Abstract

Based on a qualitative single case study with eight interviews, this study lays the foundation for literature on the motivation for transforming from a quasi-governmental entity to a social business. The context of this case study is a spin off of business schools from the French chambers of commerce and industry. This spin off was encouraged by enabling legislation that allowed assets specific to business schools to be transferred without taxes and fees if they adopted this legal business form. This case study is on the Burgundy School of Business, one of the seven schools that have adopted the regime. The school is also a member of the Principles of Responsible Management in Education. This case study suggests that the motivation for adopting a social business form could be institutional rather than personal. International rankings influence country legislation and business form adoption in a competitive industry. This case also discusses why the school has intentionally decided not to go for a digital transformation of its core business model. This case leads to theoretical propositions that consider the conditions under which public sector enterprises may spin off units as social businesses focused on their beneficiaries, and the control mechanisms that need to be instituted by the parent enterprise.

Keywords:

institutional studies; qualitative research; social business; organizational change; governance; business education; business strategy; motivation; responsible management education JEL:

G34; I23; L3; P3; P46

1. Introduction

Why do enterprises adopt hybrid social business models? A social business model encourages firms to follow a for-profit, no-dividend model that considers social objectives to be necessary. Extant research in entrepreneurship creation literature has indicated personal motivations linked to the founder: the need for creativity, problem-solving, and compassion. However, these authors were looking at enterprises created ab initio. A smaller group of authors have looked at why larger non-profit organizations transform to for-profit, but remain committed to a hybrid model. In this case, the motivation is financial sustainability and the desire for growth.

There is scant literature on for-profits or government enterprises transforming into not-for-profits. Although many researchers are interested in corporate transformations, the present study is the first that studies why a division of a chamber of commerce and industry (CCI) would spin off to become a social business. It focuses on the contextual factors in the international environment of French business schools, notably the risk of not surviving, that led to action at a national level for a change in regulation that enabled the creation of a specific business form. This study’s objective is to add to the theories of motivation for transforming into social businesses, and the governance and control mechanisms that may be necessary. Our research question is: “what are the theoretical and policy lessons that emerge from a public sector enterprise converting into a private social business?”. First, this research question is important in an era where many developed countries have become too centralized and need to make more room for private initiatives (Furceri and Sousa 2011). Moreover, it is often difficult for policymakers to privatize, since the media raises the question of transferring hidden resources or imposing hidden costs (Jarvis 2008; Morel et al. 2019). However, if the transformed enterprise is a social business in conformity with public goals and the transfer of profits is controlled, such cases may expand in the near future. Second, at a time when global leaders are investing in sustainable development and responsible management (Klettner et al. 2014; Muff et al. 2020), this study points out the role that international competition, international accreditations, and journalistic rankings may have on legislation and corporate strategy. Third, there is a considerable academic and practical interest in social entrepreneurship that creates positive social change (Saebi et al. 2019; Stephan et al. 2016), especially through education. While social entrepreneurship researchers focus on new enterprises (Tišma et al. 2022), positive social change can also be created by existing enterprises that are transformed into social enterprises.

2. Literature Review of Motivation to Create Social Businesses

2.1. Social Entrepreneurship, Social Enterprise, and Social Business

There are many overlapping words in the literature of social entrepreneurship, social enterprise, and social business. In a very broad sense, we can say that social entrepreneurship literature deals with creating new social enterprises. In contrast, social enterprise literature is more focused on the governance and management of these firms. Social business is a term that could be understood as a synonym for a social enterprise, or as a specific form of social enterprise (Baker 2016). Examples of social corporate business forms include Benefit Corporations (O’Toole 2019; Rawhouser et al. 2015) and Community Interest Companies (Ko et al. 2018; Mason 2020; Nicholls 2010). In addition, the specific social business forms advocated by Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus include either an enterprise owned by poor beneficiaries who then get dividends (model 2), or an enterprise owned by diverse shareholders but which cannot give dividends and which has to commit to a social objective (model 1) (Yunus and Weber 2007, 2010). These models have their limits: for example, model 2 does not indicate who would own the enterprise once the problem is solved; and model 1 does not really limit shareholders from selling their shares at book value, and thus, dividends are only differed (Ashta 2009). We can add that a for-profit enterprise that does not distribute dividends needs to grow perpetually or must find ways to allocate the surplus to its managers, employees, or other stakeholders. However, Yunus’ most recent work has insisted on a zero dividend, even at the time of exit, by selling the shares at par value (See Box 1). In any case, the models advocated by Yunus have proliferated, as have the others.

Box 1. The Seven Principles of Social Business.

Last Updated: 10 June 2015

- Business objective will be to overcome poverty, or one or more problems (such as education, health, technology access, and environment) which threaten people and society; not profit maximization

- Financial and economic sustainability

- Investors get back their investment amount only. No dividend is given beyond investment money

- When investment amount is paid back, company profit stays with the company for expansion and improvement

- Gender sensitive and environmentally conscious

- Workforce gets market wage with better working conditions

- …Do it with joy

Source: https://socialbusinesspedia.com/, accessed on 10 June 2021

There is a large body of literature on the differences between not-for-profits, hybrid social enterprises, and for-profits. Ashta (2018) indicates that the vision of not-for-profit social enterprises focuses on society, while the vision of commercial enterprises focuses on their organizational goals. However, for-profit social enterprises are stuck in-between, and their vision and mission statements tend to be long, and confused as to how to explain how their goal is to both do good and yet perform well. Vision is important because it provides purpose to an organization (Hill and Levenhagen 1995) and influences its strategy and performance (Engelen et al. 2015). Visionary leaders can foresee the future intuitively through magical thinking (Young et al. 2013).

2.2. The Motivation of Social Entrepreneurs

Many researchers have studied the motivation of social entrepreneurs. Table 1 summarizes some of the main motivations found in existing literature and contains a few academic citations for these. Some of the motivations are pro-social, and others are entrepreneurial motivations. However, pro-social motivations are not enough for someone to form a social enterprise rather than a charity; they must be coupled with a desire for autonomy and long-term financial sustainability. Conversely, a passion for independence and financial sustainability is unlikely to lead to the creation of a social enterprise without some pro-social motivational factors. Even in social enterprises, such as cooperatives, where the pro-social motivation of the founding entrepreneurs may be dominant, there are still motivations related to instrumentality and ideology (Sinapi and Juno-Delgado 2015).

Table 1.

Motivations of social entrepreneurs.

2.3. Motivation to Transform to For-Profit

Many social enterprises in the microfinance sector started as not-for-profits and later converted to for-profits (Campion and White 2001). In some of these cases, an NGO controlled the for-profit, but the assets were transferred. According to the realistic theory of the life cycle of social enterprises, once a not-for-profit shows that it can earn money and be independent of stakeholders’ charity, it has incentives to convert to a for-profit legal status. This transformation is essential for competing with other firms entering the market directly as for-profits (Ashta 2020).

However, there are legacy problems from stakeholder’s expectations of a not-for-profit that converts to a for-profit. These problems emerged in the critiques of Compartamos in Mexico and SKS in India at the time of their Initial Public Offering (Kleynjans and Hudon 2016). However, firms can overcome such criticisms with symbolic or substantive responses (Nason et al. 2018).

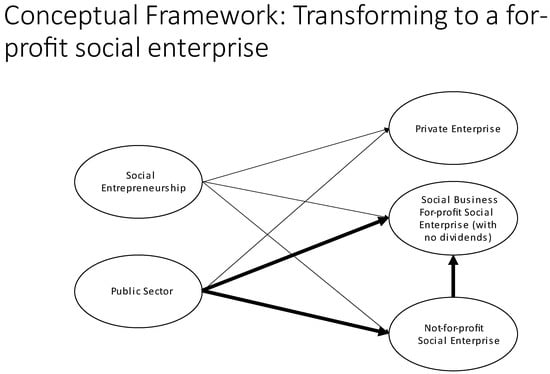

Successful social entrepreneurs often engage in institutional work (Mair et al. 2012; Marti and Mair 2009). This institutional work is needed to prepare the stakeholders to transform social enterprises from a purely social orientation to a hybrid one. While the transformation of NGOs to for-profits has been researched, there is no research on the transfer of enterprises in the public sector to not-for-profits or for-profit social businesses. This is clarified by the framework presented in Figure 1. In this simplified framework, we see two possible starting states. The first is that of a social entrepreneurship that becomes either a not-for-profit, a for-profit, or a social business (for profit, but without dividends). However, these end-states can also come from the transformation of a public sector enterprise. For example, the conversion of a public sector enterprise to a for-profit enterprise would be deemed privatization.

Figure 1.

Distinguishing our focus from other cases.

Although there is vast literature on the privatization of public sector firms (Starr 1988), it usually assumes that the privatized firm would be for-profit (Vickers and Yarrow 1991).

A systematic literature review recognized six reasons for the privatization of education: (a) privatization as a deeply ideological and structural state reform; (b) scaling up privatization through school choice reforms; (c) privatization in social democratic welfare states; (d) historical public-private partnerships in education systems with a tradition of religious schooling; (e) privatization through the emergence and expansion of low-fee private schools in low-income countries and (f) privatization through catastrophe (Verger et al. 2017).

However, none of the reasons referenced above cover the privatization towards social businesses or not-for-profit enterprises, marked by bold arrows in Figure 1. This triangle is the zone of our study. What lessons can we gain from such a conversion that may be important to future state enterprises wishing to become social enterprises? How do these motivations, often captured in mission and vision statements, differ from those of other transformations?

3. Methods

3.1. Research Methodology

Since this research on the transformation of a state enterprise to a social business form is exploratory and the first in this area, a case study design is appropriate. This case study represents qualitative research, which uses non-quantitative data and is inductive and interpretative. As opposed to typical quantitative research, qualitative case studies do not start with hypotheses; rather, they draw out abstract propositions which could provide insights into complex, new, or understudied phenomena. Even single case-based research is helpful if it provides variance from existing theory and leads to new propositions for future researchers. Process-based studies can help researchers understand the change from one state to another (Bansal et al. 2018). As mentioned in the above literature review, there is no study of the motivation for transformation from government bodies to not-for-profits. Therefore, examining such a process is justified.

The case selected is that of Consular Higher Education Institutions (hereafter, the French acronym EESC will be used to denote établissements d’enseignement supérieure consulaire). Although consular institutions are not, strictly speaking, state institutions, they are not private institutions. Consular institutions are run by the Chambers of Commerce and Industry (CCI); these are answerable to the ministry of finance and economy and can be considered quasi-State institutions.

A particular form of social enterprise was created by legislation to facilitate the transformation of institutions from a consular status to a social business, and the code of commerce was altered accordingly (see Box 1). Model 1 of the Yunus social business is the one that interests us here, because the law created a social enterprise with the features included in Box 2. As shown, EESCs are governed by private laws applicable to public limited companies. Their mission is limited to purposes agreed by convention with the CCI, and they cannot give dividends.

Box 2. Amendment by LAW No. 2014–1545 of 20 December 2014.

- Article L711-17 of the Code of Commerce (selected alineas)

- Consular higher education institutions are legal persons governed by private law governed by the legislative provisions applicable to public limited companies, in so far as they are not contrary to the specific provisions governing them.

- Subject to Article consular higher education institutions are authorized to exercise in France and abroad, subject to the agreement of the governments concerned, themselves and through subsidiaries or participations, all activities that relate, directly or indirectly, to their missions and activities, defined by the convention mentioned in Article L. 711-19 of this Code, as well as any other activity provided for by their statutes.

- Where a consular higher education institution has made a distributable profit, within the meaning of the first paragraph of Article L. 232-11, it is allocated to the constitution of reserves.

More specifically, among thirty major business schools, seven business schools have chosen the new statute of EESCs. Of these, the Burgundy School of Business (BSB) first chose a not-for-profit form (see the bold bottom arrow in Figure 1) and then converted it to a for-profit EESC (see the bold vertical arrow in Figure 1) and is therefore appropriate to study the transformation, since the distinctive characteristics between the two forms will be clear. For full disclosure, this case study was also chosen because it permits participant observation, because the author has been working in this business school for 20 years. He was an elected member of the Supervisory Board of the school for almost two years at the time of the study. This experience provided a rich ethnographic color to this research, enriching the insights of engaged scholarship and action research (Bansal et al. 2018). There are no conflicts of interest because the author’s salary or bonuses are not contingent on this research, nor does he own shares in the school. No experiments were performed on any interviewee; therefore, no ethical approvals were taken.

This case study used purposive interviews with the top and middle management of the school. Out of eleven people contacted, eight responded; this is a response rate of 73%, which is high because most of the top management team were known to the author, and he sent follow-up reminders. Four of these eight responses received were oral recorded interviews, and four were written responses. All responses were obtained during April-May 2021. Four of the respondents are women, and four are men.

This research also draws on the CSR report of the school (BSB 2020), and selected information and documents shared by the school. However, many of the interpretative influences and insights have come from the author living in the school’s environment and participating in it before the transformation (as a professor as well as elected Dean of faculty) and after the transformation (as a professor as well as an elected member of the Supervisory Board).

3.2. Case Description

Burgundy School of Business (BSB) is the modern, internationalized brand name given to Ecole Supérieure de Commerce de Dijon (ESC Dijon) that started in 1900 (Chapuis 2000). At the time of opening in 1900, it was considered societally important enough to merit two years of military service exemption for those who obtained a diploma. It was created to fill a vacant geographical niche: there was no business school between Nancy and Lyon, nor between Orleans and Switzerland. The universities had not started teaching business management at that time, so the yoke fell on the Chambers of Commerce and Industry to create such schools, with permission from the national government. Twenty-two students were admitted in 1900 to the first cohort of students. There were two streams: General commerce and banking; and Chemistry, oenology, and viniculture. The faculty were local university professors and schoolteachers who agreed to teach for free, as well as a few specialists from Paris. The dispense for military service ended but the School went on, and 120 years later, at the time of this research, the School had more than 2800 students, 69 full-time permanent faculty, 20 part-time permanent faculty, and 216 adjunct faculty (in 2020) and a dozen bachelor, masters, and M.Sc. programs. The School is still proud to boast of the excellence of its teaching in wine management, and its anchorage in the wine region that is Burgundy (Bourgogne in French).

By and large, the School has been a typical French Ecole Supérieure de Commerce and member of the Chapitre des Grandes Ecoles. In the last twenty years, its position has varied according to the media rankings, but is usually somewhere between 15th and 23rd among French business schools. However, for its work on sustainable development, the French business newspaper Les Echos classified BSB as the seventh among 15 participating schools. Globally, it is among the top one percent of schools, since it has both Equis and AACSB accreditations. When the national government announced that it would be closing many local chapters of the CCIs, the wise men of the region, the department, the city, and the CCI joined together. In 2013, they decided to spin off the school as an independent, not-for-profit association to ensure it remained serving the region since it, contributed significantly to local life.

What is different about BSB is that it is one of seven business schools that has adopted a social business regime created by the French government in 2014: that of the EESC; the school adopted this regime in 2016. Box 3 indicates that both territorial and regional chambers of commerce and industry (CCI) can set up such schools.

Box 3. Amendment by LAW No. 2014–1545 of 20 December 2014.

- Article L711-4 of the Code of Commerce

- The territorial chambers of commerce and industry and the departmental chambers of commerce and industry of Ile-de-France may, alone or in collaboration with other partners, within the framework of the sectoral schemes mentioned in 3° of Article L. 711-8, create and manage initial and continuing vocational training establishments under the conditions provided for in Articles L. 443-1 and L. 753-1 of the Education Code for initial training and, for continuing training, in compliance with the provisions of Title V of Book III of Part Six of the Labour Code which apply to them.

- In the exercise of the powers mentioned in the first subparagraph of this Article, territorial chambers of commerce and industry may set up and manage schools known as consular higher education establishments, under the conditions laid down in Section 5 of this Chapter.

- Note: Article L711-9 of the Code of Commerce provides a similar provision for regional chambers of commerce and industry.

- Note: translation from French by Microsoft Word, verified by author

This regime was created to allow the schools to transfer property from the CCIs to the Business Schools (such as school buildings) without paying taxes. To ensure that profiteers do not swindle the money, the law does not allow shareholders to take dividends. This for-profit but no-dividend model is akin to a social business model proposed by Muhammad Yunus (Yunus and Weber 2007, 2010). Other business schools that have adopted this regime are HEC, ESCP, Audencia, NEOMA, TBS, and Grenoble EM. However, according to the directors, BSB is the only school that has enabled shareholders other than the chambers of commerce and industry to take part in the share capital.

The originality of the Mandon law is the possibility of opening up capital to the private sector even if, in practice, nothing has yet been done on a large scale by any EESC in this field.(Respondent 2, private mail on 6 November 2021)

However, these shareholders have a small share. BSB has a share capital of a little over 10 million Euros. The CCI owns 97.2% of this; 0.9% is owned by two mutualist banks (Banque Populaire and Caisse d’Epargne), 0.7% is owned by local entrepreneurs, and 1.2% is owned by the Dean and Deputy-Dean of the School. Together, this structure constitutes the general assembly of the school.

The school’s legal name is ESC Dijon-Bourgogne, but the commercial brand name is Burgundy School of Business (BSB). Since 1900, more than 16,000 students have graduated from BSB. It partners with more than 350 enterprises that regularly take its students as employees or interns. It has international partnerships with 196 universities in 53 countries. About 25% of its students and 38% of its faculty are international (BSB 2020). 53% of the students and 64% of the staff are women. 25% of the students are from underprivileged backgrounds, evidenced by receiving means-based scholarships from the French State.

Officially, a commitment to CSR was first initiated in 2003. In 2005, the first significant action was to mandate that all students participate in social work as part of their “Citizen Action Education”. Today, they participate with 53 local NGOs. A number of research chairs, partnered with industry, were also created such as the Chair on CSR Chairs (2006), Microfinance (2009), Corporate Governance (2010), Management and Responsible Innovation (2013) and more recently, the Chair of “Evolution of Business Models in the Agri-Food Sector” (2017). More than half the published research is on papers related to CSR. In the teaching modules, about 40% of courses include elements of CSR, including sustainable development goals. On the environmental front, the school has reduced its gas and electricity bills by 18% and has maintained a stable water consumption in the last decade, despite a 20% increase in the general campus area (BSB 2020). Moreover, since 2015, the school is a signatory to the Principles of Responsible Management in Education (PRME) announced by the UN-Global Compact. Table 2 indicates how the school responds to the Principles of Responsible Management in Education.

Table 2.

How BSB responds to PRME principles.

Along with the social bottom line discussed above, BSB has also managed to remain sustainable at the financial bottom line, as shown in Table 3, which recapitulates the history of the school from the last year that it was part of the CCI, the three years that it was a not-for-profit, and the last few years that it has been an EESC social business. The number of students has been increasing steadily by about a hundred students each year. As indicated in the business forecast, expansion into a new Lyon campus may result in a higher growth rate. Total revenue has increased by a different percentage depending on the increase in tuition fees and the product mix chosen by the students (Bachelor’s, Master’s, M.Sc.). This increasing tuition fee is accompanied by a gradual reduction in public financing, which was traditionally at 20% and is now at zero. Despite this elimination of subsidies, the school has been consistently making an operating surplus since it became a social business. The 2020 surplus was extraordinary, perhaps because traveling was restricted. However, much of this surplus will probably be spent on acquiring fixed assets for the new campus in Lyon. The EESC statute does not allow giving a dividend to shareholders.

Table 3.

Financial and Operating results of BSB before the transformation, as a not-for-profit (NFP) and as a social business (EESC).

4. Findings

In this section, we look at the issues of institutional motivation of BSB. Since institutional motivations are enshrined in the vision and mission of the firm, I first discussed this with the respondents. After that, we looked at the motivations for the transformation of the legal status.

4.1. Motivations Emerging from Discussions on the Vision

The question that we asked was the manager’s opinion of the social vision of the school. While the school’s mission has been enshrined in a mission statement, elaborated before the transformation, there is no vision statement and therefore, this first question elicited a variety of responses. We start with the Dean’s response.

The vision is not defined. We consider that the DNA of the school is the capability we have developed to support our students. Our vision is to be recognized as the key player, the key Business School, for the capability to support our students for them to perform in society for the best.(Respondent 6)

This lack of a defined social vision is confirmed by respondent 8

I don’t think we have a “shared vision.”(Respondent 8)

However, building a better society is reflected in other responses, although the way to create a better society may differ for each interviewee. One respondent places stress on the world, another on societal challenges, and yet another on responsible management.

“Making the world a better place through the education of future executives”(Respondent 2)

We should contribute to their education with both societal and business purposes and contribute to the global debates. These include research debate, academic debate but also societal debate.(Respondent 5)

The organization’s social vision is to build a structure where every associate or customer (student) has their proper place. She/he is supported in their job. Diversity and inclusion are taken into account”.(Respondent 7)

In my opinion, the vision is to make BSB, a school that allows the current or future managers of the territory, or more globally, responsible managers.(Respondent 1)

The Deputy Dean’s objective is focused on the school and on its major beneficiary, the students.

We want to be a recognized player at the world level in a field that is training in the spirits wine business, and we have a training model where we really put the student at the heart.(Respondent 4)

4.2. Motivations Emerging from the Discussion on Mission

As mentioned earlier, the school has a mission statement enshrined in its walls as well as on its website:

The school’s mission is to provide current and future managers with high quality education supported by research activities, and to contribute to the development of the region’s economy. Our management education programs are entrepreneurial and internationally focused, allowing students to acquire professional expertise integrating the needs of the business world and corporate social responsibility.

It is difficult for the school to change this without the agreement of the CCI because the law specifically states that a change in the convention would be required for this. Nevertheless, in the interviews we asked for the opinions of the managers on this topic. The Deputy Dean explained the mission statement.

“There are 2 dimensions in the mission of the school: we define ourselves as an educational institution. … which must be anchored in its territory, and contribute to the influence of the territory. The 2nd part of the mission assists more on the dimensions of how, what type of training program, and the major objectives of the training programs that we provide. Relatively strong, this is the dimension that we must also train citizens and not only future managers”.(Respondent 4)

The Dean wonders if the mission statement needs to be revised once the new vision is defined.

The mission is already written. But it needs to be revised based on the revised vision. We will do our best with the professionalization of the accompaniment to transform our students and help them discover their potential and upgrade their potential. That’s our mission for the future.(Respondent 6)

We can see that the Dean does not mention the social purpose except in relation to the beneficiaries (the students). Another manager also stresses accompanying the students.

“Business schools in France are very volume-oriented and have been abandoning the classroom for years for mass teaching, whether in physical or virtual amphitheaters. In contrast, BSB has always wanted to maintain the proximity with its students by teaching in small classrooms, which is financially more expensive”.(Respondent 1)

As opposed to other industries and schools that want to transform their business model digitally, BSB sees an advantage in going against the current and retaining its strength of close contact with students. It is not as if BSB does not understand the importance of digital transformation; it has a specialized master’s in digital leadership. Instead, it has formulated a strategy of differentiation focused on student experience, which requires human interaction.

Other top managers also focus on the students, but may include other societal elements in their opinion. For example, respondent 3 mentions ‘needs and issues’ and respondent 5 mentions ‘territory’ and ‘businesses’.

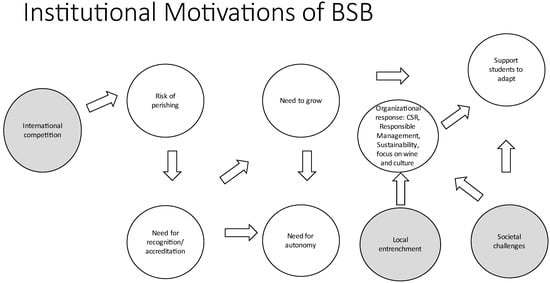

The above findings on the institutional motivation of BSB are summarized in Figure 2. Three environmental factors influence the school’s strategic motivations: international competition, grand societal challenges, and the need for local entrenchment to respond to the dominant shareholder’s interest. Responding to international competition requires accreditations or risking closure. Accreditations require growth, which in turn requires distinguishing a small school from large rivals. The school has focused on an excellent student experience, concentrating on its ability to help students cope with the needs of global business to respond to societal challenges. The requirement for local entrenchment is satisfied by specializing in areas where Burgundy and France have a relatively strong selling proposition: wine and culture. This organizational focus reinforces the social commitment message to students as a live case study. Accreditations also require autonomy, which was the main reason for the legal transformation.

Figure 2.

Institutional motivations of BSB.

4.3. Motivations for Transforming to the Legal Structure of EESC

It is interesting to review the essential legal change inserted by the law of 2014 that amended the French code of commerce. The text of article 753-1 of the Code of Commerce is provide in Box 4. Essentially, owing to this change in legislation, the CCI has three options: they may continue to run their schools as a division of the CCI, spin off as a not-for-profit, or spin off as a for-profit EESC. If the school becomes an EESC, the CCI can transfer assets without taxes.

Box 4. As amended by LAW No. 2014-1545 of 20 December 2014—art. 43 (V).

- Article L. 753-1 of the Code of Commerce

- III.-The territorial chambers of commerce and industry and the regional chambers of commerce and industry may transfer to one or more consular higher education establishments, created in accordance with the second paragraph of Article L. 711-4 or the second paragraph of Article L. 711-9 of the Commercial Code, the goods, rights, obligations, contracts, agreements and authorizations of any kind, including participations, corresponding to one or more institutions of initial and continuing vocational training, within the meaning of the first paragraph of the same Articles L. 711-4 and L. 711-9. Under this transfer, consular higher education institutions continue to issue diplomas under conditions similar to those previously existing. The transfers referred to in the first paragraph of this III shall be carried out automatically and without the need for any formality, notwithstanding any provision or stipulation to the contrary. They entail the effect of a universal transmission of assets and the automatic and informal transfer of the accessories of the assigned receivables and the security interests securing them. The transfer of contracts and agreements in progress, whatever their legal characterization, concluded by the territorial chambers of commerce and industry and the regional chambers of commerce and industry in the context of the transferred activities, is not such as to justify their termination, the amendment of any of their clauses or, where appropriate, the early repayment of the debts which are the subject of them. Similarly, these transfers are not such as to justify the termination or modification of any other agreement concluded by the territorial chambers of commerce and industry and the regional chambers of commerce and industry or the companies linked to them within the meaning of Articles L. 233-1 to L. 233-4 of the Commercial Code. The transfers provided for in this III shall not give rise to the payment of any duties or fees, nor of any tax or salary, nor of any tax or remuneration for the benefit of the State, its agents or any other public person.

- Note: Bold highlights by author

By the responses, we can see that the main elements in favor of the EESC statute are financial. It permits the school to be more autonomous, own its buildings, raise equity capital, and, owing to this, raise debt. There are also no corporate income taxes on schools that adopt this statute. Therefore, the reasons were almost all financial. Only one respondent mentioned a societal aspect: the statute maintains the other advantages of a not-for-profit.

This is how the Dean views the history of the legal transformation of the school in two phases: first, the spinoff from an internal unit of the Chambers of Commerce and Industry to a for-profit and, second, the transformation to an EESC.

We were a part of the Chambers of Commerce. In 2013, thanks to the agreement of the Chamber of Commerce, we decided to move to a not-for-profit association. The not-for-profit was the first level to become more independent, to have more autonomy. However, this legal status is with a lot of problems.

And so, in 2014 there was the new legal status of EESC created by pressure from HEC, which is a sort of blend, some kind of mix between an association and a company, a formal legal company. We have decided to move to this status to gain autonomy and to have the opportunity to issue capital.

And the second aspect is the fact that with the law that has created the EESC model, it was possible for the Chamber of Commerce to transfer the buildings without tax, without a legal notarial commission, and so on.(Respondent 6)

It is interesting to note that he mentions that HEC, France’s premier business school, proposed this change, and we know that the Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus is associated with the social business chair of HEC.

The Deputy Dean considers that adopting the statute of EESC was not done to make BSB a social business. He argues that, on the one hand, the school had been driven by the same purpose even before, as a division of the EESC and as a not-for-profit association; therefore, the overall mission did not change. On the other hand, he questions whether providing business education in a developed country can be considered a social mission.

In 2016, the change to the EESC status kept this dimension that was already present in the associative status… on this dimension of our for-profit, it will not change much.(Respondent 4)

He and the other respondents add other advantages of this statute as drivers for the motivation for conversion to EESC, notably the capacity to use the buildings as collateral to get more funding.

This status guarantees by law, a public majority shareholder, the absence of any blocking minority, the non-distribution of dividends, the impossibility of reducing the capital in order to drain the cash flow by the shareholder, the impossibility of redistributing profits to employees, and the non-taxation of profits: it therefore encourages to make profits, which are 100% reinvested in the social project of the company. It is unique and much more advantageous than a non-profit organization that has no capital and is not necessarily in that perspective. It raises capital, like any private entity, and involves other public or private shareholders.(Respondent 2)

For the renovation, a part of the funding comprises of subsidies from the Regional Council, but most has been largely on a loan subscribed by the school. For this, it had to have assets of its own, as security.(Respondent 4)

Here is an interesting observation that ties in with the observation that context also motivates the creation of social enterprises (Sinapi and Juno-Delgado 2015).

But I know two of the main motivations because we were in association and we moved to this legal status. One was a bit political. The French political context for the Chamber of Commerce was changing, and Chamber of Commerce were the owners of our buildings and had a lot of money. The State was going to take this money at the global level, well to transfer it from regional Chamber of Commerce to more global level. So, it was also a way to keep on the territory and for the school the assets which were preliminary, identified as assets of the school.(Respondent 5)

This observation is very interesting because it conforms with the author’s own experience of the story told to employees to accept the change: the CCI may disappear, and so may our jobs if we do not transfer out from a CCI. However, it contrasts with the version explained to the French National Assembly by the reporter who analyzed the bill (Errante 2014). This report affirms the need for autonomy of business school to be based on international rankings and audits. Since CCIs have a number of technical schools that may be very locally oriented at the same time as internationally prestigious business schools, the percentage of international students reported for the CCI as a whole may be much lower than those of their business schools division. As a result, the business schools are penalized if they remain part of the CCI.

Consular schools are evolving in an increasingly globalized world. According to the Court of Auditors, the share of teachers of foreign nationality at HEC increased from 12% in 1998 to 58% in 2012. This phenomenon of openness has accelerated under pressure from international accreditation agencies and world rankings, some of whose criteria are based on financial autonomy and the sustainability of the structure. As a result, consular schools are penalized by their status in international competition. They must therefore adapt their model in order to continue to attract the best professors and students whose recruitment is now taking place on a global basis.(Errante 2014)

The report makes no mention of the disappearance of local CCIs or threats to the jobs of the professors or staff of the CCI.

The law talks about allowing the opening of the equity capital of business schools to outside investors, providing the CCI maintains most of the equity and no one investor has a blocking minority, but these provisions mean that it is challenging to find investors.

The great difficulty with which we are confronted is the status of EECEs. The Mandon law prohibits the distribution of dividends which is a big brake for integrating private partners in a company. In practice, it is the only horizon that allows the generation of profits for these new shareholders, and exit is the only way of cashing in by reselling the shares. However, there is no secondary market for these shares in the education market, even if we talk a lot about investment funds.(Respondent 1)

Table 4 summarizes the institutional motivations to transform at the two stages: from the internal unit of the CCI to an Association; and from an Association to an EECS.

Table 4.

Instituional motivations for legal transformation from Consular Unit to Social Business.

5. Discussion

As we have seen, the EESC statute closely resembles Yunus’s seven social business principles. First, the school’s mission concerns education and is not related to profit maximization. Second, the school has to be financially and economically viable. Third, the EESC statute does not allow giving dividends. However, contrary to the third principle, the EESC statute permits investors to exit at the ending book value and not at the par value. Despite this, it seems to be difficult to get investors. All other profits remain with the company as per the fourth principle. The school is gender sensitive and environmentally conscious. The workforce receives market wages, and, from the author’s experience, most colleagues work with joy. A problem may be overworking, since employees often do too much, leading to stress and the possibility of burnout. So, we can say that most principles of Yunus’s social business model characteristics are respected.

There seems to be a tension between the desire of the CCIs to spin off their schools and yet retain control. This tension requires trust in the managers and appropriate governance mechanisms. Currently, the CCIs own 100% of most of their EESCs (the commercial code requires them to hold a majority of shares). Therefore, it is unclear whether the EESCs have really been privatized, yet they have gained autonomy. Literature on privatization considers various factors that influence privatization such as low externalities, low need to subsidize losses, difficulty in monitoring managers, and exposing firms to competition to increases efficiency (Vickers and Yarrow 1991). Our study finds that privatization was done to increase the standing of the business schools in business school rankings and accreditations, and thus increase their competitiveness rather than their efficiency. Therefore, the context was a primary factor in motivating the transformation to an EESC statute, and not merely a tertiary factor that appears in creating a social enterprise, as found by Sinapi and Juno-Delgado (2015). The pro-social motivation was already inherent in the CCI and the not-for-profit association; as a result, it did not motivate the transformation. However, the instrumental motive of autonomy pushed BSB into spinning off as a not-for-profit, and the need for further financial sustainability pushed it to transform into an EESC. This leads us to the following theoretical proposition.

P1:

International competition may lead to States transferring public enterprises and making them private not-for-profits to increase their autonomy, growth, and international ranking.

Ashta (2020) indicates that when not-for-profit MFIs were transformed into for-profits, in many cases, the for-profit continued to be controlled by an NGO, but assets were transferred. In the present study, we can see that the new statute also allowed the transfer of assets. At the same time, CCIs remained the majority shareholders, but they may choose to let the decision-making in the hands of other stakeholders more directly connected with the market. Therefore, we can formulate the following hypothesis.

P2:

When States transfer public assets to a private social enterprise, they need to ensure that there is a mechanism to balance State control with autonomy.

Ashta (2018) indicated that for-profit social enterprises have difficulty announcing their vision and mission. Our case study suggests that this vision is not yet defined or shared in this school, but the Dean focuses neither on the organization nor on the broader society, but on the direct beneficiaries.

P3:

Social businesses vision and mission statements are likely to focus on their direct beneficiaries.

Many authors have considered a desire for growth and autonomy from charity-based stakeholders to be the basis of the transformation of not-for-profits to for-profit social enterprises. In our case, the desires for autonomy and for the ability to raise capital and finance growth were present. But these could have been satisfied by converting to a pure for-profit. Instead, to save taxes of various sorts, the business schools conserved control by the CCI and remained a social business that does not give dividends.

P4:

Firms that transform to for-profit social enterprises are likely to agree to control by the State in return for greater autonomy (operational and financial) and lower taxes.

6. Concluding Remarks and Future Research Directions

This research is embedded in the stream of strategic management that considers that context matters. It has looked at how global rankings influenced the spinning off of business schools from CCIs and the creation of social business. It has studied the motivations emanating from a discussion on the overall vision and mission of the school and the reasons for adopting the change in legal status. The propositions for theory building outlined in the previous section focus on the motivations of a public enterprise in spinning off a unit, and the control mechanisms necessary to ensure that there are no hidden private transfers and that the social business focuses on the beneficiaries. Future research in this direction should study the change in governance owing to the change in legal status.

The context has changed for all business schools in France, yet only seven changed their legal status. This, therefore, provides a unique opportunity for a multiple-case study to examine what are the conditions that determine whether business schools cross the tipping point and transform. This would further advance the theory of context’s role in strategic management.

A major advantage of qualitative research is that it often allows us to explore and reflect on unexpected areas, leading to serendipitous discoveries. According to Moore (2018), the history of universities started with educating students on broader questions of life (theology, languages, philosophy) and medicine. Research, or knowledge creation, was added as a second function in the early nineteenth century. In response to the first function business education also started in the nineteenth century, but was often undertaken by non-university institutions. This education was to prepare students for employment. However, the university-based institutions started research activities in business and management also. Independent business schools, such as the consular business schools in France, started research near the end of the 20th century. The author himself was present in BSB when research was informally initiated by a small group (headed by Sophie Reboud, but including the author) in 2002 and launched its working paper series “Cahiers du CEREN” in December 2002. The official research center CEREN was inaugurated in 2003. The third function of universities has been knowledge transfer to create innovations. This knowledge transfer function is more difficult for business schools since they are not dealing with technical science. Although the director of research is also in charge of knowledge transfer, little activity seems to be happening within the knowledge transfer domain of innovation with industry. To be fair, we provide the response of respondent 8, who was one of the four respondents who reviewed the paper at the end.

It depends on the definition you give to “transfer”. Important work has been done for five years (guided partly by accreditations) with the notion of the impact of research on the different stakeholders: and we find a lot of elements to highlight what we do in research (for students, for practitioners, for the territory, for the society as a whole).(Respondent 8, review comment, 10 November 2021)

If the vision and mission of the BSB are limited to education and research, knowledge transfer for innovation will be consigned to supporting functions, thereby restricting the ranking of the school, which in turn influences its student intake. If future rankings include knowledge transfer for innovations, this may not affect BSB if this limits all business schools. However, university-controlled schools may leap ahead since they are also teaching scientific subjects. Therefore, future researchers should look at how global rankings influence the reorganization of the schools to address such functional lacunae. Alternatively, stand-alone business schools may need to regroup with universities or stand-alone engineering schools for this function.

Another serendipitous outcome of this study explains why the business school has opted out of the digital transformation of its business model. Being a small social business school, it has adopted a niche strategy focusing on its students’ beneficiaries. COVID-19 has confirmed that students in their target segment would like face-to-face classes and human support.

One policy recommendation from this case study is that if the PRME wants business schools to move towards Responsible Education or Sustainable Development, then the accreditation criteria will need to provide further weight to such themes.

The external applicability of this case study in the education sector may be limited, but some reflections could be broader. In our case, a concern with international rankings and certification has led to adopting the social business form for French education institutions. A similar shift is occurring in the financial world, where large impact investors are placing their funds on groups with solid international environmental, social, and governance ratings. Firms like Danone are tempted to claim special status as enterprises in the public interest.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Laurence Attuel-Mendes, Stéphan Bourcieu, Anne-Laure Brochet, Olivier Léon, Gilles Mesnard, Anne Michelot, Christine Sinapi, to the participants of the 8th Responsible Management Education in Suzhou China (October 2021) and the 10th Social Business Academic Conference (November 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Arend, Richard J. 2013. A Heart-Mind-Opportunity Nexus: Distinguishing Social Entrepreneurship for Entrepreneurs. Academy of Management Review 38: 313–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashta, Arvind. 2009. Creating a World without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism, by Muhammad Yunus (with Karl Weber). New York: BBS Public Affairs. 2007. Paperback: ISBN 13 978 1 58648 579 5, $16.00. 261 pages. Journal of Economic Issues 43: 289–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ashta, Arvind. 2018. Realistic Theory of Social Entrepreneurship: Selling Dreams as Visions and Missions. Cost Management 32: 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ashta, Arvind. 2020. A Realistic Theory of Social Entrepreneurship: A Life Cycle Analysis of Micro-Finance. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan, Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Michael J. 2016. Looking back, going forward. Social Business 6: 325–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, Pratima, Wendy K. Smith, and Eero Vaara. 2018. New Ways of Seeing through Qualitative Research. Academy of Management Journal 61: 1189–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, Karin. 2018. Social Entrepreneurship: Performance enactments of compassion. In Social Entrepreneurship: An Affirmative Critique. Edited by Pascal Dey and Chris Steyaert. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 159–81. [Google Scholar]

- BSB. 2020. 3ème Rapport de Responsabilité Sociétale. Available online: https://www.bsb-education.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/BSB-rapport-annuel-RSE-2021-FR-1.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Campion, Anita, and Victoria White. 2001. NGO Transformation. Bethesda: Microenterprise Best Practices. Available online: https://www.findevgateway.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/mfg-en-paper-ngo-transformation-jun-2001.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Chapuis, Claude. 2000. Rue Sambin: Rue Sambin: Histoire et Petite Histoire de l’ESC Dijon 1900–2000. Dijon: Groupe ESC Dijon Bourgogne. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Kevin D., Scott L. Newbert, and Narda R. Quigley. 2018. The motivational drivers underlying for-profit venture creation: Comparing social and commercial entrepreneurs. International Small Business Journal 36: 220–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J. Gregory. 1998. The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship. Kansas City: Kauffman Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, Sarah E., and Matthew L. Sanders. 2010. Meaningful work? Nonprofit marketization and work/life imbalance in popular autobiographies of social entrepreneurship. Organization 17: 437–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, Andreas, Vishal Gupta, Lis Strenger, and Malte Brettel. 2015. Entrepreneurial Orientation, Firm Performance, and the Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership Behaviors. Journal of Management 41: 1069–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errante, Sophie. 2014. Rapport 2145 au Nom de la Commission Spéciale Chargée D’examiner le Projet de loi (n° 2060), Après Engagement de la Procédure Accélérée, Relatif à la Simplification de la vie des Entreprises; Paris. Available online: https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/14/rapports/r2145.asp (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Faust, Luisa, Maura Kolbe, Sasan Mansouri, and Paul P. Momtaz. 2022. The Crowdfunding of Altruism. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furceri, Davide, and Ricardo M. Sousa. 2011. The Impact of Government Spending on the Private Sector: Crowding-out versus Crowding-in Effects. Kyklos 64: 516–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, Matthew G., Jeffery S. McMullen, Timothy J. Vogus, and Toyah L. Miller. 2013. Studying the Origins of Social Entrepreneurship: Compassion and the Role of Embedded Agency. Academy of Management Review 38: 460–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Robert C., and Michael Levenhagen. 1995. Metaphors and Mental Models: Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Innovative and Entrepreneurial Activities. Journal of Management 21: 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, Helen. 2008. ‘Doing Deals on the House’ in a ‘Post-welfare’ Society: Evidence of Micro-Market Practices from Britain and the USA. Housing Studies 23: 213–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, Ewald, Joakim Wincent, Teemu Kautonen, Gabriella Cacciotti, and Martin Obschonka. 2019. Can prosocial motivation harm entrepreneurs’ subjective well-being? Journal of Business Venturing 34: 608–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmitt, Jonathan, and Pablo Muñoz. 2018. Sensemaking the ‘social’ in social entrepreneurship. International Small Business Journal 36: 859–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klettner, Alice, Thomas Clarke, and Martijn Boersma. 2014. The Governance of Corporate Sustainability: Empirical Insights into the Development, Leadership and Implementation of Responsible Business Strategy. Journal of Business Ethics 122: 145–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleynjans, Lauren, and Marek Hudon. 2016. A Study of Codes of Ethics for Mexican Microfinance Institutions. Journal of Business Ethics 134: 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Wai Wai, Gordon Liu, Wan Toren Wan Yusoff, and Che Rosmawati Che Mat. 2018. Social Entrepreneurial Passion and Social Innovation Performance. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 48: 759–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koe Hwee Nga, Joyce, and Gomathi Shamuganathan. 2010. The Influence of Personality Traits and Demographic Factors on Social Entrepreneurship Start Up Intentions. Journal of Business Ethics 95: 259–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, Thomas B., and Sally Maitlis. 2012. Care and Possibility: Enacting an Ethic of Care Through Narrative Practice. Academy of Management Review 37: 641–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, Andy. 1995. The basic social processes of entrepreneurial innovation. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 1: 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, Johanna, Ignasi Marti, and Marc J. Ventresca. 2012. Building Inclusive Markets in Rural Bangladesh: How Intermediaries Work Institutional Voids. Academy of Management Journal 55: 819–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, Ignasi, and Johanna Mair. 2009. Bringing change into the lives of the poor: Entrepreneurship outside traditional boundaries. In Institutional Work: Actors and Agency in Institutional Studies of Organizations. Edited by Thomas Lawrence, Roy Suddaby and Bernard Leca. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, P. R. 2020. The Community Interest Company. Social Business 10: 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Toyah L., Matthew G. Grimes, Jeffrey S. McMullen, and Timothy J. Vogus. 2012. Venturing for Others with Heart and Head: How Compassion Encourages Social Entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review 37: 616–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, John C. 2018. A Brief History of Universities. Cham: Plagrave Macmillan, Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Morel, Nathalie, Chloé Touzet, and Michaël Zemmour. 2019. From the hidden welfare state to the hidden part of welfare state reform: Analyzing the uses and effects of fiscal welfare in France. Social Policy & Administration 53: 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muff, Katrin, Anna Liechti, and Thomas Dyllick. 2020. How to apply responsible leadership theory in practice: A competency tool to collaborate on the sustainable development goals. Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management 27: 2254–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nason, Robert S., Sophie Bacq, and David Gras. 2018. A Behavioral Theory of Social Performance: Social Identity and Stakeholder Expectations. Academy of Management Review 43: 259–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, Alex. 2010. Institutionalizing social entrepreneurship in regulatory space: Reporting and disclosure by community interest companies. Accounting, Organizations and Society 35: 394–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, James. 2019. The Prospects for Enlightened Corporate Leadership. California Management Review 61: 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pless, Nicola, and Jenny Appel. 2012. In Pursuit of Dignity and Social Justice: Changing Lives through 100% Inclusion-How Gram Vikas Fosters Sustainable Rural Development. Journal of Business Ethics 111: 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawhouser, Hans, Michael Cummings, and Andrew Crane. 2015. Benefit Corporation Legislation and the Emergence of a Social Hybrid Category. California Management Review 57: 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruskin, Jennifer, Richard G. Seymour, and Cynthia M. Webster. 2016. Why Create Value for Others? An Exploration of Social Entrepreneurial Motives. Journal of Small Business Management 54: 1015–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, Tina, Nicolai J. Foss, and Stefan Linder. 2019. Social Entrepreneurship Research: Past Achievements and Future Promises. Journal of Management 45: 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Filipe. 2012. A Positive Theory of Social Entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics 111: 335–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinapi, Christine, and Edwin Juno-Delgado. 2015. Motivations for establishing cooperative companies in the performing arts: A European perspective. In Advances in the Economic Analysis of Participatory & Labor-Managed Firms. Edited by Antti Kauhanenn. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Wendy K., Marya L. Besharov, Anke K. Wessels, and Michael Chertok. 2012. A Paradoxical Leadership Model for Social Entrepreneurs: Challenges, Leadership Skills, and Pedagogical Tools for Managing Social and Commercial Demands. Academy of Management Learning & Education 11: 463–78. [Google Scholar]

- Starr, Paul. 1988. The meaning of privatization. Yale Law & Policy Review 6: 6–41. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, Ute, Malcolm Patterson, Ciara Kelly, and Johanna Mair. 2016. Organizations Driving Positive Social Change. Journal of Management 42: 1250–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, John, and Bob Doherty. 2006. The diverse world of social enterprise. International Journal of Social Economics 33: 361–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tišma, Sanja, Sanja Malekovic, Daniela Angelina Jelincic, Mira Mileusnic Škrtic, and Ivana Keser. 2022. From Science to Policy: How to Support Social Entrepreneurship in Croatia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, Antoni, Clara Fontdevila, and Adrián Zancajo. 2017. Multiple paths towards education privatization in a globalizing world: A cultural political economy review. Journal of Education Policy 32: 757–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, John, and George Yarrow. 1991. Economic Perspectives on Privatization. Journal of Economic Perspectives 5: 111–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitshaki, Ronit, and Fredric Kropp. 2016. Motivations and Opportunity Recognition of Social Entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management 54: 546–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Maia J., Michael W. Morris, and Vicki M. Scherwin. 2013. Managerial Mystique: Magical Thinking in Judgments of Managers’ Vision, Charisma, and Magnetism. Journal of Management 39: 1044–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, Muhammad, and Karl Weber. 2007. Creating a World without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism. New York: Bbs Public Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, Muhammad, and Karl Weber. 2010. Building Social Business: The New Kind of Capitalism That Serves Humanity’s Most Pressing Needs. New York: Public Affairs. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).