Abstract

This paper examines an optimal investment–consumption problem in a setting where the financial environment is influenced by both stochastic factors and delayed effects. The investor, endowed with Constant Relative Risk Aversion (CRRA) preferences, allocates wealth between a risk-free asset and a single risky asset. The short rate follows a Vasček-type term structure model, while the risky asset price dynamics are driven by a delayed Heston specification whose variance process evolves according to a Cox–Ingersoll–Ross (CIR) diffusion. Delayed dependence in the wealth dynamics is incorporated through two auxiliary variables that summarize past wealth trajectories, enabling us to recast the naturally infinite-dimensional delay problem into a finite-dimensional Markovian framework. Using Bellman’s dynamic programming principle, we derive the associated Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) partial differential equation and demonstrate that it generalizes the classical Merton formulation to simultaneously accommodate delay, stochastic interest rates, stochastic volatility, and consumption. Under CRRA utility, we obtain closed-form expressions for the value function and the optimal feedback controls. Numerical illustrations highlight how delay and market parameters impact optimal portfolio allocation and consumption policies.

1. Introduction

The continuous-time portfolio selection and consumption framework of Merton (1969, 1971) established stochastic control as a central methodology in mathematical finance. In the Merton setting, an investor with intertemporal preferences chooses dynamic portfolio and consumption strategies to maximize expected utility over time. The canonical model, however, relies on a relatively simple Markovian structure in which decisions depend solely on current state variables, such as current wealth and asset prices.

Over the past decades, many extensions have introduced richer sources of risk and incompleteness. Examples include stochastic interest rates, stochastic volatility, incomplete markets, transaction costs, and constraints. Nevertheless, a large portion of the literature preserves the Markovian assumption and does not incorporate explicit dependence on historical paths of the wealth or price processes. In practice, however, economic and financial systems often exhibit memory: policy decisions are implemented with delay, investors respond gradually to accumulated performance, and macroeconomic shocks propagate over time with persistence.

In parallel, there is strong empirical evidence that both interest rates and volatility fluctuate stochastically and exhibit mean-reverting behavior. Models such as Vasček-type short-rate processes for interest rates and CIR-type dynamics for volatility have become standard tools in term-structure modeling and option pricing. Combining such stochastic factors with intertemporal portfolio choice leads to more realistic, but also more complex, optimization problems.

The aim of this paper is to develop and analyze a portfolio optimization and consumption model that simultaneously accounts for (i) stochastic interest rates; (ii) stochastic volatility in the risky asset; and (iii) delay effects in the wealth dynamics.

We consider a CRRA investor trading continuously in a financial market consisting of one risk-free asset and one risky security. The short rate follows a Vasček model, while the risky asset price is driven by a Heston-type stochastic volatility process, whose variance follows a CIR diffusion. The decision to model the short rate as aVasček process is based on its analytically tractable nature, which led to closed-form solutions for the HJB equations. Furthermore, the Vasček model captures the essential mean-reverting behaviour of interest rates while keeping the process linear and Gaussian, which simplifies both the dynamic programming and numerical analysis. Alternatively, the Cox–Ingersoll–Ross (CIR) process could also be adopted, but its square-root diffusion term introduces additional nonlinearities that make it difficult to obtain closed-form solutions. For this reason, the Vasček specification is adopted here as a balance between realism and tractability.

Delay is introduced through two auxiliary wealth-dependent variables: a smoothed average of historical wealth, denoted by , and a pointwise delayed wealth term, denoted by . These quantities are designed so that the resulting state process remains finite-dimensional, despite the presence of memory. The wealth process is governed by a stochastic delay differential equation (SDDE) in which both the current and delayed wealth components determine the drift. Direct analysis of SDDEs typically leads to infinite-dimensional state spaces. Here, by choosing the delay variables appropriately and imposing a structural condition linking model parameters, we obtain an equivalent representation in a finite-dimensional Markovian state space. This allows us to use the dynamic programming principle and derive the associated Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation.

Our contribution is twofold. First, at the modeling level, we propose a unified continuous-time investment–consumption problem that incorporates delay, stochastic interest rates, and stochastic volatility in a consistent and tractable framework. Second, at the analytical level, we derive explicit expressions for the value function and the optimal controls under CRRA preferences, relying on transformations that reduce the HJB PDE to a solvable form. We also highlight how the delay terms interact with the stochastic factors and discuss their impact on optimal strategies.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature on portfolio optimization with delay and stochastic factors. Section 3 presents the financial market, the wealth dynamics with delay, and the investor’s optimization problem. Section 4 develops the HJB equation, the associated transformations, and the derivation of the value function. Section 5 provides numerical illustrations and simulations examining the role of delay and parameter changes. Section 6 concludes and discusses possible extensions.

2. Related Literature

Merton’s classical contributions Merton (1969, 1971) form the benchmark for continuous-time portfolio and consumption optimization. Subsequent research has extended this framework along several dimensions. One important direction introduces delay into the dynamics. For example, Chunxiang and Shao (2017) study a portfolio optimization problem with delay in which the risky asset follows a CIR process, but consumption is not considered. L. Elsanosi and Larssen (2001) examine an optimal consumption problem under partial observation in a delayed stochastic system; in their setting, wealth evolves according to a stochastic delay differential equation, and they obtain closed-form expressions for policies and value functions under suitable specifications.

Other works explore delayed dependence in wealth or control systems using dynamic programming and maximum principle techniques. M. H. Chang et al. (2011) investigate an investment–consumption model with bounded memory, whereas Larssen (2002) develops dynamic programming methods for systems with delay and noise. I. Elsanosi et al. (2000) and M. H. Chang et al. (2008) derive stochastic maximum principles and explicit solutions for certain classes of control problems with delay. Functional Itô calculus and related tools have been applied to delayed portfolio problems by Pang and Hussain (2015, 2016), who work with bounded memory and infinite horizon formulations. Further contributions by Federico (2011); Federico et al. (2010) study delay in the context of state constraints and pension fund models, respectively. Memory effects in control problems have also been analyzed in advertising and economics; see, for instance, Gozzi and Marinelli (2006) and Gozzi et al. (2009).

Another branch of the literature focuses on stochastic interest rates and stochastic volatility in portfolio problems. H. Chang et al. (2013) consider optimal investment and consumption in a setting where the short rate follows a Ho–Lee model. Korn and Kraft (2002) and Li and Wu (2009) analyze models in which both the short rate and volatility are stochastic. Kraft (2005) obtains an explicit solution for optimal portfolios under the Heston stochastic volatility model and power utility, while J. Liu (2007) studies portfolio selection in general stochastic environments with diffusion-driven factors. Related contributions by Zariphopoulou (1999, 2001), Fleming and Hernández-Hernández (2003), and Fouque et al. (2000) examine optimal investment under unhedgeable or stochastic volatility risk and develop asymptotic and PDE-based solution methods. Z. Liu et al. (2024) investigated the optimal investment strategy for a defined contribution pension plan under stochastic salary dynamics and a Value-at-Risk constraint within a stochastic volatility framework. This study extended the classical Merton models to real stochastic environments. Bei et al. (2024) analysed an optimal reinsurance investment problem under stochastic volatility and stochastic interest rates, demonstrating how joint financial and insurance risks can be optimally managed within a unified stochastic control setting. Ma et al. (2023) considered optimal consumption and investment under the 4/2-CIR stochastic hybrid model, which generalizes the widely used Heston and 3/2 models. Results showed that richer volatility dynamics significantly affect optimal strategies. Cheng and Escobar-Anel (2023) consider robust portfolio choice and consumption under the 3/2 and 4/2 stochastic volatility models, addressing realistic model uncertainty and robustness, which is a key issue in financial decision-making.

The present paper lies at the intersection of these strands. To the best of our knowledge, there are comparatively few studies that integrate delay, stochastic interest rates, stochastic volatility, and consumption in a single continuous-time Markovian framework that admits explicit solutions. Our work contributes to filling this gap by formulating such a model, deriving the corresponding HJB equation, and obtaining closed-form expressions for the value function and optimal feedback controls in a delayed Heston–Vasček environment.

3. Problem Formulation

We consider a continuous-time financial market defined on the interval , where denotes the terminal time. The underlying probability space is assumed to be complete, and the filtration satisfies the usual hypotheses of right-continuity and -completeness.

3.1. The Financial Market Model

The investor trades in two securities: a risk-free asset and a single risky asset. The risk-free asset may be interpreted as a money market account or a discount bond, and the risky asset as a stock or stock index. To incorporate memory, we introduce two delay variables driven by the wealth process :

and

where is the decay rate of the memory kernel (recent wealth has a greater influence) and denotes the delay horizon. The variable summarizes a weighted history of wealth over , while captures a single lagged realization of wealth.

Working with delay variables of the form (1) and (2) allows us to incorporate memory effects in a way that is still compatible with a finite-dimensional Markovian representation. If we were instead to treat the full past trajectory as part of the state, the problem would naturally become infinite-dimensional, typically precluding an explicit solution. Consequently, our focus is on formulations in which the wealth dynamics depend on the delayed processes and , but not directly on the entire path.

Let denote the value of the risk-free asset at time t. Its dynamics are given by

where is the short rate, modeled by a Vasček-type process:

Here represents the instantaneous mean drift of the short rate, is a constant volatility parameter, and is a one-dimensional standard Brownian motion. We assume that the drift can be written in mean-reverting form as , with constants .

Let denote the price of the risky asset. Its dynamics are specified by a delayed Heston-type model:

where is the stochastic variance process, are constants scaling the impact of the delay variables, and is a one-dimensional Brownian motion. The term governs the excess return from exposure to volatility, while determines the sensitivity of the risky asset to shocks in .

The variance process follows a CIR diffusion:

where , , and are constants. The process is a one-dimensional Brownian motion, possibly correlated with , and we impose for all . The Brownian motions are defined on the same filtered probability space with correlation coefficient between and such that

3.2. The Wealth Model

Let denote the investor’s total wealth at time t. The investor consumes at an instantaneous rate and represents the amount invested in the risky security, with the remainder allocated to the risk-free security. To keep notation simple, we do not explicitly track the amount in the risk-free asset, writing only when needed to emphasize the allocation. Trading occurs continuously in time, and the strategy is assumed to be self-financing.

Under these assumptions, the wealth dynamics (in the additive -terms case) satisfy

for , with initial history

The delay processes are given by

3.3. The Optimization Criterion

We now define admissible controls and the investor’s optimization objective.

Definition 1.

A control pair is called admissible if it satisfies:

- (i)

- and are progressively -measurable, and

- (ii)

- for all t, and is admissible as a portfolio weight.

- (iii)

- The stochastic integral is square-integrable:

- (iv)

- There exists a constant such thatfor all .

- (v)

- For each admissible pair , the wealth SDDE (8) admits a unique pathwise solution.

The investor’s preferences are modeled by a CRRA utility specification. Let and denote the utility from consumption and terminal wealth, respectively. We assume is twice continuously differentiable, strictly increasing, and strictly concave; that is, and . The subjective discount factor is , and the constant determines the relative weight assigned to intermediate consumption versus terminal wealth. Expectations are taken under the physical measure .

The investor’s goal is to allocate initial wealth between the risk-free and risky assets and to choose a consumption path so as to maximize expected discounted utility of consumption and terminal wealth. The optimization problem is

subject to the wealth and factor dynamics:

and

Definition 2.

The value function associated with the control problem is defined by

where and satisfy the usual CRRA conditions and , and λ and ϕ denote the discount rate and the relative weight on consumption, respectively.

4. The Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman PDE

The optimal control problem described above can be analyzed via dynamic programming. In particular, Bellman’s principle of optimality leads to a Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation for the value function. The structure of the HJB equation reflects both the diffusion terms and the delay variables, which enter through the state and the relation between and .

Using the delayed Itô formula presented in Appendix A (Lemma A1), the HJB PDE associated with the value function (13) is given by the nonlinear second-order equation

where subscripts denote partial derivatives of V.

Remark 1.

Note that despite the value function in (13) being expressed as , the delayed variable appears in the HJB equation via the dynamics of , implying its appearance in (14) reflects this indirect influence. However, the subsequent structural restriction removes explicit dependence on z, so that the value function depends only on . Furthermore, and in the HJB equation should not be treated as a duplication. is obtained by differentiating the exponential discount factor in the value function (13), while the explicit factor ensures temporal weighting of instantaneous utility. Thus, the two terms are mathematically consistent.

The first-order conditions for optimality, obtained by differentiating the Hamiltonian with respect to and , yield the candidate optimal controls

and

where is strictly decreasing and therefore invertible.

Substituting (15) and (16) into the HJB Equation (14) leads, after simplification, to

with terminal condition

Rearranging terms, we obtain the more compact representation

subject to

In the following section, we exploit CRRA preferences to transform and solve the HJB Equation (19).

4.1. Optimal Policies and the Value Function

We assume the investor’s preferences are represented by a CRRA (power) utility function.

4.2. Power Utility Function

Definition 3.

The power utility specification is

where δ is the risk-aversion parameter.

Remark 2.

To obtain an explicit solution for the HJB PDE (19) in a finite-dimensional setting, we require that the value function be independent of z. This motivates an appropriate change of variables and a structural condition on the parameters.

To eliminate dependence on z, we set

This transformation absorbs the delayed term into a combined state variable u, thereby simplifying the PDE. We also postulate a separable form for the value function:

The unknown function encodes the effect of the stochastic factors and time t.

The relevant derivatives of V are

Under CRRA preferences, the optimal consumption control implied by (16) takes the form

Substituting (24) and (25) into (19) yields an equation for g:

To ensure that the reduced problem remains finite-dimensional, we impose the parameter restriction

Remark 3.

Condition (27) guarantees that the HJB Equation (19) can be solved in a finite-dimensional state space by removing explicit dependence on the lagged variable z. It is a modeling restriction rather than an identity that should hold for every possible realization of . It is imposed at the level of model parameters (the mean or long-run value of ) to make the problem analytically tractable while preserving the qualitative behavior of the model. This is a key modeling assumption that permits the delay structure to be summarized by the transformed state variable u.

To further simplify, we introduce the transformation

The derivatives of g in terms of f are

Substituting (31) into (29) and simplifying, we arrive at the PDE

Remark 4.

The constant term in (32) complicates a direct solution. Following the approach in J. Liu (2007), we relate (32) to an auxiliary PDE for a modified function , which admits a more tractable representation. This transformation is described in Appendix B.

Appendix B (Lemma A2) shows that Equation (32) is equivalent, under an appropriate integral representation, to the PDE

with boundary condition .

5. Numerical Examples

In this section, we provide numerical illustrations of the optimal investment and consumption strategies and examine how they respond to changes in the delay term and other parameters.

5.1. Effects of Delay on Optimal Investment and Consumption

We first investigate how the delay variable influences the optimal portfolio weight and the optimal consumption . From the explicit formulas for the feedback controls, one obtains

and hence

Similarly, for the consumption control,

so that

In summary,

- (i)

- When , neither the optimal portfolio weight nor the optimal consumption depends on the delay variable . In this case, the investor behaves as if there were no delay.

- (ii)

- When , both and increase with . Intuitively, a higher history of wealth performance makes the investor more willing to expand the risky position and to consume more.

- (iii)

- When , the delay variable has an adverse effect: larger historical wealth (in the sense captured by ) leads to a reduction in both the risky allocation and consumption.

5.2. Simulations

We now perform simulations to illustrate how various parameters influence the optimal portfolio strategy. Throughout the numerical experiments, the parameters are chosen as follows:

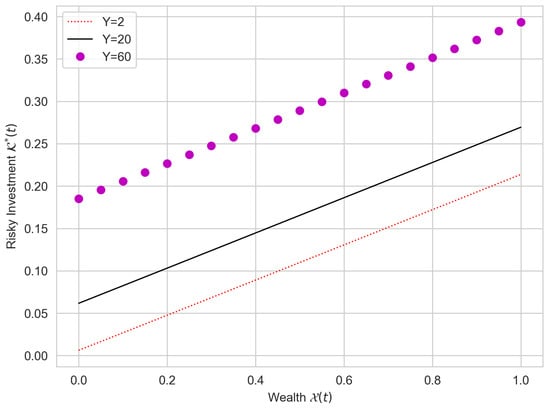

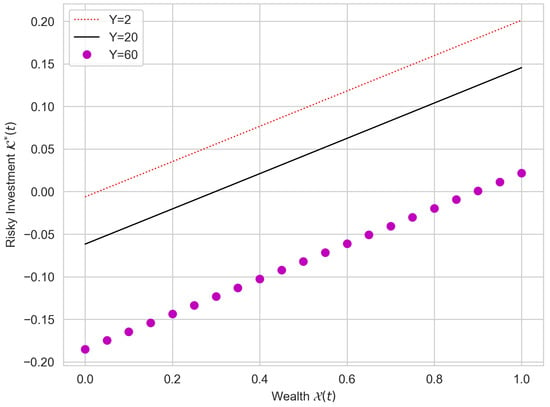

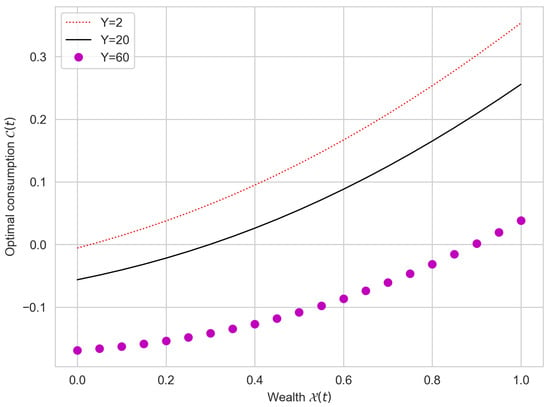

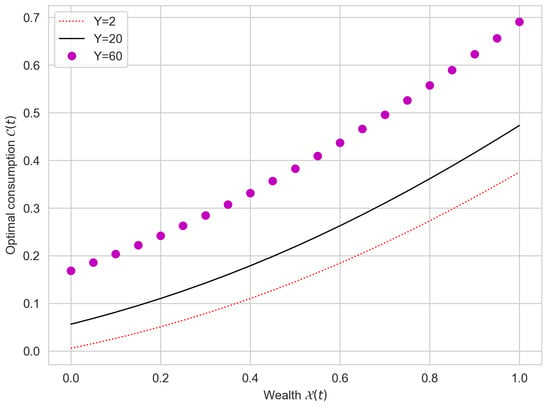

Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 display the relationships between wealth, optimal portfolio weights, and optimal consumption under different model configurations, including correlation coefficients and . The results indicate that an improvement in historical wealth performance generally leads to a higher optimal allocation to the risky asset, consistent with greater risk-taking when the investor has “good history” in terms of accumulated wealth. This pattern is robust across the sign of and across the considered parameter values.

Figure 1.

Optimal risky investment versus wealth for under a positive delay contribution.

Figure 2.

Optimal risky investment versus wealth for under a negative delay contribution.

Figure 3.

Optimal consumption versus wealth for under a negative delay contribution.

Figure 4.

Optimal consumption versus wealth for under a positive delay contribution.

The correlation parameter plays a central role in shaping the behavior of the optimal strategy. When , shocks to the asset price and variance are perfectly positively correlated, reinforcing volatility shocks and affecting the optimal hedge component in . Conversely, when , the negative correlation dampens certain risk components, leading to different portfolio responses. Overall, the simulations illustrate how the interaction of delay, stochastic volatility, and correlation can materially alter the investor’s optimal policies.

6. Conclusions

This paper extends the classical Merton framework by studying an optimal investment–consumption problem in a financial market with stochastic interest rates, stochastic volatility, and delay in the wealth dynamics. The short rate evolves according to a Vasček model, while the risky asset is driven by a delayed Heston specification with CIR variance. Memory effects are captured through delay variables that depend on past wealth, and the problem is formulated in such a way that the state space remains finite-dimensional.

Using Bellman’s dynamic programming principle, we derive the HJB equation associated with the optimization problem and obtain an explicit solution under CRRA preferences. The resulting value function and optimal feedback controls are characterized in closed form, subject to a mild structural condition that eliminates explicit dependence on the lag variable z. The analysis highlights how historical wealth performance, encoded through the delay terms, influences both portfolio choice and consumption, and how these effects interact with the stochastic interest rate and volatility dynamics.

Our numerical experiments show that higher historical wealth performance tends to increase both the optimal investment in the risky asset and the consumption rate, especially when the parameter is positive. The correlation between asset returns and volatility plays a key role in determining the sensitivity of the optimal strategies to shocks in the variance process.

Several extensions of this work are possible. For example, one could consider extending the model to include a jump in the dynamics of risky assets. Furthermore, multiple risky assets with correlated returns and volatility factors incorporate transaction costs or portfolio constraints, or explore alternative specifications of delay in the asset price dynamics considered. Such generalizations would likely lead to more complex HJB equations but could provide further insights into optimal portfolio behavior in realistic, memory-dependent financial markets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J., D.M., and E.M.; methodology, S.A.G. and S.J.; software, D.M. and E.M.; validation, S.A.G.; formal analysis, S.J., D.M. and E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J., D.M. and E.M.; writing—review and editing, S.A.G.; visualization, S.J., D.M., and E.M.; supervision, S.A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The study is based on simulated data; no empirical datasets were used.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by the Faculty of Science at Toronto Metropolitan University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Delayed Itô Formula

Lemma A1.

Let and define . Then

where

and

Proof.

To derive the HJB PDE in a finite-dimensional state space, we first compute the dynamics of the delay variable . Using the definition

we apply the Leibniz rule:

Hence,

Since , an application of the classical Itô formula yields

This expression yields the claimed formula. □

Appendix B. Transformation of PDE (32)

Lemma A2.

Assume that f of the form

solves (32). Then satisfies the PDE

with boundary condition .

Proof.

We introduce the differential operator acting on a smooth function by

Then (32) can be written concisely as

with terminal condition

Appendix C. Solution of PDE (33)

Theorem A1.

Suppose is continuously differentiable in t and twice continuously differentiable in for all and . Then the solution of the HJB PDE (14) can be written as

where , , and are deterministic functions determined by a system of ordinary differential equations. Furthermore, if the utility function is given by (21) and the transformations (23) and (30) hold, then the feedback controls

and

are optimal.

Proof.

We sketch the main steps; detailed computations are included in the derivations preceding this theorem. We look for a solution to (A7) of exponential–quadratic form:

with terminal conditions so that .

From (A17), the derivatives are

Substituting (A18) into (A7), we factor out and equate the coefficients of , r, and the constant term. This yields a system of ordinary differential equations for , , and . After collecting terms, we obtain

and

Equation (A20) integrates explicitly to

The equation for in (A19) is a Riccati equation. Writing it in a standard form and analyzing the discriminant, we impose conditions on ensuring real solutions. Integrating from t to T with the boundary condition yields

where and are the distinct roots of the quadratic polynomial associated with the Riccati equation.

Finally, is obtained by integrating (A21):

References

- Bei, H., Wang, Q., Wang, Y., Wang, W., & Murcio, R. (2023). Optimal reinsurance–investment strategy based on stochastic volatility and the stochastic interest rate model. Axioms, 12, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H., Rong, X., & Zhao, H. (2013). Optimal investment and consumption decisions under the Ho–Lee interest rate model. WSEAS Transactions on Mathematics, 12, 2224–2880. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M. H., Pang, T., & Pemy, M. (2008). Optimal control of stochastic functional differential equations with bounded memory. Stochastics, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M. H., Pang, T., & Yang, Y. P. (2011). A stochastic portfolio optimization model with bounded memory. Mathematics of Operations Research, 36, 604–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y., & Escobar-Anel, M. (2023). Optimal consumption and robust portfolio choice for the 3/2 and 4/2 stochastic volatility models. Mathematics, 11, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunxiang, A., & Shao, Y. (2017). Portfolio optimization problem with delay under Cox–Ingersoll–Ross model. Journal of Mathematical Finance, 7, 699–717. [Google Scholar]

- Elsanosi, I., Øksendal, B., & Sulem, A. (2000). Some solvable stochastic control problems with delay. Stochastics: An International Journal of Probability and Stochastic Processes, 71, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsanosi, L., & Larssen, B. (2001). Optimal consumption under partial observations for a stochastic system with delay (Preprint No. 9). University of Oslo. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, S. (2011). A stochastic control problem with delay arising in a pension fund model. Finance and Stochastics, 15, 421–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, S., Goldys, B., & Gozzi, F. (2010). HJB equations for the optimal control of differential equations with delays and state constraints: Regularity of viscosity solutions. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization, 48, 4910–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, W., & Hernández-Hernández, D. (2003). An optimal consumption model with stochastic volatility. Finance and Stochastics, 7, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouque, J. P., Papanicolaou, G., & Sircar, K. R. (2000). Derivatives in financial markets with stochastic volatility. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gozzi, F., & Marinelli, C. (2006). Stochastic optimal control of delay equations arising in advertising models. In Stochastic partial differential equations and applications VII. Lecture Notes in Pure and Applied Mathematics. Chapman & Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Gozzi, F., Marinelli, C., & Savin, S. (2009). On controlled linear diffusion with delay in a model of optimal advertising under uncertainty with memory effects. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications, 142, 291–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, R., & Kraft, H. (2002). A stochastic control approach to portfolio problems with stochastic interest rates. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization, 40, 1250–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, H. (2005). Optimal portfolios and Heston’s stochastic volatility model: An explicit solution for power utility. Quantitative Finance, 5(3), 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larssen, B. (2002). Dynamic programming in stochastic control of systems with delay. Stochastics: An International Journal of Probability and Stochastic Processes, 74, 651–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., & Wu, R. (2009). Optimal investment problem with stochastic interest rate and stochastic volatility: Maximizing a power utility. Applied Stochastic Models in Business and Industry, 25, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. (2007). Portfolio selection in stochastic environments. Review of Financial Studies, 20, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Zhang, H., Wang, Y., & Huang, Y. (2024). Optimal investment strategy for DC pension plan with stochastic salary and value at risk constraint in stochastic volatility model. Axioms, 13, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A., Zhang, C., & Wang, Y. (2023). Optimal consumption and investment problem under 4/2-CIR stochastic hybrid model. Mathematics, 11, 3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R. C. (1969). Lifetime portfolio selection under uncertainty: The continuous-time case. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 51(3), 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R. C. (1971). Optimum consumption and portfolio rules in a continuous-time model. Journal of Economic Theory, 3, 373–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, T., & Hussain, A. (2015, July 8–10). An application of functional Itô formula to stochastic portfolio optimization with bounded memory. SIAM Conference on Control and Its Applications, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, T., & Hussain, A. (2016). An infinite time horizon portfolio optimization model with delays. Mathematical Control and Related Fields, 6, 629–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zariphopoulou, T. (1999). Optimal investment and consumption models with non-linear stock dynamics. Mathematical Methods of Operations Research, 50, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zariphopoulou, T. (2001). A solution approach to valuation with unhedgeable risks. Finance and Stochastics, 5, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.