1. Introduction

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), workplace accidents represent a global concern due to their significant social and economic impacts [

1]. In psychiatric hospitals, such accidents also occur, arising from workers’ exposure to physical, chemical, biological, ergonomic, and mechanical hazards (e.g., sharp objects) during routine professional activities [

2,

3,

4].

In addition, professionals (e.g., nursing technicians, nurses) are exposed to patients’ aggressive behaviors, which constitute a unique occupational hazard rarely encountered in other work environments [

5]. Consequently, violence-related incidents are a major concern for managers, particularly because they directly affect nurses and physicians [

6,

7].

Despite this concern, underreporting of aggression-related accidents is common in psychiatric hospitals [

8]. This underreporting occurs for various reasons, such as professionals’ reluctance to report incidents or the perception that aggression is an inherent aspect of their work [

4]. Whether reported or not, such incidents contribute to job dissatisfaction, which in turn may increase the risk of further violence [

9,

10].

In this context, the safety climate—defined as employees’ perceptions of organizational practices regarding occupational health and safety and overall risk perception—becomes a key factor [

11,

12,

13]. A positive safety climate not only enhances job satisfaction but also reduces accidents [

13,

14]. Safety climate is directly influenced by managerial values and practices (e.g., adequacy of training, provision of protective equipment, quality of safety management systems), as well as internal communication and employee involvement in occupational health and safety [

11,

12,

13].

Given this scenario, the research problem addressed in this study is how computational simulation can support decision-making to optimize the safety climate in psychiatric settings. Accordingly, the main objective is to analyze occupational injuries and safety conditions in a psychiatric hospital in southern Brazil and subsequently develop a computational simulation using system dynamics (SD).

This study is justified for three reasons: (i) a systematic literature review (SLR) revealed no studies applying computational simulation to analyze workplace injuries in psychiatric hospitals; (ii) SD is a computational method for quantitatively analyzing causal relationships over time, yet no scientific evidence was found of its application to injury analysis in psychiatric hospitals [

4,

15]; and (iii) the safety indicators developed in this study may assist other researchers in designing control mechanisms for safety management in similar work environments.

2. Materials and Methods

The development of this research was carried out in five stages. First, the case study site was selected. Next, data were collected and subjected to descriptive analysis. In the third stage, safety indicators were developed to enhance understanding of the existing conditions. Subsequently, System Dynamics (SD) was applied to (i) identify how variables were interrelated and influenced safety conditions, and (ii) structure the simulation model. Finally, the model was validated, followed by a sensitivity analysis to examine the effects of parameter variations on the variables.

2.1. Case Study Site

The study was conducted in a public hospital specializing in psychiatric care and chemical dependency, inaugurated on 10 November 1941. The hospital is located in southern Brazil, in the municipality of São José, state of Santa Catarina.

The research focused on the inpatient ward, and ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (No. 2595066). This ward was selected because it accounted for 71 accidents over the past seven years—representing 48% of all reported incidents—and was identified by hospital administration as the most critical unit in the facility.

A total of twenty-five nursing professionals, the occupational safety engineer, the safety technician, and the head nurse participated in this study. The details of their participation are provided in the following sections.

2.2. Data Collection and Descriptive Analysis

Ten technical visits were conducted to provide the researchers with a comprehensive understanding of the working conditions and dynamics in the inpatient ward. Simultaneously, additional relevant information for this study was collected.

To analyze the multiple causes of workplace injuries, a document review was performed using all Accident Reports (CAT) recorded by the occupational safety officer, as in previous studies [

4]. Official records from the past seven years were analyzed, and three key pieces of information were extracted: injury date, occupation of the injured worker, and causal agent. The collected data were tabulated and stored using Microsoft Excel.

Further information regarding occupational injuries was obtained through targeted visits to the ward and structured interviews with the head nurse and the occupational safety engineer.

The information gathered during the interviews was categorized into four groups, based on previous studies [

16,

17,

18]. The first group addressed organizational factors, specifically whether activities were supported by detailed Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). The second group examined the relationship between personal protective equipment (PPE) use and injuries. The third group focused on organizational measures proposed for injury mitigation. Finally, the fourth group considered the level of PPE usage among staff.

To complement data collection, an exploratory questionnaire was designed and administered to capture the sociodemographic characteristics of the nursing staff, their perceptions of occupational risks, and self-reported workplace injuries. The questionnaire (

Table A1) was based on previous research [

19,

20,

21]. All 25 nursing staff members completed the questionnaire.

Injuries (Accident) incidence was examined from two sources: official records (CAT) and self-reports from the nursing staff. This dual approach aimed to identify possible underreporting, a common issue in psychiatric work environments [

8,

20].

Based on the collected data, initial descriptive analyses were performed. First, a general analysis of the hospital was conducted, identifying the total number of injuries, the most affected professionals, and the main causal agents. Subsequently, the analysis focused on the nursing staff, identifying the primary causes of injuries and staff perceptions of occupational risks.

At this stage, the safety technician contributed to the research by providing access to injury reports and clarifying any questions that arose. In addition, the safety perception of the twenty-five nursing professionals was assessed.

2.3. Occupational Safety Indicators

Based on on-site visits, document analysis, structured interviews, the questionnaire, and the initial descriptive analyses, occupational safety indicators were developed. The hospital previously lacked metrics for monitoring, which hindered effective evaluation of existing conditions, implemented measures, and their outcomes. Developing such indicators is particularly important given the recognized need for decision-support tools in occupational safety management [

22].

The Multi-Criteria Decision Aid Constructivist (MCDA-C) methodology was employed, as it has been applied in both industrial and academic settings for the development of performance indicators [

22,

23]. This methodology emphasizes stakeholder involvement in the decision-making process and is structured in three phases: (1) problem structuring and indicator definition, (2) evaluation of potential actions, and (3) formulation of recommendations.

This study focused on problem structuring (Phase 1). It began with a meeting to identify the main stakeholders, which enabled the definition of Primary Evaluation Elements (PEEs)—in this case, the nursing staff working in the ward.

Subsequently, Action-Oriented Concepts (AOCs) were defined. These concepts guide desired actions and establish minimum expected outcomes for occupational safety aspects. They were derived through three approaches: (i) literature review; (ii) case study analysis; and (iii) perceptions of the stakeholders included in the PEEs. The concepts were grouped by area, represented in cognitive maps, and validated by the hospital’s occupational safety engineer.

Next, Strategic Objectives (SOs) were linked to each concept. For each SO, Elementary Points of View (EPVs) were defined, serving as the basis for constructing the indicators. Each indicator was assigned an ordinal scale to measure the level of compliance, and all indicators were validated by the hospital’s occupational safety engineer.

For easier interpretation, the indicators were classified into five categories according to their results: (i) very poor, 0–20% (red); (ii) poor, 21–40% (orange); (iii) intermediate, 41–60% (gray); (iv) good, 61–80% (light green); and (v) excellent, ≥81% (dark green).

Therefore, the development of the indicators, as well as their validation, involved the direct participation of the hospital’s occupational safety engineer. It is further emphasized that these indicators were subsequently used as parameters for constructing the simulation model.

2.4. Structuring of the Simulation Model

System Dynamics (SD) was employed to structure the simulation model. According to Lucas et al. [

15], SD modeling comprises three main stages: causal definition, structural description, and quantification/projection.

(a) Causal definition: This stage describes the system using a Causal Loop Diagram (CLD), which illustrates relationships among variables through arrows indicating cause-and-effect links. A positive sign on the arrow denotes a direct relationship, while a negative sign indicates an inverse relationship [

24].

In this study, the CLD was developed in Vensim software (version 10.1.5) based on information obtained from the preceding methodological steps. Constructing an effective CLD is essential for developing the Stock and Flow Diagram (SFD), which serves as the foundation for simulation modeling [

25]. To ensure accuracy, the CLD was validated by both the hospital’s occupational safety engineer and the head nurse.

The results of this stage are presented concisely, as the main focus of this article is the simulation model. Therefore, the CLD outcomes are reported through the description of closed feedback loops, which is the standard approach for presenting this type of structure [

15].

(b) Structural description: Mathematical modeling was used to develop the SFD, which includes all variables necessary to numerically describe the causal relationships identified in the previous stage, thereby enabling computational simulation [

24].

The simulation was structured to capture the behavior of variables over time, based on stock and flow concepts. Stocks (also referred to as levels) represent conserved quantities in the system, while flows (also referred to as rates) are variables that modify those quantities [

24,

26].

As the modeling aimed to understand the system’s behavior over time, its mathematical foundation consisted of ordinary differential equations, assuming that stock levels result from inflows minus outflows [

24,

26].

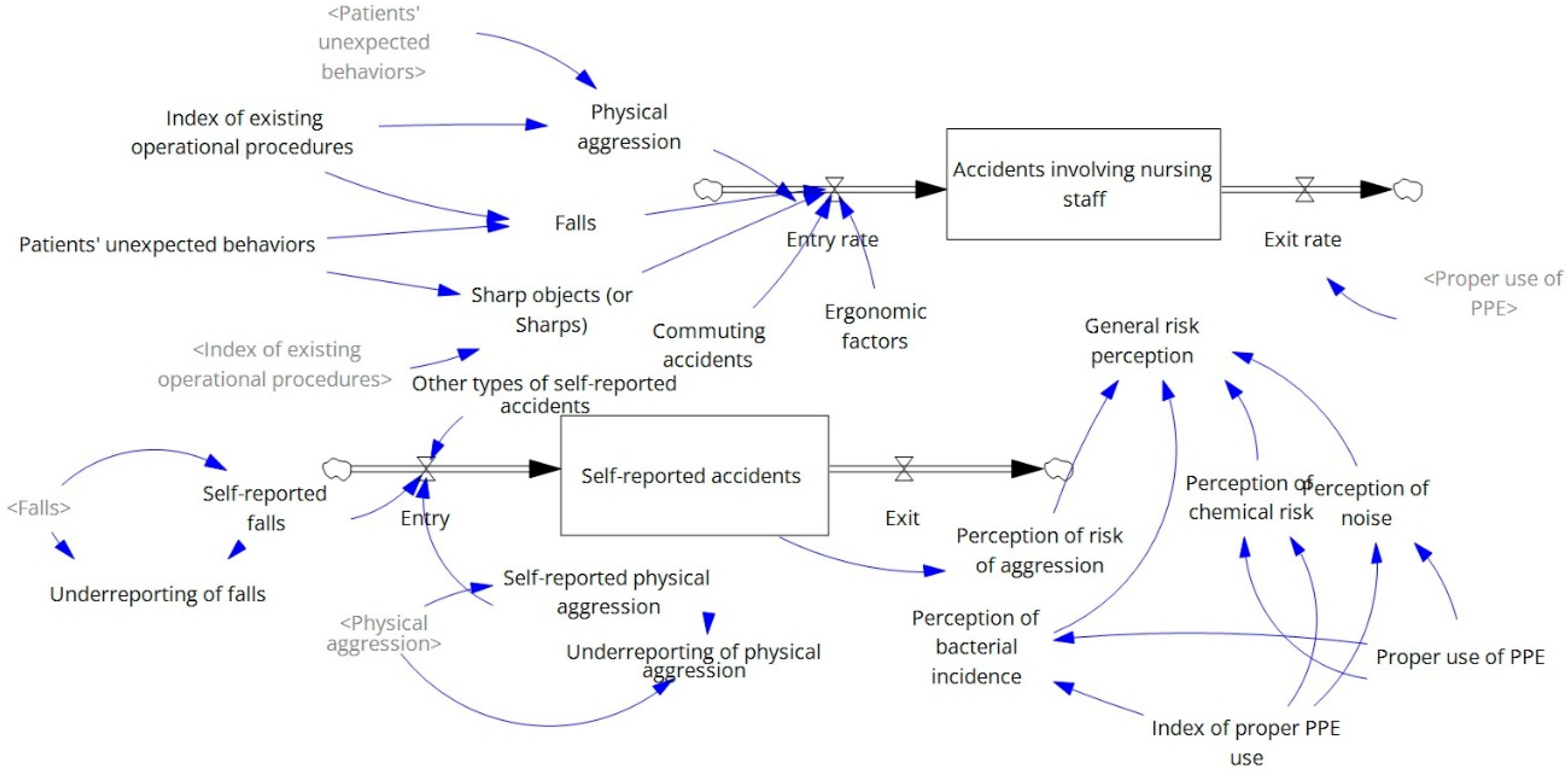

The simulation model was designed to represent the system over one year, with monthly time steps, using the Euler integration method. It was developed in Vensim (version 10.1.5), and the variables, units, and mathematical equations are detailed in

Table A2. Input variables for the model were defined based on descriptive analyses and the safety indicators.

(c) Quantification or projection: After consistency analysis and validation, the mathematical equations from the structural description were used to run computational simulations and evaluate variable behavior under parameter changes.

The model underwent a consistency analysis to assess the compatibility between the proposed structure and the system’s actual behavior. This evaluation was based on a ten-test checklist (

Table A3), adapted from Lucas et al. [

15]. In parallel, the model was validated by the hospital’s occupational safety engineer.

Once the model was calibrated, sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate how parameter variations affected the variables.

2.5. Sensitivity Analysis

The purpose of the sensitivity analysis was to evaluate how the model responded to modifications in the parameters of specific variables. As shown in

Table 1, the parameters of three variables were adjusted: (i) the rate of proper PPE usage; (ii) the rate of unexpected patient behaviors; and (iii) the rate of activities with established operational procedures.

The selection of parameters for adjustment was based on the scientific literature and the safety conditions identified in the case study. The aim of these simulations was to examine their impact on three key outcomes: overall perception of occupational risk, annual injury rate, and underreporting of injuries. All simulations were conducted using Vensim software.

It should be emphasized that only the variables presented in

Table 1 were analyzed in the sensitivity analysis.

3. Results

The sample had a mean age of 36 years and an average length of service of 7 years. Of the 71 officially recorded injuries (accidents) involving nursing staff, 69% occurred with women and 31% with men. Furthermore, 46% (sample number = 33) of the injuries were due to aggression; 23% (sample number = 16) resulted from falls; 15% (n = 11) were caused by sharp objects; 10% (sample number = 7) were commuting injuries; and 6% (sample number = 4) were related to ergonomic factors.

Based on the administered questionnaires, it was found that 50% of the staff had previously experienced an injury, with self-reports totaling 93 incidents. The primary cause of self-reported injuries was aggression (sample number = 58; 62.37%), followed by falls (sample number = 23; 24.73%). Consequently, 22 self-reported injuries were not recorded in the official reports.

Regarding perceptions of occupational risks: (i) 100% of the respondents reported exposure to physical and psychological stress (ergonomic risk); (ii) 100% identified physical aggression as a constant risk (mechanical hazard); (iii) 93% reported the presence of bacteria in the environment (biological risk); (iv) 93% indicated exposure to tobacco smoke (cigarettes and straw) as a chemical risk; and (v) 71.4% reported exposure to noise.

3.1. Safety Indicators

The 23 proposed indicators provided a clearer understanding of the existing safety conditions. Overall, the results of six indicators (27%) were classified as “Good” or “Excellent,” five as “Intermediate” (23%), and 12 indicators (55%) were classified as “Poor” or “Very Poor”.

As shown in

Table 2, “Storage quality”, “Quantity of stored products” and “Disease reports” were classified as “Excellent” (dark green). “Level of PPE protection provided,” “Availability of resources for equipment acquisition,” and “Level of PPE usage by staff” were classified as “Good” (light green).

At an intermediate level (gray), it was observed that half of the workers participating in safety training still used PPE incorrectly. This category also included the indicator assessing whether PPE use prevented contamination by bacteria, viruses, or protozoa.

Indicators classified as poor (orange) included “Number of staff using PPE correctly,” as well as: “Training provided for each PPE according to requirements,” “PPE with technical specification sheet to assess effectiveness,” and “Number of times workers checked PPE condition before use”.

Indicators classified as very poor (red) were: (i) “Rate of activities with described Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs),” (ii) “Rate of activities with written SOPs, including identified risks, PPE, and emergency procedures,” (iii) “Internal protocols to validate PPE,” and (iv) “Staff trained to verify PPE protection levels according to the risk of each activity”.

3.2. Identified Causal Relationships

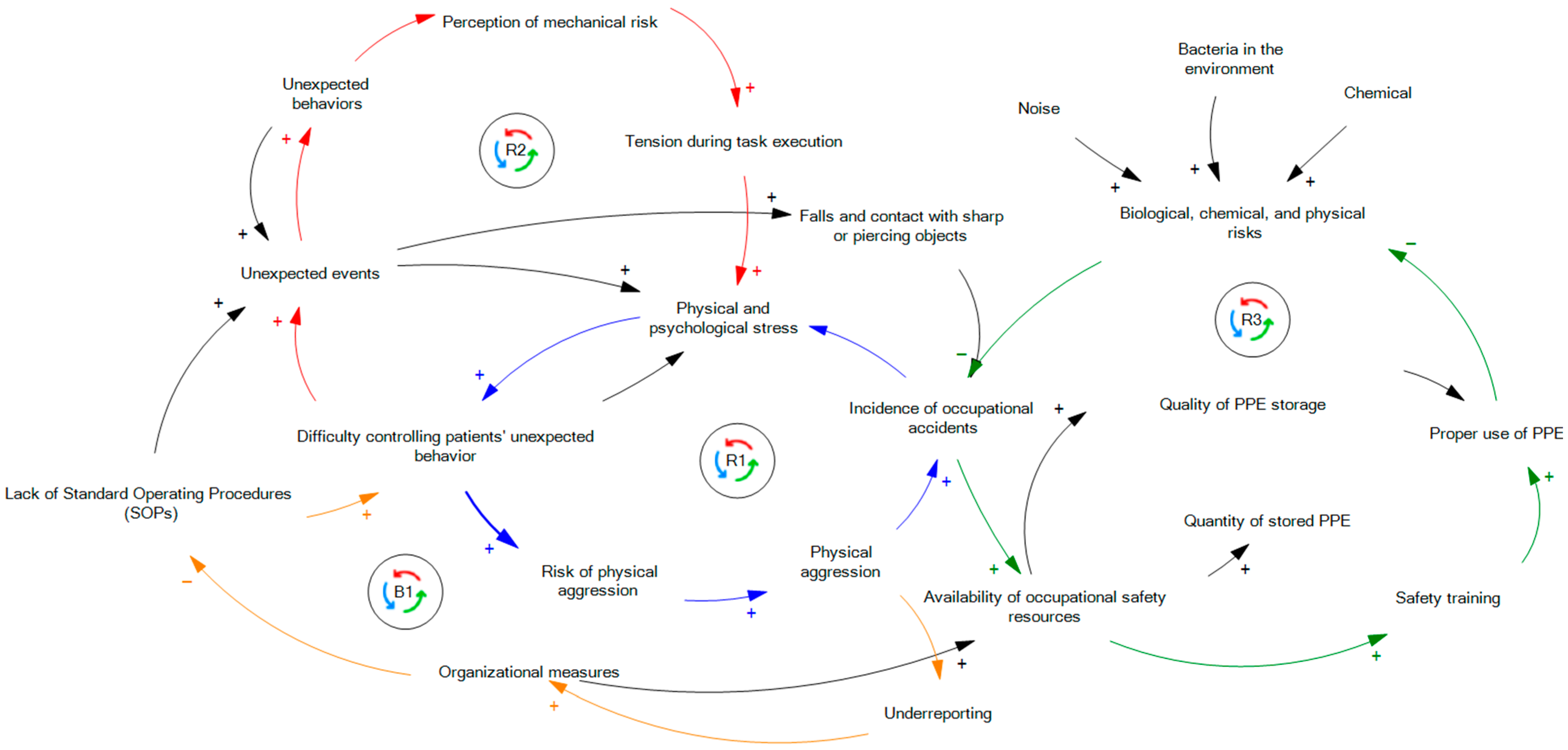

In the structured and validated Causal Loop Diagram (CLD), four loops were identified (

Figure 1), which are represented by the different colors. The first loop (R1) showed that the absence of well-established standard operating procedures hindered the control of unexpected patient behaviors. This increased the risk of physical aggression and, consequently, the number of aggressive incidents in the ward. The occurrence of such injuries (accidents) elevated the stress levels of professionals, directly affecting the proper execution of procedures necessary for patient management.

The second loop (R2) highlighted that the incidence of unexpected patient behaviors directly influenced the nursing staff’s perception of high injury risk. This perception resulted in tension and a constant state of alertness during procedures, leading to peaks in stress. This mental state impaired professional performance, which, combined with the lack of well-established procedures, made patient management more difficult and increased the occurrence of unexpected behaviors.

The third loop (R3) demonstrated that greater availability of resources for the occupational safety area directly enhanced safety training. This, in turn, positively influenced the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and mitigated the incidence of physical, chemical, and biological risks in the environment. The reduction in these hazards led to a lower incidence of injuries associated with them.

The fourth loop (B1) indicated that the incidence of physical aggression directly affected the underreporting rate. The higher the underreporting, the lower the hospital’s capacity to implement effective measures to mitigate the problem. Consequently, necessary procedures to manage patients in the face of unexpected behaviors, particularly to prevent aggression, were not implemented.

Finally, it was observed that incidents of physical aggression were directly related to the three main causes of injuries involving nursing staff: (i) aggression-related injuries; (ii) falls; and (iii) injuries involving sharp objects.

3.3. Computational Simulation

Figure 2 graphically represents the structured computational simulation model. Based on this model, the first simulation focused on the proper use of PPE, which was currently 40%, as identified in the safety indicator analysis. By increasing this rate by 10%, the nursing staff’s overall perception of occupational risk decreased from 89.35% to 76.48%, primarily due to changes in the perception of chemical, physical, and biological hazards. However, the perception of aggression risk remained unchanged, as did the injury (accident) rate among nursing staff.

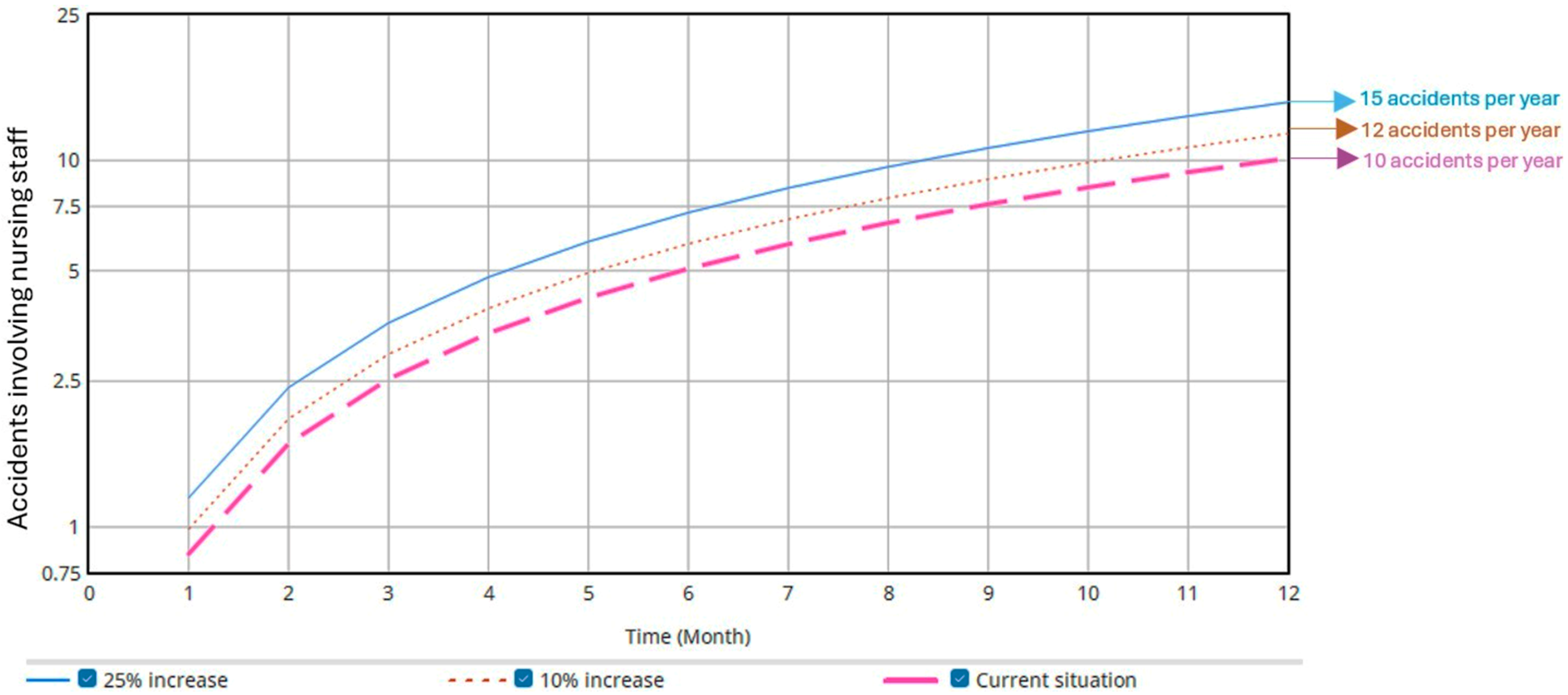

The second simulation involved increasing the rate of unexpected patient behaviors by 10% and 25%. As shown in

Figure 3, the annual injury (accident) rate increased by 1.68 (equivalent to two additional injuries (accidents) per year) and 4.28 (equivalent to five additional accidents per year), respectively. Additionally, due to underreporting, the rate of self-reported injuries (accidents) per year also increased (

Figure 4) by 2.31 (equivalent to three additional accidents per year) and 5.78 (equivalent to six additional accidents per year), respectively.

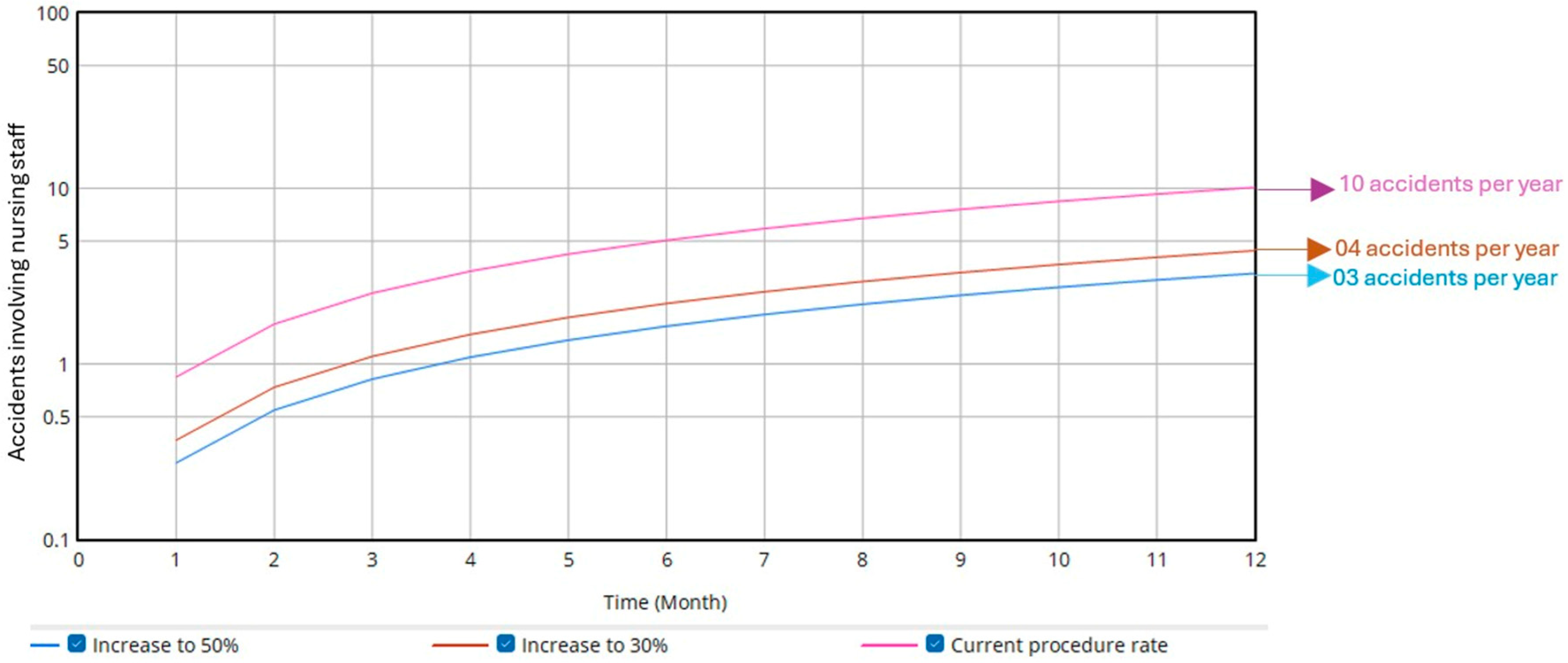

The third simulation focused on the rate of existing operational procedures, which include the protocols required to manage unexpected patient behaviors. The simulation increased the current rate (10%) to 30% and 50%. As shown in

Figure 5, the annual injury (accident rate decreased by 5.71 (equivalent to six fewer accidents per year) and 6.85 (equivalent to seven fewer accidents per year), respectively. Additionally, overall occupational risk perception decreased from 89.35% to 72.68% and 69.35%, respectively.

4. Discussion

When analyzing occupational injuries (accidents) involving nursing staff, physical aggression was identified as the primary cause. The occurrence of unexpected behaviors and acts of violence by patients has also been reported in previous studies [

4,

19,

27], highlighting the need to prioritize this issue to ensure occupational safety in these environments.

However, since aggression is recurrent, many affected professionals prefer not to report such incidents, either out of fear of punishment or being held responsible [

8,

20]. This was confirmed in the present analysis, as 22 injuries were self-reported by staff but not recorded in the hospital’s official records.

Regarding safety-related aspects, positive indicators were observed for personal protective equipment (PPE), particularly in terms of quality, storage, and distribution. Nevertheless, there was a clear need to increase proper PPE use and, importantly, to expand operational procedures for performing activities.

Focusing safety efforts on the acquisition and proper use of PPE is crucial to prevent various types of hazards, including physical, chemical, and biological risks. However, this alone is insufficient, as the main sources of accidents in this type of environment stem from patient behavior and aggression [

5,

6,

16].

It was observed that, although the hospital emphasized preventive measures, it lacked strategies that could significantly impact the safety climate, enabling professionals to feel more confident in managing patient behaviors and, importantly, in reporting all incidents of aggression and violence. This is particularly relevant, as measures that directly influence the safety climate have been shown to be more effective in the long term [

12].

The increase in unexpected patient behaviors directly affected both the injury (accident) rate and underreporting, as identified through computational simulation. For example, the results showed that a 25% increase in unexpected behaviors could result in up to six additional injuries (accidents) per year, highlighting the risks posed to staff in the absence of new control measures [

4].

In this context, the existence of well-established protocols for managing these behaviors is essential [

28,

29]. Expanding documentation of activities through the implementation of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) is therefore critical. It was identified that only 10% of activities currently had such procedures. If this indicator were increased to 50% of activities, for instance, the annual number of injuries (accidents) could be reduced by seven, and overall risk perception would be directly improved.

Thus, the introduction of SOPs, followed by well-defined training protocols, demonstrates organizational support for daily practices, enhances staff’s sense of safety, and is essential for controlling and mitigating incidents of violence and aggression in psychiatric settings [

6,

17].

The simulation results, therefore, enhanced analytical capacity regarding safety conditions and reinforced the need for critical actions to ensure health and well-being. These include clearly defined procedures for control and containment, as well as specialized training in conflict resolution strategies, which should be incorporated into the SOP for each activity. These findings align with previous studies [

15,

20], which highlighted (i) the importance of computational simulation for optimizing workplace conditions, and (ii) how well-defined protocols can assist nurses in managing unexpected behaviors and physical aggression.

5. Conclusions

The nursing staff at the psychiatric hospital was exposed to occupational risks, with physical aggression identified as the primary cause of injuries and a constant mechanical hazard. Although the hospital demonstrated concern regarding the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), effective measures to increase compliance remain necessary. Moreover, the formalization of procedural protocols was identified as a key need, aiming to standardize internal actions that enhance safety during task execution.

The computational simulation indicated that increasing proper PPE use contributed to a reduction in the nursing staff’s overall perception of occupational risk, particularly regarding chemical, physical, and biological hazards. Conversely, an increase in unexpected patient behaviors directly led to a higher incidence of injuries, highlighting this factor as a significant aggravator of working conditions. Increasing the rate of operational procedures, including protocols for managing such behaviors, proved to be the most effective intervention, as it reduced both the number of injuries and perceived risk.

The results obtained from the computational simulation enhanced analytical capacity and demonstrated that the safety climate in the psychiatric hospital is directly influenced by four main factors: (i) work environments that minimize exposure to hazards; (ii) well-established internal procedures for managing diverse situations, particularly those addressing actions in response to unexpected patient behaviors; (iii) a team trained according to internal procedures and aware of the importance of preventive actions; and (iv) effective internal indicators regarding the storage, validity, training, and use of PPE.

The main limitation of this study was the lack of temporal availability to implement the actions proposed in the simulation, particularly regarding the integration of operational procedures into daily practice. In addition, the nursing team sample consisted of 25 staff members. Therefore, future research is suggested to: (i) develop studies that simulate safety conditions in psychiatric hospitals, subsequently implement the proposed actions, and perform practical verification; and (ii) use computational simulation to better understand the dynamics of aggression-related injuries, aiming to identify all relevant variables and causal relationships, as well as factors that could directly contribute to mitigating these incidents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.L. and J.B.; methodology, R.L. and C.R.; software, R.L.; validation, R.L., C.R. and E.M.; formal analysis, R.L. and E.M.; investigation, E.M. and C.R.; resources, E.M. and C.R.; data curation, E.M., R.L. and C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.L. and C.R.; writing—review and editing, E.M. and C.R.; visualization, J.B.; supervision, E.M.; project administration, E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (No. 2595066).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Exploratory questionnaire. Reprinted from ref. [

4].

Table A1.

Exploratory questionnaire. Reprinted from ref. [

4].

| Question |

|---|

| What is your email address? |

| Do you agree with the Free and Informed Consent Form (FICF)? |

| What is your gender? |

| How old are you? |

| What is your weight? |

| What is your height? |

| Are you a practitioner of physical activities? |

| Are you a smoker? |

| Do you have a chronic or degenerative disease? Which? |

| What is your marital status? |

| Do you have children? |

| What is your work schedule? |

| What is your education level? |

| What is your assignment? |

| What is your professional time? |

| Working time at a psychiatric hospital? |

| Describe your activities throughout the working day. |

| Do you take breaks during your workday? |

| Is there an appropriate place to rest? |

| Indicate the physical hazards you believe you are exposed to. |

| Indicate the chemical hazards you believe you are exposed to. |

| Indicate the biological hazards you believe you are exposed to. |

| Indicate the ergonomic hazards you believe you are exposed to. |

| Indicate the risks of accidents you believe you are exposed to. |

Table A2.

Simulation equations.

Table A2.

Simulation equations.

| Variable | Acronym | Equation | Unit |

|---|

| Accidents involving nursing staff | AINS | | Accidents/month |

| Self-reported accidents | SRA | | Self-reported/month |

| Physical aggression | PA | (PUB/IEOP)/CONST | PA/month |

| Falls | FA | (PUB/IEOP)/CONS | FA/month |

| Sharp objects (or Sharps) | SO | (PUB/IEOP)/COS | SO/month |

| Self-reported falls | SRF | FA/0.695652 | SRF/month |

| Underreporting of falls | UF | 1-(FA/SRF) | UF/month |

| Self-reported physical aggression | SPA | PA/0.568965 | SPA/month |

| Underreporting of physical aggression | UPA | 1-(PA/SPA) | UPA/month |

| Perception of risk of aggression | PRA | (PUB/IEOP)/5 | Rate |

| Perception of chemical risk | PCR | 0.372/PPPE | Rate |

| Perception of noise | PN | 0.2856/PPPE | Rate |

| Perception of bacterial incidence | PBI | 0.372/PPP | Rate |

| General risk perception | GRP | (PRA + PN + PCR + PBI)/4 | Rate |

| Index of existing operational procedures | IEOP | Constant | dmnl |

| Patients’ unexpected behaviors | PUB | Constant | dmnl |

| Indicator of physical aggression | CONST | Constant | dmnl |

| Falls indicator | CONS | Constant | dmnl |

| Indicator regarding sharps accidents | COS | Constant | dmnl |

| Commuting accidents | CA | Constant | CA/month |

| Ergonomic factors | EF | Constant | EF/month |

| Other types of self-reported accidents | OTSA | Constant | OTSA/month |

| Proper use of PPE | PPPE | Constant | dmnl |

Table A3.

Model Validation Checklist. Reprinted from ref. [

15].

Table A3.

Model Validation Checklist. Reprinted from ref. [

15].

| Model Validation Checklist |

|---|

| 1. Structure Assessment |

| ☐ Verify that the model structure is consistent with relevant descriptive knowledge of the system. |

| ☐ Check whether the level of aggregation is appropriate. |

| ☐ Assess whether decision rules adequately capture the behavior of actors in the system. |

| ☐ Conduct partial model tests to evaluate the intended rationality of decision rules. |

| ☐ Develop disaggregated submodels and compare their results with aggregated formulations. |

| ☐ Disaggregate suspicious structures and repeat sensitivity and policy analyses. |

| 2. Dimensional Consistency |

| ☐ Test all equations using dimensional analysis software. |

| ☐ Inspect equations for parameters that lack real-world meaning. |

| 3. Parameter Assessment |

| ☐ Confirm that parameter values are consistent with descriptive and numerical knowledge of the system. |

| ☐ Verify that all parameters have real-world counterparts. |

| ☐ Use partial model tests to calibrate subsystems. |

| ☐ Apply judgment-based methods (interviews, expert opinions, focus groups, archival materials, direct experience). |

| ☐ Develop disaggregated submodels to estimate relationships supporting aggregated models. |

| 4. Extreme Conditions |

| ☐ Inspect each equation to ensure plausibility under extreme inputs. |

| ☐ Test the model’s response to extreme values of each variable, both individually and in combination. |

| ☐ Subject the model to large shocks and extreme conditions. |

| 5. Integration Error |

| ☐ Halve the time step and observe behavioral changes. |

| ☐ Use alternative numerical integration methods and compare results. |

| 6. Behavior Reproduction |

| ☐ Verify whether the model reproduces system behavior qualitatively and quantitatively. |

| ☐ Assess whether the model generates the observed modes of system behavior. |

| ☐ Compare frequencies and phase relationships between simulated variables and real-world data. |

| ☐ Compute statistical measures of fit between model output and empirical data. |

| ☐ Compare qualitatively the shapes of variables, asymmetries, amplitudes, unusual events, and relative phases. |

| ☐ Examine model responses to test inputs, shocks, and noise. |

| 7. Behavioral Anomalies |

| ☐ Perform loop knockout analysis (zeroing major effects). |

| ☐ Replace equilibrium assumptions with disequilibrium structures and examine responses. |

| 8. Replication |

| ☐ Test whether the model replicates behavior across different instances of the same system. |

| ☐ Calibrate the model for the widest possible variety of related systems. |

| 9. Surprise Behavior |

| ☐ Maintain accurate, complete, and dated records of simulations. |

| ☐ Verify whether the model generates previously unrecognized behaviors. |

| ☐ Use the model to simulate system responses under new conditions. |

| ☐ Investigate and resolve discrepancies between model behavior and system understanding. |

| 10. Sensitivity Analysis |

| ☐ Perform univariate sensitivity analyses (varying one parameter at a time). |

| ☐ Perform multivariate sensitivity analyses (varying multiple parameters simultaneously). |

| ☐ Test behavioral sensitivity: assess whether generated modes of behavior change significantly. |

| ☐ Test policy sensitivity: evaluate whether policy implications change significantly when assumptions about parameters, limits, and aggregation vary within plausible uncertainty ranges. |

| ☐ Use optimization methods to identify the best parameters and policies. |

| ☐ Use optimization methods to identify parameter combinations that generate implausible results or policy reversals. |

References

- Yeshitila, D.; Kitaw, D.; Belayneh, M. Application of Machine Learning Modeling for the Upstream Oil and Gas Industry Injury Rate Prediction. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Health 2024, 14, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, K.d.; Vilela, R.A.d.G.; Cardoso, M.R.A.; Andrade, D.F.d.; Maeda, S.T. Work constraints leads to accident: Questionnaire validity and a qualitative interpretation of the cutoff point. Saf. Sci. 2017, 93, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camino López, M.A.; Fontaneda, I.; González Alcántara, O.J. Musculoskeletal disorders among nursing assistants in Spain; a comparative study between old people’s homes and hospitals. Saf. Sci. 2021, 137, 105182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E.C.; Riascos, C.E.M.; de Mattos, D.L.; Neto, R.A.; de Sousa Carneiro, P.M.; Merino, G.S.A.D.; Merino, E.A.D. Systemic relations among the variables involved in occupational accidents of the nursing team in a psychiatric hospital. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2023, 45, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibunja, B.K.; Musembi, H.M.; Kimani, R.W.; Gatimu, S.M. Prevalence and Effect of Workplace Violence against Emergency Nurses at a Tertiary Hospital in Kenya: A Cross-Sectional Study. Saf. Health Work 2021, 12, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colizzi, M.; Comacchio, C.; Garzitto, M.; Napoli, G.; Battiston, C.; Tam, T.; Bertoli, M.; Anzallo, C.; Palese, A.; Balestrieri, M. Is a No-Restraint Policy Associated with Increased Aggression Towards Healthcare Professionals Among Inpatient Psychiatric Units? A 16-Year Retrospective Observational Study Conducted in Italy. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3779–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N.; Heponiemi, T. Violence towards health care workers in a Public Health Care Facility in Italy: A repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, R.K.; Poku, K.A. Experiences of frontline nursing staff on workplace safety and occupational health hazards in two psychiatric hospitals in Ghana. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, J.V.; Piacentino, D.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Moser, S.; Cappelletti, S.; Weissenberger, G.; Pompili, M.; Conca, A. Aggression and Violence Toward Healthcare Workers in a Psychiatric Service in Italy: A Retrospective Questionnaire-Based Survey. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2020, 208, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchini, L.; Colombo, C.; Aiolfi, I.; Alajmo, V.B.; Beckman, E.M.; Marcocci, L.; Ragone, N.; Travaini, G. A descriptive study of suffered and witnessed aggressions in two rehabilitative italian units. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2020, 17, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A.; Hart, P.M. The impact of organizational climate on safety climate and individual behavior. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaak, V.; Vashdi, D.; Bar-Noy, D.; Kostisky, H.; Hirschmann, S.; Grinshpoon, A. Enhancing the Safety Climate and Reducing Violence Against Staff in Closed Hospital Wards. Workplace Health Saf. 2017, 65, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyreborg, J.; Lipscomb, H.J.; Nielsen, K.; Törner, M.; Rasmussen, K.; Frydendall, K.B.; Bay, H.; Gensby, U.; Bengtsen, E.; Guldenmund, F.; et al. Safety interventions for the prevention of accidents at work: A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, H.H. Key factors of near miss reporting behaviour at work and the interaction of safety climate: A review based on reciprocal safety model. Int. J. Reliab. Saf. 2025, 19, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.L.C.; Merino, E.A.D.; da Silva, L.B.; dos Santos Leite, W.K.; Norte Silva, J.M.; Rique Júnior, J.F. Influence of extended working hours and physical recovery on absenteeism in the footwear industry from a system dynamics model. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2024, 30, 1167–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E.C.; da Silva, L.B.; de Souza, E.L.; Leite, W.K.S.; da Silva, J.M.N. Influence of environmental variables on students’ cognitive performance in indoor higher education environments. Work 2024, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaak, V.; Vashdi, D.; Steiner-Lavi, O. The long-term effects of a prevention program on the number of critical incidents and sick leave days. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2018, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varpula, J.; Välimäki, M.; Lantta, T.; Berg, J.; Lahti, M. Nurses’ perceptions of risks for occupational hazards in patient seclusion and restraint practices in psychiatric inpatient care: A focus group study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocabiyik, N.; Yildirim, S.; Turgut, E.O.; Turk, M.K.; Ayer, A. A study on the frequency of violence to healthcare professionals in a mental health hospital and related factors. Dusunen Adam 2015, 28, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.F.; Kuo, S.F.; Tsai, H.T.; Kao, C.C.; Traynor, V.; Chou, K.R. Prevalence of workplace violent episodes experienced by nurses in acute psychiatric settings. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, K.H.J.F.; Zeitoune, R.C.G.; Portela, L.F.; Tracera, G.M.P.; Moraes, K.G.; Figueiró, R.F.S. Factors related to the risk of illness of nursing staff at work in a psychiatric institution. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2020, 28, e3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riascos, C.E.M.; Ensslin, S.R.; Merino, E.A.D. Development of performance indicators for Occupational Health and Safety: A constructivist multicriteria approach for PPE. Production 2021, 31, e20200106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensslin, L.; Dutra, A.; Ensslin, S.R. MCDA: A constructivist approach to the management of human resources at a governmental agency. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2000, 7, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mattos, D.L.; Ariente Neto, R.; Merino, E.A.D.; Forcellini, F.A. Simulating the influence of physical overload on assembly line performance: A case study in an automotive electrical component plant. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 79, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, M.; Purdy, N.; Neumann, W.P. Using system dynamics modelling to show the effect of nurse workload on nurses’ health and quality of care. Ergonomics 2020, 63, 952–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouloiz, H.; Garbolino, E.; Tkiouat, M.; Guarnieri, F. A system dynamics model for behavioral analysis of safety conditions in a chemical storage unit. Saf. Sci. 2013, 58, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.Y.; An, F.R.; Xiang, Y.T.; Qi, Y.K.; Ungvari, G.S.; Newhouse, R.; Yu, D.S.; Lai, K.Y.; Yu, L.Y.; Ding, Y.M.; et al. Frequency and risk factors of workplace violence on psychiatric nurses and its impact on their quality of life in China. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 210, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scozzafave, M.C.S.; Leal, L.A.; Soares, M.I.; Henriques, S.H. Psychosocial risks related to the nurse in the psychiatric hospital and management strategies. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2019, 72, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziaferi, S.G.; Sourtzi, P.; Kalokairinou, A.; Sgourou, E.; Koumoulas, E.; Velonakis, E. Risk Assessment of Physical Hazards in Greek Hospitals Combining Staff’s Perception, Experts’ Evaluation and Objective Measurements. Saf. Health Work. 2011, 2, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).