Simple Summary

Prostate cancer survivors often need long-term follow-up to manage side effects of treatment and monitor relapse or progression. It is unknown which patients seek routine follow-up visits, and how often, at specialized cancer hospitals. In this study, we looked at which patient characteristics were related to how frequently survivors saw their radiation oncologist, starting three years after completing radiation treatment. We found that patients at higher risk had more frequent follow-up visits with radiation oncology, while lower-risk patients were seen less. Overall, the number of survivors returning for radiation oncology follow-up dropped by more than 46% over five years, which suggests that care is being tapered appropriately over time. Still, more than 23% of survivors were seeing their radiation oncologist in the fifth year after treatment, and over half of these patients were considered lower risk. This shows that even though follow-up generally aligned with patients’ needs, many lower-risk survivors continued longer-term follow-up with radiation oncology. Transitioning the ongoing care of lower-risk patients to their primary care providers enables long-term follow-up closer to home, while ensuring a sustainable cancer care system.

Abstract

Prostate cancer survivors require coordinated long-term care after treatment. We examined patterns of follow-up care and identified characteristics associated with the frequency of radiation oncology (RO) visits during survivorship. We conducted a population-based cohort study of men diagnosed with prostate cancer between April 2010 and March 2019 in Ontario, Canada, who underwent first-line radiotherapy. Survivorship began three years following radiation. Using a recurrent event framework, we identified demographic and clinical characteristics associated with the rate of RO follow-up. Survivors seeking RO follow-up declined by 46.2% over five years of survivorship. Higher-risk characteristics, such as higher ISUP grade, higher stage, detectable prostate-specific antigen (PSA) score, and receipt of brachytherapy and/or hormones, were associated with more frequent RO visits. For instance, relative to International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Grade 1, those with Grades 3 through 5 experienced follow-up rates that were 20%, 25%, and 34% higher, respectively. Despite concordance between patient risk and rate of RO follow-up, 23.6% of survivors continued to visit their RO providers into their fifth year of survivorship, more than half of whom were ISUP grades 1–2. Primary care follow-up remained stable. While frequency of RO follow-up appropriately reflected patient risk profile, many low-risk survivors still sought long-term RO-led care. This suggests an opportunity to encourage lower-risk prostate cancer survivors to seek follow-up care with their general practitioner.

1. Background

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy among Canadian men, accounting for 20% of all new diagnoses, and has a favourable 5-year survival rate of 91% [1]. The growing population of prostate cancer survivors underscores the importance of survivorship as a crucial area of research [2,3,4]. Survivorship refers to the phase of cancer care following initial diagnosis and treatment [5,6,7,8]. This stage focuses on addressing the long-term physical, emotional, and psychosocial needs of cancer survivors as they transition away from active treatment and adapt to living with lasting effects of the disease [9,10,11]. For prostate cancer, this includes the coordination of care among oncology, urology, and primary care across the patient’s lifespan, culminating in the easing of oncology-led care after the completion of post-treatment follow-up [12,13]. Prostate cancer survivors often face challenges in navigating a complex healthcare system, as they seek the necessary long-term care and support particularly during the transition away from oncology-led care within a specialized cancer institution [14,15,16]. Transitioning to general practitioner (GP)-led care in their home community can be difficult, as survivors adjust to being managed by a primary care provider outside of the auspices of the cancer care system, while concomitantly identifying and addressing treatment-related side effects and adjusting to new surveillance expectations [17]. Despite these challenges, transitioning away from specialized oncology care is an important and necessary step in the care continuum to avoid placing undue constraints on an already overburdened cancer care system. Real-world evidence illustrating patterns of follow-up care as well as identifying demographic and clinical characteristics associated with RO involvement among prostate cancer survivors are limited. We aimed to characterize survivorship care following completion of first-line radiotherapy in a population-based cohort, focusing on patterns of RO follow-up and factors associated with the presence and frequency of RO visits. Our findings can inform the development of personalized, risk-specific prostate cancer survivorship guidelines to facilitate a safe and efficient transition from the cancer care system, ultimately improving the long-term health outcomes, well-being, and quality-of-life of patients as they navigate the healthcare system during survivorship.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Sources

Using the Ontario Cancer Registry (OCR), we conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study of prostate cancer survivors who opted for radiation as their first-line therapy. The OCR captures over 95% of all incident cancers diagnosed in Ontario, Canada [18,19], and comprises detailed clinical information such as site, morphology, TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) staging, International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grade via Gleason score, and diagnosis date. We deterministically linked the OCR to other administrative healthcare databases to comprehensively examine all health services and treatments sought after diagnosis. Data regarding receipt of cancer treatment(s) were obtained from the Cancer Activity Level Reporting database, New Drug Funding Program database, Ontario Drug Benefit Program database, and cancer clinic data collected via the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System. Office-based outpatient visits to radiation oncology, urology, and primary care were ascertained from physician remuneration data in the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database; the ICES Physician Database (IPDB), via encrypted physician identifiers, discerned medical specialty. Demographic and mortality data were extracted from the Registered Persons Database. Lastly, laboratory tests for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) were captured in the Ontario Laboratory Information System. Detailed descriptions of all data holdings and definitions used in this study are provided in the Supplemental Material (Tables S1 and S2, respectively, online only). These databases were linked and analyzed at ICES (formerly known as the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences) using a unique encoded patient identifier.

2.2. Cohort Description

Our cohort included all Ontario residents diagnosed with incident prostate cancer between 1 April 2010, and 31 March 2019, inclusive (Figure S1, online only). Prostate cancer diagnoses were extracted from the Ontario Cancer Registry (OCR) using the International Classification of Disease, Oncology, 3rd Revision (ICD-O-3: C61). Given that our focus was to study those who underwent radiation as their first-line therapy (i.e., not salvage radiation), we excluded patients with prostate cancer who did not initiate radiation within one year of their diagnosis, received radical prostatectomy, or whose first-line radiotherapy regimen duration was atypical, defined as exceeding 90 days. We also excluded patients not suitable for survivorship; this excluded anyone who received radiation to a body region other than the prostate or pelvis (e.g., lung, brain), received chemotherapy, or was diagnosed with de novo metastatic disease. Additionally, we excluded in situ diagnoses, those who died before the start of survivorship, those aged younger than 18 years or older than 105 years, non-residents of Ontario, those not eligible for Ontario’s universal provincial health coverage (i.e., emigration), or non-community dwellers (e.g., living in a long-term care facility or receiving palliative care services). The creation of our incident survivorship cohort resembled that of previous studies examining survivorship outcomes of common cancers [20,21,22,23].

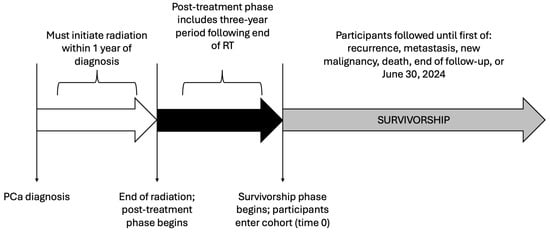

Patients eligible to enter the cohort were observed during two distinct and consecutive phases of care: (1) post-treatment and (2) survivorship (Figure 1). The post-treatment phase of care encompassed the three-year period immediately following the completion of first-line radiotherapy, as three years was an adequate duration for the patient to clinically stabilize. This includes completion of hormonal therapy and related follow-up [24], and for the PSA to reach nadir [25]. This approach is further supported by survey evidence indicating that Canadian primary care practitioners report comfort assuming responsibility for survivorship care around this time frame [26]. To minimize misclassification of patients entering survivorship, we implemented a “wash-out” to exclude individuals likely to represent (1) early biochemical relapse prior to survivorship or (2) higher-risk cases intended to remain on prolonged hormonal therapy. Specifically, we removed patients who dispensed hormones during the 6-month interval immediately before the start of survivorship (i.e., 2.5–3 years after radiotherapy). We evaluated the robustness of our findings through two sensitivity analyses: (1) applying a longer 1-year wash-out period and (2) no wash-out.

Figure 1.

Study participant timeline.

During the survivorship phase of care, we observed all outpatient follow-up visits to RO, urology, and primary care. In Ontario, medical oncology is not involved in routine post-radiotherapy follow-up care for prostate cancer and was not included in this study. Participants were followed throughout survivorship until re-initiation of radiation, receipt of chemotherapy, or dispensation of hormonal therapy (i.e., probable recurrence/relapse and/or metastases), diagnosis of a new primary malignancy, death, loss to follow-up, or 30 June 2024, whichever occurred first.

2.3. Clinical Endpoints

Our primary outcome was the rate of RO follow-up during the complete survivorship phase of care. Secondarily, we examined three mutually exclusive groups based on the frequency of follow-up during the first year of survivorship [i.e., days 1096–1460 (4th year) following the end of radiation]: (1) those who ‘transitioned’ in the first year of survivorship (i.e., no outpatient visits with a RO), (2) those who received ‘de-intensified’ care (i.e., one or two outpatient visits with a RO), and (3) those who received active follow-up (i.e., three or more RO visits). RO administers treatment and follow-up care within highly specialized cancer hospitals. The absence of such visits during the first year of survivorship identifies patients who have left the cancer care system to seek continuing care and ongoing surveillance with their GP [20].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared across those who transitioned, received de-intensified follow-up, or received active follow-up (Table 1). Standardized differences (SD) > 0.1 were considered statistically important, consistent with large-sample epidemiological studies [27]. We employed a recurrent event framework to identify demographic and clinical characteristics associated with the rate of RO follow-up during survivorship (primary outcome). Using an Anderson-Gill counting process model (Table 2; Model 1), we regressed baseline characteristics on RO follow-up visits that occurred during survivorship until the patient was censored.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by volume of radiation oncology follow-up during first year of survivorship.

Table 2.

Multivariable model estimates for radiation oncology (RO) follow-up.

Over 30% of our cohort transitioned in the first year of survivorship (i.e., no RO visits). Therefore, we employed log-binomial regression to estimate adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) by modelling the probability of at least one outpatient RO visit during the first year of survivorship against baseline characteristics (Table 2; Model 2) [28]. Covariates for both models were selected based on clinical domain knowledge of the authors, conditional on data availability. This included age at diagnosis, geographic remoteness [29], socioeconomic status [30,31,32], access to primary care, and number of comorbidities quantified via the CIHI Population Grouping methodology [33]. We also included clinical information such as diagnosis of a previous malignancy, ISUP grade, TNM stage, most recent PSA score prior to commencement of survivorship, receipt of brachytherapy and/or hormones, and the occurrence of radiation-related complications. Gleason scores less than or equal to 6 were categorized as ISUP Grade 1, 7 (3 + 4) as Grade 2, 7 (4 + 3) as Grade 3, 8 as Grade 4, and 9–10 as Grade 5. Continuous covariates not linearly associated with the outcome (i.e., age and remoteness) were accounted for using restricted cubic splines. Furthermore, since the Anderson-Gill model can accommodate time-varying covariates, we included the number of follow-up visits to urology or primary care during survivorship.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide version 8.3 (Cary, NC, USA). This study received ethics approval from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (project #15712).

3. Results

Our cohort included 12,866 Ontario men diagnosed with prostate cancer between April 2010 and March 2019 who received first-line radiotherapy. The mean age at diagnosis was 73.5 years (standard deviation [SD] = 7.3), ranging from 46 to 95 years, and survivors were followed for an average of 1769 days (SD = 1012.0) during the survivorship period. Over the full observation window (maximum 4012 days), 15.5% (n = 1994) experienced a suspected recurrence or metastasis, defined as re-initiation of radiation, receipt of chemotherapy, or dispensation of hormones, 5.4% (n = 688) developed a new primary cancer, and 11.9% (n = 1525) died. The remaining participants (n = 8659) were lost to follow-up (i.e., emigration) or censored at the end of follow-up. Kaplan-Meier curves for all-cause mortality are presented in Figure S2.

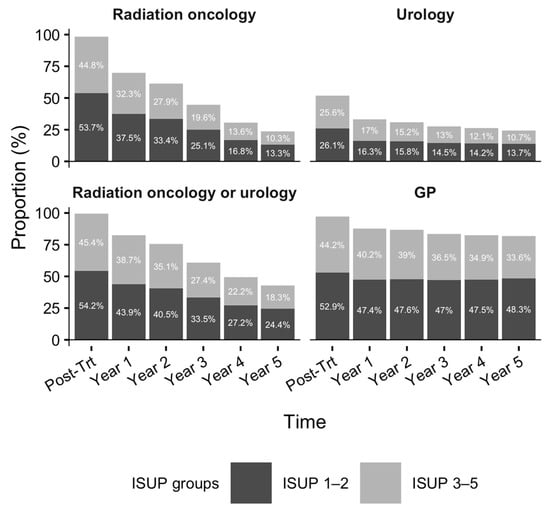

During the post-treatment phase, nearly all survivors had at least one RO (98.5%, n = 12,671) and GP (97.0%, n = 12,485) visit, while 51.7% (n = 6657) saw a urologist (Figure 2). As survivorship progressed, the proportion seeing RO providers declined by 46.2%, whereas decreases in urology (8.9%) and primary care (5.7%) visits were modest. By the fifth year of survivorship, 23.6% continued to receive RO follow-up; however, more than 50% of these were low-risk survivors (ISUP Grades 1–2). Moreover, 24.4% and 81.9% sought care from a urologist and GP, respectively.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients with at least one office visit to radiation oncology, urology, or general practitioner during the first five years of survivorship. Footnote: Denominators for the post-treatment phase to the 5th year of survivorship (in order) are n = 12,866, n = 12,866, n = 12,145, n = 11,104, n = 8836, and n = 6887, respectively. Figure 2 was produced using R version 4.5.1 [34].

Baseline characteristics were compared by the frequency of care sought by radiation oncology during the first year of survivorship (i.e., days 1096–1460 following the end of radiation) (Table 1). In the first year, 30.2% (n = 3884) of study participants were considered as ‘transitioned’, in other words, had no follow-up visits with RO. Nearly two-thirds (64.7%; n = 8321) sought ‘de-intensified’ care within a cancer center (i.e., 1–2 visits with RO). A small proportion of the patients (5.1%; n = 661) were actively receiving RO-led care (i.e., three or more visits). Clinical characteristics, including TNM stage, ISUP grade, and most recent PSA score, were similar between patients who transitioned and those who sought ‘de-intensified’ RO follow-up. However, at baseline, among those who sought active care (i.e., 3+ RO visits) relative to those who transitioned, there were 3.7% more patients with ISUP Grade 5, 7.2% more with ISUP Grade 3, and 11.7% fewer patients with low-grade cancer (ISUP Grades 1 or 2). Similarly, 13.0% of survivors under active care were diagnosed with TNM stage III versus 7.8% among those who transitioned. Likewise, a detectable PSA score was 20.7% more prevalent among those under active RO-led care. More survivors who sought de-intensified or active RO follow-up received a combined administration of external beam radiation and brachytherapy (18.9% and 18.0%, respectively), while conversely, external beam radiation directed only to the prostate was most common among transitioned survivors (65.4%).

The volume of outpatient radiation oncology (RO) follow-up throughout the survivorship phase of care was largely driven by clinical characteristics of the cohort-qualifying prostate cancer (Table 2). Upon multivariable adjustment, we discovered that ISUP grade, TNM stage, and most recent PSA score exhibited a dose–response relationship with the frequency of RO follow-up: compared to patients with ISUP Grade 1, RO follow-up rate increased for Grades 3, 4, and 5 by 20%, 25%, and 34%, respectively. Alike, stages II and III had a higher rate of follow-up than stage I (15% and 29%, respectively), as well as those with a detectable PSA score relative to those with an undetectable score (21%). Receipt of brachytherapy, whether as a monotherapy or combined with external beam radiation, or hormonal therapy was also associated with a higher rate of radiation oncology follow-up (16%, 11%, and 5%, respectively). As the number of pre-existing comorbidities increased, so too did the rate of RO follow-up (5% per 3 additional comorbidities). The occurrence of urological and rectal/anal complications attributed to radiotherapy also increased the rate of follow-up by 20% and 10%, respectively, as well as those requiring open surgery (25%). Lastly, the involvement of other medical specialties relevant to the ongoing care of prostate cancer survivors—urology and family medicine—influenced the frequency of RO-led care. For instance, each additional outpatient visit to urology or family medicine during survivorship reduced the rate of RO follow-up by 12% and 5%, respectively. Additionally, we discovered that patients not rostered to primary care experienced an 18% lower rate of radiation oncology follow-up.

Finally, like the rate of radiation oncology follow-up, we demonstrated that the probability of seeking any RO care in the first year of survivorship (i.e., at least 1 visit) was associated with clinical risk and complexity, reflecting survivors who are not suitable for transition away from radiation oncology and require more intense monitoring within the cancer care system. This included those with a detectable PSA score, and receipt of brachytherapy and/or hormones. Conversely, patients of advanced age, those residing in more rural and remote regions, and those not rostered to a primary care physician were more likely to transition out of the cancer care system. ISUP grade or TNM stage were not related to the probability of any RO follow-up during the first year of survivorship.

4. Discussion

In this population-based study of prostate cancer survivors treated with first-line radiotherapy, we characterized patterns of follow-up across radiation oncology, urology, and primary care, and identified factors associated with more frequent radiation oncology (RO) involvement during survivorship. More than 30% of survivors transitioned away from RO-led care during the first year of survivorship, while others continued to receive RO follow-up later into their survivorship phase of care. Overall, our findings suggest that radiation oncology largely follow a risk-informed approach, as survivors with higher TNM stage, detectable PSA, higher ISUP grade, radiation-related complications, or those receiving brachytherapy and/or hormonal therapy were seen more frequently by RO providers. These patterns are consistent with the clinical need for closer monitoring among survivors at higher risk of recurrence or with more complex post-treatment trajectories, and equally, are reflective of lower-risk survivors who are better positioned to completely transition out of the cancer care system and shift toward long-term GP-led surveillance.

Despite the concordance between risk features (e.g., ISUP grade) and frequency of RO follow-up during survivorship, a considerable proportion of lower-risk survivors—those with ISUP grades 1 or 2—continued to receive RO follow-up in the fifth survivorship year, or eighth year following completion of radiation. While some of these visits may reflect lingering long-term treatment-related side effects, patient preference, or limited access to a primary care physician, these findings highlight an opportunity to optimize survivorship pathways by identifying appropriate candidates for earlier transition to general practitioner (GP)-led care. The inverse association between RO follow-up frequency and concurrent outpatient visits to urology and primary care further suggests that coordination with other relevant specialties may help facilitate transition away from RO-led care. Key tenets of cancer survivorship include the safe transition of patients from oncological to primary care [35], in addition to effective coordination and communication across medical specialties [36] (oncology, urology, and primary care) to maintain care continuity and optimize long-term outcomes and quality of life for survivors [37,38,39,40]. As over one-fifth of study participants, followed for an average of five years, experienced probable recurrence, metastasis, or a new malignancy, this emphasizes the importance of ongoing follow-up and vigilant monitoring for higher-risk patients, to ensure timely identification of disease progression, complications of treatment, or new health issues [41,42].

The lack of association between ISUP grade and the probability of any RO visit in the first year of survivorship warrants discussion. This does not imply that RO disregards clinical grade; instead, it likely reflects the multi-factorial influence on early survivorship follow-up beyond ISUP grade alone, including PSA kinetics, treatment modality, and patient preference. The noted dose–response relationship between ISUP grade and overall rate of RO follow-up supports our assertion that RO appropriately maintains a higher frequency of follow-up for survivors with higher-grade disease, even if the specific timing of transition away from the cancer care system may be influenced by additional considerations beyond clinical risk. However, baseline characteristics were more similar between patients who received “de-intensified” follow-up care, compared to those who transitioned to GP-led care (no RO follow-up), suggesting there still may be survivors receiving ‘de-intensified’ care who are suitable candidates to transition exclusively to GP-led care during survivorship.

Strengths of our study included the use of a population-based cohort of prostate cancer survivors in Ontario, Canada spanning a decade, which included unique patient identifiers to facilitate data linkage across all healthcare sectors to elicit a complete picture of their care pathway. Additionally, we included key clinical indicators relevant to prostate cancer, including ISUP Grade, TNM stage, and PSA score. However, utilizing physician claims data limited our ability to definitively determine whether follow-up visits reflected routine survivorship care versus occurrence of cancer recurrence or metastasis, a new primary malignancy, or management of worsening symptoms and/or radiation-related toxicity. To mitigate misclassification of visits related to disease progression or active cancer care, we censored observation of participants who re-initiated radiation, dispensed hormones, received chemotherapy, or were diagnosed with a new primary malignancy. Furthermore, we included radiation-related complications as a covariate in our analysis to account for its role in radiation oncology follow-up throughout survivorship.

Our use of administrative healthcare databases limits our ability to account for other factors that could influence decision-making, such as patient and/or physician preferences, or financial, medical, or logistical factors [43,44,45,46,47]. In addition, because this study was conducted within Canada’s single-payer healthcare system, follow-up patterns may differ in jurisdictions with different access, care, and reimbursement models, which may hinder external validity. Finally, our study exclusively examined patients diagnosed with prostate cancer who underwent first-line radiation as a monotherapy and may not be generalizable to survivors treated with prostatectomy alone, prostatectomy followed by salvage radiation, or non-definitive management such as active surveillance or watchful waiting [48]. Radiation offers a non-surgical alternative for eligible patients [48] but entails a trade-off between clinical benefit [49] and post-radiotherapy complications [50] and may partly explain why some lower-risk survivors continue specialist follow-up longer than expected. Future work should explore survivorship care pathways of other primary modalities. Further, we suggest quantifying the real-world clinical effectiveness of transitioning (e.g., comparing risk of cancer-related adverse events among those under oncology- versus GP-led care), which in absence of a superior alternative, may promote GP-led care, especially among low-risk survivors.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our results suggest that higher-risk prostate cancer survivors are monitored more frequently by RO providers, consistent with clinical need. However, many lower-risk survivors continue to receive RO-led follow-up several years after completing treatment, indicating an opportunity to build risk-stratified survivorship pathways that support safe transitions to GP-led care. Such efforts may help alleviate pressure on cancer centres while ensuring appropriate monitoring and proximity for those who need continued oncology oversight.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/curroncol33010049/s1, Figure S1: Cohort exclusions; Figure S2: Kaplan-Meier curve for all-cause mortality; Table S1: Description of data sources; Table S2: Variable definitions; Table S3: Baseline characteristics by volume of radiation oncology follow-up during first year of survivorship (full version); Table S4: Multivariable model estimates for radiation oncology (RO) follow-up (full version).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.O.C., J.S., I.S.D. and H.S.; methodology, J.O.C., J.S., I.S.D., R.S. and H.S.; software, J.O.C.; validation, J.O.C.; formal analysis, J.O.C.; investigation, J.O.C.; resources, J.O.C. and H.S.; data curation, J.O.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.O.C.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, all authors; supervision, J.S., R.S., M.Z. and H.S.; project administration, J.O.C.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (approval code: #15712; approval date: 2 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was not required as our study relied exclusively on secondary data sources held securely at ICES. ICES is an independent, non-profit research institute whose legal status under Ontario’s health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyze health care and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While legal data sharing agreements between ICES and data providers (e.g., healthcare organizations and government) prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/das (email: das@ices.on.ca). The underlying analytic code is available from authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are, therefore, either inaccessible or may require modification.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by ICES (formerly Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). This study also used data adapted from the Statistics Canada Postal CodeOM Conversion File, which is based on data licensed from Canada Post Corporation, and/or data adapted from the Ontario MOH Postal Code Conversion File, which contains data copied under license from Canada Post Corporation© and Statistics Canada. We thank IQVIA Solutions Canada Inc. for use of their Drug Information File and Toronto Community Health Profiles Partnership for providing access to the Ontario Marginalization Index (ONMARG). Parts of these materials are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by CIHI, MOH, OH, and the Toronto Community Health Profiles Partnership. The analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources. No endorsement is intended or should be inferred.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee in collaboration with the Canadian Cancer Society; Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2021. Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. Available online: https://cdn.cancer.ca/-/media/files/research/cancer-statistics/2021-statistics/2021-pdf-en-final.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- LeBlanc, A.G.; Demers, A.; Shaw, A. Recent trends in prostate cancer in Canada. Health Rep. 2019, 30, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, F.; Bhindi, B.; Noonan, K.; Ong, M.; Castellano, K.; Kourkounakis, A.; Wallis, C.J.D. Assessment of the epidemiological trends for prostate cancer using administrative data in Ontario. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2023, 17, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahamyan, L.; Huszti, E.; Bremner, K.E.; Pechlivanoglou, P.; Mitsakakis, N.; Krahn, M. New Insights into the Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer in Ontario. Cancer Invest. 2019, 37, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerstein, M. Defining cancer survivorship. J. Cancer Surviv. 2007, 1, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.S.; Bhatia, S.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Reaman, G.H.; Tyne, C.; Wollins, D.S.; Hudson, M.M. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: Achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, V.; Harrison, M.; Cheng, H.; Kenfield, S.; Aggarwal, R.; Kwon, D.; McKay, R.; Hauger, R.; Hart, N.; Conzen, S.; et al. Improving research for prostate cancer survivorship: A statement from the Survivorship Research in Prostate Cancer (SuRECaP) working group. Urol. Oncol. 2020, 38, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denlinger, C.S.; Carlson, R.W.; Are, M.; Baker, K.S.; Davis, E.; Edge, S.B.; Friedman, D.L.; Goldman, M.; Jones, L.; King, A.; et al. Survivorship: Introduction and definition. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2014, 12, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, C.L. Cancer Survivorship. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2438–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, L.; Boorjian, S.A.; Briganti, A.; Klotz, L.; Mucci, L.; Resnick, M.J.; Rosario, D.J.; Skolarus, T.A.; Penson, D.F. Survivorship and improving quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2015, 68, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Green, A.; Ralph, N.; Newton, R.U.; Kneebone, A.; Frydenberg, M.; Chambers, S.K. Prostate cancer survivorship essentials framework: Guidelines for practitioners. BJU Int. 2021, 128, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skolarus, T.A.; Wolf, A.M.; Erb, N.L.; Brooks, D.D.; Rivers, B.M.; Underwood, W., 3rd; Salner, A.L.; Zelefsky, M.J.; Aragon-Ching, J.B.; Slovin, S.F.; et al. American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2014, 64, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhlyudov, L.; Greene, S.M.; Chubak, J.; Rabin, B.; Tuzzio, L.; Rolnick, S.; Field, T.S. Cancer research network: Using integrated healthcare delivery systems as platforms for cancer survivorship research. J. Cancer Surviv. 2013, 7, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, R.; Watson, E. The role of primary care in supporting patients living with and beyond cancer. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 12, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klabunde, C.N.; Ambs, A.; Keating, N.L.; He, Y.; Doucette, W.R.; Tisnado, D.; Clauser, S.; Kahn, K.L. The role of primary care physicians in cancer care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009, 24, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klabunde, C.N.; Han, P.K.; Earle, C.C.; Smith, T.; Ayanian, J.Z.; Lee, R.; Ambs, A.; Rowland, J.H.; Potosky, A.L. Physician roles in the cancer-related follow-up care of cancer survivors. Fam. Med. 2013, 45, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harrington, C.B.; Hansen, J.A.; Moskowitz, M.; Todd, B.L.; Feuerstein, M. It’s not over when it’s over: Long-term symptoms in cancer survivors—A systematic review. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2010, 40, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, S.D.; Birnie, S.E.; Marrett, L.D.; Taylor, S.M.; Reynolds, D.; Davies, J.; Drake, J.J.; Hayes, M. The geographic variation of cancer incidence in Ontario. Am. J. Public Health 1994, 84, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibhai, S.M.; Krahn, M.D.; Cohen, M.M.; Fleshner, N.E.; Tomlinson, G.A.; Naglie, G. Is there age bias in the treatment of localized prostate carcinoma? Cancer 2004, 100, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, J.; Cerasuolo, J.O.; Pond, G.R.; Bainbridge, D.; Seow, H. Patterns of Survivorship Follow-Up Care Among Patients With Breast Cancer: A Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study in Ontario, Canada, Between 2006 and 2016. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2025, 21, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquhart, R.; Lethbridge, L.; Porter, G.A. Patterns of cancer centre follow-up care for survivors of breast, colorectal, gynecologic, and prostate cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2017, 24, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquhart, R.; Lethbridge, L. Primary care use after cancer treatment: An analysis of linked administrative data. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27, e590–e595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birken, S.A.; Peluso, A.G.; Shalowitz, D.I.; Isom, S.; Wagi, C.R.; Randazzo, A.; Falk, D.; Strom, C.; Bell, R.; Weaver, K.E. Primary Care Provider Visits Among Cancer Survivors 5–7 Years Postdiagnosis. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2025, 21, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaorsky, N.G.; Sun, Y.; Nabid, A.; Zapatero, A.; Bolla, M.; Joseph, D.; Maingon, P.; Guerrero, A.; Gonzalez, A.A.; San-Segundo, C.G.; et al. Optimal Duration of Androgen Deprivation Therapy with Definitive Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Oncol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwis, N.D.M.; Oike, T.; Kubo, N.; Gondhowiardjo, S.A.; Ohno, T. Characteristics of PSA Bounce after Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2020, 12, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M.E.; Grunfeld, E.; Harvey, B.J.; Piliotis, E.; Verma, S. Primary care physicians’ views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 3338–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamdani, M.; Sykora, K.; Li, P.; Normand, S.L.; Streiner, D.L.; Austin, P.C.; Rochon, P.A.; Anderson, G.M. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 2005, 330, 960–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, K.F. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA 1998, 280, 1690–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alasia, A.; Bédard, F.; Bélanger, J.; Guimond, E.; Penney, C. Measuring Remoteness and Accessibility: A Set of Indices for Canadian Communities; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/18-001-X2017002 (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Matheson, F.I.; Dunn, J.R.; Smith, K.L.; Moineddin, R.; Glazier, R.H. Development of the Canadian Marginalization Index: A new tool for the study of inequality. Can. J. Public Health 2012, 103, S12–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Ingen, T.; Matheson, F.I. The 2011 and 2016 iterations of the Ontario Marginalization Index: Updates, consistency and a cross-sectional study of health outcome associations. Can. J. Public Health 2022, 113, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachaud, J.; Donnelly, P.D.; Henry, D.; Kornas, K.; Calzavara, A.; Bornbaum, C.; Rosella, L. A population-based study of homicide deaths in Ontario, Canada using linked death records. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. CIHI’s Population Grouping Methodology 1.4—Overview and Outputs. 2023. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/cihi-population-grouping-methodology-v1.4-overview-outputs-manual-en.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, A.L.; Rabin, J.; Horick, N.; Lei, Y.; Chinn, G.; Campbell, E.G.; Park, E.R.; Peppercorn, J. Practice, Preferences, and Practical Tips From Primary Care Physicians to Improve the Care of Cancer Survivors. J. Oncol. Pract. 2019, 15, e600–e606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasone, J.R.; Brouwers, M.C.; Vukmirovic, M.; Grunfeld, E.; O’Brien, M.A.; Urquhart, R.; Walker, M.; Webster, F.; Fitch, M. Interventions to improve care coordination between primary healthcare and oncology care providers: A systematic review. ESMO Open 2016, 1, e000077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, S.J.; Jacobsen, P.B. Cancer care coordination: Opportunities for healthcare delivery research. Behav. Med. 2018, 8, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.F.; Earle, C.C.; Herbert, R.J.; Neville, B.A.; Blackford, A.L.; Frick, K.D. Trends in follow-up and preventive care for colorectal cancer survivors. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, S.V.; Ohman-Strickland, P.A.; Bator, A.; O’Malley, D.; Gundersen, D.; Lee, H.S.; Crabtree, B.F.; Miller, S.M. Breast and prostate cancer survivors’ experiences of patient-centered cancer follow-up care from primary care physicians and oncologists. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016, 10, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earle, C.C.; Burstein, H.J.; Winer, E.P.; Weeks, J.C. Quality of non-breast cancer health maintenance among elderly breast cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 1447–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosain, R.; Miller, K. Symptoms and symptom management in long-term cancer survivors. Cancer J. 2013, 19, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Triano, L.R. Medical issues in cancer survivors--a review. Cancer J. 2008, 14, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernat, J.K.; Wittman, D.A.; Hawley, S.T.; Hamstra, D.A.; Helfand, A.M.; Haggstrom, D.A.; Darwish-Yassine, M.; Skolarus, T.A. Symptom burden and information needs in prostate cancer survivors: A case for tailored long-term survivorship care. BJU Int. 2016, 118, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.H. Tailored prostate cancer survivorship: One size does not fit all. BJU Int. 2016, 118, 343–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, K.H.; Raskin, S.; Willis, A.; Arem, H.; Murtaza, S.; Charney, L.; Pratt-Chapman, M. Identifying patients’ priorities for quality survivorship: Conceptualizing a patient-centered approach to survivorship care. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 939–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.Y.; Neville, B.A.; Cameron, D.B.; Cook, E.F.; Earle, C.C. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 2489–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.Y.; Aziz, N.; Noone, A.M.; Rowland, J.H.; Potosky, A.L.; Ayanian, J.Z.; Virgo, K.S.; Ganz, P.A.; Stefanek, M.; Earle, C.C. Physician preferences and attitudes regarding different models of cancer survivorship care: A comparison of primary care providers and oncologists. J. Cancer Surviv. 2013, 7, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancee, M.; Tikkinen, K.A.O.; De Reijke, T.M.; Kataja, V.V.; Aben, K.K.H.; Vernooij, R.W.M. Guideline of guidelines: Primary monotherapies for localised or locally advanced prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2018, 122, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, F.C.; Donovan, J.L.; Lane, J.A.; Mason, M.; Metcalfe, C.; Holding, P.; Davis, M.; Peters, T.J.; Turner, E.L.; Martin, R.M.; et al. 10-Year Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, R.K.; Cheung, P.; Herschorn, S.; Saskin, R.; Su, J.; Klotz, L.H.; Chang, M.; Kulkarni, G.S.; Lee, Y.; Kodama, R.T.; et al. Incidence of complications other than urinary incontinence or erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: A population-based cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.