Abstract

We present the case of a 27-year-old man who was admitted with new-onset acute heart failure. The echocardiogram revealed biventricular dilatation with a severely reduced systolic function. A genetic study identified a truncated variant of the filamin-C (FLNC) gene. Since the systolic function did not improve under heart failure guideline-directed medical therapy, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was placed. After two years, the patient is currently being considered for epicardial ventricular tachycardia (VT) ablation due to the failure of appropriate therapies for monomorphic VT despite recovery of the left ventricular (LV) systolic function. Filamin C truncating variants have been recognized as one cause of an overlapping phenotype in dilated and arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies. These patients typically present with a mildly reduced LV ejection fraction (LVEF), with or without dilatation, and extensive myocardial fibrosis, which heightens the risk of complex ventricular arrhythmias (VAs). Our patient presented a combined phenotype with biventricular dilated cardiomyopathy with a severely reduced LVEF at an unusual young age, as well as an increased incidence of VAs. With this clinical case, we aim to highlight the importance of genetic evaluation in dilated cardiomyopathy, as it can be decisive in its orientation and, consequently, in its prognosis.

Introduction

Filamin-C (FLNC) truncating mutation is recognized as a cause of overlapping, dilated, and arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. This phenotype is characterized by a late-onset mild left ventricular (LV) systolic disfunction, which is typically diagnosed in the fourth decade, and extensive myocardial fibrosis. This puts these patients at an increased risk for complex ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) and sudden cardiac death (SCD), which have been shown to be independent of LV ejection fraction (LVEF) [1,2,3,4].

For that reason, the most recent guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology recommend the placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in the presence of a FLNC gene mutation and another risk factor for VAs, even with a LVEF of 36 to 50% [5].

This case report illustrates the importance of genetic evaluation for the diagnosis and treatment of dilated cardiomyopathy.

Case Description

A 27-year-old man was admitted to the emergency room with progressive breathlessness over the past two weeks, culminating in acute pulmonary edema. There were no other significant findings in the physical examination. He denied having chest pain or flu-like symptoms. The patient was obese (Body Mass Index of 47.8 kg/m2), a smoker, and had significant alcohol consumption (50 g/day), as well as a family history of SCD and heart transplantations in several maternal cousins.

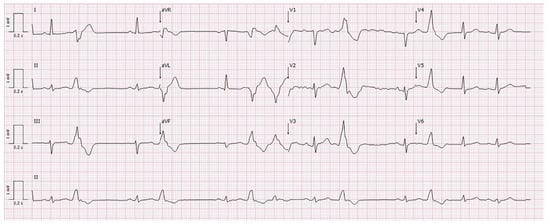

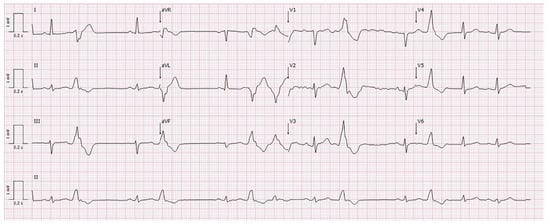

The electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed sinus rhythm with borderline low-voltage QRS, flattened T waves in the inferior and lateral leads, and polymorphic premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) (Figure 1). Blood analysis showed elevated pro-brain natriuretic peptide (2616 pg/mL), negative high-sensitivity troponin T (0.05 ng/mL), only a mild elevation of inflammatory parameters (leukocytosis of 14,630/μL and C-reactive protein of 1.4 mg/dl), normal creatine kinase, and negative infectious and autoimmune studies. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed severe biventricular dilatation (LV end-diastolic volume of 103 mL/m2) and systolic dysfunction (LVEF of 20%, right ventricular fractional area change of 17%) due to global hypokinesia.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram at admission showing polymorphic premature ventricular contractions, borderline low voltage, and flattened T waves in the inferior and lateral leads.

Etiological Investigation

The etiology was investigated using computed tomography angiography, which excluded coronary-significant epicardial disease. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) was not possible due to the patient’s obesity. A 24-h Holter monitoring revealed very frequent polymorphic PVCs (89/h, 2.6% load), with no complex VAs or other conduction disturbances. Given his young age and family history, genetic testing was requested, which revealed a likely pathogenic mutation in the FLNC gene (c.5520T>A p.Tyr1840*), a truncated protein. Thus, familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with FLNC gene mutation was diagnosed.

A family genetic evaluation was initiated. Until now, the FLNC gene mutation has been identified in several family members, including the patient’s sister (28 years old) and mother (60 years old), who both have already received an ICD. Both have normal ECG and TTE, and the mother’s CMR showed no late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) despite frequent polymorphic PVCs without complex VAs. The sister’s Holter monitoring revealed no complex or frequent VAs; however, she is still awaiting a CMR for further cardiac evaluation.

Clinical Evolution

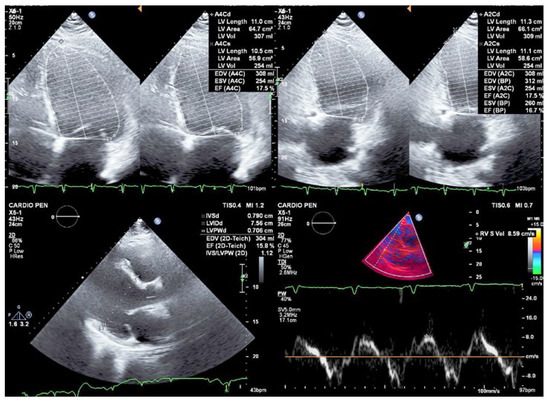

Despite receiving maximum tolerated guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for heart failure (with sacubitril/valsartan 97/103 mg twice a day, bisoprolol 15 mg, spironolactone 50 mg, and dapagliflozin 10 mg), the systolic function did not recover (LVEF of 17%) (Figure 2). Therefore, evaluation for heart transplantation was initiated, although with poor compliance from the patient. Given the increased risk of SCD, an ICD was placed for primary prevention. After approximately one year of follow-up, at the age of 28, the patient received the first appropriate shock for sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT).

Figure 2.

Transthoracic echocardiogram showing severe biventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction of 17%, S’ 8.6 cm/s) due to global hypokinesia.

After two years of GDMT and cessation of alcohol consumption, the patient’s LVEF improved. However, despite receiving appropriate ICD shocks, he had multiple recurrences of VT. Amiodarone was added to the GDMT for heart failure following the first ICD shock, and bisoprolol was titrated up to 20 mg. Despite these adjustments, the VT recurred. Endocardial ablation of VT was attempted; however, substrate mapping failed to identify areas of scar or abnormal potentials, and programmed ventricular stimulation with and without isoproterenol failed to induce VAs. Therefore, the patient is now being considered for an epicardial approach. Since the patient remains obese, despite evaluation by a nutritionist and a psychologist, it is still impossible to perform a CMR, which would allow us to assess the presence, extent, and location of LGE.

Discussion

FLNC is an actin cross-linking protein expressed in the adherens junctions of both skeletal muscle and cardiomyocytes that contributes to the maintenance of cellular integrity [1]. Mutations in the FLNC gene that result in a truncated form of the protein have been identified as autosomal dominant DCM-causing variants with a higher risk of major arrhythmic events than other etiologies of DCM, regardless of LVEF [2].

Patients with FLNC cardiomyopathy show a heterogeneous phenotypic presentation extending from non-dilated arrhythmogenic forms to typical DCM, with frequent overlapping. The mean age at diagnosis ranges from 41 to 49 years, with patients with arrhythmogenic phenotypes presenting later than those with DCM phenotypes (48 vs. 40 years) [1,2,3,4]. Thus, when evaluating relatives, a longer follow-up period may be required to ensure an accurate diagnosis and timely intervention, if necessary [1].

These patients typically present with mildly reduced LVEF with or without LV dilatation, as well as extensive myocardial fibrosis, which increases the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias regardless of the severity of LV dysfunction [1,3,4]. In fact, studies have found a 5–10% risk of SCD in patients with truncating variants of FLNC [5]. In addition to the previous recommendations for placing an ICD on patients with LVEF ≤35%, it is now also recommended in the presence of FLNC gene mutation and another risk factor for VA (such as unexplained syncope, LGE on CMR, or inducible sustained monomorphic VT at programmed electrical stimulation), even in patients with a LVEF of 36 to 50% [5].

Other recently described arrhythmic risk markers include low QRS voltage and T wave inversion in the inferolateral and lateral leads on the ECG, as well as nonischemic LV LGE on CMR (or myocardial fibrosis on postmortem analysis) [1,2,3,4]. Specifically, a subepicardial ring-like pattern of LGE was identified as a distinctive characteristic of both FLNC and desmoplakin genotypes [3].

Our patient presented with a biventricular DCM with a severe reduction of the LVEF at an unusually young age. Despite not knowing the possible extent of myocardial fibrosis, the presence of only borderline electrocardiographic risk criteria, and the absence of complex VAs during hospitalization and on 24-h monitoring, life-threatening VAs occurred early in the course of the disease. In fact, one year after the diagnosis of FLNC cardiomyopathy, at the age of 28, the patient had already received an appropriate shock for sustained monomorphic VT.

Although it seems possible that alcohol consumption may have accelerated the phenotypic expression of the disease because the patient was the youngest in his family to present with it and that cessation of alcohol consumption may have had an impact on the recovery of systolic function, clinical presentation and extensive family history support the diagnosis of early-onset FLNC cardiomyopathy.

Conclusions

This case highlights the importance of genetic evaluation of DCM because it can influence the orientation and, consequently, the prognosis not only of index patients but also of their families.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Catarina Ribeiro Carvalho and Marta Ribeiro Bernardo. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Catarina Ribeiro Carvalho and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

The authors confirm that this is a retrospective case report using de-identified data; therefore, consent from the patient is not required.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Celeghin, R.; Cipriani, A.; Bariani, R.; Bueno Marinas, M.; Cason, M.; Bevilacqua, M.; et al. Filamin-C variant-associated cardiomyopathy: A pooled analysis of individual patient data to evaluate the clinical profile and risk of sudden cardiac death. Heart Rhythm. 2022, 19, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, M.M.; Lorenzini, M.; Pavlou, M.; Ochoa, J.P.; O’Mahony, C.; Restrepo-Cordoba, M.A.; et al.; European Genetic Cardiomyopathies Initiative Investigators Association of Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction Among Carriers of Truncating Variants in Filamin C With Frequent Ventricular Arrhythmia and End-stage Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augusto, J.B.; Eiros, R.; Nakou, E.; Moura-Ferreira, S.; Treibel, T.A.; Captur, G.; et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic left ventricular cardiomyopathy: A comprehensive genotype-imaging phenotype study. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2020, 21, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammani, A.; Kayvanpour, E.; Bosman, L.P.; Sedaghat-Hamedani, F.; Proctor, T.; Gi, W.T.; et al. Predicting sustained ventricular arrhythmias in dilated cardiomyopathy: A meta-analysis and systematic review. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 1430–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbelo, E.; Protonotarios, A.; Gimeno, J.R.; Arbustini, E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Basso, C.; et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies: Developed by the task force on the management of cardiomyopathies of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3503–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2024 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0