Abstract

Background: Liposarcoma, one of the most prevalent sarcoma histologies, is recognized for its tendency for extra-pulmonary metastases. While oligometastatic cardiac disease is rarely reported, it poses a unique challenge as oligometastatic sarcomas are often managed with surgical resection. Case Report: We present a case of a 62-year-old man diagnosed with an oligometastatic myxoid liposarcoma (MLPS) to the heart 19 years after the primary tumor resection from the lower limb. The metastatic mass, situated in the pericardium adjacent and infiltrating the left ventricle, was not managed surgically but with a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The patient’s disease remains stable to date, for more than 10 years. Literature Review: We conducted a review of the literature to determine the preferred management approach for solitary cardiac metastases of sarcomas. We also conducted an in-depth analysis focusing on reported cases of MLPS metastasizing to the heart, aiming to extract pertinent data regarding the patient characteristics and the corresponding management strategies. Conclusions: Although clinical diagnoses of solitary or oligometastatic cardiac metastases from sarcomas are infrequent, this case underscores the significance of aggressive management employing chemotherapy and radiotherapy for chemosensitive and radiosensitive sarcomas, especially when surgical removal is high-risk. Furthermore, it challenges the notion that surgery is the exclusive therapeutic option leading to long-term clinical benefit in patients with recurrent sarcomas.

1. Background

Soft tissue sarcomas are a heterogeneous group of malignancies featuring approximately 100 distinct histological subtypes [1]. Liposarcoma is the most common soft tissue sarcoma, making up to 17–25% of all soft tissue sarcomas [2,3]. Malignant adipocyte tumors can be differentiated according to the most recent World Health Organization (WHO) classification in well-differentiated liposarcoma (lipoma-like, sclerosing, inflammatory), dedifferentiated liposarcoma, myxoid liposarcoma (MLPS), pleomorphic liposarcoma, and myxoid pleomorphic liposarcoma [4]. Myxoid (and round cell) is the second most common type of liposarcoma, comprising about 35% of all liposarcoma cases. The median age at diagnosis is 45 years old, and the most common primary locations are in the lower extremities and buttocks [5].

The cytogenetics of MLPS have been well characterized. Specifically, this tumor is driven by the translocation of DDIT3 (DNA damage-inducible transcript 3, also known as C/EBP-homologous protein/CHOP). Most cases (~90%) are driven by the (12;16) (q13;p11) chromosomal translocation that results in the DDIT3-FUS (fused in sarcoma, also known as translocated in sarcoma [TLS]) gene fusion. The remaining cases present with a (12;22) (q13;q12) that leads to a DDIT3-EWSR1 (Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1) gene fusion, with EWSR1 being closely related to FUS [6,7].

MLPS is metastatic in 14–33% of the cases [8,9,10,11], but unlike other sarcomas, it has a great propensity for extra-pulmonary metastases [8,9,10,11]. Common sites of metastasis include soft tissue and bones, lungs, abdominal solid organs (e.g., liver, or less frequently, pancreas and kidneys), and lymph nodes [8,9,10,11]. Cardiac metastases are extremely rare with only 46 cases being reported worldwide [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Published cases of myxoid liposarcoma metastatic to the heart.

In general, sarcoma metastasis to the heart is considered to be a rare phenomenon as most of them remain asymptomatic and go unrecognized; nonetheless, their incidence in post-mortem analysis might be up to 25% [56]. Once diagnosed, cardiac metastases warrant urgent treatment, given the high mortality rate [57,58]. However, complete surgical resection poses significant risks due to the difficult anatomic location, resulting in high perioperative mortality rates and uncertain benefits for patients [59]. Individual tumor characteristics, location of the metastasis, risk of imminent death (e.g., secondary to arrhythmia, tamponade, thromboembolic events, heart failure), risk of perioperative mortality, and patients’ wishes should guide the therapeutic decision-making process.

In this paper, we present the case of a patient with solitary cardiac metastasis 19 years after the initial diagnosis and management of an MLPS of the thigh, who has been in long-term remission (>10 years) following aggressive chemotherapy and radiotherapy to the cardiac oligometastatic deposit, without any surgical intervention. To our knowledge, this patient, apart from being the longest survivor following cardiac metastasis of MLPS, is the only reported case with an oligometastatic cardiac liposarcoma metastasis managed without surgery (other than two cases where the patients died soon after the diagnosis and before the therapeutic plan was initiated [16,18]) (In the case described by Motevalli et al., the patient was initially diagnosed with a mediastinal metastasis via sonography. The metastasis was confirmed to be cardiac in the post-mortem autopsy).

2. Case Report

We report the case of a 62-year-old man with MLPS of the lower limb with a late oligometastatic tumor to the heart. The metastasis was managed with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, resulting in stable disease to this day, with more than 10 years of follow-up.

This patient was diagnosed at the age of 43 with primary MLPS confined to the vastus lateralis muscle of the thigh. Tumor resection was followed by adjuvant radiotherapy, and he remained disease-free for 19 years. Post-treatment, the patient had left lower extremity lymphedema and neuropathy but no local relapse.

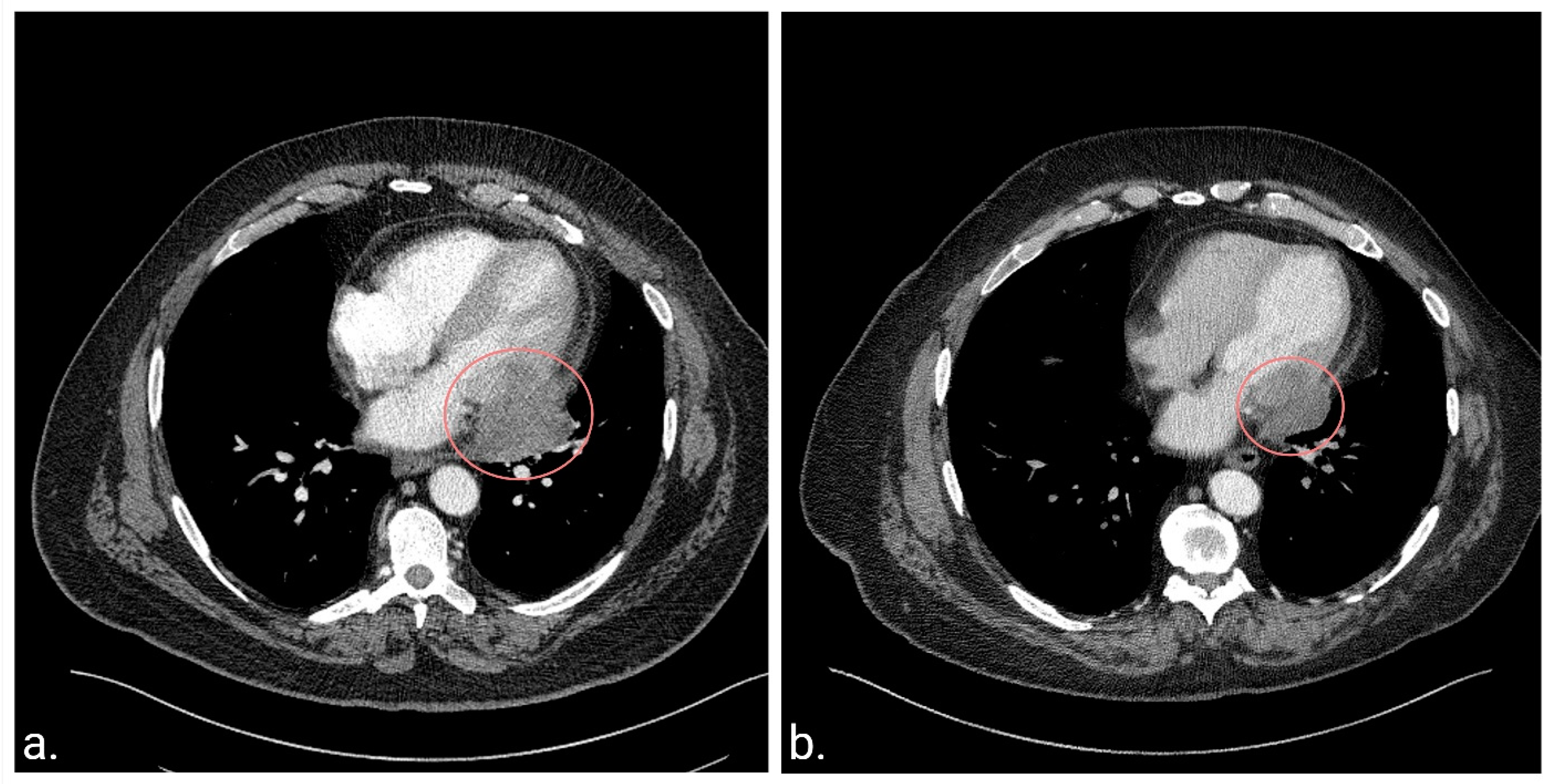

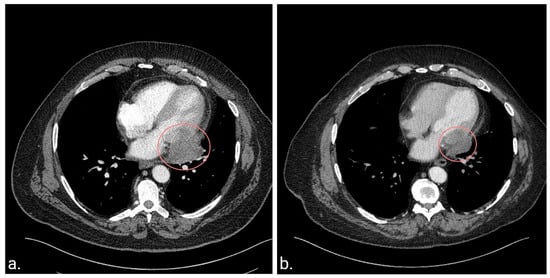

At the age of 62 years, while evaluating his lymphedema symptoms, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scans (CT) revealed a pericardial mass. The patient did not experience any symptoms attributed to the cardiac mass at the time of diagnosis. Subsequent chest CT (Figure 1a) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a solitary 5.2 × 4.7 × 3.5 cm mass involving the pericardium and infiltrating the lateral wall of the left ventricle. Cardiac MRI was selected to complement the CT findings due to its superiority in characterizing soft tissue and its high specificity in distinguishing between benign pseudomasses and malignant cardiac tumors [60,61]. Additionally, MRI becomes particularly relevant when recurrent soft-tissue sarcoma is suspected due to its high diagnostic accuracy [62].

Figure 1.

Chest computerized tomography (CT) scans at diagnosis of the cardiac metastasis and 10 years post-treatment. (a). CT scan before the initiation of chemotherapy and radiotherapy demonstrating a heterogeneous mass located in the pericardium and extending into the left ventricle. (b). The latest CT scan 10.5 years after diagnosis demonstrating a residual soft tissue mass centered in the left posterolateral pericardium, which has remained stable since the completion of therapy.

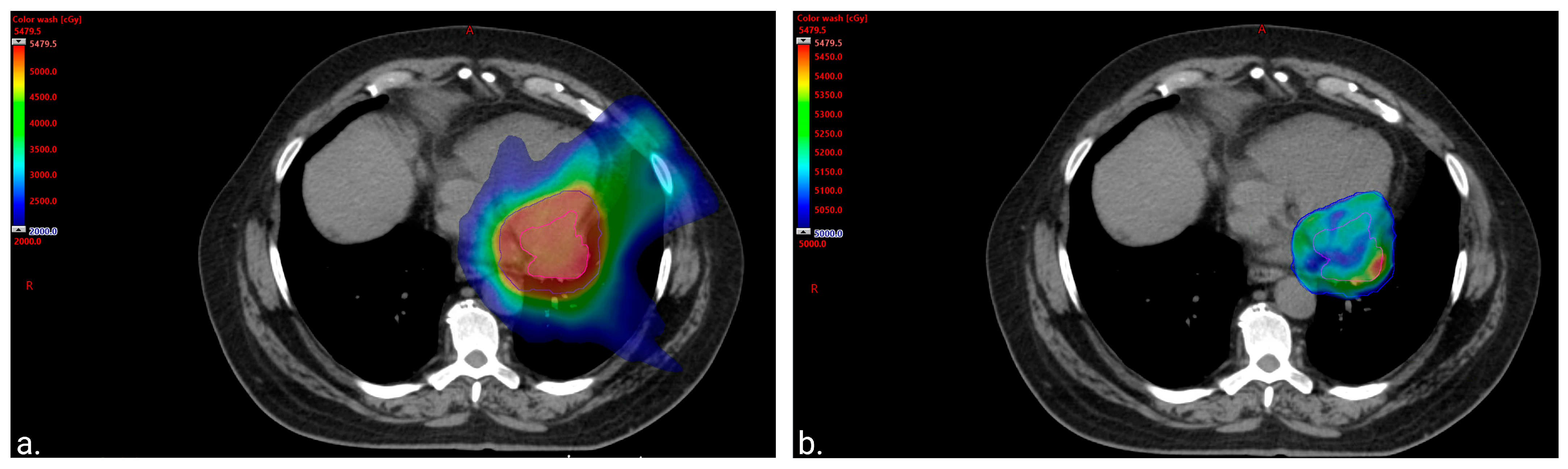

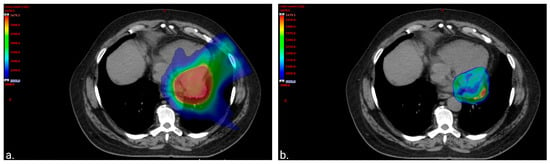

Metastatic MLPS was confirmed following a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). At the VATS procedure, it was noted that the tumor was not attached to the pericardium at the site of biopsy. The treatment plan included neo-adjuvant chemo- and radiotherapy prior to determining the feasibility of surgical resection, as the original tumor extent was not felt to be amenable to local excision. The patient received four cycles of doxorubicin (30 mg/m2) and ifosfamide (3750 mg/m2) on days 1 and 2 (every 21–28 days) with mesna (750 mg/m2) and growth factor support. This resulted in a modest (~20%) decrease in maximal tumor dimension. He subsequently received 50 Gray (Gy) in 25 fractions, using an intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) technique, sparing the heart and lungs of high doses (Figure 2). This was delivered with two concomitant cycles of radiosensitizing chemotherapy with mitomycin (6 mg/m2) and cisplatin (45 mg/m2) on day 1 (every 28 days), leading to a decrease in tumor size from 5 × 3.7 cm to 4 × 2.5 cm. Doxorubicin was omitted from the radiosensitizing regimen to minimize the expected cardiotoxicity related to chest irradiation, and the patient was closely monitored but did not display any signs of declining cardiac function. In anticipation of surgery, additional chemotherapy with gemcitabine (900 mg/m2) on day 1 and gemcitabine (900 mg/m2) with docetaxel (75 mg/m2) on day 8 (every 21 days) was initiated. Cycle 3 was dose-reduced by 25%, and the patient received steroids for presumed chemotherapy-induced pneumonitis. Following cycle 3, he developed worsening pulmonary toxicity with a differential diagnosis, including infection and worsening inflammation; thus, chemotherapy was discontinued.

Figure 2.

Color wash images to visually represent the distribution of the radiation. (a). Color wash image of 20 gray (Gy) volume displaying sparing of the lung and anterior heart. The volume of the total lung receiving at least 20 Gy (total lung V20Gy) was equal to 10.6% (left lung V20Gy = 23.4% and right lung V20Gy = 0%). The heart mean dose was equal to 20 Gy with only 75 cubic centimeters (cc) of the treatment volume overlapping with the heart and 150 cc of the heart getting ≥30 Gy. (b). Color wash image of 50 Gy volume displaying sparing of the apex of the left ventricle from the prescription dose.

CT scan 8 weeks after chemotherapy discontinuation showed a slight increase in tumor size, but subsequent imaging 6 weeks later revealed tumor stability. Surgical resection was deemed high-risk, and as the patient had stable disease with a low likelihood of available chemotherapeutic modalities further reducing the size of the mass, observation was recommended. Surveillance included CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis every 2–3 months for 1.5 years, every 6 months until 5 years, then annually. The patient’s disease has remained stable to date for >10 years since the completion of therapy (Figure 1b). Notably, previous treatment was well-tolerated in terms of cardiac toxicity, with the patient showing no signs or symptoms of declining cardiac function, and a cardiac MRI performed five years post-treatment revealed only mild hypokinesis of the basal lateral left ventricular wall, with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction of 57%.

3. Discussion

Cardiac metastasis from sarcoma is rare; thus, there is no consensus on a treatment approach.

In our initial literature review, we aimed to assess whether surgical resection is indeed the preferred method for managing solitary cardiac metastases of sarcomas. Employing the terms “Sarcoma(s)” and “Cardiac metastasis/es” on PubMed, we identified 161 published cases (in case reports and case series) of sarcomas metastasizing to the heart. After excluding the cases where the metastases were diagnosed post-mortem (n = 6) or at the time of the primary diagnosis (n = 36), we analyzed the remaining cases (n = 119). Among these, approximately one-third of the patients had isolated cardiac metastases (n = 41). Since surgical resection of cardiac metastasis seems to be the anecdotal recommendation in the field [12,63], only a minority of the reviewed cases (n = 13, 32.5%) did not undergo surgery. In most of these reports, (n = 11, 84.6%) surgical resection was not pursued due to the patient’s status, the patient’s preference, or the inoperable nature of the lesion. Thus, no conclusions can be drawn regarding the efficacy of medical versus surgical management in this patient group.

Cardiac metastases may pose an imminent risk of death, and in such cases, urgent surgical intervention may be warranted [38,48,59,64]. However, in all other instances, surgical resection should not be presented as the exclusive therapeutic modality as it often fails to provide benefit to the patients [59]. Specifically, cases have been described when surgery was attempted, but complete resection was not possible [34,41]. Additionally, even when negative surgical margins had been achieved, local recurrences occurred [20,21,44,65,66,67], in some cases as soon as prior to the initiation of the adjuvant therapy [66]. Ultimately, intracardiac procedures are complex and carry a high risk of intra- or perioperative mortality [35,38,68,69]. Particularly for MLPS, despite the anatomic challenges, surgical resection was attempted in approximately two-thirds of reported cardiac metastases (Table 1). For those who did not undergo surgery, the most common reasons were patient death soon after diagnosis or heavy metastatic burden.

Notably, our literature review revealed cases of patients with cardiac sarcoma metastases treated with radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and/or immunotherapy, achieving stable disease, or even having partial and complete responses without surgical intervention [37,54,70,71,72]. One of these patients had complete radiological resolution on MRI of the cardiac recurrence of a malignant fibrous histiocytoma following treatment with high-dose chemotherapy followed by peripheral blood progenitor cell transplant and immunotherapy with interleukin-2 and 13-cis-retinoic acid [72]. Supporting these data, a single-institution retrospective study in Japan, where none of the patients with sarcoma had resection of cardiac metastasis, suggested that radiotherapy might provide an alternative local treatment option as the median survival of patients receiving radiotherapy was 10.5 months compared to 3.5 months for those who did not [73]. Additionally, the authors claimed that a total dose of more than 45 Gy should be given to achieve the best clinical response [73].

Particularly for MLPS, which is among the most chemosensitive [74] and radiosensitive [75] sarcomas, only two cases have been described in which metastatic cardiac MLPS has been treated with radiotherapy, and both responded to treatment [37,54]. In one of them, the patient had multifocal disease and was initially treated with six cycles of doxorubicin (60–75 mg/m2). Even though the patient had stable disease, he received adjuvant radiotherapy (35Gy) in 15 fractions to the cardiac lesion due to concerns for arrhythmias with a higher dose. The cardiac lesion remained stable, but new metastatic lesions appeared in the meantime [37]. The other patient, who had multifocal disease and symptoms of heart failure attributed to his cardiac metastasis, had complete resolution of the heart failure symptoms following radiotherapy with 40 Gy [54] over 30 days. Additionally, two cases have been reported in which cardiac MLPS metastases were treated solely with chemotherapy (etoposide or cyclophosphamide, dacarbazine, vincristine, adriamycin) [40,45]. Neither patient responded to treatment, but both had extensive disease at the time of diagnosis, and one of them received single-agent etoposide, which is inferior to standard anthracycline-based chemotherapy [76].

To the best of our knowledge, no other case of solitary cardiac MLPS has been managed primarily with radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The encouraging outcome of our patient, who is by far the longest-reported survivor without disease progression following cardiac metastasis of liposarcoma, is supported by a case described by Pino et al., who reported a patient with a right atrial metastasis of an MLPS which recurred in the atrium one year after surgical management [21]. The recurrence was managed with radiotherapy, leading to complete regression followed by chemotherapy (radiation dose and chemotherapy agents not reported), and at the 6-month follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic [21].

4. Conclusions

To conclude, the decade-long disease stability observed in our patient without surgical intervention remains particularly noteworthy even when accounting for certain positive prognostic factors of this patient. These prognostic factors included a prolonged disease-free interval, a solitary metastasis for which the patient was asymptomatic, and the chemosensitive and radiosensitive tumor type.

Moreover, this case report highlights the importance of multidisciplinary care and underscores that definitive management of oligometastatic sarcoma metastasis, especially when surgical removal is high-risk (e.g., in the heart, brain, or liver hilum), can include chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.I.R.; literature review and writing—original draft preparation, G.M.S.; writing—review and editing, G.M.S., B.L.S., I.A.P., M.T.H., T.P.H., S.H.O. and S.I.R.; Figure 1 was generated by S.I.R. and Figure 2 was generated by I.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mayo Clinic (protocol code 12-001661; approved on 10 April 2014).

Informed Consent Statement

The patient provided authorization to utilize their medical record for research. We confirmed there was no change to this status in the Minnesota Research Authorization Database prior to publication.

Data Availability Statement

Further information can be provided upon request to the corresponding author of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours, 5th ed.; Publication of the WHO Classification of Tumours; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, R.; Wheeler, Y. Liposarcoma. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, V.Y.; Fletcher, C.D.M. WHO classification of soft tissue tumours: An update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology 2014, 46, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbaraglia, M.; Bellan, E.; Dei Tos, A.P. The 2020 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours: News and perspectives. Pathologica 2021, 113, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaggio, R.; Coffin, C.M.; Weiss, S.W.; Bridge, J.A.; Issakov, J.; Oliveira, A.M.; Folpe, A.L. Liposarcomas in young patients: A study of 82 cases occurring in patients younger than 22 years of age. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2009, 33, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scapa, J.V.; Cloutier, J.M.; Raghavan, S.S.; Peters-Schulze, G.; Varma, S.; Charville, G.W. DDIT3 Immunohistochemistry Is a Useful Tool for the Diagnosis of Myxoid Liposarcoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2021, 45, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Losada, J.; Sánchez-Martín, M.; Rodríguez-García, M.A.; Pérez-Mancera, P.A.; Pintado, B.; Flores, T.; Battaner, E.; Sánchez-Garćia, I. Liposarcoma initiated by FUS/TLS-CHOP: The FUS/TLS domain plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of liposarcoma. Oncogene 2000, 19, 6015–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visgauss, J.D.; Wilson, D.A.; Perrin, D.L.; Colglazier, R.; French, R.; Mattei, J.-C.; Griffin, A.M.; Wunder, J.S.; Ferguson, P.C. Staging and Surveillance of Myxoid Liposarcoma: Follow-up Assessment and the Metastatic Pattern of 169 Patients Suggests Inadequacy of Current Practice Standards. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 7903–7911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratori, F.; Bettini, L.; Frenos, F.; Mondanelli, N.; Greto, D.; Livi, L.; Franchi, A.; Roselli, G.; Scorianz, M.; Capanna, R.; et al. Myxoid Liposarcoma: Prognostic Factors and Metastatic Pattern in a Series of 148 Patients Treated at a Single Institution. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 2018, 8928706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniball, J.; Sumathi, V.P.; Kindblom, L.G.; Abudu, A.; Carter, S.R.; Tillman, R.M.; Jeys, L.; Spooner, D.; Peake, D.; Grimer, R.J. Prognostic factors and metastatic patterns in primary myxoid/round-cell liposarcoma. Sarcoma 2011, 2011, 538085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuglø, H.M.; Maretty-Nielsen, K.; Hovgaard, D.; Keller, J.; Safwat, A.A.; Petersen, M.M. Metastatic pattern, local relapse, and survival of patients with myxoid liposarcoma: A retrospective study of 45 patients. Sarcoma 2013, 2013, 548628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikuta, K.; Sakai, T.; Koike, H.; Okada, T.; Imagama, S.; Nishida, Y. Cardiac metastases from primary myxoid liposarcoma of the thigh: A case report. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 18, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezak, B.; Artemiou, P.; Hulman, M.; Chnupa, P.; Busikova, P.; Bartovic, B. Metastatic myxoid liposarcoma of the interventricular septum. J. Card. Surg. 2020, 35, 662–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porres-Aguilar, M.; De Cicco, I.; Anaya-Ayala, J.E.; Porres-Muñoz, M.; Santos-Martínez, L.E.; Flores-García, C.A.; Osorio, H. Cardiac metastasis from liposarcoma to the right ventricle complicated by massive pulmonary tumor embolism. Arch. Cardiol. Mex. 2019, 89, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passhak, M.; Amsalem, Y.; Vlodavsky, E.; Varaganov, I.; Bar-Sela, G. Cerebral Liposarcoma Embolus From Heart Metastasis Successfully Treated by Endovascular Extraction Followed by Cardiac Surgery. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018, 52, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motevalli, D.; Tavangar, S.M. Extensive left ventricular, pulmonary artery, and pericardial metastasis from myxoid liposarcoma 16 years after the initial detection of the primary tumour: A case report and review of the literature. Malays. J. Pathol. 2017, 39, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dendramis, G.; Di Lisi, D.; Paleologo, C.; Novo, G.; Novo, S. Large left ventricular metastasis in patient with liposarcoma. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2016, 17 (Suppl S2), e166–e168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, R.P.; Schowinsky, J.T.; Lindeque, B.G.P. Myxoid Liposarcoma of the Thigh with Metastasis to the Left Ventricle of the Heart: A Case Report. JBJS Case Connect. 2015, 5, e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Feng, Q.; Yu, C.; Zhu, S. Anesthetic management of the removal of a giant metastatic cardiac liposarcoma occupying right ventricle and pulmonary artery. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2014, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajtai, Z.; Korngold, E.; Hooper, J.E.; Sheppard, B.C.; Foster, B.R.; Coakley, F.V. Suprarenal retroperitoneal liposarcoma with intracaval tumor thrombus: An imaging mimic of adrenocortical carcinoma. Clin. Imaging 2014, 38, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, P.G.; Zampi, G.; Pergolini, A.; Pero, G.; Polizzi, V.; Sbaraglia, F.; Minardi, G.; Musumeci, F. Metastatic liposarcoma of the heart. Case series and brief literature review. Herz 2013, 38, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottahedi, B.; Asadi, M.; Amini, S.; Alizadeh, L. Round cell liposarcoma metastatic to the heart. J. Card. Surg. 2013, 28, 672–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaimy, A.; Rösch, J.; Weyand, M.; Strecker, T. Primary and metastatic cardiac sarcomas: A 12-year experience at a German heart center. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2012, 5, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Golfín, C.; Jiménez López-Guarch, C.; Enguita Valls, A.B.; Forteza, A. Cardiac myxoid liposarcoma metastasis: Cardiac magnetic resonance features. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 13, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Markovic, Z.Z.; Mladenovic, A.; Banovic, M.; Ivanovic, B. Correlation of different imaging modalities in pre-surgical evaluation of pericardial metastasis of liposarcoma. Chin. Med. J. 2012, 125, 3752–3754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitomi, M.; Kimura, K.; Iguchi, Y.; Hayashida, A.; Nishimura, H.; Irei, I.; Okawaki, M.; Ikeda, H. A case of stroke due to tumor emboli associated with metastatic cardiac liposarcoma. Intern. Med. 2011, 50, 1489–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, U.; Zamani, A.; Gormus, N.; Paksoy, Y.; Avunduk, M.C.; Demirbas, S. The first case report of a metastatic myxoid liposarcoma invading the left atrial cavity and pulmonary vein. Heart Surg. Forum 2011, 14, E261–E263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazopoulos, G.; Papastavrou, L.; Kantartzis, M. Giant metastatic cardiac and abdominal liposarcomas causing hemodynamic deterioration. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 59, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.; Lemos, J.; Vaz, A.; Correia, A.; Girão, F.; Henriques, P. Something inside the heart: A myxoid liposarcoma with cardiac involvement. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 2011, 30, 341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Komoda, S.; Komoda, T.; Weichert, W.; Hetzer, R. Surgical treatment for epicardial metastasis of myxoid liposarcoma involving atrioventricular sulcus. J. Card. Surg. 2009, 24, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.; Cronin, P.; Lucas, D.R.; Prager, R.; Kazerooni, E.A. Metastatic shoulder liposarcoma to the right ventricle: CT findings. J. Thorac. Imaging 2007, 22, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairman, E.B.; Mauro, V.M.; Cianciulli, T.F.; Rubio, M.; Charask, A.A.; Bustamante, J.; Barrero, C.M. Liposarcoma causing left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and syncope: A case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2005, 21, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, T.; Amano, J.; Sakaguchi, M.; Kitahara, H. Successful resection of cardiac metastatic liposarcoma extending into the SVC, right atrium, and right ventricle. J. Card. Surg. 2005, 20, 364–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyama, A.; Isowa, N.; Chihara, K.; Ito, T. Pericardial metastasis of myxoid liposarcoma causing cardiac tamponade. Jpn. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005, 53, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.S.; Barnard, M.; Freeman, M.R.; Hutchison, S.J.; Graham, A.F.; Chiu, B. Cardiac encasement by metastatic myxoid liposarcoma. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2002, 11, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.P.; Ng, C.S.; Wan, S.; Lee, T.W.; Wan, I.Y.; Yim, A.P.; Arifi, A.A. Giant metastatic myxoid liposarcoma causing cardiac tamponade: A case report. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 32, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ng, C.; Stebbing, J.; Judson, I. Cardiac metastasis from a myxoid liposarcoma. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 13, 384–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, K.; Okubo, T.; Kamigaki, Y.; Kin, H. Cardiac metastatic liposarcoma. Jpn. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2000, 48, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacem, K.; Vachon, L.; Benard, T.; Delaire, C.; Bouvier, J.M. Right atrioventricular metastasis of a myxoid liposarcoma. Case report and al review of the literature. Arch. Mal. Coeur Vaiss. 2000, 93, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Hatton, M.Q.; Reid, R.; Barrett, A. Metastatic liposarcoma: A cause of symptomatic acute pericarditis. Sarcoma 1997, 1, 181–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmi, U.; Fellner, F.; Friedel, N.; Wieseler, H. Myxoid liposarcoma with pericardial metastasis. Rontgenpraxis 1997, 50, 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- Papa, M.Z.; Shinfeld, A.; Klein, E.; Greif, F.; Ben-Ari, G. Cardiac metastasis of liposarcoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 1994, 55, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, M.; Kondo, T.; Uno, Y. Metastatic cardiac liposarcoma diagnosed by thallium-201 myocardial single photon emission computed tomography. Clin. Nucl. Med. 1993, 18, 801–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langlard, J.M.; Lefévre, M.; Fiche, M.; Chevallier, J.C.; Godin, O.; Bouhour, J.B. [Right atrioventricular metastasis of myxoid liposarcoma. Prolonged course after repeated surgery and chemotherapy]. Arch. Mal. Coeur Vaiss. 1992, 85, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maloisel, F.; Dufour, P.; Drawin, T.; Liu, K.L.; Bellocq, J.P.; Sacrez, A.; Oberling, F. [Embolization of the foramen ovale in metastatic course of abdominal liposarcoma]. Ann. Cardiol. Angeiol. 1991, 40, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Schrem, S.S.; Colvin, S.B.; Weinreb, J.C.; Glassman, E.; Kronzon, I. Metastatic cardiac liposarcoma: Diagnosis by transesophageal echocardiography and magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 1990, 3, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozoux, J.P.; Berton, C.; de Calan, L.; Guillou, L.; Cosnay, P. Cardiac metastasis from a myxoid liposarcoma. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1988, 96, 668–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, P.; O’Callaghan, W.G.; Peyton, R.; Sethi, G.; Maley, T. Metastatic liposarcoma of the right ventricle with outflow tract obstruction: Restrictive pathophysiology predicts poor surgical outcome. Am. Heart J. 1988, 115, 696–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrange, J.L.; Despins, P.; Spielman, M.; Le Chevalier, T.; de Lajartre, A.Y.; Fontaine, F.; Sarrazin, D.; Contesso, G.; Génin, J.; Rouesse, J.; et al. Cardiac metastases. Case report on an isolated cardiac metastasis of a myxoid liposarcoma. Cancer 1986, 58, 2333–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzarello, R.A.; Goldberg, S.M.; Goldman, M.A.; Gottesman, R.; Fetten, J.V.; Brown, N.; Kahn, E.I.; Stein, H.L. Tumor of the heart diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1985, 5, 989–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ravikumar, T.S.; Topulos, G.P.; Anderson, R.W.; Grage, T.B. Surgical resection for isolated cardiac metastases. Arch. Surg. 1983, 118, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, J.D.; Axel, L.; Adams, J.R.; Schiller, N.B.; Simpson, P.C., Jr.; Gertz, E.W. Computed tomography: A new method for diagnosing tumor of the heart. Circulation 1981, 63, 448–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroudis, C.; Way, L.W.; Lipton, M.; Gertz, E.W.; Ellis, R.J. Diagnosis and operative treatment of intracavitary liposarcoma of the right ventricle. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1981, 81, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, E.C.; Rubenfeld, S. Cardiac metastasis from myxoid liposarcoma emphasizing its radiosensitivity. Am. J. Roentgenol. Radium Ther. Nucl. Med. 1968, 103, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, R.W.; Garvin, C.F. Tumors of the heart and pericardium. Am. Heart J. 1939, 17, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallahan, D.E.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Borow, K.M.; Bostwick, D.G.; Simon, M.A. Cardiac metastases from soft-tissue sarcomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 1986, 4, 1662–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurber, D.L.; Edwards, J.E.; Achor, R.W. Secondary malignant tumors of the pericardium. Circulation 1962, 26, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, I.K. Cardiac lymphatic involvement by metastatic tumor. Cancer 1972, 29, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, G.V., Jr.; Meredith, J.W.; Breyer, R.H.; Mills, S.A. Surgical implications in malignant cardiac disease. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1983, 36, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, N.; Cheezum, M.K.; Aghayev, A.; Padera, R.; Vita, T.; Steigner, M.; Hulten, E.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Dorbala, S.; Di Carli, M.F.; et al. Assessment of Cardiac Masses by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Histological Correlation and Clinical Outcomes. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e007829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumma, R.; Dong, W.; Wang, J.; Litt, H.; Han, Y. Evaluation of cardiac masses by CMR-strengths and pitfalls: A tertiary center experience. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 32, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghat, S.; Sedaghat, M.; Meschede, J.; Jansen, O.; Both, M. Diagnostic value of MRI for detecting recurrent soft-tissue sarcoma in a long-term analysis at a multidisciplinary sarcoma center. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.Y.; Cummings, R.G.; Reimer, K.A.; Lowe, J.E. Chondrosarcoma metastatic to the heart. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1988, 45, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maebayashi, A.; Nagaishi, M.; Nakajima, T.; Hata, M.; Xiaoyan, T.; Kawana, K. Successful surgical treatment of cardiac metastasis from uterine leiomyosarcoma: A case report and literature review. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, M.; García-Camarero, T.; Expósito, V.; Val-Bernal, J.F.; Gómez-Román, J.J.; Garijo, M.F. Cardiac intracavitary metastasis of a malignant solitary fibrous tumor: Case report and review of the literature on sarcomas with left intracavitary extension. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2007, 16, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyigun, T.; Ciloglu, U.; Ariturk, C.; Civelek, A.; Tosun, R. Recurrent cardiac metastasis of primary femoral osteosarcoma: A case report. Heart Surg. Forum 2010, 13, E333–E335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vargas-Barron, J.; Keirns, C.; Barragan-Garcia, R.; Beltran-Ortega, A.; Rotberg, T.; Santana-Gonzalez, A.; Salazar-Davila, E. Intracardiac extension of malignant uterine tumors. Echocardiographic detection and successful surgical resection. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1990, 99, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.L.; Boak, J.G. Cardiac metastasis from uterine leiomyosarcoma. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1983, 2, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haslinger, M.; Dinges, C.; Granitz, M.; Klieser, E.; Hoppe, U.C.; Lichtenauer, M. Right Heart Failure Due to Secondary Chondrosarcoma in the Right Atrium. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, e009824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzato, F.; D’Ercole, A.; De Luca, G.; Aiello, F.B.; Croce, A. Neck subcutaneous nodule as first metastasis from broad ligament leiomyosarcoma: A case report and review of literature. BMC Surg. 2020, 20, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramohan, N.K.; Hussain, M.B.; Nayak, N.; Kattoor, J.; Pandey, M.; Krishnankutty, R. Multiple cardiac metastases from Ewing’s sarcoma. Can. J. Cardiol. 2005, 21, 525–527. [Google Scholar]

- Recchia, F.; Saggio, G.; Amiconi, G.; Di Blasio, A.; Cesta, A.; Candeloro, G.; Rea, S.; Nappi, G. Cardiac metastases in malignant fibrous histiocytoma. A case report. Tumori 2006, 92, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, S.; Hashimoto, N.; Araki, N.; Hamada, K.; Naka, N.; Joyama, S.; Kakunaga, S.; Ueda, T.; Myoui, A.; Yoshikawa, H. Eleven cases of cardiac metastases from soft-tissue sarcomas. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 41, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.L.; Fisher, C.; Al-Muderis, O.; Judson, I.R. Differential sensitivity of liposarcoma subtypes to chemotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41, 2853–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, P.W.; Deheshi, B.M.; Ferguson, P.C.; Wunder, J.S.; Griffin, A.M.; Catton, C.N.; Bell, R.S.; White, L.M.; Kandel, R.A.; O’Sullivan, B. Radiosensitivity translates into excellent local control in extremity myxoid liposarcoma: A comparison with other soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer 2009, 115, 3254–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassif, E.F.; Keung, E.Z.; Thirasastr, P.; Somaiah, N. Myxoid Liposarcomas: Systemic Treatment Options. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2023, 24, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).