Addressing Underscreening for Cervical Cancer among South Asian Women: Using Concept Mapping to Compare Service Provider and Service User Perspectives of Cervical Screening in Ontario, Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Participants

2.4. Demographics

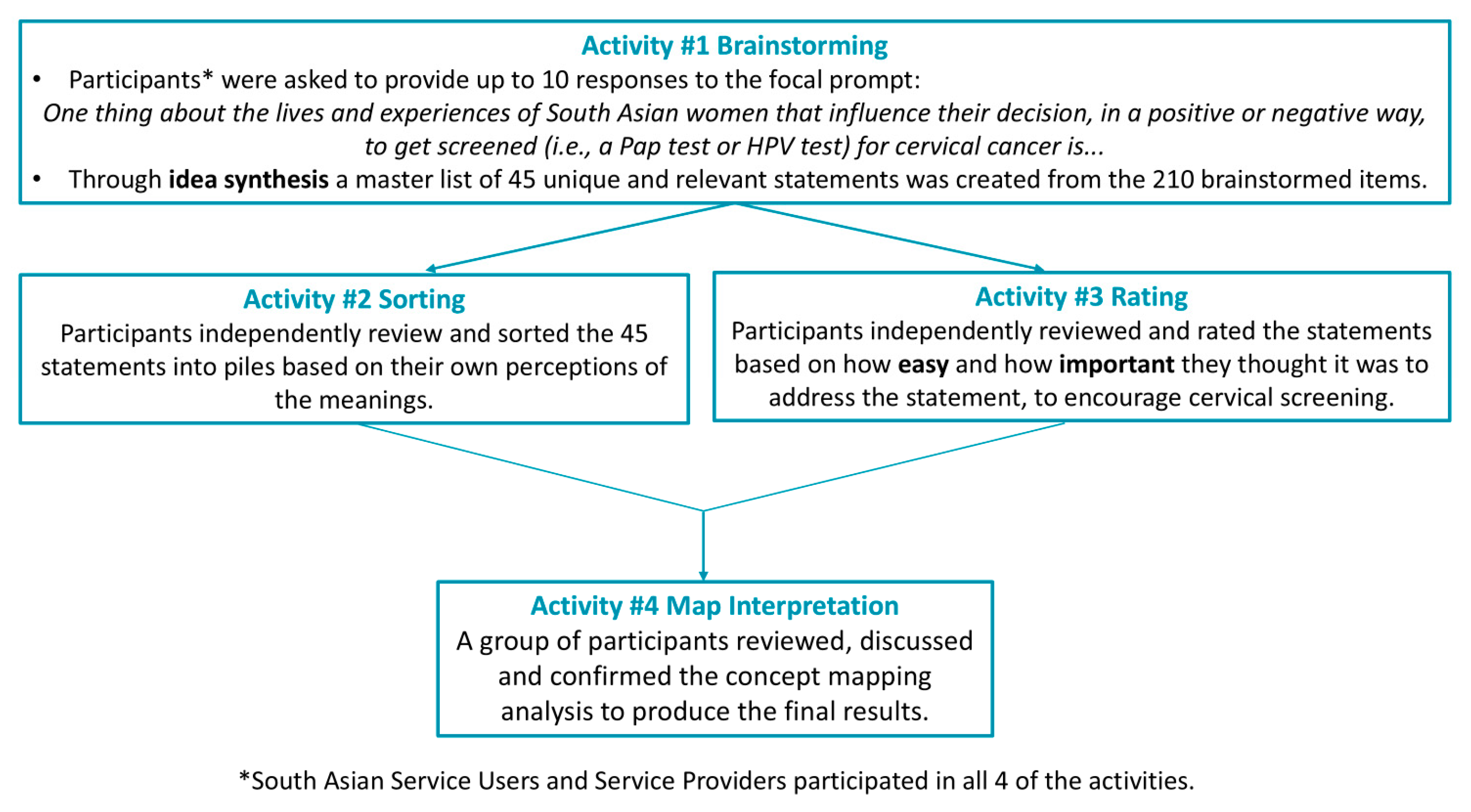

2.5. Concept-Mapping Activities

2.5.1. Brainstorming and Sorting to Create Thematic Clusters

2.5.2. Rating Activity to Understand Valuing of Statements and Themes

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Valuing of the Clustered Themes

2.6.2. Similarities and Differences Within Stratification of South Asian Service Users and Service Providers

2.6.3. Map Interpretation

3. Results

3.1. Participant Sample

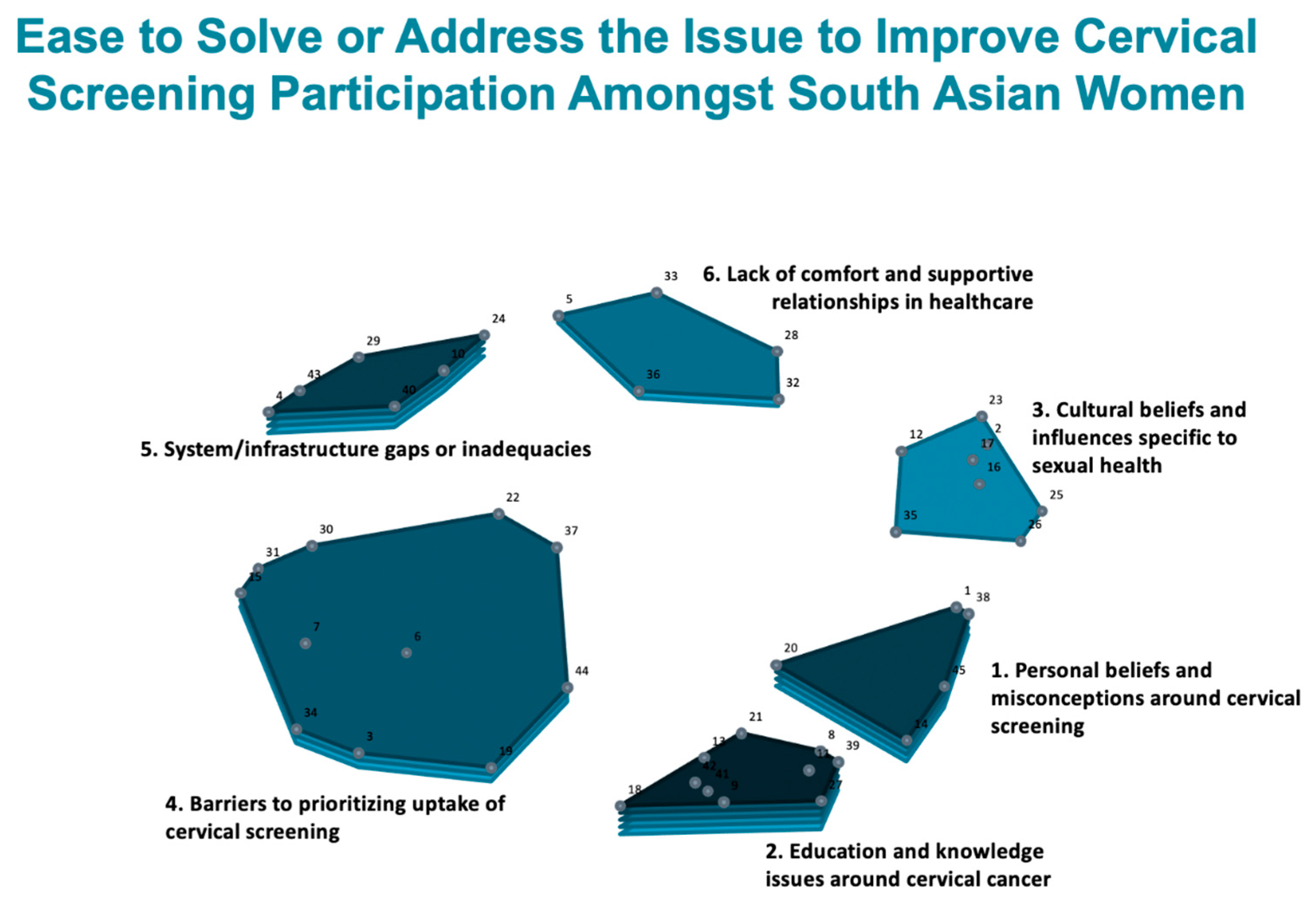

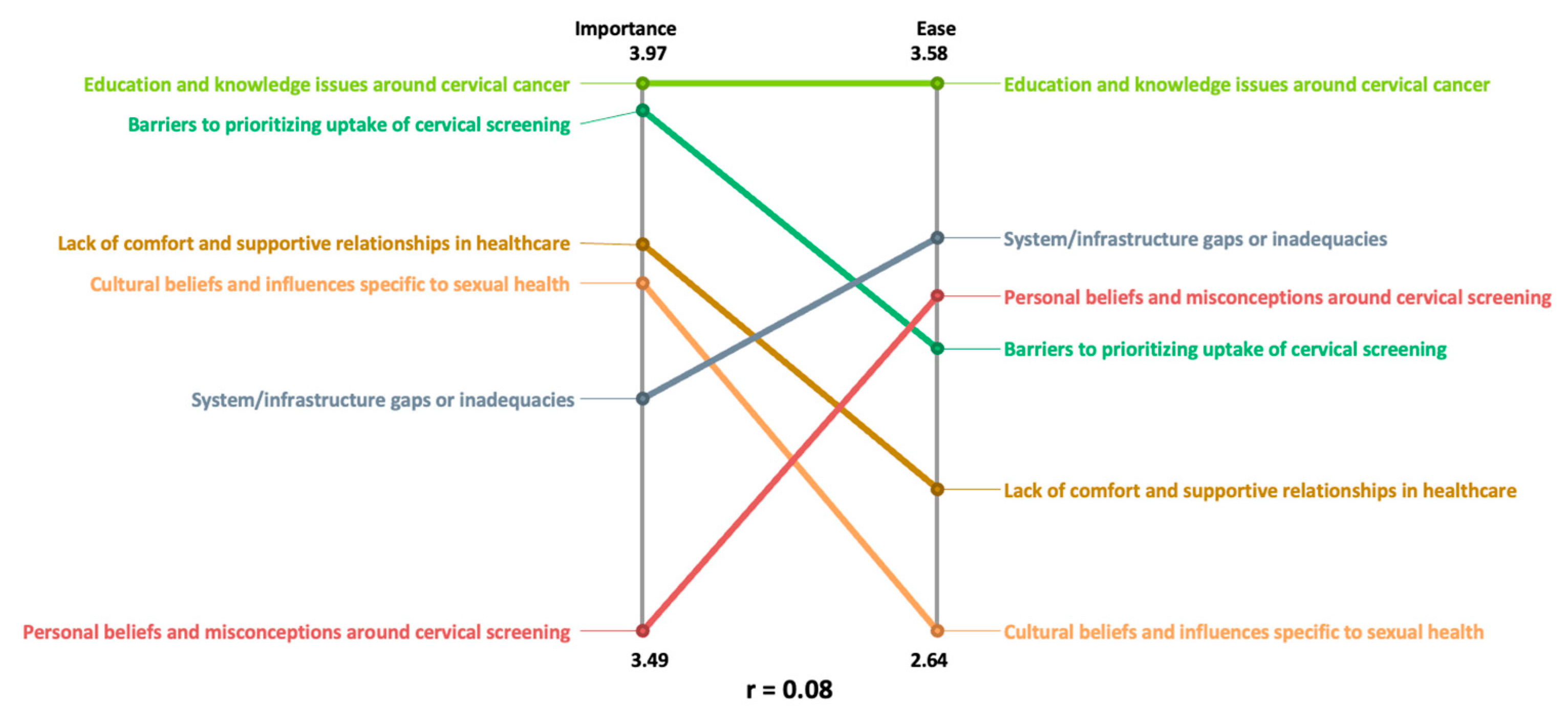

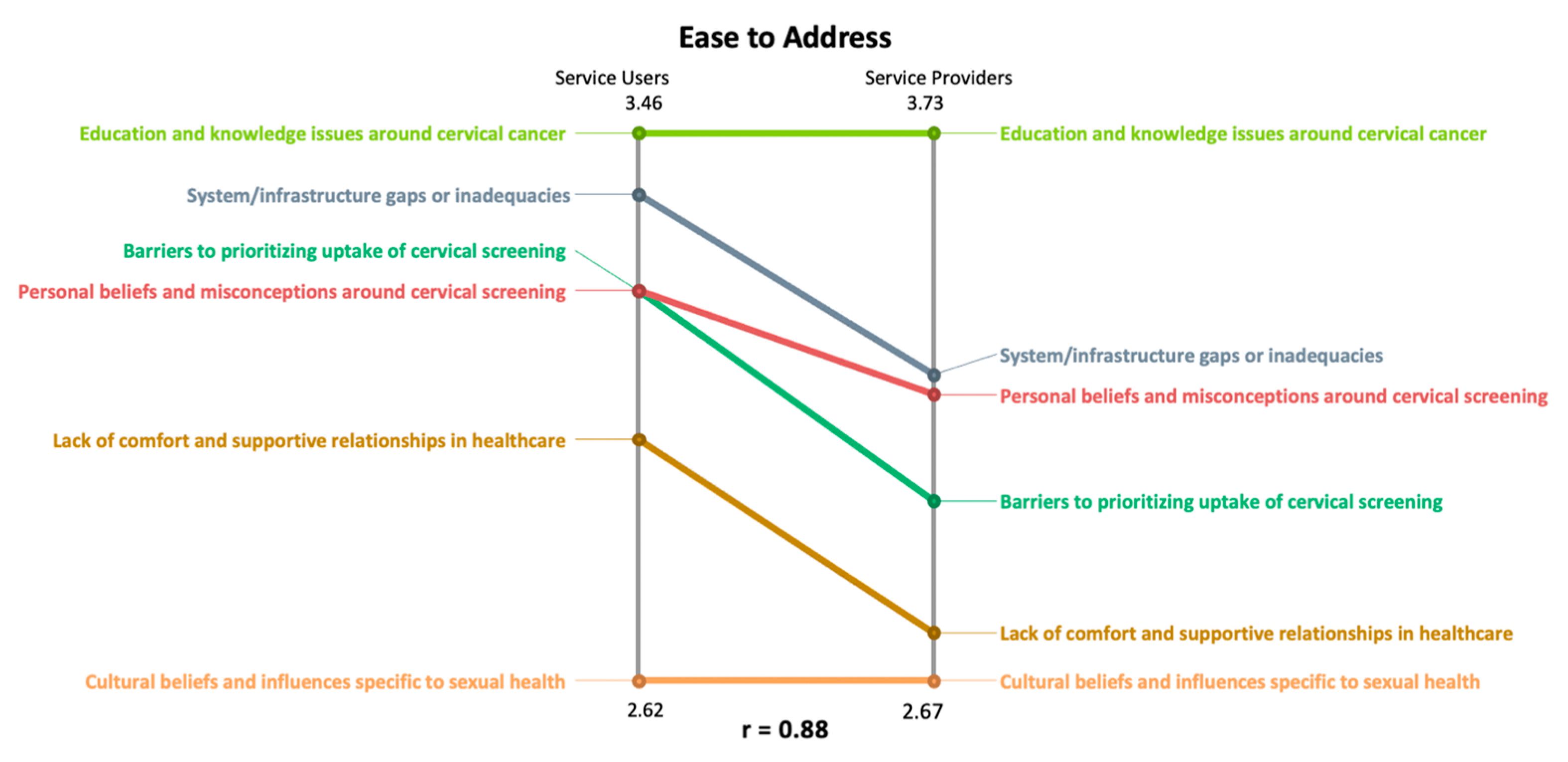

3.2. Rating Values for Clusters to Understand How Participants Thought About the Themes in Terms of Importance and Ease to Address

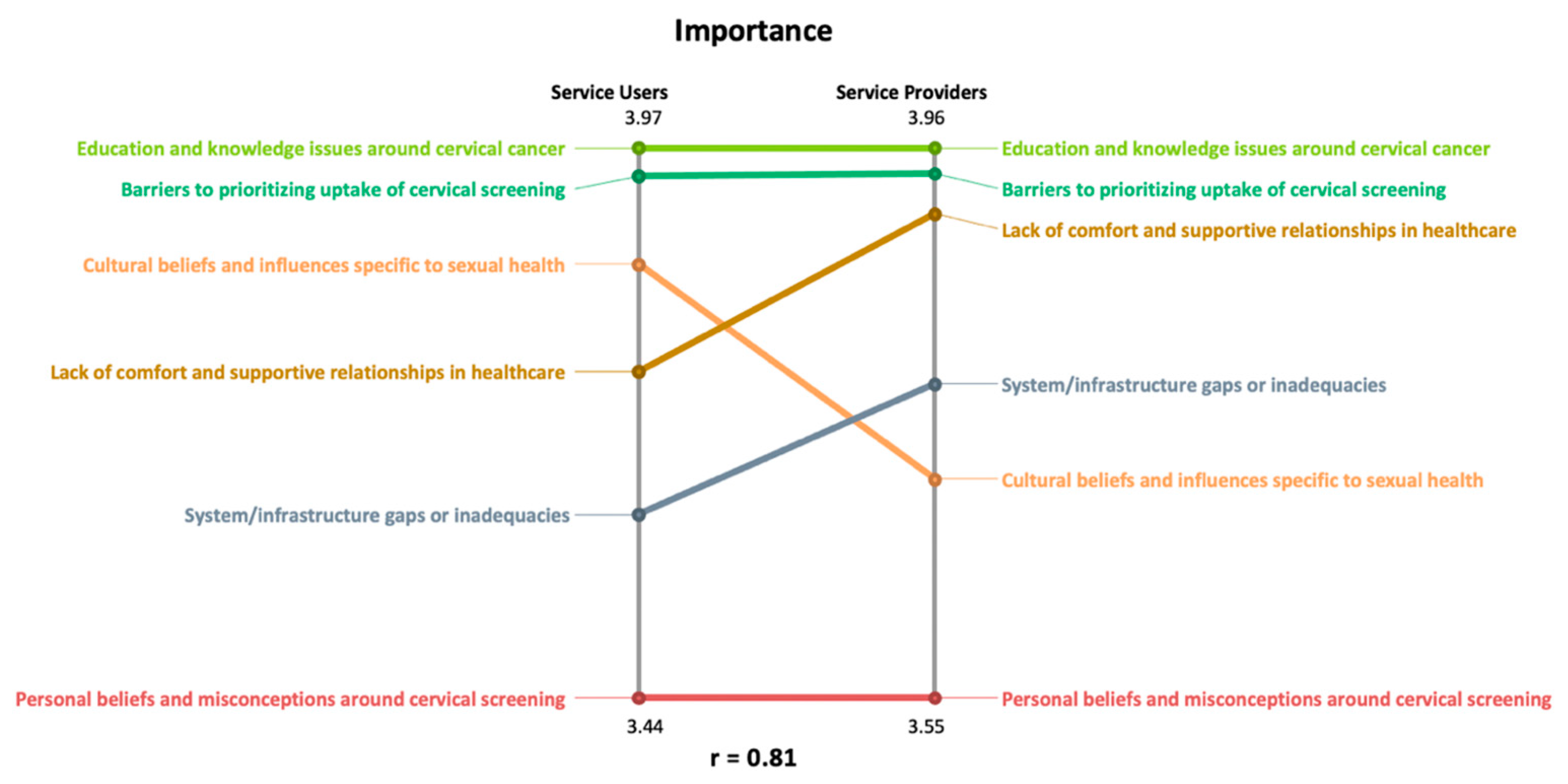

3.3. Using Pattern Matches to Understand the Importance- and Ease-Rating Differences and Similarities Amongst South Asian Service Users and Service Providers

4. Discussion

4.1. Addressing Current Issues Related to Underscreening for Cervical Cancer

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ontario Health Cancer Care Ontario. The Ontario Cancer Screening Performance Report 2020. Available online: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/cancer-care-ontario/programs/screening-programs/screening-performance-report-2020 (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Dunn, S.F.; Lofters, A.K.; Ginsburg, O.M.; Meaney, C.A.; Ahmad, F.; Moravac, M.C.; Nguyen, C.T.J.; Arisz, A.M. Cervical and Breast Cancer Screening After CARES: A Community Program for Immigrant and Marginalized Women. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107 (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Action Plan for the Elimination of Cervical Cancer in Canada 2020–2030. Available online: https://s22438.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Elimination-cervical-cancer-action-plan-EN.pdf/ (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Murphy, J.; Kennedy, E.B.; Dunn, S.; McLachlin, C.M.; Fung, M.F.K.; Gzik, D.; Shier, M.; Paszat, L. HPV Testing in Primary Cervical Screening: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2012, 34, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, J.; Kennedy, E.B.; Dunn, S.; McLachlin, C.M.; Fung, M.F.K.; Gzik, D.; Shier, M.; Paszat, L. Cervical Screening: A Guideline for Clinical Practice in Ontario. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2012, 34, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofters, A.K.; Moineddin, R.; Hwang, S.W.; Glazier, R.H. Low Rates of Cervical Cancer Screening Among Urban Immigrants. Med. Care 2010, 48, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofters, A.K.; Hwang, S.W.; Moineddin, R.; Glazier, R.H. Cervical cancer screening among urban immigrants by region of origin: A population-based cohort study. Prev. Med. 2010, 51, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofters, A.K.; Ng, R.; Lobb, R. Primary care physician characteristics associated with cancer screening: A retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada. Cancer Med. 2014, 4, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.J.; Wang, J.; Mazuryk, J.; Skinner, S.-M.; Meggetto, O.; Ashu, E.; Habbous, S.; Rad, N.N.; Espino-Hernández, G.; Wood, R.; et al. Delivery of Cancer Care in Ontario, Canada, During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e228855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, M.; Lofters, A. Muslim immigrant women’s views on cervical cancer screening and HPV self-sampling in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, J.; Moravac, C.; Ahmad, F.; Cleverly, S.; Lofters, A.; Ginsburg, O.; Dunn, S. “I want to save my life”: Conceptions of cervical and breast cancer screening among urban immigrant women of South Asian and Chinese origin. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaee-Pool, M.; Yargholi, F.; Jafari, F.; Ponnet, K. Exploring Iranian women’s perceptions and experiences regarding cervical cancer-preventive behaviors. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofters, A.; Vahabi, M.; Pyshnov, T.; Kupets, R.; Guilcher, S. Segmenting women eligible for cervical cancer screening using demographic, behavioural and attitudinal characteristics. Prev. Med. 2018, 114, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, J.; Ahmad, F.; Beaton, D.; Bierman, A.S. Cancer screening behaviours among South Asian immigrants in the UK, US and Canada: A scoping study. Health Soc. Care Community 2015, 24, 123–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, C.; Chan, C.W.; Chow, K.M.; Yang, S.; Luo, Y.; Cheng, H.; Wang, H. Understanding the cervical screening behaviour of Chinese women: The role of health care system and health professions. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 39, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cuevas, R.M.A.; Saini, P.; Roberts, D.; Beaver, K.; Chandrashekar, M.; Jain, A.; Kotas, E.; Tahir, N.; Ahmed, S.; Brown, S.L. A systematic review of barriers and enablers to South Asian women’s attendance for asymptomatic screening of breast and cervical cancers in emigrant countries. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottorff, J.L.; Balneaves, L.G.; Sent, L.; Grewal, S.; Browne, A.J. Cervical Cancer Screening in Ethnocultural Groups: Case Studies in Women-Centered Care. Women Health 2001, 33, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, S.; Bottorff, J.L.; Balneaves, L.G. A Pap Test Screening Clinic in a South Asian Community of Vancouver, British Columbia: Challenges to Maintaining Utilization. Public Health Nurs. 2004, 21, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, L.; Mcilfatrick, S. Exploring women’s knowledge, experiences and perceptions of cervical cancer screening in an area of social deprivation. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2011, 20, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Strategies to Maximize Participation in Cervical Screening in Canada: Catalogue of Interventions. Available online: https://s22457.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/CCIC-Participation-Strategies-Cervical-2010-EN.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Zestcott, C.A.; Blair, I.V.; Stone, J. Examining the presence, consequences, and reduction of implicit bias in health care: A narrative review. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2016, 19, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.; Trochim, W. Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devotta, K.; O’Campo, P.; Bender, J.; Lofters, A. Perceptions of cervical screening uptake amongst South Asian women: A concept mapping study. Manuscript being revised and resubmitted. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Devotta, K.; O’campo, P.; Bender, J.; Lofters, A.K. Important and Feasible Actions to Address Cervical Screening Participation amongst South Asian Women in Ontario: A Concept Mapping Study with Service Users and Service Providers. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 4038–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.G.; O’campo, P.; Peak, G.L.; Gielen, A.C.; McDonnell, K.A.; Trochim, W.M.K. An Introduction to Concept Mapping as a Participatory Public Health Research Method. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1392–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. How to do better case studies. In The SAGE Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Bickman, L., Rog, D.J., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; Chapter 8; pp. 254–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.; Rosas, S. Conversations About Group Concept Mapping: Applications, Examples, and Enhancements; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C. Knowledge, Barriers, and Motivators Related to Cervical Cancer Screening Among Korean-American Women. Cancer Nurs. 2000, 23, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redwood-Campbell, L.; Fowler, N.; Laryea, S.; Howard, M.; Kaczorowski, J. ‘Before You Teach Me, I Cannot Know’: Immigrant Women’s Barriers and Enablers With Regard to Cervical Cancer Screening Among Different Ethnolinguistic Groups in Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2011, 102, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.; So, W. The impact of community-based multimedia intervention on the new and repeated cervical cancer screening participation among South Asian women. Public Health 2020, 178, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Question | Options | Brainstorming (n = 72) |

|---|---|---|

| What best describes your role in this study? (options aggregated to reflect analysis categories) | South Asian Service User | 52 |

| Service Provider | 20 | |

| Have you ever had a Pap test? | Yes | 46 |

| No | 5 | |

| Unsure | 1 | |

| What is your age? | 21 to 30 | 8 |

| 31 to 40 | 19 | |

| 41 to 50 | 24 | |

| 51 to 60 | 13 | |

| 61 to 70 | 8 | |

| Do you identify as | Female | 71 |

| Male | 1 | |

| Other | 0 | |

| If you work in healthcare or in the community, how long have you been in this area of work? | 1 to 5 years | 5 |

| 6 to 10 years | 3 | |

| 11 to 15 years | 4 | |

| 16 to 20 years | 2 | |

| 20+ years | 4 |

| Participant Question | Options | Sorting (n = 11) | Rating (n = 25) | Map Interpretation (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you ever had a Pap test? | Yes | 10 | 20 | 4 |

| No | 1 | 5 | 0 | |

| Unsure | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| What is your age? | 21 to 30 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 31 to 40 | 5 | 10 | 2 | |

| 41 to 50 | 5 | 12 | 2 | |

| 51 to 60 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| 61 to 70 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Do you identify as | Female | 11 | 25 | 4 |

| Male | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Participant Question | Options | Sorting (n = 11) | Rating (n = 20) | Map Interpretation (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Check all that apply for roles you work in healthcare or in the community | Healthcare Provider Roles | 9 | 16 | 5 |

| Community Services Provider Roles | 13 | 23 | 7 | |

| What is your age? | 21 to 30 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 31 to 40 | 1 | 4 | 0 | |

| 41 to 50 | 6 | 7 | 3 | |

| 51 to 60 | 3 | 4 | 1 | |

| 61 to 70 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Choose not to answer | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Do you identify as | Female | 11 | 20 | 5 |

| Male | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| If you work in healthcare or in the community, how long have you been in this area of work? | 1 to 5 years | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 to 10 years | 4 | 8 | 3 | |

| 11 to 15 years | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| 16 to 20 years | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 20+ years | 3 | 4 | 1 | |

| If you work in healthcare or in the community, what percentage of the population that you serve is South Asian? | 9% to 85% | 9% to 85% | 9% to 85% | |

| Cluster | Statements | Importance Average Cluster Rating Value | Ease to Address Average Cluster Rating Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1: personal beliefs and misconceptions around cervical screening | The belief that you should not “touch” things or go under the knife (meaning any medical procedure) because it brings more harm than good. | moderate (3.49) | moderate (3.22) |

| A woman’s belief that cervical cancer screening is not necessary if you have only had one sexual partner. | |||

| Women may view a Pap test as a dirty procedure where you may bleed afterwards. | |||

| The belief that if a cervical cancer diagnosis is your fate or destiny, there is no reason to get screened. | |||

| South Asian women will not get screened because they think they cannot get cervical cancer. | |||

| Cluster 2: education and knowledge issues around cervical cancer | Women believing that a Pap test can lead to an infection | high (3.97) | moderate (3.58) |

| A woman’s lack of understanding and education around cervical cancer | |||

| If a woman believes that cervical cancer is not a severe condition, this can discourage them from getting screened | |||

| Education about cervical cancer is needed for men in South Asian households | |||

| Not enough media coverage of cervical cancer screening within the South Asian community | |||

| Preventative care is not well understood by South Asian women | |||

| Women believe that if they have an HPV vaccine, they do not need to be screened for cervical cancer | |||

| Belief that you only have to worry about cervical cancer if you have a problem with your menstruation | |||

| Women may not know what a Pap test involves | |||

| Women may not know the purpose of a Pap test | |||

| Cluster 3: cultural beliefs and influences specific to sexual health | Cultural expectations or pressures that the idea of “modesty” prevents women in the South Asian community from getting screened for cervical cancer. | high (3.79) | low (2.64) |

| Men in South Asian households make decisions about females getting screened. | |||

| Negative cultural beliefs behind gynecologist visits leads to South Asian women feeling shame when booking appointments. | |||

| South Asian women are not comfortable to discuss their sexual history. | |||

| South Asian women may be worried about their family finding out they are sexually active. | |||

| Sex is a taboo topic amongst South Asians. | |||

| Any tests related to sex can be considered dirty. | |||

| Cervical cancer screening is not openly discussed in the South Asian culture. | |||

| Cluster 4: barriers to prioritizing uptake of cervical screening | Women do not go to the doctor unless they are having an issue. | high (3.94) | moderate (3.13) |

| Lack of access to cervical cancer screening information shared by trusted sources. | |||

| Pap test appointments are viewed as time consuming. | |||

| Women need reminders to know when they are due for cervical cancer screening. | |||

| Pap tests can feel painful. | |||

| Prior negative experience with a Pap test discourages South Asian women from getting screened. | |||

| South Asian women may prioritize looking after their families over their own health. | |||

| South Asian women may be too busy with their jobs or careers to take care of their own health. | |||

| Women are afraid to find out if they have cancer. | |||

| Women hear other women share negative experiences about getting a Pap test. | |||

| South Asian women will only get screened when symptoms arise. | |||

| Cluster 5: system/infrastructure gaps or inadequacies | Appointments are not available at times that are convenient for patients. | moderate (3.69) | moderate (3.32) |

| Needing to communicate with healthcare providers in English is a barrier for South Asian women to be screened for cervical cancer. | |||

| Not having a healthcare provider of a similar cultural background makes intimate tests, such as a Pap test, uncomfortable. | |||

| Foreign-trained physicians may not encourage their patients to do cancer screening, as preventative care may not have been common in their home countries. | |||

| Family doctor does not encourage cervical cancer screening during appointment. | |||

| Women do not have a family doctor. | |||

| Cluster 6: lack of comfort and supportive relationships in healthcare | Women do not feel comfortable with their healthcare provider. | high (3.83) | low (2.89) |

| Women may be shy to have an examination in that area of their body. | |||

| Lack of support from family members to go and get screened. | |||

| Lack of support from friends to go and get screened. | |||

| Women may be uncomfortable with going to the doctor in general |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Devotta, K.A.; O’Campo, P.; Bender, J.L.; Lofters, A.K. Addressing Underscreening for Cervical Cancer among South Asian Women: Using Concept Mapping to Compare Service Provider and Service User Perspectives of Cervical Screening in Ontario, Canada. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 6749-6766. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31110498

Devotta KA, O’Campo P, Bender JL, Lofters AK. Addressing Underscreening for Cervical Cancer among South Asian Women: Using Concept Mapping to Compare Service Provider and Service User Perspectives of Cervical Screening in Ontario, Canada. Current Oncology. 2024; 31(11):6749-6766. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31110498

Chicago/Turabian StyleDevotta, Kimberly A., Patricia O’Campo, Jacqueline L. Bender, and Aisha K. Lofters. 2024. "Addressing Underscreening for Cervical Cancer among South Asian Women: Using Concept Mapping to Compare Service Provider and Service User Perspectives of Cervical Screening in Ontario, Canada" Current Oncology 31, no. 11: 6749-6766. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31110498

APA StyleDevotta, K. A., O’Campo, P., Bender, J. L., & Lofters, A. K. (2024). Addressing Underscreening for Cervical Cancer among South Asian Women: Using Concept Mapping to Compare Service Provider and Service User Perspectives of Cervical Screening in Ontario, Canada. Current Oncology, 31(11), 6749-6766. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31110498