Abstract

This review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of the coverage of sustainability reporting (SR) aspects within the corpus of qualitative SR literature. It seeks to elucidate the theoretical and conceptual foundations that have guided the trajectory of the sustainability field and illuminate the qualitative methodologies used in this body of literature. Employing a systematic review methodology, this study undertakes an exhaustive examination of 242 selected empirical studies on sustainability reporting conducted during the period spanning from 2001 to 2022. The noteworthy contribution of this review to the realm of sustainability research lies in its identification of unexplored and underexplored domains that merit attention in forthcoming investigations. These include but are not limited to employee health and safety practices, product responsibility, and gender dynamics. While stakeholder theory and institutional theory have been dominant theories within the selected literature, the exploration of moral legitimacy remains largely underinvestigated. It is essential to underscore that this review exclusively encompasses qualitative studies, owing to the richness and versatility inherent in qualitative research methods. This deliberate selection enables researchers to employ diverse methodological and theoretical frameworks to gain a profound understanding of engagement within the practice of sustainability reporting. This review introduces an interesting approach by considering the thematic scope, as well as theoretical and methodological choices, observed across the selected studies.

1. Introduction

The multitude of environmental, economic, and social crises spanning the last 40 years has precipitated a heightened call for research in the field of SR (Carnegie 2012; Humphrey and Gendron 2015; Unerman and Bennett 2004; Qian et al. 2021). Sustainability reporting (SR) research has gained substantial momentum due to its consequential implications in social, economic, and political domains (Antonini et al. 2020; Cho and Giordano-Spring 2015; Joseph 2012). Originally based on environmental effects (Arunachalam et al. 2016; Birchall et al. 2015; Michelon and Rodrigue 2015), SR expanded rapidly to cover multiple areas. One such pioneering step in this regard is the triple bottom line (TBL), which advocates for the incorporation of planet, people, and profit as focal themes for achieving comprehensive and transparent reporting practices (Javed et al. 2021; Dumay et al. 2016).

Accordingly, scholars have profited from these three dimensions in their works conducted from many perspectives (O’Sullivan and O’Dwyer 2015; Solomon et al. 2011; Williams and Adams 2013). This review aims to offer a perspective on the aspects of sustainability reporting that have been addressed within a designated body of literature and elucidates the qualitative methodologies that have been harnessed to tackle these scholarly inquiries.

Sustainability reporting is driven by the interconnectedness of environmental, social, and economic factors. It encompasses preserving ecosystems, mitigating climate change, and responsible resource management. Social equity, economic stability, and global collaboration are integral aspects. Prioritizing human health, regulatory adherence, consumer preferences for sustainability, and a focus on long-term viability collectively define the ethos of sustainability, ensuring a resilient and thriving future. However, potential drawbacks include the risk of greenwashing, where organizations may provide misleading information, undermining the credibility of reporting (Hahn and Kühnen 2013). The lack of a universal standard can result in inconsistencies, hindering meaningful comparisons. Selective reporting, resource intensity, and limited stakeholder engagement also pose challenges. A short-term focus and the complexity of reporting may contribute to incomplete or confusing narratives. In essence, while sustainability reporting offers advantages, addressing issues such as greenwashing and improving standardization are crucial in order to maximize its effectiveness (Dunbar et al. 2021). Accordingly, sustainability reporting, despite enhancing transparency, brings inherent risks that can cause reputational damage, legal consequences, financial impacts, and stakeholder discontent. Operational challenges, inconsistency in reporting frameworks, and data security concerns further complicate the landscape. The complexity of reporting can overwhelm organizations, leading to errors (Gray 2006). Mitigating these risks requires careful consideration, adherence to standards, and a commitment to authenticity in reporting (Ioannou and Serafeim 2017). Therefore, while prior reviews have concentrated on diverse aspects such as sustainability performance, measurement, and theoretical frameworks (Chung and Cho 2018); drivers for SR adoption and the quality of reporting (Hahn and Kühnen 2013); different formats and determinants of SR (Dienes et al. 2016); the influence of management control on SR (Traxler et al. 2020); and the extent of integrated reporting (IR), this review distinguishes itself by adopting a unique approach. Rather than focusing exclusively on synthesizing various antecedents or a singular facet of SR, this review aims to investigate sustainability reporting’s key themes, aspects, theoretical foundations, and methodological choices. This epistemological emphasis facilitates the coherent formulation of research inquiries within a logical framework, thereby aiding researchers in comprehending the nature and scope of sustainability aspects and guiding their methodological decisions.

In recent years, the landscape of sustainability reporting has witnessed significant regulatory changes. Governments and international bodies have recognized the vital role of transparent reporting in achieving global sustainability goals. These changes include, for instance, the implementation of stricter environmental standards, mandates for corporate social responsibility disclosures, and an emphasis on ethical business practices. This study is motivated by the necessity of analyzing the impact of these regulatory shifts on the methodologies and focus of sustainability reporting research.

Despite the growing body of SR literature, there remain notable gaps that require attention. Prior reviews have concentrated on diverse aspects such as sustainability performance, measurement, and theoretical frameworks (Chung and Cho 2018). However, gaps persist in our understanding of the nuanced interactions between different dimensions of sustainability reporting, the effectiveness of emerging reporting formats, and the integration of sustainability into core business strategies. This study aims to address these gaps by adopting a holistic approach, synthesizing existing knowledge, and identifying avenues for further exploration. Moreover, emerging trends in sustainability reporting, such as the rise of integrated reporting (IR) and the increasing emphasis on social impact metrics, present new challenges and opportunities. This study is driven by a commitment to staying at the forefront of these trends, examining their implications for research methodologies, and contributing insights that can guide future practices.

Furthermore, the ever-expanding scope of sustainability reporting, from its roots in environmental concerns to encompassing diverse dimensions like social responsibility and economic viability, highlights the need for a comprehensive examination. The dynamic nature of sustainability reporting, coupled with recent regulatory changes, gaps in previous research, and emerging trends, underscores the importance of this study. By delving into these aspects, this research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the evolving landscape of sustainability reporting and its implications for academia, businesses, and policy makers and to explore not only what sustainability reporting includes but also why certain themes and aspects have gained prominence over time.

This review takes into consideration only qualitative empirical studies published in peer-reviewed journals. This selective boundary is motivated by several considerations. First, the field of SR is characterized by a plethora of qualitative research methodologies (Adams and Larrinaga-Gonzalez 2019; Parker and Northcott 2016). Secondly, the abundant information inherent in qualitative research incites researchers to use a diverse range of approaches for a deeper and broader comprehension of SR engagement (Parker et al. 2011). Lastly, qualitative research affords the capacity to delve into the processes, contextual differences, and complex dynamics (Parker 2008; Parker 2011). The nature of qualitative research provides an opportunity to closely scrutinize the impact of SR.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we outline the research. Then, we report our findings, covering the aspects of sustainability reporting in the literature, theories used in the literature, and methodologies employed. Tin the final sections of the paper, we delve into a comprehensive discussion of the review findings, provide a conclusion, and suggest avenues for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

The current review employed a systematic review approach to systematically detect, select, and evaluate the most pertinent studies aligned with the objectives of this review as suggested by many scholars in the field (Tranfield et al. 2003). Concerning the concept of sustainability, various terms, such as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting; corporate citizenship, corporate social responsibility (CSR); and social accounting, are often utilized interchangeably (Parker 2008; Gray 2014). Despite the assortment of terminologies in use, all these operational definitions fundamentally share the same essence: the communication of information about an organization’s environmental, economic, and social performance to a diverse array of stakeholders. Another relatively recent trend in reporting is integrated reporting (IR), wherein both financial and non-financial forms of information are presented in a unified format. The non-financial facet of IR is the primary focal point of sustainability research (Gleeson-White 2014).

The various terms used in the literature to define the diverse conceptualizations and applications of SR discussed above (CSR, social accounting, corporate citizenship, ESG reporting, integrated reporting, GRI, TBL, and sustainability) were incorporated into the search string used during the abstract keyword search. To broaden the search on sustainability reporting, the words reporting and disclosure were added to the other terms for possible combinations of terms including “corporate social responsibility”, “global reporting initiative”, “sustainable development”, “sustainability”, “triple bottom line”, “integrated”, “environmental”, “corporate citizenship”, “GRI”, “TBL”, “social accounting”, “IR”, “sustainable development”, “environment social governance”, and “ESG”. To narrow the area of the research, keywords such as “qualitative”, “exploratory study”, “explanatory study”, and “interpretive” were added to the search strings using the Boolean operator “and”, limiting the search only to qualitative research.

The search was conducted in April 2023 across four distinguished citation databases: Scopus, Business Source Complete, ProQuest Business, and Web of Science. The selection of these databases adheres to the precedent set by previous systematic reviews in the field (Adams and Larrinaga-Gonzalez 2019; Hinze and Sump 2019) and provided us with a coherent sample of articles. Furthermore, our research is delimited to articles published in the English language during the last two decades (2001–2022). This temporal constraint was imposed because publications with a sustainability focus during the early 2000s had limited and inconsequential impacts. In all databases, approximately 6% of the articles were published between 2001 and 2010. This trend aligns with the observations made by (Tranfield et al. 2003) in their examination of engagement research on corporate social responsibility (CSR). As noted by (Qian et al. 2021; Javed et al. 2021), the most substantial advancements in sustainability have occurred in the past two decades. Therefore, the exclusion of research published before 2001 is adequate to review the body of literature on sustainability reporting (SR).

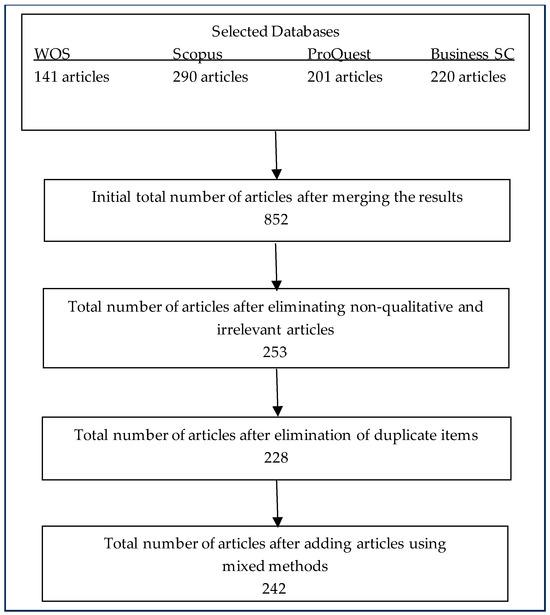

The consolidation of all articles in one list yielded a total of 852 articles. These articles underwent another elimination round to select the empirical studies, i.e., those grounded in experiences, real-life observations, phenomena, and empirical evidence. Consequently, articles categorized as reviews, prescriptive or descriptive pieces, commentary, or general discussions were determined to be non-empirical and excluded from the sample. Moreover, articles that did not primarily center on non-financial disclosures or sustainability were also excluded. Finally, duplicate papers in these four databases were eliminated, a total of 14 articles using mixed methods were added to the corpus for review, and the selection process resulted in a total of 242 articles for further review and investigation of theoretical frameworks and methodologies employed. Figure 1 shows the article selection process.

Figure 1.

Article selection process.

Accordingly, the aspects of sustainability reporting empirically explored in the selected literature, qualitative methodologies, and theoretical frameworks are the focus of this systematic review. By addressing these points, this review contributes substantive insights into the contemporary trends and diverse sustainability dimensions. Moreover, it offers guidance with respect to areas warranting further attention, benefiting practitioners and regulators by highlighting the domains where heightened practical and regulatory arrangements are needed (Dumay et al. 2016).

3. Descriptive Analysis

The systematic review procedure resulted in the identification of a total of 242 articles. These articles underwent a subsequent screening phase to elucidate their findings. Initially, all articles were classified based on the disciplinary focus of the journals in which they were published. These focus areas included sustainability, finance, accounting, economics, and management. Further analysis provided a descriptive overview of sustainability reporting publications according to journal focus.

Among the chosen articles, 33% (80) were published in journals that prioritize social and environmental accounting, such as “Sustainability”. Conversely, 32% (78) of the articles appeared in journals focused on accounting and related fields. This highlights the notable involvement of accounting scholars in advancing research on sustainability. Furthermore, other journals concentrating on business and management have also made substantial contributions to the development of sustainability research.

The descriptive analysis categorized the studies into two broad economic groups: developed and developing economies. This analysis revealed that 64% (155) of the studies were conducted with a focus on developed European economies. Conversely, a relatively smaller portion of empirical studies, totaling 31% (75), focused on emerging economies.

This focus on sustainability reporting in the research can be attributed to well-established and stringent regulatory frameworks in place in these countries. These regulations may mandate or encourage businesses to disclose information related to their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices. Moreover, developed economies generally have higher levels of awareness and adherence to corporate governance standards. As sustainability reporting is often linked to broader corporate governance practices, researchers may find more data and interest in this area within these economies.

Investors and stakeholders in developed and European economies exhibit a higher demand for sustainability-related information. This demand is driven by factors such as socially responsible investing, ethical consumerism, and pressure from advocacy groups.

Additionally, researchers may find it more feasible to conduct studies in developed economies due to better access to resources, data, and information. Developed nations typically have more established research institutions, databases, and networks that facilitate comprehensive studies on sustainability reporting. Researchers may prioritize studying these economies to understand and potentially shape global trends in sustainability reporting. Finally, developed and European economies have often been at the forefront of adopting sustainability reporting practices. The maturity of these practices provides a rich ground for researchers to analyze the evolution, effectiveness, and impact of sustainability reporting over time. While there is a predominant focus on developed and European economies, it is essential for future research to broaden its scope to include emerging markets and developing economies. This expansion would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the global landscape of sustainability reporting and address the need for inclusive and diverse perspectives.

3.1. Description of Aspects of Qualitative Sustainability Reporting

Sustainability has garnered substantial attention within organizations since the beginning of the millennium, driven by global recognition of the enduring impact of business activities on both current and future generations (Bebbington and Unerman 2018). Consequently, the United Nations introduced a comprehensive definition of sustainability, stating that any decision that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” qualifies as a sustainable decision or action. Since the publication of this report, the concept of sustainability has expanded to encompass social, environmental, and economic dimensions significantly influenced by human decisions. At the organizational level, Elkington (Elkington 2004) developed the triple bottom line (TBL) framework, which is grounded in seven drivers of sustainability progress. The TBL concept offers valuable guidance and principles for defining environmental, social, and economic responsibilities within organizations (Gimenez et al. 2012; Rambaud and Richard 2015). The TBL concept encompasses the social, environmental, and economic interactions of an organization (Gray 2014).

The triple bottom line (TBL) approach offers organizations a comprehensive and well-organized framework for the implementation, reporting, and disclosure of various sustainability practices. One notable development stemming from the TBL is the people, planet, and profit (3Ps) reporting framework. The widespread acceptance of the TBL is shown by its adoption as a reference model by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). Existing research literature supports the notion that the GRI is recognized as the most rigorous guideline for sustainability reporting (SR) (Boiral 2013) and has become the standard framework for SR (Bananuka et al. 2019; Bananuka et al. 2022; Petcharat and Zaman 2019). The GRI’s classification of broader sustainability dimensions into specific categories and subcategories has brought precision to the focus of academic research, enabling researchers to contribute to specific sustainability dimensions. Accordingly, the review shows that researchers followed the TBL approach and that the environment (planet) was the frame used in 25% (60) of the selected literature, with a general focus on climate change, carbon accounting, water management, and biodiversity. The social (people) frame was used in 17% (41) of the articles, with a focus on employees, employee reporting, and social disclosures. Finally, the economic (profit) frame was used in 10% (24) of the works, taking into consideration mostly the tax issues related to sustainability and CSR. Other works (48%) were based on multiple aspects of sustainability reporting.

3.2. Main Theoretical Frameworks in the Literature

A theoretical framework is the lens through which researchers view, explain, and comprehend reality (Anfara and Mertz 2014). It forms the foundation for a researcher’s methodological choices. Consequently, different theoretical perspectives exist to explain sustainability reporting (SR) as either an organizational change process or a stakeholder management process. The primary theoretical frameworks in the selected articles were legitimacy theory (LT), stakeholder theory (ST), and institutional theory (IT).

The following section depicts the three important theories used in the selected literature.

3.2.1. Stakeholder Theory

SR encompasses many groups, extending beyond just funding providers (Gray 2006). In the context of SR, stakeholders are “Entities, associations, and individuals that could be affected by the actions and decisions of the reporting organization. Stakeholders include employees, workers, suppliers, the community, activists, institutional investors, and civil society organizations” (Gray 2006).

The complexity and dynamism associated with the identification of diverse stakeholders deal with five distinct organization–stakeholder relationships in environmental reporting: demanding, promoting, committing, donating, and preventing (Gray 2006; Onkila et al. 2014). Stakeholder theory facilitates communication between organizations and stakeholders through four facets: descriptive, instrumental, normative, and managerial aspects.

3.2.2. Legitimacy Theory

This theory posits that an organization aligns its actions with socially desirable “norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Suchman 1995). Suchman (1995) affirmed that organizations seek legitimacy through pragmatic, moral, and cognitive rationales. This review synthesized the selected literature according to these three rationales. A considerable number of articles (36 articles, constituting 15%) employed LT as a foundational framework. Table 1 shows the main theories and related approaches in the literature.

Table 1.

Main theories and related approaches in the literature.

3.2.3. Institutional Theory

The escalating trend in sustainability reporting as a response to economic pressures is a subject of debate. Hahn and Kühnen (2013) showed mixed empirical findings regarding economic pressure as a determinant of SR. However, they also showed that social and cultural pressures may push organizations to adopt SR. Accordingly, organizations institutionalize specific sustainability norms, values, and beliefs in their operations. This institutionalization is often characterized by isomorphism, encompassing coercive, mimetic, and normative isomorphism, leading to a homogenization of organizational practices (DiMaggio and Powell 1983).

3.3. Methodological Approaches in Qualitative Sustainability Reporting Research

Researchers employ various qualitative research methods in their sustainability studies, often selecting the approach based on their specific research areas (Creswell and Poth 2017). Utilizing Suddaby and Greenwood’s (2008) methodological framework for examining institutional change, this review concentrates on three distinct techniques: interpretive, historical, and dialectical techniques. The multivariate methodology was excluded from consideration, as the review aimed to synthesize and identify gaps specifically in qualitative methodologies within SR research.

The interpretive approach involves a detailed examination of stakeholders’ perceptions and interpretations of institutional practices and structures (Suddaby and Greenwood 2008). It seeks to uncover how and why structural changes emerge. This approach employs content analysis, case studies, investigation of documents and websites, a semiotic lens, and interviews to shed light on the intention and progress of sustainability reporting, stakeholders’ perception, stakeholders’ framing, and SR’s performance and institutionalization. The articles using this methodology accounted for 75% (180) of the selected literature, and the leading articles using this methodological framework are (e.g., Boiral 2013; Gray 2014; Dillard and Pullman 2017; Tanima et al. 2020; Cuckston 2013; Tweedie and Martinov-Bennie 2015).

The historical approach considers institutions as outcomes of multiple phenomena influenced by many interacting causes (Brennan and Merkl-Davies 2014; Al Mahameed et al. 2020). This approach aims to determine various stages of change in organizations using historical data and phenomena to explain institutional and organizational arrangements. This approach is mainly based on document analysis and seeks historical evidence of tensions in current SR practices. Many scholars (e.g., Albu et al. 2020; Khan and Ali 2023; Khan 2014) used this methodology in the selected literature.

The dialectical approach adopts a critical perspective, assuming that organizations are formed by power relations in society (Al-Htaybat and von Alberti-Alhtaybat 2018). It delves into the influence of power dynamics on the formation and evolution of institutions. The articles in the sample using this approach deal with power and politics, carbon accounting, climate issues, and stakeholder management at times of crisis (e.g., Albu et al. 2020; Belal et al. 2015; Bowen and Wittneben 2011). They account for 15% (36) of the sample. Other works can be classified as using mixed methodologies.

4. Discussion

This study sought to offer an overview of the extent to which sustainability aspects are investigated within a chosen body of qualitative literature. The theoretical approaches used in sustainability research, the qualitative research methods utilized within the literature, and major aspects in this line of research were examined. In the following section, we examine the findings and their significance.

4.1. Sustainability Reporting Aspects

The review reveals that among the three dimensions of sustainability (environmental, social, and economic), the environmental dimension is the most extensively studied in the selected literature. Topics within the environmental dimension include climate change and carbon accounting (Boiral 2013), stakeholder influence in environmental standard setting, water accounting and management, and biodiversity governance and valuation (Gray 2006; Suddaby and Greenwood 2008). This heightened focus is likely a response to the increasing urgency to address environmental degradation and align business practices with sustainability goals. Conversely, the social and economic dimensions have received relatively less attention, although recent studies indicate a growing trend in these areas. For instance, social aspects explored in recent literature include community engagement in local environmental policy making, responsible investment decisions, social risk assessment related to the supply chain, and workplace community-focused CSR disclosure. Economic aspects include the institutionalization of ESG issues in investment decisions, sustainable product design, and the reconceptualization of multiple capitals (Ashraf and Uddin 2015; Ramya et al. 2020).

Additionally, the review shows that a significant portion of the literature (50%, 121) views sustainability reporting as a concept incorporating all three dimensions. Sustainability reporting is viewed as a multifaceted instrument for organizational management and communication, serving the dual purposes of stakeholder engagement and legitimization. This approach aligns with the evolving expectations of stakeholders who seek comprehensive insights into organizational sustainability practices. Sustainability reporting is not merely a disclosure tool but is increasingly recognized as a strategic instrument for organizational management and communication. The integration of ethical concerns further emphasizes the need for companies to showcase their commitment to responsible and ethical business practices (Jámbor and Zanócz 2023).

Recent studies, particularly those published after 2018, reveal a shift from an institutional perspective to a social–political paradigm. Contextualization, particularly in emerging economies, has become a prominent trend in SR research. This shift underscores SR’s global significance and the importance of fostering a shared understanding of the subject (Journeault et al. 2021). This shift indicates a broader recognition that sustainability reporting is not solely an institutional practice but is deeply embedded in societal and political contexts. Contextualization reflects a growing awareness of diverse global perspectives and the need for nuanced, culturally relevant approaches to sustainability.

However, certain areas remain underexplored in recent literature. Indigenous people’s rights, despite UN emphasis on this issue, have received limited attention, with only a single article shedding light on this topic (Prinsloo and Maroun 2020; Scandurra and Thomas 2023; Richard and Odendaal 2021). Moreover, there is a requirement for additional investigation in domains like employee health and safety measures, product responsibility, and gender dynamics. Addressing these gaps is crucial for a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of the social implications of sustainability reporting.

A deep dive into these findings highlights both the progress and the existing gaps in sustainability reporting research. Emphasizing the holistic nature of sustainability, understanding contextual influences, and addressing underexplored areas will contribute to a more robust and impactful sustainability reporting framework. Researchers and practitioners can use these insights to guide future studies, ensuring that sustainability reporting continues to evolve in tandem with global challenges and societal expectations.

4.2. Theories in Selected Literature

This review identified the prevalent theories used in exploring various aspects of sustainability reporting (SR). There are two major theories used in the selected works: stakeholder theory (ST) and legitimacy theory (LT), which are used as fundamental theories in qualitative SR research.

Approximately 33% (81) of the selected articles employed ST as a primary theoretical framework for their empirical investigations. ST is applied to elucidate how organizations perceive and interact with diverse stakeholder groups. The literature identifies a wide array of stakeholder groups, including social activists, employees, vulnerable societies, investors, suppliers, and indigenous people. For instance, Herremans and Nazari (2016), Belal et al. (2015), and Del Baldo (2017) raised questions about how world trade should embrace environmental responsibility, emphasizing the role of vulnerable societies. Khan and Ali (2023), Erin et al. (2022), and Esteban-Arrea and Garcia-Torea (2022) focused on information disclosure about employees’ rights. Finau et al. (2018) view stakeholder relationships as network peripherals, highlighting stakeholders’ efforts to gain power within organizations. The findings suggest that sustainability reporting is considered a tool for communicating sustainability practices to stakeholders, aligning with its instrumental aspect. The findings also acknowledge the complex and dynamic nature of organization–stakeholder interactions, resonating with sustainability reporting.

Legitimacy theory is widely used in the literature. Among studies using LT, the pragmatic aspect is most prevalent, accounting for 87%. The pragmatic perspective interprets actions taken by organizations to address immediate stakeholders. Fraser (2012) and Killian and O’Regan (2016) describe social accounting as a pragmatic legitimacy practice employed by organizations to rebuild relationships with their communities.

In summary, ST and LT are prominent theoretical frameworks employed in the selected literature to explore various facets and tensions of SR. ST emphasizes stakeholder interactions and relationships, while LT focuses on organizational efforts to maintain legitimacy through SR practices. These theories provide valuable insights, contributing to our understanding of how organizations perceive and respond to sustainability challenges and stakeholder expectations.

This review also uncovers the usage of various aspects of the major theories in the selected literature, shedding light on how the structures and practices of organizations change according to different pressures and influences. These aspects include moral legitimacy, institutional theory (IT), and other critical and interdisciplinary perspectives.

Moral legitimacy suggests that organizations undertake actions deemed ethically sound. Despite its alignment with the core purpose of sustainability reporting (SR), this facet has received limited attention in qualitative sustainability research. This review of existing literature underscores the significance of moral legitimacy as an underdeveloped dimension within the realm of sustainability reporting. Institutional theory, specifically coercive, mimetic, and normative pressures, plays a significant role in shaping organizational practices related to SR. Coercive pressures arise from regulatory sources, both formal and informal, and encompass internal and external factors of an organization. This review also shows that crises, whether instigated by human actions or natural events, can impose sustainability disclosure (Doni et al. 2019). Organizations also feel mimetic pressures. They tend to imitate benchmarked organizations’ SR practices to avoid risks associated with imposing extensive regulatory reporting requirements. There are also normative pressures that stem from professional bodies, especially accounting and auditing bodies (Cooper and Pearce 2011; Khan 2014; Haigh and Shapiro 2012). While less prevalent compared to coercive and mimetic pressures, normative pressures play a role in shaping organizational change related to SR, such as reporting frameworks, membership in sustainability rating bodies, and independent auditors (Dillard and Pullman 2017; Moerman and Laan 2015).

The review findings highlight the co-existence of these three forces of institutionalization, emphasizing their complex and multifaceted nature. Institutionalization is seen as a progressive and recursive process, with changes in practice and structure more than in underlying values and beliefs. Additionally, greenwashing practices, where companies may not genuinely adopt sustainability practices despite outward appearances, are also captured in the findings (Tarquinio and Xhindole 2022; Henriques et al. 2022; Cho 2020). Other important aspects of SR captured in the review include the impact of neoliberal economic ideologies (Albertini 2019; Abernathy et al. 2017) and socio-political factors (Tanima et al. 2020; Leong and Hazelton 2017) on sustainability reporting. The role of regulatory theory (Biondi et al. 2020) in shaping sustainability reporting practices and diffusion theory (Stefanescua et al. 2016) is to examine how SR practices spread and diffuse across organizations and regions (Siddiqui 2013).

The emerging use of mainstream accounting theories such as signaling theory (Alotaibi and Hussainey 2016) and agency theory (Stefanescua et al. 2016; Jensen and Meckling 1976) in the context of sustainability reporting is also noted. The diversity of theoretical frameworks reflects the complex nature of sustainability reporting and the interdisciplinary nature of research in this field.

4.3. Qualitative Methods Used in the Selected Literature

Concerning the qualitative methodologies used in the selected literature, the results show that a significant majority of the selected articles (78%) utilized interpretive analysis research methodologies such as case analysis (Cuckston 2013; Egan 2014; Qian et al. 2011), content analysis (Aribi and Gao 2010; Fonseca 2010; García-Sánchez and Araújo-Bernardo 2020), discourse analysis (Higgins and Coffey 2016; Higgins and Walker 2012; Jaworska 2018), and historical analysis (Albu et al. 2020; Khan 2014).

Among these methodologies, case studies provide rich insights into how and why SR practices change (Traxler et al. 2020). They offer a detailed examination of specific instances of SR in practice. Content analysis uses textual data, such as reports and documents, to extract meaning and patterns related to SR.

Only a small percentage of studies (1%) used historical analysis and archival data as their qualitative methodology. This method involves examining historical records and archival data to understand the history and evolution of SR practices. While less common, a few studies employed netnography, a methodology that uses Internet sources and online communities to capture information and debates related to SR (Jeacle 2021; Unerman and Bennett 2004).

A significant portion of the selected studies (17%) employed discourse analysis to explore how power, politics, and conflicts among powerful actors influence organizational change, examining the language and communication surrounding SR (Tregidga 2013; Lodhia and Jacobs 2013) and shedding light on the discursive aspects of sustainability reporting.

The findings of this review indicate that the authors of numerous studies regarded shifts in organizational sustainability as a manifestation of power struggles and conflict management. Semi-structured interviews were frequently employed to unveil the existence of these power dynamics, politics, and conflicts between various stakeholders within organizations (Biondi et al. 2020; Morrison and Lowe 2021; Cook and Geldenhuys 2018). Additionally, the review revealed that the presence of these dynamics at every level in an organization can shape SR practices. This review also identified an emerging trend according to which sustainability researchers are increasingly adopting a critical theory paradigm. Critical theories are used to problematize social issues arising from SR practices and to advocate for more equitable and meaningful reporting. Critical theory is a philosophical and sociological approach to studying society, culture, and various social phenomena. It emerged as a response to traditional modes of social inquiry and seeks to critique and transform social structures and systems of power. Critical theory has influenced various fields, including sociology, political science, cultural studies, and education, contributing to ongoing discussions about social justice and societal change.

5. Implications and Conclusions

In this review, first, the choice of databases aligns with the precedent set by previous systematic reviews. The aim of this selection was to provide a coherent sample of articles, enhancing the robustness and comprehensiveness of the review. Secondly, the emphasis on developed European economies is justified by their well-established regulatory frameworks and higher levels of awareness regarding corporate governance standards. Third, the inclusion of various theoretical frameworks reflects the multifaceted nature of sustainability reporting. Accordingly, the acknowledgment of emerging theories, such as critical theory, demonstrates a commitment to exploring diverse perspectives to understand sustainability reporting practices.

The review findings have both theoretical and methodological implications for future research in the field of SR. According to the review findings, it can be argued that there is a need for more empirical research to explain the nature of changes in sustainability reporting practices in today’s organizations. This emphasis on empirical studies ensures that the findings are grounded in real-life observations and experiences, enhancing the reliability and applicability of the insights. It also necessitates additional investigation into the descriptive dimension of stakeholder theory, with a focus on highlighting the role of organizations as collaborative partners in their interactions with stakeholders (e.g., Jaworska 2018; Tweedie and Martinov-Bennie 2015). ST and LT are prominent theoretical frameworks employed in the selected literature to explore various facets and tensions of SR. ST emphasizes stakeholder interactions and relationships, while LT focuses on organizational efforts to maintain legitimacy through SR practices. These theories provide valuable insights, contributing to our understanding of how organizations perceive and respond to sustainability challenges and stakeholder expectations. ST provides a comprehensive and flexible framework for researchers to examine the complex interplay between organizations and their broader social, economic, and environmental contexts. It fosters a more inclusive and socially responsible approach to management and decision making. Legitimacy theory is a valuable lens for researchers interested in the dynamics of organizational legitimacy, how organizations respond to societal expectations, and the implications of perceived legitimacy for organizational success and sustainability. Accordingly, these two theories are dominant in SR research. The emerging trend of the use of critical theory is also an important result of this review. This diversity encourages researchers to approach the topic from different perspectives, fostering a more holistic understanding.

The results of this review emphasize the crucial need for a diversified approach, encompassing both methodological and theoretical perspectives, to advance sustainability reporting (SR). The findings highlight the potential applicability of organizational change theories in unexplored dimensions, contributing to the evolving landscape of SR research. Overall, the conclusion advocates for innovative approaches, gap exploration, and an interdisciplinary perspective to capture the diverse and profound impacts of sustainability reporting. It should also be added that sustainability reporting is generally considered a positive practice, offering transparency and accountability by providing stakeholders with insights into a company’s environmental, social, and economic performance. It fosters informed decision making among stakeholders, encouraging support for socially and environmentally responsible businesses. Additionally, sustainability reporting signals a commitment to corporate responsibility, motivating organizations to adopt more sustainable practices. However, its effectiveness depends on factors such as the sincerity of reporting, stakeholder understanding, and the commitment of organizations to genuine sustainability initiatives. Challenges include the risk of “greenwashing”, where reported information may be misleading; the potential complexity of reporting requirements for smaller businesses; and the trade-off between reporting efforts and actual sustainability actions. Despite these considerations, when approached with integrity and a genuine commitment to sustainability, reporting can be a valuable tool for fostering transparency, accountability, and responsible business practices.

In conclusion, this review provides a comprehensive overview of the aspects, theories, and methodologies used in qualitative research on sustainability reporting. It identifies gaps and opportunities for future research to advance knowledge in the field of SR, emphasizing the need for interdisciplinary and critical perspectives to understand the multifaceted nature of sustainability reporting practices.

This review offers actionable insights for diverse stakeholders. Policymakers can leverage the findings to shape policies aligned with evolving industry practices, while companies can enhance their sustainability reporting based on practical implications and emerging trends identified in the research. Moreover, collaboration across disciplines is encouraged to promote a holistic understanding of sustainability reporting. Advocacy groups and investors can use this research to advocate for ethical reporting standards. Given the emphasis on ethical concerns in sustainability reporting, regulatory frameworks could consider incorporating specific guidelines or standards that address ethical dimensions. Additionally, organizations and policy makers can engage with global initiatives like the Global Reporting Initiative for consistent and recognized sustainability reporting practices. This review highlights that the environmental dimension is the most extensively studied in sustainability reporting. Regulatory bodies could encourage a more balanced approach by placing greater emphasis on the social and economic dimensions. Moreover, regulatory frameworks could encourage research in underexplored areas in sustainability reporting, such as indigenous people’s rights and specific domains like employee health and safety measures, possibly by including specific indicators or disclosure requirements related to these aspects. This review also highlights the growing importance of SR in various disciplines and encourages further interdisciplinary exploration of its impacts. The exploration of unconventional applications of organizational change, like institutional logic and deinstitutionalization, opens new paths for future research. This review suggests the need for more qualitative research that explores the ethical aspects of SR, with moral legitimacy as a potential theoretical framework.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Projects Commission of Galatasaray University under grant number # FBA-2021-1056.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abernathy, John L., Michael Barnes, Chad Stefaniak, and Alexandria Weisbarth. 2017. An international perspective on audit report lag: A synthesis of the literature and opportunities for future research. International Journal of Audit 21: 100–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, Carol A., and Carlos Larrinaga-Gonzalez. 2019. Progress: Engaging with organisations in pursuit of improved sustainability accounting and performance. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 32: 2367–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mahameed, Muhammad, Ataur Belal, Florian Gebreiter, and Alan Lowe. 2020. Social accounting in the context of profound political, social and economic crisis: The case of the Arab spring. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 34: 1080–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, Elisabeth. 2019. Integrated reporting: An exploratory study of French companies. Journal of Management and Governance 23: 513–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, Nadia, Cătălin N. Albu, Oana Apostol, and Charles H. Cho. 2020. The past is never dead: The role of imprints in shaping social and environmental reporting in a post-communist context. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 34: 1109–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Htaybat, Khaldoon, and Larissa von Alberti-Alhtaybat. 2018. Integrated thinking leading to integrated reporting: Case study insights from a global player. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 31: 1435–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, Khaleed O., and Khaled Hussainey. 2016. Determinants of CSR disclosure quantity and quality: Evidence from non-financial listed firms in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 13: 364–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfara, Vincet A., and Norma Mertz. 2014. Theoretical Frameworks in Qualitative Research, 2nd ed. London and Thousands of Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Antonini, Carla, Cornelia Beck, and Carlos Larrinaga. 2020. Subpolitics and sustainability reporting boundaries. The case of working conditions in global supply chains. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 33: 1535–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aribi, Zakaria A., and Simon Gao. 2010. Corporate social responsibility disclosure: A comparison between islamic and conventional financial institutions. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 8: 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, Murugesh, Jagdeep Singh-Ladhar, and Andrea McLachlan. 2016. Advancing environmental sustainability via deliberative democracy: Analysis of planning and policy processes for the protection of lake Taupo. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 7: 402–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, Junaid, and Shahzad Uddin. 2015. Management accounting research and structuration theory: A critical realist critique. Journal of Critical Realism 14: 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bananuka, Juma, Stephen Korutaro Nkundabanyanga, Twaha Kigongo Kaawaase, Rachel K. Mindra, and Isaac N. Kayongo. 2022. Sustainability performance disclosures: The impact of gender diversity and intellectual capital on GRI standards compliance in Uganda. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 12: 840–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bananuka, Juma, Zainabu Tumwebaze, and Laura Orobia. 2019. The adoption of integrated reporting: A developing country perspective. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 17: 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, Jan, and Jeffrey Unerman. 2018. Achieving the united nations sustainable development goals: An enabling role for accounting research. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 31: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, Ataur R., Stuart M. Cooper, and Niaz A. Khan. 2015. Corporate environmental responsibility and accountability: What chance in vulnerable Bangladesh? Critical Perspectives on Accounting 33: 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, Lucia, John Dumay, and David Monciardini. 2020. Using the international integrated reporting framework to comply with EU directive 2014/95/EU: Can we afford another reporting facade? Meditari Accounting Research 28: 889–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchall, S. Jeff, Maya Murphy, and Markus J. Milne. 2015. Evolution of the New Zealand voluntary carbon market: An analysis of CarbonZero client disclosures. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 35: 142–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, Olivier. 2013. Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of a and aþ GRI reports. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 26: 1036–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, Frances, and Bettina Wittneben. 2011. Carbon accounting: Negotiating accuracy, consistency and certainty across organisational fields. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 24: 1022–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, Niamh M., and Doris M. Merkl-Davies. 2014. Rhetoric and argument in social and environmental reporting: The dirty laundry case. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 27: 602–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, Garry D. 2012. The special issue: AAAJ and research innovation. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 25: 216–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Charles H. 2020. CSR accounting ‘new wave’ researchers: ‘step up to the plate’... or ‘stay out of the game. Journal of Accounting and Management Information Systems 19: 626–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Charles H., and Sophie Giordano-Spring. 2015. Critical perspectives on social and environmental accounting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 33: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Jieun, and Charles H. Cho. 2018. Current trends within social and environmental accounting research: A literature review. Accounting Perspectives 17: 207–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Greta, and Dirk J. Geldenhuys. 2018. The experiences of employees participating in organisational corporate social responsibility initiatives. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology 44: 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Stuart, and Graham Pearce. 2011. Climate change performance measurement, control and accountability in English local authority areas. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 24: 1097–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2017. Qualitative Inquiries and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed. London and Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cuckston, Thomas. 2013. Bringing tropical forest biodiversity conservation into financial accounting calculation. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 26: 688–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Baldo, Mara. 2017. The implementation of integrating reporting in SMEs. Meditari Accountancy Research 25: 505–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienes, Dominik, Remmer Sassen, and Jasmin Fischer. 2016. What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 7: 154–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, Jesse, and Madeleine Pullman. 2017. Cattle, land, people, and accountability systems: The makings of a values-based organisation. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 37: 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, Paul J., and Walter W. Powell. 1983. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review 48: 147–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doni, Federica, Mikkel Larsen, Silvio B. Martini, and Antonio Corvino. 2019. Exploring integrated reporting in the banking industry: The multiple capitals approach. Journal of Intellectual Capital 20: 165–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, John, Cristiana Bernardi, James Guthrie, and Paola Demartini. 2016. Integrated reporting: A structured literature review. Accounting Forum 40: 166–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, Craig G., Zhichuan Frank Li, and Yaqi Shi. 2021. Corporate Social (Ir)responsibility and Firm Risk: The Role of Corporate Governance. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3791594 (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Egan, Matthew. 2014. Making water count: Water accountability change within an Australian university. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 27: 259–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, John. 2004. Enter the Triple Bottom Line, the Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up? 1st ed. London: Routledge, p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Erin, Olayinka A., Omololu A. Bamigboye, and Babajide Oyewo. 2022. Sustainable development goals (SDG) reporting: An analysis of disclosure. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies 12: 761–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Arrea, Rosa, and Nicolas Garcia-Torea. 2022. Strategic responses to sustainability reporting regulation and multiple stakeholder demands: An analysis of the Spanish EU non-financial reporting directive transposition. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 13: 232–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finau, Glen, John Cox, Jope Tarai, Romitesh Kant, Renata Varea, and Jason Titifanue. 2018. Social media and disaster communication: A case study of cyclone Winston. Pacific Journalism Review: Te Koakoa 24: 123–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, Alberto. 2010. How credible are mining corporations’ sustainability reports? A critical analysis of external assurance under the requirements of the international council on mining and metals. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 17: 355–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Michael. 2012. Fleshing out’ an engagement with a social accounting technology. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 25: 508–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, Isabel-María, and Cristina-Andrea Araújo-Bernardo. 2020. What colour is the corporate social responsibility report? Structural visual rhetoric, impression management strategies, and stakeholder engagement. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27: 1117–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, Cristina, Vicenta Sierra, and Juan Rodon. 2012. Sustainable operations: Their impact on the triple bottom line. International Journal of Production Economics 140: 149–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson-White, Jane. 2014. Six Capitals: The Revolution Has to Have—Or Can Accountants Save the Planet? Sydney: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Rob. 2006. Social, environmental and sustainability reporting and organisational value creation? Whose value? Whose creation? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 19: 793–819. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Rob. 2014. Ambidexterity, puzzlement, confusion and a community of faith? A response to my friends. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 34: 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, Rüdiger, and Michael Kühnen. 2013. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. Journal of Cleaner Production 59: 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, Matthew, and Matthew A. Shapiro. 2012. Carbon reporting: Does it matter? Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 25: 105–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, Rita, Cristina Gaio, and Marisa Costa. 2022. Sustainability Reporting Quality and Stakeholder Engagement Assessment: The Case of the Paper Sector at the Iberian Level. Sustainability 14: 14404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, Irene M., and Jamal A. Nazari. 2016. Sustainability reporting driving forces and management control systems. Journal of Management Accounting Research 28: 103–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Colin, and Brian Coffey. 2016. Improving how sustainability reports drive change: A critical discourse analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production 136: 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Colin, and Robyn Walker. 2012. Ethos, logos, pathos: Strategies of persuasion in social/environmental reports. Accounting Forum 36: 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinze, Anne-Kathrin, and Franziska Sump. 2019. Corporate social responsibility and financial analysts: A review of the literature. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 10: 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, Christopher, and Yves Gendron. 2015. What is going on? The sustainability of accounting academia. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 26: 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, Ioannis, and George Serafeim. 2017. The Consequences of Mandatory Corporate Sustainability Reporting. Harvard Business School Research Working Paper No. 11–100. Boston: Harvard Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Jámbor, Attila, and Anett Zanócz. 2023. The Diversity of Environmental, Social, and Governance Aspects in Sustainability: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 15: 13958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, Hassnain, Saba F. Firdousi, Majid Murad, Wang Jiatong, and Muhammad Abrar. 2021. Exploring disposition decision for sustainable reverse logistics in the era of a circular economy: Applying the triple bottom line approach in the manufacturing industry. International Journal of Supply and Operations Management 8: 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworska, Sylvia. 2018. Change but no climate change: Discourses of climate change in corporate social responsibility reporting in the oil industry. International Journal of Business Communication 55: 194–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeacle, Ingrid. 2021. Navigating netnography: A guide for the accounting researcher. Financial Accountability and Management 37: 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Michael, and William Meckling. 1976. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, George. 2012. Ambiguous but tethered: An accounting basis for sustainability reporting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 23: 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journeault, Marc, Yves Levant, and Claire-France Picard. 2021. Sustainability performance reporting: A technocratic shadowing and silencing. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 74: 102145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Nurul J. M., and Hasani Mohd Ali. 2023. Regulations on Non-Financial Disclosure in Corporate Reporting: A Thematic Review. Sustainability 15: 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Tehmina. 2014. Kalimantan’s biodiversity: Developing accounting models to prevent its economic destruction. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 27: 150–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killian, Sheila, and Philip O’Regan. 2016. Social accounting and the co-creation of corporate legitimacy. Accounting, Organizations and Society 50: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Shane, and James Hazelton. 2017. Improving corporate political donations disclosure: Lessons from Australia. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 37: 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhia, Sumit, and Kerry Jacobs. 2013. The practice turn in environmental reporting. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 26: 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, Giovanna, and Michelle Rodrigue. 2015. Demand for CSR: Insights from shareholder proposals. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 35: 157–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerman, Lee, and Sandra Laan. 2015. Exploring shadow accountability: The case of James Hardie and Asbestos. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 35: 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Leanne J., and Alan Lowe. 2021. Into the woods of corporate fairytales and environmental reporting. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 34: 819–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, Niamh, and Brendan O’Dwyer. 2015. The structuration of issue-based fields: Social accountability, social movements and the equator principles issue-based field. Accounting, Organizations and Society 4: 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onkila, Tiina, Kristiina Joensuu, and Marileena Koskela. 2014. Implications of managerial framing of stakeholders in environmental reports. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 34: 134–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Lee D. 2008. Interpreting interpretive accounting research. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 19: 909–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Lee D. 2011. Building bridges to the future: Mapping the territory for developing social and environmental accountability. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 31: 787–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Lee D., and Deryl Northcott. 2016. Qualitative generalising in accounting research: Concepts and strategies. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 29: 1100–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Lee D., James Guthrie, and Simon Linacre. 2011. The relationship between academic accounting research and professional practice. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 24: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcharat, Neungruthai, and Mahbub Zaman. 2019. Sustainability reporting and integrated reporting perspectives of Thai-listed companies. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting 17: 671–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsloo, Andre, and Warren Maroun. 2020. An exploratory study on the components and quality of combined assurance in an integrated or a sustainability reporting setting. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 12: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Wei, Carol Tilt, and Ataur Belal. 2021. Social and environmental accounting in developing countries: Contextual challenges and insights. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 5: 1021–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Wei, Roger Burritt, and Gary Monroe. 2011. Environmental management accounting in local government: A case of waste management. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 24: 93–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaud, Alexandre, and Jacques Richard. 2015. The ‘triple depreciation line’ instead of the ‘triple bottom line’: Towards a genuine integrated reporting. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 33: 92–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, S.M., Aysha Shereen, and Rupashree Baral. 2020. Corporate environmental communication: A closer look at the initiatives from leading manufacturing and IT organizations in India. Social Responsibility Journal 16: 843–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, Genevé, and Elza Odendaal. 2021. Credibility-enhancing mechanisms, other than external assurance, in integrated reporting. Journal of Management and Governance 25: 61–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, Giuseppe, and Antonio Thomas. 2023. The SDGs and Non-Financial Disclosures of Energy Companies: The Italian Experience. Sustainability 15: 12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Javed. 2013. Mainstreaming biodiversity accounting: Potential implications for a developing economy. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 26: 779–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Jill F., Aris Solomon, Simon D. Norton, and Nathan L. Joseph. 2011. Private climate change reporting: An emerging discourse of risk and opportunity? Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 24: 1119–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanescua, Cristina A., Tudor Oprisor, and Mara A. Sntejudeanua. 2016. An original assessment tool for transparency in the public sector based on the integrated reporting approach. Accounting and Management Information Systems 15: 542–64. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, Marc C. 1995. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review 20: 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, Roy, and Royston Greenwood. 2008. Methodological Issues in Researching Institutional Change. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Research Methods. Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 176–95. [Google Scholar]

- Tanima, Farzana A., Judy Brown, and Jesse Dillard. 2020. Surfacing the political: Women’s empowerment, microfinance, critical dialogic accounting and accountability. Accounting, Organizations and Society 85: 101–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarquinio, Lara, and Chiara Xhindole. 2022. The institutionalisation of sustainability reporting in management practice: Evidence through action research. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 13: 362–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, David, David Denyer, and Palminder Smart. 2003. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management 14: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, Albert A., Daniela Schrack, and Dorothea Greiling. 2020. Sustainability reporting and management control–a systematic exploratory literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 276: 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregidga, Helen. 2013. Biodiversity offsetting: Problematisation of an emerging governance regime. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 26: 806–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweedie, Dale, and Nonna Martinov-Bennie. 2015. Entitlements and time: Integrated reporting’s double-edged agenda. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 35: 49–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unerman, Jeffrey, and Marc Bennett. 2004. Increased stakeholder dialogue and the internet: Towards greater corporate accountability or reinforcing capitalist hegemony? Accounting, Organizations and Society 29: 685–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Sarah J., and Carol A. Adams. 2013. Moral accounting? Employee disclosures from a stakeholder accountability perspective. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 26: 449–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).