A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Post-COVID-Condition Rehabilitation and Recovery Intervention Delivered in a Football Club Community Trust

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Intervention Context and Setting

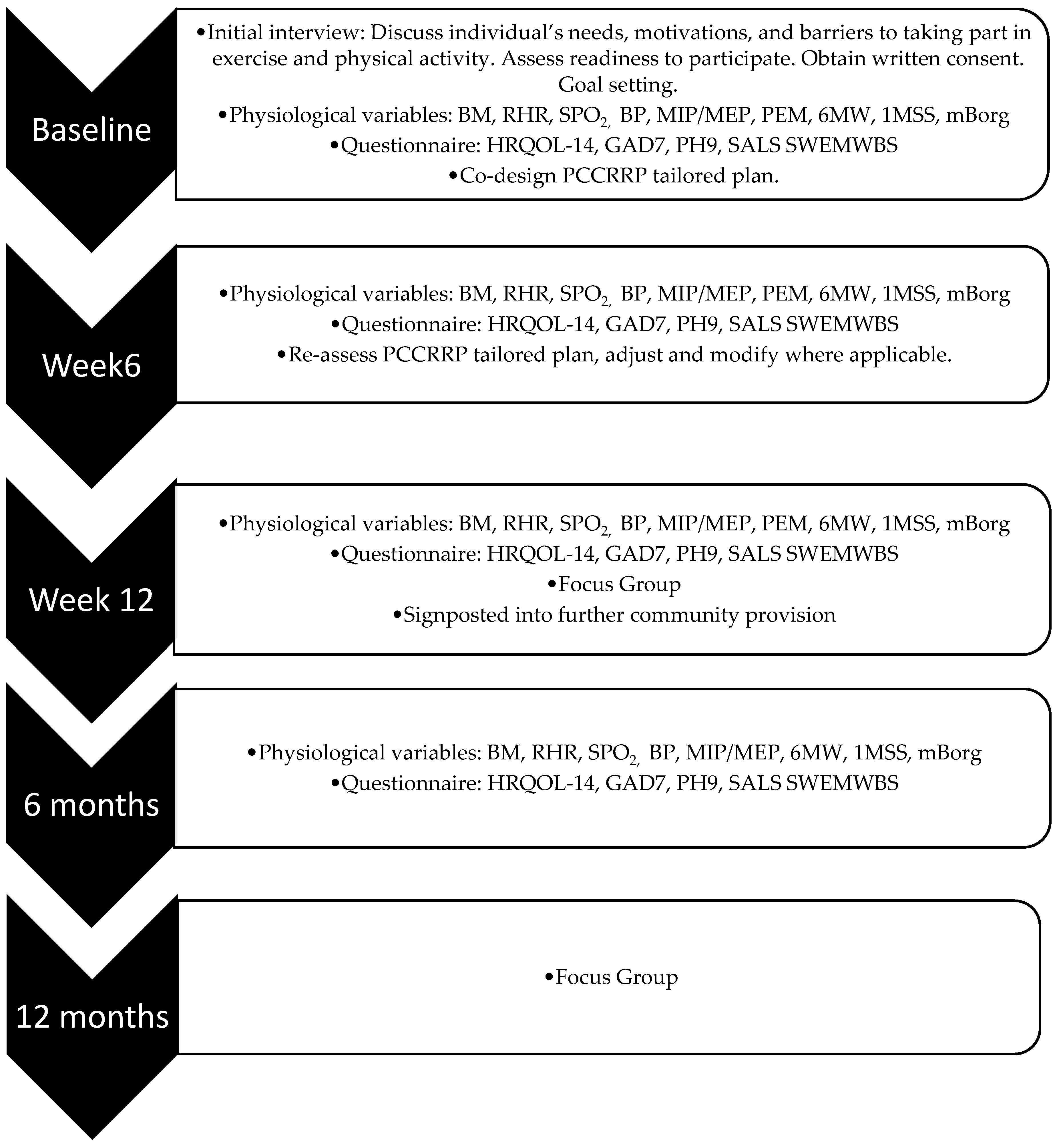

2.2. Participants and Procedures

2.3. Clinical and Physiological Measures

2.4. Focus Groups

2.5. Data Reduction and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Exercise Variables

3.3. Physiological Variables

3.4. Questionnaire Variables

3.5. Focus Group at Week 12

3.5.1. Reach

3.5.2. Effectiveness

3.5.3. Adoption

3.5.4. Implementation

3.5.5. Maintenance

3.6. Focus Group at 12 Months

3.6.1. Reach

3.6.2. Effectiveness

3.6.3. Maintenance

3.7. Summary of Findings

3.8. Strengths and Limitations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Post-COVID-Condition Syndrome (Long COVID); National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Spencer, R.; Xu, S.; Haupert, L.Z. Global prevalence of post-acute sequelae of Covid-19 (PASC) or long covid: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics. Prevalence of Long COVID Symptoms and Associated Activity Limitations; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, A.G.; Salamon, S.; Pretorius, E.; Joffe, D.; Fox, G.; Bilodeau, S.; Bar-Yam, Y. Review of organ damage from COVID and Long COVID: A disease with a spectrum of pathology. Med. Rev. 2024, 5, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, P.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L.; et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 420–422, Erratum in Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheblawi, M.; Wang, K.; Viveiros, A.; Nguyen, Q.; Zhong, J.C.; Turner, A.J.; Raizada, M.K.; Grant, M.B.; Oudit, G.Y. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 receptor and regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1456–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.I.; Abdelmoneim, A.H.; Mahmoud, E.M.; Makhawi, A.M. Cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients, its impact on organs and potential treatment by QTY code-designed detergent-free chemokine receptors. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 8198963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daynes, E.; Evans, R.A.; Greening, N.J.; Bishop, N.C.; Yates, T.; Lozano-Rojas, D.; Ntotsis, K.; Richardson, M.; Baldwin, M.M.; Hamrouni, M.; et al. Post-Hospitalisation COVID-19 Rehabilitation (PHOSP-R): A randomised controlled trial of exercise-based rehabilitation. Eur. Respir. J. 2025, 65, 2402152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sick, J.; Steinbacher, V.; Kotnik, D.; König, F.; Recking, T.; Bengsch, D.; König, D. Exercise rehabilitation in post COVID-19 patients: A randomized controlled trial of different training modalities. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2025, 61, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, G.; Sandhu, H.; Bruce, J.; Sheehan, B.; McWilliams, D.; Yeung, J.; Jones, C.; Lara, B.; Alleyne, S.; Smith, J.; et al. Clinical effectiveness of an online supervised group physical and mental health rehabilitation programme for adults with post-covid-19 condition (REGAIN study): Multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2024, 384, e076506, Erratum in BMJ 2024, 385, q988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Chen, X.-K.; Sit, C.H.-P.; Liang, X.; Li, M.-H.; Ma, A.C.-H.; Wong, S.H.-S. Effect of Physical Exercise–Based Rehabilitation on Long COVID: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2023, 56, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Astill, S.L.; Sivan, M. The Relationship Between Physical Activity and Long COVID: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, A.; Parnell, D.; Zwolinsky, S.; Hargreaves, J.; McKenna, J. Effect of a health-improvement pilot programme for older adults delivered by a professional football club: The Burton Albion case study. Soccer Soc. 2014, 15, 902–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, Z.; Zwolinsky, S.; Kime, N.; Pringle, A. A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of CARE (Cancer and Rehabilitation Exercise): A Physical Activity and Health Intervention, Delivered in a Community Football Trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RE-AIM. Home–Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation Maintenance. RE-AIM. 2025. Available online: https://re-aim.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Cotler, J.; Holtzman, C.; Dudun, C.; Jason, L.A. A Brief Questionnaire to Assess Post-Exertional Malaise. Diagnostics 2018, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vøllestad, N.K.; Mengshoel, A.M. Post-exertional malaise in daily life and experimental exercise models in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1257557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, P.; Hellberg, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wisén, A.; Clyne, N. The Borg scale is a sustainable method for prescribing and monitoring self-administered aerobic endurance exercise in patients with chronic kidney disease. Eur. J. Physiother. 2022, 25, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topouchian, J.; Hakobyan, Z.; Asmar, J.; Gurgenian, S.; Zelveian, P.; Asmar, R. Clinical accuracy of the Omron M3 Comfort® and the Omron Evolv® for self-blood pressure measurements in pregnancy and pre-eclampsia—Validation according to the Universal Standard Protocol. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2018, 14, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter. Pulse Oximeter. Available online: https://salter.com/oxywatch-fingertip-pulse-oximeter/ (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Health Management. Respiratory Muscle Exerciser/Hand-Held MicroRPM. Available online: https://healthmanagement.org/c/icu/products/respiratory-muscle-exerciser-hand-held-microrpm (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Sport England. Active Lives Adult Survey: November 2017–November 2018; Sport England: Loughborough, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust. Six-Minute Walk and One-Minute Sit to Stand Tests. Royal Brompton & Harefield Hospitals. Available online: https://www.rbht.nhs.uk/our-services/heart/pulmonary-hypertension-service/tests (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Read, J.R.; Sharpe, L.; Modini, M.; Dear, B.F. Multimorbidity and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 221, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muls, A.; Georgopoulou, S.; Hainsworth, E.; Hartley, B.; O’Gara, G.; Stapleton, S.; Cruickshank, S. The psychosocial and emotional experiences of cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. In Seminars in Oncology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody, S.; Richards, D.; Brealey, S.; Hewitt, C. Screening for Depression in Medical Settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): A Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 1596–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Scotland. The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS); NHS Health Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wyke, S.; Hunt, K.; Gray, C.M.; Fenwick, E.; Bunn, C.; Donnan, P.T.; Rauchhaus, P.; Mutrie, N.; Anderson, A.S.; Boyer, N.; et al. Football Fans in Training (FFIT): A randomised controlled trial of a gender-sensitised weight loss and healthy living programme for men—End of study report. Public Health Res. 2015, 3, 1–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, A.; Zwolinsky, S.; McKenna, J.; Robertson, S.; Daly-Smith, A.; White, A. Health improvement for men and hard-to-engage-men delivered in English Premier League football clubs. Health Educ. Res. 2014, 29, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Cuthill, I.C. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: A practical guide for biologists. Biol. Rev. 2007, 82, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlis, C.; Barradell, A.; Gardiner, N.Y.; Chaplin, E.; Goddard, A.; Singh, S.J.; Daynes, E. The Recovery Journey and the Rehabilitation Boat—A qualitative study to explore experiences of COVID-19 rehabilitation. Chronic Respir. Dis. 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, R.; Ashton, R.E.; Skipper, L.; Phillips, B.E.; Yates, J.; Thomas, C.; Ferraro, F.; Bewick, T.; Haggan, K.; Faghy, M.A. Long COVID quality of life and healthcare experiences in the UK: A mixed method online survey. Qual. Life Res. 2023, 33, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Construct | Application in This Study | Source of Data |

|---|---|---|

| Reach | The number, proportion, and representativeness of people living with post-COVID condition (PLWPCC) who participated in a PCCRRP. | Questionnaire data collected at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Focus groups were conducted during week 12 and at 12 months. |

| Effectiveness | The impact of the PCCRRP on physical activity, fatigue, health-related quality of life, and confidence in daily living. | Quantitative physiological data and questionnaire data collected at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Focus groups were conducted during week 12 and at 12 months. |

| Adoption | The profile of PLWPCC who engaged in the PCCRRP includes their physical activity, health status, and reported barriers and facilitators. | Quantitative physiological data and questionnaire data collected at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Focus groups were conducted during week 12 and at 12 months. |

| Implementation | The key PCCRRP intervention design and delivery characteristics that participants reported as being influential in facilitating their adoption. | Focus groups were conducted during week 12 and at 12 months. |

| Maintenance | The continued engagement of PLWPCC in exercise and physical activity upon exit of the PCCRRP for positive health-related quality of life. | Quantitative physiological data and questionnaire data collected at 6 months. Focus groups were conducted during week 12 and at 12 months. |

| Variable | Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 52 ± 9 years | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 2 (29) |

| Female | 5 (71) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married/With Partner | 5 (71) |

| Single/Divorced/Widow | 2 (29) |

| Other | |

| Ethnicity | |

| White British | 7 (100) |

| Occupation | |

| Care | 4 (57) |

| Education | 1 (14) |

| Manual Labour | 1 (14) |

| Unemployed | 1 (14) |

| Football Fan | 3 (43) |

| Non-Football Fan | 4 (57) |

| Fan of Host Club | 0 (0) |

| Fan of Another Club | 3 (43) |

| Dimension | Baseline | Week 6 | Week 12 | 6 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Are you limited in any way in any activities because of impairment or health problem? | Yes: 7 (100) | Yes: 4 (57.1) No: 3 (42.9) | Yes: 1 (14.3) No: 6 (85.7) | Yes: 1 (14.3) Not sure/Don’t know: 1 (14.3) No:5 (71.4) |

| What is the major impairment or health problem that limits your activities? | Other impairment/problem: 1 (14.3) Depression/anxiety/emotional problem: 3 (42.9) Lung/breathing problem: 3 (42.9) | Other impairment/problem: 2 (28.6) Lung/breathing problem: 2 (28.6) | Depression/anxiety/emotional problem: 1 (14.3) | Depression/anxiety/emotional problem: 1 (14.3) Lung/breathing problem: 1 (14.3) |

| For how long have your activities been limited because of your major impairment? | Months: 4 (57.1) Years: 3 (42.9) | Days: 2 (28.6) Months: 1 (14.3) Years: 1 (14.3) | Months: 1 (14.3) | Months: 1 (14.3) Not sure/Don’t know: 1 (14.3) |

| Because of any impairment or health problem, do you need the help of other people with your personal care needs, e.g., eating, bathing, dressing, or getting around the house? | Yes: 2 (28.6) No: 5 (71.4) | No: 7 (100) | Yes: 1 (14.3) No: 6 (85.7) | No: 7 (100) |

| Because of any impairment or health problem, do you need the help of other people in handling your routine needs, e.g., household chores, shopping, or getting around for other purposes? | Yes: 5 (71.4) No: 2 (28.6) | No: 7 (100) | Yes: 1 (14.3) No: 6 (85.7) | No: 7 (100) |

| Dimension | Baseline | Week 6 | Week 12 | 6 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During the past 30 days, for about how many days did pain make it hard for you to do your usual activities, such as self-care, work, or recreation? | 5 (71.4) 4 = 30 days 1 = 23 days 2 (28.6) 2 = 0 days | 6 (85.7) 6 = 0 days 1 (14.3) 1 = 3 days | 6 (85.7) 6 = 0 days 1 (14.3) 1 = 1 day | 6 (85.7) 6 = 0 days 1 (14.3) 1 = Not sure/Don’t know |

| During the past 30 days, for about how many days have you felt sad, blue, or depressed? | 4 (57.1) 3 = 30 days 1 = 20 days 2 (28.6) 2 = 0 days 1 (14.3) 1 = Not sure/Don’t know | 3 (42.9) 1 = 10 days 1 = 5 days 1 = 2 days 4 (57.1) 4 = 0 days | 2 (28.6) 1 = 10 days 1 = 5 days 5 (71.4) 5 = 0 days | 3 (42.9) 1 = 25 days 1 = 5 days 1 = 2 days 4 (57.1) 4 = 0 days |

| During the past 30 days, for about how many days have you felt worried, tense, or anxious? | 4 (57.1) 3 = 30 days 1 = 20 days 2 (28.6) 2 = 0 days 1 (14.3) 1 = Not sure/Don’t know | 5 (71.4) 1 = 10 days 1 = 7 days 2 = 5 days 1 = 1 day 2 (28.6) 2 = 0 days | 3 (42.9) 1 = 20 days 1 = 5 days 1 = 3 days 4 (57.1) 4 = 0 days | 3 (42.9) 1 = 10 days 1 = 5 days 1 = 2 days 4 (57.1) 4 = 0 days |

| During the past 30 days, for about how many days have you felt you did not get enough rest or sleep? | 6 (85.7) 4 = 30 days 1 = 15 days 1 = 2 days 1 (14.3) 1 = Not sure/Don’t know | 5 (71.4) 2 = 10 days 2 = 5 days 1 = 1 day 2 (28.6) 2 = 0 days | 4 (57.1) 2 = 10 days 2 = 2 days 3 (42.9) 3 = 0 days | 4 (57.1) 1 = 20 days 1 = 10 days 1 = 7 days 1 = 5 days 3 (42.9) 3 = 0 days |

| During the past 30 days for about how many days have you felt very healthy and full of energy? | 1 (14.3) 1 = 7 days 5 (71.4) 5 = 0 days 1 (14.3) 1 = Not sure/Don’t know | 7 (100) 1 = 30 days 2 = 25 days 2 = 20 days 1 = 7 days | 7 (100) 3 = 30 days 1 = 28 days 1 = 25 days 1 = 10 days 1 = 5 days | 6 (85.7) 3 = 30 days 1 = 15 days 1 = 10 days 1 = 4 days 1 (14.3) 1 = Not sure/Don’t know |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Light at the end of the tunnel | Renewed hope for the future | “Life is back to normal. Back to a bit of a routine. I loved the boxing in the gym, at first, I just couldn’t get the coordination, but the more I did it the better and stronger I got.” (Female) |

| “All I wanted was to get back to work and get back to normal. So, coming to the first gym session, I thought great, this is the road back to it. I had become withdrawn and was getting out less and less. These sessions were in my diary, I had to drive to the gym which was great, I got talking with the exercise instructors and other people. That was a big thing for me.” (Male) | ||

| “Feeling normal again. Work, kids, grandkids, shopping.” (Male) | ||

| “The programme gives the belief that there’s hope at the end of this as well, that it’s not just that your stuck and you’re not going to get better. It gives you hope that you can get better, that you can get better and be normal again.” (Male) | ||

| “It’s given me more fight really from being so down and despondent and physically inactive to being able to actually go and do things and plan to do things.” (Female) | ||

| Functional Improvements | Physical Function | “I felt my body had let me down and I don’t feel like that now. I feel like it’s stronger and more powerful than it was before. I like seeing people, going for walks with the kids, chasing the dogs and so on, it’s definitely improved.” (Female) |

| “We recently went to Disneyland Paris we did 20,000 steps with the kids over three days. I never thought I’d be able to do that. And that was brilliant to be just normal and keep up with them.” (Female) | ||

| “It’s like I have more energy when I go to the gym, than on the days that I have not gone.” (Male) | ||

| “It gives you the motivation. When you’ve gone to the gym and then you come back you can do stuff, whereas if you don’t go to the gym, you will put things off in the day.” (Female) | ||

| “I definitely achieve more when I go to the gym. If I get up and go swimming in the morning, I feel much better.” (Female) | ||

| “Normally I get out of the car and shriek in pain. It just dawned on me the other day, I didn’t, I just got out the car and just walked.” (Male) | ||

| Mental Wellbeing | Self-esteem | “My self-esteem improved massively, and taking care of myself, putting on makeup. I mean, I don’t wear a lot of makeup anyway but just making an effort to wear makeup and do my hair and put nice clothes on, rather than slobbing about and not doing my hair.” (Female) |

| “Better self-esteem.” (Male) | ||

| “I did not realise that it had improved my self-esteem, but my husband, and my kids would tell me that it had. And I felt more like myself.” (Female) | ||

| “I felt really good. And towards the end of the programme, I started a new job, and we’ve moved house. I hadn’t recognised how far I’d come.” (Female) | ||

| Confidence and Self-Efficacy | “I’m confident. More competent. I’m proud.” (Female) | |

| “I’m more assertive than I’ve ever been.” (Female) | ||

| “I am back to my happiest self, messing about again and teasing people and I can take it, but I’ll give it as well.” (Female) | ||

| “I do achieve everything. I get the house done, we eat homemade meals and go to the gym. And you know, I don’t know how I manage it when I think about how I was before where I couldn’t do anything.” (Female) | ||

| “Believe in yourself.” (Female) | ||

| “It’s just made me realise, you know, I was really ill and there’s so many more things I want to do and see and achieve. And actually, doing the programme I suppose has given me the confidence I think to kind of do that just kind of push for that.” (Female) | ||

| “So, I’ve just got a promotion at work. So, there was a team leader position in respiratory care, in which I do a lot with the children that are Trachea vented. And I didn’t go for it because I lost my confidence, and I didn’t think I’d be able to manage. So, I didn’t go for it the first time somebody else did, but they didn’t get the job. So, then it was advertised externally and then I applied for it last week and had an interview and I got it.” (Female) | ||

| Advocacy for broader mental health support in the face of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. | “I mean, I’ve got to say from a professional point of view, from a mental health perspective, how it helped me with my mental health. It would be nice to see something like this because there are really bad mental issues at the moment. Generally, people coming off the back of COVID, families and everything. So, doing something like this to support mental health alone would be awesome. Really. It would be life changing for not just people who have had COVID, but mental health in general.” (Female) | |

| Link between physical activity and mental health | “Some people wouldn’t necessarily think physical exercise and how well it just really impacts on your mental health until you’ve actually experienced benefits of it. You know, but people that are generally quite low, if they were referred into a service like this you know, did some things like this exercise, and then made those links, you know it could be life changing for a lot of families as well.” (Female) | |

| “My mental health was so much better during those 12 weeks on the programme, so when I didn’t go to the gym, please don’t shout at me Steven, but when I was poorly over Christmas, I really felt myself dip! And actually, going back to the gym helped because when I was going in, I felt more resilient about taking things on, and then I stopped going I was like ooh, so I went back! So, I know that is something, my brain goes to me, go to the gym! If I am feeling stressed, go to the gym.” (Female) | ||

| “I felt like that over Christmas, not really got the energy, and don’t really feel like you want to do anything, but you notice yourself feeling down again quite quickly.” (Female) | ||

| Exercise rehabilitation and recovery | Motivation | “It’s your positivity, and its tailor made to you and then you give push where it’s needed and just your expertise as well. Like explaining how your body works and how you can make yourself feel better.” (Female) |

| Motivation and productivity | “It gives you the motivation. Like say, when you’ve gone to the gym and then you come back home you can do stuff. Whereas if you don’t go to the gym, you will put things off in the day. Like shopping, sometimes when I go to the gym, after I’ll then go to ALDI, to do my shopping, but then, but if I was at home and didn’t do that then I’d be like I really need to go shopping and I would sit there and end up not doing it.” (Female) | |

| “The exercise instructor was really supportive.” (Male) | ||

| “It’s hard when you go to the gym on your own and you haven’t got someone in your earhole. I would say what do I do now? And then he’s going come on another minute, another minute. And, like, pushing you, push it up another notch.” (Female) | ||

| Tailored exercise sessions | “So, like some things, like I suffer with my back. He would tailor it to help my back if it was playing up, he would put things in you know, to loosen it sort of thing and stretch it out.” (Female) | |

| “At one point he had me doing circuit training. I was doing all kinds of things, from push-ups, sit-ups, everything. He would have me doing circuits on the cardio machines as well. So, he would have you do 10 min on that, 10 min on that, etc. And I would literally be doing that for an hour. Running between machines! And to be fair he taught me so many new skills in the gym. He knew I would get bored doing cardio for long periods of time. Did my head in! I hated being on anything for longer than 20 min. He knew that I would get bored so he wouldn’t do that.” (Female) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Mental well-being | Downward spiral of mental health | “I had no motivation because I had no energy and as a single parent I became really ill with my mental health as well because I thought I was not supporting my children I was letting them down.” (Female) |

| “The more I stayed in the more I got withdrawn, especially with working in a school because I felt that if someone sees me outside, they will think he looks alright there’s nothing wrong with him. So, then you start staying in more and more and not going anywhere and not doing anything. And then it’s just a downward spiral.” (Male) | ||

| Ripple effect of PCC on family dynamics | “I just think it affected my whole family because I’m the one that organises things and so because of that nothing else got done. It was just a horrible atmosphere because I wasn’t the one cheering everybody up to do stuff and I was just really grouchy; more grouchy than normal! Just everything was so on top of me, and I just shouted, or I just slept. I would just go and lie down, depressed.” (Female) | |

| “I had pretty similar to that really and just sort of not being able to do anything and just feeling so anxious and not able to function you know.” (Female) | ||

| Social withdrawal | “I got embarrassed as well because I got to that point where all I did was moan and talk about being ill. Because I’ve been ill so long that I became so embarrassed about it. I stopped talking to my friends because the only thing I had to add to the conversation was moaning about how I was feeling all the time. I was sick of hearing myself saying it! I was sick of explaining how I felt because obviously it’s not something you can see, is it either? So, you know, getting other people to understand what LC was at the time was quite difficult as well because people just think hmm, right, so, you’re making it up. Don’t be silly! You know, it just wasn’t in my head. I definitely felt this way. I just really could not function. And it’s not that I didn’t try because I did. I just couldn’t get a break.” (Female) | |

| Feelings of injustice and burden | “It was very overwhelming, and it was very frustrating because I saw the people around me get covid and not be as poorly and not have the kind of detrimental day-to-day impact on their lives. They were still able to walk their children up the hill to school, whereas I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t take my children to school; I could barely put clothes in the washing machine and do the housework. And my husband was having to pick up a lot of the slack in the home, it felt more like he was my carer than my husband.” (Female) | |

| Internal struggle with anxiety | “A big one for me was the anxiety. And there’s just a constant kind of mental battle that I was having with myself daily basis.” (Female) | |

| Physical Activity Adoption | Motivation to Exercise | “So, since I started the programme, I have lost four and a half stone. I have stopped smoking. I have started to do these online challenges. I have completed couch to 5K. I’ve always been able to swim, but I couldn’t swim when I got COVID because I kind of lost the ability to have the rhythm with my breathing. But since joining your programme I’ve swam the equivalent of the English Channel.” (Female). |

| “I think it was brilliant! During COVID I struggled to walk my dog and to even step up onto the pavement curb. All the strength in my legs had gone. I got on the cross-trainer and thought, this is my machine. Where I work, we have a gym, so I use it now. I go twice a week.” (Male) | ||

| When we got towards the end of the 12-week programme I felt quite sad because I didn’t want it to end. Since it’s finished, I have joined a gym, and I go with my eldest son. He keeps me accountable, and he is competitive like me which is good.” (Male) | ||

| “The stuff I’ve done, never in a million years is what I would do! Even before I had COVID I never thought I would be a runner. My kids used to joke about what would happen if there was a zombie apocalypse mum? Now I would be like, you can’t catch me! Never did I think I would be able to run ever! I never thought I would lose this much weight.” (Female) | ||

| “The gym has become a hobby; it is no longer a torturous event!” (Female) | ||

| “I’ve spent so many days in the gym, they all know me now! So, before I even start the class, they are getting me doing 20 press ups! I actually found a love for something.” (Female) | ||

| Barriers to physical activity | Pre PCCRRP symptoms | “I felt like I’ve got this big wide band across the bottom of my chest and so even breathing normally I struggled, just walking in the house, it was hard and walking up the stairs. I couldn’t take the dogs for a walk because then this band would get tighter and then I couldn’t breathe. And it was just scary that I couldn’t breathe.” (Female) |

| “I felt just the same when walking the dog, I would still have to sit down and didn’t have the energy to take my shoes off. Until I joined you guys. I wasn’t going anywhere.” (Male) | ||

| Overcoming pre-existing gym intimidation | “I didn’t have the confidence to use the gym to be honest, but I haven’t got any worries about using it because I’d always been part of it. I would go in to do classes quite happily, but I didn’t really understand what you use in the gym or how to use it or have the confidence to use it.” (Female) | |

| “I was like yourself because I had that preconceived idea. I’ve always done stuff like that, at school I’d always do stuff, I’d run with the children, I’d play football, I’d do everything like that, and I thought I am keeping myself fit because I’m always nonstop. I’ve got friends who went to the gym, and I thought, no, that’s really not for me. Everyone in there will be like you see on the TV, everyone will look at me and go, no. So going was quite scary at first because it’s like, what am I going to do? How do these machines work? Or I don’t really get it, but after the first couple of sessions like, actually, that’s really good.” (Female) | ||

| Impact on physical ability. | “Well pre-covid I was swimming every day. And I worked with complex children with special needs. So, I’d be lifting, moving, chasing, you know, on the go the whole day. But then as well, I was supporting my family because I’m a single parent and doing all the jobs at home. After covid, I couldn’t swim because I couldn’t breathe properly to swim. And I couldn’t work. There’s no way I could have managed to work and looked after my children.” (Female) | |

| “I would walk the dog and I noticed when I got in, I would have to sit on the stairs for 5 min before I got the energy to take my shoes off because I just couldn’t do it. It crept up on me, but very quickly, if you like. I noticed if I was by a curb unless I was walking at it, I would have to throw my arms up to get up it. My strength had gone completely out of my legs. I’ve lost my strength.” (Male) | ||

| Limitations in physical and cognitive ability | “Pre COVID-I was pretty much nonstop because I was teaching primary school children and then I’ve got my two boys because I have those on my own. So, I’ve got my two boys and constantly on the go with those. So, one of them plays football, so we’re doing training, we would do football matches. With the little one, we’re out on our bikes. I’d also got another business on the side which was American based. So, I was up till late, and I was making phone calls bringing stuff back and it was using the Car, so you know, moving the trailer around to do lots of trips it was non-stop! And then covid hit and it more or less stopped everything. And then I wasn’t able to stand up, it took the job away because I couldn’t stand up and teach all day. I couldn’t think quick enough, and I tried to go back to work three times on a phased return, and it got to the point I was trying to teach fractions with the year fives, and I just could not think to even work it out.” (Male) | |

| Loss of confidence and ability to fulfil professional duties | “I’m a scuba dive instructor and I was teaching this lady in the pool just a finning technique, swimming underwater with the fins on, and she was swimming away from me and I thought I haven’t got a hope in hell of catching her up if anything went wrong, and if this was in open water, you know it would be serious. So, I took myself out of the equation, I had to stop instructing. Thankfully, I am back now since your programme, and I have been signed off for 3 years to instruct again.” (Male) | |

| Travel | “I found it an issue, because of the distance, having no money, the stress of travelling.” (Female) | |

| “Bit of a barrier because of my new job. And so financially became a bit of an issue because I was coming from Tamworth.” (Female) | ||

| “You can say the travelling was good because it gave that reflection time on the way home. You’ve got to build yourself up before you got there, but then you could reflect on the way home. So, I did like the travel side of things.” (Male) | ||

| Accessibility | “It was really handy for me; it’s really straightforward five minutes door to door.” (Female) | |

| “You need a programme in every town and every city! That’s what we need.” (Female) | ||

| Shifting focus from self-care to reintegration into daily life during LC recovery | “As the programme went on, finding time I found was harder, because at the start this was the big thing that I am doing. Whereas, as I started to get better, I was doing more in terms of my family or work.” (Male) | |

| Desire for social connection and shared experience | “I think it would have been nice to meet everybody at the beginning of the programme. And then we could swap phone numbers and meet at the gym. It would be nice if you didn’t do it every time, but you know, it might not be everybody at the same time, but just a walk around somewhere because we’ve all been through the same thing.” (Female) | |

| “It would have helped if we had all met earlier on. So, it would have been nice to meet everybody earlier on, just for emotional support, I guess as well. I was on my own. Nobody else had got it, and it would have been so helpful if I knew everyone here and, you know, just talked, I’ve had a rubbish day I’m exhausted, someone to understand.” (Female) | ||

| Social accountability | “So, you could meet and then have a coffee after. Recently I have made excuses not to go to the gym. Whereas I think if I’ve made like plans, or you’d arranged to meet with somebody then you’re more likely and will. And they’ve gone through what you’ve gone through.” (Female) | |

| “Because, like, when with the four of us did meet up, so halfway through the programme, when we were here for the news, going on TV, I think it was good because it was just sitting, talking very informal. And we talked about it (LC). We did a bit of networking, tying us together, that would have been good then.” (Male) | ||

| Motivation for adopting PCCRRP | Feelings of guilt and shame | “After spending five days on the ward on oxygen and eventually coming home with a walking stick. And not being able to do anything, you know, like just literally just being a shadow of my former self really. And it took a good six to nine months to feel better. I was so unhappy, and I never got back to the point that I was before I had covid. There’s a lot of guilt and shame. I think there’s a lot of shame I carried around with me, just like why me? Why did this happen?” (Female) |

| Loss of professional identity and confidence | “I have been a teacher for 29 years! It was second nature! I could walk into a classroom and do a lesson off the top of my head and not have to think about anything. I could go and do it. If someone said I can’t do an assembly, can you do it? Yeah. Walk into an assembly, make up stories off the top of my head and…That ability I lost.” (Male) | |

| Disorienting cognitive effects | “I would be driving somewhere, and the number of times I went, and I’d end up somewhere different. We were going to go to IKEA, and I was going the wrong way up the M6 and it’s like, where am I going to? And I was heading towards Liverpool, not towards Walsall! I don’t know why but I knew I was going somewhere.” (Male) | |

| Loss of multitasking ability and executive function | “Well, I was like the queen of multitasking before I got covid. I was teaching full time looking after four kids, the house. My husband worked a 60-h week and then just after I got covid I was just overwhelmed I think, constantly with everything. I just couldn’t go into supermarket because I was so anxious about catching covid again and that’s if I could actually get round the supermarket, I couldn’t push the trolley. So, Steve would have to push the trolley. I couldn’t even make a shopping list. It’s just cognitively I was just really struggling to kind of … But before I could be on the phone, planning a lesson, I just couldn’t do any of that anymore at all, it had all gone.” (Female) | |

| Confidence and coping mechanisms | “Even now I’ve lost my confidence. So, before I had COVID I could go in and teach them off the cuff, but now I’m literally like everything, I want to over plan. And I’m so meticulous about everything because I’m so worried about getting it wrong. I just feel like even though I’ve always been quite an anxious person, I’m able to be outwardly confident, whereas I think that’s kind of gone a little bit. Or gone a lot to be fair. But going to the gym helped with that, it really helped with that.” (Female) | |

| Yearning for recovery | “Because I’d had spent so long being sat at home and every time I rang the doctor, every time I spoke to someone, like what can you do for me? What’s happening? There was nothing. It’s like what can you give me, is there something to take? And there was no help. It seemed almost all I kept being told was it’ll take time and it’s like well, I can’t just keep sitting at home and wasting time. I want to be doing something. I’m Impatient anyway because I can’t just do nothing. If I broke my leg, they would say it’s six weeks in plaster, then this and then you’re back to normal. And I was like, well, when can I be back to normal? Because all I wanted was to get back to work and get back to normal. So, coming to the first gym session I thought great, this is the road back to it.” (Male) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Staffing | Programme effectiveness | “I would recommend the programme, it works!” (Male) |

| “Go and see your GP and get yourself referred to you.” (Female) | ||

| Transformative impact | “Its life changing! it’s changed my life, literally, has changed my life!” (Female) | |

| “It worked and more because I’m definitely better than what I was before. I am not just where I was before I had COVID I am better than I was before I had COVID.” (Female) | ||

| Hope and encouragement | “It’s not hopeless. You can refer to the programme, and it will really help you.” (Female) | |

| “It felt like the isolation was ended. Finally going to be able to see people, so, light at the end of the tunnel as a kind of overall theme.” (Male) | ||

| Community and shared experience | “Be aware that there are other people like this as well. You’re not just on your own.” (Male) | |

| Staff skills, expertise, and attributes | “Your expertise on how your body works and how you can make yourself feel better. It has an educational element to it as well.” (Female) | |

| “I was scared, but I think it was a friendly, smiley positive person once you arrived.” (Female) | ||

| “They (instructors) believed in you. It wasn’t like you must do this course. But actually, we know you have LC, it was believing you.” (Female) | ||

| “You were put at ease pretty much straightaway.” (Male) | ||

| “It was just nice to have that, just that one person, who knew me. You know, a friendly face.” (Female) | ||

| Group setting | Power of shared experience in building social connection and overcoming self-consciousness | “If we had met each other before, you’d build that natural support, wouldn’t you? You know how we were all in exactly the same position. So, you know, you wouldn’t feel kind of that barrier between me and you, and you’d probably be like, actually, I don’t mind doing the gym session with someone else.” (Female) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Areas for improvement | Social connection and support | “It would have been nice to meet everybody earlier on, just for emotional support, I guess as well. I was on my own. Nobody else had got it (LC), and it would have been so helpful if I knew everyone here and, you know, just talked, I’ve had a rubbish day I’m exhausted, someone to understand.” (Female) |

| “A group session to start, would give you an opportunity to meet people. Chances are we probably would have all started a WhatsApp group then anyway.” (Female) | ||

| “I think it would have been nice to meet everybody at the beginning. And then we could swap numbers and meet at the gym.” (Female) | ||

| “That initial group session would open up more opportunity, and possibly more opportunities to help others more.” (Female) | ||

| “So, we could go for a walk around somewhere and then have a coffee after. I think if I’ve made plans, or you’d arranged to meet with somebody then you’re more likely to and will. And they’ve gone through what you’ve gone through.” (Female) | ||

| “Because, like, when the four of us did meet up so at the halfway point, when we were here for the TV cameras on Midlands Today, I think it was good because it was just sitting, talking very informal. And we talked about it (LC). We did a bit of networking, tying us together, that would have been good then.” (Male) | ||

| Maintenance of activity levels | Motivation and accountability | “I think if I could meet with somebody at the gym I would go, I would go more.” (Female) |

| Staff communication | Handover of exercise prescription between staff | “The only thing I wanted to mention is that sometimes the contact across different staff members wasn’t ideal. So, it was different guys, each different, but all good! So, everybody’s different. But it was just when I come to have X trainer he massively underestimated where I was.” (Female) |

| “I think if X trainer had of looked at my programme a little bit more and we’re on the same level. I think X trainer could have brought in quite a bit more. And I was getting a little bit bored. And where was I was used to having Steve who used to really push me (laughs).” (Female) | ||

| Maintaining progress after programme completion | Post-programme exercise plan | “We would like a proper plan of exercise for us to do when we’ve finished the programme. Something we can do in our particular gym.” (Male) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Improved quality of life | Transformation through progress | “I feel like I’ve really made progress. And I’m not exhausted anymore. I’m going to ski school in March which I never thought I’d be able to do; learn to ski. I’m working three days a week now and taking on more responsibility at work. Problems are not so overwhelming anymore.” (Female) |

| “For me it just got my breathing back, and my mental health back to normal.” (Female) | ||

| “At the beginning I didn’t think it would do any good for me. But at the end of it you know, I would say definitely give it a go. It’s like if you have to have counselling. People say oh, you know, I don’t think that will work for me, but I think you have to go and give it a try and see what you get from it.” (Female) | ||

| “I just want to say that even though I wasn’t as bad as the others I found it to be life changing” (Male) | ||

| Physical Improvements | “The programme itself made me feel so much better! All my aches and pains just feel so much better” (Female) | |

| “I am loads better.” (Male) | ||

| Impact on daily life | “You must remember what life was like before this. It’s like what you said right at the start, is this the new normal. I just feel so much better. But geneally, I feel well, I couldn’t have said that at the start of the programme.” (Female) | |

| Hope for recovery | “I think it would be interesting. If we hadn’t done the programme, would we still be in that position where we were before? And we would have just settled for thinking this is our life now. Just thinking about it really upsets me, it really does.” (Female) | |

| “I think it gives you it gives you a lot of hope for the future. For me it did.” (Female) | ||

| “Well, I can remember when I had my own kids, I used to lift them up to ride on my shoulders. So, when I got PCC, we were walking down to the next village where we live, and I was taking the grandkids down. And I remember I struggled to carry them, I had to put them down. But now picking them up again is fine.” (Male) | ||

| Recognised importance of self-care | “Being aware of self-care, being aware in the past I’ve just carried on with my master’s degree and picked up extra days at work and just run myself into a hole. Now I know I need to just spend some time looking after myself.” (Female) | |

| Assertiveness and self-care | “So, if I don’t want to do something I am not doing it. Normally I would just be a people pleaser, but I don’t need to do it. I have got a lot better at saying no. I think that has come from part of being on this programme.” (Female) | |

| Increased self-esteem and self-efficacy | “I have been able to publicly speak which is something I’ve never been able to do. My most recent talk was at a church a few miles away. I talked about sustainability, and I did some flower arrangements. And again, talking about my COVID journey. I mean, just inspiring really with what I have done, you know, I was very, very ill and the fact that I’m doing this, that’s a positive for me, you know.” (Female) | |

| Improved mental health | “I just thought I don’t have time for it, I don’t want the drama. I just really want to enjoy my life. I remember, coming back to these meetings makes me think back to that time. I don’t want to go back to that time. When I was incredibly ill, and I thought was going to die! I’m not going to lie I thought was going to die and sometimes I go back to that and then I just don’t want any of this reality and drama. A lot of that comes from the fact that we just use the darker, horrible things we’ve experienced that not really many people understand.” (Female) | |

| “Exercise is great for that. I think we all must find what we like. I like being outside in the garden and just sitting there in the fresh air.” (Female) | ||

| Shifting priorities | “Being active as become more at the forefront.” (Male) | |

| Taking ownership of health | “I eat well, drink, all the things you used to advise. And then I feel better.” (Female) | |

| Exercise to support mental health | Mind–body-connection | “Mentally I know that I have to do some exercise now. If I don’t do any exercise my brain struggles. I have to do something; I have to go to the gym. I need to go for a walk, I need to do something. Otherwise, I can spiral downwards and make myself feel quite low.” (Female) |

| Self- management | Relapse | “Once we were on the programme, my sleep improved with going to the gym, and doing things because it made me go out and make me do things. That helped massively! It seemed to lapse a bit through the summer. I’m really able to push myself to get back there now. Pick up elements that we did on the programme and try and keep those implemented.” (Male) |

| Overcoming adversity | Connection and perseverance | “When I was off work for months, I started growing flowers for my well-being and now I do talks to help others about my personal COVID journey, and how it helped me to grow flowers. I think I would have just lost myself because I was so ill. I had the vicar come to see me with the last rights, and he’s a bit of a joker and he said, oh, I’d love to do your funeral. And I think that was the turning point for me. I said you’re not taking me! And it’s the flowers that kept me going. I saw them as my seed bed if you like, to watch them grow. That was stimulating and my focus in life a bit selfish. I’ve got to keep them alive to keep going. And as they grow it just gave me something to keep going.” (Female) |

| Maintaining motivation | “And that’s why now, when I do the talks and things you know it’s since this, there will be a light at the end of the tunnel. Don’t give up, believe in yourself, and just keep going. And I think that’s why I push myself hard now, because I don’t want to go back to that dark place.” (Female) | |

| Focus Groups | Social support | “These meetings do help, but I think it would have really helped if I had met everybody I think right at the start. So, we can talk to each other for support as well, so you know you’re not going mad. That would have been really helpful.” (Female) |

| “It was an eye opener to see that you had got other people in the gym at the same time who had got the same problems as me.” (Male) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers to Gym Attendance | Logistics | “So, it’s kind of a lack of time, and travel. The distance and just the fact that I am not working locally anymore.” (Female) |

| Inconvenient location | “I did sign up to the gym, but because I was working part time and going to the gym in Burton, and I live in Stafford. I would go on my lunch break, or I would try and go here and there, and all through the summer. But since I have dropped down to part time at work, I just hardly come to Burton anymore.” (Female) | |

| Routine | “We are trying to throw everything into our business, and I just have no routine.” (Male) | |

| Alternative Physical Activities | Importance of enjoyment | “I don’t go to the gym anymore, but I think it’s because I get really bored on my own. It’s good if you have someone there to push you on. But I’m just walking the dogs regularly, doing lots with the kids, taking the kids on bike rides, you know, getting on with things to try to build into my day-to-day life.” (Female) |

| “So, we started going out on our bikes with little one. I also park further away from our shop so, I had to do a 10 min walk every day.” (Male) | ||

| Self-Care Prioritisation Challenges | Change in priorities | “I think I have gone back to how I was pre-COVID that everyone else is my first priority. I need to make sure everyone else is okay first, before me.” (Female) |

| Value of Social Support | Spending time with friends | “It’s like a support away from your family and all that. People who haven’t got LC. It lifts your spirit. Makes you feel good, having a laugh.” (Male) |

| Home-based exercise | “So, perhaps producing some sort of guide maybe, with stuff that you could do at home, exercises at home.” (Male) | |

| Impact of Programme Timing | Referral pathway | “I just wish that I could have got on the programme a lot sooner. I think it would have helped a lot sooner and I think I would have felt a lot better sooner because it was two years before I got on the programme.” (Female) |

| Prioritising and maintaining self-care | Loss of external support and accountability | “On the programme you would have the instructors keep reminding us we need to prioritise our own health first. But now, I’ve got no one. No one I’m accountable to as such, I am accountable for myself.” (Male) |

| Theme | Sub-Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Routine and goal setting | Maintaining social interaction | “You know, having PCC thinking is this what life is going to be like now. I’m not going to get back to normal. The programme helps get back to normal. And the fact of going out twice a week helped me massively because it was written down. I’ve got to be there at nine o’clock on a Tuesday morning. I knew that it was almost like a non-negotiable to me that, so I had to do it and I’m almost having to set myself my negotiables now that I am finished on the programme. I must talk to three different people. I have to set these soft targets like that to make sure I do.” (Male) |

| “It just makes you feel valued. That if I weren’t around people would miss you and it just lifts you, even more. It’s great for your own self-worth.” (Female) | ||

| Prioritising and maintaining self-care | Internal conflict between self-care and family obligations | “With everything that’s going on, and again, this is just one thing, I’ve started to put myself a little bit down the list of priorities in terms of where I fit. Because I’ve got to make sure my parents are alright, my boys are alright.” (Male) |

| Boundaries and self-care | “Putting boundaries in place and saying actually that if I just keep working, I am no good to anybody. So, you need to have a break and a means of tracking to put things away, so that you dedicate time to having fun with friends and family.” (Female) | |

| The societal pressure to prioritise others over self-care | Internal conflict between self-care and societal expectations | “It’s all about you, it’s all about yourself and we want to be seen to be pleasing people. At home I look after my partner and our animals. So, I think we’re all creatures where we always put ourselves last in terms of priorities. Then we’ll just make time to go for a haircut or grab a coffee every now and whenever you can. So, it’s not your priority, is it? If it is your priority, if it would seem to be a priority, I think people are quick to say oh, she’s having her nails done, she’s having her hair done blah, blah, blah. But really, we should all be doing that as well. We should all be able to do our own thing because I’m not okay.” (Female) |

| Mental and emotional impact of post-COVID condition | The challenge of managing panic attacks and anxiety | “When you are that ill, all you are concentrating on is trying to get through that day. If you’re having a panic attack, you’re just sitting there praying, like literally praying that you’re going to get through the next hour.” (Female) |

| Cognitive difficulties | ||

| “I never used to carry anything. And now I’ve got notebooks I’ve got post- it notes in this pocket, there’s also a pen in this pocket. So, the most compulsive behaviour that I’ve gotten is to have all these things with me, because otherwise I won’t remember it.” (Male) | ||

| “I asked the doctor about it, and he said do you know when you’re doing it? And I said yes. And he said good, because it’s when you don’t know you’re doing it you need to worry.” (Female) | ||

| “Mine is up and down at the moment. It’s like with the brain fog, I have had that come back again. My manager always says to me why have you got a paper diary. I need it for my calendar, I always fill that in. I have to write everything down.” (Female) | ||

| “I think when you’ve got brain fog as well, sometimes it’s hard to think about routine because you can’t think about what to do first. Even the simplest task. I have struggled this week, I have got out of bed, got dressed, made my bed, and then I think should I brush my teeth now or later. My brains going like, what do I do first”? (Female) | ||

| “That’s what pretty much finished me off when I was teaching fractions. I was at the blackboard, and I couldn’t remember, and my mind just went blank. I mean even now with my youngest son, he’s only eight years old, and we play memory games or do jigsaws and I just struggle. I got in the car to drive to Ikea, and I was going completely the wrong way on the M6 in the opposite direction.” (Male) | ||

| “It’s more when I get stressed or flustered and then it goes totally. I mean working in the shop is helping by making me talk to people and get that back, but I’ll pick up some material or I can get a price for something and then I will get to the till, and I will have forgotten what that price was. But then I feel silly and stupid and ridiculous. Because you can’t do that.” (Male) | ||

| “I kind of laugh it off. I’m quite happy myself, anything that happens like that. I just brush it off. It doesn’t bother me.” (Male) | ||

| Fear of missing out and overexertion | “I feel like I don’t want to stop and think so I just keep on pushing on. I have blocked in loads of things to do with the kids that we would never normally do, because I just do not want to stop. So just keep going. And it’s like, one of the things that’s happened with me since having LC and being in hospital is that I do not want to say no to opportunities, because I’ve got a lot of doorways open. There’s lots of opportunities. And when you think you’re not going to have any opportunities, it’s nice to have opportunities. But that’s when the self-care boundaries kick in and actually, let’s just make sure I am okay.” (Female) | |

| “I have had a lot of mood swings going up and down a lot recently, because I couldn’t think of that, I used to be on my knees praying before I go to bed a night. And I think that’s what I’ve had over the recent few weeks again. I might have had COVID again and not known it.” (Female) | ||

| Importance of healthy eating | Adopting healthy eating habits | “Since the programme finished; I have realised I need to eat properly. More vegetables eat more healthfully. So that has been more of a challenge. And that has been a focus for us, when we do eat properly, we feel better for it.” (Male) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rimmer, S.; Herbert, A.J.; Kelly, A.L.; Khawaja, I.; Lee, S.; Gough, L.A. A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Post-COVID-Condition Rehabilitation and Recovery Intervention Delivered in a Football Club Community Trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111672

Rimmer S, Herbert AJ, Kelly AL, Khawaja I, Lee S, Gough LA. A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Post-COVID-Condition Rehabilitation and Recovery Intervention Delivered in a Football Club Community Trust. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(11):1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111672

Chicago/Turabian StyleRimmer, Steven, Adam J. Herbert, Adam L. Kelly, Irfan Khawaja, Sam Lee, and Lewis A. Gough. 2025. "A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Post-COVID-Condition Rehabilitation and Recovery Intervention Delivered in a Football Club Community Trust" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 11: 1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111672

APA StyleRimmer, S., Herbert, A. J., Kelly, A. L., Khawaja, I., Lee, S., & Gough, L. A. (2025). A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of a Post-COVID-Condition Rehabilitation and Recovery Intervention Delivered in a Football Club Community Trust. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(11), 1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22111672