Lessons Learned from Air Quality Assessments in Communities Living near Municipal Solid Waste Landfills

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Number of chemicals involved (i.e., a single chemical or a mixture of chemicals).

- -

- Size of landfill and magnitude of emissions.

- -

- Proximity to and susceptibilities of nearby populations.

- -

- Levels of contaminants of concern (i.e., concentration at or above the effect level).

- -

- Environmental conditions (e.g., prevailing wind patterns) [4].

Background on ATSDR Site-Specific Evaluations

2. Materials and Methods

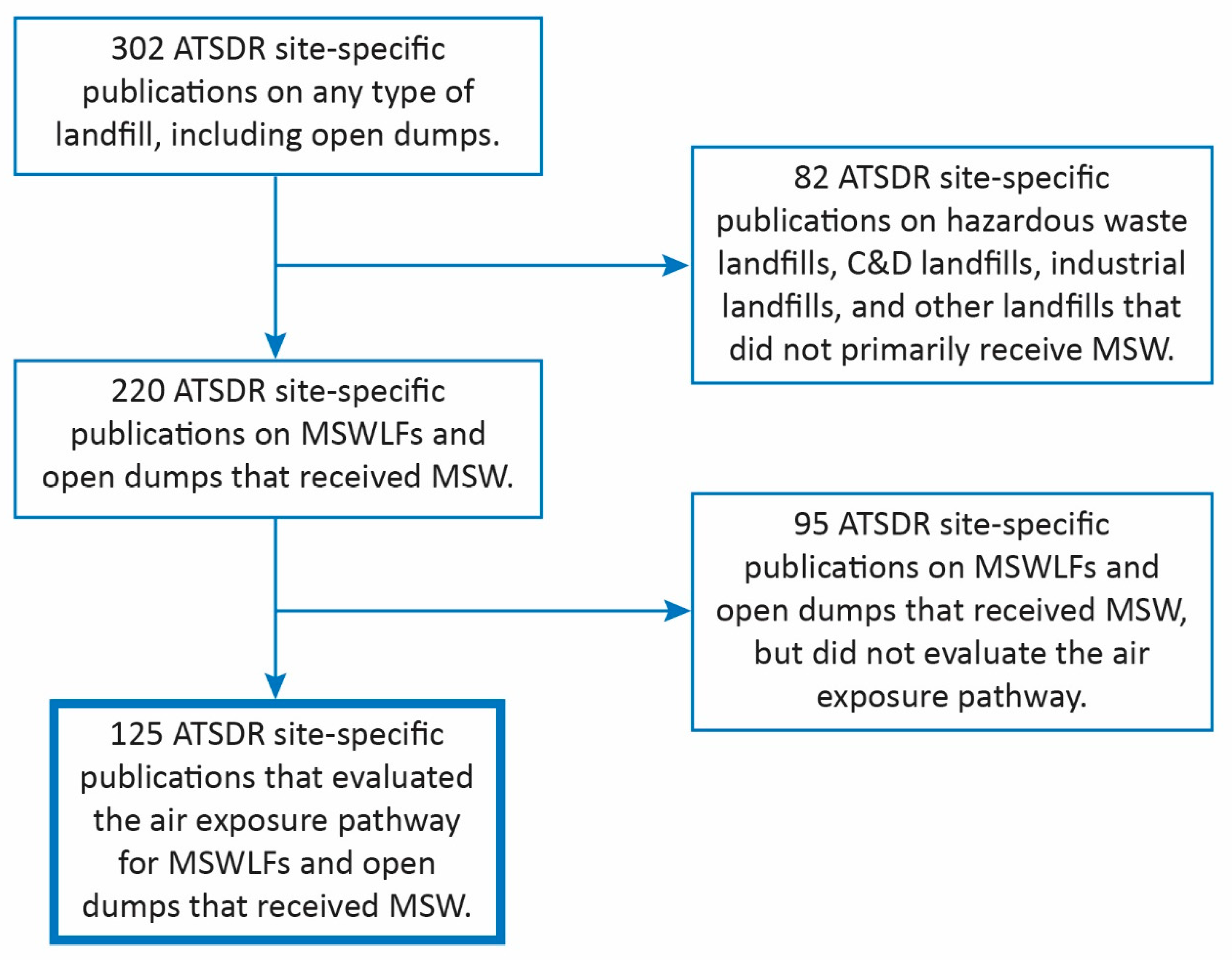

2.1. Document Identification

2.2. Characterization of the Selected MSWLFs and Open Dumps

- The year of construction;

- The landfill’s size in acres;

- Whether the site was active or closed at the time of the ATSDR’s publication;

- Whether the site had a landfill gas-collection system, and if so, whether it was a passive or active system;

- Whether or not the site had been an open dump;

- Whether the site had ever had a landfill fire;

- Whether redevelopment activities occurred that resulted in public use atop previous disposal sites.

2.3. Public Health Conclusion Categorization

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

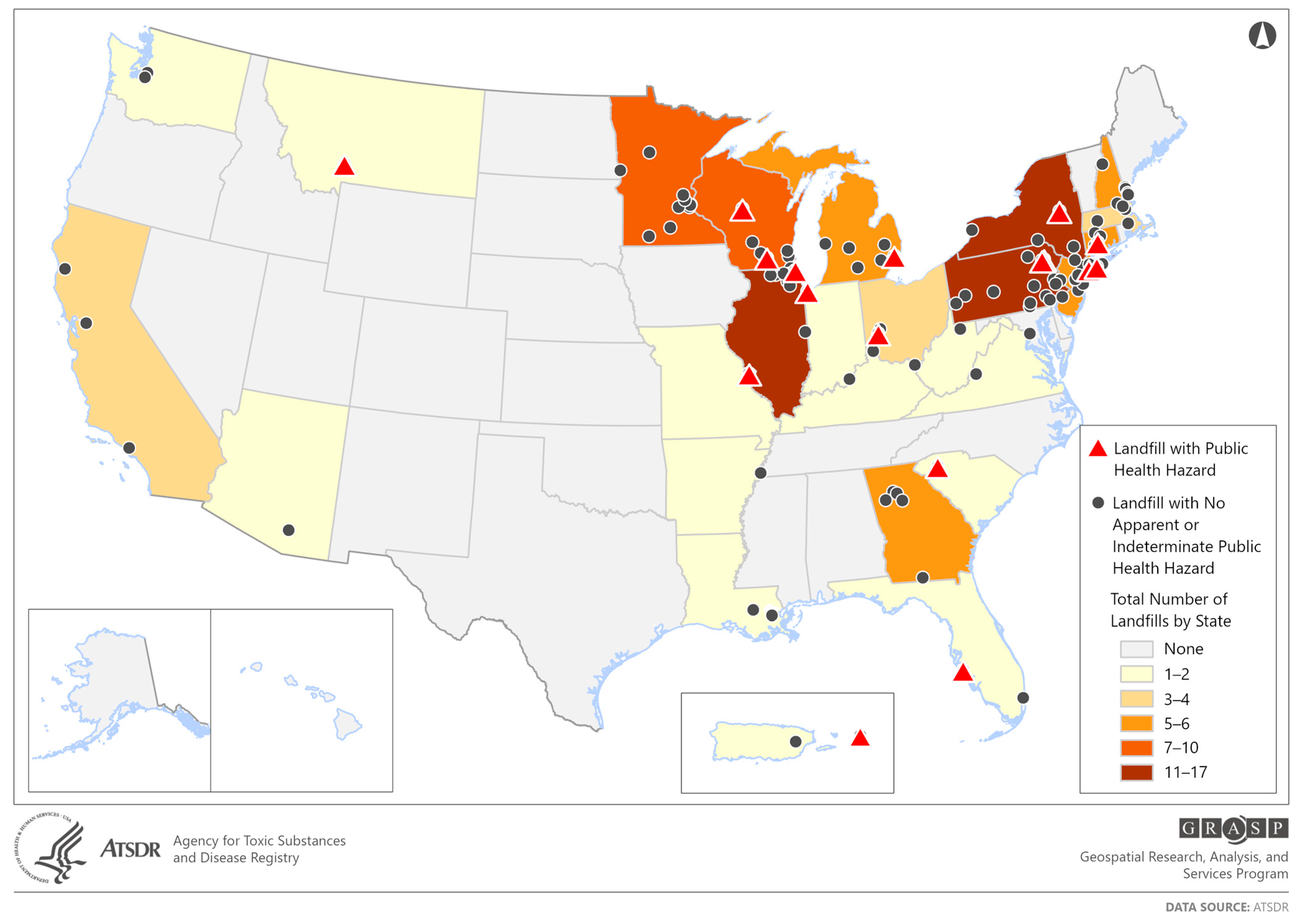

3.1. Public Health Hazards Associated with Inhalation Exposures to Toxic Substances

3.2. Public Health Hazards Associated with Methane Gas Reaching Flammable Levels

4. Discussion

Review of Key Findings

- Promoting the installation of a gas-collection and control system at existing MSWLFs;

- Using engineered sanitary landfills;

- Using the revised criteria in Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) part 258, integrations of the final rule technical revisions and clarifications of the national emission standards for hazardous air pollutants (NESHAP) for MSWLFs;

- Implementing the landfill gas energy project/landfill methane outreach program [14].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). Landfill Gas Primer—An Overview for Environmental Health Professionals. November 2001. Division of Health Assessment and Consultation. ATSDR. Department of Health and Human Services. 2001. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/hac/landfill/html/intro.html (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Sudweeks, S.; Elgethum, K.; Abadin, H.; Zarus, G.; Irvin, E. Applied Toxicology at the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Encyclopedia of Toxicology. 4th ed. 2024. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/referencework/abs/pii/B9780128243152005558?fr=RR-2&ref=pdf_download&rr=99a19027db212601 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 2025. Municipal Solid Waste Landfills Website. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/landfills/municipal-solid-waste-landfills (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- De Titto, E.; Savino, A. 2024. Human Health Impact of Municipal Solid Waste Mismanagement: A Review. Advances in Environmental and Engineering Research. LiDSEN Publishing Inc. 5. Available online: https://www.lidsen.com/journals/aeer/aeer-05-02-014 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Fazzo, L.; Minichilli, F.; Santoro, M.; Ceccarini, A.; Seta, M.D.; Bianchi, F.; Comba, F.; Martuzzi, M. Hazardous waste and health impact: Systematic review of the scientific literature. Environ. Health 2017, 16, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqua, A.; Hahladakis, J.N.; Al-Attiya, W.A. An overview of the environmental pollution and health effects associated with waste landfilling and open dumping. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 58514–58536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ncube, F.; Ncube, E.J.; Voyi, K. A systematic critical review of epidemiological studies on public health concerns of municipal solid waste handling. Perspect. Public Health 2017, 137, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattiello, A.; Chiodini, P.; Bianco, E.; Forgione, N.; Flammia, I.; Gallo, C.; Pizzuti, R.; Panico, S. Health effects associated with the disposal of solid waste in landfills and incinerators in populations living in surrounding areas: A systematic review. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinti, G.; Bauza, V.; Clasen, T.; Medlicott, K.; Tudor, T.; Zurbrugg, C.; Vaccari, M. Municipal solid waste management and adverse health outcomes: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Z.; Schutz, C.; Kjeldsen, P. Trace gas emissions from municipal solid waste landfills: A review. Waste Manag. 2021, 119, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIOSH (The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health). NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods. In NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods (2014-151), 5th ed.; NIOSH: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/nmam/default.html (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 2022. Air Monitoring Methods. Ambient Monitoring Technology Information Center. 2022. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/amtic/air-monitoring-methods (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). Public Health Assessment Guidance Manual (PHAGM). 2025. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pha-guidance/index.html (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). Landfill Methane Outreach Program (LMOP). 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/lmop (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Semkiw, E.; Wenzel, J.; Garoutte, J.; LeCoultre, T.D.; Frazier, L.; Evans, E. Evaluation of Exposure to Landfill Gases in Ambient Air. Bridgeton Sanitary Landfill. Health Consultation. Public Comments Version. Bridheton, St. Louis County, Missouri. Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services & Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Atlanta, GA 3033. 2018. Available online: https://semspub.epa.gov/work/07/30381971.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Semkiw, E.; Wenzel, J.; Garoutte, J.; LeCoultre, T.D.; Frazier, L.; Evans, E. Evaluation of Exposure to Landfill Gases in Ambient Air. Bridgeton Sanitary Landfill. Health Consultation. Bridheton, St. Louis County, Missouri. Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services & Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2022. Available online: https://health.mo.gov/living/environment/hazsubstancesites/pdf/landfill-hc-508.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- NYSDOH (New York State Department of Health). Public Health Assessment: Port Washington Landfill, North Hempstead, New York. New York State Department of Health & Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 1995. Available online: https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/cursites/csitinfo.cfm?id=0202155 (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- City of Bozeman and Tetra Tech Inc. Draft Revised Corrective Measures Assessment Bozeman Landfill Gallatin County, Montana. Tetra Tech Project No. 114-560446. 2014. Available online: https://bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/bozemandailychronicle.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/4/12/412355fc-3dd5-11e4-a762-e7467bdfe729/54188bddc356a.pdf.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Elgethun, K. Bridger Creek Community Vapor Intrusion, Bozeman, Montana. Health Consultation. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Atlanta, GA 30333. 2015. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/BridgerCreekCommunity/Bridger%20Creek%20Community_HC_11302015_508.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Sutton, D.S.; Schnell, F.C.; Guevara-Rosales, L.; Moore, S.; Kowalski, P.; Pomales, A.; Sagendorph, W.K. ERSI Landfill Taylor, Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania. Health Consultation. EPA Facility ID: PAD069601763. Cost Recovery Nr. A903. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2010. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/ERSILandfillHC/ERSILandfillHC03222010.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Arunachalam, S.; Ahmed, F.; Helverson, R.; Wener, L.S.; Tobinson, R. Keystone Sanitary Landfill. Dunmore, Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania. Health Consultation. Public Comment Version. Pennsylvania Department of Health and Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Regitry. 2017. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/KeystoneSanitaryLandfill/Keystone_Sanitary_Landfill_HC(PC)_12-14-2017-508.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Langmann, D.M.; Schnell, F.C.; Johnson, R.H.; Gouzie, G. Petitioned Public Health Assessment. Bovoni Dump, St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. Public Health Assessments & Health Consultations. ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). 1998. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/tsp/pha/PHAHTMLDisplay.aspx?docid=1384&pg=0 (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Morse, L.; Mechant, R.; Freed, J. On- and Off-Site Surface Soil. Former Proctor Rad Landfill. Health Consultation. Sarasota County, Florida. EPA Facility ID: FLN000409986. Florida Department of Health and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2008. Available online: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/FormerProctorRoadLandfill/Former_Proctor_Road_Landfill%20HC%209-30-2008.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Pestana, E.; Geschwind, S.; Toal, B.; Perman, G.; House, G.; House, L.; Gilling, R.; UliH2Sh, G. Old Southington Landfill Public Health Assessment. Southington, Hartford County, Connecticut. CERCLIS Nr. CTD980670806. Connecticut Department of Public Health and Addiction Services & Agency for toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). 1995. Available online: https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/dph/ehdw/haz-waste-site-phas/ct_old-southington-landfill_pha-f_391995.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Sweet, W.; McRae, T. Public Health Evaluation of Gas Vent Sampling Data Reports. Old Southington Landfill. Health Consultation. Southington, Hartford County, Connecticut. CERCLIS Nr. CTD980670806. Connecticut Department of Public Health and Addiction Services & Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). 2005. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/hac/pha/OldSouthingtonLandfill/OldSouthLandfill.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Rusnak, S.M.; Sweet, W.; UliH2Sh, G. Technical Review of the Risk Assessment for Gas Vent Volatile Organic Compound Data. Southington Landfill. Health Consultation. Southington, Hartford County, Connecticut. CERCLIS Nr. CTD980670806. Connecticut Department of Public Health and Addiction Services & Agency for toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). 2006. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/OldSouthingtonLandfill093006/OldSouthingtonLandfillHC093006.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Baughman, T.A.; Runkle, K.; Fabinski LGodfrey, G.; Inserra, S.; Baldwin, G. Yeoman Creek and Edwards Field Landfills. Public Health Assessment. Waukegan, Lake County, IL. CERCLIS Nr. ILD980500102. 30 September 1997. Illinois Department of Public Health and Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20161217071700/https:/www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/PHA.asp?docid=626&pg=0 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Baughman, T.A.; Godfrey, G. Yeoman Creek Landfill Health Consultation. Waukegan, Lake County, IL. CERCLIS Nr. ILD980500102, 17 June 1998. Illinois Department of Public Health and Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20161217071702/https:/www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/PHA.asp?docid=935&pg=0 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Baughman, T.A.; Robison, A.; Erlwein, B. Yeoman Creek Landfill Health Consultation. Waukegan, Lake County, IL. Illinois Department of Public Health and Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2004. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/hac/pha/YeomanCreekLandfill072104-IL/YeomanCreekLandfill072104-IL.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Jackson, D.; Hossom, C.; Sudweeks, S.; Metcalf, S.; Gillig, R.; Wilder, L. Gary Development Landfill Health Consultation. Gary, Lake County, Indiana. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2012. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/hac/pha/garydevelopmentlandfill/garydevelopmentlandfillhc08082012.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Smith, V.A.; Lee, R.; Fabinski. South Macom Disposal Authority #9, 9A Public Health Assessment. St. Clair Shores, Oakland County, Michigan. CERCLIS Nr. MID069826170. 23 February 1995. and Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/PHA.asp?docid=455&pg=0 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Crua, J.; Kaplan, J.; Block, A.; Gillig, R.; UliH2Sh, G. Islip Municipal Sanitary Landfill Public Health Assessment. a/k/a Blydenburgh Road Landfill, Hauppauge, Suffolk County, New York. CERCLIS Nr. NYD980506901. 22 January 1996. New York State Department of Health and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20161217075820/https:/www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/PHA.asp?docid=220&pg=0 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Rafferty, C.J.; Kaplan, J.; Block, A.; Gillig, R.; UliH2Sh. Johnstown City Landfill Public Health Assessment. Johnstoen, Fulton County, New York. CERCLIS Nr. NYD980506927. 8 March 1995. New York State Department of Health and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20161217075843/https:/www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/PHA.asp?docid=221&pg=0 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Schuck, M.E.; Wilson, L.R.; Kaplan, J.H.; Block AGillig, R.; UliH2Sh, G. Port Washington Landfill Public Health Assessment. North Hempstead, Nassau County, NY. CERCLIS Nr. NYD980654206. 2 November 1995. New York State Department of Health and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20161217080537/https:/www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/PHA.asp?docid=255&pg=0 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- [ODH] Ohio Department of Health and ATSDR (Godfrey GD, Greim W, North Sanitary (AKA Valleycrest) Landfill Health Consultation. Dayton, Montgomery County, OH. CERCLIS Nr. OHD980611875. 30 July 1998. Bureau of Environmental Health & Toxicology Ohio Department of Health and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20161217114615/https:/www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/PHA.asp?docid=656&pg=0 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Shelley, T.; Safay, B.; Freed, J. Old Simpsonville Dump #2 Health Consultation. Simpsonville, Greenville, County, SC. EPA Facility ID: SCD981474893. 5 November 2004. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/OldSimpsonvilleDump2-111204-SC/OldSimpsonvilleDump111504-SC.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Nehls-Lowe, H.; Fabinski, L.; Greim, W. 1994. Spickler Landfill Public Health Assessment. Spencer, Marathon County, Wisconsin. EPA Facility ID: WID980902969. 9 April 1994. Wisconsin Department of Health and Social Services and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20161217102025/https:/www.atsdr.cdc.gov/HAC/pha/PHA.asp?docid=771&pg=0 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Goldrina, J.; Fabinski, L.; Jordan-Izaquirre Greinm, W.; Williams, R.C. 1994. Stoughton City Landfill Public Health Assessment. Stoughton, Dane County, Wisconsin. Available online: https://apps.dnr.wi.gov/rrbotw/download-document?docSeqNo=284134&sender=activity (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). Toxicological Profiles. 2025. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxicological-profiles/about/index.html (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Burg, T.; Zarus, G. Community exposures to chemicals through vapor intrusion: A Review of Past ATSDR Public Health Evaluations. J. Environ. Health 2013, 75, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund, B.; Regan, C.; Rago, R.; Beckley, L. Overview of State Approaches to Vapor Intrusion: 2023 Update. Groundwater Monitoring & Remediation Published by Wiley Periodicalls LLC on Behalf of National Ground Water Association. Available online: https://ngwa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/am-pdf/10.1111/gwmr.12627 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Manjunatha, G.S.; Lakshmikanthan, P.; Chavan, D.; Baghel, D.S.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, R. Detection and extinguishing approaches for municipal solid waste landfills fires: A mini review. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaguer, E.P. The potential ozone impacts from landfills. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, D.; Milani, S.; Al, L.; Perucci, C.A.; Forastiere, F. Systematic review of epidemiological studies on health effects associated with management of solid waste. Environ. Health 2009, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, C.; Denney, J.; Mbonimpa, E.G.; Sklagley, J.; Bhowmik, R. A Review on municipal solid waste-to-energy trends in the USA. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbay, G.; Jones, M.; Gadde, M.; Sah, S.; Attarwala, T. Design and operation of effective landfills with minimal effects on the environment and human health. Review article. J. Environ. Public Health 2021, 2021, 6921607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Data Element | Count | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Decade PHA ‡ or HC ‡ was issued. | ||

| 1980s | 2 | 1.60 |

| 1990s | 62 | 49.6 |

| 2000s | 40 | 32.0 |

| 2010s ¶ | 21 | 16.8 |

| Landfill or open dump status at time of evaluation. | ||

| Active | 25 | 22.0 |

| Closed | 100 | 78.0 |

| Public use/access of landfill or open dump surface? § | ||

| Yes | 30 | 20.0 |

| No | 95 | 80.0 |

| According to the PHA/HC, did the site have a subsurface fire? | ||

| Yes | 14 | 11.0 |

| No or not specified | 111 | 89.0 |

| Data Element | Count | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PHAs and HCs for MSWLFs * and open dumps that reached a conclusion for the air exposure pathway. | 125 | 100 |

| Subset of PHAs † and HCs † that evaluated the air exposure pathway and found either no or no apparent public health hazard. | 107 | 86 |

| Subset of PHAs † and HCs † for which the ATSDR ‡ or its public health partner concluded a public health hazard for the air exposure pathway. Further breakdown: | 18 | 14 |

| Public health hazard due to exposure to toxic substances. | 5 | |

| Public health hazard due to unsafe methane accumulations. | 12 | |

| Public health hazard due to exposure to both toxic substances and unsafe methane accumulations. | 1 |

| Site | Year Disposal Began | Operational Status | Acres | §§ Substances with Public Health Hazard | Description | References and Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1950s | Closed | 52 | RSCs and SO2 | The closed landfill is a former limestone quarry, with mostly municipal solid waste disposed of at the site. It is part of an NPL site. Community concerns about emissions increased after a “subsurface smoldering event” (i.e., underground landfill fire) was detected. This event led to considerable remediation efforts at the landfill. Ambient air-monitoring for RSCs and SO2 found levels that might be harmful to health. Exposures to the highest concentrations might have aggravated chronic respiratory disease (e.g., asthma), aggravated chronic cardiopulmonary disease, and caused other respiratory effects (e.g., difficulty breathing, tightness in the chest). These concerns were greatest during the remediation efforts following the landfill fire, and the remedial efforts effectively reduced the landfill’s air quality impacts. | Semkiw et al., 2018, 2022 [15,16] |

| 2 | 1974 | Closed | 113 | H2S and VOCs | The closed landfill is an NPL * site. The location was originally used to mine sand and gravel, before it was used as a construction and demolition debris landfill, and eventually as an MSWLF †. In the early 1990s, the landfill’s leachate collection system did not function properly, and several million gallons of leachate accumulated in a landfill section. This caused increased H2S emissions, with fenceline ambient air concentrations greater than 1 ppm—levels that the ATSDR ‡ concluded were a public health hazard. Installation of an active landfill gas-venting system and upgrades to the leachate collection system reduced H2S concentrations to safe levels. VOCs in indoor air (particularly benzene and vinyl chloride) were a public health hazard, due to vapor intrusion of landfill gases that migrated in the subsurface and into homes, some of which were located 100 feet from the landfill boundary. This hazard was addressed through the installation and operation of an active gas-venting system. | NYSDOH (New York State Department of Health). 1995 [17]; |

| 3 | 1970 | Closed | 200 | Radon and VOCs (Benzene, 1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene, 1,2-Dichloroethane, and 1,2-Trans Dichloroethene). | The closed, unlined landfill accepted municipal solid waste for nearly 40 years. Two residential developments were constructed while the landfill was active, with some homes being located less than 500 feet from the landfill cells. Due to concerns regarding vapor intrusion, indoor air sampling occurred at nearby houses. The public health hazard finding was based on estimated lifetime cancer risks greater than 1-in-10,000 from multiple VOCs (including benzene, chloroform, and 1,2-dichloroethane). The document also noted that exposures to naturally occurring radon contributed to considerably higher cancer risks, though the radon issues were not attributed to landfill releases. Affected homes were equipped with sub-slab depressurization units, which have reduced cancer risks below levels of health concern. | Cit of Bozemana and Tetra Tech 2014 [18]; Elgethun K. 2015 [19] |

| 4 | 1973 | Closed | Not specified | Odors, H2S and SO2 | Multiple landfills operated on adjacent properties, including two MSWLF cells and a construction and demolition (C&D) § debris landfill. Residences were located less than 100 feet from the C&D landfill cell. Ambient air-monitoring revealed that H2S levels were “high enough to cause temporary respiratory discomfort to those with asthma, and perhaps even in some without asthma who suffered from other preexisting respiratory conditions.” One peak SO2 concentration reached levels that could have caused clinically significant symptoms among residents with asthma. In response to the air quality impacts, landfill operators installed a gas-collection system that helped prevent landfill gases from reaching nearby residents. The HC focuses on the C&D landfill at the site, but acknowledged that all three adjacent landfills have sulfur compound emissions. | Sutton et al., 2010 [20] |

| 5 | 1970s | Active | ~1000 | H2S, NH3, VOCs (Benzene and formaldehyde, and particulate matter. | Approximately three-fourths of the 7000 tons of waste disposed of daily at the landfill was municipal solid waste, with the remainder being C&D debris, non-hazardous industrial waste, and other non-hazardous waste. Ambient air monitoring conducted in the area found several toxic substances that occasionally reached concentrations that could have caused transitory health effects among sensitive populations, such as irritation to the eyes, nose, throat, and respiratory tract. Substances of concern were NH3, H2S, methylamine, and acetaldehyde, and only the highest sampling results reached levels of potential concern. Some data-quality concerns were noted for the sampling data. PM2.5 concentrations also reached levels of potential health concern on a few sampling dates and when winds blew from the direction of the landfill, but other emission sources also contributed to the airborne levels. | Arunachalam et al., 2019 [21] |

| 6 | 1979 | Active | 34 | Phosgene, mercury, and combustion byproducts, VOCs including benzene, 1,2,4-Trichloropropane; Chlorobenzene; Acetaldehyde, and metals (e.g., Ni, Hg, As). | The landfill primarily accepts municipal solid waste, but also accepts C&D debris and industrial waste. The ATSDR became involved with the site after residents voiced concern about air emissions from an underground landfill fire, which had been burning for at least several months, according to multiple accounts. The landfill also experienced an aboveground fire in a pile of tires, and the landfill previously had a “burn pit” and “smolder pit” on its property. The nearest residents were approximately 500 feet from the landfill’s active section. Air samples collected on the landfill found concentrations of phosgene and mercury at levels of potential health concern. Elevated levels of several aldehydes were also noted. The public health hazard reported in the PHA was attributed to the combined effect of such respiratory irritants as smoke, various aldehydes, phosgene, and mercury vapor. The principal recommendation made in the PHA was to extinguish the underground landfill fire that was believed to contribute to the public health hazard. | Langmann et al., 1998 [22] |

| Site | Year Disposal Began | Operational Status | Acres | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1974 | Closed | 10 | This unlined landfill, an NPL * site, primarily accepted municipal solid waste, but also received non-hazardous industrial waste (e.g., oily sludge, metal grindings). Soil gas sampling occurred at various onsite locations, with methane concentrations in one portion of the landfill near the main office ranging from 10 to 90 percent. The HC † refers to an “elevated gas measurement near the landfill office” but does not document the observed methane level. The HC concluded that the potential migration of methane to the landfill office may present a public health hazard. The landfill evidently did not have a landfill gas-collection system at the time the ATSDR ‡ evaluated the site. | Morse et al., 2008 [23] |

| 2 | 1920 | Closed | 13 | This unlined landfill accepted municipal, commercial, and industrial waste for nearly 50 years. The landfill area was then covered with clean fill and developed for commercial, residential, and industrial uses, with no landfill gas-collection system in place. At three commercial properties built atop the former landfill, indoor air concentrations of methane exceeded the lower explosive limit (LEL) §, and occupants raised concerns that landfill gas was entering through foundation cracks and could be ignited. Multiple actions were taken to address this physical hazard: buildings were equipped with continuous methane monitors to detect atmospheric concerns; cracks in building foundations were identified and sealed; and passive vents were installed at multiple landfill locations to release landfill gas into the ambient air. | Pestana et al., 1995; McRae 2005; Rusnak et al., 2006 [24,25,26] |

| 3 | 1963 | Closed | 49 | This unlined landfill, an NPL site, previously accepted municipal solid waste, C&D debris, and sludge. Multiple residential and commercial properties are located immediately north of the landfill boundary. Even though steps had been taken to reduce the migration of landfill gases, methane concentrations in a floor drain in one of the affected buildings exceeded the LEL on 9 out of 12 sampling days in the late 1990s. Elevated methane levels were also observed in the building floor cracks and sumps. The ATSDR concluded that the observed methane levels in the affected buildings were an urgent public health hazard and recommended that actions be implemented to monitor indoor methane levels, to reduce the methane levels to below 10 percent of the LEL, and to prepare occupants for evacuation if methane levels continue to exceed 10 percent of the LEL. | Baughman et al., 1997; Baughman et al., 1998; Baughman et al., 2004 [27,28,29] |

| 4 | 1975 | Closed | 62 | Although originally approved as a “private sanitary landfill,” this unlined landfill accepted a wide range of waste (including hazardous waste) for nearly 25 years, until the landfill ceased operating. Passive vents were installed with the intent of collecting landfill gas for reuse, but the project was not completed, and the gas was vented into ambient air without flaring. The methane concentrations at the landfill, an NPL site, were high enough to trigger alarms on the explosimeters used by state agency staff who visited the site. The PHA did not document the methane concentration that triggered the alarms, though many of these meters are typically set to alarm when flammable gas levels exceed 10 percent of the LEL. The methane released from the onsite vents was deemed a public health hazard due to the possibility of trespassers or site visitors encountering flammable atmospheres and the lack of warning signs. | Jackson et al., 2012 [30] |

| 5 | 1968 | Closed | 145 | The unlined landfill, an NPL site, received municipal solid waste from multiple municipalities for at least 7 years. The landfill was not equipped with a landfill gas-collection system. Methane was detected in soil gas samples at the landfill and its perimeter, but the measured concentrations were not reported in the PHA. The document concluded that the methane gas detections at the site presented a potential explosive hazard. | Smith et al., 1995 [31] |

| 6 | 1963 | Closed | 108 | This landfill, an NPL site, received municipal and commercial solid waste for 27 years. The landfill included two disposal cells: one lined and the other unlined. While the landfill was still operating, elevated methane concentrations were measured in the basements of two homes, both located less than 100 feet from the site boundary. The local city eventually purchased the homes because the indoor methane concentrations had reached “explosive levels.” Following these events, a landfill gas-collection system was installed and continuously operated to prevent further migration of methane gases. Routine soil gas monitoring has demonstrated the system’s effectiveness. The ATSDR concluded that the site presented a past public health hazard due to the migration of methane gas to nearby households and recommended that the performance of the landfill gas-collection system be continuously monitored to ensure methane gas does not migrate offsite at unsafe levels in the future. | Crua et al., 1996 [32] |

| 7 | 1947 | Closed | 34 | This unlined landfill, an NPL site, received municipal, commercial, and industrial waste for more than 40 years before closure. Two studies (a soil gas survey and a methane migration study) examined the potential for methane gas to migrate offsite at explosive levels. The soil gas survey identified four methane “hot spots” at the landfill, and the migration study reported elevated methane concentrations at a neighboring property. Another study detected methane concentrations above the LEL on three different occasions at a location outside of the landfill property. These observations contributed to the finding of a potential explosion hazard. Proposed remediation measures for the landfill were to include monitoring and controlling methane migration, but further details on the specific remediation measures were not specified. | Raffert et al., 1995 [33] |

| 8 | 1974 | Closed | 113 | This unlined landfill, an NPL site, primarily received municipal solid waste for 23 years. Migration of landfill gas to offsite locations was extensively documented. Methane concentrations greater than the LEL were measured in several homes within 100 to 500 feet of the landfill, and methane concentrations greater than 50 percent of the LEL were measured in buildings in a nearby industrial park. The elevated methane concentrations caused “furnace puff-backs” at several homes, indicating explosive levels of methane. Concern about methane migration heightened in the winter months when surface soils were often frozen. The landfill operators eventually installed a series of active and passive gas vents, some of which became part of the “landfill perimeter gas-collection system.” The ATSDR recommended development of an operations and maintenance plan for the collection system, given its critical role in ensuring landfill gas does not cause unsafe methane accumulations in offsite structures. | Schuck et al., 1995 [34] |

| 9 | 1966 | Closed | 100 | This NPL site comprises multiple former quarries that were used for disposal of municipal, commercial, and industrial solid waste over a 23-year period starting in 1966. Soil gas samples were collected around the perimeter of the landfill, and methane concentrations exceeded the LEL at multiple locations, including within 200 feet of high-density residential areas. Methane soil gas concentrations above the LEL at the landfill perimeter were confirmed in multiple rounds of additional sampling. These observations led to a conclusion of a public health hazard, which was to be addressed through several actions. These include the installation of a network of passive vents around the landfill perimeter and the operation of combustible gas monitors inside the homes nearest to the landfill. | ODH and ATSDR 1998 [35] |

| 10 | 1972 | Closed | 4 | This unfenced and unlined open dump accepted municipal and industrial waste for 6 months. The waste was eventually covered with soil, but no access restrictions were in place, and a home was being built atop a former disposal area at the time the site was assessed. Gas-monitoring probes placed around the perimeter of the landfill found methane concentrations above the LEL at two locations. Subsequently, monthly monitoring of landfill gas had multiple measurements of methane gas above the LEL and additional measurements marginally below the LEL. Methane concentrations also exceeded the LEL at a crack in the dump surface. The HC conclusion was that the site presented a future public health hazard due to the risk of explosion, should methane gases accumulate in the crawl space of the home that was under construction. | Shelley et al., 2004 [36] |

| 11 | 1970 | Closed | 80 | This unlined landfill, an NPL site, received municipal and industrial waste for 5 years before being closed. Following the detection of methane gas in a groundwater monitoring well, a soil gas-monitoring network was deployed to determine the nature and extent of methane migration away from the landfill property. At four soil gas-monitoring sites along the site perimeter, methane concentrations exceeded the LEL on multiple occasions. Methane gas monitoring in nearby homes (all within 500 feet of the site) had not found elevated concentrations, but the site was considered a physical hazard due to the potential for further gas migration to occur. | Nehls-Lowe et al., 1994 [37] |

| 12 | 1952 | Closed | 27 | For 30 years, this unlined dump, an NPL site, received municipal, industrial, and C&D waste. During site investigations, elevated methane concentrations were detected at a monitoring well. A comprehensive methane survey followed, in which soil gas methane concentrations above the LEL were identified in multiple onsite areas, including under an onsite building. The nearest homes (approximately 1000 feet from the dump) were also monitored for methane gas, but the measured concentrations were not elevated. The document concluded that the potential buildup of methane gas beneath structures at the dump was an explosion hazard. | Goldrina et al., 1994 [38] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muianga, C.; Wilhelmi, J.; Przybyla, J.; Smith, M.; Zarus, G.M. Lessons Learned from Air Quality Assessments in Communities Living near Municipal Solid Waste Landfills. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111732

Muianga C, Wilhelmi J, Przybyla J, Smith M, Zarus GM. Lessons Learned from Air Quality Assessments in Communities Living near Municipal Solid Waste Landfills. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111732

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuianga, Custodio, John Wilhelmi, Jennifer Przybyla, Melissa Smith, and Gregory M. Zarus. 2025. "Lessons Learned from Air Quality Assessments in Communities Living near Municipal Solid Waste Landfills" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111732

APA StyleMuianga, C., Wilhelmi, J., Przybyla, J., Smith, M., & Zarus, G. M. (2025). Lessons Learned from Air Quality Assessments in Communities Living near Municipal Solid Waste Landfills. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111732