Abstract

Objective: This study aims to examine the relationship between atopic dermatitis (AD), one of the most common dermatological conditions in children, and environmental factors, including meteorological variables and air pollution. Methods: This retrospective cross-sectional study analyzed the medical records of 21,407 pediatric patients aged 0 to 18 years who presented to the city hospital in Agri, Turkey, between 2020 and 2024. Admission dates were matched with meteorological data (wind speed, atmospheric pressure, humidity, temperature) and air pollution indicators (PM10, SO2, NO2, NOx, NO, O3). Statistical analyses included t-tests, correlation analyses, binary logistic regression, and a CHAID decision tree model. Results: AD accounted for 10.1% of all dermatology-related visits. AD admissions increased particularly during the first half of the year and were significantly associated with higher O3 levels, whereas increased PM10 levels were associated with a lower likelihood of AD admissions. Logistic regression showed that age, sex, semiannual period, atmospheric pressure, PM10, and O3 were significant predictors of AD. The decision tree model identified age, period, and O3 as the strongest discriminating variables for AD. Conclusion: AD was found to be more sensitive to environmental and seasonal variations compared with other dermatitis types. In particular, elevated ozone levels and temporal factors played a notable role in increasing AD presentations. These findings may inform environmental risk management and preventive strategies for children with AD.

1. Main Message

Atopic dermatitis in children is more sensitive to environmental changes than other dermatitis types, showing a clear increase with rising ozone levels and distinct seasonal variability.

2. Background

Air pollution is a complex mixture of certain solid particles, liquid droplets and gas molecules [1]. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identifies major air pollutants, including ozone (O3), particulate matter (PM), carbon monoxide (CO), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), all of which have well-established negative effects on human health [2]. The concentration of these air pollutants has increased significantly in some regions around the world due to sociocultural trends such as increased forest fires, urbanization and industrialization [3]. Today, 91% of the global population lives in areas where air pollution levels exceed the safe exposure limits defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) [4]. Exposure to air pollution can adversely affect human health and increase the risk of AD, a common skin condition known for its sensitivity to environmental triggers, or exacerbate existing symptoms [5,6,7].

AD has become one of the most common inflammatory skin disorders worldwide, and environmental triggers are believed to play a significant role in its development [5,8]. AD, also known as eczema, is a common skin disease that affects 20% of children and 5% of adults globally [9]. This chronic or recurrent inflammatory condition is characterized by sudden flare-ups of eczematous and itchy lesions on dry skin [10,11,12,13]. Recurrent eczema lesions and intense itching can lead to significant impairment of quality of life [14].

Although air pollutants such as NO2, SO2, NOx, O3, and PM10 have been reported to be associated with AD prevalence and symptoms, it is noted that these effects may be influenced by confounding factors such as age, gender, geographical location, and economic conditions [15]. Furthermore, it is reported that most of these pollutants are highly correlated with each other [16]. At the cellular level, particulate matter (PM) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) can induce oxidative stress, directly damaging protein and lipid structures in the skin and thereby disrupting the integrity of the skin barrier [17,18]. This oxidative damage leads to dysregulation in both innate and adaptive immune responses, increasing sensitivity to allergens and triggering a cycle in which inflammation and allergic sensitization are continuously sustained [19,20]. Additionally, interactions between environmental pollutants and the neuroimmune system have been shown to play a critical role in itch pathways specific to AD, further highlighting the complex biological relationship between external exposures and cutaneous responses [21,22].

In addition, meteorological conditions (such as humidity, temperature, and wind) also play an important role in increasing the frequency of AD and the severity of its symptoms [23]. Different climatic factors are known to affect the development of postnatal skin functional parameters [24]. Epidemiological studies suggest that common climatic variables are associated with childhood eczema prevalence [25,26,27]. Epidemiological research is important not only for determining the prevalence of diseases but also for planning preventive healthcare services. The exact determination of the frequency of skin diseases is only possible through extensive population studies [28].

This study was conducted to evaluate the most common AD among other types of dermatitis (DDT) and to compare it with DDT. Using patient data collected over a four-year period in eastern Turkey, the effects of air pollution and meteorological variables on these types of dermatitis were investigated in detail. This study, which uses a decision tree model (CHAID) to assess the impact of environmental factors on AD and DDT in a seasonal context, is one of the rare studies of its kind. This unique approach ensures that the findings make a significant contribution to the literature. Moreover, with the four-year dataset, the reliability of the findings is enhanced, and a more comprehensive exploration of the effects of environmental factors on DDT has been made possible. The findings of the study aim to indirectly contribute to the development of individualized care strategies and the improvement of environmental health policies.

3. Methods

This study is a retrospective research designed using data obtained from the registry system of a single-center city hospital. The data of children diagnosed with DDT and AD between August 2020 and July 2024 were analyzed in this study.

3.1. Study Population and Sample

The study population consisted of children aged 0–18 years who were diagnosed with DDT or AD. No sampling was performed, and data from all patients who presented with these diagnoses to a single-center city hospital between August 2020 and July 2024 were included in the study. This retrospective cross-sectional study analyzed a total of 21,407 patient records from individuals residing in Agri, one of the cities in eastern Turkey with the highest levels of air pollution, who presented to local healthcare facilities. Following the pandemic period, the systematic recording of hospital admissions enabled the construction of a dataset that covered the longest available timeframe including both meteorological variables and air pollution measurements. Within this dataset, atopic dermatitis emerged as the most frequently observed specific dermatitis subtype. Examination of all dermatitis diagnoses showed that many subtypes occurred at extremely low frequencies and did not constitute epidemiologically meaningful groups. In contrast, atopic dermatitis with 2151 cases corresponding to 10.1 percent was the only specific dermatitis diagnosis with a substantial prevalence. The remaining dermatitis categories were either broad and heterogeneous or had case numbers below one percent, making them unsuitable for separate analytical grouping. For this reason, patients were classified into two main diagnostic categories. The DDT group consisted of 19,256 cases representing 89.9 percent while the AD group included 2151 cases representing 10.1 percent of all dermatitis related visits. This classification approach was chosen to strengthen statistical power and to allow a more accurate evaluation of atopic dermatitis as the only subtype with a meaningful epidemiological burden.

The first category consisted of demographic variables. Patient information was obtained from electronic health records after the necessary permissions were granted by the Agri Provincial Health Directorate. The second category included meteorological parameters such as wind, pressure, humidity, and temperature, and these data were obtained from the Agri Provincial Directorate of Meteorology. The third category comprised air pollution variables including NO2, SO2, NOx, O3, and PM10, which were also provided by the Agri Provincial Directorate of Meteorology. All meteorological and air pollution variables were included in the analyses as continuous variables, and their monthly mean values were used. Demographic, meteorological, and air pollution data were obtained directly from the relevant institutions, and the study period was defined as August 2020 to July 2024. This timeframe was selected because it represented the most consistent and uninterrupted period during which both hospital records and meteorological and air pollution measurements were systematically available.

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Children and adolescents aged zero to eighteen years

- Individuals residing in the central district of Agri province

- Patients who presented to the Agri city hospital with dermatological complaints

- Records with complete and accurate information including age, sex, diagnosis code and date of admission

- Patients diagnosed with dermatitis belonging to the DDT or AD categories, selected because these were the only clinically meaningful and sufficiently frequent diagnostic groups in the dataset

3.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Patients who did not reside in the central district of Agri

- Records with missing, incomplete or incorrect information

- Visits made for reasons other than dermatological conditions

- Dermatitis diagnoses outside the DDT and AD categories, since these remaining ICD codes had very low frequencies or represented heterogeneous conditions unsuitable for analytical grouping

3.4. Data Collection Method

Patient data were retrospectively obtained from the electronic registry system of the city hospital. The data included information such as the patient’s age, gender, application date, and diagnosis type (DDT or AD). Meteorological data (temperature, humidity, pressure, wind speed) and air quality measurements (concentrations of PM10, NO2, SO2, etc.) were provided by national meteorological and environmental air quality monitoring systems. The meteorological and air quality data were matched with patient application dates, and the analyses were performed using monthly averages.

3.5. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses in this study were performed using the SPSS 26.0 software package, and the analytical process was designed with a multidimensional evaluation approach. In the first stage, the descriptive characteristics of the sample were summarized through frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations, and Pearson Chi Square tests were used to examine differences between categorical variables. Relationships between the independent variables and the binary dependent variable were examined using the Spearman correlation coefficient, and Cramer V effect size was calculated to support the interpretation of statistical significance given the large sample size. Independent sample t-tests were applied after confirming that meteorological and air pollution variables met the assumption of normal distribution.

In the second stage, a binary logistic regression model was constructed to identify factors predicting atopic dermatitis. All independent variables were entered simultaneously into the model using the enter method, and humidity and temperature variables were excluded due to high multicollinearity. The period variable was included as the only temporal predictor because it showed strong associations with season and month variables. Model assumptions were verified using the Box Tidwell test and VIF values, and potential outliers were assessed with Cook distance diagnostics. Model performance was evaluated using the Omnibus test, minus two Log Likelihood, Cox Snell and Nagelkerke R square values, and calibration was assessed with the Hosmer Lemeshow test. In the third stage, the CHAID decision tree model was applied to explore interactions between variables and to reveal hierarchical segmentation. Model generalizability was ensured through the use of Bonferroni corrected Chi Square splitting criteria and tenfold cross validation. All analyses were conducted with a ninety five percent confidence level, and statistical significance was accepted as p less than 0.05.

3.6. Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee for Non-Interventional Clinical Research of Van Yzüncü Yıl University on 18 September 2023 (decision number 2023/09-18). The data used in the study were anonymized, and the confidentiality of personal information was maintained.

4. Results

Of the 21,407 pediatric hospital records analyzed, 19,256 (90%) were diagnosed with dermatitis and 2151 (10%) with AD. Among girls, 91% were diagnosed with dermatitis and 8.6% with AD, whereas the corresponding rates for boys were 85.5% and 11.5%, respectively. Girls accounted for 50.8% of all dermatitis cases, while boys constituted 57.4% of all AD cases. A statistically significant yet small effect was observed between sex and diagnosis type (χ2 = 52.161, p < 0.001, V = 0.02), with a weak positive correlation (r = 0.049, p < 0.001).

The age of children with dermatitis ranged from 1 to 19 years (mean = 6.4 ± 5.6), while the age range for those with AD was 1 to 18 years (mean = 3.8 ± 4.5). Children with AD were significantly younger (t = 20.641, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.03). A weak and negative correlation was detected between age and diagnosis type (r = −0.159, p < 0.001), indicating that younger children were more likely to receive an AD diagnosis.

Across the four annual periods examined (August 2020–July 2024), total hospital visits increased steadily, with the August 2023–July 2024 period (n = 7552) showing nearly twice as many visits as the first period (n = 3763). Dermatitis consultations rose from 17.7% in the first period to 33.8% in the fourth. Nearly half of all AD visits (48.6%) occurred in the final period. Period and diagnosis type were significantly associated (χ2 = 211.284, p < 0.001, V = 0.03), and their correlation was weak and positive (r = 0.063, p < 0.001).

In the semiannual analysis, dermatitis rates were similar between the first and second six-month periods (49.7% vs. 50.3%). In contrast, AD was more common during the first six months (58.1%). The difference was statistically significant with a small effect size (χ2 = 211.284, p < 0.001, V = 0.02). A weak negative correlation was observed between semiannual period and diagnosis type (r = −0.051, p < 0.001).

Seasonal distribution of dermatitis was relatively stable (winter 25.9%, spring 24.6%, summer 25.3%, autumn 24.2%). Atopic dermatitis rates were highest in spring (29.7%) and lowest in autumn (19.3%). The association between season and diagnosis type was statistically significant with a small effect size (χ2 = 39.476, p < 0.001, V = 0.01), accompanied by a weak negative correlation (r = −0.027, p < 0.001).

In the monthly analysis, February and May showed higher proportions of AD, whereas August, September, November, and December exhibited higher proportions of dermatitis. Month and diagnosis type were significantly associated (χ2 = 75.638, p < 0.001), with a weak negative correlation (r = −0.043, p < 0.001). (Table 1).

Table 1.

Statistics on DDT and AD data and comparisons.

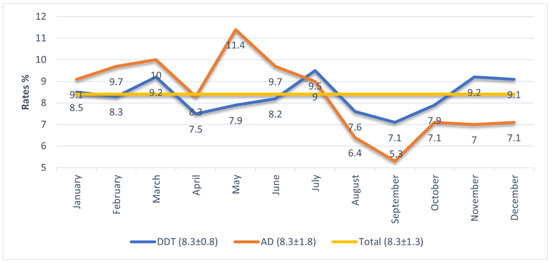

As shown in Figure 1, the mean monthly column percentages for dermatitis and AD were both 8.3% (dermatitis SD = 0.8; AD SD = 1.8; total SD = 1.3), indicating similar month-to-month distribution patterns.

Figure 1.

Proportional registration of hospital admissions diagnosed with DDT and AD by months.

It is observed that hospital admission rates for atopic diagnoses generally remain above both dermatitis diagnoses and overall mean admission rates; however, in July, the admission rate for atopic cases falls below that of dermatitis, and in August, September, November, and December, it declines further, remaining below both dermatitis and overall averages. Examination of the standard deviation values shows that while monthly dermatitis admissions have a standard deviation of 0.8, atopic admissions have a higher standard deviation of 1.8, indicating that atopic admissions fluctuate more across months. In the first six months (January–June), atopic admission rates are higher than dermatitis admissions, peaking in May (11.4%). The month of July represents a turning point where atopic admission rates begin to decline, reaching their lowest point in September (5.3%). (Figure 1).

- Wind Speed

A significant difference was observed between the groups in terms of mean wind speed (t = –2.279, p = 0.023). The average wind speed during periods with AD visits was higher (M = 14.6) compared to periods with dermatitis visits (M = 14.3). Wind speed showed a positive correlation with AD visit frequency (r = 0.028, p < 0.001).

In the first period (January–June), dermatitis visits were associated with higher wind speeds (M = 15.4 vs. M = 15.2; t = 2.155, p = 0.031). In the second period (July–December), wind speed was higher during AD visits (M = 13.7 vs. M = 13.4; t = –2.904, p = 0.004). Seasonally, wind speed was significantly higher during dermatitis visits in spring (t = 2.155, p < 0.05) and during AD visits in winter (t = –2.333, p < 0.05), while no differences were observed in summer or autumn (p > 0.05). Monthly analyses indicated higher wind speeds for dermatitis in March (t = 2.559), April (t = 2.991), and June (t = 2.274), whereas higher wind speeds for AD visits were found in September (t = –2.224), November (t = –4.099), and December (t = –3.266) (all p < 0.05).

- Atmospheric Pressure

Mean atmospheric pressure differed significantly between groups (t = 3.835, p < 0.001). The pressure on days with AD visits was lower (835.21) compared to days with dermatitis visits (835.41), and higher pressure was associated with fewer AD visits (r = –0.023, p < 0.001). In the first period, mean pressure was significantly higher during dermatitis visits (M = 836.3 vs. M = 835.1; t = 2.509, p = 0.011). Seasonal analysis showed a significant difference only in winter (t = 4.879, p < 0.05). Monthly comparisons revealed higher pressure during dermatitis visits in January (t = 3.313), February (t = 2.333), and March (t = 3.943) (all p < 0.05).

- Humidity

There was no overall significant difference in mean humidity between the groups (t = –1.823, p = 0.085), and no correlation was detected (r = 0.006, p > 0.05). However, in the first period, humidity was significantly higher during dermatitis visits (M = 66.5 vs. M = 65.6; t = 2.727, p = 0.006). Seasonal analysis indicated higher humidity for dermatitis in spring (t = 4.275, p < 0.05) and for AD visits in autumn (t = –2.787, p < 0.05).

Monthly analyses showed higher humidity for dermatitis in April (t = 6.678), while higher humidity for AD visits was observed in September (t = –2.645) and October (t = –4.069) (all p < 0.05).

- Temperature

No overall difference was found in mean temperature between the groups (t = 0.080, p = 0.936), and no correlation emerged (r = –0.001, p > 0.05). In the first period, temperature was significantly higher during AD visits (M = 5.6 vs. M = 4.9; t = –2.493, p = 0.001). Seasonally, a significant difference was observed only in spring, with higher temperatures during AD visits (t = –4.275, p < 0.05). Monthly analyses revealed higher temperatures for AD visits in March (t = –3.041), April (t = –6.594), May (t = –1.986), and June (t = –4.031), while higher temperatures for dermatitis visits were detected in September (t = 2.848) and October (t = 3.859) (all p < 0.05). (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of meteorological data by DDT and AD type.

- PM10

Mean PM10 levels differed significantly between the groups (t = 4.564, p < 0.001). PM10 was lower on days with AD visits (56.9 < 60.6), and higher PM10 levels were associated with fewer AD visits (r = –0.023, p < 0.001). In Period 1 (January–June), PM10 was higher during dermatitis visits (M = 59.2 vs. 55.9; t = 2.806, p = 0.005). In Period 2 (July–December), PM10 remained higher for dermatitis (M = 62.0 vs. 58.3; t = 2.693, p = 0.007). Seasonally, significant differences appeared in autumn (t = 4.472) and winter (t = 3.829), with higher PM10 during dermatitis visits (p < 0.05). Monthly analyses showed higher PM10 for dermatitis in January, February, October, and November; and higher PM10 for AD visits in April, June, July, and August (p < 0.05).

- SO2

A significant difference was found between the groups (t = 2.864, p = 0.004), with lower SO2 levels on AD visit days (13.0 < 13.8). SO2 increases were associated with fewer AD visits (r = –0.017, p < 0.05). In Period 1, SO2 was higher during dermatitis visits (M = 15.5 vs. 14.1; t = 3.849, p < 0.001). Seasonal differences were significant in spring (t = 5.895) and summer (t = 3.294), with higher SO2 during dermatitis visits (p < 0.05). Monthly analyses showed significantly higher SO2 for dermatitis in January, March, May, August, and October (p < 0.05).

- NO2

Mean NO2 levels differed significantly (t = 3.760, p < 0.001), with lower NO2 on AD visit days (11.1 < 11.5). Higher NO2 was associated with fewer AD visits (r = –0.024, p < 0.05). In Period 1, NO2 was higher during dermatitis visits (M = 11.4 vs. 10.9; t = 4.264, p < 0.001). Significant seasonal differences in spring (t = 6.131) and summer (t = 2.218) indicated higher NO2 for dermatitis (p < 0.05). Monthly analyses showed significantly higher NO2 for dermatitis in March and June (p < 0.05).

- NOx

Groups differed significantly in NOx levels (t = 4.707, p < 0.001). Atopic visits occurred on days with lower NOx (16.4 < 17.2), and NOx was negatively correlated with AD visits (r = –0.033, p < 0.001). In Period 1, NOx was higher during dermatitis visits (M = 16.1 vs. 15.3; t = 4.988, p < 0.001). Seasonally, NOx differences were significant in spring (t = 6.270) and summer (t = 2.050), favoring dermatitis (p < 0.05). Monthly comparisons showed higher NOx for dermatitis in March, April, June, and August; and higher NOx for AD visits in July, November, and December (p < 0.05).

- NO

A significant difference was observed (t = 5.301, p < 0.001), with lower NO levels on AD visit days (5.2 < 5.6). Higher NO was associated with fewer AD visits (r = –0.030, p < 0.001). In Period 1, NO was higher during dermatitis visits (M = 4.7 vs. 4.4; t = 4.988, p < 0.001). Seasonal differences were significant in spring (t = 6.434) and winter (t = 2.750), showing higher NO during dermatitis visits (p < 0.05). Monthly analyses revealed higher NO for dermatitis in January, March, April, June, and September; and higher NO for AD visits only in December (p < 0.05).

- O3

O3 differed significantly between groups (t = –6.600, p < 0.001). O3 levels were higher on days with AD visits (74.9 > 70.4), and O3 showed a positive correlation with AD visit frequency (r = 0.051, p < 0.001). In Period 1, O3 was higher during AD visits (M = 77.1 vs. 72.8; t = –7.459, p < 0.001). In Period 2, O3 remained higher for AD visits (M = 71.9 vs. 68.1; t = –2.870, p = 0.004). Seasonally, O3 was significantly higher for AD visits in spring (t = –9.800), summer (t = –2.726), and winter (t = –3.421) (p < 0.05). Monthly analyses indicated higher O3 for AD visits in January, March, April, May, June, July, and November (p < 0.05). (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of air pollution data by DDT and AD type.

The binary logistic regression model was statistically significant (χ2(11) = 660.230, p < 0.001), explaining 6.3% of the variance (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.063; Cox and Snell R2 = 0.030) with a −2 Log Likelihood of 13,304.724. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was significant (p < 0.05), indicating limited model fit, likely due to the very large sample size (n = 21,407) and class imbalance, as dermatitis cases were classified correctly at 100% while AD cases were classified at 0%. Six of the eleven predictors were significant. Girls had lower odds of receiving an AD diagnosis compared with boys (B = −0.249, Wald = 28.669, p < 0.001, OR = 0.779, 95% CI [0.711, 0.854]), whereas younger age increased AD risk (B = −0.104, Wald = 366.494, p < 0.001, OR = 0.901, 95% CI [0.891, 0.911]). Visits occurring in July–December were associated with lower AD likelihood (B = −0.466, Wald = 69.793, p < 0.001, OR = 0.601, 95% CI [0.533, 0.677]). Among meteorological variables, pressure increased AD odds (B = 0.113, Wald = 29.651, p < 0.001, OR = 1.119, 95% CI [1.075, 1.166]), while air pollution measures showed that PM10 reduced (B = −0.004, Wald = 16.919, p < 0.001, OR = 0.996, 95% CI [0.994, 0.998]) and O3 increased AD risk (B = 0.015, Wald = 68.705, p < 0.001, OR = 1.015, 95% CI [1.011, 1.018]). Wind speed, SO2, NO2, NOx, and NO were not significant predictors (p > 0.05). (Table 4).

Table 4.

Binary Logistic Regression Analysis Results for AD.

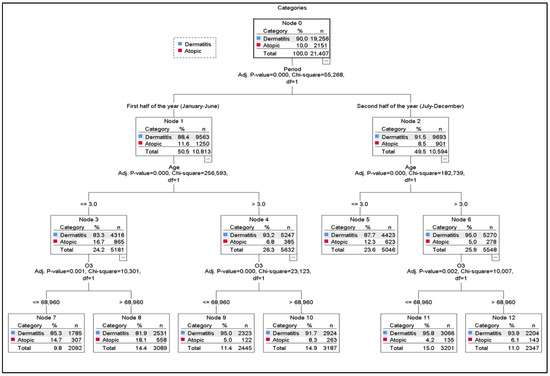

- Regression Tree

In the logistic regression analysis conducted based on the number of dermatitis and AD disease cases, the statistically significant variables of gender, period, age, pressure, PM10, and O3 were included in the classification tree model. The maximum tree depth was set to 3 to facilitate reading/understanding, while the Parent Node and Child Node were kept at their default values. Ten-fold cross-validation was applied to validate the model. The model’s risk prediction is 10.0%. This rate is the same for both resubstitution and cross-validation. This indicates that the model is reasonable for evaluation purposes. The model classified the dependent variable Dermatitis with 100% accuracy according to the Atopic type. However, it failed to classify the “Atopic” category correctly, achieving 0% success. The overall accuracy rate is 90.0%. This result indicates that the model was affected by the imbalanced dataset (the number of Dermatitis cases is very large). Consequently, the model followed a path that predicted the majority class (Dermatitis) instead of the minority class (Atopic). Ultimately, the classification tree produced a view consisting of age, period, and O3 data (Table 5).

Table 5.

Model Summary for Regression Trees.

Figure 2 shows that the root node (Node 0) contains 90.0% dermatitis and 10.0% AD cases. The first split is based on the period variable, which is statistically significant (χ2(1) = 55.3, p < 0.001). AD prevalence is higher in the first half of the year (11.6%) and decreases in the second half (8.5%).

Figure 2.

Classification Tree. Performance nodes and accuracy rates. For DDT. Node 11 (95.8 percent), Node 9 (95.0 percent), Node 12 (93.9 percent), Node 10 (92.0 percent), Node 5 (97.4 percent), Node 7 (94.9 percent), Node 8 (91.1 percent). For AD. Node 8 (18.1 percent), Node 7 (14.7 percent), Node 5 (12.3 percent), Node 10 (12.2 percent), Node 12 (6.6 percent), Node 9 (5.0 percent), Node 11 (4.2 percent).

Both periods are subsequently divided by age (χ2(1) = 255.6 and χ2(1) = 182.7; p < 0.001). Children aged ≤ 3 years display the highest AD proportions (Node 3 = 16.7%, Node 5 = 12.3%). Regardless of the period, AD is consistently more common in younger children (≤3 years) than in older ones.

In the first half of the year, both age groups are further split by O3 levels (χ2(1) = 10.3 and χ2(1) = 23.1; p < 0.05), with an O3 threshold of 68.96. In all nodes, O3 values above this threshold correspond to higher AD proportions, whereas lower levels correspond to higher dermatitis proportions.

Among children ≤ 3 years in the first period, AD rates are 14.7% when O3 is below the threshold (Node 7) and 18.1% when above it (Node 8). Among children >3 years, AD is 5.0% below the threshold (Node 9) and 8.3% above it (Node 10). In the second period, AD rates for children >3 years rise from 4.2% (Node 11) to 6.1% (Node 12) when O3 exceeds the threshold.

The nodes with the highest AD representation are Node 8 (18.1%) and Node 7 (14.7), both corresponding to children ≤ 3 years in the first half of the year. Although O3 distinguishes these nodes, the strong influence of age suggests that age remains the dominant predictor over O3 (Figure 2).

5. Discussion

This study, while examining the relationship between AD and environmental factors such as air pollution and meteorological parameters, also evaluated other DDT types in a general context. The findings suggest that AD shows a more distinct sensitivity to environmental factors, and overall trends related to DDT types were also presented. Of the total admissions included in the study, 90% were children diagnosed with DDT, and 10% were children diagnosed with AD.

A negative correlation was found between age and AD diagnoses, with a tendency for the number of AD diagnoses to increase as age decreases. Literature reports that AD first appears as early as 1 month of age, with its prevalence increasing with age and peaking at 2.5 years old [29,30]. These findings suggest that AD may be more commonly observed in early childhood.

The study found that AD diagnosis was more common in males, and this difference was statistically significant. Research in the literature also supports that the prevalence of AD in early childhood tends to be higher in males [31,32]. However, as children grow older, this trend changes, and increased sensitivity is observed among females during adolescence and adulthood [33]. In the 0–2 age group, AD was more frequently seen in males, but in the 12–16 age group, this trend reversed, with higher prevalence in females [28].

In the study, AD admissions in 2023–2024 showed a slight increase during the first three years, but in the fourth year, they almost tripled, accounting for 48.6% of the total AD admissions. Recent studies have shown a marked increase in AD consultations, particularly among pediatric populations, which can be attributed to increased awareness and improved diagnostic practices [32,34]. In recent years, there has been a reported increase in the prevalence of AD in children, with studies indicating that environmental factors, such as urban living and exposure to allergens, play a significant role in this rise [9,32,35].

The seasonal distribution of AD is characterized by fluctuations in symptom severity influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and allergen exposure [36]. The study found that there were significantly more AD admissions in the first six months compared to the second half of the year. Seasonal flare-ups of AD are commonly observed, and low ambient humidity and cold winter air exacerbate the severity of symptoms [37]. Low humidity levels and cold air increase transepidermal water loss, leading to skin dryness, and this has been associated with increased symptoms during winter in cold climates [38]. Exposure to allergens during the spring and summer months can trigger AD flare-ups, with symptoms reaching their peak, especially during these seasons [13].

In the study, it was found that AD admissions were higher in February and May compared to other periods. Similarly, studies have reported more frequent occurrences of AD during the spring [39]. However, different findings also indicate that AD is more common in the winter months [28]. These differences suggest that seasonal effects may vary depending on regional and environmental factors, and pollutants such as particulate matter (PM), formaldehyde, and volatile organic compounds can impair the function of the epidermal barrier and intensify AD symptoms [40,41]. The study found that during periods of high wind speeds, AD admissions increased, and a significant positive relationship between wind speed and AD admissions was identified. The literature indicates that wind speed can increase outpatient applications for AD [42]. However, one study reported a negative relationship between wind speed and AD symptoms [43]. Another study found no relationship between wind speed and AD [44]. These differing results suggest that the effect of wind speed on AD should be evaluated alongside other environmental factors, as symptoms may be shaped by the interaction of various environmental conditions.

In the literature, there are studies indicating that high humidity can alleviate AD symptoms [39,45]. However, there are also studies suggesting that high humidity could be an aggravating factor for symptoms [27,46]. Moreover, it was reported that low humidity increases the risk of outpatient visits for childhood AD [42]. In this study, no relationship was found between humidity and AD. These findings suggest that humidity alone is not effective, and its role in symptoms should be evaluated in conjunction with other environmental conditions.

There was no clear relationship between atmospheric pressure and healthcare utilization measurements [36]. However, in this study, it was observed that a unit increase in pressure increased AD visits by 1.117 times. Similarly, another study reported that an increase in atmospheric pressure was associated with an increase in AD applications [47]. These data suggest that further research is needed to understand the effects of atmospheric factors on AD.

Air pollutants, especially PM10, SO2, and NO2, were associated with AD symptoms both in the short and long term. Pollutants like NO2 increase AD prevalence with long-term exposure, while PM10 and SO2 lead to more severe symptoms with short-term exposure [7]. A systematic review on PM10 found a significant relationship between exposure to air pollution and increased medical visits due to AD [4]. Findings related to PM10 are consistent with previous studies. In one study, every 10 μg/m3 increase in PM10 levels was associated with a 1.08% increase in AD outpatient visits [48]. Similarly, another study found that every 10 μg/m3 increase in PM10 levels led to a 4.72% increase in AD visits [49]. In this study, PM10 shows a positive correlation with DDT visits. These findings suggest that PM10 exposure may be related to DDT symptoms, and the effects of air pollution on symptoms should be evaluated in more comprehensive research.

The study found a negative correlation between SO2 levels and AD applications. SO2 exposure has been shown to be associated with an increase in AD hospital visits and worsening symptoms [50,51]. The study found a negative correlation between SO2 levels and AD applications. However, the literature indicates that SO2 exposure is linked to increased hospital visits and worsening symptoms in AD patients [50,51]. These different findings suggest that the effect of SO2 on AD may vary depending on environmental conditions, exposure duration, and individual differences. Future research could provide more detailed insights into the complex relationship between SO2 and AD.

A negative correlation between NO2 levels and AD visits was observed in this study. Two studies conducted in China found an increase in outpatient visits for AD in children during periods of high NO2 levels [23,52]. However, a study in Korea found no relationship between NO2 and AD [50]. These contradictory findings suggest that the effects of NO2 on AD may vary based on regional environmental conditions, the composition of air pollution, and individual sensitivities.

In this study, a negative correlation was found between NOx levels and AD applications. Other studies have reported that NOx is associated with lifetime and past-year prevalence of AD and its effect on eczema incidence [53,54]. This suggests that the impact of NOx on AD may be shaped by different environmental conditions and exposure characteristics. Future studies are needed to better understand the effects of NOx.

A positive correlation between O3 levels and AD applications was found in this study. Literature suggests that acute exposure to O3 is associated with an increase in daily hospital visits due to AD and that air pollutants can be a major trigger for AD flare-ups [51]. However, some studies have found no relationship between O3 and daily hospital visits for AD [50]. This suggests that the effects of O3 on AD may depend on factors such as study methods, exposure levels, and environmental conditions.

The decision tree model used in the study evaluated the effects of air pollution and meteorological parameters on AD based on the two halves of the year. The model showed that in the first half of the year (January–June), an increase in O3 levels was associated with a significant increase in the number of AD patients. Moreover, when O3 levels were below 74,160, an increase in atmospheric pressure led to a significant rise in AD patient numbers. This supports the triggering effects of O3 exposure [51] and pressure [47] on AD.

In the second half of the year (July–December), it was observed that PM10 levels had a significant effect on the number of AD patients. The model revealed that when PM10 levels were above 55,730, an increase in wind speed resulted in an 80% increase in AD patients. However, a decrease in the number of DDT diagnoses was observed during the same period. These findings suggest that wind spreads [42] PM10 particles [4] in the atmosphere, increasing AD cases, but this effect is different in DDT types.

Furthermore, the model demonstrated that in the first half of the year, O3 and pressure levels, and in the second half, PM10 and wind speed, could predict AD patient numbers by 90%. This highlights that air pollution and meteorological factors are important parameters to consider in the management of AD. The decision tree model used in this study stands out with its 90% predictability rate compared to similar studies in the literature. The model provided the opportunity to assess the effects of air pollution and meteorological parameters seasonally and showed that these factors are crucial in patient management. Reducing environmental pollution and managing meteorological variables could be a critical strategy in controlling AD symptoms. In this process, nurses and other healthcare professionals can contribute to patient management by raising awareness and conducting educational programs to reduce environmental exposure. Developing individualized care plans could be an effective approach to minimizing the impact of such environmental and meteorological variables on health.

6. Conclusions

The decision tree model (CHAID) used in this study evaluated the effects of air pollution and meteorological factors on AD and DDT types based on seasonal differences and highlighted that these parameters are important factors to consider in disease management. The findings showed that in the first half of the year, O3 and pressure levels, and in the second half, PM10 and wind speed significantly influenced AD applications. Furthermore, the model’s 90% predictability rate provides a practical tool to evaluate the effects of air pollution and meteorological variables and to develop preventive strategies.

Reducing environmental pollution and managing meteorological variables is crucial in controlling AD symptoms. In this context, nurses and other healthcare professionals can play an effective role in educational programs aimed at reducing environmental exposure through individualized care plans and awareness campaigns. Future studies should comprehensively investigate the effects of air pollution and meteorological factors on DDT by conducting long-term data analysis in different regions.

7. Study Limitations

This study has several important limitations that should be acknowledged to correctly interpret the findings. First, the retrospective design does not allow for establishing causal relationships between air pollution, meteorological variables, and AD outcomes; only associations could be evaluated. Second, although monthly averages of meteorological and air quality indicators were used, this approach may mask short-term peaks or fluctuations, such as daily or hourly changes, which could influence symptom exacerbations. Third, the study was conducted in a single-center provincial hospital, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other regions with different climatic, environmental, or demographic characteristics.

In addition, several unmeasured confounding factors may have influenced the outcomes but could not be controlled for due to data limitations, including aeroallergen concentrations (pollen, mold), indoor environmental exposures, socioeconomic status, parental smoking, heating methods, and individual treatment or medication use. Future multicenter studies using prospective designs, enriched datasets, and high-resolution environmental measurements are needed to validate and expand these findings.

Author Contributions

M.B. conceptualized and designed the study, performed data analysis, interpreted the results, and drafted the main manuscript text. V.C. contributed to the literature review and preparation of the data collection protocol. E.N.M. managed data collection and organization and ensured the dataset was ready for analysis. B.B. developed the methodological approach and verified the accuracy of statistical analyses. N.A. assisted in interpreting findings and connecting results to the broader literature. E.K.C. contributed to data collection, organization, and the final revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Van Yüzüncü Yıl University (decision number: 2023/09-18, 18 September 2023). Only retrospectively anonymized data were used in the study, and no personal data were retained. Furthermore, all necessary institutional permissions were obtained, and the study was conducted in accordance with national regulations and ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. Only retrospectively anonymized data were used in the study, and no personal data were retained.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

In this study, an AI-based tool (GPT-5.1 and DeepL Write) was used only for language refinement and improving textual clarity; all scientific content, analyses, and conclusions were entirely generated by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AD | Atopic Dermatitis |

| CHAID | The decision tree model |

| DDT | Different Dermatitis Types |

| PM10 | Particulate matter with a diameter of 10 μm or smaller suspended in the air |

| O3 | Ozone |

| NO2 | Nitrogen Dioxide |

| SO2 | Sulfur Dioxide |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Ambient Air Quality Database, 2022 Update: Status Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/air-pollution/who-air-quality-database/2022 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. US Environmental Protection Agency Criteria Air Pollutants. 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/criteria-air-pollutants (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Boogaard, H.; Walker, K.; Cohen, A.J. Air pollution: The emergence of a major global health risk factor. Int. Health 2019, 11, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadadu, R.P.; Chee, E.; Jung, A.; Chen, J.Y.; Abuabara, K.; Wei, M.L. Air pollution and global healthcare use for atopic dermatitis: A systematic review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 1958–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadadu, R.P.; Abuabara, K.; Balmes, J.R.; Hanifin, J.M.; Wei, M.L. Air Pollution and Atopic Dermatitis, from Molecular Mechanisms to Population-Level Evidence: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, A.; Owens, K.; Patel, S.; Nicholas, M. The Impact of Air Pollution on Atopic Dermatitis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023, 23, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, Y.-Y.; Chen, Y.-H.; Hung, W.-T.; Tang, K.-T. The relationship between outdoor air pollutants and atopic dermatitis of adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 40, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldin, J.; Ratley, G.; Shobnam, N.; Myles, I.A. The clinical, mechanistic, and social impacts of air pollution on atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2024, 154, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanovic, N.; Irvine, A.D.; Flohr, C. The Role of the Environment and Exposome in Atopic Dermatitis. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2021, 8, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, M.I.; Montefort, S.; Bjorksten, B.; Lai, C.K.; Strachan, D.P.; Weiland, S.K.; Williams, H. The ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: Isaac phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006, 368, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutten, S. Atopic Dermatitis: Global Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66 (Suppl. S1), 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Barbarot, S.; Gadkari, A.; Simpson, E.L.; Weidinger, S.; Mina-Osorio, P.; Rossi, A.B.; Brignoli, L.; Saba, G.; Guillemin, I.; et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: A cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 126, 417–428.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Ahn, K. Time Trends in the Prevalence of Atopic Dermatitis in Korean Children According to Age. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2022, 14, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, F.D.; Chen, S.; Langan, S.M.; Prather, A.A.; McCulloch, C.E.; Kidd, S.A.; Cabana, M.D.; Chren, M.-M.; Abuabara, K. Association of Atopic Dermatitis with Sleep Quality in Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, e190025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Dai, Y.; Akar-Ghibril, N.; Simpson, J.; Ren, H.; Zhang, L.; Hou, Y.; Wen, X.; Chang, C.; Tang, R.; et al. Impact of Air Pollution on Atopic Dermatitis: A Comprehensive Review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 65, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathuria, P.; Silverberg, J.I. Association of pollution and climate with atopic eczema in US children. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 27, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abolhasani, R.; Araghi, F.; Tabary, M.; Aryannejad, A.; Mashinchi, B.; Robati, R.M. The impact of air pollution on skin and related disorders: A comprehensive review. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e14840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagappan, A.; Park, S.B.; Lee, S.-J.; Moon, Y. Mechanistic Implications of Biomass-Derived Particulate Matter for Immunity and Immune Disorders. Toxics 2021, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothe, W.D.; Tarbox, J.A.; Tarbox, M.B. Atopic dermatitis: Pathophysiology. In Management of Atopic Dermatitis: Methods and Challenges; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, B.E.; Leung, D.Y.M. Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis: Clinical implications. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019, 40, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaifan, D.; Crovella, S.; Soubra, L.; Al-Nesf, M.; Steinhoff, M. Fc Epsilon RI–Neuroimmune Interplay in Pruritus Triggered by Particulate Matter in Atopic Dermatitis Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutel, M.; Mosnaim, G.S.; Bernstein, J.A.; del Giacco, S.; Khan, D.A.; Nadeau, K.C.; Pali-Schöll, I.; Torres, M.J.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M.; Agache, I. The One Health approach for allergic diseases and asthma. Allergy 2023, 78, 1777–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Jiang, F.; Tan, J.; Liu, S.; Li, S.; Wu, M.; Yan, C.; Yu, G.; Hu, Y.; Yin, Y.; et al. Environmental Exposure and Childhood Atopic Dermatitis in Shanghai: A Season-Stratified Time-Series Analysis. Dermatology 2021, 238, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluhr, J.W.; Darlenski, R.; Taieb, A.; Hachem, J.; Baudouin, C.; Msika, P.; De Belilovsky, C.; Berardesca, E. Functional skin adaptation in infancy—Almost complete but not fully competent. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Stefanovic, N.; Orfali, R.L.; Aoki, V.; Brown, S.J.; Dhar, S.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Flohr, C.; Ha, A.; Mora, C.; et al. Impact of climate change on atopic dermatitis: A review by the International Eczema Council. Allergy 2024, 79, 1455–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Hanifin, J.; Simpson, E.L. Climatic Factors Are Associated with Childhood Eczema Prevalence in the United States. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 1752–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Varela, M.M.; Alvarez, L.G.-M.; Kogan, M.D.; González, A.L.; Gimeno, A.M.; Ontoso, I.A.; Díaz, C.G.; Pena, A.A.; Aurrecoechea, B.D.; Monge, R.M.B.; et al. Climate and prevalence of atopic eczema in 6- to 7-year-old school children in Spain. ISAAC PhASE III. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2008, 52, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamer, E.; Ilhan, M.N.; Polat, M.; Lenk, N.; Alli, N. Prevalence of skin diseases among pediatric patients in Türkiye. J. Dermatol. 2008, 35, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halkjaer, L.B.; Loland, L.; Buchvald, F.F.; Agner, T.; Skov, L.; Strand, M.; Bisgaard, H. Development of atopic dermatitis during the first 3 years of life: The Copenhagen prospective study on asthma in childhood cohort study in high-risk children. Arch. Dermatol. 2006, 142, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safri, M.; Putra, A.R. Early allergy symptoms in infants aged 0-6 months on breast milk substitutes. Paediatr. Indones. 2015, 55, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al Shobaili, H.A. The impact of childhood atopic dermatitis on the patients’ family. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2010, 27, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, I.; Stojkovic, A.; Velickovic, V.; Zivanovic Macuzic, I.; Ilic, M. Atopic Dermatitis in Children Under 5: Prevalence Trends in Central, Eastern, and Western Europe. Children 2023, 10, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdualrasool, M.; Al-Shanfari, S.; Booalayan, H.; Boujarwa, A.; Al-Mukaimi, A.; Alkandery, O.; Akhtar, S. Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke and Prevalence of Atopic Dermatitis among Adolescents in Kuwait. Dermatology 2018, 234, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, C.; Uğur, C. Evaluation of Dermatology Consultations Requested from the Pediatric Clinic. Genel Tıp Derg. 2022, 32, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, K.; Chu, S.; Giesey, R.L.; Mehrmal, S.; Uppal, P.; Nedley, N.; Delost, G.R. The global, regional, and national burden of atopic dermatitis in 195 countries and territories: An ecological study from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. JAAD Int. 2021, 2, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamann, C.; Andersen, Y.; Engebretsen, K.; Skov, L.; Silverberg, J.; Egeberg, A.; Thyssen, J. The effects of season and weather on healthcare utilization among patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 1745–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischer, A.B. Atopic dermatitis: The relationship to temperature and seasonality in the United States. Int. J. Dermatol. 2018, 58, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.H. Management and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis in Primary Care. Can. Prim. Care Today 2023, 1, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, Y.-M.; Lee, J.Y.; Yang, H.-K.; Kim, H.; Cho, J.; Ahn, K.; Kim, J. Seasonal variation and monthly patterns of skin symptoms in Korean children with atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017, 38, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werfel, T.; Heratizadeh, A.; Niebuhr, M.; Kapp, A.; Roesner, L.M.; Karch, A.; Erpenbeck, V.J.; Lösche, C.; Jung, T.; Krug, N.; et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis on grass pollen exposure in an environmental challenge chamber. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 96–103.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, E.-H.; Oh, I.; Jung, K.; Han, Y.; Cheong, H.-K.; Ahn, K. Symptoms of atopic dermatitis are influenced by outdoor air pollution. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 495–498.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Nie, H.; Shi, C. Short-term effects of meteorological factors on childhood atopic dermatitis in Lanzhou, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 15070–15081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, F.; Li, S.; Liu, S.; Wu, M.; Yan, C.; Tan, J.; Yu, G.; Hu, Y.; et al. Relative impact of meteorological factors and air pollutants on childhood allergic diseases in Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Fan, L.; Xie, L.; Ren, Y.; Li, L. Associations between air pollution, climate factors and outpatient visits for eczema in West China Hospital, Chengdu, south-western China: A time series analysis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 32, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibekwe, P.; Ukonu, B. Impact of Weather Conditions on Atopic Dermatitis Prevalence in Abuja, Nigeria. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2019, 111, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onunu, A.; Eze, E.; Kubeyinje, E. Clinical profile of atopic dermatitis in Benin City, Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2007, 10, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Belugina, I.; Yagovdik, N.; Belugina, O.; Belugin, S. The impact of meteorological factors on the incidence of infantile atopic dermatitis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2024, 63, e405–e414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Xiong, X.; Liang, F.; Tian, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Pan, X. The interactive effects between air pollution and meteorological factors on the hospital outpatient visits for atopic dermatitis in Beijing, China: A time-series analysis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 2362–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Liang, F.; Tian, L.; Schikowski, T.; Liu, W.; Pan, X. Ambient air pollution and the hospital outpatient visits for eczema and dermatitis in Beijing: A time-stratified case-crossover analysis. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2018, 21, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.H.; Park, S.; Cho, M.K.; Kim, S. Associations of particulate matter with atopic dermatitis and chronic inflammatory skin diseases in South Korea. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 47, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, J.; Qian, Z.; Gong, Y.; Zhong, J.; Yang, R.; Wan, C.; Zhang, S.; Ning, D.; Xian, H.; et al. Association between air pollution and atopic dermatitis in Guangzhou, China: Modification by age and season. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 184, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Gu, H.; Li, M.; Chen, R.; Xiao, X.; Zou, Y. Air Pollution and Weather Conditions Are Associated with Daily Outpatient Visits of Atopic Dermatitis in Shanghai, China. Dermatology 2022, 238, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pénard-Morand, C.; Raherison, C.; Charpin, D.; Kopferschmitt, C.; Lavaud, F.; Caillaud, D.; Annesi-Maesano, I. Long-term exposure to close-proximity air pollution and asthma and allergies in urban children. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 36, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnass, W.; Hüls, A.; Vierkötter, A.; Krämer, U.; Krutmann, J.; Schikowski, T. Traffic-related air pollution and eczema in the elderly: Findings from the SALIA cohort. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2018, 221, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).