Scoping Review of the Environmental and Human Health Effects of Rural Alaska Landfills

Highlights

- This work reviews articles related to landfills in rural Alaska communities and may guide future research related to gaps identified in this review.

- Unlined landfills lacking leachate collection systems may impact public health.

- This work identifies several potential disease transmission and chemical exposure pathways associated with such landfills, which are primarily found in rural and tribal communities already facing significant health disparities.

- If harvested, birds, fish, other animals and plants living, growing, or feeding by open surface area landfills could present public health implications for Indigenous and other hunting populations via ingestion or contact with waste pathogens or chemicals.

- This review paper elucidates the need to continue to assess landfill contaminant transport, exposure pathways and risks and the unique challenges of solid waste management in rural Alaska and other Arctic environments.

- Future research directions regarding the risk to subsistence resources and the associated health implications for Alaska Native and other Arctic subsistence-based cultures should prioritize community-based, co-produced research that integrates Indigenous Knowledge with Western science. This approach is crucial for addressing the existing health disparities and unique environmental exposures faced by these communities.

Abstract

1. Introduction

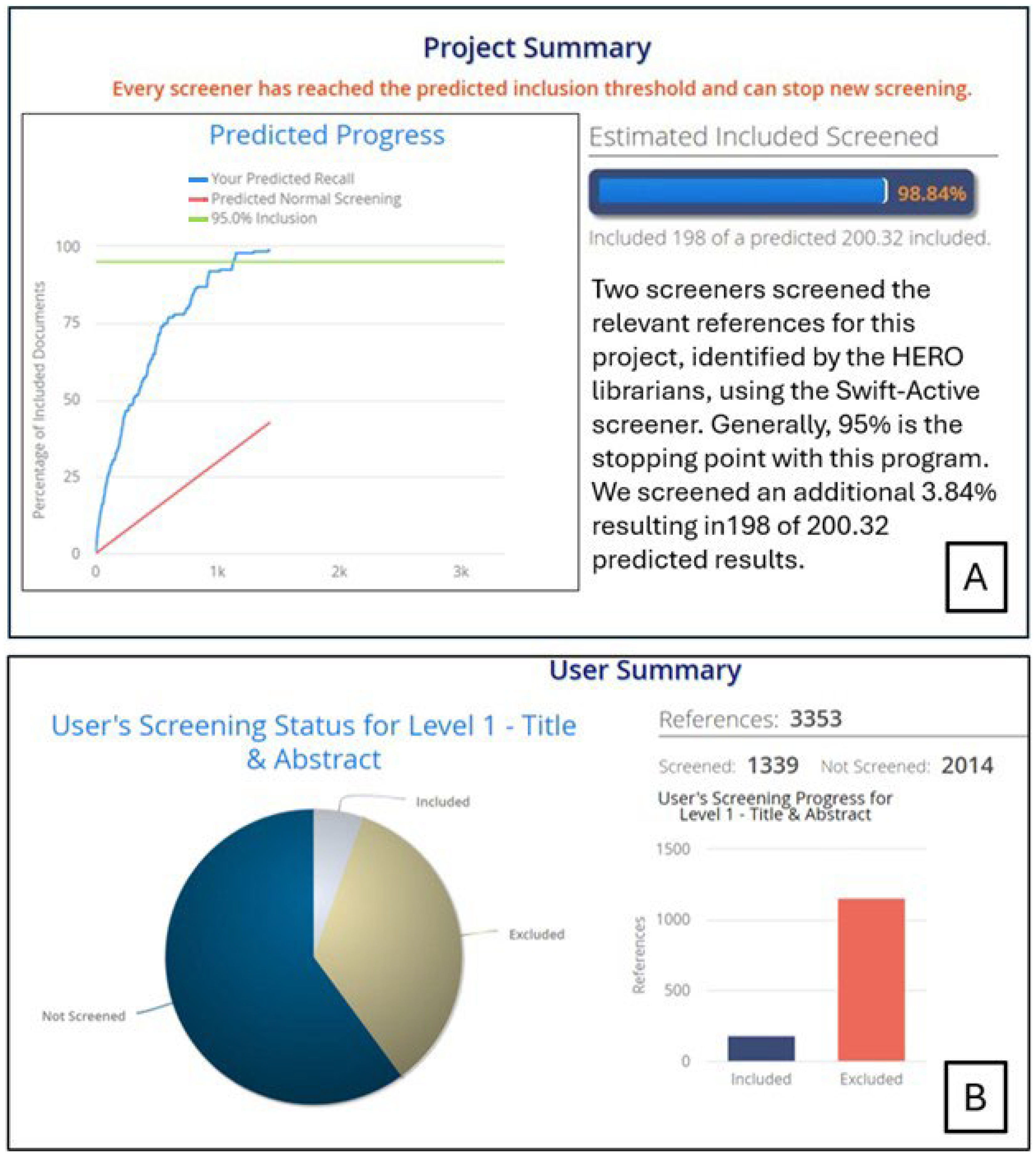

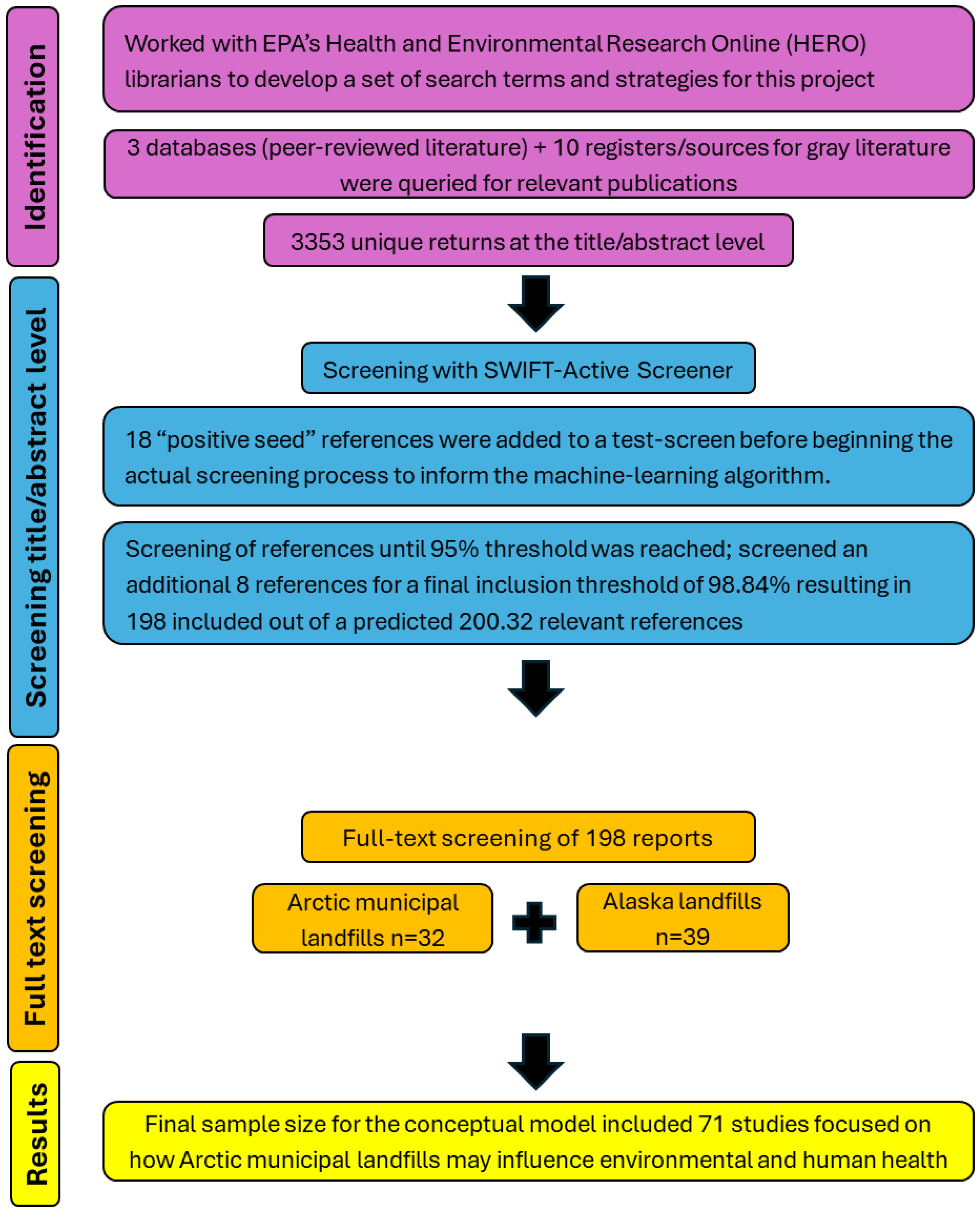

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

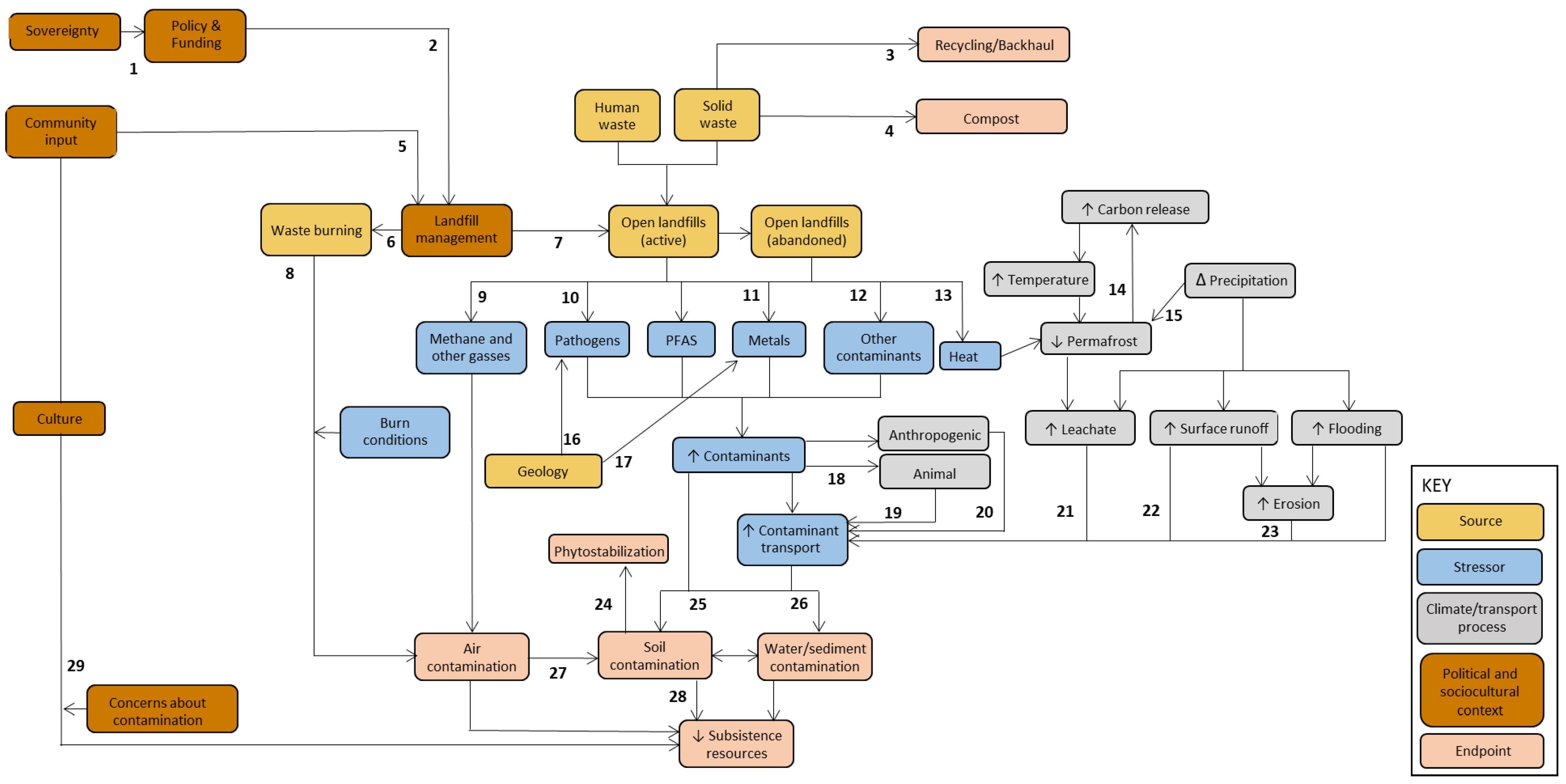

3.1. Conceptual Model

3.2. Environmental Results

| Author (Year) | Environmental Impact | Source Type | Main Outcome | Location | Sample Size | Main Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahlstrom et al. (2018) [73] | Microbes | Scientific Article | E. coli | Soldotna landfill in southcentral Alaska | 27 E. coli isolates (13 from 20 bald eagles, 14 from 56 gulls) | Some E. coli isolates had sequence types associated with human infections and contained clinically relevant resistance genes. Gulls and eagles demonstrated some genetically unrelated isolates with identical resistance profiles, while other isolates had identical core genomes and different resistance profiles. These results suggest bacterial strain sharing between species as well as horizontal gene transfer, with landfills serving as a source for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) acquisition or maintenance. |

| Ahlstrom et al. (2019) [74] | Microbes | Scientific Article | E. coli | Kenai Peninsula | 17 gulls, 139 Pacific salmon | AMR E. coli prevalence varied across time and space among gulls tracked longitudinally, although the landfill and the lower Kenai River had the highest prevalence. They found no evidence of E. coli in salmon from personal-use dipnet fisheries. These results suggest that gulls acquire AMR E. coli at anthropogenically disturbed sites and then transport it as they migrate. |

| ATSDR (2019) [91,96] | Water | Report | Heavy metals | Port Heiden, Alaska | Varied depending on part of study | Based on the physical and chemical hazards in Port Heiden, the authors found that people could be injured by surface debris. They also found that school drinking water met standards after treatment and called for greater information to assess residential wells, contamination from landfills/military, vapor intrusion, and contamination of subsistence foods. |

| ATSDR (2014) [94] | Soil | Report | PCBs | Port Heiden, Alaska | N/A | The low PCB levels detected in the relay station soil, roadway, and small animals were not expected to cause health effects. Crowberries had low but safe levels of PCBs; however, they recommended that crowberry consumption should be avoided. The area with foundation cover soils and Pad Grid 1—which is infrequently visited by residents—had high PCB levels. They could not assess risk from marine sources. |

| Barnes (2011) [62] | Water, microbes | Report | Environmental contaminants, E.coli, and Enterococci | Rural Alaska | 4 communities | E.coli and Enterococci were present in all waste-impacted surface and subsurface water samples. They also detected seven pharmaceutical compounds in the sewage lagoon and landfill-impacted water. |

| Brunett (1990) [79] | Water | Report | Physiochemical parameters, environmental contaminants | Merrill Field Landfill, Anchorage, Alaska | 444 measurement stations and 20 wells | Leachate from the closed Merrill Field landfill did not appear to be contaminating the creek that flows through the area. However, leachate was transported to the southern wetlands through groundwater. Contaminants reached wetlands as far as 2200 feet away based on aquifer and well sampling, although levels were below EPA drinking water standards. |

| Chambers (2005) [77] | Microbes | Thesis | E. coli, total coliform, Giardia lamblia, and Cryptosporidium parvum | Rural Alaska | Varied depending on part of study | Surface water flow transported bacteria to the community during spring thaw, but flow from the landfill did not contribute to contamination in town. Inside homes, fecal bacteria were found on water dippers, kitchen counters and floors, and in washbasin water. Giardia was found at the landfill. |

| Chambers et al. (2009) [78] | Microbes | Scientific Article | E. coli and total coliform | Rural Alaska | 19 boot samples, 12 road/off road sample pairs, 4 puddle samples, 45 ATV samples, 10 tarp samples | Shoes transported fecal contaminants inside homes. Fecal contamination was also observed in puddles on the roads and on ATV tires, which suggests vehicle use is one transport route for fecal contaminants. |

| Downey (1990) [82] | Water | Report | Physiochemical parameters, heavy metals | Fairbanks, AK | 22 wells, 2 rivers | Leachate was flowing to the Northwest of the Fairbanks-North Star Borough landfill. It remained near the water table. Chemical data showed elevated levels of several ions in the leachate plume, but they fell to background within a short distance from the landfill, suggesting water-supply wells would not be affected. |

| Flynn (1985) [83] | Water | Report | Physiochemical parameters, heavy metals | Fairbanks, AK | 22 wells, 2 rivers | Several wells in the Fairbanks Sanitary Landfill showed high concentrations of chloride, iron, and manganese compared to background levels. They also had relatively low pH and dissolved-oxygen concentrations. However, these constituents and properties fell to background levels in wells north and west of the landfill. |

| Gilbreath (2004) [97] | Air | Thesis | Adverse birth outcomes, self-report health symptoms | Rural Alaska | 1225 individuals (self-report), 10,073 individuals (birth outcomes), 10,360 individuals (congenital anomalies) | Self-reported health symptoms were associated with odor complaints, burning trash, number of visits to the landfill, subsistence practices, and residing within a 1/2 mile of a dumpsite. Women living in intermediate and high hazard dumpsite communities had lower birthweight, shorter gestation length, and greater congenital defects. |

| Glass (1986) [84] | Water | Report | Physiochemical parameters | Connors Bog Area, Anchorage, AK | 36 wells | Leachate was found beneath and near the abandoned landfill, and it contained elevated levels of dissolved solids, dissolved chloride, and total organics. The leachate was limited to < 500 feet from the landfill’s edge, and they found no evidence of leachate in the lake. |

| Hanson et al. (2008) [63] | Heat | Scientific Article | Temperature | Alaska, Michigan, British Columbia, New Mexico | 4 landfill sites with 700 sensors (measured weekly) | They measured landfill temperatures at different depths in four landfills. The warmest section was the central part of the middle third fraction. Higher areas were more similar to air temperature. The highest temperatures were observed in Michigan, followed by British Columbia, New Mexico, and Alaska. |

| Hanson et al. (2010) [98] | Heat | Scientific Article | Temperature | Alaska, Michigan, British Columbia, New Mexico | 4 landfill sites with 700 sensors (measured weekly) | They measured landfill temperatures at different depths in four landfills. The warmest part was the central part of the middle third fraction. Higher areas were more similar to air temperature. Temperatures were greatest in Michigan, then British Columbia, New Mexico, and Alaska. Anaerobic decomposition was associated with greater temperatures, temperature increases, and heat gain. Insulating materials applied over covers decreased temperature variation. |

| Liu (2007) [61] | Heat | Thesis | Temperature | Michigan, New Mexico, Alaska, and British Columbia | 4 landfill sites that included 609 temperature sensors (measured weekly) and 327 gas sensors (measured monthly) | Temperatures and methane at shallow depths or near landfill edges fluctuated seasonally. Both measures were stable in the middle and lower portions near the base. Their temperature and gas-release models accurately represented field conditions. |

| Mutter (2014) [18] | Water, microbes | Thesis | Environmental contaminants, E.coli, and Enterococci | Rural Alaska | 5 communities (5 dumps, 2 sewage systems) | E.coli and Enterococcus sp. were present in waste-impacted water and soil samples. They also observed heavy metal migration into nearby freshwater sources and found pharmaceuticals, phthalates, and benzotriazole in waste-impacted water samples. |

| Mutter et al. (2017) [86] | Microbes | Scientific Article | E.coli and Enterococci | Ekwok, White Mountain, Fort Yukon, Allakaket | 4 communities | Although all samples indicated high site-specific variability, both E. coli and Enterococcus sp. preferentially attached to and migrated with soil particles in surface waters. Additionally, both were transported off-site in snowmelt runoff. Enterococcus sp. had greater viability in cold conditions. |

| Naidu (2003) [89] | Soil | Scientific Article | Heavy metals | North Slope, Alaska | 2 sites | In the urban site, V increased each decade and Ba from 1986 to 1997. In both sites, levels of all metals were similar to unpolluted marine environments. Less than 1% of Hg was methylated, and percentages of elements bound in the non-lithogenous phase varied (50% Mn, 25–35% Co, 15–20% Zn, Cu, Ni, 10% V & Fe, and <3% of Cr). |

| Nelson (1984) [80] | Water | Conference Paper | Water Quality | Anchorage, Alaska | N/A | They calculated that incipient entry of pollutants into the aquifer would begin 80 years after leachate began migrating downward and would only reach “full strength” of breakthrough after 250 years. |

| Patterson et al. (2012) [85] | Water, microbes | Report | Physiochemical parameters, heavy metals, environmental contaminants, E. coli, and Enterococcus | Rural Alaska | 5 villages | They did not find evidence that landfill leachate was contaminating drinking water. However, they observed that microbial pathogens and aluminum levels were elevated in the leachate and should be monitored in treated drinking water and source waters. |

| Peirce & Van Daele (2006) [75] | Animal garbage consumption | Scientific Article | Behavioral observations | Dillingham, Alaska | 70 brown bears | Seventeen bears were predictable users of the Dillingham Landfill and had temporal patterns of use. Between four and 33 bears visited each night, with peak use occurring in July. Subadult activity peaked in June, male activity in June and August, and females with cubs in September. The most socially dominant bears fed the most from the landfill. |

| Solid Waste Program, Alaska DEC (2015) [87] | Soil | Report | Erosion risk | North & West AK coasts & ≤ 300 miles upriver, Aleutian Islands | 716 sites in 124 communities | Based on erosion risk and contaminant risk scores, they wrote Detailed Action Plans for the sites with the highest risk of eroding and distributing contaminants. |

| Weiser & Powell (2010) [76] | Animal garbage consumption | Scientific Article | Garbage in diet samples | Barrow, AK | Nonbreeding colony: 193 samples in 2007 and 248 2008. Breeding colony: 46 samples in 2007 and 403 in 2008. | Breeding adult gulls ate less garbage than nonbreeding gulls. Breeding gull samples showed no garbage change 2007–2008 while nonbreeding gulls consumed less garbage in 2008 than in 2007. Overall, garbage remained a large part of the diet in 2008. |

| Yesiller et al. (2005) [65] | Heat | Scientific Article | Temperature | Alaska, Michigan, British Columbia, New Mexico | 4 landfill sites with 355 temperature sensors (measured weekly) & 238 gas sensors (measured monthly) | Temperatures at shallow depths and near the edges of the landfills were similar to seasonal temperature variations. Deep and central locations had elevated temperatures compared to air and ground temperatures. Waste temperatures also decreased near the base. Peak Heat Content values were 12.5–47.8 °C/day. The highest values for temperatures, gradients, heat content, and heat generation were Michigan, followed by British Columbia, Alaska, and New Mexico. |

| Yesiller et al. (2008) [64] | Heat | Scientific Article | Temperature | Alaska, Michigan, British Columbia, New Mexico | 4 landfill sites | Landfill cover temperature varied seasonally with air temperature; it also demonstrated amplitude decrement and phase lag with depth. They found that warmer waste underneath landfill cover was associated with warmer cover and less frost penetration. Maximum and minimum temperature ranges were 18–30 °C and 13–21 °C. Average temperature was 13–18 °C at 1 m and 14–23 °C at 2-m depths. They found that frost depths were approximately 50% of those for soils at ambient conditions. Heat mainly flowed upward in the covers. Cover gradients varied between 18 & 14 °C/m. |

| Zenone (1975) [81] | Water | Scientific Article | Physiochemical parameters, heavy metals | Alaska, Michigan, British Columbia, New Mexico | 18 wells across 3 landfill sites | Leachate was detected in the ground water near two sites. At these sites, the water table was near land surface and waste was deposited at or below the water table. The leachate plume seemed to attenuate within the landfill or close by at the first site. They did not find leachate at a third site where waste disposal occurs above the water table. |

3.2.1. Water

3.2.2. Soil

3.2.3. Air

3.2.4. Heat

3.2.5. Microbes

3.2.6. Animal Garbage Consumption Patterns

3.3. Human Health Results

| Author | Study Focus: Adult or Child Health | Article Type | Main Outcome | Location | Sample Size | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Tribes & Zender Environmental (2003) [23] | Adult | Report | Self-report health symptoms | Rural Alaska | 101 Alaska Native communities and 1225 individuals | Most waste disposal sites in Alaska Native Villages were open dumps with little management. Due to limited solid waste management services, most residents dumped their own waste. Improper disposal of waste, such as unsorted burning and uncovered antifreeze, also contributed to the health risks. |

| Gilbreath (2004) [97] | Adult & Child | Thesis | Adverse birth outcomes, self-report health symptoms | Rural Alaska | 1225 individuals (self-report), 10,073 individuals (birth outcomes), 10,360 individuals (congenital anomalies) | Worse self-reported health symptoms were associated with residing within a 1/2 mile of a dumpsite, odor complaints, burning trash, number of visits to the landfill, and subsistence practices. Women living in intermediate and high hazard dumpsite communities had lower birthweight, shorter gestation length, and greater congenital defects. |

| Gilbreath & Kass (2006) [99] | Child | Scientific Article | Adverse birth outcomes | Rural Alaska | 10,073 individuals | Villages with intermediate and high hazard dumpsites had significantly greater percentage of infants with low birth weight and intrauterine growth retardation. Specifically, infants weighed 55.4 g and 36 g less when their mother was in the high exposure group compared to the low and intermediate exposure groups, and this effect was even larger when limited to Alaska Native mothers only. |

| Gilbreath & Kass (2006) [100] | Child | Scientific Article | Adverse birth outcomes | Rural Alaska | 10,360 individuals | Villages with intermediate and high hazard dumpsites did not have statistically significantly greater fetal and neonatal death or congenital anomalies. Mothers living in villages with high hazard dumpsites were four times more likely to have congenital anomalies classified as “other”. |

| McBeth (2010) [101] | Adult | Thesis | Respiratory infection deaths | Rural Alaska | 196 villages | High household size and low household income predicted greater pneumonia/influenza deaths in Alaska Native Villages. Tuberculosis deaths were associated with residence in certain areas and the type of heating fuel used in the home. Lastly, infectious disease deaths were positively associated with a high percentage of Alaska Natives in the population, large household, low percentage below poverty, and lack of healthcare within the village. |

| Zender et al. (2003) [24] | Adult | Report | Self-report health symptoms | Rural Alaska | 101 Alaska Native communities and 1225 individuals | Most waste disposal sites in Alaska Native Villages were open dumps with little management. Due to limited solid waste management services, most people dumped their own waste. Improper disposal of waste, such as unsorted burning and uncovered antifreeze, also contributed to the health risks. |

3.3.1. Infant Health

3.3.2. Population Health

4. Discussion

Unique Risks for Alaska Native Communities

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Search String | Date Run & Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (((“Open landfill”[tw] OR “Dump sites”[tw] OR “Dumpsites”[tw] OR “Open Dump”[tw] OR “Unlined landfill”[tw] OR “Class III landfill”[tw] OR “E-waste”[tw] OR “electronic waste”[tw] OR “Solid waste”[tw] OR “Solid waste disposal”[tw] OR “Household hazardous waste”[tw] OR “Hazardous waste”[tw] OR “Human waste”[tw] OR “Honeybucket”[tw] OR “Construction waste disposal”[tw] OR “demolition waste disposal”[tw] OR “Ash”[tw] OR “Mixed waste”[tw] OR “Leachate”[tw] OR “Lagoon”[tw] OR “holding pond”[tw]) AND (“Alaska”[tw] OR “Arctic”[tw] OR “Rural”[tw] OR “Indigenous”[tw] OR “Cold region”[tw] OR “Alaska Native Village”[tw] OR “Alaska Tribe *”[tw] OR “Alaska Tribal”[tw] OR “Indian land *”[tw])) AND 1980:3000 [dp]) | 10 December 2021 788 results HERO Import Batch ID: 45090 |

| Web of Science Core Collection | (((TS = “Open landfill” OR TS = “Dump sites” OR TS = “Dumpsites” OR TS = “Open Dump” OR TS = “Unlined landfill” OR TS = “Class III landfill” OR TS = “E-waste, electronic waste” OR TS = “Solid waste” OR TS = “Solid waste disposal” OR TS = “Household hazardous waste” OR TS = “Hazardous waste” OR TS = “Human waste” OR TS = “Honeybucket” OR TS = “Construction waste disposal” OR TS = “demolition waste disposal” OR TS = “Ash” OR TS = “Mixed waste” OR TS = “Leachate” OR TS = “Lagoon” OR TS = “holding pond”) AND (TS = “Alaska” OR TS = “Arctic” OR TS = “Rural” OR TS = “Indigenous” OR TS = “Cold region” OR TS = “Alaska Native Village” OR TS = “Alaska Tribe *” OR TS = “Alaska Tribal” OR TS = “Indian land *”)) AND (PY = 1980–2022)) | 10 December 2021 2888 results HERO Import Batch ID: 45091 |

Appendix B

- Make include/exclude decision.

- 2.

- For included papers, apply the following tags where relevant (individual tags and comment fields are indicated in bold).

- Abstract—comment: note if abstract is missing; if abstract is missing, assign tags below based on title, where possible

- LOCATION: geographic area addressed in paper

- ◦

- Alaska

- ◦

- Other arctic/subarctic regions

- ▪

- North America

- ▪

- Europe

- ▪

- Asia

- ▪

- Other

- ◦

- Non-arctic/subarctic regions

- ▪

- US

- ▪

- Non-US

- ▪

- Not specified

- ◦

- Indigenous land

- ◦

- Non-indigenous rural land

- ◦

- Not specified: location is not stated or clear based on title/abstract

- Landfill/waste disposal type—comment: note what type of landfill or waste disposal is addressed in the paper (e.g., lined or unlined, any waste burning, etc.), or if landfill or waste disposal type is not specified

- WASTE TYPE: types of waste addressed in paper

- ◦

- Not specified

- ◦

- Human waste: e.g., biosolids

- ◦

- Household waste: e.g., domestic wastes

- ◦

- Hazardous waste

- ◦

- Construction/demolition waste

- ◦

- Electronic waste

- Waste type—comment: note any information about specific types of waste addressed in paper, particularly if none of the above tags seem appropriate

- TOPICS: specific topic areas addressed in paper

- ◦

- Air quality

- ◦

- Water quality

- ◦

- Soil quality

- ◦

- Human health effects

- ◦

- Other environmental effects

- ◦

- Management/remediation

- Topics—comment: briefly note any information about topics of interest addressed in paper, particularly if none of the above tags seem appropriate

References

- Mohai, P.; Pellow, D.; Roberts, J.T. Environmental Justice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, P.; Postma, J.; ERRNIE Research Team. The TERRA Framework: Conceptualizing Rural Environmental Health Inequities Through an Environmental Justice Lens. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2009, 32, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keske, C.M.; Mills, M.; Godfrey, T.; Tanguay, L.; Dicker, J. Waste Management in Remote Rural Communities Across the Canadian North: Challenges and Opportunities. Detritus 2018, 2, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, T. Rural Intersections: Resource Marginalisation and the “Non-Indian Problem” in Highland Ecuador. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Federal Register. Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA); Office of the Federal Register: Washington, DC, USA, 1997.

- Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation. Purpose, Scope, and Applicability; Classes of MSWLF; Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation: Juneau, AK, USA, 1996.

- Mukherjee, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Hashim, M.A.; Gupta, B.S. Contemporary Environmental Issues of Landfill Leachate: Assessment and Remedies. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 472–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbay, G.; Jones, M.; Gadde, M.; Isah, S.; Attarwala, T. Design and Operation of Effective Landfills with Minimal Effects on the Environment and Human Health. J. Environ. Public Health 2021, 2021, 6921607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przydatek, G.; Kanownik, W. Impact of Small Municipal Solid Waste Landfill on Groundwater Quality. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqua, A.; Hahladakis, J.N.; Al-Attiya, W.A.K.A. An Overview of the Environmental Pollution and Health Effects Associated with Waste Landfilling and Open Dumping. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 58514–58536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, F.; Ncube, E.J.; Voyi, K. A Systematic Critical Review of Epidemiological Studies on Public Health Concerns of Municipal Solid Waste Handling. Perspect. Public Health 2017, 137, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, D.; Milani, S.; Lazzarino, A.I.; Perucci, C.A.; Forastiere, F. Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies on Health Effects Associated with Management of Solid Waste. Environ. Health 2009, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrijheid, M. Health Effects of Residence near Hazardous Waste Landfill Sites: A Review of Epidemiologic Literature. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000, 108, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. State Climate Summaries for the United States 2022: Alaska. NOAA Technical Report; NOAA NESDIS: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022.

- U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/AK/HEA775224 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Alaska Department of Transportation; Public Facilities. Department Fast Facts: Prepared for Legislative Session 2023; Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities: Juneau, AK, USA, 2023.

- United States Congress. Land Disposal Program Flexibility Act of 1996; United States Congress: Washington, DC, USA, 1996.

- Mutter, E. Assessment of Contaminant Concentrations and Transport Pathways in Rural Alaska Communities’ Solid Waste and Wastewater Sites; University of Alaska Fairbanks: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation. SB 175 DEC Response to SRES; Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation: Juneau, AK, USA, 2024.

- Zender Environmental Health and Research Group. Results from 12 Waste Stream Characterization Studies; Zender Environmental Health and Research Group: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lung, D.E. Kalskag Solid Waste Characterization Study Report; University of Alaska Fairbanks: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation. Alaska Water and Sewer Challenge (AWSC). Available online: https://dec.alaska.gov/water/water-sewer-challenge/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes; Zender Environmental. LEFT OUT IN THE COLD: Solid Waste Management and the Risks to Resident Health in Native Village Alaska; Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes: Juneau, AK, USA; Zender Environmental: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2003.

- Zender, L.E.; Sebalo, S.; Gilbreath, S. Conditions, Risks, and Contributing Factors of Solid Waste Management in Alaska Native Villages: A Discussion with Case Study. In Proceedings of the Alaska Water and Wastewater Management Association Research and Development Conference, Anchorage, AK, USA, 27–30 April 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zender Environmental Health and Research Group. Alaska Tribal Environmental Justice on Solid Waste Guidance Toolbox; Zender Environmental Health and Research Group: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dinero, S.C. Globalization and Development in a Post-Nomadic Hunter-Gatherer Village: The Case of Arctic Village, Alaska. North. Rev. 2005, 25/26, 135–160. [Google Scholar]

- Dinero, S.C. Globalisation and Development in a Post-Nomadic Hunter/Gatherer Alaskan Village: A Follow-up Assessment. Polar Rec. 2007, 43, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimov, O.A. Predicting Patterns of Near-Surface Air Temperature Using Empirical Data. Clim. Change 2001, 50, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S.; Sturm, M.; Serreze, M.C.; McFadden, J.P.; Key, J.R.; Lloyd, A.H.; McGuire, A.D.; Rupp, T.S.; Lynch, A.H.; Schimel, J.P.; et al. Role of Land-Surface Changes in Arctic Summer Warming. Science 2005, 310, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Euskirchen, E.S.; McGuire, A.D.; Chapin, F.S., III. Energy Feedbacks of Northern High-Latitude Ecosystems to the Climate System Due to Reduced Snow Cover during 20th Century Warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2007, 13, 2425–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovsky, V.E.; Smith, S.L.; Isaksen, K.; Nyland, K.E.; Kholodov, A.L.; Shiklomanov, N.I.; Streletskiy, D.A.; Farquharson, L.M.; Drozdov, D.S.; Malkova, G.V.; et al. Terrestrial Permafrost. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 101, S265–S269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, B.E.; Phillips, J.; Tandon, A.; Maharana, A.; Elmore, R.; Mav, D.; Sedykh, A.; Thayer, K.; Merrick, B.A.; Walker, V.; et al. SWIFT-Active Screener: Accelerated Document Screening through Active Learning and Integrated Recall Estimation. Environ. Int. 2020, 138, 105623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diver, S. Native Water Protection Flows Through Self-Determination: Understanding Tribal Water Quality Standards and Treatment as a State. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 2018, 163, 6–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmer-Pegram, K.C. Resilience to Capitalism, Resilience through Capitalism: Indigenous Communities, Industrialization, and Radical Resilience in Arctic Alaska; University of Alaska Fairbanks: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zender Environmental Health and Research Group. The Relationship between Alaska’s Class III Landfill Status and the USEPA Guidance on the Award and Management of General Assistance Agreements for Tribes and Intertribal Consortia and Its Potential Impact on Remote Alaska Native Tribes and Communities; Zender Environmental Health and Research Group: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shirley, J. The Management of Open Dumps in Rural Alaska-the Continuing Need for Public Health Action: A Policy Analysis; University of Alaska Anchorage: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. FY 2008 Region 10 Tribal Solid and Hazardous Waste Team Report; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2007 Region 10 RCRA Tribal Waste Team Report; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; p. 6.

- Zender Environmental Health and Research Group. Sustainable Statewide Backhaul Program Draft Plan; Zender Environmental Health and Research Group: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J. Composting In Rural Alaska. BioCycle 2011, 52, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Koushki, P.A.; Hulsey, J.L.; Bashaw, E.K. Household Solid Waste: Traits and Disposal Site Selection. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 1997, 123, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, T.L.; Lopez, E.D.S.; Goldberger, R.; Dobson, J.; Hickel, K.; Smith, J.; Johnson, R.M.; Bersamin, A. Consuming Untreated Water in Four Southwestern Alaska Native Communities: Reasons Revealed and Recommendations for Change. J. Environ. Health 2014, 77, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sarcone, J. A Measure and Process for Improving Human Excreta Disposal Practice in Rural Alaska Villages. J. North. Territ. Water Waste Assoc. 2008, 22–25. Available online: https://ntwwa.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Journal_2008_Web.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Wigglesworth, D. Hazardous Waste Management At the Local Level: The Anchorage, Alaska, Experience. J. Environ. Health 1989, 52, 323–326. [Google Scholar]

- Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation. Solid Waste Management for Rural Alaska Operational Guidance; Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation: Juneau, AK, USA, 2021.

- Zender Environmental Health and Research Group. Final Report: Improved Combustion and Emissions for MSW Burn-Management Unit Applicable to Remote Communities in Alaska; Zender Environmental Health and Research Group: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura, H.; Nakazawa, A.T.; Jacobson, T.; Huntman, D.; Blatchford, E.; Wang, S.H.M. Can We Address Village Alaska’s Solid Waste Problem? Taisei Gakuin Univ. Bull. 2014, 16, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The Removal of Home Barrel Burning in the Native Alaskan Villages: Air Quality and Solid Waste Management Success Stories; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 10. Alaska Native Village Air Quality Fact Sheet Series: Solid Waste Burning; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 10: Seattle, WA, USA, 2010.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 10. Alaska Native Village Air Quality Fact Sheet Series: Solid Waste Burning April 2014; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 10: Seattle, WA, USA, 2014.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 10. Koyukuk Landfill Transformation Burn Unit Significantly Reduces Trash and Cleans up Community; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 10: Seattle, WA, USA, 2015.

- Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation. Talking Trash with the ADEC Solid Waste Program; Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation: Juneau, AK, USA, 2021.

- Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes; Zender Environmental Health and Research Group. Guide to Closing Solid Waste Disposal Sites in Alaska Villages; Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes: Juneau, AK, USA; Zender Environmental Health and Research Group: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2001.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 10; Zender Environmental Health and Research Group. Solid Waste Program Budgeting for Alaska Tribal Communities: A Beginner’s Guide; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 10: Seattle, WA, USA; Zender Environmental Health and Research Group: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2018.

- Hinds, C.; LeMay, J.; Stricklan, K. Evaluating Capping Alternatives for an Arctic Landfill. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Cold Regions Engineering, Anchorage, AK, USA, 20–22 May 2012; pp. 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, W.H.I. An Impact Assessment of Current Rural Alaska Village Solid Waste Management Systems: A Case Study. Master of Science Thesis, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, K.; Friedman, H.; Goodale, G. Design Considerations for GCLs Used in Alaska Landfills. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Cold Regions Engineering, Anchorage, AK, USA, 20–22 May 2012; pp. 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation. Burning Waste in Class III Landfills Guidance Document; Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation: Juneau, AK, USA, 2019.

- Gilbreath, S.; Zender, L.E.; Kass, P.H. Self-Reported Health Effects Associated with Solid Waste Disposal in Alaska Native Villages. 2000. Available online: https://sitearchive.zenderdocs.org/docs/health_risks_selfreported.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Liu, W.-L. Thermal Analysis of Landfills. Ph.D. Thesis, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, D.L. Pharmaceutical Trace Study to Identify Microbial Pathogens Sources in and Around Rural Alaskan Waste Sites; Water and Environmental Research Center Annual Technical Report FY 2011; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2011.

- Hanson, J.; Yesiller, N.; Oettle, N. Spatial Variability of Waste Temperatures in MSW Landfills. In Global Waste Management Symposium Proceedings; 2008; pp. 1–11. Available online: https://files01.core.ac.uk/download/pdf/19156395.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Yeşiller, N.; Hanson, J.L.; Oettle, N.K.; Liu, W.-L. Thermal Analysis of Cover Systems in Municipal Solid Waste Landfills. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 2008, 134, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeşiller, N.; Hanson, J.L.; Liu, W.-L. Heat Generation in Municipal Solid Waste Landfills. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 2005, 131, 1330–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, C.; Pegoraro, E.; Bracho, R.; Celis, G.; Crummer, K.G.; Hutchings, J.A.; Hicks Pries, C.E.; Mauritz, M.; Natali, S.M.; Salmon, V.G.; et al. Direct Observation of Permafrost Degradation and Rapid Soil Carbon Loss in Tundra. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textor, S.R.; Wickland, K.P.; Podgorski, D.C.; Johnston, S.E.; Spencer, R.G.M. Dissolved Organic Carbon Turnover in Permafrost-Influenced Watersheds of Interior Alaska: Molecular Insights and the Priming Effect. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickland, K.P.; Neff, J.C.; Aiken, G.R. Dissolved Organic Carbon in Alaskan Boreal Forest: Sources, Chemical Characteristics, and Biodegradability. Ecosystems 2007, 10, 1323–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickland, K.P.; Waldrop, M.P.; Aiken, G.R.; Koch, J.C.; Jorgenson, M.T.; Striegl, R.G. Dissolved Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Release from Boreal Holocene Permafrost and Seasonally Frozen Soils of Alaska. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 065011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bianchi, T.S.; Allison, M.A. Sources of Organic Matter in Sediments of the Colville River Delta, Alaska: A Multi-Proxy Approach. Org. Geochem. 2015, 87, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, T.A.; Turetsky, M.R.; Koven, C.D. Increased Rainfall Stimulates Permafrost Thaw across a Variety of Interior Alaskan Boreal Ecosystems. npj Clim. Atmospheric Sci. 2020, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowles, L.S.; Hossain, A.I.; Aggarwal, S.; Kirisits, M.J.; Saleh, N.B. Water Quality and Associated Microbial Ecology in Selected Alaska Native Communities: Challenges in off-the-Grid Water Supplies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 134450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom, C.A.; Bonnedahl, J.; Woksepp, H.; Hernandez, J.; Olsen, B.; Ramey, A.M. Acquisition and Dissemination of Cephalosporin-Resistant E. Coli in Migratory Birds Sampled at an Alaska Landfill as Inferred through Genomic Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlstrom, C.A.; Bonnedahl, J.; Woksepp, H.; Hernandez, J.; Reed, J.A.; Tibbitts, L.; Olsen, B.; Douglas, D.C.; Ramey, A.M. Satellite Tracking of Gulls and Genomic Characterization of Faecal Bacteria Reveals Environmentally Mediated Acquisition and Dispersal of Antimicrobial-Resistant Escherichia Coli on the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska. Mol. Ecol. 2019, 28, 2531–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, K.N.; Van Daele, L.J. Use of a Garbage Dump by Brown Bears in Dillingham, Alaska. Ursus 2006, 17, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, E.L.; Powell, A.N. Reduction of Garbage in the Diet of Nonbreeding Glaucous Gulls Corresponding to a Change in Waste Management. Arctic 2011, 64, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, M.K. Transport of Fecal Bacteria in a Rural Alaskan Community. In Proceedings of the World Water and Environmental Resources Congress, Anchorage, AK, USA, 15–19 May 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, M.K.; Ford, M.R.; White, D.M.; Barnes, D.L.; Schiewer, S. Transport of Fecal Bacteria by Boots and Vehicle Tires in a Rural Alaskan Community. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunett, J.O. Lateral Movement of Contaminated Ground Water from Merrill Field Landfill, Anchorage, Alaska; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1990.

- Nelson, G. Vertical Movement of Ground Water Under a Landfill, Anchorage, Alaska. In Proceedings of the Seventh National Ground Water Quality Symposium, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26–28 September 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Zenone, C.; Donaldson, D.E.; Grunwaldt, J.J. Ground-Water Quality beneath Solid-Waste Disposal Sites at Anchorage, Alaska. Ground Water 1975, 13, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, J.S. Geohydrology and Ground-Water Geochemistry at a Sub-Arctic Landfill, Fairbanks, Alaska; Water-Resources Investigations Report; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1990; Report 90–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, D.M. Hydrology and Geochemical Processes of a Sub-Arctic Landfill, Fairbanks, Alaska; Basic Data; USGS Numbered Series: Reston, VA, USA; United States Geological Survey, 1985.

- Glass, R.L. Hydrologic Conditions in Connors Bog Area, Anchorage, Alaska; Water-Resources Investigations Report; United States Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 1986.

- Patterson, C.; Davis, M.; Impellitteri, C.; Panguluri, S.; Mutter, E.; Sarcone, J. Fate and Effects of Leachate Contamination on Alaska’s Tribal Drinking Water Sources; Evironmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Mutter, E.A.; Schnabel, W.E.; Duddleston, K.N. Partitioning and Transport Behavior of Pathogen Indicator Organisms at Four Cold Region Solid Waste Sites. J. Cold Reg. Eng. 2017, 31, 04016005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solid Waste Program. Waste Erosion Assessment and Review (WEAR) Final Report; Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation: Juneau, AK, USA, 2015.

- Busby, R.R.; Douglas, T.A.; LeMonte, J.J.; Ringelberg, D.B.; Indest, K.J. Metal Accumulation Capacity in Indigenous Alaska Vegetation Growing on Military Training Lands. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2020, 22, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, A.S.; Kelley, J.J.; Goering, J.J. Three Decades of Investigations on Heavy Metals in Coastal Sediments, North Arctic Alaska: A Synthesis. J. Phys. IV Fr. 2003, 107, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Port Heiden, Alaska Summary of ATSDR’s Public Health Consultation; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Health Consultation: Evaluation of Potential Exposure to Releases from Historical Military Use Area: Port Heiden Lake and Peninsula Borough, Alaska; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019.

- US Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command Northwest. Site Inspection Report for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances at Airstrip Site and Imikpuk Lake; US Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command Northwest: Silverdale, WA, USA, 2021.

- Peek, D.C.; Butcher, M.K.; Shields, W.J.; Yost, L.J.; Maloy, J.A. Discrimination of Aerial Deposition Sources of Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-Dioxin and Polychlorinated Dibenzofuran Downwind from a Pulp Mill near Ketchikan, Alaska. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 1671–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Health Consultation: Evaluation of PCBs Associated with the Former Radio Relay Station Area, Former Fort Morrow, and Other Former Use Areas, Port Heiden, Alaska; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014.

- Sarcone, J. Response to Public Service, Social Justice and Equity, by Dr. Eddie Dunlap. PA Times. 25 February 2013. Available online: https://patimes.org/public-service-socia-justice-equity/#:~:text=One%20Response%20to%20Public%20Service%2C,commentary%2C%20it%20is%20very%20instructive (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Health Consultation: Evaluation of Potential Exposure to Releases from Historical Military Use Area: Port Heiden Lake and Peninsula Borough, Alaska: Supplemental Material to the Health Consultation; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019.

- Gilbreath, S.V.M. Health Effects Associated with Solid Waste Disposal in Alaska Native Villages; University of California Davis: Davis, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, J.L.; Yeşiller, N.; Oettle, N.K. Spatial and Temporal Temperature Distributions in Municipal Solid Waste Landfills. J. Environ. Eng. 2010, 136, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbreath, S.; Kass, P.H. Adverse Birth Outcomes Associated with Open Dumpsites in Alaska Native Villages. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 164, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbreath, S.; Kass, P. Fetal and Neonatal Deaths and Congenital Anomalies Associated with Open Dumpsites in Alaska Native Villages. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2006, 65, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBeth, S. Socioeconomic and Environmental Causes for Respiratory Infection Death in Alaska Native Villages. Master of Public Health Thesis, Wright State University, Dayton, OH, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service. Report on the Status of Open Dumps on Indian Lands; Indian Health Service: Rockville, MD, USA, 1998.

- Hart, C.; White, D. Water Quality and Construction Materials in Rainwater Catchments across Alaska. J. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2006, 5, S19–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contaminants of Emerging Concern in the Environment: Ecological and Human Health Considerations, 1st ed.; Halden, R., Ed.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8412-2496-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Zhao, H.; Peter, K.T.; Gonzalez, M.; Wetzel, J.; Wu, C.; Hu, X.; Prat, J.; Mudrock, E.; Hettinger, R.; et al. A Ubiquitous Tire Rubber–Derived Chemical Induces Acute Mortality in Coho Salmon. Science 2021, 371, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, P.M.; Moran, K.D.; Miller, E.L.; Brander, S.M.; Harper, S.; Garcia-Jaramillo, M.; Carrasco-Navarro, V.; Ho, K.T.; Burgess, R.M.; Thornton Hampton, L.M.; et al. Where the Rubber Meets the Road: Emerging Environmental Impacts of Tire Wear Particles and Their Chemical Cocktails. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 171153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itchuaqiyaq, C.U.; Lindgren, C.A.; Kramer, C.Q. Decolonizing Community-Engaged Research: Designing CER with Cultural Humility as a Foundational Value. Commun. Des. Q. Rev. 2023, 11, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeny, B.; Bosurgi, R. Time to End Parachute Science. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1004099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanoudis, P.V.; Licuanan, W.Y.; Morrison, T.H.; Talma, S.; Veitayaki, J.; Woodall, L.C. Turning the Tide of Parachute Science. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R184–R185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yua, E.; Raymond-Yakoubian, J.; Daniel, R.; Behe, C. A Framework for Co-Production of Knowledge in the Context of Arctic Research. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.S.J.; Around Him, D. Conducting Research “in a Good Way”: Relationships as the Foundation of Research. Arct. Sci. 2025, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David-Chavez, D.M.; Gavin, M.C.; Ortiz, N.; Valdez, S.; Carroll, S.R. A Values-Centered Relational Science Model: Supporting Indigenous Rights and Reconciliation in Research. Ecol. Soc. 2024, 29, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.E.; Volpert-Esmond, H.I.; Deen, J.F.; Modde, E.; Warne, D. Stress and Cardiometabolic Disease Risk for Indigenous Populations throughout the Lifespan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, M.L.; Whitbeck, L.B. Distress among Indigenous North Americans: Generalized and Culturally Relevant Stressors. Soc. Ment. Health 2011, 1, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbeck, L.B.; Walls, M.L.; Johnson, K.D.; Morrisseau, A.D.; McDougall, C.M. Depressed Affect and Historical Loss Among North American Indigenous Adolescents. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 2009, 16, 16–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redwood, D.G.; Ferucci, E.D.; Schumacher, M.C.; Johnson, J.S.; Lanier, A.P.; Helzer, L.J.; Tom-Orme, L.; Murtaugh, M.A.; Slattery, M.L. Traditional Foods and Physical Activity Patterns and Associations with Cultural Factors in a Diverse Alaska Native Population. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2008, 67, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuura, H.; Lung, D.E.; Nakazawa, A. Commentary: Solid Waste as It Impacts Community Sustainability in Alaska. J. Rural Community Dev. 2008, 3, 108–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bersamin, A.; Luick, B.R.; King, I.B.; Stern, J.S.; Zidenberg-Cherr, S. Westernizing Diets Influence Fat Intake, Red Blood Cell Fatty Acid Composition, and Health in Remote Alaskan Native Communities in the Center for Alaska Native Health Study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.M.; Nash, S.H.; Hopkins, S.E.; Boyer, B.B.; Obrien, D.M.; Bersamin, A. Diet Quality Is Positively Associated with Intake of Traditional Foods and Does Not Differ by Season in Remote Yup’ik Communities. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2023, 82, 2221370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryman, T.K.; Boyer, B.B.; Hopkins, S.; Philip, J.; Beresford, S.A.A.; Thompson, B.; Heagerty, P.J.; Pomeroy, J.J.; Thummel, K.E.; Austin, M.A. Associations between Diet and Cardiometabolic Risk among Yup’ik Alaska Native People Using Food Frequency Questionnaire Dietary Patterns. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, R.; Landrigan, P.J.; Balakrishnan, K.; Bathan, G.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Brauer, M.; Caravanos, J.; Chiles, T.; Cohen, A.; Corra, L.; et al. Pollution and Health: A Progress Update. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e535–e547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Tribal Toxics Council. Re: Di-Isodecyl Phthalate (DIDP) and Diisononyl Phthalate (DINP); Science Advisory Committee on Chemicals (SACC) Peer Review of Draft Documents; Notice of SACC Meeting; Availability; and Request for Comment; National Tribal Toxics Council: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chaney, C.; Moore-Nall, A.; Albert, C.; Beebe, C.; Bierwagen, B.; Davis, M.; Demoski, A.; Ip, A.; Jordan, P.; Lee, S.S.; et al. Scoping Review of the Environmental and Human Health Effects of Rural Alaska Landfills. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010045

Chaney C, Moore-Nall A, Albert C, Beebe C, Bierwagen B, Davis M, Demoski A, Ip A, Jordan P, Lee SS, et al. Scoping Review of the Environmental and Human Health Effects of Rural Alaska Landfills. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaney, Carlye, Anita Moore-Nall, Chad Albert, Catherine Beebe, Britta Bierwagen, Michelle Davis, Alice Demoski, Angel Ip, Page Jordan, Sylvia S. Lee, and et al. 2026. "Scoping Review of the Environmental and Human Health Effects of Rural Alaska Landfills" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010045

APA StyleChaney, C., Moore-Nall, A., Albert, C., Beebe, C., Bierwagen, B., Davis, M., Demoski, A., Ip, A., Jordan, P., Lee, S. S., Mutter, E., Oliver, L., Rallo, N., Schofield, K., Seetot, J., Shugak, A., Tom, A., Turner, M., & Zender, L. (2026). Scoping Review of the Environmental and Human Health Effects of Rural Alaska Landfills. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010045