Abstract

This paper examines the impact of a firm’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) level on abnormal stock returns around merger and acquisitions (M&A) announcements. Using a sample of transactions announced by German DAX-listed acquirers from 2017 and 2022, the analysis assesses whether CSR creates value for acquiring firms’ shareholders and offers a comprehensive discussion of potential factors supporting or opposing this notion. Our study seeks to fill a notable gap in the German literature on the relationship between CSR performance and abnormal stock returns surrounding M&A announcements. Building upon prior research findings in the US and in an international sample, our investigation focuses on the German market. Employing event study methodology, our results indicate that M&A transactions of German-listed acquirers did not yield significant negative or positive cumulative abnormal returns for event windows of 3 and 11 days. Furthermore, based on multiple linear regression, no evidence was found that CSR positively or negatively influenced abnormal stock returns following M&A announcements, suggesting that positive and negative effects potentially offset each other. The outcomes of our research have important implications for investors, as CSR initiatives do not serve as a positive trading signal, guaranteeing excess returns, which contrasts findings from previous studies in other developed countries. For managers, it is essential to concentrate on factors beyond CSR performance, such as synergies and fit. Finally, both managers and investors should not view CSR as a shareholder value-enhancing short-term investment but as an integral component of fostering sustainable business development.

Keywords:

corporate social responsibility; sustainability; mergers and acquisitions; shareholder value; event study methodology JEL Classification:

G11; G14; G34

1. Introduction

Many companies have increased their investments in CSR as part of their strategic orientation or in response to growing stakeholder requirements regarding their social and environmental impact. McWilliams and Siegel (2001) depicted CSR as actions that go beyond the interests of a company and result in social good. According to Hill et al. (2007), CSR is defined as economic, legal, moral, and philanthropic actions influencing relevant stakeholders. The growing importance of CSR for companies’ operations is best reflected in the increasing demand for socially responsible investment (SRI) funds from an investor’s perspective (Cellier and Chollet 2016). According to a report by the Forum for Sustainable Investments, the total volume of SRI funds at the end of 2022 amounted to EUR 475.8 billion in Germany, up 16% compared to the previous year (FNG Marktbericht Deutschland 2023).

As a result of the increasing importance of CSR in managerial and strategic practice, corporate social activities have been put on the research agenda. In particular, the question of whether CSR leads to value creation or, on the contrary, destroys value for shareholders is under much debate (Aktas et al. 2011; Broadstock et al. 2020; Tampakoudis et al. 2021; Cho et al. 2021). Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) provide an interesting setting to investigate this question, as M&A transactions can be considered one of the most important managerial decisions (Jost et al. 2022), having a substantial impact on shareholder wealth (Teti et al. 2022).

Despite an increasing number of studies, however, CSR within the context of M&A is still underrepresented (Gonzàlez-Torres et al. 2020; Meglio 2020). Two noteworthy studies, Deng et al. (2013) and, more recently, Zhang et al. (2022), have indicated a positive relationship between CSR performance and value creation in the context of Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) for the US and selected international markets, respectively. CSR performance could be expected to impact M&A success due to its potential to foster positive stakeholder reactions that, for example, facilitate integration and reduce associated costs, which can serve as an optimistic signal to investors (Zhang et al. 2022). CSR could, however, also be perceived negatively for M&A success (Meckl and Theuerkorn 2015), as, for instance, high CSR standards could make integrating the target more difficult and costly, and a focus on CSR efforts could potentially divert management’s attention from a rigorous M&A execution process.

While there is isolated evidence for the US and selected international markets, to the best of our knowledge, there is no study examining this relationship within the German market, which ranks among the world’s largest economic centers. Furthermore, existing studies lack a rigorous discussion of potential positive and negative effects of CSR performance on investor perception in an M&A context. Thus, this paper aims to determine the reasons for as well as the extent to which short-term shareholder value creation through M&A is attributable to an acquiring company’s level of CSR. More specifically, our empirical analysis focuses on the influence of CSR performance on abnormal stock returns of an acquiring company around M&A announcements.

Consequently, the following two research questions have been developed to conduct an empirical analysis:

- 1.

- What are potential positive and negative effects of CSR investments by the acquirer in an M&A surrounding?

- 2.

- Does an acquiring company’s level of CSR influence abnormal stock returns in the context of M&A announcements in Germany?

We use environmental, social, and governance (ESG) scores to measure a firm’s CSR performance and thus follow previous research and existing investment practices (Krishnamurti et al. 2020; Tampakoudis et al. 2021; Barros et al. 2022; Damtoft et al. 2024). Investors, analysts, and fund managers consider CSR more as company-specific branding. Therefore, they use ESG criteria to analyze securities to obtain quantifiable sustainability measures. In their view, ESG criteria allow for fully capturing corporate sustainability’s holistic nature in a standardized and comparable framework (Walz 2019).

The main objective of our analysis is to discuss and examine the relationship between a company’s level of CSR and short-term potential value creation, measured by the adjustment of stock prices following the M&A announcement. To investigate this, we used event study methodology to quantify the financial impact of 231 M&A transactions by German acquirers on short-term value creation from 2017 to 2022. Furthermore, we divided our observation period into two subsamples, pre-COVID-19 and interim-COVID-19, to control for effects from the pandemic. Our results show that the M&A transactions of German-listed acquirers yielded a slightly negative CAR for event windows of 3 and 11 days, respectively, but in both research settings, without statistical significance. Applying multiple regression analysis, we found no evidence that CSR performance positively influences abnormal stock returns following M&A announcements for the covered period. We conclude that, for the German market, we cannot confirm the positive findings observed in the US market by Deng et al. (2013) and in a broader international sample by Zhang et al. (2022), casting doubt on the generalizability of their results. Supported by a comprehensive discussion of potential effects, we conclude that the positive and negative effects of CSR on the value perception of investors around M&A announcements seem to offset each other. Consequently, we suggest that decision-makers should not rely heavily on CSR-related measures as value-adding investments.

Our study contributes to the existing literature in two ways. First, only a few empirical studies analyze the relationship between CSR and the financial performance of German-listed firms (Fischer and Sawczyn 2013; Velte 2017). No empirical research has examined the relationship between CSR and value creation in German M&A using announcement effects. Thus, our work aims to fill this gap in the existing literature for developed countries and complements the existing research by providing results from German data. Second, our analysis provides a comprehensive discussion of both the potential positive and negative effects of CSR investments by acquirers in an M&A context. While existing studies have typically adopted a single perspective or argument for hypothesizing an impact on corporate transactions (e.g., Zhang et al. 2022), we have not found any study that has comprehensively discussed both views, providing an overview of the entire setting in the CSR-M&A context and arguing for a counterbalancing net effect.

Focusing on Germany as a representative developed country in the EU and using a sample period from 2017 to 2022, our study examined a region and a period subsequent to the introduction of a new EU-wide regulation on CSR reporting, the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) (Directive 2014/95/EU). The aim of this regulation is to require larger companies in the EU to report environmental, social, employee, human rights, anti-corruption, and bribery matters in order to promote better CSR performance. Implementing the NFRD was regarded as a significant step towards greater business transparency. The new directive became effective in 2018, reporting for the first time for the 2017 fiscal year.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical framework and the hypothesis’s development and reviews the extant literature on the association between CSR and financial performance. Section 3 describes the sample selection and methodological approach. Empirical results, their interpretation, and the illustration of the limitations will be presented in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 concludes the analysis.

2. Theoretical Framework and Related Literature

Research examining the relationship between CSR and a company’s financial performance draws on several theoretical arguments centered around the balance of interests among various stakeholder groups, resulting in an ambivalent view.

The so-called shareholder expense view suggests that managers may act in the interests of other stakeholders, neglecting the interests of shareholders (Deng et al. 2013). Scholars following this view suggest a negative association between CSR investments and a firm’s financial performance and argue that engaging in socially responsible activities results in additional costs, representing a waste of valuable resources (Cho et al. 2021). Tampakoudis and Anagnostopoulou (2020) explained that when CSR investments are perceived by investors as an agency cost caused by managers, they have a negative impact on financial performance. These costs put firms at a competitive disadvantage compared to other, less socially responsible firms (McGuire et al. 1988). For instance, Waddock and Graves (1997) considered the decision to invest in pollution control equipment when other firms do not as an example of a cost-incurring action. The added costs may also result from making extensive charitable contributions, promoting community development plans, maintaining plants in economically depressed locations, and establishing environmental protection procedures (McGuire et al. 1988). In addition, concern for social responsibility may limit a firm’s strategic alternatives. A company, for instance, may refrain from certain product lines, such as weapons or pesticides, and avoid plant relocations and investment opportunities in specific locations (McGuire et al. 1988). The suggestion of a negative link between CSR and financial performance aligns with Friedman’s doctrine and other neoclassical economists’ arguments. Friedman (1970) claimed that firms have minimal ethical obligations besides following the law and maximizing profits. Hence, firms are not obliged to invest in socially responsible activities as they mainly incur costs and, thus, reduce profits and shareholder wealth. According to Friedman (1970), managers use CSR as a private benefit for pursuing their careers or other hidden agendas at the expense of shareholder wealth. In doing so, they create a conflict of interest (Jiao 2010). Moreover, Zahid et al. (2022a) also emphasized a negative relationship between a company’s ESG activities and corporate financial performance as measured by return on assets (ROA) for a dataset consisting of Western European companies. They also stated that the inverse effect between ESG and financial performance is stronger when a Big Four accounting company mandates a company.

In sharp contrast, other scholars analyzing the relationship between CSR and financial performance have argued for a positive relationship. The so-called stakeholder value maximization view postulates a positive effect of CSR activities on shareholder value (Deng et al. 2013; Cho et al. 2021). Based on corporate stakeholder theory, it is argued that CSR activities positively affect shareholder wealth because focusing on the interests of external stakeholders increases their willingness to support a company’s operation (Freeman 1984; Deng et al. 2013). Corporate stakeholder theory relies on the contract theory and the theory of the firm by Coase (1937). It was later expanded by Cornell and Shapiro (1987) and Hill and Jones (1992). According to these theories, the value of a firm depends not only on the cost of explicit claims but also on its implicit claims (McGuire et al. 1988). The firm is described as a nexus of contracts between shareholders and other stakeholders in which each group supplies the firm with critical resources or efforts (Deng et al. 2013). These contributions are received in exchange for claims outlined in explicit contracts (e.g., wage contracts, product warranties) or suggested in implicit contracts (e.g., promises of job security to employees and continued service to customers). At the same time, explicit contracts demonstrate full legal standing, whereas implicit contracts do not.

Consequently, firms can default on their implicit commitments without legal recourse from other stakeholders (Deng et al. 2013). Hence, the value of implicit contracts depends on other stakeholders’ expectations about a firm honoring its commitments (Cornell and Shapiro 1987). Because firms that invest more in CSR appear to have a more substantial reputation for keeping their commitments, stakeholders of these firms are more likely to contribute resources and efforts to the firm (Aktas et al. 2011; Deng et al. 2013). As a result, they would be willing to accept less favorable explicit contracts than stakeholders of low CSR firms. Focusing on stakeholders’ interests increases their willingness to support a firm’s operations, which may increase shareholder wealth (Deng et al. 2013). In practice, firms that satisfy stakeholders’ expectations and needs may benefit from increased sales (Ambec and Lanoie 2008), decreased costs (Porter and van der Linde 1995), reduced financial risk (Godfrey et al. 2009), and improved reputation (Brammer and Millington 2005). Thus, firms perceived as high in CSR may benefit from more low-cost implicit claims than other firms, potentially leading to better financial performance for these companies. In this context, Edmans (2011) also argues that, consistent with human capital-centered theories of the firm, employee satisfaction as one dimension of good CSR performance should be positively correlated with shareholder returns.

Moreover, a company’s commitment to socially responsible activities may improve its standing with critical external stakeholders such as bankers, investors, and government officials. This may lead to additional economic benefits for the company. For example, Spicer (1978) reported that banks and other institutional investors acknowledge that social considerations play a substantial role in their investment decisions. Therefore, a high CSR commitment may facilitate a firm’s access to sources of capital and reduce its cost of capital (El Ghoul et al. 2011; Cheng et al. 2014; Goss and Roberts 2011; Ye and Zhang 2011).

Other theoretical concepts are related to the direction of causality between CSR and financial performance. Waddock and Graves (1997) called them slack resources and good management theories. One view is that better financial performance enables firms to use slack resources for investments in their social performance (Waddock and Graves 1997). Hence, better financial performance predicts superior CSR performance if slack resources are allocated to firms’ social activities. The good management theory, on the contrary, reverses this cause-effect relationship. It argues that good CSR performance leads to superior financial performance of the firm. As attention to CSR improves relationships with key stakeholder groups (e.g., employees and customers), better financial performance is achieved through greater stakeholder engagement and resource commitment. It manifests as increased sales or reduced costs (Waddock and Graves 1997), which is largely in line with the above-mentioned stakeholder value maximization view. A moderating effect on the part of the CEO and his characteristics between corporate financial performance and CSR performance also seems to be significant (Zahid et al. 2022b). This is, of course, relevant, as members of the board, particularly the CEO, are responsible for strategic decisions, which include M&A activities as well. Furthermore, based on the tournament theory, incentives can motivate CEOs to act more socially responsible, leading to higher CSR commitment of the company and positively affecting corporate social responsibility performance (Khan et al. 2022).

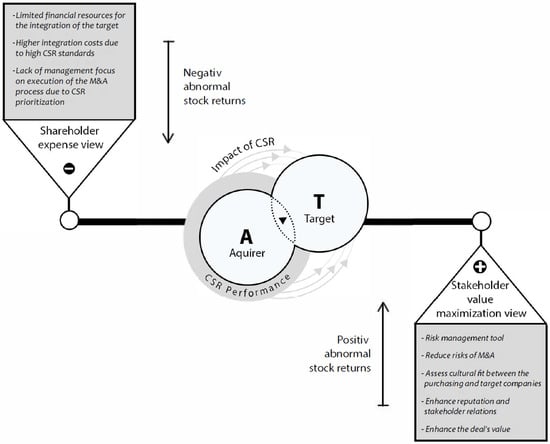

The latter argument also paves the way for linking M&A success with CSR performance. M&A deals are essential investment decisions that can substantially impact shareholder value. However, it could be unclear whether this effect is positive or negative against the background of the two competing theories, namely the shareholder expense view and the stakeholder value maximization view. We summarize the competing opinions in Figure 1 and elaborate on them in the following.

Figure 1.

Potential impacts of CSR on acquirer’s stock performance in the case of an M&A announcement in the short run.

According to the shareholder expense view, socially responsible activities incur additional costs and put the company at a competitive disadvantage, which could negatively affect the acquirer’s financial performance. Companies heavily investing in CSR initiatives might face financial constraints, potentially limiting their ability to properly integrate the target, leading to negative perceptions among investors.

Furthermore, investors might anticipate a higher integration cost due to additional expenses for alignment and standardization caused by the acquirer’s high CSR standards. For instance, extensive reporting requirements naturally entail time-intensive tasks, require significant employee capacity, and consequently result in high costs.

Finally, prioritizing CSR efforts could potentially divert management’s attention from a rigorous M&A execution process. M&A transactions inherently demand substantial managerial involvement and oversight, often requiring exhaustive due diligence, strategic planning, and seamless integration efforts. These tasks necessitate a considerable allocation of resources, time, and expertise from top management. As M&A requires meticulous attention to detail and swift decision-making, any diversion of managerial focus towards CSR activities could potentially dilute the effectiveness of the M&A process, leading to negative investor perception.

On the contrary, following the stakeholder maximization view, investor perception of merger activities might be positive. M&A transactions often involve different groups of stakeholders whose approval or support is required for making a decision. Consistent with good management theory, companies with strong CSR performance tend to have better reputations and stakeholder relations. In an M&A situation, stakeholder interests may be damaged (Segal et al. 2021). However, positive relationships between management and stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, and employees, can increase the likelihood of a positive reaction from stakeholders to the M&A announcement. Support from these stakeholders for a transaction can be a strong positive signal for investors and enhance the M&A announcement effect.

In addition, CSR can be used to assess the cultural fit between the purchasing and target companies. Since there is a high interdependence between a company’s culture and its engagement with CSR, by evaluating CSR performance, companies can identify potential cultural differences or synergies between the two organizations (Meckl and Theuerkorn 2015). This can help facilitate the integration process and reduce post-merger integration costs. As a result, investors could anticipate a smoother integration and, consequently, factor the higher probability of M&A success into their reaction to the deal announcement.

Moreover, CSR can act as a risk management tool during M&A transactions and thus help reduce transaction costs. Companies can identify and mitigate potential ecological and social risks associated with the target company by considering CSR factors as part of the due diligence process. This can help reduce uncertainty for shareholders of the acquiring company and increase the chances of a successful M&A transaction (Gomes and Marsat 2018; Meckl and Theuerkorn 2015).

In conclusion, considering the two contrasting views, both positive as well as negative arguments hold validity. It thus seems reasonable to suggest that they could potentially outweigh each other, resulting in a net effect where neither a positive nor negative impact on investor perception of CSR activities in the context of M&A is observed. This leads us to the following hypothesis, which we test for the German market in this study:

An acquiring company’s level of CSR does neither positively nor negatively influence investor perception in the context of M&A announcements.

Consistent with the conflicting predictions of the contrasting theories, it is not surprising that the empirical results to date are also ambiguous and need further rigorous validation. Previous research has yielded mixed findings on the relationship between a firm’s level of CSR and its financial performance. The extensive body of literature in this research field can be divided into two strands of empirical studies. The first type of study investigates the relationship between CSR and long-term financial performance (McWilliams and Siegel 2000). Long-term financial performance is usually determined by using accounting or market-based profitability measures. For instance, early works by Aupperle et al. (1985) did not observe any relationship between CSR and profitability. More specifically, a correlation between varying levels of social orientation and performance differences was not found (Aupperle et al. 1985). These findings are consistent with Arlow and Gannon’s (1982) conclusion that research studies have not strongly supported a positive association between profitability and CSR. Several more recent studies have come to similar conclusions, finding no or rather negative relationships while using various financial performance measures and samples (Brammer et al. 2006; Makni et al. 2009; Lima et al. 2011; Van der Lann et al. 2008).

Other studies from this literature strand have indicated an opposing view, postulating a positive relationship between CSR and financial performance (Blanco et al. 2013; Godfrey et al. 2009; Jiao 2010; Tang et al. 2012; Wang and Choi 2013; Hou 2019). Awaysheh et al. (2020) found that best-in-class CSR firms have higher operating performance and relative valuations than their lower-performing counterparts. Jia (2020) found a positive relationship between corporate performance and CSR performance in the Chinese market, but this only holds for companies prioritizing customer value and other stakeholders over shareholders.

In addition to investigating the financial impacts, other studies have analyzed the direction of the relationship between firms’ CSR levels and financial performance to make a statement about the causalities. For example, early works by McGuire et al. (1988) assessed financial performance using stock market returns and accounting-based measures. Their findings showed that a company’s prior financial performance is more closely related to CSR than its subsequent performance (McGuire et al. 1988). Similarly, Waddock and Graves (1997) and Scholtens (2008) discussed this reverse causality problem and provided evidence that CSR performance positively correlates with prior financial performance. This suggests that it is not CSR performance that drives financial performance but that companies with above-average financial performance use their surplus of monetary or non-monetary resources to improve their CSR performance further (Makni et al. 2009; Fischer and Sawczyn 2013). Aktas et al. (2011), however, criticized that the question of the direction of causation has not been sufficiently clarified in the literature.

A second strand of empirical literature takes an alternative methodological approach. These studies recognize that analyzing the causes and drivers of financial performance is a complex task as numerous factors influence financials, and the level of CSR is only one of them. Consequently, these studies use event study methodology to focus on short-term financial performance to avoid blurring effects over the long term. On the other hand, even appropriate tools to identify an event’s financial implications and avoid the investigated relationships are overshadowed by other effects over a more extended period. Consequently, these studies turn to M&A deals to investigate the link between CSR and financial performance. Furthermore, as M&A deals can be described as somewhat unanticipated events, the event study methodology is also suitable to mitigate the reverse causality problem of previous studies mentioned above (Deng et al. 2013; Cellier and Chollet 2016). Aktas et al. (2011) addressed this problem by analyzing the targets’ CSR levels instead of the commonly used CSR levels of the acquirer.

The first study to employ an event study using announcement effects of acquirers in an M&A context to analyze the relationship between CSR and financial performance was conducted by Deng et al. (2013). In this context, the authors examined a large sample of mergers in the United States (US) between 1992 and 2007. The authors provided evidence that, compared to low-CSR acquirers, high-CSR acquirers realize higher stock returns following a merger announcement. Thus, their findings support the stakeholder value maximization view of stakeholder theory. A more recent study by Zhang et al. (2022) analyzed a broader international sample including 23 developed economies. They came to a similar conclusion when analyzing 1310 M&A transactions between 2002 and 2012. Their results showed that high CSR acquirers generally achieve positive abnormal announcement returns. The returns are, however, negative when the acquisitions are hostile (Zhang et al. 2022).

Moreover, Krishnamurti et al. (2020), as well as Tampakoudis and Anagnostopoulou (2020), provided additional studies for the US and the European market, respectively, documenting a positive relationship between companies’ CSR level and value creation for their shareholders. However, these studies did not use announcement effects but focused on long-run stock returns and post-acquisition Tobin’s Q. Krishnamurti et al. (2020) suggested that the value creation is primarily attributable to the low bid premiums that socially responsible firms pay for their targets. In a substream of this literature strand, a minority of studies have used the target’s CSR performance instead of the acquirer’s, which they justified with the directional causality problem. Aktas et al. (2011) analyzed target CSR levels in a sample of 109 transactions from 1997 to 2007 and concluded that acquirer abnormal returns are positively associated with the targets’ social and environmental performance. Similarly, Cho et al. (2021) found that higher CSR performance of a target firm creates value for M&A bidders. Finally, Teti et al. (2022) found, for a small sample of 73 M&A deals in 20 different countries, that the market values positively affect the acquisition of a company that scores high in ESG. However, the individual ESG factors have different relevance in explaining the market reaction. In summary, concerning target CSR performance, there appears to be a consensus in the limited literature that higher-CSR targets represent value-enhancing investment opportunities for buyers.

However, contrarian evidence was provided by Meckl and Theuerkorn (2015) for acquirer CSR performance. The authors found no correlation between CSR and announcement returns and suggested that “a business case for CSR regarding M&As cannot be made” (Meckl and Theuerkorn 2015, p. 224). Likewise, Yen and André (2019) found no significant relationship between CSR levels and deal announcement effects for a sample of 23 emerging markets. They concluded that M&As depend mainly on investors’ cost–benefit concerns instead of CSR performance. A study by Fatemi et al. (2017) observed, for a Japanese sample, that the ESG performance of Japanese acquirers exerted no statistically significant influence on abnormal returns. Also, Li et al. (2019) found no effect from CSR on M&A announcement returns for a Chinese sample of 3500 firms. Furthermore, Tampakoudis et al. (2021) even found a significant negative value effect of ESG performance for the shareholders of 889 acquiring US firms. The authors argued that firms ignore the cost-benefit criterion and overinvest in CSR, suggesting that the market considers sustainability activities too costly, especially during economic downturns. They concluded that the market rewards low-CSR-acquiring firms (Tampakoudis et al. 2021).

Regarding German-listed firms, empirical research is very limited. The few existing studies have followed the first literature stream that regressed CSR and accounting-based financial performance measures. Fischer and Sawczyn (2013) and Velte (2017) used German samples and found strong support for a significant positive interaction between CSR and financial performance. The findings of Fischer and Sawczyn (2013) pointed out that the positive link was also affected by the degree of companies’ innovation. Similar to the results by Waddock and Graves (1997), the authors provided further support for a unidirectional, causal relationship between prior financial performance and CSR.

Moreover, Velte (2017) reported that CSR positively affected Return on Assets (ROA). However, there was no impact on Tobin’s Q. When decomposing CSR into its underlying components, the governance performance dimension appeared to exert the most decisive influence on a firm’s financial performance compared to the environmental and social performance dimensions (Velte 2017). Regarding the second strand of literature mentioned above in this field, no studies have yet analyzed M&A announcement effects to examine the relationship between CSR and value creation in Germany.

To conclude, an extensive body of theoretical frameworks and empirical studies present various notions and findings regarding the link between CSR and financial performance, but with ambiguous results. While some studies did not find positive relationships between CSR levels and financial performance, others have postulated positive associations, albeit with partially unclear causal directions. The meta-analyses (Orlitzky et al. 2003) and literature studies (Van Beurden and Gössling 2008) suggest a majority of positive relations between CSR and financial performance, but they do not include more recent research.

The contradictory findings in the literature regarding the impact of CSR on financial performance and, in particular, on M&A announcement effects appear to further reinforce the hypothesis stated above, suggesting that positive and negative effects could counterbalance each other. We speculate that these results ultimately mirror the conflicting perspectives of the stakeholder value maximization and the shareholder expense view.

Given the ongoing debate and the apparent absence of empirical studies focusing on the German market, this study sought to address the unresolved dilemma and complement the existing evidence with German data. To this end, we examined the relationship between CSR performance and M&A outcomes using a sample comprising M&A transactions in Germany spanning from 2017 to 2022. By conducting this investigation, our aim is to contribute to the existing literature by filling this significant gap in empirical research for the German market.

3. Data and Methodology

We chose DAX-listed firms as they account for around 80 percent of the total market capitalization of all listed companies in Germany, providing a representative view of the German market (Börse Frankfurt 2023). We measured the CSR engagement of a firm using ESG scores, aligning with prior studies that have evaluated a company’s CSR engagement level through its ESG score (Deng et al. 2013; Velte 2017; Broadstock et al. 2020; Tampakoudis et al. 2021). ESG scores are considered objective assessments of a company’s commitment to sustainable business practices and are common practice in CSR literature. The set of M&A transactions and companies’ ESG scores were derived from the data provider FactSet. The FactSet database collects comprehensive information regarding each M&A transaction, including the announcement date, transaction value, and deal description. In addition, acquirer-related information, historical stock prices, and market index prices were retrieved. The ESG scores provided by FactSet are composed of five dimensions: environment, social capital, leadership and governance, human capital, and business model and innovation. The selection of control variables (industry, year, transaction value, listed target) followed the study conducted by Masulis et al. (2007). The target company status (public or private target) was included in the regression model because it appears to be a crucial driver of acquirer returns (Hazelkorn et al. 2004). In most cases, a target status of private was also responsible for a lack of ESG score data. As information on deal value was not disclosed for all transactions identified between 2017 and 2022, deals were classified into major deals (≥500 million euros) and minor deals (<500 million euros). This approach aligns with the study by Alexandridis et al. (2017), which provided evidence for more shareholder value creation among larger deals. The sample of transactions was selected following these criteria:

- The initial sample included all M&A transactions sourced from FactSet, in which German DAX-listed companies acted as the acquirers in the transaction. The considered German firms have been part of the German index throughout the covered period from 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2022.

- Acquiring firms within the banking, financial services, and insurance sectors were excluded. The company identification used by the Frankfurt Stock Exchange was adopted to identify the company’s sector. The reason to exclude firms that belong to the banking, financial services, and insurance sectors is because capital requirements and cash policies regulate them. These firms have considerably different capital structures with high liquidity and leverage. This makes them less comparable to the rest of the sample companies. The exclusion of financial intermediaries aligns with numerous previous studies (e.g., Deng et al. 2013; Mager and Meyer-Fackler 2017).

- The M&A transactions must be announced between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2022, and their deal status must be completed.

- The acquiring firm holds less than 50% before the transaction is announced.

- M&A transactions whose announcement dates and event windows interfered with each other were excluded due to a possible bias effect on the results.

- Complete information regarding stock returns, market betas, and ESG scores must be available for all companies in the FactSet datasheet, creating a homogeneous data sample.

Table 1 summarizes the individual steps of the sample selection process.

Table 1.

Sample selection process.

Occasionally, overlapping event windows were apparent in the dataset. Abnormal stock returns from overlapping event windows were not uncorrelated. The financial impact of one event will spill over to a second event and multiply the market response. Thus, these observations were dropped from the dataset to avoid distortion of the study results.

Following these selection criteria resulted in a final sample of 231 transactions by 17 German DAX-listed companies (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptives about the acquiring firms.

For the regression analysis, the sample was further reduced to 56 M&A transactions as the parties involved in a deal do not usually disclose the transaction value, limiting the sample for this particular analysis.

Essentially, two methods exist in the current literature to measure value creation from M&A: event studies and accounting studies. The event study is a forward-looking, direct measure of value creation based on market returns. On the contrary, accounting studies are based on reported financial statements and measure returns through historical accounting figures. Thus, the disadvantage of this approach is the backward-looking nature of the variables used to compute stock returns. Additionally, previous studies on the relationship between CSR and firm value have suffered from a reverse causality problem (Waddock and Graves 1997; McWilliams and Siegel 2000). However, applying the event study methodology can potentially mitigate this, as M&A transactions are largely unanticipated events (Deng et al. 2013; Cellier and Chollet 2016; Teti et al. 2022).

Return event studies have captured the stock market reaction and, thus, investors’ perception of a specific event. In the context of this paper, this is the M&A announcement. An event’s financial impact is quantified in abnormal returns (AR). The AR is the difference between the actual realized return and the return without the M&A announcement (Wang et al. 2020). The analysis employs the market model by Brown and Warner (1985) for calculating the return without an M&A announcement.

Rt and Rmt denote the company-specific stock return and the market return, respectively. α and β are the two parameters determining the linear relationship between company-specific return and overall market return. The residual is the error term. In the market model, the expected value of is presumed to be 0. Therefore, the expected return of the stock for the event date is:

The CAPM was applied as a prediction model for the market model by Brown and Warner (1985) in this paper:

Rf indicates the risk-free rate, while βi and Rm represent the company’s beta and the market return, respectively. Hence, the AR for each event date is:

To quantify the impact of an event over a time period, daily abnormal stock returns were cumulated to obtain the cumulative abnormal return (CAR). Thus, CAR is the sum of AR over the event window, stretching from the day before the merger announcement t (−1) to the day after the merger announcement t (+1).

More specifically, this paper computed the abnormal stock returns in three steps. First, the event date and the event window were defined. The exact event date for each transaction was the announcement date of the M&A deal. t0 denotes the event date. If the announcement occurred on a non-trading day, the following trading day was considered the event date. In line with Zhang et al. (2022), Hackbarth and Morellec (2008), and Alexandridis et al. (2017), an event window of 3 days [−1, +1] was incorporated in this study to examine the short-term value creation following the M&A announcement. Like Deng et al. (2013), a longer event window of 11 days was also applied to further test the robustness of the results and for comparability reasons. This event window included several days before the announcement due to the possible occurrence of information leakage and rumors. Furthermore, as the market reaction following the announcement might last several days, the days after the event date were also included to capture the short-term value creation (Aggarwal and Chen 1985). We used short-term event windows to accurately reflect the shareholder value creation from M&A deals in the short run (Andrade et al. 2001). Longer event windows that include more days are not optimal because they may increase the likelihood of noise and influence from other factors (MacKinlay 1997). Additionally, the error term in short-term studies is smaller, and the corresponding computation of abnormal stock returns is more accurate than in long-term studies (Kothari and Warner 2007).

The second step was to compute each transaction’s expected return, AR, and CAR. Then, the normal return was estimated using the parameters of the CAPM. The risk-free rate was approximated using the yields of 10-year German government bonds. The yearly average values of their betas were employed to assess the systematic risk associated with individual companies. The DAX index’s daily return served as the market proxy. We used an estimation window of 200 days for estimating the expected returns.

In the last step, several statistical tests and regression analyses were performed. To investigate the value effects of CSR, we analyzed the market’s reactions to the ESG scores. We used the following regression equation:

where CARi,t is the cumulative abnormal return of acquirer i on date t, ESGi,t is the ESG score for acquirer i, IND is the control variable Industry, YEAR is the control variable Year of the deal, TV is the control variable Transaction value for potential deal size effects, LT is the control variable Listed target (public or private), and ε is the random disturbance term.

t-tests were conducted to test whether the mean CAR for the two event windows of 3 and 11 days significantly differed from 0. In addition, the Wilcoxon test was used to examine the significance of the median CAR.

Before the regression analysis, several necessary assumptions were tested to ensure the model’s validity. First, the regression model was tested for multicollinearity; we found no evidence for multicollinearity. The correlation among the independent variables was within the acceptable threshold of less than 0.7. Second, the sample was inspected for possible outliers by performing a Cook’s Distance test. Computing Cook’s Distance resulted in minimum and maximum values of 0.000 and 0.394, respectively. In addition, the Cook’s Distance values were visually inspected via a scatter plot in which no data point appeared to be an extreme outlier. Subsequently, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were performed to analyze the residuals’ normal distribution. Both tests assumed a normal distribution in their null hypothesis, which could be retained with p-values larger than 0.05. Both tests were insignificant and, thus, could not reject the null hypothesis.

Furthermore, a visual examination was undertaken. The data points followed approximately along the diagonal in the Q-Q plot. Similarly, the histogram indicates an approximate normal distribution. Based on the analytical and graphical indications, normally distributed residuals are assumed to exist. Afterward, the regression model was tested for signs of heteroskedasticity. Based on a visual inspection, it can be observed that the values were within −3 and 3 in the scatter plot of residuals. In addition, the data points were randomly distributed and did not appear in a specific pattern. The modified Breusch–Pagan test further investigated a potential heteroskedasticity’s existence. The test was insignificant and provided no evidence for heteroscedasticity. Finally, the Durbin–Watson statistic was computed to test for possible first-order autocorrelation of the residuals. The output showed a value of 2.481, within the acceptable range between 1.5 and 2.5. Therefore, no autocorrelation was assumed to exist among the residuals. Consequently, we assumed a linear multiple regression could provide valid results based on these different test procedures.

4. Results and Discussion

Table 3 shows the mean and median CAR values for this study’s two applied event windows.

Table 3.

Means and medians of CAR for the selected event windows over different observation periods (in percent).

Both event windows yielded a negative mean of −0.13% for CAR [−1, +1] and −0.25% for CAR [−5, +5] over the complete observation period. However, the results were not statistically significant. At the very least, it could be assumed that the stock market did not react positively in the short run to M&A transactions of DAX-listed acquirers in the sample. This is in line with the majority of existing studies on short-term value creation from developed economies that document mainly negative announcement effects (e.g., Healy et al. 1992; Andrade et al. 2001; Campa and Hernando 2004; Hazelkorn et al. 2004; Conn et al. 2005; Hackbarth and Morellec 2008; Alexandridis et al. 2012; for the German market: Mager and Meyer-Fackler 2017). Only recently, however, isolated studies have come to more positive results, such as Alexandridis et al. (2017), which found evidence of positive value effects for acquiring firm shareholders in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

In a similar vein, when examining the mean CAR for each year throughout the designated period, we observed positive (but not significant) value creation effects of 0.07% for CAR [−1, +1] and 0.55% for CAR [−5, +5] in the year 2021 following the disruptive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. These effects were observed across both event windows, partially supporting the earlier conclusions by Alexandridis et al. (2017). Their research proposed a rapid recuperation in the value creation effects of acquiring firm shareholders following a period of economic turmoil. In the other years, we saw predominantly negative CAR values without statistical significance. To conclude, there was at least little evidence of positive effects on the announcements of M&A transactions. A similar pattern emerged when examining a pre-COVID-19 (2017–2019) and an interim-COVID-19 (2020–2022) subsample regarding CAR values. Although not statistically significant, there were indications that the negative effect persisted. At least, there were scarcely any indications that positive effects had emerged. There were no differences between the two subsamples (see Table 3). Additionally, no significant outliers existed in any of the data periods considered.

In the next step, we used multiple linear regression (see Table 4) to investigate the relationship between the announcement effect and the CSR performance of the firms in our sample, as well as several control variables (industry, year, transaction value, and listed target). A detailed collinearity diagnosis was performed to examine potential adverse effects on the regression results closely. However, the dataset did not reveal signs of multicollinearity. Furthermore, the regression model was tested for outliers, heteroskedasticity, and possible first-order autocorrelation of the residuals. We found no limitations in performing the regression.

Table 4.

Model summary of regression analysis (meta ESG score).

As the indicator variables, Industry and Year have ten (number of industries in the sample) and six (number of years in the sample) levels, respectively; the Chemicals industry and the Year 2017 are set as the reference categories in the regression analysis. To determine an overall significant relationship between the dependent variable and the set of explanatory variables, an F-test was conducted, yielding a value of 0.781. The ANOVA output disclosed a significance value of 0.697 and was not statistically significant. Therefore, the selected independent variables, including the ESG score and several control variables, do not significantly impact abnormal stock returns following an M&A announcement. The adjusted coefficient of determination R2 value of negative 0.068 states that the model cannot explain the variance of the dependent variable. A possible explanation for the model’s poor fit might be that the selected explanatory variables do not appropriately reflect changes in abnormal stock returns. As a result, ESG scores, as a proxy of firms’ level of CSR, are not statistically relevant to the creation of short-term shareholder wealth.

The ESG scores used in our regression were aggregated factors of different ESG dimensions. The ESG scores we used were composed of five individual elements provided by FactSet: (1) Business Model and Innovation, (2) Environment, (3) Leadership and Governance, (4) Human Capital, and (5) Social Capital. In a further regression, we replaced the “meta-ESG score” used in the first regression and included the five individual scores for each company. The results can be found in Table 5, where it can be seen that the individual observations also showed no significant correlations. This confirms the results from the first regression model.

Table 5.

Model summary of regression analysis (five ESG dimensions).

Thus, concerning our research question, we did not find any evidence of a significant positive or negative relationship in our sample of German M&A transactions between the level of CSR, measured by the corresponding ESG score, and value creation. This result confirms our hypothesis that an acquiring company’s level of CSR does neither positively nor negatively influence investor perception, as measured by abnormal stock returns in the context of M&A announcements.

Our research adds new evidence to the still ambiguous results in the existing literature and contributes to the discussion on the potential influence of CSR in M&A transactions. Our work is the first paper that analyzes the relationship between CSR performance and value creation for the German market, using transaction data from M&A deals. In essence, the findings of this paper contradict recent study results arguing for a positive correlation between the acquirer’s CSR level and abnormal stock returns after the M&A announcement. The works by Deng et al. (2013) and Zhang et al. (2022) found positive value effects for the US and for an international sample of developed countries. However, our sample did not provide evidence for such a correlation regarding German-listed firms between 2017 and 2022.

While our findings contradict the abovementioned studies, they do not stand alone. They align with early results of Arlow and Gannon (1982) and Aupperle et al. (1985), who did not find a statistically significant relationship between CSR and financial performance. More recently, and in alignment with our hypothesis, Meckl and Theuerkorn (2015) also found no statistical correlation between the CSR dimension and abnormal returns. Moreover, our results are consistent with the study conducted by Fatemi et al. (2017) for a Japanese sample. The authors observed that the ESG performance of Japanese acquirers exerts no statistically significant influence on abnormal returns. They explained this finding by arguing that Japan’s market for corporate control has become more competitive and, consequently, behaves now similarly to those of Western countries. Furthermore, our results are consistent with a recent study for the Chinese market (Li et al. 2019) and a study using a sample of 23 emerging markets (Yen and André 2019). Likewise, Tampakoudis et al. (2021) investigated the relationship between ESG performance and abnormal announcement returns for a similar recent period. However, they used a slightly different research design, primarily focusing on differences in shareholder wealth creation before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and their sample included only US firms. The authors did not find a significant positive value effect of ESG performance on acquiring shareholders independently from the COVID-19 pandemic (Tampakoudis et al. 2021). Our findings confirm the results of these studies.

Thus, based on the findings of our study for the German market and the results reported in other regions, the positive results presented by Deng et al. (2013) and Zhang et al. (2022) may ultimately prove to be isolated statistical artifacts. Despite the smaller dataset and the focus on the German M&A market, our results cast doubt on the generalizability of the findings in the works of Deng et al. (2013) and Zhang et al. (2022). Possible differences could arise from the varying study periods, which at least call into question the time-independence of the results. Additionally, Zhang et al. did not provide separate results for the regions included in their sample, leaving room for speculation about contradictory or insignificant outcomes within their international sample. Differences in the industrial composition of the markets considered, or generally differing M&A markets with regard to investor culture, could also explain the discrepancies in the results.

In conclusion, we found no evidence that would either support positive effects from the stakeholder value maximization view or negative effects from the shareholder expense view. The stakeholder value maximization view, on the one side, argues that CSR performance may positively impact M&A through benevolent stakeholders supporting a deal and through intensified analyses of cultural fit and other risk factors such as ecological or social risks. In an M&A setting, in high-CSR firms, this positive effect should be visible in better financial performance and positive investor perception since benevolent stakeholders may often influence decisions in such transactions and play an important role in post-merger integration (Deng et al. 2013). However, we did not find evidence that confirms this view. On the other side, we also did not find evidence that would support the negative effects suggested by the shareholder expense view. This view suggests that engaging in socially responsible activities can incur additional costs, potentially putting a company at a competitive disadvantage. Companies that heavily invest in CSR initiatives might face financial constraints, which could hinder their ability to effectively integrate acquisition targets. Furthermore, investors might anticipate higher integration costs due to the need for alignment and standardization of CSR practices. Lastly, prioritizing CSR efforts could divert management’s attention from the rigorous execution required in M&A transactions. In summary, these negative effects should result in negative investor perceptions.

While we believe that the arguments from both contrasting views hold logical validity, we conclude that both effects exist but balance each other, thus confirming our hypothesis. As demonstrated in Figure 1, there are positive effects from CSR activities and negative effects from CSR activities that should be considered by investors. We believe that our results provide evidence that, in the perception of investors, these effects in aggregate cancel each other out, thus leading to insignificant results in our sample. Consequently, the empirical evidence suggests that the market is undecided about CSR’s value-enhancing effects in M&A surroundings.

We acknowledge that alternative explanations could explain our results, as well as the differences observed when compared to the findings of Deng et al. (2013) and Zhang et al. (2022). Different methodological approaches could explain the contradictory empirical results in some of the existing literature. McGuire et al. (1988) pointed out that social responsibility affects firm performance in several ways. Hence, selecting explanatory variables and research design might substantially influence the findings. For instance, a minority of studies have investigated the CSR performance of the target (Aktas et al. 2011; Teti et al. 2022) instead of the acquirer, or the difference between the target’s and the buyer’s CSR levels (Cho et al. 2021). Additionally, the difference in the definition of CSR and ESG might probably be a reason for the difference in the results of various studies. Furthermore, while we believe that the arguments provided in favor and against a value effect of CSR in M&A hold true, practical experience in M&A may suggest different results, overshadowing the effects postulated in Section 2 and summarized in Figure 1. While companies with strong CSR performance may exhibit better relations with stakeholders, as the stakeholder value maximization view suggests, in M&A transactions, other factors such as financial performance, previous integration experience, or shareholders’ perceptions of the takeover price may play a far more significant role. In addition, CSR might not serve as a sufficient measure of cultural fit between the acquiring and target companies. The acquirer’s focus on CSR performance might not necessarily translate into a greater focus on cultural synergies with the target firm, which one might expect to facilitate smoother integration. Likewise, detecting other risk factors, such as ecological or human resource risks, may probably be more influenced by the professional execution of the due diligence process rather than focusing on CSR performance. In sum, these tempering effects could explain the absence of significant positive results.

5. Conclusions

This study explored the potential impact of an acquirer’s level of CSR (measured through its ESG score) on cumulative abnormal stock returns following an M&A announcement. The sample included 231 M&A transactions announced by DAX-listed companies between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2022. While most studies in this research field apply accounting-based, long-term profitability measures, this paper complements the literature focusing on short-term value creation and measuring abnormal stock returns with the event study methodology. Consequently, we assume an investor-oriented perspective in the study. It is the first study that analyzes the relationship between CSR performance and value creation in M&A transactions for the German market after implementing the NFRD in the EU.

Our results contribute to the ongoing debate regarding the crucial and inconclusive question of whether a higher level of CSR is value-enhancing or value-destroying. As the literature remains ambiguous, with several studies finding positive announcement effects for high CSR acquirers (Aktas et al. 2011; Deng et al. 2013; Cho et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2022) and other studies documenting opposing results (Meckl and Theuerkorn 2015; Fatemi et al. 2017; Yen and André 2019; Tampakoudis et al. 2021), we offer a new, balanced perspective on the issue. With our study, we provide an extensive discussion and a comprehensive summary of the potential positive and negative effects of an acquirer’s CSR engagement on value creation in M&A situations. Contrasting, in particular, the findings of Deng et al. (2013) and Zhang et al. (2022), our findings at least cast considerable doubt on the existence of a positive or negative correlation between CSR and value creation in M&A. Adopting a multiple linear regression model, the results could not provide sufficient statistically relevant evidence that a company’s level of CSR positively or negatively affects abnormal stock returns following an M&A announcement. Since both the positive and negative arguments regarding the impact of CSR on M&A transactions hold validity, our results suggest that they potentially offset each other. This balance results in a net effect where neither a distinctly positive nor negative influence on investor perception of CSR activities in the context of M&A is observed. This ambiguity highlights the complex nature of CSR’s role in M&A transactions. On the one hand, CSR initiatives may foster better stakeholder relations, and support from stakeholders such as employees, customers, and suppliers can be a strong positive signal in M&A situations (Deng et al. 2013; Cho et al. 2021; Segal et al. 2021). On the other hand, CSR initiatives involve high costs that could hinder integration efforts, trigger higher costs due to the need for alignment and standardization of CSR practices, and divert management’s attention from the rigorous execution required in M&A transactions (Tampakoudis et al. 2021; Meckl and Theuerkorn 2015). In conclusion, the market appears to be overall undecided about the value-enhancing effects of CSR performance on M&A.

Our findings have important implications. First and foremost, the results of this study suggest that it is not rewarding for equity investors to pay attention to whether increased CSR investments have been made in potentially M&A-active German firms. CSR performance does not appear to be an effective predictor for the acquisition of companies in order to identify value-creating takeovers in Germany. Instead, our results suggest that CSR investments by acquirers imply both positive and negative effects that balance each other out in an M&A context. For fund managers, CSR investments are likewise not a positive trading signal that would promise excess returns, especially not in the run-up to an anticipated acquisition. Second, corporate decision-makers should not view CSR-related measures as value-adding investments. Finally, corporate decision makers should instead consider broader factors beyond CSR initiatives to create shareholder value (Yen and André 2019). They should evaluate the strategic rationale for M&A transactions and consider factors such as the strategic fit of the target company with the acquirer’s business, the impact of the transaction on the company’s overall financial performance, and the proper integration of the target.

Instead, and despite the presented findings of this study, CSR activities continue to be a central part of corporations’ visions and strategies (Cho et al. 2021). As stakeholders globally demand increasing and more detailed disclosure of information regarding a company’s social activities, awareness and sensibility for CSR aspects continue to become a more critical and established tool for companies’ strategic development. While CSR does not appear to pay off for shareholders, corporate leaders must address ongoing challenges such as climate change and increasing pressure from stakeholders to adopt more sustainable business practices. Therefore, German listed firms, specifically, and firms on an international scale should continue incorporating social, sustainable, and ethical standards into their investment decisions. Although CSR activities do not necessarily create immediate value for shareholders in the short run, they have become indispensable to sustainable development, as demanded by policymakers and other stakeholders alike. They could result in value creation in the long run.

Our study may be subject to several limitations, which could pave the way for future research. Initially, 231 corporate transactions were identified that fit the research design. However, many observations did not disclose data on the deal size, resulting in an unbalanced sample and limiting the sample size to 56 M&A transactions in the multiple linear regression model. Although the parties involved in a deal commonly do not disclose the transaction value, this cogitable practice resulted in a relatively small sample size. Thus, it is essential to understand that the research findings must be considered carefully, as they may lack generalizability and validity. This may call for future studies with larger sample sizes. In addition, the covered period (2017–2022) offers limited insights as further regulatory changes in German and European contexts only become apparent in the case of consistent longitudinal data collection. Moreover, analyzing the impact of CSR through ESG scores adds another limitation. The assessment might lack some accuracy due to the slight difference in the definition of CSR and ESG (Barros et al. 2022; Damtoft et al. 2024). However, using ESG scores as a proxy for CSR engagement is common practice in the related literature (e.g., Deng et al. 2013; Velte 2017; Broadstock et al. 2020; Tampakoudis et al. 2021; Barros et al. 2022) and allows for comparisons with former studies. Teti et al. (2022) added that ESG scores are composed of different factors, and disentangling these might lead to differentiated results. Furthermore, other previously applied measures of CSR, such as social audits or CEO surveys, have similar shortcomings. Thus, future research could address this issue by applying alternative measures of a firm’s CSR level, using the difference between an acquirer’s and a target’s CSR performance (Cho et al. 2021), or analyzing the proxies’ validity in general.

An additional limitation could arise from the low cross-company variation in ESG scores. The non-significant results in the regression model could be explained by the relatively low variation between companies in terms of their ESG scores, which makes differentiation difficult and negatively affects possible correlations in terms of significance. Additionally, our sample only contained transactions from German DAX-listed companies. While the German DAX index represents about 80% of the market capitalization of German stock-listed firms, it is still a limited focus. Furthermore, studies focusing on a single region may be subject to distinctive circumstances regarding firms’ CSR awareness and the regulatory landscape. Therefore, it would be interesting to investigate whether one can draw general conclusions for multiple markets or if research findings are only valid for the chosen region. Finally, we cannot control our results for the targets’ ESG scores due to a lack of data on privately held target companies representing most of the targets considered. Future research could add more empirical evidence by additionally considering targets’ CSR performance and investigating whether differences or similarities between ESG scores of the acquirer and the target influence announcement effects (Aktas et al. 2011; Cho et al. 2021; Tampakoudis and Anagnostopoulou 2020).

Against the background of these limitations, and with the literature remaining ambiguous, we suggest further research on the relationship between a company’s level of CSR and both short-term and long-term value creation and the motivation for firms to engage in CSR activities. In this context, collecting more longitudinal data and formulating universally valid statements is essential for researchers and managers. Also, a new study employing a similar research design conducted post implementation of the new EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) from 2024 onward could shed light on the effects of enhanced CSR performance in EU companies on value creation. Finally, researching the relationship between M&A and CSR could be further explored by reversing the causal direction and analyzing the impact that M&A has on CSR (Barros et al. 2022).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.; data curation, J.-L.W.; methodology, J.-L.W.; project administration, M.C.; supervision, M.C.; validation, T.A.H.; visualization, M.C. and T.A.H.; writing—original draft, J.-L.W.; writing—review and editing, M.C. and T.A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available under reasonable request to the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Aggarwal, Reena, and Son-Nan Chen. 1985. The speed of adjustment of stock prices to new information. Financial Review 20: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, Nihat, de Eric Bodt, and Jean-Gabriel Cousin. 2011. Do financial markets care about SRI? Evidence from mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Banking & Finance 35: 1753–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandridis, George, Christos Mavrovitis, and Nickolaos Travlos. 2012. How have M&As changed? Evidence from the sixth merger wave. The European Journal of Finance 18: 663–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandridis, George, Nikolaos Antypas, and Nickolaos Travlos. 2017. Value creation from M&As: New evidence. Journal of Corporate Finance 45: 632–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambec, Stefan, and Paul Lanoie. 2008. Does it pay to be green? A systematic overview. Academy of Management Perspectives 22: 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, Gregor, Mark Mitchell, and Erik Stafford. 2001. New evidence and perspectives on mergers. Journal of Economic Perspectives 15: 103–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlow, Peter, and Martin Gannon. 1982. Social responsiveness, corporate structure, and economic performance. Academy of Management Review 7: 235–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperle, Kenneth, Archie Carroll, and John Hatfield. 1985. An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Academy of Management Journal 28: 446–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaysheh, Amrou, Randall Heron, Tod Perry, and Jared Wilson. 2020. On the relation between corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal 41: 965–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, Victor, Pedro Verga Matos, Joaquim Miranda Sarmento, and Pedro Rino Vieira. 2022. M&A activity as a driver for better ESG performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 175: 121338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, Belen, Encarna Guillamon-Saorin, and Andrés Guiral. 2013. Do non-socially responsible companies achieve legitimacy through socially responsible actions? The mediating effect of innovation. Journal of Business Ethics 117: 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börse Frankfurt. 2023. Facts from More than 35 Years of DAX. Available online: https://www.boerse-frankfurt.de/en/know-how/about/geschichte-der-frankfurter-wertpapierboerse/facts-from-30-years-of-dax (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Brammer, Stephen, and Andrew Millington. 2005. Corporate reputation and philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Journal of Business Ethics 61: 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, Stephen, Chris Brooks, and Stephen Pavelin. 2006. Corporate social performance and stock returns: UK evidence from disaggregate measures. Financial Management 35: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, David, Kalok Chan, Louis Cheng, and Xiaowei Wang. 2020. The role of ESG performance during the financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Finance Research Letters 38: 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Stephen, and Jerold Warner. 1985. Using daily stock returns: The case of event studies. Journal of Financial Economics 14: 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, José Manuel, and Ignacio Hernando. 2004. Shareholder Value Creation in European M&As. European Financial Management 10: 47–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellier, Alexis, and Pierre Chollet. 2016. The Effects of Social Ratings on Firm Value. Research in International Business and Finance 36: 656–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Beiting, Ioannis Ioannou, and George Serafeim. 2014. Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strategic Management Journal 35: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Kyumin, Seung Hun Han, Hyeong Joon Kim, and Sangsoo Kim. 2021. The valuation effects of corporate social responsibility on mergers and acquisitions: Evidence from U.S. target firms. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 28: 378–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, Ronald. 1937. The nature of the firm. Economica 4: 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, Robert, Andy Cosh, Paul Guest, and Alan Hughes. 2005. The Impact on UK Acquirers of Domestic, Cross-Border, Public and Private Acquisitions. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 32: 815–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, Bradford, and Alan Shapiro. 1987. Corporate stakeholders and corporate finance. Financial Management 16: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damtoft, Nadja Fugleberg, Dennis van Liempd, and Rainer Lueg. 2024. Sustainability performance measurement—A framework for context-specific applications. Journal of Global Responsibility, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Xin, Jun-koo Kang, and Buen Sin Low. 2013. Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder value maximization: Evidence from mergers. Journal of Financial Economics 110: 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmans, Alex. 2011. Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. Journal of Financial Economics 101: 621–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, Sadok, Omrane Guedhami, Cuck Kwok, and Dev Mishra. 2011. Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital? Journal of Banking & Finance 35: 2388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, Ali, Iraj Fooladi, and Niloofar Garehkoolchian. 2017. Gains from mergers and acquisitions in Japan. Global Finance Journal 32: 166–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Thomas, and Angelika Sawczyn. 2013. The relationship between corporate social performance and corporate financial performance and the role of innovation: Evidence from German listed firms. Journal of Management Control 24: 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FNG Marktbericht Deutschland. 2023. Available online: https://www.avesco.de/fng-marktbericht-2023-nachhaltige-geldanlagen/ (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Freeman, Edward. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Milton. 1970. A Friedman doctrine—The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. The New York Times. September 13, p. 17. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Godfrey, Paul, Craig Merrill, and Jared Hansen. 2009. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strategic Management Journal 30: 425–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, Mathieu, and Sylvain Marsat. 2018. Does CSR impact premiums in M&A transactions? Finance Research Letters 26: 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzàlez-Torres, Thais, José-Luis Rodríguez-Sánchez, Eva Pelechano-Barahona, and Fernando García-Muina. 2020. A Systematic Review of Research on Sustainability in Mergers and Acquisitions. Sustainability 12: 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, Allen, and Gordon Roberts. 2011. The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. Journal of Banking & Finance 35: 1794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackbarth, Dirk, and Erwan Morellec. 2008. Stock returns in mergers and acquisitions. The Journal of Finance 63: 1213–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelkorn, Todd, Marc Zenner, and Anil Shivdasani. 2004. Creating value with mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 16: 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, Paul, Krishna Palepu, and Richard Ruback. 1992. Does Corporate Performance Improve After Mergers? Journal of Financial Economics 31: 135–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Charles, and Thomas Jones. 1992. Stakeholder-agency theory. Journal of Management Studies 29: 131–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Ronald Paul, Thomas Ainscough, Todd Shank, and Daryl Manullang. 2007. Corporate social responsibility and socially responsible investing: A global perspective. Journal of Business Ethics 70: 165–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Tony. 2019. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and sustainable financial performance: Firm-level evidence from Taiwan. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26: 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Xingping. 2020. Corporate social responsibility activities and firm performance: The moderating role of strategic emphasis and industry competition. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Yawen. 2010. Stakeholder welfare and firm value. Journal of Banking and Finance 34: 2549–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, Sébastien, Saskia Erben, Philipp Ottenstein, and Henning Zülch. 2022. Does corporate social responsibility impact mergers & acquisition premia? New international evidence. Finance Research Letters 46: 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Muhammad, Shahid Ali, Ammar Zahid, Chunhui Huo, and Mian Nazir. 2022. Does Whipping Tournament Incentives Spur CSR Performance? An Empirical Evidence from Chinese Sub-national Institutional Contingencies. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 841163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothari, Sabino, and Jerold Warner. 2007. Econometrics of event studies. In Handbook of Empirical Corporate Finance. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 1, pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, Chandrasekhar, Syed Shams, and Hasibul Chowdhury. 2020. Evidence on the trade-off between corporate social responsibility and mergers and acquisitions investment. Australian Journal of Management 46: 466–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Minghui, Faqin Lan, and Fang Zhang. 2019. Why Chinese Financial Market Investors Do Not Care about Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from Mergers and Acquisitions. Sustainability 11: 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, Vicente, Fátima De Souza, and Felipe Vasconcellos. 2011. Corporate social responsibility, firm value and financial performance in Brazil. Social Responsibility Journal 7: 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinlay, Craig. 1997. Event studies in economics and finance. Journal of Economic Literature 35: 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mager, Ferdinand, and Martin Meyer-Fackler. 2017. Mergers and acquisitions in Germany: 1981–2010. Global Finance Journal 34: 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makni, Rim, Claude Francoeur, and François Bellavance. 2009. Causality between corporate social performance and financial performance: Evidence from Canadian firms. Journal of Business Ethics 89: 409–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masulis, Ronald, Cong Wang, and Fei Xie. 2007. Corporate governance and acquirer returns. The Journal of Finance 62: 1851–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]