Risky Play Is Not a Dirty Word: A Tool to Measure Benefit–Risk in Outdoor Playgrounds and Educational Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

“The concept which acknowledges that in sports and recreation there is an inevitable and inherent trade-off between the benefits of a sport or recreational activity, and some of the risks which they can pose.”

“We have made the playground so monumentally boring that any self-respecting child will go somewhere else to play, somewhere more interesting, and usually more dangerous.”

“Children need and want to take risks when they play. Play provision aims to respond to these needs and wishes by offering children stimulating, challenging environments for exploring and developing their abilities. In doing this, play provision aims to manage the level of risk so that children are not exposed to unacceptable risks of death or serious injury.”

“The primary aim of a playground should be to stimulate a child’s imagination, provide excitement and adventure in safe surroundings, and allow scope for children to develop their own ideas of play. Ideally playgrounds should encourage development of motor skills and present users with manageable challenges to develop physical skills and to find and test their limits. In order to provide these challenges, a balance must be found between risk and safety. Professional advice should be sought, and children should be involved in planning, to ensure that the playground satisfies children’s ideas of play.”

“Risk-taking is an essential feature of play provision and of all environments in which children legitimately spend time playing. Play provision aims to offer children the chance to encounter acceptable risks as part of a stimulating, challenging and controlled learning environment. Play provision should aim at managing the balance between the need to offer risk and the need to keep children safe from serious harm…Respecting the characteristics of children’s play and the way children benefit from playing on the playground with regard to development; children need to learn to cope with risk. This may lead to bumps and bruises and even occasionally a broken limb. The aim of this standard is first and foremost to prevent accidents with a disabling or fatal consequence, and secondly to lessen serious consequences caused by the occasional mishap that inevitably will occur in children’s pursuit of expanding their level of competence, be it socially, intellectually or physically.”

“Play is a significant aspect of children’s lives through which they develop and demonstrate knowledge, skills, concepts and dispositions. It is an important context for all aspects of children’s learning and development including problem-solving, social-emotional development, the acquisition and mastery of physical skills, self-awareness, imaginative abilities, exploration of natural environments, and relaxation. Consideration of play provision should not be limited to formally-equipped areas but also extend to natural elements. Provision should also be made to cater for the needs and interests of users of all abilities.It is important to recognise the value to children of engaging with nature. The incorporation of natural materials as design elements in a playground can add significant play, aesthetic and environmental value.Natural elements incorporated into playgrounds are inherently diverse and open-ended, and many offer the benefit that children can manipulate them for their own play purposes. Such nature-based play environments can help build creativity, imagination and problem-solving skills. Access to nature has been shown to improve children’s psychological well-being and encourage stewardship of the environment.It should be recognised that risk taking is an essential feature of play provision and of all environments in which children legitimately spend time playing. Play provision aims to offer children the chance to encounter acceptable risks as part of a stimulating and challenging learning environment. Play provision should aim at managing the balance between the need to offer risk and the need to keep children safe from serious harm.”

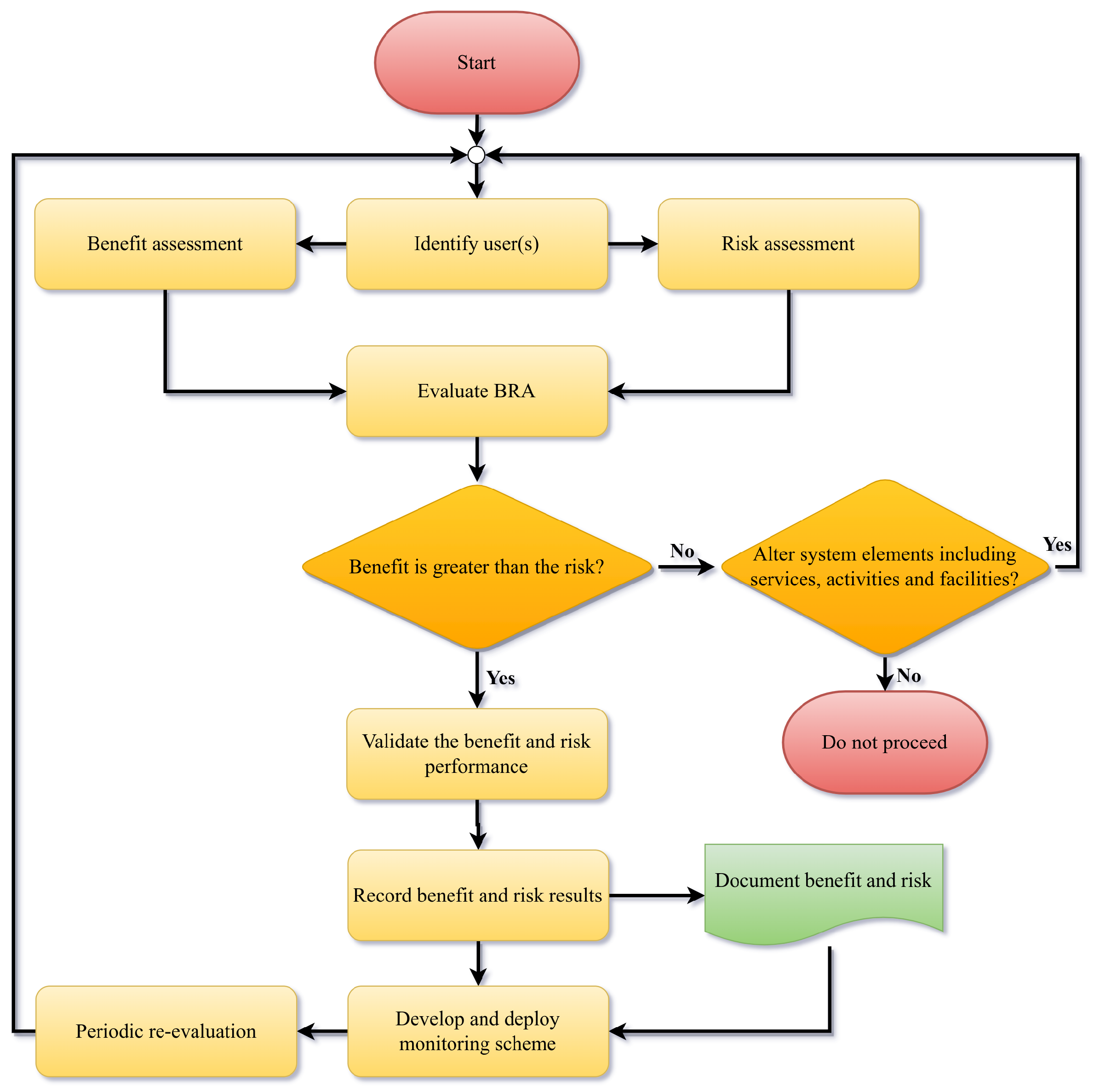

2. Methodology

“Risks where consequences are positive can be recorded in the same document as those where consequences are negative or separately. Opportunities (which are circumstances or ideas that could be exploited rather than chance events) are generally recorded separately and analysed in a way that takes account of costs, benefits and any potential negative consequences. This can sometimes be referred to as a value and opportunities register.”

3. Benefit–Risk Assessment

3.1. Establishing the Context

3.2. Identification of User

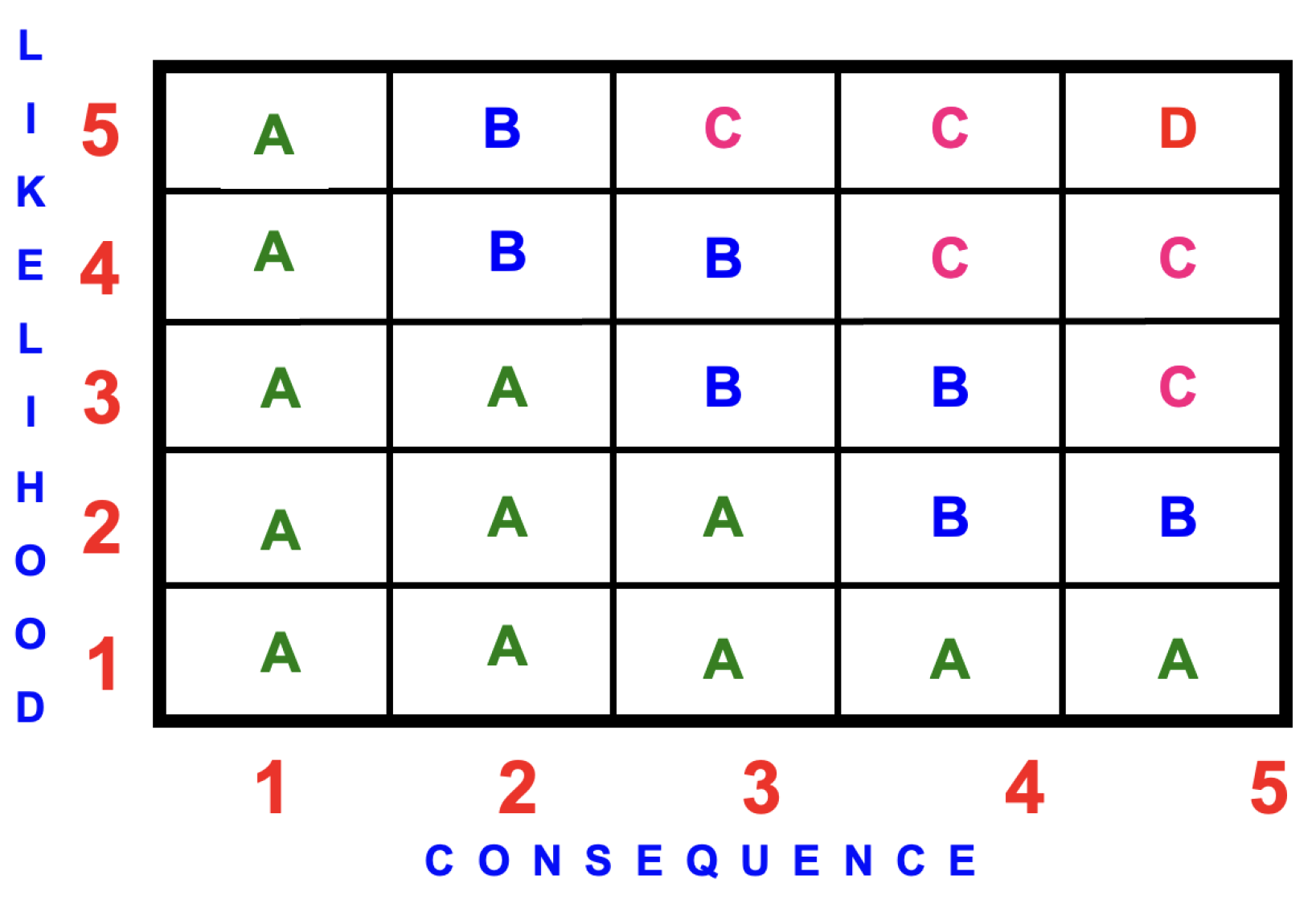

3.3. Risk Assessment

- 1 = Rare (highly unlikely event);

- 2 = Unlikely (conceivable event);

- 3 = Possible (could occur event);

- 4 = Likely (almost certain event);

- 5 = Certain (will occur event).

- 1 = Little or no injury;

- 2 = Minor injury requiring first aid;

- 3 = Moderate injury requiring medical assessment;

- 4 = Serious injury with long-term consequences;

- 5 = Death or major disability.

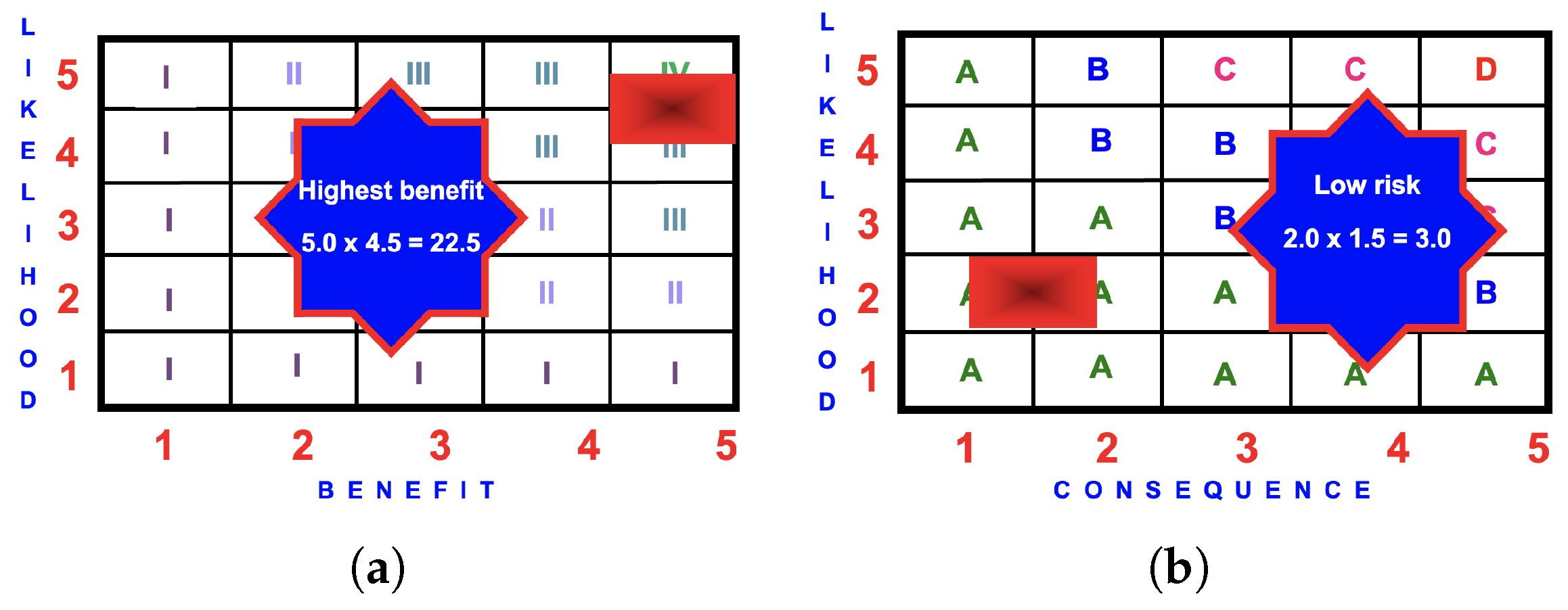

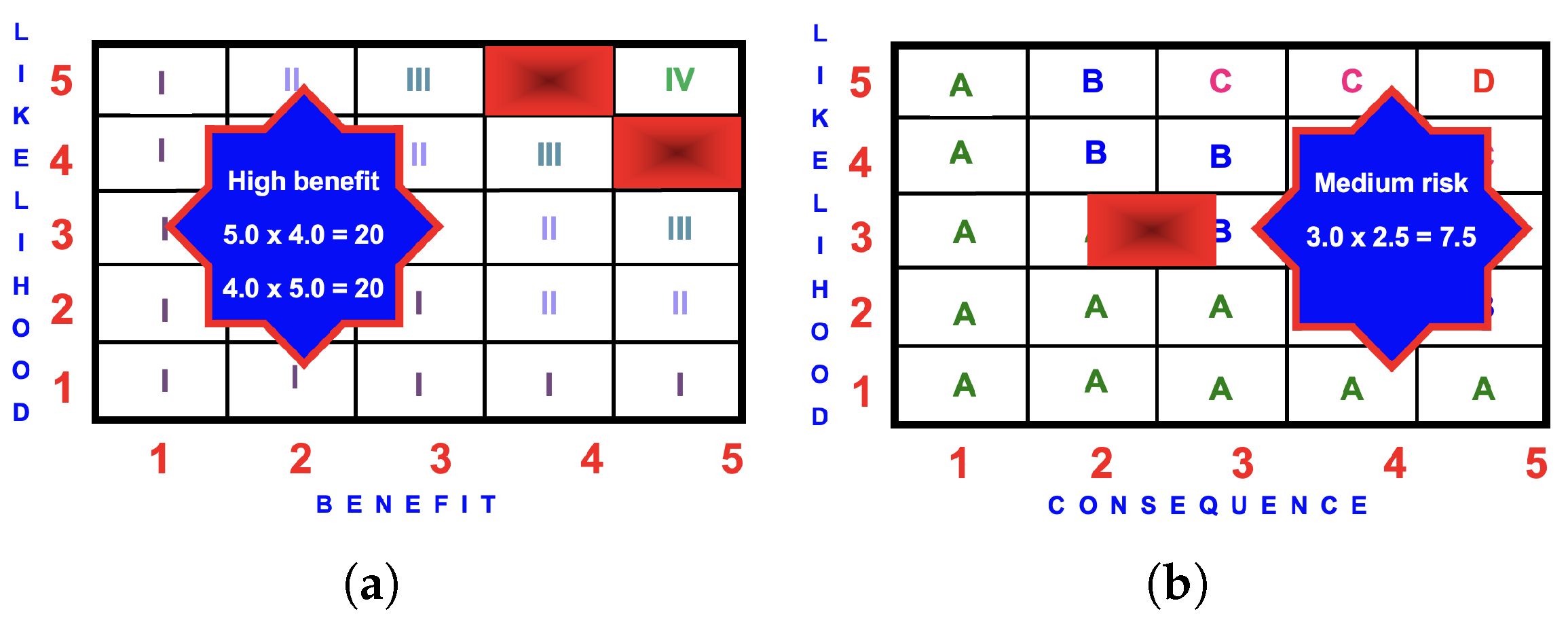

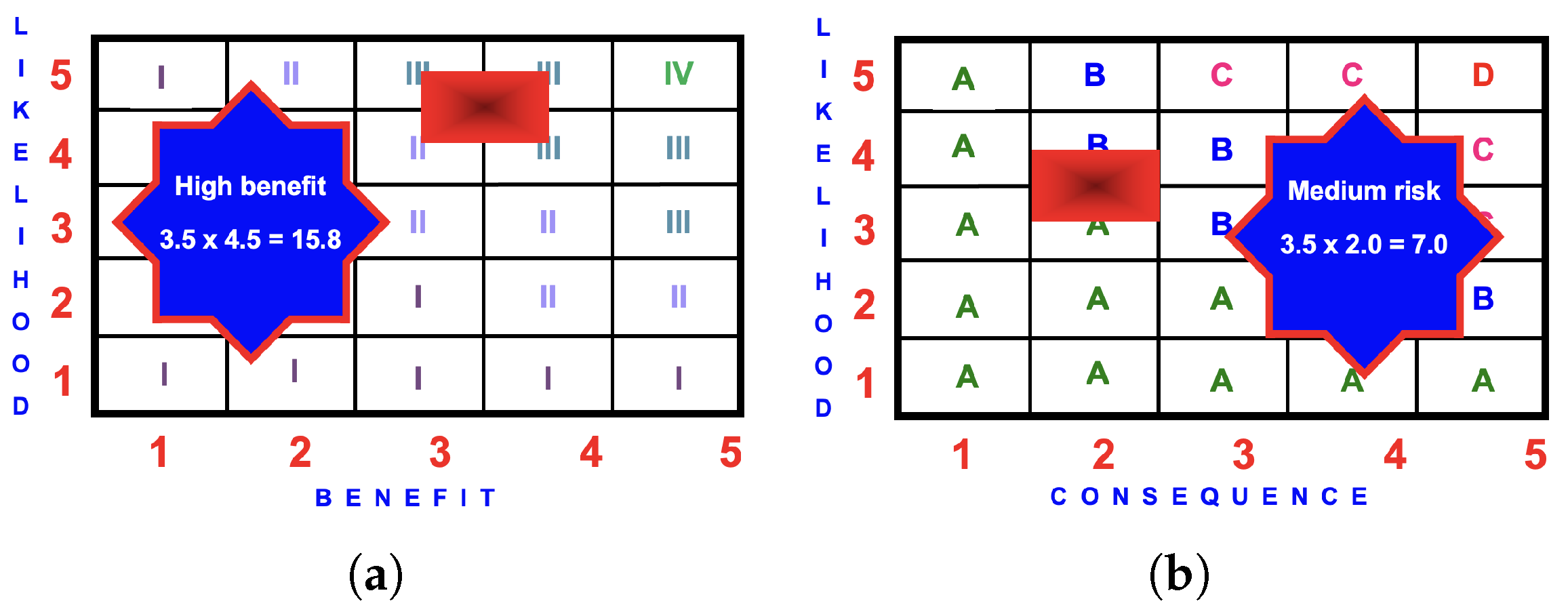

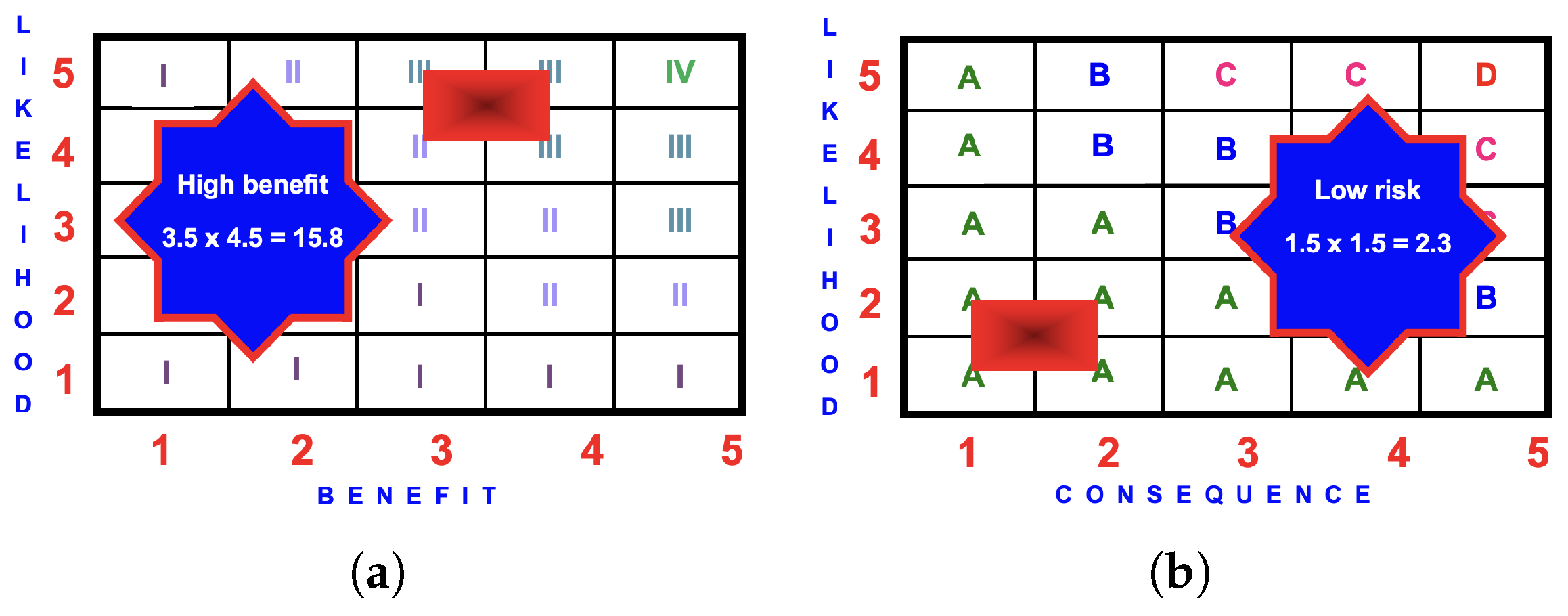

- (A)

- Low risk to 7;

- (B)

- Medium risk to 12;

- (C)

- High risk to 20;

- (D)

- Highest risk .

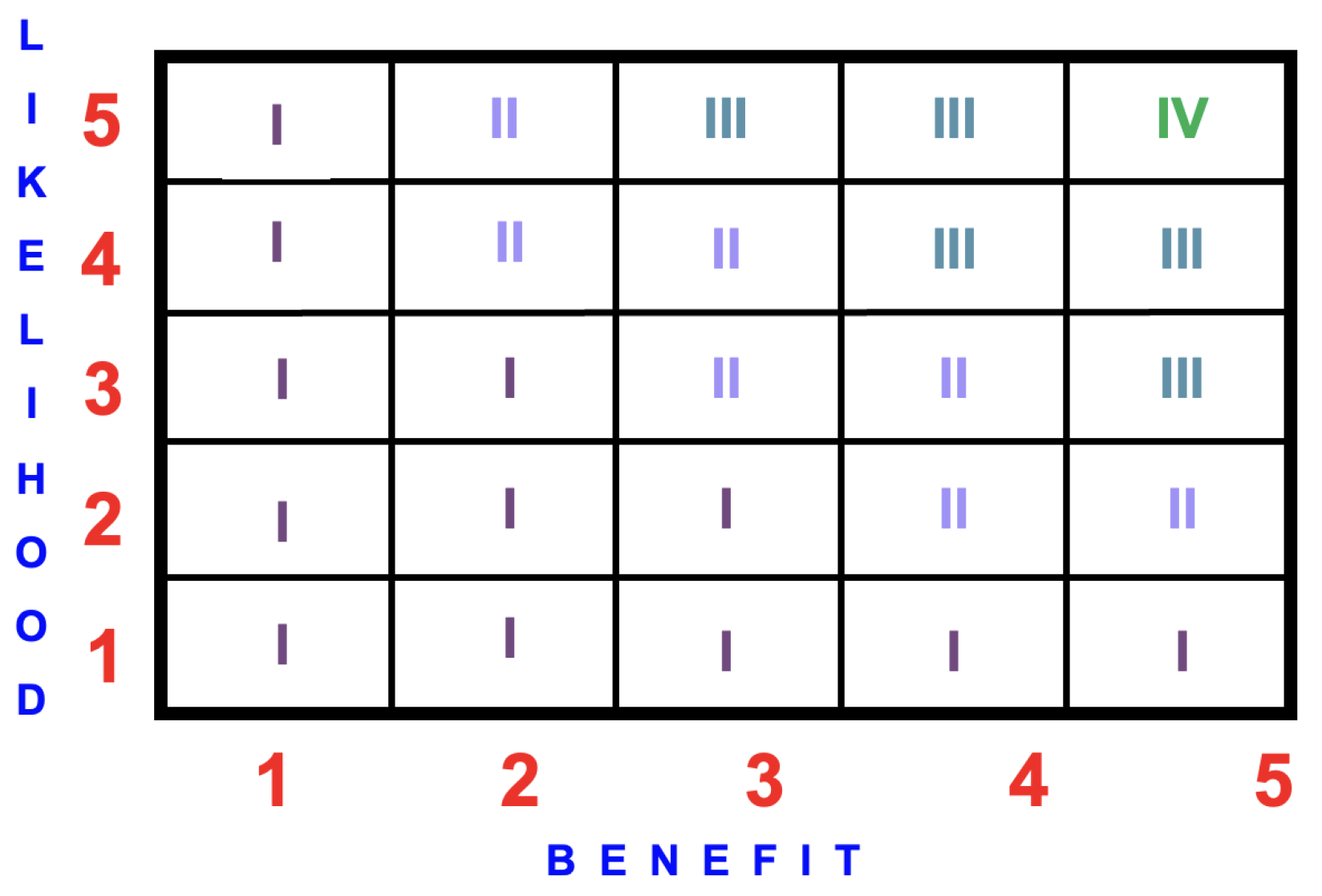

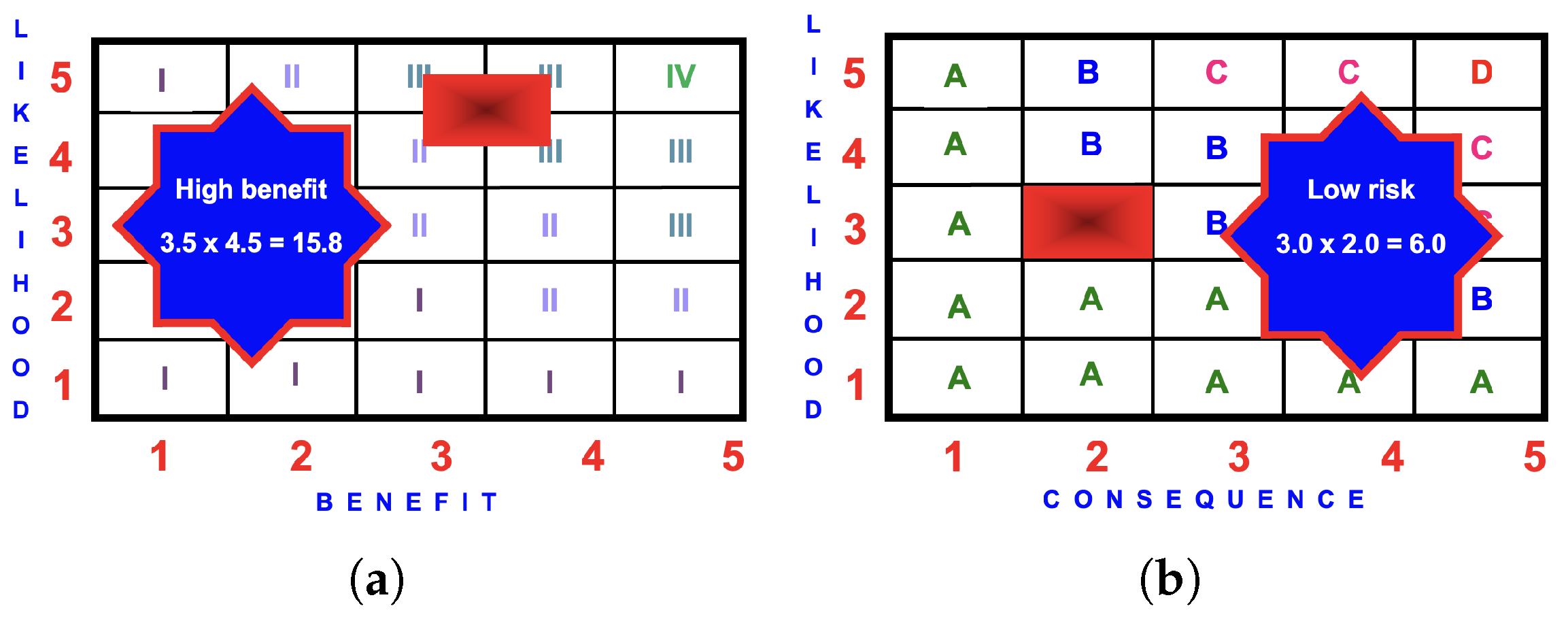

3.4. Benefit Assessment

- 1 = Rare (highly unlikely event);

- 2 = Unlikely (conceivable event);

- 3 = Possible (could occur event);

- 4 = Likely (almost certain event);

- 5 = Certain (will occur event).

- 1 = A momentary benefit such as joy in the activity.

- 2 = Short-term benefit such as having learned a new skill or learning skills faster and meeting and making new acquaintances.

- 3 = Medium-term benefit such as gaining proficiency that opens new opportunities and beginnings of a benefit feedback loop.

- 4 = Permanent life-style improvements that lead to better physical, social, and mental health have influence on future engagements and activities that are a further benefit to the user and are likely to contribute to the permanence of the benefit-feedback loop. This can also encourage and reinforce the user’s engagement in greater challenges.

- 5 = Benefits that go beyond the individual to engage others and potentially benefit society include reduction in suicide rates because of reduction of depression, resulting in, e.g., lower health care costs.

- (I)

- Low benefit =1 to 7;

- (II)

- Medium benefit >7 to 12;

- (III)

- High benefit >12 to 20;

- (IV)

- Highest benefit >20.

4. Discussion

“Opportunities to engage in outdoor free play- and risky play in particular-have declined significantly in recent years, in part because safety measures have sought to prevent all play-related injuries rather than focusing on serious and fatal injuries. Risky play is defined by thrilling and exciting forms of free play that involve uncertainty of outcome and a possibility of physical injury. Proponents of risky play differentiate ‘risk’ from ‘hazard’ and seek to reframe perceived risk as an opportunity for situational evaluation and personal development. This statement weighs the burden of play-related injuries alongside the evidence in favour of risky play, including its benefits, risks, and nuances, which can vary depending on a child’s developmental stage, ability, and social and medical context. Approaches are offered to promote open, constructive discussions with families and organisations. Paediatricians are encouraged to think of outdoor risky play as one way to help prevent and manage common health problems such as obesity, anxiety, and behavioural issues.”

- Rough and tumble play in a supervised early childhood setting;

- Children participating in a nature play activity;

- A child using a swing in an outdoor playground or school setting;

- A child riding a flying fox in an outdoor playground;

- A child on a rocking device in an outdoor playground (spring animal);

- A group of children climbing up and playing on a 10 m high 3D spatial net;

- Giant tube slide being used inappropriately and appropriately;

- Broken glass bottle in the playground or school setting.

- The authors’ combined lived experience as life-long educators of children and adolescents;

- Educators and assessors of outdoor playgrounds and supervised early childhood settings;

- Inspectors and maintenance staff of outdoor playgrounds and supervised early childhood settings;

- Landscape architects and engineers in the field;

- Experts on Australian and International Standards technical committees.

4.1. Rough and Tumble Play in a Supervised Early Childhood Setting (R&T)

- Problem solving, cooperation, turn-taking, negotiation, and conflict resolution;

- Imagination and perspective-taking through role play;

- Communication skills;

- Physical skills including fine and gross motor skills, balance, agility, coordination, and strength;

- Moderate to vigorous physical activity, endurance, and fitness, associated with reduced obesity;

- Self-awareness, emotion regulation, compassion, empathy, and respect for others;

- Self-confidence, sense of belonging, and friendship formation.

4.1.1. Risk Matrix

4.1.2. Benefit Matrix

- Scenario 1A momentary benefit such as the elation or joy in the activity.The likelihood of this benefit occurring is ‘certain’.

- Scenario 2Short-term benefit such as having acquired a new skill or learning skills faster and building stronger friendships.The likelihood of this benefit occurring is ‘certain’.

- Scenario 3Medium-term benefit relates to the beginnings of a benefit feedback loop resulting from children learning self-control, boundaries, and understanding of their own and others’ abilities and feelings.The likelihood of this benefit occurring is ‘likely’.

- Scenario 4Lifelong benefits which lead to enhancing physical, social, and mental health and well-being outcomes inevitably have a positive influence on children’s further engagement in R&T play. Positive feedback children receive from play partners reinforces the benefits resulting in likely permanence within the benefit feedback loop. Engagement in R&T play intrinsically encourages children to seek this form of play in other contexts and other social groups.

- Scenario 5Benefits that go beyond the individual to engage more broadly with others to potentially benefit society, include such factors as increasing prosocial behaviour and reducing mental health issues, with the results cascading into lower health care costs.

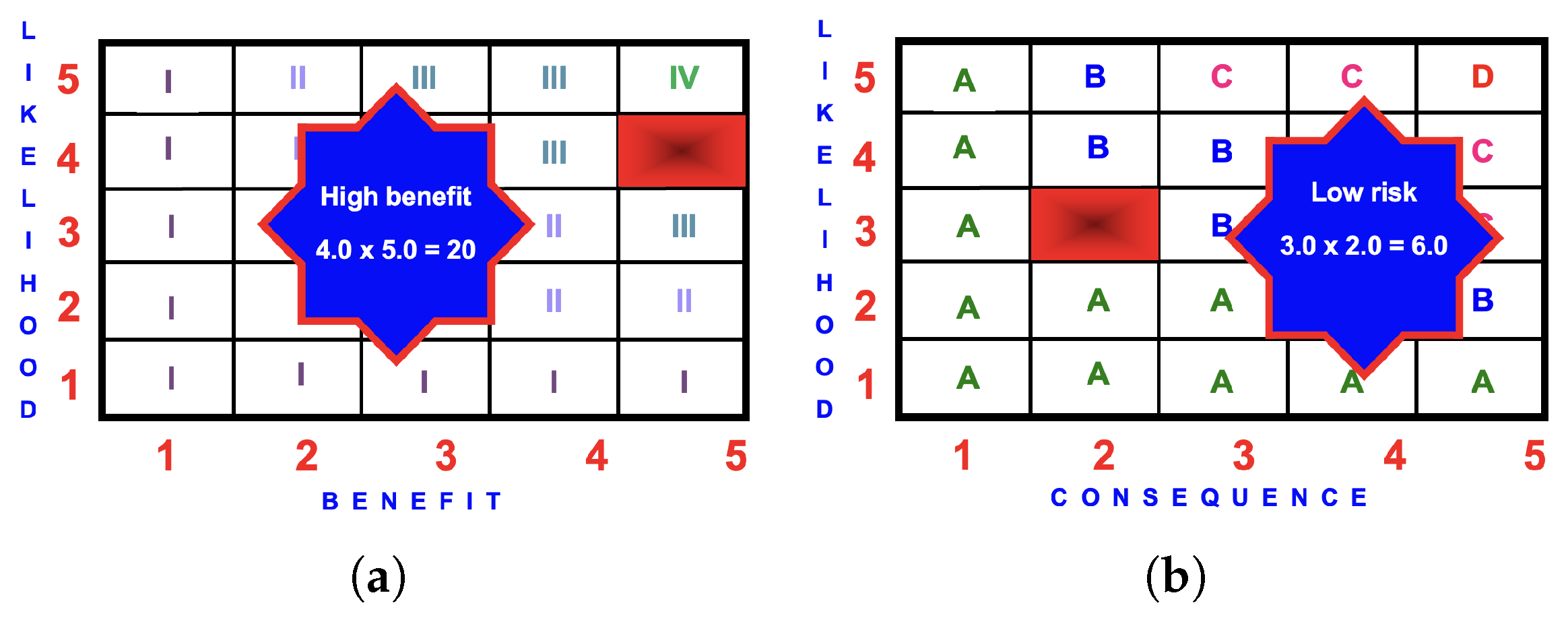

4.1.3. BRA Evaluation

4.2. Children Participating in a Nature Play Activity (NPA)

- Creativity and problem solving;

- Coordination;

- Proprioception;

- Balance and agility;

- Gross motor skill development;

- Physical activity;

- Confidence building;

- Environment stewardship.

4.2.1. Risk Matrix

4.2.2. Benefit Matrix

4.2.3. BRA Evaluation

4.3. Child Using a Swing in an Outdoor Playground (SiOP)

- Skill mastery;

- Reflection time;

- Coordination;

- Balance and vestibular stimulation;

- Swinging motion;

- Upper body and core strength;

- Exercise and lowering obesity levels;

- Sharing.

4.3.1. Risk Matrix

4.3.2. Benefit Matrix

- Scenario 1A momentary benefit, such as joy and exhilaration emanating from the activity. The likelihood of this benefit occurring is ‘almost certain’.

- Scenario 2Short-term benefit, such as having learned a new skill or learning skills faster. The likelihood of this benefit occurring is ‘certain’.

- Scenario 3Medium-term benefit, such as gaining proficiency that opens new opportunities and beginnings of a benefit feedback loop. The likelihood of this benefit occurring is ‘certain’.

- Scenario 4Permanent or lifelong lifestyle improvements are a necessary precursor to improved physical, social, and mental health and well-being outcomes. It can also have a positive influence on future engagement levels that cascade into further benefits for the end-user and the likely permanence of the benefit feedback loop. This can also encourage and reinforce the user’s engagement in greater challenges. The likelihood of this benefit occurring is ‘certain’.

- Scenario 5Benefits that go beyond the individual to engage others and potentially benefit society, such as a reduction in suicide rates because of the lowering of depression, and the ripple effect results, e.g., lowering health care costs. The likelihood of this benefit occurring is ‘likely’.

4.3.3. BRA Evaluation

4.4. A Child Riding a Flying Fox in an Outdoor Playground (FFiOP)

- Skill mastery;

- Upper body strength (for hanging flying fox);

- Exercise (dragging fox to dispatch);

- Excitement and fear (acceleration and deceleration forces);

- Gliding motion;

- Sharing.

4.4.1. Risk Matrix

4.4.2. Benefit Matrix

4.4.3. BRA Evaluation

4.5. A Child on a Rocking Device in an Outdoor Playground (RDiOP)

- Skill mastery;

- Coordination;

- Balance;

- Rocking motion and the development of their vestibular system;

- Upper body and core strength;

- Exercise and physical exertion;

- Sharing and taking turns;

- Gross motor skill development.

4.5.1. Risk Matrix

4.5.2. Benefit Matrix

4.5.3. BRA Evaluation

4.6. A Group of Children Climbing up and Playing on a 10 m High 3D Spatial Net (3DSN)

- Skill mastery;

- Coordination;

- Climbing skills;

- Balance and agility;

- Upper body strength;

- Exercise and physical activity;

- Reduced fear of heights;

- Building confidence and independence;

- Gross motor skill development.

4.6.1. Risk Matrix

4.6.2. Benefit Matrix

4.6.3. BRA Evaluation

4.7. Giant Tube Slide Being Used Inappropriately and Appropriately

- Skill mastery;

- Coordination;

- Exercise (climbing to the start);

- Builds confidence and independence;

- Fosters risk tolerance;

- Gross motor skill development.

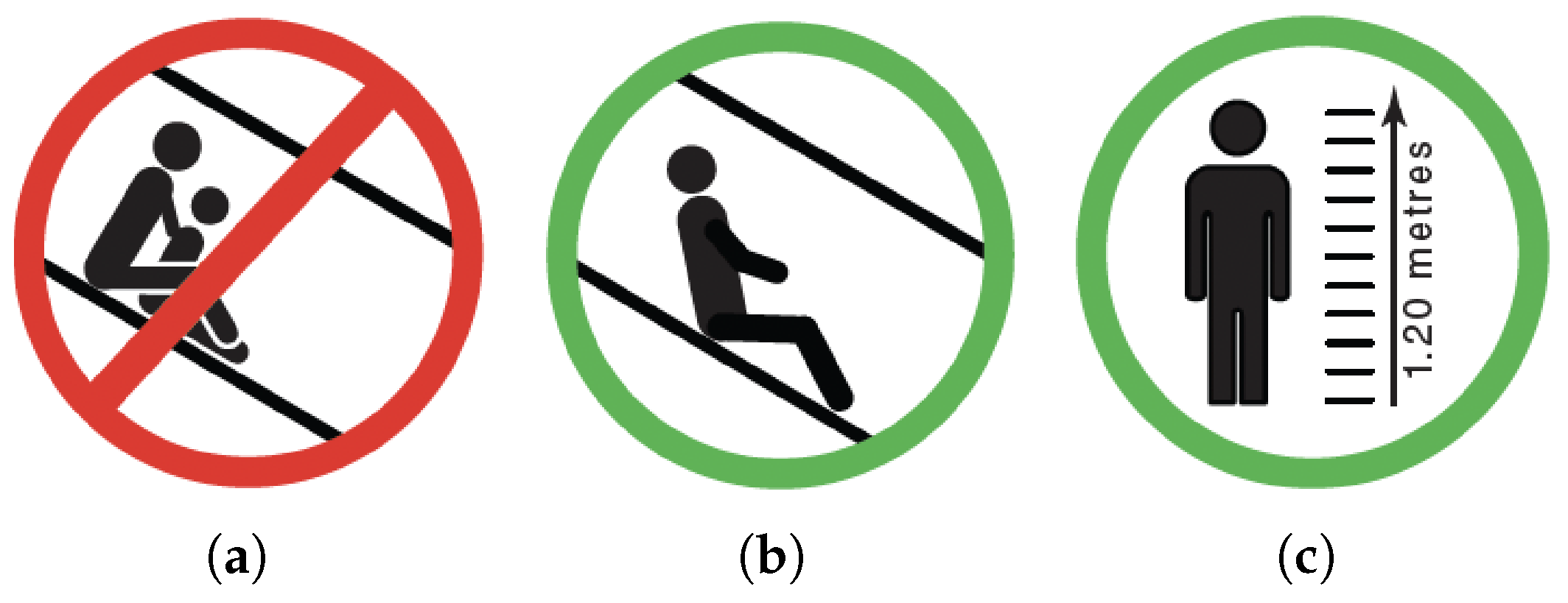

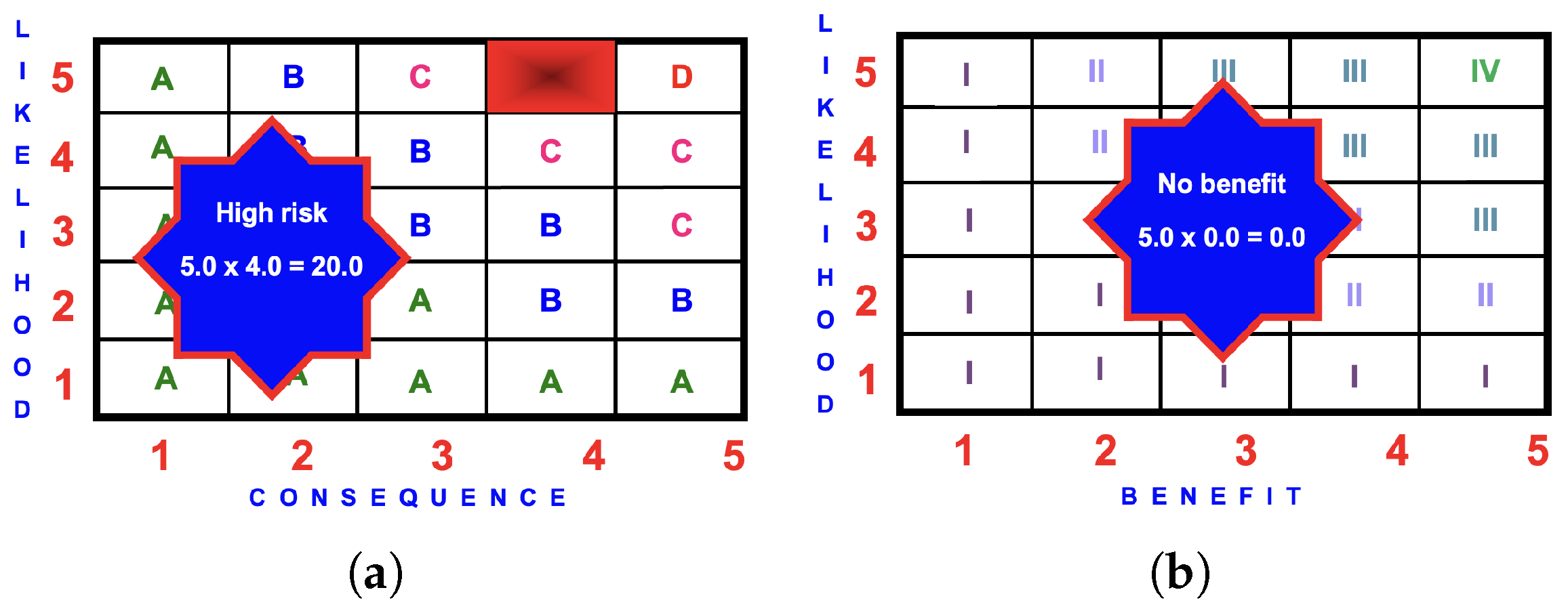

4.7.1. Inappropriate and Hazardous Use of a Giant Tube Slide (GTSi)

- The parent who has less control (as they are holding their child between their legs) panics when their velocity increases above their perceived ‘safe’ threshold. The adult attempts to slow down and in so doing loses control and suffers a serious injury, such as a broken ankle, tibia, or femur.

- The small child or inexperienced rider uses the slide. In a similar manner to the parent and child, their velocity increases above their perceived ‘safe’ threshold. The child attempts to slow down and in so doing suffers a similar fate to the adult travelling in tandem with a child between their legs.

4.7.2. Risk Matrix

4.7.3. Benefit Matrix

4.7.4. BRA Evaluation

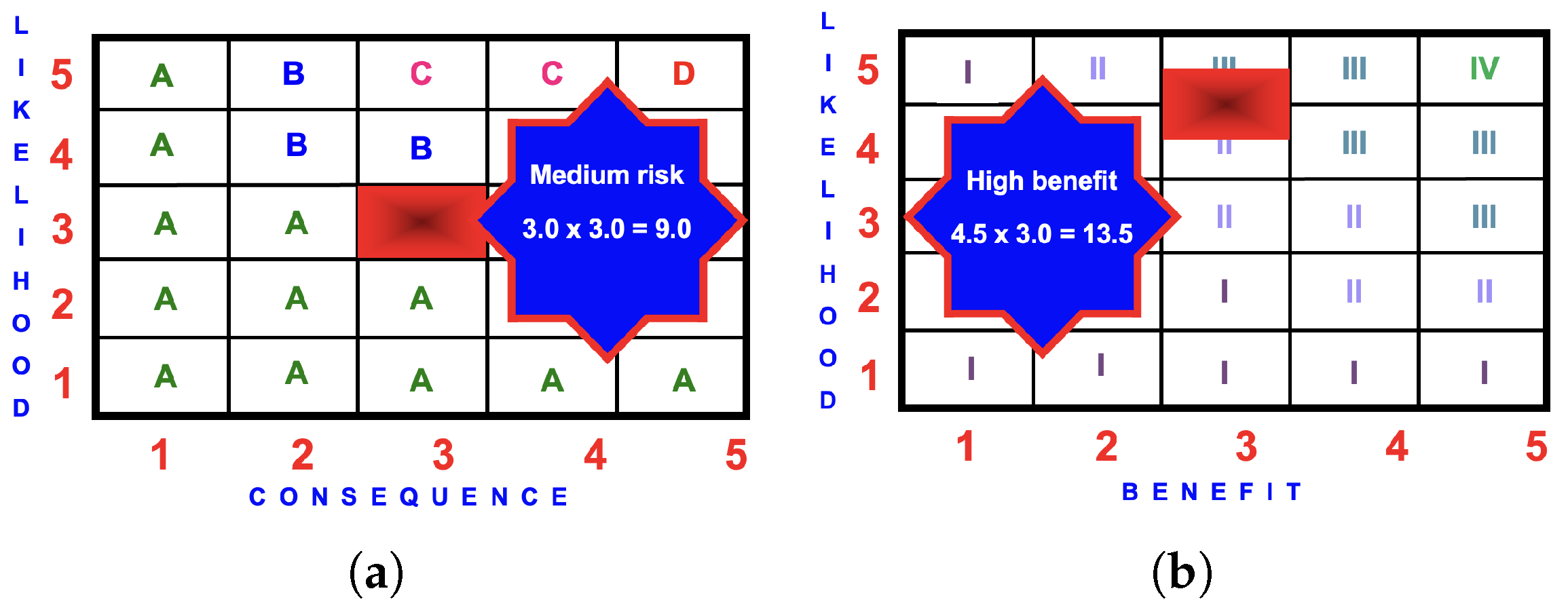

4.7.5. Appropriate and Beneficial Use of a Giant Tube Slide (GTSa)

- Centreline radius of all slide elbows to be greater than 1.2 m;

- Ability filters to limit access to the starting section of the slide;

- Anticlimb barriers to deter climbing on the external parts of the slide.

- Advice against tandem riding;

- Instructions to slide feet first only;

- Warn against slowing or stopping inside the slide;

- All users to be 1.2 m or taller.

4.7.6. Risk Matrix

4.7.7. Benefit Matrix

4.7.8. BRA Evaluation

4.8. Broken Glass Bottle in the Outdoor Playground or School Setting (BGB)

4.8.1. Risk Matrix

4.8.2. BRA Evaluation

4.9. Comparison of the Examples

4.10. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| AS 4685.0:2017 | AS 4685.0:2017 Playground equipment and surfacing Part 0: |

| Development, installation, inspection, maintenance and operation | |

| AS 4685.1:2004 | AS 4685.1:2004 Playground equipment and surfacing Part 1: |

| General safety requirements and test methods | |

| BRA | Benefit–risk analysis |

| IEC 31010:2019 | IEC 31010:2019 Risk management – Risk assessment techniques |

| ISO 4980:2023 | ISO 4980:2023 Benefit–risk assessment for sport and recreational |

| facilities, activities and equipment | |

| EN 1176-1:2008 | EN 1176-1:2008 Playground equipment and surfacing Part 1: |

| General safety requirements and test methods | |

| EN 1176-2:2017 | EN 1176-2:2017 Playground equipment and surfacing Part 2: |

| Specific safety requirements and test methods for swings | |

| Play Safety Forum | Play Safety Forum, Managing risk in play provision: A position statement |

| SA HB 244:2025 | SA HB 244:2025 Supplementary guide to AS 4685.3:2021 – Giant tube slides |

References

- ISO 4980:2023; Benefit-Risk Assessment for Sports and Recreational Facilities, Activities and Equipment. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Little, H. Risky play in early childhood education. In Oxford Bibliographies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, T.; Sturges, M.; Barnes, J. Risk and Outdoor Play: Listening and Responding to International Voices Part 1; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlberg, P.; Doyle, W. Let the Children Play: How More Play Will Save Our Schools and Help Children Thrive; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Dodd, H.; Lester, K. Adventurous play as a mechanism for reducing risk for childhood anxiety: A conceptual model. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 24, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogman, M.; Garner, A.; Hutchinson, J.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkoff, R. The power of play: A pediatric role in enhancing development in young children. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20182058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alla, K.; Truong, M. Nature Play and Child Wellbeing. In Australian Institute of Family Studies; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2024. Available online: https://aifs.gov.au/resources/policy-and-practice-papers/nature-play-and-child-wellbeing (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Brussoni, M.; Olsen, L.; Pike, I.; Sleet, D. Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child developments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3134–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, T.; Gray, T. Risk Management in the Outdoors: A Whole of Organisation Approach for Education, Sport and Recreation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Little, H. Risk-taking in outdoor play. In Outdoor Learning Environments, Spaces for Exploration, Discovery and Risk-Taking in the Early Years; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, M.; Gray, T.; Barnes, J.; Lloyd, A. Parents’ and caregivers’ perspectives on the benefits of a high-risk outdoor play space. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2023, 26, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.; Little, H.; Ball, D.; Eager, D.; Brussoni, M.; Waller, T.; Ärlemalm-Hagsér, E.; Lee-Hammond, L.; Lekies, K.; Wyver, S. Risk and safety in outdoor play. In The SAGE Handbook of Outdoor Play and Learning; SAGE Publications Ltd: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zeni, M.; Schnellert, L.; Brussoni, M. We do it anyway: Professional identities of teachers who enact risky play as a framework for Education Outdoors. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2023, 26, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, E.; Beno, S. Healthy childhood development through outdoor risky play: Navigating the balance with injury prevention. Paediatr. Child Health 2024, 29, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D. Playgrounds–Risks, Benefits and Choices; Middlesex University: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, A. Physical risk-taking: Dangerous or endangered? Early Years 2003, 23, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.; Cavanagh, M.; Eager, D. Not all risk is bad, playgrounds as a learning environment for children. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2006, 13, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T. No Fear: Growing Up in a Risk Adverse Society; Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sandseter, E. Categorising risky play–how can we identify risk-taking in children’s play? Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 15, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovey, H. Playing Outdoors: Spaces and Places, Risk and Challenge; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Little, H.; Wyver, S. Outdoor play: Does avoiding the risks reduce the benefits? Aust. J. Early Child. 2008, 33, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eager, D. Why Children Need Risk. In Proceedings of the Pediatric Trauma Seminar, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick, Australia, 6 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gleave, J. Risk and Play: A Literature Review; National Children’s Bureau: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Little, H.; Eager, D. Risk, challenge and safety: Implications for play quality and playground design. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.; Ball-King, L. Safety Management and Public Spaces: Restoring Balance. Risk Anal. 2012, 33, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brussoni, M.; Brunelle, S.; Pike, I.; Sandseter, E.; Herrington, S.; Turner, H.; Belair, S.; Logan, L.; Fuselli, P.; Ball, D. Can child injury prevention include healthy risk promotion. Inj. Prev. 2014, 21, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risk-Benefit Assessment Form—A Worked Example; Play Safety Forum: London, UK, 2014.

- Brussoni, M.; Gibbons, R.; Gray, C.; Ishikawa, T.; Sandseter, E.; Bienenstock, A.; Chabot, G.; Fuselli, P.; Herrington, S.; Janssen, I.; et al. What is the relationship between risky outdoor play and health in children? A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6423–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.; Ball-King, L. Risk and the Perception of Risk in Interactions with Nature; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.; Ball-King, L. Health, the Outdoors and Safety. Sustainablity 2021, 13, 4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball-King, L. Benefit-risk assessment: Balancing the benefits and risks of leisure. World Leis. J. 2022, 64, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, H. It is about Taking the Risk: Exploring Toddlers’ Risky Play in a Redesigned Outdoor Space. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.; Kleppe, R.; Kennair, L. Risky play in children’s emotion regulation, social functioning, and physical health: An evolutionary approach. Int. J. Play. 2023, 12, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvalnes, Ø.; Sandseter, E. Risky Play—An Ethical Challenge; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsanger, L.; Sandseter, E. Risk and Safety Management in Physical Education: Teachers’ Perceptions. Educ. Sci. 2023, 11, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eager, D. Benefit–Risk Assessment in Sport and Recreation: Historical Development and Review of AS ISO 4980: 2023. Standards 2024, 4, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.; Gray, T.; Truong, S.; Passy, R.; Ho, S.; Ward, K.; Sahlberg, P.; Bentsen, P.; Curry, C.; Cowper, R.A. Getting out of the classroom and into nature: A systematic review of nature-specific outdoor learning on school children’s learning and development. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, T.; Ärlemalm Hagsér, E.; Sandseter, E.; Lee-Hammond, L.; Lekies, K.; Wyver, S. The SAGE Handbook of Outdoor Play and Learning; SAGE: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heseltine, P. A playground safety campaign. In Proceedings of the Playground Safety International Conference, University Park, PA, USA, 9–12 October 1995; ISBN 0 9650342 0 8. [Google Scholar]

- Managing Risk in Play Provision: A Position Statement; Play Safety Forum: London, UK, 2002.

- AS 4685.1:2004; Playground Equipment and Surfacing Part 1: General Safety Requirements and Test Methods. Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2004.

- EN 1176-1:2008; Playground Equipment and Surfacing Part 1: General Safety Requirements and Test Methods. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2008.

- AS 4685.0:2017; Playground Equipment and Surfacing Part 0: Development, Installation, Inspection, Maintenance and Operation. Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2017.

- IEC 31010:2019; Risk Management–Risk Assessment Techniques. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Gray, P. Risky play: Why children love and need it. In Handbook of Designing Public Spaces for Young People; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sando, O.; Kleppe, R.; Sandseter, E. Risky play and children’s well-being, involvement and physical activity. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 1435–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankiw, K.; Tsiros, M.; Baldock, K.; Kumar, S. The impacts of unstructured nature play on health in early childhood development: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, J.L.; Tannock, M.T. Playful Aggression in Early Childhood Settings. Child. Aust. 2013, 38, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.D. Rough-and-Tumble Play: Developmental and Educational Significance. Educ. Psychol. 1987, 22, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, T.; Brown, M. The expression of care in the rough and tumble boy of boys. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2000, 15, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Nagel, M. Including playful aggression in early childhood curriculum and pedagogy. Australas. J. Early Child. 2017, 42, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1176-2:2017; Playground Equipment and Surfacing Part 2: Additional Safety Requirements and Test Methods for Swings. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- Seven Reasons New Workers Are MORE likely to Get Injured, Canadian Occupational Safety. Available online: https://www.thesafetymag.com/ca/topics/safety-and-ppe/seven-reasons-new-workers-are-more-likely-to-get-injured/422474 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- EN 1176-4:2017; Playground Equipment and Surfacing Part 4: Additional Specific Safety Requirements and Test Methods for Cableways. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- EN 1176-7:2017; Playground Equipment and Surfacing Part 7: Requirements for Installation, Insection, Maintenance and Operation of Playground Equipment. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- EN 1176-3:2017; Playground Equipment and Surfacing Part 3: Additional Safety Requirements and Test Methods for Slides. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- SA HB 244:2025; Supplementary Guide to AS 4685.3:2021—Giant Tube Slides. Standards Australia: Sydney, Australia, 2025.

- Kane, M. Validating score interpretations and uses. Lang. Test. 2012, 29, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.; Kvern, B. Using Kane’s framework to build a validity argument supporting (or not) virtual OSCEs. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Benefit | Benefit | Benefit | Risk | Risk | Risk | BRA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Like’d | Conseq. | Score | Like’d | Conseq. | Score | B > R | |

| R&T | 5.0 | 4.0 | III (20.0) | 3.0 | 2.0 | A (6.0) | Yes |

| NPA | 5.0 | 4.5 | IV (22.5) | 2.0 | 1.5 | A (3.0) | Yes |

| SiOP | 5.0 | 4.0 | III (20.0) | 3.0 | 2.5 | B (7.5) | Yes |

| FFiOP | 3.5 | 4.5 | III (15.8) | 3.5 | 2.0 | A (7.0) | Yes |

| RDiOP | 3.5 | 4.5 | III (15.8) | 1.5 | 1.5 | A (2.3) | Yes |

| 3DSN | 3.5 | 4.5 | III (15.8) | 3.0 | 2.0 | A (6.0) | Yes |

| GTSi | – | – | – (0.0) | 5.0 | 4.0 | C (20.0) | No |

| GTSa | 4.5 | 3.0 | III (13.5) | 3.0 | 3.0 | A (3.0) | Yes |

| BGB | – | – | – (0.0) | 5.0 | 3.5 | C (17.5) | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eager, D.; Gray, T.; Little, H.; Robbé, F.; Sharwood, L.N. Risky Play Is Not a Dirty Word: A Tool to Measure Benefit–Risk in Outdoor Playgrounds and Educational Settings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060940

Eager D, Gray T, Little H, Robbé F, Sharwood LN. Risky Play Is Not a Dirty Word: A Tool to Measure Benefit–Risk in Outdoor Playgrounds and Educational Settings. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):940. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060940

Chicago/Turabian StyleEager, David, Tonia Gray, Helen Little, Fiona Robbé, and Lisa N. Sharwood. 2025. "Risky Play Is Not a Dirty Word: A Tool to Measure Benefit–Risk in Outdoor Playgrounds and Educational Settings" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060940

APA StyleEager, D., Gray, T., Little, H., Robbé, F., & Sharwood, L. N. (2025). Risky Play Is Not a Dirty Word: A Tool to Measure Benefit–Risk in Outdoor Playgrounds and Educational Settings. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060940