Abstract

The lifetime risk of breast and ovarian cancer increases substantially for individuals with mutations in BRCA1/2. The evidence indicates that BRCA1/2 mutation carriers benefit from early cancer detection and prevention strategies. However, data on the patterns of risk-reducing interventions are lacking. This study investigated the patterns of surveillance and risk-reducing interventions among unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. A cohort of unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers was identified from the Korean Hereditary Breast cAncer (KOHBRA) study database, and a telephone survey was conducted. The survey included questions on the incidence of new cancers, patterns of cancer (breast, ovarian, prostate, other) surveillance, chemoprevention, risk-reducing surgery, and reasons for participating in risk-reducing strategies. Between November 2016 and November 2020, 192 BRCA1/2 mutation carriers were contacted, of which 83 responded. After excluding 37 responders who refused to participate, 46 participants (15 males, 31 females) were included in the analysis. The mean ± SD follow-up time was 103 ± 17 months (median 107, range 68~154), and the mean ± SD age was 31 ± 8 years. Ten BRCA1/2 mutation carriers developed breast cancer, one developed ovarian cancer, and three developed other cancers. Six BRCA1/2 mutation carriers (19.4%) underwent annual breast cancer surveillance as recommended by guidelines, while none underwent ovarian or prostate cancer surveillance. Three carriers (9.7%) used chemoprevention for breast cancer. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy was performed on only one BRCA1/2 mutation carrier. The rates of breast/ovarian cancer surveillance, chemoprevention, and risk-reducing surgery were low among unaffected Korean BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Given this cohort’s relatively high risk of developing breast cancer, strategies to encourage active participation in risk reduction are needed.

1. Introduction

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes that play a critical role in repairing DNA damage and maintaining the integrity of double-stranded DNA. Germline mutations in these genes are associated with increased risks of developing several types of cancers, including breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancer [1,2,3].

The lifetime risks of developing breast and ovarian cancer in female BRCA1 mutation carriers are reported to be 72% and 44%, respectively, by the age of 80. Female BRCA2 mutation carriers’ lifetime risks are reported to be 69% for breast cancer and 17% for ovarian cancer [4]. Han et al. [5] showed that the cumulative risks of developing breast cancer by the age of 70 were 72.1% and 66.3% for female BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, respectively, highlighting the significant increase in breast cancer risks for female BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Moreover, the cumulative risks of developing breast cancer in male BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers are 1% and 7–8%, respectively [6], significantly higher than the 0.1% risk observed in the average male population. Additionally, the risks of developing various cancers, such as salpinx, peritoneum, endometrium, pancreas, prostate, and colorectum, increased in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers compared to the average population in many studies.

As a result, the NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) guidelines [7] suggest risk-reducing strategies for unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, including cancer surveillance, chemoprevention, and risk-reducing surgery. Females with pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants of BRCA are recommended to undergo annual mammography and breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) starting at age 25 for breast cancer surveillance. For ovarian cancer risk management, risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy is recommended between the ages of 35 and 40 upon completion of childbearing. Male carriers are advised to undergo clinical breast exams starting at age 35 and prostate cancer screening with a digital rectal exam and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing starting at age 40, especially for BRCA2 carriers. Moreover, screening for other types of cancer with increased risk, such as pancreatic cancer or melanoma, is also considered based on family history.

The mainstay of risk-reducing surgery is prophylactic bilateral mastectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. While risk-reducing surgery can provide survival benefits, it is an invasive and irreversible method of removing an unaffected organ. In addition, the aesthetic aspects of mastectomy and iatrogenic menopause can result in a decreased quality of life. Thus, it is essential for carriers to receive sufficient genetic counseling, and healthcare providers should approach this carefully when considering risk-reducing surgery.

Chemoprevention could be considered for carriers who do not opt for risk-reduction surgery. Tamoxifen, which has been shown to reduce breast cancer incidence by 62% in unaffected BRCA2 mutation carriers in a small study comparing its effectiveness with a placebo, is one option [8]. Additionally, oral contraceptives have been reported to reduce ovarian cancer risk by 50–55% in BRCA1 mutation carriers and by 40% in BRCA2 mutation carriers [9].

In spite of the benefits of the recommended risk-reducing strategies for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, it is currently unknown whether unaffected Korean BRCA1/2 carriers participate in them. Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the current status of surveillance, chemoprevention, and risk-reducing surgery among unaffected Korean BRCA1/2 carriers.

2. Materials and Methods

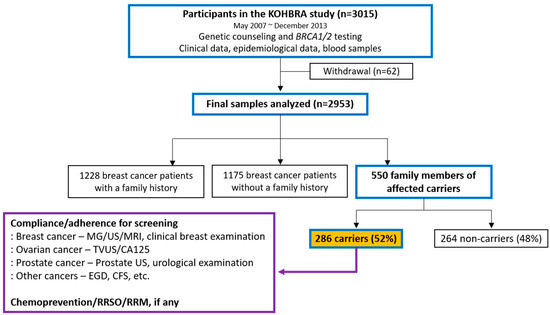

This study was conducted on unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer, identified from the Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer (KOHBRA) study database [10,11,12]. The KOHBRA study comprises 2953 BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, and we identified family members of carriers who were affected by breast or ovarian cancer. As a result, 286 unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers were identified (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of study progression.

Due to the Personal Information Protection Act in Korea and the discontinuation of enrollment in the KOHBRA study since December 2013, obtaining follow-up data from the enrolled cohort or acquiring information from national statistics was limited initially. However, since the KOHBRA study cohort agreed that the informed consent form permitted contact for follow-up information and genetic testing at enrollment, this study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital (SCHBC 2016-08-017-001).

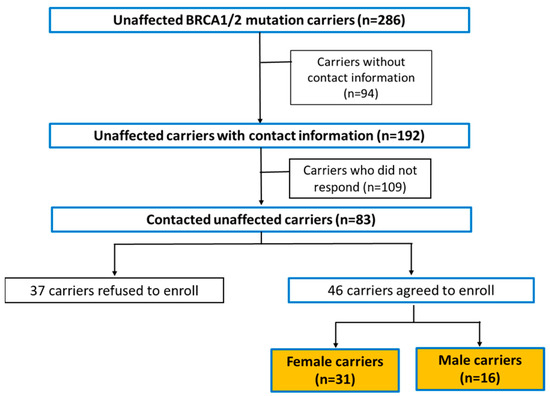

We attempted to contact 192 unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers eligible for inclusion in this study. Of these, 83 carriers successfully responded, and 37 declined to participate. Ultimately, our analysis was based on telephone survey responses from 46 carriers (31 females and 15 males) who agreed to participate in this study (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Study cohort recruitment process.

We conducted nine follow-up telephone surveys from August 2016 to December 2020, contacting the 46 unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. The study period was defined as from when blood was taken for BRCA1/2 testing to the most recent risk-reducing strategy. The telephone survey questionnaire included questions about the following:

- Surveillance patterns for breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers;

- Involvement in chemoprevention and the type of chemoprevention agent used;

- Whether the carrier had undergone risk-reducing surgery and the type of surgery performed;

- Any new onset of primary cancer;

- The reasons for participating in risk-reducing strategies.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants and New Onset of Primary Cancer

The baseline participant characteristics are described in Table 1. Of the 46 unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, the mean ± SD age was 30 ± 8 years, and the mean ± SD follow-up duration was 8.6 years (103 ± 17 months). Eleven participants had a BRCA1 mutation (23.9%), and thirty-five had a BRCA2 mutation (76.1%). Among the thirty-one female carriers, ten (32.3%) developed breast cancer, and one (3.2%) developed ovarian cancer. None of the male carriers developed breast or prostate cancer. The mean age of breast cancer onset among the 10 BRCA mutation carriers was 46 years. Detailed descriptions of the 10 BRCA mutation carriers are provided in Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics.

Table 2.

Characteristics of ten BRCA mutation carriers who developed breast cancer.

3.2. Patterns of Risk-Reducing Strategies

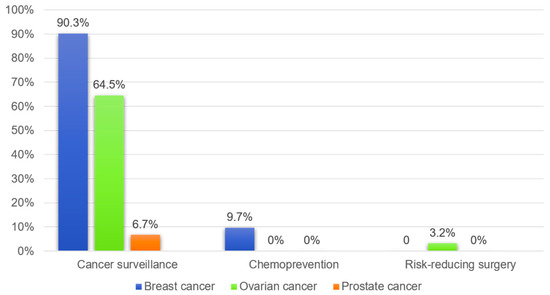

Of the 31 female carriers, 28 (90.3%) underwent at least one surveillance procedure for breast cancer, while 20 (64.5%) underwent surveillance for ovarian cancer. Only one (6.7%) of the fifteen male carriers underwent prostate cancer surveillance. Of the forty-six carriers, three female carriers (9.7%) were engaged in chemoprevention; all were taking tamoxifen. Additionally, one carrier (3.2%) underwent risk-reducing surgery through bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Patterns of risk-reducing strategies used by unaffected BRCA1/2 carriers.

3.3. Frequency and Methods of Cancer Surveillance

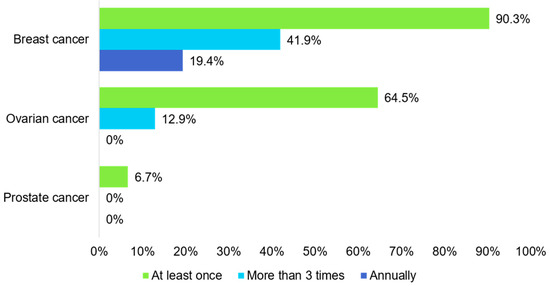

The frequency of cancer surveillance was assessed for carriers who reported conducting surveillance as a risk-reducing strategy (Figure 4). Of the female carriers, 28 (90%) underwent breast cancer surveillance at least once. The Korean National Cancer Screening Program provides free breast cancer screening every two years; a total of 13 (41.9%) women underwent screening more than three times during the follow-up period. However, only six (19.4%) carriers had annual breast examinations as recommended by the NCCN guidelines. Among the female carriers, twenty (64.5%) underwent ovarian cancer surveillance at least once, and four (12.9%) did so more than three times, with none undergoing annual surveillance. Only one male carrier had a prostate examination for cancer surveillance. Mammography, breast ultrasounds, and clinical breast examinations were the most common methods used, and four carriers underwent annual breast MRIs (Table 3). Additionally, all four carriers who underwent ovarian cancer surveillance more than three times had gynecological examinations and CA-125 measurements, and three of them received transvaginal ultrasonography.

Figure 4.

Frequency of cancer surveillance.

Table 3.

Breast and ovarian cancer surveillance methods.

3.4. Reasons for Participating in Risk-Reducing Strategies

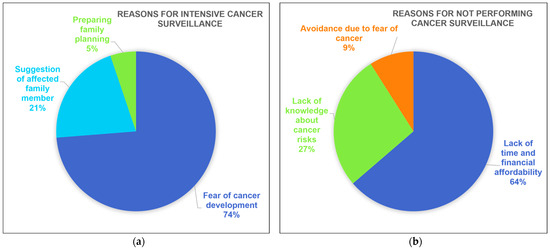

Among the female carriers who carried out breast cancer surveillance at least every 1–2 years, 14 (73.6%) responded that their participation was motivated by the fear of breast or ovarian cancer, 4 (21.0%) replied that they were persuaded by family members who had already developed cancer, and 1 (5.3%) stated that it was to prepare for family planning. On the other hand, female carriers who did not undergo cancer surveillance cited reasons such as a shortage of time or financial budget (n = 7, 63.6%), insufficient knowledge about cancer risks (n = 3, 27.2%), and avoidance due to fear of cancer (n = 1, 9.0%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Reasons for participating in risk-reducing strategies: (a) reasons for participating in intensive cancer surveillance; (b) reasons for not participating in cancer surveillance.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the patterns of cancer risk-reducing strategies recommended for unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with higher risks of breast and ovarian cancer. The high incidence rate of breast cancer in female carriers (32.3%) is concerning, particularly given the young mean age of 30 years. However, less than half of the carriers (41.9%) underwent breast examinations at least once every 2–3 years, and less than 20% underwent annual examinations.

Hong et al. [13] conducted a study on breast cancer screening rates among Korean women participating in the National Cancer Screening Program. They found that the screening rate had increased, reaching 63.1% in 2018; similarly, the National Health Insurance Service reported breast cancer screening rates of 63.2% in 2017 and 64.6% in 2021 [14]. The lower breast examination rate among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers compared to the general population is concerning, as these individuals have a significantly higher risk of developing breast cancer. This discrepancy underscores the importance of targeted recommendations and interventions specifically for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers to ensure they understand the necessity of regular breast examinations and adhere to appropriate screening guidelines.

The NCCN guidelines [7] and the Korean Clinical Practice Guideline for breast cancer [15] recommend annual mammography and breast MRIs for female BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. These guidelines suggest using both mammography and MRIs as screening methods for high-risk patients because breast MRIs have a higher sensitivity and lower specificity than mammography [16,17]. However, breast ultrasonography is not recommended for cancer screening, as it has not been proven to offer additional benefits in detecting breast cancer compared to mammography and MRI [18]. Despite these recommendations, our data showed that all female BRCA1/2 carriers who underwent breast cancer surveillance used breast ultrasonography (n = 13), while only a small number (n = 4) used breast MRIs. One reason for this discrepancy could be the lack of health insurance coverage for breast MRIs in Korea for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, which may result in significant out-of-pocket expenses for those who choose to undergo annual surveillance. Additionally, the study participants showed a relatively young average age (mean 30 years), which could mean that annual breast MRIs were less affordable for them, leading to a lower percentage of carriers receiving the recommended screening. Furthermore, younger carriers may have fewer comorbidities compared to older individuals and may be less aware of and attentive to cancer risks.

A significant finding of this study is the discrepancy in the rates of cancer surveillance among those who underwent surveillance once, more than three times, and annually. Understanding the underlying reasons for this variation is crucial. Barriers such as financial constraints, lack of awareness, and accessibility issues need to be addressed to improve compliance with recommended surveillance strategies. Furthermore, psychological factors may play a significant role in the decision to engage in risk-reducing strategies. Among carriers who did not undergo cancer surveillance, fear of cancer was a reason for avoidance, in addition to other factors such as lack of knowledge, lack of time, and financial constraints. Considering that about 30% of the enrolled carriers developed breast cancer, these findings emphasize the need for increased awareness about breast cancer surveillance and providing more affordable screening options for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Proactive measures, such as easing financial burdens through expanded health insurance coverage, enhancing educational initiatives to emphasize the importance of the early detection and prevention of cancer, raising awareness of the increased cancer risks linked to BRCA1/2 mutations, and strengthening access to and utilization of genetic counseling services, are required to encourage continuous and comprehensive surveillance among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers.

Bilateral mastectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy are the centerpieces of risk-reducing surgery for unaffected carriers. Bilateral mastectomy has been reported to reduce breast cancer risk by more than 90% in high-risk populations and BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, although the evidence regarding its survival benefits is lacking [19,20]. In contrast, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy has been shown to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer by 80% and the risk of breast cancer by 50% in BRCA2 mutation carriers, and it has been proven to have a survival benefit [21,22,23,24,25]. Based on this, genetic testing and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for the high-risk group of BRCA1/2 mutation carriers have been included in the Korean Health Insurance Service since 2013, increasing the proportion of carriers who have undergone risk-reducing surgery from 31.6% to 46.3% [26]. However, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy cannot be performed on women who have plans for childbearing and can lead to other morbidities such as osteoporosis or cardiac disease due to iatrogenic menopause. Therefore, careful counseling and adequate information must be provided to candidates to determine whether and when to undergo surgery.

According to previous reports, male carriers do not tend to undergo genetic testing; unaffected men underwent genetic testing for breast and ovarian cancer at one-tenth the rate of women, and patients with prostate cancer were less likely to undergo genetic testing (1%) compared to patients with breast and ovarian cancer (52.3%) [27]. However, male carriers of BRCA1/2 mutations carry a significant burden of cancer risk, which is comparable to female carriers. Male BRCA2 mutation carriers are recommended to undergo prostate cancer surveillance through measuring PSA, digital rectal exams, and prostate USG over 40 years of age, and this could also be considered for BRCA1 mutation carriers. In our study, the mean age of male carriers was 28 years, and only one male carrier (6.7%) among the fifteen unaffected male BRCA1/2 carriers was above 40, which is the age recommended for prostate cancer surveillance in the guidelines. Therefore, it is difficult to conclude whether male carriers participate in risk-reducing strategies. Considering that BRCA1/2 mutation carriers have a significantly increased risk of prostate cancer and that prostate cancer in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers is known to be more aggressive with a worse prognosis [28,29,30], it is crucial to emphasize the importance of prostate cancer surveillance to male carriers.

Lee et al. [26] analyzed the risk-reducing strategies used by both affected and unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in Korea. They found that older age was a significant factor associated with risk-reducing management among affected carriers with breast cancer, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was preferred over mastectomy as a risk-reducing procedure in both affected and unaffected carriers. In Lee’s study, 50% of unaffected carriers underwent cancer surveillance, and the percentages of carriers who underwent risk-reducing surgery or chemoprevention were 29.1% and 20.2%, respectively. In comparison, our data revealed that 41.9% of carriers underwent cancer surveillance examinations more than three times, which was comparable to Lee’s findings. However, only 3.2% of the carriers underwent risk-reducing surgery and 9.7% underwent chemoprevention in our study, which was significantly lower than in Lee’s data. This discrepancy might be due to the fact that the mean age of Lee’s study group was higher than ours and might have included a higher proportion of carriers who had already completed their pregnancy plans. Additionally, older individuals could be more aware of their cancer risks, leading to a higher percentage of carriers who had risk-reducing surgery or chemoprevention.

DiSilvestro et al. [31] investigated the risk-reducing strategies for ovarian cancer used by 104 female carriers of the BRCA1/2 mutation in the northeast United States. They reported that almost all (97%) of the carriers were offered risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, while only half were offered chemoprevention with oral contraceptive pills and ovarian cancer screening. However, 88% and 81% of the carriers who were offered oral contraceptive pills and ovarian cancer screening, respectively, were found to be taking the pills and undergoing screening. This demonstrates a higher proportion of participation in risk-reducing strategies than was observed in our study. These findings highlight the importance of providing education and suggesting risk-reducing strategies to BRCA1/2 mutation carriers.

In a study covering the risk-reducing strategies used by unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in the Western hemisphere [32], the percentage of carriers who chose to have a risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy varied from 0 to 54% and from 13 to 78%, respectively. In contrast, our study revealed that 0% (n = 0) and 3.2% (n = 1) of Korean carriers underwent mastectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy, which is significantly lower than the Western study. Lee et al. [26] also reported that 0% and 29% of unaffected carriers underwent bilateral mastectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy. According to a domestic study, the breast and ovarian cancer risks of BRCA1 mutation carriers up to the age of 70 were 72.1% and 24.6%, respectively, and 66.3% and 11.1%, respectively, in BRCA2 mutation carriers [5]. Despite the slight difference in cancer risks, the immense difference in the percentage of carriers who had risk-reducing surgery could be affected by age disparities between the studies, health insurance coverage, and cultural differences regarding body image and breast or ovarian preservation.

This study aimed to analyze the patterns of cancer risk-reducing strategies used by unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer who were included in the KOHBRA study. There are a few limitations to our study: a small number of carriers were included, which may lower the applicability of our study. Also, the relatively young age of the enrolled carriers may have meant that they had a lower cancer development risk and access to the healthcare system, leading to selection bias. These factors may make it challenging to generalize our findings to the larger Korean population. Additionally, there may be an inherent recall bias due to the survey-based approach.

Nevertheless, this study is significant as it identifies the actualities of implementing risk-reducing strategies with real-world clinical data and a relatively long follow-up time (8.6 years). Another strength of this study is that it is the first in Korea to actively follow up with healthy BRCA carriers and verify the incidence rates of breast and ovarian cancers. This proactive approach provides valuable insights into the real-world implementation of risk-reducing strategies and their outcomes in a Korean context. By tracking the health outcomes of these carriers over time, this study highlights the practical challenges and successes of applying preventive measures in a clinical setting, thereby informing future guidelines and interventions to better support BRCA mutation carriers in Korea.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study identified significant gaps in adherence to the recommended risk-reducing strategies among unaffected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Despite the limitations of a small sample size and the young age of enrolled carriers, addressing these gaps through enhanced educational initiatives, financial support, and improved access to genetic counseling is crucial to better manage cancer risks in this high-risk population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.K. and S.-W.K.; methodology, Z.K.; validation, J.M.R., S.-A.H. and S.-W.K.; formal analysis, D.K.; investigation, Z.K.; resources, J.M.R. and S.-A.H.; data curation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, Z.K.; visualization, D.K.; supervision, S.-W.K.; project administration, D.K.; funding acquisition, Z.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital (SCHBC 2016-08-017-001, approval date of 6 October 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the participants’ privacy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the support from Soonchunhyang University Research fund.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yun, M.H.; Hiom, K. Understanding the functions of BRCA1 in the DNA-damage response. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009, 37 Pt 3, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipak, L.; Watanabe, N.; Bessho, T. The role of BRCA2 in replication-coupled DNA interstrand cross-link repair in vitro. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006, 13, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedenson, B. BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathways and the risk of cancers other than breast or ovarian. MedGenMed 2005, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Hopper, J.L.; Barnes, D.R.; Phillips, K.A.; Mooij, T.M.; Roos-Blom, M.J.; Jervis, S.; van Leeuwen, F.E.; Milne, R.L.; Andrieu, N.; et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA 2017, 317, 2402–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.A.; Park, S.K.; Ahn, S.-H.; Son, B.H.; Lee, M.H.; Choi, D.H.; Noh, D.-Y.; Han, W.; Lee, E.S.; Han, S.K.; et al. The Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risks in Korea Due to Inherited Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: A Preliminary Report. J. Breast Cancer 2009, 12, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.C.; Domchek, S.; Parmigiani, G.; Chen, S. Breast cancer risk among male BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007, 99, 1811–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 3. 2024. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_bop.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Eisen, A.; Weber, B.L. Prophylactic mastectomy for women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations--facts and controversy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, J.R.; Risch, H.A.; Lubinski, J.; Moller, P.; Ghadirian, P.; Lynch, H.; Karlan, B.; Fishman, D.; Rosen, B.; Neuhausen, S.L.; et al. Reproductive risk factors for ovarian cancer in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations: A case-control study. Lancet Oncol. 2007, 8, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.A.; Park, S.K.; Ahn, S.H.; Lee, M.H.; Noh, D.Y.; Kim, L.S.; Noh, W.C.; Jung, Y.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, S.W. The Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer (KOHBRA) study: Protocols and interim report. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 2011, 23, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.; Kim, S.W. The korean hereditary breast cancer study: Review and future perspectives. J. Breast Cancer 2013, 16, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.; Seong, M.W.; Park, S.K.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, J.; Kim, L.S.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, S.Y.; Jeong, J.; Han, S.A.; et al. The prevalence and spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Korean population: Recent update of the Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer (KOHBRA) study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 151, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Lee, Y.Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.; Choi, K.S.; Jun, J.K.; Suh, M. Trends in Cancer Screening Rates among Korean Men and Women: Results of the Korean National Cancer Screening Survey, 2004-2018. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 53, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health Insurance Service. National Health Screening Statistical Yearbook 2022. Available online: https://www.nhis.or.kr/nhis/together/wbhaec07000m01.do?mode=view&articleNo=10840505&article.offset=0&articleLimit=10 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Korean Breast Cancer Society. The 10th Korean Clinical Practice Guideline for Breast Cancer. 2023, pp. 197–203. Available online: https://www.kbcs.or.kr/html/?pmode=recommendation (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Le-Petross, H.T.; Whitman, G.J.; Atchley, D.P.; Yuan, Y.; Gutierrez-Barrera, A.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Litton, J.K.; Arun, B.K. Effectiveness of alternating mammography and magnetic resonance imaging for screening women with deleterious BRCA mutations at high risk of breast cancer. Cancer 2011, 117, 3900–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, E.; Messersmith, H.; Causer, P.; Eisen, A.; Shumak, R.; Plewes, D. Systematic review: Using magnetic resonance imaging to screen women at high risk for breast cancer. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 148, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, C.C.; Luft, N.; Bernhart, C.; Weber, M.; Bernathova, M.; Tea, M.K.; Rudas, M.; Singer, C.F.; Helbich, T.H. Triple-modality screening trial for familial breast cancer underlines the importance of magnetic resonance imaging and questions the role of mammography and ultrasound regardless of patient mutation status, age, and breast density. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, L.C.; Sellers, T.A.; Schaid, D.J.; Frank, T.S.; Soderberg, C.L.; Sitta, D.L.; Frost, M.H.; Grant, C.S.; Donohue, J.H.; Woods, J.E.; et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation carriers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001, 93, 1633–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers-Heijboer, H.; van Geel, B.; van Putten, W.L.; Henzen-Logmans, S.C.; Seynaeve, C.; Menke-Pluymers, M.B.; Bartels, C.C.; Verhoog, L.C.; van den Ouweland, A.M.; Niermeijer, M.F.; et al. Breast cancer after prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauff, N.D.; Satagopan, J.M.; Robson, M.E.; Scheuer, L.; Hensley, M.; Hudis, C.A.; Ellis, N.A.; Boyd, J.; Borgen, P.I.; Barakat, R.R.; et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1609–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsopoulos, J.; Huzarski, T.; Gronwald, J.; Singer, C.F.; Moller, P.; Lynch, H.T.; Armel, S.; Karlan, B.; Foulkes, W.D.; Neuhausen, S.L.; et al. Bilateral Oophorectomy and Breast Cancer Risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djw177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domchek, S.M.; Friebel, T.M.; Singer, C.F.; Evans, D.G.; Lynch, H.T.; Isaacs, C.; Garber, J.E.; Neuhausen, S.L.; Matloff, E.; Eeles, R.; et al. Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. JAMA 2010, 304, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domchek, S.M.; Friebel, T.M.; Neuhausen, S.L.; Wagner, T.; Evans, G.; Isaacs, C.; Garber, J.E.; Daly, M.B.; Eeles, R.; Matloff, E.; et al. Mortality after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebbeck, T.R.; Kauff, N.D.; Domchek, S.M. Meta-analysis of risk reduction estimates associated with risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.G.; Kang, H.J.; Lim, M.C.; Park, B.; Park, S.J.; Jung, S.Y.; Lee, S.; Kang, H.S.; Park, S.Y.; Park, B.; et al. Different Patterns of Risk Reducing Decisions in Affected or Unaffected BRCA Pathogenic Variant Carriers. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 51, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.H.; Shevach, J.W.; Castro, E.; Couch, F.J.; Domchek, S.M.; Eeles, R.A.; Giri, V.N.; Hall, M.J.; King, M.C.; Lin, D.W.; et al. BRCA1, BRCA2, and Associated Cancer Risks and Management for Male Patients: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 1272–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Cancer risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999, 91, 1310–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leongamornlert, D.; Mahmud, N.; Tymrakiewicz, M.; Saunders, E.; Dadaev, T.; Castro, E.; Goh, C.; Govindasami, K.; Guy, M.; O’Brien, L.; et al. Germline BRCA1 mutations increase prostate cancer risk. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 1697–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, E.; Goh, C.; Olmos, D.; Saunders, E.; Leongamornlert, D.; Tymrakiewicz, M.; Mahmud, N.; Dadaev, T.; Govindasami, K.; Guy, M.; et al. Germline BRCA mutations are associated with higher risk of nodal involvement, distant metastasis, and poor survival outcomes in prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1748–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSilvestro, J.B.; Haddad, J.; Robison, K.; Beffa, L.; Laprise, J.; Scalia-Wilbur, J.; Raker, C.; Clark, M.A.; Lokich, E.; Hofstatter, E.; et al. Ovarian Cancer Risk-Reduction and Screening in BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers. J. Women’s Health 2024, 33, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainberg, S.; Husted, J. Utilization of screening and preventive surgery among unaffected carriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 1989–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).