Simple Summary

Thyroid cancer rates are increasing worldwide, and having family members with thyroid cancer may raise a person’s risk of developing the disease. While it is known that family history is important, we did not know exactly how much risk was linked to different types of family relationships or whether it varied by country. In this study, we reviewed and combined data from published studies to see how a family history of thyroid cancer affects risk. We found that people with affected family members, especially siblings, are much more likely to develop thyroid cancer themselves. The risk was similar whether the family history came from the mother or father, and differences between countries were not significant. These results suggest that people with a family history of thyroid cancer may benefit from earlier or more frequent health checks, which could help with early detection and better outcomes.

Abstract

The increasing global incidence of thyroid cancer highlights the importance of accurately assessing risk factors, particularly those related to family history. Although having affected family members is widely recognized as a risk factor for thyroid cancer, the exact degree of risk and its variation across types of familial relationships, parental gender, and geographic regions remain unclear. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to clarify the association between family history and thyroid cancer risk. We conducted a comprehensive literature search of PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase following PRISMA guidelines, identifying 13 studies from 503 initially screened. Statistical analyses were performed using random-effects models to estimate pooled odds ratios and risk ratios, with subgroup analyses to assess variations across population and relationship types. Our findings showed an approximately 4.5-fold higher risk of thyroid cancer in individuals with affected family members. Individuals with affected siblings were more likely to develop thyroid cancer while the risks associated with maternal and paternal family history were comparable in magnitude, with no statistical difference between them. Socioeconomic, educational, and lifestyle differences did not significantly influence risk, and geographic variations in familial risk could not be statistically confirmed by the subgroup analysis, in the context of high between-study heterogeneity. These results suggest that family history is a substantial risk factor for thyroid cancer, reinforcing the need for enhanced surveillance and screening strategies for those with a familial predisposition.

1. Introduction

Thyroid cancer has emerged as a significant global health concern, representing one of the most prominent and rapidly increasing cancer diagnoses worldwide [1,2]. According to recent World Health Organization estimates, the global burden reached 821,214 new cases in 2022, with an age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) of 9.1 per 100,000 people [3,4], reflecting a substantial public health challenge that spans diverse geographic and demographic boundaries. This rising incidence pattern, however, presents a complex epidemiological picture, with some regions showing continued increases. In contrast, others, notably the United States, have demonstrated a modest decline of approximately 2% annually since 2014—a trend largely attributed to the implementation of more stringent diagnostic criteria [5].

Advancements in medical imaging technologies, such as high-resolution ultrasonography and advanced cross-sectional imaging, have fundamentally altered the landscape of thyroid cancer detection [6,7]. However, this technological progress has introduced new challenges in distinguishing clinically significant malignancies from incidental findings, necessitating a more nuanced understanding of risk factors to guide screening and diagnostic protocols [7,8]. Within this context, the role of hereditary factors has gained increasing prominence [9], although their precise contribution to disease risk remains incompletely characterized.

Current evidence has established several well-documented risk factors for thyroid cancer, including exposure to ionizing radiation, female sex, and iodine deficiency [10,11,12,13]. Additionally, specific genetic syndromes, such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2), familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), and Cowden syndrome, have been clearly associated with thyroid malignancy [14]. However, the broader implications of family history, particularly in cases without identified genetic syndromes, are less well understood across different populations and familial relationships.

Recent investigations have suggested that family history may exert a more substantial influence on both disease risk and progression than previously recognized [15]. While several studies have documented associations between family history and more aggressive disease phenotypes, the relationship between familial patterns and thyroid cancer development has not been systematically evaluated across diverse populations and varying degrees of familial relationships [16,17,18]. This knowledge gap is particularly noteworthy given the potential implications for risk stratification and clinical management strategies.

The present study addresses these critical questions through a comprehensive meta-analysis of the available evidence. Our investigation specifically examines (1) the quantitative relationship between family history and thyroid cancer risk, (2) potential variations in risk based on the degree of familial relationship, (3) the differential impact of maternal versus paternal history, and (4) geographic variations in familial risk patterns. By synthesizing data from diverse study populations, this analysis provides crucial insights into the heritable aspects of thyroid cancer risk and implications for developing risk assessment protocols and optimizing surveillance strategies for high-risk populations. Furthermore, our findings contribute to a broader understanding of thyroid cancer etiology, potentially informing future research on both genetic and environmental risk factors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Search Strategy

This study was developed and accomplished in accordance with the most recent Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [19]. The registration number of the related protocol is “INPLASY202560025” (https://inplasy.com/). A systematic literature search across PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase was conducted on 17 August 2024, to identify the extent of peer-reviewed literature on demographic and lifestyle factors related to the heritable risk of developing thyroid cancer. To collect as many relevant studies as possible, a broad search was conducted utilizing only the following search terms: ((Lifestyle) OR (Genetics) OR (Epigenetics) OR (Benign Thyroid Conditions)) AND (Family History) AND (Thyroid Cancer).

2.2. Study Selection

The articles retrieved from these databases were screened against the inclusion criteria. Articles included in the study were those that described (i) a study cohort containing patients with a family history of thyroid cancer, (ii) both a group of patients without thyroid cancer and a group of patients with thyroid cancer, and (iii) reported relevant outcomes of interest. Outcomes of interest included demographic characteristics (age, sex, income, education, marital status), lifestyle factors (body mass index (BMI), alcohol consumption, smoking status, previous radiation exposure, benign thyroid conditions), and information on family members with thyroid cancer (father, mother, parent, sibling, child, 1st degree relative, other relative). Studies were excluded if they were not peer-reviewed and were designed as case reports/series, letters to the editor, editorial comments, reviews, meta-analyses, or written in a non-English language. Additionally, studies that lacked either a non-thyroid cancer group or evidence of family history of thyroid cancer were marked as ineligible. All articles underwent an initial screening based solely on title and abstract, followed by full-text review.

2.3. Data Extraction

All articles that were found to be eligible based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria proceeded to data extraction. Two independent investigators each independently extracted the outcomes of interest (N.M., M.B.L.). The extracted data was verified by a third investigator (A.S.). No automation tools were used at any point. Primary outcomes of interest were demographic characteristics, such as age and sex distribution of the study population, and the relationship between patients with/without thyroid cancer and the relative who was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. Other demographic characteristics (income, education, marital status) and lifestyle factors (BMI, alcohol consumption, smoking status, previous radiation exposure) were also included. Benign thyroid conditions, including goiter, benign thyroid nodules, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism, were also accounted for as secondary outcomes of interest.

Age-stratified analyses were conducted to evaluate differences in familial risk among early-onset and later-onset thyroid cancer cases. We used <45 years old as the cutoff for early-onset, as this threshold has been widely applied in previous epidemiological studies and was used in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system [20,21].

Income level was categorized into low, middle, and high using the original categories from each study, reflecting each region’s census or index-based classification rather than a standardized global theme.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All data analyses were performed using RStudio Build (version 2024.09). A single-arm meta-analysis was performed for demographic characteristics to generate pooled estimates of mean raw data (MRAW) or untransformed proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported for the estimated pooled results from studies. For pairwise comparisons, estimates of mean difference served as quantitative measures of the strength of evidence, which were then converted to odds ratios (ORs) or relative risks (RRs) with 95% CIs for better interpretation within clinical domains. Given the inherent diversity in study populations, geographic locations, and study designs spanning several decades, a random-effects model was selected. Sub-analyses were conducted that incorporated geographic variation, degree of relatedness, and the differential impact of maternal vs. paternal family history. Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot and Egger’s test. The Mantel-Haenszel and DerSimonian-Laird estimators were employed to calculate chi-square values and to adjust for heterogeneity. The p-value threshold for rejecting the null hypothesis was set at p < 0.05.

This manuscript was edited for clarity and readability using the Claude GenAI tool (Anthropic) and Grammarly. All scientific ideas, methodology, data collection, analysis, and interpretation were performed entirely by the authors.

3. Results

3.1. Eligible Studies

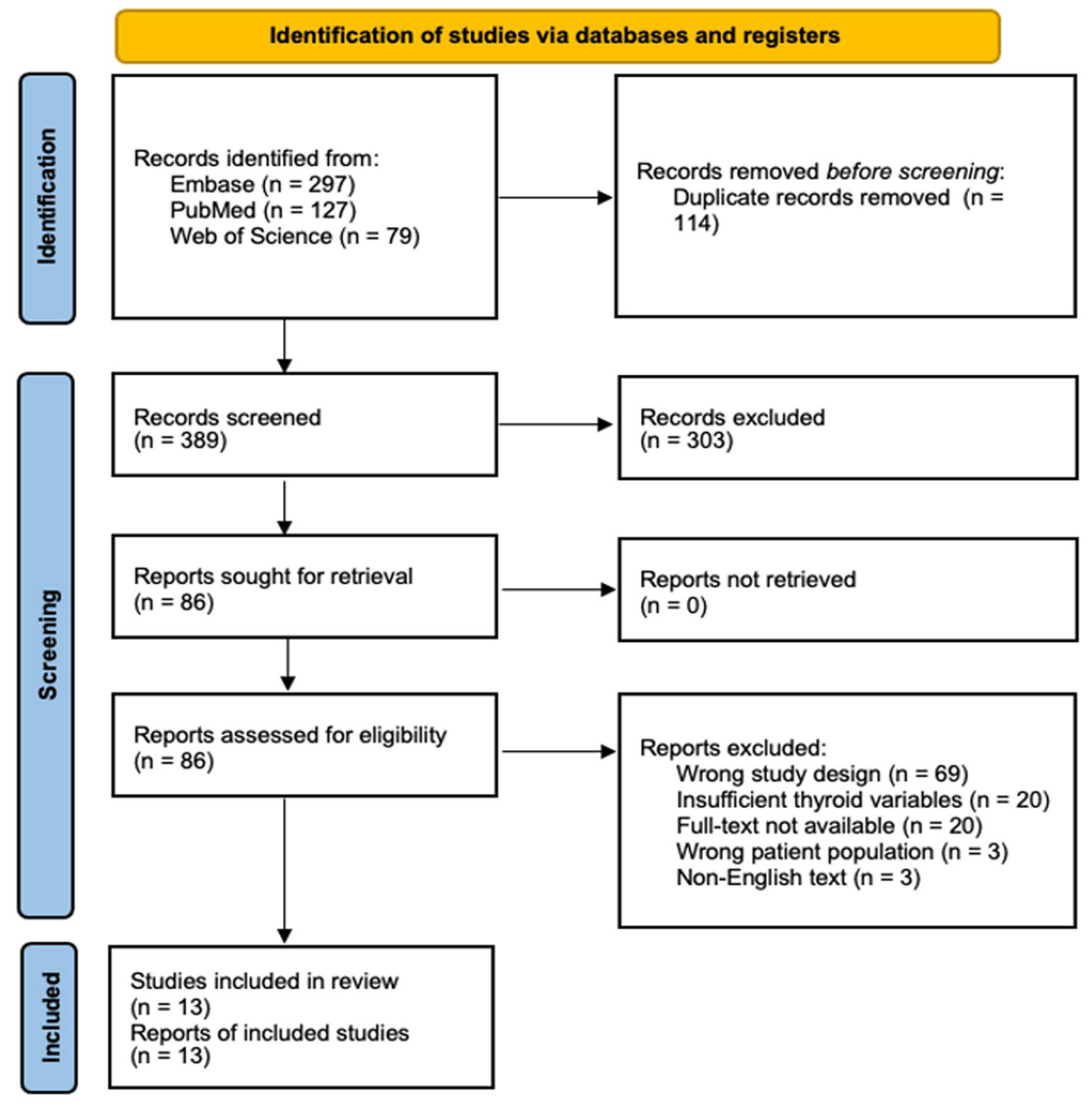

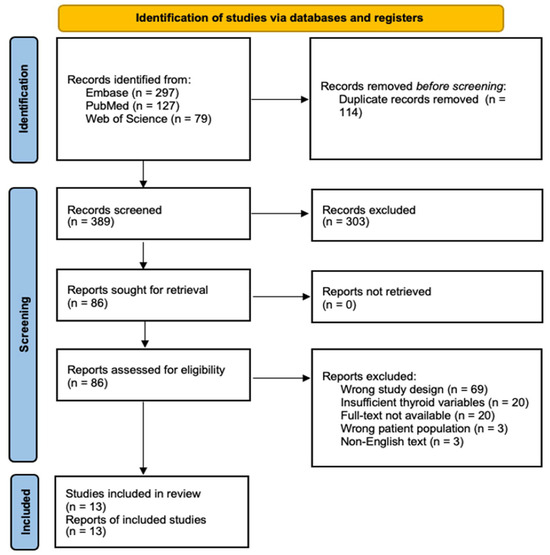

Our systematic literature search initially identified 503 potentially relevant studies across 3 major databases (PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase). Following duplicate removal (n = 114) and screening against inclusion criteria, 13 studies met the eligibility requirements for quantitative synthesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Study Selection Process. Systematic search and selection process following PRISMA guidelines. An initial database search yielded 503 records, of which 13 studies met the final inclusion criteria after duplicate removal, screening, and eligibility assessment.

The included studies comprised 11 case-control and 2 cross-sectional designs, spanning three decades (1987–2021) and four geographic regions (Asia, America, Europe, and Oceania). The cumulative sample size included 5398 thyroid cancer cases and 204,639 controls, with individual study populations ranging from 293 to 200,576 participants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

3.2. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2.1. Age Distribution

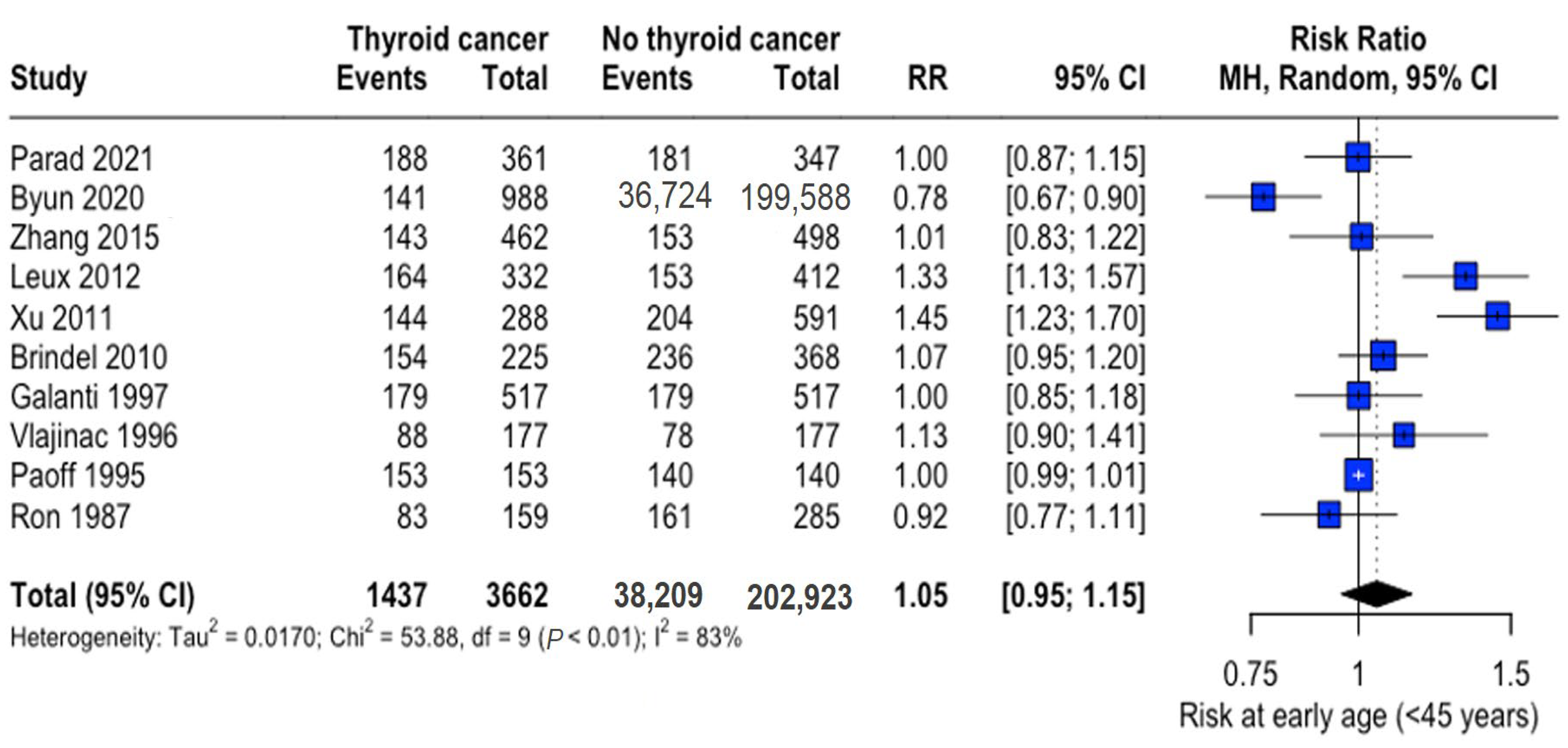

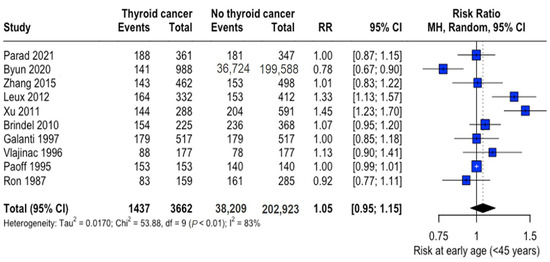

The mean age range was 29.3–53.2 years (thyroid cancer group) and 29.6–54.2 years (control group), with thyroid cancer patients being marginally younger overall (mean difference: -3.10 years, 95% CI: −6.15 to −0.05). Analysis of early-onset cases (<45 years) revealed no significant difference in risk (RR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.95–1.15) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Age-related risk of thyroid cancer. Forest plot showing relative risk (RR) of thyroid cancer in early-onset (<45 years) versus later-onset cases. Central diamonds represent pooled estimates; horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals [22,23,25,26,27,28,31,32,33,34].

3.2.2. Sex Distribution

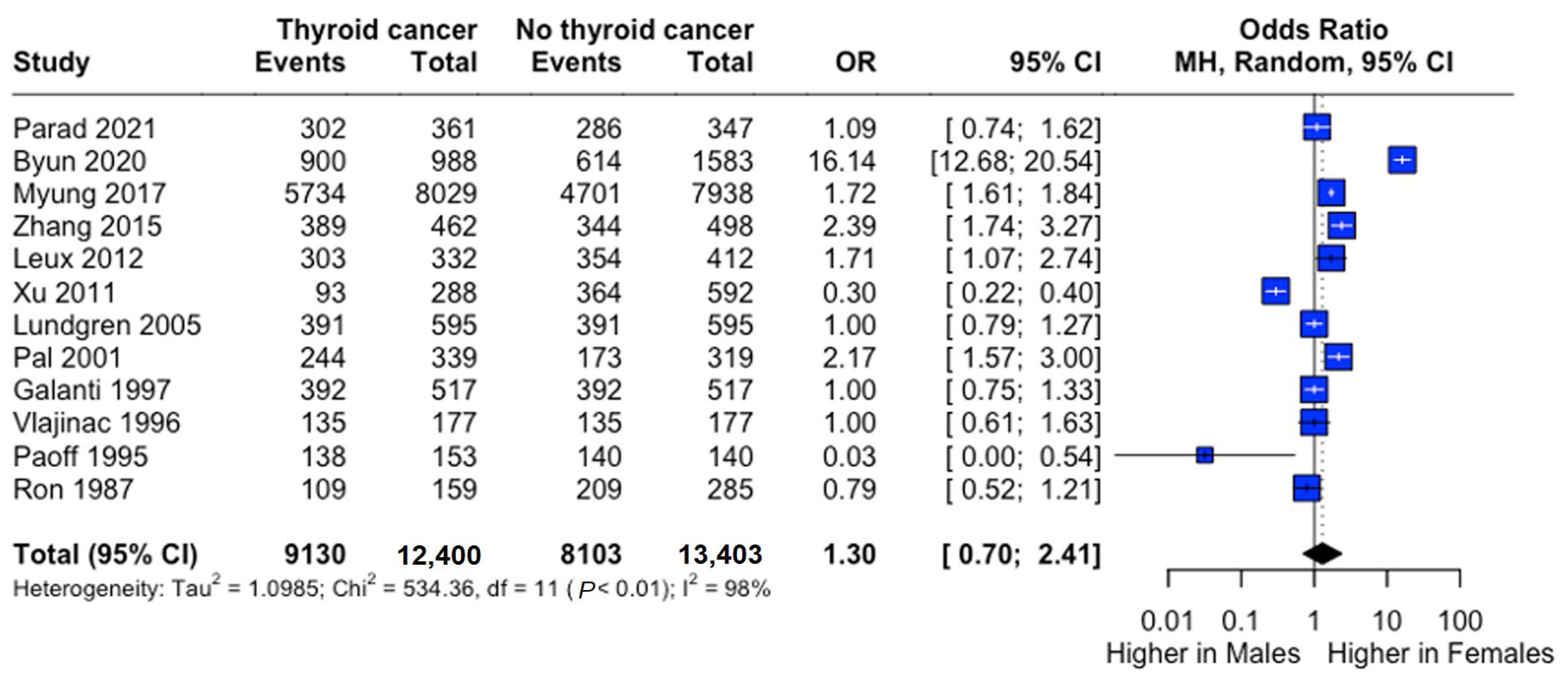

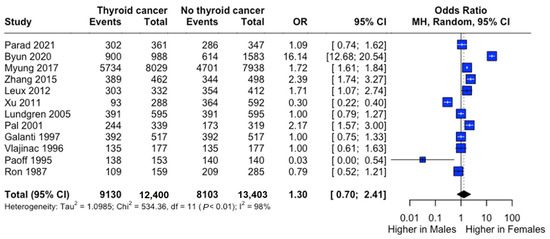

Female predominance was observed in both groups (thyroid cancer: 73.9%; controls: 61.9%). Males demonstrated significantly lower risk (RR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.55–0.98), though odds ratio analysis suggested a non-significant trend toward higher female risk (OR: 1.30, 95% CI: 0.70–2.41) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sex-specific risk of thyroid cancer. Forest plot comparing thyroid cancer risk between males and females. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals are shown. Central diamonds represent pooled estimates; horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals [22,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,34].

3.2.3. Socioeconomic Factors

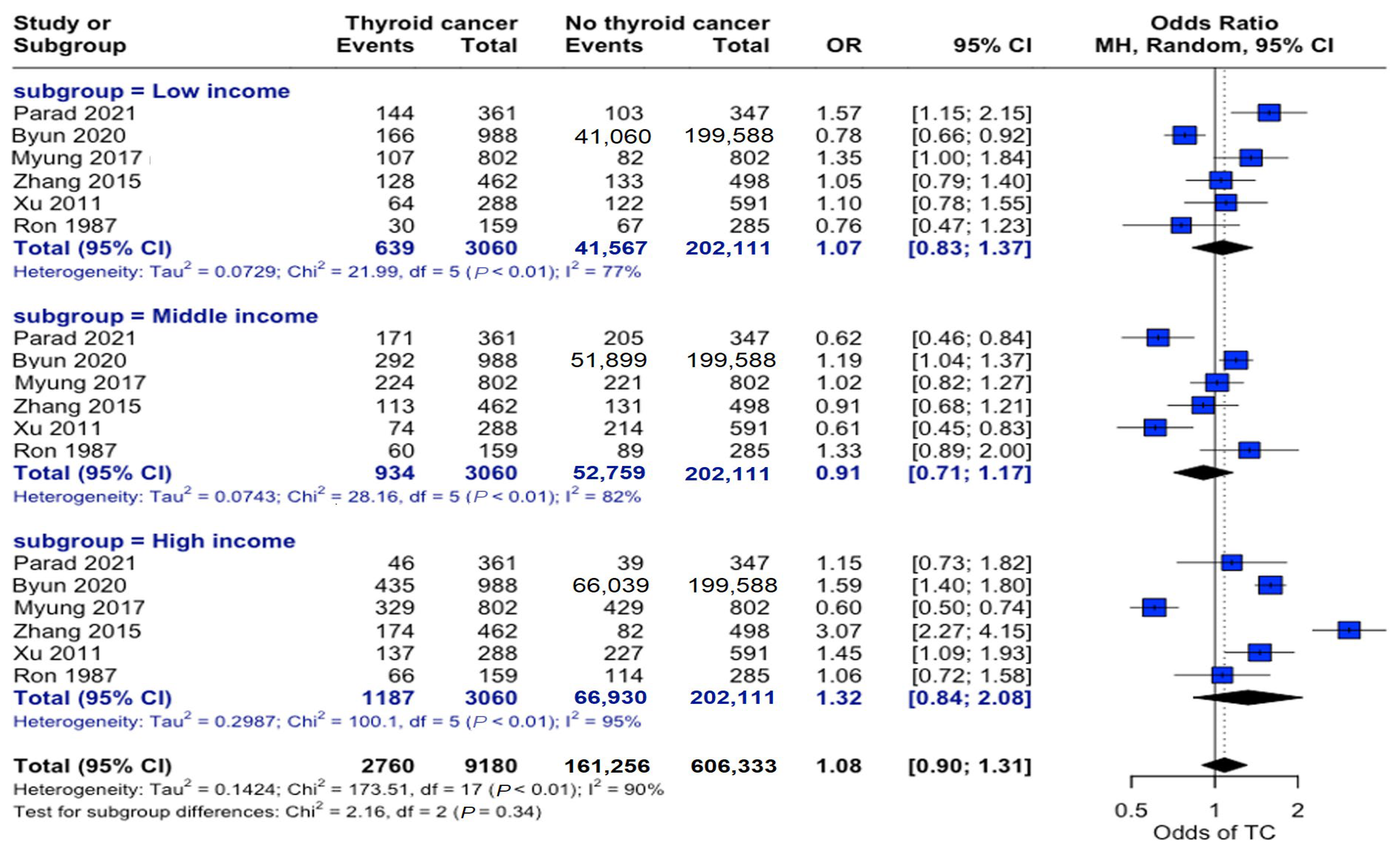

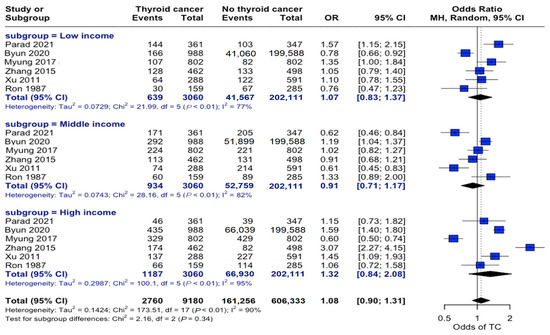

Analysis across income strata revealed no significant associations. Low-income (OR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.83–1.37), middle-income (OR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.71–1.17), and high-income (OR: 1.32, 95% CI: 0.84–2.08) individuals showed no differential association in propensity to develop this disease (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Income-stratified risk analysis. Forest plot showing odds ratios for thyroid cancer risk across three income categories. Horizontal lines represent odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Categorizing individuals by income level did not demonstrate a significant relationship between socioeconomic status and thyroid cancer risk [22,23,24,25,27,34].

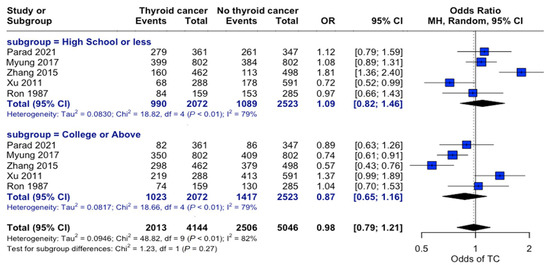

Examining education levels in thyroid cancer showed no significant overall association between education level and thyroid cancer risk (OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.79–1.21). When individuals were grouped by “High School or Less” and “College or Above” education levels, there were no significant differences in the odds of developing thyroid cancer across the strata (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Education-related risk analysis. Forest plot comparing thyroid cancer risk stratified by educational attainment. Horizontal lines represent the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals. There was no significant association between education level and thyroid cancer risk (OR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.79–1.21) [22,24,25,27,34].

3.2.4. Marital Status

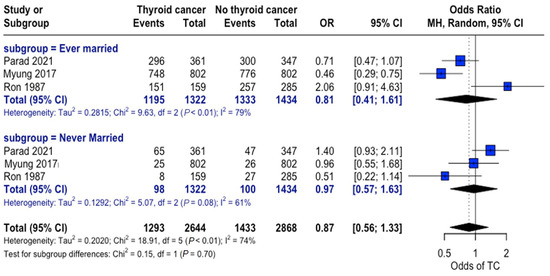

When grouped by marital status (ever married vs. never married), a higher proportion of individuals were found to be married in both the thyroid cancer and control groups. Nonetheless, no consistent significant differences were observed between the thyroid cancer and no thyroid cancer groups across studies, and no significant overall association was observed between marital status and thyroid cancer risk (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Marital status and thyroid cancer risk. Forest plot showing odds of developing thyroid cancer based on an individual’s marital status for the thyroid cancer and control groups [22,24,34].

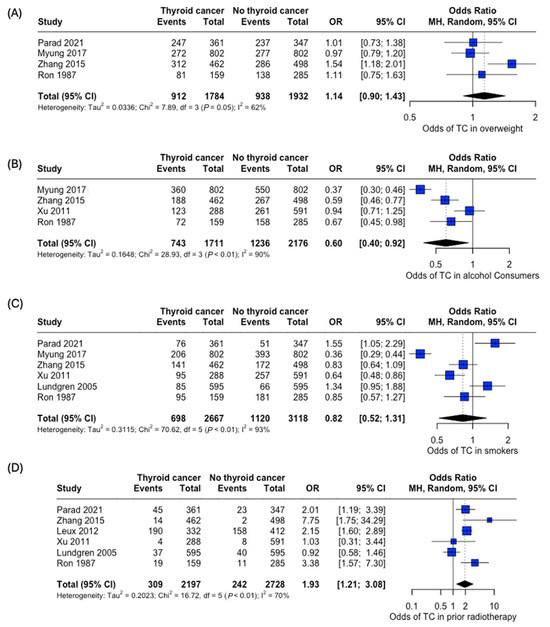

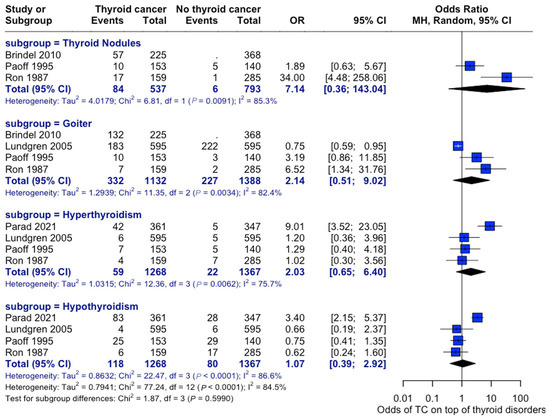

3.3. Lifestyle and Thyroid-Related Comorbidities

An analysis of the risk of developing thyroid cancer demonstrated no significant difference in terms of association with comorbidities. When collected, data on overweight status (OR: 1.14, 95% CI: 0.90–1.43), alcohol consumption (OR: 0.60, 95% CI:0.40–0.92), and smoking habits (OR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.52–1.31) were all insignificant, while the case for prior radiotherapy was identified to be statistically significant (OR: 1.93, 95% CI: 1.21–3.08) (Figure 7). Patient history of other thyroid-related conditions or disorders showed no link with the development of thyroid cancer (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Odds of developing thyroid cancer based on lifestyle factors and comorbidities. Odds of thyroid cancer in (A) Overweight, (B) Alcohol consumers, (C) Smokers, and (D) Patients with prior radiotherapy [22,24,25,26,27,29,34].

Figure 8.

Thyroid-Related Disorders and Cancer Risk. Forest plot showing associations between pre-existing thyroid conditions and subsequent cancer risk—analysis stratified by condition type [22,28,29,33,34].

3.4. Association Between Family History of Thyroid Cancer and Thyroid Cancer Risk

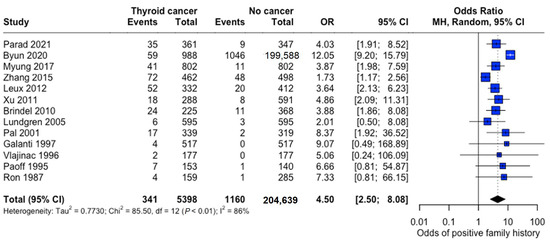

3.4.1. Overall Analysis

Family history demonstrated a strong association with thyroid cancer risk (pooled OR: 4.50, 95% CI: 2.50–8.08), indicating substantially 4.5 times higher odds among individuals with affected family members (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Overall Family History Association. Forest plot showing pooled and study-specific odds ratios for thyroid cancer risk associated with positive family history. A random-effects model was used due to significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50%) [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

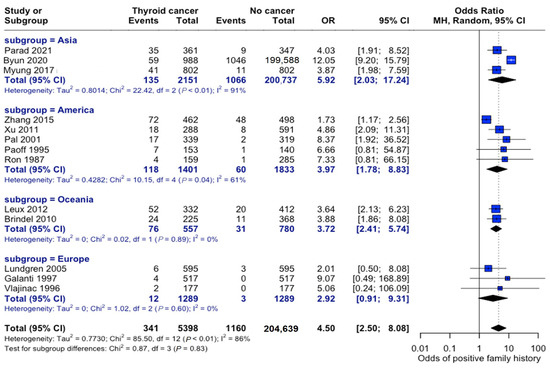

3.4.2. Geographic Variations

The association between family history and thyroid cancer risk varied across different geographic regions. Studies originating in Asia consisted of study populations that were nearly six times more likely to develop thyroid cancer if a family history of thyroid cancer was present (OR: 5.92, 95% CI: 2.03–17.24). Studies conducted in Europe showed the weakest association between these variables (OR: 2.92, 95% CI: 0.91–9.31), although patients were still roughly three times more likely to develop thyroid cancer if they had a family member diagnosed with thyroid cancer. The test for subgroup differences by continent was not statistically significant; however, overall heterogeneity in the meta--analysis was high (I2 = 83%), indicating that true effect sizes likely vary across studies. Thus, geographic variation could not be statistically confirmed by this subgroup analysis, which may have been underpowered to detect modest regional differences or other unmeasured sources of variability (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Geographic variation in family history risk. Forest plot showing odds ratios stratified by geographic region. Markers’ sizes are proportional to study weight; heterogeneity statistics are provided for each [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

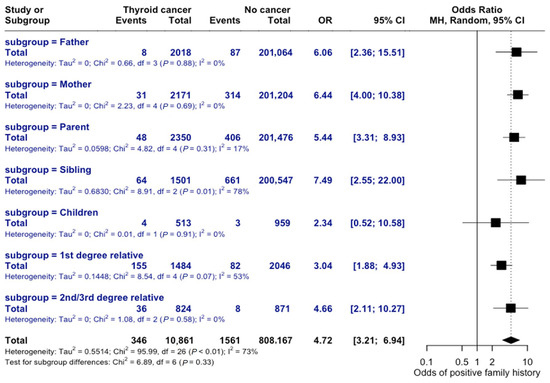

3.4.3. Degree of Relatedness

The risk of thyroid cancer varies based on the degree of relatedness in family history. If the relative was previously diagnosed with thyroid cancer, the odds of an individual developing thyroid cancer were 6 times greater than those without a family history (OR = 6.06, 95% CI = 2.37–15.51). A family history due to a child’s diagnosis resulted in the lowest familial odds of developing thyroid cancer, OR = 2.34 (95% CI = 0.52–10.58), while family history through siblings with prior thyroid cancer diagnosis had the greatest association (OR = 7.49, 95% CI = 2.55–22.0), as seen in Figure 11. The test for subgroup differences was not statistically significant, suggesting that the observed differences in risk by degree of relatedness may not be statistically meaningful.

Figure 11.

Risk by Degree of Relatedness. Forest plot comparing odds ratios across different familial relationships. Subgroup analysis shows non-significant differences (p = 0.33).

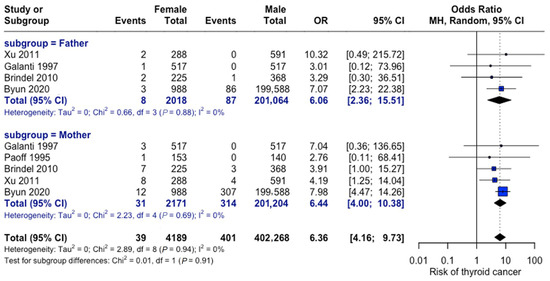

3.4.4. Differential Impact of Paternal vs. Maternal Family History

As depicted in Figure 12, maternal versus paternal history showed comparable risks. The odds of thyroid cancer were six-fold in patients with a positive family history attributable to the mother (OR = 6.44, 95% CI: 4.0–10.38) and the father (OR = 6.06, 95% CI: 2.37–15.51). No significant difference was observed between parental effects.

Figure 12.

Parental history comparison. Forest plot comparing maternal versus paternal family history effects. Analysis shows consistent findings across studies for both parental categories [23,27,28,31,33].

4. Discussion

This comprehensive meta-analysis provides novel insights into the relationship between family history and thyroid cancer risk across diverse populations and familial relationships. Most notably, individuals with a family history of thyroid cancer demonstrated approximately 4.5-fold higher risk compared to those without such a history. This magnitude of excess risk is broadly consistent with large registry-based and case–control studies that have reported substantially elevated risks of thyroid cancer among first-degree relatives, while our review extends this evidence by formally synthesizing estimates across continents and by relationship type. This association persisted across geographic regions and familial relationships, with sibling history conferring the highest risk, followed by parental history. The comparable risks observed between maternal and paternal history suggest that genetic factors may play a more significant role than parent-specific environmental, epigenetic, or lifestyle influences [35].

A previous European cohort study focused exclusively on lifestyle factors, such as diet, exercise, smoking, and alcohol use, as contributors to thyroid cancer [36]. However, the relative risks of family history presented in this work highlight that the isolated contribution of heritable genetic risk still strongly outweighs the risks of factors that can be modified through lifestyle improvements.

The elevated familial risks observed in our meta-analysis align with growing evidence that a subset of non-medullary thyroid cancers arises on a hereditary background [37]. Familial non-medullary thyroid carcinoma is estimated to account for approximately 3–9% of all thyroid cancer cases [38]. It appears to follow an autosomal dominant pattern with incomplete penetrance and substantial genetic heterogeneity. Several studies have implicated germline variants and susceptibility loci in genes involved in DNA damage response and other pathways (for example, CHEK2, ATM, BRCA2, and additional candidate predisposition genes identified by next-generation sequencing), although no single high-penetrance gene has been established as the predominant driver of familial non-medullary thyroid cancer [39,40,41,42]. It is important to note that the primary studies included in this meta-analysis did not report individual-level germline genetic data; therefore, the genetic aspects discussed here draw on external literature and cannot be directly evaluated within our dataset.

The observed geographic variations in risk, though not statistically significant, merit careful consideration in the context of healthcare accessibility and screening practices. Asian populations demonstrated the strongest familial associations, while European cohorts showed more modest effects. These differences may reflect variations in genetic backgrounds, environmental exposures, or healthcare system characteristics rather than true biological differences in familial risk. The similar risk levels for maternal and paternal histories suggest that screening recommendations should not differ by parental gender. However, healthcare providers should consider the cumulative impact of multiple affected family members when assessing individual risk.

These findings have important implications for clinical practice, particularly regarding risk assessment and surveillance strategies. Family history should be an essential component of thyroid cancer risk evaluation, with careful documentation of the degree of relatedness before further diagnostic workup. Enhanced screening protocols may be warranted for individuals with affected first-degree relatives, though such recommendations must account for regional variations in healthcare accessibility. The availability and cost of genetic testing may influence risk assessment strategies, particularly in rural and underserved populations, where access to specialized healthcare services may be limited.

Several methodological aspects warrant consideration when interpreting these results. The predominance of retrospective designs limits causal inference, while the temporal scope spans significant advances in diagnostic capabilities. The relatively small sample sizes in some subgroup analyses led to wide confidence intervals, particularly in the paternal history subgroup. The geographic distribution of studies may not fully represent global population diversity, and potential recall bias in self-reported family histories must be acknowledged. However, the consistency of findings across studies, as shown in the cross-sectional analysis where expert clinicians verified family history, supports the reliability of our conclusions.

These limitations suggest several priority areas for future research. Prospective cohort studies are needed to validate risk estimates and investigate age-specific risk patterns. In such studies, a detailed account of TC histopathological subtype could further inform the role of family history in TC risk. A more detailed analysis of genetic-environmental interactions could help elucidate the mechanisms underlying familial risk transmission, particularly for specific genetic variants and environmental modifiers. Additionally, research examining the effectiveness and cost-efficiency of risk-based screening protocols could inform the development of more targeted surveillance strategies.

The robust association between familial history and thyroid cancer risk emphasizes the necessity of incorporating thyroid cancer-specific family history into routine clinical evaluations. Comprehensive risk assessment protocols can facilitate early diagnosis and intervention, ultimately improving patient outcomes. Future work should focus on understanding geographic trends by examining patient cohorts with greater regional variation, particularly regarding factors influencing healthcare accessibility and the availability of genetic testing.

Taken together, these findings reinforce the need for clinical guidelines and public health policies that explicitly incorporate detailed family history into risk-stratification algorithms while avoiding over-screening in lower-risk groups. Future research should integrate detailed familial data with germline genetic testing, environmental exposure assessment, and health--system variables to clarify mechanisms of familial aggregation and to evaluate the cost--effectiveness and equity impacts of risk--adapted screening strategies across regions.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this meta-analysis support the need for enhanced surveillance among individuals with a family history of thyroid cancer, regardless of whether the affected relative is maternal or paternal. The consistent association observed across diverse populations suggests that genetic factors are central to disease risk. However, further research is warranted to clarify the influence of environmental and healthcare system factors. Introducing routine screening protocols for families at risk may help achieve earlier diagnosis and improve patient outcomes, especially if coupled with broader access to genetic counseling and specialized healthcare services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.L., N.J.M., M.S.F. and E.A.T.; methodology, M.B.L., N.J.M., A.S., M.S.F. and E.A.T.; formal analysis, M.B.L., N.J.M. and A.S.; investigation (study screening and data extraction), M.B.L., N.J.M., A.S., E.O.A., B.A.A. and M.M.I.; data curation, M.B.L., N.J.M. and A.S.; resources, E.O.A., B.A.A., M.M.I. and M.S.F.; validation, E.O.A., B.A.A., M.M.I., M.S.F. and E.A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.L., N.J.M. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, E.O.A., B.A.A., M.M.I., M.S.F. and E.A.T.; visualization, M.B.L. and N.J.M.; supervision, M.S.F. and E.A.T.; project administration, M.S.F. and E.A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to Northern Border University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (NBU-CRP-2025-1442) and Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting project number (PNURSP2025R777), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data were sourced from previously published articles.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the authors used Claude GenAI (Anthropic, www.claude.ai) for text enhancement and Grammarly (Grammarly Inc., www.grammarly.com) to assist with grammar and style revision. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASIR | Age-standardized incidence rate |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| FAP | Familial adenomatous polyposis |

| MEN2 | Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RR | Relative risk |

| TC | Thyroid cancer |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Franceschi, S.; Dal Maso, L.; Vaccarella, S. Thyroid cancer “epidemic” also occurs in low- and middle-income countries. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 2082–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, B.; Tan, D.J.H.; Ng, C.H.; Fu, C.E.; Lim, W.H.; Zeng, R.W.; Yong, J.N.; Koh, J.H.; Syn, N.; Meng, W.; et al. Patterns in Cancer Incidence Among People Younger Than 50 Years in the US, 2010 to 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2328171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Laversanne, M.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory. International agency for Research on Cancer. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Thyroid Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/thyroid-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Bhattacharya, S.; Mahato, R.; Singh, S.; Bhatti, G.K.; Mastana, S.S.; Bhatti, J.S. Advances and challenges in thyroid cancer: The interplay of genetic modulators, targeted therapies, and AI-driven approaches. Life Sci. 2023, 332, 122110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habchi, Y.; Himeur, Y.; Kheddar, H.; Boukabou, A.; Atalla, S.; Chouchane, A.; Ouamane, A.; Mansoor, W. AI in Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis: Techniques, Trends, and Future Directions. Systems 2023, 11, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, N.; Mohanty, A.; Basu, S.; D’Cruz, A.K. Comprehensive Review of the Imaging Recommendations for Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Thyroid Carcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balinisteanu, I.; Panzaru, M.; Caba, L.; Ungureanu, M.C.; Florea, A.; Grigore, A.M.; Gorduza, E.V. Cancer Predisposition Syndromes and Thyroid Cancer: Keys for a Short Two-Way Street. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, M.L.; Schmidt, A.; Ghuzlan, A.A.; Lacroix, L.; Vathaire, F.; Chevillard, S.; Schlumberger, M. Radiation exposure and thyroid cancer: A review. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 61, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenko, V.; Mitsutake, N. Radiation-Related Thyroid Cancer. Endocr. Rev. 2024, 45, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Mueller, L.; Issa, P.P.; Haidari, M.; Trinh, L.; Toraih, E.; Kandil, E. Sexual disparity and the risk of second primary thyroid cancer: A paradox. Gland Surg. 2023, 12, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozd, V.; Branovan, D.; Reiners, C. Increasing Incidence of Thyroid Carcinoma: Risk Factors and Seeking Approaches for Primary Prevention. Int. J. Thyroidol. 2020, 13, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Risk Factors for Thyroid Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/thyroid-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Bylstra, Y.; Lim, W.K.; Kam, S.; Tham, K.W.; Wu, R.R.; Teo, J.X.; Davila, S.; Kuan, J.L.; Chan, S.H.; Bertin, N.; et al. Family history assessment significantly enhances delivery of precision medicine in the genomics era. Genome Med. 2021, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.-j.; Han, Z.-j.; Hu, Y.-x.; Zhang, N.; Huang, T. Family history of malignant or benign thyroid tumors: Implications for surgical procedure management and disease-free survival. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1282088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazeh, H.; Benavidez, J.; Poehls, J.L.; Youngwirth, L.; Chen, H.; Sippel, R.S. In Patients with Thyroid Cancer of Follicular Cell Origin, a Family History of Nonmedullary Thyroid Cancer in One First-Degree Relative Is Associated with More Aggressive Disease. Thyroid 2012, 22, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Lakis, M.; Giannakou, A.; Nockel, P.J.; Wiseman, D.; Gara, S.K.; Patel, D.; Sater, Z.A.; Kushchayeva, Y.Y.; Klubo-Gwiezdzinska, J.; Nilubol, N.; et al. Do patients with familial nonmedullary thyroid cancer present with more aggressive disease? Implications for initial surgical treatment. Surgery 2019, 165, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, I.D.; Thompson, G.B.; Grant, C.S.; Bergstralh, E.J.; Dvorak, C.E.; Gorman, C.A.; Maurer, M.S.; McIver, B.; Mullan, B.P.; Oberg, A.L.; et al. Papillary thyroid carcinoma managed at the Mayo Clinic during six decades (1940–1999): Temporal trends in initial therapy and long-term outcome in 2444 consecutively treated patients. World J. Surg. 2002, 26, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Edge, S.B.; Greene, F.L.; Byrd, D.R.; Brookland, R.K.; Washington, M.K.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Compton, C.C.; Hess, K.R.; Sullivan, D.C. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 1024. [Google Scholar]

- Parad, M.T.; Fararouei, M.; Mirahmadizadeh, A.R.; Afrashteh, S. Thyroid cancer and its associated factors: A population-based case-control study. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.H.; Min, C.; Choi, H.G.; Hong, S.J. Association between Family Histories of Thyroid Cancer and Thyroid Cancer Incidence: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study Data. Genes 2020, 11, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, S.K.; Lee, C.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.S. Risk Factors for Thyroid Cancer: A Hospital-Based Case-Control Study in Korean Adults. Cancer Res. Treat. 2017, 49, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, H.; Sandler, J.; Dai, M.; Ma, S.; Udelsman, R. Diagnostic radiography exposure increases the risk for thyroid microcarcinoma: A population-based case-control study. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 24, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leux, C.; Truong, T.; Petit, C.; Baron-Dubourdieu, D.; Guénel, P. Family history of malignant and benign thyroid diseases and risk of thyroid cancer: A population-based case-control study in New Caledonia. Cancer Causes Control 2012, 23, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Li, G.; Wei, Q.; El-Naggar, A.K.; Sturgis, E.M. Family history of cancer and risk of sporadic differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Cancer 2012, 118, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brindel, P.; Doyon, F.; Bourgain, C.; Rachédi, F.; Boissin, J.L.; Sebbag, J.; Shan, L.; Bost-Bezeaud, F.; Petitdidier, P.; Paoaafaite, J.; et al. Family History of Thyroid Cancer and the Risk of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer in French Polynesia. Thyroid 2010, 20, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, C. Are possible risk factors for differentiated thyroid cancer of prognostic importance? Thyroid 2006, 16, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, T.; Vogl, F.; Chappuis, P.O.; Tsang, R.; Brierley, J.; Renard, H.; Sanders, K.; Kantemiroff, T.; Bagha, S.; Goldgar, D.E.; et al. Increased risk for nonmedullary thyroid cancer in the first degree relatives of prevalent cases of nonmedullary thyroid cancer: A hospital-based study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 5307–5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, M.R.; Ekbom, A.; Grimelius, L.; Yuen, J. Parental cancer and risk of papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 1997, 75, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlajinac, H.D.; Adanja, B.J.; Zivaljević, V.R.; Janković, R.R.; Dzodić, R.R.; Jovanović, D.D. Malignant tumors in families of thyroid cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 1997, 36, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoff, K.; Preston-Martin, S.; Mack, W.J.; Monroe, K. A case-control study of maternal risk factors for thyroid cancer in young women. Cancer Causes Control 1995, 6, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ron, E.; Kleinerman, R.; Boice, J.D., Jr.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Flannery, J.T.; Fraumeni, J.F., Jr. A population-based case-control study of thyroid cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1987, 79, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kalarani, I.B.; Sivamani, G.; Veerabathiran, R. Identification of crucial genes involved in thyroid cancer development. J. Egypt. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2023, 35, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Wang, F.; Yang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, C.; Huang, L.; Li, L.; Cheng, H.; Cai, H.; Li, X.; et al. Association Between Genetic Risk, Adherence to Healthy Lifestyle Behavior, and Thyroid Cancer Risk. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2246311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diquigiovanni, C.; Bonora, E. Genetics of Familial Non-Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma (FNMTC). Cancers 2021, 13, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.R.; Kim, J.K.; Ho, J.; Kang, S.W.; Lee, J.; Jeong, J.J.; Nam, K.H.; Chung, W.Y. Familial Non-Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: Distinct Clinicopathological Features and Prognostic Implications in a Large Cohort of 46,572 Patients. Cancers 2025, 17, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capezzone, M.; Robenshtok, E.; Cantara, S.; Castagna, M.G. Familial non-medullary thyroid cancer: A critical review. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 44, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarova, L.; Kleiblova, P.; Janatova, M.; Soukupova, J.; Zemankova, P.; Macurek, L.; Kleibl, Z. CHEK2 Germline Variants in Cancer Predisposition: Stalemate Rather than Checkmate. Cells 2020, 9, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, C.; Marques, I.J.; Saramago, A.; Moura, M.M.; Pojo, M.; Cabrera, R.; Santos, C.; Rosário, F.; Lousa, D.; Vicente, J.B.; et al. Identification of novel candidate predisposing genes in familial nonmedullary thyroid carcinoma implicating DNA damage repair pathways. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 156, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Skopelitou, D.; Miao, B.; Giagiobbe, S.; Paramasivam, N.; Kumar, A.; Diquigiovanni, C.; Bonora, E.; Bandapalli, O.R.; Försti, A.; et al. Prioritization of predisposition genes for familial non-medullary thyroid cancer by whole-genome sequencing. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2025, 192, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).