Abstract

Introduction: A clinical audit is a tool that allows the evaluation of and improvement in the quality of stroke care processes. Fast, high-quality care and preventive interventions can reduce the negative impact of stroke. Objective: This review was conducted on studies investigating the effectiveness of clinical audits to improve the quality of stroke rehabilitation and stroke prevention. Method: We reviewed clinical trials involving stroke patients. Our search was performed on PubMed databases, Web of Science, and Cochrane library databases. Of the 2543 initial studies, 10 studies met the inclusion criteria. Results: Studies showed that an audit brought an improvement in rehabilitation processes when it included a team of experts, an active training phase with facilitators, and short-term feedback. In contrast, studies looking at an audit in stroke prevention showed contradictory results. Conclusions: A clinical audit highlights any deviations from clinical best practices in order to identify the causes of inefficient procedures so that changes can be implemented to improve the care system. In the rehabilitation phase, the audit is effective for improving the quality of care processes.

1. Introduction

Stroke is one of the main causes of death and disability worldwide, causing 5 million deaths [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an instance of ictus occurs every 5 s [2]. Stroke is a clinical syndrome associated with rapidly developing signs of focal or global loss of cerebral functions, with a cause of vascular origin [3].

The acute phase is extremely important for a successful rehabilitation; in fact, there is a therapeutic window during which intervention is more likely to modify the course of the disease and successfully lead to neuronal reactivation [4,5]. Receiving organized hospital care in a stroke unit is associated with patients being more likely to be alive, independent, and living at home 1 year after their stroke compared to patients who do not receive such specialized care [6]. Preventive interventions are also essential to reduce the risk of recurrence. Prevention processes include encouraging a healthy lifestyle with regular physical activity and balanced nutrition to keep body weight and blood cholesterol levels under control, and with limits on alcohol, smoking and drug consumption [7].

For the treatment of stroke, therefore, phases of rehabilitation and preventive care are extremely important. For this reason, it is critical to find ways to evaluate and improve stroke care processes. An adequate tool to evaluate these elements is the audit.

The clinical audit is seen as one approach to improving the quality of patient care [8,9]. Specifically, a clinical audit is the systematic, critical analysis of the quality of medical care, including the procedures used for diagnosis and treatment, the use of resources, and the resulting outcome and quality of life for the patient. In other words, the audit is the process of reviewing the delivery of care to identify deficiencies so that they may be remedied [10,11].

The clinical audit can be described in four main phases: (i) planning (stating the aim, defining improvement, deciding quantifiable change); (ii) doing (collecting data, monitoring progress, providing feedback); (iii) studying (discussing data, assessing data, interpreting data); and (iv) acting (continued action) [12]. Clinical audits are largely used in medical care, both locally (local hospitals and medical centers) and nationwide (to improve the national health system). However, since audits are rarely published and available to the wider community, it is hard to both identify a common practice and evaluate their outcomes [13].

Indeed, no agreement exists about which audit methodologies are the most suitable approach, and, not surprisingly, there is significant confusion among healthcare professionals about how to implement an audit and integrate it effectively into clinical practice [10].

Given the high variability in audit methodologies, and the importance of improving clinical practice for stroke care, this review focused on the studies that investigated the efficiency of clinical audits to improve quality care for stroke (rehabilitation and prevention) by taking into account clinical trials carried out on patients with ictus.

2. Materials and Methods

A descriptive review was conducted on studies that performed a trial on the care process for rehabilitation and prevention of stroke that used the audit for assessment of quality care.

Studies were identified by searching PubMed (from 1972 to 2022), Web of Science (from 1991 to 2022), and the Cochrane library (from 1989 to 2022) databases, published before 7 October 2022. The keyword search was conducted by one researcher and took about 2 days.

The search keywords were “stroke” AND “audit” (“stroke” [MeSH Terms] OR “stroke” [All Fields]) AND (“audit” [MeSH Terms] OR “quality of care” [All Fields] OR “assessment of quality” [All Fields] OR “improvement of care” [All Fields] OR “improvement of quality” [All Fields] OR “revision process” [All Fields] OR “revision of care” [All Fields]). After duplicates had been removed, all articles were evaluated based on title, abstract, and text.

Studies that met the following criteria were included in this review:

- -

- Studies of audits;

- -

- Prevention and rehabilitation of stroke;

- -

- Clinical trials;

- -

- Studies in English;

- -

- No review;

- -

- There were no restrictions regarding the year of publication (details about the year of publication found in each database search are specified above).

Evaluation of the studies was completed over three rounds (each study was tripled-checked for inclusion) by the same researcher who carried out the keyword search. This phase took about 1 month.

3. Results

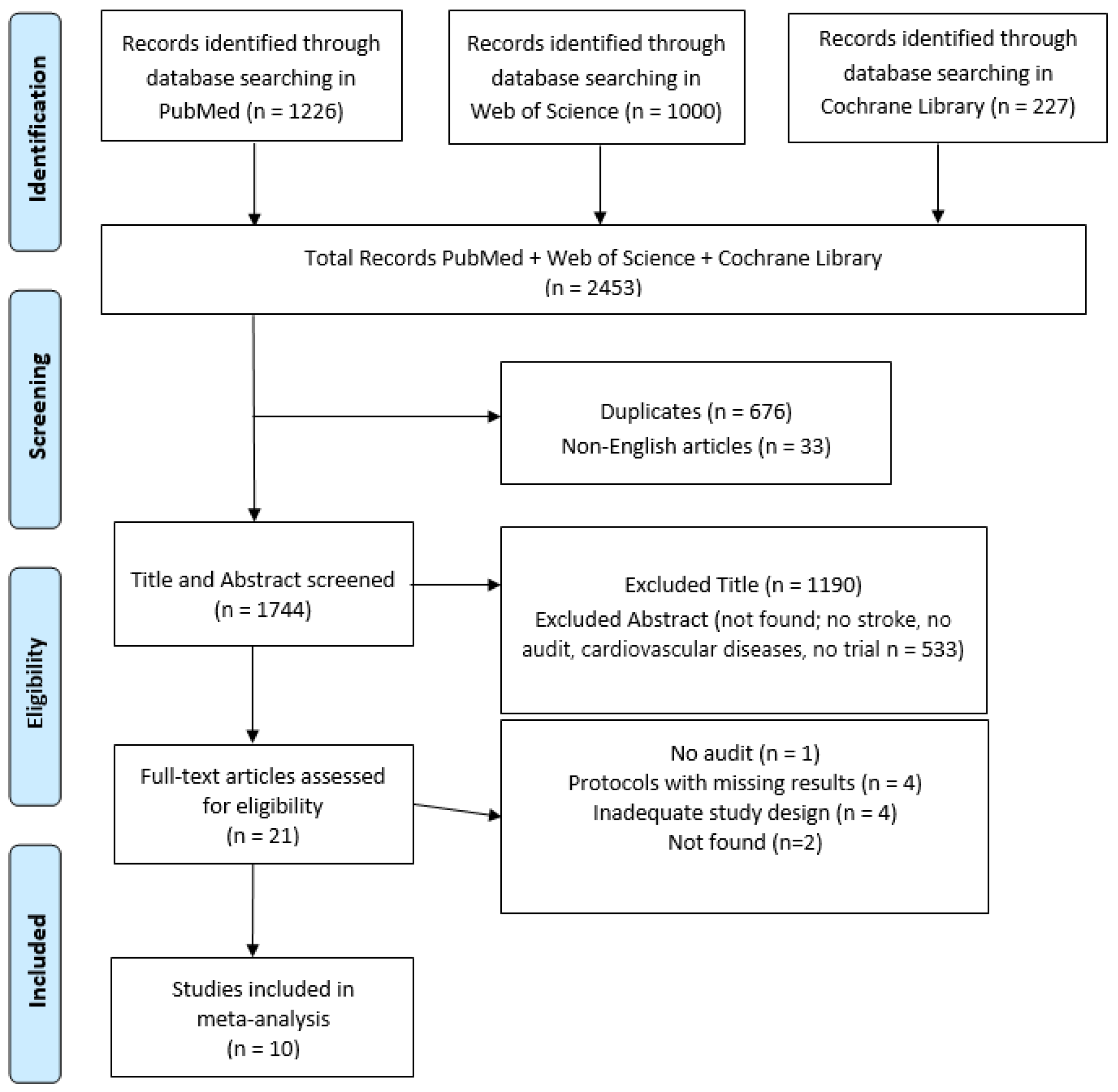

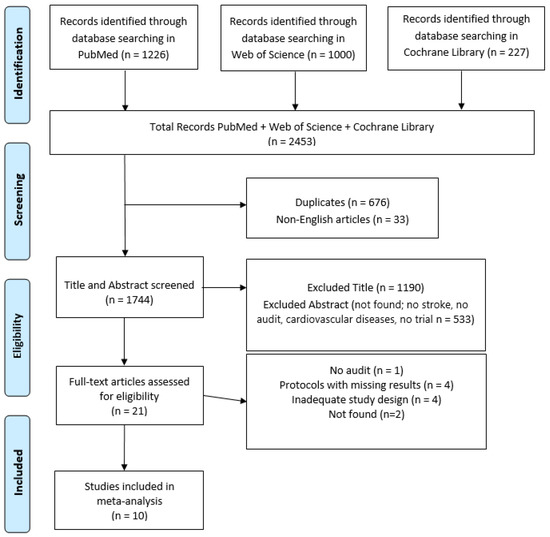

Out of the initial 2543 studies identified from our search, 10 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graphic of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of review article.

All included studies examined the quality of stroke care using the audit as an assessment tool (see Table 1). Of 10 studies that evaluated the quality of stroke care, 7 regarded rehabilitation [14,15,16,17,18,19,20] and 3 regarded prevention [21,22,23]. For a detailed description of different audit interventions see Table 2.

Table 1.

Studies’ characteristics.

Table 2.

Type of audit.

3.1. Studies on Rehabilitation

Of the seven studies that evaluated the quality of rehabilitation in stroke patients, five audited both intervention and control groups [14,15,18,19,20], while two studies audited the intervention group only [16,17].

Overall, results from studies that audited both groups show that an audit is an effective tool to improve the quality of rehabilitation in stroke patients. For example, Power et al., 2014 [14] reported a 10.9% improvement after implementing a Breakthrough Series (BTS) intervention, which includes a team of quality improvement experts, three training meetings, and an implementation phase. McGillivray et al., 2017 [18] and Hinchey et al., 2010 [19] found encouraging results for audit effectiveness, specifically when feedback was given within one day by a coordinating nurse (concurrent review) and when a multifaceted intervention was included. Consistent with these studies, Joliffe et al., 2020 [20] showed audit-related improvement specifically when therapists received the facilitator-mediated guideline package. Sulch et al., 2002 [15] carried out a study on 152 patients comparing whether the Integrated Care Pathway (ICP)—i.e., a multidisciplinary set of progressive care delivered within a specific time frame—improves the quality of care compared to routine care. Results showed that ICP, compared to routine care, was associated with greater improvement in initial assessments, better documentation of the diagnosis, and a higher rate of discharge within 24 h.

In contrast to the studies just presented that audited both groups, Linch et al., 2016 [16] and Machine-Carrion et al., 2019 [17] carried out an investigation of the effectiveness of the multifaceted intervention by auditing the intervention group only.

In particular, Lynch et al., 2016 [16] carried out a study in Australia involving a total of 586 patients over a period of 14 months. The objective was to compare two groups, one receiving education-only intervention and one receiving a multifaceted intervention, with the audit performed on the latter group only. The results showed that, similarly across the two groups, the odds for a patient to receive an assessment for rehabilitation were 3.69 times greater in the post-intervention period compared to the pre-intervention period, with no difference between the two interventions.

In the study by Machine-Carrion et al., 2019 [17], patients from hospitals that had received usual care (no intervention) were compared with patients in hospitals that had received the multifaceted intervention, on which the audit was performed. Patients in intervention hospitals were more likely to receive all acute therapies during hospitalization than those in control hospitals.

3.2. Studies on Prevention

Of the three studies evaluating stroke prevention, two audited both experimental groups (i.e., intervention and control) [21,23], while one audited the intervention group only [22].

Wright et al., 2007 [23] carried out a study of approximately 2800 patients in the UK, finding an improvement in patients’ adherence to atrial fibrillation and TIA therapy, which was significantly greater in the intervention group—who attended 5 meetings to improve adherence within guidelines—compared to the control group.

With a similar sample, Williams et al., 2016 [22] compared 12 hospitals in the USA and 2164 patients to see if a training intervention plus indicator feedback was more effective for improving quality than indicator feedback alone. The training intervention plus indicator feedback was associated with improvement in venous thrombosis prophylaxis (DVT), but the effect was not sustained long-term.

With a much larger sample of 12,766 patients, Geary et al., 2019 [21] carried out a study in Sweden, with the aim of improving the diagnostics and use of preventive drugs for stroke. In diagnosing TIA, but not ischemic stroke, there was an improvement in the intervention group compared with the control group. Instead, regarding preventive drugs use, the audit and feedback intervention did not lead to any improvement in patients with ischemic stroke/TIA.

4. Discussion

Stroke can be life-threatening in the short term and can cause a reduction in quality of life and, consequently, physical, emotional, and behavioral disabilities [6,24]. Over the past two decades, A&F strategies have been used for all areas of health care, namely, preventive, acute, chronic, and palliative care, with the aim of improving the quality of performance, reducing errors, and increasing safety [25].

First, considering stroke rehabilitation, the studies included here showed that an audit was generally associated with improved care processes. Specifically, the audit of rehabilitation interventions brought further improvements when it included a team of experts [14,15,19], an active training phase with facilitators [14,18,20], and concurrent, short-term feedback [18].

These conclusions agree with what Welsh et al., 1993 [26] identified as key factors for audit success. These include an enabling organizational environment, strong leadership and direction of audit programs, strategy and planning in audit programs, resources and support for audit programs, monitoring and reporting of audit activity, commitment and participation, and high levels of audit activity which is seen by its participants as engaging and relevant, with respects to its nature and impact. More recent studies further suggest that audit success increases if the audit and feedback is provided by professionals who are admired by healthcare professionals [27,28]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that it is essential for audit success that personnel trust the data being investigated and consider the clinical topics being audited important [29,30]. A prerequisite for an optimal audit leading to change is that clinicians are committed to behavior change [31].

In contrast, an audit of stroke prevention interventions seems to report conflicting results, and studies are too few to reach satisfactory conclusions. In particular, of the three studies examined, while two reported audit-related improvements in stroke prevention care, these results are limited by small samples [22,23] and lack of assessment of long-term effects [22]. When a much larger sample was considered, there were no positive effects of the audit on the prevention of ischemic stroke [21].

It was possible that some of the main barriers to clinical audit identified by Robinson 1996 [32] may have been responsible for the null results found in our review in relation to prevention care, including a lack of resources, lack of expertise or advice in project design and analysis, relationships between groups and group members, lack of an overall plan for audit, and organizational impediments.

Additional factors of audit failure could be due to lack of clear and easy-to-understand feedback [33,34] and a lack of cooperation and motivation from the parts involved [35]. Springer et al., 2021 [35], in fact, highlighted that healthcare professionals working as a team during the audit and feedback process have improved stroke care. However, it remains unclear why these barriers would have affected the success of the clinical audit on prevention care specifically, while rehabilitation care was found to be improved overall, at least across the studies reviewed here. It may be that the clinical audit may be a tool for improving patient care differently depending on whether care applies to prevention or rehabilitation.

Furthermore, the studies reviewed found that audits were performed differently, possibly due to variability in healthcare workforce knowledge of clinical audits [36] and/or variability in access to funds [10], making a systematic comparison of the various protocols difficult (Table 2) [10,37].

This review included a small number of papers as only 10 studies met the inclusion criteria. This, combined with the significant variability in methodologies among the cited studies, which in turn led to significant variability in study results, including both quantitative and qualitative outcomes, did not allow objective comparisons to be made between investigations. This made it impossible to conduct a meta-analysis, making it difficult to reach satisfactory conclusions; further studies are needed to verify the effectiveness of audits as a tool to improve interventions for stroke prevention. Despite these limitations, the present review is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to provide a detailed picture of the clinical trials that have evaluated the usefulness of audits in improving the quality of care for stroke patients, allowing for a systematic evaluation of audit effectiveness and identification of weaknesses, in turn enabling improvement so that more efficient future studies can be designed.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, in light of the reviewed studies, the audit appears to be effective in improving the quality of care for stroke patients in the rehabilitation phase. More studies are needed to reach robust conclusions with regard to the preventive phase. Future studies should focus on applying standardized audit protocols to advance improvements in stroke care and allow for systematic comparisons between studies [38]. In order to improve clinical practice, a number of references may provide appropriate learning sessions and educational material regarding the following: the theory and practice of improvement [14,17,22]; meetings to improve adherence to guidelines [23,39]; case reviews conducted by researchers trained in the National Stroke Audit methodology [15]; regular conferences on quality measures and discussions of aspects that need to be improved [17]; and systems capable of quickly and regularly giving feedback [18].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: F.C. and I.C., Methodology: D.C. and M.C.D.C., Resources: F.C., P.B. and G.D., Validation: R.C. and M.C.D.C., Investigation: I.C., V.L.B. and F.C., Writing—Original Draft Preparation: I.C., M.C.D.C. and F.C., Writing—Review and Editing: V.L.B., D.C. and A.I., Supervision: P.B. and R.C., Data Curation: M.C.D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Italian Ministry of Health (NET-2016-02364191).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Consent from the ethics committee was not required for the research.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Paul, C.L.; Levi, C.R.; D’Este, C.A.; Parsons, M.W.; Bladin, C.F.; Lindley, R.I.; Attia, J.R.; Henskens, F.; Lalor, E. Thrombolysis ImPlementation in Stroke (TIPS): Evaluating the effectiveness of a strategy to increase the adoption of best evidence practice-protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial in acute stroke care. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grysiewicz, R.A.; Thomas, K.; Pandey, D.K. Epidemiology of Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Stroke: Incidence, Prevalence, Mortality, and Risk Factors. Neurol. Clin. 2008, 26, 871–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warlow, C.P. Epidemiology of stroke. Lancet 1998, 352, S1–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vloothuis, J.D.; Mulder, M.; Veerbeek, J.M.; Konijnenbelt, M.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; Ket, J.C.; Kwakkel, G.; van Wegen, E.E. Caregiver-mediated exercises for improving outcomes after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 12, CD011058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, Á.A. Rehabilitación del ACV: Evaluación, pronóstico y tratamiento. Galicia Clínica 2009, 70, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lannon, R.; Smyth, A.; Mulkerrin, E.C. An audit of the impact of a stroke unit in an acute teaching hospital. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2010, 180, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarikaya, H.; Ferro, J.; Arnold, M. Stroke Prevention-Medical and Lifestyle Measures. Eur. Neurol. 2015, 73, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A. Clinical audit: Time for a reappraisal. J. R. Coll. Physicians Lond. 1996, 30, 415. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, C.H. Clinical audit in emergency medicine. Hong Kong J. Emerg. Med. 2003, 10, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, G.; Crombie, I.K.; Alder, E.M.; Davies, H.T.O.; Millard, A. Reviewing audit: Barriers and facilitating factors for effective clinical audit. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2000, 9, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areti Tsaloglidou, R.N. Does Audit Improve the Quality of Care? Int. J. Caring Sci. 2009, 2, 65. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, G.J.; Moen, R.D.; Nolan, K.M. The Improvement Guide, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, N.; Pang, D.S. A practical guide to implementing clinical audit. Can. Vet. J. 2021, 62, 145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Power, M.; Tyrrell, P.J.; Rudd, A.G.; Tully, M.P.; Dalton, D.; Marshall, M.; Chappell, I.; Corgié, D.; Goldmann, D.; Webb, D.; et al. Did a quality improvement collaborative make stroke care better? A cluster randomized trial. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulch, D.; Evans, A.; Melbourn, A.; Kalra, L. Does an integrated care pathway improve processes of care in stroke rehabilitation? A randomized controlled trial. Age Ageing 2002, 31, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, E.A.; Cadilhac, D.A.; Luker, J.A.; Hillier, S.L. Education-only versus a multifaceted intervention for improving assessment of rehabilitation needs after stroke; a cluster randomised trial. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machline-Carrion, M.J.; Santucci, E.V.; Damiani, L.P.; Bahit, M.C.; Málaga, G.; Pontes-Neto, O.M.; Pontes-Neto, O.; Martins, S.C.O.; Zétola, V.F.; Normilio-Silva, K.; et al. Effect of a quality improvement intervention on adherence to therapies for patients with acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillivray, C.G.; Silver, B. Evaluating the effectiveness of concurrent review: Does it improve stroke measure results? Qual. Manag. Health Care 2017, 26, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchey, J.A.; Shephard, T.; Tonn, S.T.; Ruthazer, R.; Hermann, R.C.; Selker, H.P.; Kent, D.M. The Stroke Practice Improvement Network: A quasiexperimental trial of a multifaceted intervention to improve quality. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc.Dis. 2010, 19, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, L.; Hoffmann, T.; Churilov, L.; Lannin, N.A. What is the feasibility and observed effect of two implementation packages for stroke rehabilitation therapists implementing upper limb guidelines? A cluster controlled feasibility study. BMJ Open Qual. 2020, 9, e000954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, L.; Hasselström, J.; Carlsson, A.C.; Eriksson, I.; von Euler, M. Secondary prevention after stroke/transient ischemic attack: A randomized audit and feedback trial. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2019, 140, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Daggett, V.; E Slaven, J.; Yu, Z.; Sager, D.; Myers, J.; Plue, L.; Woodward-Hagg, H.; Damush, T.M. A cluster-randomised quality improvement study to improve two inpatient stroke quality indicators. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016, 25, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.; Bibby, J.; Eastham, J.; Harrison, S.; McGeorge, M.; Patterson, C.; Price, N.; Russell, D.; Russell, I.; Small, N.; et al. Multifaceted implementation of stroke prevention guidelines in primary care: Cluster-randomised evaluation of clinical and cost effectiveness. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2007, 16, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Buono, V.; Corallo, F.; Bramanti, P.; Marino, S. Coping strategies and health-related quality of life after stroke. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cola, M.C.; Ciurleo, R.; Agabiti, N.; Martino, M.D.; Bramanti, P.; Corallo, F. Audit and feedback in cardio-and cerebrovascular setting: Toward a path of high reliability in Italian healthcare. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 907201. [Google Scholar]

- Walshe, K.; Coles, J. Evaluating Audit: A Review of Initiatives; Caspe Research: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson, E.; Dahlin, S.; Anell, A. Conditions and barriers for quality improvement work: A qualitative study of how professionals and health centre managers experience audit and feedback practices in Swedish primary care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Falk, A. Psychological foundations of incentives. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2002, 46, 687–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gude, W.T.; Roos-Blom, M.J.; van der Veer, S.N.; Dongelmans, D.A.; de Jonge, E.; Francis, J.J.; Peek, N.; de Keizer, N.F. Health professionals’ perceptions about their clinical performance and the influence of audit and feedback on their intentions to improve practice: A theory-based study in Dutch intensive care units. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.; Panagopoulou, E.; Esmail, A.; Richards, T.; Maslach, C. Burnout in healthcare: The case for organisational change. Bmj 2019, 366, l4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenngård, A.H.; Anell, A. The impact of audit and feedback to support change behaviour in healthcare organisations-a cross-sectional qualitative study of primary care centre managers. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S. Audit in the therapy professions: Some constraints on progress. Qual. Health Care 1996, 5, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, T.A.; Wood, S.; Brehaut, J.; Colquhoun, H.; Brown, B.; Lorencatto, F.; Foy, R. Opportunities to improve the impact of two national clinical audit programmes: A theory-guided analysis. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2022, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, D.J.; Durbin, J.; Barnsley, J.; Ivers, N.M. Measurement without management: Qualitative evaluation of a voluntary audit & feedback intervention for primary care teams. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Springer, M.V.; Sales, A.E.; Islam, N.; McBride, A.C.; Landis-Lewis, Z.; Tupper, M.; Corches, C.L.; Robles, M.C.; Skolarus, L.E. step toward understanding the mechanism of action of audit and feedback: A qualitative study of implementation strategies. Implement. Sci. 2021, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alinnor, E.A.; Ogaji, D.S. Physicians’ knowledge, attitude and practice of clinical audit in a tertiary health facility in a developing country: A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 43, 22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McErlain-Burns, T.L.; Thomson, R. The lack of integration of clinical audit and the maintenance of medical dominance within British hospital trusts. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 1999, 5, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, A.; Bentley, P.; Polychronis, A.; Price, N.; Grey, J. Clinical audit in the National Health Service: Fact or fiction? J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 1996, 2, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruen, C.; Merriman, N.A.; Murphy, P.J.; McCormack, J.; Sexton, E.; Harbison, J.; Williams, D.; Kelly, P.J.; Horgan, F.; Collins, R.; et al. Development of a national stroke audit in Ireland: Scoping review protocol. HRB Open Res. 2021, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).