Abstract

This study investigates the volatility dynamics of the Bahrain All Share Index (BAX) between 2010 and 2025, a period marked by COVID-19 and regional geopolitical shocks. Using ARMA (1,1) to model returns and four GARCH-family models (ARCH, GARCH, EGARCH, GJR-GARCH) to capture volatility, we provide new evidence from a bank-based frontier market that has received limited empirical attention. The results reveal that returns are stationary and exhibit volatility clustering. Among the competing models, EGARCH (1,1) provides the best fit—exhibiting the lowest AIC and SIC values and the highest log-likelihood—revealing a significant leverage effect whereby negative shocks generate stronger volatility than positive shocks. This asymmetric volatility pattern contradicts earlier findings for Bahrain but aligns with theoretical expectations for bank-based financial systems. The findings carry implications for investors in terms of portfolio risk management, derivative pricing, and asset allocation. They also have important implications for regulators and policymakers, suggesting that counter-cyclical buffers and interest rate adjustments could be applied to stabilize the market in anticipation of negative shocks. These insights enrich the scarce literature on volatility in small frontier markets and contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the volatility dynamics in the MENA region.

1. Introduction

Modelling financial market volatility plays a crucial role in financial economics, given its impact on risk management, asset pricing, and portfolio optimization. Following the seminal work of Harry Markowitz (1952) on portfolio selection amid uncertainties, researchers have sought to understand how to measure volatility. A milestone in this field was Black’s recognition that stock returns exhibit a leverage effect. More precisely, a drop in the firm’s stock price leads to an increase in its financial leverage, thereby increasing the volatility of the firm’s equity (Black, 1976). Black’s finding was empirically supported by Christie (1982), who reported an inverse relationship between stock returns and volatility.

Empirically, the majority of the evidence on the leverage effect came from developed markets. Bats and Houben (2017) proposed that the leverage effect should be higher in bank-based systems. They postulated that bank-based systems have higher systematic risk, as shocks are transmitted between banks via the lending networks, causing the impact of negative news on volatility to be more intense.

The impact of the bank or market-based system might be more distinctive when the degree of the market development is taken into account. Modelling volatility and examining the leverage effect in developing markets has received little attention from researchers.

The Bahrain Bourse (BHB), the primary stock exchange in Bahrain, was launched in 1989. The Bourse makes a significant contribution to the financial system, with the banking sector contributing to more than 58% of the market capitalization (Central Bank of Bahrain, 2025). The Bahrain All Share Index (BAX), also known as Estirad, is the main index of the Bahrain Bourse. It is a value-weighted index comprising 41 firms (CEIC Data, n.d.). The BAX peaked in 2008 only to experience a significant downturn in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. The BAX exhibited more volatility between 2014 and 2020 as a result of oil price fluctuations and the COVID-19 pandemic (Trading Economics, n.d.).

As a bank-based system and a standalone/frontier market, Bahrain provides a rich environment for examining volatility dynamics.1 Nevertheless, this market appears to be under-investigated. In their analyses of the Bahraini market, Mohamad (2020) and Haji (2021) reported that no leverage effect was detected in the BAX during earlier periods—contrary to theoretical expectations for bank-based systems. These findings motivate a re-examination, over an extended period, that includes major shocks.

This paper contributes to the literature in two ways:

- It extends the previous research by applying the GARCH family to model the volatility dynamics of the BAX in a period characterized by significant exogenous shocks (COVID-19 and the latest geopolitical instabilities).

- It provides new evidence from a bank-based system in a country with a standalone/frontier market, enhancing the research on volatility on the MENA region.

The aim of this paper is to apply the GARCH family to model the volatility dynamics of the BAX between 2010 and 2025. This time span enables us to account for the post-financial-crisis period including the COVID-19 pandemic, its recovery phase, and recent geopolitical tension in the region.

As the time span in question covers multiple phases of market shocks and their aftermath, the presence of such shocks raises concerns about structural breaks and volatility regime changes. Although standard GARCH models do not explicitly model regime shifts, several considerations justify their use in this context. First, GARCH models play the role of a benchmark against which more sophisticated models are compared. Second, the empirical application of GARCH models in developed and developing countries has constantly resulted in robust estimates of volatility clustering and leverage effects (e.g., Aloui, 2017; Hansen & Lunde, 2011). Third, since the Bahraini market has modest trading volumes and limited liquidity, the estimation of regime-switching or latent volatility models—which typically require high-frequency data and deep markets (Bauwens et al., 2010; Hansen et al., 2012)—could provide less reliable results and is computationally cumbersome.

The findings of the paper confirm that the BAX returns are stationary and demonstrate volatility clustering. Among the models examined, the EGARCH model seems to be the best fit for the data, indicating the presence of a leverage effect in which negative shocks have more impact on volatility than positive ones. The findings are inconsistent with that of Mohamad (2020) and Haji (2021), who failed to detect a leverage effect in the Bahraini market, but consistent with those of Aloui (2017) and with the proposition by Bats and Houben (2017), regarding a greater leverage effect in bank-based systems.

Despite the popularity of the current approach and how convincing it is—applying GARCH-family models—we acknowledge that its inability to capture structural breaks constitutes a limitation of the current study. While informative, the findings are shaped by the limitations inherent in the modelling approach.

2. A Review of the Literature

2.1. Theoretical Evolution of Volatilities Models

Volatility modelling advanced significantly with the introduction of the Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (ARCH) model by Engle (1982), which was pivotal in capturing the time-varying nature of the variance. Despite its innovation, the model failed to account for long-term volatility persistence. This shortcoming was addressed by Bollerslev (1986), who extended the ARCH into the Generalized ARCH (known as GARCH) model by adding lagged variances. This addition enabled the model to capture not only short-term shocks but also long-term volatility persistence with fewer variables. Extended versions of the GARCH model, such as the Exponential GARCH (EGARCH) by Nelson (1991) and the GJR-GARCH by Glosten et al. (1993), were developed later to account for the leverage effect. These models, known as the GARCH family, became a cornerstone in volatility modelling. Despite their popularity in modelling financial market volatility, GARCH models are based on the assumption that volatility is a deterministic function. However, this limits their ability to capture more complex market behaviours. This led to the development of alternative approaches that model volatility as a stochastic process, allowing for greater flexibility and realism. In his stochastic volatility model, Heston (1993) treated volatility as a random process with mean reversion. Although the Heston model is better able to capture the market dynamic compared to GARCH models, its estimation is more complex and performs better on high-frequency data. Building on this, it is important to recognize that during periods of economic turbulence, policy shifts, or financial crises, market behaviour can change abruptly. Accordingly, traditional GARCH models that treat volatility as a single, stable process over the sample period may fail to capture these regime-dependent shifts, causing a misestimation of risk and reduced forecasting accuracy. To address this limitation, Bauwens et al. (2010) introduced a framework in which both the conditional mean and variance are allowed to change across unobserved regimes. Although the regimes are not directly observed in the model, they are inferred through a hidden Markov process. A parallel line of advancement focused on incorporating high-frequency data to enhance forecasting precision. The Realized GARCH model, developed by Hansen et al. (2012), employed the Quasi-Maximum Likelihood-Kernel (QML-K) method to estimate the returns’ density function. The model enables the joint modelling of asset returns and realized volatility extracted from high-frequency data. The Realized GARCH framework captures more granular market information and enhances responsiveness to abrupt changes in volatility. Another advancement was the development of score-driven models. The Generalized Autoregressive Score (GAS) framework, introduced by Creal et al. (2013), relies on the scaled score of the predictive likelihood to update time-varying parameters. GAS models outperformed the GARCH family in forecasting Value-at-Risk. This mainly holds for non-Gaussian return distributions that have skewness and heavy tails (Ardia et al., 2018). Extending the score-driven models, Harvey (2013) proposed the Dynamic Conditional Score (DCS) model, which focuses on dynamic components and is expressed and estimated using a state-space framework. This enhances the flexibility in estimating and interpretating latent components. The DSC model is particularly suitable for capturing long-memory and modelling structural shifts, particularly in the case of non-stationary or complex distribution of returns. Driven by the shortcomings of traditional volatility models in accounting for both long memory and nonlinear market dynamics, Peiris et al. (2025) proposed a long memory, nonlinear realized volatility model for the direct forecasting of Value-at-Risk (VaR). The model, known as RNN-HAR, is an extension of the heterogeneous autoregressive (HAR) model, which efficiently captures long memory behaviour. This extension integrates a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) to address the nonlinear dynamics. Extending the Realized GARCH framework, Lin et al. (2025) addressed the evolving nature of the leverage effect. Periods marked by heightened uncertainty or structural breaks often lead to variations in the asymmetric relationship between returns and volatility. To overcome this limitation, they extended the Realized GARCH model to account for a time-varying leverage effect. The model allows for a dynamic evolution of the asymmetric relationship between returns and volatility, enabling it to respond flexibly to changes in market sentiment and volatility behaviour, thereby enhancing the accuracy of risk forecasts such as Value-at-Risk.

2.2. Empirical Findings on Volatility Behaviour

Early evidence from developed countries was strongly in favour of the leverage effect. Bouchaud et al. (2001) examined the leverage effect across major indices including the S&P 500 (the US), NASDAQ (the US), CAC 40 (France), FTSE (the UK), DAX (Germany), Nikkei (Japan), and Hang Seng (Hong Kong). Their results indicated that the leverage effect is more prominent in stock indices than in individual stocks, though with a quicker dissipation. Building on this, Zumbach (2013) reported further evidence in support of the widespread presence of the leverage effect across different markets (the DJ EuroStoxx 50, S&P 500, and Swiss Performance Index (SPI)). His findings indicated a negative correlation between past returns and realized volatility that remained consistent over several time periods, implying that the leverage effect is a common feature of volatility behaviour in developed countries.

Extending the analysis to emerging markets, Aloui (2017) investigated the presence of the leverage effect in four MENA markets—Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. Using daily returns from the period of 2007 to 2015, he reported evidence of a leverage effect in all these markets. The APARCH model with skewed student’s distribution outperformed the other volatility models under consideration. The study period covered by Aloui is interesting as it included extreme adverse shocks such as the Arab spring, oil price fluctuations, and the 2008 global financial crisis as well as the euro currency crisis. In contrast to the findings of Aloui (2017), who reported consistent evidence of the leverage effect in four MENA markets, Al-Ahmad and Salman (2016) found no such effect in their study of the Damascus Securities Exchange. Although their findings indicated that the EGARCH model provided the best fit for the data, no leverage effect was detected. Instead, positive shocks had a greater impact than negative ones. They attributed this finding to the fact that investors were already pessimistic about the market during the period of the Syrian crisis; accordingly, the arrival of positive news triggered more volatility. When modelling the volatility of the Jordanian market between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2014, Al-Najjar (2016) applied ARCH, GARCH, and EGARCH models. His findings confirmed the absence of leverage effect in the Amman stock market, indicating that symmetric ARCH/GARCH models can adequately capture the characteristics of the index. In her examination of the Tunisian market, Neifar (2020) applied GARCH, GARCH-M, PGARCH, EGARCH, TGARCH, and APGARCH models to capture the volatility dynamic of the TUN index between 1 February 2011 and 19 November 2019. While the results of the EGARCH model revealed the absence of a leverage effect, the findings from the TGARCH and APGARCH models indicated that the impact of good news on future volatility is greater than that of bad news.

Studies examining the leverage effect in GCC markets have yielded inconclusive findings, each offering unique insights. Mohamad (2020) examined the presence of volatility clustering, mean reversion, risk–return relationship, leverage effect, and weak-form efficiency in GCC markets between 2010 and 2013. Applying GARCH (1,1), EGARCH (1,1) and GARCH-M (1,1) to model volatility, he concluded that the Bahraini market exhibited all the features examined except for the leverage effect and weak-form efficiency. The remaining stock markets (Saudi Arabia, Dubai, Qatar, Kuwait, and Oman) exhibited all the features except the efficiency while Abu Dhabi was characterized by mean reversion only. Extending the time horizon, Haji (2021) examined the volatility of the GCC markets between 2010 and 2019. Using daily data of the index and applying GARCH-M, GJR-GARCH, EGARCH, and PGARCH models, the author concluded that the basic symmetric GARCH model best fits the Bahraini data. That is to say, no leverage effect was detected in the BAX during the examined period. Accordingly, the impact of negative shocks on the volatility of the next period is not different than that of positive shocks. The study though did not cover the volatility during COVID-19 and the aftermath recovery. The findings of Mohamad (2020) and Haji (2021) contradict the proposition of Bats and Houben (2017), about greater leverage effect in bank-based systems. Focusing specifically on the COVID-19 period, Saleem et al. (2021) examined volatility changes before and during the COVID-19 period in nine Islamic stock indices, including the Islamic Bahrain index (ISBAHX). Applying a GARCH (1,1) model, the authors reported that there was a significant increase in volatility following the World Health Organization (WHO) declaration of the health crisis. The authors also reported that volatility persistence tended to remain for an extended period after the pandemic. The study, however, was limited to Islamic indices without any investigation of the non-Islamic ones. Doblas et al. (2023) contributed further insight into the Bahraini market by modelling the volatility of the BAX. Using daily data between 2016 and 2022 and applying the Box-Jenkin’s Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model, the authors reported that ARIMA (4,1,1) provides the best fit for modelling the volatility of the BAX. While the model effectively captures short-term shocks and medium-term memory, it fails to capture the long-run persistence of volatility, which is better addressed by GARCH models. Most recently, Albahooth (2025) examined volatility patterns in GCC countries and their main drivers. Applying the ARCH, EGARCH, and GARCH models to the stock market indices in the region, he reported volatility persistence and clustering across all markets. When examining the drivers of volatility, the results indicated that volatility tends to increase with rising geopolitical tensions, inflation levels, and interest rates and decrease with higher growth in GDP.

Reviewing the literature reveals that while several studies examining volatility modelling in the GCC and other frontier markets documented the presence of a leverage effect (e.g., Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Dubai, Qatar, Kuwait, and Oman), others reported asymmetric volatility where good news has a greater impact than bad news (e.g., Syria and Tunisia). Conversely, findings from some markets were consistent with the absence of asymmetric volatility (e.g., Abu Dhabi and Amman). Empirical findings on the Bahrain’s All Share Index (BAX) conclusively indicated a lack of leverage effect (Mohamad, 2020; Haji, 2021). Previous studies on the Bahraini market, however, appear to focus on more stable time periods. This study fills an important research gap by providing empirical evidence on volatility dynamics in a small, bank-based frontier market—Bahrain—which remains largely understudied in the literature. The analysis spans the period from 2010 to 2025, encompassing major external shocks such as the post-financial crisis recovery, the COVID-19 pandemic, and recent geopolitical tensions in the region, thereby enriching the investigation of the leverage effect in a frontier-bank-based market. The next section will explain the data used in this study and the methodology applied.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

The study utilizes daily prices of the BAX for the period from 1 March 2010 to 27 March 2025. The prices (in Bahraini dinar) and the returns (in %) of the BAX were downloaded from Investing.com (https://www.investing.com/ (accessed on 30 June 2025)). The period of study was chosen in a way that focuses on the post financial crisis aftermath, including the COVID-19 pandemic, its recovery phase, and the most recent geopolitical changes in the region.

There are certain features in the data that need to be examined before running the ARCH/GARCH models. More specifically, the time series in question needs to be stationary and its residuals should exhibit heteroskedasticity (Engle et al., 2006).

The stationarity requirement stems from the fact that modelling the volatility of non-stationary data would lead to a forecast that is unreliable. Accordingly, the series needs to be tested for stationarity before any attempt to model its volatility. Similarly, if the residuals do not exhibit heteroscedasticity, then the GARCH model does not need to be applied (Engle et al., 2006). Heteroscedastic residuals imply that the variance is changing over time and that future variances are affected by past values.

3.2. Methodology

As explained above, testing the data for stationarity and heteroscedasticity will be the starting point. To test the stationarity of the BAX, the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (henceforth ADF) test, the Phillips–Perron (henceforth PP) test, and the Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt and Shin (henceforth KPSS) test are applied. Unlike the ADF test, which is a parametric one, the PP test is a non-parametric test and is more appropriate to apply if the data exhibits heteroscedasticity. While the null hypothesis of the ADF and the PP tests is that the time series has a unit root (non-stationary), the null hypothesis of the KPSS test is that the series is stationary. If the tests reveal that the series is non-stationary, the series could be differentiated and tested again for stationarity (Granger & Newbold, 1974).

Testing for heteroscedasticity is performed by applying the ARCH Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test. The null hypothesis of the ARCH LM test is that there is no ARCH effect on the residual series while the alternative hypothesis states that there is still an ARCH effect in the residuals (Engle, 1982).

Prior to modelling the volatility of the BAX, its returns are modelled using either an ARMA (Autoregressive (AR) and Moving Average (MA) or ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) process. Since ARMA models assume stationarity, they cannot be applied to non-stationary data. In such cases, differencing is required and an ARIMA specification is adopted to achieve stationarity prior to estimating the mean equation. This ensures that the subsequent volatility modelling is based on a statistically valid and stable time series. To determine the optimal lag length for the model, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Schwarz Information Criterion (SIC), and the Log-Likelihood (LL) will be compared across different specifications.

After estimating the mean equation by applying an ARMA/ARIMA process, the residuals of the model—which often show volatility clustering in financial data—are extracted. GARCH models are then applied to the residuals to model the conditional variance. This two-step modelling strategy (mean equation followed by variance equation) ensures that the conditional mean dynamics are filtered out before modelling the conditional variance, allowing the GARCH-family models to focus exclusively on volatility clustering and shock asymmetry.

3.2.1. The ARCH Model

Mandelbrot (1963) observed volatility clustering in financial returns. He reported that small changes are followed by small changes and large ones are followed by large ones. This holds irrespective of the direction of the change. Later, Engle (1982) reported that time series data are heteroscedastic, where the variance of the error term is changing over time. To account for the time-varying nature of volatility, Engle (1982) developed the Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (ARCH) model. The model uses the standard deviations of the sample, based on historical data, and follows the maximum likelihood method to estimate conditional variances.

The ARCH model is expressed as

σ2t stands for the conditional variance at time t, α0 is the constant term, and α1 captures the impact of squared returns from previous time periods whereby t = 1 to q. To avoid generating negative variances that are meaningless, α0 and need to be ≥0 (for all t).

While the ARCH models are able to capture the impact of short-term shocks on current returns, they fail to capture the persistence of volatility over the long-term. In order for the model to precisely capture the dynamic nature of volatility, it has to include a larger number of lags. This, however, would result in a more complex model that might end up capturing noise rather than meaningful patterns in the data. This issue was addressed by Bollerslev (1986) in his development of the GARCH model.

3.2.2. The GARCH Model

Building on the work of Engle (1982), Bollerslev (1986) developed the GARCH model, a generalization of the ARCH model. The GARCH (p, q) process is explained as

In the GARCH (p, q) model, the time-varying volatility is expressed as a function of the constant α0, the squared error terms in lagged values (ε2t−1), and the conditional variance in lagged values (σ2t−1). α1 and β are the ARCH and the GARCH terms, respectively.

To ensures that the conditional variance is always positive, all coefficients , must be non-negative. Since variance is perceived as a measure of risk or volatility, a negative variance would indicate negative risk, which lacks any practical meaning. Moreover, having a non-negative variance is particularly important for estimating the Value-at-Risk (VaR), calculating option pricing, and managing portfolios.

The sum of α and β has meaningful implications in terms of the persistence of shocks. Three scenarios could emerge from the model, each with a different implication about the persistence of volatility. More precisely, if the sum of α and β is less than 1, this indicates that the impact of a shock on the returns series dies over time. Conversely a sum that is equal to one indicates that shocks are persistent. That is to say, shocks cause changes in the future returns that are permanent. If the sum of α and β is greater than 1, then the impact of shocks is explosive. That is to say, shocks will cause a fast increase in volatility.

3.2.3. The Exponential GARCH

Although the GARCH model is able to capture the long-term impact of shocks, it fails to account for the fact that volatility might not be symmetric between positive and negative shocks. It assumes that the impact of similar sizes of positive and negative shocks is the same. Financial time series, however, are believed to exhibit higher volatility in response to negative shocks than to positive ones.

The exponential GARCH (henceforth EGARCH) proposed by Nelson (1991) addresses the issue of asymmetry in volatility. To capture the asymmetric nature of volatility, the model utilizes the logarithm of the conditional variance as the dependent variable. The EGARCH is expressed in the equation below:

Ln(σ2t) denotes the conditional variance at time t in logarithmic terms, ω is the constant, and alpha captures the impact of the modified ARCH term. Ln(σ2t−1) represents the log of the lagged variance. This term accounts for the volatility persistence (the GARCH). The coefficient captures the leverage effect. A gamma that is less than zero indicates that there is a leverage effect, that is to say, the volatility caused by negative shocks is higher than that caused by positive ones. A gamma equal to zero indicates that the volatility of returns is symmetric, i.e., the returns exhibit similar volatility in case of positive and negative shocks. Alternatively, a gamma that is higher than zero, a rare scenario, indicates that the volatility is higher in the event of positive shocks compared to that of negative ones (Nelson, 1991).

3.2.4. The GJR-GARCH Model

Another asymmetric model-to-model volatility is the GJR-GARCH model. The model was proposed by Glosten et al. (1993). It differs from the EGARCH model in how the asymmetry of volatility is measured. While the EGARCH models the logarithm of the conditional variances, the GJR GARCH models the conditional variance and adds an indicator function to capture the leverage impact. The model is presented as

σ2t is the conditional variance at time t, is the constant, ε2t−1 denotes the squared residuals at time t − 1, It−1 is an indicator function that equals one in case of negative shocks and zero otherwise, and σ2t−1 is the lagged conditional variance.

A positive indicates that the impact of negative shocks is higher than that of positive ones of the same size, which reflects the leverage effect. Conversely, insignificant indicates that shocks have no asymmetry effect on volatility; accordingly, the model converts to a GARCH (1,1).

3.2.5. Diagnostic Tests, Model Selection and Application to VaR and ES

To choose the appropriate volatility model, model selection criteria and diagnostic analysis of the residuals are usually applied. Following Tripathi and Singh (2016), Sood and Saluja (2023) and Muneer et al. (2025), the model that best fits the data is the one that displays the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the lowest Schwarz Information Criterion (SIC), and the highest Log-Likelihood (LL)

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) are also applied to evaluate the forecast accuracy of the volatility models examined. These three measures rely on the differences between predicted and actual values; therefore, the smaller the measure, the more accurate the model is in forecasting volatility.

In addition to these accuracy metrics, Value-at-Risk (VaR) and Expected Shortfall (ES) were employed to quantify the downside risk in the market. While VaR estimates the maximum loss not expected to be exceeded at a given confidence interval, ES accounts for the average loss conditional on exceeding that threshold, thereby providing a broader view of tail risk. These metrics provide an effective approach for evaluating the likelihood of extreme losses over a given holding period.

The choice of VaR and ES as the principal tail risk measures stems from two reasons. First, both measures are well-established and widely adopted in academic research and regulatory framework, particularly under Basel III, where the use of ES for calculating market risk capital requirements is mandatory as a result of its outstanding sensitivity to tail events. Second, in contrast to drawdown, which captures cumulative losses over prolonged periods, these measures provide point-in-time and expected tail-loss metrics, making them appropriate for forecasting risk over a short-horizon.

The distribution of the underlying returns and volatility dynamics largely affect the reliability of these measures. That said, the residuals were assumed to follow a Student-t distribution, as it accounts for the excess kurtosis and fat-tailed behaviour usually observed in financial data. GARCH-family specifications were used to model conditional volatility, and the 95% and 99% confidence levels were used to estimate the VaR and ES over a 30-day horizon.

Worth noting that while stochastic volatility (SV) and regime-switching models are able to account for latent or sudden changes in variance, the current study relies on the deterministic GARCH-family specification to estimate volatility. Three reasons directed us to follow this approach. First, as reported by Aloui (2017), Hansen and Lunde (2011), Chan and Grant (2016), and Hafner and Preminger (2010), to outperform the GARCH models in modelling volatility, SV and regime-shifting models require high-frequency data. Since the Bahraini market has a bank-based structure, with moderate trading activity and limited depth, SV and regime-shifting models of volatility which rely on Bayesian or simulation-based methods would unnecessarily complicate the process. Second, being widely used in modelling volatility, GARCH models serve as a benchmark model in financial econometrics. That is to say, they allow us to compare our findings with the existing literature. Third, empirical studies applying GARCH models across both developed and developing economies have consistently produced reliable estimates of volatility clustering and leverage effects (e.g., Aloui, 2017; Hansen & Lunde, 2011).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results of the Stationarity and Heteroscedasticity Tests

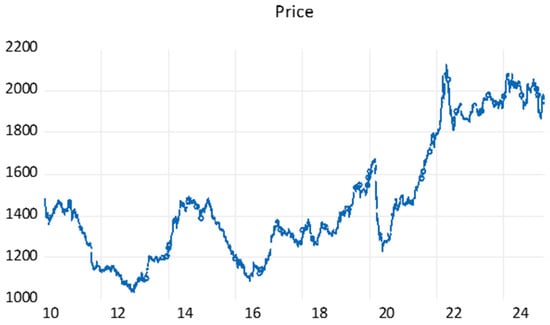

The price series of the BAX, depicted in Figure 1, indicates that the series is non-stationary. This conclusion is supported by the results of the ADF, PP, and KPSS tests displayed in Table 1. Table 1 shows that the T-statistics for both the ADF and PP tests are insignificant at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels of significance. Accordingly, the null hypothesis that the time series has a unit root, i.e., non-stationary, cannot be rejected. The KPSS test results further confirm the non-stationarity of the series as the null hypothesis of stationarity is rejected at the 1% level (p = 0.010).

Figure 1.

The BAX price series.

Table 1.

Results of the ADF test on the BAX price series.

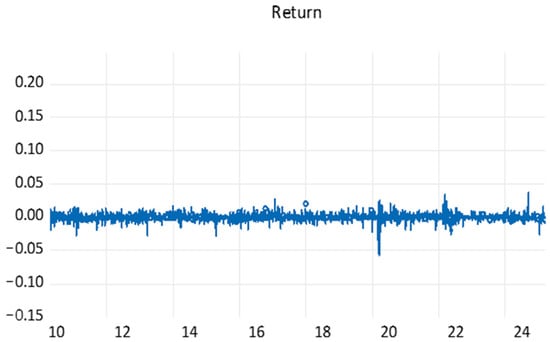

To address the issue of non-stationarity in the price data, the first difference in the price series (returns) is calculated. Figure 2 displays the behaviour of the BAX returns over the examined period. The figure reveals that the return series is stationary. Similarly, the results of the ADF test on the BAX returns, displayed in Table 2, confirm the outcomes obtained from graphing the series. The T-statistics of the return series (−29.97) is much higher than the critical T values (−3.4327) at the 1% level of significance. This indicates that the null hypothesis of non-stationarity is rejected at the 1% level of significance or better. The results of the PP test and KPSS test strongly support the conclusion drawn from the ADF test, confirming the stationarity of the return series.

Figure 2.

The BAX returns series.

Table 2.

Results of the ADF test on the BAX return series.

Table 3 displays the descriptive statistics of the BAX returns. The return series has a close to zero mean (0.000086), with moderate daily fluctuations (SD~0.005), and minimum and maximum values of (−0.058200) and (0.037600), respectively. The returns are negatively skewed, indicating that large losses are more frequent than large gains. The series also exhibits high leptokurtosis, implying fat tails and a sharp peak around the mean. This suggests volatility clustering and downside risk in returns, supporting the use of GARCH-family modelling.

Table 3.

The descriptive statistics of the BAX returns.

The results of the ARCH LM test, that evaluates the presence of heteroscedasticity, are reported in Table 4. The results indicate that the null hypothesis of no ARCH effect in the residual series is rejected (p = 0.000 < 0.0001).

Table 4.

Heteroskedasticity Test: the ARCH effect.

The stationarity of the series and the significant heteroskedasticity in the residuals imply that the ARCH and GARCH models can be applied to model the volatility of the data.

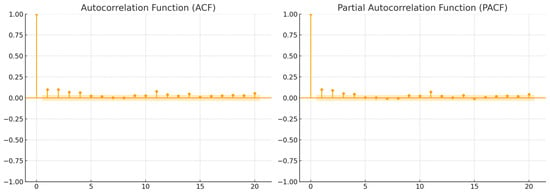

Before estimating the volatility models, an ARMA (p, q) model of the mean returns must be estimated. The ARMA model was chosen over ARIMA because the return series is stationary and does not require differencing, rendering ARIMA unnecessary. The p and q denote the order of the autoregressive term and the moving average term, respectively. To determine the order of the model, i.e., the values of p and q, the autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation patterns will be examined. The autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation functions (ACF and PACF), displayed in Figure 3 and Table 5, show significance only at lag 1. This is consistent with an ARMA (1,1) specification for the mean equation. Similarly, the diagnostic tests reported in Table 6 confirm that the ARMA (1,1) model provides the most statistically robust fit to the return series data. More specifically, ARMA (1,1) model has the lowest AIC and SIC values and the highest log-likelihood and Adjusted R2 ratio compared to other model specifications.

Figure 3.

Correlograms showing short-run autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation.

Table 5.

Correlograms showing short-run autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation.

Table 6.

Diagnostic test for the ARMA model.

The visual inspection of the data, supported by the autocorrelation function (ACF) analysis, confirms that the series is stationary and non-seasonal. This is evidenced by the absence of significant spikes at seasonal lags, aligning with the diagnostic approaches recommended by Box et al. (2015) and Hyndman and Athanasopoulos (2018). Consequently, estimating a Seasonal Autoregressive Moving Average (SARMA) model was deemed unnecessary, as it would introduce additional complexity without improving model accuracy. Following the principle of parsimony (Burnham & Anderson, 2002), the ARMA model was preferred for its simplicity, efficiency, and adequacy in capturing short-term dependencies (Enders, 2014).

4.2. Results of the Volatility Modelling

After estimating the ARMA (1,1) model, the ARCH (1) model was estimated. Results of the ARCH (1) model are displayed in Table 7. The table reveals that the past squared residuals have a significant impact on volatility (Z = 15.83, significant at the 0.1% level). The results of the diagnostic tests indicate that the ARCH effect is no longer there (p = 0.708); that is to say, there is no further time-varying volatility in the residuals. The Durbin–Watson test (henceforth DW) is very close to 2, indicating that the residuals are not serially correlated and the model has succeeded in capturing the autocorrelation in the volatility process.

Table 7.

Results of ARCH, GARCH, EGARCH and GJRGARCH.

The estimated GARCH (1,1) model is displayed in Table 7. Both the ARCH and GARCH terms are highly significant (Z = 12.29646 and 49.51318, respectively), indicating that the conditional variance is affected by past squared residuals and past variances. The sum of the ARCH and GARCH terms is equal to 0.88, which implies a mean reversion with high persistence; this means that the value of the returns will come back to its mean, but it takes a long time to do so. The diagnostic tests of the model indicate that there is no remaining ARCH effect (p = 0.5703), no serial autocorrelation (DW = 2.052), and an improvement in the log-likelihood, the AIC, and the SIC.

Results of estimating the EGARCH model are presented in Table 7. As illustrated in the table, the ARCH and GARCH effects are both significant at the 0.1% level or better (Z = 18.43648 and 115.4377, respectively). The negative gamma indicates the presence of a leverage effect whereby the impact of negative shocks is higher than that of positive ones. The leverage coefficient (−0.015563) is significant at the 5% level of significance (Z = 1.982212). The diagnostic tests reveal that there is no remaining ARCH effect (p value = 0.4232), no serial autocorrelation (DW = 2.054), and that the log-likelihood of the model, the AIC, and the SIC have all improved compared to the previous models.

The results of the GJR-GARCH model are reported in Table 7. The results indicate that the ARCH and GARCH effects are both significant at the 0.1% level of significance or better (Z = 9.564341 and 47.02127, respectively). The leverage coefficient is positive (0.021756) which indicates that negative shocks have a greater impact than positive ones, the coefficient, however, is insignificantly different from zero (Z = 1.562190). The diagnostic tests reveal that there is no remaining ARCH effect (p value = 0.6393) and no serial autocorrelation (DW = 2.051). The log-likelihood of the model, the AIC, and the SIC, however, seem to have deteriorated compared to the EGARCH model.

To select the volatility model that best describes the data, we compare the AIC, SIC and log-likelihood across the different models. The model that achieves the lowest AIC and SIC, and the highest log-likelihood is chosen as the best-fitting model for the data.

The diagnostic of the error terms reveals that the EGARCH model is the model that best fits the data. It has the lowest AIC and SIC, and the highest log-likelihood among the remaining models. Accordingly, one can conclude that the BAX returns exhibit a leverage effect whereby the impact of negative shocks on volatility is higher than that of the positive ones.

When comparing the volatility models in terms of their forecast accuracy, Table 7 reveals that the ARCH model, followed by the EGRACH model, has the lowest forecast errors. While the ARCH model achieved the lowest RMSE (0.005339), MAE (0.00311), and MAPE (144.53%), suggesting slightly more accurate forecast than the EGARCH model, its structure tends to amplify the impact of isolated shocks and generate volatility forecasts that are less consistent over time. The EGARCH model, on the other hand, performed very close to the ARCH model in the forecast accuracy (with an RMSE of 0.005341, MAE of 0.003327, and MAPE of 158.56%), but outperformed all the examined models in structural characteristics. By modelling the logarithm of variance, EGARCH ensures non-negative volatility forecasts, a gradual decay in variance, and asymmetric responsiveness to both positive and negative market movements. Accordingly, based on the statistical accuracy and model behaviour, EGARCH emerges as the most suitable model for volatility forecasting.

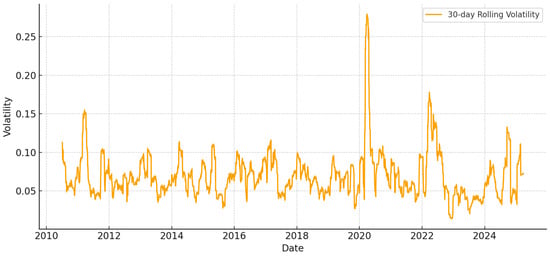

Following the diagnostic evaluation and selection of the optimal volatility model, attention turns to the estimation of downside risk using Value-at-Risk (VaR) and Expected Shortfall (ES). Figure 4 and Figure 5 depict the rolling annualized volatility and Value-at-Risk of the BAX returns. As illustrated in Figure 4, the rolling 30-day annualized volatility of the BAX exhibits significant volatility clustering, with observable spikes in periods of major events such as the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021) and regional geopolitical tensions (2022–2023). This indicates that the Bahraini market is sensitive to systemic shocks and displays volatility persistence as identified by the GARCH-family models.

Figure 4.

Rolling Annualized Volatility (30-day window).

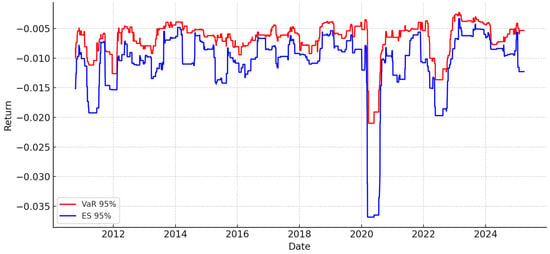

Figure 5.

Rolling Value-at-Risk (VaR) and Expected Shortfalls.

The rolling 95% Value-at-Risk (VaR) and Expected Shortfall (ES) exhibit the time-varying nature of downside risk. The graph shows a significant increase in both measures during crisis periods, highlighting the asymmetric nature of volatility behaviour. The higher ES values relative to VaR are consistent with the leverage effect captured by the EGARCH model. More specifically, this indicates that the intensity of extreme losses is higher than what is predicted by quantile-based measures alone.

4.3. Discussion and Implications of the Findings

The findings validate our choice of using the GARCH family. More specifically, the BAX exhibited conditional heteroskedasticity and volatility clustering which were captured through a deterministic process relying on observable lagged residuals and conditional variances. The selected model, EGARCH (1,1), generated the lowest AIC and SIC values, the highest log-likelihood, and fully accounted for the ARCH effect, suggesting that it effectively captured the volatility dynamics without the need to rely on models that capture latent variance, such as SV or regime-switching models.

The presence of a leverage effect in the Bahraini market is consistent with expectations in financial data and with what is anticipated in a bank-based system, where the impact of negative shocks is more intensified (Bats & Houben, 2017). The finding also aligns with those reported by Aloui (2017) and Mohamad (2020) for other MENA and GCC markets, including Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Dubai, Qatar, Kuwait, and Oman. However, it contrasts with the findings of Al-Ahmad and Salman (2016), Al-Najjar (2016), and Neifar (2020), who reported the absence of a leverage effect in Syria, Jordan, and Tunisia, respectively. The results of the current study are also inconsistent with those of Mohamad (2020) and Haji (2021), who failed to document a leverage effect in Bahrain. These differences may be attributed to the time period examined, as the current study covers a significant negative shock—namely, the COVID-19 pandemic—and recent geopolitical changes in the region.

Mateus et al. (2024) reported that oil-driven demand shocks are major drivers of stock returns in sectors of petroleum exporters and importers. They also documented that the association between oil shocks and stock indices is more prominent in periods of financial crisis and geopolitical instability. Accordingly, the finding of a leverage effect in the Bahraini market has important implications as the country relies heavily on the oil sector (Ministry of Finance and National Economy, 2024). That is to say, the country is vulnerable to negative shocks in oil prices. This, combined with the large contribution of the banking sector to GDP, makes the awareness of the leverage effect extremely useful to stabilize the market.

The findings have important implications for investors, portfolio managers, and policymakers. Knowing that there is a leverage effect in the Bahrain Bourse helps investors in performing a better risk management strategy. That is to say, by taking the leverage effect into account, investors and portfolio managers can avoid underestimating the impact of negative shocks in their Value-at-Risk (VaR) estimations, particularly during periods where market downturns are expected (e.g., drop in oil prices).

Similarly, when investors and portfolio managers are formulating their portfolios, they can utilize their knowledge of the EGARCH forecast of volatility to modify their hedging techniques. That is to say, they can increase their holding of safe assets or derivatives when negative news or adverse macroeconomic conditions are expected, and reduce it otherwise. Furthermore, awareness of the leverage effect helps investors and portfolio managers in achieving a better asset allocation and more accurate pricing of the derivative. For example, in periods of low oil prices and/or high political instability in Bahrain, investors can shift from equity to bonds or cash and cash equivalents.

Pricing derivatives would also benefit from documenting a leverage effect in the Bahraini market. That is to say, modelling the asymmetric volatility enables more accurate pricing of equity options that are sensitive to tail risk.

Awareness of the leverage effect is also useful for policymakers. More specifically, as the error terms tend to react more strongly to negative shocks than to positive ones, regulators and policymakers can utilize this knowledge to stabilize the market by imposing counter-cyclical macroprudential policies. A practical application of this is the adoption of high capital buffers in periods of low volatility and lower buffers in periods of high volatility. In the context of Bahrain, where counter-cyclical capital buffers are currently set at zero, this recommendation offers a valuable opportunity to strengthen financial resilience. By introducing a dynamic buffer framework, regulators can better align capital requirements with market conditions, enhancing the system’s ability to absorb shocks and support stability.

Additionally, the monetary authorities can utilize the EGARCH volatility forecast to adjust the interest rate proactively, enabling them to mitigate the impact of negative shocks. Finally, accounting for the asymmetric nature of volatility can also enhance regulatory stress testing by improving preparedness for negative market shocks.

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

As the study period spans both the pre- and post-COVID-19 phases, we conduct a sensitivity analysis to examine whether volatility behaviour differs between these two periods. To achieve this, we split the data into two sub-samples: pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19. The pre-COVID-19 series covers data from 1 March 2010 to 27 February 2020, while the post-COVID-19 series spans from 1 March 2020 to 27 March 2025. 27 February 2020, was selected as the cutoff date because COVID-19 marked a turning point, spreading rapidly from Asia into Europe, the Middle East, and South America.

Table 8 and Table 9 display the results for the sub-periods examined. Similarly to the model that uses data for the full period, the EGARCH model appears to best fit the data for both the pre- and post-COVID-19 phases. The model has the highest log-likelihood ratio and the lowest AIC and SIC values.

Table 8.

Results of ARCH, GARCH, EGARCH, and GJRGARCH in the pre-COVID-19 Phase.

Table 9.

Results of ARCH, GARCH, EGARCH, and GJRGARCH in the post-COVID-19 Phase.

Interestingly, although the EGARCH model appears to best fit the data, the leverage effect is observed only in the post-COVID-19 period. More precisely, the leverage coefficient in the pre-COVID-19 period is positive (γ = 0.86706) and significant (Z = 53.0453) at the 1% level, indicating that the market reacts more strongly to positive news than to negative news. This could be driven by the political stability of the region, the economic diversification policies adopted in Bahrain during that period, the resilient performance of the banking sector, and the relatively stable oil prices. The finding is consistent with the results of Al-Ahmad and Salman (2016) and Neifar (2020), who reported a greater impact of positive shocks compared to negative ones in the Damascus Securities Exchange and the Bourse de Tunis over a relatively similar time span.

In contrast, the post-COVID-19 period demonstrates a leverage effect (γ = −0.023598) that is significant at the 5% level (Z = −2.338676). This confirms the earlier findings from the full sample period, where the leverage effect was documented.

Overall, the sensitivity analysis confirms that while Bahrain’s market exhibited a positive asymmetric response to news in the pre-COVID-19 period, the leverage effect emerged only after COVID-19, underscoring how systemic shocks can fundamentally alter volatility dynamics in frontier, bank-based economies.

5. Conclusions

This paper examined the volatility of the Bahrain All Share Index (BAX) using daily data from 2010 to 2025, applying the GARCH family of models. After confirming stationarity with ADF, PP, and KPSS tests, and detecting heteroskedasticity with the ARCH LM test, we estimated both symmetric and asymmetric GARCH models. The EGARCH specification emerged as the best-fitting model, demonstrating a leverage effect whereby negative shocks exert greater influence on volatility than positive ones.

These results extend the literature by documenting asymmetric volatility in a small, bank-based frontier market. Earlier studies on Bahrain reported no leverage effect (Mohamad, 2020; Haji, 2021), but our broader time frame, which includes COVID-19 and recent geopolitical tensions, shows otherwise. This indicates that systemic shocks in bank-based economies amplify downside risk. Importantly, the results of the sensitivity analysis further reinforce these findings, confirming that the leverage effect was observed only in the post-COVID-19 period.

Nevertheless, this study is limited to deterministic GARCH specifications. Future work should compare these results with stochastic volatility, regime-switching, or score-driven models, and explore whether behavioural biases amplify leverage effects. Out-of-sample forecasting, incorporating RMSE and MAPE, could further test robustness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.A.-A. and Z.M.; Methodology, Z.A.-A. and Z.M.; Software, Z.M.; Validation, Z.A.-A. and N.K.; Formal analysis, Z.A.-A. and Z.M.; Investigation, Z.M.; Resources, Z.A.-A.; Data curation, Z.M. and N.K.; Writing—original draft, Z.A.-A. and N.K.; Writing—review & editing, Z.A.-A. and N.K.; Visualization, Z.A.-A.; Supervision, Z.A.-A.; Project administration, Z.A.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Investing at https://www.investing.com (accessed on 30 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Bahrain is not yet part of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. It is classified as a standalone/frontier market by MSCI/FTSE Russell, respectively, indicating low trading volume and small nuumber of listed firms. |

References

- Al-Ahmad, Z., & Salman, A. (2016). Modelling volatility in emerging stock markets: The case of Damascus securities exchange. Tishreen University Journal for Research and Scientific Studies—Economic and Legal Sciences Series, 41(2), 247–266. [Google Scholar]

- Albahooth, A. (2025). Quantitative analysis of stock market volatility in GCC economies: A formal statistical approach. Journal of Administrative and Economic Sciences, 18(1), 385–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najjar, F. J. (2016). Social responsibility and its impact on competitive advantage: An applied study on Jordanian telecommunication companies. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 7(3), 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Aloui, C. (2017). Value-at-Risk and Basel capital charges: Evidence from MENA equity markets. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 27(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ardia, D., Bluteau, K., Boudt, K., & Catania, L. (2018). Forecasting risk with Markov-switching GARCH models: A large-scale performance study. International Journal of Forecasting, 34(4), 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bats, J., & Houben, A. (2017). Bank-based versus market-based financing: Implications for systemic risk (Vol. 577, pp. 1–22). DNB working paper. De Nederlandsche Bank. Available online: https://www.dnb.nl/media/igjp5crb/wp_577_tcm47-369482.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Bauwens, L., Preminger, A., & Rombouts, J. V. K. (2010). Theory and applications of Markov switching GARCH models. The Econometrics Journal, 13(2), 218–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, F. (1976). Studies of stock price volatility changes. In Proceedings of the 1976 meetings of the american statistical association, business and economic statistics section (pp. 177–181). American Statistical Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bollerslev, T. (1986). Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. Journal of Econometrics, 31(3), 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchaud, J.-P., Matacz, A., & Potters, M. (2001). Leverage effect in financial markets: The retarded volatility model. Physical Review Letters, 87(22), 228701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G. E. P., Jenkins, G. M., Reinsel, G. C., & Ljung, G. M. (2015). Time series analysis: Forecasting and control (5th ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R. (2002). Model selection and multimodel inference: A practical information-theoretic approach (2nd ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- CEIC Data. (n.d.). Bahrain market capitalization: % of GDP, 2002–2025. Available online: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/bahrain/market-capitalization (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Central Bank of Bahrain. (2025). Financial stability report (Issue No. 37). Financial Stability Directorate, Central Bank of Bahrain. Available online: https://www.cbb.gov.bh (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Chan, K. F., & Grant, A. L. (2016). Modelling energy price dynamics: GARCH versus stochastic volatility. Energy Economics, 59, 292–305. [Google Scholar]

- Christie, A. A. (1982). The stochastic behaviour of common stock variances: Value, leverage and interest rate effects. Journal of Financial Economics, 10(4), 407–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creal, D., Koopman, S. J., & Lucas, A. (2013). Generalized autoregressive score models with applications. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 28(5), 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblas, M. P., Natarajan, V. K., & Sankar, J. P. (2023). Revisiting the auto-regressive integrated moving average approach to modelling volatility using Bahrain All Share Index daily returns. Middle East Journal of Management, 10(6), 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, W. (2014). Applied econometric time series (4th ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Engle, R. F. (1982). Autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity with estimates of the variance of United Kingdom inflation. Econometrica, 50(4), 987–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. F., Focardi, S. M., & Fabozzi, F. J. (2006). ARCH/GARCH models in applied financial econometrics (New York University working paper). New York University. [Google Scholar]

- Glosten, L. R., Jagannathan, R., & Runkle, D. E. (1993). On the relation between the expected value and the volatility of the nominal excess return on stocks. The Journal of Finance, 48(5), 1779–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C. W. J., & Newbold, P. (1974). Spurious regressions in econometrics. Journal of Econometrics, 2(2), 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, C. M., & Preminger, A. (2010). Deciding between GARCH and stochastic volatility via strong decision rules. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference, 139(6), 2172–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, A. A. (2021). Time-varying volatility modelling of GCC stock markets [Master’s thesis, University of Bahrain]. University of Bahrain Digital Repository. Available online: https://digitalrepository.uob.edu.bh/en/dar/time-varying-volatility-modeling-gcc-stock-markets (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Hansen, P. R., Huang, Z., & Shek, H. H. (2012). Realized GARCH: A joint model for returns and realized measures of volatility. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 27(6), 877–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P. R., & Lunde, A. (2011). Forecasting volatility using high-frequency data. Journal of Financial Econometrics, 9(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, A. C. (2013). Dynamic models for volatility and heavy tails: With applications to financial and economic time series. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heston, S. L. (1993). A closed-form solution for options with stochastic volatility with applications to bond and currency options. The Review of Financial Studies, 6(2), 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R. J., & Athanasopoulos, G. (2018). Forecasting: Principles and practice (2nd ed.). Otexts. Available online: https://otexts.com/fpp2/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Lin, J., Mao, Y., Hao, H., & Liu, G. (2025). Semiparametric estimation and application of realized GARCH model with time-varying leverage effect. Mathematics, 13(9), 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B. (1963). The variation of certain speculative prices. Journal of Business, 36(4), 394–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, H. (1952). Portfolio selection. The Journal of Finance, 7(1), 77–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mateus, C., Bagirov, M., & Mateus, I. (2024). Return and volatility connectedness and net directional patterns in spillover transmissions: East and Southeast Asian equity markets. International Review of Finance, 24(1), 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance and National Economy. (2024). Bahrain economic quarterly—Q4 2024. Kingdom of Bahrain. Available online: https://www.mofne.gov.bh/media/cjonvuwp/beq-2024-en.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Mohamad, A. (2020). Investigating some characteristics and features of the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries (GCC) stock markets. The Scientific Journal of King Faisal University, 12(2), 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, S., Leal, C. C., & Oliveira, B. (2025). Analyzing volatility patterns of Bitcoin using the GARCH family models. Operations Research Forum, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neifar, M. (2020). Multivariate GARCH approaches: Case of major sectorial Tunisian stock markets (Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper No. 99658). University Library of Munich. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D. B. (1991). Conditional heteroskedasticity in asset returns: A new approach. Econometrica, 59(2), 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, R., Tran, M.-N., Wang, C., & Gerlach, R. (2025). Loss-based Bayesian sequential prediction of Value-at-Risk with a long-memory and non-linear realized volatility model. Journal of Financial Econometrics, 23(4), bnbaf017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A., Bárczi, J., & Sági, J. (2021). COVID-19 and Islamic stock index: Evidence of market behavior and volatility persistence. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(8), 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, V., & Saluja, H. S. (2023). Unfolding volatility and leverage effect: A comparison of S&P BSE SENSEX and NIFTY50. Apeejay Journal of Management and Technology, 11(1), 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Trading Economics. (n.d.). Bahrain stock market (Bahrain all share)—Quote—Chart—Historical data—News. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/bahrain/stock-market (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Tripathi, D. K., & Singh, S. (2016). Modelling stock market return volatility: Evidence from India. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 7(13), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zumbach, G. (2013). Leverage effect. In Discrete time series, processes, and applications in finance (pp. 205–209). Springer. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).