Abstract

Unintended pregnancies among adolescent and young women in low- and middle-income countries pose major public health challenges, underscoring the need for improved access to modern contraceptives. This study examined prevalence, preferences, and correlates of modern contraceptive use among young women living in urban slums of Kampala, Uganda, to inform targeted interventions. We analyzed baseline data from The Onward Project On Wellbeing and Adversity (TOPOWA), an NIH-funded, multi-component prospective cohort study on mental health among women aged 18–24 years. In 2023, 300 participants were recruited from three sites (Banda, Bwaise, Makindye). Interviewer-administered surveys assessed contraceptive choices, lifestyle, and demographic factors. Modified Poisson regression was used to examine correlates of contraceptive use. Among participants, 66.0% had ever used contraception, 40.0% were current users, and 38.0% reported modern contraceptive use. Multivariable analyses showed that having a consistent partner (PR = 3.28; 95% CI: 1.90–5.67), engaging in sex work (PR = 2.10; 95% CI: 1.46–3.02), older age (PR = 1.08; 95% CI: 1.01–1.16), and having children (PR = 1.72; 95% CI: 1.12–2.66) were associated with higher modern contraceptive use. Findings highlight important gaps in sustained contraceptive use and the need for tailored interventions addressing economic, social, and educational barriers to improve reproductive health in this low-resource setting.

Keywords:

contraceptive use; women’s health; sexual and reproductive health; urban; Kampala; Uganda; Africa 1. Introduction

Unintended adolescent pregnancies remain high in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with about half ending in unsafe termination [1]. Adolescent fertility and birth rates, however, continue to be elevated in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Caribbean regions compared to the rest of the world [1,2]. In Africa, the pooled prevalence of adolescent pregnancy is estimated at 19%, being highest in East Africa [3,4], while unintended pregnancy is 30% [5]. Adolescent pregnancies have been associated with adverse outcomes, including eclampsia, fistula, and unsafe abortions, leading to an increase in maternal death [1]. Modern contraceptive use among adolescent girls has been shown to reduce unintended pregnancies and their consequences. However, the prevalence and correlates of preferential use of these methods are not well reported in vulnerable groups and may represent a range of individual, community, and structural factors [3,4,6]. Modern contraceptive methods typically include implants, sterilization, injectables, oral contraceptive pills, intra-uterine device (IUD), condoms, diaphragm, cervical cap, spermicides, Lactational amenorrhea (LAM), vaginal ring, contraception patch, and emergency contraceptive pills [7].

The pooled prevalence of modern contraceptive use is estimated at 24.7% among adolescent girls, 15–19 years, across several countries in Africa [8] but varies substantially by country: 4% in South Sudan, 12.8% in Guinea, 17% in Rwanda, and 52% in Eswatini and Namibia [9,10,11]. In Uganda, the percentage of women of reproductive age using any family planning method is 32.9%, while the percentage using modern contraceptive methods is 29.8% [12], with some estimates suggesting it could be as high as 45% [13]. This prevalence similarly varies significantly by region and population, ranging from 7% in the Karamoja region to 43% in the Eastern region–Kampala at 39% and from 35.2% among women in fishing communities to 61.5% among postpartum teenage mothers in Eastern Uganda [14,15,16,17,18]. Nonetheless, we could not find any study that assesses current modern contraceptive use rates among vulnerable young women in the urban slums of Kampala.

Short-acting contraceptive methods like condoms, oral pills, and injectables are more frequently used than long-acting contraceptive methods like intra-uterine devices (IUDs) and implants in much of Sub-Saharan Africa [15,19,20,21,22,23,24]. The choice of a contraceptive method is influenced by availability and individual knowledge of the available options, which, in some way, is partly determined by their literacy levels. Studies in DRC, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Burundi showed that women with at least secondary education are more likely to use modern contraception compared to women with lower education [25,26,27,28]. Similarly, in Uganda, married women are more likely to use modern contraception if they or their partners have completed at least secondary education [13,20]. The fear of side effects that comes with using certain methods is another factor that negatively influences modern contraceptive use. A study conducted in Blantyre–Malawi found that women who feared side effects were 3 times more likely to report the unmet need for modern contraception [29]. Similar concerns have been reported in Zambia [30], Nigeria [31], and Uganda [14]. Urban young women living in poverty in Kampala slums are often unable to afford and access education, contraceptive information, or quality healthcare service [32], yet little is known about their modern contraceptive use.

Socio-cultural norms in many settings across sub–Saharan Africa also bar adolescents from accessing modern contraceptive services. A qualitative study conducted in Uganda revealed that parents and guardians perceived the modern contraceptive use by adolescents as promoting sexual promiscuity and as unacceptable to cultural, religious, and moral norms [33]. This is in line with other findings in Kenya [34] and Uganda [35]. Further, religious affiliation, such as identifying as Muslim, has been associated with lower levels of modern contraceptive use [8,13,36]. In Kenya, gender-based violence and family conflicts have been cited as consequences of covert modern contraceptive use [37], and the repercussions, as predicted, included inconsistencies, unreliability, lack of social and financial support, and social sanctioning as female disobedience [38,39]. Urban vulnerable adolescents and young women are not exempt from these hardships in accessing modern contraceptives, yet remain understudied.

Engaging in multiple sexual encounters, as with transactional sex or married/cohabiting couples, increases the likelihood of modern contraceptive use [40,41]. However, in contrast, adolescents engaged in such sexual relationships often suffer intimate partner violence (IPV) [42], which lessens their probability of using modern contraception when they want to [29,37,43]. While vulnerable young women living in urban slums are predisposed to sexual activity and IPV earlier in life [44,45], modern contraceptive use in this population is still unclear.

Among other factors that influence modern contraceptive use is access to sexual reproductive health information and services. Lack of youth-friendly reproductive health services at public facilities is a major barrier to modern contraceptive use, prompting young women to seek services from private healthcare providers who may be less equipped [37,46,47,48]. A study in Uganda revealed that 40% of healthcare facilities in informal settlements offered contraceptives, mostly privately owned. Only a third provided at least one long-acting method, and 25% did not offer contraceptives to unmarried adolescents [49]. Incentivized modern contraceptive use has been shown to significantly increase family planning uptake among poor urban communities; however, this has not yet been implemented widely [50]. Additionally, women exposed to mass media such as radio and TV showed higher levels of modern contraceptive use [21,31].

There is a dearth of knowledge on the prevalence and preference of modern contraceptive use and the associated factors among vulnerable young women living in urban slums of Kampala, Uganda. To understand the factors influencing young women’s choice of contraception, it is essential to consider individual, social, community, and structural factors that may affect their access to modern contraceptive methods. This is particularly the case for young women living in poverty, where there are high levels of stress and depressive symptoms [51], where access to healthcare and education can be limited, and where survival sex and IPV levels tend to be high [44,52]. It is within this context that this current study sought to address the research question: What is the prevalence, preference, and correlates of modern contraceptive use among young women living in poverty in Kampala, Uganda? We were particularly interested in examining those factors well established in previous research, such as demographic characteristics, as well as other psychosocial health factors, such as HIV testing, having a partner, and engaging in sex work. However, we also wanted to determine if current alcohol use, IPV, and psychological distress may be associated with modern contraceptive use. Our previous research with young women in Kampala indicated that alcohol use during sex was strongly associated with pregnancy [32]. Similarly, IPV and associated distress also seem to impact contraceptive use [29,37,43]. As such, we will include these factors in our analysis to determine if they are associated with modern contraceptive use. By examining these diverse factors, we can better identify the barriers and facilitators to modern contraceptive use in this population and develop targeted interventions to improve access and informed reproductive choices.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Participants

Between July 2023 and November 2023, we enrolled 300 young women to participate in a prospective observational multi-component cohort study across three sites in Kampala (i.e., Banda, Bwaise, and Makindye) to examine the mechanistic pathways of mental illness (TOPOWA study). Details of the study have been described previously [53,54]. The target population for the TOPOWA cohort study was those aged 18 to 24 who self-reported as female, lived within a radius of 2 km from the Uganda Youth Development Link (UYDEL) vocational training centers, and had attained a minimum of primary five education level. Those who self-reported current pregnancy, had significant intellectual disability, severe mental illness, or substance use requiring hospitalization were excluded from the study. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants, guided by local leaders until the sample size was reached. Among the 495 young women screened, 137 were not eligible for participation, and 58 did not turn up for study enrollment, making the participation rate 83% among those eligible. In this paper, we present analyses using the baseline data from the TOPOWA cohort study.

As part of the baseline assessment, participants were asked to complete an interviewer-administered survey containing a broad range of measures pertaining to demographic and psychosocial characteristics and life experiences, in addition to other study components. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Kennesaw State University, Makerere University School of Health Sciences (MaKSHS) Research and Ethics Committee (MAKSHSREC-2023-532) and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology, UNCST (HS2959ES). All participants provided written informed consent before taking part in the study. Participants also received remuneration for participating in the survey and the other data collection protocol components.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Contraceptive Use

During the baseline assessment, women were asked, “Have you ever used any contraceptives?” to measure lifetime contraceptive use. To assess current contraceptive use, women were asked, “What is your current method of birth control/family planning?”. Also, responses to the question were coded to form a binary variable: 0 (non-user or traditional contraceptive user) and 1 (modern contraceptive user) to determine the prevalence and women’s characteristics associated with modern contraceptive use. Modern contraceptive methods include implants, sterilization, injectables, oral contraceptive pills, intra-uterine device (IUD), condoms, diaphragm, cervical cap, spermicides, Lactational amenorrhea (LAM; infant less than 6 months old, menstruation has not returned, and exclusively breast feeding), vaginal ring, contraception patch, emergency contraceptive pills and traditional methods include withdrawal, fertility awareness, and abstinence [7]. In addition, women were asked, “What is the reason for using this current method of birth control/family planning?” to assess the contraceptive preferences.

2.2.2. Demographic Characteristics

The survey also collected information that included age, education level, the living status of participants’ parents, and parenting status, among others. During analysis, we only included demographic characteristics relevant to the study objective.

To assess the women’s living standards, the wealth index—a routine measure of socioeconomic inequality [55]—was used in this study. The wealth index measure was derived from information on household assets and characteristics (e.g., television, bicycles, cows, and poultry) collected using the baseline financial stressors survey. Factor analysis, one of the methods for constructing the wealth index [56], was applied, and data were all coded as binary indicator variables.

Inequality in modern contraceptive use was assessed using (i) wealth categorized as low and high, (ii) level of education attained (primary or lower, some secondary or higher), and other characteristics.

2.2.3. Psychological Distress

A later version (K6) [57] of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) [58] was used to assess distress in this study. The scale collected information on respondents’ past month’s experience of six symptoms: nervousness, hopelessness, restlessness or fidgetiness, severe depression, difficulty, and worthlessness. The responses were rated as 0 (none of the time), 1 (a little of the time), 2 (some of the time), 3 (most of the time), and 4 (all of the time). The sum score was obtained by summing up all scores, excluding items with missing values. The score ranged from 0 to 24, and a higher score indicated higher psychological distress. A score of 13 or higher suggested nonspecific severe psychological distress [59]. The scale’s internal consistency was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.80).

2.2.4. Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

We used 13 items of the WHO violence against women tool [60] with three constructs: psychological, physical, and sexual violence. Respondents were asked whether their current husband/partner, or any other partner, ever insulted or made them feel bad about themselves, physically forced them to have sexual intercourse when they did not want to. Responses were “yes” or “no”. In this study, a woman was categorized as having ever experienced IPV if they agreed to any of the questions.

For the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, the adjusted weighted person-mean imputation approach was used to handle any item-level missingness. Since surveys were administered by certified research assistants, missing data was minimal. Overall, only one participant’s item was missing; hence, the missing item was replaced using a weighted person-mean imputation method, ensuring that individual scores accurately reflected the intended scale total structure while maintaining the reliability of the data.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics, used to describe the study population, were presented by frequencies and percentages, while the prevalence of modern contraceptive use was presented using proportions by categories of demographic characteristics and other variables deemed to be associated with modern contraceptive use according to previous studies.

To assess inequality in modern contraceptive use by wealth and education level, we used predicted probabilities derived from regression models for binary outcomes [61]. For example, to assess the impact of education on modern contraceptive use, we compared the expected probabilities of modern contraceptive use for a woman with primary or lower education and a woman with some secondary or higher education who were the same age. Women’s age, education, and socioeconomic status (measured by wealth index) were considered during this analysis as they are common predictors of modern contraceptive use in Uganda [62,63] and other sub-Saharan African countries [64].

A modified Poisson model approach, useful for estimating relative risk by combining a log Poisson regression model with robust variance estimation [65], was applied to assess factors associated with modern contraceptive use. The primary outcome was modern contraceptive use coded 1 (current modern contraceptive users) and 0 (otherwise). Also, a consistent sex partner was defined as any person the participant regularly engaged in sexual intercourse with: boyfriend/husband/sex client. Instead of the odds ratio, we estimated the prevalence ratio to measure the associations since the prevalence of the study outcome was greater than 10% (common outcome); hence, the odds ratios would have considerably overestimated the strength of the association [66]. To identify factors associated with modern contraceptive use, variables with strong theoretical importance and those that were significant at bivariate analysis were added to the multivariable regression model. Multicollinearity was tested using Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) at a cut point of 10 [67]. Although the VIF for age was slightly above 10, it was retained due to its strong theoretical importance as a primary predictor of contraceptive use. In addition, comparing standard errors across models with and without age revealed negligible differences, indicating that the level of multicollinearity for age was tolerable [68].

Stata 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all analyses, and the statistical significance was set a priori at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

Of the 300 women study participants, most had attained some secondary or higher level of education (66.0%) and had children (62.0%). The majority of the women did not live together with their parents (66.3%) and had ever tested for HIV (90.3%). Details of these results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Women participants’ demographic characteristics in the baseline assessment of the TOPOWA study (N = 300).

3.2. Contraceptive Use Prevalence and Methods

In terms of contraceptive use, 198 of the 300 women (66.0%) had ever used any contraceptive method in their lifetime. The prevalence of overall current contraceptive use was 40.0%, while that of current modern contraceptive use was 38.0%.

The prevalence of current modern contraceptive use by reproductive health characteristics, wealth index, IPV, psychological distress, past-month alcohol use, and demographic characteristics is presented in Table 2. The overall current modern contraceptive use was 38.0% (95% CI: 32.7–43.6). The current modern contraceptive use varied significantly by having a consistent partner, age, having children, engaging in sex work, past-month drinking, IPV, HIV testing, household size, and living with parents. Modern contraceptive use was highest among women with consistent partners 51.8% (95% CI: 44.8–58.7), who were between 21 and 24 years of age 49.4% (95% CI: 41.6–57.2), who had children 51.6% (95% CI: 44.4–58.7), and who were engaged in sex work 90.9% (95% CI: 55.9–98.7). Modern contraceptive use was also more prevalent among women who drank alcohol in the past month 54.4% (95% CI: 42.5–65.8), had experienced any IPV 47.3% (95% CI: 39.8–53.2), had ever tested for HIV 41.3% (95% CI: 35.6–47.3), were living in households with four or fewer members 47.9% (95% CI: 40.5–55.5) and were not living with their parents 47.9% (95% CI: 40.9–55.0).

Table 2.

Prevalence of modern contraceptive use by women’s characteristics in the baseline assessment of the TOPOWA study (N = 300).

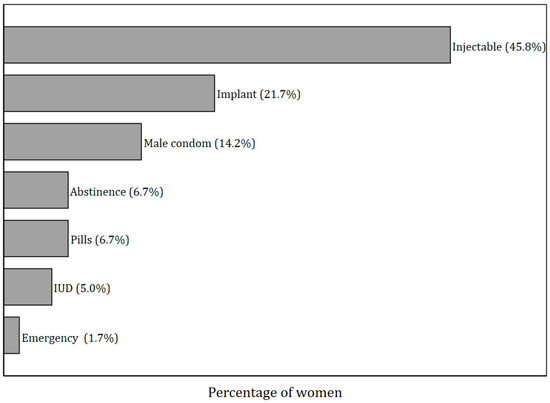

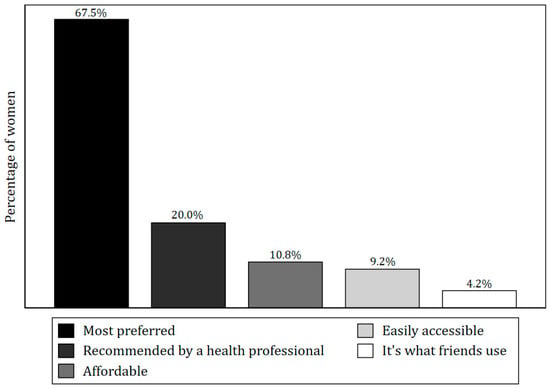

The most frequently reported contraceptive method was injectables, as reported by 45.8% of all current contraceptive users, followed by implants (21.7%), while the least popular method was emergency contraceptive pills (1.7%) (Figure 1). The predominant reason for the choice of the current contraceptive method was user preference (67.5%) as indicated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Contraceptive use methods at the baseline assessment of the TOPOWA study among women who reported any current contraceptive use (n = 120).

Figure 2.

Reasons for using the contraceptive method as reported by women in the TOPOWA baseline assessment who were currently using any contraceptives (n = 120).

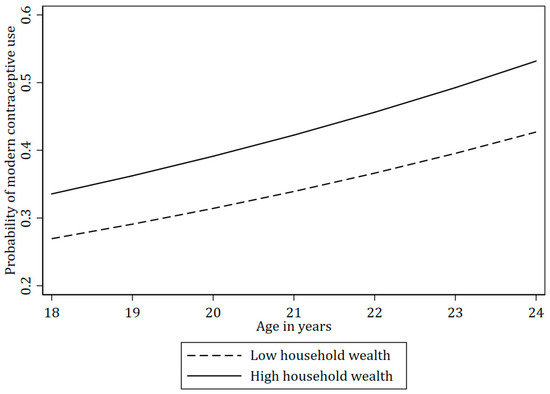

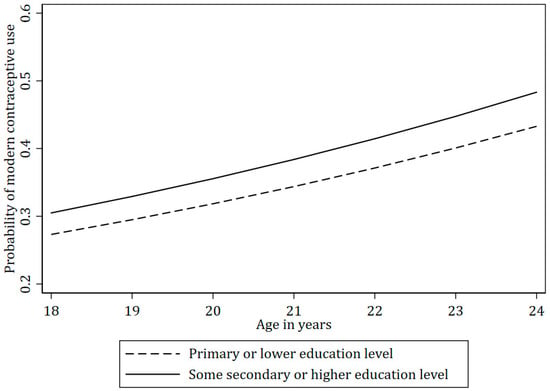

3.3. Modern Contraceptive Use Inequality by Wealth and Education Level

The expected probability of using modern contraceptives was generally higher among the participants who were 20 years and older (Table 3). Moreover, women from wealthier households were more likely to use contraceptives than those with lower incomes (Figure 3). Women who had attained higher education (i.e., some secondary or higher) were more likely to use contraceptives than those who had primary or lower level of education (Figure 4).

Table 3.

Modern contraceptive use by marginal probability estimates of wealth index and education levels by age in the baseline assessment of the TOPOWA study (N = 300).

Figure 3.

The probability of modern contraceptive use by household wealth index across age in the TOPOWA Baseline Assessment (N = 300).

Figure 4.

The probability of modern contraceptive use by education level across age among women in the TOPOWA study (N = 300).

3.4. Factors Associated with Modern Contraceptive Use

Results from the multivariable regression model (Table 4) indicate that, holding other variables constant, having a consistent partner was associated with higher modern contraceptive use (Prevalence ratio, PR = 3.28; 95% confidence interval, CI: 1.90–5.67). Engaging in sex work (PR = 2.10; 95% CI: 1.46–3.02), older age (PR = 1.08; 95% CI: 1.01–1.16), and having children (PR = 1.72; 95% CI: 1.12–2.66) were also significantly associated with modern contraceptives use, other variables held constant.

Table 4.

Adjusted prevalence ratios for the association between modern contraceptive use and women’s characteristics in the baseline assessment of the TOPOWA study (N = 300).

4. Discussion

In this study we sought to determine the prevalence and associated characteristics of modern contraceptive use among young women living in poverty in Kampala. Our findings provide valuable insights for planning sexual and reproductive health services for this population to prevent unwanted pregnancies, support family planning, and prevent sexually transmitted diseases.

The overall prevalence of lifetime contraceptive use among the women in the TOPOWA study was relatively high, with 66% having used any contraceptives at some point, comparable to 62% from a study among reproductive-age women in the urban areas of Ethiopia [69]. However, the prevalence of current contraceptive use was considerably lower at 40%, suggesting gaps in ongoing access or sustained use of contraceptives among the women in our study. This finding was slightly higher compared to 33.4% from the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (UDHS) among the 20–24-year-olds [12] and 32% from a national household survey in a broader age range of 15–24-year-olds in Ghana [22]. Our estimates likely reflect that the women in this study may have increased exposure to contraception knowledge and usage in the urban settings, as reflected in the 2022 UDHS report. The prevalence of modern contraceptive use in our study (38%) is comparable to findings from other studies in sub-Saharan Africa [70,71,72] and much higher in contrast to the 9% among 15–19-year-old females in Uganda’s general population [73], suggesting probable easier access to modern contraception in urban areas than the rural areas. We also found that the most frequently used of the modern methods was injectable contraception, followed by implants, highlighting a probable preference for long-acting reversible contraceptives. This preference aligns with findings from other studies in similar settings [47,70,74,75] where convenience and efficacy of reversible contraceptives drive their popularity. The low use of emergency contraceptives among the study population suggests a potential lack of access to this method, perhaps due to the cost of the contraceptive and other sociocultural factors, or it may reflect a preference for more regular or sustained contraceptive methods to prevent unintended pregnancies [76,77,78]. We did not, however, include questions that enable us to provide additional context or information about the factors that may impact the use of emergency contraceptives.

Our findings also indicate significant disparities in the expected probability of modern contraceptive use based on socioeconomic status. Women with higher living standards in our study, albeit still living in the urban slums, were more likely to use modern contraceptives, which may be attributed to better access to healthcare services, higher health literacy, and perhaps the financial means to afford contraceptives [8,79]. Similarly, women with secondary or higher education were more likely to use modern contraceptives compared to those with less education. Education likely equips women with the knowledge and autonomy to make informed reproductive health decisions, and it may also correlate with greater empowerment and access to resources [25,26,80]. Unemployment and low education levels are often linked to economic hardship and limited access to healthcare, further exacerbating disparities in contraceptive use [63,81].

Our findings also identified several factors significantly associated with modern contraceptive use, including having a consistent partner, sex work, age, and having children. Women with consistent partners were more likely to use modern contraceptives, possibly due to stable relationship dynamics that facilitate discussions about family planning. Also, the women reporting sex work or survival sex were also more likely to report modern contraceptive use, which may also represent an opportunity for integrated care to address both unwanted pregnancies and the prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections [82,83]. Intriguingly and perhaps due to the small sample size, HIV testing was not statistically significant in the multivariable analysis.

Age, even with the narrow range (18–24) of our sample population, also played a significant role, with women over the age of 20 generally more likely to use modern contraceptives. This suggests that younger women may face barriers or lack the necessary knowledge and support for contraceptive use [84]. Moreover, women who are a few years older may be more knowledgeable about contraceptives compared to those slightly younger [15]. Having children was also strongly associated with contraceptive use, likely reflecting a desire to space or limit births. Without statistically controlling for other factors, our findings show that women in smaller households were more likely to use contraceptives, possibly indicating that those with more means live in smaller households and perhaps that household crowding and economic constraints influence family planning decisions [8,72]. Also, IPV of any form was associated with modern contraceptive use only in the bivariate analyses, not in the multivariate models. However, there may be other factors not examined in this study that may influence modern contraceptive use. Previous research has indicated that women may lack autonomy and empowerment regarding their own health issues and decision-making regarding pregnancy, when engaged in a sexual relationship, which reflects relatively common sociocultural norms across African societies [85,86]. This is a key research question for future research, but it would require a larger sample size of women.

The findings from this study have important implications for public health strategies and policies aimed at improving contraceptive access and use among women in low-resource settings. Efforts to promote contraceptive use should focus on increasing accessibility, particularly among younger women, those from lower wealth index, and those who have received less education. Education and community outreach programs that enhance awareness of various contraceptive methods and their benefits could empower women to make informed reproductive health decisions. Moreover, integrating family planning services with other sexual health services may provide a holistic approach to women’s health and encourage contraceptive use, which may be particularly important for women engaged in sex work [87,88]. Additionally, addressing socio-economic barriers by providing subsidized or free contraceptives at private sector clinics could also help bridge the gap in contraceptive use among different groups. Previous research has raised these issues, outlining the importance of socioeconomic status, living in an urban area, age, number of children, and employment in the selection and choice of contraception among adolescent girls and young women [89,90,91].

We also found that past-month alcohol use was associated with contraceptive use in bivariable analyses but not in multivariable analyses. In previous research of young women living in Kampala, alcohol use during sex was the key correlate for pregnancy [32]. Accordingly, alcohol-related condomless sex may be an important factor [92] that should be considered in terms of the prevention of pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. While the literature regarding alcohol use and sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV [45,93,94], is growing, there is less research on alcohol and its association with contraceptive use and pregnancy, and that is also important to consider for future research. Similarly, IPV and HIV testing were associated with contraceptive use in bivariable analyses but not in adjusted models, suggesting that the effects are largely mediated through relational and structural factors such as partner consistency, sex work, and childbearing, which together shape women’s reproductive autonomy. This is particularly relevant given the intersectional factors impacting these women and the prevalence of survival sex [44] and the intersection of alcohol use, violence, and HIV, which is highly relevant to contraceptive use and pregnancy [45].

There are several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the results presented in this paper are based on cross-sectional baseline data analysis of the TOPOWA cohort study; as such, causal or temporal relationships cannot be inferred. Second, the choice of the current contraceptive method may or may not translate into preference. The relationship between these two factors was not assessed. Further, we did not assess how often or how long the selected method represents the extent of modern contraceptive use. Third, the TOPOWA study excluded women who knew they were pregnant at the time of participant enrollment, likely biasing the findings toward a higher prevalence of contraceptive use among the study participants than in broader population samples, as noted in the comparison with household surveys. Excluding pregnant women was important since other TOPOWA study components required the collection of biomarkers, including saliva samples, which are directly impacted by pregnancy. Moreover, we excluded women who were severely impacted by mental illness or substance use and required hospitalization, given their inability to participate in a community study. The implication of that exclusion on the study findings and contraceptive use specifically is unknown.

Fourth, in analysis, we classify periodic abstinence among traditional methods of contraception, as is the case with UNDESA [7]. This may affect the comparability of our results with other studies that do not classify periodic abstinence as a contraceptive method. Lastly, due to a few numbers of events per predictor, the model might not detect small effects. These factors may have impacted the findings in unknown ways and reduced the generalizability of the study findings to this target population. It is also worth noting that some subgroups, such as women who reported engaging in sex work, had relatively small sample sizes, leading to wide confidence intervals. Hence, such findings should be interpreted with caution.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the importance of understanding the demographic and socio-economic factors influencing contraceptive use among women. Addressing disparities in contraceptive access and use requires targeted interventions that consider socioeconomic status, relationship dynamics, and other contextual factors. By improving access to contraceptives and empowering women with the knowledge and resources to make informed choices, we can enhance reproductive health outcomes and promote greater health equity [95]. These findings contribute to the limited body of evidence on contraceptive use among young women living in urban informal settlements in sub-Saharan Africa, where social drivers, gendered norms, and structural inequities continue to shape reproductive decision-making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.S.; methodology, M.H.S. and J.P.; formal analysis, C.N.; investigation, J.P. and A.N.; resources, A.N.; data curation, G.M. and C.N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.N.; writing—review and editing, M.H.S., J.N., G.M., C.N., J.P., A.N. and H.K.; visualization, C.N.; supervision, M.H.S., G.M. and J.P.; funding acquisition, M.H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health, grant number R01MH128930. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approvals were obtained from Kennesaw State University, the Makerere University School of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (MAKSHSREC-2023-532, dated 2 June 2023), and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (Registration number HS2959ES).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study will become available upon the completion of the cohort study.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to our community-based partner, the Uganda Youth Development Link, for their engagement and to the entire data collection team. We are also very grateful to our study participants who contribute their lived experiences to support this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| IPV | Intimate Partner Violence |

| IUD | Intra-Uterine Device |

| MaKSHS | Makerere University School of Health Sciences |

| LAM | Lactation Amenorrhea Method |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| PR | Prevalence Ratio |

| TOPOWA | The Onward Project On Wellbeing and Adversity |

| UYDEL | Uganda Youth Development Link |

References

- World Health Organisation. Adolescent Pregnancy. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- UNFPA. Adolescents and Youth Dashboard—Uganda|United Nations Population Fund. 2024. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/data/adolescent-youth/UG (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Kassa, G.M.; Arowojolu, A.O.; Odukogbe, A.A.; Yalew, A.W. Prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy in Africa: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonen, E.G. Pooled prevalence and associated factors of teenage pregnancy among women aged 15 to 19 years in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from 2019 to 2022 demographic and health survey data. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2024, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayalew, H.G.; Liyew, A.M.; Tessema, Z.T.; Worku, M.G.; Tesema, G.A.; Alamneh, T.S.; Teshale, A.B.; Yeshaw, Y.; Alem, A.Z. Prevalence and factors associated with unintended pregnancy among adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa, a multilevel analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wado, Y.D.; Gurmu, E.; Tilahun, T.; Bangha, M. Contextual influences on the choice of long-acting reversible and permanent contraception in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Contraceptive Use 2024 and Estimates and Projections of Family Planning Indicators 2024. Methodology Report. POP/DB/CP/Rev2024 and POP/DB/FP/Rev2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2024_methodology-report_world_contraceptive_use.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Ahinkorah, B.O. Predictors of modern contraceptive use among adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa: A mixed effects multilevel analysis of data from 29 demographic and health surveys. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2020, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidibé, S.; Delamou, A.; Camara, B.S.; Dioubaté, N.; Manet, H.; El Ayadi, A.M.; Benova, L.; Kouanda, S. Trends in contraceptive use, unmet need and associated factors of modern contraceptive use among urban adolescents and young women in Guinea. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawuki, J.; Gatasi, G.; Sserwanja, Q.; Mukunya, D.; Musaba, M.W. Utilisation of modern contraceptives by sexually active adolescent girls in Rwanda: A nationwide cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahinkorah, B.O. Predictors of unmet need for contraception among adolescent girls and young women in selected high fertility countries in sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel mixed effects analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistcs. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2022; UBOS: Kampala, Uganda, 2023.

- Wasswa, R.; Kabagenyi, A.; Ariho, P. Multilevel mixed effects analysis of individual and community level factors associated with modern contraceptive use among married women in Uganda. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanvubya, A.; Ssempiira, J.; Mpendo, J.; Ssetaala, A.; Nalutaaya, A.; Wambuzi, M.; Kitandwe, P.; Bagaya, B.S.; Welsh, S.; Asiimwe, S.; et al. Use of Modern Family Planning Methods in Fishing Communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UBOS; ICF. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016; Uganda Bureau of Statistics: Kampala, Uganda, 2018.

- Muyama, D.L.; Musaba, M.W.; Opito, R.; Soita, D.J.; Wandabwa, J.N.; Amongin, D. Determinants of Postpartum Contraception Use Among Teenage Mothers in Eastern Uganda: A Cross-Sectional Study. Open Access J. Contracept. 2020, 11, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbabazi, L.; Nabaggala, M.S.; Kiwanuka, S.; Kiguli, J.; Laker, E.; Kiconco, A.; Okoboi, S.; Lamorde, M.; Castelnuovo, B. Factors associated with uptake of contraceptives among HIV positive women on dolutegravir based anti-retroviral treatment-a cross sectional survey in urban Uganda. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wambi, R.; Mujuzi, H.; Siya, A.; Maryhilda, C.C.; Ibanda, I.; Doreen, N.; Stanely, W. Factors influencing contraceptive utilisation among postpartum adolescent mothers: A cross sectional study at China-Uganda friendship hospital. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2024, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamau, R.K.; Karanja, J.; Sekadde-Kigondu, C.; Ruminjo, J.K.; Nichols, D.; Liku, J. Barriers to contraceptive use in Kenya. East Afr. Med. J. 1996, 73, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bakesiima, R.; Cleeve, A.; Larsson, E.; Tumwine, J.K.; Ndeezi, G.; Danielsson, K.G.; Nabirye, R.C.; Kashesya, J.B. Modern contraceptive use among female refugee adolescents in northern Uganda: Prevalence and associated factors. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birabwa, C.; Chemonges, D.; Tetui, M.; Baroudi, M.; Namatovu, F.; Akuze, J.; Makumbi, F.; Ssekamatte, T.; Atuyambe, L.; Hernandez, A.; et al. Knowledge and Information Exposure About Family Planning Among Women of Reproductive Age in Informal Settlements of Kira Municipality, Wakiso District, Uganda. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2021, 2, 650538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, S.C.; Otupiri, E.; Castillo, P.W.; Li, N.W.; Apenkwa, J.; Polis, C.B. Contraceptive and abortion practices of young Ghanaian women aged 15–24: Evidence from a nationally representative survey. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boadu, I. Coverage and determinants of modern contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa: Further analysis of demographic and health surveys. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, A.J.; Ogwal, M.; Doshi, R.H.; Kiyingi, H.; Sande, E.; Serwadda, D.; Musinguzi, G.; Standish, J.; Hladik, W. At the intersection of sexual and reproductive health and HIV services: Use of moderately effective family planning among female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, W.; Worku, A. Determinants of low family planning use and high unmet need in Butajira District, South Central Ethiopia. Reprod. Health 2011, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutaremwa, G.; Kabagenyi, A. Postpartum family planning utilization in Burundi and Rwanda: A comparative analysis of population based cross-sectional data. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2018, 30, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, S.E.; Gallagher, M.C.; Kakesa, J.; Kalyanpur, A.; Muselemu, J.-B.; Rafanoharana, R.V.; Spilotros, N. Contraceptive use among adolescent and young women in North and South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo: A cross-sectional population-based survey. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, S.D.; Sebastian, Y.; Yeneneh, A.; Chanie, A.F.; Melaku, M.S.; Walle, A.D. Prediction of contraceptive discontinuation among reproductive-age women in Ethiopia using Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2016 Dataset: A Machine Learning Approach. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2023, 23, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twizelimana, D.; Muula, A.S. Unmet contraceptive needs among female sex workers (FSWs) in semi urban Blantyre, Malawi. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chola, M.; Hlongwana, K.W.; Ginindza, T.G. Motivators and Influencers of Adolescent Girls’ Decision Making Regarding Contraceptive Use in Four Districts of Zambia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezenwaka, U.; Mbachu, C.; Ezumah, N.; Eze, I.; Agu, C.; Agu, I.; Onwujekwe, O. Exploring factors constraining utilization of contraceptive services among adolescents in Southeast Nigeria: An application of the socio-ecological model. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahn, M.H.; Culbreth, R.; Adams, S.; Kasirye, R.; Shanley, J. Demographic and psychosocial risk factors for adolescent pregnancies among sexually active girls in the slums of Kampala, Uganda. Afr. Health Sci. 2022, 22, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuamaiku, G.J.; Epuitai, J.; Andru, M.; Aleni, M. “I Don’t Support It for My Children”: Perceptions of Parents and Guardians regarding the Use of Modern Contraceptives by Adolescents in Arua City, Uganda. Int. J. Reprod. Med. 2023, 2023, 6289886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, M.; Super, S.; Oguttu, M.; Makenzius, M. Social judgments on abortion and contraceptive use: A mixed methods study among secondary school teachers and student peer-counsellors in western Kenya. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achen, S.; Rwabukwali, C.B.; Atekyereza, P. Contraceptive use among young women of pastoral communities of Karamoja sub-region in Uganda. Cult. Health Sex. 2022, 24, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhanu, Z.; Tushune, K.; Jebena, M.G. Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Use, Perceptions, and Barriers among Young People in Southwest Oromia, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2018, 28, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontiri, S.; Mutea, L.; Naanyu, V.; Kabue, M.; Biesma, R.; Stekelenburg, J. A qualitative exploration of contraceptive use and discontinuation among women with an unmet need for modern contraception in Kenya. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibira, S.P.S.; Karp, C.; Wood, S.N.; Desta, S.; Galadanci, H.; Makumbi, F.E.; Omoluabi, E.; Shiferaw, S.; Seme, A.; Tsui, A.; et al. Covert use of contraception in three sub-Saharan African countries: A qualitative exploration of motivations and challenges. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anglewicz, P.; Sarnak, D.; Gemmill, A.; Becker, S. Characteristics Associated with Reliability in Reporting of Contraceptive Use: Assessing the Reliability of the Contraceptive Calendar in Seven Countries. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2023, 54, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkenguye, W.; Ismail, H.; Urassa, E.P.; Yongolo, N.M.; Kagoye, S.; Msuya, S.E. Factors Associated with Modern Contraceptive Use Among Out of School Adolescent Girls in Majengo and Njoro Wards of Moshi Municipality, Tanzania. East Afr. Health Res. J. 2023, 7, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagoye, S.A.; Jahanpour, O.; Ngoda, O.A.; Obure, J.; Mahande, M.J.; Renju, J. Trends and determinants of unmet need for modern contraception among adolescent girls and young women in Tanzania, 2004–2016. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0000695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayanja, Y.; Kamacooko, O.; Lunkuse, J.F.; Kyegombe, N.; Ruzagira, E. Prevalence, Perpetrators, and Factors Associated with Intimate Partner Violence Among Adolescents Living in Urban Slums of Kampala, Uganda. J. Interpers. Violence 2023, 38, 8377–8399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, L.; Brahmbhatt, H.; Ndyanabo, A.; Wagman, J.; Nakigozi, G.; Kaufman, J.S.; Nalugoda, F.; Serwadda, D.; Nandi, A. The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s contraceptive use: Evidence from the Rakai Community Cohort Study in Rakai, Uganda. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 209, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahn, M.H.; Culbreth, R.; Salazar, L.F.; Kasirye, R.; Seeley, J. Prevalence of HIV and Associated Risks of Sex Work among Youth in the Slums of Kampala. AIDS Res. Treat. 2016, 2016, 5360180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahn, M.H.; Culbreth, R.; Masyn, K.E.; Salazar, L.F.; Wagman, J.; Kasirye, R. The Intersection of Alcohol Use, Gender Based Violence and HIV: Empirical Findings among Disadvantaged Service-Seeking Youth in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 3106–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, M.L.; Radovich, E.; Wong, K.L.M.; Owolabi, O.; Cavallaro, F.L.; Mbizvo, M.T.; Binagwaho, A.; Waiswa, P.; Lynch, C.A.; Benova, L. Pathways to increased coverage: An analysis of time trends in contraceptive need and use among adolescents and young women in Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolla, A.; Constance, M.; Ngcobo, N.; Mngadi, S.; Govathson, C.; Long, L.; Pascoe, S.J. “I want one nurse who is friendly to talk to me properly like a friend”: Learner preferences for HIV and contraceptive service provision in Gauteng, South Africa. Res. Sq. 2023, rs.3, rs-3725260. [Google Scholar]

- Kipp, W.; Chacko, S.; Laing, L.; Kabagambe, G. Adolescent reproductive health in Uganda: Issues related to access and quality of care. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2007, 19, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetui, M.; Ssekamatte, T.; Akilimali, P.; Sirike, J.; Fonseca-Rodríguez, O.; Atuyambe, L.; Makumbi, F.E. Geospatial Distribution of Family Planning Services in Kira Municipality, Wakiso District, Uganda. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2020, 1, 599774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuwasiima, A.; Nuwamanya, E.; Babigumira, J.U.; Nalwanga, R.; Asiimwe, F.T.; Babigumira, J.B. Acceptability and utilization of family planning benefits cards by youth in slums in Kampala, Uganda. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2019, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbreth, R.E.; Nielsen, K.E.; Mobley, K.; Palmier, J.; Bukuluki, P.; Swahn, M.H. Life Satisfaction Factors, Stress, and Depressive Symptoms among Young Women Living in Urban Kampala: Findings from the TOPOWA Project Pilot Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culbreth, R.; Swahn, M.H.; Salazar, L.F.; Kasirye, R.; Musuya, T. Intimate Partner Violence and Associated Risk Factors Among Youth in the Slums of Kampala. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP11736–NP11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swahn, M.H.; Palmier, J.; Culbreth, R.; Bbosa, G.S.; Natuhamya, C.; Matovu, G.; Kasirye, R. Alcohol Use among Young Women in Kampala City: Comparing Self-Reported Survey Data with Presence of Urinary Ethyl Glucuronide Metabolite. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swahn, M.H.; Natuhamya, C.; Culbreth, R.; Palmier, J.; Kasirye, R.; Dumbili, E.W. Alcohol marketing as a commercial determinant of health: Daily diary insights from young women in Kampala. Health Promot. Int. 2025, 40, daaf002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.L.M.; Restrepo-Méndez, M.C.; Barros, A.J.D.; Victora, C.G. Socioeconomic inequalities in skilled birth attendance and child stunting in selected low and middle income countries: Wealth quintiles or deciles? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasekwa, B.; Maluccio, J.A.; Ntozini, R.; Moulton, L.H.; Wu, F.; Smith, L.E.; Matare, C.R.; Stoltzfus, R.J.; Mbuya, M.N.N.; Tielsch, J.M.; et al. Measuring wealth in rural communities: Lessons from the Sanitation, Hygiene, Infant Nutrition Efficacy (SHINE) trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.-L.T.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.L.T.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochaska, J.J.; Sung, H.; Max, W.; Shi, Y.; Ong, M. Validity study of the K6 scale as a measure of moderate mental distress based on mental health treatment need and utilization. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 21, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraiber, L.B.; Latorre, M.D.R.D.O.; França, I., Jr.; Segri, N.J.; D’Oliveira, A.F.P.L. Validade do instrumento WHO VAW STUDY para estimar violência de gênero contra a mulher. Rev. Saúde Pública 2010, 44, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.S.; Mustillo, S.A. Using Predictions and Marginal Effects to Compare Groups in Regression Models for Binary Outcomes. Sociol. Methods Res. 2021, 50, 1284–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiimwe, J.B.; Ndugga, P.; Mushomi, J.; Ntozi, J.P.M. Factors associated with modern contraceptive use among young and older women in Uganda; a comparative analysis. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makumbi, F.E.; Nabukeera, S.; Tumwesigye, N.M.; Namanda, C.; Atuyambe, L.; Mukose, A.; Ssali, S.; Ssenyonga, R.; Tweheyo, R.; Gidudu, A.; et al. Socio-economic and education related inequities in use of modern contraceptive in seven sub-regions in Uganda. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, T.O.; Ojo, T.F.; Ijabadeniyi, O.A.; Ibikunle, M.A.; Oni, J.O.; Agboola, A.A. Prevalence and factors associated with contraceptive use among sexually active adolescent girls in 25 sub-Saharan African countries. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelland, L.N.; Salter, A.B.; Ryan, P. Performance of the modified Poisson regression approach for estimating relative risks from clustered prospective data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamhane, A.R.; Westfall, A.O.; Burkholder, G.A.; Cutter, G.R. Prevalence odds ratio versus prevalence ratio: Choice comes with consequences. Stat. Med. 2016, 35, 5730–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoulides, K.M.; Raykov, T. Evaluation of Variance Inflation Factors in Regression Models Using Latent Variable Modeling Methods. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2019, 79, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeboye, N.O.; Fagoyinbo, I.S.; Olatayo, T.O. Estimation of the Effect of Multicollinearity on the Standard Error for Regression Coefficients. IOSRJM J. Math. 2014, 10, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettema, W.G.; Aynalem, G.L.; Yismaw, A.E.; Degu, A.W. Modern Contraceptive Utilization and Determinant Factors among Street Reproductive-Aged Women in Amhara Regional State Zonal Towns, North West Ethiopia, 2019: Community-Based Study. Int. J. Reprod. Med. 2020, 2020, 7345820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayanja, Y.; Kamacooko, O.; Lunkuse, J.F.; Muturi-Kioi, V.; Buzibye, A.; Omali, D.; Chinyenze, K.; Kuteesa, M.; Kaleebu, P.; Price, M.A. Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis preference, uptake, adherence and continuation among adolescent girls and young women in Kampala, Uganda: A prospective cohort study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2022, 25, e25909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesema, Z.T.; Tesema, G.A.; Boke, M.M.; Akalu, T.Y. Determinants of modern contraceptive utilization among married women in sub-Saharan Africa: Multilevel analysis using recent demographic and health survey. BMC Women’s Health 2022, 22, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazibwe, J.; Masiye, F.; Klingberg-Allvin, M.; Ekman, B.; Sundewall, J. Inequality in modern contraceptive use and unmet need for contraception among women of reproductive age in Zambia. A trend and decomposition analysis 2007–2018. Reprod. Health 2024, 21, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sserwanja, Q.; Musaba, M.W.; Mukunya, D. Prevalence and factors associated with modern contraceptives utilization among female adolescents in Uganda. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bameka, A.; Kakaire, O.; Kaye, D.K.; Namusoke, F. Early discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraceptives and associated factors among women discontinuing long-acting reversible contraceptives at national referral hospital, Kampala-Uganda; a cross-sectional study. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2023, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bande, A.D.; Handiso, T.B.; Hanjelo, H.W.; Jena, B.H. Early discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraceptives methods and its associated factors in Hosanna town, central Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubu, I.; Salisu, W.J. Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nara, R.; Banura, A.; Foster, A.M. Assessing the availability and accessibility of emergency contraceptive pills in Uganda: A multi-methods study with Congolese refugees. Contraception 2020, 101, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwame, K.A.; Bain, L.E.; Manu, E.; Tarkang, E.E. Use and awareness of emergency contraceptives among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2022, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.E.K.; Shiras, T. Where Women Access Contraception in 36 Low- and Middle-Income Countries and Why It Matters. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2022, 10, e2100525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anbesu, E.W.; Alemayehu, M.; Asgedom, D.K.; Jeleta, F.Y. Women’s decision-making power regarding family planning use and associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2023, 11, 20503121231162722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adde, K.S.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Dickson, K.S.; Paintsil, J.A.; Oladimeji, O.; Yaya, S. Women’s empowerment indicators and short- and long-acting contraceptive method use: Evidence from DHS from 11 countries. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center, K.E.; Gunn, J.K.L.; Asaolu, I.O.; Gibson, S.J.; Ehiri, J.E. Contraceptive Use and Uptake of HIV-Testing among Sub-Saharan African Women. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoth, S.; Machange, J.; Karino, K.; Mtenga, S.; Mkopi, A.; Levira, F. The impacts of family planning and HIV service integration on contraceptive prevalence among HIV positive women in Tanzania: A comparative analysis from the 2016/17 Tanzania HIV impact survey. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 2023, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibikunle, O.O.; Ipinnimo, T.M.; Afape, A.O.; Ibikunle, A.I.; Bakare, C.A.; Ajidagba, B.; Ibirongbe, D.O.; Ajidahun, E.O.; Durowade, K.A.; Akinwumi, A.F.; et al. Trends and Determinants of Non-Utilization of Modern Contraception in Ekiti State, Nigeria: A Ten-Year Review. J. Mother Child 2023, 27, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Some, S.Y.M.; Pu, C.; Huang, S.-L. Empowerment and use of modern contraceptive methods among married women in Burkina Faso: A multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Habib, S.E. “I don’t want my marriage to end”: A qualitative investigation of the sociocultural factors influencing contraceptive use among married Rohingya women residing in refugee camps in Bangladesh. Reprod. Health 2024, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, N.; Newman, M.; Malumo, S.; Chitembo, L.; Gaffield, M.E. Integrating Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Within HIV Services: WHO Guidance. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2021, 2, 735281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omona, K.; Muhanuzi, G. Factors influencing utilization of modern family planning services by persons living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus at Luwero Hospital, Uganda. Afr. Health Sci. 2022, 22, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakibinga, P.; Matanda, D.J.; Ayiko, R.; Rujumba, J.; Muiruri, C.; Amendah, D.; Atela, M. Pregnancy history and current use of contraception among women of reproductive age in Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda: Analysis of demographic and health survey data. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahinkorah, B.O.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Seidu, A.-A.; Agbaglo, E.; Budu, E.; Mensah, F.; Adu, C.; Yaya, S. Sexual violence and unmet need for contraception among married and cohabiting women in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmamaw, D.B.; Tafere, T.Z.; Negash, W.D. Prevalence of teenage pregnancy and its associated factors in high fertility sub-Saharan Africa countries: A multilevel analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Culbreth, R.E.; Swahn, M.H.; Kasirye, R. Examining correlates of alcohol related condom-less sex among youth living in the slums of Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Care 2020, 32, 1246–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbreth, R.; Swahn, M.H.; Salazar, L.F.; Ametewee, L.A.; Kasirye, R. Risk Factors Associated with HIV, Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI), and HIV/STI Co-infection Among Youth Living in the Slums of Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahn, M.H.; Culbreth, R.; Salazar, L.F.; Tumwesigye, N.M.; Kasirye, R. Psychosocial correlates of self-reported HIV among youth in the slums of Kampala. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Family Planning/Contraception Methods. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/family-planning-contraception (accessed on 28 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).