Abstract

Research demonstrates associations between oral health and specific mental health conditions in the general population, yet these relationships remain understudied during pregnancy, despite pregnancy’s profound effects on both oral and psychological well-being. Our rapid review examines current evidence on associations between oral health conditions and psychological states (anxiety, depression, and stress) during pregnancy, aiming to inform and strengthen integrated prenatal care strategies. Following PRISMA-RR guidelines, we conducted a systematic search on OVID Medline, CINAHL, and PsycINFO (January 2000–November 2024) for studies examining relationships between oral health conditions (periodontal disease, dental caries) and psychological status during pregnancy and up to one year postpartum. Systematic screening of 1201 records yielded 22 eligible studies (13 cross-sectional studies, 3 longitudinal cohort studies, 3 comparative studies, 2 prospective studies, and 1 case–control study). Analysis confirmed significant associations between oral health and psychological well-being during pregnancy through three pathways: psychological (dental anxiety directly limits oral healthcare utilization), behavioral (maternal depression reduces oral health self-efficacy), and physiological (elevated stress biomarkers correlate with periodontal disease, and periodontal therapy is associated with reduced salivary cortisol). These interactions extend intergenerationally, with maternal psychological distress showing significant associations with children’s caries risk. Evidence suggests interactions between oral health conditions and psychological states during pregnancy, warranting integrated care approaches. We recommend: (1) implementing combined oral–mental health screening in prenatal care, (2) developing interventions targeting both domains, and (3) establishing care pathways that address these interconnections. This integrated approach could improve both maternal and child health outcomes.

1. Introduction

Pregnancy causes major physiological and psychological changes that significantly affect oral and mental health [1]. Hormonal changes during pregnancy increase the risk of periodontal diseases, with gingivitis affecting 30–100% of pregnant individuals across different populations [2,3]. These changes occur through well-documented biological mechanisms, including increased levels of progesterone and estrogen that alter the inflammatory response and modify the oral microbiome composition [4]. The relationship between oral health and psychological well-being during pregnancy appears to operate through multiple pathways [5]. Current evidence suggests three primary mechanisms: (1) neuroendocrine pathways, where stress hormones like cortisol affect immune function and inflammatory responses [6,7], (2) behavioral pathways, where psychological distress impacts oral hygiene practices and healthcare utilization [8], and (3) immune–inflammatory pathways, where psychological stress modulates immune responses and periodontal inflammation [9,10].

A systematic review and a scoping review have highlighted the urgent need to integrate oral health into prenatal care [11,12]. Specific psychological challenges, including anxiety and depression [13], also increase during this period, with professional guidelines recommending integration of psychological assessment and support into routine prenatal care to address this increased psychological vulnerability [14]. While associations between oral health and psychological well-being are established in the general population [15,16,17], research examining these relationships during pregnancy remains limited. Recent evidence examining oral microbiome patterns in pregnancy found associations between oral bacterial communities and maternal anxiety and depression levels [18], suggesting biological mechanisms may exist, but studies investigating clinical oral health outcomes are sparse. This knowledge gap hinders effective care integration at a time when both domains undergo significant changes.

Understanding the relationship between oral and psychological well-being during pregnancy is particularly crucial given that socioeconomic factors often limit access to both oral and mental health care, perpetuating health inequalities [19,20,21]. If an association exists during pregnancy, identifying oral health issues early may serve as an indicator of overall health and potential psychological risks. While psychological screening is now more common in prenatal care, oral health assessment varies even though recommendations support its inclusion [11,12]. The consequences of failing to understand and address these interconnections may include adverse pregnancy outcomes. Research has shown associations between poor oral health and preterm birth, low birth weight, and increased risk of maternal complications [22,23]. Furthermore, poor oral health during pregnancy has been associated with increased inflammation and systemic health issues [24,25] while untreated psychological conditions can impact prenatal care adherence, nutrition, and overall maternal well-being [26,27]. Understanding these relationships could strengthen the case for comprehensive prenatal oral health screening, potentially improving both maternal psychological health and pregnancy outcomes [2,13].

To address this evidence gap, the team conducted a rapid scoping review which allows for timely decision making. This review examines the relationships between oral health and specific psychological conditions (depression, anxiety, and stress) during pregnancy, including underlying mechanisms and implications for integrated care delivery. The findings will inform the evidence-based integration of oral health screening into prenatal care and establish a foundation for developing comprehensive approaches that address both oral and psychological needs during pregnancy [28].

2. Materials and Methods

This rapid review follows the guidelines outlined in the Rapid Review Guidebook [29] and utilizes the PRISMA-RR checklist [30] to synthesize evidence. The decision to conduct a rapid review rather than a systematic review was based on several factors: (1) the need to provide timely evidence synthesis for clinical practice decisions, (2) the emergence of new evidence in this field requiring regular updates, and (3) the focused nature of our research question. While maintaining methodological rigor, this approach allowed completion within 12 weeks to inform time-sensitive practice and policy decisions.

2.1. Research Framework

The investigation and search strategy development were guided by the Population, Concept, Context (PCC) framework [29]. The study included pregnant women at any stage of gestation and women up to one year postpartum in various healthcare settings. The researchers examined oral health conditions (specifically periodontal disease and dental caries) alongside specific psychological conditions (anxiety, depression, and stress-related outcomes). The context addressed prenatal and postnatal care in healthcare settings globally from January 2000 to November 2024. The framework was defined as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Research Framework.

2.2. Search Strategy

The researchers conducted comprehensive searches between 27 August and 6 September 2024, in OVID Medline, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases. The search strategy used the following key concepts and related terms:

- Pregnancy/postpartum terms: “pregnant”, “pregnancy”, “antenatal”, “perinatal”, “prenatal”, “postpartum”, “postnatal”;

- Oral health terms: “oral health”, “dental health”, “periodontal disease”, “gingivitis”, “dental caries”, “tooth decay”;

- Psychological terms: “anxiety”, “depression”, “stress”, “psychological distress”, “mental health”;

- Healthcare setting terms: “prenatal care”, “antenatal care”, “maternal health services”.

These terms were combined using appropriate Boolean operators and adapted for each database’s specific requirements. The researchers supplemented database searches with a Google Scholar search, examining the first 200 results using modified search strings adapted for the platform’s search capabilities. Appendix A presents the full search strategy for OVID Medline.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Studies qualified for inclusion by examining pregnant populations at any gestational stage or within one year postpartum and by investigating oral health conditions and specific psychological conditions (anxiety, depression, and stress). Observational studies, including cohort, case–control, and cross-sectional designs, along with interventional studies such as randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental designs, were included. Furthermore, the team considered systematic reviews and meta-analyses that addressed the research questions. All studies reported quantifiable outcomes in peer-reviewed English-language journals from January 2000 onwards. Studies were excluded if they: (1) focused solely on non-pregnant populations, (2) examined oral health or psychological conditions in isolation, (3) used non-empirical methodologies including qualitative studies, or (4) did not report specific measurable outcomes for both oral health and psychological conditions.

2.4. Study Selection

Two independent reviewers (AA, SR) conducted the screening process using Covidence (2022 software) [31]. The process involved initial title screening, followed by abstract review and full-text assessment against eligibility criteria. The reviewers resolved all disagreements through structured discussion, achieving consensus without requiring third-party arbitration. Covidence software maintained a complete audit trail of screening decisions and exclusion reasons.

2.5. Quality Assessment and Data Analysis

While rapid reviews often modify quality assessment procedures to meet time constraints, we maintained methodological rigor by conducting comprehensive data extraction and synthesis; using standardized data extraction forms; employing dual review for key decisions and maintaining transparent documentation of all methodological choices. This approach allowed for thorough analysis while meeting the 12-week completion timeline necessary for informing current practice needs.

2.6. Data Extraction

The team developed and pilot-tested a standardized data extraction form to ensure comprehensive and consistent data collection. One reviewer extracted data from all included articles. The form captured bibliographic information, study characteristics such as design, setting, and sample size, participant demographics, interventions or exposures, outcome measures including primary and secondary measures, key findings related to oral–mental health relationships, and study limitations.

2.7. Data Synthesis

The narrative synthesis adhered to the guidelines set forth by Popay et al. (2006) [32], organizing the findings into four sequential steps. The researchers characterized the included studies by examining their research design, methodological approach, and population characteristics. Next, the team analyzed assessment methods for both oral and psychological health measures, examining the validity and reliability of the measurement tools. Third, the team synthesized findings across three key domains: the prevalence of concurrent oral–mental health conditions, the pathways linking oral and mental health outcomes, and the effectiveness of interventions. The researchers identified research gaps and methodological limitations in the current evidence base. The structured approach allowed for systematic evidence synthesis, even with significant differences in study designs and outcome measures.

2.8. Study Limitations

The rapid review methodology required a few adaptations from conventional systematic review approaches. The team prioritized comprehensive data extraction and synthesis, focusing on urgent practice needs while ensuring methodological rigor was maintained over formal quality assessment. The restriction to English-language studies may have led to the exclusion of relevant international research, while the compressed timeframe constrained the depth of analysis achievable for each study. However, this approach aided the feasibility of this rapid review. The limitations informed the interpretation of findings and shaped recommendations for future research.

2.9. Ethical Considerations

Being a rapid review of literature, the review did not require formal ethical approval, yet thorough research integrity standards were upheld throughout the process. Clear reporting and thorough data extraction received focused attention. The team integrated patient-centered outcomes to demonstrate their commitment to relevant and applicable findings. The researchers incorporated patient priorities from existing literature into their research questions and outcome measures, ensuring the review’s relevance to clinical practice.

3. Results

The rapid review revealed compelling evidence for associations between oral health conditions and psychological states (anxiety, depression, and stress) during pregnancy, manifesting through behavioral, physiological, and intergenerational pathways.

3.1. Study Characteristics

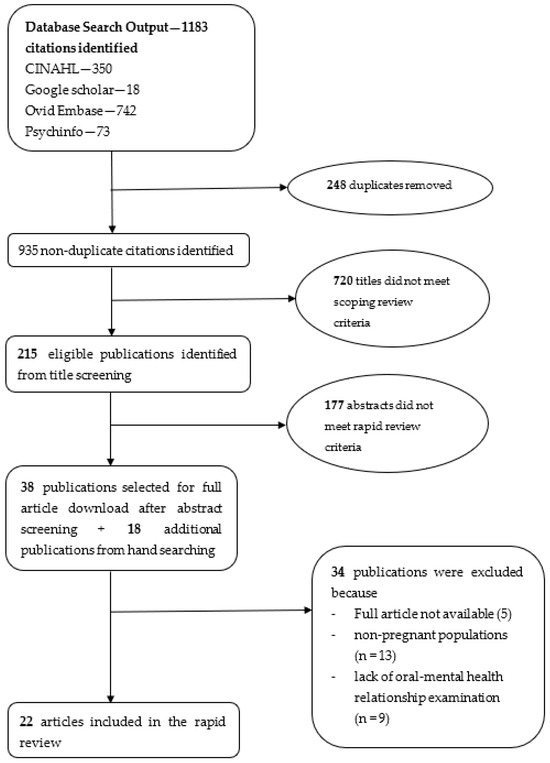

From 1201 records (1183 database searches, 18 hand-searched), 22 studies met inclusion criteria with most studies (n = 14) published after 2020. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram detailing our search and selection process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Chart for the Scoping Review.

The characteristics and findings of included studies are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3. Most studies employed cross-sectional designs (59.1%) and were predominantly conducted in the Middle East (31.8%) and North America (22.7%). Detailed study characteristics and findings are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of Included Studies by Design and Geographic Region.

The studies varied in their focus populations, with most targeting pregnant women exclusively, while some included comparative groups of non-pregnant women or extended to mother–child pairs. Sample sizes ranged from 46 to 790,758 participants: thirteen studies had fewer than 500 participants [7,9,10,13,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], eight studies included 500–2500 participants [41,43,44,45,46,47,48,49], and one large cohort study analyzed 790,758 mother–child pairs [50]. The most recent studies (2021–2024) showed a trend toward larger sample sizes, with five of the eight studies from this period including more than 500 participants [43,44,45,46,48,50].

Table 3.

Characteristics and Key Findings of Studies Examining Oral Health and Mental Well-being During Pregnancy.

Table 3.

Characteristics and Key Findings of Studies Examining Oral Health and Mental Well-being During Pregnancy.

| Author(s) and Year | Location | Study Design | Sample Size | Population Characteristics | Oral Health Measures/Scales | Mental Health Measures/Scales | Key Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| An et al. (2024) [48] | West Virginia and Pittsburgh, USA | Longitudinal | 1172 | Pregnant women | Self-reported toothbrushing and flossing frequency questionnaire | GEE approach for depression and stress assessment | Depression and stress negatively related to oral self-care | Self-reported measures |

| Gastmann et al. (2024) [36] | Brazil | Prospective | 60 | Pregnant and non-pregnant women needing root canal | Numerical pain scale (NPS); clinical assessment of dental pain | Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS); Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) | No difference in pain, anxiety between pregnant/non-pregnant women | Limited pain assessment |

| Gokturk et al. (2024) [37] | Turkey | Comparative | 87 | Pregnant and non-pregnant women with/without gingivitis | Plaque index (PI); gingival index (GI); probing pocket depths (PPDs); GCF samples | Salivary cortisol levels; stress hormone analysis (ELISA) | Periodontal therapy improved stress markers in non-pregnant women only | Small sample size |

| Nazir et al. (2022) [46] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 780 | Pregnant women | Dental attendance records | GAD-7; Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) | Highest anxiety in third trimester | Self-reported data |

| Kim et al. (2022) [45] | Korea | Cross-sectional | 1096 | Pregnant women aged 19–55 years | Subjective oral health status questionnaire | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) | Higher subjective oral health status associated with decreased depression | Limited psychological factors |

| Cademartori et al. (2022) [44] | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 2496 | Pregnant women from birth cohort | DMF-T index; self-perceived oral health questionnaire | Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) | Dental caries’ effect on depression mediated by oral health self-perception | Limited to specific cohort |

| AlRatroot et al. (2022) [43] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 825 | Pregnant women from hospitals | WHO Oral Health Survey; dental attendance patterns | Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) | 90.9% prevalence of dental anxiety | Limited geographic region |

| Alhareky et al. (2021) [33] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 199 | Mother–child pairs | dmft/DMFT indices (WHO criteria) | Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) | Higher maternal anxiety associated with more child caries | Small sample size |

| Yarkac et al. (2021) [39] | Turkey | Comparative | 60 | Pregnant and non-pregnant women with gingivitis | Periodontal indices (PI, GI, PPD); GCF samples | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | Worse periodontal outcomes in pregnant women | Small sample size |

| Auger et al. (2020) [50] | Quebec, Canada | Longitudinal cohort | 790,758 | Mother–child pairs in Quebec | Childhood dental caries (ICD codes) | Maternal mental disorders (diagnostic codes) | More caries in children of mothers with mental disorders | Administrative data limits |

| Ahmed et al. (2017) [40] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 438 | Pregnant women | Oral health problems self-report checklist | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) | 33.4% high perceived stress | Self-reported measures |

| Luo et al. (2017) [41] | China | Cross-sectional | 502 | Pregnant women from outpatient clinic | Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14) | Dental anxiety questionnaire | 26.7% had dental anxiety; negative correlation between dental anxiety and oral-health-related quality of life | Self-reported measures |

| McNeil et al. (2016) [49] | Northern Appalachia, USA | Cross-sectional | 681 | Caucasian pregnant women | Gingivitis scale; ORI; DMFT index | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) | Depressed women had poorer oral health | Limited to Caucasian women |

| Park et al. (2016) [38] | South Korea | Cross-sectional | 129 | Pregnant women | Community Periodontal Index (CPI) | Depression scale; stress scale | Periodontal disease associated with stress, depression | Small sample size |

| Seraphim et al. (2016) [7] | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 96 | Pregnant women at 5–7 months’ gestation | Community Periodontal Index (CPI) | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS); salivary cortisol | Higher perceived stress in periodontitis/gingivitis groups | Limited public health system data |

| Silveira et al. (2016) [13] | USA | Cross-sectional | 402 | Pregnant women | Self-reported tooth loss; dental visit frequency | PHQ-8; self-reported anxiety/depression diagnosis | 3.30 times greater odds of tooth loss with anxiety | Self-reported data |

| [9] Gümüş et al. (2015) [9] | Turkey | Case–control | 187 | Pregnant, postpartum, controls | Periodontal disease severity indices | Oxidative stress markers | Higher oxidative stress in pregnant women | Clinical value not evaluated |

| Tolvanen et al. (2013) [42] | Finland | Longitudinal | 254 | Pregnant mothers and fathers | Modified Dental Anxiety Scale | EPDS; Anxiety Subscale SCL-90 | Dental fear increased over pregnancy | Not specified in data |

| Yarkac et al. (2018) [10] | Turkey | Comparative | 60 | Pregnant and non-pregnant women with gingivitis | Plaque index; gingival index; GCF samples | Salivary chromogranin A (CgA); ELISA | Periodontal therapy improved status in both groups | Limited stress markers |

| Arteaga-Guerra et al. (2010) [34] | Colombia | Observational | 46 | Pregnant women | Periodontal examination protocol | Stress scale | Combined periodontitis and stress increased LBW risk | Small sample size |

| Esa et al. (2010) [35] | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 407 | Antenatal mothers | D(3cv) MFS (dental decay) index | Dental Fear Survey (DFS) | Positive association between anxiety and decay | Single examiner bias |

| Horton et al. (2010) [47] | USA | Prospective cohort | 1020 | Pregnant women <26 weeks | Periodontal disease classification | Not specified | No evidence of oxidative stress mediation | Limited 236–266 longitudinal data |

DMFT: Decayed, Missing, Filled Teeth; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; GCF: Gingival Crevicular Fluid; MDAS: Modified Dental Anxiety Scale; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; WHO: World Health Organization; CPI: Community Periodontal Index; ORI: Oral Hygiene Index.

3.2. Assessment Methods

Psychological status assessment utilized validated instruments including the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) [33,43,46], Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [42], and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8/9) [13,45]. Studies measuring stress utilized the Perceived Stress Scale [7,40] alongside biological markers such as salivary cortisol [7,9]. Oral health evaluation combined clinical examinations using DMFT indices and WHO criteria with self-reported measures [51]. Most studies (n = 15) used validated mental health scales, while oral health assessment methods showed greater heterogeneity, ranging from comprehensive clinical examinations to basic self-report questionnaires.

3.3. Behavioral Pathways and Access Barriers

Dental anxiety emerged as a significant barrier to oral healthcare use, affecting 90.9% of pregnant women in one study [43] and significantly reducing dental attendance [13]. Dental anxiety’s effects emerged through three mechanisms: (1) direct effects on behavior: women who experienced anxiety showed almost three times greater odds of avoiding dental care [13], (2) psychological amplification: depression was associated with lower oral health self-efficacy (β = −0.28, p < 0.001) and heightened dental anxiety (β = 0.47, p < 0.001) [48], and (3) effects mediated by stress: stressful life events led to an increase in both poor oral health (OR: 1.56) and unmet dental needs (OR: 1.86) in one study [52].

3.4. Physiological Mechanisms

Several studies demonstrated associations between oral health and stress responses [7,10,37]. The findings included correlations between elevated blood glucose and insulin resistance in pregnant women with periodontitis [7] and higher oxidative stress markers in pregnancy-associated gingivitis [37]. Evidence also indicates associations in treatment outcomes as periodontal therapy was associated with reduced inflammation and stress markers [10]. Pregnancy-specific modifications to inflammatory responses, evidenced by differential treatment outcomes in pregnant versus non-pregnant women, were also reported [10].

3.5. Intergenerational Transmission

Data suggested associations between maternal oral–psychological status and child health outcomes [33,50]. A retrospective cohort study (n = 790,758) examining children from birth to age 12 revealed an association between maternal psychological conditions and increased caries risk in children, with a cumulative incidence of 62.9 per 1000 children for maternal psychological conditions versus 31.4 per 1000 for no maternal disorder by age 12 [50]. Another study reported correlations between maternal dental anxiety and children’s untreated decay [33].

3.6. Research Gaps and Limitations

The reviewed studies present several methodological limitations that affect the interpretation and generalizability of findings. The predominance of cross-sectional designs [13,41,49] limits our understanding of causal relationships between mental health and oral health outcomes during pregnancy. Only three studies [42,48,50] used longitudinal approaches and none used qualitative approaches. The wide variation in sample sizes creates challenges in comparing findings and establishing reliable effect estimates. Geographic concentration on specific regions, particularly Saudi Arabia [43,46] and the United States [13,49], also limits global applicability of the findings. Methodological heterogeneity further complicates the synthesis of evidence. While some researchers used validated instruments such as MDAS [43,46], others relied on non-standardized or self-reported measures [40,41]. Studies investigating biological markers also typically involved small samples [7,10] and rarely included clinical oral health examinations, relying instead on self-reported oral health status [41].

4. Discussion

The rapid review reveals compelling evidence for bidirectional associations between oral and psychological states (anxiety, depression, and stress) during pregnancy, highlighting significant implications for maternal and child health outcomes [1,2]. Three primary mechanisms emerge from the evidence. First, biological mechanisms play a crucial role where stress hormones (particularly cortisol) modulate immune responses and gingival inflammation [7,10]. Psychological stress affects oral immune function and wound healing [9], while periodontal inflammation shows reciprocal relationships with systemic stress responses [7,10,39]. Importantly, pregnancy hormones may amplify these biological interactions [2,3].

Second, behavioral mechanisms significantly influence outcomes. Dental anxiety acts as a barrier to seeking dental care [13,35,36,41,43,46], while depression reduces oral health self-efficacy and self-care behaviors [11,13]. Stress impacts adherence to oral hygiene routines [53], creating a cycle of deteriorating oral health [19,20,21]. Third, psychosocial mechanisms underlie many observed relationships. Social determinants affect access to both dental and psychological care, while cultural factors influence care-seeking behaviors [54]. Economic barriers often limit access to preventive services, exacerbating health disparities [19,20,21]. These findings extend current understanding beyond previously established general population links in the general population [17,55] and highlight pregnancy as a critical period for integrated healthcare interventions.

The biological relationships between periodontal conditions and stress biomarkers [7,9,10,39] provide biological plausibility for oral–mental health interactions during pregnancy. This is further supported by recent microbiome research showing distinct oral bacterial profiles in pregnant women with different levels of anxiety and depression symptoms [18]. Studies suggest that periodontal therapy on oral health parameters and stress markers indicate potential therapeutic benefits that extend beyond the improvement of oral health [10]. The modified inflammatory responses observed in pregnant women indicate a need for treatment protocols that are specific to pregnancy [56]. The study findings align with evidence suggesting associations between periodontal health and pregnancy outcomes [2] and suggest that oral health interventions could provide multiple benefits during pregnancy.

The evidence for intergenerational transmission of oral health risks is particularly compelling [33,50]. Research suggests associations between maternal psychological conditions and increased risk of caries, indicating that pregnancy serves as a crucial intervention window for breaking cycles of poor health outcomes. This risk is further amplified by direct bacterial transmission mechanisms, where cariogenic bacteria are more readily transferred from mothers with untreated decay to their children [57]. Studies have demonstrated specific maternal–child bacterial colonization patterns [58], emphasizing the importance of both preventive and operative dental care during pregnancy to reduce children’s future caries risk. This finding extends previous research on the relationships between maternal and child oral health [3] and provides additional justification for the integration of oral health into prenatal care [11,12].

Implications for Practice

For effective implementation of integrated care, we recommend several key approaches. Enhanced communication and health literacy form the foundation of improved care delivery [59,60]. This includes developing culturally competent communication strategies, providing oral health education in accessible formats, and building trusting, non-judgmental provider–patient relationships. Provider training in effective communication techniques is essential for successful implementation [61]. Furthermore, community-based approaches represent another crucial element of integrated care. Integration of community health workers into care teams leverages their cultural and linguistic competencies [62]. These workers can utilize existing community networks for health education and help establish community-based support systems that enhance care delivery and outcomes.

Healthcare providers should implement combined oral–psychological health screening during routine prenatal visits [14,15]. This approach facilitates early identification of interrelated conditions and enables timely intervention. Healthcare professionals’ comprehensive interprofessional education begins in their foundational training programs. This should include joint learning opportunities where dental, medical, nursing, and mental health students train together to understand the interconnections between their disciplines and develop collaborative care approaches.

Implementation of integrated care requires both structural and cultural changes. Healthcare systems should invest in shared electronic health records and care coordination platforms that facilitate communication between providers. Regular case conferences and team meetings can help build relationships between different specialists. Financial incentives and reimbursement models should be aligned to support integrated care delivery. Additionally, healthcare organizations should foster a culture of collaboration by recognizing and rewarding cross-disciplinary initiatives.

The review presents strong evidence for the associations between oral and psychological health during pregnancy, yet it acknowledges several research gaps that need attention. Future studies should adopt longitudinal designs to better establish causality, include diverse geographic populations, and utilize standardized assessment protocols. The investigation of intervention effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of integrated care models can strengthen the evidence base for implementation [28].

5. Conclusions

This rapid scoping review establishes strong interconnections between oral and psychological states (anxiety, depression, and stress) during pregnancy, highlighting implications for maternal and child health outcomes. Evidence supports the implementation of pregnancy-specific integrated screening protocols, the development of targeted interventions, and the establishment of coordinated care pathways within existing prenatal care communities. Systematic changes in clinical practice and health policy can help break intergenerational cycles of poor health outcomes. Future research will focus on the development and evaluation of standardized assessment protocols and integrated care models across diverse populations. The implementation of these evidence-based recommendations could significantly enhance maternal and child health outcomes by providing comprehensive prenatal care that addresses both oral and psychological needs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, A.A.A. and S.R.; writing—review and editing, A.A.A., S.R., and C.M.J.; supervision, C.M.J.; resources, C.M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

OVID EMBASE Search Strategy

- exp pregnancy/

- (pregnant or pregnancy or expectant or maternal or antenatal or perinatal or prenatal). kw.

- exp puerperium/

- (postpartum or postnatal or puerperal or “new mother*”).ti,ab,kw.

- exp pregnancy care/or exp antenatal care/or exp postnatal care/

- (prenatal care or antenatal care or postnatal care or postpartum care or “after-birth care”). kw.

- or/1–6

- exp tooth disease/or exp mouth disease/

- (oral health or dental health or periodontal disease or gingivitis or dental caries or tooth decay or oral hygiene).ti,ab,kw.

- or/8–9

- exp mental health/or exp depression/or exp anxiety/or exp stress/

- (mental health or psychological health or depression or anxiety or stress or mood disorder* or perinatal depression or postpartum depression).ti,ab,kw.

- or/11–12

- exp health care/

- (healthcare or health service* or maternal health service* or dental service* or mental health service*).ti,ab,kw.

- or/14–15

- 7 and 10 and 13 and 16

- limit 17 to (english language and yr = “2000–Current”)

References

- Perera, I.; Hettiarachchige, L.; Perera, M.L. Psychological Health Status and Oral Health Outcomes of Pregnant Women: Practical Implications. Investig. Gynecol. Res. Womens Health (IGRWH) 2019, 2, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daalderop, L.A.; Wieland, B.V.; Tomsin, K.; Reyes, L.; Kramer, B.W.; Vanterpool, S.F.; Been, J.V. Periodontal Disease and Pregnancy Outcomes: Overview of Systematic Reviews. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2017, 3, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paglia, L.; Colombo, S. Perinatal oral health: Focus on the mother. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 20, 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, C.; Dong, T.; Jiang, W.; Gao, L.; Yuan, K.; Hu, X.; Lin, W.; Zhou, X.; Xu, C.; Huang, Z. Pregnancy-Related Ecological Shifts of Salivary Microbiota and Its Association with Salivary Sex Hormones. Preprint 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, F.; Caggiano, M.; Schiavo, L.; Savarese, G.; Carpinelli, L.; Amato, A.; Iandolo, A. Chronic Stress and Depression in Periodontitis and Peri-Implantitis: A Narrative Review on Neurobiological, Neurobehavioral and Immune–Microbiome Interplays and Clinical Management Implications. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitrescu, A.L. Depression and Inflammatory Periodontal Disease Considerations—An Interdisciplinary Approach. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphim, A.P.C.G.; Chiba, F.Y.; Pereira, R.F.; Mattera, M.S.d.L.C.; Moimaz, S.A.S.; Sumida, D.H. Relationship among periodontal disease, insulin resistance, salivary cortisol, and stress levels during pregnancy. Braz. Dent. J. 2016, 27, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliou, A.; Shankardass, K.; Nisenbaum, R.; Quiñonez, C. Current stress and poor oral health. BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, P.; Emingil, G.; Öztürk, V.-Ö.; Belibasakis, G.N.; Bostanci, N. Oxidative stress markers in saliva and periodontal disease status: Modulation during pregnancy and postpartum. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarkac, F.U.; Gokturk, O.; Demir, O. Effect of non-surgical periodontal therapy on the degree of gingival inflammation and stress markers related to pregnancy. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2018, 26, e20170630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamos, C.A.; Thompson, E.L.; Avendano, M.; Daley, E.M.; Quinonez, R.B.; Boggess, K.A. Oral health promotion interventions during pregnancy: A systematic review. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2015, 43, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.; Donnelly, L.; Janssen, P.; Jevitt, C.; Siarkowski, M.; Brondani, M. Integrating oral health into prenatal care: A scoping review. J. Integr. Care 2020, 28, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M.L.; Whitcomb, B.W.; Pekow, P.S.; Carbone, E.T.; Chasan-Taber, L. Anxiety, depression, and oral health among US pregnant women: 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J. Public Health Dent. 2016, 76, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffany, A.; Moore Simas, M.M.M.; Camille Hoffman, M.M.; Emily, S.; Miller, M.M.; Torri Metz, M. Screening and Diagnosis of Mental Health Conditions During Pregnancy and Postpartum: ACOG Clinical Practice Guideline No. 4. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 141, 1232–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Cademartori, M.G.; Gastal, M.T.; Nascimento, G.G.; Demarco, F.F.; Corrêa, M.B. Is depression associated with oral health outcomes in adults and elders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 2685–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Sawyer, E.; Siskind, D.; Lalloo, R. The oral health of people with anxiety and depressive disorders–a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 200, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.R. No Mental Health without Oral Health. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alex, A.M.; Levendosky, A.A.; Bogat, G.A.; Muzik, M.; Nuttall, A.K.; Knickmeyer, R.C.; Lonstein, J.S. Stress and mental health symptoms in early pregnancy are associated with the oral microbiome. BMJ Ment. Health 2024, 27, e301100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeniyi, A.A.; Laronde, D.M.; Brondani, M.A.; Donnelly, L.R. Perspectives of socially disadvantaged women on oral healthcare during pregnancy. Community Dent. Health 2020, 37, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Eakley, R.; Lyndon, A. Disparities in Screening and Treatment Patterns for Depression and Anxiety During Pregnancy: An Integrative Review. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2024, 69, 847–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.S.; Arima, L.Y.; Werneck, R.I.; Moysés, S.J.; Baldani, M.H. Determinants of Dental Care Attendance during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Caries Res. 2018, 52, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbella, S.; Taschieri, S.; Francetti, L.; De Siena, F.; Del Fabbro, M. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Odontology 2012, 100, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Basra, M.; Begum, N.; Rani, V.; Prasad, S.; Lamba, A.K.; Verma, M.; Agarwal, S.; Sharma, S. Association of maternal periodontal health with adverse pregnancy outcome. J. Obs. Gynaecol. Res. 2013, 39, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, G.C. Bi-directional relationship between pregnancy and periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000 2013, 61, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Fu, X.; Zhao, C.; Yang, L.; Huang, R. The bidirectional relationship between periodontal disease and pregnancy via the interaction of oral microorganisms, hormone and immune response. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1070917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, A.; Potdar, J. Maternal Mental Health During Pregnancy: A Critical Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e30656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, T.; Magann, E.F.; Phillips, A.M.; Ray-Griffith, S.L.; Coker, J.L.; Stowe, Z.N. Women’s Mental Health Services and Pregnancy: A Review. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2022, 77, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.; Dahlen, H.G.; Blinkhorn, A.S.; Ajwani, S.; Bhole, S.; Ellis, S.; Yeo, A.; Elcombe, E.; Johnson, M. Evaluation of a midwifery initiated oral health-dental service program to improve oral health and birth outcomes for pregnant women: A multi-centre randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 82, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbins, M. Rapid review guidebook. Natl. Collab. Cent. Methods Tools 2017, 13, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, A.; Hersi, M.; Garritty, C.; Hartling, L.; Shea, B.J.; Stewart, L.A.; Welch, V.A.; Tricco, A.C.; Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group. Rapid review method series: Interim guidance for the reporting of rapid reviews. BMJ Evid. -Based Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review Software. Melbourne, Australia. Available online: http://www.covidence.org (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2006; Volume 1, p. b92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhareky, M.; Nazir, M.A.; AlGhamdi, L.; Alkadi, M.; AlBeajan, N.; AlHossan, M.; AlHumaid, J. Relationship Between Maternal Dental Anxiety and Children’s Dental Caries in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2021, 13, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Guerra, J.J.; Ceron-Souza, V.; Mafla, A.C. Dynamic among periodontal disease, stress, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Rev. De Salud Publica 2010, 12, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esa, R.; Savithri, V.; Humphris, G.; Freeman, R. The relationship between dental anxiety and dental decay experience in antenatal mothers. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2010, 118, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastmann, A.H.; Xavier, S.R.; Pilownic, K.J.; Romano, A.R.; Gomes, F.d.A.; Goettems, M.L.; Morgental, R.D.; Pappen, F.G. Pain, anxiety, and catastrophizing among pregnant women with dental pain, undergoing root canal treatment. Braz. Oral Res. 2024, 38, e054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokturk, O.; Yarkac, F.U.; Avcioglu, F. Sex steroid levels and stress-related markers in pregnant and non-pregnant women and the effect of periodontal therapy. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Bucal 2024, 29, e483–e491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.-J.; Lee, H.J.; Cho, S.H. Influences of oral health behaviors, depression and stress on periodontal disease in pregnant women. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2016, 46, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarkac, F.U.; Gokturk, O.; Demir, O. Interaction between stress, cytokines, and salivary cortisol in pregnant and non-pregnant women with gingivitis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.E.; Albalawi, A.N.; Alshehri, A.A.; AlBlaihed, R.M.; Alsalamah, M.A. Stress and its predictors in pregnant women: A study in Saudi Arabia. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2017, 10, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.Q.; Chen, M.-M.; Zhang, H.-L.; Nie, R. Association of dental anxiety and oral health-related quality of life in pregnant women: A cross-sectional survey. DEStech Trans. Biol. Health 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolvanen, M.; Hagqvist, O.; Luoto, A.; Rantavuori, K.; Karlsson, L.; Karlsson, H.; Lahti, S. Changes over time in adult dental fear and correlation to depression and anxiety: A cohort study of pregnant mothers and fathers. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2013, 121 Pt 2, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRatroot, S.; Alotaibi, G.; AlBishi, F.; Khan, S.; Ashraf Nazir, M. Dental Anxiety Amongst Pregnant Women: Relationship with Dental Attendance and Sociodemographic Factors. Int. Dent. J. 2022, 72, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cademartori, M.G.; Demarco, F.F.; Freitas da Silveira, M.; Barros, F.C.; Corrêa, M.B. Dental caries and depression in pregnant women: The role of oral health self-perception as mediator. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 1733–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.G.; Park, S.K.; Nho, J.H. Associated factors of depression in pregnant women in Korea based on the 2019 Korean Community Health Survey: A cross-sectional study. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2022, 28, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.A.; AlSharief, M.; Al-Ansari, A.; El Akel, A.; AlBishi, F.; Khan, S.; Alotaibi, G.; AlRatroot, S. Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Its Relationship with Dental Anxiety among Pregnant Women in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 1578498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, A.L.; Boggess, K.A.; Moss, K.L.; Beck, J.; Offenbacher, S. Periodontal disease, oxidative stress, and risk for preeclampsia. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Lilly, C.; Shaffer, J.R.; Foxman, B.; Marazita, M.L.; McNeil, D.W. Effects of depression and stress on oral self-care among perinatal women in Appalachia: A longitudinal study. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2024, 52, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeil, D.W.; Hayes, S.E.; Randall, C.L.; Polk, D.E.; Neiswanger, K.; Shaffer, J.R.; Weyant, R.J.; Foxman, B.; Kao, E.; Crout, R.J.; et al. Depression and rural environment are associated with poor oral health among pregnant women in Northern Appalachia. Behav. Modif. 2016, 40, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auger, N.; Low, N.; Lee, G.; Lo, E.; Nicolau, B. Maternal Mental Disorders before Delivery and the Risk of Dental Caries in Children. Caries Res. 2020, 54, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, A.; Jackson, D.B.; Simon, L.; Ganson, K.T.; Nagata, J.M. Stressful life events, oral health, and barriers to dental care during pregnancy. J. Public Health Dent. 2023, 83, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, A.M.; Askar, H.; Tattan, M.; Taichman, R.S.; Wang, H.-L. The assessment of stress, depression, and inflammation as a collective risk factor for periodontal diseases: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamis, S.A.; Asimakopoulou, K.; Newton, J.T.; Daly, B. Oral Health Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceptions of Pregnant Kuwaiti Women. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2016, 1, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shappell, A.V.; Cartier, P.M. Understanding the Mental-Dental Health Connection Said to Be Integral to Patient Care. Psychiatric News 2023, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.V.; Samelson, R. Oral health care during pregnancy recommendations for oral health professionals. N. Y. State Dent. J. 2009, 75, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Alkhers, N.; Kopycka-Kedzierawski, D.T.; Billings, R.J.; Wu, T.-T.; Castillo, D.A.; Rasubala, L.; Malmstrom, H.; Ren, Y.; Eliav, E. Prenatal Oral Health Care and Early Childhood Caries Prevention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Caries Res. 2019, 53, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, N.K.; Momeni, S.S.; Whiddon, J.; Cheon, K.; Cutter, G.R.; Wiener, H.W.; Ghazal, T.S.; Ruby, J.D.; Moser, S.A. Association Between Early Childhood Caries and Colonization with Streptococcus mutans Genotypes from Mothers. Pediatr. Dent. 2017, 39, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum, A.; Azogui-Lévy, S. Oral Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices, and Literacy of Pregnant Women: A Scoping Review. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2023, 21, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vilella, K.D.; Fraiz, F.C.; Benelli, E.M.; Assunção, L.R.d.S. Oral Health Literacy and Retention of Health Information Among Pregnant Women: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2017, 15, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, A.M.; Child, W.L.; Maybury, C. Obstetric Providers’ Role in Prenatal Oral Health Counseling and Referral. Am. J. Health Behav. 2019, 43, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapidos, A.; Henderson, J.; Garlick, J.; Guzmán, R.; Tyus, J.; Werner, P.; Rulli, D. Integrating oral health into community health worker and peer provider certifications in Michigan: A community action report. J. Public Health Dent. 2022, 82, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).