Abstract

Evidence suggests that gut dysbiosis may contribute to acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and its complications, including reduced physical performance and muscle weakness. We hypothesized that probiotic supplementation could improve muscle strength during post-AMI recovery. In a randomized, controlled, triple-blind clinical trial, adults and older adults undergoing myocardial revascularization received either a multistrain probiotic formulation (Lacticaseibacillus paracasei, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus, Lacticaseibacillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacterium lactis) or placebo for 90 days. The primary outcome was handgrip strength (HGS). Forty-five participants completed the study. No significant between-group differences were observed in the main analysis. However, in an exploratory subgroup of men aged 50 years and older with low baseline HGS (n = 30), probiotic supplementation led to a greater improvement in non-dominant HGS after 90 days compared with placebo (mean difference: +4.6 kg/f; p = 0.04). A baseline-adjusted ANCOVA confirmed a significant baseline-by-treatment interaction for the non-dominant hand (β = +0.33; 95% CI: +0.02 to +0.62; p = 0.038), indicating greater improvements among participants with lower initial strength. Although the primary analysis yielded null results, these exploratory findings indicate a potential benefit of probiotic supplementation in a clinically vulnerable subgroup of revascularized men with low baseline strength. Larger and prospectively powered trials are warranted to confirm these observations. Trial registration: RBR-6ztyb7.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain the foremost cause of morbidity and mortality globally, including in Brazil [1,2,3,4]. The Global Burden of Disease study reports a 3.4% reduction in the mortality rate attributable to ischemic heart disease—comprising coronary artery disease (CAD), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and heart failure—from 1980 to 2021. Conversely, there has been a marked 71.3% increase in AMI hospitalizations within Brazil’s public health system over the same period [4].

CAD is characterized by significant narrowing or occlusion of the epicardial coronary arteries, typically greater than 50% stenosis [5]. Atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory process, is the predominant etiology, which can progress silently to clinical manifestations such as stable and unstable angina, as well as AMI, influenced by a myriad of both modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors [6,7].

Recent findings highlight gut dysbiosis as a critical factor in the pathophysiology of CVD. Sedentary lifestyles, tobacco use, diets high in saturated fats and refined carbohydrates, metabolic disorders, and antibiotic exposure have all been implicated in altering the gut microbiota’s composition and functionality. Such dysbiotic states promote the translocation of microbial entities, notably lipopolysaccharide (LPS), contributing to low-grade endotoxemia, systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and the acceleration of atherogenesis [8,9,10]. Moreover, dysbiosis alters the synthesis of microbial metabolites, including trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and secondary bile acids, which are increasingly recognized for their roles in cardiometabolic health [11,12].

The implications of the gut microbiota extend beyond cardiovascular health; it also profoundly affects skeletal muscle mass, metabolism, and functionality. Dysbiosis may play a role in sarcopenia by augmenting intestinal permeability and circulating endotoxins, disrupting mitochondrial bioenergetics, and modifying amino acid availability and anabolic signaling pathways [13,14]. These mechanisms may elucidate the observed associations between CVD and diminished muscle strength and mass, critical predictors of functional capacity, frailty, and overall clinical outcomes [13,14,15]. Handgrip strength (HGS), a simple and effective non-invasive metric, serves as a valuable tool for assessing muscle strength and diagnosing sarcopenia while evaluating patient functionality [15].

Patients recovering from AMI are particularly susceptible to accelerated declines in muscle strength attributed to factors such as prolonged immobilization, systemic inflammation, metabolic stress, and disturbances in the gut–muscle axis [16]. Post-cardiovascular event muscle strength reduction correlates with poor functional recovery, increased dependency during rehabilitation, and adverse clinical outcomes, underscoring its significance in the post-AMI context [17].

Interventions targeting the gut microbiota, especially through probiotics, have garnered attention as a potential strategy to counteract the adverse ramifications of dysbiosis on cardiovascular and muscular health. Probiotics may restore microbial diversity, enhance intestinal barrier function, mitigate systemic inflammation, and modulate cardiometabolic-risk-associated microbial metabolites [18,19]. Despite this growing interest in microbiome-targeted interventions for CVD, there is a notable lack of clinical trials investigating the effects of probiotic supplementation on muscle strength specifically in AMI recovery patients, rendering this a critical and underexplored research avenue [9,20].

Strains from the Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium genera have demonstrated the capacity to enhance gut barrier integrity, SCFA signaling, and systemic inflammatory responses [21,22], all of which are pertinent to the gut–muscle axis. Recent studies indicate that supplementation with Lactobacillus spp. may bolster muscle strength and mass via anti-inflammatory, mitochondrial, and metabolic pathways [23,24]. Furthermore, probiotic formulations enriched with these genera have been linked to improved muscle function in both clinical and preclinical settings [23,25], reinforcing their potential role as adjunct therapies during cardiovascular recovery.

Therefore, the objective of the present randomized, controlled, triple-blind clinical trial is to assess the impact of probiotic supplementation on HGS and anthropometric indicators of muscle mass in patients undergoing myocardial revascularization following AMI. We hypothesize that probiotic supplementation will enhance muscle strength during the post-AMI recovery phase.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study focused on adults aged 20 years and older, encompassing both sexes, who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) due to ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction related to atherosclerotic CAD. These patients were treated at the Dr. and Mrs. Goldsby King Evangelical Hospital in Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, from November 2021 to October 2023.

Exclusion criteria comprised a history of gastrointestinal disorders (including malignancies and inflammatory bowel diseases), chronic kidney disease necessitating dialysis, adherence to non-standard diets (such as vegetarian, gluten-free, lactose-free, or macrobiotic), and known food intolerances or allergies (e.g., lactose intolerance, celiac disease). Additionally, patients with current or recent (within three months) usage of medications or supplements that could influence gut microbiota or appetite (such as antibiotics, laxatives, or appetite suppressants—except for prophylactic antibiotics related to surgery), regular use of antispasmodics or antacids, prior use of dietary fiber supplements, prebiotics, probiotics, or symbiotics within the previous three months, as well as those with alcohol or illicit drug dependence, were excluded. Pregnant or lactating women and indigenous individuals were also not considered for participation.

Eligible participants were invited to join the study and provided informed consent prior to enrollment. During the supplementation phase, participants were directed to abstain from alcohol consumption, refrain from ingesting foods high in prebiotics, probiotics, or synbiotics, and avoid intense physical activity. Discontinuation criteria included the initiation of antibiotics due to infection during the study period or failure to consume the supplement for more than two consecutive days.

2.2. Study Design and Institutional Review Board Statement

A randomized, parallel-arm, placebo-controlled, triple-blind clinical trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Grande Dourados (UFGD), Brazil. This trial is also registered on the Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry (ReBEC) platform, identified as RBR-6ztyb7. To guide the reporting of this study, the CONSORT checklist was followed (Supplementary Material) [26].

Randomization was implemented using a block stratification method, considering the presence or absence of type 2 diabetes as a covariate. Each block was allocated a set of random numbers generated via an external researcher utilizing the website https://randomizer.org (accessed on 19 July 2021). Each sequence consisted of eight unique digits to prevent repetition. The generation of random codes and the distribution of the intervention materials (both the probiotic supplement and placebo) were managed by an independent researcher with no involvement in other aspects of the study. The sachets were designed to be opaque and identical in appearance, flavor, and color, with proper sealing by the supplier to ensure that participants remained unaware of their group allocation, thereby maintaining allocation concealment.

The researchers conducting recruitment, monitoring, data collection, and statistical analysis were granted access solely to the randomization list bearing the numerical codes. This process upheld the trial’s triple-blind design, as the assignment of each code to either the PRO or PLA group was only disclosed after the completion of statistical analyses.

2.3. Interventions

The participants in the PRO group received a package containing individual sachets, each containing 1 g of a specific probiotic blend: Lacticaseibacillus paracasei CCT 7861, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus CCT 7863, Lacticaseibacillus acidophilus CCT 7947, and Bifidobacterium lactis CCT 7858 (1 × 109 CFU/day/strain). This dosage aligns with prevalent protocols in clinical studies assessing the impact of probiotic supplementation on functional outcomes in adult populations [27].

The probiotics were subjected to freeze-drying and microencapsulation with a dual-layer coating designed for stability under conditions up to 60 °C and a pH of 2.5, eliminating the need for refrigeration. This formulation boasted a shelf life of 24 months, utilizing microcrystalline cellulose as the excipient. In contrast, the PLA group received sachets containing maltodextrin at a dose of 1 g/day. Participants were instructed to dissolve the contents of one sachet in 100 mL of water at room temperature and consume it prior to a main meal once daily for a duration of 90 days. The intervention period was chosen in accordance with literature indicating that notable enhancements in muscle strength due to probiotic supplementation are typically observable in trials extending beyond 12 weeks [20].

All participants were required to document their daily supplement intake using forms provided by the research team. Compliance was reinforced with weekly telephone check-ins to monitor adherence to the prescribed storage conditions (dry, ventilated, and shielded from sunlight), which are essential to maintain viability at ambient temperatures, and to identify any potential adverse effects experienced by the participants.

2.4. Sample Size

A systematic review pertinent to this investigation encompassed three studies that evaluated muscle strength, employing HGS as the primary outcome measure. Notably, only one study within this review focused on the effects of multiple probiotics in individuals diagnosed with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [20]. This double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, conducted by Karim et al. [28], involved 92 male participants aged between 58 and 73 years with chronic heart failure, spanning a 12-week supplementation period. Initially, no significant variation in HGS was detected between control and treatment groups. However, post-supplementation results revealed a statistically significant difference in mean HGS values, with the placebo group averaging 22.09 ± 2.18 kg/f, contrasted with the probiotic group at 25.78 ± 3.56 kg/f. Considering an alpha error of 5%, a beta error of 20%, and an additional inflation of 20% to accommodate potential attrition, the total sample size calculation a required sample of 28 participants. The analytic cohort consisted of 30 participants, thus exceeding the calculated requirement and ensuring adequate statistical power to detect the anticipated effect size under the assumptions of the original model.

However, we acknowledge that effective statistical power for exploratory subgroup analyses is inherently limited, and these analyses should therefore be interpreted as hypothesis-generating.

2.5. Characteristics of Participants

Sociodemographic data—including age, smoking status, pre-existing comorbidities, and medication use—were gathered through patient interviews via a nutritional history form or directly from medical records at the study’s commencement. Outcomes were evaluated at two time points: T0 (baseline), at discharge following an average hospital stay of three days, and T1 (after a 90-day supplementation period).

2.5.1. Handgrip Strength

Handgrip strength was assessed using a hydraulic hand dynamometer (Saehan SH5001®, Saehan Corporation, Changwon-si, Republic of Korea). To minimize inter-rater variability, all assessments were conducted by a single trained examiner using a new factory-calibrated device. Standardized posture, verbal instructions, and familiarization procedures were provided to ensure maximal voluntary effort across trials.

During the assessment, participants were seated with hips and knees flexed at 90°, arms positioned close to the trunk, and elbows also flexed at 90°. The forearms were held in a neutral position (midway between pronation and supination) with wrists extended between 0° and 30°, allowing for ulnar deviation ranging from 0° to 15° [29]. HGS was measured in both the dominant and non-dominant hands, with three trials per hand. Dominance was self-reported.

Each measurement consisted of a maximum continuous contraction lasting three seconds, followed by a one-minute rest between trials. The highest value from the three attempts was utilized for subsequent analysis. HGS was interpreted as a continuous variable expressed in kilograms of force (kg/f). Additional analyses referenced cutoff points from Cruz-Jentoft et al. [30] (<27 kg/f for men and <16 kg/f for women) and Delinocente et al. [31] (<32 kg/f for men and <21 kg/f for women) to classify low HGS. The distinction between dominant and non-dominant HGS was maintained in accordance with normative reference standards and to allow analysis of potential lateralized sensitivity to change.

2.5.2. Anthropometric Measurements

Secondary outcomes involved anthropometric indicators reflective of muscle mass, specifically the appendicular skeletal mass index (ASMI) as defined by Lee et al. [32]; arm muscle circumference (AMC), measured using the approach outlined by Frisancho [33] which combines triceps skinfold (TSF) [34] and arm circumference (AC) [35]; calf circumference (CC), measured exclusively in older adults and adapted for excess weight as per Gonzalez et al. [36]; and adductor pollicis muscle thickness (APMT), following the methodology described by Lameu et al. [37], with measurements taken on both hands and averaged across three readings.

Additional anthropometric data collected included body mass index (BMI) with relevant cutoff points for both adults [38] and older adults [39] as well as waist circumference (WC) in accordance with World Health Organization guidelines [39]. All anthropometric measurements were performed by trained researchers adhering to standardized protocols [40], aimed at minimizing inter-rater variability.

Body weight was measured using a portable scale (Marte Científica LS200P®, Santa Rita do Sapucaí, MG, Brazil) with a capacity of 200 kg and a precision of 50 g. Height was measured using a stadiometer with a capacity of 2.00 m and a precision of 1.0 mm (Avanutri®, Três Rios, RJ, Brazil). Circumferences were measured using a non-elastic, inextensible anthropometric measuring tape with a capacity of 2.00 m (Sanny®, São Bernardo do Campo, SP, Brazil). Skinfold thicknesses were measured using a scientific skinfold caliper with a sensitivity of 0.1 mm (Cescorf®, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil).

2.5.3. Highly Sensitive C-Reactive Protein (CRP)

Highly sensitive CRP levels were quantified using the immunonephelometry method facilitated by an automated system (Dade Behring Marburg GmbH, Deerfield, IL, USA) in conjunction with specific reagents. The analytical sensitivity of this assay was established at 0.175 mg/L.

2.5.4. Dietary Intake

Dietary intake was evaluated through 24-h dietary recalls (R24h), conducted at two distinct time points. Each time point included one recall, supplemented by an additional recall during the data collection week, which covered both a weekday and a weekend day. Food intake was quantified in kilocalories for total energy and in grams for macronutrients, including carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and fiber, using specialized nutritional software. In instances where certain food items were not available in the software, we developed preparation technical sheets informed by the Brazilian Food Composition Table and the serving table from the Food Guide for the Brazilian Population, complemented by data from food labels [41,42]. Following the documentation of food consumption, we performed a data consistency analysis to identify outliers in daily intake (less than 500 kcal or exceeding 4000 kcal). This procedure aimed to correct typographical errors as well as instances of under-reporting or over-reporting. Finally, we adjusted caloric intake data using the residual method, a technique articulated by Willett, Howe, and Kushi [43], allowing for more refined nutrient estimates in relation to total energy intake.

2.5.5. Physical Activity

Physical activity levels were indirectly assessed using the long version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), which has been both translated and validated for the Brazilian context [44]. Data interpretation adhered to the classification framework established by Pitanga et al. [45], categorizing participants as either insufficiently active (sedentary or minimally active) or active (active or very active).

2.5.6. Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF)

LVEF was assessed by trained physicians using imaging modalities, primarily transthoracic echocardiography. This approach facilitated the evaluation of the systolic function of both left and right ventricles as well as diastolic function. Based on LVEF measurements, patients were categorized into three groups: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) for LVEF ≥ 50%; heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) for LVEF < 40%; and an intermediate category for those with LVEF between 40% and 49% [46].

2.5.7. Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Gastrointestinal symptoms were assessed utilizing the Gastrointestinal Symptoms Rating Scale (GSRS), which has been translated and validated for the Brazilian population [47]. Moreover, stool classification was performed according to the Bristol Stool Scale [48], categorizing stools into seven distinct types based on consistency and morphology.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA® version 19.5 for Windows®. Continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation for normally distributed data, or median and interquartile range for non-normally distributed data. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and homogeneity of variances using Levene’s test. Comparisons between groups (control and intervention) for continuous variables utilized Student’s t-test for parametric data and the Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric data. Categorical variables were analyzed for associations using the Chi-Square Test or Fisher’s exact test when expected cell frequencies were <5 in more than 20% of cells.

To evaluate the treatment effect adjusted for baseline HGS, an ANCOVA model of the form m3~group + m1 was fitted. A continuous interaction term (group × M1) was added to examine whether the treatment effect varied as a function of baseline strength. Regression coefficients (β), 95% confidence intervals, and p-values were reported. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

All analyses were performed according to a per-protocol approach given the explanatory nature of the trial and the relevance of complete follow-up measurements for the primary outcome.

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment and Baseline Characteristics

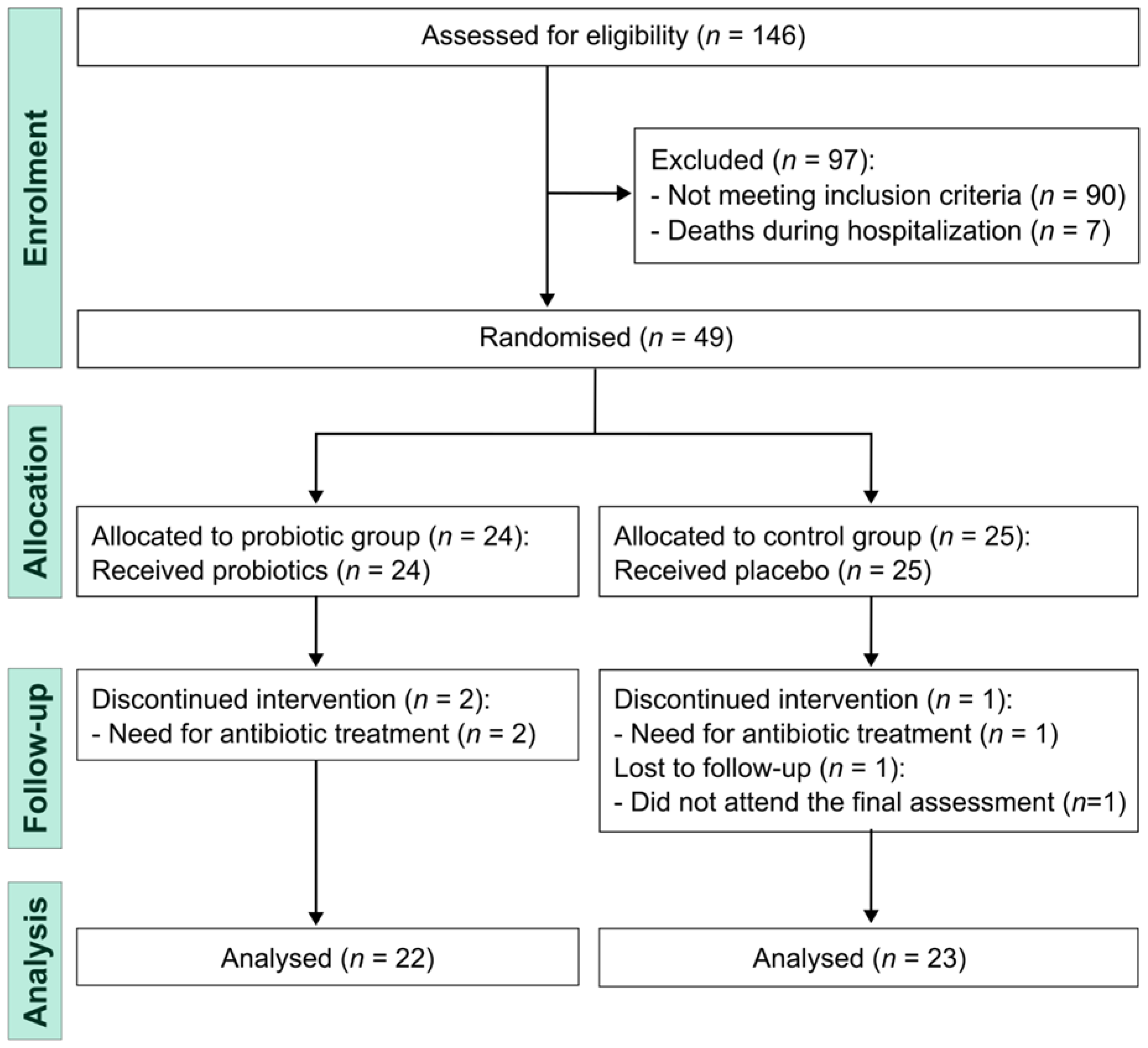

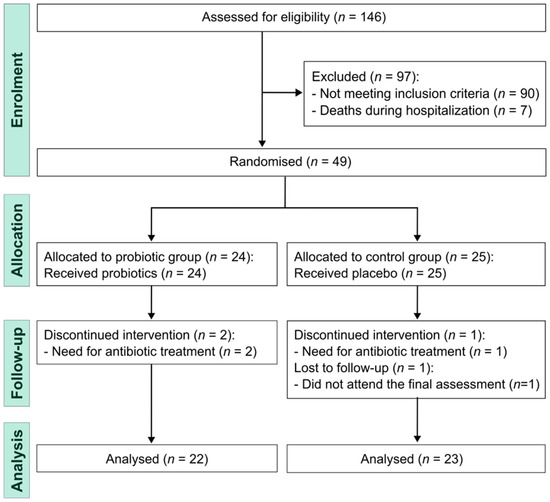

All individuals scheduled for coronary artery bypass grafting surgery were assessed for eligibility between November 2021 and March 2023. Of the 146 screened patients, 97 did not progress to randomization due to postoperative clinical instability, initiation of antibiotic therapy, postoperative complications, early discharge before eligibility confirmation, or unwillingness to participate. Randomization was performed only after clinical stabilization and verification of eligibility criteria. The final analytic sample consisted of 45 participants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of study participants, revealing comparable demographic, lifestyle, and clinical profiles between the PRO and PLA groups at study onset. The majority of participants were male (73.3%), with a mean age of 60.0 years (±8.4 years). The age distribution showcased a range from 40 to 79 years; however, only three individuals were over 70 years (two in the PLA group and one in the PRO group), and five participants were aged 40 to 49 years (three in placebo and two in probiotic). Most participants (82.2%) fell within the 50 to 69-year age bracket, indicating a more concentrated enrollment within this demographic. A notable proportion (66.7%) were current smokers. All participants were on antihypertensives, anticoagulants, and statins; those with type 2 diabetes mellitus were treated with metformin. Additionally, one participant utilized NPH insulin, while another was prescribed benzodiazepines. Crucially, there was no history of prior cardiovascular events among participants. The median left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) values were significantly different between groups: 47% (range: 41–65%) for the PRO group and 64% (range: 50–65%) for the PLA group. Importantly, all participants maintained LVEF values above 40%.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants (n = 45).

3.2. Dietary Intake and Physical Activity Level Estimation

Table 2 presents data regarding dietary intake and estimated energy expenditure associated with physical activities, both pre- and post-supplementation. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences between the groups. It is noteworthy that all participants maintained energy intakes within the range of 800 to 2300 kcal/day.

Table 2.

Dietary intake and physical activity level of participants (n = 45).

3.3. Anthropometric Measurements

Table 3 presents the anthropometric data collected pre- and post-supplementation. Analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the groups. Following supplementation, the median LVEF recorded was 62% (interquartile range 53–65%) in the PLA group and 54.5% (46–64%) in the PRO group, with a Mann–Whitney U test indicating no significant difference (p = 0.11). Additionally, median C-reactive protein (CRP) levels post-supplementation were 1.4 mg/L (1.0–4.8) in the PLA group compared to 3.3 mg/L (1.5–5.5) in the PRO group, also with no significant difference observed (Mann–Whitney test, p = 0.28).

Table 3.

Anthropometric indicators of participants (n = 45).

3.4. Muscle Strength

In the analysis of the overall sample, probiotic supplementation did not yield a statistically significant impact on HGS, as presented in Table 4. A further dichotomous analysis was performed, specifically targeting baseline HGS adequacy in men aged 50 and older, based on the classifications defined by Cruz-Jentoft [30] and Delinocente [31]. This aspect is particularly pertinent considering that the latest systematic review indicated a substantial effect of probiotics on muscle strength within this demographic, as detailed in Table 5 [20]. It is important to note that these analyses were not part of the original protocol and are therefore classified as exploratory efforts aimed at validating the initial hypotheses.

Table 4.

Handgrip strength measurements of participants (n = 45).

Table 5.

Handgrip strength among men 50 years of age or older according to cut-off points proposed by Cruz-Jentoft et al. [30] and Delinocente et al. [31] (n = 30).

In the subgroup analysis, no significant differences were identified between the intervention and control groups pre- and post-supplementation for any of the measured variables. Concerning the assessed outcomes, while no significant differences emerged with the Cruz-Jentoft criteria, a notable distinction was observed between groups concerning low HGS (<27 kg/f) of the non-dominant hand, in accordance with Delinocente’s thresholds [31]. This analysis revealed a mean difference of 4.6 kg/f (p = 0.04), indicating a noteworthy effect of the intervention in this specific context.

In the baseline-adjusted continuous ANCOVA model among men 50 years of age or older, a significant baseline-by-treatment interaction was observed for the non-dominant hand (β = +0.33, 95%CI: +0.02 to +0.62, p = 0.038), indicating greater improvements in participants with lower baseline strength (Table 6). No significant interaction was found for the dominant hand (p = 0.150).

Table 6.

Continuous ANCOVA model for handgrip strength adjusted for baseline values (n = 30).

3.5. Adherence to Supplementation and Adverse Effects

The PRO group had an average adherence rate of 99.1 ± 1.6%, whereas the PLA group had a rate of 98.5 ± 2.6%. Statistical analysis revealed no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.97, Mann–Whitney test). Furthermore, all participants reported no adverse effects associated with supplementation, and none experienced two or more consecutive days without taking their assigned supplements.

4. Discussion

Our analysis demonstrated that 90 days of supplementation with Lacticaseibacillus paracasei CCT 7861, Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus CCT 7863, Lacticaseibacillus acidophilus CCT 7947, and Bifidobacterium lactis CCT 7858 (4 × 109 CFU/day) did not improve muscle strength in the overall sample of post-AMI patients undergoing coronary revascularization. To our knowledge, no previous clinical trials have assessed the effects of multistrain probiotic supplementation in this population, limiting direct comparisons.

Evidence from a systematic review by Prokopidis et al. [20] suggests that the effects of probiotics on muscle strength may be more pronounced in middle-aged and older individuals, particularly with interventions ≥ 12 weeks of duration, although effects on lean mass remain inconsistent. This pattern suggests that age and intervention duration may influence the responsiveness to probiotics. In our study, the cohort presented a mean age above 50 years and was characterized by a post-surgical inflammatory state, which may have attenuated potential functional improvements at the whole-sample level. Given these considerations and the emerging literature on the microbiota–muscle–inflammation axis, we explored a post hoc subgroup comprising men ≥ 50 years with low baseline HGS, adopting the cutoff proposed by Delinocente [31] based on a Brazilian normative cohort, in line with recommendations from Cruz-Jentoft et al. [30] for region-specific thresholds.

Within this subgroup, an improvement in the non-dominant HGS was identified after supplementation. This finding should be interpreted cautiously due to the small number of participants and the exploratory post hoc nature of the analysis, which increases the likelihood of a type I error. As such, these results are hypothesis-generating and require replication in adequately powered trials. The selective improvement in the non-dominant limb may reflect lower baseline values and, therefore, greater responsiveness to physiological modulation, whereas the dominant hand (being used more frequently in daily tasks) may require a larger stimulus to elicit measurable changes. In line with this, the continuous ANCOVA model showed that the treatment effect was dependent on baseline strength, with greater gains observed among participants with lower initial handgrip values. This suggests that probiotic supplementation may preferentially benefit individuals with reduced muscle function.

The magnitude of change in HGS also warrants further contextualization. Minimal clinically important differences for HGS are not definitively established, but a recent systematic review suggests that changes of approximately 5.0 to 6.5 kg/f may be meaningful [49], whereas analyses of minimal detectable change indicate thresholds of approximately 2.9–3.2 kg [50]. Within this framework, the mean difference of 4.6 kg observed in our subgroup lies within a range considered potentially relevant, although the exploratory nature of this finding precludes definitive interpretation.

Sex-specific factors may also be relevant. Our sample consisted predominantly of men, and HGS trajectories differ markedly between sexes across aging, with distinct patterns of age-associated decline and associations with outcomes such as disability, hospitalization, and mortality [51,52]. Differences in inflammatory response and recovery following AMI and revascularization may further contribute to variability in functional outcomes, reinforcing that our findings may not extrapolate directly to women, younger individuals, or patients treated conservatively without revascularization.

With respect to inflammation, CRP concentrations declined in both groups over 90 days, with no between-group differences. This pattern likely reflects postoperative recovery and the natural resolution of inflammation following revascularization rather than a specific effect of probiotic supplementation. Few studies have examined probiotic supplementation in patients after AMI; however, a randomized trial involving 44 participants undergoing percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty reported reductions in CRP in the PRO group [53]. Although probiotics have been proposed to influence muscle through reductions in pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6) and stimulation of anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10 [54], as well as via effects on mitochondrial metabolism, SCFA production, and protein synthesis, our study was not designed to evaluate these mechanisms. Moreover, the absence of microbiota composition or functional analyses limits mechanistic inference. Therefore, our results do not support conclusions regarding anti-inflammatory efficacy in this context.

Despite the absence of between-group differences in muscle mass, low HGS has been associated with adverse outcomes including disability, hospitalization, falls, and premature mortality, and may be improved through integrated strategies combining resistance exercise, protein intake, microbiota modulation, and nutritional support [53]. Such approaches may be particularly relevant in older or overweight individuals, who were prevalent in our cohort.

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the sample size calculation was based on a single randomized trial, which introduces uncertainty regarding the estimated effect size. Although the final analytic sample (n = 30) exceeded the calculated requirement (n = 28) and ensured adequate power to detect the hypothesized effect, the relatively small number of participants increases the risk of type II error for smaller effects and does not allow for adequately powered subgroup analyses. For this reason, subgroup findings should be considered exploratory and interpreted with caution. Second, although a large proportion of screened patients did not progress to randomization, these exclusions occurred prior to allocation and reflect the clinical context of acute myocardial infarction and postoperative revascularization, in which mortality, clinical instability, postoperative complications and antibiotic therapy are frequent. As such, these exclusions affect external rather than internal validity, and do not compromise the integrity of the randomized comparison. Third, the assessment of dietary intake and physical activity relied on self-reported instruments (24-h dietary recalls and IPAQ), which are subject to recall and reporting bias and may not fully capture habitual behaviors. However, standardized procedures, consistency checks for under- and over-reporting, and energy adjustment by the residual method were employed to minimize misclassification. Fourth, although anthropometric measurements were collected by trained personnel using standardized procedures, inter- and intra-observer variability cannot be fully excluded. Despite that, the methodology adopted for anthropometric standardization is supported by validated techniques and was referenced accordingly. Fifth, we did not assess gut microbiota composition, which limits mechanistic interpretation of the effects and does not allow for clarification of potential pathways linking probiotic supplementation to muscle function in the post-AMI context. Sixth, the exclusion of individuals with atypical diets, probiotic/prebiotic/synbiotic supplement use, or recent antibiotic exposure improved internal validity by reducing microbiota-related confounding but may limit external validity to populations with more diverse dietary patterns or environmental exposures. Seventh, although the theoretical age eligibility criterion was broad, the enrolled sample was clinically typical for post-revascularization patients, mitigating concerns regarding age-related heterogeneity. Finally, post-surgical recovery trajectories may have influenced behavioral factors such as diet and activity, which could not be objectively monitored throughout the intervention.

Despite these limitations, the study has several strengths. Its randomized, placebo-controlled, triple-blind design minimizes bias and enhances causal inference. Adherence to supplementation exceeded 98% in both groups and no issues related to storage stability were reported. Loss to follow-up was minimal and balanced, reducing the risk of differential attrition. The eligibility criteria restricted exposure to confounding environmental factors known to influence microbiota composition, improving internal validity [22,27,55,56]. To our knowledge, this is the first trial to evaluate multistrain probiotic supplementation in post-AMI patients undergoing revascularization, a clinically relevant yet understudied population. Together, these characteristics support the robustness of the null findings in the overall cohort and provide a rigorous starting point for future trials targeting functional or mechanistic outcomes.

In conclusion: probiotic supplementation did not improve muscle strength in the overall cohort. An exploratory improvement in non-dominant HGS was observed in men ≥50 years with low baseline strength, which warrants confirmation in larger and adequately powered studies before clinical relevance can be inferred.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nutraceuticals6010012/s1.

Author Contributions

I.M.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. E.G.S., L.Q.T.C. and M.A.C.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing—original draft. R.L.G., A.K.F.d.S. and E.B.S.d.M.T.: Methodology, Writing—original draft. R.F.: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, and Supervision of project. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no funding from public or private entities or agencies for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Federal University of Grande Dourados, Brazil (protocol code 16691419.7.0000.5160 and date of approval 3 April 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

To the Postgraduate Program in Food, Nutrition, and Health of the Federal University of Grande Dourados (PPGANS-UFGD) for the technical and pedagogical support; to the CAPES, Brazil for the scholarship granted to the first three authors; to the team of and Goldsby King Evangelical Hospital for the location granted to conduct the study; and to the company Gabbia® (Barra Velha, SC, Brazil) for donating the supplements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The supplements were provided by Gabbia® (Barra Velha, SC, Brazil), which had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V.; Murray, C.J.; Roth, G.A.; Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks Collaborators. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risks, 1990–2022. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 2350–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 DALYs and Death Collaborators HALE. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1859–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.M.M.D.; Brant, L.C.C.; Polanczyk, C.A.; Malta, D.C.; Biolo, A.; Nascimento, B.R.; de Souza, M.d.F.M.; De Lorenzo, A.R.; de Paiva Fagundes, A.A., Jr.; Schaan, B.D.; et al. Cardiovascular Statistics—Brazil 2023 (English Title). ABC Cardiol. 2024, 121, e20240079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarović, Z.; Makarović, S.; Bilić-Ćurčić, I.; Mihaljević, I.; Mlinarević, D. Nonobstructive coronary artery disease–Clinical relevance, diagnosis, management and proposal of new pathophysiological classification. Acta Clin. Croat. 2018, 57, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, A.K.; Choudhury, D.; Halder, B.; Paul, P.; Uddin, A.; Chakraborty, S. A review on coronary artery disease, its risk factors, and therapeutics. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 16812–16823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, B.R.; Brant, L.C.C.; Naback, A.D.N.; Veloso, G.A.; Polanczyk, C.A.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Malta, D.C.; Ferreira, A.V.L.; de Oliveira, G.M.M. Burden of cardiovascular disease attributable to risk factors in Portuguese-speaking countries: Data from the Global Burden of Disease 2019. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2022, 118, 1028–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trøseid, M.; Andersen, G.Ø.; Broch, K.; Hov, J.R. The gut microbiome in coronary artery disease and heart failure: Current knowledge and future directions. EBioMedicine 2020, 52, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahed, S.Z.; Barzegari, A.; Zuluaga, M.; Letourneur, D.; Pavon-Djavid, G. Myocardial infarction and gut microbiota: An incidental connection. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 129, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, D.C.; Rocha, I.M.G.; Waitzberg, D.L. Disbiose. In Gastrointestinal Microbiota: From Dysbiosis to Treatment (English Title); Waitzberg, D.L., Rocha, R.M., Almeida, A.H., Eds.; Atheneu: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2021; pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Yuan, X. Gut microbiota on cardiovascular diseases-a mini review on current evidence. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1690411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Lyu, J.; Zhao, R.; Liu, G.; Wang, S. Gut macrobiotic and its metabolic pathways modulate cardiovascular disease. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1272479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosicki, G.J.; Fielding, R.A.; Lustgarten, M.S. Gut microbiota contribute to age-related changes in skeletal muscle size, composition, and function: Biological basis for a gut-muscle axis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2018, 102, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prokopidis, K.; Chambers, E.S.; Ni Lochlainn, M.; Witard, O.C. Mechanisms linking the gut-muscle axis with muscle protein metabolism and anabolic resistance: Implications for older adults at risk of sarcopenia. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 770455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Cortés, R.; del Pozo Cruz, B.; Gallardo-Gómez, D.; Calatayud, J.; Cruz-Montecinos, C.; López-Gil, J.F.; López-Bueno, R. Handgrip strength measurement protocols for all-cause and cause-specific mortality outcomes in more than 3 million participants: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 2473–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; He, B. The gut-muscle axis: A comprehensive review of the interplay between physical activity and gut microbiota in the prevention and treatment of muscle wasting disorders. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1695448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksova, A.; Fluca, A.L.; Beltrami, A.P.; Dozio, E.; Sinagra, G.; Marketou, M.; Janjusevic, M. Part 1-Cardiac Rehabilitation After an Acute Myocardial Infarction: Four Phases of the Programme-Where Do We Stand? J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmor-Barkan, Y.; Kornowski, R. The gut microbiome and cardiovascular risk: Current perspective and gaps of knowledge. Future Cardiol. 2017, 13, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosh, L.; Ghazi, M.; Haddad, K.; El Masri, J.; Hawi, J.; Leone, A.; Basset, C.; Geagea, A.G.; Jurjus, R.; Jurjus, A. Probiotics, gut microbiome, and cardiovascular diseases: An update. Transpl. Immunol. 2024, 76, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prokopidis, K.; Giannos, P.; Kirwan, R.; Ispoglou, T.; Galli, F.; Witard, O.C. Impact of probiotics on muscle mass, muscle strength and lean mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Jin, B.; Fan, Z. Mechanisms Involved in Gut Microbiota Regulation of Skeletal Muscle. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 2151191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besora-Moreno, M.; Llauradó, E.; Valls, R.M.; Pedret, A.; Solà, R. Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on sarcopenia parameters in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Ver. 2024, 83, e1693–e1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.Y.; Jung, E.J.; Lee, J.G.; Han, B.G.; Hong, J.Y.; Kim, Y.J. Effect of Lactobacillus spp. supplementation for improving muscle health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Food 2025, 28, 842–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Peng, F.; Yang, H.; Luo, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Liao, H.; Lei, H.; Liu, S.; Yang, T.; et al. Probiotics and muscle health: The impact of Lactobacillus on sarcopenia through the gut–muscle axis. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1559119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ny, Y.; Yang, X.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Z.; Wu, L.; Jiang, J.; Yang, T.; Ma, L.; Fu, Z. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium Improves Physiological Function and Cognitive Ability in Aged Mice by the Regulation of Gut Microbiota. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1900603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.-W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. CONSORT 2025 statement: Updated guideline for reporting randomized trials. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1776–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campaniello, D.; Bevilacqua, A.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R. A narrative review on the use of probiotics in several diseases. Evidence and perspectives. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1209238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.; Muhammad, T.; Shah, I.; Khan, J.; Qaisar, R. A multistrain probiotic reduces sarcopenia by modulating Wnt signaling biomarkers in patients with chronic heart failure. J. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüssel, M.M.; dos Anjos, L.A.; de Vasconcellos, M.T.L.; Kac, G. Reference values of handgrip dynamometry of healthy adults: A population-based study. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delinocente, M.L.B.; de Carvalho, D.H.T.; de Oliveira Máximo, R.; Chagas, M.H.N.; Santos, J.L.F.; de Oliveira Duarte, Y.A.; Steptoe, A.; de Oliveira, C.; da Silva Alexandre, T. Accuracy of different handgrip values to identify mobility limitation in older adults. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021, 94, 104347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Wang, Z.; Heo, M.; Ross, R.; Janssen, I.; Heymsfield, S.B. Total-body skeletal muscle mass: Development and cross-validation of anthropometric prediction models. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisancho, A.R. New norms of upper limb fat and muscle areas for assessment of nutritional status. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1981, 34, 2540–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohman, T.G. Assessing fat distribution. In Advances in Body Composition Assessment: Current Issues in Exercise Science; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1992; Volume 3, pp. 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Frisancho, A.R. Triceps skin fold and upper arm muscle size norms for assessment of nutritional status. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1974, 27, 1052–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.C.; Mehrnezhad, A.; Razaviarab, N.; Barbosa-Silva, T.G.; Heymsfield, S.B. Calf circumference: Cutoff values from the NHANES 1999–2006. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameu, E.B.; Gerude, M.F.; Corrêa, R.C.; Lima, K.A. Adductor pollicis muscle: A new anthropometric parameter. Rev. Hosp. Clin. 2004, 59, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. BMI Classification; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Lipschitz, D.A. Screening for nutritional status in the elderly. Prim. Care 1994, 21, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perini, T.A.; Oliveira, G.L.; Ornellas, J.S.; Oliveira, F.P. Technical error of measurement in anthropometry. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2005, 11, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Sao Paulo (USP): Food Research Center (FoRC). Brazilian Food Composition Table. Versão 7.2. São Paulo. 2023. Available online: http://www.tbca.net.br/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Brazil, Ministry of Health, Secretariat of Primary Health Care, Department of Health Promotion. Food Guide for the Brazilian Population (English Title), 2nd ed.; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.C.; Howe, G.R.; Kushi, L.H. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 65, 1220S–1228S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsudo, S.; Araújo, T.; Matsudo, V.; Andrade, D.; Andrade, E.; Braggion, G. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): Validity and reproducibility study in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Ativ. Fís. Saúde 2001, 6, 5–18. Available online: https://rbafs.org.br/RBAFS/article/view/931 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Pitanga, F.J.G.; Matos, S.M.A.; Almeida, M.D.C.; Barreto, S.M.; Aquino, E.M.L. Leisure-time physical activity, but not commuting physical activity, is associated with cardiovascular risk among ELSA-Brasil participants. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2018, 110, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, L.E.P.; Montera, M.W.; Bocchi, E.A.; Clausell, N.O.; Albuquerque, D.C.; Rassi, S.; Colafranceschi, A.S.; de Freitas, A.F., Jr.; Ferraz, A.S.; Biolo, A. Diretriz Brasileira de Insuficiência Cardíaca Crônica e Aguda. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2018, 111, 436–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.S.; Sardá, F.A.H.; Giuntini, E.B.; Gumbrevicius, I.; Morais, M.B.D.; Menezes, E.W.D. Translation and validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) questionnaire. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2016, 53, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.J.; Heaton, K.W. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 32, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W. Minimal clinically important difference for grip strength: A systematic review. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2019, 31, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawaya, Y.; Ishizaka, M.; Hirose, T.; Shiba, T.; Onoda, K.; Kubo, A.; Maruyama, H.; Urano, T. Minimal detectable change in handgrip strength and usual and maximum gait speed scores in community-dwelling Japanese older adults requiring long-term care/support. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, B.S.; de Souza Andrade, A.C.; Torres, J.L.; de Souza Braga, L.; de Carvalho Bastone, A.; de Melo Mambrini, J.V.; Lima-Costa, M.F. Nationwide handgrip strength values and factors associated with muscle weakness in older adults: Findings from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSI-Brazil). BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvandi, M.; Strasser, B.; Meisinger, C.; Volaklis, K.; Gothe, R.M.; Siebert, U.; Ladwig, K.-H.; Grill, E.; Horsch, A.; Laxy, M.; et al. Gender differences in the association between grip strength and mortality in older adults: Results from the KORA-age study. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moludi, J.; Saiedi, S.; Ebrahimi, B.; Alizadeh, M.; Khajebishak, Y.; Ghadimi, S.S. Probiotics supplementation on cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction: A single-center double-blind clinical study. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2021, 14, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giron, M.; Thomas, M.; Dardevet, D.; Chassard, C.; Savary-Auzeloux, I. Gut microbes and muscle function: Can probiotics make our muscles stronger? J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 1460–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagnant, H.S.; Isidean, S.D.; Wilson, L.; Bukhari, A.S.; Allen, J.T.; Agans, R.T.; Lee, D.M.; Hatch-McChesney, A.; Whitney, C.C.; Sullo, E.; et al. Orally Ingested Probiotic, Prebiotic, and Synbiotic Interventions as Countermeasures for Gastrointestinal Tract Infections in Nonelderly Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolinska, S.; Popescu, F.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M. A Review of the Influence of Prebiotics, Probiotics, Synbiotics, and Postbiotics on the Human Gut Microbiome and Intestinal Integrity. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.