Resilience and Aging Among Black Gay and Bisexual Older Men

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research on Black Gay and Bisexual Older Men

1.2. Resilience and Social Determinants of Health

1.3. Resilience Among Gay and Bisexual Men

1.4. Intersectionality and Power, Justice, and Critical Consciousness

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

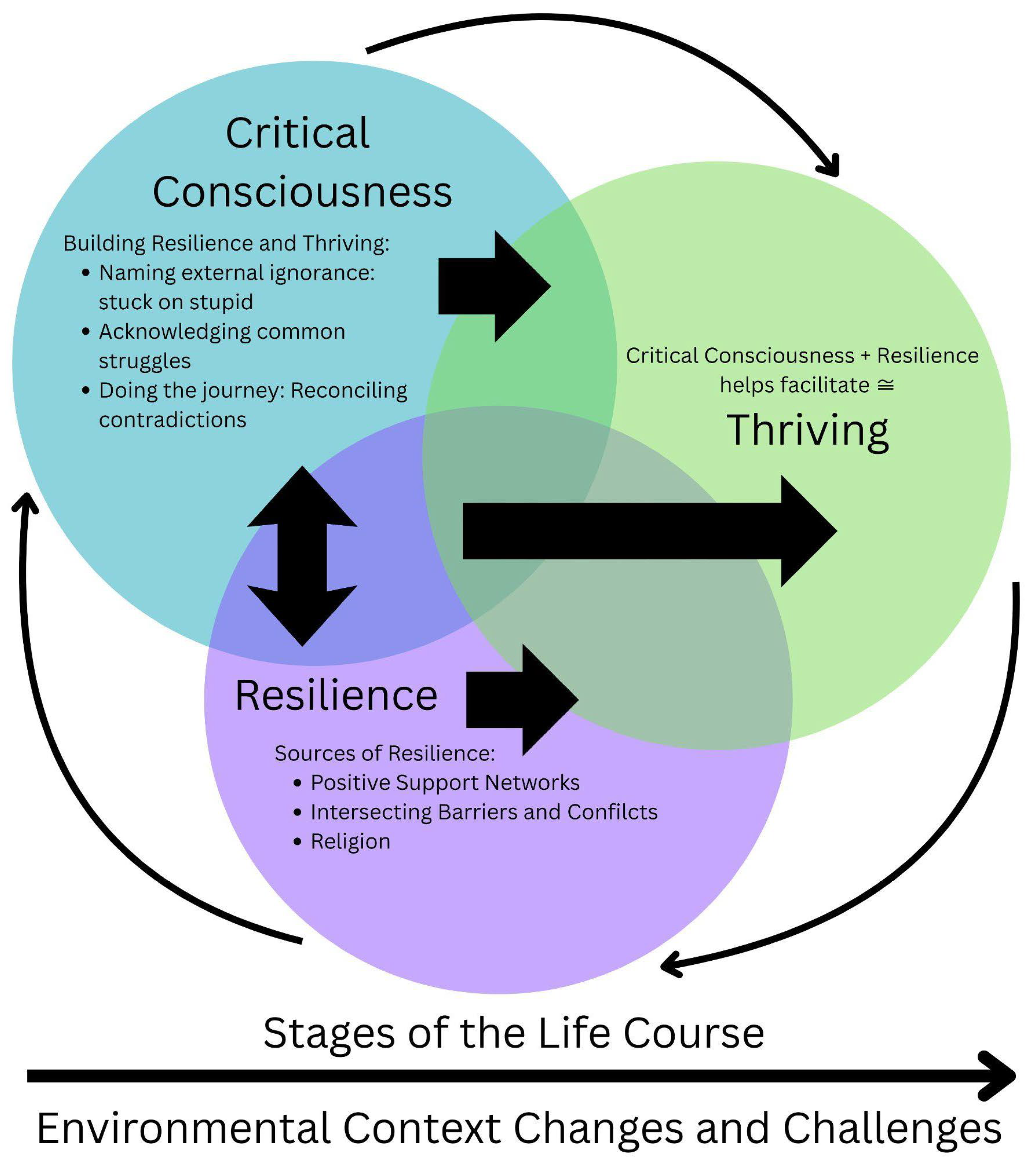

3. Findings

3.1. Sources of Resilience

3.1.1. Positive Support Networks

3.1.2. Intersecting Barriers and Conflict

3.1.3. Religion

3.2. Building Resilience and Thriving Through Critical Consciousness

3.2.1. Naming External Ignorance: Stuck on Stupid

3.2.2. Acknowledging Common Struggles

3.2.3. Doing the Journey: Reconciling Contradictions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thimm-Kaiser, M.; Benzekri, A.; Guilamo-Ramos, V. Conceptualizing the Mechanisms of Social Determinants of Health: A Heuristic Framework to Inform Future Directions for Mitigation. Milbank Q. 2023, 101, 486–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, D.H.; Snipes, S.A.; Chung, K.W.; Martz, C.D.; LaVeist, T.A. Vulnerability and Resilience: Use and Misuse of These Terms in the Public Health Discourse. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1736–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilamo-Ramos, V.; Thimm-Kaiser, M.; Benzekri, A.; Johnson, C.; Williams, D.; Wilhelm-Hilkey, N.; Goodman, M.; Hagan, H. Application of a Heuristic Framework for Multilevel Interventions to Eliminate the Impact of Unjust Social Processes and Other Harmful Social Determinants of Health. Prev. Sci. 2024, 25, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perone, A.K.; Urrutia-Pujana, L.; Zhou, L.; Yaisikana, M.; Mendez Campos, B. The Equitable Aging in Health Conceptual Framework: International Interventions Infusing Power and Justice to Address Social Isolation and Loneliness among Older Adults. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1426015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Integrating the Social Determinants of Health into Health Workforce Education and Training, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Panter-Brick, C.; Leckman, J.F. Editorial Commentary: Resilience in Child Development—Interconnected Pathways to Wellbeing. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill Collins, P.; Bilge, S. Intersectionality; Key Concepts; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P.C. Silence Equals Death: The Response to Aids within Communities of Color. Univ. Ill. Law Rev. 1992, 1992, 1075. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson, J. The Secret Epidemic: The Story of AIDS and Black America, 1st ed.; Anchor Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Perone, A.K. Barriers and Opportunities for Nontraditional Social Work during COVID-19: Reflections from a Small LGBTQ+ Nonprofit in Detroit. Qual. Soc. Work 2021, 20, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handlovsky, I.; Bungay, V.; Oliffe, J.; Johnson, J. Developing Resilience: Gay Men’s Response to Systemic Discrimination. Am. J. Mens Health 2018, 12, 1473–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kum, S. Gay, Gray, Black, and Blue: An Examination of Some of the Challenges Faced by Older LGBTQ People of Color. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2017, 21, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mange, T.; Henderson, N.; Lukelelo, N. “After 25 Years of Democracy We Are Still Stigmatized and Discriminated Against…”: Health Care Experiences of HIV Positive Older Black Gay Men in a Township in South Africa. J. Pract. Teach. Learn. 2022, 19, 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.D.M.; Harper, G.W.; Hidalgo, M.A.; Jamil, O.B.; Torres, R.S.; Isabel Fernandez, M.; Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Negotiating Dominant Masculinity Ideology: Strategies Used by Gay, Bisexual and Questioning Male Adolescents. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2010, 45, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.W.; Tyler, A.T.; Bruce, D.; Graham, L.; Wade, R.M.; Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Drugs, Sex, and Condoms: Identification and Interpretation of Race-Specific Cultural Messages Influencing Black Gay and Bisexual Young Men Living with HIV. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 58, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, S.; Knight, B.G. Stress and Coping among Gay Men: Age and Ethnic Differences. Psychol. Aging 2008, 23, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haile, R.; Padilla, M.B.; Parker, E.A. ‘Stuck in the Quagmire of an HIV Ghetto’: The Meaning of Stigma in the Lives of Older Black Gay and Bisexual Men Living with HIV in New York City. Cult. Health Sex. 2011, 13, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, G.W.; Bruce, D.; Hosek, S.G.; Fernandez, M.I.; Rood, B.A. Resilience Processes Demonstrated by Young Gay and Bisexual Men Living with HIV: Implications for Intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2014, 28, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.J.; Miller, R.L. Thriving and Adapting: Resilience, Sense of Community, and Syndemics among Young Black Gay and Bisexual Men. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 57, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I.; Emlet, C.A.; Kim, H.-J.; Muraco, A.; Erosheva, E.A.; Goldsen, J.; Hoy-Ellis, C.P. The Physical and Mental Health of Lesbian, Gay Male, and Bisexual (LGB) Older Adults: The Role of Key Health Indicators and Risk and Protective Factors. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Lifetime Risk of HIV Diagnosis in the United States: Half of Black Gay Men and a Quarter of Latino Gay Men Projected to Be Diagnosed Within Their Lifetime; Press Release; National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, 2016. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20180731174532/https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2016/croi-press-release-risk.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I. Resilience and Disparities among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Older Adults. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2011, 21, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esiaka, D.; Cheng, A.; Nwakasi, C. Sexuality in Later Life and Mental Health Among Older Black Gay Men. Innov. Aging 2020, 4 (Suppl. S1), 313–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perone, A.K.; Ingersoll-Dayton, B.; Watkins-Dukhie, K. Social Isolation Loneliness Among LGBT Older Adults: Lessons Learned from a Pilot Friendly Caller Program. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2020, 48, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calo, M.; Judd, B.; Peiris, C. Grit, Resilience and Growth-Mindset Interventions in Health Professional Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Educ. 2024, 58, 902–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, D.N.; Wingate, L.R.; Cole, A.B.; O’Keefe, V.M.; Hollingsworth, D.W.; Davidson, C.L.; Hirsch, J.K. The Common Factors of Grit, Hope, and Optimism Differentially Influence Suicide Resilience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffel, J.M.; Cain, J. Review of Grit and Resilience Literature within Health Professions Education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 82, 6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çalışkan, E.; Gökkaya, F. Reviewing Psychological Practices to Enhance the Psychological Resilience Process for Individuals with Chronic Pain: Clinical Implications and Neurocognitive Findings. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2025, 29, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emlet, C.A.; Shiu, C.; Kim, H.-J.; Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. Bouncing Back: Resilience and Mastery Among HIV-Positive Older Gay and Bisexual Men. Gerontologist 2017, 57 (Suppl. S1), S40–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, J.M.; Abu-Rish Blakeney, E.; Corage Baden, A.; Freeman, V.; Yi-Frazier, J.; Curtis, J.R.; Engelberg, R.A.; Rosenberg, A.R. Definitions of Resilience and Resilience Resource Use as Described by Adults with Congenital Heart Disease. Int. J. Cardiol. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2023, 12, 100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Westphal, M.; Mancini, A.D. Resilience to Loss and Potential Trauma. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 7, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hephsebha, J.; Deb, A. Introducing Resilience Outcome Expectations: New Avenues for Resilience Research and Practice. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2024, 9, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.; Sciolla, A.; Rea, M.; Sandholdt, C.; Jandrey, K.; Rice, E.; Yu, A.; Griffin, E.; Wilkes, M. Modeling the Social Determinants of Resilience in Health Professions Students: Impact on Psychological Adjustment. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2023, 28, 1661–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Resilience in the Study of Minority Stress and Health of Sexual and Gender Minorities. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeasmin, S.; Infanti, J.J. Resilience amid Adversity: A Qualitative Narrative Study of Childhood Sexual Abuse Among Bangladeshi Transgender Individuals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, L.; Darnell, D.A.; Rhew, I.C.; Lee, C.M.; Kaysen, D. Resilience in Community: A Social Ecological Development Model for Young Adult Sexual Minority Women. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 55, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, D.; Lv, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Li, P. Effects of Resilience-Promoting Interventions on Cancer Patients’ Positive Adaptation and Quality of Life: A Meta-Analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2023, 46, E343–E354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Dandeneau, S.; Marshall, E.; Phillips, M.K.; Williamson, K.J. Rethinking Resilience from Indigenous Perspectives. Can. J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurischa, S.D.; Fahmi, F.Z.; Suroso, D.S.A. Transformative Resilience: Transformation, Resilience and Capacity of Coastal Communities in Facing Disasters in Two Indonesian Villages. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 88, 103615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.A.; Meyer, I.H.; Antebi-Gruszka, N.; Boone, M.R.; Cook, S.H.; Cherenack, E.M. Profiles of Resilience and Psychosocial Outcomes among Young Black Gay and Bisexual Men. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 57, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.E. Have We Gone Too Far with Resiliency? Soc. Work Res. 2014, 38, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, L.; Jerneck, A.; Thoren, H.; Persson, J.; O’Byrne, D. Why Resilience Is Unappealing to Social Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations of the Scientific Use of Resilience. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1400217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picq, M.L.; Thiel, M. International LGBTQ+ Politics Today: Moving beyond ‘Crises’? Int. Polit. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M. Resilience as an Attribute of the Developmental System: Comments on the Papers of Professors Masten & Wachs. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1094, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurse, S.; Dasent, K.; Rivera, A.; Ansah, J.P.; Black, J. Beyond Rugged Individualism?: Exploring the Resilience of Black Entrepreneurs to Chronic Racism. J. Manag. Stud. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; McLean, K.C.; Taylor, B.; Swartout, K.; Querna, K. Beyond Resilience: Why We Need to Look at Systems Too. Psychol. Violence 2016, 6, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M. The Social Ecology of Resilience: Addressing Contextual and Cultural Ambiguity of a Nascent Construct. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorobyova, A.; Van Tuyl, R.; Cardinal, C.; Marante, A.; Magagula, P.; Lyndon, S.; Parashar, S. “I’m Positively Positive”: Beyond Individual Responsibility for Resilience amongst Older Adults Living with HIV. SSM—Qual. Res. Health 2022, 2, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, A.D.; Hunter, C.D. Counterspaces: A Unit of Analysis for Understanding the Role of Settings in Marginalized Individuals’ Adaptive Responses to Oppression. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 50, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.H. Counterspaces as Sites of Fostering and Amplifying Community College Latinas’ Resistance Narratives in STEM. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2025, 18, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, J.; Cocking, C.; Reicher, S. The Nature of Collective Resilience: Survivor Reactions to the 2005 London Bombings. Int. J. Mass Emerg. Disasters 2009, 27, 66–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, B.; Xu, C.; Zhao, M.; Guo, J. Characteristics of Collective Resilience and Its Influencing Factors from the Perspective of Psychological Emotion: A Case Study of COVID-19 in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Stevens, S.P.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.F.; Pfefferbaum, R.L. Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, S.B.; Baker, C.K.; Barile, J.P. Rebuild or Relocate? Resilience and Postdisaster Decision-Making After Hurricane Sandy. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 56, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.-J.; Huang, F.-T. Building Community Resilience via Developing Community Capital toward Sustainability: Experiences from a Hakka Settlement in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, A.E.; Welsh, E.; Carrillo, A.; Talwar, G.; Scheibler, J.; Butler, T. Between Synergy and Conflict: Balancing the Processes of Organizational and Individual Resilience in an Afghan Women’s Community. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 47, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.C.; Stewart, R. Resilience and Sub-Optimal Social Determinants of Health: Fostering Organizational Resilience in the Medical Profession. Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2023, 50, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popay, J.; Kaloudis, H.; Heaton, L.; Barr, B.; Halliday, E.; Holt, V.; Khan, K.; Porroche-Escudero, A.; Ring, A.; Sadler, G.; et al. System Resilience and Neighbourhood Action on Social Determinants of Health Inequalities: An English Case Study. Perspect. Public Health 2022, 142, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnette, C.E.; Boel-Studt, S.; Renner, L.M.; Figley, C.R.; Theall, K.P.; Miller Scarnato, J.; Billiot, S. The Family Resilience Inventory: A Culturally Grounded Measure of Current and Family-of-Origin Protective Processes in Native American Families. Fam. Process 2020, 59, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Chan, A.P.C. The Impact of Coping Strategies and Individual Resilience on Anxiety and Depression among Construction Supervisors. Buildings 2022, 12, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witter, S.; Thomas, S.; Topp, S.M.; Barasa, E.; Chopra, M.; Cobos, D.; Blanchet, K.; Teddy, G.; Atun, R.; Ager, A. Health System Resilience: A Critical Review and Reconceptualisation. Lancet Glob. Health 2023, 11, e1454–e1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, R.G.; LeBlanc, A.J.; de Vries, B.; Detels, R. Stress and Mental Health Among Midlife and Older Gay-Identified Men. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, B.; Neville, S.; Adams, J. Perceptions of Ageing as an Older Gay Man: A Qualitative Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 3388–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustanski, B.; Newcomb, M.E.; Garofalo, R. Mental Health of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youths: A Developmental Resiliency Perspective. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2011, 23, 204–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranuschio, B.; Bell, S.; Waldron, J.M.; Barnes, L.; Sheik-Yosef, N.; Villalobos, E.; Wackens, J.; Liboro, R.M. Promoting Resilience among Middle-Aged and Older Men Who Have Sex with Men Living with HIV/AIDS in Southern Nevada: An Examination of Facilitators and Challenges from a Social Determinants of Health Perspective. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, S.; Jude, B.; McLachlan, A.J. Sense of Belonging to the General and Gay Communities as Predictors of Depression among Australian Gay Men. Int. J. Mens Health 2008, 7, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, S. The Relationship between Living Alone and Depressive Symptoms among Older Gay Men: The Moderating Role of Sense of Belonging with Gay Friends. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 1895–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battle, J.; Daniels, J.; Pastrana, A.; Turner, C. Never Too Old To Feel Good: Happiness and Health among a National Sample of Older Black Gay Men. Spectr. J. Black Men 2013, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.D.; Richardson, V.E. Influence of Income, Being Partnered/Married, Resilience, and Discrimination on Mental Health Distress for Midlife and Older Gay Men: Mental Health Distress among Midlife and Older Gay Men: The Importance of Partners and Resilience. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2016, 20, 127–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.M.; Telfer, N.A.; Artis, J.; Abubakare, O.; Keller-Bell, Y.D.; Caruthers, C.; Jones, D.R.; Pierce, N.P. Resilience and Strengths in the Black Autism Community in the United States: A Scoping Review. Autism Res. 2024, 17, 2198–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattlebaum, M.; Wilson, D.K.; Simmons, T.; Martin, P.P. Systematic Review of Family-Based Interventions Integrating Cultural and Family Resilience Components to Improve Black Adolescent Health Outcomes. Ann. Behav. Med. 2025, 59, kaae079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.C.; Threats, M.; Blackburn, N.A.; LeGrand, S.; Dong, W.; Pulley, D.V.; Sallabank, G.; Harper, G.W.; Hightow-Weidman, L.B.; Bauermeister, J.A.; et al. “Stay Strong! Keep Ya Head up! Move on! It Gets Better‼‼”: Resilience Processes in the healthMpowerment Online Intervention of Young Black Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Care 2018, 30 (Suppl. 5), S27–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follins, L.D.; Garrett-Walker, J.J.; Lewis, M.K. Resilience in Black Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Individuals: A Critical Review of the Literature. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2014, 18, 190–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen, S.A.; Jones, M.; Moore, S.; Hood, J.; Smith, J.C.; Camacho-Gonzalez, A.; del Rio, C.; Harper, G.W. Brothers Building Brothers by Breaking Barriers: Development of a Resilience-Building Social Capital Intervention for Young Black Gay and Bisexual Men Living with HIV. AIDS Care 2018, 30 (Suppl. S4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, O.S.; Gipson, J.A.; Denson, D.; Thompson, D.V.; Sutton, M.Y.; Hickson, D.A. The Associations of Resilience and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Black Gay, Bisexual, Other Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) in the Deep South: The MARI Study. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, K.G.; Dickson-Gomez, J.; Pearson, B.; Marion, E.; Amikrhanian, Y.; Kelly, J.A. Intersectional Resilience Among Black Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex With Men, Wisconsin and Ohio, 2019. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, S405–S412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. The Problem With the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—an Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perone, A.K.; Toman, L.; Glover Reed, B.; Coldon, T.; Osborne, A.; Cook, J. Aging and Mentorship in the Margins: Multigenerational Knowledge Transfer Among LGBTQ+ Chosen Families. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2025, 80, gbaf027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, A.-M. When Multiplication Doesn’t Equal Quick Addition: Examining Intersectionality as a Research Paradigm. Perspect. Polit. 2007, 5, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, B.T.; Kohlman, M.H. Intersectionality: A Transformative Paradigm in Feminist Theory and Social Justice. In Handbook of Feminist Research: Theory and Praxis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzanka, P.R. (Ed.) Intersectionality: Foundations and Frontiers, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Collins, P. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; Revision Tenth Anniversary, Ed.; Perspectives on Gender; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, 1st ed.; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mullaly, R.P.; West, J. Challenging Oppression and Confronting Privilege: A Critical Approach to Anti-Oppressive and Anti-Privilege Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Don Mills, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Prilleltensky, I. Wellness as Fairness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 49, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, P. Education for Critical Consciousness; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P.; Macedo, D.P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition, 30th ed.; Ramos, M.B., Translator; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer, M.A.; Blustein, D.L. Critical Consciousness and Career Development among Urban Youth. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemer, M.A.; McWhirter, E.H.; Ozer, E.J.; Rapa, L.J. Advances in the Conceptualization and Measurement of Critical Consciousness. Urban Rev. 2015, 47, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, J.; Lee, W.; Choi, E.Y.; Jang, S.G.; Ock, M. Qualitative Research in Healthcare: Necessity and Characteristics. J. Prev. Med. Pub. Health 2023, 56, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, L. The Complexity of Intersectionality. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2005, 30, 1771–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redden, M.; Gahagan, J.; Kia, H.; Humble, Á.M.; Stinchcombe, A.; Manning, E.; Ecker, J.; de Vries, B.; Gambold, L.L.; Oliver, B.; et al. Housing as a Determinant of Health for Older LGBT Canadians: Focus Group Findings from a National Housing Study. Hous. Soc. 2023, 50, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, R.S.; Morgan, D.L. (Eds.) A New Era in Focus Group Research; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Immel, M.; Fisher, A.; Hale, T.M.; Jethwani, K.; Centi, A.J.; Linscott, B.; Boerner, K. Understanding the Role of Virtual Outreach and Programming for LGBT Individuals in Later Life. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2022, 65, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinner, L.; Holman, D.; Ejegi-Memeh, S.; Laverty, A.A. Use of Intersectionality Theory in Interventional Health Research in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgen, A.; Nasir, A.; Schöneberg, J. Why Positionalities Matter: Reflections on Power, Hierarchy, and Knowledges in “Development” Research. Can. J. Dev. Stud. Rev. Can. Détudes Dév. 2021, 42, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresnoza-Flot, A.; Cheung, H. Temporal Contextuality of Agentic Intersectional Positionalities: Nuancing Power Relations in the Ethnography of Minority Migrant Women. Qual. Res. 2024, 24, 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.F.; Goodkind, S.; Diaz, M.; Karandikar, S.; Beltrán, R.; Kim, M.E.; Zelnick, J.R.; Gibson, M.F.; Mountz, S.; Miranda Samuels, G.E.; et al. Positionality in Critical Feminist Scholarship: Situating Social Locations and Power Within Knowledge Production. Affilia 2024, 39, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, D.E. Reflections of a Chicano Social Scientist. Lat. Stud. 2023, 21, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, B.G.; Jiwatram-Negrón, T.; Gonzalez Benson, O.; Gant, L.M. Enacting Critical Intersectionality in Research: A Challenge for Social Work. Soc. Work Res. 2021, 45, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D.M. Transformative Mixed Methods: Addressing Inequities. Am. Behav. Sci. 2012, 56, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 2015, 1989, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Z.D.; Feldman, J.M.; Bassett, M.T. How Structural Racism Works—Racist Policies as a Root Cause of U.S. Racial Health Inequities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, H.; Banerjee, D. Successful Aging Among Older LGBTQIA+ People: Future Research and Implications. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 756649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia, C.I.; Saunders, D.; Daw, J.; Vasquez, A. DNA Methylation Accelerated Age as Captured by Epigenetic Clocks Influences Breast Cancer Risk. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1150731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, J.M.; Krentz, H.; Gill, M.J.; Hogan, D.B. Managing HIV Infection in Patients Older than 50 Years. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2018, 190, E1253–E1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akusjärvi, S.S.; Neogi, U. Biological Aging in People Living with HIV on Successful Antiretroviral Therapy: Do They Age Faster? Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2023, 20, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaraldi, G.; Orlando, G.; Zona, S.; Menozzi, M.; Carli, F.; Garlassi, E.; Berti, A.; Rossi, E.; Roverato, A.; Palella, F. Premature Age-Related Comorbidities Among HIV-Infected Persons Compared With the General Population. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karady, J.; Lu, M.T.; Bergström, G.; Mayrhofer, T.; Taron, J.; Foldyna, B.; Paradis, K.; McCallum, S.; Aberg, J.A.; Currier, J.S.; et al. Coronary Plaque in People With HIV vs Non-HIV Asymptomatic Community and Symptomatic Higher-Risk Populations. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 100968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, J.L.; Leyden, W.A.; Alexeeff, S.E.; Anderson, A.N.; Hechter, R.C.; Hu, H.; Lam, J.O.; Towner, W.J.; Yuan, Q.; Horberg, M.A.; et al. Comparison of Overall and Comorbidity-Free Life Expectancy Between Insured Adults With and Without HIV Infection, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e207954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, R. Doing Focus Groups; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D.L. Focus Groups and Social Interaction. In The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perone, A.K. Constructing Discrimination Rights: Comparisons Among Staff in Long-Term Care Health Facilities. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perone, A.K. Navigating Religious Refusal to Nursing Home Care for LGBTQ+ Residents: Comparisons Between Floor Staff and Managers. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2024, 79, gbae122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedoose, Cloud Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data, version 9.0.107; SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2023.

- Houben, F.; van Hensbergen, M.; Heijer, C.D.J.D.; Dukers-Muijrers, N.H.T.M.; Hoebe, C.J.P.A. Barriers and Facilitators to Infection Prevention and Control in Dutch Residential Care Facilities for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A Theory-Informed Qualitative Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portacolone, E.; Rubinstein, R.L.; Covinsky, K.E.; Halpern, J.; Johnson, J.K. The Precarity of Older Adults Living Alone With Cognitive Impairment. Gerontologist 2019, 59, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin-Baden, M.; Major, C.H. Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mihas, P. Memo Writing. In Expanding Approaches to Thematic Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Flores, O.; Otero-Oyague, D.; Rey-Evangelista, L.; Zevallos-Morales, A.; Ramos-Bonilla, G.; Carrión, I.; Patiño, V.; Pollard, S.L.; Parodi, J.F.; Hurst, J.R.; et al. Agency and Mental Health Among Peruvian Older Adults During the COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2023, 78, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowers, J.; Datcher, I.; Kavalieratos, D.; Hepburn, K.; Perkins, M.M. Proactive Care-Seeking Strategies Among Adults Aging Solo With Early Dementia: A Qualitative Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2024, 79, gbae020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Positionality * | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Race and Ethnicity | Black or African American (16); African (1); Caucasian/White (2); Native American, American Indian, Alaskan, Native, First Nations (2); Multiracial (2); Blackfoot (1); French (1) |

| Gender | Male (17), Two-Spirit (1), Androgynous (1) |

| Sexual Orientation | Gay (14), Bisexual (1), Asexual (1), Same gender attraction (1), Enjoy men (1), Attracted to men (gay), like what I like! (1) |

| Age | Mean (55.35) Standard Deviation (9.151) Range (39–74) |

| Religion | None (5), Catholic (2), Islam (1), Christian (3), Buddhism (1), Protestant (5), Jehovah’s Witness (1), Episcopalian (1), Baptist (4), “Very Religious/Spiritual (Undefined)” (1), Nondenominational (1) |

| Highest Educational Attainment | High School Diploma/G.E.D. (8), Associate’s Degree/Some College (3), Bachelor’s Degree (4), Master’s Degree (4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perone, A.K.; Reed, B.G.; Gant, L.M. Resilience and Aging Among Black Gay and Bisexual Older Men. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1226. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081226

Perone AK, Reed BG, Gant LM. Resilience and Aging Among Black Gay and Bisexual Older Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1226. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081226

Chicago/Turabian StylePerone, Angela K., Beth Glover Reed, and Larry M. Gant. 2025. "Resilience and Aging Among Black Gay and Bisexual Older Men" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1226. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081226

APA StylePerone, A. K., Reed, B. G., & Gant, L. M. (2025). Resilience and Aging Among Black Gay and Bisexual Older Men. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1226. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081226