue that environmental or governance performance should not be a prerequisite for accessing credit, particularly when clients face urgent livelihood constraints.

Despite this, sustainability and impact reporting are becoming increasingly sophisticated. Large hybrid organisations (e.g., 6) now publish monthly dashboards or annual corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports that include composite indicators, such as loan volumes, disbursement patterns, job creation metrics and social exclusion scores. These frameworks help link financial performance to inclusive outcomes and offer a baseline for evaluating social return on investments (SROIs) across product lines.

Financially, hybrid organisations demonstrate strength and efficiency. Bank-affiliated providers (4, 8) show stable growth and profitability by leveraging robust infrastructure and effective risk management practices. In contrast, organisations not tied to banks secure EU-level guarantees to reduce lending risks and expand operations. Public–private collaborations, especially those supported by EU-backed instruments, play a crucial role, often in areas underserved by commercial banks.

While many hybrid organisations express concerns about fragmented national microfinance regulation, they also advocate for harmonised EU frameworks to enable smoother cross-border operations. One large organisation (19) reports that conflicting banking laws and approaches hinder pan-European service delivery, despite strong support from instruments such as NextGen EU. Additionally, one green organisation (20) emphasises the need for modern microfinance regulation to accelerate sectoral growth, particularly by improving operational revenues tied to indirect business models.

European inclusive fintech platforms occupy the forefront of digital finance, deploying automated credit scoring, cloud-based infrastructure and advanced user interface design to reach underserved users at scale. These platforms frequently utilise behavioural analytics, alternative credit signals and mobile-first onboarding to expedite user acquisition. One global fintech company (1), which provides credit to SMEs and consumers and improves the matching between lenders and creditworthy borrowers, explains its approach:

Our lending platform allows us to underwrite businesses by their cash flow, rather than a traditional credit score. Critically, this underwriting is completely blind to race or gender, allowing for the removal of biases in the lending process. Overall, this has led to our customer base being over-indexed with women, minorities and other SME owners, who may not have had the opportunity to obtain credit through a traditional process.

Client interactions in this typology are almost entirely digitised. Fintechs (2, 14, 25) use application programming interfaces (APIs) and embedded finance protocols to connect users with thousands of financial institutions. This infrastructure enables account aggregation, real-time financial coaching and seamless KYC/AML compliance, often eliminating the need for human engagement. This typology leverages digital dashboards to enhance financial health for underbanked populations. For instance, one fintech company (9) provides customers with insights into their current financial situation on its app to encourage behavioural change.

Despite their digital agility, fintechs demonstrate a patchy approach to ESG integration. For a few of them (16, 14), sustainability governance is driven more by investor requirements or risk mitigation than internal commitment. Environmental data remains sporadic, and platform-level transparency is limited. Although a company (1) recognises the importance of inclusive governance, such as promoting gender-balanced teams and implementing anti-bias protocols in algorithmic scoring, these practices are not systematically enforced across the typology.

Reporting on impact data is inconsistent. Most platforms keep their metrics proprietary, citing competitive sensitivity or the early product maturity (e.g., 13). When independent validation occurs, it is often limited to pilot partnerships or voluntary disclosures. Very few stakeholders have adopted long-term impact frameworks comparable to CSR dashboards used by hybrid organisations. Financially, this typology maintains strong scalability and fundraising capabilities. Several platforms (1, 2, 14) have significantly expanded across EU markets, either through acquisition by large financial institutions or partial ownership by venture capital firms. These fintechs typically prioritise rapid growth over short-term profitability, leveraging deep technological integrations to scale their user base and enhance market valuation.

In terms of policy engagement, fintech organisations demonstrate strong responsiveness to EU-level digital finance initiatives. For instance, a leading OB platform (2) interprets the digital finance strategy as a clear signal of the European Commission’s commitment to advancing financial inclusion and fostering cross-border competition among European businesses. However, these organisations also advocate for stronger regulation on sustainability disclosures and data standardisation, measures that, according to a green fintech (16), are critical to enabling and scaling environmentally oriented business models.

4.2. Longitudinal Analysis of Organisational Change (2021–2025)

The twin transition toward a greener and more digital Europe is reshaping inclusive finance, and the longitudinal analysis reveals how the 26 organisations evolved between 2021 and 2025. Building on the themes identified in the interview phase, this section examines strategic change across the three organisational typologies, focusing on performance, digitalisation and sustainability. Table 5 summarises the main developments observed across the sample.

Table 5.

Developments by Organisation Type (2021–2025).

The findings confirm a gradual but uneven evolution of Europe’s inclusive finance landscape. While organisations are increasingly integrating digital tools and sustainability strategies into their business models, implementation varies significantly across typologies and remains fragmented. Table 6 synthesises this divergence by mapping the dimensional levels (performance, digitalisation and sustainability) achieved in 2021 and tracking the directional trends.

Table 6.

Dimensional Level (2025) and Directional Trend (2021–2025) Achieved by Organisation Type.

Over the past four years, Europe’s inclusive finance institutions have pursued distinct strategies to address digital needs and sustainability demands. These strategies have been shaped by regulatory adaptation, technological advancements, evolving client profiles and cross-sector partnerships.

Traditional MFIs have shown steady growth and financial consolidation (A and + in Table 6). Despite slow adoption of digital innovation (C), several have cautiously integrated digital channels into lending workflows (+). For example, one operator (22) launched express loans for household upgrades and expanded its distribution network through a partnership with a major postal institution. Another organisation (23) introduced cardless withdrawals for microloans via a bank’s ATM network, blending legacy infrastructure with digital outreach. However, progress remains uneven, with some larger organisations yet to expand their digitalisation tools. Digital hybridisation is underway, particularly in onboarding and loan management, though OB implementation is still lacking (+). In terms of sustainability, moderately developed in 2021 (B), traditional MFIs continue to prioritise social inclusion, serving informal entrepreneurs, rural populations and women-led businesses. A small subset is experimenting with green finance: one organisation offers energy-efficiency loans for home renovation (23) or has launched green loans that require no collateral (23), while another (17) provides discounted green loans evaluated by trained loan officers who assess clients’ environmental and social practices during credit analysis. Although ESG integration remains modest, several institutions publish impact reports with metrics on employment, outreach and portfolio indicators, often supported by EU advisory programmes. These developments indicate that while ESG uptake is still evolving, traditional providers are gradually building capacity (+).

Hybrid organisations, combining digital delivery with human-centred coaching, have emerged as anchors in the ecosystem. They are experiencing robust growth and progressing toward profitability by scaling credit services through multichannel, multiproduct platforms (A and +). For example, an Italian hybrid fintech (11) announced it would reach breakeven just three years after obtaining its banking license, driven by a surge in loans and deposits. Others (4, 18) secured EU-backed guarantees under InvestEU to reduce SME portfolio risk and expand inclusive finance. Digitally, progress has plateaued at a moderate stage (B and +/−), reached in 2021. Examples include streamlined mobile onboarding (8), embedded insurance tools developed with a bank (19) and digital lending channels for rural businesses (18). This stagnation highlights the need for targeted policy incentives to accelerate responsible digital innovation across MFIs.

On sustainability, hybrid institutions have gained momentum (+) from a moderate baseline (A). A Romanian organisation (18) published social impact studies with EU support, while others (3, 4) launched online dashboards tracking microloan distribution, job creation, financial inclusion, business survival, coaching outcomes and contributions to national economies. Notably, a large Greek MFI (20) focuses on women-led businesses, supported by government funding offering interest rates well below the market average of 6–10%.

Fintech models, known for rapid scale and automation, continue to lead in digital innovation but show variable engagement with inclusive governance. In 2021, this group demonstrated high digital maturity (A), using full automation, algorithmic credit scoring and AI-driven interfaces to deliver inclusive and environmental financial services. However, their commitment to sustainability was low (C). By 2025, publicly available data reveals mixed trends (+/−) across performance (B), digitalisation (B) and sustainability (C). Several start-ups merged with larger fintechs, expanding digital reach but diluting ESG impact. The only remaining independent fintech (14) continued expanding via venture capital, though it lost over half its valuation. Sustainability integration remains minimal, with few platforms reporting metrics or pursuing impact verification. Overall, while digital inclusion is growing, mission anchoring and accountability frameworks lag. Fintechs risk undermining their role in promoting inclusive finance, as EU digital and sustainability policies increasingly favour blended financial services models that balance innovation with responsibility.

This evolving landscape sets the stage for the strategic implications discussed in Section 5, where this study explores how design choices and policy alignment are shaping the future of inclusive finance in Europe.

5. Discussion

The findings illustrate how Europe’s inclusive finance sector is responding to the EU’s twin transition, which calls for integrated digital and environmental transformation across the economy and society. A longitudinal analysis (2021–2025) reveals strategic complementarity among three institutional typologies. Traditional MFIs offer relational depth and community trust but face challenges with digitalisation and environmental alignment due to regulatory and resource constraints. Fintechs deliver scalability and operational efficiency through technological innovation, but often lack inclusive design and social integration. Hybrid organisations, still consolidating, show promise in merging digital agility with social and environmental goals. These models can act as ecosystem integrators, linking MFIs’ trusted networks with fintechs’ technological capabilities to deliver scalable, sustainable financial services. Figure 5 conceptualises hybrid organisations as central nodes in collaborative ecosystems, facilitating digitally enhanced, inclusive and environmentally sustainable finance.

Figure 5.

Inclusive European Finance Towards a High-Tech, High-Touch Collaborative Ecosystem.

Despite this strategic potential, policy support remains fragmented. Digital finance policies often marginalise inclusive finance organisations, treating them as secondary to financial innovation (Radnejad et al., 2021). Regulatory frameworks, especially KYC and AML, frequently overlook the needs of underserved populations, reinforcing structural barriers to access. MFIs are further constrained by national regulatory heterogeneity and uneven financial services across EU member states.

Robust digital infrastructure is essential for MFIs to enhance social performance (Khanchel et al., 2025; Siwale & Godfroid, 2022), but only larger MFIs with deposit-taking capabilities are positioned to scale (Dorfleitner et al., 2019, 2022). Most lack the resources for digitalisation. However, tailored policy incentives and collaboration frameworks between industry and regulators could unlock new business models through OB and emerging open finance services (De Pascalis, 2022; Preziuso et al., 2023).

A major challenge is Europe’s persistently low levels of digital and financial literacy (European Commission, 2023c; Eurostat, 2024). While some firms are developing literacy-enhancing platforms, coordinated policy incentives remain scarce. To foster long-term engagement and user empowerment, blended delivery models combining digital tools with human interaction are essential.

On the environmental front, sustainability-related financial policies are gaining traction at the EU level. The European Central Bank (2025) has introduced a ‘climate factor’ into its collateral framework to mitigate transition risks and enhance monetary policy resilience, nudging financial institutions towards greener practices.

Market dynamics also reveal strategic shifts. Large organisations are acquiring green fintech start-ups to build scalable business models while awaiting greater standardisation of ESG data and reporting. Inconsistencies in rating methodologies across assessment bodies continue to undermine ESG score credibility, eroding stakeholder trust and complicating alignment with EU sustainability goals (Ding et al., 2024; Jin et al., 2024).

This uncertainty is compounded by recent regulatory changes. The European Commission’s Simplification Omnibus Package has eased compliance for SMEs but narrowed the scope of mandatory frameworks (EY, 2025). As a result, SME-oriented inclusive finance organisations risk exclusion from ESG-aligned value chains unless they voluntarily align with emerging standards. In this context, the Voluntary Sustainability Reporting Standard for SMEs emerges as a critical tool for both reporting and strategic positioning, enabling inclusive finance actors to remain visible, responsive and resilient within the evolving CS3D landscape. In fact, this directive requires large companies to identify and mitigate adverse human rights and environmental impacts across their value chains, with implications for SMEs connected to them.

Inclusive finance organisations are responding, albeit unevenly. Traditional and hybrid models are increasingly offering environmental loans, often driven by pressure from institutional investors and donors, as shown by Forcella and Hudon’s (2016). These organisations are also integrating environmental considerations into decision-making, such as upskilling financial advisors. While EU MFIs are expanding green lending, adoption hurdles persist, including difficulty in developing green financial products and limited client awareness (Botsari et al., 2024). Many organisations still view client-related environmental impact as peripheral to their mission. Yet, if financial inclusion is not integrated into climate strategies, it may inadvertently increase carbon emissions (Le et al., 2020).

EU financial support for the sector’s twin transition remains fragmented, often limited to derisking guarantees, co-financing green and impact loans, or ad hoc digitalisation and reporting programmes. A cohesive policy for digital and sustainability transformation is lacking, underscoring the need for improved regulatory frameworks that foster an inclusive and environmentally oriented, digitally enhanced financial sector (García-Pérez et al., 2018; Le et al., 2020; López-Penabad et al., 2024).

These findings, together with recent studies that highlight inconsistencies in the design of the twin transition and uneven regional funding, underscore the urgent need for coordinated EU-level strategies (Aloisi, 2025; Barbero et al., 2025; Müller et al., 2024). Without an integrated approach, the risk of pursuing digital and green agendas in isolation—‘pushing two agendas separately’—remains (Muench et al., 2022, p. 10).

In this context, regulatory sandboxes offer a pragmatic tool to scale hybrid-led ecosystems. These controlled environments allow policymakers to explore risks and opportunities associated with specific innovations and develop appropriate regulatory responses (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023b; Zetzsche et al., 2018). For example, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority has recently launched a Supercharged Sandbox in partnership with NVIDIA to facilitate safe experimentation with AI (Financial Conduct Authority, 2025).

In the EU, national competent authorities have established 14 financial sandboxes across 12 member states, supported by coordination efforts from the ESAs, namely the European Banking Authority, the European Securities and Markets Authority, and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority, 2023). These bodies have also contributed to EU-wide, sandbox-related initiatives, such as the European Blockchain Sandbox, the Distributed Ledger Technology Pilot Regime and preparatory work for AI regulatory sandboxes under the EU AI Act. Under Article 57 of the Act, each member state is required to establish at least one AI regulatory sandbox by August 2026 (European Commission, 2025e). However, these sandboxes predominantly focus on technical innovation and market efficiency, often overlooking the social and environmental risks of AI-driven digitalisation in financial services (Crawford, 2024; De Vries, 2021; Ganesh et al., 2024; Rohde et al., 2024). More broadly, the success of sandbox initiatives hinges on their embeddedness within dynamic innovation ecosystems and complementary regulatory tools that foster iterative learning and cross-sector collaboration (Buckley et al., 2020). Yet, as Ahern (2021) points out, persistent regulatory fragmentation and institutional inertia across member states continue to impede the EU’s ability to scale inclusive financial innovation, underscoring the importance of coordinated EU-level governance of sandbox initiatives aligned with the Union’s digital finance strategy.

Based on the findings, a proposed ESAs-coordinated, EU-wide regulatory sandbox could serve as a real-world policy instrument for testing and scaling AI-driven financial services that are inclusive, ethical and environmentally sustainable. Member states would lead implementation, while the ESAs would coordinate design and oversight, enabling cross-border learning and policy refinement. This initiative would align inclusive finance with the EU’s twin transition goals and enhance regulatory adaptability to the lived realities of underserved populations. It could also serve as a scalable model for sandbox experimentation in other EU policy areas, with the balance between EU-wide coordination and national execution evolving over time. Persistent financial vulnerability, especially among underbanked populations and SMEs in Southern and Eastern Europe (Botsari et al., 2024; World Savings and Retail Banking Institute & European Savings and Retail Banking Group, 2022), underscores the strategic importance of inclusive finance. Despite the European economy’s reliance on SMEs and microenterprises, many continue to face financial constraints that limit their ability to innovate and grow (Chiappini et al., 2022). Empirical studies confirm that inclusive finance expands credit access, stimulates household spending and encourages MSME development (Bollaert et al., 2021). These dynamics reinforce the need for targeted policy experimentation to unlock inclusive growth.

By incorporating real-world experimentation and principles, the sandbox could help identify the optimal mix of regulatory incentives, safeguards and compliance mechanisms needed to scale financial innovation that is equitable, environmentally sustainable and digitally enhanced across Europe. Given growing concerns about the environmental impact of AI systems, this sandbox could also serve as a testing ground for low-impact AI models and data practices, reinforcing the EU’s commitment to responsible technological development.

6. Limitations and Future Research

The study has several limitations. Its European focus may constrain its broader applicability, and reliance on secondary data limits its depth, particularly with respect to user-level experiences and institutional performance. The technological dimension is treated broadly, without unpacking the specific roles of AI, blockchain or OB. The findings on environmental sustainability remain at a conceptual level due to limited harmonised data on green finance outcomes within inclusive finance. These limitations highlight promising areas for future research. Empirical studies using individual-level quantitative data, such as user surveys, could deepen understanding of how inclusive finance interacts with digital and environmental goals. Comparative research across regions and sectors could also illuminate context-specific challenges and scalable solutions. Further inquiry is needed into how emerging technologies and data governance frameworks can enhance transparency, trust and environmental accountability to shape a globally inclusive and sustainable financial future.

7. Recommendations

The findings highlight several ways in which policy and practice can be strengthened to better align digitalisation, environmental sustainability and financial inclusion in Europe. Greater policy coordination is needed at the EU level to reduce fragmentation in the twin transition and to ensure that inclusive finance organisations are not marginalised in digital finance agendas. Hybrid organisational models that combine technological agility with social and environmental missions should be supported. These offer a promising high-tech, high-touch approach that can be applied across diverse regions. Investment in digital and financial literacy remains essential, particularly in vulnerable areas, so that digitalisation broadens rather than restricts access to financial services. Finally, regulatory sandboxes should integrate social and environmental objectives to support safe experimentation with AI-driven and digitally enhanced financial services that reflect the lived realities of underserved populations.

8. Conclusions

This study contributes to twin-transition scholarship by providing one of the first longitudinal, qualitative analyses of how inclusive finance organisations in Europe are navigating the combined pressures of digitalisation and environmental sustainability. It advances current debates by introducing a tech-touch organisational model and by conceptualising a regulatory sandbox as a mediating structure linking technological innovation with social and environmental objectives. Empirically, the study offers new evidence on institutional complementarities across MFIs, fintechs and hybrid actors, while methodologically it demonstrates the value of integrating thematic analysis with policy-oriented interpretation. The findings directly address the research questions by clarifying how inclusive finance organisations adapt to the twin transition and by identifying the regulatory governance mechanisms needed to support equitable and sustainable innovation.

As Europe advances its twin transition toward digitalisation and environmental sustainability, there are a range of opportunities and challenges in the inclusive finance ecosystem. Traditional MFIs remain anchored in community trust but struggle with digital and environmental integration due to regulatory fragmentation and limited resources. Fintechs offer scalability and innovation, but are often not designed with inclusivity in mind. Hybrid organisations, which blend technological agility with a social mission, are emerging as ecosystem integrators within high-tech, high-touch financial models.

This study advocates a move beyond generic, fragmented policy narratives toward an EU twin transition grounded in the lived realities of underserved populations. It introduces the concept of a regulatory sandbox as a tool for testing incentive structures and compliance mechanisms co-designed with communities to align digital innovation, social inclusion and environmental sustainability.

Regulatory sandboxes are a valuable tool for testing financial innovation, but their impact depends on their integration within broader ecosystems and the coordination of governance. Fragmented national approaches and regulatory inertia continue to limit their potential to support inclusive fintech development across the EU.

A sandbox-driven approach, embedded within broader innovation ecosystems, offers a scalable pathway to inclusive and sustainable finance, particularly in regions such as Southern and Eastern Europe, where financial vulnerability remains high. Inclusive finance plays a pivotal role in bridging social development and economic growth, expanding credit access, stimulating household spending and supporting the resilience of MSMEs.

The sandbox is framed as a mediating structure for the development of a sustainable digital ecosystem. Inclusive finance then becomes a dynamic interface between technological innovation, environmental sustainability and inclusive growth. This foundation supports the proposal for an ESAs-coordinated sandbox for policymakers and practitioners to co-create digitally enabled, sustainability-aligned business models in collaboration with underserved customer groups. Designed at the EU level but implemented through member-state initiatives, its adaptability to sectors facing the dual pressures of digital and green transformation (such as food, health, manufacturing and utilities) enhances its relevance. Given prevailing geopolitical uncertainty and uneven momentum on climate policy, the sandbox model offers a stabilising framework for inclusive finance innovation. By enabling scalable, locally adaptable solutions co-created with underserved groups, it supports inclusive cross-sector transition.

Funding

This paper is part of the Project SFIDE—Strengthening Financial Inclusion through Digitalisation in Europe—a partnership between the University of Twente, the European Microfinance Network (EMN) and Qredits, sponsored by the European Investment Bank Institute (EIB Institute) 2020–22 EIBURS Grant. The funding body had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, as well as in writing or revising the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study received ethical approval from the University of Twente.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and confidentiality and voluntary participation were ensured.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality and privacy reasons, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AML | Anti-money-laundering |

| API | Application programming interface |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ATMs | Automated teller machines |

| CSR | Corporate social responsibility |

| CS3D | Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive |

| CSRD | Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive |

| DFP | Digital Finance Package |

| DIF | Digital inclusive finance |

| ECB | European Central Bank |

| ESG | Environmental, social and governance |

| ESA | European Supervisory Authority |

| EU | European Union |

| fintech | Financial technology |

| KYC | Know-your-customer |

| MSME | Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprise |

| MFI | Microfinance institution |

| OB | Open banking |

| OF | Open finance |

| SME | Small and Medium-sized Enterprise |

| SROI | Social return on investment |

| SDGs | Sustainable development goals |

References

- Ahern, D. (2021). Regulatory lag, regulatory friction and regulatory transition as FinTech disenablers: Calibrating an EU response to the regulatory sandbox phenomenon. European Business Organization Law Review, 22, 395–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allet, M., & Hudon, M. (2015). Green microfinance: Characteristics of microfinance institutions involved in environmental management. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(3), 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloisi, A. (2025). Integrating the EU twin (green and digital) transition? Synergies, tensions and pathways for the future of work. JRC Working Papers Series on Labour, Education and Technology No. 2025/01. European Commission, Joint Research Centre. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/322063/1/1921970855.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Arner, D. W., Buckley, R. P., & Zetzsche, D. A. (2022). Open banking, open data, and open finance. In Open banking (pp. 147–172). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awrey, D., & Macey, J. (2023). The promise & perils of open finance. Yale Journal on Regulation, 40(1), 1–59. Available online: https://www.yalejreg.com/print/the-promise-perils-of-open-finance/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Barbero, J., Collado, L. A., Rodríguez-Crespo, E., & Santos, A. M. (2025). The twin transition in the European Union: Assessing regional patterns of EU-funded investments. European Planning Studies, 33(10), 1801–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, S., Damioli, G., & Ghisetti, C. (2023). The environmental effects of the “twin” green and digital transition in European regions. Environmental & Resource Economics, 84(4), 877–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollaert, H., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Schwienbacher, A. (2021). Fintech and access to finance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 68, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsari, A., Gvetadze, S., & Lang, F. (2024). European small business finance outlook 2024. EIF Working Paper Series No. 2024/101. European Investment Fund. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/313620/1/1919672362.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. P., Arner, D., Veidt, R., & Zetzsche, D. (2020). Building fintech ecosystems: Regulatory sandboxes, innovation hubs and beyond. Washington University Journal of Law and Policy, 61, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappini, R., Montmartin, B., Pommet, S., & Demaria, S. (2022). Can direct innovation subsidies relax SMEs’ financial constraints? Research Policy, 51(5), 104493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist, 26(2), 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo, G. (2024). Open banking goes to Washington: Lessons from the EU on regulatory-driven data sharing regimes. The Computer Law and Security Report, 54, 106018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colangelo, G., & Khandelwal, P. (2025). The many shades of open banking: A comparative analysis of rationales and models. Internet Policy Review, 14(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, K. (2024, February 20). Generative AI’s environmental costs are soaring—And mostly secret. Nature. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00478-x (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Cull, R., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Morduch, J. (2007). Financial performance and outreach: A global analysis of lending microbanks. Economic Journal, 117, F107–F133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, E. (2021). Email interviews: A guide to research design and implementation. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 16094069211025453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, H., Le, P., & Nguyen, D. K. (2025). Financial inclusion and fintech: A state-of-the-art systematic literature review. Financial Innovation, 11(1), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dazeley, R., Vamplew, P., Foale, C., Young, C., Aryal, S., & Cruz, F. (2021). Levels of explainable artificial intelligence for human-aligned conversational explanations. Artificial Intelligence, 299, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A., Pesqué-Cela, V., Altunbas, Y., & Murinde, V. (2020). Fintech, financial inclusion and income inequality: A quantile regression approach. European Journal of Finance, 28(1), 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The global Findex database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the Fintech revolution. World Bank. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/332881525873182837 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- De Pascalis, F. (2022). The journey to open finance: Learning from the open banking movement. European Business Law Review, 33(3), 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, A. (2021). Bitcoin boom: What rising prices mean for the network’s energy consumption. Joule, 5(3), 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X., Sheng, Z., Appolloni, A., Shahzad, M., & Han, S. (2024). Digital transformation, ESG practice, and total factor productivity. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(5), 4547–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfleitner, G., Forcella, D., & Nguyen, Q. A. (2022). The digital transformation of microfinance institutions: An empirical analysis. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 23(2), 454–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfleitner, G., Nguyen, Q. A., & Röhe, M. (2019). Microfinance institutions and the provision of mobile financial services: First empirical evidence. Finance Research Letters, 31, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfleitner, G., Oswald, E. M., & Zhang, R. (2021). From credit risk to social impact: On the funding determinants in interest-free peer-to-peer lending. Journal of Business Ethics, 170(2), 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C., Hu, M., Wang, T., & Kizi, M. D. D. (2024). Research on the impact of digital inclusive finance on green innovation of SMEs. Sustainability, 16(11), 4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Banking Authority. (2025). Consumer trends report 2024–2025. Available online: https://www.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2025-03/514b651f-091b-42d3-b738-1fae79264044/Consumer%20Trends%20Report%202024-2025.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- European Central Bank. (2024). Rapid growth and strategic location: Analysing the rise of FinTechs in the EU. In Financial integration and structure in the Euro area 2024. European Central Bank. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/fie/box/html/ecb.fiebox202406_08.en.html (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- European Central Bank. (2025, July 29). ECB to adapt collateral framework to address climate-related transition risks. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2025/html/ecb.pr250729_1~02d753a029.en.html (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- European Commission. (n.d.). The European green deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- European Commission. (2020a). Recovery plan for Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/recovery-plan-europe_en (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- European Commission. (2020b, September 24). Digital finance package. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/digital-finance-package_en (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- European Commission. (2023a). A European strategy for data. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/strategy-data (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- European Commission. (2023b). Blockchain and web3 strategy. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/blockchain-strategy (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- European Commission. (2023c, July 18). Eurobarometer survey reveals low levels of financial literacy across the EU. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/news/eurobarometer-survey-reveals-low-levels-financial-literacy-across-eu-2023-07-18_en (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- European Commission. (2025a). Flash Eurobarometer 559: Startups, scaleups and entrepreneurship. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2025b, April 1). Omnibus package. Available online: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/news/omnibus-package-2025-04-01_en (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- European Commission. (2025c, April 9). AI continent action plan. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/factpages/ai-continent-action-plan (accessed on 30 October 2025).